ABSTRACT

This multiple case study investigates internal crisis communication in Finnish and Norwegian hotels and restaurants during the COVID-19 pandemic, contributing a Nordic leadership perspective to the research area. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, a qualitative research design was chosen, and 16 semi-structured interviews were conducted with hospitality leaders, middle managers, and employees. The multilevel analysis revealed that existing internal communication practices were challenged due to the urgency and uncertainty of the crisis. The findings show that managerial transparency and presence facilitated sensemaking processes and contributed to trust in the managers. Yet, limited autonomy among middle managers and lack of employee consultation when communicating about decision-making indicated a conflict between internal crisis communication and aspects of Nordic leadership such as cooperation, consensus-seeking, and delegation of responsibility. However, the findings suggest that the openness and transparency of Nordic leadership prevailed in the crisis and contributed to managerial learning and solution-finding through crisis communication and management. Furthermore, leaders should find a balance between control and participation when communicating about internal decision-making during a crisis. We conclude that transparency and participative communication are essential when striving for effective internal crisis communication, facilitating employees’ sensemaking, and building trust relationships during a crisis.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic is a transboundary crisis that escalated rapidly and has had a considerable impact on organizations’ internal processes (Boin, Citation2019). As a response to the crisis, organizations around the world emphasized communicating safety and health precautions from health authorities. The services sector has been greatly affected by the pandemic, and tourism services have suffered due to mobility restrictions and social distancing measures (World Trade Organization, Citation2020, p. 1). The tourism sector in the Nordic countries was also hard struck by the COVID-19 pandemic. In Finland, the tourism sector accounts for about 2.7% of the country’s GDP. In 2019, 154,000 people were employed in industries linked to tourism, accounting for about 5.5% of the total workforce (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, Citationn.d.). In the spring of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a collapse on the demand for tourism services (Marski, Citation2021) and the amount of money spent by foreign tourists in Finland in 2020 was reduced by 67%. Domestic tourism demand fell 20% during the same year (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, Citation2021). As a result, the worst performers were the accommodation and food services where the production decreased 55% in the second quarter of 2020 compared to the same quarter in 2019 (Statistics Finland, Citation2020). Further, the number of people laid off (Marski, Citation2021) and the amount of financial support for tourism businesses have multiplied (Nurmi & Veistämö, Citation2020) as a result of the crisis. In Norway, the tourism industries accounted for about 4.2% of Norway’s GDP in 2019 (Statistics Norway, Citation2021) and employed around 171,000 people (López, Citation2021), accounting for 7.1% of the total employment (Statistics Norway, Citation2021). The number of jobs in the lodging and food service industry decreased by 15.5 percent from October 2019 to October 2020, showing a major job loss in the industry (Horgen, Citation2020). Compared to 2019, accommodation businesses lost 29% and food service companies 17–19% of their turnover in 2020 (Jakobsen et al., Citation2021). Tourism was the industry that received the most governmental compensation in Norway during the spring of 2020 (Rybalka, Citation2020) due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The largest amounts of compensations in 2020 were received by accommodation businesses (Jakobsen et al., Citation2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic manifested the importance of effective crisis management and communication. Prior crisis communication studies have predominantly focused on external dimensions such as crisis response strategies (Johansen et al., Citation2012) or the impact of communication on external stakeholders (Mazzei & Ravazzani, Citation2015), whereas fewer studies have addressed internal crisis communication (Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011; Heide & Simonsson, Citation2014, Citation2015; Johansen et al., Citation2012). Relying on frequent human contact, the hospitality industry provides an interesting perspective to internal crisis communication research, as hospitality organizations needed to adjust their operations drastically and effectively communicate infection control measures.

In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, internal crisis communication is an understudied area of research in the hospitality industry. Ritchie et al. (Citation2011) pointed out that although the accommodation industry is extremely vulnerable to crises, there is a lack of research exploring accommodation crisis management. In their study of proactive crisis planning, Ritchie et al. (Citation2011) emphasized the importance of crisis planning and crisis preparedness for the accommodation industry but did not specifically focus on internal crisis communication as a central aspect of crisis planning and preparedness. A systematic review of research on the hospitality industry in light of the COVID-19 pandemic listed central topics such as revenue impact, market demand, safety and health, workers’ issues, prospects of recovery of the industry, and customers’ preferences, but did not include crisis communication (Davahli et al., Citation2020). However, Guzzo et al. (Citation2021) addressed internal crisis communication in studying hospitality employees’ affective responses to managers’ communication in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some pre-pandemic studies have addressed crisis management challenges for the hospitality industry in view of natural disasters (Tsai & Chen, Citation2011) or festival safety (Mykletun, Citation2011). From the perspective of the Nordic tourism and hospitality industry, studies have addressed community reactions and responses to the pandemic in light of future sustainable destination development (Bertella, Citation2022), and climate change crises (Hall & Saarinen, Citation2021). However, none of these studies specifically address crisis communication. One Nordic study addressed tourism companies’ sustainability communication (Bogren & Sörensson, Citation2021), but there is a conspicuous lack of studies on crisis communication in the Nordic hospitality industry.

Leadership is challenging in times of crisis when people’s safety or the success of an activity is endangered (Yukl, Citation2013), and new demands on leadership arise (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2021). A recent study by Heide and Simonsson (Citation2021) implied that effective crisis leadership seems to have more democratic and collaborative characteristics than previously assumed. Values of openness, transparency, trust, and integrity together with a flat organizational structure, cooperation (Andreasson & Jamholt, Citation2018; Andreasson & Lundqvist, Citation2018), low power-distance (Lindell & Arvonen, Citation1996; Warner-Søderholm, Citation2012b), and consensus (Warner-Søderholm, Citation2012b) are highlighted as central characteristics of Nordic leadership. Previous studies have investigated internal crisis communication in organizations in the Nordic region (e.g. Heide & Simonsson, Citation2014, Citation2015; Johansen et al., Citation2012; Ravazzani, Citation2016; Strandberg & Vigsø, Citation2016), yet a missing link remains between internal crisis communication and Nordic leadership. This study thus addresses the following question: Does the openness and transparency of Nordic leadership prevail during times of crisis?

Besides responding to calls from previous studies for more research on internal crisis communication (Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2011; Heide & Simonsson, Citation2014, Citation2015; Johansen et al., Citation2012; Taylor, Citation2010), this paper introduces original perspectives on Nordic leadership. More specifically, this multiple case study investigates hospitality leaders’, middle managers’, and employees’ perceptions of internal crisis communication in Finland and Norway. Against this backdrop, the paper addresses the following research questions:

How have Nordic hospitality leaders communicated COVID-19 related issues during the pandemic, and how have their employees perceived and made sense of this communication?

How are aspects of Nordic leadership reflected in the internal crisis communication during the COVID-19 pandemic?

In addition to filling a knowledge gap in the research area and making theoretical contributions in the context of Nordic leadership, studying internal crisis communication during the COVID-19 pandemic helps us learn from this crisis and be better prepared for future pandemics (Jong, Citation2021). However, the term “Nordic” is slightly problematic as some studies reviewed in this paper refer to the Nordic region (including all or some of the Nordic countries), while others focus on the Scandinavian countries. Similar issues arise with the term “leadership” since some of the prior studies in the research area refer to leadership, some to management, and some more specifically to leadership or management styles. In fact, these terms are sometimes used interchangeably in prior research, without a clear definition of the constructs. This paper collects these terms under a broader concept of Nordic leadership. While acknowledging differences in leadership between the Nordic countries, the paper does not go into much detail regarding the national differences but rather looks at internal crisis communication in the light of the common characteristics of Nordic leadership in the Nordic countries.

