ABSTRACT

Jämtland in Northern Sweden is one of the most tourism and event-intense regions in the country. The rise in volume of events in alpine and subarctic nature environments, and the subsequent increase in participants, requires closer scrutiny of the environmental impacts. The region is characterised by mountains, forests and a sensitive ecological environment, and shared by several land users. With this study, we aim to gain in-depth knowledge of how environmental impacts are understood and valued in the regional assessment process for nature-based events and organised outdoor recreation. We analyse permit documents from the County Administrative Board of Jämtland from 2011 to 2020. The results show that most events were approved, and none were rejected solely due to environmental concerns. Assessments were instead balanced against other considerations, such as local development and economic gains. We argue that these priorities make nature a commercial arena for events, visitors and recreationists. This paper sheds light on human use and the associated environmental effects that further increase the pressure on nature. We end with managerial implications and propose that the permit process can be improved and integrated into spatial planning.

Introduction

Despite requests for a greater focus on the environmental sustainability aspects of events (e.g. Getz, Citation2020; Ritchie, Citation1984), this field remains largely unstudied aside from a few contributions (see Mascarenhas et al., Citation2021). Environmental impacts are commonly determined through certifications and measures (Getz & Page, Citation2015; Kaplanidou & Gibson, Citation2010), mainly highlighting littering or carbon footprint (Case, Citation2014; Holmes & Mair, Citation2020). The triple-bottom line, i.e. giving equal importance to the social, economic and environmental outcomes, has functioned as a safeguard for management and governments (Whitford, Citation2009) and a toolkit to facilitate strategic planning in the direction of sustainability (Brown et al., Citation2015). However, economic measures frequently prevail as the single most important factor (Weed, Citation2014). Furthermore, Hanrahan and Maguire (Citation2016) showed that public authorities do not follow environmental guidelines for assessing events. On this basis, our aim is to analyse how the public authorities weigh environmental impacts against other perspectives when assessing permit applications in nature-based events and organised outdoor activities. We explore this in Jämtland County, Sweden, where nature-based tourism and events have increased in popularity, reflecting a desire for a healthy lifestyle that attracts residents and tourists (Pettersson & Jonsson, Citation2022). The increase has created pressure on, and competition for, space in certain areas, leading to a range of environmental impacts and conflicts of interest among land users (Godtman Kling et al., Citation2019; Wall-Reinius et al., Citation2019; Citation2016).

Organising nature-based events and outdoor activities in Sweden normally requires a permit from the regional County Administrative Board. The long history of cataloguing governmental documents offers an opportunity to explore the process of assessing environmental considerations, which provides insight into understanding how authorities and organisers view the impacts on nature. The documentation reveals how these impacts are identified, considered and described, shedding light on the extent to which land use and types of impacts are considered relevant. We therefore ask:

What do organised outdoor recreation and nature-based events in Jämtland look like?

Which environmental impacts are considered in the permit authorisation process?

Which priorities guide the assessment of the applications?

Environmental concerns in nature-based events and organised outdoor activities

Environmental impacts from nature-based events

Organised events and activities are characterised by a spatial–temporal dimension, with a target group and an organiser. A nature-based event can thus be “any public open-air event, taking place in predominantly unmodified natural, rural, non-urbanised environment” (Margaryan & Fossgard, Citation2021, p. 237). They can vary in size and scope, including (non-)competitive aspects and (non-)motorised activities. When nature is capitalised as an attraction (Margaryan & Fredman, Citation2021), nature-based events present particular challenges.

Event research often links sustainability to the triple-bottom line and to mega-events (Getz & Page, Citation2015). The triple-bottom line approach to sustainability has guided event and tourism research to consider sustainability not only in terms of addressing environmental issues, but also to consider economic and social concerns. In other words, when examining environmental issues, other related issues will inevitably arise. While the focuses on environmental sustainability in events has typically been on air and water pollution, litter and waste, vegetation trampling, congestion and crowding (Holmes & Mair, Citation2020), the environmental impacts could be diverse. Events entail countless links to various stakeholders with their specific motivations, interests and perspectives, making it more difficult to accurately describe the impacts (Yuan, Citation2013). Furthermore, the lack of a common vocabulary and non-economic metrics confuses the issue and makes it harder to achieve environmental and social sustainability (Brown et al., Citation2015; Smith-Christensen, Citation2009; Wallstam & Kronenberg, Citation2021).

Several common denominators, indicators and standardisations have been proposed to evaluate the environmental consequences of events (e.g. Andersson et al., Citation2012; Boggia et al., Citation2018; Brown et al., Citation2015; Brownlie et al., Citation2020; McCullough et al., Citation2018; Toscani et al., Citation2022). Beyond self-evaluation criteria, specific criteria to measure environmental impacts of events are lacking (Case, Citation2014). Self-evaluations are commonly done by self-reporting and assessment measures derived from different stakeholders’ perspectives (see e.g. Duan et al., Citation2021; Perić et al., Citation2019). However, Graefe et al. (Citation2019) found that participants in three types of sport events assessed their activity as being less harmful than others, as causing no significant harm, and instead improving the environment. The participants struggled to comply with “leave-no-trace” policies because they did not perceive nature as untouched or temporary. Practitioners in nature blame other types of activities to be more damaging (Brown, Citation2015) and focus on the performance and less on the environmental impacts (Backman & Svensson, Citation2022). Self-assessments can therefore be unreliable for determining environmental effects.

Research on the direct physical environmental impact from events in the outdoors is, however, scarce. Ng et al. (Citation2017) measured soil erosion from a trail-running marathon in Hong Kong. The event caused persisting, aggregated and degrading features on the soil that were greater than equivalent outdoor activities. To protect the soil from further damage, the authors suggested that the local policy-makers limit events to a maximum of 300 participants per year. Marion et al. (Citation2016) came to similar conclusions when they investigated an orienteering event, but due to the limited data, their findings could be not verified. However, numerous possible environmental impacts from spectators and the participants, such as creating informal trails, trampling on the ground, loss of soil cover, vegetation loss or disturbance of wildlife, are conspicuously absent in event research (Marion et al., Citation2016; Newsome, Citation2014). With few studies on the environmental impacts of events, we must rely on research on recreational use and its impact on the natural environment. Despite some differences between events and outdoor recreation, impact studies from mountain areas, subarctic and arctic regions can be useful to determine what may be relevant for events in the Jämtland region and similar locations.

