ABSTRACT

Online travel reviews play a vital role in the formation of a destination image. However, the mechanism of how that happens is still relatively unknown. Drawing on the elaboration likelihood model and the cognitive–affective-conative model of destination image, this study aims to explore the impact of specific travel review attributes on cognitive, affective, and conative images through the central route and the peripheral route of persuasion. An experiment design survey with four scenarios (i.e. concrete vs. abstract × 5-star rating vs. 1-star rating) was applied in this study. A total of 1,305 Chinese participants were involved in this experiment, and compared their perception of Santa Claus Village, Finland, before and after reading different scenarios’ travel reviews. The results reveal that high rating reviews change cognitive image much more than low rating reviews. Low rating reviews have a large impact on the affective image. Under the high rating scenario, the concrete travel review improves the destination image more than the abstract travel review. Under the low rating scenario, the deterioration of abstract travel review on destination image is larger than concrete travel review. Moreover, both the central and peripheral cues of travel reviews affect tourist destination image formation.

Introduction

Social media is one of the most important sources of information for tourists. Especially opinions from peers obtained through online travel reviews are highly influential in the tourism decision-making process (Nowacki & Niezgoda, Citation2020). Online travel reviews are typically not controlled by destination marketers and are thus considered more truthful (Munar, Citation2012). When tourists read online travel reviews and thus obtain information, their image of destinations and businesses changes (Nowacki & Niezgoda, Citation2020). It is thus important to know why online travel reviews are so powerful in affecting destination image.

Only a few empirical studies explored how travel reviews affect tourists’ perception of destinations and travel behaviour (Abubakar et al., Citation2017; de la Hoz-Correa & Muñoz-Leiva, Citation2019; Reza Jalilvand et al., Citation2012). In these few studies, the main focus was to explore the relationship between online travel reviews and destination images in general. However, online travel reviews have a complex structure, including different kinds of attributes related to the platform, content, and author (Ukpabi & Karjaluoto, Citation2018). The influence of different review attributes on the destination image has been mostly ignored. Additionally, according to the fundamental destination image theory proposed by Gartner (Citation1994), three distinctly different components (cognitive, affective and conative) construct a destination image.

Destination image, and thus travel behaviour, change as people obtain new information. According to the elaboration likelihood model, the individual information adoption process is based on two qualitatively distinct persuasive routes, a central persuasive route and a peripheral persuasive route (Petty et al., Citation1981; Zablocki et al., Citation2019). The central route occurs when an individual considers the arguments related to the issues seriously and thoughtfully (Filieri et al., Citation2018a). The peripheral route occurs when an individual follows simple cues rather than information content itself (Filieri et al., Citation2018a). The model has been successfully adopted in social media research (Chung et al., Citation2015; Filieri et al., Citation2018; Filieri & McLeay, Citation2014; Tseng & Wang, Citation2016; Wang, Citation2015), suggesting that it could also explain the effects of online travel reviews on destination image.

Thus, this research examines how online travel reviews affect the destination image components of potential tourists. We hypothesize that usage of central and peripheral routes of information processing in the elaboration likelihood model (Petty et al., Citation1981) can explain the effect and provide us with a better understanding of how destination image is formed in the minds of tourists. In summary, the purpose of this paper is to understand how online travel reviews change the tourists’ perception of a destination, in the case of Santa Claus Village, Finland. From all travel review attributes, two key attributes were selected in this study, namely, review concreteness and review rating attributes. We apply an experimental design survey to detect how the destination image changes after tourists read online travel reviews containing specific review attributes.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Destination image

Destination image is an internally accepted mental construction (Gartner, Citation1994). It forms when a tourist acquires and processes destination information from various sources over time (Baloglu & McCleary, Citation1999). Destination image is generally considered to have a multi-dimensional structure of three interrelated components, including cognitive image, affective image, and conative image (Gartner, Citation1994). Cognitive image refers to the knowledge of the destination, specifically, it refers to tourists’ perception of destination attributes (Andersen et al., Citation2018). The affective image represents the feelings that tourists hold about these destination attributes (Andersen et al., Citation2018; Kim et al., Citation2017). The conative image represents the behaviour intention of tourists for future behaviour (Agapito et al., Citation2013).

The formation of the destination image is a dynamic process, affected by psychological and social personal factors as well as information about the destination (Beerli & Martín, Citation2004a). A destination image is constructed by constantly absorbing destination information from various channels (Beerli & Martı́n, Citation2004b). Research has found that emotional destination information has a more positive effect on destination image than non-emotional information (Rodríguez-Molina et al., Citation2015). Tourists seem to use especially utilitarian information and hedonic information when constructing a destination image (Tang & Jang, Citation2014). However, there is a limit to how much utilitarian information can change the destination image. If tourists are highly familiar with the destination, adopting more destination information may not enhance the cognitive image anymore (Tan & Wu, Citation2016). Sometimes it seems easier to change the affective images and the conative image than to change the cognitive image (Li et al., Citation2009; Shani et al., Citation2010). Li et al. (Citation2009) proved that when participants search for destination information for a whole week to make their travel plan, the participants’ affective image has been positively improved, while the cognitive image remains unchanged.

