ABSTRACT

Popular culture can be given representation in the form of attractions and institutions. This paper explores the impact of such popular culture institutions within the context of place branding research. The aim is to contribute to developing a framework for assessing and harnessing indirect value of tourist attractions in place branding. Tom Tits Experiment Science Center serves as the focal point in this abductive qualitative case study. The literature review is focused on exploring the concept of value within place branding and associated fields, particularly, zooming in on the concept of indirect value and a bottom-up approach. Drawing from this cross-disciplinary literature review and interviews with key stakeholders within Tom Tits’ network, a framework that encompasses nine indirect value categories is presented. The case of Tom Tits is used to illustrate a single stakeholder’s potential value contributions across the identified categories. The study emphasizes the complex collaborative nature of places and encourages further exploration of the evolving topic of popular culture institutions and their influence in place branding. Additionally, it supports a shift in perspective regarding the assessment, development, and branding of places, highlighting the role of key stakeholders as value drivers.

Introduction

The theoretical concept of place branding is traditionally linked to strategic marketing and branding literature, embracing the idea that places, despite their complex nature, could be managed and promoted in a similar top-down manner as corporations (Cassinger et al., Citation2021; Kavaratzis, Citation2005; Kotler et al., Citation1993; Vuignier, Citation2017). Over the past decades, a more multifaceted stakeholder-oriented and networked approach, embracing transdisciplinary research efforts, has evolved, especially within Nordic place branding research (Cassinger et al., Citation2019; Cassinger et al., Citation2021). Echoing the abstract nature of places and place branding, the research field allows for a broad and varied range of research topics, however, it also struggles with a lack of conceptual clarity and diverging definitions (Vecchi et al., Citation2021; Vuignier, Citation2017).

One example of conceptual unclarity concerns the very key concept of place. In the context of tourism, destination, country/nation, region, city, or location are more often used as alternate concepts to describe and geographically define what we here refer to as place (e.g. Hanna & Rowley, Citation2008; Kerr, Citation2006; Ritchie & Ritchie, Citation1998). Making a distinction between these concepts and associated branding vocabulary may seem like pure semantics (Hanna & Rowley, Citation2008). Still, place and place branding are considered more holistic concepts than, for example, destination and destination branding (e.g. Briciu, Citation2013; Kerr, Citation2006). In this article, we use the concept of place branding to widen the perspective from destination branding, leaning towards a definition such as Anholt's “the practice of applying brand strategy and other marketing techniques and disciplines to the economic, social, political, and cultural development of [places]” (cited in Kerr, Citation2006, p. 278). Place branding includes all activities involved in cultivating favorable living, tourism, investments, economy, and an attractive image of a place (Che-Ha et al., Citation2016; Vecchi et al., Citation2021).

Another example of conceptual ambiguity refers to the concept of value in place branding. While this concept is frequently mentioned in place branding research (e.g. Cleave & Arku, Citation2017; Florek et al., Citation2019; Zenker & Martin, Citation2011), there seems to be limited consensus regarding the definition of value, what components of a place brand could and should be measured, and how to assess the effects, effectiveness, and value of place branding efforts. Today, modern assessment methodologies and tools enable increasingly customized data collection and subsequent personalized branding narratives and visitor experiences. Assessing value on different levels has become a crucial part of any strategic branding decision. According to Florek et al. (Citation2019, p. 563) “the effectiveness measurement of a [place] brand should be treated as a strategic endeavour equally important as the development of the brand strategy itself”. However, the issue of measuring effects, effectiveness and value in place branding needs to be explored further, aiming at a more unified understanding from a theoretical as well as pragmatic perspective (Cleave & Arku, Citation2017; Florek et al., Citation2019; Zenker & Martin, Citation2011).

The aim of this study is to contribute to a framework for assessing and harnessing indirect value of single stakeholders, such as local tourist attractions, as part of place branding. The proposed framework is rooted in a literature review on the concept of value within the fields of destination and place branding and related research fields, highlighting and exploring specifically the relevance of a bottom-up approach and the concept of indirect value. An abductive research approach, embracing an empirical case study of Tom Tits Experiment Science CenterFootnote1 located in Södertälje, Sweden, is applied to illustrate potential value contributions of a single tourist attraction from a place branding perspective, and to further develop the indirect value categories identified in the proposed framework.

Literature review

The literature review embraces three key stages. The first stage explores the concept of value in prior research within the field of destination and place branding. Due to the complexity of the concept, attempting to find a universal definition is deemed a fool’s errand. Therefore, focus lies on exploring how value can be created, perceived, and measured as part of place branding activities. The second stage explores a shift of perspective in the understanding of value and assessment methodology within place branding. The initial stage of the literature review shows that the traditional top-down approach needs to be challenged when moving into a stakeholder-centric approach. The proposed bottom-up approach highlights the importance of stakeholder co-creation and stakeholder inclusion in place branding processes and measures. The third stage further explores the concept of value by drawing inspiration from related research fields. The previous stages of the literature review reveal a need for broadening the scope, specifically by investigating concepts such as direct and indirect value.

Value in destination and place branding

Places, regardless of scale or adopted perspective, are complex in nature (e.g. Creswell, Citation2004). Consequently, place branding is generally accepted as a complex process that simultaneously caters to varied aims and target groups, for example, local residents, visitors, tourists and businesses (Kavaratzis, Citation2005; Trueman et al., Citation2004). The need for pertinent measurement and assessment on different levels as part of strategic place branding decisions and management has never been greater (Cleave & Arku, Citation2017; Florek et al., Citation2019; Giannopoulos et al., Citation2021).

Within destination branding studies, the literature review reveals a focus on customer-centric value and measures. Most commonly, focus lies on destination brand image and its effects on destination choice processes and after-purchase behaviors (e.g. Ashton, Citation2015; Bigné et al., Citation2001; Chen & Tsai, Citation2007; Giannopoulos et al., Citation2021). Key factors in these studies are perceived value and quality and customer satisfaction as antecedents of behavioral intention (e.g. Ashton, Citation2015; Chen & Tsai, Citation2007; Kashyap & Bojanic, Citation2000). Based on an extensive literature review on the concept of brand value in destination branding, Ashton (Citation2015), establishes five components of value that are driving consumer decision-making: (1) functional value, (2) social value, (3) emotional value, (4) epistemic value, and (5) conditional value. These components require the involvement of different stakeholders as part of creating an attractive brand image (Ashton, Citation2015). More recent studies also highlight similar co-creation and stakeholder-centric perspectives (e.g. Giannopoulos et al., Citation2021; Lund et al., Citation2020).

