ABSTRACT

The study combines popular culture tourism and regional development with contemporary toy and play research through “toyrism”, i.e. toy tourism. We focus on a specific form of popular culture and storytelling, the #instadoll phenomenon, involving fictional characters, namely fashion dolls, with personalised appearances and personalities narrated by their owners as players. Through netnography, we examine adult toy players’ participation in the #travelingdollpants online project to understand the co-creation process and meaning-making in the physical destination and digital play environment. Further, we examine how the #instadolls function as leisurely play (play for hedonic purposes) and playbor (play as productive work) and elaborate on whether “toyrism” can benefit destination development. By vicariously experiencing staycations in other players’ environments through #instadolls stories, relationships are formed between the Instagram followers and the destinations the dolls visit in the socially shared photoplay, or toy photography. The activity combines toys, physical destination environments, corporeal and imaginative mobilities, and socially shared performances, resulting in visual and serial storytelling. Through playification, the dolls as “toyrists” play a part in destination branding and may also become a strategic tool for tourism destination development.

Introduction

Popular culture and popular culture tourism are associated with entertainment and recreation, which are considered commercial and targeted to the masses (Lindström, Citation2018; Lundberg et al., Citation2018). Popular culture produces and circulates narratives created by people in contemporary society through, e.g. films, music, sports, video games, and events (Fiske, Citation2010; Lundberg & Ziakas, Citation2018; Reijnders et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, tourism is often compared to play and is all about consuming and producing narratives (Noy, Citation2012).

Although toys and play fall into the sphere of popular culture, scant research exists on toys and toy play in tourism (Heljakka & Räikkönen, Citation2021). Moreover, to our knowledge, no research connects toys and toy play to regional tourism development. Toys are commercial and romanticised objects promoting solitary play among children (Sutton-Smith, Citation1997) and social play and fandoms among adults (Heljakka, Citation2013). Here, we focus on adult toy play, which has become more visible due to new technologies and social media platforms. While toys and toy play form a creative outlet for adult players, such offers a valuable resource for storytelling. Mature audiences now perform and document play in physical environments and share their photoplay, i.e. toy photography or videography (see Heljakka, Citation2012) in digital playscapes, such as Flickr, Instagram, YouTube, or Facebook (Heljakka & Räikkönen, Citation2021).

Our study addresses “toyrism”, i.e. the emerging mobile and social play patterns associated with toys through the object-based but technologically enhanced practices of toy tourism (Heljakka & Räikkönen, Citation2021). Notably, in current tourism, toys can be traditional souvenirs traveling from destinations to new homes or toyrists traveling to and in destinations as protagonists of popular culture travel stories. We focus on a specific form of popular culture and storytelling: the #instadoll phenomenon involving fictional characters, namely fashion dolls with personalised appearances and personalities. We examine the Traveling Doll Pants online project (#travelingdollpants) as an example of a touristic doll drama, referring to serial and plotted toy stories communicated through social media platforms, including photographic, visual, and textual storytelling (Heljakka & Harviainen, Citation2019).

While the COVID-19 pandemic has prevented international tourism and physical mobility during the past years, it has increased vicarious tourism, i.e. experiencing tourism through someone or something else, such as a toy (cf. Robinson, Citation2014). Our study addresses domestic toyrism: fashion dolls on staycations. Still, the #travelingdollpants challenge investigated in our study has an international element, like the same pair of doll pants traveling to different countries where the #instadolls staycation while wearing the pants. Indeed, the #instadoll community has members from the Nordic countries, and #travelingdollpants have visited Nordic destinations such as Landskrona, Sweden (@mydollyclothes) and Turku, Finland (@elliefromfinland).

Through netnography (Kozinets, Citation2010; Citation2015), we analyse adult toy players’ participation in the #travelingdollpants online challenge to understand how #instadolls, as an example of toyrism, is linked to popular culture tourism and regional tourism development. Furthermore, we examine how creators and followers of doll dramas are involved in co-creation while participating in the meaning-making of the destination’s physical environment and the play environment on social media. Finally, we elaborate on how the #instadolls function as leisurely play (i.e. play for hedonic purposes) and a form of playbor (play + labor, Kücklich, Citation2005, i.e. play as productive work) that may play a part in destination development.

Regarding theoretical contribution, we widen the scope of tourism research to include various aspects of tangible play focusing on creative storytelling, meaning interactions, and engagement with material artifacts like character toys: dolls, action figures, and soft toys. Furthermore, we elaborate on how the leisurely play and productive playbor of adult toy players concerning #instadolls and storytelling linked to doll dramas play a part in destination development. The managerial implications highlight the increasing curiosity, interest, and visibility of character toys and adult toy play within social media networks and illustrate how various popular culture tourism phenomena can become powerful strategic tools with potential interest for tourism companies and destinations.

Theoretical framework

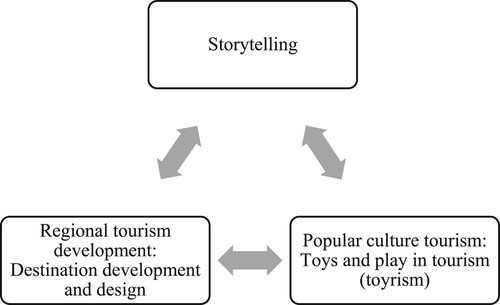

In this study, we illustrate how storytelling binds discussions on regional tourism development and popular culture tourism (). Storytelling transfers knowledge, enabling people to share their experiences and learn from others’ experiences (Hartman et al., Citation2019; Mandelbaum, Citation1991; Myers & Kitsuse, Citation2000). From a more strategic perspective, storytelling can be viewed as a normative, discursive, and political process of creating a story by articulating what is wrong, how it can be resolved, and how to convince or persuade actors to agree, unite, and engage in collective actions (Hartman et al., Citation2019; Van Dijk, Citation2011).

Regional development is a common theme in tourism research and is closely associated with strategic tourism planning. Traditionally, regional development has focused primarily on economic factors and regional innovation potential (Macbeth et al., Citation2004). Romão et al. (Citation2012), for instance, discussed regional tourism development through innovation, differentiation, and competitiveness but also sustainability, which has become an essential aspect of regional tourism development (Torres-Delgado & Saarinen, Citation2014). Volgger et al. (Citation2021) shifted destination development forward by adopting innovative ideas from design thinking that complements management and leadership through its holistic, open, human-centered, participatory, and transformational nature.

