ABSTRACT

Environmental sustainability in the rural tourism and hospitality (hereafter abbreviated RT) sector has received increased attention in the last decade. Although several reviews have examined sustainable tourism, a dedicated review of environmental sustainability initiatives in the RT sector is absent. To address this gap, we present a systematic literature review of 100 research articles addressing RT and environmental sustainability from 39 journals. The review indicates that this area is growing and primed for further research. We present three main contributions. First, we identify different stakeholders of RT environmental sustainability. Second, we summarize the driving and barrier roles of each stakeholder in environmentally sustainable RT. Third, we present the benefits of environmentally sustainable RT. We observe the pivotal roles played by entrepreneurs, community, tourists, and policymakers in the development of environmentally sustainable RT but note that stakeholders like corporations, non-governmental organizations, and media have received little or no attention. Based on the gaps we identified, we outline five suggestions for future research in the area and present for each a variety of possible research questions. We then summarize our findings into a RT environmental sustainability framework and discuss the academic, practical, and policy implications of the study.

1. Introduction

The rural tourism and hospitality sector as a whole is still far from sustainable due to adverse impacts such as community exploitation (Ghoddousi et al., Citation2018), environmental ill-treatment (Randelli & Martellozzo, Citation2019; Majdak & De Almeida, Citation2022; Madanaguli, Kaur, Mazzoleni, & Dhir, Citation2022), and waste generation (Buckley, Citation2012). The United Nations Environment Program observed that the tourism industry generates around 14% of the world’s waste, and at its current rate of resource consumption, it is expected that by 2050 it will have increased its energy consumption by 154%, greenhouse gas emission by 131%, and water consumption by 152% (United Nations Environment Program, Citationn.d.). These environmental concerns have prompted extensive research examining sustainability issues in rural tourism.

At the same time, literature on this topic has called attention to the potential of rural tourism, through the effective use of cultural and natural resources, to create sustainable rural communities, enhance rural income, and protect natural resources (Lee et al., Citation2021; Mikhaylova, Wendt, Hvaley, Bógdał-Brzezińska, & Mikhaylov, Citation2022). The ongoing interest in both policy and practice can be attributed to the immense impact RT has had on rural societies, including generating employment and encouraging sustainable rural development (Guaita Martínez et al., Citation2019). For instance, according a report by the department of environment, food and rural affairs, RT activities generated as much as $16.2 billion for the UK economy and generated about 14% of the jobs in rural areas of the UK (Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs 2019). Further, Asian countries like China have started providing policy support for tourism development, thus introducing a new paradigm of RT experiences (Gao et al., Citation2019). But, as stated earlier, growth comes with consequences. Every rural area has a “carrying capacity” for tourists (Bertocchi et al., Citation2020), beyond which the development of RT may come at the cost of social, cultural, and environmental sustainability (Stronza & Gordillo, Citation2008). It is therefore pertinent to investigate the role of sustainability in RT at this juncture.

The popularity of sustainable tourism is evident from several reviews (Buckley, Citation2012; Byrd, Citation2007). Particularly in recent years, literature review studies have examined a range of topics including big data and related methods (Xu et al., Citation2020), energy consumption in the tourism industry (Zhang & Zhang, Citation2020), and measuring the sustainability of tourist destinations (Alfaro Navarro et al., Citation2020), among other issues. The importance of sustainability in RT and the profound impact it has on rural communities call for a consolidation and synthesis of prior literature so that paths for future research may be identified. Despite its utility, a comprehensive literature review study that examines the issues pertaining to the role of sustainability in RT has not yet been conducted, and so it is necessary to conduct such a study and identify the drivers, stakeholders, and benefits of sustainability in RT as discussed in current literature.

To address the gaps in the prior literature, the current review is guided by five main research questions (RQs). RQ1. What is the research profile of the research on sustainability in RT? RQ2. Who are the major stakeholders in sustainability in RT? RQ3. What are the major drivers and barriers of RT sustainability? RQ4. What are the benefits and consequences of adopting sustainable RT? RQ5. What are the limitations, gaps, and areas for future investigation in the current understanding of RT and sustainability?

This study utilizes a systematic literature review (SLR) method and performs a content analysis of relevant literature and associated findings. The findings suggest that RT sustainability has significantly evolved in recent years with research addressing the roles of several stakeholders in establishing sustainable RT. The driving and barrier roles of stakeholders like policymakers, tourists, community, and entrepreneurs appear to have received disproportionately more research attention than have other stakeholders such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), media, and corporations. Furthermore, we find that the majority of reviewed studies are context-specific and so unsuited to the development of general RT sustainability policy. We then integrate our findings into a RT sustainability framework that summarizes the state of the present literature.

The rest of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 more clearly defines the scope of the review, and Section 3 presents a brief overview of the SLR method used in the study, followed by a quantitative descriptive analysis of the sample in Section 4. Section 5 presents a detailed discussion of the current research themes in RT and sustainability literature. Section 6 provides an overview of identified gaps in the existing research and advances five future research suggestions. In Section 7, we outline our research framework. The final section concludes the review with a discussion of the implications and limitations of our study.

2. Scope of the review

Rural tourism and hospitality (RT) may be defined as the packaging of rurality of a rural region for tourism consumption (Sharpley & Sharpley, Citation1997), where rurality implies the factors that provide a rural area with a sense of authenticity as a tourist area due to culture, heritage, customs, and local sceneries (Sharpley & Sharpley, Citation1997). RT enterprises in a rural area play a major role in the commodification of rurality by providing a variety of “authentic” rural services like hospitality (Cucari et al., Citation2019), transport (Smith et al., Citation2019), hiking trails (Botella-Carrubi et al., Citation2019), and other services that tourists desire. Thus, as an extension, sustainable RT can be defined as rural tourism that keeps track of both existing and future social, environmental, and economic needs while meeting the demands of tourists, communities, and other stakeholders (World Tourism Organization, Citation2004). These stakeholders may include tourists, industries, host communities, and local environments.

Rural tourism as a legitimate tourist movement evolved in the 1970s, but its origins can be tracked back to the seventeenth century (Kaptan Ayhan et al., Citation2020). The purpose of engaging in rural tourism is to get away from the commotions of city life to enjoy the calm countryside. This has led to the creation of variety of RT businesses in rural areas to accommodate and entertain these tourists (Stephen & Donald, Citation1997). Rural tourism has evolved considerably since then, particularly in Europe, thanks to policy and government support for its development (Hjalager, Citation2014; Lane, Citation1994; Panyik et al., Citation2011). RT has therefore been a hotly debated topic due to its paradoxical influence on rural areas. On the one hand, it has the potential to promote the sustainable development of an area not only economically, but also socially and environmentally. On the other hand, it can be a major cause of cultural and environmental degradation in that area. This apparent paradox requires that sustainability be defined through a broader lens. Therefore, borrowing from the concept of triple bottom line (Elkington, Citation1998), we define sustainability in this review as not only environmental sustainability, but as social and economic sustainability of the area as well (Coroș et al., Citation2021).

3. Method: systematic literature review (SLR)

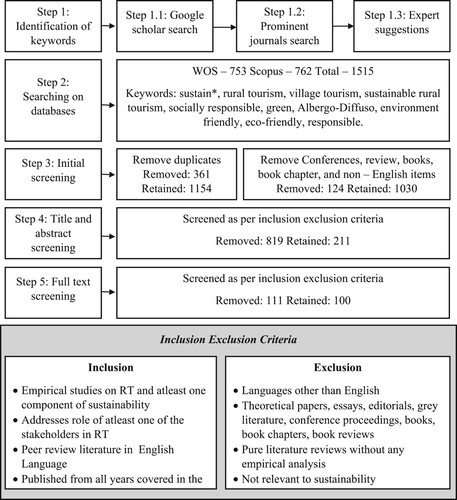

This review utilizes an SLR process to capture and analyze the literature pertaining to RT and sustainability (Tranfield et al., Citation2003). The review of relevant literature identifies the research profile, emergent themes, gaps, limitations, and suggestions for future research. The SLR method offers various advantages over the traditional review methods (e.g. narrative reviews), such as reduction of bias and omission (Tranfield et al., Citation2003), and enhances reproducibility, quality, and organization of the review (Danese et al., Citation2018). The SLR method is also a popular method in the field of sustainable tourism (Ardoin et al., Citation2015). To ensure adequate coverage of relevant literature, a two-step process was utilized to identify relevant literature. represents the SLR process followed in this review.