Looking beyond destination branding and the tourism literature, similar trends also appear within place branding research. For example, Zenker and Martin (Citation2011), highlight the importance of viewing place branding as an integrated management tool, where measuring the effects of branding activities is key in the strategic planning process. However, they also found that extensive success measurement is seldom embraced in practice due to high costs and comprehensive methodology. Furthermore, they propose a performance evaluation framework where different approaches and factors are combined for the purpose of attaining richer information. This framework includes a customer-centric dimension where value is measured in terms of citizen equity and citizen satisfaction, and a brand-centric dimension where value is measured in terms of brand value drivers and place brand equity (Zenker & Martin, Citation2011). More recent studies also coincide with the notion that a variety of measures and factors need to be considered when assessing effects and success in place branding (e.g. Cleave & Arku, Citation2017; Florek et al., Citation2019; Kladou & Mavragani, Citation2015; Vuignier, Citation2017).

Cleave and Arku (Citation2017) found that most assessment methodology in this field features the concept of place brand equity, including measures such as citizen satisfaction, place loyalty, enjoyment, place image, and financial exchange. Consumer-based equity, financial-based equity, and the concept of sense-of-place are also addressed as potential value dimensions (Cleave & Arku, Citation2017; Zenker et al., Citation2013). While these factors are important to consider, Cleave and Arku (Citation2017), suggest that the complexity of today’s places and societies, and the increased focus on sustainability, call for considering factors beyond traditional economic indicators. Traditional performance reports and value measures are insufficient in articulating enough relevant evidence for strategic place branding decisions.

Similarly, Florek et al. (Citation2019) address the complexity of measuring value in place branding, identifying similar approaches, concepts and measures as mentioned above. However, their study shows skepticism towards a unified value measurement methodology that could apply to any place. Rather, they stress a need for a flexible framework, covering a catalogue of methods and indicators, from which each place could choose those that are relevant to their specific context in their value assessment (Florek et al., Citation2019). To develop such a framework a wider cross-disciplinary stance is needed.

Towards a bottom-up approach

Recent studies highlight the importance of stakeholder co-creation and stakeholder inclusion in place branding and storytelling (e.g. Cassinger et al., Citation2021; Kavaratzis et al., Citation2017; Stoica et al., Citation2021). Lundberg and Lindström (Citation2020), argue for a holistic approach that recognizes the role of advanced networks of stakeholders and inter-sectoral collaborations. Similarly, Kemp et al. (Citation2012) and Vecchi et al. (Citation2021) highlight the importance of engaging internal stakeholders in the brand-building process. A too narrow focus and a lack of collaboration between stakeholders may create challenges in sustainable destination management and place branding (Lindström, Citation2018; Lundberg & Lindström, Citation2020).

Further, Giannopoulos et al. (Citation2021), explores hierarchies within the complex place branding ecosystem, acknowledging that all stakeholders within the ecosystem are interlinked. Thus, each stakeholder is affecting, and is affected by, the other stakeholders (Giannopoulos et al., Citation2021). Managing this complex and interlinked ecosystem in the traditional top-down manner may be challenging. Switching perspectives towards a more holistic approach or a bottom-up approach, allows for new opportunities in exploring the potential of a single stakeholder in creating value not only for itself, but for the entire place and the brand image, as part of sustainable place branding. Central stakeholders in this value creation process can be identified as value drivers.

Prior studies, for example, Mariutti and Engracia Giraldi (Citation2021), define value drivers as activities, initiatives, and infrastructures, which influence the value of a place brand. Mariutti and Engracia Giraldi (Citation2021) identify and explore six key value drivers, which need to be strategically monitored and aligned: government initiatives, stakeholders’ perceptions, residents’ engagement, news media, social media, and real-data indexes. However, they also highlight the necessity of not only considering stakeholders’ perceptions, but truly engaging central stakeholders in adding value to the place (Mariutti & Engracia Giraldi, Citation2021). This study highlights stakeholders such as tourist attractions and cultural institutions as value drivers in place branding.

Culture in the form of history, architecture, cultural sites, and events are a central part of any location’s identity (Kunzmann, Citation2004), offering a multitude of opportunities for place branding and associated storytelling. Such narratives provide the place brand with uniqueness, personality, and emotional connection (Lund et al., Citation2020). An attractive place branding narrative, rooted in local culture, not only contributes to attracting visitors and tourists to the place, but it may also have an impact on the local population, local industries and communities, and urban planning activities (e.g. Evans, Citation2001).

Today, popular culture expressions, the entertainment industry, new technologies and media play a central role in shaping people's perceptions of places. Popular culture is perceived as a reflection of the established popularized culture (Parker, Citation2011). Popular culture is characterized by its accessibility or availability and can be studied in different societies and in different groups within these (Boukas & Ioannou, Citation2019; Strinati, Citation2004). It is deeply embedded in different elements of our lived life (Boukas & Ioannou, Citation2019), and can be given representation in the form of attractions and institutions (Boukas & Ioannou, Citation2019; Edensor, Citation2016). Boukas and Ioannou (Citation2019), argue that popular culture has a direct relationship also to, for example, museums, as their role as exhibitors of cultural elements can be seen as an extension of popularized phenomena.

In recent years, the topic of popular culture institutions and Popular Culture Tourism (PCT) has gained more interest within place branding research. A rough distinction can be made between event-based and attraction-based studies within this discipline (Thorne, Citation2009). In general, popular culture events or related special events have featured in the forefront of place branding studies (Brokalaki & Comunian, Citation2019; Cudny, Citation2019; Vuignier, Citation2017). However, as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic, which had a severe effect on the event industry in 2020–2021, due to limitations and restrictions (Kamata, Citation2022), the attraction-based perspective is now gaining more interest. Zooming in on interesting tourist attractions and institutions within the cultural sector and the popular culture arena as value drivers calls for a novel way of approaching the concept of value within the place branding context.

Direct and indirect value

As an attempt to widen the scope, we turn our gaze towards related research fields such as cultural economics. Within this field, we highlight Sacco’s culture 3.0 model as an interesting approach for studying value in the context of cultural institutions within place branding (Sacco, Citation2013, Citation2016; Sacco et al., Citation2008). Sacco (Citation2016) identifies cultural institutions, such as museums, as participative platforms and argues that culture’s social contribution should not be limited to measuring direct and short-term effects. Such creative and cultural activities have the potential to contribute to cultural participation, which strengthens and develops spillover value across dimensions such as innovation, welfare, sustainability, social cohesion, lifelong learning, and local identity (Sacco, Citation2013; Sacco et al., Citation2008). Thus, value in the context of cultural institutions needs to be assessed beyond direct contributions seen from practice. This rationale can be traced back to the early 1990s, when Hansen (Citation1995), studied culture’s contribution to creativity in maintaining and developing new industries and welfare.