In turn, traditional forms of popular culture, such as films and music or sporting events, have dominated research on popular culture tourism (Fiske, Citation2010; Lundberg & Ziakas, Citation2018; Reijnders et al., Citation2021). Research on popular culture originates in cultural studies, sociology, media studies, and anthropology, and previous popular culture tourism research has often focused on destination or tourists’ perspectives (Lindström, Citation2018; Lundberg et al., Citation2018).

Toys and toy play have been researched in various disciplines, such as history, archaeology, anthropology, sociology, education, and design. While early research viewed toys mainly as historical artifacts and play as a children’s activity, the past decades have widened the scope to adult players and traditional disciplines intertwining with media, fan studies, and game research (Heljakka, Citation2013). However, research on toys and toy play in tourism (i.e. toyrism), although scarce (Heljakka & Räikkönen, Citation2021), represents an emerging research stream focusing on tourism beyond humans – robots, pets, and toys (Ivanov, Citation2019).

Storytelling and regional tourism development

According to Hartman et al. (Citation2019), storytelling has gained attention in regional development during the past decades, especially in strategic planning (Bulkens, Minca, & Muzaini, Citation2015; Van Hulst, Citation2012) and destination development (Mossberg, Citation2008; Olsson et al., Citation2016). In turn, regional tourism development has advanced from destination management (e.g. Laws, Citation1995), focusing on strategic goals and competitiveness, to destination governance (e.g. Ruhanen et al., Citation2010), focusing on processes and structures, and finally to destination leadership (e.g. Pechlaner et al., Citation2014), focusing on actors and values that shape destination networks (Volgger et al., Citation2021). In response to digitisation, climate change, changing mobility behaviors, and other current challenges, Volgger et al. (Citation2021) suggested an interdisciplinary approach – destination design – that better addresses the complexities of tourism development. For this study, the shift towards destination design is relevant as it more closely connects to experience design and destination branding – all building on storytelling.

Storytelling in tourism assumes that each destination has meaningful stories worth telling visitors (Ben Youssef et al., Citation2019). People have told stories about their places of origin and residence and where they have visited throughout time, illustrating how essential a sense of place is to human life (Bassano et al., Citation2019). Stories deliver entertainment and stimulate the imagination; they involve us emotionally and make our lives meaningful (Jensen, Citation1999; Lund et al., Citation2018; Mossberg, Citation2008). According to Sheldon (Citation2020), on the power of tourism to create meaningful experiences – and even inner transformations – storytelling and other creative encounters may enable moments of genuine interaction and deep connectivity. Stories that inspire and transform can highlight personal, cultural, and historic diversity or create an awareness of common humanity and unity among people (Sheldon, Citation2020).

Stories also create word-of-mouth and buzz about tourism destinations (Ben Youssef et al., Citation2019; Hsiao et al., Citation2013). Social media provides a space for storytelling and elevates the role of consumers in co-creating destination brands. According to Bassano et al. (Citation2019), storytelling is a strategic, multi-level process with a role in defining a place’s reputation, enhancing its competitiveness, and embellishing its meaning. Thus, they argue that storytelling about places should be managed to support local government in marketing and communications activities and involve local stakeholders in building place identity. In tourism destinations, storytelling is used in, e.g. sharing specific place goals; spreading and justifying place values; increasing tourist motivation; maintaining memories; creating trust, confidence, and sense of belonging; sharing tacit knowledge, norms, and values; reformulating place stories; and reengineering place image narratives (Bassano et al., Citation2019; Denning, Citation2005).

Ben Youssef et al. (Citation2019) approached storytelling from the branding perspective to determine how destination management organisations can identify the thematic content, strategic purposes, and anticipated impacts of storytelling. Based on interviews, they grouped the content and effects of storytelling into three dimensions (cf. Lavidge & Steiner, Citation1961, p. 1) cognitive dimension – developing destination attributes, associations, and image, stimulating destination visibility, awareness, attention, recognition, remembrance, inspiration, and interest, 2) affective dimension, i.e. destination identity, authenticity, and uniqueness – creating identification, empathy, trust, passion, and arousal, and 3) conative dimension – relating to destination’s hospitality and sustainability, developing advocacy in tourists.

Finally, Hartman et al. (Citation2019) argued that using strategic storytelling for destination development requires engaging in a possibly long-term transition involving potential initiators, i.e. signifying agents, that can mobilise resources for storytelling. Furthermore, they concluded that for consideration as a development catalyst, storytelling’s potential contribution to destination development must be understood by all actors on multiple levels, and the stories must create bridges between them. Moreover, the stories must be actively produced, materialised, disseminated, evaluated, and adjusted to support organisational structures.

Storytelling and toy play

Toys and toy play have become a creative outlet for adult players to engage in storytelling. The players simultaneously operate in the physical world and the ecosystem of contemporary play (Heljakka, Citation2016a) through creative acts involving physical objects (playthings) and digital communication technologies (tools) distributed through online platforms (networks). While playing, the players tell stories to themselves; this is how homo ludens, i.e. the playing human, becomes homo narrans, i.e. the storytelling human (Kalliala, Citation1999, p. 62; orig. Geertz Citation1973, Citation1993). Furthermore, players constantly participate in creatively refining their toys’ physical forms by customising and personalising them and cultivating meanings by recreating, replaying, and even retelling the stories connected to their playthings.

Kudrowitz and Wallace (Citation2008) identified storytelling play as a specific category of play, but when storytelling involves toys, it becomes a form of object play. Adult toy players are interested in various toys, such as miniatures, toy vehicles, and construction sets. Still, the most visible form of adult play in contemporary social media is adult toy play with character toys, i.e. dolls, action figures, figurines, and soft toys.

Unlike dolls of the past, the current character toys encourage fantasy play with pre-written personalities and storylines that supposedly discourage children from inventing original play worlds (Chudacoff, Citation2007). This so-called backstory relates to the toy character’s personality, offering cues about the character’s name, place of origin, and attitude towards life, and occasionally more detailed information, such as personality traits or moods (Heljakka, Citation2013, p. 165). Vartanian (Citation2006, p. 34) states, “People want to understand who the character is” to illustrate the significance of the backstory in designer vinyl, i.e. toys designed especially for adults.

