ABSTRACT

Drawing upon ethical climate theory and conservation of resource theory, this study provides a theoretical model to explain the effect of a perceived caring climate in the workplace on the employees’ turnover intention through the serial multiple mediation of workplace incivility (caused by coworkers) and employees’ emotional exhaustion. A total of 291 frontline employees from the service industry in Norway participated in this study, and structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to analyze the data. The findings indicated that a caring climate has a significant negative effect on turnover intention. The mediating effect of coworker incivility was not supported in the multiple mediation model; however, it was supported if it was considered as the only mediator in the relationship between caring climate and turnover intention. Moreover, emotional exhaustion mediated the relationship between caring climate and turnover intention. The serial mediation effect of coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion was also supported in the relationship between caring climate and turnover intention. The results of this study enable managers to create a caring climate in the workplace and minimize the detrimental effects of incivility and turnover intention in the service industry.

Introduction

Today’s intense competition and pressure to expand productivity in the service industry reveals the crucial role of frontline employees who are in charge of delivering high-quality services and complaint-handling processes. They act as the face of the organization through their frequent face-to-face or voice-to-voice interaction with customers (Yavas et al., Citation2011) and form the core of the customer’s service experience (Paek et al., Citation2015). Frontline employees’ high level of job performance is a key factor in organizational performance and in gaining a competitive advantage (Dessler, Citation2011). However, employee turnover is a challenge in the tourism and hospitality industry (Gjerald et al., Citation2021) since its rate is “nearly twice the average rate for all other sectors” (Deloitte, Citation2010, p. 35), which leads to excessive costs for recruiting and training employees (Panwar et al., Citation2012). Thus, it is crucial to investigate the antecedents of turnover intention and to find the best way to decrease it.

The quality of the service work environment and the role of emotions are significant issues in hospitality management (Gjerald et al., Citation2021; Lundberg & Furunes, Citation2021). Negative workplace experiences, especially those with a social relationship theme (e.g. interpersonal treatment, workplace climate, and peer relationships), result in employees’ emotional exhaustion and their intention to leave their jobs (Shapira-Lishchinsky & Even-Zohar, Citation2011). One of these negative interpersonal interactions is workplace incivility, which could frequently happen over long periods of time in the organization (Cortina & Magley, Citation2009) and leads to negative behavioral responses such as turnover intentions among targeted employees (Griffin, Citation2010; Lim et al., Citation2008; Miner-Rubino & Reed, Citation2010; Wilson & Holmvall, Citation2013). The concept of workplace incivility is introduced and defined by Andersson and Pearson (Citation1999, p. 457) as “low-intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous intent to harm the target, in violation of workplace norms for mutual respect. Uncivil behaviors are characteristically rude and discourteous, displaying a lack of regard for others.” Based on this definition, the intention to harm, the targets, the intensity of the actions, and continuation are the most important factor in differentiating between workplace incivility and other types of negative work behavior such as aggression, violence, and antisocial behavior (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999). Generally, workplace incivility refers to any repetitive rude and low intensive behavior at work, which could be easily overlooked and cause harmful effects at the individual, and the organizational level (Reio & Ghosh, Citation2009). Moreover, uncivil behaviors are more verbal, passive, indirect, and subtle compared to other negative treatments in the organization (Pearson et al., Citation2005). Since the reliance on coworkers is an important aspect of service jobs, being a victim of coworkers’ uncivil behaviors and having poor relations with them lead service employees to feel unhappy, angry, tired, and consequently exhausts them emotionally (Hur et al., Citation2015). Emotionally exhausted employees, in turn, may show negative job outcomes such as turnover intention (Hur et al., Citation2015).

On the other hand, however, the perception of social support in the organization is a critical emotional resource for employees to positively manage their emotions and deal more effectively with job stressors (Lai & Chen, Citation2016). Kao et al. (Citation2014) considered a caring climate as one of the most significant factors in addressing the relationship between social stressors and the resulting negative behaviors. The focus of a caring climate is on how the perceptions of organizational policies and procedures affect employees’ behavior in relation to team interest, friendships, and concern for coworkers’ well-being (Cullen et al., Citation1993; Victor & Cullen, Citation1988). In the current study, a perceived caring climate is considered as a significant preventive remedy and control mechanism for stressors and negative behaviors in the workplace.

The main purpose of the current study is to develop a theoretical framework, where the link between employees’ perceptions of a caring climate and turnover intention is explained by the serial multiple mediation effect of both coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion. This study contributes to the relevant literature in two ways. First, although scholars have broadly studied turnover intention from different lenses in past research, it is only just beginning to attract close academic attention from the perspective of an ethical climate in recent literature (e.g. Demirtas & Akdogan, Citation2015; Joe et al., Citation2018). Thus, the current study is an effort to complement the relevant literature by investigating how turnover intention is affected by a caring climate – an important type of ethical climate – in the workplace, which can help managers to evaluate employees’ turnover intention in a more timely fashion and improve personnel reviews. More explanation is available in the next section “theoretical underpinning and hypotheses”.

Second, the general focus of workplace incivility literature is on the social, psychological, and financial consequences of negative behavior that harms the interpersonal relationship of employees and organizational outcomes (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999; Bai et al., Citation2016; Cortina et al., Citation2001; Jin et al., Citation2020; Lim et al., Citation2008; Liu et al., Citation2019; Namin et al., Citation2022; Porath & Pearson, Citation2013; Schilpzand et al., Citation2016). However, research into the antecedents of workplace incivility is scarce. In particular, our knowledge about the effect of a caring climate on social stressors is severely limited (Kao et al., Citation2014). One of the important research areas in workplace incivility literature that deserves scholars’ attention is understanding how the organizational climate as a situational attribute can affect the pervasiveness of incivility in the working environment. In a review study, Schilpzand et al. (Citation2016) encouraged researchers to examine different organizational climate characteristics and their effects on workplace incivility. Moreover, previous studies (e.g. Abubakar et al., Citation2017; Arasli et al., Citation2018; Namin et al., Citation2022) revealed that perceived incivility among service employees has highly detrimental impacts on individual and organizational outcomes such as well-being, emotional exhaustion, and retention of staff, which is especially true for the service sector with its high employee turnover rate. Thus, this study investigated the antecedent of workplace incivility from an organizational climate perspective to reveal how the perception of a caring climate can influence workplace incivility and its detrimental results, including employees’ emotional exhaustion and turnover intention. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effect of a caring climate on frontline service employees’ turnover intention through testing both coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion as mediation mechanisms in the service industry in a Norwegian context.