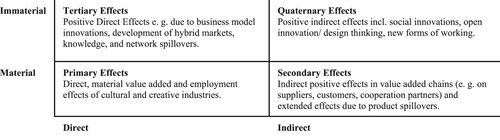

Furthermore, Arndt et al. (Citation2012) proposed a model that summarizes macroeconomic effects of the creative industry. The model demonstrates how cultural participation contributes to and reinforces creativity and innovation on four levels, as seen in . Although this model was developed within a different context, the value levels defined therein are of interest also from a place branding perspective. Specifically, the model recognizes the opportunities associated with defining value across more dimensions than those traditionally used in place branding, such as material and immaterial as well as direct and indirect effects. While prior place branding studies briefly mention similar value categories (e.g. Cleave & Arku, Citation2017; Florek et al., Citation2019; Vuignier, Citation2017; Zenker et al., Citation2013), there is a potential to include this reasoning more extensively within this context.

Figure 1. A model for primary to quaternary effects (adapted from Arndt et al., Citation2012, p. 30).

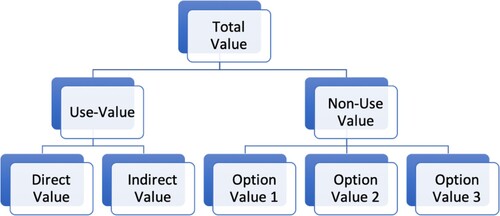

Also, the concepts of use value and non-use value, originally rooted in the field of environmental economics, can be acknowledged. These concepts have been adapted to the field of culture and cultural institutions by, for example, Andersson et al. (Citation2012), who present a schematic model that illustrates different use and non-use value dimensions, which together form the total value for a cultural institution (see ). In this context, use value can be further divided into direct and indirect use value; direct use value relates to customers’ core experience of a cultural institution, whereas indirect use value relates to experiential values outside the cultural institution, for example, before or after visiting the cultural institution (Andersson et al., Citation2012). In addition to these customer-centric use value dimensions, this perspective suggests that the non-use value dimensions need to be considered to a greater extent. Non-use value refers to effects, positive and negative, that arise from the mere existence of the cultural institution, which also affects, for example, people who are not visitors (Andersson et al., Citation2012).

Figure 2. A model for use values and non-use values (adapted from Andersson et al., Citation2012, p. 224).

Andersson et al. (Citation2012) summarize different methods for measuring non-use value. For example, the Hedonic Price Method, first introduced by Rosen (Citation1974), involves identifying value in other areas that can be assumed to have a relation to the resource, e.g. prices of homes and properties in the vicinity of the area. The Travel Cost Method considers the willingness to pay among people interested in visiting the place. The Contingent Valuation Method concerns the price that stakeholders are willing to pay for accessing and preserving, e.g. a natural scenic area for future generations, or for acknowledging the fact that there is a cultural institution in the city even though you cannot or choose not to visit it yourself (Andersson et al., Citation2012). When assessing the total value of a cultural institution from a place branding perspective, both use-value and non-use value need to be considered.

The multidimensional nature of cultural and creative activities implies a certain level of complexity in assessing value (Throsby, Citation2010). This is especially true when interpreting value derived from cultural institutions as this is an overlapping patchwork that can be addressed differently depending on theoretical perspective and indicators of interest. Turning towards classical theorists such as Lefebvre and his theory on production of space can serve as a theoretical point of departure for how to interpret place value as part of a dialectic process for value-transformation (e.g. Lefebvre & Nicholson-Smith, Citation1991).

Towards a framework for indirect value

Rooted in the notion that a wide and flexible framework for assessing value in place branding is called for (Florek et al., Citation2019), supported by the emerging bottom-up stakeholder-centric perspective (e.g. Cassinger et al., Citation2019, Citation2021; Giannopoulos et al., Citation2021), and inspired by the dimensions of value identified in the latter stage of the literature review (e.g. Andersson et al., Citation2012; Arndt et al., Citation2012; Sacco, Citation2016), we propose an outline for a framework for assessing value in the place branding context, according to the following preconditions: (1) The focal point is a single stakeholder, a value driver, within the place branding network. In this study, we explore the potential of a tourist attraction, such as a science center, as a value driver, generating spillover/indirect value for other stakeholders, the place, and the place brand. (2) Direct value and related measurement tools (for example, performance reports and economic indicators directly linked to the stakeholder and its everyday business), are assumed to be an already accessible part of strategic assessment and decision-making in place branding practice. Consequently, focus lies on indirect value dimensions, which we believe are often either ignored or overlooked due to their complexity and potential additional costs derived from identifying and using valid assessment indicators and methods. (3) The framework could be adapted to focus on different types of value drivers within the place branding ecosystem; the value categories and subsequent measures can be altered according to their relevance for each specific stakeholder and/or place.

The proposed framework features nine (9) indirect value categories: business value, tourism and visitor value, place brand value, learning and competence development value, knowledge development value, attitude value, individual value, sociocultural value, and relationship and network value.

Business value includes, for example, spillover value in terms of increased investments, spendings, and opportunities for nearby businesses and organizations, generated through their proximity to the value driver. Tourism and visitor value, includes spillover value derived from visitors to the value driver, who also engage in additional activities during their visit, for example, visiting other attractions, hotels, restaurants, tourism services, etc. Place branding value is generated by the value driver contributing to developing the place’s branding narrative and identity and strengthening the brand image and awareness.

Learning and competence development value refers to value generated by the value driver for nearby educational and learning environments, through providing opportunities for knowledge and competence development for individuals. Related to this value category, knowledge and development value, considers knowledge in a broader sense and entails, for example, opportunities derived from the value driver in terms of strengthening collaborations between innovative initiatives within industry and academia.

The category of attitude value entails a value driver’s potential in shaping attitudes, supporting intellectual growth, fostering social coherence, and promoting a sense of place and community, etc. This value category is closely connected to many of the others, especially, individual value, which embraces value for the individual that emerges from the value driver and the surrounding environment, and sociocultural value, which refers to, for example, improved livability in terms of promoting social interaction beyond the value driver and fostering community-building for overcoming social challenges. Also, relationship and network value, captures the potential in existing and new alliances and connections between the value driver and various groups and stakeholders.

The framework draws inspiration from indirect value dimensions identified in the literature, primarily those posited by (Sacco et al., Citation2008; Sacco, Citation2013). Florida’s (Citation2002) work on cultural institutions’ role in regional development and place branding contributes to the framework by promoting aspects like creativity, attracting talent, enhancing social cohesion, and facilitating knowledge exchange for a knowledge-based economy. Investing in cultural institutions, supporting programming, and integrating them into the urban fabric is necessary to harness such dimensions of value (Florida’s, Citation2002). Other central studies sources used for inspiration are Andersson et al. (Citation2012), Anholt (Citation2010), Arndt et al. (Citation2012), Boukas et al. (Citation2019), Conradty and Bogner (Citation2018), Guo et al. (Citation2022), Hansen (Citation1995) and Ritchie and Ritchie (Citation1998).