The backstory can transform the symbolic play context into a narrative form. The queen of popular toy culture, the Barbie doll, provides a model example (Kline, Citation1993, p. 170). Barbie – Barbara Millicent Roberts – is a legend in the global “dolldom” as the first mass-produced fashion doll with an adult body sold and targeted to teenage girls. Barbie debuted at the New York Toy Fair in 1959 but still dominates the Western world’s mass-market doll category. As del Vecchio (Citation2003, 94) argues, “While baby dolls are about caring for someone else, the Barbie doll is about caring for your aspirations.”

In the experience and meaning economy, creating and staging novel, compelling stories for people to experience seems more important than designing actual artifacts. Crossley (Citation2003, p. 35) noted that “the story side of the product has become an ever-important part of the decision to buy.” In toy design, achieving characters with enduring play potential, the backstory should not be complete but must allow the player to create their own ideas about the toy and its world. Moreover, a critical part of the play with toy characters is the story that develops around the plaything during play. Although the backstory gives the toy a reason for being (Miller-Winkler, Citation2009, p. 19), the story the toy player creates breathes life into the toy, keeping it vividly alive in the player’s imagination. Michael Shore, Mattel’s vice-president of global consumer insights, stated about the Monster High doll series that “Fans can create and design their own characters, story settings, and story extensions” (Sullivan, Citation2013).

Documenting play through photoplay

Toys’ play value is determined by their physicality, functionality, fictionality, and affective dimensions (Heljakka, Citation2018 in Paavilainen et al., Citation2018). Still, the player is the one to actualise the toy’s multidimensional potential by actively participating in the value co-creation processes through various play scenarios. One way of capturing the play value is to document the play activity through toy photography, conceptualised as photoplay (Heljakka, Citation2012). Previous research on adult toy play has indicated that mimetic practices such as photoplay manifest a significant play pattern for most toy fandoms (Heljakka, Citation2013). Thus, play in the twenty-first century is not just technologically enhanced but is a vision-based practice tied with digital photography and sharing on social media.

Displaying toys is common in toy cultures among children and adults. Toys’ physical properties, such as portability and “poseability,” enable players to portray their toys in various real-world environments. This juxtaposition often occurs indoors, but the toy industry also encourages players to engage in experimental play outside the intimacy of domestic space. Certain toy characters even encompass a “wanderlust” – a curiosity to see the world outside and travel to destinations near and far – and be documented in these touristic realms.

Besides photoplay, designing, creating, and sharing displays, dioramas, and doll dramas enable adult players to engage in object interactions through manipulation, customisation, and storytelling. Adult toy play is manifested and materialised but documented through cameras and smartphones by photographing, filtering, narrating, and sharing play practices. Thus, the toy play experience involves playful interactions mediated on various platforms, such as natural and urban environments, private spaces, built environments, and social media play environments.

#Instadolls as storytellers, social media influencers, avatars, and tourists

Dolls are anthropomorphised, i.e. given human-like features, which is critical for storytelling (Hutson, Citation2012). Most often, #instadolls are mass-produced, Barbie-type fashion dolls with made-to-move bodies, high-level articulation, and sometimes customised or personalised facial features and hair. Artist Laurie Simmons, who explores dolls through photographs, has argued that a doll’s expression never changes, making it a blank screen for projecting different feelings (Colman, Citation2004). However, current adult toy players increasingly use digital apps to alter dolls’ expressions within the photoplay, enabling various emotions to be projected into the toy photography. In this way, mobile devices and apps add more possibilities to display affections during play.

Like humans, #instadolls can be considered storytellers whose personal and unique stories provide differentiation and are hard to copy. Emotional and personal storytelling is a powerful tool for socialising and creating influence; thus, #instadolls can be considered social media influencers (cf. Lund et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, #instadoll stories are often based on personalised representations of fashion dolls like Barbie, which sometimes function as their players’ avatars, extending the player’s identity into the toy (Heljakka, Citation2012).

In this study, our attention turns from the “dollfies” (doll self-portraits) to instances of toy tourism, i.e. toyrism (Heljakka, Citation2013; Heljakka & Räikkönen, Citation2021). In human and beyond-human tourism, stories provide an escape from everyday life. However, tourists (or toyrists) must step out of the ordinary for a story to captivate them. Different cultures and locations provide material for such powerful narratives, but storytelling can bring the extraordinary to domestic tourism and staycations. Nevertheless, mesmerising content is critical as we are drawn along by the stories and spellbound by the content, which is not necessarily accurate but believable (Mossberg, Citation2008).

Like fashion dolls, #instadolls are often customised with a personal style and highly detailed environments. They travel with accessories, pets, and other dolls, adding a personal touch to the narratives they create about destinations. In recent times, these travel stories have emerged more profoundly, framed by staycations in familiar settings during which the dolls and their players enjoy their hometown’s offerings. A recent example of Instagram fame is a forerunner to the emerging #instadolls phenomenon involved in staycations and other toyrism experiences – the Socality Barbie (Citation2015):

Socality Barbie had, in its heyday in 2015, 1.3 million followers on Instagram. In September 2015, Socality Barbie (also known as Hipster Barbie) had been acknowledged in various publications related to fashion and lifestyle and became a social media phenomenon. Wired magazine described the doll project as “a fantastic Instagram account satirising the great millennial adventurer trend in photography.” It’s an endless barrage of pensive selfies in exotic locales, arty snapshots of coffee, and just the right filter on everything. (Glascock, Citation2015. n.p. cited first in Heljakka & Harviainen, Citation2019, p. 370).

#Instadolls as playborers of digital storytelling

According to Elkind (Citation2007), humans are a story-loving species. Indeed, tourism destination design relies on humans’ ability to tell stories and enjoy listening to storytelling. People – residents and tourists – often develop a deep love for their unique places and, through digital media, share their stories and motivate others to visit and experience them. Digital-age storytelling has become increasingly crucial as destinations compete for tourism and economic development (Bassano et al., Citation2019). Digital place storytelling communicates about regions through anecdotes, experiences, and stories shared with stakeholders (Hagen, Citation2008). While Bassano et al. (Citation2019) highlighted that the communication must align with the region’s value proposition and destination brands, Lund et al. (Citation2018) argued that rather than marketing strategies, destination brands should be viewed as products of people’s shared tourism experiences and storytelling in social media networks (Lund et al., Citation2018). Technologies of power, including storytelling, performance, performativity, and mobility, illustrate how online social networks generate engagement and stimulate the circulation of brand stories (Lund et al., Citation2018).