Theoretical underpinning and hypotheses

Perception of a caring climate and turnover intention

As a type of workplace climate, the ethical climate was defined by Victor and Cullen (Citation1987) as “the shared perceptions of what is regarded ethically correct behaviors and how ethical situations should be handled in an organization” (p. 51). Five important types of theoretical ethical climate are instrumental, law and code, independence, rules, and caring climate (Victor & Cullen, Citation1988). A meta-analytic review subsequently revealed that these five types of ethical climate are also found in most of the other relevant empirical studies (Martin & Cullen, Citation2006). Fu and Deshpande (Citation2012) indicated that the biggest positive correlation exists between the perception of a caring climate and employees’ ethical behavior. According to Victor and Cullen (Citation1988), a caring climate, which encompasses the benevolence criterion of ethical climate, refers to employees’ shared perceptions of policies, procedures, and systems within the organization that influence employees’ behaviors by emphasizing friendship and team interest (Cullen et al., Citation1993). In fact, the main aspect of a caring climate is to find the best for everyone in the organization. Working in a caring climate generates a range of positive behaviors among employees; they show good manners toward others, protect each other’s rights, participate in social responsibility programs, and strive for the benefit of the organization (Kalafatoğlu & Turgut, Citation2019).

According to ethical climate theory (Victor & Cullen, Citation1987, Citation1988), providing an ethical climate in the organization in terms of norms, rules, culture, and policies may decrease the level of negativity in individuals. This theory describes detailed feelings that employees have about the organizational environment and its ethical content and issues, which may help to change employees’ turnover intention (Rothwell & Baldwin, Citation2007). Previous studies indicated that a caring climate had a significant positive direct and indirect impact on a number of organizational outcomes, including employees’ job performance, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and well-being (e.g. Filipova, Citation2011; Fu & Deshpande, Citation2014; Martin & Cullen, Citation2006; Okpara & Wynn, Citation2008). Based on ethical climate theory, Joe et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated that a strong perception of caring climate decreases employees’ turnover intention. It forms the basis of hypothesis 1 in the current study. People are less likely to quit their positions when they feel that they are working in a supportive environment with strong caring or benevolent values (e.g. Sims & Keon, Citation1997). Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

(H1) A perceived caring climate is negatively related to employees’ turnover intention.

The mediating role of coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion

Workplace incivility has been reported to be a highly prevalent interpersonal mistreatment in various workplaces (Lim et al., Citation2008; Porath & Pearson, Citation2013). According to previous studies, 77.6% of nurses in Canada (Spence Laschinger et al., Citation2009), and around 75% of 3000 employees in Sweden have experienced coworker incivility at work. Frontline service employees are particularly prone to coworker incivility in their daily working life. Coworker incivility refers to uncivil behavior by an employee towards his/her fellow coworker(s), such as not saying “please” or “thank you”, raising their voice, leaving rude messages, blaming others, spreading rumors, ignoring a coworker in the group, or any gestures that could be perceived as offensive (Pearson et al., Citation2001; Pearson et al., Citation2005).

Based on ethical climate theory, a perceived caring climate may create awareness and develop positive attitudes among employees (Kalafatoğlu & Turgut, Citation2019), and improve their morality, responsibility, and positive behaviors (Yang et al., Citation2014). It can stimulate employees to internally combine consistent, employee-supporting, and caring-oriented organizational values, which in turn affects internally directed outcomes (Kao et al., Citation2014). This means that working in a caring climate motivates employees to think more before acting, by considering the impact of their behaviors on others, especially their coworkers.

On the other hand, workplace incivility has been recognized as a factor in the undermining of social relationships and increasing employee turnover (Cortina et al., Citation2001; Lim et al., Citation2008; Taylor et al., Citation2017). Frontline employees require social acceptance and support from colleagues, especially those who work in service teams. Thus, coworkers’ unpleasant behaviors break down respect and social support and cause an imbalance in the network (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999), which in turn results in turnover intention (Viotti et al., Citation2018).

It has been previously demonstrated that a caring climate mitigated the negative effects of social stressors (e.g. workplace incivility) (Kao et al., Citation2014) and decreased employees’ misconduct (Mayer et al., Citation2010). Therefore, the perception of a caring climate may lead to a lower level of uncivil behavior among service employees. In addition, in organizations that develop caring systems through emotional support and social care, even when employees experience workplace incivility they are less intended to leave the organization (Kao et al., Citation2014). Therefore, in this study, we argue that coworker incivility could be considered as a mediator in the relationship between the perception of caring climate and turnover intention. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

(H2) The relationship between perception of caring climate and turnover intention is mediated by coworker incivility.

In the framework of spiraling incivility (Andersson & Pearson, Citation1999), the behavioral response of individuals to incivility illustrates a social interaction process involving interpersonal mistreatment (Lim et al., Citation2008; Sakurai & Jex, Citation2012), where the victims of incivility are more likely to become distressed (Lim et al., Citation2008) and eventually experience emotional exhaustion (Spence Laschinger et al., Citation2009; Taylor et al., Citation2017), which refers to a situation where an employee feels overextended emotionally and exhausted by his/her work (Wright & Cropanzano, Citation1998). Reduced or low quality in workplace life caused by emotional exhaustion is a strong factor resulting in turnover intention (Korunka et al., Citation2008). Employees who experience emotional exhaustion are most likely to show turnover intention and try to find job opportunities in other organizations (Bridger et al., Citation2013). However, based on ethical climate theory, providing an ethical climate in an organization may also reduce emotional exhaustion (Yang et al., Citation2014). Working in a caring climate and perception of support from the organization could be a significant emotional resource for the employees, which may help them to deal more effectively with emotional exhaustion resulting from experiencing uncivil behaviors in the workplace.

The conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989, Citation2001) is also a good theory to provide a better understanding of the relationship between the cause of stress and the loss of resources. Moreover, previous studies considered this theory as a useful theory for justifying emotional exhaustion as a mediator for turnover intention (e.g. Cole et al., Citation2010). COR theory posits that people try hard to acquire, maintain, and secure their resources including their emotional energy and socio-emotional support in the workplace (Hobfoll, Citation1989). However, these valuable resources are restricted in most cases and according to COR theory, the cognitive, emotional, and physical resources could be gradually lost when employees try to protect themselves while, for example, dealing with work stressors such as coworker incivility in the workplace (Hur et al., Citation2015). Such a decline in resources is an important part of emotional exhaustion (Neveu, Citation2007) and leads employees to become emotionally drained (Halbesleben & Bowler, Citation2007).

In service work environments with a caring climate, where managers provide emotional support for their employees and are concerned with their well-being, frontline employees who suffer from distress may end up with fewer resource losses and recover more quickly (Rathert et al., Citation2022; Stiehl et al., Citation2018). Based on COR theory this study proposes that providing a caring climate in the workplace facilitates a “pool” of emotional and psychological resources (Hobfoll, Citation2011), which helps employees to conserve their valuable resources and in turn, decreases their emotional exhaustion. Therefore, in this study, emotional exhaustion is also considered as a mediator in the relationship between the perception of caring climate and turnover intention by the following hypothesis:

(H3) The relationship between perception of caring climate and turnover intention is mediated by emotional exhaustion.

Moreover, given the arguments related to H2 and H3 and the relationship between the variables, we proposed the following hypothesis considering the serial mediating mechanisms of both coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion:

(H4) The relationship between perception of caring climate and turnover intention is serially mediated by employees’ perceptions of coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion.

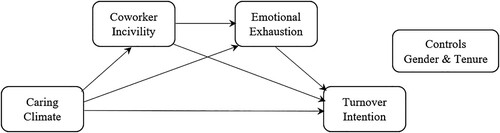

demonstrates the direct and indirect effects of a caring climate on turnover intention through serial multiple mediation of coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion.

Methodology

Sampling and procedure

The study used a quantitative approach with cross-sectional design and the non-probability purposive sampling technique (non-random), which relies on the judgment of the researcher (deliberate choice) to select people who are able and willing to provide necessary and relevant information for the study based on their knowledge or experience (Bernard, Citation2002). The respondents were undergraduate students studying tourism management and hotel management at a university. Based on the purpose of the study, eligible respondents were only the students who had work experience in the hotel or restaurant sectors in Norway, as full-time or part-time frontline service employees, for a minimum of six months prior to participation in the study. These frontline employees were front-desk agents, reservations agents, waiters or waitresses, and bartenders. The rationale for selecting frontline employees rather than other hotel and restaurant staff is because of their frequent face-to-face or voice-to-voice interactions with the customers/guests, which highlights their key role in improving customer satisfaction, building loyalty, managing customers’ requests, and solving their problems (Daskin, Citation2015). Due to the specific features of service jobs, including deep-rooted stress (Arasli et al., Citation2018), and a heavy reliance on coworkers (Sliter et al., Citation2012) to provide quality service for the customers, these employees are more likely to experience workplace incivility in their daily working life.

Data collection

A self-administrated questionnaire in English was distributed among respondents. Prior to survey distribution, the researcher provided a brief introduction of the study for the students and emphasized the eligibility conditions for the right respondents (as mentioned earlier). Thus, only eligible students received the survey and participated in the study. To pre-test the questionnaire, 10 master’s degree students in the same field were asked to complete the questionnaire two weeks before data collection in order to check the understandability of the items. Required changes were considered in the questionnaire. The first page of the questionnaire contained information about the purpose of the study and contact information, as well as a polite request encouraging them to participate in the research, emphasizing the voluntary nature of participation, and informing them of full anonymity and that the data would be treated confidentially. Completing the questionnaire took approximately 10–15 min.

The completed questionnaires were placed in a special box, which was subsequently collected by a researcher in order to make responses anonymous and confidential. This was done to reduce the potential threat of common method bias (CMB), which is highlighted in previous studies (Line & Runyan, Citation2012; Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). From 465 distributed questionnaires, 322 were returned, which corresponds to a 69.2 percent response rate. Questionnaires with more than 20 percent unanswered questions were considered as missing data. Consequently, 291 responses were used for data analysis.

Measurement

All constructs were measured using scales that are well-established in existing research. In order to measure the perception of a caring climate, 4 items were taken from Cullen et al. (Citation1993). A sample item states, “Our hotel primarily cares about what is best for each person”. The 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was used.

An extensive literature review was conducted to find the latest validated measurements for coworker incivility. To measure perceived coworker incivility, 4 items were used from Martin and Hine (Citation2005), who developed and validated the Uncivil Workplace Behavior Questionnaire (UWBQ) by evaluating several facets of perceived incivility related to hostility, privacy invasion, exclusionary behavior, and gossiping. They showed convergent, divergent, and concurrent validity of the measurement by collecting data from 368 employees of different workplaces in Australia. A sample item asks, “How often have your coworkers spoken to you in an aggressive tone of voice?”. The 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often) was used.