Furthermore, applying an abductive and iterative research approach, the categories were further developed and adapted based on insights derived from the empirical case study. It should also be noted that the categories are interconnected and contribute to each other. The framework highlights a continuous interplay between them that can enhance or diminish value.

Methodology

Case study methodology involves the investigation of one or more real-life cases to capture its complexity and details (Yin, Citation2014). The object of study is the “case” which should be “a complex functioning unit” (Johansson, Citation2007, p. 48). Case study research is often associated with qualitative enquiry (Creswell, Citation1998). This study embraces an abductive reasoning (in accordance with e.g. Piekkari & Welch, Citation2018), even though case study methodology traditionally stems from the positivist tradition (Yin, Citation2014). Abductive case studies are characterized by continuous iteration and “the original framework is successively modified, partly as a result of unanticipated empirical findings, but also of theoretical insights gained during the process” (Dubois & Gadde, Citation2002, p. 559). This empirical case study features Tom Tits as a value driver in the context of Södertälje’s place branding. The objective is to explore the practical relevance of the identified indirect value categories and to further adapt and develop the scope of the value categories and the entire framework.

The case of Tom Tits

Tom Tits is a science center located in Södertälje, Sweden, which was founded in 1987. While Tom Tits is most often experienced as an amusement park for families, the main aim is to contribute to the development of knowledge and interest in science and technology among young people. This is done through exciting, pleasurable, and hands-on learning experiences.

As a member of the Swedish Science Centers organization, Tom Tits also develops and promotes the industry's interests on a wider scale, by conducting public education and encouraging lifelong learning within the STEAM educational realm (Lind & Sandberg, Citation2021; Telge AB, Citation2020b). STEAM is a development of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics), where Arts and Humanities have been included to the technical and scientific subjects in order to (1) make learning science more fun, playful, and creative (Yakman & Lee, Citation2012), and (2) foster creativity, imagination and critical thinking also in the long run (Conradty & Bogner, Citation2018). Furthermore, embracing the STEAM approach, also encourages and enables collaboration with universities and other educational institutions in the surrounding area (Guo et al., Citation2022).

The decision to focus on Tom Tits is motivated by two key factors. First, the potential in exploring science centers and similar tourist attractions as key stakeholders and value drivers in place branding. While science centers are not frequently featured in place branding research, we found that such establishments have been found to play a significant role in evolving the concept of cultural experiences and museums (e.g. Boukas & Ioannou, Citation2019; Koster, Citation1999), in serving as laboratories for learning on individual as well as societal levels (e.g. Salmi, Citation2003), and in attracting tourists to its location (e.g. Beetlestone et al., Citation1998; Boukas & Ioannou, Citation2019). While most studies on the relevance of science centers within the place branding context were made some decades ago, newer studies (e.g. Boukas & Ioannou, Citation2019) support the notion that popular culture institutions may contribute to, for example, regional development in terms of bridging the gap between tourism, local businesses, industry, and educational and scientific institutions.

Second, prior collaborations around Tom Tits granted access to empirical data. The interviews used in this empirical case study were conducted in 2020–2021 as part of a larger consultant project commissioned by Telge AB.Footnote2 A report based on the consultant project was published in 2021 (Lind & Sandberg, Citation2021). The project group from the consultant study has granted us access to the empirical data and the results are published here with their consent.

Qualitative interviews

Semi-structured interviews are widely used for data collection in qualitative research (Creswell, Citation1998). For this case study, 15 semi-structured interviews were conducted with key actors in the Tom Tits organization, and the interrelated community. A sampling strategy which can be described as purposive sampling (e.g. Onwuegbuzie & Leech, Citation2007) is applied, i.e. informants are chosen based on their position within the network and their knowledge about the researched phenomenon. The informants are representatives from Tom Tits, local politics and businesses, and the trade and tourism industry in Södertälje. Interviews were also conducted with teachers and representatives of academia, the Swedish National Agency for Education, and the Swedish Science Centers organization. For an overview of the informants, see .

Table 1. Overview of informants.

The aim of the qualitative interviews was to investigate the perspectives and experiences of the informants on Tom Tits in the context of the city of Södertälje and its surrounding area from a strategic branding decision-making perspective. The interviews took place between November 2020 and January 2021. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, face-to-face interviews were not feasible, and therefore, the interviews were conducted over the phone and supplemented with email correspondence. All interviews were conducted and transcribed in Swedish, and the citations have been translated into English for this article. Although all informants agreed to have their names published as part of the study, the results and citations from the interviews have been anonymized for this article.

Data analysis

The case study does not serve as a tool for proving or disproving the theoretical framework, rather as a means of illustrating potential indirect value contributions of a specific value driver and generating new ideas for further developing the value categories and the entire framework. The indirect value categories inspired by the literature review served as a guideline for coding the empirical data, and as mentioned, these were altered and further developed in an iterative manner throughout the coding process. The final coding schema included the nine indirect value categories, aiming at exploring the practical relevance of these categories by identifying contributions of Tom Tits in each category.

Results

In the following sections, the results from the interviews are presented and discussed according to the central indirect value categories in the proposed framework. However, some categories have been combined, for example, learning and competence development value is combined with knowledge development value and attitude value, tourism and visitor value is combined with local business value, and individual value is combined with sociocultural value. The combination of some of the value categories partly derives from quite limited empirical data. However, this adaptation may also give an indication to the pragmatic application of the framework, which allows for flexibility in adapting the central categories according to each specific place and case.

Furthermore, in the process of analyzing the interviews, we realized that some of the informants held a biased position and showed tendencies of exaggerating the importance of Tom Tits in their answers. Therefore, prior studies and reports (Lind & Sandberg, Citation2021; Resurs, Citation2020; Södertälje kommun, Citation2015a; Södertälje kommun, Citation2015b; Telge AB, Citation2020a, Citation2020b) are used in the following sections to supplement the, at times, limited and somewhat biased interview data. For an overview of Tom Tit’s potential in terms of indirect value contributions in each category, see .

Table 2. An overview of Tom Tit’s indirect value contributions.

Place branding value

As a general background it is worth mentioning that the city of Södertälje has struggled with a negative image, characterized by social divides, crime, and lack of awareness due to the city’s proximity to Stockholm in the past decades (Lind & Sandberg, Citation2021; Södertälje kommun, Citation2015a). The role of Tom Tits and its potential for improving the image of Södertälje in recent years was clearly emphasized across the board in the interviews.