Ecological impacts from recreational activities

Recreational impacts have focused on mechanical wear mainly from trampling which effects vegetation, soil and erosion, on motorised activities and air pollution, and on animal disturbance. Mechanical wear from hiking, running, cycling, horse riding or motorised vehicles can cause erosion, compacted soil and a reduced soil humus layer. There are differences in how sensitive an area can be. Slopes are more sensitive than flatter terrain (Tolvanen et al., Citation2005), wet environments are affected more than drier environments, grass vegetation is more durable than lichen and shrub vegetation (Allard et al., Citation2004; Emanuelsson, Citation1984; Fosse, Citation2012), and trails provide increased speed for water, thus increasing the risk of erosion (Harden, Citation2001).

Emanuelsson (Citation1980) has shown that, in the Swedish mountains, unused paths through herbaceous vegetation are hard to locate after 10 years. Trails in crowberry brushwood in high altitudes in Central Europe and in Norway are still visible 50 years after the trampling (Cernusca, Citation1991; Fosse, Citation2012). On older trails with a slow increase in use, it is possible for grass-dominated vegetation to grow, whereas on a new trail with intense use no new species can establish (Tolvanen et al., Citation2005). Ullring (Citation1989) found that in the Scandinavian mountains a rather small number of passages (less than 425) is enough to maintain a trail. However, trampling early or late during the season has less of an effect than during the middle of the vegetation period (Emanuelsson, Citation1984). In addition, trampling and cycling contribute to soil compacting (Martin & Butler, Citation2021). Compacting decreases water-absorption, and microorganism flora, which means fewer nutrients get to the plants and more water flows on the surface, leading to increased erosion. When it comes to traces from motor vehicles, traces have been left throughout the Swedish mountain range (Allard et al., Citation2004), particularly on bogs and slopes (Christensen & Sundquist, Citation2007). In addition, motor vehicles emit greenhouse gases as well as sodium, calcium, magnesium and fluoride, which end up in nature (Ingersoll, Citation1999; Musselman & Korfmacher, Citation2007), and unburned fuel and oils are also deposited, which affects water quality (Gioria et al., Citation2020; Viskari et al., Citation1997).

Recreational activities can cause disturbances on wildlife, and direct impact occurs when animals flee or change their behaviour as recreationists approach (Steven et al., Citation2011). Indirect impacts can lead to changed habitats, which may change the conditions for several species (Lucas, Citation2020). In Scandinavia, studies on animals other than reindeer are few. Scandinavian studies have focused on both reindeer disturbance and interference with reindeer herding. In fact, domesticated reindeer exhibit avoidance behaviours up to 12 kilometres from infrastructure and human activities (Skarin & Åhman, Citation2014). Another study on avoidance comes from Hardangervidda in Norway, and it shows that the reindeer avoided hiking trails with more than 30–50 hikers per day (Gundersen et al., Citation2020). Disturbance of reindeer can mean that they avoid areas where there is good grazing, but it can also mean an increase in the reindeer’s time in movement, thus energy consumption increases. Especially during the gestation period and calving time, female reindeer are sensitive (Skarin & Åhman, Citation2014; Vistnes & Nellemann, Citation2001).

Reindeer herding is an essential cornerstone of the Sami culture, heritage and identity, as well as a commercial activity. The disturbance of reindeer therefore has many consequences. Conflicts can arise when reindeer herding competes with recreational activities for the same space. Reindeer herders have expressed concerns about the situation in the Jämtland mountains (Godtman Kling et al., Citation2019). The visitor-reindeer interaction is complex. Studies show that reindeer constitute a significant part of the visitor experiences (Pettersson, Citation2004; Wall-Reinius, Citation2012; Citation2006). An encounter strengthens the visitor experience and adds to the attraction of the mountains (Wall Reinius, Citation2006). Moreover, reindeer grazing affects the whole mountain landscape and its biodiversity, for example by contributing to open landscapes, preventing overgrowth and lowering the tree line (Axelsson Linkowski, Citation2012; Olofsson et al., Citation2005; Stark et al., Citation2002). Without grazing, the landscape would change significantly. The cumulative effects of expanding infrastructure and human activities (i.e. combined influences of multiple practices and circumstances) have recently been analysed to understand more about how these disturb reindeer populations and reindeer herding (e.g. Eftestøl et al., Citation2021). Importantly, in addition to the expansion of human activities in grazing lands, climate change and the presence of large predators add to the cumulative impacts (Stoessel et al., Citation2022).

Methodology

The study area of Jämtland

The county of Jämtland in northern Sweden is a sparsely populated region (appr. 130,000 inhabitants), with the largest city being Östersund. The landscape to the east is covered by large forested areas with smaller villages. To the west, the landscape is dominated by mountains with several tourist resorts offering year-round activities, including skiing, hiking and biking, becoming more common in tourism marketing and development strategies (Pettersson & Jonsson, Citation2022). Besides job opportunities and incomes, events enhance social values such as pride, identity, public health and integration (Wallstam, Citation2022). This area also accommodates grazing lands for reindeer. Reindeer herding is organised within several administrative units, called Sameby (Sami village), which are also geographical areas in which reindeer herding takes place. The county administrative board also consults the Sameby regarding mountain activities on reindeer grazing land since reindeer herding disturbance is regulated under the Reindeer Herding Act (SFS, Citation1971, p. 437).

Description of data and analysis

The database and sample

The 21 Swedish county administrative boards (Länstyrelser) are national governing bodies that oversee and implement legislation and policies. Due to the Swedish right of public access, individuals and collectives, including commercialised tourism and outdoor recreation activities, have far-reaching rights which entail some impact on nature. An organiser of an event must apply for a permit if the activity risks causing environmental impacts or disturbing reindeer herding. The permits ideally contain a description, evaluation from government bodies, email conversations and memos, and a concluding justification and decision. If approved, special limitations and requirements can be added, or if denied, an additional justification is given. The applications sent in by organisers should contain specifics including time and date, location, activity and who is responsible, number of participants, special considerations and other details. Each application contains documentation from all concerned parties e.g. organisers, case officers, rights holders. It should be noted that there are no pre-structured protocols, apart from short non-mandatory descriptions on the webpage. It is therefore down to the organiser to identify and judge the specific impacts that might occur. Moreover, annual events are sometimes asked to include a final report to evaluate the environmental impacts, which serves as a foundation for future applications. After payment of an administrative fee, the request is sent for further evaluation by the governmental bodies concerned, e.g. the Swedish Transport Administration, Sameby or municipalities.