3.1. Identification of keywords

The identification of keywords followed a three-step process. First, the keywords “rural tourism” and “sustainability” were searched in the Google Scholar database (TM et al., 2021). The keywords from the 100 most relevant results, based on Google Scholar’s default sorting algorithm, were analyzed. This step added “sustainable rural tourism,“ “village tourism,“ “socially responsible,” and “green” to the initial keyword list. Third, the new set of keywords was searched within the most authoritative journals in tourism as assessed by their presence in the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) and Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) journal ranking guides. The final set of keywords was: sustain*, rural tourism, village tourism, sustainable rural tourism, socially responsible, green, Albergo Diffuso, environment friendly, eco-friendly, and responsible. They were validated by a panel of experts from research, practice, and policy.

3.2. Identification and screening of literature

The search using the final set of keywords yielded a total of 753 results from Web of Science and 762 results from Scopus. These databases have been popular among SLR studies related to the tourism sector (Kristjánsdóttir et al., Citation2018; Pahlevan-Sharif et al., Citation2019). A strict set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was used to gauge the relevance of the studies (Carter et al. 2015; Xu et al., Citation2020) and is presented in . We excluded reviews, conference proceedings, non-peer-reviewed literature, and books during the search stage. Next, the title and abstract of each research article were examined to gauge relevance and exclude non-relevant articles. This step resulted in a total of 211 articles. Finally, after reading the full text of the remaining articles, those not meeting the inclusion criteria were removed. This resulted in the final sample of 100 research studies in the review.

4. Research profile: RT sustainability – an emerging area of research

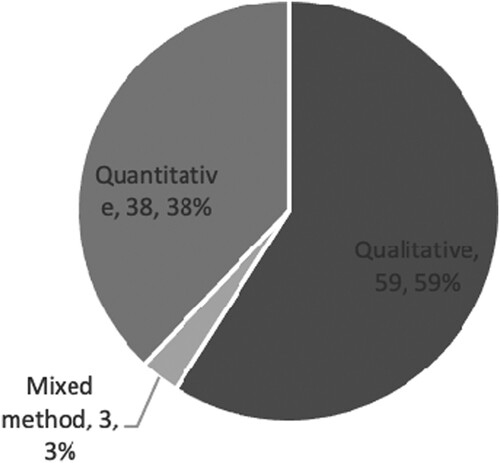

The most frequent publishing outlets included in this sample are Sustainability and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism (). This is a somewhat disheartening find as it suggests that no leading tourism and hospitality journals are among most productive journals on this topic. Further, though prior studies indicate a major trend of RT-related work in European countries (Madanaguli, Kaur, Bresciani, & Dhir, Citation2021), geography-restricted journals like the Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism do not feature in this list, either. The research in this domain appears to be increasing exponentially, with about 50% of the total research published between 2019 and 2022, which highlights the timeliness of this review. The dip in research output during 2021 and 2022 can perhaps be attributed to COVID-19, which brought the tourism sector to a virtual standstill during the earlier stages of the pandemic (Gössling, Scott, & Hall, Citation2020). The majority of selected studies adopted a qualitative approach (), and the most popular method of inquiry was case study research. Cross-sectional studies are the most prominent among quantitative studies, and Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) is the most frequently used analytical method. There are no longitudinal studies in the sample.

Table 1. Top outlets for RT sustainability research.

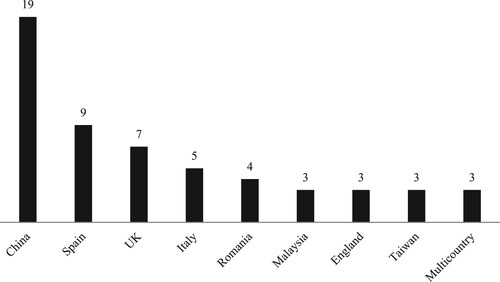

China emerged as the most studied country with 19 studies (). This may be attributed to the new strong policy interventions advocated by China for the development of RT (Gao et al., Citation2019). However, Europe emerged as the most studied continent in RT due to its historic encouragement of RT (Augustyn, Citation1998; Quaranta et al., Citation2016; Turnock, Citation1999). The geographical distribution of studies indicates that other countries and regions may benefit from policy initiatives to help develop rural tourism.

5. Qualitative content analysis

Each of the studies was read and independently coded in open and axial rounds by the authors. The codes were then compared and refined to arrive at the final list of themes (Stanfill, Williams, Fenton, Jenders, & Hersh Citation2010). The analysis revealed four major themes of research: (i) definition and dimensions of RT sustainability, (ii) stakeholders in RT sustainability, (iii) drivers and barriers of RT sustainability, and (iv) benefits and consequences of sustainable RT planning and implementation.

5.1. Definition and dimensions of RT sustainability

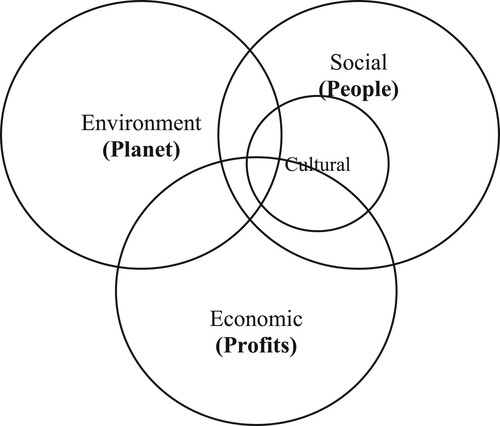

The triple bottom line model (Elkington, Citation2013) states that firms should balance their businesses in such a way that they balance their profits (economic), and the rights and well-being of society and people around them (social), in addition to the environment and planet conservation (environmental). These goals are often called the three pillars of sustainability (Elkington, Citation2013). Besides these three components, some studies also discuss cultural sustainability as a major component of RT sustainability (Fong et al., Citation2017; Garau, Citation2015; Randelli & Martellozzo, Citation2019). Cultural sustainability ensures the survival of the culture of the region during the course of sustainable tourism development.

Prior research indicates that households in rural tourism destinations modify their activities to create both tangible and intangible cultural tourism “products” to achieve their livelihood goals. A good example is the conversion of old rural homes in China to heritage hotel accommodations due to increased demand (Ma et al., Citation2021). Although this is may be good thing for rural development, it may also pose the threat of cultural deterioration. As Ma et al. (Citation2021) also point out, this demand has led to an increase in illegal constructions. The triple bottom line model has therefore been redrawn to incorporate cultural sustainability, as presented in . However, considering that cultural sustainability still concerns the preservation of the social fabric, many studies do not make the distinction (Briedenhann Citation2009; Garau, Citation2015).

While many studies discuss the trade-off between these components of sustainability (Kallmuenzer & Peters, Citation2018), other studies report that businesses do not have to sacrifice one component of sustainability in order to preserve on another, as they can make use of local synergies and innovative business practices to simultaneously pursue sustainability without endangering profits (Ayvaz & Cetin, Citation2019; Lordkipanidze et al., Citation2005). Thus, an economically, socially, culturally, and environmentally sustainable RT may generate profit while also creating social value (Smith et al., Citation2019), enhancing tourist value (Chin et al., Citation2018), preserving local culture from corruption (Cahyanto et al., Citation2013; Garau, Citation2015), conserving local environments and resources (Cucari et al., Citation2019; Liu & Ko, Citation2014), and supplementing the income of locals (He, Gao, et al. Citation2021; He, Wang, et al. Citation2021)

5.2. Stakeholders in RT sustainability

Stakeholders have been at the centre of most sustainability models, including the triple bottom line model (Elkington, Citation2013). Stakeholder theory states that businesses are responsible for creating value for all stakeholders, and not just shareholders (Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar, & De Colle, Citation2010). Consequently, any discussion about sustainability cannot be considered complete without discussing the roles of various stakeholders in sustainability initiatives. A stakeholder is defined as a person, group, or organization that holds an interest in a particular organization or initiative (Freeman et al. 2010).

