ABSTRACT

Despite generalised global recommendations, local communities are rarely involved in defining strategic tourism development options. Similarly, methodologies to facilitate these processes of co-creation have not been adequately implemented, tested, and generalised. This study aims to contribute to this body of knowledge by assessing the potential of a participatory planning method centred on the strategic diversification of tourism products. Focusing on the Swedish island of Gotland, where tourism dynamics partly depend on the visits to the Hanseatic town of Visby by cruise ships, a workshop based on an Open Space Methodology (OSM) was implemented, involving local entrepreneurs, representatives of organisations, students, and international researchers in tourism (an original contribution). The results revealed that these “coopetition” processes can contribute to identifying problems and determining possible solutions. In our case, these options can be framed within the concept of “penetration” (modifications and increasing promotion of existing products to the existing markets) involving aspects related to physical and digital infrastructures, along with partnerships and collaborations amongst stakeholders. Overall, this study reveals that the interaction between members and non-members of the local community appears crucial for the emergence of innovative ideas.

Introduction

Many tourist destinations worldwide have recognised problems related to tourist concentration, as exemplified by Albaladejo and González-Martínez (Citation2018) for the case of Spain, by Du Cros and Kong (Citation2020) for Macau City, and also by policy-oriented organisations, such as the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD, Citation2020), with a more general perspective. The need to promote a spatial and temporal dispersion of tourists, ultimately by developing diverse and alternative product offerings – a process of product diversification with different strategic options, as formulated by Benur and Bramwell (Citation2015) – appears to be a viable solution in all the instances. This may reduce the problems associated with a large number of visitors staying in a small geographical area simultaneously, causing substantial stress on infrastructures, buildings, and personnel.

Alternatively, by spreading the economic benefits of tourism through the territory, the local tourism industry can also promote a more sustainable development. Many cases exit where local resources can be exploited to create these offers. Thus, utilising these resources – along with already existing products and services – to diversify the tourism supply and facilitate the spatial diffusion of tourists can be beneficial. Local stakeholders must therefore be involved in tourism product developments.

Involving local stakeholders and communities in the discussion and definition of strategic tourism development is highly effective (Fyall, Garrod, & Wang, Citation2012; Hall, Citation2019; UNWTO, Citation2007). This topic has long been a subject of a systematic research and critical analysis, as exemplified by Dredge (Citation2006), Beaumont and Dredge (Citation2010), or – with diverse examples in the context of the emergence of the so-called “collaborative economy”, which is strongly supported by digital networks – by Dredge and Gyimóthy (Citation2018). However, methodologies to facilitate and enhance these co-creation processes must be further developed and intensified. Particularly, how the involvement of local communities and their ongoing initiatives can help to create a thematic and spatially diversified tourism supply by innovating and/or developing existing activities with the consequent dissemination of tourists in time and space remains limitedly understood.

Different methods for driving business development processes related to tourism development and involving different stakeholder categories have been identified (Åberg & Svels, Citation2018; Grauslund & Hammershøy, Citation2021; Thomas, Citation2013; Timur & Getz, Citation2009). Several studies exist on collaboration and co-creation at tourism destinations (e.g. Qiu, Chen, Yang, Zhang, & Liu, Citation2022; Wondirad, et al., Citation2020; McComb, Boyd, & Boluk, Citation2017; Perkins, Khoo-Lattimore, & Arcodia, Citation2020). However, the Open Space Methodology (OSM) has not been studied as a tool for co-creating local sustainable tourism strategies. Therefore, how OSM can work in the tourism business development context must be explored. When comparing four different participatory methods, Vacik et al. (Citation2014) concluded that OSM was the best option for solving complex problems overall. However, their study was not conducted in a tourism development context, which is related to other development processes that can be pertinent to the tourism industry.

This study focuses on the Swedish island of Gotland, where the majority of visitors tend to congregate in Visby City, primarily due to the importance of Baltic Sea cruise tourists (Baldacchino, Citation2015; Marcussen, Citation2017). Through a participatory workshop based on OSM involving a combination of local stakeholders, local tourism students, and international researchers, this study aims to understand how OSM can be used to develop tourism diversification. Thus, the research question is: how can OSM, as an example of participatory action research, be used to develop tourism diversification involving essential stakeholders in a local business ecosystem?

The study sheds light on the research question from three perspectives:

Relevance of the topics raised in the OSM workshop and the subsequent proposals, which can be consistently synthetised in the creation of collaborative thematic routes.

The effects of OSM in the ongoing development context and collaborative practices.

Whether the OSM workshop generates proposals for diversified integration of tourism products and services.

Conceptual framework

The approach is based on two theoretical concepts: the idea of integrative product diversification (Benur & Bramwell, Citation2015) as a strategic option for thematic and spatial diversification of tourism products and services, anchored and integrated into the existing supply and OSM as a method commonly used for involving local communities (Farinosi et al., Citation2019; Palsson & Singh, Citation2018; Salvatore, Chiodo, & Fantini, Citation2018).

Integrative product diversification

The “time budget” concept proposed by Pearce (Citation1988) was later used by Lew and McKercher (Citation2006) when modelling the spatial patterns of tourists’ mobility within a destination. The amount of available time a tourist has at a destination severely limits the range of options for consuming local services, amenities, and experiences. Thus, a spatial diversification of tourism activities by cruise tourists must consider the strict limits of this “time budget”. Tourists who perceive transit time as a cost to be avoided to focus on the enjoyment of a specific activity or service (as defined by McKean, Johnson, & Walsh, Citation1995) may prefer to allocate their “time budget” to visit the medieval town’s historical centre. Meanwhile, tourists who value their time may appreciate the opportunity to observe the island's beautiful scenery whilst visiting other locations associated with rural life, ecological sites, or cultural heritage (Chavas, Stoll, & Sellar, Citation1989). Essentially, a longer duration of the visit enhances the spatial diversification of the visit.