Tom Tits, located in Södertälje, is a major tourist attraction for all of Sweden. It's important for the local community, Stockholm, and the entire country. It's well-known, visited by hundreds of thousands of children every year, and provides a space for exploration. (Informant 14, 2021)

Furthermore, most of the informants argue that Tom Tit’s own strong brand and positive brand image is of great significance to the branding of Södertälje.

Tom Tits is a very positive brand. It is very valuable for the city itself, and especially for the city center. From the city center’s perspective, it is one of the top experiences together with Sydpoolen and Torekällberget. (Informant 6, 2020)

Tourism, visitor, and business value

The informants touch upon various categories of local businesses and tourism-related services that benefit from the large quantities of tourists and day-visitors that Tom Tits attracts. The value is expressed in terms of both monetary revenue and increased brand awareness. People who visit Tom Tits also consume goods and services from other local businesses and service providers, for example, hotels, restaurants, shops, and other tourist attractions. However, informants representing both the hospitality industry and Södertälje’s business development center, also highlight the challenge of getting people to stay in the city for longer, before and/or after visiting Tom Tits. They see this as an important area for continuous development and give suggestions for how to involve Tom Tits as a key collaborator.

It would be valuable to have pop-up activities by Tom Tits throughout the year, such as utilizing shopping windows, public spaces, and the waterfront of Maren in the city center as they have done. These satellite activities can support both the science center, the local business life, and the city life in Södertälje. (Informant 5, 2020)

Tom Tits is located in the northern part of Södertälje's city center, an area undergoing significant development at the moment, that is accommodating the KTH (KTH Royal Institute of Technology) campus, hub, several companies, hotels, shopping opportunities and boat traffic. Informants representing the tourism industry and the local business community believe that Tom Tits plays an important role in this development.

There is an exciting development in the northern part of Södertälje's city center where Tom Tits is located, and it will have a higher tax value. I do not think it is possible to assess the individual contribution value of Tom Tits to this development, but my perception is that Tom Tits is significant in the whole context. (Informant 6, 2020)

Learning, competence and knowledge development and attitude value

One of the more notable value contributions of Tom Tits mentioned in the interviews, is the science center’s efforts in developing knowledge and interest in science and STEAM among children and young people. In addition to the actual learning experience taking place at the science center, Tom Tits generates expectations before the visit and memories to share afterwards, which contributes to strengthening Södertälje's image and fostering a positive attitude towards science as these children and youngsters share their experiences with their friends, families, and relatives.

The effort to get children and young people interested in science and technology is truly invaluable. In Sweden, it's not a priority, as many are aspiring to become reality show celebrities instead of pursuing an education in what is the backbone of Sweden. (Informant 8, 2020)

Tom Tits provides value for all teachers and preschool teachers who use it. With 3500 employees, including 1000 in preschool, this is significant for both the brand and for enhancing the quality of their work. It holds a lot of importance for these individuals. (Informant 13, 2021)

Tom Tits is a reliable workhorse for me. I know that when I visit, it will be a good experience. It's well-planned and easy for students to navigate, with no unexpected issues. […] I visit Tom Tits frequently, around 8–10 times per semester. On occasion, we've been invited to try out new labs, which they use for testing. Another benefit is that Tom Tits has expertise in working with children on the autism spectrum. (Informant 7, 2020)

According to the informants representing educational institutions, Tom Tits strengthens the municipality's brand among teachers and the attitudes towards science among younger age groups. Thus, in addition to generating positive attitudes towards the science center itself and the city of Södertälje, Tom Tits also contributes with value in terms of developing positive attitudes towards science and technology, not only among children and youngsters in Södertälje, but among everybody who visits the science center.

Given the current situation in the US with the proliferation of fake news and the multitude of choices, Tom Tits is even more crucial now than ever before. With the overwhelming amount of information in the digital age, where we're bombarded with messages that are influenced by what we choose to follow, exhibitions based on science that Tom Tits is creating will play a crucial role in educating children, young people, and their parents on the importance of science. (Informant 10, 2020)

Individual and sociocultural value

The informants agree on the fact that Tom Tits provides value on an individual level by providing fun and interactive learning experiences for people of all ages, stimulating curiosity, joy and a sense of community. It is stressed how important it is that, particularly, children and young people can visit such a place and learn about science and technology in a fun and experience-based manner.

I really think it's amazing that there is such an institution as Tom Tits in Södertälje. That the city has something to offer its citizens and something which provides education. It's good that you can have fun, but it is also good that a city provides something to learn from, an approach to science that can successfully be combined with something pleasurable. (Informant 12, 2021)

[The value lies in] experiencing something together, in a time characterized by different bubbles and segregation. Especially in Södertälje. Usually, you do not take part in joint activities. You live different kinds of lives. (Informant 12, 2021)

Relationship and network value

In the interviews, Tom Tit’s contributions in developing and promoting cross-boundary and cross-industry relationships and networks were frequently mentioned. For example, the informants representing KTH, highlight Tom Tit’s collaboration with KTH Campus Södertälje, which connects Södertälje nationally to a broader network of other science centers and partners in academia.

Furthermore, the informants from the significant industries in Södertälje underscore the importance of the “softer values” embodied by Tom Tits, which not only help to put the city on the map from the perspective of both innovation and traditional industry, but also contribute to the city’s overall development. These informants have collaborated with the science center in various capacities. They see potential for other industries to emerge and evolve in conjunction with Tom Tits.

Having more meaningful partnerships with industries in Södertälje would be intriguing, particularly exhibitions that highlight the work they do. Currently, Astra [Zeneca] and Scania are the major companies that are involved, but it's worth considering that Södertälje aims to become a hub for food as well. There's great potential for exhibitions on food, which is inherently tied to science and technology. (Informant 8, 2020)

Discussion and conclusions

Considering the identified value categories and the practical examples presented and discussed above, we conclude that Tom Tits contributes with indirect value across many different dimensions for Södertälje and the surrounding region. For a place like Södertälje, having struggled with a somewhat negative brand image, the positive effects of Tom Tits were described in the interviews as invaluable. We argue that Tom Tits is an important institution within the popular culture arena due to its accessibility, its focus on scientific and social development, and its primary target group, i.e. children and young people. The science center is a key stakeholder in Södertälje and, therefore, a relevant value driver in the place branding context. In future development of Södertälje’s place brand, further inspiration could be drawn from Tom Tits attractive brand image, from indirect values emerging from the educational STEAM focus and experiences, from the joy of discovery among children and young people that the science center provides, and from the collaboration with educational institutions and other partners on different levels.