The permits in our study cover six different cases; significant change of the natural environment, protected areas, protected species, dialogue with landowners (private, municipal or governmental), rights holders (e.g. hunters or reindeer herders) and on-road events. Due to the principle of public access to official documents in Sweden, we had access to permit applications dating between 2011 and 2020 that fully or partially contained keywords equivalent to “event”, “competition”, “outdoor recreation”, “arrangement”, “bike”, “sport”, “race”, “land-use agreement”, “exercise”, “trail”, “tent”, “training” or “animal”. In dialogue with the archivist, the sets of keywords were broadened to allow for misspelled words and to capture the majority of permits. We received 500 permit applications, removed 107 irrelevant applications (duplicates, too fragmented or could not be considered events) and finally analysed 393 complete permit applications.

Two factors of uncertainty are to be taken into account. First, the County Administration Board had fallen behind on their handling of the permits according to the archivist who explained that some required documentation had not been sent in by case officers. Second, we had no direct access to the database and we could only get access to the permit applications based on the selected keywords. After dialogue with the County Administration Board and the Swedish Environmental Agency, we believe that the list of permits is likely to cover most of the applications and only a small number are missing.

Analysis

Although the method of content analysis is widely used, it can be applied in several different ways (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). The sample in this study allows for a qualitative content analysis to gain insights into the environmental impacts and the decision-making processes. We structured the permits using NVivo, applying a cluster sample (Krippendorff, Citation2004), in which the larger sample and the population are unknown. Our further analysis focused on discussions that were connected to environmental impacts, which in turn were summarised into patterns and then explored to unveil the meaning behind these patterns.

Workshop and clarifying dialogues

In November 2022, we carried out a half-day workshop to clarify and discuss topics related to environmental impacts and the justifications that emerged in the documentation. We gathered 16 participants, including four case officer specialists that were directly involved in the assessment process, one department head, and three other case officers with expertise in outdoor recreation and protected areas, two representatives from one of the municipalities, four researchers involved in the project (of which three are authors of this paper), one facilitator, and one representative from the Swedish Sports Confederation since she has followed the project over time. The participants were divided into three smaller groups (one author assigned to each group), and each group took notes to put up on a process timeline and discussed challenges and matters that were unclear, such as instructions to applicants, internal methods and processes, justifications and evaluations. For further clarifications, we held dialogues with an archivist, two case offices and a responsible administrator at the County Administrative Board. All steps in the process were documented and discussed between the researchers.

Results

This section presents and summarises the results in two parts. First, we present the types of event activities and corresponding overall environmental impacts that emerged from the documentation, highlighting the basic numbers, distribution and types of impacts that emerged. Second, we describe in-depth some of the assessments, how the environmental impacts were compared against other interests, the role of self-evaluation and finally, on what basis events were limited and rejected.

Applications and environmental impacts

All the selected permits were for events set in the outdoor environment, in locations not requiring venues nor constructed sites, such as ski slopes, motorsport arenas or urban and built-up environments. In terms of numbers, of the 393 permits analysed, 150 different organisers were involved including sport associations, commercial firms, private persons and schools. The most common amount of expected participants was between 50 and 100 participants. A total of 16 events expected over 500 participants. However, most applications do not specify any size. The types of events are summarised in . Motorsports, such as tractor pulling or motor racing on forest roads, are the most common events. Other terrain-related motor activities, e.g. Enduro, are listed separately. Organised outdoor (non-competitive) activities encompasses hiking, running and others, almost always involving camping. Multisport involves several types of sports in one event, including biking and running on the road, or sometimes triathlons and swim-runs.

Table 1. Number of applications between 2011 and 2020 in Jämtland County, categorised by type.

Our sample unveils some observable patterns over time. Over a yearly distribution the sample is uneven. There is a relatively stable development in terms of number of events that are applied for. In terms of monthly distribution, the permits in our sample show that most events are requested to be held between the end of June and September. The sample also shows that relatively few permits were for wintertime events, despite the location which has long winters. Most organised outdoor activities were held in September, which conflicts with other interests, such as hunting and moving reindeer between grazing areas. This is discussed further below.

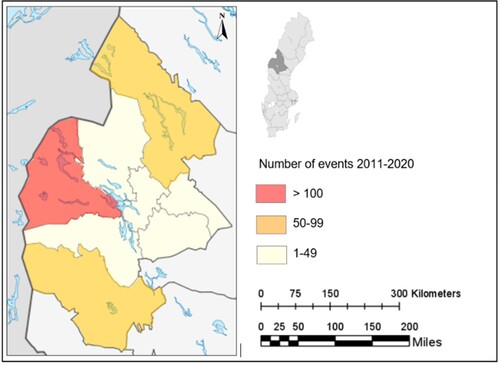

The events were distributed across the region. shows the number of events in each municipality. There were 68 different locations distributed across eight municipalities in the county, 10 events passed through more than one municipality, and are thus not included in the map. Most events are to be found in the tourism intense mountainous areas in the western part of the region (municipality of Åre). The northernmost municipality Strömsund is somewhat of an anomaly as it shows the second highest number of events, especially in the villages of Gäddede and Saxvattnet. Despite being rural and having less tourism activities compared to some of the other municipalities, Strömsund arranges more forest-oriented events including several dog-sledding competitions. Small sport associations make a significant difference, with groups of few enthusiasts offering a large number of events. In third place, the southernmost municipality of Härjedalen shows a similar event portfolio to the event-intense municipality of Åre in the western part of the region.