Digital storytelling is inherently interactive (Long, Citation2007) and somewhat hard to harness or direct. Human efforts, including play, are directed towards creating meaning, and a narrative is one form that meaning can take (Frost et al., Citation2005). Thus, toys should be considered with other stories or as part of different narratives. In this light, toys are narrative artifacts (Selander, Citation1999) – intertextual and intermedial regarding domestic and international tourism narratives.

According to Heljakka (Citation2013), a critical feature in contemporary toy cultures is players telling their own stories about the toys’ adventures in digital media. The toy world is constantly growing across social media, where toy stories continue in various textual, pictorial, and serial forms. Moreover, toys have become a notable medium through the new media, enabling the sharing of all kinds of stories quickly and efficiently. The toy as a tool tells players a story and allows fans and players to tell theirs. While many games are somewhat structured, the openness of toys means players are free to create extended and alternative storylines, such as various personalities and stories for their toy characters. These toy stories may emerge from the toy’s or the player’s own characteristics or the circumstances experienced in interacting with the toy.

Recent research positions adult players as playborers who produce entertaining, interactive, and informative content (e.g. toy photography, photoplay, or videos) for others to consume (Heljakka, Citation2021). The photoplay by adult toy fans functions as evidence of affective archiving of play culture and mediators of play knowledge – information on how toys are employed in playful engagement (Heljakka, Citation2022). To better grasp the often ephemeral instances of toy play and its value for adult experiences requires inspection of how and in what context the toy has been used and refers primarily to information related to play patterns.

Notably, toy characters have become such a platform for creative expression, identity construction, and storytelling that extending the concept of the contemporary doll in the direction of construction toys is possible (Heljakka, Citation2013), meaning that dolls have evolved into physical, functional, and fictional building blocks for story-driven play, complementing real-world environments and digital technologies.

#Instadolls on staycations: a study of the traveling doll pants

Research data and method of analysis

Our research design relies on netnography (Kozinets, Citation2010; Citation2015) – an online adaptation of ethnography – and a traditional anthropology technique based on participant observation. Although netnography has become a popular tool for examining the contingencies of online communities and cultures, not all investigative research on the Internet equals netnography (Costello et al., Citation2017; Lugosi et al., Citation2012). Netnography often includes multiple data sets, such as observing participant behavior and communication in an online community and engaging in qualitative in-depth interviews with community members and other key stakeholders (Brodie et al., Citation2013; Füller et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, netnography can be active or passive, short – or long-term, and focus on single or multiple communities (Costello et al., Citation2017).

According to Tuikka et al. (Citation2017), netnography can be ethically conducted by considering the need to request the online community members’ informed consent, protect their anonymity, and practice accountability. Here, we told the creators and moderators of the #instadolls online project about our study and requested their consent to use their photoplay for research. The human subjects behind each doll are on a public website, making anonymisation unnecessary. Finally, the accountability of our research lies in acknowledging the rich and multifaceted play of the doll enthusiasts behind the project and ensuring we treat their creations respectfully.

The research data focuses on a global community of adult toy players who employ fashion dolls in their popular storytelling of staycations, which are socially shared as part of a play project: #travelingdollpants. The first author is an established researcher of adult toy cultures and communities and has closely observed the emergence and evolution of doll dramas and the #travelingdollpants project on the Internet and social media. For this study, the first author collected textual and visual data from the Traveling Doll Pants website (2022) and the 150 Instagram posts on @travelingdollpants.

The research data were analysed with a textual content analysis focusing on firsthand observations of the critical components of the #dolldrama phenomenon in general and on #travelingdollpants in particular. Content analysis is a widely used method in tourism and popular culture studies to reveal patterns in research data, which can consist of textual or audiovisual material (Allen, Citation2017). The first author examined the kinds of written messages (verbal elements) the players had included in the posts accompanying their photoplay. Then she coded and categorised these elements into themes such as “Toy photography”, “Play experience”, and “Travel & tourism”. In turn, the visual content analysis focused on where (indoors or outdoors) and how the dolls were displayed (posed) and whether one or several dolls were in the photograph. Furthermore, she identified recognisable elements of visible storytelling in the posts, such as combined sceneries and tourist sites, props, and clothing (visual elements).

Traveling doll pants

Adult toy play is a collective and co-creative activity containing goal-oriented projects and challenges that often include storytelling. Many of these structured play patterns involve the mobility of toys, which intermingles with shared storytelling among adult players. In toyrism, the fantastic fiction of storytelling with toys meets the nonfiction of human life. The Instagram account Traveling Doll Pants names itself as “the official profile of the Traveling Doll Pants project”. The project’s creators, Patricia Marcos Coutsoucos and Izabela Kwella, describe it as follows:

The Traveling Doll Pants is an international project connecting doll photographers and enthusiasts from all over the world. […] The project is the brainchild of Brazilian doll collector Patricia Marcos Coutsoucos (@dressthatdoll) and Polish doll photographer Izabela Kwella (@bella_belladoll).

Like many toy-related projects circulating on social media, the #travelingdollpants project centers on photoplay – creative practice with seemingly unlimited possibilities for skill-building and storytelling. Photoplay is an essential outlet for players to use their creativity concerning travel. Photoplay with #instadolls reveals how creative adult players are in finding interesting photographic vantage points and accessorising dolls with miniature props, such as the bicycle in a photo by Henna Kiili (see ). A repost from @elliefromfinland player Henna Kiili accentuates how toy photography conducted outdoors “made her bloom”:

travelingdollpants Reposted from @elliefromfinland MY FINAL PHOTOS OF #TRAVELINGDOLLPANTS are here [image of Finnish flag] Swipe photos [image of Finnish flag] THANK YOU ALL! [image of blue heart] This has been such a great experience. I do this all the time, but I think this project has made me bloom with outdoor photos! [image of the camera]

Figure 2 . An example of #instadolls taking part in the #travelingdollpants challenge. Photograph presented with permission from the player, Henna Kiili.

travelingdollpants Reposted from @bella_belladoll Do you know what I love the most about #travelingdollpants project? It involves my favorite type of doll photography – the outdoor photography – and the fact that I will be able to show you my favorite places in my beautiful city Gdansk @gdansk_official

The goal is to show 11½ inch dolls (Barbie, Integrity Toys) wearing the same pair of pants in different countries, presenting interesting places where the doll collectors live. Joanna Fila-Staskiewicz (@kameliadolls) created a pair of pants for this project. Like in the bookend [sic] movie, the pants travel all over the world from one participant to the other. Each featured participant takes as many pictures of their city within a time frame of three weeks, showing their part of the world.