The challenge, however, which all tourist attractions face, is to continuously stay up to date, relevant and attractive for visitors, locals, and partners. In some of the interviews, informants reflected upon the fact that Tom Tits science center's glory days may soon have passed, and it requires a lot of resources to ensure interesting exhibitions that have the capacity to continue to attract visitors and generate value. Addressing this issue, Tom Tits are constantly looking for new and interesting themes, itinerant exhibitors, and exhibitions on themes with popular cultural characteristics (e.g. space, the human body, dinosaurs, and modern technology). Regularly, they also invite popular guests such as entertainers, lecturers, or musicians. Consequently, the lines become increasingly blurred as to what a science center is and what it is not. While the physical space may remain the same, the outreach of this kind of establishment and its offerings can expand beyond the physical walls of the science center through collaborations and novel digital and hybrid platforms and technological solutions, subsequently affecting the potential indirect value contributions.

Another interesting aspect concerns Tom Tit’s wide network of collaboration with academia as well as the industry. The science center could be described as and further developed into a regional (and why not national, or even international) “greenhouse”, “node” or “hub” for competence and knowledge development. Again, this could be used for strengthening the place brand further and for attracting new businesses, creating new business opportunities, and igniting new collaborations around science and knowledge creation. The already established proximity to different universities can be a key factor in further developing Södertälje into a unique tourist destination (Guo et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, especially the A (arts) in STEAM is an important factor to consider in encouraging young people to learn more about science. However, what the A stands for, i.e. creativity and playfulness, can also be interesting from a broader perspective, as this could be included as a general theme for Södertälje’s place brand. Focusing on STEAM may also help bridging the gap between niche tourism categories such as science and popular science tourism, PCT tourism, educational tourism, experiential tourism, sustainable tourism, community-based tourism, rural tourism, etc. (e.g. Dangi & Jamal, Citation2016; Dodds et al., Citation2018; Hall et al., Citation2014; Ritchie et al., Citation2003).

While this article addresses the potential indirect value contributions linked to a very specific type of tourist attraction, we argue that lessons can be learned from the case study also on a general level. Cities, regions, and other destinations could benefit greatly from exploring indirect, at times even unexpected, value generated by local tourist attractions and cultural institutions as part of their branding strategies. As stated, Tom Tits plays an important role for Södertälje, and the possibilities for further development and integration within place-related narratives are numerous. For some places, however, if the city or region has a stronger position as a tourist destination than the cultural institution, the value-creation process may be reversed. Still, cultural institutions that can combine a historical museum’s qualities with the qualities of a more contemporary entertainment and experience center can contribute to attracting visitors and create indirect value within other categories also in more well-known and established cities, regions, etc. Such attractions should not be overlooked, but decisions need to be made concerning how to integrate these into the place branding process and narrative, and the hierarchy and the roles of stakeholders need to be considered (e.g. Giannopoulos et al., Citation2021).

Another insight gained from this case study refers to hierarchies within the indirect value categories in the proposed framework. We acknowledge that all categories are interconnected, and it may be difficult to separate one from another as they often overlap. We found that assessing these in terms of relevance for the place/value driver in question may be necessary, particularly, if applying this framework in practice with the intent of benefitting from a specific stakeholder and its indirect value contribution in place branding decision-making. This is, for example, the reason why the value categories are presented in a different order in the results section () as opposed to the initial structure. In practice, it may be difficult to assess indirect value across all categories; identifying a hierarchy of the value categories based on the nature of the place/value driver in question may help in finding what is most relevant to focus on. Still, the continuous interplay between all categories need to be considered as changes in the ecosystem can affect all value categories, both in positive and negative regards.

Theoretical implications

In terms of theoretical contributions, there are three main issues that we want to highlight. First, the importance of looking beyond the concept and field of destination branding in exploring the issue of value assessment within this context. We suggest the concepts of place and place branding are more apt in capturing the multifaceted nature of a destination or tourist attraction (which today is no longer necessarily defined by geographical borders, time, or space) and its branding. A cross-disciplinary approach is needed to explore the concept of value in order to tap into new and relevant value dimensions that prior studies within destination and place branding have not covered. Particularly, indirect value emerges as a central part of value assessment within place branding as traditional performance reports and other direct value measures increasingly prove insufficient in articulating enough evidence for strategic place branding decision making. While this has been established also in prior studies, indirect value measures are rarely used in practice due to the complexity of relevant assessment methodology and additional costs (e.g. Zenker & Martin, Citation2011). While the proposed framework does not solve the issue of increased costs for assessing indirect value in practice, it may provide a structure for identifying relevant indirect value categories and subsequent insight into the hierarchies of these.

Second, we argue that the traditional top-down perspective in place branding (as proposed by e.g. Kotler et al., Citation1993) needs to be challenged. A shift of perspective in place branding from the traditional top-down to a bottom-up approach is needed, in line with the emerging multifaceted stakeholder-oriented and networked approach within the field (e.g. Cassinger et al., Citation2019; Cassinger et al., Citation2021). While this approach highlights and encourages stakeholder collaboration and inclusion in place branding, it also allows for exploring the role and value of single stakeholders, such as tourist attractions, in the place branding network. It can be acknowledged that tourist attractions and cultural institutions certainly have been used as part of place branding and place branding narrative before, this is by no means a new phenomenon. However, the issue of addressing single tourist attractions as value drivers and assessing the indirect value and potential of such stakeholders as part of the place branding process is worth exploring further.

Third, the framework proposed here is a contribution towards a more elaborate framework for assessing value in the context of place branding. We acknowledge that the proposed framework is still limited and needs to be developed further, particularly, to be of practical relevance. There cannot be a universal value conception or measurement methodology that could apply to all cities and places and their branding activities, but the results of this case study, can serve as the basis for further exploration of indirect value in place branding. We claim that the identified indirect value categories are well suited as subjects for further exploration and that the proposed framework can serve as a steppingstone towards the flexible catalog of measures and indicators requested by, for example, Florek et al. (Citation2019).

Limitations

The predominant challenges in assessing indirect value refer to the interlinked and overlapping nature of the value categories, the necessity for assessing the situation at a predetermined time and space (disregarding the constantly changing nature of places), and challenges in drawing a line between direct and indirect value contributions. For example, Tom Tit’s mission statement includes increasing interest and knowledge within STEAM. Therefore, the science center’s contributions to developing knowledge and interest in STEAM among children and young people could be seen as a direct value. However, if we limit value assessments to refer only to the core experience at Tom Tits, i.e. use value (Andersson et al., Citation2012), a large portion of potential value assessment is lost. Experiences, expectations, and memories before and after the actual visit to Tom Tits are examples of just as important indirect values (Andersson et al., Citation2012).

These challenges need to be acknowledged also here, as the somewhat limited scope of the empirical study, affected the results in terms of heavily adapted and combined value categories, and subsequent missed opportunities for further development of the framework. A different methodological approach to this study would have allowed for a deeper exploration and illustration of the identified indirect value categories. However, despite the limitations, the empirical study provided interesting and valuable insights throughout the research process, enabling continuous iteration and development of the proposed framework, and new ideas for future studies.

