ABSTRACT

This study explores the role of employees as both a target group and co-creators of employer brand equity in tourism and hospitality. Extant research has largely focused on the effects of external employer brands; however, studies on internal employer branding have been lacking. The research problem is addressed through the conceptual lens of employer brand equity. To provide empirical insights into employee experiences, exploratory in-depth interviews were conducted with 16 employees in hotels, restaurants, and retail stores in Northern Sweden. While employees constitute a target market for internal employer branding, they also co-create the employer value proposition. Employees act as brand members, representatives, advocates and influencers, increasing knowledge about the organization internally and externally. However, in practice, companies in the service sector seem to place more focus on the customer experience than on reminding the employees of the brand promise towards them. This study identifies and describes the role of employees in the employer branding process by developing a new conceptual framework. Thereby, it adds to the understanding of co-creation in employer branding, an under-researched area which has been suggested to become a new paradigm in the employer branding literature.

1. Introduction

While exploring basic assumptions of employees within the hospitality industry has been done with regards to their views on guests, co-workers and competitors (Gjerald & Øgaard, Citation2010), there is a lack of such research within this highly volatile industry. One assumption that has been investigated even less is employee perspectives on their place of employment, or the employer brand (Gilani & Cunningham, Citation2017). Employer branding involves promoting a clear view of what makes the company different and desirable as an employer externally to prospective employees and internally to existing coworkers (Backhaus, Citation2016; Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004).

Attracting and retaining the right talent is especially important in tourism and hospitality, in which organizational competitive advantage is directly derived from employees (Murillo & King, Citation2019). Management of frontline staff retention is core for tourism and hospitality companies to be able to build relationships with customers (Lashley, Citation2008). Research has shown that organizations with strong employer brands have lower recruitment costs, lower employee turnover, and better relations with their employees (Berthon et al., Citation2005; Chhabra & Sharma, Citation2014). Despite its potential and importance, employers in tourism and hospitality sectors are rarely seen as forerunners in employer branding (Gehrels, Citation2019). In addition, the industry has taken a major hit during the Covid-19 pandemic, leaving hospitality workforce highly impacted due to massive layoffs (Baum et al., Citation2020; Gjerald et al., Citation2021) and there is uncertainty whether talented employees will ever return (Baum et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the question of employer attractiveness is crucial on both organizational and industry levels.

Ultimately, employer branding aims to increase employer brand equity (EBE), which Theurer et al. (Citation2018) define as “the added value of favorable employee response to employer knowledge” (p. 156). Thus, EBE helps to create interest externally among potential employees, as well as to continue creating value for current employees by emphasizing organizational association and belonging (Alshathry et al., Citation2017). While both potential and current employees are targets for employer branding, most research has focused on recruitment (Theurer et al., Citation2018), and empirical research in the area has mainly been quantitative (Auer et al., Citation2021).

Despite the possibilities of internal employer branding to foster positive employee engagement, research as well as practitioner efforts have primarily focused on employer branding as a means to achieve a distinctive external reputation, and largely neglected the internal aspects (Kalińska-Kula & Stanieć, Citation2021). In a recent review of the current state of Nordic hospitality management research, Gjerald et al. (Citation2021) point out that there is a need to understand the changing role of hospitality employees and to capture the voices of both permanent and seasonal workers. Furthermore, Murillo and King (Citation2019) state that it is important to understand why employees respond to practices aiming to attract, develop and retain individuals who share and deliver the employing brand’s values in the hospitality sector. They highlight the lack of research on implicit, social attributes that represent the organization as a place of work.

This study responds to these current gaps in knowledge by exploring employee experiences of internal employer branding in tourism and hospitality companies. The study focuses on customer-facing employees, since they represent their employer’s brand in direct interactions with customers (Schlager et al., Citation2011). Thereby they create employer associations about the organization to outsiders. Employees are also part of the work community (Valkonen et al., Citation2013), and it has been argued that employees have an active role in creating the employer brand (Aggerholm et al., Citation2011; Auer et al., Citation2021). However, what is lacking in the literature is a more holistic view on employer branding that recognizes the active role of employees as co-creators (Auer et al., Citation2021).

While the concept of (value) co-creation in hospitality research especially in the Nordics has been studied throughout the past 20 years (Björk et al., Citation2021), it has not received the same attention in employer branding (Aggerholm et al., Citation2011; Auer et al., Citation2021; Smith, Citation2018). According to Smith (Citation2018), co-creation offers an opportunity to a paradigm shift in the employer branding literature. As target markets tend to be treated as passive receivers, the current perspective of brand equity is limited (Smith, Citation2018). The author also acknowledges that co-creation in the employer branding context is still considered pre-scientific. Similarly, Saini et al. (Citation2022) state that a co-creational approach to employer brand equity is lacking. Therefore, this study aims to add to the body of knowledge by aligning the theories and vocabularies through the development of a conceptual framework that combines the concepts of co-creation and employer brand equity. Hence, the purpose is to explore the role of employees as both a target group and co-creators of employer brand equity in the context of tourism and hospitality.

2. Literature review

The employer brand concept is often defined as “the package of functional, economic and psychological benefits provided by employment, and identified with the employing company” (Ambler & Barrow, Citation1996, p. 187). It builds on looking at employee attraction and retention with a marketing lens, seeing potential and current employees as their customers and applying customer experience elements to create value (Alshathry et al., Citation2017). Thus, organizations must identify and communicate the unique “employment experience”, or the tangible and intangible elements connected to employment, embedding the key values that guide the organization as a collective (Edwards, Citation2009). The employer brand is encapsulated in the employer value proposition (EVP) which should represent and communicate what the organization offers to its employees (Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004; Chhabra & Sharma, Citation2014; Theurer et al., Citation2018). A successful employer brand is said to have three characteristics: (1) it is noticeable and known, (2) its value proposition is relevant to and resonates with the (potential) employees, and (3) it is unique and different from what the competitors offer (Moroko & Uncles, Citation2008). It is important to note that all organizations have an employer brand, whether or not they actively work with employer branding (Backhaus, Citation2016).

The employer branding activities should include information about the identity and what the employees perceive as the central characteristics of the organization (Edwards, Citation2009). The fit between the beliefs, cultures and values of employees on one hand, and of the organization on the other (Lauver & Kristof-Brown, Citation2001) creates the opportunity for the organization to become known as a great place to work (Tanwar & Kumar, Citation2019). Values are particularly important for hospitality companies, since the employees are expected to deliver the brand message to the customers (Barrow & Mosley, Citation2005; Murillo & King, Citation2019), and they are more likely to do so if they are treated similarly to what the organization promises its customers (Barrow & Mosley, Citation2005). Aggerholm et al. (Citation2011) propose that brand values ought to be negotiated and co-created, as they are socially constructed by the members of the organization.