Regarding play, the project represents the physical mobility of objects, i.e. mobile object play. The #travelingdollpants challenge defines itself as a travel-and-fashion project and, at the time of research, suggested using the following hashtags associated with the Instagram posts: #travelingdollpants, #stayathomedollpants, #dollphotography, #dollphotos, #dollphoto, #barbie, #barbiedoll, #dolls. Besides allowing doll personalities to be captured on camera, the project’s fashion aspect is meaningful for the players. Throughout history, clothing has distinguished one doll from another (Coleman et al., Citation1975). Historically, the clothes represented the doll’s primary purpose and provided the greatest fascination (Coleman, Citation1975). Indeed, Barbie’s first profession was a fashion model. Thus, it is unsurprising that the doll inspires players to engage with the latest fashion and lifestyle trends, such as the prominent emergence of staycations as a concept related to human travel. Instead of promoting excess consumption of new accessories or extensive wardrobes for the dolls, the focal point for the #travelingdollpants project is a singular and shared piece of doll clothing:

travelingdollpants Reposted from @la_doll_cevita This is the official kick-off for my #travelingdollpants part! I will post 3 pictures every day from my beautiful City of Berlin. But, in between I will show you some outfit ideas with jeans too. As you all know from real life you can wear everything with a good pair of jeans. So I thought it would be also fun and maybe an inspiration for you to add some outfit of the day with the girls then will wear outside, showing you around.

Figure 3 . The traveling doll pants. Photograph presented with permission from the Traveling Doll Pants project.

travelingdollpants Reposted from @la_doll_cevita Luke is entering the room with a big package. “Girls!!! Did you ordered [sic] something from Poland [image of Polish flag]??? There was a package for you on the doorstep. What the heck?” The girls are giggling and laughing because they did not ordered [sic] anything but they all know what this package from Poland means: THE PANTS are finally here! [image of blue heart and jeans]

travelingdollpants Reposted from @la_doll_cevita Since you enjoyed my last post about modern Berlin so much I have some fun facts for you too: With almost 200 museums, Berlin is said to have more museums than rainy days a year. Berlin has a total of 9 castles. Berlin has more bridges than Venice – around 1,700 of them. It is also said that Berlin has more waterways than Amsterdam, Stockholm, and Venice combined (180 kilometers). If you’d like, you can spend hours and hours going around town by boat. Berlin is considered by many as Germany’s greenest city, with over 44% of its area made of waterways, woods, rivers, and green areas. All public transport together travel around the world 8.7 times a day. You will find a public transport stop with a radius of 500 meters. Only ¼ all Berlier are real Berliner (born in Berlin), I am one of them. Around 60 million currywurst are eaten in Berlin every year, and about 60 tons of doner kebab meat a day! [image of blue heart and jeans]

Covid-19 has affected us all, particularly in terms of travel, and its resolution is not imminent. We’d like to share some positivity during this strange time, by sharing with you our intrepid little travel-and-fashion project that has now been seen by thousands of Instagram users around the world. (The Traveling Doll Pants Website)

Discussion: #instadolls in popular culture tourism and regional development

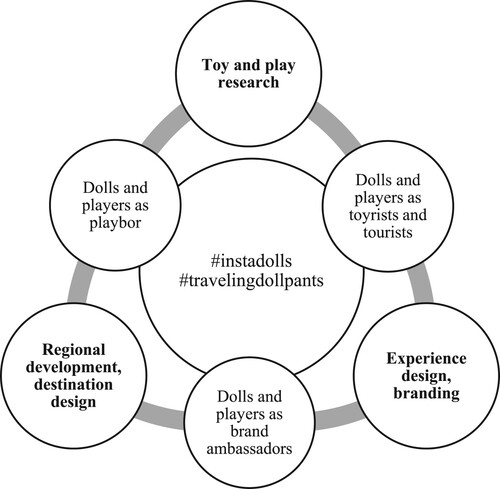

This study addressed popular culture tourism and regional development through the lenses of the #instadoll phenomenon in general and #travelingdollpants in particular. As illustrated in , we identified three specific roles for the dolls and their players: 1) dolls and players as toyrists and tourists, 2) dolls and players as playborers, and 2) dolls and players as brand ambassadors.

Figure 4 . The roles of the #instadolls and their players in relation to popular culture tourism and regional development

As open-ended playthings, toys offer ample possibilities for creative storytelling concerning tourism destinations. There are seemingly no rules or limitations to leisurely play with the dolls in the tourism setting. The #travelingdollpants case suggests that adult toy players use fiction, storytelling, and play – all signifying popular culture (cf. Fleming, Citation1996). Moreover, the case further develops previous conceptions of the emerging phenomenon of toy tourism, i.e. toyrism (Heljakka & Räikkönen, Citation2021). Fictional characters, such as the #instadolls this article examines, can facilitate players’/tourists’ immersion in a story, similar to involvement and co-creation (Mossberg, Citation2008). Moreover, social media has dramatically transformed the practices of tourism and toy play during the past years, especially considering the staycation trend, thus steering the focus to proximity tourism (Romagosa, Citation2020). Arguably, especially amidst the pandemic, participating in or following a global project like #travelingdollpants with other “instadoll enthusiasts” could enable meaningful experiences through genuine interaction and deep connectivity, creating awareness of shared humanity and unity (cf. Sheldon, Citation2020).