Following this introduction, a review of relevant literature is introduced. The methodology section describes the methods used for data collection and analysis. The presentation of the findings is followed by a discussion of the main themes uncovered from the qualitative analysis of the interviews and finally, conclusions and suggestions for future research are presented.

Literature review

Internal crisis communication

Coombs defined crisis as “the perception of an unpredictable event that threatens important expectancies of stakeholders and can seriously impact an organization’s performance and generate negative outcomes” (Coombs, Citation2012, p. 2). A crisis threatens the most central role of an organization (Weick, Citation1988) and can lead to negative consequences for safety, health, and wellbeing (Millar & Heath, Citation2004), as in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic. A crisis can be described as a process that develops through at least three phases: precrisis, crisis, and postcrisis (Coombs, Citation2012). Crisis management involves efforts to plan in advance for potential crises (Fink, Citation1986), avert crises when possible, manage situations that occur, as well as organizational recovery and readjustment (Pearson & Clair, Citation1998). This study focuses on the crisis stage of the pandemic, and the response of the hotels and restaurants in terms of their internal crisis communication.

Internal crisis communication between managers and employees takes place in organizations before, during, and after a crisis (Johansen et al., Citation2012) where employees’ sensemaking and interpretation of management’s crisis communication becomes a central part of internal crisis communication (Strandberg & Vigsø, Citation2016). Frandsen and Johansen (Citation2011) discussed employees’ role as senders and how – by sharing their attitudes, feelings, and opinions – employees can become positive or negative ambassadors in an organization. For internal crisis communication to be effective, management needs to include employee voices and understand their views and behaviours during a crisis (Kim & Lim, Citation2020) and realize that employees are a vital part of the crisis communication and act as strategic communicators (Simonsson & Heide, Citation2018). In organizations where open communication endures and management is willing to listen, employees are also more willing to share potentially useful information or ideas (Morrison, Citation2011). Failing to listen and communicate with employees who are directly affected by the crisis can create a misalignment between what managers intend to communicate and how employees actually perceive the internal crisis communication (Mazzei & Ravazzani, Citation2011; Strandberg & Vigsø, Citation2016). Therefore, organizations should ensure employee participation in transparent and two-way symmetrical communication in crisis situations (Kim, Citation2018). Moreover, trust is an important variable of effective communication in times of crisis (Longstaff & Yang, Citation2008; Palttala et al., Citation2012). Successful organizations are honest and communicate openly and accurately as soon as the crisis occurs. Withholding information only aggravates a crisis as it is inevitable that the whole story will sooner or later be known (Sellnow & Sarabakhsh, Citation1999). Investigating internal crisis communication strategies and trust relationships, Mazzei and Ravazzani (Citation2015) found that inconsistency between statements made and actions taken and a lack of transparency were among the biggest errors in internal crisis communication according to communicators. A more recent study by Ecklebe and Löffler (Citation2021) investigated employees’ perceptions of the quality of communication and identified participatory communication as one of the antecedents of high-quality internal crisis communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Shared decision-making during times of uncertainty can give employees a sense of control and make them feel invested in the decisions that affect them the most (Erickson, Citation2021).

In the growing research area of internal crisis communication, scholars have also investigated managers’ points of view on internal crisis communication and employee multiculturalism (Ravazzani, Citation2016), the different roles and practices of communication professionals (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2014), and the complexity of internal crisis communication by identifying the paradoxical tensions of a large, multi-professional organization (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2015). However, research on internal crisis communication that includes a Nordic leadership perspective seems to be scarce.

Nordic leadership

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged leaders with new demands (Heide & Simonsson, Citation2021) and different role expectations (Yukl, Citation2013) and impacted their process of influencing a group of individuals to achieve a common goal (Northouse, Citation2018). While more research is needed on leadership in crisis, descriptive research has shown that effective leaders take initiative in defining a problem, identifying solutions, directing the crisis response, and keeping people informed about what is happening. Yet, perceptions of effective leadership vary between cultures as cultural beliefs are likely to affect leader behaviour (Yukl, Citation2013). In a pre-pandemic study, Hallin and Marnburg (Citation2007) found that when dealing with uncertainty in times of change, Danish hotel managers preferred to use traditional strategic approaches such as planning, procedures, and routines, instead of promoting creative and innovative solutions to develop their businesses and build competitive advantages. Another study in a Scandinavian context found that effective hospitality managers are characterised by being able to regulate their emotions in addition to being able to make good decisions in stressful situations (Haver et al., Citation2014). These findings are relevant for how hospitality managers have handled the challenging situation during the COVID-19 pandemic (Gjerald et al., Citation2021).

A report published for the Nordic Council of Ministers’ Secretariat (Andreasson & Lundqvist, Citation2018) summarized existing research on Nordic leadership, characterizing it through values such as openness, transparency, trust, integrity, and high consensus-seeking. Cooperation is valued beyond competition and there is a strong individualistic perspective in Nordic leadership (Andreasson & Lundqvist, Citation2018). In contrary to directive leadership where leaders schedule and coordinate the work and give specific guidance, rules, and procedures (House, Citation1996), Nordic leadership is in line with participative leadership where subordinates are included in and encouraged to take part in the transparent decision-making processes (House, Citation1996) to make sure decisions are not a result of a single person’s will or judgement (Biddle, Citation2005). Nordic leadership style is more people-oriented than task-oriented (Pöllänen, Citation2006); instead of emphasizing one’s authority, the leader acts more like a coach who motivates employees instead of telling them what to do (Andreasson & Lundqvist, Citation2018). Nordic communication tends to be direct (Lindell & Arvonen, Citation1996; Warner-Søderholm, Citation2012b) and assertive while aggressive and competitive communication is not prevalent (Warner-Søderholm & Cooper, Citation2016).

Some of the literature in the research area has focused more specifically on Scandinavian management and leadership (e.g. Grenness, Citation2003, Citation2011; Jönsson, Citation1996; Poulsen, Citation1988; Schramm-Nielsen et al., Citation2004; Warner-Søderholm, Citation2012b). For instance, Grenness (Citation2003) studied Scandinavian managers’ perceptions of themselves as managers and found that many of the interviewees’ statements were value-loaded, and that the managers were very aware of operating within a specific cultural context. Furthermore, comparing Scandinavian managers’ cultural values, Warner-Søderholm (Citation2012b) found that Norway, Sweden, and Denmark showed egalitarianism, low power distance, and consensus in decision-making. Similarly, a study of Nordic management style in a European context demonstrated delegation of responsibility, friendship toward subordinates, and a short distance between a manager and subordinates (Lindell & Arvonen, Citation1996).

In a study of nature guides in Norway, Løvoll and Einang (Citation2021) investigated transparent guiding as a practical leadership style, identifying trustworthy relations, authentic leadership, and humbleness as important skills for the success of performing transparent guiding. Authentic leaders establish open, genuine, and trusting relationships (Avolio, Citation2004), touching on values that align with the values in Nordic leadership (Andreasson & Lundqvist, Citation2018). Furthermore, education is viewed as important in Nordic leadership and it offers flexibility to employees who, due to higher education, can take increased responsibility in organizations. Flexibility is based on a high degree of autonomy and gives individual employees responsibility as well as significant power and influence over their own work (Andreasson & Lundqvist, Citation2018). Transformational leaders consider individuals and encourage them to intellectual stimulation and creativity (Bass & Steidlmeier, Citation1999). Studying transformational leadership in a Norwegian context, Hetland and Sandal (Citation2003) found that according to Norwegian employees, warmth and sensitivity in considering the needs of others, was an important attribute for being perceived as a transformational leader.