Elaboration likelihood model

According to earlier studies, it seems clear that adopting information, especially through online travel reviews affects various components of the destination image. Earlier studies suggest that the elaboration likelihood model can explain why and how this effect happens (Filieri, et al., Citation2018; Filieri & McLeay, Citation2014). The elaboration likelihood model is a dual-process model proposed by Petty and Cacioppo (Citation1986) that explains how individuals process persuasive information. This model states that a person’s attitudes can be changed according to two basic routes: the central route and the peripheral route (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). In tourism studies, tourists (in a high elaboration likelihood situation) will take the central route and assess the destination-related information critically (Filieri et al., Citation2018). This central process is greatly affected by the argument quality of the destination information (Filieri et al., Citation2018). Conversely, in the peripheral route, tourists (in a low elaboration likelihood situation) just spend less cognitive effort on their attitude toward the destination information (Filieri et al., Citation2018). This peripheral process is mainly influenced by simple cues, such as the volume and variance of travel reviews (Zablocki et al., Citation2019). Theoretically, tourists may simply adopt destination information either through the central or peripheral route. In practice, tourists may take these two routes at the same time to adopt destination information (Filieri, et al., Citation2018; Filieri & McLeay, Citation2014).

Shu and Scott (Citation2014) found the argument quality of the central route had a larger influence on tourists’ perception of the destination than the source credibility of the peripheral route in social media. Wang (Citation2015) further validated this view and pointed out that tourists’ intention to visit was determined by the argument quality of the central route, but tourists’ intention to recommend behaviour was determined by the source credibility of the peripheral route. However, some studies have shown that the central route and the peripheral route work together in affecting destination information adoption and destination perception (Chung et al., Citation2015; Filieri, et al., Citation2018; Filieri & McLeay, Citation2014; Tseng & Wang, Citation2016). For example, Tang and Jang (Citation2014), from the perspective of information value, pointed out that both the utilitarian information of the central route and the hedonic information of the peripheral route has a significant impact on destination perception. Filieri, et al. (Citation2018) and Filieri and McLeay (Citation2014) also found tourists judge the usefulness of travel review through both central (information quality) and peripheral routes (ranking score). Although earlier studies have applied the elaboration likelihood model in the tourism field, the model has not been connected to destination image studies in the context of online travel reviews.

The attributes of online travel reviews

Researchers widely recognize that destination information is significant in the image formation and image changes (Li et al., Citation2009; Wong et al., Citation2016; Zablocki et al., Citation2019). Among all the destination information sources, online travel reviews have been identified as a major factor in image formation (de la Hoz-Correa & Muñoz-Leiva, Citation2019). Most travel review platforms (e.g. TripAdvisor, Google reviews, Yelp) and online travel agent websites (e.g. Expedia and Ctrip) provide destination information for tourists through travel reviews. Tourists can freely access these platforms and get more information about the destination by reading the review content (González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2016). Online travel reviews have various attributes such as source credibility, review concreteness, review valence, review length, review rating and many others which all make travel reviews a complex research topic (Ukpabi & Karjaluoto, Citation2018).

Review concreteness attribute of the central route

Information quality of travel review is regarded as the important central route in tourist information processing (Filieri, Citation2015; Filieri & McLeay, Citation2014). Review concreteness attribute, as the basic review attribute of information quality, is critical in influencing destination information adoption and destination perception (Shin et al., Citation2019). Review concreteness attribute was defined as “a type of textual content specificity ranging from objective facts (concrete) to abstract and emotional content based on subjective experience (abstract)” (Shin et al., Citation2019, p. 579). The review concreteness attribute refers to two types of travel review: concrete travel review (objective) and abstract travel review (subjective) (Li et al., Citation2013). The concrete travel review represents the factuality of a destination (Shin et al., Citation2019), it is written based on logic and specific facts about the destination (Filieri, Citation2015). Therefore Li et al. (Citation2013) believed that the concrete travel review is always more useful than the abstract travel review in the tourist information adoption process. However, the abstract travel review involves personal subjective judgments and thinking about the trip (Shin et al., Citation2019). When tourists focus on the perception of subjective travelling experiences or sentiments, the abstract travel review is more influential than the concrete travel review (Shin et al., Citation2019). Whatever the case, earlier studies commonly agree that the review concreteness attribute of the central route has a great effect on the perception of the destination and affects the behaviour intentions of tourists. Accordingly, the hypotheses of the study are as follows:

Hypotheses 1, 2, 3: Review concreteness significantly influences the cognitive image (H1), the affective image (H2), and the conative image (H3) of a tourism destination.

Review rating attribute of the peripheral route

Generally, on many platforms such as TripAdvisor, when tourists post online travel reviews, they evaluate their positive or negative feelings about the experienced destination attributes with a five-star rating scale. Therefore, review rating does not refer to the quality of the review information but is rather an information shortcut concerning how tourists have evaluated a specific destination attributes (Filieri et al., Citation2018). The high review rating (4-star and 5-star ratings) refers to the extremely positive travelling experiences, and the low review rating (1-star and 2-star ratings) means the extremely negative complaints about the tourism products or services (Yang et al., Citation2017). In principle, high rating reviews can bring a positive attitude and high behaviour intentions, while low rating reviews will cause tourists to have a negative attitude and behaviour intentions towards the destination (Bigne et al., Citation2019; Zablocki et al., Citation2019).