Three items were used from the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981) to measure emotional exhaustion. A sample item includes “I feel frustrated with my job”. Additionally, three items from Mitchel (Citation1981) were considered to measure turnover intention. Sample item: “I often think about leaving my job.” The 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was used for the last two variables. Gender and tenure were included as demographic variables.

Data analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Science (IBM SPSS) and AMOS, version 26, was used to analyze the collected data. First, descriptive statistics, correlations, and reliability were provided. A confirmatory test of the operationalization of constructs in the measurement model was then conducted in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS (Hair et al., Citation2010). The model fit was also assessed in AMOS. Moreover, in order to test the hypotheses, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used, which has the advantage of being more parsimonious than other methods, such as regression, as well as using both measurement and a structural model to test all the hypotheses at the same time (Hair et al., Citation2010).

Sixty-six percent of the respondents (n = 291) were female. More than half of the respondents (65%) were working in hotels and 35% were working in restaurants. Forty-four percent of them were waiters/waitresses, 41 percent were receptionists, 12 percent were bartenders, and only 2 percent were housekeeping staff. The majority of the respondents (78%) were part-time employees. More than 45 percent had one to three years of work experience, followed by 22 percent who had six to eleven months, 17 percent had four to five years, and only 15 percent had more than five years of experience (see ).

Table 1. Demographic profile of the respondents (n = 291).

Results

Measurement results

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) are available in including standardized factor loadings (FL), composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and maximum shared squared variance (MSV). The study measurements were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale and the reliability was evaluated through Cronbach’s Alpha. Values were all above the threshold value of 0.60 (from 0.70–0.89). The first test for model validity showed convergent and discriminant validity issues for turnover intention since the AVE (0.48) was less than 0.50, which indicated a convergent validity issue, while its MSV (0.53) was more than AVE indicating a discriminant validity issue (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

Table 2. The confirmatory factor analysis results.

Thus, we dropped the first item for turnover intention (TI1) as this was the most problematic item, and removing it has the least impact on the reliability of turnover intention (Cronbach’s α = 0.71, still ideal). We then checked the model validity again, and both issues had been solved as the AVE was higher (0.61) and the new MSV (0.51) was less than the AVE (see ). The AVE for coworker incivility was also less than 0.50, indicating convergent validity. However, the average variance extracted is often very strict compared to composite reliability, which is a more forgiving measure. Since the CR value for coworker incivility was equal to its minimum recommended threshold of 0.70, we, therefore, concluded that this showed convergent validity for multi-purposing based on CR alone (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Malhotra & Dash, Citation2011). According to Kline (Citation2005), discriminant validity is also confirmed when the estimated correlations between the variables are less than 0.85 (see ). The descriptive statistics and correlations are also demonstrated in . Based on the results available in and , reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity for the current study are established.

Table 3. Mean, standard deviations, correlations, and collinearity statistics of the study variables (n = 291).

The model fit indices for the four-factor structure (χ2 = 76.65, df = 59, χ2/df = 1.30, NFI = 0.95, RMR = 0.03, GFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.98) were acceptable (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). As suggested by Hu and Bentler (Citation1999), the comparative fit index (CFI = 0.99, values > 0.95 indicate excellent fit), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.03, values < 0.06 indicate excellent fit, and PClose = 0.94, values > 0.05 indicate excellent fit), and (SRMR = 0.04, values < 0.08 indicate excellent fit) are perfectly acceptable.

To measure the problem of common method bias (CMB) we used Harman’s single-factor test, which is about a condition in which a single latent factor explains more than 50 percent of the total variance of the construct measures (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). The result was 30.19 percent. Moreover, in line with a new approach suggested by Kock (Citation2015), we used multicollinearity as a test for method bias through checking the variable inflation factors (VIF). This approach is used due to the fact that multicollinearity is a symptom of method bias and if a collinearity test shows that all VIFs are equal or less than 3.30 it can be concluded that the model is free of potential CMB (Kock, Citation2015, p. 7). The results of the collinearity test are shown in the last two columns of . All tolerance values are more than 0.20 and all VIFs are less than 3.30, indicating that there is no multicollinearity problem and consequently no common method bias.

Test of the hypotheses

The results of the Pearson correlation in showed that a perceived caring climate had a significant negative correlation with coworker incivility, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention. Coworker incivility had a significant positive correlation with emotional exhaustion and turnover intention. The correlation between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention was also positive and significant. Thus, the result shows preparatory support for H1.

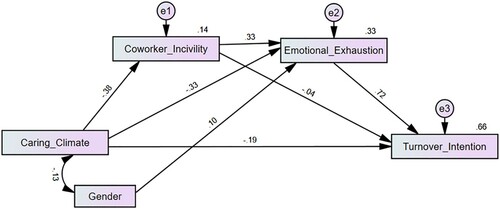

In order to test the mediating hypotheses, the SEM analysis was performed in AMOS and the hypothetical structural model () was tested. Additionally, gender was included as a control variable since it was closely associated with emotional exhaustion in the current data. Furthermore, the coefficients of the three-path mediated effect were simultaneously estimated (Hayes et al., Citation2011; Taylor et al., Citation2008) through the plugin (Gaskin et al., Citation2020) in the structural equation modeling () and the results are presented (see ). This approach separates the indirect effect of the mediators: coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion, as well as finding the indirect effect passing through both mediators in a serial multiple mediation (Taylor et al., Citation2008). To estimate the significance of the indirect effect, 5000 bootstrap resamples were run (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008), and to consider the effect as significant, the 95% CI should not include zero. Estimated direct and indirect effects for all the paths are shown in and .

Table 4. Structural equation modeling (SEM) results for the serial multiple mediation model.