Fundamentally, the adult toy players, as doll play practitioners, directly participate in the co-creation of experience design, destination design, and branding. Thus, #travelingdollpants represents a case of playbor related to toy play (Heljakka, Citation2021), in which the adult toy players are involved in productive play and creative labor, offering entertaining yet informative photoplay for other doll enthusiasts to enjoy as part of the doll dramas produced as travel and fashion stories. In tourism destinations, storytelling has been used to spread place values, reformulate place stories, increase tourist motivation, maintain memories, and reengineer place image narratives (Ben Youssef et al., Citation2019). Our study contributes to this discussion by describing how these strategies materialise in story-driven adult toy play, centering on doll dramas. Indeed, these instances of toy play narrate toy tourism through documented play and online sharing. Arguing that the players could act as signifying agents and doll dramas could directly benefit regional development and strategic tourism planning would be an exaggeration. However, as storytelling and design thinking have already entered regional development, it can be speculated that deliberate playification (Scott, Citation2012) would bring new ideas and tools for strategic destination development.

Our study also reveals how the storytelling of doll dramas on social media intertwines with the storytelling of official tourism destination branding through cognitive, affective, and conative dimensions (Ben Youssef et al., Citation2019). In the #travelingdollpants, the players actively participate in developing the cognitive dimension by producing positive imagery that stimulates destination visibility and awareness, as well as inspiration and interest once shared on social media. In turn, the affective dimension draws on destination identity, authenticity, and uniqueness to create passion and arousal toward the destinations within the target audiences. The #instadolls players seem to express affection towards their local environment through passionate posts from their hometowns. Finally, the destination’s hospitality and sustainability are described in the conative dimension that incites tourists to develop advocacy for the destination. The primary purpose of #instadolls and #travelingdollpants is certainly not to make other players visit the destinations but to raise awareness and narrate personal playing in terms of entertaining yet informative content for other players to consume and enjoy. Still, many players included fun facts and travel tips to create interest and positive word-of-mouth behavior, which we interpreted as playification (Scott, Citation2012). Furthermore, as the #instadolls mainly exist on social media, they are bound to generate engagement and stimulate the circulation of brand stories regarding storytelling, performance, performativity, and mobility (cf. Lund et al., Citation2018).

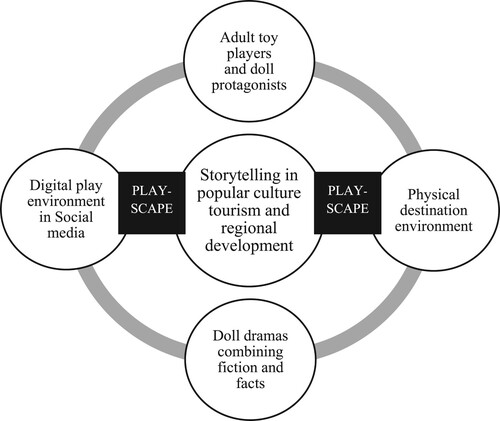

By combining the theoretical ideas on tourism destination development with the aspects of toy play as representing popular culture (), we propose that the #instadoll phenomenon and #travelingdollpants project demonstrate a hybrid and social play pattern regarding the following:

Mobility of playthings and players: international traveling of the pants and local staycations of the #instadolls

Playscapes: fashion – and tourism-oriented object play in the physical environment (place) shared through photoplay in digital playscapes (space)

Popular storytelling: factual landscapes of the destinations and their official brand stories combined with the fictional content of doll dramas

Figure 5 . Hybrid and social play pattern promoting “toyrism” in digital and physical tourism environments.

Although our study is on the margins of popular culture tourism, it provides a glimpse of how character toys and adult toy play may contribute to scientific understanding and managerial practices of tourism destination development and branding. Still, we argue that toyrism as a popular culture tourism phenomenon exists and will likely become more visible in tourism branding and regional development involving non-human tourism. Accordingly, we believe substantial potential exists for future research related to toy play in various streams of tourism research. Furthermore, #instadolls and other social media projects involving character toys open novel avenues for research, e.g. analysing whether photoplay and storytelling in social media follow the official storylines described in the brand manuals of tourism destinations.

Conclusions

The current study examined adult toy players’ participation in the #travelingdollpants online challenge. We aimed to investigate how doll dramas connect to popular culture tourism and regional tourism development. More precisely, we analysed 1) how creators and followers of doll dramas were involved in co-creation while participating in the meaning-making of the destination’s physical environment and the play environment on social media, and 2) how the #instadolls functioned as leisurely play (i.e. play for hedonic purposes) and a form of playbor (i.e. play as productive work) with a role in destination development. The empirical study addressed the #instadoll phenomenon, involving fictional characters, namely fashion dolls, participating in the Traveling Doll Pants online project (#travelingdollpants), illustrating a form of adult toy play and a touristic doll drama driving forward a deliberate playification process.

The findings suggest that, although rarely discussed in popular culture tourism research (cf. Lundberg & Ziakas, Citation2018), toys and adult toy play form an essential and increasingly visible part of popular culture. Through vicariously experiencing staycations in other players’ environments through the #instadolls stories, relationships develop between the Instagram followers and the places the dolls visit in the photoplay. The activity combines toys, physical destination environments, corporeal and imaginative mobilities, and socially shared performances, resulting in visual and serial storytelling, which we argue can become a strategic tool for destination development seeking to immerse tourists in powerful storytelling.

The study demonstrates how successful destination strategies might manifest as a play-based and co-creative practice through popular storytelling, employing toys, destination development, and structured play projects serving leisurely and productive purposes, i.e. intrinsically motivated open-ended play and extrinsically framed playbor. Thus, the study supports previous theoretical and empirical evidence (Lindström, Citation2018; Lundberg et al., Citation2018) on popular culture’s capacity – here, the dolls as toyrists or even toyrguides – to boost destination development. The toys and players show their local areas in an attractive and favorable light as places with intriguing potential for tourism – and toyrism – experiences.

Perhaps most importantly, the #travelingdollpants tells the story of doll dramas, narrating tourism experiences and destinations in challenging and uncertain times, when traveling needs to change or be reinvented. There is a saying, “where there is play, there is a way,” which, through creative adult toy players, manifests as communal, co-creative, and mobile toy play patterns that cannot be hindered by current or future crises. Notably, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the players’ creativity and resourcefulness resulted in the mobilisation of the pants and not the dolls, as in usual occasions of traveling toys:

In the first edition of the Traveling Doll Pants, held in 2020, the participants encountered pandemic lockdowns, and yet the pants still managed to travel from Poland to Germany, Russia, Finland, Canada, the USA, and Brazil. During the time when global travel was incredibly restricted, this project has become a virtual, visual way of satisfying one’s wanderlust. (Traveling Doll Pants website)

Research data

Traveling Doll Pants Instagram (2022). https://www.instagram.com/travelingdollpants/

Traveling Doll Pants Website (2022). http://travelingdollpants.com/

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allen, M. (2017). The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. SAGE publications.