The damage of the extremely low rating review to a destination image is huge and long-term, and it may deteriorate tourists’ cognitive and affective image, as well as visit intentions (conative image) (Becken et al., Citation2017; Zablocki et al., Citation2019). Some tourists strongly weigh the low rating reviews over high rating reviews, because they feel that the extremely negative low rating reviews are more diagnostic and thus more useful for knowing the destination (Sparks & Browning, Citation2011; Zhang et al., Citation2018), especially the low rating reviews with photos (Filieri, et al., Citation2018). But the low rating reviews had far less impact on travellers who were familiar with their destination than those who were unfamiliar with it (Bigne et al., Citation2019). Moreover, for the well-known brands, the extremely low rating reviews have a greater impact than on the lesser-known brands (Filieri et al., Citation2021). but for the lesser-known brands, the extremely high rating reviews have a greater impact than for the well-known brands (Vermeulen & Seegers, Citation2009). In the case of behaviour intention, East et al. (Citation2008) argued that the impact of high rating reviews is greater than that of low rating reviews. Furthermore, high rating reviews can create a stronger favourable affective image than a cognitive image (Zablocki et al., Citation2019). Some tourists are fond of adopting extremely positive rating reviews especially when the positive information is consistent with their pre-decisional preference (Liu & Park, Citation2015). Although earlier studies did not give consistent results on which category of rating is more powerful, the review rating attribute significantly affects tourists’ perception of the destination (Liu & Park, Citation2015). Review rating, as destination information that can be easily processed, is favoured by tourists (Sparks & Browning, Citation2011), which is considered to be the peripheral route of the formation of a destination image (Filieri, Citation2015; Sparks & Browning, Citation2011). Therefore, this study assumes:

Hypotheses 4, 5, 6: Review rating significantly influences the cognitive image (H4), the affective image (H5), and the conative image (H6) of a tourism destination.

Methodology

Santa Claus Village is world-famous as the official hometown of Santa Claus, which is one of the best places to visit in Finland. Santa Claus Village has a complete tourist infrastructure, including among other hotels, activities, restaurants, shopping stores, and transportation. Tourists from all over the world visit this place every year, and Chinese tourists were the fastest-growing segment of all tourists before the COVID-19 pandemic (Statistics Finland, Citation2019). Although the Nordic countries have great potential in the Chinese market (Statistics Finland, Citation2019), there are deficiencies in destination image research in the Nordic countries (Andersen et al., Citation2018). To promote Santa Claus Village in China, the Santa Claus Village established digital marketing strategies on China’s Sina Weibo in 2016. As of 2021, it has already gained 230,000 followers on Weibo. As a new and fast-growing Nordic tourist destination in the Chinese tourism market, when creating a competitive Santa Claus Village destination image, it still needs to consider two challenges. First, multiple international destinations claim to be associated with Santa Claus, leading tourists to question the authenticity of Santa Claus Village in Finland (Hall, Citation2014). Second, the natural environment is the value of the image of Santa Claus Village, and climate change makes the delivery of the destination image not only seek to influence and change tourists’ behaviour but also their expectations (Hall, Citation2014). It can be seen that how to deliver effective and accurate Santa Claus Village destination information to potential tourists is the key point to solving the above two challenges.

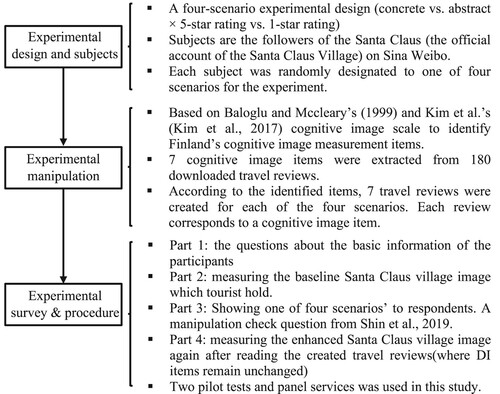

To study how concreteness review and review rating attributes affect the perception of a destination, this study used an experimental survey to achieve the research purposes. The flowchart below () shows the key information of the research process. The research process mainly consists of three parts, namely experimental design and subjects, development of stimuli and experimental manipulation, and experimental survey and procedure.

Experimental design and subjects

Experimentation is often used to detect the influence of one or more manipulated independent variables on other dependent variables (Ladhari & Michaud, Citation2015). The independent variables in this study are the online travel review attributes, including the concreteness attribute and review rating attribute. The dependent variable is the perceived destination image, including cognitive image, affective image, and conative image. Therefore, a four-scenario experimental design (concrete vs. abstract × 5-star rating vs. 1-star rating) was adopted to test the research hypotheses.

The experiment is usually carried out in a controlled environment, requiring participants to complete specific tasks following detailed instructions (Cao & Yang, Citation2016). In this experiment, participants are the followers of the Santa Claus (the official account of the Santa Claus Village) on Sina Weibo, a major Chinese social media platform. As the Santa Claus account often promotes destination information about Finland and Santa Claus Village on Weibo, all participants should likely have at least some kind of perception of Santa Claus Village. The baseline destination image is measured before the participant read the online travel reviews. Subsequently, the participant will be randomly designated to one of four scenarios according to the equal weights (0.25). After the participants have read all the travel reviews in their scenario, the destination image of the Santa Claus Village will be measured again. Based on the difference in the perceived destination image before and after the impact of travel reviews on destination image can be studied.