According to the results, a perceived caring climate had a significant negative effect on turnover intention directly (β = −0.52, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.58, −0.44]) and indirectly (β = −0.19, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.26, −0.12]), which provides collateral evidence for H1, and thus H1 was supported. H2 predicted a mediation effect of coworker incivility in the relationship between caring climate and turnover intention. The coefficient value for this relationship is β = 0.01 with the insignificant p-value (p = 0.33, 95% CI = [−0.01, 0.03]), and thus H2 was not supported. However, when we ran this model independent of emotional exhaustion, the mediation of coworker incivility in this path became significant (β = −0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.09, −0.03]). H3, which predicted the mediation effect of emotional exhaustion in the relationship between caring climate and turnover intention was supported since β = −0.24 and it is significant (p < 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.24, −0.12]).

Finally, in H4 we predicted that the relationship between a perceived caring climate and turnover intention is serially mediated by coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion. The result revealed that coworker incivility mediates the relationship between caring climate and emotional exhaustion (β = −0.12, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.16, −0.08]), and subsequently emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between coworker incivility and turnover intention (β = 0.24 p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.25, 0.45]). The formal test for H4 showed a significant coefficient value for this serial mediation path (β = −0.12, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.09, −0.04]), and thus the result provided evidence for H4 supporting the serial mediation effect of coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion in the relationship between caring climate and turnover intention. The effect size was 66.20%.

Discussion

Given that there is still a lack of research on the antecedents of service employees’ turnover and the potential role of workplace climate in relation to turnover intention (Demirtas & Akdogan, Citation2015; Joe et al., Citation2018), this study focused on how employees’ turnover intention is deeply affected by their perception of a caring climate in the workplace.

Our results showed that a perceived caring climate decreases the employees’ turnover intention in line with ethical climate theory. Employees who feel cared for and supported in the workplace are less likely to leave their current job. This results from a reduction in both coworker incivility and employees’ emotional exhaustion (Yang et al., Citation2014). Working in a caring climate stimulates positive behavior and friendship among employees through concern for the rights, interests, and well-being of others, while simultaneously reducing uncivil behavior towards coworkers. We also showed that if employees believe that the organization really cares about them and their well-being in a supportive work environment, they will be less likely to feel emotionally exhausted. Emotional exhaustion caused by workplace incivility is a resource-draining component of COR theory while a positive atmosphere within a caring climate, which helps to reduce employees’ uncivil behaviors and negative feelings, is a supplementary emotional resource, that consequently leads them to stay in the organization.

Based on the results, a perceived caring climate had a significant negative effect on employees’ turnover intention directly (H1) and indirectly only through emotional exhaustion (H3), and serially through both coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion (H4). Moreover, the results revealed that emotional exhaustion partially mediated the negative effect of a caring climate on turnover intention since the beta for caring climate decreased but remained significant after adding emotional exhaustion as a mediator in the model. This result complements the study by Yang et al. (Citation2014), which found that emotional exhaustion partially mediates the effect of ethical climate on turnover intention. H2 was rejected and the findings showed that coworker incivility did not show a mediation effect in the relationship between caring climate and turnover intention. However, the mediating effect of coworker incivility became significant when we removed emotional exhaustion from the model and checked the model only with one mediator (i.e. coworker incivility). This indicates that emotional exhaustion has a higher positive effect on turnover intention than coworker incivility as well as a stronger mediating effect between caring climate and turnover intention. Yet, we should not underestimate the importance of coworker incivility as a mediator in the mentioned relationship, since the results clearly confirmed the exclusive mediating effect of coworker incivility (independent of emotional exhaustion) as well as its mediating effect in the serial mediation model (H4). Considering the sources of workplace incivility (Cortina et al., Citation2001), some previous studies showed that employees’ outcomes are less affected by coworker incivility compared to supervisor and customer incivility, because coworker incivility may be perceived as a less threatening – but still significant harmful– job stressor (e.g. Cho et al., Citation2016; Sliter et al., Citation2011). It has been also clearly evidenced in previous studies that emotional exhaustion is a strong factor leading to turnover intention (Babakus et al., Citation2008; Hur et al., Citation2015; Korunka et al., Citation2008; Yang et al., Citation2014). Moreover, employees could feel emotionally exhausted not only through workplace coworker incivility but also through other sources of incivility such as customer incivility (Alola et al., Citation2021) or other negative factors or events in the workplace, such as increased work demands (Babakus et al., Citation2008) or job insecurity (Lawrence & Kacmar, Citation2017).

Theoretical implications

Supported by ethical climate theory and COR theory, our serial multiple mediation model provides useful findings to complement the turnover and workplace incivility literature. This study contributes to our knowledge of frontline service employees’ perceptions of a caring climate, and extends our understanding of the role of workplace climate on individuals’ attitudes and behaviors (Demirtas & Akdogan, Citation2015; Joe et al., Citation2018).

Most previous studies concentrated on the moderating effect of a caring climate in the organization (e.g. Chen et al., Citation2013; Kao et al., Citation2014; Liu et al., Citation2019). However, this study contributes to ethical climate theory (Victor & Cullen, Citation1988) by focusing on the effect of caring climate perception (as a specific type of ethical climate) and its established behavioral mechanism, which leads to lower levels of turnover intention among frontline service employees (Joe et al., Citation2018). Our results develop a better understanding of the conditions under which uncivil behaviors are less likely to occur while providing further support for earlier studies about the antecedent role of a caring climate in the formation of turnover intention (e.g. Joe et al., Citation2018; Sims & Keon, Citation1997).

Moreover, the result of this study contributes to COR theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989, Citation2001). Our model assumed that a caring climate in the workplace serves as a resource pool (Hobfoll, Citation2011), which could compensate for employees’ resource loss resulting from dealing with workplace incivility. Our result shows that the perception of a caring climate could work as a supplementary emotional resource for employees, which enables them to have more control over their emotions, increases their tolerance toward others’ uncivil behaviors (Kalafatoğlu & Turgut, Citation2019), and leads them to be less emotionally exhausted (Sakurai & Jex, Citation2012) and reduces the level of turnover intention (Podsakoff et al., Citation2007).