In the documents analysed, the environmental impacts were described by the case officers, organisers or other stakeholders, such as the Sameby or the municipality. The impacts that appeared in the permit applications are showed in . The environmental impacts are intentionally categorised as they appear in the permit processes. Some applications addressed several different impacts. The list illustrates that the terminology is broad, and some of the categories are closely connected to each other. There was no predefined checklist that applicants needed to fulfil. In certain cases, however, some national and regional sport associations provided checklists for their members. The National Motorsports Association, for instance, has protocols for organisers that to some degree address environmental impacts. The table also shows how many applications (number of events) contained each impact. However, of the 393 permits analysed, in 216 cases the organiser did not evaluate or mention environmental impacts in their initial application. Further, in 49 permit applications, no environmental evaluation was performed by the County Administration Board or by any other public authorities.

Table 2. Impacts described in the permit applications and number of events that contained each impact.

The environmental impacts mentioned are largely connected to the mountain environment and to reindeer-related issues. Most reindeer-related cases, with some exceptions, were processed and commented on by the affected Sameby, and over time it is clear that they showed greater concerns. The second most common environmental concern in the permit applications is trash and litter, mostly emphasising that the organiser should remove waste after the event. Third, the impact on nature reserves deals with issues related to the event being held in a protected area and is a reminder for the organiser to protect nature. These three environmental concerns are addressed frequently with comments such as “do not disturb the reindeer” or “collect rubbish afterwards”. Despite motorsports dominating the applications (), greenhouse-related questions were only mentioned twice (). At the same time, “wear and tear on the ground”, and “chemical and fuel” were more frequent but only described in general to alert the applicants. Wear and tear on the ground from non-motorised activities was frequently detected, but, again, was described on a more superficial level. The terminology in the permit process refers to “impact on hiking trails”, “terrain damage” or “impact on terrain”, demonstrating that terminology is confusing and that there is a lack of common or precise vocabulary. Other issues such as water quality, cultural heritage and sanitation were occasionally mentioned. Regarding wildlife disturbances, the County Administration Board expected organisers to hold the event protectively and occasionally reminded the organiser of the specific bird types in the area. Larger disturbances to ecosystems or vegetation were rarely mentioned, thus not prioritised during the evaluations. During the workshop, the participants did not mention concrete examples of environmental impacts at all. Instead, they emphasised cumulative effects and the overall increase in visitor numbers, which is hardly visible in the documentation.

Despite these impacts, almost all the applications in this sample were accepted. In fact, only 19 permits were rejected, none of which were rejected solely due to environmental concerns. 43 permits were withdrawn, due to a lack of response, too close to the deadline or voluntary cancellation when extensive evaluations were required, especially over reindeer-grazing territory or inability to comply with the protection requirements.

Environmental assessment

Weighing environmental impacts against other impacts

The qualitative document analysis demonstrates that few environmental protection measures and precautions were taken by the organisers, who mainly focused on non-environmental concerns, e.g. safety of participants, volunteers and others. While the organisers provided information about the precautions they would take for non-environmental issues, such as road safety, environmental concerns were dealt with in just a few short sentences. Descriptions of environmental protection actions were generally not provided. Instead, the organisers were asked to control participants’ behaviour, for instance, walking outside the trails or littering would lead to disqualification. The only difference was for applications regarding motor events on roads, which the assessors often questioned.

Environmental issues were handled by the County Administration Board in a routine-like manner, and recommendations were mostly added at the end of the verdict, for instance, to remove rubbish and litter or remove markings and signs. Each event was approved in broader terms including the number of participants and details regarding disturbances or environmental effects. Another way to understand environmental impacts could have been to refer to, or ask for, an environmental certification. However, certifications arise in only two cases. No other precautions or measures to protect the environment were taken.

For the most part, the permits were approved without extensive restrictions. Instead, the events appeared to attract economic activities for local and regional development or encouraged the general public to be in nature for public health, which was confirmed during the workshop. Furthermore, a few organisers were asked to move the date of their event to a more suitable period, e.g. to avoid disturbing the reindeer. The evaluations were stricter depending on the type of events. Smaller organised outdoor activities were subject to stricter restrictions due to the timing and circumstances of the event. For instance, a major sport event organiser had major difficulties in addressing the environmental issues raised by local stakeholders but was approved after continued dialogue with the case officers. In contrast, a few weeks later, a group of hikers was simply asked to change their location. In other cases, the inconsistently motivated precautions were connected to priorities beyond the environment, which is explicitly illustrated in the justification statement for a dog-sledding event:

… [the competition] supports the increasing interest in non-motorised outdoor activities and ecotourism. The competition receives mass media attention, which benefits the region [… but] may cause disturbance to reindeer in the area.

Attention to the environment comes second, while the expected regional economic benefits is given more attention. The workshop participants, however, were thoughtful regarding this fact, since the agency’s mission is to protect nature according to the Environmental Code and to safeguard reindeer herding according to the Reindeer Herding Act. In the excerpt above the potential impacts were weighed against the media attention. Moreover, it assumes by default that ecotourism has no environmental impact and subsequently addresses events as already sustainable.

On a similar note, in the assessment of a lager sport event, different interests are weighed against each other and the economic interest prevails. One case officer wrote:

… the initiative promotes an active outdoor life and activities in rural areas. The construction of wooden footpaths may be a positive contribution to the area. The improved quality of the trails also benefits tourists [… and there are] no significant disturbances to reindeer herding [… Therefore] exemption [can be granted] despite disruptions that may occur …

In another example, a motor race on a frozen lake that passed through a highly protected zone was expected to emit greenhouse gases. It was stated that:

According to the conservation plan, and the lake’s sensitive ecological status, there is a risk of acidification effects […] Pollutant particles from these activities are just one example of effects that may threaten the natural value.

The event was approved without any requirements for alterations. During the workshop, it came to our attention that some governmental officials had experienced that decisions made by case officers were bypassed at a higher level. It became clear that the benefits of holding events, with the associated potential economic impacts, meant more than the case officers’ knowledge and expertise, for example in environmental issues.