Development of stimuli and experimental manipulation

When studying the impact of environmental stimuli on tourists’ behaviours, the tourists’ cognition and emotions are usually used as mediating factors between situational stimuli and tourists’ responses (Li & Liu, Citation2020). The stimulus was developed by creating travel reviews in four different scenarios. To measure the destination image more comprehensively and accurately, this study developed a measurement cognitive destination attribute scale suitable for the Santa Claus Village based on Baloglu and McCleary’s (Citation1999) and Kim et al.’s (Citation2017) attribute scales.

The development steps are as follows: (i) Combined Baloglu and McCleary’s (Citation1999) 14-measurement items scale with Kim et al.’s (Citation2017) 7-measurement items scale resulted in a non-repeatable 16-measurement cognitive destination attributes scale. (ii) To avoid biases between travel review platforms (Guo et al., Citation2021), 180 travel reviews (the average length is 133 words) were collected from Ctrip, Mafengwo, Tuniu, Dianping, Qunar, Qyer, and Tripadvisor travel platforms. All downloaded travel reviews are the most recommended reviews on each platform for Santa Claus Village. (iii) Through qualitative content analysis of the content of the reviews, a cognitive destination attributes scale with seven attributes about Santa Claus Village was determined, including appealing local food, good value for money, suitable accommodations, quality of infrastructure (transportation), good entertainment, and good shopping opportunities.

After determining the measurements for cognitive destination attributes, seven travel reviews for each of the four scenarios were developed following guidelines from earlier literature (Shin et al., Citation2019). Each travel review corresponded to a cognitive destination image attribute. Thus, altogether 28 reviews were developed for this study. The number of words in each travel review was controlled at 60–70, and all of them were in Simplified Chinese. Simplified Chinese are standardized Chinese characters used in mainland China and is the official written language of the People’s Republic of China. Moreover, to create a realistic simulation experiment environment, we emulate Ctrip’s (the most influential tourism platform in China) travel review format. Appendix 1 shows one sample of appealing local food attributes in four scenarios.

Experimental survey and procedure

The questionnaire of the experimental survey contained four parts (Appendix 2). Part 1 includes the questions about the basic information of the participants. Part 2 is to measure the participants’ baseline cognitive, affective and conative images of Santa Claus Village. 7 measurement items of the baseline cognitive image were adopted from the author’s premise content analysis results. The items were measured by a seven-point Likert scale ranging from −3 (completely disagree), −2 (mostly disagree), −1 (slightly disagree), 0 (don’t know), to 1 (slightly agree), 2 (mostly agree), 3 (completely agree). When the measured item theoretically allows positive and negative responses (such as beliefs, and attitudes), bipolar response options could be applied to the measurement scale (Dolnicar, Citation2013). Since the participants may not know all of Santa Claus Village’s destination attributes, the option of “don’t know” was added. The “don’t know” option can prevent participants from guessing without knowing the answer, which is especially important in destination image measurement (Dolnicar, Citation2013). Both affective and conative images contain 3 measurement items, which were adopted from Kim et al.’s (Citation2017) and Agapito et al.’s (Citation2013) studies respectively. Affective image and conative image used the same seven-point Likert scale as cognitive image.

In Part 3, the participants will be randomly provided with travel reviews in one of four scenarios. Moreover, a manipulation check question was asked after the participants read all travel reviews, “overall. the online travel reviews are: (ranging from 1 = very abstract to 7 = very concrete)” (Shin et al., Citation2019, p. 585). Part 4 uses the same cognitive image, affective image, and conative image measurement items to evaluate the enhanced destination image of the Santa Claus Village after reading the reviews. Due to the participants having certainly obtained the Santa Claus Village’s destination information through the created travel reviews in Part 3, the “don’t know” option was removed in Part 4. All items were measured by a six-point Likert scale ranging from −3 (completely disagree) to 3 (completely agree).

The authors did two pilot tests, 32 people participated in the first test, and 24 people participated in the second test. In the pilot tests, the authors improved the readability of the created travel reviews, and also the manipulation check question in Part 3. Because most of the participants were not familiar with the concept of concreteness, given that concrete refers to the objective and abstract refers to subjective (Shin et al., Citation2019), the authors modified the manipulation check question to “overall. the online travel reviews are: (ranging from 1 = very subjective to 7 = very objective)” (Viglia & Dolnicar, Citation2020). This study used an online panel service (ePanel) to collect the questionnaire. The experimental survey was conducted from March 24, 2021, to April 29, 2021. A total of 1440 subjects participated in this experiment, and the number of valid questionnaires was 1305.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the subjects are listed in . Both groups A, B, C, and D have more than 300 valid questionnaires.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants.

Data analysis and results

The baseline destination image of santa claus village

The baseline destination image of Santa Claus Village is shown in . The Cronbach alpha of the baseline cognitive, affective, and conative images are 0.92, 0.89, and 0.90 separately. All values are higher than the cut-off point of 0.60 (Hair et al., Citation2010). Results also show all four groups of participants have a positive baseline destination image of Santa Claus village. Due to the observed data does not conform to the normal distribution, the non-parametric test is often applied (Hollander et al., Citation2013). The nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis H test for dependent four group samples shows that the significant value (p) of all measurement items is larger than 0.05. Thus, each group consists of similar social media users. Comparing the mean of the measurement items within each variable, almost all four groups of participants believed visiting Santa Claus Village is a good value for money (the highest Mean = 1.72 in Group D). They also felt Santa Claus Village is a pleasant destination (the highest Mean = 1.80 in Group B). Therefore, the participants have an intention to visit Santa Claus Village (the highest Mean = 1.65 in Group B).