The existence of a significant market on the island presents a major opportunity to implement a strategy to create new products that encourage the spatial diversification of visitors. In addition, as critical aspects for the implementation of such a strategy, UNWTO and ETC (Citation2011) suggested identifying relevant resources and attributes, evaluating factors, production, and potential investment, and developing a comprehensive approach for involving relevant stakeholders within the local tourism system. Moreover, given the fragmented character of tourism supply, product development must consider the need for coordination between public institutions and private companies (Song, Liu, & Chen, Citation2013; Yılmaz & Bititci, Citation2006). In the context of Gotland island, the existing resources and services are identified, and its integration into the dynamics of cruise tourists remains a challenge requiring a collaborative approach from local tourism stakeholders.

The approach to tourism product diversification proposed and systematised by Benur and Bramwell (Citation2015) appears particularly applicable where the current situation corresponds to concentrated mass tourism, with many tourists attracted by a single product (the medieval walled city of Visby). Although tourists are motivated by the same main attraction, their motivations for secondary activities may vary. Thus, diversification must be viewed as “integrative” (rather than parallel) once the primary market segment and reason for the visit have been identified, implying that potential secondary products must be anchored and related to the primary product.

To develop such a process, the strategic options must consider the features of the territory and the characteristics of demand, along with the interactive processes between them. This co-creative process should strengthen and intensify the relationships and interactions with other tourism products and services, potentially resulting in an increase in destination attractiveness, greater satisfaction with local experiences, more significant impacts on regional sustainable development, and a decrease in the pressure and crowding effects within the walled city of Visby.

Such a strategic approach can be implemented in Gotland by combining different products (thematic synergies) in various locations (spatial synergies), assuming cultural urban tourism related to the World Heritage Site of Visby as the core product, whereas other attractions on the island may be seen as alternative products. Thus, aspects related to the thematic development of tourism experiences, or the implementation of routes may be particularly relevant (UNWTO and ETC, Citation2017). Our analysis also contributes to studies on the utilisation of natural (Margaryan & Fredman, Citation2017) and rural (Gössling & Mattsson, Citation2002) resources for Sweden’s tourism development.

Tourism Product Development is defined by UNWTO (Citation2011) as “a process whereby the assets of a particular destination are moulded to meet the needs of national and international customers” including products and services for visitors to see and do, whilst assuming a fragmented supply, involving independent companies, individuals, or organisations. This long-term process requires coordination amongst stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of the needs and demands of consumers and the necessary investments. This coordinated effort for creating products and services on the basis of existing territorial resources, considering concrete market opportunities, may lead to four different strategic approaches, according to Ansoff (Citation1987).

These four alternatives are defined as follows: market penetration (small modifications and increasing promotion of existing products, eventually combined, to existing markets); product development (creation of innovative products and services for existing markets); market development (repositioning of existing products, eventually combined to target new markets); and diversification (creation of innovative products and services for new markets). As they are geared towards the exploitation of an existing market, the proposals resulting from the workshop conducted as part of this research can be conceptualised in terms of “market penetration” and “product development”. Here, the product development process involves interactions between urban and rural areas, posing new challenges for innovation in Swedish rural tourism (Hjalager, Kwiatkowski, & Østervig Larsen, Citation2018).

Typically, a successful process of diversified integration is predicated on the joint promotion of multiple products, capitalising on the product that is already well established on the market. Thus, information and transportation are spatially distributed across the Gotland island and emerge as crucial factors for effective integration. Due to the constraints imposed by the limited “time budgets” of cruise tourists, efficient transportation services must be developed and implemented to ensure their access to various attractions.

However, this poses a major challenge for the thematic and spatial diversification of the island’s tourism. Another critical challenge is the timely distribution of reliable information to support cruise visitors’ trip choices. Nonetheless, before arriving at Gotland, various options can be considered (online platforms, brochures about the cruise in travel agencies or brochures available inside the cruise boats on the way to Visby). When arriving at the port of Visby, visitors must be able to select from a variety of options and have the means of transportation necessary to reach the desired attractions. In this context, the definition of thematic routes combining different local products (UNWTO and ETC, Citation2017) may emerge as a relevant strategic solution, so long as it can combine the development of new experiences for niche market segments (thematic approach) with the design of routes with highly predictable and organised mobility solutions that ensure the experience can be enjoyed within the available “time-budget”.

The achievement of effective solutions for creating spatially distributed packages of diverse products, implementation of the required transportation services, and creation of efficient information channels and communication processes requires a significant effort of coordination involving various local stakeholders in a “coopetition” (Della Corte and Aria, Citation2016) process of “co-creation” (Binkhorst & Dekker, Citation2009). Despite the fact that these local providers will compete to attract visitors to their own services, they must create a common promotional and commercial infrastructure that makes the entire island appealing to short-term visitors.

Thus, the creation and/or reinforcement of the local social capital and community ties amongst stakeholders operating in the tourism system appears as a precondition for the implementation of a strategy of diversified integration to reinforce the contribution of tourism for the sustainable development of the Gotland island. Thus, the main concerns of the experimental participatory workshop are: identifying ideas for the creation of tourism packages for cruise tourists combining their visit to Visby with other attractions in Gotland; and reinforcing the local social capital by strengthening the ties and co-operative processes amongst local stakeholders.