Self-evaluation

When an event is annual, the organisers’ self-evaluation reports lay the foundation for an upcoming permit the following year. The organisers themselves were to define the severity of the impacts. Only on rare occasions did the organiser have to describe the impacts. The workshop discussion showed that the case officers trusted the organisers to protect and maintain nature. However, some organisers were required to report their impacts. For instance, a larger multisport event was required to provide an analysis as follows: “If you see that the competition generates wear and tear, it would be appreciated for future competitions [… that] you describe the issue and the measures intended to solve the issue”. Descriptions such as these were scarce, however. In a few instances, the organisers were required to perform self-evaluations. Their testimonies functioned as a cornerstone of the assessment for future planning. However, these evaluations never contained any negative comments regarding effects on the environment, and issues and challenges were subjectively defined. For instance, in a mountain bike event, wear and tear on the ground near prehistoric cultural heritage was discussed after the residents complained. However, the organiser, who was also in contact with residents, countered by blaming the wear and tear on snowmobiles. The workshop members attested that the self-evaluation and reporting are built on trust, acknowledging that different stakeholders, including themselves, calculate impacts differently. This split view of impacts is explained in more detail in the next section.

Limits and rejections

No rejections were enforced grounded on environmental issues, which was acknowledged during the workshop and conversations. Minor revisions, such as changes according to size, routes and camp-site locations or dates, were asked for. On three occasions, however, partial limitations were enforced to already approved events. In one case regarding a request for an additional route, a case officer thought the added activity would surpass a limit: “I am putting a stop to this [part of the event] pursuant to the environmental [legislative] code and possibly other codes … ”. The example also indicates uncertainties about what limitations to enforce because various departments and experts process different laws and registrations. These challenges were confirmed during the workshop.

To protect the environment, organisers were required to take on certain responsibilities in advance. Some had to build wooden footpaths, place protective mats over wet paths, or, in more rare cases, the organisers had to obstruct access to wildlife in the area. Workshop participants highlighted that they had limited funding to check whether these actions were implemented. This indicates that the fee for the permits does not cover the work, the checks nor the evaluation. The restrictions and constructions can be said to be built on trust.

Limited or rejected permits were mainly connected to organised outdoor activities that applied for permits close to the small-game and moose-hunting season in early September. For instance, a rejected application for 100 participants to camp in a nature reserve contrasts with the acceptance of a running event with up to 2000 participants some weeks earlier. Another example where limits and acceptance of impacts can be questioned is from an annual mountain-bike event. The organisers made a report of the impacts. They used photos from the day before the event and new photos some months after the event and reported no significant environmental impacts. However, in a meeting between the organiser, the case officers and the nature observers, the nature observers showed their own photos and stated:

[County Administrative Board:] [Nature observer 1] showed photos of grooves created by wheel tracks that were intensely wet after the competition, among other issues. [Nature observer 2], among other things, showed photos where the trail direction the event used was wetter and more worn than another trails direction …

This excerpt shows that the different actors gave different accounts, as they interpreted the photos in different ways. The workshop participants attested that organisers can see impacts very differently, and such differences of opinions is also illustrated by the stance of the Sami. Most applications were related to reindeer disturbance and the moose-hunt starting in September, which involve Sameby in specific geographic areas. These instances were often linked to organised outdoor activities, for example, when the reindeer move between different grazing locations. Some Sameby developed a more reserved attitude over time that was noticeable within the documentation and confirmed by the case officers during the workshop. In some applications, the County Administrative Board’s decisions went against Sameby’s verdict, as they accepted the application despite the potential disturbances stated by the Sameby. For example, an annual dog-sledding competition of 40 participants was described as having negative impacts. Still, despite the fact that the Sameby opposed the activity, the event was approved without further limitations:

The situation is currently very problematic due to the reindeer herding, so the Sameby felt a need to report the event as it may cause disastrous damage […] Several sections of the […] races are deemed to be very unsuitable.

Discussion

This paper provides insights into how environmental concerns are addressed in assessment processes for nature-based events and organised outdoor activities. We sought, more concretely, to understand how the public authorities give priority to various impacts and benefits when assessing permit applications. The results of the examination of 393 permit applications dated between 2011 and 2020 provide a comprehensive overview that generates insights and knowledge into how environmental concerns are addressed and what the trade-offs in the permit decision process look like. We identified a wide range of events and vague descriptions of the subsequent environmental impacts. These impacts add to the cumulative effects not addressed in the permits, but over time affecting the local environment, and not least the reindeer herding. Cumulative effects were raised in the workshop but not in the permits, indicating that the processes do not include any control mechanisms that regulate issues and impacts over a longer period of time. The applications were approved based on matters other than environmental criteria, most notably the economic benefits, regional development and public health. As such, nature is a resource for consumption, making it an arena for recreational products and services, with permits addressing other priorities than the initial mission to protect nature and safeguard ecosystems.

Studies on outdoor recreation and environmental impacts in the Scandinavian mountains have focused on wear and tear on the ground (e.g. Christensen & Sundquist, Citation2007; Emanuelsson, Citation1984; Fosse, Citation2012) and on stress on reindeer (Skarin & Åhman, Citation2014; Vistnes & Nellemann, Citation2001). Fewer studies focus on disturbances to other animals and changes in animal behaviour from outdoor recreation. In our material, few considerations were given to animals other than reindeer. The direct impacts on the ground were to some degree discussed in the permits. Details about impacts on slopes, different periods, the relation to other species, and effects of erosion and soil compacting were mostly lacking. Instead, these impacts were discussed in general terms. Many of the events applied to pass through mountainous environments with slow regrowth which surprisingly was hardly addressed by the County Administration Board. Although the environmental effects of different vehicles on the terrain were acknowledged, several of them could persist in nature for the long term and affect water quality were discussed less in relation to the number of events. Lastly, the number of participants was given little attention in sport events in particular, even though earlier studies show that the effects from trampling occur after relatively few numbers of passage (Ullring, Citation1989), and leave traces on the trails which persist for many years thereafter (Cernusca, Citation1991; Fosse, Citation2012).

Our results show that the events use the same area as reindeer herding, nature-based tourism and outdoor recreation, especially during the most sensitive vegetation period (Emanuelsson, Citation1984) and the important grazing period for reindeer (e.g. Skarin & Åhman, Citation2014). Reindeer herding is under pressure not only from events and recreational activities and the associated infrastructure, but also from other competing land users, predators and climate change (Eftestøl et al., Citation2021; Godtman Kling et al., Citation2019; Stoessel et al., Citation2022). Regardless of the fact that stakeholders, such as a Sameby, opposed events, our study shows that the applications were approved. Although Sami also runs tourism businesses and, or, events (Pettersson, Citation2004), the cumulative effects from several activities cause feelings of saturation, which can further fuel future tensions.