Finally, our novel result regarding a serial mediation effect provides a broader view of the relationship between a caring climate and employees’ turnover intention. With a contribution to ethical climate theory and COR theory, this study revealed the mediation mechanism of both coworker incivility and emotional exhaustion, from the frontline service employees’ perspective (Namin et al., Citation2022; Poddar & Madupalli, Citation2012).

Managerial implications

The current study gives the following suggestions for service managers to improve the workplace environment and decrease employees’ turnover intention.

It would be helpful to provide a positive climate in the organization. The moral content of the organizational climate can influence employees’ moral development as it teaches them appropriate behavior in the organization through climate perceptions (Liu et al., Citation2019). The ethical climate is a specific work climate that steers ethical behavior within an organization, and among its dimensions, the caring climate has the strongest correlation with ethical behavior (Fu & Deshpande, Citation2014; Shapira-Lishchinsky & Even-Zohar, Citation2011), including responsibility, trust, high moral standards, well-being, increased tolerance for others’ weaknesses, and positive attitudes (Kalafatoğlu & Turgut, Citation2019; Martin & Cullen, Citation2006).

A caring climate seems particularly important for frontline service employees because of their serious roles in providing a service to customers through team working and a strong reliance on each other (Sliter et al., Citation2012). Thus, service managers may benefit from establishing a particular ethical climate in the workplace mainly based on caring aspects, in which employees’ main consideration is the effect of beneficial decisions on others who are involved in the decision-making as opposed to their self-interest (Cullen et al., Citation2003). A strong caring climate prevents unethical and uncivil behaviors whilst simultaneously motivating frontline employees to behave well by improving their values, assumptions, and belief systems, which in turn will minimize their turnover intention (Kao et al., Citation2014). Since the high turnover rate in the service industry is a major issue, harming both the individual and organizational outcomes (Deloitte, Citation2010), managers can use a caring climate to steer the employees into the intention to stay in their current job rather than quitting (Joe et al., Citation2018).

Given that coworker incivility has a detrimental effect on employees’ turnover intention, it should be considered not only as a personal-level conflict but also as a structural issue that requires serious attention. It is necessary to control the hiring process by being aware of employees’ attributes, and those displaying uncivil behavior towards coworkers could be identified and stopped. Managers may formulate policies and establish appropriate regulations and behavioral criteria (Yang et al., Citation2014). Service managers first need to properly identify unique types and patterns of uncivil behavior among employees in the workplace and recognize how they feel and react to coworker incivility. Providing adequate education within the organization is, therefore, an important task for the managers. This education could increase awareness of the damaging effects of employees’ uncivil behavior towards others in the workplace and teach them more professional etiquette (Hur et al., Citation2015).

When employees perceive there to be a caring climate and feel supported by the organization, their depletion of emotional resources will gradually decrease while their work devotion will increase. Service managers’ promotion of personal ethics may prevent individual employees from engaging in uncivil behavior. Moreover, care and social support from managers to those employees who have faced workplace incivility would substantially improve their work effort (Sakurai & Jex, Citation2012). Organizing meetings or weekend gatherings could be beneficial for employees and raise their awareness of the expected and correct ethics and the relevant measures in the organization. The CREW (Civility, Respect, and Engagement in the Workforce) initiative is one of the programs that can be implemented to facilitate civil interactions among employees (Taylor & Kluemper, Citation2012), and includes recognizing and improving controversial workplace interactions and reforming teamwork and cooperation.

Limitations and future research suggestion

Although this study provided useful results and discussed theoretical and practical implications, it is not without limitations. The first limitation is related to the cross-sectional design that is required to maintain caution when discerning a causal relationship between the variables. A longitudinal study would be necessary to control this limitation.

The number of the respondents was quite good however, the replication of this study with a larger dataset would resolve the lack of generalization of the findings. Using the self-reported measures for the variables in the current study is another limitation, which may result in unavoidable response biases. Moreover, since this study was an early effort to investigate the relationship between a perceived caring climate and employee turnover intention, it is recommended that the results from similar studies of frontline service employees are compared in different national contexts to provide collateral evidence for our results. Workplace climate is an interesting area to be examined in relation to workplace incivility (Kao et al., Citation2014; Schilpzand et al., Citation2016), therefore future studies could investigate the effect of other workplace climates (e.g. ethical climate) on different sources of workplace incivility. One suggestion could be testing the relationship between caring climate and supervisor incivility, or how the perception of a caring climate can affect the employees’ incivility towards customers.

Future studies could also focus on the cultural differences in perceptions of the workplace climate and workplace incivility (Vasconcelos, Citation2020). The investigation is also recommended into the effect of a caring climate on other work-related outcomes, such as employees’ job performance and satisfaction in the same serial multiple mediation model.

Conclusion

This study emphasized the significant role of the work environment (i.e. workplace climate) in decreasing the frontline employees’ turnover intention in the service industry. Providing a caring climate focused on employees’ well-being and emotional support in the workplace negatively affects employees’ uncivil behaviors (towards each other) and their emotional exhaustion caused by experiencing workplace incivility. Service managers need to consider a caring climate as a good solution for reducing incivility and negative feelings among employees, which consequently helps to minimize the level of turnover intention in the organization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abubakar, A. M., Namin, B. H., Harazneh, I., Arasli, H., & Tunç, T. (2017). Does gender moderate the relationship between favoritism/nepotism, supervisor incivility, cynicism and workplace withdrawal: A neural network and SEM approach. Tourism Management Perspectives, 23(7), 129–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.06.001

- Alola, U. V., Avcı, T., & Öztüren, A. (2021). The nexus of workplace incivility and emotional exhaustion in hotel industry. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(3), e2236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2236

- Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. The Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/259136

- Arasli, H., Hejraty Namin, B., & Abubakar, A. M. (2018). Workplace incivility as a moderator of the relationships between polychronicity and job outcomes. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(3), 1245–1272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2016-0655

- Babakus, E., Yavas, U., & Karatepe, O. M. (2008). The effects of job demands, job resources and intrinsic motivation on emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions: A study in the Turkish hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 9(4), 384–404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480802427339

- Bai, Q., Lin, W., & Wang, L. (2016). Family incivility and counterproductive work behavior: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and emotional regulation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94(6), 11–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.02.014

- Bernard, H. R. (2002). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Alta Mira Press.