Though Nordic leadership is not characterized as very formal, common assumptions and unspoken rules exist in terms of “how things are done here” (Andreasson & Lundqvist, Citation2018). Unspoken rules might be problematic for foreign employees, who, without a thorough understanding of the Nordic culture and values, might not grasp the subtle but relevant assumptions of the code of conduct. Further, a lack of a clear hierarchies can be challenging when doing business in other countries (Smith et al., Citation2003) where a clear division of hierarchy is expected and called-for. Nordic leadership style has been criticized for being too internally focused with the primary aim on fair distribution, which can potentially lead to passiveness or escape from responsibility (Reve, 1994, as cited in Andreasson & Lundqvist, Citation2018). A less consensus-oriented corporate culture may lead to more efficiency and faster decision-making, which can be beneficial for instance in crisis situations where fast decision-making and implementation might be crucial for the organization to safeguard the safety, health and well-being of the stakeholders.

Scholars have also described Nordic leaders as thoughtful but not selfish (Moos, Citation2013) and found them to be caring toward their employees (Lindell & Arvonen, Citation1996). Accordingly, Nordic leadership has also similar characteristics with servant leadership, which emphasizes egalitarianism and moral integrity, and where leaders develop and empower people with humility and empathy (Mittal & Dorfman, Citation2012). However, it is not appropriate to assume that Nordic leadership is homogeneous in the Nordic region where differences are bound to exist. Investigating Nordic management styles, Smith et al. (Citation2003) reported Danes to have a higher reliance on subordinates, Norwegians on co-workers, and Swedes on formal rules and procedures. Finland and Iceland contrasted with the Scandinavian countries with a relatively high reliance on informal and unwritten rules, and one’s own experience (Smith et al., Citation2003). Other authors, too, have addressed contrasts in leadership in the Nordic countries (e.g. Lämsä, Citation2010; Larsen & Bruun de Neergaard, Citation2007; Lindell & Arvonen, Citation1996; Warner-Søderholm, Citation2012a, Citation2012b).

Communication is central in leadership and management (Erickson, Citation2021), however previous literature suggests that a hierarchical organizational structure adapts poorly in uncertain situations (Palttala et al., Citation2012). One could then assume that the short distance between manager and subordinates, openness, trust, and transparency of Nordic leadership style can provide a good foundation for effective internal crisis communication. This line of thought is supported by previous authors who have noted the importance of open and accurate communication (Sellnow & Sarabakhsh, Citation1999), trust (Longstaff & Yang, Citation2008; Palttala et al., Citation2012), authenticity (Erickson, Citation2021), transparency (Erickson, Citation2021; Palttala et al., Citation2012), and open information sharing (Palttala et al., Citation2012) in crisis situations.

Sensemaking

In times of crises, which are characterized by the disruption of everyday routines and cues, sensemaking processes are central to understanding and creating meaning out of ambiguous and confusing situations (Maitlis & Sonensheim, Citation2010). Sensemaking is a social process that edits and simplifies our experience with constant change. In ambiguous situations, people often keep acting while asking questions like “what is the story here” or “now what” (Weick & Sutcliffe, Citation2015).

Sensemaking is about sizing up a situation while you simultaneously act and partially determine the nature of what you discover. […] It is usually an attempt to grasp a developing situation in which the observer affects the trajectory of that development. (Weick & Sutcliffe, Citation2015, p. 32)

The sensemaking process of different groups may vary and what is plausible for one group might be implausible for another (Weick et al., Citation2005), resulting in different views on internal crisis communication between the management and employees (Mazzei & Ravazzani, Citation2011; Strandberg & Vigsø, Citation2016). Prior research has also found a strong positive link between two-way symmetrical communication and transparent communication with employee communication behaviours for sensemaking and sensegiving in crises (Kim, Citation2018). Managers and crisis communicators should be aware that when employees are not presented with all the needed information, their sensemaking can be based on rumours, assumptions, and organizational culture (Strandberg & Vigsø, Citation2016). Ravazzani (Citation2016) investigated internal crisis communication in multicultural environments and found that employee sensemaking was affected by cultural aspects. Yeomans and Bowman (Citation2021) integrated emotion in their investigation of internal crisis communication and sensemaking, and their recent study suggests that narratives of organizational competence and resilience, empathy, recognition and reassurance, and location and community, supported organizational belonging and helped to mitigate audience disagreement driven by uncertainty (Yeomans & Bowman, Citation2021).

Methodology

A qualitative multiple case study approach was chosen to be able to understand and explain internal crisis communication in the Nordic countries during the COVID-19 pandemic (Yin, Citation2018). A case study approach offered depth (Creswell, Citation2007; Flyvbjerg, Citation2011; Yin, Citation2018) and detail (Flyvbjerg, Citation2011), and multiple cases allowed a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon than a single case. Instead of generalization, the primary goal of this qualitative study was to hear the informants’ voices and understand the topic from their point of view. From an interpretive standpoint, the purpose of the current study was to make sense of the meanings people ascribed to the studied issues (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2011).

To enhance reliability, the researchers are open and transparent about the research practices and emphasize their visibility (Yin, Citation2018) while recognizing the partiality and limitations of the findings (Davies & Dodd, Citation2002). The researchers recognize that there is no neutral, value-free space for interpretation (Alvesson & Sköldberg, Citation2009), and that exposing assumptions, values, interests, and beliefs adds to the reliability of the research. One of the researcher’s role as co-worker with four of the participants is also recognized, and to reduce bias and error, a professional approach and detachment in the form of systematic data collection processes (Patton, Citation2015) were carried out in the interviews. The role of the researcher as a co-worker was helpful in the process of building rapport with the informants and contributed to a deeper understanding of their lived experiences (Amin et al., Citation2020).

Sample

Hotels and restaurants were chosen purposefully for the study since these types of hospitality organizations were strongly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic crisis and were thus considered to provide interesting and relevant insights on internal crisis communication. For the cases to predict similar results, a replication logic was used to choose cases with common characteristics (Yin, Citation2018). The four cases included one hotel and one restaurant each in Norway and Finland. More specifically, the cities of Stavanger (Norway) and Turku (Finland) were chosen as research sites due to their similar size and population. Fictional names were given to the companies to ensure their anonymity, referring to Hotel Fjord and Restaurant Mountain in Norway and Hotel Lake and Restaurant Forest in Finland.

Conducting multiple case studies and using replication logic enhances the transferability of the study. To gain a richer database for the analysis, data were collected from different levels of employees and managers (Chan & Hawkins, Citation2010), and altogether 16 leaders, middle managers, and employees were interviewed. Qualitative inquiry supports the purposeful choice of a relatively small sample of information-rich cases that provided insight and in-depth understanding instead of empirical generalizations (Patton, Citation2002). Half of the informants worked in Norway and the other half in Finland. Eleven of the participants were female, five were male, and they ranged in age from 24 to 60. The informants’ work experience in the companies ranged from 1.5 to 23 years and all of them had worked in the companies during the entire or most of the COVID-19 pandemic. The list of the informants can be found in .