RT sustainability is a multi-stakeholder initiative. Each stakeholder’s actions or inactions have an impact on the sustainability of RT, and so successfully navigating stakeholders’ diverse and perhaps competing needs is a difficult task (Mcareavey & Mcdonagh, Citation2011). Further, it is also important to consider the trade-offs required to satisfy each of the stakeholders in relation to the other stakeholders (Sun et al., Citation2021). The content analysis in this study identified seven key stakeholders: community members, RT entrepreneurs, tourists, policymakers, NGOs, researchers, and other stakeholders. The driving and barrier roles of each of the above stakeholders are discussed in the next research theme.

5.3. Drivers and barriers of RT sustainability

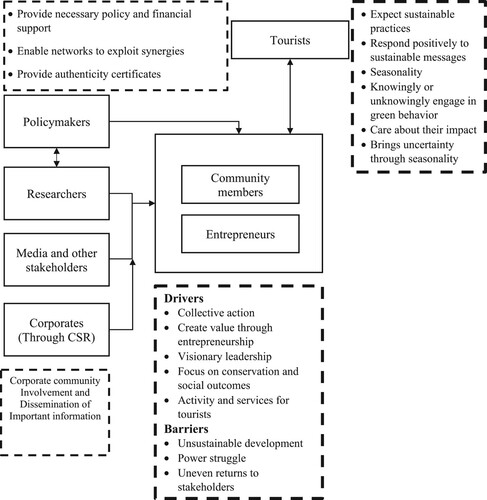

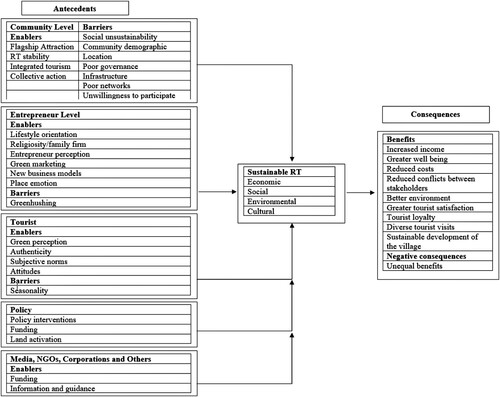

The reviewed literature notes several drivers and barriers of RT sustainability. The drivers and barriers may be classified at four levels: (a) community level, (b) entrepreneur level, (c) tourist level, and (d) others levels, which may include policymakers, NGOs, and researchers, based on the stakeholders involved in enabling or hindering the sustainability process. presents an overview of stakeholders and their roles in RT sustainability.

5.3.1. Community-level

5.3.1.1. Community participation

Community participation and support is essential in developing sustainable RT (Lane, Citation1994), and 29 of the reviewed articles discuss the relationship between community and RT sustainability. A community may be defined as a set of people leading similar work-lives in a geographical area (Brehm et al., Citation2004). Prior research indicates that communities have a significant influence on rural tourist experience and revisit intention (Lo et al., Citation2019). This significance comes from the lack of public services in rural areas, where community entrepreneurs may be the only providers of accommodation, transportation, or activities to visiting tourists (Lo et al., Citation2019). This implies that tourists must regularly interact with the local community, shaping their perception, satisfaction, and expenditure in the area (Spencer & Nsiah, Citation2013). How a community provides for tourists is therefore essential in bringing about tourism-related economic sustainability.

5.3.1.2. Collective action

In this context, collective action occurs when all participants in a rural area come together to participate in sustainability initiatives (Schweinsberg et al., Citation2012). Collective action leads to tourism development at the community level that is more likely to be sustainable. This is called community-based tourism (CBT) and involves interactions between the community and outside developers and companies (Gabriel-Campos et al., Citation2021; Hwang et al., Citation2012; Merkel Arias & Kieffer, Citation2022; Priatmoko et al., Citation2021). Through a case study of five scenarios, Hwang et al. (Citation2012) show that sustainable tourism development is often met with resistance at first, but through community meetings and interactions, stakeholders become aware of the personal investments they already have in RT and come to view the development more positively. Furthermore, an existing and economically viable RT system is conducive to sustainable transformation (Guaita Martínez et al., Citation2019).

Collective action is impacted by group-level variables such as trust, group size (Schmidt et al., Citation2016), age, and gender of group members (Muresan et al., Citation2016). Policy and supporting agencies also play a key role in organizing collective action in a community (Barbieri et al., Citation2020; Gao et al., Citation2019). This will be discussed further in the section on the role of policymakers. Unique community-level art has also been found to positively influence collective action and community-based tourism (Chatkaewnapanon & Kelly, Citation2019). In addition, research, particularly participative action research, can also have a positive impact on collective action by helping to create platforms that allow all stakeholders to meet and discuss their roles (Merkel Arias & Kieffer, Citation2022). This, however, is not an easy process and requires active effort to engage and gather internal stakeholders together with external stakeholders and partners (Mwesiumo et al., Citation2022).

The religious values of a community may also play an important role in local attitudes towards collective action and sustainability; Islamic religiosity in particular has been found to positively influence sustainable behaviour (Aman et al., Citation2019). This may manifest as “hiding” some sacred spots from tourists or dedicating separate times to tend to religious activities and tourism (Cahyanto et al., Citation2013). Both of these studies were conducted in Muslim countries, and similar studies on other religious communities were not contained in the selected sample of studies.

Despite its benefits, collective action has a few drawbacks. It is prone to free-riding behaviour (Schmidt et al., Citation2016), and may occasionally lead to collective “inaction” wherein locals believe resource exploitation to outweigh any benefits of RT and so limit their participation in it (Ghaderi & Henderson, Citation2012). This unwillingness comes from a difference in belief about the proper balance of the environmental and economic components of sustainability, and similar attitudes have also observed by Ateş and Ateş (Citation2019), Šimková (Citation2007), and Guaita Martínez et al. (Citation2019). Other barriers to the implementation of RT through CBT include lack of planning (Garau, Citation2015), weak governance (Garau, Citation2015; Wanner & Pröbstl-Haider, Citation2019), group homogeneity (Schmidt et al., Citation2016), perceived community costs (Zhu et al., Citation2017), and management and network inefficiency (Barbieri et al., Citation2020).

5.3.2. Entrepreneur level

Successful RT entrepreneurs often act as “visionary” leaders in the development of RT in a region (Brooker & Joppe, Citation2014). Armed with their prior knowledge of running successful ventures, they may act as catalyst for change in a rural society (Moscardo, Citation2014). The same trend is observed in the adoption of sustainability practices. For instance, Ferrari et al. (Citation2010) classify rural entrepreneurs into “environmentally conscious,” “ecopreneurs,” and “environmentally reactive.” Ecopreneurs are active entrepreneurs who take steps to reduce both their own and tourists’ impact on the local environment and society while simultaneously increasing their economic output. Such entrepreneurs have also been known to creatively message tourists about adopting green practices (Wang et al., Citation2018). Such practices targeted at environmental sustainability also impact economic sustainability by reducing waste and cost while increasing income and occupancy. Entrepreneurs and local communities may build a symbiotic relationship wherein entrepreneurs promote community action to create sustainable value for the community, themselves, and tourists (Schmidt et al., Citation2016).

Considering the importance of entrepreneurship, prior studies have addressed the impact of entrepreneurial environment and policy support on sustainable RT (Lordkipanidze et al., Citation2005). Through detailed SWOT analysis, studies have shown that there are incredible opportunities for sustainable RT, but that lack of entrepreneurial support, collaboration, policy, and financial support stifles progress (Lordkipanidze et al., Citation2005). However, established entrepreneurs can contribute to all three pillars of sustainability by providing jobs and increasing community income, conservation, and similar initiatives (Turnock, Citation1999). Results from similar SWOT-based studies concur with these findings. Some important weaknesses and threats they add are lack of supporting bodies (Ateş & Ateş, Citation2019), lack of awareness, unsustainable building of infrastructure, lack of waste management infrastructure (Ristić et al., Citation2019), lack of use of technology (Sanagustín Fons et al., Citation2011), lack of standards and research, and lack of indigenous involvement in development (Augustyn, Citation1998).

Prior evidence indicates that some manner of visionary leadership is essential to ensure the success of CBT, yet certain research has suggested that entrepreneurs lack the capabilities needed to convert resources into sustainable value for tourists (Widawski & Oleśniewicz, Citation2019). In those cases, leadership must be looked for elsewhere, and certain studies have focused on the role of other forms of leadership in promoting CBT. For instance, Priatmoko et al. (Citation2021), studying Indonesian RT initiatives, show that a proactive village head can be the necessary visionary, even without entrepreneurial experience.