2.1 Co-creation

The brand co-creation paradigm sees different stakeholders, such as employees, investors, customers and business associates as partners to the corporate brand (Gregory, Citation2007). Co-creation has been studied in the corporate identity sphere, which is related also to internal employer branding. The identity is in constant flux and develops over time through stakeholder engagement (Iglesias et al., Citation2020). Thus, instead of seeing the brand and its identity as managed by the organization, it builds on a dynamic process, where the meaning of the brand and brand values are negotiated between the partners (Gregory, Citation2007; Hatch & Schultz, Citation2010). It has been suggested that this co-creation can be viewed through the lens of performativity theory perspective, where the organization and different stakeholders act as brand performance agents (Da Silveira et al., Citation2013; Törmälä & Gyrd-Jones, Citation2017; Von Wallpach et al., Citation2017). It builds on the idea that identity is a social construct, as well as a dynamic process and an active performance by the individual (Goffman, Citation1959, Citation1967). However, more research on the performative approach to branding has been called for; in particular, studies that aim to understand the relevant performances that co-create the brand (Iglesias et al., Citation2022).

The concept of co-creation has also received a lot of attention in service, tourism and hospitality literature, focusing on the relationship between the customer and the service provider (Björk et al., Citation2021). It is often customer centric and revolves around value creation for the customer. Employees represent the organization and co-create memorable experiences, but in the context of employer branding employees are mainly seen as a target market for the employer brand, or as its internal customers. Employees also have valuable assumptions about guests, co-workers and competitors, with such assumptions being either destructive or constructive to the organization (Gjerald & Øgaard, Citation2010). Very recently, Saini et al. (Citation2022) emphasized the novel idea of seeing employer brand equity as a co-creation process and called for more research on this. Also Auer et al. (Citation2021) and Smith (Citation2018) state that co-creation can be a valuable lens to employer branding, but previous literature has lacked interest in understanding employee agency and the role they play in contributing to the employer brand. In other words, while the co-creation literature sees employees as co-creators of brand identity and customer brand experiences, it is lacking in the employer branding sphere: employer brand value is merely created for the target market, not by them.

2.2 Employer brand equity

Employer branding outcomes can be described in terms of employer brand equity, defined as the intangible assets or the value of favorable responses in the minds of existing and prospective employees (Ambler & Barrow, Citation1996; Theurer et al., Citation2018). Conceptually, brand equity is built on Aaker’s and Keller’s seminal frameworks in the 1990s. Specifically, Aaker (Citation1991) classified brand equity as name awareness, brand associations, perceived quality, brand loyalty, and other assets, whereas Keller (Citation1993) viewed brand knowledge as brand equity assets, consisting of brand awareness and image. The interdisciplinary nature of employer branding presents issues to establishing employer branding as its own area, and therefore, rooting studies in branding theories is crucial (Theurer et al., Citation2018).

Recently, Alshathry et al. (Citation2017) highlighted the importance of adapting the concept into the employment context by adding a HRM perspective. Employer branding then creates two valuable assets, namely brand associations and brand loyalty (Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004). These assets are incorporated in Minchington’s (Citation2010) model of EBE, which is based on Aaker’s (Citation1991) definition and consists of four dimensions: employer brand familiarity, associations, experience, and loyalty. This framework was also adopted by Alshathry et al. (Citation2017). Resting on central tenets of signaling theory and social exchange theory, the framework is developed from the classical brand equity models and adapted to the employer branding context. Hence, it integrates the major dimensions of EBE recognized by branding researchers and is therefore chosen as the basis for the conceptualization of EBE in this study.

2.2.1 Familiarity/awareness

Familiarity with the employer brand can be defined as “the level of awareness that a job seeker has of an organization” (Cable & Turban, Citation2001, p. 124) and is essential before being able to build deeper knowledge of the organization. Most of the research about familiarity (also labeled awareness) has had an external focus, looking at how familiarity with the employer can affect job seekers’ attitudes and behaviors (Alshathry et al., Citation2017). However, Ambler and Barrow (Citation1996) state that employer familiarity goes beyond being aware of the employer’s brand name and is relevant to discuss even among current employees. Despite being relevant, familiarity in the internal context has received less focus (Alshathry et al., Citation2017).

The traditional view of the employer branding process is that it starts with developing the employer value proposition (EVP) which is then communicated externally to attract talent, as well as internally to retain and engage employees (Backhaus, Citation2016). Backhaus (Citation2016) points out the need to continuously remind employees of the EVP and enhance their understanding of what makes their employment experience unique. Performance of the employees, and ultimately the entire organization, is dependent on the level of brand awareness and the attitudes connected to the employer brand (Ambler & Barrow, Citation1996). Internal employer branding can enhance familiarity of the benefits (in particular the intangible psychological benefits) and reinforce the associations employees have of the employment experience. Aggerholm et al. (Citation2011) note that brands are socially constructed and the meaning of them negotiated in a specific social setting. Thus, value is then created in the conversational space between the organization and the individuals, for example when establishing the uniqueness of the EVP (Smith, Citation2018).

2.2.2 Associations

Employer brand associations are the “top of mind” ideas and emotional responses in the memory of the individual, and they are connected to the intangible psychological and functional benefits (Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004). Potential employees tend to rely on previous work experiences, as well as their own identity and values to make sense of any employer branding messages (Auer et al., Citation2021); therefore, these associations can be difficult to manage. Moreover, interactions with the company employees can create associations about the company as an employer in the minds of potential employees (Auer et al., Citation2021; Gelb & Rangarajan, Citation2014). However, current employees are also affected by the attitudes of others, and the outsider view (for example corporate reputation) can affect employees’ associations of the employer brand (Alshathry et al., Citation2017). Employer brand associations can consist of anything the employee has linked in memory, and thus the associations can be both positive, negative, and contradictory. Taken together, they form a generalized impression of the organization as an employer (Alshathry et al., Citation2017).

Many previous studies (e.g. Gelb & Rangarajan, Citation2014) have recognized the relevance of service employees in building brand equity and emphasize that employees must understand what the brand stands for and how they can contribute. The role of the front-line staff extends beyond being a representative of the service brand, as they directly influence the organization’s marketing capabilities in their boundary spanning role (King et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, they represent the company as a place of work in the eyes of potential employees (Gelb & Rangarajan, Citation2014). Employees interact with customers daily in the service context, and customers can be potential employees as well. Through these interactions, they form an image of the organization as an employer (Gelb & Rangarajan, Citation2014; Lievens & Slaughter, Citation2016).