Table 1. The informants in the multiple case study.

Data collection

Written consent was collected from the participants and one pilot interview was conducted with a Finnish hotel director to review the data collection plans and procedures (Yukl, Citation2013). As a result of the pilot interview, questions were rephrased and reorganised and constructs were reviewed, thus contributing to the validity of the study. Qualitative semi-structured interviews provided structure but gave room for follow-up questions and spontaneous narratives. The interviews took place in-person (8 interviews), via an online video communication platform (7 interviews), and as a phone interview (1 interview). The interviews were conducted during the months of February, March, and April 2021 and they lasted on average 40 minutes (varying from 20 to 70 minutes). The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim, remaining true to the informants’ statements, and including repetition, laughter, and hesitation in the textual data (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2015). Citations from the interviews were translated from Finnish and Norwegian to English by one of the researchers who is fluent in all three languages, making sure that the content and the style of the wording remained the same as in the original quotations. In line with the data protection legislation (see Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Citation2021), the personal data collected from the participants was stored and processed safely to protect the identities of the companies and the informants.

Data analysis

A combination of thematic and narrative analysis was used to analyse the interview data. After becoming acquainted with the interview transcripts, notes were written down for each individual case. Computer-assisted thematic analysis was conducted with NVivo to identify, analyse, and report patterns within the qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The initial codes were linked together and split into subcategories (Coffey & Atkinson, Citation1996), and the process was repeated until the most appropriate classification of the codes was found. As a result, the main themes emerged from the data set. The themes were reviewed and named to have better control of the data (see for the main themes, findings, and illustrating citations). Two informants were included in the coding process by selecting a few of the coding categories and asking the informants whether these categories made sense to them. These informants confirmed that the researchers’ interpretation of the data was a truthful and accurate depiction of their experience (Cypress, Citation2017), enhancing the credibility and confirmability of the findings.

Table 2. The main themes, findings, and illustrating citations.

The informants narrated their experiences spontaneously when asked to share stories of internal crisis communication at their workplace. The narratives were extracted from the data for further analysis to find potential conflicts and sequences within and between cases (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2015). Both in thematic and narrative analysis, each case was analysed individually before scrutinizing patterns across cases and drawing cross-case conclusions (Yin, Citation2018).

To ensure credibility and transparency in the research process, the methods of inquiry have been openly documented and their implications for the findings have been further discussed (Patton, Citation2015). Special attention was given to the process of data collection, identification and analysis, and the interviews were recorded in order to enable detailed scrutiny (Cypress, Citation2017). The results of the study are based on the interpretations of the researchers; however, revealing the researcher’s influence on the study, openly describing the research process, providing citations from the interviews, and having informants confirm some of the coded categories contribute to the quality of the study through minimizing possibilities of bias and error.

Results

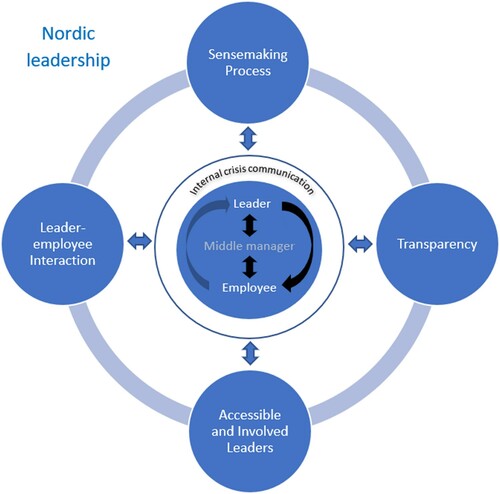

The findings are based on four case studies. Stavanger, Norway and Turku, Finland represent two similar-sized Nordic cities where hotels and restaurants were chosen based on their size and location by using replication logic. Hotel Fjord and Hotel Lake are middle-sized chain hotels with about 200 rooms located in the city centre of Stavanger (Hotel Fjord) and Turku (Hotel Lake) that offer facilities such as 24-hour reception, breakfast, bar, and meeting rooms. The hotels stayed open during the entire COVID-19 pandemic, but the number of employees decreased from about 30 to 15 employees at Hotel Fjord and from about 60 to 40 or 20 employees at Hotel Lake, depending on whether its restaurant was open or closed due to infection control measures. Restaurant Mountain and Restaurant Forest are middle-sized restaurants with a central location in Stavanger and Turku, respectively, and have between 20 and 30 employees. The number of employees at Restaurant Mountain decreased slightly, while no significant change was seen in Restaurant Forest during the crisis. Both establishments needed to close their doors at least once during the pandemic, thus all restaurant employees in the study experienced being laid off during the crisis. The main themes and cross-case patterns that emerged from the analysis were sensemaking process, transparency, accessible and involved leaders, and leader-employee interaction (see ).

Sensemaking process

The new and unexpected situation and the uncertainty caused by the crisis intensified the informants’ sensemaking, being most intense at the beginning of the pandemic. A waiter at Restaurant Mountain explained: “There was a lot of uncertainty at the very beginning when it started, people were scared of losing their jobs” (interviewee 7), while a receptionist at Hotel Fjord stated: “It was an entirely new situation, and no one knew how it was going to be, how it was going to go” (interviewee 4). On the other hand, a receptionist at Hotel Lake said: “Well, let’s say that it has been surprisingly hard […] it has been quite unpredictable” (interviewee 12). The interviews took place one year after the COVID-19 pandemic broke out and while the participants described feelings of fear, anxiety, concern, stress, and frustration they also explained that they were getting used to the situation.

Leaders and employees had coinciding perceptions of the internal crisis communication and experienced similar challenges and successes during the crisis. Taking in quarantine guests at Hotel Fjord was described as stressful and chaotic both by the hotel director and the receptionists, whilst at Hotel Lake, different levels of middle managers perceived that changing the breakfast routines multiple times during the pandemic was an inconvenience for the work in the reception. Employees were understanding toward the new situation and when asked about their leaders’ internal crisis communication, a shift manager at Restaurant Forest stated: “I would describe it as good, considering the circumstances” (interviewee 15). A waiter at Restaurant Mountain described the timing of the internal crisis communication:

I don’t really have any complaints about the timing because we don’t get notified by the government at an especially good time. Of course, we haven’t been notified in a very good time, but neither have those that have given the information to us. (interviewee 8)

When there are for example new regulations on Monday, and it is allowed to play Shuffleboard in the lobby. Suddenly, you might have 20 guests […] in the lobby at the same time […]. Are you going to follow the rules that say it is OK or are you going to think since there are 20 people in the lobby and I have to react? Now I have to do something because everyone has to keep their distance from each other and so on. (interviewee 4)

He cannot have all the answers either because it is not always black and white. And then we need to contribute with what we have learned from others and then there are conversations, and the ball is thrown and we kind of find out that OK, it is logical to do it like this. (interviewee 8)

Transparency

All the cases clearly indicated that the internal crisis communication in the hotels and restaurants was open and transparent. Employees perceived that leaders and middle managers shared all available information during the crisis. A receptionist at Hotel Lake stated: “Everything has been told openly” (interviewee 12) while a waiter at Restaurant Mountain explained: “I don’t feel like they held anything back or hid something from us, all the information has been shared all along” (interviewee 7). Similarly, a shift manager at Restaurant Forest said: “You keep in contact with your subordinates and the entire staff and tell what you know. So that employees do not feel like someone is obscuring information” (interviewee 15). Leaders, too, referred to the open and transparent communication, and the managing director at Restaurant Mountain expressed: “There is no point to beat around the bush, it is better to say it as it is” (interviewee 5). At Hotel Fjord, the hotel director claimed: “I think that my leadership is very open. I think that … the door is always open, you can come in when you want, people can say what they want” (interviewee 1), a statement that was supported by the Hotel Fjord’s assistant manager in reception:

It has been very good that it has been very open, there have not been things that we don’t get to know […]. The door has always been open, so if we had some questions or concerns or something like that you could just go in. (interviewee 2)

Accessible and involved leaders

The interviewees described a lack of hierarchy, as stated by a service manager at Hotel Lake: “There is no wall in the middle, so you can talk or open up to any supervisor” (interviewee 10). Further, the leader-subordinate relationship was perceived as friendly and caring. A receptionist at Hotel Lake stated: “I feel like the boss is more like a friend than a manager” (interviewee 12), and a waiter at Restaurant Mountain said: “They are always not just our bosses, but colleagues. So, you get a feeling that they care about us” (interviewee 7). The middle managers and leaders were also perceived as present and accessible during the crisis. Referring to the hotel director, a receptionist at Hotel Fjord explained: “You could always call him and ask for help. So, he was accessible very … a lot more than before” (interviewee 4). Restaurant Forest differed slightly from the other cases in terms of the presence of the leaders; due to the owners living in another city, the middle managers had an active role in the internal crisis communication. When asked about how the owners could have improved their communication, the restaurant manager at Restaurant Forest replied: “with more physical presence […] especially during the more critical times” (interviewee 13).

However, leaders were also described as more involved in the daily operations and decision-making processes during the crisis than before the pandemic, through actively communicating and exchanging information with middle managers and employees. The executive head chef at Restaurant Mountain said:

Compared to before, now we get concrete information on the guidelines that need to be maintained. And we did not have that before, and at the time the managing director was more in charge of the administrative and we, the people on the floor, did what we are supposed to do there. But now, if we are to do something, we almost always need to run it by the managing director or the leader to hear if it is right. (interviewee 6)

He has probably had a bit more control than […] before because when there is no pandemic it is possible to run your department as you see fit […]. But during the pandemic, I feel that it has been a lot stricter on how things need to be done. (interviewee 2)

Leader-employee interaction

Employees communicated actively during the crisis, as stated by a waiter at Restaurant Mountain: “At once when we have questions, we know that we can go and ask them and that we get an answer” (interviewee 7). However, there was found to be a lack of employee consultation and involvement in decision-making, as indicated by a service manager at Hotel Lake:

I do not know if any one of us has actively thought about sharing any kind of ideas or suggestions upwards […]. Maybe a suitable platform to do that has not been offered either, that someone would have asked about your opinion on the matter. (interviewee 11)

We get information on how things are now, but we can also come with suggestions and explain our side of the case, how do we want it, and they listen. And then they say why it works and why it does not work. (interviewee 7)

Leader-employee interaction took place face-to-face, on internal platforms, and on social media. Face-to-face communication was perceived as the best and most effective way to communicate in a crisis. A service manager at Hotel Lake stated: “Of course, it is always a different matter if it comes directly in a meeting or that someone tells you directly and you are able to come up with follow-up questions” (interviewee 10), while a shift manager at Restaurant Forrest explained:

If the situation would allow it more, maybe I personally prefer meetings. So that everyone is physically in the same place at the same time when the communication becomes a lot easier because questions can be answered straight away, and maybe also other person’s reactions can be seen better. (interviewee 15)

Summary of the findings

summarizes the main findings in the study. The internal crisis communication took place between leaders, middle managers, and employees. The results showed that the leaders were perceived as more visible and involved in the day-to-day operations during the crisis, for instance through their active communication and information input. Accordingly, more top leader control implied less autonomy and flexibility among middle managers compared to pre-pandemic operations. Although the leaders were transparent, accessible and in direct contact with the employees, the findings suggest that the employees did not communicate upwards to the same extent, and were neither actively consulted in decision-making, nor asked for their ideas and suggestions during the pandemic. Thus, the increased hierarchical leadership communication during the crisis indicates a contrast to the Nordic leadership model. The four main themes show how Nordic leadership characteristics were reflected in the internal crisis communication in the Finnish and Norwegian hotels and restaurants (see ).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine internal crisis communication during the COVID-19 pandemic as viewed through the lens of Nordic leadership. The findings from the interviews revealed that central aspects of Nordic leadership such as openness and transparency (Andreasson & Jamholt, Citation2018; Andreasson & Lundqvist, Citation2018) were reflected in the internal crisis communication of all four cases. The employees perceived that information concerning the crisis was shared openly and not withheld or concealed. However, there was also an understanding that the middle managers and leaders did not always have all the answers, and that there was a need for collective discussion and information sharing to make sense of the complexity of the situations they encountered. This resonates with how other researchers have addressed the importance of transparency in a crisis (Erickson, Citation2021; Palttala et al., Citation2012) and points toward open communication as one of the guidelines for effective crisis communication in the hospitality industry (Sellnow & Sarabakhsh, Citation1999). In fact, prior research has described a negative relationship between internal crisis communication and withholding information or failing to be honest (Sellnow & Sarabakhsh, Citation1999), and a lack of transparency (Mazzei & Ravazzani, Citation2015). The results of this multiple case study further imply that the transparency demonstrated by the Finnish and Norwegian leaders facilitated the employees’ sensemaking and increased their trust in the middle managers and leaders, which is another important variable of effective communication (Longstaff & Yang, Citation2008). The factors that contributed to effective internal crisis communication during the COVID-19 pandemic are illustrated in . This reasoning is supported by the extant literature. For instance, Kim (Citation2018) found that transparent internal crisis communication was a positive antecedent for employee communication behaviours for sensemaking and sensegiving, while a study by Strandberg and Vigsø (Citation2016) suggested that when employees were not presented with all the information their sensemaking was directed by rumours, assumptions, and the organizational culture. It is thus reasonable to assume that the open communication, trust, and transparency that was reflected in the internal crisis management contributed to coinciding perceptions and sensemaking processes among employees and managers and strengthened a feeling that they faced the pandemic together as a community.

Figure 2. Factors that contributed to effective internal crisis communication in the hotels and restaurants during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regardless of their experience, the managers recognized the need to stay calm and supportive in a crisis. However, compared to the managers with less experience, the hotel director with 23 years of experience seemed to be more aware of the internal crisis communication processes, stating the importance of interaction, keeping a short distance to the subordinates, and limiting the amount of information and changes, even though some of these principles did not always work in practice. In fact, the managers clearly expressed that they, too, were learning new things and finding the best solutions through handling the crisis. Accordingly, gaining a better control of the situation was seen as a result of trying and failing. This strengthens the impression of egalitarianism and non-hierarchical structures in the organizations, where learning is viewed as the result of dialogue and mutual sharing of knowledge and experiences. This is an important finding because previous studies have shown that employees’ interpretation and sensemaking of how management communicates in crisis situations is central to successful internal crisis communication (Strandberg & Vigsø, Citation2016). The findings in this study show that the employees’ sensemaking processes during the COVID-19 pandemic largely coincided with the managements’ sensemaking and interpretation of the internal crisis communication, indicating openness and a strong sense of equality in the organizations.