Table 2. The baseline destination image of Santa Claus Village.

In addition, by analyzing the answers to the manipulation check question “Do you think the above travel reviews are more objective or more subjective in general?”, the participants could perceive the concrete or abstract characteristics of the created travel reviews as expected. The independent t-test for the concrete reviews (Group A, C) and abstract reviews (Group B, D) showed a significant difference (Mean_concrete = 4.91, Mean_abstract = 3.20, t = 22.217, p < .001). Thus, the manipulation checks were successful.

The enhanced destination image of santa claus village

After participants read the travel reviews, they were then asked to assess the destination image of Santa Claus Village again. The destination image analysis results are displayed in . The Cronbach alpha of the enhanced cognitive image, affective image, and conative image are 0.96, 0.94, and 0.94 separately. The result shows that after reading the reviews, the destination image in all four groups was still positive, but significantly different among them. The nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis H test shows that the difference between groups is statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Table 3. The destination image of Santa Claus Village after reading online travel reviews.

The changes in the destination image of santa claus village

According to the results of the baseline image and the enhanced image, the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for two related samples showed that, except for the measurement item of good value for money in group A (p = 0.384 > 0.05), all other items (p < 0.001 or p < 0.01) significantly changed in cognitive, affective and conative destination images after reading online travel reviews. Therefore, hypotheses 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 were supported in this study. The detailed results are presented in . Among all four groups, the changes in destination image in groups A and B were most positive. The changes in destination image in groups C and D were most negative.

Table 4. Changes in cognitive image affective image and overall image.

Additionally, comparing group A (concrete & 5-star rating) with group B (abstract & 5-star rating), when the review was extremely positive (5-star rating), the improvement of the cognitive image (0.31), the affective image (0.26), and the conative image (0.33) by the concrete review were greater than the improvement of the cognitive image (0.28), the affective image (0.18), and the conative image (0.23) by abstract review. However, comparing group C (concrete & 1-star rating) with group D (abstract & 1-star rating), when the review was extremely negative (1-star rating), the deterioration of the cognitive image (−0.83), affective image (−1.07), and conative image (−0.91) by the abstract review were higher than the deteriorating of the cognitive image (−0.74), affective image (−0.85), and conative image (−0.74) by concrete review.

Finally, comparing group A (concrete & 5-star rating) with group C (concrete & 1-star rating), when the review was concrete, the absolute change value of the cognitive image (−0.74), affective image (−0.85), and conative image (−0.74) by extremely negative travel review (1-star rating) were higher than the absolute change value of the cognitive image (0.31), the affective image (0.26), and the conative image (0.33) by extremely positive review (5-star rating). This situation also occurred when the travel review is abstract. Compared group B (abstract & 5-star rating) with group D (abstract & 1-star rating), the absolute change value of the cognitive image (−0.83), affective image (−1.07), and conative image (−0.91) by extremely negative travel review (1-star rating) was higher than the absolute change value of the cognitive image (0.28), the affective image (0.18), and the conative image (0.23) by extremely positive travel review (5-star rating).

Discussions

Destination image is formed by the fusion of information from different channels, and the destination information has a significant impact on tourists’ perception, satisfaction, and behaviour intention (i.e. cognitive image, affective image, and conative image) of tourists (Wong et al., Citation2016; Zhang et al., Citation2018). Online travel reviews, as an organic destination information source that tourists value, play a vital role in shaping their perception of a destination image (Abubakar et al., Citation2017). This study explored how the destination image was changed by the destination information presented by four different kinds (i.e. concrete vs. abstract × 5-star rating vs. 1-star rating) of travel reviews.

Elaboration likelihood model in destination image formation

First, this study confirmed that the destination information presented in online travel reviews affects the formation of the destination image from both the central route (review concreteness) and the peripheral route (review rating). According to the theory of the elaboration likelihood model, the central route and the peripheral route could work together in practice to influence the adoption of destination information and destination perception (Chung et al., Citation2015; Tseng & Wang, Citation2016). Especially as travel reviews have many different attributes (Ukpabi & Karjaluoto, Citation2018), each attribute is important for tourists in evaluating the usefulness and helpfulness of destination information from the central and the peripheral routes (Filieri, Citation2015; Filieri et al., Citation2018; Filieri & McLeay, Citation2014; Zablocki et al., Citation2019). For instance, Shin et al. (Citation2019) believe the concreteness attribute of travel reviews is the key feature in describing tourists’ travelling experience and evaluation in detail. Thus, it is quite important to the formation of the destination image from the central route. However, when tourists obtain destination information through travel reviews, it is impossible to sort out all the review content. The review rating can intuitively and simply use a 1–5-stars rating scale to show tourists’ overall evaluation of the destination or its attributes, so it plays a vital role in the formation of the destination image from the peripheral route (Filieri, Citation2015). This study is the first to prove from the theory of the elaboration likelihood model that tourists adopt travel reviews through a dual process and form a destination image. In this way, it provides a theoretical basis for more empirical destination image studies in the future.