Internal brand communications can be used as means to form and influence employees’ associations and have therefore been studied in the internal branding literature. Valkonen et al. (Citation2013) argue that the recruitment process is of utmost importance to find employees with the right skills set, and a personality that fits the job itself, as well as the existing team. They further suggest that training activities and socialization are important tools to mold the employee values, so that they “embody their company spirit” (p. 239). Piehler et al. (Citation2016) point out that the different aspects of a brand can be rather abstract and suggest that employees might need help in decoding the brand identity and translating it into work-related behaviors.

2.2.3 Experience

Customers can have experiences with a company that help them gain more knowledge of the organization as an employer, but only employees can truly experience the employer (Alshathry et al., Citation2017). Mere knowledge of the brand, although essential, is not enough to build a strong brand – it is the actual employment experience that matters. Therefore, it is important to stress that internal (employer) branding is not only a question of communication (Kimpakorn & Tocquer, Citation2009). According to Backhaus and Tikoo (Citation2004), once hired, training employees in internal branding activities can lead to career advancement, thus enhancing what is known as the total employer brand experience.

Values constitute the essence, or DNA, of the employer brand (Barrow & Mosley, Citation2005) and seem to be a significant contributor to the employment experience. People are looking for purpose and meaning with their jobs and want the values of the organization to fit their own (Tanwar & Kumar, Citation2019). Values can be seen as a promise to the employees, and the employee’s experience determines whether or not this promise – the psychological contract – is fulfilled (Moroko & Uncles, Citation2008). The employee experience consists of multiple touchpoints, or interactions, with the organization and its culture (Plaskoff, Citation2017). Policies, materials, physical space, and so on shape the employees’ perception of the overall experience. Thus, researchers emphasize the importance of making the intangible tangible (Plaskoff, Citation2017). The employer brand associations should be related to the actual experience (Alshathry et al., Citation2017), and companies therefore need to reflect upon how their EVP is present in the different touchpoints.

Aligning the employer brand associations with the “true” experience is important, but far from easy. The employee’s experience includes complex elements such as relationships with co-workers and supervisors, and this is difficult to manage (Alshathry et al., Citation2017). The social element, including social relationships and atmosphere at the workplace, is an essential contributor to the employer brand. In the employer branding literature, members of the organization are considered part of the EVP (for example, by providing social value as conceptualized by Berthon et al., Citation2005). Similarly, Edwards (Citation2009) discusses employer branding as summarizing the “shared employment experience” (p. 7), while Plaskoff (Citation2017) states that the quality of employees’ experiences influence their satisfaction, engagement, commitment and even performance. A positive employer brand experience can be an incentive to stay with the organization (Punjaisri et al., Citation2008); that is, to remain loyal to the employer.

2.2.4 Loyalty/commitment

In a product branding context, loyalty can be defined as the attachment a consumer has to a brand (Aaker, Citation1991). For employer brands, however, loyalty can “be reflected in various forms including attaching self and maintaining a relationship with an employer as well as a feeling of belonging” (Alshathry et al., Citation2017, p. 418). Loyalty with an employer (brand) is often measured in terms of staying in the company (Afshari et al., Citation2020). Employer brand loyalty, however, is often conceptualized as the commitment an employee has to the employer (e.g. Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004). Backhaus and Tikoo (Citation2004) include both a behavioral element connected to organizational culture and an attitudinal one connected to organizational identity. According to the authors, internal employer branding can be used to affect organizational culture and identity, which in turn influence the level of employees’ loyalty. Further, organizational commitment is the attachment to the company, and is closely related to the culture that consists of the assumptions and values of the company. Organizational identity, on the other hand, can be seen as the collective understanding of “who we are” as a company (Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004). In particular, recent research suggests that organizations in tourism and hospitality should foster a corporate culture that allows employees to feel a sense of belonging and trust both within the group of colleagues and with the employer (Schneider & Treisch, Citation2019).

Similarly, Afshari et al. (Citation2020) recently demonstrated the importance of understanding and building identification among the individual employees to create consensus and commitment as a collective. Identification refers to the employees’ sense of belonging to the brand (Punjaisri & Wilson, Citation2011). Social identity theory posits that social identity and group membership bring value to the individual (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1985), and people seek to coordinate behaviors as a collective (Abrams & Hogg, Citation1990). Organizational identification is a form of social identification, and the organization can be seen as an entity embodying the characteristics that define its members (Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989). If employees are expected to truly believe the brand message and become committed, it should be translated into tangible evidence, like in decision-making and how processes are run in the company (Barrow & Mosley, Citation2005). Aggerholm et al. (Citation2011) suggest that when creating sustainable organizations, employees should be seen as partners or co-creators of corporate values and recommend that values should be negotiated together as a collective to build an authentic employer brand.

In addition to being brand communicators towards customers, employees are sources of employment information and corporate reputation due to their insights of the organizational climate (Keeling et al., Citation2013). Staff word-of-mouth has been identified as an important means of recruitment in retail (Keeling et al., Citation2013). Kimpakorn and Tocquer (Citation2009) further argue that passionate brand advocates can be developed by communicating the true meaning of the brand, and by delivering on the brand promises. Importantly, brand advocacy can continue even after leaving the organization (Barrow & Mosley, Citation2005).

3. Research method

Given the exploratory purpose of the study, i.e. to explore the role of employees as both target group and co-creators of employer brand equity in the context of tourism and hospitality, we adopted a qualitative approach. Hence, the aim was not to reach generalizable conclusions, but to provide insights based on naturalistic inquiry (cf. Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). To this end, we collected data through in-depth interviews with people currently or recently working in customer-facing roles within the retail, hotel, or restaurant sector in Northern Sweden. With hotel and restaurant businesses being at the core of the definition of hospitality (cf. Lashley, Citation2008), retail was added due to the sector’s importance to the tourism and hospitality industry. Any actors that sell to customers whose shopping is regarded as tourism consumption are part of tourism and hospitality (Bohlin et al., Citation2017). Shopping itself has also become a major travel motivation and tourism activity, which has changed how the retail industry operates and caters to tourists (Wan et al., Citation2023). In Sweden, tourists’ retail expenditures constituted 35 percent of total tourist consumption in 2019 (Tillväxtverket, Citation2020).