An important finding from the study is that although there was active leader-employee interaction, the role of the employees in the internal crisis communication in the hotels and restaurants was somewhat limited to asking questions and they were not encouraged to share their opinions upwards. While the leaders and middle managers were perceived to be present and accessible during the crisis, several of the employees mentioned an absence of participation in decision-making processes during the pandemic. Lack of channels to share their ideas and suggestions upwards resulted in the employees feeling uncomfortable about expressing their own opinions or presenting suggestions for improvement. This coincided with a stronger involvement by the top leaders in presenting and exchanging information concerning the daily operations than before the crisis, indicating a somewhat more hierarchical management approach compared to pre-pandemic operations. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that when the leaders became more visible, the middle managers experienced less flexibility and autonomy than before the pandemic when they had been responsible for running their department with little interference from those in leadership positions above them. This contrasts with prior studies by Heide and Simonsson (Citation2014) and Ravazzani (Citation2016), which highlighted line managers’ role in internal crisis communication. Furthermore, Andreasson and Lundqvist (Citation2018) reported a high degree of autonomy and flexibility, as well as the delegation of power, responsibility, and influence as central aspects of Nordic leadership. Thus, it seems that while openness and transparency prevailed in the hotels and restaurants during the pandemic, leadership communication became - in some instances - more hierarchical than before the crisis. This may be interpreted as that the leaders experienced a stronger need for control than during normal operations, thus indicating a break with aspects of Nordic leadership such as participation and consensus-seeking.

There could seem to be a contrast between the open communication practiced by the management and their willingness to listen to the employees, which, again, made the employees less prone to speak up (Morrison, Citation2011). Previous research has indeed highlighted the importance of participatory communication (Ecklebe & Löffler, Citation2021), including employee voices, and understanding their views and behaviours (Kim & Lim, Citation2020) for effective and high-quality internal crisis communication. This indicates that effective internal crisis communication is characterized by not just listening to employees, but actively encouraging their voices and opinions. The findings in this study indicate that although the managers listened to their employees, they did not actively encourage the employees to share suggestions and views concerning the internal handling of the pandemic. The findings of the Restaurant Mountain case, however, provide a contrast to the three other cases and suggested that the management listened to the employees who provided both input and suggestions during the pandemic. While the interviewees in all of the cases referred to two-way communication, it seems that this was most fully realized at Restaurant Mountain where the employees experienced being genuinely involved in the internal crisis communication. When employees feel heard, they are more likely to be more involved and committed, and more open to new ideas proposed by the management (Brownell, Citation2008). According to Erickson (Citation2021), shared decision-making in crisis can give a sense of control to employees, as was seen at Restaurant Mountain where the employees felt invested in the decisions that affected them the most.

Conclusion

This multiple case study revealed somewhat contrasting results concerning managerial openness and employee participation in the internal crisis communication in hotels and restaurants in Finland and Norway during the COVID-19 pandemic. On the one hand, the internal crisis communication was perceived as open and transparent, which contributed to employees’ sensemaking and trust in their managers. On the other hand, employees were not actively consulted in decision-making and the managerial processes were experienced as more hierarchical during the crisis, indicating a conflict between the internal crisis communication and certain aspects of Nordic leadership such as cooperation, consensus-seeking, egalitarianism, and delegation of responsibility.

Managerial implications

The findings of this study have important managerial implications. First, leaders and middle managers should realize the significance of transparency and interaction in striving for effective internal crisis communication and maintaining trust with their subordinates. During the crisis, the existing internal communication practices and routines characterized by Nordic leadership values were challenged due to the urgency and uncertainty of the crisis. However, the findings suggest that the openness and transparency of Nordic leadership prevailed in the unexpected crisis and contributed to managerial learning and solution-finding through crisis communication and management. Moreover, the fact that leaders were present and accessible during the crisis made it easier for the employees to make sense of and cope in the uncertain situation. Second, the findings emphasize the importance of participative communication during a crisis. Nordic leadership has been described with consensus-seeking (Warner-Søderholm, Citation2012b), cooperation (Andreasson & Lundqvist, Citation2018), and delegation of responsibility (Lindell & Arvonen, Citation1996), however, the findings show that employees were not actively consulted nor involved in communication about decision-making processes during the pandemic. Accordingly, managers should aim at finding a balance between control and participation when communicating about internal decision-making during a crisis. Leaders and middle managers need to consult employees and encourage them to be actively involved in the organizational crisis management, to ensure that potentially good ideas and suggestions from the employees are conveyed and that the organization draws on the full potential of employees as strategic communicators (Simonsson & Heide, Citation2018).

Research implications

This study contributes to the crisis communication literature through increasing knowledge of sensemaking processes within internal crisis communication, and showing how Nordic leadership perspectives contribute to transparency and trust through internal crisis communication, which has received little attention from scholars until now. Moreover, while many previous studies have investigated internal crisis communication either from a managerial or employee perspective, this multiple case study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding through a multi-level analysis that included the perspectives of leaders, middle managers, and employees. The internal crisis communication practices in this study reflect the importance of aspects of Nordic leadership such as openness, transparency, short power distance, and active interaction in crisis communication. However, the findings also illustrate how leadership practices and communication became more hierarchical during the pandemic. Thus, this paper illuminates a potential conflict between Nordic leadership style and internal crisis communication practices. This calls for more research attention to issues of leader-employee interaction, involvement and engagement during times of crisis in organizations. The findings in this paper contribute to filling the knowledge gap concerning whether and how Nordic leadership aspects can contribute to more inclusive and open internal crisis communication from both managerial and employee perspectives.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

One of the limitations of the current study is that the small sample provides little basis for generalization of the findings. While multiple cases were chosen to get a more thorough understanding of the phenomenon, the findings of four cases cannot be generalized statistically to larger populations. Thus, a limitation lies in that it is not possible to say for certain that the findings of this study will be found in other hotels and restaurants. However, according to Flyvbjerg (Citation2006), it is possible to generalize theoretically from case studies through arguing that the processes revealed in the cases in this study will most probably be effective in other similar cases. Based on this argument, it is likely that the findings from this study are relevant for and may be found in other similar hotels and restaurants. The application of replication logic contributes to strengthen the reliability of this study, since the cases revealed similar themes and experiences. Instead of “representativeness”, it is thus more suitable to talk about “representation” when discussing the value of case studies (Miles, Citation2015). The representativeness may then be examined further on, for example through repeating the study in other cases or through conducting larger scale surveys. Furthermore, the aim of this study was not to make generalizations, but rather to acquire new knowledge by understanding the phenomenon from the informants’ point of view and to contribute to filling a knowledge gap in the research area. In fact, we believe that this multiple case study could be a springboard for further studies of internal crisis communication in the Nordic leadership context. Future investigations are needed in this research area and we propose that a wider study with a larger sample size be undertaken and recommend that future work is carried out by targeting all five Nordic countries. Future studies could also investigate how different cultural or leadership contexts impact internal crisis communication in organizations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data is not available due to privacy/ethical restrictions. Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2009). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research. Sage Publications.

- Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16(10), 1472–1482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.02.005

- Andreasson, U., & Jamholt, A. H. (2018, December 5). Nordic leadership – What makes it so special? https://www.norden.org/en/news/nordic-leadership-what-makes-it-so-special

- Andreasson, U., & Lundqvist, M. (2018). Nordic leadership. Nordic Council of Ministers. Analysis no. 2. https://doi.org/10.6027/ANP2018-835

- Avolio, B. J. (2004). Leadership development in balance: MADE born. Taylor & Francis Group. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uisbib/detail.action?docID=227450

- Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00016-8

- Bertella, G. (2022). Discussing tourism during a crisis: Resilient reactions and learning paths towards sustainable futures. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 22(2), 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2022.2034527

- Biddle, I. (2005). Approaches to management styles of leadership. Ecodate, 13(3), 1.

- Bogren, M., & Sörensson, A. (2021). Tourism companies’ sustainability communication – Creating legitimacy and value. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(5), 475–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1974542

- Boin, A. (2019). The transboundary crisis: Why we are unprepared and the road ahead. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 27(1), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12241

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brownell, J. (2008). Exploring the strategic ground for listening and organizational effectiveness. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 8(3), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250802305295

- Chan, E. S. W., & Hawkins, R. (2010). Attitude towards EMSs in an international hotel: An exploratory case study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(4), 641–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.12.002

- Coffey, A., & Atkinson, P. (1996). Making sense of qualitative data: Complementary research strategies. Sage Publications.

- Coombs, W. T. (2012). Ongoing crisis communication. Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications.

- Cypress, B. S. (2017). Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research: Perspectives, strategies, reconceptualization, and recommendations. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 36(4), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000253

- Davahli, M. R., Karwowski, W., Sonmez, S., & Apostolopoulos, Y. (2020). The hospitality industry in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: Current topics and research methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207366

- Davies, D., & Dodd, J. (2002). Qualitative research and the question of rigor. Qualitative Health Research, 12(2), 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973230201200211

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications.

- Ecklebe, S., & Löffler, N. (2021). A question of quality: Perceptions of internal communication during the Covid-19 pandemic in Germany. Journal of Communication Management, 25(3), 214–232. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-09-2020-0101

- Erickson, S. (2021). Communication in a crisis and the importance of authenticity and transparency. Journal of Library Administration, 61(4), 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2021.1906556

- Fink, S. (1986). Crisis management: Planning for the inevitable. Americal Management Association.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Case study. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 301–316). Sage Publications.

- Frandsen, F., & Johansen, W. (2011). The study of internal crisis communication: Towards an integrative framework. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 16(4), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563281111186977

- Gjerald, O., Dagsland, ÅBD, & Furunes, T. (2021). 20 years of Nordic hospitality research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1880058

- Grenness, T. (2003). Scandinavian managers on Scandinavian management. International Journal of Value-Based Management, 16(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021977514976

- Grenness, T. (2011). Will the ‘Scandinavian leadership model’ survive the forces of globalisation? A SWOT analysis. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 7(3), 332–350. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBG.2011.042062

- Guzzo, R. F., Wang, X., Madera, J. M., & Abbott, J. (2021). Organizational trust in times of COVID-19: Hospitality employees’ affective responses to managers’ communication. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 93, 102778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102778

- Hall, C. M., & Saarinen, J. (2021). 20 years of Nordic climate change crisis and tourism research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1823248

- Hallin, C. A., & Marnburg, E. (2007). In times of uncertainty in the hotel industry: Hotel directors’ decision-making and coping strategies for dealing with uncertainty in change activities. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(4), 364–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701695077

- Haver, A., Akerjordet, K., & Furunes, T. (2014). Wise emotion regulation and the power of resilience in experienced hospitality leaders. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(2), 152–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.899141

- Heide, M., & Simonsson, C. (2014). Developing internal crisis communication: New roles and practices of communication professionals. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 19(2), 128–146. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-09-2012-0063

- Heide, M., & Simonsson, C. (2015). Struggling with internal crisis communication: A balancing act between paradoxical tensions. Public Relations Inquiry, 4(2), 223–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147X15570108

- Heide, M., & Simonsson, C. (2021). What was that all about? On internal crisis communication and communicative coworkership during a pandemic. Journal of Communication Management, 25(3), 256–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-09-2020-0105

- Hetland, H., & Sandal, G. (2003). Transformational leadership in Norway: Outcomes and personality correlates. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12(2), 147–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320344000057

- Hoarau, H. (2014). Knowledge acquisition and assimilation in tourism-innovation processes. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.887609

- Horgen, E. (2020, November 26). Dempet jobbfall også i oktober [Moderate job losses also in October]. https://www.ssb.no/arbeid-og-lonn/artikler-og-publikasjoner/dempet-jobbfall-ogsa-i-oktober

- House, R. J. (1996). Path-goal theory of leadership: Lessons, legacy, and a reformulated theory. The Leadership Quarterly, 7(3), 323–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(96)90024-7

- Jakobsen, E., Iversen, E. K., Nerdrum, L., & Rødal, M. (2021). Rapport: Norsk reiseliv før, under og etter pandemien [Report: Tourism in Norway before, during, and after the pandemic]. Menon Economics publication nr. 121/2021. https://www.nhoreiseliv.no/contentassets/6abc6856aad442bcb91b431d978d6042/rapport-norsk-reiseliv-for-under-og-etter-pandemien.pdf

- Johansen, W., Aggerholm, H. K., & Frandsen, F. (2012). Entering new territory: A study of internal crisis management and crisis communication in organizations. Public Relations Review, 38(2), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.11.008

- Jong, W. (2021). Evaluating crisis communication. A 30-item checklist for assessing performance during COVID-19 and other pandemics. Journal of Health Communication, 25(12), 962–970. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2021.1871791

- Jönsson, S. (1996). Perspectives of Scandinavian management. Gothenburg Research Institute.

- Kim, Y. (2018). Enhancing employee communication behaviors for sensemaking and sensegiving in crisis situations: Strategic management approach for effective internal crisis communication. Journal of Communication Management, 22(4), 451–475. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-03-2018-0025

- Kim, Y., & Lim, H. (2020). Activating constructive employee behavioural responses in a crisis: Examining the effects of pre-crisis reputation and crisis communication strategies on employee voice behaviours. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 28(2), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12289

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2015). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Sage Publications.

- Lämsä, T. (2010). Leadership styles and decision-making in Finnish and Swedish organizations. Revista de Management Comparat Internațional, 11(1), 139–149. http://rmci.ase.ro/ro/no11vol1/Vol11_No1_Article13.pdf

- Larsen, H. H., & Bruun de Neergaard, U. (2007). Nordic lights: A research project on Nordic leadership and leadership in the Nordic countries. https://paperzz.com/doc/8861953/nordic-lights

- Lindell, M., & Arvonen, J. (1996). The Nordic management style in a European context. International Studies of Management & Organization, 26(3), 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.1996.11656689

- Longstaff, P. H., & Yang, S.-U. (2008). Communication management and trust: Their role in building resilience to “surprises” such as natural disasters, pandemic flu, and terrorism. Ecology and Society: A Journal of Integrative Science for Resilience and Sustainability, 13(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-02232-130103

- López, A. M. (2021, September 15). Number of employees in the tourism industry in Norway from 2011 to 2019 (in 1000s). https://www.statista.com/statistics/858132/employee-number-of-the-tourism-industry-in-norway/

- Løvoll, H. S., & Einang, O. (2021). Transparent guiding: Contributions to theory of nature guide practice. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 22(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1955738.