The role of review rating and review concreteness in destination image change

Although the review concreteness and the review rating attributes are both important to the destination image formation, the ways they change tourists’ perceptions differ. Understanding this effect is a major contribution to this research. The results () showed that the effects of high rating and low rating reviews follow a basic principle of high rating reviews improving destination image and low rating reviews deteriorating it (Zablocki et al., Citation2019). The low rating reviews harm cognitive image, affective image, and conative image more than high rating reviews improve them. The reason might be tourists often give more weight to negative messages and amplify the impact of low rating travel reviews (Sparks & Browning, Citation2011). In addition, these results not only supplement East et al.’s (Citation2008) study but also casts doubt on their findings that the deterioration of negative reviews was lower than the improvement of positive reviews on behaviour intention (conative image). Furthermore, Zablocki et al. (Citation2019) found that the high rating reviews can create a stronger favourable affective image than the cognitive image. This study has the opposite result as low rating negative reviews affect affective image more than the cognitive image and high rating reviews affect cognitive image more than the affective image.

Second, the concrete travel review and abstract travel review have different effects on destination image under the high rating positive or the low rating negative scenarios. So far the concrete travel review has been considered more useful than the abstract travel review (Li et al., Citation2013). The results of this study show that this argument should be treated carefully in different scenarios. Under the high rating scenario, the concrete travel review improves the cognitive image, the affective image, and the conative image more than the abstract travel review. In contrast, under the low rating scenario, the deterioration of abstract travel review on the cognitive image, the affective image, and the conative image is greater than in concrete travel review. Additionally, Shin et al. (Citation2019) argued that the concrete travel review has more influence on the cognitive image, and the abstract travel review has more influence on the affective image. This study further supplements earlier findings that tourists pay more attention to the perception of the cognitive image when the travel reviews are concrete with a high rating. Tourists focus on the perception of the affective image when the travel reviews are abstract with a low rating.

Managerial implementation

This study provides an in-depth understanding of how different types of information content create opportunities for destination marketers to improve their destinations. For a long time, the promotion of destination information has been regarded as an important factor to form a favourable destination image for potential tourists (Munar, Citation2012; Nowacki & Niezgoda, Citation2020). In the process of information acquisition and processing, destination marketers have many good opportunities to influence tourists’ perception of the destination image and their decision-making behaviour through the central and the peripheral routes (Filieri & McLeay, Citation2014; Zhang et al., Citation2018). Destination marketers can use a wide range of social media to promote destination information thus achieving the best effect of content marketing, such as establishing official channels on different platforms and encouraging tourists to share their travel experiences. However, no matter which method is used to promote the destination, the preparation of destination information is a prerequisite step, and how to create accurate destination information to improve the destination image requires careful consideration.

As far as information content is concerned, destination perception formed through the central route will make tourists have a persistent attitude towards the destination (Tang & Jang, Citation2014). To enhance tourist destination image and their travel intentions, this study suggests destination marketers use more concrete positive content than abstract positive content. In addition to improving tourist destination image, low rating travel reviews have a significant impact on potential tourists unfamiliar with the destination (Bigne et al., Citation2019), thus marketers should also actively repair the damaged image. As an important organic image agent, travel reviews have become the first choice for Chinese outbound tourists to obtain Western destination information (iResearch, Citation2019). Since many Chinese travel review platforms provide the reply function to tourists’ reviews, marketers should seize this opportunity to repair the damaged destination image. As the research findings in this study demonstrate, marketers should be more sensitive to the low rating and abstract travel review and take further improvement measures based on the situation of the destination itself.

Tourists are influenced by both central and peripheral routes when processing destination information (Filieri, et al., Citation2018). Although the effect of the peripheral route on destination perception is temporary, destination marketers can constantly remind their perception of the destination through the peripheral route (Tang & Jang, Citation2014). For western destination marketers, when designing official tourism websites and promoting a destination, they need to further consider the peripheral cues of local mainstream tourism websites. For example, Ctrip, the largest travel platform in China, uses emoticons in the visual design of its ratings compared with TripAdvisor, the international mainstream tourism platform.

Conclusion and limitations

Although the influence of online travel reviews on destination image has been proven (de la Hoz-Correa & Muñoz-Leiva, Citation2019; Reza Jalilvand et al., Citation2012), how specific travel review attributes affect the cognitive, affective, or conative image has not been extensively studied. This study adopted the elaboration likelihood model to explore the influencing mechanism of travel review attributes (i.e. concrete vs. abstract × 5-star rating vs. 1-star rating) on destination image though through a survey experiment.

This study confirmed that the formation of the tourist destination image is influenced by both central (review concreteness) and peripheral routes (review rating). Different travel review attributes have different effects on the change of cognitive image, affective image, and conative image. Specifically, the low rating negative reviews do greater damage to the cognitive, affective, and conative image than the improvement of high rating positive reviews in this case. The low rating negative reviews are the most harmful to the affective image, and the high rating positive reviews are the best improvement to the cognitive image. Second, under the high rating positive scenario, the concrete travel review improves the cognitive image, the affective image, and the conative image more than the abstract travel review. In contrast, under the low rating negative scenario, the abstract travel review deteriorates these three image components more than the concrete travel review. These results enhance destination marketers’ understanding of the importance of travel reviews on destination perception and provide strategic thinking on how to improve a destination image. All these findings mean that not all reviews have the same value for a destination. Some reviews are more valuable than others in their possibilities to change destination image. This study provides an understanding of what makes online travel reviews valuable for destination image development and why.