Suggestions for future research

Looking ahead, we stress the importance of flexibility in developing the framework further. Being able to adapt the framework from case to case, based on purpose, conditions, and prerequisites is of utmost importance. For this, a more elaborate exploration of measurement methodology for the different value categories is needed. Within some categories, for example, business, tourism, and branding, insights from prior place branding literature can be applied (e.g. Anholt, Citation2010; Cleave & Arku, Citation2017; Florek et al., Citation2019; Vuignier, Citation2017; Zenker et al., Citation2013). However, the categories related to learning, competence and knowledge development, individual value, and sociocultural call for an exploration of novel assessment methodology. The issue of practical relevance in addressing and developing the assessment methodology is crucial.

In addition to continuing developing the framework, other suggestions for future research include exploring additional key concepts, such as space and time, which determine the conditions for suitable value analyzes. Each value category in the framework could also be explored further, examining their relevance, for example, within different tourism-related research fields such as sustainable tourism, community-based tourism, and educational tourism, from an urban planning perspective, or from a wider ecosystem-oriented approach.

Furthermore, the pandemic has highlighted the sensitivity of stakeholders within cultural and creative industries, especially among those that are dependent on tourists and other visitors. During this period, many tourist attractions have had to fight for their very existence, accelerating the expansion of their operations into, for example, new digital solutions and hybrid media landscapes. This has given reason to broaden the understanding of tourist attractions’ value in their spatial and temporal spaces. In regard to this, exploring value-creation and indirect value within the context of mediatized tourism and experiences also becomes an interesting path for future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 From here on addressed as Tom Tits in the article. For more information about Tom Tits, visit https://www.tomtit.se/en/

2 Telge AB is the organization that owns Tom Tits. Telge AB is owned by the Södertälje municipality.

3 A more elaborate discussion on estimates concerning tourism spending value can be found in Lind and Sandberg (Citation2021).

References

- Andersson, T. D., Armbrecht, J., & Lundberg, E. (2012). Estimating use and non-use values of a music festival. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 12(3), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2012.725276

- Anholt, S. (2010). Definitions of place branding – working towards a resolution. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 6(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2010.3

- Arndt, O., Freitag, K., Knetsch, F., Sakowski, F., & Nimmrichter, R. (2012). Die Kultur- und Kreativwirtschaft in der gesamtwirtschaftlichen Wertschöpfungskette - Wirkungsketten, Innovationskraft, Potenziale. Prognos AG. https://www.kultur-kreativ-wirtschaft.de/KUK/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/2012/kuk-in-der-gesamtwirtschaftlichen-wertschoepfungskette-wirkungsketten-innovationskraft-potentiale-endbericht.pdf?__blob = publicationFile&v = 9

- Ashton, A. S. (2015). Developing a tourist destination brand value: The stakeholders’ perspective. Tourism Planning & Development, 12(4), 398–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2015.1013565

- Beetlestone, J. G., Johnson, C. H., Quin, M., & White, H. (1998). The science center movement: Contexts, practice, next challenges. Public Understanding of Science, 7, 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/096366259800700101

- Bigné, J., Sanchez, M., & Sanchez, J. (2001). Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tourism Management, 22(6), 607–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00035-8

- Boukas, N., & Ioannou, M. (2019). Visitor experiences of popular culture museums in islands: A management and policy approach. In C. Lundberg & V. Ziakas (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of popular culture and tourism (pp.450-463). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315559018-39

- Briciu, V.-A. (2013). Difference between place branding and destination branding for local brand strategy development. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov, 6(55), 9–14.

- Brokalaki, Z., & Comunian, R. (2019). Participatory cultural events and place attachment A new path towards place branding? In W. Cudny (Ed.), Urban events, place branding and promotion: Place event marketing (pp. 63–85). Routledge.

- Cassinger, C., Gyimothy, S., & Lucarelli, A. (2021). 20 years of Nordic place branding research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1830434

- Cassinger, C., Lucarelli, A., & Gyimothy, S., (Eds.). (2019). The Nordic wave in place branding: Poetics, practices, politics. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Che-Ha, N., Nguyen, B., Yahya, W. K., Melewar, T., & Chen, Y. P. (2016). Country branding emerging from citizens’ emotions and the perceptions of competitive advantage: The case of Malaysia. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 22(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766715586454

- Chen, C.-F., & Tsai, D. C. (2007). How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tourism Management, 28(2007), 1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.07.007

- Cleave, E., & Arku, G. (2017). Putting a number on place: A systematic review of place branding influence. Journal of Place Management and Development, 10(5), 425–446. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-02-2017-0015

- Conradty, C., & Bogner, F. X. (2018). From STEM to STEAM: How to monitor creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 30(3), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2018.1488195

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design (4 print ed). Sage.

- Creswell, T. (2004). Place: A short introduction. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Cudny, W. (2019). Urban events, place branding and promotion: Place event marketing. Routledge.

- Dangi, T., & Jamal, T. (2016). An integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism”. Sustainability, 8(5), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8050475

- Dodds, R., Ali, A., & Galaski, K. (2018). Mobilizing knowledge: Determining key elements for success and pitfalls in developing community-based tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(13), 1547–1568. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1150257

- Dubois, A., & Gadde, L.-E. (2002). Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. Journal of Business Research, 55(7), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8

- Edensor, T. (2016). National identity, popular culture and everyday life. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Evans, G. (2001). Cultural planning: An urban renaissance? Routledge.

- Florek, M., Herezniak, M., & Augustyn, A. (2019). You can’t govern if you don’t measure: Experts’ insights into place branding assessment. Journal of Place Management and Development, 12(4), 545–565. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-10-2018-0074

- Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class: And how it's transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. Basic Books.

- Giannopoulos, A., Chios, A., & Skourtis, G. (2021). Destination branding and co-creation: A service ecosystem perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(1), 148–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2504

- Guo, W., Wu, D., Li, Y., Wang, F., Ye, Y., Lin, H., & Zhang, C. (2022). Suitability evaluation of popular science tourism sites in University Towns: Case study of Guangzhou University Town. Sustainability, 14(4), 2296. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042296

- Hall, C. M., Williams, A. M., & Lew, A. A. (2014). Tourism: Conceptualizations, disciplinarity, institutions, and issues conceptualizing tourism. In A. A. Lew, C. M. Hall, A. M. Williams, & S. Becken (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell companion to tourism (pp. 31–58). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hanna, S., & Rowley, J. (2008). An analysis of terminology use in place branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 4(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.6000084

- Hansen, T. B. (1995). Measuring the value of culture. The European Journal of Cultural Policy, 1(2), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286639509357988

- Johansson, R. (2007). On case study methodology. Open House International, 32(3), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/OHI-03-2007-B0006

- Kamata, H. (2022). Tourist destination residents’ attitudes towards tourism during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(1), 134–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1881452

- Kashyap, R., & Bojanic, D. (2000). A structural analysis of value, quality, and price perceptions of business and leisure travelers. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003900106

- Kavaratzis, M. (2005). Place branding: A review of trends and conceptual models. The Marketing Review, 5(4), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1362/146934705775186854

- Kavaratzis, M., Giovanardi, M., & Lichrou, M. (Eds.). (2017). Inclusive place branding: Critical perspectives on theory and practice. Routledge.