5.3.3. Tourist level

Tourists play an important role in RT sustainability. On the economic sustainability front, destination loyalty and revisit intention has been the most studied concept. Several antecedents to destination loyalty have been studied in the literature, including tourist safety, food and beverages, affordable pricing, and factors like spirituality (Long & Nguyen, Citation2018). Further, tourists also prefer to visit locations with particular services, offer well-being (Ryglová et al., Citation2018), developed infrastructure, special events, activities, and active community support (Lo et al., Citation2019).

On the environmental sustainability front, it has been noted that tourists respond positively to green marketing initiatives and tend to prefer eco-labeled, -branded, and -advertised products (Chin et al., Citation2018). They also respond favourably to creative warnings about waste generation and resource conservation (Wang et al., Citation2018), leading to the creation of a social system that encourages eco-friendly choices and deters wastefulness. The system seems to make the stay more enjoyable for tourists and also increases occupancy.

Other studies have noted the role of tourist perception of sustainability in RT as an important predictor of revisit intention (Ryglová et al., Citation2018) and destination loyalty (Campón-Cerro et al., Citation2017). In some cases, tourists may even actively engage in local cultural and environmental conservation (Kastenholz et al., Citation2018). However, in a contradictory finding, Font, Elgammal, and Lamond (Citation2017) show that UK RT tourist businesses often underrepresent their greening initiatives or engage in “greenhushing” to avoid scaring away tourists with complex or heavy-handed messages of sustainability.

Although tourists are often considered significant enablers of sustainability, they may also hinder it (Martín et al., Citation2017). In addition to being a direct cause for environmental degradation, tourists can also contribute to economic unsustainability by participating in the seasonal nature of tourism (Martín Martín et al., Citation2020). Due to this seasonality, the RT industry in a region is sometimes unable to provide regular employment to the community (Lee et al., Citation2021), and Su et al. (Citation2019) observed that families engaged in RT earned roughly half of their average on-season income during off-seasons. However, these constraints are usually experienced by RT destinations in the growth phase; established destinations generally do not suffer from seasonality (María Martín-Martín, Ostos-Rey, & Salinas-Fernández, Citation2019). Considering the wide variety in RT destinations and types, it is unclear if seasonality is a function of the region. For instance, Che et al. (Citation2021) investigated satisfaction among tourists in Mongolia and observed that tourist satisfaction and intention to revisit a destination are impacted by the season during which the tourists visit. More such studies are needed to capture dimensions such as satisfaction and sustainability.

Another important facet of sustainability among RT destinations is the question of demand and overuse. Overtourism is a major issue which is seen as a disruptor of both environmental and social sustainability (Majdak & de Almeida, Citation2022). Ghaderi, Hall, and Ryan (Citation2022) reports a similar case in Iran where rural residents questioned the validity of RT as a sustainable livelihood option, as it was having an adverse impact on villages. A concentrated policy effort is thus needed to control overtourism and its adverse effects, such as Bhutan’s $200 per night tourism tax, intended to limit tourist traffic (Mayling, Citation2022). However, virtually no studies to date have investigated the impact of such decisions on tourist satisfaction. Other themes of research include the impact of tourists’ personal characteristics, like attitude, on the intention to visit (Grubor et al., Citation2019) and best practices for communicating authentic initiatives for sustainability (Aronsson, Citation1994; Widawski & Oleśniewicz, Citation2019).

5.3.4. Other stakeholders

Policymakers play a significant role in enabling RT sustainability, particularly economic and social sustainability (Polukhina et al., Citation2021). Turnock (Citation1999) notes in his study of Romanian RT development that policy coordination between local developmental agencies and the government in the late 1980s resulted in considerable RT growth in Romania. This growth later helped alleviate poverty and increase employment in rural Romania. Similar initiatives include employment generation policies in Romania (Turnock, Citation1999), the Polish National Strategy for Rural Tourism Development (Augustyn, Citation1998), tourism development policy in fragile areas of China (Liu, Citation2020), policies aimed at increasing connectivity in Italy (Quaranta et al., Citation2016), and others (Bramwell, Citation1991). The presence of a strong environmental policy may also further promote environmental conservation.

The enabling role of a well-crafted sustainable RT policy for land consolidation and activation is also seen in other countries, such as China (Gao et al., Citation2019). Funding by the public sector also plays a crucial role in the process (Baker 2005; Sharpley, Citation2007). The results of other similar studies indicate that integrated policy intervention is essential to permit a truly sustainable RT initiative in a region (Bramwell, Citation1991; Lane, Citation1994).

Furthermore, as highlighted by several studies, poor governance and ad-hoc planning are deterrents to sustainable CBT (Garau, Citation2015; Quaranta et al., Citation2016; Schmidt et al., Citation2016). Böcher (Citation2008, p. 385) notes that “regional cooperation still needs an incentive from outside.” Policymakers and local governments act as a bridge in such situations to enable cooperation at national and local levels (Mcareavey & Mcdonagh, Citation2011). For example, in their study of Chinese firms, Gao et al. (Citation2019) show that the Ministry of Agriculture and their “Beautiful Village” initiative were responsible for accomplishing land consolidation and activation for the purpose of value creation. Such large-scale tasks are often difficult for small communities to accomplish themselves.

Another significant stakeholder is the RT researcher, who contributes to the discussion of sustainability by studying RT sustainability initiatives. The highlight of such contributions to the field is the empirically tested and detailed scales developed to quantify sustainability in RT. A full comparison of the scales used in such studies is not presented here, but may be found in Park and Yoon (Citation2011), Briedenhann (Citation2009), Marzo-Navarro et al. (Citation2015), and Lee and Hsieh (Citation2016). These tested indicators can enable RT managers and policymakers to gauge the sustainability strategies and policies implemented by them.

Other stakeholders also include corporations and media organizations. Yang et al. (Citation2019) report that a corporation’s CSR initiative can act as a catalyst for sustainable rural tourism in a region, which may be considered as an alternative to policy support. Unfortunately, no further studies on the topic were included in the sample. Similarly, the role of media as stakeholders – the dissemination of valuable information to other community stakeholders – was also discussed by a single study (Ponnan, Citation2013).

Other important issues studied in the prior literature include community members’ self-efficacy (Fong et al., Citation2017), the impact of flagship attractions (Sharpley, Citation2007), financing (Sharpley, Citation2007; Turnock, Citation1999), community resources and capabilities (Artal-Tur et al., Citation2019; Mwesiumo et al., Citation2022), strong locational identity through models like Albergo Diffuso (Cucari et al., Citation2019), valorization (Ducros, Citation2017), and effective land use (Gao et al., Citation2019).

5.4. Benefits and consequences of sustainable RT planning and implementation

The reviewed literature explores a set of direct benefits associated with sustainable RT, and has also considered how responsible RT can lead to greater sustainability (Ćurčić et al., Citation2021). Overwhelmingly, studies agree that RT businesses that adopt sustainable practices have a major impact on ensuring the sustainable development of rural areas (Coroș et al., Citation2021; Degarege & Lovelock, Citation2021; He, Wang, et al. Citation2021; Ibanescu et al., Citation2018; Nair et al., Citation2015; Ristić et al., Citation2019). For instance, He, Gao, et al. (Citation2021) investigate the impact of sustainable RT in rural China and find that sustainable RT plays a positive role in community development. In a related study from Transylvania, Gica et al. (Citation2020) show that sustainable RT can have an impact on sustainable development goals (SDG) set by the United Nations. Particularly, sustainable RT can impact SDG 1, 8, 10, 11, 12, and 17. Beyond these, sustainable RT also has several other benefits, as listed below.

5.4.1. New business models

Moving away from destructive industries like forestry is often an antecedent of RT (Schweinsberg et al., Citation2012). It enables RT businesses to explore and innovate new tourist inventions, a good example being the Dark Sky Reserve in Portugal that enables tourists to view the unadulterated night sky (Rodrigues et al., Citation2015). This initiative has further contributed to social and economic sustainability by educating locals about light pollution and reducing energy costs.