Prospective participants were identified and contacted through a combination of convenience and snowball sampling. Furthermore, we used a maximum variation sampling approach (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985), with the aim to achieve a mix of genders, ages, type of sector, and time of employment among informants. Rather than adopting a purely inductive approach, the empirical study was based in the reviewed literature and the EBE framework (Alshathry et al., Citation2017; Minchington, Citation2010). Therefore, a priori thematic saturation was applied (Saunders et al., Citation2018) and sampling was considered completed when examples and sub-themes within all domains of the EBE framework had been identified. In total, we conducted interviews with 16 individuals (of which eleven females) between 19 and 75 years (median: 34). The number of years they had worked within their industry varied widely, with a median of 10.5 years (see ).

Table 1. Sample background information.

The researchers used a semi-structured interview guide that ensured the same topics were covered in all interviews, while still being open-ended and very flexible to probing questions (Roulston & Choi, Citation2018). All interviews were conducted face-to-face in neutral places such as conference rooms, restaurants, or cafés. After the interview, each respondent received a lottery ticket for participating. In addition to extensive notetaking, the interviews were recorded and transcribed. The resulting data were analyzed by two researchers by conducting a thematic analysis, following the six-step approach outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). As we relied on a theoretical (in contrast to inductive) analysis, some aspects of the data are analyzed in more detail instead of providing a broad picture of the overall data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Throughout the study, the researchers adhered to quality standards of trustworthiness such as investigator triangulation, variation in time and place of the interviews, discrepant data checks, and storing all recordings, notes, and other information (Lewis, Citation2009; Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985).

4. Results

The following sections present, in summarized form, the main findings of the empirical study. Considering the theoretical approach of the thematic analysis, the results are structured according to the EBE framework described in section 2.1. Illustrative quotes are provided for each theme (for an overview of all themes and sub-categories, including additional sample quotes, please see the online Appendix.) The respondents are anonymized and only labelled as R1, R2, etc. in connection to the interview quotes.

4.1 Familiarity/awareness

Familiarity with the employer brand was discussed with interviewees in terms of what their organization stands for, and in what way this is shown or discussed at work. That is, what are the explicit or implicit values of the organization? Two main sub-themes emerged within this category. Firstly, most of the participants talked about what the company stands for in terms of the customer experience, rather than from the employee's perspective. For example, “We all know that we must perform. We’re a small company, if we get a bad reputation, we will have no customers” (R2). Several of the interviewees also mentioned that they were aware that the organization has established values, but they were not able to name them, such as R11: “Yes, there are such [values], but, yes, what are they? I don’t remember. But primarily they are emphasizing 'see the customer’; you should recognize personalities and adapt the selling to that”.

Those with some form of managerial responsibilities seemed to be more aware of the importance of shared company values. One respondent mentioned that they discussed values often: “The values are printed on the walls, they should be read and understood before you sign the contract … Then you can say 'You signed this’” (R9). This perspective shows that values are not only a promise to the employees but also a “code of conduct” in a sense. Another interviewee stated,

Because I was part of the management team the answer is a big YES. However, [I’m not sure] how good we were at spreading it to others … In the management team we talked about them surely once a week, but I think we did much worse with [talking to] the rest of the staff. (R13)

4.2 Associations

To capture the employer brand associations, respondents were asked to describe their employer. Their associations, in the form of “top of mind” ideas and emotional responses, were based on their own personal experiences. A variety of things were discussed, connecting both to symbolic values such as the brand or organization, culture, and climate, but also to instrumental values such as policies and job descriptions. One important theme was the social atmosphere and the relationships between co-workers within and between departments; for example, as discussed by R16: “Here we really try to be flexible and help each other outside the departments as well, you are a little bit here and there, helping out”. Many of the respondents reflected on the management of the company and how they are treated. In the case of smaller employers, it was the actual owners who were described, rather than the organization as such: “[It is] like a family, they take care of their employees. They are attentive to that you enjoy working there” (R3); “It’s the most considerate employer who thinks about his staff” (R2).

On the other hand, some of the associations were negative, for example, “You’re not supposed to walk, you need to run. Burnouts are probably a big issue” (R12). Certain associations demonstrated the importance of specific (negative) events: “I had a work injury, but they didn’t seem to respect it. Told me to take time off and rest, but they still called me to ask if I could come to work” (R7). Another respondent reflected on the employer from a broader perspective, stating, “The organization is too small in relation to the [corporate] brand. I would have liked to have better competencies in some of the departments” (R4).

A third sub-theme emerged around respondents’ perceptions of how outsiders viewed the organization. Some of them said that this view does not always correspond with reality: “It varies depending on which [target] group you belong to … [The company] should perhaps be better at explaining it” (R1). Overall, the perceptions of outsiders seemed important to the interviewees. For example, R8 stated: “I hope they think it’s good. We don’t have that big staffing needs, many apply [for open positions] but the larger [work-]places have more [applications]”. Another respondent had his career choices initially questioned by his friends and family, and this was something he had reflected upon: “In the beginning, it was always like, 'Why would you invest in [the company]?’ But now my close ones say that perhaps it wasn’t so stupid after all … ” (R6). The same interviewee further talked about how the company is viewed by others, stating that, “[…] there are many 'good names’ [talents] that we have attracted, so I think we are a good employer. But it’s more difficult among young people; I think that’s related to how their parents are talking to them [about working there]”. Another participant reflected on outsiders’ perhaps biased view of the employees at her workplace: “[…] it is a design hotel and there’s nothing else like that in [the city]. And there are lots of people who think that you are in a certain way, that it’s supposed to be glamorous, but it’s not like that. We’re just ordinary people working here” (R15). It also seems this can even affect their experience in terms of a feeling of social acceptance and sense of pride. One respondent, working in retail, talked about the physical space in terms of the external look of the store, how it affects what people say about the company, and how this made her feel about the employer: “You can feel a bit ashamed because the store is so ugly” (R5).

4.3 Experience

A major sub-theme reflecting the employee experience is related to the social dimension of the work. Good social atmosphere among the insiders, both co-workers and managers, are seen as the most important factor for a positive work experience by almost all respondents. A typical response when talking about what is most important for enjoying being at work was, “That you have fun and get along with your colleagues” (R2). The social element is connected to the individual’s wellbeing, but also represents the social identity of the group (insiders) that is then reflected in the instrumental job attributes. One respondent talked about when she first started to work at the company, full of inspiration and presenting new ideas: “I came in and said 'Now we should start to have routines’, and people rolled their eyes. Now I’ve ended up there myself, that’s how it works” (R5). The members of the organization find a way of doing things that evidently becomes part of the employment experience. This in turn contributes to the social value of the employer brand.