The subjectivity in the application process leaves it to the organisers to decide the severity, relevance or preservation of the impacts, and they sometimes tend to transfer these responsibilities to the participants. Organisers are less specific, often claiming that their activities are less harmful, and ultimately authorities have to trust them to act sustainably. However, identifying or tracking potential impacts through self-evaluation might be futile (Graefe et al., Citation2019). As the results showed, the severity of the impacts might have a diametrical interpretation. The organisers provided few environmental evaluations or analyses, illustrating that environmental impacts had little priority. The emphasis was instead on non-environmental metrics (e.g. security), indicating that analysis was nevertheless feasible. Organisers were mostly reminded to implement small actions, such as “picking up trash” or “paying attention to trampling”. There were few stipulations for actions to limit the impacts, and instead, the evaluations were built on trust, even though it was known that the organisers might have another view of what constitutes impact and its severity.

With only a few exceptions, most permits were approved regardless of the environmental impacts. There were no distributed guidelines or standardised evaluation from the County Administrator Board. This lack of guidelines and standardised evaluations has been found elsewhere as well (e.g. Case, Citation2014; Hanrahan & Maguire, Citation2016). The lack of clarity and direction created a broad list of different terminology to describe the impacts. The lack of guidance on environmental impact is reflected in the applications. Most organisers gave few indications or evaluations of the impacts. Moreover, the high approval rate was guided by a desire to provide access to nature, justified by the argument that the event contributes to public health or strengthens economic contributions and regional development. This is consistent with previous claims (Dredge & Whitford, Citation2011; Smith-Christensen, Citation2009) that economic gains from commercial events prevail. This economic focus is noticeable in how the evaluations differed between commercial (sport) events and organised outdoor activities. The former was perceived to provide economic contributions, while the latter were given more precautions, demands or restrictions. This pattern also corresponds with the knowledge gap regarding the environmental effects specifically stemming from (sport) events, which are evaluated according to the commercial aspects, while organised outdoor activities tend to be evaluated according to their environmental impacts.

Conclusions

Through analysis of permit documents from the County Administrative Board of Jämtland, we have explored environmental concerns in the assessment process for nature-based events and organised outdoor recreation, including an overview of event types and their use of nature in a tourism and event-intense region. Despite the risk of disturbances to reindeer, wear and tear on the ground, emissions and other environmental impacts, almost all the applications in this sample were approved. Hence, few permits were rejected, and none were rejected due to environmental matters. Few considerations were given to the natural environment even though various environmental impacts, challenges and objections are to be found in the documentation. When mentioned, environmental impacts were written in general terms and in a vague manner. Consequently, environmental concerns play a marginal role in the permit assessment. This indicates that there are other motives for accepting the events, such as social and economic factors, especially in sport and tourism. Thus, nature has become an important resource for products and services and, as such, nature is an arena for events and leisure activities aimed at local development, health and wellbeing and economic gains (c.f. Wallstam, Citation2022).

Assessing the environmental effects of nature-based events and organised outdoor activities presents distinct challenges. Every event is a unique occasion (Getz, Citation2020; Sharpley & Stone, Citation2020) and this also applies to the impacts. Previous research has proposed different environmental indicators for events (Hanrahan & Maguire, Citation2016; Holmes & Mair, Citation2020). However, this paper has identified impacts that are unique to a mountain location. Nevertheless, isolated standardised and all-encompassing environmental impact evaluations cannot provide the depth for the diversity of impacts that arise from all types of events, environments, spaces or climates. This discussion of events, moreover, is part of a larger commercialisation of nature as an experience (Margaryan & Fossgard, Citation2021) and planning for sustainability. Events, and their impacts, need to be connected as parts of a larger ecosystem of activities and recognised for the potential cumulative effects and risks of nature degradation. Policies and planning for events should not be seen in isolation (Hanrahan & Maguire, Citation2016; Weed, Citation2014), but instead treated as connected elements in a living landscape of various outdoor activities and participants (Wall-Reinius et al., Citation2019; Citation2016). Planning for events require a more holistic approach that considers their impacts on the interconnected system of everyday life and tourism, as well as their role in overall development (Holmes & Mair, Citation2020). Therefore, events should be treated as part of larger development, with a clear delegation of responsibility for future impacts.

Future research must identify the challenges to the specific context. Management and planners must identify a common set of vocabulary that connects to the specific impacts from that area (Graefe et al., Citation2019), and providing a more standardised template for completion would most likely make the permit processes more reliable and efficient. To guide and arrange sustainable events, it appears necessary to define an appropriate size and time that prevents future impact that goes beyond the general described impacts. Future spatial planning must consider the cumulative effects of tourism and recreation and the event. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) can probably play an essential role in doing this. Permit processes could even become proactive by listing and communicating areas and times that are more suitable for outdoor activities and events.

Finally, acknowledging our limitations, we have limited the study to six types of permit processes and certain keywords. Furthermore, we cannot with certainty identify which permits are missing from our sample. Other keywords, process or scope may contain other types of impacts or events. We treated all permits the same, whereas future studies could examine a specific type of permit or refine the methodology. Additionally, social media groups or groups of friends may gather and arrange informal events or outdoor recreation happenings, which in fact could also require a permit even though this is at the limit of what can be considered to be events. They share similar features but it is far more difficult to control their impacts and would add to the understanding of land use, environmental concerns, cumulative effects and responsibility.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to MISTRA Sport & Outdoors and Mid Sweden University. The authors would also like to thank Markus Larsson at the County Administrative Board of Jämtland, who assisted in compiling the data, and Paul van den Brink for his knowledge on mountain ecosystems. Axel Eriksson: Conceptualisation, led data curation and collection, analysis, writing original draft and reviewing. Robert Pettersson: Conceptualisation, data collection, writing, review & editing. Funding acquisition. Sandra Wall-Reinius: Conceptualisation, data collection, writing, review & editing. Funding acquisition.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allard, A., Löfgren, P., & Sundquist, S. (2004). Skador på mark och vegetation i de svenska fjällen till följd av barmarkskörning. Institutionen för skoglig resurshushållning, SLU.