- Bridger, R. S., Day, A. J., & Morton, K. (2013). Occupational stress and employee turnover. Ergonomics, 56(11), 1629–1639. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2013.836251

- Chen, C. C., Chen, M. Y. C., & Liu, Y. C. (2013). Negative affectivity and workplace deviance: The moderating role of ethical climate. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(15), 2894–2910. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.753550

- Cho, M., Bonn, M. A., Han, S. J., & Lee, K. H. (2016). Workplace incivility and its effect upon restaurant frontline service employee emotions and service performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(12), 2888–2912. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2015-0205

- Cole, M. S., Bernerth, J. B., Walter, F., & Holt, D. T. (2010). Organizational justice and individuals’ withdrawal: Unlocking the influence of emotional exhaustion. Journal of Management Studies, 47(3), 367–390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00864.x

- Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2009). Patterns and profiles of response to incivility in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(3), 272–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014934

- Cortina, L. M., Magley, V. J., Williams, J. H., & Langhout, R. D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.6.1.64

- Cullen, J. B., Parboteeah, K. P., & Victor, B. (2003). The effects of ethical climates on organizational commitment: A two-study analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 46(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025089819456

- Cullen, J. B., Victor, B., & Bronson, J. W. (1993). The ethical climate questionnaire: An assessment of its development and validity. Psychological Reports, 73(2), 667–674. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1993.73.2.667

- Daskin, M. (2015). Antecedents of extra-role customer service behaviour: Polychronicity as a moderator. Anatolia, 26(4), 521–534. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2014.996762

- Deloitte. (2010). Hospitality 2015: Game changers or spectators? Deloitte.

- Demirtas, O., & Akdogan, A. A. (2015). The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2196-6

- Dessler, G. (2011). Human Resource management (12th ed). Prentice-Hall.

- Filipova, A. A. (2011). Relationships among ethical climates, perceived organizational support, and intent-to-leave for licensed nurses in skilled nursing facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 30(1), 44–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464809356546

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fu, W., & Deshpande, S. P. (2012). Factors impacting ethical behavior in a Chinese state-owned steel company. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(2), 231–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0962-2

- Fu, W., & Deshpande, S. P. (2014). The impact of caring climate, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment on job performance of employees in a China’s insurance company. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(2), 339–349. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1876-y

- Gaskin, J., James, M., & Lim, J. (2020). “Indirect Effects”, AMOS Plugin.

- Gjerald, O., Dagsland, ÅHB, & Furunes, T. (2021). 20 years of nordic hospitality research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1880058

- Griffin, B. (2010). Multilevel relationships between organizational-level incivility, justice and intention to stay. Work & Stress, 24(4), 309–323. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2010.531186

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed). Pearson.

- Halbesleben, J. R., & Bowler, W. M. (2007). Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.93

- Hayes, A. F., Preacher, K. J., & Myers, T. A. (2011). Mediation and the estimation of indirect effects in political communication research. Sourcebook for Political Communication Research: Methods, Measures, and Analytical Techniques, 23(1), 434–465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203938669

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 116–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hur, W. M., Kim, B. S., & Park, S. J. (2015). The relationship between coworker incivility, emotional exhaustion, and organizational outcomes: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries, 25(6), 701–712. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20587

- Jin, D., Kim, K., & DiPietro, R. B. (2020). Workplace incivility in restaurants: Who’s the real victim? Employee deviance and customer reciprocity. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 86, 102459. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102459

- Joe, S. W., Hung, W. T., Chiu, C. K., Lin, C. P., & Hsu, Y. C. (2018). To quit or not to quit understanding turnover intention from the perspective of ethical climate. Personnel Review, 47(5), 1067–1081. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2017-0124

- Kalafatoğlu, Y., & Turgut, T. (2019). Individual and organizational antecedents of trait mindfulness. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 16(2), 199–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2018.1541756

- Kao, F. H., Cheng, B. S., Kuo, C. C., & Huang, M. P. (2014). Stressors, withdrawal, and sabotage in frontline employees: The moderating effects of caring and service climates. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(4), 755–780. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12073

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed). The Guilford Press.

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Korunka, C., Hoonakker, P., & Carayon, P. (2008). Quality of working life and turnover intention in information technology work. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries, 18(4), 409–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20099

- Lai, F. Y., & Chen, H. L. (2016). Role of leader–member exchange in the relationship between customer incivility and deviant work behaviors: A moderated mediation model. SMA Proceedings, 49–58. https://www.societyformarketingadvances.org/resources/Documents/Resources/Conference%20Proceedings/SMA2016_v11.pdf#page=49

- Lawrence, E. R., & Kacmar, K. M. (2017). Exploring the impact of job insecurity on employees’ unethical behavior. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(1), 39–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2016.58

- Lim, S., Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2008). Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 95–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.95

- Line, N. D., & Runyan, R. C. (2012). Hospitality marketing research: Recent trends and future directions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(2), 477–488. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.07.006

- Liu, W., Zhou, Z. E., & Che, X. X. (2019). Effect of workplace incivility on OCB through burnout: The moderating role of affective commitment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(5), 657–669. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9591-4

- Lundberg, C., & Furunes, T. (2021). 20 years of the Scandinavian journal of hospitality and tourism: Looking to the past and forward. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1883235

- Malhotra, N. K., & Dash, S. (2011). Marketing research an applied orientation. Pearson Publishing.