5.4.2. Increased footfall and tourist satisfaction

Adopting a sustainable strategy also increases a region’s destination attractiveness (Guizzardi et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2018). Adopting RT sustainability leads to increased tourist loyalty (Campón-Cerro et al., Citation2017) and tourist footfall (Rodrigues et al., Citation2015). These studies indicate that tourists may reward a sustainable location by visiting it more often, but it must not be forgotten that seasonality and overwhelm may lead to social unsustainability because of the inability of RT firms to consistently make positive returns (Briedenhann Citation2009).

5.4.3. Negative consequences

Residents of rural tourism communities often gain by supporting RT, but unequal development due to power struggles could be an issue (Cottrell et al., Citation2007). Additionally, if certain stakeholders are ignored in the planning process, this can lead to unsustainable practices (Wanner et al., Citation2021). Residents may also lose their investments if the initiative does not create a return (Ghoddousi et al., Citation2018). Issues arising from the seasonality of demand can worsen this problem. During off-seasons, a RT community may find its tourism-related income decreased to half of its normal on-season income (Su et al., Citation2019). In addition, some studies note that engaging in RT can lead to loss of cultural identity and so make the rural area unattractive to tourists in the long run (Randelli & Martellozzo, Citation2019). A study from China even shows that expansion of tourist demand can lead to illegal construction activities in the pursuit of creating tourism products and services (Ma et al., Citation2021). These studies highlight the difficulties in balancing the economic aspect of RT sustainability with other aspects.

6. Gaps and avenues for future research

Our content analysis of the published works in this field reveals that RT sustainability has received a great deal of attention in the last decade, particularly with regard to the roles of its different stakeholders and its benefits and consequences. Overall, though, each domain of sustainability has received increasing attention. Nonetheless, the review process identified several gaps that may be addressed by future researchers to provide relevant managerial and policy implications. Below are five suggestions for future research in this area, guided by relevant research questions.

6.1. Suggestion 1: the ecosystem of RT and sustainability

Suggestion 1 relates to theme 2: stakeholders in RT sustainability and theme 3: drivers and barriers of RT sustainability. The review captures the role of seven stakeholders, mainly. However, the majority of research interest has been on four key stakeholders - tourists, entrepreneurs, community residents, and policymakers. The attention paid to stakeholders like corporations, media, RT researchers, and non-governmental supporting agencies has been limited. Further, prior studies have made little mention of stakeholders like RT employees, think-tanks, courts, suppliers, investors, and trade unions. Future research would do well to address the role of these stakeholders in sustainability efforts and investigate their interaction with other stakeholders. In this regard, we suggest the following research questions:

RQ1.1: What are the interactions between stakeholders that enable or disable RT sustainability initiatives?

RQ1.2: What other stakeholders exist in ensuring RT sustainability, and what are their roles?

In addition, the existing research has done little to trace the evolution of RT policy. Policies are usually trial-and-error initiatives that change over time due to stakeholder feedback. It is necessary to track the evolution process in order to suggest policy implementation timelines in new regions. Therefore, we suggest the following research question.

RQ1.3: How does policy related to RT sustainability evolve?

6.2. Suggestion 2: the role of entrepreneur and RT firm characteristics on sustainability efforts

The role of entrepreneurs has been discussed in detail in theme 3: drivers and barriers, but the role of individual characteristics of entrepreneurs seeking sustainable RT requires more attention. RT and sustainability literature can gain insights from entrepreneurship and small business literature and direct further enquiries in this stream of literature along those lines. One theoretical perspective that may be of use is the entrepreneurial orientation model (Covin & Slevin, Citation1989), which states that an entrepreneur’s orientation is dictated by three parameters: proactiveness, innovativeness, and risk-taking. For example, it has been found that encouraging tourists to adopt green practices requires significant innovativeness (Wang et al., Citation2018). However, no other such studies were included in the sample, perhaps indicating that this is not a common track of investigation. Further, an entrepreneur’s actions are impacted by other trait variables like self-efficacy and confidence. This line of research can also use the existing typology of sustainable entrepreneurship proposed by Ferrari et al. (Citation2010). Thus, future research may address the following questions:

RQ2.1: What is the role of entrepreneurial orientation in implementing sustainability measures in a RT business?

RQ2.2: What are the entrepreneurial characteristics that may be encouraged to promote sustainable RT?

Another entrepreneurial characteristic of concern is the gender of the entrepreneur. Prior research indicates that women are more concerned about environmental sustainability than men (Galbreath, Citation2019), as has been found in rural and agri-tourism contexts as well (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020). Further, research has also observed that women were more motivated to pursue agri-tourism than were men, thus hinting at a possibility that women entrepreneurs may be key in achieving sustainable RT. It would therefore be interesting to answer the following question:

RQ2.3: Are women entrepreneurs better at introducing environmental sustainability initiatives in RT?

This line of inquiry can be best led by the perspective of the eco-feminist theory (Buil-Fabregà et al., Citation2017) and is likely to concur with similar studies in other areas. The results may encourage more women to participate in RT and promote social sustainability in rural regions.

Extending this premise, we see that family-run RT enterprises are more likely to achieve the trade-off balance required to sustain their environments without sacrificing undue profits (Kallmuenzer et al., Citation2018), and are also likely to strive for non-financial goals (Zellweger et al., Citation2013). Similar results are also observed in religious communities in Muslim countries (Aman et al., Citation2019), where religious values have been linked to conservation efforts (Park, Citation2003). However, it is unknown if these values vary among religions. Following the questions of family-run businesses and religious values, we pose the following research questions:

RQ2.4: Are family-owned RT businesses more environmentally and socially conscious than non-family businesses?

RQ2.5: If so, what are the strategies they use to compete with non-family RT businesses that may not be as concerned with conservation and sustainability?

RQ2.6: What is the role of religiosity in sustainability among different religions? For instance, are RT enterprises in primarily Christian, Hindu, or Buddhist regions more sustainable than those in regions without a dominant belief system, or with a different dominant belief?

6.3. Suggestion 3: methodological consideration

The methodologies adopted in the sampled studies indicate that the qualitative case-based method is the most prominent method, and only three studies adopted a mixed-method approach. Though the case study method provides results with high validity and often high reliability, it is often criticized for providing non-generalizable results (Hamel et al., Citation1993). Generalizable results are necessary for the guiding of effective policy at national levels. Further, there were no longitudinal quantitative studies in the sample. Therefore, future studies may take up the following:

RQ3.1: Are the results of existing qualitative studies from particular regions generalizable to some extent?

RQ3.2: If so, what are the moderating and mediating variables that may impact RT sustainability?

The review included research based on detailed SWOT studies, which may be of interest in this endeavour (Ateş & Ateş, Citation2019; Augustyn, Citation1998; Lordkipanidze et al., Citation2005; Ristić et al., Citation2019; Sanagustín Fons et al., Citation2011). It is interesting to note that although each of these studies has been conducted in a different geographical and cultural context, the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats identified within appear almost universal. Thus, to some extent, issues concerning RT and sustainability may be more generalizable than they at first appear. We propose that future researcher consider the strengths and weaknesses in these models as antecedents in their own, in which RT sustainability is treated as the study variable. Various opportunities and threats may act as moderators to the relationship. Further, it would be interesting to investigate the availability of measures for each parameter. If such measures are not available, this opens up research potential in scale development.

A more even distribution of research across geographies may also hold promise for future research. Our descriptive analysis revealed that the research in our sample was divided almost equally between Asian and European countries, with China as the single most represented country (16 studies). Among our sample, only four articles reported multi-country comparative studies (Petrović et al., Citation2018). Cross-cultural studies inspired by institutional (North, Citation1991) and cultural (Hofstede & Hofstede, Citation2005) theories hold promise for learning from different contexts. The agreement and disagreement of results between regions would greatly help advance theory development in the area. To this end, we propose the following research question:

RQ3.3: What factors are responsible for divergence of results between regions?

6.4. Suggestion 4: creating shared value

The discussion of innovative business models in theme 4: benefits and consequences of RT innovation indicated that it is possible to create economic value while simultaneously improving the social and environmental pillars of sustainability. This discussion tends to lead to the concept of creation of “shared value.” In their landmark article, Porter and Kramer (Citation2011) argue that it is possible to move beyond the traditional sustainability trade-off model and pursue all three goals simultaneously using creative business models.