- Andersson, T. D., Armbrecht, J., & Lundberg, E. (2012). Estimating use and non-use values of a music festival. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 12(3), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2012.725276

- Axelsson Linkowski, W. (2012). Renbete och biologisk mångfald med utgångspunkt i publicerad forskning Renbete och biologisk mångfald med utgångspunkt i publicerad forskning. In H. Tunón, & B. S. Sjaggo (Eds.), Ájddo – reflektioner kring biologisk mångfald i renarnas spår (pp. 11–51). CBM:s skriftserie.

- Backman, E., & Svensson, D. (2022). Where does environmental sustainability fit in the changing landscapes of outdoor sports? An analysis of logics of practice in artificial sport landscapes. Sport, Education and Society, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2022.2073586

- Boggia, A., Massei, G., Paolotti, L., Rocchi, L., & Schiavi, F. (2018). A model for measuring the environmental sustainability of events. Journal of Environmental Management, 206, 836–845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.11.057

- Brown, K. M. (2015). Leave only footprints? How traces of movement shape the appropriation of space. Cultural Geographies, 22(4), 659–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474014558987

- Brown, S., Getz, D., Pettersson, R., & Wallstam, M. (2015). Event evaluation: Definitions, concepts and a state of the art review. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 6(2), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-03-2015-0014.

- Brownlie, S., Bull, J. W., & Stubbs, D. (2020). Mitigating biodiversity impacts of sports events. IUCN.

- Case, R. (2014). Event impacts and environmental sustainability. In J. Page, & S. Connell (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of events (pp. 375–397). Routledge.

- Cernusca, A.. (1991). Ecosystem research on grasslands in the Austrian Alps and in the central Caucasus. In G. Esser & D. Overdieck (Eds.), Modern Ecology: Basic and Applied Aspects (Vol. 1, pp. 233–271). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Christensen, P., & Sundquist, S. (2007). Uppföljning av utredningen: Skador på mark och vegetation i de svenska fjällen till följd av barmarkskörning. Nationell inventering av landskapet i Sverige.

- Dredge, D., & Whitford, M. (2011). Event tourism governance and the public sphere. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4-5), 479–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.573074

- Duan, Y., Mastromartino, B., Zhang, J. J., & Liu, B. (2021). How do perceptions of non-mega sport events impact quality of life and support for the event among local residents? Sport in Society, 23(11), 1841–1860. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1804113

- Eftestøl, S., Tsegaye, D., Flydal, K., Reimers, E., & Colman, J. E. (2021). Cumulative effects of infrastructure and human disturbance: a case study with reindeer. Landscape Ecology, 36(9), 2673–2689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-021-01263-1

- Emanuelsson, U. (1980). Den ekologiska betydelsen av mekanisk påverkan på vegetation i fiällterräng. Fauna och Flora, 75(1), 37–42.

- Emanuelsson, U. (1984). Ecological effects of grazing and trampling on mountain vegetation in northern Sweden. Lunds University.

- Fosse, S. H. (2012). Slitasjeskader på vegetasjonen langs Aarmotslepa; Vegetation damages along Aarmotslepa. NMBU.

- Getz, D. (2020). Event studies. In J. Page, & Connell (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of events (pp. 31–56). Routledge.

- Getz, D., & Page, S. J. (2015). Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tourism Management, 52, 593–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.03.007

- Gioria, R. A., Parque, P. M., Carriero, M., Forni, F., Montigny, F., & Padovan, V. (2020). Snowmobile vehicles in service monitoring based on PEMS: Lessons learned from the European pilot program Joint Research Centre. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Godtman Kling, K., Dahlberg, A., & Wall-Reinius, S. (2019). Negotiating improved multi-functional landscape use: Trails as facilitators for collaboration among stakeholders. Sustainability, 11(13), 3511–3532. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133511

- Graefe, A., Mueller, J. T., Taff, B. D., & Wimpey, J. (2019). A comprehensive method for evaluating the impacts of race events on protected lands. Society & Natural Resources, 32(10), 1155–1170. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2019.1583396

- Gundersen, V., Myrvold, K. M., Rauset, G. R., Selvaag, S. K., & Strand, O. (2020). Spatiotemporal tourism pattern in a large reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) range as an important factor in disturbance research and management. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1804394

- Hanrahan, J., & Maguire, K. (2016). Local authority provision of environmental planning guidelines for event management in Ireland. European Journal of Tourism Research, 12, 54–81. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v12i.213

- Harden, C. P. (2001). Soil erosion and sustainable mountain development. Mountain Research and Development, 21(1), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1659/0276-4741(2001)021[0077:SEASMD]2.0.CO;2

- Holmes, K., & Mair, J. (2020). Event impacts and environmental sustainability. In J. Page, & S. Connell (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of events (pp. 457–471). Routledge.

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Ingersoll, G. P. (1999). Effects of snowmobile use on snowpack chemistry in Yellowstone National Park, 1998, 99(4148). US Department of the Interior.

- Kaplanidou, K., & Gibson, H. J. (2010). Predicting behavioral intentions of active event sport tourists: The case of a small-scale recurring sports event. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 15(2), 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2010.498261

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Human Communication Research, 30(3), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00738.x

- Lucas, E. (2020). A review of trail-related fragmentation, unauthorised trails, and other aspects of recreation ecology in protected areas. California Fish and Wildlife, 95.

- Margaryan, L., & Fossgard, K. (2021). Visual staging of nature-based experiencescapes: Perspectives from Norwegian tourism and event sectors. In P. Fredman, & J. V. Haukeland (Eds.), Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism (pp. 250–262). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Margaryan, L., & Fredman, P. (2021). Fantastic, magical and grandiose: Natures role in event design. In P. Fredman, & J. V. Haukeland (Eds.), Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism (pp. 237–249). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Marion, J., Arrendondo, J., & Eagelton, H. (2016). Large special Use events: Resource impact evaluation and best management practices. Virginia Tech, College of Natural Resources & Environment. Department of Forest Resources & Environmental Conservation. U.S. Department of the Interior.