Open space methodology

Patton et al. (Citation2016) pointed out that OSM can be explained as a learning and consultation methodology involving all the participants. Further, Nauheimer and Ilieva (Citation2005) elucidated that the methodology supports multi-stakeholder processes in problem identification and collaborative learning. The reasoning is in accordance with Herman and Jain (Citation2006) and Alford (Citation2008) who argue that the features of OSM allow stakeholders to identify needs and propose suggestions. These needs can either be to explore new solutions, that is, drive innovation processes, which can be done as business development or social or public innovation processes, (e.g. Aksoy, Alkire (née Nasr), Choi, Kim, & Zhang, Citation2019; Emmendoerfer et al., Citation2020) or be of a problem-solving nature, that is, the need to develop existing products and processes, which March (Citation1991) claimed as exploitation. OSM can be viewed as a method for generating opportunities to balance and simultaneously deal with exploration and exploitation, a capability known as the “ambidextrous development process” that Juran (Citation1964), one of the leading figures of the quality movement, deemed essential for quality enhancement. Scholars have followed up on Juran's ideas by demonstrating that the most effective teams are those that can multitask explorative development with incremental development, or have high ambidexterity (Gilson, Mathieu, Shalley, & Ruddy, Citation2005). Likewise, March (Citation1991) and Gibson and Birkinshaw (Citation2004) stated that one key factor affecting a business’ long-term success is its ability to exploit its current capabilities whilst exploring fundamentally new areas.

The OSM was developed by Harrison Owen in the 1980s and was called Open Space Technology (OST). Here, we have described OST as OSM. The central tenet of OpenStreetMap is its commitment to inclusivity, which enables participants to construct their own agendas effectively, allowing anyone interested in an issue to have their voice heard regardless of their status (Alford, Citation2008; O’Connor & Cooper, Citation2005). According to Kotler, Bowen, Makens, and Baloglu (Citation2017), the characteristics of OSM align with the five characteristics of a successful collaboration process: Stakeholders are autonomous; solutions emerge from constructively addressing differences; decisions are jointly owned; stakeholders assume collective responsibility for the domain's ongoing direction; collaboration is an emergent process.

One characteristic that distinguishes OSM from other workshop processes is that the participants themselves set the agenda for what they wish to discuss and then choose amongst the various proposed topics (Nauheimer, Citation2005; Owen, Citation2008). However, the process must begin with a clear headline so that participants are aware of the thematic framework to which they must adhere. Additionally, the workshop must be constructed with a clear purpose so that the participants know what they are expected to achieve by contributing to the discussions (White, Citation2002). Holmen (Citation2015) pointed out that OSM forces the development process to focus on what is perceived as emergent in the context the method is used. When the agenda for an open space workshop is determined by the participants, the focus is on emergent issues, which creates better opportunities for a self-organising development process to take place, thereby facilitating the transition from ideation to action.

In their systematic comparative analysis of different forms of collaborative planning methods, Vacik et al. (Citation2014) defined three major types of problems potentially addressed by these methodologies: problem identification (definition of problems, resources, goals, management alternatives, conflicts or interactions); problem modelling (relations between management options, interests of stakeholder groups and policy scenarios); and problem solving (design of management plans determining the implementation process). Vacik et al.’s (Citation2014) three types of problems are relevant in the current context as challenges may be at any of these levels, and the continuous local development process must clarify the type of challenges raised. Whether the results of the workshop are new problems, a model of an existing problem, or suggestions for problem-solving, they have an impact on subsequent processes.

Further, Vacik et al. (Citation2014) stated that OSM is one of the 43 methods they analysed, which has the best ability to contribute to “problem solving”. This distinguishes the OSM from several other methods attempting to effectuate idea generation to real solutions, that is, implementation, which may rarely succeed (e.g. Klein & Sorra, Citation1996).

Method

Case study

Gotland is a major Baltic Sea tourist destination. The island has a long history of receiving domestic tourists from the Swedish mainland, who come primarily for the sun and the beaches. As a Hanseatic town, Visby was designated a World Heritage Site in 1995. Currently, as Gotland is mainly aiming to increase the number of international tourists, the cultural heritage is promoted as one of the main reasons for visit. In recent years, the number of tourists has decreased primarily because the harbour could not accommodate larger ships. Subsequently, in April 2018, a new cruise pier was inaugurated, resulting in a sharp increase in the number of international cruise tourists who visit Visby primarily for its cultural heritage. According to data from Region Gotland, approximately 100,000 cruise passengers visited Gotland in 2019, with the number expected to increase in the years to come. As we now know, the pandemic then struck, and in 2020 there were very few cruise visitors (only 20,000), but by 2021 that number had risen to 120,000 and by 2022 it had reached 150,000.

However, new challenges emerge despite the achievements. As cruise passengers only spend a few hours at the destination, they are unable to travel great distances and therefore remain close to the ship, within the walled city of Visby, causing congestion.

Context in which the OSM workshop was carried out

Gotland has a long history as a destination and of efforts to manage and develop the destination, such as a well-developed tourist organisation within a Swedish context. Additionally, Gotland has a history of complex collaborations in tourism development; a large number of distinct organisations and development bodies, as well as their high turnover, make long-term planning and implementation difficult.

With the plan to build a new cruise quay, new attempts at organising and planning transpired, and the “Gotland Cruise Network” was created. During fieldwork, one of the authors of this article closely monitored the activities of this network. Members of the network represented the local community, including large and small public and private actors from Visby City, surrounding countryside, NGOs, and other citizen representations. Various activities were conducted via meetings, presentations, seminars, workshops, and other business development processes.

OSM should be understood in the context listed below. This was not the first time a workshop to develop cruise tourism in Gotland had been organised, and many stakeholders were likely sceptical about the need for yet another one, causing some to abstain. These considerations were taken into account when organising the workshop. To inject “new blood” into the discussions, we invited international scholars and students from the local campus to the workshop. In addition, the OSM had never been tested before, and because it is based on the concept of allowing participants to define what they wish to discuss, it differed from other methodologies previously attempted. Therefore, we wanted to explore whether this format can generate new discussions and ideas.