In addition to the co-workers, the role of management seems crucial for the experience in terms of creating engagement. As one participant stated, “I think the colleagues and the boss [are most important]; that determines how the atmosphere is and that’s important!” (R14). One interviewee, with long experience in the hospitality sector, pointed to the manager as the most important aspect for job satisfaction: “A good boss. I have high expectations of managers. One who is responsive, makes things happen, [is] genuine” (R9). On the other hand, poor management can be the reason for leaving, as one of the participants described: “I think [the manager] does not really see the value of people. When the staff is not feeling well, it’s not fun anymore. So then I thought, now it's done, it's enough” (R13).

A second sub-theme, which is also social in natures, illustrates a main reason why many choose to work in tourism and hospitality. They enjoy the contact with customers, and this forms a valuable part of the employee experience. In a way, it seems to be a personality trait that signifies people working in the industry, as the following quote illustrates: “And then I like making customers happy, I guess. That’s my basic philosophy” (R13). The interviewees also tended to describe people who “fit” in the industry, and at the company, as service-minded and social. Another participant emphasized the feeling she gets from satisfied customers: “The guests are so happy and that feels good” and stated that “I get hugs from customers when they leave” (R8). Similarly, R5 pointed out that “(…) feedback from customers is really rewarding.”

The latter quote is also related to the last sub-theme that emerged as important in relation to employee experience: feeling acknowledged and being recognized for the job one does, as well as feeling that one gets to develop at work. For example, one participant highlighted that is was important for her “to be able to develop. Right now, I develop because I learn so much” (R5). However, what acknowledgment and recognition means seems to vary between interviewees. Aspects mentioned included being acknowledged by the management, good salary and compensation, and being “seen” and taken care of by the company. As one interviewee put it: “I want my boss to see the good work I do, to be praised when you’ve done something good. Salary becomes more important the older you get” (R4).

4.4 Loyalty/commitment

Some of the respondents had no plans on leaving the company; some had already quit or planned on doing so at some point in the near future. Despite this most of them (had) enjoyed their time with the employer and felt a connection or a commitment to the organization, which forms a sub-theme of attitudinal loyalty. Throughout the interviews, many of the respondents emphasized the relationships among colleagues, many of them calling them “family”. As also highlighted in the Experience theme, hearing positive feedback from management (even if only via newsletters) seems to build motivation and commitment: “When we are doing well, we get to hear it, and it’s fun and you become motivated. When it’s going bad … it’s tougher. But the managers encourage you by saying ‘We are doing this together!’” (R10). Involving employees to build loyalty seems important, but for it to be successful, feedback might not be enough, as the following quote indicates: “They involve the staff more today than before, for example when it’s going bad. Get the staff involved in the strategy, the company as a whole, in order to build this feeling. But as an employee you don’t really get anything for doing it. It should be rewarded somehow” (R12).

All respondents but one talked about how they had recommended others to apply for jobs at “their” company, which is a clear indication of behavioral loyalty. Even those who had quit their jobs still practiced brand advocacy, for example by recommending the employer to others. Moreover, as mentioned by one of the interviewees, “It still feels like my job, even though I have quit … I guess it is because I feel passionate about it” (R13). Generally, the interviewees had formed an understanding of what type of a person would fit into the organization, partially depending on the collective of the employees, but also based on the (inferred) attributes of the employer. Almost all of them also regularly discussed their employment experiences with friends and family. By doing so, they spread information and awareness about the employer brand with outsiders. Many of those who had, or would, recommend the employer to others also mentioned that they did so only if they could see a fit between the potential employee and the employer. For example, R11 said: “I would recommend [working here], but you should have an interest. One should be passionate about this”.

5. Discussion

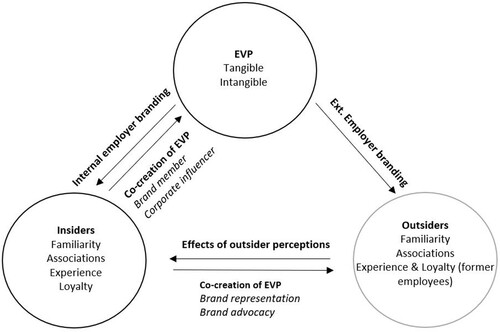

The service marketing literature has emphasized the meaning of employees, which can be extended to an employer branding context. First, it can be stated that the role of employees for the employer brand is indisputable; particularly in service-intensive sectors. The brand message needs to be managed in the different touchpoints, as the employees represent the brand and place of work, and they offer a means for differentiation. Drawing from extant literature and integrating the findings of the exploratory study, we develop a conceptual framework (). The framework describes the holistic role of employees as co-creators and active performers in the employer branding process, both internally and externally. Thereby, we address the purpose of this study, i.e. to explore the role of the employees as both a target group and co-creators of employer brand equity in the context of tourism and hospitality.

illustrates that internal employer branding can be used to communicate the EVP and to build EBE (familiarity, associations, experience, and loyalty) among insiders, not only in retaining talent, but in using current employees to aid in the search for and recruitment of new employees. Employers offer and employees experience the work culture and social relationships, making insiders an important target market for employer branding activities (Alshathry et al., Citation2017). However, the social dimension in the experience cannot be fully controlled by the employer; rather, it is co-created by insiders. Similarly, as Von Wallpach et al. (Citation2017) discuss as brand performance and co-construction of brand identity in the case of LEGO, employees also have certain brand performances, of which some are unintentional in-role performances and others extra-role performances. The different employee performances show how co-creation of employer brand equity takes place and the roles each of them can take. These are summarized in .

Table 2. Employee performances and roles in co-creation.

Insiders are brand members who seek to negotiate and make sense of what they stand for as a collective group, perform in accordance with the (experienced) brand identity, and identify who would fit their shared experience. When asked about the values, many of the respondents were unsure of what they were. Expressed values were mostly connected to taking care of customers, but how they related to the employees’ own experience was not clear. The values were mainly discussed sporadically, or they were put on a poster, rather than discussed as guiding principles for the collective. Yet, the study indicated that there is a strong sense of “we”: what it means to be an insider and who would fit in as one. Recently, Auer et al. (Citation2021) suggested that potential employees tend to construct a subjective employer image based on previous work experiences and make sense of employer attributes through personal values and self-concept. Similarly, based on the exploratory interviews, it seems that also current employees make interpretations of what the employer (brand) is about, without having a clear understanding of the organization’s intended values. This also relates to Gjerald and Øgaard (Citation2010) discussion about employees’ basic assumptions about their work environment, for instance work relationships and role expectations. They further highlight that not all assumptions are positive, and to create change managers must make the assumptions visible. In addition, the employees seemed to draw conclusions of what type of a person would fit into the organization, based on their understanding of the employer brand and the experiences of the social collective. This is also similar to what Aggerholm et al. (Citation2011) refer to as negotiating the brand meaning. Therefore, active employer branding activities can guide the negotiation process, and clearly link values to employees’ basic assumptions.