- Martin, R. H., & Butler, D. R. (2021). Trail morphology and impacts to soil induced by a small mountain bike race series. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 35, 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2021.100390

- Mascarenhas, M., Pereira, E., Rosado, A., & Martins, R. (2021). How has science highlighted sports tourism in recent investigation on sports’ environmental sustainability? A systematic review. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 25(1), 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2021.1883461

- McCullough, B. P., Bergsgard, N. A., Collins, A., Muhar, A., & Tyrväinen, L. (2018). The impact of sport and outdoor recreation (friluftsliv) on the natural environment. MISTRA.

- Musselman, R. C., & Korfmacher, J. L. (2007). Air quality at a snowmobile staging area and snow chemistry on and off trail in a Rocky Mountain subalpine forest, Snowy Range, Wyoming. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 133(1), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-006-9587-9

- Newsome, D. (2014). Appropriate policy development and research needs in response to adventure racing in protected areas. Biological Conservation, 171, 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.01.008

- Ng, S., Leung, Y., Cheung, S., & Fang, W. (2017). Land degradation effects initiated by trail running events in an urban protected area of Hong Kong. Land Degradation & Development, 29(3), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2863

- Olofsson, J., Hulme, P. E., Oksanen, L., & Suominen, O. (2005). Effects of mammalian herbivores on revegetation of disturbed areas in the forest-tundra ecotone in northern Fennoscandia. Landscape Ecology, 20(3), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-005-3166-2

- Perić, M., Vitezić, V., & Badurina, JĐ. (2019). Business models for active outdoor sport event tourism experiences. Tourism Management Perspectives, 32, 100561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100561

- Pettersson, R. (2004). Sami tourism in northern Sweden: Supply, demand and interaction (Doctoral dissertation, Umeå University).

- Pettersson, R., & Jonsson, A. (2022). Turism och regional utveckling. In I. Grundel (Ed.), Regioner och regional utveckling i en föränderlig tid. Ymer Yearbook (pp. 145–162). YMER.

- Ritchie, B. J. R. (1984). Assessing the impact of hallmark events: Conceptual and research issues. Journal of Travel Research, 23(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728758402300101

- SFS. (1971). Rennäringslagen. Näringsdepartementet: Regeringskansliet.

- Sharpley, R., & Stone, P. R. (2020). Socio-cultural impacts of events: meanings, authorized transgression, and social capital. In S. Page & J. Connell (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of events (pp. 155–170). Routledge.

- Skarin, A., & Åhman, B. (2014). Do human activity and infrastructure disturb domesticated reindeer? The need for the reindeer’s perspective. Polar Biology, 37(7), 1041–1054. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-014-1499-5

- Smith-Christensen, C. (2009). Sustainability as a concept within events. In R. Raj, & J. Musgrave (Eds.), Event management and sustainability (pp. 22–31). CABI.

- Stark, S., Strommer, R., & Tuomi, J. (2002). Reindeer grazing and soil microbial processes in two suboceanic and two subcontinental tundra heaths. Oikos, 97(1), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2002.970107.x

- Steven, R., Pickering, C., & Castley, J. G. (2011). A review of the impacts of nature based recreation on birds. Journal of Environmental Management, 92(10), 2287–2294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.05.005

- Stoessel, M., Moen, J., & Lindborg, R. (2022). Mapping cumulative pressures on the grazing lands of northern Fennoscandia. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 16044. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20095-w

- Tolvanen, A., Forbes, R., Wall, A., & Norokorpi, Y. (2005). Recreation at tree line and interactions with other land-use activities. In F. E. Wielgolaski (Ed.), Plant ecology, herbivory, and human impact in Nordic mountain birch forests (pp. 203–217). Springer-Verlag.

- Toscani, A. C., Macchion, L., Stoppato, A., & Vinelli, A. (2022). How to assess events’ environmental impacts: A uniform life cycle approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(1), 240–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1874397

- Ullring, U. E. (1989). Forvaltning av stislitasje – en utprövning av to vegetasjonsökologiske metoder i Femundsmarka og Långfjället. Universitetet i Trondheim.

- Viskari, E. L., Rekilä, R., Roy, S., Lehto, O., Ruuskanen, J., & Kärenlampi, L. (1997). Airborne pollutants along a roadside: Assessment using snow analyses and moss bags. Environmental Pollution, 97(1-2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0269-7491(97)00061-4

- Vistnes, I., & Nellemann, C. (2001). Avoidance of cabins, roads, and power lines by reindeer during calving. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 1(4), 915–925. https://doi.org/10.2307/3803040

- Wall Reinius, S. (2006). Tourism attractions and land use interactions: Case studies from protected areas in the Swedish mountain region. Stockholm University.

- Wall-Reinius, S. (2012). Wilderness and culture: Tourist views and experiences in the Laponian world heritage area. Society & Natural Resources, 25(7), 621–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2011.627911

- Wall-Reinius, S., Ankre, R., Dahlberg, A., Bodén, B., & Laven, D. (2016). Intressemotsättningar och utmaningar i multifunktionella landskap: Studier kring buller, vindkraft och naturskydd i Jämtlandsfjällen. ETOUR.

- Wall-Reinius, S., Prince, S., & Dahlberg, A. (2019). Everyday life in a magnificent landscape: Making sense of the nature/culture dichotomy in the mountains of Jämtland, Sweden. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 2(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619825988

- Wallstam, M. (2022). Panem and Circenses: Framing social values of events for policy context. Mid-Sweden University.

- Wallstam, M., & Kronenberg, K. (2021). The role of major sports events in regional communities: A spatial approach to the analysis of social impacts. Event Management, 26(5), 1025–1039. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599522X16419948390781

- Weed, M. (2014). Towards an interdisciplinary events research agenda across sport, tourism, leisure and health. In S. Page, & J. Connell (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of events (pp. 75–89). Routledge.

- Whitford, M. (2009). A framework for the development of event public policy: Facilitating regional development. Tourism Management, 30(5), 674–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.10.018

- Yuan, Y. Y. (2013). Adding environmental sustainability to the management of event tourism. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 7(2), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-04-2013-0024