- Bassano, C., Barile, S., Piciocchi, P., Spohrer, J. C., Iandolo, F., & Fisk, R. (2019). Storytelling about places: Tourism marketing in the digital age. Cities, 87, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.12.025

- Ben Youssef, K., Leicht, T., & Marongiu, L. (2019). Storytelling in the context of destination marketing: An analysis of conceptualisations and impact measurement. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 27(8), 696–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2018.1464498

- Brodie, R., Ilic, A., Juric, B., & Hollebeek, L. (2013). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.029

- Bulkens, M., Minca, C., & Muzaini, H. (2015). Storytelling as method in spatial planning. European Planning Studies, 23(11), 2310–2326. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2014.942600

- Chudacoff, H. P. (2007). Children at play. An American history. New York University Press.

- Coleman, D. S. (1975). The collector’s book of dolls. Doll Reader, 3(June 1975), 11.

- Coleman, D. S., Coleman, E. A., & Coleman, E. J. (1975). The collector’s book of dolls’ clothes: Costumes in miniature, 1700–1929. Crown.

- Colman, D. (2004). The unsettling story of two lonely dolls. New York Times, Oct 17. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/17/fashion/the-unsettling-stories-of-two-lonely-dolls.html

- Costello, L., McDermott, M. L., & Wallace, R. (2017). Netnography: Range of practices, misperceptions, and missed opportunities. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917700647

- Crossley, L. (2003). Building emotions in design. The Design Journal, 6(3), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.2752/146069203789355264

- del Vecchio, G. (2003). The blockbuster toy! How to invent the next big thing. Pelican Publishing Company.

- Denning, S. (2005). The leader’s guide to storytelling: Mastering the art and discipline of business narrative. John Wiley & Sons.

- Elkind, J. (2007). The power of play. Da Capo Press.

- Fiske, J. (2010). Understanding popular culture. Routledge.

- Fleming, D. (1996). Powerplay. toys as popular culture. Manchester University Press.

- Frost, J. L., Wortham, S. C., & Reifel, S. (2005). Play and child development (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River.

- Füller, J., Jawecki, G., & Mühlbacher, H. (2007). Innovation creation by online basketball communities. Journal of Business Research, 60(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.09.019

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures (Vol. 5043). Basic books.

- Geertz, C. (1993). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays ([New ed.]). Fontana.

- Glascock, T. (2015). “Hipster barbie is so much better on instagram than you.” Wired, Sept. 3, http://www.wired.com/2015/09/hipster-barbie-much-betterinstagram/

- Hagen, O. (2008). Driving environmental innovation with corporate storytelling: Is radical innovation possible without incoherence? International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 3(3-4), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJISD.2008.022227

- Hartman, S., Parra, C., & de Roo, G. (2019). Framing strategic storytelling in the context of transition management to stimulate tourism destination development. Tourism Management, 75, 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.04.014

- Heljakka, K. (2012). Aren’t you a doll! toying with avatars in digital playgrounds. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 4(2), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.4.2.153_1

- Heljakka, K. (2013). Principles of adult play(fulness) in contemporary toy cultures. From wow to flow to glow [Doctoral dissertation]. Aalto university.

- Heljakka, K. (2016a). Strategies of social screen Play(ers) across the ecosystem of play: Toys, games and hybrid social play in technologically mediated playscapes, Wider Screen 1–2/2016, http://widerscreen.fi/numerot/2016-1-2/strategies-social-screenplayers-across-ecosystem-play-toys-games-hybrid-social-play-technologically-mediated-playscapes/

- Heljakka, K. (2016b). Toying with twin peaks: Fans, artists and re-playing of a cult-series. Series. International Journal of TV Serial Narratives, 2(2), 2016. https://series.unibo.it/article/view/6589

- Heljakka, K. (2018). Re-playing legends’ worlds: Toying with star wars’ expanded universe in adult play. Kinephanos, 8(1), 98–119.

- Heljakka, K. (2021). From playborers and kidults to toy players: Adults who play for pleasure, work, and leisure. In M. Alemany Oliver, & R. W. Belk (Eds.), Like a child would Do. An interdisciplinary approach to childlikeness in past and current societies (pp. 177–193). Universitas Press.

- Heljakka, K. (2022). Fans, play knowledge, and playful history management. Transformative Works and Cultures, 37. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2022.2111

- Heljakka, K., & Harviainen, J. T. (2019). From displays and dioramas to doll dramas: Adult world building and world playing with toys. American Journal of Play, 11(3), 351–378.

- Heljakka, K., Harviainen, J. T., & Suominen, J. (2017, September). Stigma avoidance through visual contextualisation. Adult toy play on photosharing social media. New Media & Society, 20(8), 2781–2799.

- Heljakka, K., & Räikkönen, J. (2021). Puzzling out “Toyrism”: Conceptualizing value co-creation in toy tourism. 38, 100791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100791

- Hsiao, K.-L., Lu, H.-P., & Lan, W.-C. (2013). The influence of the components of storytelling blogs on readers’ travel intentions. Internet Research, 23(2), 160–182. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662241311313303

- Hutson, M. (2012). The 7 laws of magical thinking: How irrational beliefs keep us happy, healthy, and sane. Hudson Street Press.

- Ivanov, S. (2019). Tourism beyond humans - robots, pets and teddy bears. In S. Marinov, & G. Rafailova (Eds.), Tourism and intercultural communication and innovations (pp. 12–30). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Jensen, R. (1999). The dream society: How the coming shift from information to imagination will transform your business. McGraw Hill.

- Kalliala, M. (1999). Enkeliprinsessa ja itsari liukumäessä. Leikkikulttuuri ja yhteiskunnan muutos [The Angel Princess and Suicide in a Slide. Play culture and change in society]. Gaudeamus Yliopistokustannus University Press.