The employees then represent the employer and the co-created EVP when interacting with outsiders (customers, friends, and others) as part of their role of being a brand representative, which was a role that the respondents discussed in detail, in particular connected to customers. Furthermore, they become active brand advocates when recommending the employer to others, while the perceptions of outsiders also shape the employees’ own attitudes about the organization as an employer. Some also discussed going the extra mile internally, attempting to influence the work and social collective. Interviewees mentioned the importance of helping each other and having free hands to improve work processes, which leads to inspiration, increased engagement, and a positive atmosphere. However, some also experienced that despite the efforts to influence, it was not always welcomed by colleagues, and in other cases the employers expected employees to get involved but did not reward this in any way. This type of voluntary internal extra-role behavior can be seen as the role of a corporate influencer. Hesse et al. (Citation2021) define this as “an employee who acts in the name of the corporate brand and positively influences its perception among stakeholders”, which internally refers to someone who “contributes to the formation of a sense of belonging and therefore creates room for the development of social identity” (p.193).

Plaskoff (Citation2017) suggests that the experience consists of multiple touchpoints which should be considered in detail. In their role as brand members or corporate influencers they contribute to creating internal associations about what is expected of the employees, which can have a great impact on the experience and even loyalty. The interviews suggest that the employee experiences affect their top-of-mind associations, and one single touchpoint, or an incident, can become a crucial determinant for the experience. Employees’ brand and organizational knowledge makes them an important asset as EBE builders and co-creators. The employees are a good source of employment information as they understand the needs of the company and who would “fit in”. As Backhaus (Citation2016) points out, there is no “right” employer brand, but the brand message must be communicated clearly in order to attract the right talent. Educating and reminding current employees of this message will not only explicitly build employer brand equity among insiders, but also implicitly, as employees act as co-creators by being brand members and representatives who create brand associations and creating familiarity towards outsiders. In addition, outsiders’ perceptions of the organization seem to be important as this tended to affect employees’ attitudes, such as feelings of pride.

The results of this study show that an employee can feel a sense of loyalty to the employer even after the employment ends. Hatch and Schultz (Citation2010) criticize the use of employee turnover as a measure of commitment, and state that HR professionals have begun to focus more on creating sustainable competitive advantage. Thus, the concept of loyalty regarding employer brands could be more nuanced, as it can entail much more than staying in the organization. It could be argued that a former employee can continue to portray brand loyalty, manifesting itself as brand advocacy. Thus, even former employees can be an important target group, as also suggested by App et al. (Citation2012).

6. Conclusions

Employer branding is often discussed as a strategy for finding employees who can represent the company positively towards customers. Most of the employer branding studies deal with recruitment, whereas internal branding perspectives focus on the customer journey. While internal branding is important especially in the hospitality context, less emphasis has been put into studying internal employer branding and working on brand values for the sake of the employee. The results from the exploratory interviews tell a similar tale. For example, discussions about what the company stands for were often directed into reflections about the importance of positive customer experiences, sometimes even connecting the value proposition to the physical environment and evidence. It seems that brand values are often discussed in the beginning of the employer/employee relationship, leaving the impact superficial. However, many of the interviewees said that they would like to see more discussions and applications of the values into their daily work. Stressing and clarifying the brand values seems to be important for employer retention: in a survey by Randstad (Citation2020), 35 percent of those who had recently switched jobs, or intended to do so, reported poor fit between organizational and personal values as a reason.

Thus, the internal employer branding perspective and management of the value proposition towards employees seem to be lacking in literature as well as in practice. It is certainly essential to educate employees about how they portray the brand towards the customer, but emphasis could also be put on activities that clarify how the brand, and the work itself, can create value to the employee. In addition, employees are often regarded as a target market instead of active co-creators in the current literature. Previous research shows that employees are part of the employer brand in different ways: as co-creators of values (Aggerholm et al., Citation2011; Smith, Citation2018) and as representatives of the social value (Berthon et al., Citation2005) and environment in their role as (potential) co-workers. They also portray intangible or psychological aspects of the social identity and employer brand; that is, they illustrate what being part of this particular collective represents to both insiders and outsiders. This study provides a more holistic understanding of how employer brand equity is co-created, due to the different roles and performances employees take: the brand member, brand representative, corporate influencer, or brand advocate.

6.1 Theoretical contributions and research implications

The co-creating role of employees has been studied in the tourism and hospitality literature (King et al., Citation2020). Employer branding literature has rather recently begun to discuss employees as co-creators (Aggerholm et al., Citation2011; Smith, Citation2018), but more research has been called for to create a more holistic picture (Auer et al., Citation2021), and viewing employer brand equity as a co-creation process (Saini et al., Citation2022). This paper contributes to the field of employer branding by proposing a framework for the role of employees as co-creators of the employer brand and EBE. In particular, it highlights the specific employee performances that co-create EBE. This relates to a recent discussion by Iglesias et al. (Citation2022), who suggest that co-creation research “should adopt a performative approach to corporate branding, where the key is to understand which stakeholder performances co-create the corporate brand” (p.8). While co-creation has been established in the corporate and service branding literatures, it is still scant in employer branding.

The study further adds to the body of knowledge by showing that employees do not need to fully understand the employer brand to feel committed or to become advocates. However, this means that the employees make an interpretation of the brand based on their experience with not only the employer, but also with the social environment, i.e. insiders and outsiders. The exploratory interviews strongly suggest that brand loyalty can manifest itself as brand advocacy that continues even after leaving; therefore, retention may not be suitable as a single measure of loyalty. Moreover, it seems that loyalty can be found on many levels: towards the employer overall, but not towards the local unit, or vice versa.

Lastly, this study contributes to the general calls for more research on employer branding in tourism and hospitality, including retail. These sectors are highly dependent on attracting and retaining the right employees to build a positive brand in the eyes of customers. The conceptual framework presented in provides a more holistic view on the important role that both current (internal) and former (external) employees play in attracting future employees, by communicating the employer value proposition (EVP) and, in doing so, developing long-term employer brand equity (EBE) for future, current, and even former employees of the organization. Such a framework not only guides further empirical investigation, but is open to evolving through such empirical work over time.