Participatory action research

Participatory Action Research (PAR) supports participants in the research process to solve their own problems (Stringer, Citation2014; Reason & Bradbury, Citation2013). Further, Chevalier and Buckles (Citation2013) stated that action research today is included as an “important method in professional business development and often includes interdisciplinary dialogue” (p. 1). Those perspectives are particularly important and relevant in the PAR initiative underlying this article. The choice of PAR has hence been perceived as suitable. The Dialogical Organization Development (DOD), formulated by Bushe and Marshak (Citation2015, p. 11), which is the underlying mindset behind OSM, has also stressed that researchers and conductors of OSM workshops can highly benefit from working with PAR to contribute to real development through dialogue-based development processes.

However, PAR is not an exact method but can be seen as a “family of approaches” (Reason & Bradbury, Citation2013, p. 7). “Action” can mean that collaboration between researchers and actors outside the academy results in increased action for the stakeholder outside the academy; it can also mean that the researchers take an active role and thus refer to their role in the studied phenomena. The latter definition applies to this article. Here, the workshop followed the OSM approach that potentially contributes to community development, whilst generating empirical data supporting academic research.

The workshop was led by three experienced workshop process leaders. Two of whom are authors of this article, whereas the third author was a participant in the workshop and a current member of the organising committee of an international conference held in Visby. The selection of PAR is influenced by Stringer (Citation2014), who asserted that PAR may violate conventional research methods given that it does not split the relationship between the researcher and the researched objects in a conventional manner. Another reason is that PAR has a more democratic structure with a humanistic approach and assists participants in the research process in gaining a deeper understanding of the research topic and their own circumstances.

Workshop, participants, and data collection

In September 2019, the workshop was held in Visby, focusing on how the tourism industry in Gotland can create and develop attractive offers for cruise tourists visiting the Island. The workshop was one of the final events held on Gotland as part of a research project that aimed to examine (1) the attitudes of cruise tourists towards Gotland as a tourist destination, and (2) how they navigated around the island during their visit to (2) use the generated data with a PAR approach to support the development of the local tourism industry. This research project called “Sustainable visits between the map and visitor experience” was carried out by Uppsala University. The project continued from March 2018 to February 2020. The workshop was also carried out as the final event of an international conference on tourism and sustainable development held in Visby and promoted by Uppsala University and the cluster on tourism, leisure, and recreation of Network on European Communications and Transport Activities Research (NECTAR).

The OSM workshop involved 37 participants comprising 14 entrepreneurs and representatives of public organisations in Gotland, 13 international researchers attending the conference, and 10 students from the Master's Programme in Sustainable Destination Development at Uppsala University, Campus Gotland. The announcement for complimentary workshop for tourism operators was made three weeks in advance. The announcement was made through digital banners on the websites of the two largest local media outlets. A registration link was provided in the announcement. An invitation was also sent out to participants within the Gotland Cruise Network, the Master's Programme in Sustainable Destination Development, and in the academic conference.

The workshop using OSM was conducted for 3 h. The participants in the workshop identified the perspectives they wanted to discuss. Thereafter, groups were voluntarily formed to discuss the topics, that is, each participant can join any of the groups. Moreover, the participants can also transfer to a different group during the discussion (with the exception of the person in charge of reporting the results for each group). After an hour, the main identified topics of each group were presented to all the participants. At that stage, new topics were raised; some topics were slightly reformulated, including discussions on how specific topics could have been merged (which did not happen). Thereafter, a second round of discussions started, following the same simple principles and methodologies, leading to new identified problems, modelling of existing problems and new ideas about how new, attractive offers outside Visby for cruise tourists visiting the island can be developed. The main method for continuing with the newly gained knowledge and insights was the participants’ memories and notes from the workshop. By allowing each participant to select a task from the workshop, ownership and favourable conditions were created for individuals to act in self-organising units and carry out the development process. Each of the local businesses participating in the workshop would be able to concentrate on these pressing issues.

Results and analysis

The research question posed in this article is addressed from three angles. First, a presentation and analysis of the topics raised at the OSM workshop, with contributions and proposals organised into the categories of problem identification, problem modelling, and problem solving, leading to a synthesis expressed through the creation of thematic routes. Second, the effects of OSM on the ongoing tourism development context, particularly on the consolidation of collaborative practices amongst local stakeholders. Third, an analysis of whether the OSM workshop can contribute to the diversified integration of tourism products and services.

Topics raised in the OSM workshop

The results generated in the workshop have been systematised according to the typology of problems proposed by Vacik et al. (Citation2014): problem identification, problem modelling, and problem solving. This systematisation is presented in , which organises and categorises the topics raised during the workshop. By following this methodological framework, the plethora of proposals collected and discussed in the workshop can be organised in a manner that facilitates subsequent levels of discussion and decision making.

Table 1. Topics and comments raised in the OSM workshop carried out in Visby in September 2019. The comments are sorted in accordance with the typology of problems proposed by Vacik et al. (Citation2014).

Effects of OSM on the ongoing tourism development context

As stated previously, the conditions for increased collaborations on Gotland may have appeared advantageous, yet challenging, which may be partly owed to “path-dependent” historical social relationships between people. The island is a small tight community, where relationships as well as conflicts span generations, which are difficult to avoid. Moreover, “external” actors, who can potentially overcome the problem, faced difficulties in receiving acceptance. This may be due in part to a mutual misunderstanding between the public and private sectors regarding the terms of each other's work. The private sector mistrusts the public sector and believes it does not provide the necessary conditions, resources, and circumstances for companies to act. The public sector believes it has no obligation to fulfil the needs of the private sector and is bound by strict rules and regulations that the private sector does not consider. The relationship between local and external companies visiting Gotland solely for cruise tourism operations has also been a source of tension. One example was when a company from the mainland, rather than a Gotland company, was commissioned to run the shuttle traffic between the cruise ship and the town centre, a decision made by the multinational company that operates the cruise quay. In this context, the OSM can be described as creating an environment for participants’ active participation, which resulted in spontaneous discussions on a wide range of topics.