- Kline, S. (1993). Out of the garden: Toys and children’s culture in the age of TV marketing. Verso.

- Kozinets, R. V. (2010). Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. Sage Publications.

- Kozinets, R. V. (2015). Netnography: Redefined. Sage.

- Kücklich, J. (2005). FCJ-025 precarious playbour: Modders and the digital games industry. journal.fibreculture.org, Issue 5. https://five.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-025-precarious-playbour-modders-and-the-digital-games-industry/

- Kudrowitz, B. long, & Wallace, D. P. (2008). The play pyramid: A play classification and ideation tool for toy design. http://web.mit.edu/2.00b/www/2009/lecture2/PlayPyramid.pdf

- Lavidge, R. J., & Steiner, G. A. (1961). A model for predictive measurements of advertising effectiveness. Journal of Marketing, 25(6), 59–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296102500611

- Laws, E. (1995). Tourist destination management: Issues, analysis and policies. Routledge.

- Lindström, K. N. (2018). Destination development in the wake of popular culture tourism: Proposing a comprehensive analytic framework. In C. Lundberg, & V. Ziakas (Eds.), The routledge handbook of popular culture and tourism (pp. 477–487). Routledge.

- Long, J. A. (2007). Transmedia storytelling. Business, aesthetics and production at the Jim Henson company Master's thesis.

- Lugosi, P., Janta, H., & Watson, P. (2012). Investigative management and consumer research on the internet. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 24(6), 838–854. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111211247191

- Lund, N. F., Cohen, S. A., & Scarles, C. (2018). The power of social media storytelling in destination branding. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.05.003

- Lundberg, C., & Ziakas, V. (2018). Conclusion: Building a research agenda for popular culture tourism. In C. Lundberg, & V. Ziakas (Eds.), The routledge handbook of popular culture and tourism (pp. 488–495). Routledge.

- Lundberg, C., Ziakas, V., & Morgan, N. (2018). Conceptualising on-screen tourism destination development. Tourist Studies, 18(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797617708511

- Macbeth, J., Carson, D., & Northcote, J. (2004). Social capital, tourism and regional development: SPCC as a basis for innovation and sustainability. Current Issues in Tourism, 7(6), 502–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/1368350050408668200

- Mandelbaum, S. J. (1991). Telling stories. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 10(3), 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9101000308

- Miller-Winkler, S. (2009). Doll design done right. 10 tips to improve your chance for success. Playthings Magazine, February 2009, 19.

- Mossberg, L. (2008). Extraordinary experiences through storytelling. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 8(3), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250802532443

- Myers, D., & Kitsuse, A. (2000). Constructing the future in planning: A survey of theories and tools. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 19(3), 221–231.

- Noy, C. (2012). Narratives and counter-narratives: Contesting a tourist site in Jerusalem. In J. Tivers, & T. Rakić (Eds.), Narratives of travel and tourism (pp. 135–150). Ashgate.

- Olsson, A. K., Therkelsen, A., & Mossberg, L. (2016). Making an effort for free – volunteers' roles in destination-based storytelling. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(7), 659–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.784242

- Paavilainen, J., Heljakka, K., Arjoranta, J., Kankainen, V., Lahdenperä, L., Koskinen, E., Kinnunen, J., Sihvonen, L., Nummenmaa, T., Mäyrä, F., & Koskimaa, R. (2018). Hybrid social play final report. Trim research reports, (26).

- Pechlaner, H., Kozak, M., & Volgger, M. (2014). Destination leadership: A new paradigm for tourist destinations? Tourism Review, 69(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-09-2013-0053

- Reijnders, Van Es. N. S., Bolderman, L., & Waysdorf, A. (2021). Locating imagination in popular culture: Place, tourism and belonging. Taylor & Francis.

- Robinson, S. (2014). Toys on the move: Vicarious travel, imagination and the case of the travelling toy mascots. In G. Lean, R. Staiff, & E. Waterton (Eds.), Travel and imagination (pp. 168–183). Ashgate.

- Romagosa, F. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 690–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763447

- Romão, J., Guerreiro, J., & Rodrigues, P. M. (2012). Regional tourism development. In E. Fayos-Solà (Ed.), Knowledge management in tourism: Policy and governance applications (pp. 55–76). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Ruhanen, L., Scott, N., Ritchie, B., & Tkaczynski, A. (2010). Governance: A review and synthesis of the literature. Tourism Review, 65(4), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371011093836

- Scott, A. (2012). Meaningful play: How play is changing the future of our health. In Industrial Design Society of America. IDSA Educational Symposium, 2012 White paper. www.idsa.org/sites/default/files/Scott.pdf

- Selander, S. (1999). Toys as text. In L.-E. Berg, A. Nelson, & K. Svensson (Eds.), Toys in educational and socio-cultural context. Toy research in the late twentieth century. Part 2. Selection of papers presented at the International Toy Research Conference (pp. 39–46). Halmstad University.

- Sheldon, P. J. (2020). Designing tourism experiences for inner transformation. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102935

- SoCality Barbie. (2015). Instagram account, https://www.instagram.com/socalitybarbie/?hl=fi

- Sullivan, C. (2013, February). Competition heats up in the doll category. Toys & Family Entertainment, 40–43.

- Sutton-Smith, B. (1997). The ambiguity of play. Harvard University Press.

- Torres-Delgado, A., & Saarinen, J. (2014). Using indicators to assess sustainable tourism development: A review. Tourism Geographies, 16(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.867530

- Tuikka, A.-M., Nguyen, C., & Kimppa, K. (2017). Ethical questions related to using netnography as research method. The ORBIT Journal, 1(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.29297/orbit.v1i2.50

- Van Dijk, T. (2011). Imagining future places: How designs co-constitute what is, and thus influence what will be. Planning Theory, 10(2), 124–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095210386656

- Van Hulst, M. (2012). Storytelling, a modelofand a modelforplanning. Planning Theory, 11(3), 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095212440425

- Vartanian, I. (2006). Full vinyl. The subversive art of designer toys. Goliga Books, HarperCollins Publishers.

- Visit Qatar. (2021). Facebook post. 4 Nov. 2021, https://www.facebook.com/VisitQatar/posts/6959847234057554

- Volgger, M., Erschbamer, G., & Pechlaner, H. (2021). Destination design: New perspectives for tourism destination development. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100561