- Maitlis, S., & Sonensheim, S. (2010). Sensemaking in crisis and change: Inspiration and insights from Weick (1988). Journal of Management Studies, 47(3), 551–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00908.x

- Marski, L. (2021). Matkailun suuntana kestävä ja turvallinen tulevaisuus [A safe and sustainable future as a trend in tourism]. TEM toimialaraportit 2021:1. Työ- ja elinkeinoministeriö [Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland]. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-327-773-1

- Mazzei, A., & Ravazzani, S. (2011). Manager-employee communication during a crisis: The missing link. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 16(3), 243–254. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563281111156899

- Mazzei, A., & Ravazzani, S. (2015). Internal crisis communication strategies to protect trust relationships: A study of Italian companies. International Journal of Business Communication, 52(3), 319–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488414525447

- Miles, R. (2015). Complexity, representation and practice: Case study as method and methodology. Issues in Educational Research, 25(3), 309–318. http://www.iier.org.au/iier25/miles.html

- Millar, D. P., & Heath, R. L. (2004). Responding to crisis: A rhetorical approach to crisis communication. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410609496

- Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment. (2021, February 22). Evaluation: Coronavirus pandemic reduced tourist spending by over 40% in Finland in 2020 [Press release]. https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/-//1410877/evaluation-coronavirus-pandemic-reduced-tourist-spending-by-over-40-in-finland-in-2020

- Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment. (n.d.). Finnish tourism in numbers. https://tem.fi/en/-/matkailu-lukuina

- Mittal, R., & Dorfman, P. W. (2012). Servant leadership across cultures. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2012.01.009

- Moos, L. (2013). Transnational influences on values and practices in Nordic educational leadership: Is there a Nordic model? Springer Netherlands. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uisbib/detail.action?docID=1206409

- Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373–412. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.574506

- Mykletun, R. J. (2011). Festival safety – Lessons learned from the Stavanger Food Festival (the Gladmatfestival). Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(3), 342–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.593363.

- Northouse, P. G. (2018). Leadership: Theory and practice. Sage Publications.

- Norwegian Centre for Research Data. (2021). About NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data. https://www.nsd.no/en/about-nsd-norwegian-centre-for-research-data/

- Nurmi, O., & Veistämö, T. (2020). Matkailualoilla suhteellisesti eniten yritystukien saajia – Uudellamaalla majoitusalan tuet vastaavat murto-osaa menetyksistä [In relative terms, there are most business aid recipients in tourism – In Uusimaa, compensation for the accommodation sector accounts for a fraction of losses]. https://www.stat.fi/tietotrendit/artikkelit/2020/matkailualoilla-suhteellisesti-eniten-yritystukien-saajia-uudellamaalla-tuet-vastaavat-murto-osaa-menetyksista/

- Palttala, P., Boano, C., Lund, R., & Vos, M. (2012). Communication gaps in disaster management: Perceptions by experts from governmental and non-governmental organizations. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 20(1), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5973.2011.00656.x

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325002001003636

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Sage Publications.

- Pearson, C. M., & Clair, J. A. (1998). Reframing crisis management. Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 59–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/259099 https://doi.org/10.2307/259099

- Pöllänen, K. (2006). Northern European leadership in transition – A survey of the insurance industry. Journal of General Management, 32(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/030630700603200104

- Poulsen, P. T. (1988). The attuned corporation: Experience from 18 Scandinavian pioneering corporations. European Management Jounal, 6(3), 229–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0263-2373(98)90008-1

- Ravazzani, S. (2016). Exploring internal crisis communication in multicultural environments: A study among Danish managers. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 21(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-02-2015-0011

- Ritchie, B. W., Bentley, G., Koruth, T., & Wang, J. (2011). Proactive crisis planning: Lessons for the accommodation industry. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(3), 367–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.600591

- Rybalka, M. (2020, Juni 12). Hvilke næringer har fått mest i kontantstøtte? [Which industries have received the most cash support?]. https://www.ssb.no/teknologi-og-innovasjon/artikler-og-publikasjoner/hvilke-naeringer-har-fatt-mest-i-kontantstotte

- Schramm-Nielsen, J., Lawrence, P., & Sivesind, K. H. (2004). Management in Scandinavia: Culture, context and change. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Seeler, S., Zacher, D., Pechlaner, H., & Thees, H. (2021). Tourists as reflexive agents of change: Proposing a conceptual framework towards sustainable consumption. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(5), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1974543

- Sellnow, T., & Sarabakhsh, M. (1999). Crisis management in the hospitality industry. Hospitality Review, 17(1), 53–61. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/hospitalityreview/vol17/iss1/6

- Simonsson, C., & Heide, M. (2018). How focusing positively on errors can help organizations become more communicative. Journal of Communication Management, 22(2), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-04-2017-0044

- Smith, P. B., Andersen, J. A., Ekelund, B., Graversen, G., & Ropo, A. (2003). In search of Nordic management styles. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 19(4), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0956-5221(03)00036-8

- Statistics Finland. (2020, August 28). Talouden tilannekuva: korona on koetellut vaihtelevasti eri toimialoja [Economic snapshot: Covid-19 has put different industries to the test in various ways]. http://www.stat.fi/uutinen/talouden-tilannekuva-korona-on-koetellut-vaihtelevasti-eri-toimialoja

- Statistics Norway. (2021, March 5). Tourism satellite accounts. https://www.ssb.no/en/nasjonalregnskap-og-konjunkturer/nasjonalregnskap/statistikk/satellittregnskap-for-turisme

- Strandberg, J. M., & Vigsø, O. (2016). Internal crisis communication: An employee perspective on narrative, culture, and sensemaking. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 21(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-11-2014-0083

- Taylor, J. R., & Van Every, E. J. (2000). The emergent organization: Communication as its site and surface. Routledge.

- Taylor, M. (2010). Towards a holistic organizational approach to understanding crisis. In W. T. Coombs, & S. J. Holladay (Eds.), The handbook of crisis communication (pp. 698–704). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444314885.ch36

- Tsai, C.-H., & Chen, C.-W. (2011). Development of a mechanism for typhoon- and flood-risk assessment and disaster management in the hotel industry – A case study of the Hualien area. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(3), 324–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.601929

- Warner-Søderholm, G. (2012a). But we’re not all Vikings! Intercultural identity within a Nordic context. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 29. https://biopen.bi.no/bi-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/93722/Warner-S%c3%b8derholm_JICC_2012.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Warner-Søderholm, G. (2012b). Culture matters: Norwegian cultural identity within a Scandinavian context. SAGE Open, 2(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244012471350

- Warner-Søderholm, G., & Cooper, C. (2016). Be careful what you wish for: Mapping Nordic cultural communication practices & values in the management game of communication. International Journal of Business and Management, 11(11), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v11n11p48

- Weick, K., & Sutcliffe, E. (2003). Hospitals as cultures of entrapment: A re-analysis of the Bristol Royal Infirmary. California Management Review, 45(2), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166166

- Weick, K. E. (1988). Enacted sensemaking in crisis situations. Journal of Management Studies, 25(4), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1988.tb00039.x

- Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2015). Managing the unexpected: Sustained performance in a complex world. Wiley.

- Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Obstfeld, D. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science, 16(4), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0133

- World Trade Organization. (2020, May 28). Trade in services in the context of COVID-19. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/services_report_e.pdf

- Yeomans, L., & Bowman, S. (2021). Internal crisis communication and the social construction of emotion: University leaders’ sensegiving discourse during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Communication Management, 25(3), 196–213. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-11-2020-0130

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage Publications.

- Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in organizations. Pearson Education Limited.