Analysing the results of the workshop in the context of Gotland's ongoing processes, the attempts to develop cruise tourism offers, and the complicated history of planning and collaboration, this workshop generated topics and issues that had not been discussed at previous meetings and workshops. The workshop's questions and discussions also contributed to the modelling of many previously identified problems and difficulties. OSM succeeded in generating new perspectives alongside new solutions to long identified needs and conflict causing factors. However, some discussions in terms of “modelling” the problems (relationships between options, scenarios, and conflicting interests) were relatively superficial: frequently because there was no conflict (e.g. there was a general consensus regarding the benefits of spatial diversification of tourism on the island) and occasionally because the different interests were not evident (e.g. between the management of international digital platforms and local business).

OSM succeeded in contributing to a solution-oriented idea generation and an expectant climate of co-operation for the continued generation of new solutions to old conflicts, although the limitations of the workshop are clear when looking at the “problem-solving” type of contributions. The plethora of proposals collected had clear strategic orientations. They require a further process of concretisation to discuss priorities, to articulate the available resources (and related constraints), and the actions necessary to execute the identified and proposed general ideas or strategic options. Thus, although the workshop can serve as a step in the right direction, it does not lead to a complete solution; additional steps are necessary, and it will likely be essential to determine who amongst the diverse actors in Gotland has the authority and credibility to lead such a process.

Whether the OSM workshop generates proposals for the diversified integration of tourism products and services

One key topic discussed during the workshop was the need for, and potential solutions for, diversifying the local tourism supply related to heritage tourism in Visby's walled city. The majority of the proposals presented at the workshop related to what March (Citation1991) defined as exploitation and “penetration” according to Ansoff's typology for product development: small modifications and increasing promotion of existing products (eventually combined) to the existing markets. This includes the combination of high-quality local products from Gotland’s countryside with typical Swedish goods for sale in Visby City, increasing the exploitation of the cultural heritage of the rural areas (e.g. churches, animals, farms). However, regional supply diversification strategies may also involve the exploratory creation of innovative products and services, such as the use of the forest for yoga, picnics, sports, and eco-trails.

Moreover, the integration of these new products and services into the existing tourism dynamics associated with the circulation of large-scale cruise ships, as well as the implied identification of other types of needs, can be divided into (a) physical, (b) digital infrastructure development, along with related requirements in terms of (c) partnerships and collaborations amongst stakeholders.

a. Identified needs related to physical infrastructures:

- Creation of a mini bazaar for local products at the ferry terminal.

- Installation of food and craft trucks or stands along the roads leading back to the ferry.

- Reorganisation and reinforcement of public transportation.

- Implementation or development of infrastructures to provide information to facilitate transportation inter-modality and to promote “soft” (non-motorised) forms of mobility.

- Supporting the development of new transportation services

b. Identified needs related to digital infrastructures:

- Implementation of joint campaigns and active participation in diverse digital platforms, local and global.

- Development of services and information for digital platforms (tour guides, different channels, and languages).

- Creation of a common strategy defining a “unique selling point” for the region or “stories” linking the traditional products to the characteristics of the place.

- Development of diverse communication strategies for different segments.

c. Partnerships and collaborations amongst stakeholders:

- Involvement of artists, students, and creative professionals in various forms of communication (creation of stories or visual elements, development of digital platforms, translation, interpretation, tour guides, and so on).

- Collaboration between service providers and regulatory institutions for development and management of digital platforms.

- Support from the regional government (information for entrepreneurs, development of physical infrastructures).

- Partnerships between rural and urban entrepreneurs.

- Creation of routes and circuits based on different products and services.

- Coordination with cruise companies.

- Coordination with national authorities for the utilisation of the pier.

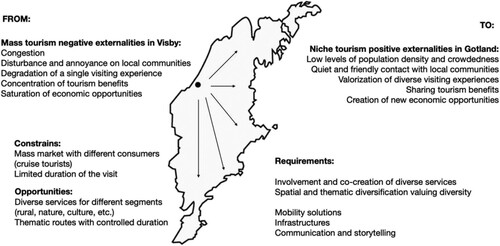

illustrates how the negative externalities caused by the massive presence of cruise tourists in Visby can be transformed into positive externalities related to the creation of products and services for niche markets along the Gotland island, assuming the constraints related to the limited “time-budget” of cruise tourists and the potential existence of diverse niche market opportunities along the island.

To address these potential markets, the island offers various products and services on the basis of territorial resources related to cultural heritage, ecosystems, natural landscapes, agricultural practices, or other forms of local knowledge. Combining the creation of these new products and services with mobility services to accommodate the time constraints of tourists requires a methodical process of stakeholder collaboration. Through this method, diverse thematic routes of limited duration can be established on a given territory, along with the associated storytelling, communication, and promotion processes. In this regard, the workshop provided a highly relevant contribution to initiate such a process.

Discussion

Contribution to research

By adopting an action research approach, the contribution of this work is linked to the concrete local characteristics and circumstances of the problem under analysis. However, from a conceptual viewpoint, these circumstances offer an interesting perspective for the process of development of tourism products: the community is dealing with a relatively massified product (cruise tourism), from which an opportunity exists to explore different types of “niche” markets, related to different resources, products, and potential experiences available on the Gotland island. In this sense, the community aims to develop a diversification process that must be anchored in a very strong existing attraction, namely, Visby's medieval walled city. As a result, the concept of diversified integration appears to be useful.