However, although certain studies indirectly addressed the concept, there appears to be a dearth of studies exclusively using this theoretical standpoint to better elucidate the processes and supports required to create shared value. Therefore, future research may address this question:

RQ4.1: What are the drivers of and barriers to creating sustainable shared value in RT tourism?

6.5. Suggestion 5: impact of COVID-19

COVID-19 is currently wreaking havoc on the international tourism system (Gössling et al., Citation2017). It has made crowded destinations unattractive to visit, and many popular tourist destinations worldwide are shutting down or reducing occupancy in local attractions to stop or slow the spread of COVID-19 (Connexion journalist, Citation2020). It is speculated that tourists now prefer destinations that are less crowded and less impacted by COVID-19, as they wish to maintain the new social distancing norms and so hopefully remain uninfected. However, it is unclear if the existing RT infrastructure can handle the volatility of post-lockdown tourism. While a sudden influx of tourists may have a positive impact on the economic sustainability of a region, it is also likely to negatively impact the environmental, social, and cultural aspects of sustainability should it exceed the carrying capacity of that region (Stronza & Gordillo, Citation2008). Further, it is unclear if rural areas have adequate health infrastructure and supplies needed to keep the local population safe from potential COVID infections spread by tourists. Thus, it is pertinent to ask:

RQ5.1: Are existing rural systems and processes adequate to handle the volatility of post-lockdown tourism?

RQ5.3: If not, how can the local RT systems adapt in order to ensure the sustainable use of social and environmental resources?

RQ5.4: What is each stakeholder’s role in ensuring the sustainability of rural areas during this crisis?

RQ5.5: What are the policy interventions required to handle the change in tourist visits?

Further, studies may also examine the impact of increased occupancy and income on the well-being of the local community by asking:

RQ5.6: What are the social and economic impacts of increased tourist visits to rural areas?

7. Research framework

The results of our review show that there exists an ecosystem of stakeholders and their interactions which determines sustainability in RT. In other words, several stakeholders interact in a myriad of different ways and act as enablers of or barriers to sustainability while deriving benefits from sustainability measures. Thus, we propose a “RT sustainability ecosystem” framework to summarize the findings of our research.

To do so, we adopt an “antecedents and consequences framework” (Johnstone et al., Citation2001; Madupu & Cooley, Citation2010). The framework has been visualized in below. It consists mainly of three parts: (1) the antecedents of the phenomenon of interest, (2) the nature of the phenomenon of interest, and (3) the outcomes or consequences of the phenomenon of interest. In our case, the phenomenon of interest is sustainability in RT. This framework represents the culmination of our analysis wherein we summarize our findings. The components are discussed below in detail.

7.1. Antecedents of RT sustainability

The antecedents of RT sustainability have been broadly classified as enablers and barriers, and for each antecedent we have identified a stakeholder who takes responsibility for it. The stakeholders are: (1) communities, (2) entrepreneurs, (3) tourists, (4) policymakers, (5) NGOs, (6) researchers, and (7) corporations, media, and others. Although the roles of most of these stakeholders have been discussed, stakeholders such as communities, entrepreneurs, tourists, and policymakers have received much more research attention in prior literature than the others, resulting in rather imbalanced knowledge of how these stakeholders impact sustainability. As a result, more research attention should be paid to the other stakeholder groups.

7.2. The nature of RT sustainability

Literature on RT has been vocal about the three pillars of sustainability: economic, social, and environmental. However, having reviewed a sample of this literature, we find that the RT context is also interested in another factor, namely cultural sustainability (Fong et al., Citation2017; Garau, Citation2015; Randelli & Martellozzo, Citation2019). The importance of culture in a rural area can be linked to the concept of rurality (Sharpley, Citation2007). The cultural identity of a location gives a rural area its uniqueness and thus makes it a tourist location worth visiting. Future research would do well to consider this additional component when discussing sustainability.

In addition, our results find that RT businesses seek a balanced trade-off between these components in order to ensure sustainability, or even seek to transcend them and so simultaneously pursue economic and sustainable goals through innovative efforts (Ayvaz & Cetin, Citation2019; Lordkipanidze et al., Citation2005). Thus, we suggest shared value creation (Porter and Kramer Citation2011) as the theoretical underpinning for any future research that explores this phenomenon.

7.3. Outcomes of RT sustainability

Just as are the antecedents, the outcomes of sustainability initiatives are also associated with multiple stakeholders. The results of our review indicate that implementing sustainable measures not only helps the community, but also helps customers and RT businesses. However, as with the antecedents, these outcomes have been disproportionately researched from the perspective of the three stakeholder groups discussed above. More studies are needed to investigate what other stakeholders may gain or lose by supporting sustainability in RT.

8. Implications and conclusion

8.1 Study implications

This review presents several academic and practical implications. First, although the issues of sustainability have received widespread attention in RT literature, there has not yet been any attempt to catalogue and classify the body of literature. With sustainability taking centre stage in business discussions, a literature review on RT and sustainability is timely and well placed. Thus, this study contributes to the growing body of reviews that have addressed sustainability issues in tourism (Alfaro Navarro et al., Citation2020; Bramwell, Higham, Lane, & Miller, Citation2017; Xu et al., Citation2020; Zhang & Zhang, Citation2020).

Second, the review addresses the role of stakeholders in the RT sustainability process. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the first reviews to do so. Thus, the review also presents interesting implications for the stakeholders of RT by calling attention to the importance of collective action facilitated by policy and reviewing the role of entrepreneurs. Policymakers may use this knowledge to identify and reach out to communities with the potential to successfully set up collective action for RT development. The review also adds to the general discussion on using sustainable RT to achieve sustainable development goals in rural areas.

Studies from multiple regions show that tourists respond positively to sustainable messaging and eco-branding (Wang et al., Citation2018). This holds implications for RT entrepreneurs who may be unsure of implementing these measures in their businesses. Further, the review shows that the entrepreneur’s role is central to identifying and creating new value in rural areas seeking to develop RT. Communities and policymakers will have more success in this endeavour when they come together to identify visionary entrepreneurs who can lead the change towards sustainability.

8.2 Limitations, scope for future research and concluding remarks

Though care has been taken to ensure a comprehensive review of the extant literature, the review has some limitations. First, we used stringent inclusion-exclusion criteria during the screening process in order to establish clear boundaries to research. This ensured that only high-quality peer-reviewed literature was identified and reviewed, but led to the exclusion of grey literature and non-peer-reviewed works, including blogs, newspaper articles, books, book chapters, and conference proceedings. Furthermore, articles in languages other than English were also removed. It is possible that the excluded articles contained relevant findings and insights, but we considered this possibility an acceptable trade-off to ensure the high validity of this review. Future research may examine grey literature in the area to augment the summarization of the themes presented in this work.

Second, to restrict the scope of our review to RT and sustainability, research articles on farm-based diversification were not included in the search. Certain farm-based diversification may lead to RT enterprises, but this review does not capture the role of farm-based entrepreneurs. Farm sustainability and farm-based tourism sustainability is therefore another area where future researchers can carry out similar literature reviews. Future research can also examine sustainability issues in other tourism areas such as heritage, indigenous, and mountain tourism.

The objective of this study is to present a comprehensive review of RT and sustainability. The results of the review indicate that RT sustainability is a growing area of research that holds much potential for future research. We paid special attention to explicating the dimensions of sustainability and stressed the importance of cultural sustainability when studying RT and sustainability. The research themes highlight various stakeholders, their roles, and interactions in ensuring sustainable RT. A brief description of the benefits and consequences of sustainable RT adoption is also presented. We conclude by presenting a RT sustainability framework to summarize our findings, and believe this review to provide a strong foundation future research in the area.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alfaro Navarro, J. L., Andrés Martínez, M. E., & Mondéjar Jiménez, J. A. (2020). An approach to measuring sustainable tourism at the local level in Europe. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(4), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1579174

- Aman, J., Abbas, J., Mahmood, S., Nurunnabi, M., & Bano, S. (2019). The influence of islamic religiosity on the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development in Pakistan: A structural equation modeling approach. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(11), 3039. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113039

- Ardoin, N. M., Wheaton, M., Bowers, A. W., Hunt, C. A., & Durham, W. H. (2015). Nature-based tourism’s impact on environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behavior: A review and analysis of the literature and potential future research. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(6), 838–858. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1024258.