6.2 Practical contributions

The findings of this exploratory study suggest that it is difficult for employees to understand and make sense of how their employer’s brand values relate to them as employees beyond their role as service providers. The values therefore risk becoming merely words on a poster in the staff room. At the same time, employees seem knowledgeable about aligning different brand elements (for example “quality” and what the physical place itself communicates) and many wish for more discussions about brand values.

Organizations should create an EVP that is distinct from competitors and communicate it clearly throughout the employment experience. Through internal employer branding activities, it could be possible to offer an arena for meaningful discussions about the brand, and thus, increase the level of brand knowledge. This can be based on what both current and even former employees can offer. Designing organizational policies in accordance with the values can lead to an authentic experience and loyalty, and ultimately create employer brand equity. Employees should also be rewarded for their brand building efforts, and employees who have the potential to become corporate influencers or brand advocates should be supported by giving agency as well as resources to take on that role. They can also maintain a relationship to former employees, who can be encouraged to keep acting as advocates.

Employees tend to discuss their employment experience with others as well as to recommend the organization as a place of work; thus, more effort should be put into communicating the brand values internally. When the employees know what makes the employer unique, and more importantly, how the unique values are translated into daily activities, they become aware of how belonging to that particular organization creates value to them. In addition, it clarifies how to perform the brand both internally towards their colleagues as well as externally to customers and to future employees. It is important for managers to note that while they might be the owners of the brand on paper, they should invite employees to negotiate and collectively define the brand meaning. The employees together with the brand can then communicate an authentic message of the employment experience towards fellow insiders (current) employees, as well as to future employees.

This study also suggests that the relationship between employee and employer does not have to end when the employment ends, and therefore employers should try to stay connected with former employees. Seeing former employees as a special target market of the employer brand can help keeping them as employer brand advocates, providing stronger EBE as well. Considering the nature of work in the tourism and hospitality industry, with many short-term and seasonal employments, this becomes an important question, especially when considering last season’s employees may have left, but could either come back next season or recommend such employment opportunities to others.

6.3 Limitations and future research

The current study took an exploratory approach with in-depth interviews with 16 individuals in Sweden. While the aim was not to generalize, the sampling method can raise questions of representability, and the data collection involves risks for bias or interviewer effects. More research is therefore needed, both in terms of qualitative in-depth data in other settings and countries, and in terms of quantitative methods. Using larger samples and statistical analyses would also make it possible to test for influencing or moderating factors such as demographic or cultural differences.

Moreover, the study took its theoretical starting point in one specific framework, in which EBE is built on four dimensions (familiarity, associations, experience, and loyalty). Other frameworks and factors could be further developed and tested to better understand employees’ role in the employer branding process. Experimental design could allow evaluating different internal branding methods, and their effects on EBE. Future research should also investigate ways of maintaining relationships with former employees, and how this group can be incorporated into the employer branding strategies. As Theurer et al. (Citation2018) point out, employer branding as a field is still developing and more research is needed overall. Moreover, the role of employees in co-creation needs more research overall (Auer et al., Citation2021; Smith, Citation2018).

Interview_protocol_Appendix_to_reviewers.docx

Download MS Word (27.3 KB)Appendix_Table_quotes.docx

Download MS Word (32.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity. The Free Press.

- Abrams, D. E., & Hogg, M. A. (1990). Social identity theory: Constructive and critical advances. Springer-Verlag Publishing.

- Afshari, L., Young, S., Gibson, P., & Karimi, L. (2020). Organizational commitment: Exploring the role of identity. Personnel Review, 49(3), 774–790. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2019-0148.

- Aggerholm, H. K., Andersen, S. E., & Thomsen, C. (2011). Conceptualising employer branding in sustainable organisations. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 16(2), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563281111141642

- Alshathry, S., Clarke, M., & Goodman, S. (2017). The role of employer brand equity in employee attraction and retention: A unified framework. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 25(3), 413–431. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-05-2016-1025

- Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4(3), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.1996.42

- App, S., Merk, J., & Büttgen, M. (2012). Employer branding: Sustainable HRM as a competitive advantage in the market for high-quality employees. Management Revue, 23(3), 262–278. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2012-3-262

- Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/258189

- Auer, M., Edlinger, G., & Mölk, A. (2021). How do potential applicants make sense of employer brands? Schmalenbach Journal of Business Research, 73(1), 47–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41471-021-00107-7.

- Backhaus, K. (2016). Employer branding revisited. Organization Management Journal, 13(4), 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/15416518.2016.1245128

- Backhaus, K., & Tikoo, S. (2004). Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career Development International, 9(5), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430410550754

- Barrow, S., & Mosley, R. (2005). The employer brand: Bringing the best of brand management to people at work. [Book]. Wiley.

- Baum, T., Mooney, S. K., Robinson, R. N., & Solnet, D. (2020). COVID-19’s impact on the hospitality workforce–new crisis or amplification of the norm? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(9), 2813–2829. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2020-0314

- Berthon, P., Ewing, M., & Hah, L. L. (2005). Captivating company: Dimensions of attractiveness in employer branding. International Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 151–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2005.11072912

- Björk, P., Prebensen, N., Räikkönen, J., & Sundbo, J. (2021). 20 years of Nordic tourism experience research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1857302

- Bohlin, B., Algotson, K., Rosander, E., & Philp, T. (2017). Ett land att besöka: En samlad politik för hållbar turism och växande besöksnäring. Betänkande av Utredningen Sveriges besöksnäring ((SOU 2017:95)No. SOU 2017:95. https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2017/12/sou-201795/.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cable, D. M., & Turban, D. B. (2001). Research in personnel and human resources management. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 20, 115–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(01)20002-4

- Chhabra, N. L., & Sharma, S. (2014). Employer branding: Strategy for improving employer attractiveness. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 22(1), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-09-2011-0513

- Da Silveira, C., Lages, C., & Simões, C. (2013). Reconceptualizing brand identity in a dynamic environment. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.020

- Edwards, M. R. (2009). An integrative review of employer branding and OB theory. Personnel Review, 39(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481011012809

- Gehrels, S. (2019). Employer branding for the hospitality and tourism industry: Finding and keeping talent. Emerald Group Publishing.