Such diversification is severely constrained by the particular characteristics of the visits that are also typical of other destinations, such as tourists arriving on large cruise ships with limited time, thereby restricting their ability to explore the island. Moreover, tourists must eliminate any delay factors that may cause them to miss the next cruise destination's departure. In addition to a highly controlled tour, they must receive in advance relevant and appealing information about opportunities on the island, infrastructure, and mobility services (in terms of duration). In this sense, a process of product development supported by the creation of routes, promoting the spatial and thematic diversification of local products and experiences, appears to be a solution that can combine the conceptual (in terms of marketing approaches) and practical answers to the limitations and opportunities of these niche markets.

Contribution to practice

The outcomes of this workshop demonstrate the significance of participatory methodologies for the formation and strengthening of ties within the local community, which may contribute to the enhancement of local social capital and strategic collaboration in tourism development processes. Moreover, it can be inferred that these methodologies can be applied to other economic activities, as there is no specific implication of this methodology for the case of tourism. Furthermore, the results illustrate the relevance of “action-research” methods, by revealing how the effective intervention of the researchers as objects of research can lead to fruitful results and analyses. It was also perceived that the interaction between members of the local industry and policy organisations with students and international researchers contributed to the emergence of new ideas and options not identified in previous meetings with similar purposes.

In terms of the definition of strategic guidelines for Gotland island, this workshop can be seen as a useful and relevant initial step, contributing to clarify the crucial problems, how they can be framed and what kind of orientations may be implemented.

Limitations

The study was conducted with long and short-time perspective – a duality that can help to contextualise the current situation in a long-term perspective. However, it creates a degree of methodological ambiguity that is not necessarily conducive to method or research perspective clarity. Consequently, other assessment methods may be utilised to identify distinct impacts for various policy scenarios, taking into account budgetary constraints or ranking preferences accordingly. In addition, the current workshop must be supplemented with such diverse processes of collective analysis in order to validate and compare the characteristics of OSM with those of other participatory decision-making methodologies.

Moreover, although the discussions within this workshop were characterised by a low (if any) level of conflict between different interests and motivations, this will not necessarily be the case in further aspects of discussion. For example, financial or logistic restrictions to the development of transportation infrastructures and services may benefit some stakeholders more than others. Furthermore, the benefits of the creation of routes with controlled duration may be perceived as potentially unbalanced by the different companies potentially involved. On a conceptual and general level, a general agreement exists regarding the primary objectives of the strategy (creating new economic opportunities by diversifying tourism experiences). However, when the discussion reaches more concrete and specific solutions to be implemented, the possibility of a more conflictual confrontation of perspectives must be considered (and anticipated).

Determining whether the ideas generated in the OSM workshop have been or will be implemented is difficult owing to the pandemic's effects on the tourism industry and the cruise tourism industry. Without cruises, nothing can be implemented. Ultimately, given that it remains unclear when normalcy will return, the future of cruise tourism and whether the ideas generated in the workshop will be recollected and executed are left unanswered.

Continued research

Conducting continuous longitudinal studies on the developments and the effects of different intervention techniques and of interaction between different types of actors is crucial. Academia and practitioners can benefit from a greater understanding of OSM as a strategy to diversify tourism services.

Conclusion

How OSM can be used to develop tourism diversification involving key stakeholders in a local business eco-system was the question to be answered in this three-dimensional article. Through the concrete outcomes of the workshop, the answer to the research question reveals that OSM can help to generate new questions and discussion points. Thus, the benefit of OSM is that it enables people to act in self-organising units and concentrate on them for emerging issues. This indicates that OSM is a method of development that unites participants and creates the conditions for development to occur at the appropriate level for the most pertinent questions encountered, and that those who know the required level set the agenda for the development process. In some instances, it may be necessary to identify the questions, whereas in others, it may be necessary to model the questions, and still in others, it may be necessary to generate solutions to pre-existing problems. In the case of the OSM workshop studied here, we observed that one success factor comprised the combination of “new blood” in the group, and the workshop methodology, allowing for free discussion. The OSM workshop also led to the identification of the following underlying aspects that were required to be taken further. Firstly, the importance of mobility services and infrastructures to guarantee that the new products and services can be used within the limits of the “time-budget” of the tourists. Secondly, the importance of storytelling to emphasise the linkages between the territorial characteristics and the new products and services. Thirdly, the importance of communication mechanisms to capture the attention of the visitors, whilst attracting the different market niches to the different types of new services to be offered. Fourthly, the importance of reinforcing the communication and collaboration between the local stakeholders involved.

Similarly, and following the typology of questions proposed by Vacik et al. (Citation2014), the proposals presented to solve the identified problems offer relevant and relatively detailed strategic preferences and orientations; however, they do not consider aspects, such as budgetary constraints, consensus building for the definition of specific actions or measures, or even the ranking and prioritisation of strategic preferences and proposals. The workshop can thus be viewed as a productive and constructive starting point for the formulation of a coordinated strategy. No workshop, regardless of how well it is conducted, will ever be able to propel a development process forward on its own. Thus, further discussion and deliberation must be conducted. Moreover, which actors have the authority and confidence of others to lead such a follow-up process must be determined.

The answer to the research question provided by the OSM in its historical and contextual context reveals that the identified problems in the workshop necessitate efforts that go far beyond the entrepreneurial product development processes. The majority of the presented problems and proposals were related to the existing supply, necessitating the development of new integrated circuits and packages as well as the corresponding communication strategies to value the resources and address the appropriate market segments. Coordination between entrepreneurs and the participation of creative professionals appear to be essential components of such a strategy. In this regard, the workshop serves as a valuable launching point for the implementation of such thematic and spatial routes that offer diverse tourism experiences.