- Kemp, E., Williams, K. H., & Bordelon, B. M. (2012). The impact of marketing on internal stakeholders in destination branding: The case of a musical city. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 18(2), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766712443469

- Kerr, G. (2006). From destination brand to location brand. Journal of Brand Management, 13(4-5), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540271

- Kladou, S., & Mavragani, E. (2015). Assessing destination image: An online marketing approach and the case of TripAdvisor. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(2015), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.04.003

- Koster, E. H. (1999). In search of relevance: Science centers as innovators in the evolution of museums. Daedalus, 128, 277–296. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027575

- Kotler, P., Haider, D., & Rein, I. (1993). Marketing places: Attracting investment, industry, and tourism to cities, states, and nations. Free Press.

- Kunzmann, K. (2004). Culture, creativity and spatial planning. Town Planning Review, 75(4), 383–404. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.75.4.2

- Lefebvre, H., & Nicholson-Smith, D. (1991). The production of space. Blackwell Publishing.

- Lind, J., & Sandberg, H. (2021). Värdeanalys av Tom Tits Experiment - Sekundära ekonomiska värden och effekter från Tom Tits Experiment i Södertälje. Telge AB.

- Lindström, K. (2018). Destination development in the wake of popular culture tourism: Proposing a comprehensive analytic framework. In C. Lundberg, & V. Ziakas (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of popular culture and tourism (pp. 477–487). Routledge.

- Lund, N. F., Scarles, C., & Cohen, S. A. (2020). The brand value continuum: Countering Co-destruction of destination branding in social media through storytelling. Journal of Travel Research, 59(8), 1506–1521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519887234

- Lundberg, C., & Lindström, K. N. (2020). Sustainable management of popular culture tourism destinations: A critical evaluation of the twilight saga servicescapes. Sustainability, 12(12), 5177. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125177

- Mariutti, F. G., & Engracia Giraldi, J. d. M. (2021). Branding cities, regions and countries: The roadmap of place brand equity. RAUSP Management Journal, 56(2), 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAUSP-06-2020-0131

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2007). Sampling designs in qualitative research: Making the sampling process more public. The Qualitative Report, 12, 238–254. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2007.1636

- Parket, Holt N. (2011). Toward a definition of popular culture. History and Theory, 50(2), 147–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2303.2011.00574.x

- Piekkari, R., & Welch, C. (2018). The case study in management research: Beyond the positivist legacy of eisenhardt and yin? In The Sage handbook of qualitative business and management research methods (pp. 345–358). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526430212

- Resurs, A. B. (2020). TEM 2019 Ekonomiska och sysselsättningsmässiga effekter av turismen i Södertälje kommun inklusive år 2014–2018. Resurs AB.

- Ritchie, B. W., Carr, N., & Cooper, C. (2003). Managing educational tourism. Channel View Publications.

- Ritchie, J. R. B., & Ritchie, R. J. B. (1998). The branding of tourism destinations - past achievements & future challenges. Annual Congress of the International Association of Scientific Experts in Tourism, September 1, Morocco.

- Rosen, S. (1974). Hedonic prices and implicit markets: Product differentiation in pure competition. Journal of Political Economy, 82(1), 34–55. https://doi.org/10.1086/260169

- Sacco, P., Ferilli, G., & Pedrini, S. (2008). System-wide cultural districts: An introduction from the Italian viewpoint. In S. K. Kirchberg (Ed.), Sustainability: A new Frontier for the arts and cultures (pp. 400–460). VAS Verlag.

- Sacco, P. L. (2013). Kultur 3.0: Konst, delaktighet, utveckling. Nätverkstan.

- Sacco, P. L. (2016). How museums create value? In NEMO, Money matters: The economic value of museums. https://www.ecsite.eu/sites/default/files/nemoac2016.pdf

- Salmi, H. (2003). Science centres as learning laboratories. Experiences of Heureka, the Finnish Science Centre. International Journal of Technology Management, 25(5), 460–476. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2003.003113

- Södertälje kommun. (2015a). Södertälje varumärkesplattform, sammanfattning.

- Södertälje kommun. (2015b). Attitydundersökning Södertälje. Februari 2015. Södertälje: Destination Södertälje.

- Stoica, I., Kavaratzis, M., Schwabenland, C., & Haag, M. (2021). Place brand Co-creation through storytelling: Benefits, risks and preconditions. Tourism and Hospitality, 3, 15–30. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010002

- Strinati, D. (2004). An introduction to theories of popular culture. Routledge.

- Telge AB. (2020a). Affärsplan bolag Tom Tits Experiment AB 2019-2023. Telge AB.

- Telge AB. (2020b). Årsredovisning för Tom Tits Experiment AB Räkenskapsåret 2019-01-01–2019-12-31. Telge AB. https://www.telge.se/arsredovisningar

- Thorne, S. (2009). A tapestry of place: Whistler's cultural tourism development strategy. Consultant's report for the Resort Municipality of Whistler. Whistler, BC.

- Throsby, C. D. (2010). The economics of cultural policy. Cambridge University Press.

- Trueman, M., Klemm, M., & Giroud, A. (2004). Can a city communicate? Bradford as a corporate brand. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 9(4), 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280410564057

- Vecchi, A., Silva, E. S., & Jimenez Angel, L. M. (2021). Nation branding, cultural identity and political polarization – an exploratory framework. International Marketing Review, 38(1), 70–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-01-2019-0049

- Vuignier, R. (2017). Place branding & place marketing 1976-2016: A multidisciplinary literature review. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 14(4), 447–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-017-0181-3

- Yakman, G., & Lee, H. (2012). Exploring the exemplary STEAM education in the U.S. As a practical educational framework for Korea. Journal of The Korean Association for Science Education, 32(6), 1072–1086. https://doi.org/10.14697/jkase.2012.32.6.1072

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.

- Zenker, S., & Martin, N. (2011). Measuring success in place marketing and branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 7(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2011.5

- Zenker, S., Petersen, S., & Aholt, A. (2013). The citizen satisfaction index (CSI): evidence for a four basic factor model in a German sample. Cities, 31, 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.02.006