- Aronsson, L. (1994). Sustainable tourism systems: The example of sustainable rural tourism in Sweden. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2(1–2), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589409510685

- Artal-Tur, A., Briones-Peñalver, A. J., Bernal-Conesa, J. A., & Martínez-Salgado, O. (2019). Rural community tourism and sustainable advantages in Nicaragua. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(6), 2232–2252. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2018-0429

- Ateş, HÇ, & Ateş, Y. (2019). Geotourism and rural tourism synergy for sustainable development—marçik valley case—tunceli, Turkey. Geoheritage, 11(1), 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-018-0312-1

- Augustyn, M. (1998). National strategies for rural tourism development and sustainability: The Polish experience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 6(3), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589808667311

- Ayvaz, S., & Cetin, S. C. (2019). Witness of things: Blockchain-based distributed decision record-keeping system for autonomous vehicles. International Journal of Intelligent Unmanned Systems, 7(2), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIUS-05-2018-0011

- Barbieri, C., Sotomayor, S., & Gil Arroyo, C. (2020). Sustainable tourism practices in indigenous communities: The case of the Peruvian Andes. Tourism Planning and Development, 17(2), 207–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1597760

- Bertocchi, D., Camatti, N., Giove, S., & van der Borg, J. (2020). Venice and overtourism: Simulating sustainable development scenarios through a tourism carrying capacity model. Sustainability (Switzerland).

- Böcher, M. (2008). Regional governance and rural development in Germany: The implementation of LEADER+. Sociologia Ruralis.

- Botella-Carrubi, D., Currás Móstoles, R., & Escrivá-Beltrán, M. (2019). Penyagolosa trails: From ancestral roads to sustainable ultra-trail race, between spirituality, nature, and sports. A case of study. Sustainability, 11(23), 6605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236605

- Bramwell, B. (1991). Sustainability and rural tourism policy in Britain. Tourism Recreation Research, 16(2), 49–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.1991.11014626

- Bramwell, B., Higham, J., Lane, B., & Miller, G. (2017). Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism: Looking back and moving forward. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 1–9.

- Brehm, J. M., Eisenhauer, B. W., & Krannich, R. S. (2004). Dimensions of community attachment and their relationship to well-being in the amenity-rich rural west. Rural Sociology.

- Briedenhann, J. (2009). Socio-cultural criteria for the evaluation of rural tourism projects-a Delphi consultation. Current Issues in Tourism, 12(4), 379–396.

- Brooker, E., & Joppe, M. (2014). Entrepreneurial approaches to rural tourism in The Netherlands: Distinct differences. Tourism Planning & Development, 11(3), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2014.889743

- Buckley, R. (2012). Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Annals of Tourism Research.

- Buil-Fabregà, M., Alonso-Almeida, M. d. M., & Bagur-Femenías, L. (2017). Individual dynamic managerial capabilities: Influence over environmental and social commitment under a gender perspective. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.081

- Byrd, E. T. (2007). Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: Applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tourism Review, 62(2), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605370780000309

- Cahyanto, I., Pennington-Gray, L., & Thapa, B. (2013). Tourist-resident interfaces: Using reflexive photography to develop responsible rural tourism in Indonesia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(5), 732–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.709860

- Campón-Cerro, A. M., Hernández-Mogollón, J. M., & Alves, H. (2017). Sustainable improvement of competitiveness in rural tourism destinations: The quest for tourist loyalty in Spain. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 6(3), 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.04.005

- Chatkaewnapanon, Y., & Kelly, J. M. (2019). Community arts as an inclusive methodology for sustainable tourism development. Journal of Place Management and Development, 12(3), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-09-2017-0094

- Che, C., Koo, B., Wang, J., Ariza-Montes, A., Vega-Muñoz, A., & Han, H. (2021). Promoting rural tourism in Inner Mongolia: Attributes, satisfaction, and behaviors among sustainable tourists. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3788. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073788.

- Chin, C. H., Chin, C. L., & Wong, W. P. M. (2018). The implementation of green marketing tools in rural tourism: The readiness of tourists? Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 27(3), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2017.1359723

- Connexion journalist. (2020). COVID-19: France tourism boost as travel rules eased. The Connexion. https://www.connexionfrance.com/French-news/Covid-19-France-tourism-boost-as-100km-travel-limit-lifted-and-hotels-allowed-to-reopen

- Coroș, M. M., Privitera, D., Păunescu, L. M., Nedelcu, A., Lupu, C., & Ganușceac, A. (2021). Mărginimea sibiului tells its story: Sustainability, cultural heritage and rural tourism—a supply-side perspective. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(9), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095309

- Cottrell, S. P., Vaske, J. J., Shen, F., & Ritter, P. (2007). Resident perceptions of sustainable tourism in Chongdugou, China. Society and Natural Resources, 20(6), 511–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920701337986

- Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100107

- Cucari, N., Wankowicz, E., & Esposito De Falco, S. (2019). Rural tourism and Albergo Diffuso: A case study for sustainable land-use planning. Land Use Policy, 82(May 2018), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.050

- Ćurčić, N., Svitlica, A. M., Brankov, J., Bjeljac, Ž, Pavlović, S., & Jandžiković, B. (2021). The role of rural tourism in strengthening the sustainability of rural areas: The case of zlakusa village. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(12), 6747. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126747

- Danese, P., Manfè, V., & Romano, P. (2018). A systematic literature review on recent lean research: State-of-the-art and future directions. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(2), 579–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12156

- Degarege, G. A., & Lovelock, B. (2021). Addressing zero-hunger through tourism? Food security outcomes from two tourism destinations in rural Ethiopia. Tourism Management Perspectives, 39(September 2020), Article 100842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100842

- Ducros, H. B. (2017). Confronting sustainable development in two rural heritage valorization models. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(3), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1206552

- Elkington, J. (1998). Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environmental Quality Management, 8(1), 37–51.

- Elkington, J. (2013). Enter the triple bottom line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does it All Add Up.

- Ferrari, G., Mondéjar-Jiménez, J., & Vargas-Vargas, M. (2010). Environmental sustainable management of small rural tourist enterprises. International Journal of Environmental Research, 4(3), 407–414. https://doi.org/10.22059/ijer.2010.4

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., de Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2020). Gender, tourism & entrepreneurship: A critical review. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, Article 102980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102980

- Fong, S. F., Lo, M. C., Songan, P., & Nair, V. (2017). Self-efficacy and sustainable rural tourism development: Local communities’ perspectives from Kuching, Sarawak. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(2), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2016.1208668

- Font, X., Elgammal, I., & Lamond, I. (2017). Greenhushing: The deliberate under communicating of sustainability practices by tourism businesses. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(7), 1007–1023. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1158829

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Chicago.

- Gabriel-Campos, E., Werner-Masters, K., Cordova-Buiza, F., & Paucar-Caceres, A. (2021). Community eco-tourism in rural Peru: Resilience and adaptive capacities to the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 48(August), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.07.016

- Galbreath, J. (2019). Drivers of green innovations: The impact of export intensity, women leaders, and absorptive capacity. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3715-z

- Gao, C., Cheng, L., Iqbal, J., & Cheng, D. (2019). An integrated rural development mode based on a tourism-oriented approach: Exploring the beautiful village project in China. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(14), 3890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143890

- Garau, C. (2015). Perspectives on cultural and sustainable rural tourism in a smart region: The case study of Marmilla in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability (Switzerland), 7(6), 6412–6434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7066412

- Ghaderi, Z., Hall, M. C. M., & Ryan, C. (2022). Overtourism, residents and Iranian rural villages: Voices from a developing country. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 37, 100487.

- Ghaderi, Z., & Henderson, J. C. (2012). Sustainable rural tourism in Iran: A perspective from Hawraman Village. Tourism Management Perspectives, 2–3, 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2012.03.001

- Ghoddousi, S., Pintassilgo, P., Mendes, J., Ghoddousi, A., & Sequeira, B. (2018). Tourism and nature conservation: A case study in Golestan National Park, Iran. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26(December 2017), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.12.006

- Gica, O. A., Coros, M. M., Moisescu, O. I., & Yallop, A. C. (2020). Transformative rural tourism strategies as tools for sustainable development in Transylvania, Romania: a case study of Sâncraiu. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 13(1), 124–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-08-2020-0088

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of sustainable tourism, 29(1), 1–20.