Moreover, the development of tourism activities in the Gotland island is largely dependent on the intervention of public authorities. Aspects related to effective and comfortable transportation services are crucial when visitors spend limited time at a destination, thus requiring infrastructure development and support for the emergent mobility services (e.g. electric or non-motorised vehicles; collective transports). In addition, OSM contributed to the reinforcement of ties and social capital within local communities. OSM has the potential to foster a welcoming and democratic environment in which all participants are free to ask the questions they deem most important and express their own opinions and viewpoints. This leads to the conclusion that this method can strengthen the ties and connections between local stakeholders, thereby contributing to the development of community ties, local social capital, and capacity building, even in complex situations with historical roots, such as on Gotland (Moscardo, Citation2019).

The response to the research question in the context of diversification reveals that the method confirmed diversification of tourism products and services can transform negative tourism externalities into positive ones, as suggested in . Further, the underlying aspects identified in the OSM workshop (presented above) elucidate the relevance of defining routes and circuits along the island, organised according to specific themes, as a form of offering new experiences, as systematised by UNWTO and ETC (Citation2017). By organising the processes of product diversification according to thematic and spatial routes, integrating coherent tourism products and services in each of them would contribute to simultaneously address the problems related to the “time-budget” and the diversity of motivations and preferences of different niche markets within the high influx of cruise visitors. Furthermore, the utilisation of the pier (depending on national authorities and security regulations) to provide information and to promote easy transportation inter-modality was a crucial aspect for diversification.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aksoy, L., Alkire (née Nasr), L., Choi, S., Kim, P. B., & Zhang, L. (2019). Social innovation in service: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Service Management, 30(3), 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-11-2018-0376

- Albaladejo, I. P., & González-Martínez, M. I. (2018). Congestion affecting the dynamic of tourism demand: Evidence from the most popular destinations in Spain. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(1), 1–15.

- Alford, P. (2008). Open space-a collaborative process for facilitating tourism IT partnerships. Springer.

- Ansoff, H. I. (1987). Corporate strategy. Penguin.

- Åberg, K. G., & Svels, K. (2018). Destination development in Ostrobothnia: Great expectations of less involvement. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(sup1), S7–S23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2017.1312076

- Baldacchino, G. (2015). Feeding the rural tourism strategy? Food and notions of place and identity. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(1-2), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1006390

- Bason, C. (2010). Leading public sector innovation: Co-creating for a better society. Policy Press.

- Beaumont, N., & Dredge, D. (2010). Local tourism governance: A comparison of three network approaches. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(1), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903215139

- Benur, A. M., & Bramwell, B. (2015). Tourism product development and product diversification in destinations. Tourism Management, 50, 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.02.005

- Binkhorst, E., & Dekker, T. (2009). Agenda for Co-creation tourism experience research. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(2-3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368620802594193

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2000). Introduction. In B. Bramwell, & B. Lane (Eds.), Tourism, collaboration and partnerships: Policy practice and sustainability (pp. 1–23). Channel View Publications.

- Bushe, G. R., & Marshak, R. J. (2015). Introduction to the dialogic organization development mindset. In G. R. Bushe, R. J. Marshak, & W. Berett Koehler (Eds.), The NTL handbook of organization development and change. Wiley.

- Chavas, J.-P., Stoll, J., & Sellar, C. (1989). On the commodity value of travel time in recreational activities. Applied Economics, 21(6), 711–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/758520269

- Chevalier, J. M., & Buckles, D. J. (2013). Handbook for participatory action research, planning and evaluation (p. 155). SAS2 Dialogue.

- Cross, N. (2001). Designerly ways of knowing: Design discipline versus design science. Design Issues, 17(3), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1162/074793601750357196

- Della Corte, V., & Aria, M. (2016). Coopetition and sustainable competitive advantage. The case of tourist destinations. Tourism Management, 54, 524–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.12.009

- Dredge, D. (2006). Policy networks and the local organisation of tourism. Tourism Management, 27(2), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.10.003

- Dredge, D., & Gyimóthy, S.2018). Collaborative economy and tourism: Perspectives, politics, policies, and prospects. Springer.

- Du Cros, H., & Kong, W. H. (2020). Congestion, popular world heritage tourist attractions and tourism stakeholder responses in Macao. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6(4), 929–951. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-07-2019-0111

- Emmendoerfer, M. L., Olavo, A. V. A., Silva Junior, A. C., Mediotte, E. J., & Ferreira, L. L. (2020). Innovation lab in the touristic development context: Perspectives for creative tourism, Creative tourism dynamics: Connecting travellers, communities, cultures, and places, 87–101.

- Farinosi, M., Fortunati, L., O’Sullivan, J., & Pagani, L. (2019). Enhancing classical methodological tools to foster participatory dimensions in local urban planning. Cities, 88, 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.11.003

- Fyall, A., Garrod, B., & Wang, Y. (2012). Destination collaboration: A critical review of theoretical approaches to a multi-dimensional phenomenon. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1-2), 10–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.002

- Gaziulusoy, A. I., & Ryan, C. (2017). Shifting conversations for sustainability transitions using participatory design visioning. The Design Journal, 20(1), S1916–S1926. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352709

- Gibson, C. B., & Birkinshaw, J. (2004). The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 47(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159573

- Gilson, L. L., Mathieu, J. E., Shalley, C. E., & Ruddy, T. M. (2005). Creativity and standardization: Complementary or conflicting drivers of team effectiveness? Academy of Management Journal, 48(3), 521–531. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.17407916

- Gössling, S., & Mattsson, S. (2002). Farm tourism in Sweden: Structure, growth, and characteristics. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 2(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/150222502760347518

- Grauslund, D., & Hammershøy, A. (2021). Patterns of network coopetition in a merged tourism destination. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(2), 192–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1877192

- Hall, C. M. (2019). Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1044–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560456

- Herman, M., & Jain, S. (2006). Open space technology, Inviting leadership practice (third edn.). http://www.michaelherman.com/publications/inviting_leadership.pdf

- Hjalager, A.-M., Kwiatkowski, G., & Østervig Larsen, MØ. (2018). Innovation gaps in Scandinavian rural tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2017.1287002

- Holmen, P. (2015). Complexity, self-organization, and emergence. In G. R. Bushe, R. J. Marshak, & W. Berett Koehler (Eds.), The NTL handbook of organization development and change (pp. 123–150.