Although the results have achieved the study purpose, there are some limitations and provide some ideas for future research. First, cognitive image, affective image, and conative image are three interrelated components of destination image (Baloglu & McCleary, Citation1999). Although the findings revealed that the travel review changed tourists’ cognitive, affective, and conative images, it does not explain how much these changes were caused by the interrelationship of the three image components. Second, in addition to the review concreteness attributes and review rating attributes, online travel review also has many other attributes, including review timeliness, review consistency, and source homophily (Filieri et al., Citation2018; Ukpabi & Karjaluoto, Citation2018). Especially the visual cues (such as user-generated pictures), as one of the key factors which affect the tourists’ decisions (Filieri et al., Citation2018; Filieri et al., Citation2021), should be emphatically studied in the future research. Third, this study did not distinguish between participants who have been to the Santa Claus Village and those who have not. For tourists who have not visited the destination, destination information significantly evolves their cognitive image, but it is difficult for tourists who have been to the place (Li et al., Citation2009). In the future, it is necessary to study whether travel experience has a moderating effect on the changes in a destination image.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abubakar, A. M., Ilkan, M., Meshall Al-Tal, R., & Eluwole, K. K. (2017). eWOM, revisit intention, destination trust and gender. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 31, 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.12.005

- Agapito, D., Oom do Valle, P., & da Costa Mendes, J. (2013). The cognitive-affective-conative model of destination image: A confirmatory analysis. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(5), 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.803393

- Andersen, O., Øian, H., Aas, Ø, & Tangeland, T. (2018). Affective and cognitive dimensions of ski destination images. The case of Norway and the lillehammer region. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(2), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2017.1318715

- Baloglu, S., & McCleary, K. W. (1999). U.S. International pleasure travelers’ images of four Mediterranean destinations: A comparison of visitors and nonvisitors. Journal of Travel Research, 38(2), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759903800207

- Becken, S., Jin, X., Zhang, C., & Gao, J. (2017). Urban air pollution in China: Destination image and risk perceptions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 130–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1177067

- Beerli, A., & Martín, J. D. (2004a). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 657–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.01.010

- Beerli, A., & Martı́n, J. D. (2004b). Tourists’ characteristics and the perceived image of tourist destinations: A quantitative analysis—a case study of lanzarote, Spain. Tourism Management, 25(5), 623–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.06.004

- Bigne, E., Ruiz, C., & Curras-Perez, R. (2019). Destination appeal through digitalized comments. Journal of Business Research, 101(June 2018), 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.020

- Cao, K., & Yang, Z. (2016). A study of e-commerce adoption by tourism websites in China. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(3), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.01.005

- Chung, N., Han, H., & Koo, C. (2015). Adoption of travel information in user-generated content on social media: The moderating effect of social presence. Behaviour & Information Technology, 34(9), 902–919. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2015.1039060

- de la Hoz-Correa, A., & Muñoz-Leiva, F. (2019). The role of information sources and image on the intention to visit a medical tourism destination: A cross-cultural analysis. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(2), 204–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1507865

- Dolnicar, S. (2013). Asking good survey questions. Journal of Travel Research, 52(5), 551–574. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513479842

- East, R., Hammond, K., & Lomax, W. (2008). Measuring the impact of positive and negative word of mouth on brand purchase probability. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 25(3), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2008.04.001

- Filieri, R. (2015). What makes online reviews helpful? A diagnosticity-adoption framework to explain informational and normative influences in e-WOM. Journal of Business Research, 68(6), 1261–1270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.11.006

- Filieri, R., Hofacker, C. F., & Alguezaui, S. (2018). What makes information in online consumer reviews diagnostic over time? The role of review relevancy, factuality, currency, source credibility and ranking score. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.039

- Filieri, R., Lin, Z., Pino, G., Alguezaui, S., & Inversini, A. (2021a). The role of visual cues in eWOM on consumers’ behavioral intention and decisions. Journal of Business Research, 135(June), 663–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.055

- Filieri, R., & McLeay, F. (2014). E-WOM and accommodation. Journal of Travel Research, 53(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513481274

- Filieri, R., McLeay, F., Tsui, B., & Lin, Z. (2018a). Consumer perceptions of information helpfulness and determinants of purchase intention in online consumer reviews of services. Information & Management, 55(8), 956–970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2018.04.010

- Filieri, R., Raguseo, E., & Vitari, C. (2018b). When are extreme ratings more helpful? Empirical evidence on the moderating effects of review characteristics and product type. Computers in Human Behavior, 88(April), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.042

- Gartner, W. C. (1994). Image formation process. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 2(2-3), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v02n02_12

- González-Rodríguez, M. R., Martínez-Torres, R., & Toral, S. (2016). Post-visit and pre-visit tourist destination image through eWOM sentiment analysis and perceived helpfulness. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(11), 2609–2627. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2015-0057

- Guo, X., Pesonen, J., & Komppula, R. (2021). Comparing online travel review platforms as destination image information agents. Information Technology & Tourism, 23(2), 159–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-021-00201-w

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall. https://books.google.fi/books?id=JlRaAAAAYAAJ.