- Grubor, A., Milicevic, N., & Djokic, N. (2019). Social-psychological determinants of Serbian tourists’ choice of green rural hotels. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(23), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236691

- Guaita Martínez, J. M., Martín Martín, J. M., Salinas Fernández, J. A., & Mogorrón-Guerrero, H. (2019). An analysis of the stability of rural tourism as a desired condition for sustainable tourism. Journal of Business Research, 100(March), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.033

- Guizzardi, A., Stacchini, A., & Costa, M. (2022). Can sustainability drive tourism development in small rural areas? Evidences from the Adriatic. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(6), 1280–1300. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1931256

- Hamel, J., Dufour, S., & Fortin, D. (1993). Case study methods (Vol. 32). SAGE Publications.

- He, Y., Gao, X., Wu, R., Wang, Y., & Choi, B. R. (2021). How does sustainable rural tourism cause rural community development? Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(24), 13516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413516.

- He, Y., Wang, J., Gao, X., Wang, Y., & Choi, B. R. (2021). Rural tourism: Does it matter for sustainable farmers’ income? Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(18), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810440

- Hjalager, A.-M. (2014). Who controls tourism innovation policy? The case of rural tourism. Tourism Analysis, 19(4), 401–412. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354214X14090817030955

- Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures in organizations. Cultures Consequences, 373–421. Sage Publishing.

- Hwang, D., Stewart, W. P., & Ko, D. w. (2012). Community behavior and sustainable rural tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3), 328–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511410350

- Ibanescu, B. C., Stoleriu, O. M., Munteanu, A., & Iaţu, C. (2018). The impact of tourism on sustainable development of rural areas: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(10), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103529

- Johnstone, K. M., Warfield, T. D., & Sutton, M. H. (2001). Antecedents and consequences of independence risk: Framework for analysis. Accounting Horizons, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2001.15.1.1

- Kallmuenzer, A., Nikolakis, W., Peters, M., & Zanon, J. (2018). Trade-offs between dimensions of sustainability: Exploratory evidence from family firms in rural tourism regions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(7), 1204–1221. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1374962

- Kallmuenzer, A., & Peters, M. (2018). Entrepreneurial behaviour, firm size and financial performance: The case of rural tourism family firms. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2017.1357782

- Kaptan Ayhan, Ç, Cengi̇z Taşlı, T., Özkök, F., & Tatlı, H. (2020). Land use suitability analysis of rural tourism activities: Yenice, Turkey. Tourism Management, 76, 103949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.07.003

- Kastenholz, E., Eusébio, C., & Carneiro, M. J. (2018). Segmenting the rural tourist market by sustainable travel behaviour: Insights from village visitors in Portugal. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 10(November 2017), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.09.001

- Kristjánsdóttir, K. R., Ólafsdóttir, R., & Ragnarsdóttir, K. V. (2018). Reviewing integrated sustainability indicators for tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(4), 583–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1364741

- Lane, B. (1994). Sustainable rural tourism strategies: A tool for development and conservation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2(1–2), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589409510687

- Lee, S., Kim, D., Park, S., & Lee, W. (2021). A study on the strategic decision making used in the revitalization of fishing village tourism: Using A’WOT analysis. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(13), 7472. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137472

- Lee, T. H., & Hsieh, H. P. (2016). Indicators of sustainable tourism: A case study from a Taiwan’s wetland. Ecological Indicators, 67, 779–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.03.023

- Liu, L. W., & Ko, P. Y. (2014). Conservational exploitation as a sustainable development strategy for a small township: The example of waipu district in Taichung, Taiwan. Journal of Urban Management, 3(1–2), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2226-5856(18)30085-2

- Liu, R. (2020). The state-led tourism development in Beijing’s ecologically fragile periphery: Peasants’ response and challenges. Habitat International, 96(2), 102119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102119

- Lo, M. C., Chin, C. H., & Law, F. Y. (2019). Tourists’ perspectives on hard and soft services toward rural tourism destination competitiveness: Community support as a moderator. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 19(2), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358417715677

- Long, N. T., & Nguyen, T. L. (2018). Sustainable development of rural tourism in an Giang Province, Vietnam. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040953

- Lordkipanidze, M., Brezet, H., & Backman, M. (2005). The entrepreneurship factor in sustainable tourism development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 13(8), 787–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2004.02.043

- Ma, X., Wang, R., Dai, M., & Ou, Y. (2021). The influence of culture on the sustainable livelihoods of households in rural tourism destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(8), 1235–1252. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1826497

- Madanaguli, A., Kaur, P., Mazzoleni, A., & Dhir, A. (2022). The innovation ecosystem in rural tourism and hospitality-a systematic review of innovation in rural tourism. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(7), 1732–1762.

- Madanaguli, A. T., Kaur, P., Bresciani, S., & Dhir, A. (2021). Entrepreneurship in rural hospitality and tourism. A systematic literature review of past achievements and future promises. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(8), 2521–2558. doi/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2020-1121

- Madupu, V., & Cooley, D. O. (2010). Antecedents and consequences of online brand community participation: A conceptual framework. Journal of Internet Commerce, 9(2), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2010.503850

- Majdak, P., & de Almeida, A. M. M. (2022). Pre-Emptively managing overtourism by promoting rural tourism in Low-density areas: Lessons from Madeira. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020757

- María Martín-Martín, J., Ostos-Rey, M. S., & Salinas-Fernández, J. A. (2019). Why regulation is needed in emerging markets in the tourism sector. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 78(1), 225–254.

- Martín, J. M. M., Fernández, J. A. S., Martín, J. A. R., & de Dios Jiménez Aguilera, J. (2017). Assessment of the tourism’s potential as a sustainable development instrument in terms of annual stability: Application to Spanish rural destinations in process of consolidation. Sustainability (Switzerland), 9(10), 1692. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101692

- Martín Martín, J. M., Salinas Fernández, J. A., Rodríguez Martín, J. A., & Ostos Rey, M. d. S. (2020). Analysis of tourism seasonality as a factor limiting the sustainable development of rural areas. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 44(1), 45–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348019876688

- Marzo-Navarro, M., Pedraja-Iglesias, M., & Vinzón, L. (2015). Sustainability indicators of rural tourism from the perspective of the residents. Tourism Geographies, 17(4), 586–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2015.1062909

- Mayling, S. (2022, July 31). Bhutan to charge US$200-a-night tourism tax. Connecting Travel. https://www.connectingtravel.com/news/bhutan-to-charge-200-a-night-tourism-tax.

- Mcareavey, R., & Mcdonagh, J. (2011). Sustainable rural tourism: Lessons for rural development. Sociologia Ruralis, 51(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2010.00529.x

- Merkel Arias, N., & Kieffer, M. (2022). Participatory action research for the assessment of community-based rural tourism: A case study of co-construction of tourism sustainability indicators in Mexico. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2022.2037526

- Mikhaylova, A. A., Wendt, J. A., Hvaley, D. V., Bógdał-Brzezińska, A., & Mikhaylov, A. S. (2022). Impact of cross-border tourism on the sustainable development of rural areas in the Russian-Polish and Russian-Kazakh borderlands. Sustainability, 14(4), 2409.

- Moscardo, G. (2014). Tourism and community leadership in rural regions: Linking mobility, entrepreneurship, tourism development and community well-being. Tourism Planning & Development, 11(3), 354–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2014.890129

- Muresan, I. C., Oroian, C. F., Harun, R., Arion, F. H., Porutiu, A., Chiciudean, G. O., et al. (2016). Local residents’ attitude toward sustainable rural tourism development. Sustainability (Switzerland), 8(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010100

- Mwesiumo, D., Halfdanarson, J., & Shlopak, M. (2022). Navigating the early stages of a large sustainability-oriented rural tourism development project: Lessons from Træna, Norway. Tourism Management, 89(April 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104456

- Nair, V., Hussain, K., Lo, M. C., & Ragavan, N. A. (2015). Benchmarking innovations and new practices in rural tourism development: How do we develop a more sustainable and responsible rural tourism in Asia? Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 7(5), 530–534. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-06-2015-0030

- North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.97

- Pahlevan-Sharif, S., Mura, P., & Wijesinghe, S. N. R. (2019). A systematic review of systematic reviews in tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 39, 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.04.001