- Juran, J. M. (1964). Managerial Breakthrough: A new concept of the manager’s job. McGraw-Hill.

- Klein, K. J., & Sorra, J. S. (1996). The challenge of innovation implementation. The Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 1055–1080. https://doi.org/10.2307/259164

- Kotler, P., Bowen, J. T., Makens, J. C., & Baloglu, S. (2017). Marketing for hospitality and tourism (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Lew, A., & McKercher, B. (2006). Modelling tourist movements: A local destination analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(2), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.12.002

- March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

- Marcussen, C. H. (2017). Visualising the network of cruise destinations in the Baltic Sea – a multidimensional scaling approach. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(2), 208–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1142893

- Margaryan, L., & Fredman, P. (2017). Natural amenities and the regional distribution of nature-based tourism supply in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(2), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1153430

- McComb, E. J., Boyd, S., & Boluk, K. (2017). Stakeholder collaboration: A means to the success of rural tourism destinations? A critical evaluation of the existence of stakeholder collaboration within the Mournes, Northern Ireland. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(3), 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358415583738

- McKean, J. R., Johnson, D. M., & Walsh, R. G. (1995). Valuing time in travel cost demand analysis: An empirical investigation. Land Economics, 71(1), 96–105. https://doi.org/10.2307/3146761

- Moscardo, G. (2019). Rethinking the role and practice of destination community involvement in tourism planning. In K. Andriotis, D. Stylidis, & A. Weidenfeld (Eds.), Tourism policy and planning implementation. Routledge.

- Nauheimer, H.2005). Open space technology. New stories from the field: The change management tool book.

- Nauheimer, H., & Ilieva, E. (2005). Creating networks for social transformation through intercultural learning Bulgaria. In H. Nauheimer (Ed.), Open space technology. New stories from the field: The change management tool book.

- Norman, D. (2002). Emotion and design: Attractive things work better. Interactions, 9(4), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1145/543434.543435

- O’Connor, D., & Cooper, M. (2005). Participatory processes: Creating a “marketplace of ideas” with open space technology. Innovation Journal, 10, 1–12.

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2020). Rethinking tourism success for sustainable growth. In OECD Tourism trends and policies. OECD.

- Owen, H. (1997). Expanding our now. The story of open space technology. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Owen, H. (2008). Open space technology: A user’s guide. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Palsson, N. I., & Singh, V. (2018). Community empowerment through grassroots action: A story of building personal and local resilience with the transition towns model. Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies, 5(3), 4–4. https://doi.org/10.24926/ijps.v5i3.1599

- Patton, R., Chappelle, N., Fisher, U., McDowell-Burns, M., Pennington, M., Smith, S., & Vitek, M. (2016). Teaching general systems theory concepts through Open Space Technology: Reflections from practice. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 35(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1521/jsyt.2016.35.4.1

- Pearce, D. G. (1988). Tourist time-budget. Annals of Tourism Research, 15(1), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90074-6

- Perkins, R., Khoo-Lattimore, C., & Arcodia, C. (2020). Understanding the contribution of stakeholder collaboration towards regional destination branding: A systematic narrative literature review. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 43, 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.04.008

- Qiu, H., Chen, D., Yang, J., Zhang, K., & Liu, T. (2022). Tourism collaboration evaluation and research directions. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.2023838

- Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2013). The SAGE handbook of action research participative inquiry and practice (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Salvatore, R., Chiodo, E., & Fantini, A. (2018). Tourism transition in peripheral rural areas: Theories, issues, and strategies. Annals of Tourism Research, 68, 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.11.003

- Song, H., Liu, J., & Chen, G. (2013). Tourism value chain governance: Review and prospects. Journal of Travel Research, 52(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512457264

- Stringer, E.T. (2014). Action research (4th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Thomas, R. (2013). Small firms in tourism. Routledge.

- Timur, S., & Getz, D. (2009). Sustainable tourism development: How do destination stakeholders perceive sustainable urban tourism? Sustainable Development, 17(4), 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.384

- UNWTO. (2007). A practical guide to tourism destination management. World Tourism Organization.

- UNWTO and ETC. (2011). Handbook on tourism product development. World Tourism Organization and European Travel Commission.

- UNWTO and ETC. (2017). Handbook on marketing transnational tourism themes and routes. World Tourism Organization and European Travel Commission.

- Vacik, H., Kurttila, M., Hujala, T., Khadka, C., Haara, A., Pykäläinen, J., & Tikkanen, J. (2014). Evaluating collaborative planning methods supporting programme-based planning in natural resource management. Journal of Environmental Management, 144, 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.05.029

- White, L. (2002). Size matters: Large group methods and the process of operational research. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 53(2), 149–160.

- Wondirad, A., Tolkach, D., & King, B. (2020). Stakeholder collaboration as a major factor for sustainable ecotourism development in developing countries. Tourism Management, 78, 104024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104024

- Yılmaz, Y., & Bititci, U. S. (2006). Performance measurement in tourism: A value chain model. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 18(4), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110610665348