- Hall, C. M. (2014). Will climate change kill santa claus? Climate change and high-latitude christmas place branding. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.886101

- Hollander, M., Wolfe, D., & Chicken, E. (2013). Nonparametric statistical methods. https://www.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Y5s3AgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP10&dq=nonparametric+statistical+methods&ots=a_i-j45kxQ&sig=5Xk7vTYCylCgDhXWhOXwSDnfFfM.

- iResearch. (2019). China online outbound tourism industry research report. http://www.iresearchchina.com/content/details8_57826.html.

- Kim, S. E., Lee, K. Y., Shin, S. I., & Yang, S. B. (2017). Effects of tourism information quality in social media on destination image formation: The case of sina weibo. Information & Management, 54(6), 687–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2017.02.009

- Ladhari, R., & Michaud, M. (2015). eWOM effects on hotel booking intentions, attitudes, trust, and website perceptions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 46, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.01.010

- Li, C. H., & Liu, C. C. (2020). The effects of empathy and persuasion of storytelling via tourism micro-movies on travel willingness. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(4), 382–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2020.1712443

- Li, M., Huang, L., Tan, C. H., & Wei, K. K. (2013). Helpfulness of online product reviews as seen by consumers: Source and content features. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 17(4), 101–136. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEC1086-4415170404

- Li, X., Pan, B., Zhang, L., & Smith, W. W. (2009). The effect of online information search on image development. Journal of Travel Research, 48(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287508328659

- Liu, Z., & Park, S. (2015). What makes a useful online review? Implication for travel product websites. Tourism Management, 47, 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.020

- Munar, A. M. (2012). Social media strategies and destination management. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 12(2), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2012.679047

- Nowacki, M., & Niezgoda, A. (2020). Identifying unique features of the image of selected cities based on reviews by TripAdvisor portal users. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(5), 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1833362

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. In: Communication and Persuasion. Springer Series in Social Psychology. (pp. 1–24). New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4964-1_1

- Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Goldman, R. (1981). Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41(5), 847–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.41.5.847

- Reza Jalilvand, M., Samiei, N., Dini, B., & Yaghoubi Manzari, P. (2012). Examining the structural relationships of electronic word of mouth, destination image, tourist attitude toward destination and travel intention: An integrated approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1–2), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.001

- Rodríguez-Molina, M. A., Frías-Jamilena, D. M., & Castañeda-García, J. A. (2015). The contribution of website design to the generation of tourist destination image: The moderating effect of involvement. Tourism Management, 47, 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.001

- Shani, A., Chen, P. J., Wang, Y., & Hua, N. (2010). Testing the impact of a promotional video on destination image change: Application of China as a tourism destination. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(2), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.738

- Shin, S., Chung, N., Xiang, Z., & Koo, C. (2019). Assessing the impact of textual content concreteness on helpfulness in online travel reviews. Journal of Travel Research, 58(4), 579–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518768456

- Shu, M. (Lavender), & Scott, N. (2014). Influence of social media on Chinese students’ choice of an overseas study destination: An information adoption model perspective. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31(2), 286–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.873318

- Sparks, B. A., & Browning, V. (2011). The impact of online reviews on hotel booking intentions and perception of trust. Tourism Management, 32(6), 1310–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.12.011

- Statistics Finland. (2019). Number of arrivals from China to Finland. http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/.

- Tan, W.-K., & Wu, C.-E. (2016). An investigation of the relationships among destination familiarity, destination image and future visit intention. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(3), 214–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.008

- Tang, L. R., & Jang, S. S. (2014). Information value and destination image: Investigating the moderating role of processing fluency. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 23(7), 790–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2014.883585

- Tseng, S. Y., & Wang, C. N. (2016). Perceived risk influence on dual-route information adoption processes on travel websites. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 2289–2296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.044

- Ukpabi, D. C., & Karjaluoto, H. (2018). What drives travelers’ adoption of user-generated content? A literature review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 28(September 2017), 251–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.03.006

- Vermeulen, I. E., & Seegers, D. (2009). Tried and tested: The impact of online hotel reviews on consumer consideration. Tourism Management, 30(1), 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.04.008

- Viglia, G., & Dolnicar, S. (2020). A review of experiments in tourism and hospitality. Annals of Tourism Research, 80(August 2019), 102858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102858

- Wang, P. (2015). Exploring the influence of electronic word-of-mouth on tourists’ visit intention. Journal of Systems and Information Technology, 17(4), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSIT-04-2015-0027

- Wong, J. Y., Lee, S. J., & Lee, W. H. (2016). ‘Does it really affect Me?’ tourism destination narratives, destination image, and the intention to visit: Examining the moderating effect of narrative transportation. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(5), 458–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2063

- Yang, S. B., Shin, S. H., Joun, Y., & Koo, C. (2017). Exploring the comparative importance of online hotel reviews’ heuristic attributes in review helpfulness: A conjoint analysis approach. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(7), 963–985. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1251872

- Zablocki, A., Schlegelmilch, B., & Houston, M. J. (2019). How valence, volume and variance of online reviews influence brand attitudes. AMS Review, 9(1–2), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-018-0123-1

- Zhang, M., Zhang, G., Gursoy, D., & Fu, X. (2018). Message framing and regulatory focus effects on destination image jformation. Tourism Management, 69(April), 397–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.06.025

Appendices

Appendix 1. Examples of created online travel reviews on local cuisine attribute