- Gelb, B. D., & Rangarajan, D. (2014). Employee contributions to brand equity. California Management Review, 56(2), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2014.56.2.95

- Gilani, H., & Cunningham, L. (2017). Employer branding and its influence on employee retention: A literature review. The Marketing Review, 17(2), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1362/146934717X14909733966209

- Gjerald, O., Dagsland, ÅHB, & Furunes, T. (2021). 20 years of Nordic hospitality research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1880058

- Gjerald, O., & Øgaard, T. (2010). Eliciting and analysing the basic assumptions of hospitality employees about guests, co-workers and competitors. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(3), 476–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.11.003

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor.

- Goffman, E. (1967). On face-work, an analysis of ritual elements in social interaction. Interaction ritual, essays on face-to-face behavior. Aldine Publisher.

- Gregory, A. (2007). Involving stakeholders in developing corporate brands: The communication dimension. Journal of Marketing Management, 23(1-2), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725707X178558

- Hatch, M. J., & Schultz, M. (2010). Toward a theory of brand co-creation with implications for brand governance. Journal of Brand Management, 17(8), 590–604. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2010.14

- Hesse, A., Schmidt, H. J., & Baumgarth, C. (2021). How a Corporate influencer co-creates brand meaning: The case of pawel dillinger from Deutsche Telekom. Corporate Reputation Review, 24(4), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-020-00103-3

- Iglesias, O., Ind, N., & Schultz, M. (2022). Towards a Paradigm Shift in Corporate Branding (The Routledge Companion to Corporate Branding (pp. 3–23). Routledge.

- Iglesias, O., Landgraf, P., Ind, N., Markovic, S., & Koporcic, N. (2020). Corporate brand identity co-creation in business-to-business contexts. Industrial Marketing Management, 85, 32–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.09.008

- Kalińska-Kula, M., & Stanieć, I. (2021). Employer branding and organizational attractiveness: Current employees’ perspective. European Research Studies Journal, XXIV(1), 583–603. https://doi.org/10.35808/ersj/1982

- Keeling, K. A., McGoldrick, P. J., & Sadhu, H. (2013). Staff word-of-mouth (SWOM) and retail employee recruitment. Journal of Retailing, 89(1), 88–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2012.11.003

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101

- Kimpakorn, N., & Tocquer, G. (2009). Employees’ commitment to brands in the service sector: Luxury hotel chains in Thailand. Journal of Brand Management, 16(8), 532–544. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550140

- King, C., So, K. K. F., DiPietro, R. B., & Grace, D. (2020). Enhancing employee voice to advance the hospitality organization’s marketing capabilities: A multilevel perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102657

- Lashley, C. (2008). Studying hospitality: Insights from social Sciences. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 8(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701880745

- Lauver, K. J., & Kristof-Brown, A. (2001). Distinguishing between employees’ perceptions of person–Job and person–organization Fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59(3), 454–470. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1807

- Lewis, J. (2009). Redefining qualitative methods: Believability in the fifth moment. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800201

- Lievens, F., & Slaughter, J. E. (2016). Employer image and employer branding: What we know and what we need to know. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 407–440. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062501

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Minchington, B. (2010). Employer brand leadership: A global perspective. Collective Learning Australia.

- Moroko, L., & Uncles, M. D. (2008). Characteristics of successful employer brands. Journal of Brand Management, 16(3), 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2008.4

- Murillo, E., & King, C. (2019). Why do employees respond to hospitality talent management. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(10), 4021–4042. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2018-0871

- Piehler, R., King, C., Burmann, C., & Xiong, L. (2016). The importance of employee brand understanding, brand identification, and brand commitment in realizing brand citizenship behaviour. European Journal of Marketing, 50(9/10), 1575–1601. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-11-2014-0725

- Plaskoff, J. (2017). Employee experience: The new human resource management approach. Strategic HR Review, 16(3), 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-12-2016-0108

- Punjaisri, K., & Wilson, A. (2011). Internal branding process: Key mechanisms, outcomes and moderating factors. European Journal of Marketing, 45(9/10), 1521–1537. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561111151871

- Punjaisri, K., Wilson, A., & Evanschitzky, H. (2008). Exploring the influences of internal branding on employees’ brand promise delivery: Implications for strengthening customer-brand relationships. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 7(4), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332660802508430

- Randstad. (2020). Employer brand research 2020, Sweden (https://www.randstad.se/arbetsgivare/employer-brand-center/alla-rapporter/.

- Roulston, K., & Choi, M. (2018). Qualitative interviews. The SAGE handbook of qualitative data collection (pp. 233–249).

- Saini, G. K., Lievens, F., & Srivastava, M. (2022). Employer and internal branding research: A bibliometric analysis of 25 years. Journal of Product & Brand Management (ahead-of-print).

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Schlager, T., Bodderas, M., Maas, P., & Cachelin, J. L. (2011). The influence of the employer brand on employee attitudes relevant for service branding: An empirical investigation. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(7), 497–508. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041111173624

- Schneider, A., & Treisch, C. (2019). Employees’ evaluative repertoires of tourism and hospitality jobs. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 3173–3191. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2018-0675

- Smith, L. (2018). Storytelling as fleeting moments of employer brand co-creation [Dissertation, Aarhus University]. https://pure.au.dk/portal/files/143274123/Final_Text.pdf.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1985). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel, & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Hall.

- Tanwar, K., & Kumar, A. (2019). Employer brand, person-organisation fit and employer of choice. Personnel Review, 48(3), 799–823. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2017-0299

- Theurer, C. P., Tumasjan, A., Welpe, I. M., & Lievens, F. (2018). Employer branding: A brand equity-based literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(1), 155–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12121

- Tillväxtverket. (2020). Turismens årsbokslut 2019 [Annual report of tourism 2019]. (https://tillvaxtverket.se/statistik/vara-undersokningar/resultat-fran-turismundersokningar/2020-09-30-turismens-arsbokslut-2019.html.

- Törmälä, M., & Gyrd-Jones, R. I. (2017). Development of new B2B venture corporate brand identity: A narrative performance approach. Industrial Marketing Management, 65, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.05.002

- Valkonen, J., Huilaja, H., & Koikkalainen, S. (2013). Looking for the right kind of person: Recruitment in nature tourism guiding. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 13(3), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2013.837602

- Von Wallpach, S., Hemetsberger, A., & Espersen, P. (2017). Performing identities: Processes of brand and stakeholder identity co-construction. Journal of Business Research, 70, 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.06.021

- Wan, Y. K. P., Gao, H. Y., Eddy, U. M. E., & Ng, Y. N. (2023). Expectations and perceptions of the internship program: A case study of tourism retail and marketing students in Macao. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 35(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10963758.2021.1963753