- Martin, K. D., & Cullen, J. B. (2006). Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 69(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9084-7

- Martin, R. J., & Hine, D. W. (2005). Development and validation of the uncivil workplace behavior questionnaire. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(4), 477–490. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.477

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

- Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., & Greenbaum, R. L. (2010). Examining the link between ethical leadership and employee misconduct: The mediating role of ethical climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0794-0

- Miner-Rubino, K., & Reed, W. D. (2010). Testing a moderated mediational model of workgroup incivility: The roles of organizational trust and group regard. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(12), 3148–3168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00695.x

- Mitchel, J. O. (1981). The effect of intentions, tenure, personal, and organizational variables on managerial turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 24(4), 742–751. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/256173

- Namin, B. H., Øgaard, T., & Røislien, J. (2022). Workplace incivility and turnover intention in organizations: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010025

- Neveu, J. P. (2007). Jailed resources: Conservation of resources theory as applied to burnout among prison guards. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 28(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.393

- Okpara, J. O., & Wynn, P. (2008). The impact of ethical climate on job satisfaction, and commitment in Nigeria: Implications for management development. Journal of Management Development, 27(9), 935–950. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710810901282

- Paek, S., Schuckert, M., Kim, T. T., & Lee, G. (2015). Why is hospitality employees’ psychological capital important? The effects of psychological capital on work engagement and employee morale. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 50(9), 9–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.07.001

- Panwar, S., Dalal, J. S., & Kaushik, A. K. (2012). High staff turnover in hotel industry, due to low remunerations and extended working hours. VSRD International Journal of Business & Management Research, 2(3), 81–89.

- Pearson, C. M., Andersson, L. M., & Porath, C. L. (2005). Workplace incivility. In Suzy Fox Paul E. Spector (Ed.), Counterproductive work behavior: Investigations of actors and targets (pp. 177–200). American Psychological Association.

- Pearson, C. M., Andersson, L. M., & Wegner, J. W. (2001). When workers flout convention: A study of workplace incivility. Human Relations, 54(11), 1387–1419. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267015411001

- Poddar, A., & Madupalli, R. (2012). Problematic customers and turnover intentions of customer service employees. Journal of Services Marketing, 26(7), 551–559. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041211266512

- Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 438–454. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.438

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Porath, C., & Pearson, C. (2013). The price of incivility. Harvard Business Review, 91(1-2), 115–121.

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Rathert, C., Ishqaidef, G., & Porter, T. H. (2022). Caring work environments and clinician emotional exhaustion: Empirical test of an exploratory model. Health Care Management Review, 47(1), 58–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000294

- Reio, T. G., Jr., & Ghosh, R. (2009). Antecedents and outcomes of workplace incivility: Implications for human resource development research and practice. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 20(3), 237–264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20020

- Rothwell, G. R., & Baldwin, J. N. (2007). Ethical climate theory, whistle-blowing, and the code of silence in police agencies in the state of Georgia. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(4), 341–361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9114-5

- Sakurai, K., & Jex, S. M. (2012). Coworker incivility and incivility targets’ work effort and counterproductive work behaviors: The moderating role of supervisor social support. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17(2), 150–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027350

- Schilpzand, P., De Pater, I. E., & Erez, A. (2016). Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37, 57–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1976

- Shapira-Lishchinsky, O., & Even-Zohar, S. (2011). Withdrawal behaviors syndrome: An ethical perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(3), 429–451. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0872-3

- Sims, R. L., & Keon, T. L. (1997). Ethical work climate as a factor in the development of person-organization fit. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(11), 1095–1105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017914502117

- Sliter, M., Sliter, K., & Jex, S. (2012). The employee as a punching bag: The effect of multiple sources of incivility on employee withdrawal behavior and sales performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.767

- Sliter, M. T., Pui, S. Y., Sliter, K. A., & Jex, S. M. (2011). The differential effects of interpersonal conflict from customers and coworkers: Trait anger as a moderator. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(4), 424–440. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023874

- Spence Laschinger, H. K., Leiter, M., Day, A., & Gilin, D. (2009). Workplace empowerment, incivility, and burnout: Impact on staff nurse recruitment and retention outcomes. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(3), 302–311. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.00999.x

- Stiehl, E., Ernst Kossek, E., Leana, C., & Keller, Q. (2018). A multilevel model of care flow: Examining the generation and spread of care in organizations. Organizational Psychology Review, 8(1), 31–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386617740371

- Taylor, A. B., MacKinnon, D. P., & Tein, J. Y. (2008). Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 241–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428107300344

- Taylor, S. G., Bedeian, A. G., Cole, M. S., & Zhang, Z. (2017). Developing and testing a dynamic model of workplace incivility change. Journal of Management, 43(3), 645–670. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314535432

- Taylor, S. G., & Kluemper, D. H. (2012). Linking perceptions of role stress and incivility to workplace aggression: The moderating role of personality. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17(3), 316–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028211

- Vasconcelos, A. F. (2020). Workplace incivility: A literature review. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 13(5), 513–542. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-11-2019-0137

- Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1987). A theory and measure of ethical climate in organizations. In W. C. Frederick (Ed.), Research in corporate social performance and policy (pp. 51–71). JAI Press.

- Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1), 101–125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2392857

- Viotti, S., Converso, D., Hamblin, L. E., Guidetti, G., & Arnetz, J. E. (2018). Organisational efficiency and co-worker incivility: A cross-national study of nurses in the USA and Italy. Journal of Nursing Management, 26(5), 597–604. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12587

- Wilson, N. L., & Holmvall, C. M. (2013). The development and validation of the incivility from customers scale. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(3), 310–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032753

- Wright, T. A., & Cropanzano, R. (1998). Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(3), 486–493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.486

- Yang, F. H., Tsai, Y. S., & Tsai, K. C. (2014). The influences of ethical climate on turnover intention: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 6(4), 72–89.

- Yavas, U., Karatepe, O. M., & Babakus, E. (2011). Efficacy of job and personal resources across psychological and behavioral outcomes in the hotel industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 10(3), 304–314. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2011.555881