ABSTRACT

People pursue leisure activities like running because it makes them feel good and Stebbins (1992) suggests that serious leisure predicts subjective well-being (SWB). However, it is unclear whether serious leisure and/or its behavioural consequences such as increased consumption, event participation or training, explain varying levels of SWB. Some of these behavioural consequences have adverse environmental impacts, and a trade-off exists between negative environmental impacts and increased levels of SWB. This study surveyed 933 runners about their level of serious leisure, consumption patterns, training, event participation, and SWB. CFA and SEM are used to test the direct effects of serious leisure and the role of selected mediators to understand their effects on SWB. The study concludes that serious leisure itself has no significant direct effect on SWB. However, athletes’ engagement in training has direct positive effects on SWB. Furthermore, serious leisure, training and event participation increase other types of consumption, such as shoes, electronic equipment, cloths, etc. which have, however, no significant effect on SWB. These results advise organisers of leisure activities, such as event organisers, how to develop sustainable, yet valuable event experiences.

Introduction

People spend considerable amounts of time and money on leisure activities within the context of participant sport events such as triathlons, marathons or cycling events (Lundberg & Andersson, Citation2022). Research suggests that people pursue these leisure interests for reasons of happiness and well-being (Newman et al., Citation2014). Subjective well-being (SWB) describes the state of happiness as the subjective assessment of an individual’s overall level of well-being (Diener, Citation1984). Based on individuals’ subjectivity, SWB is a reflection of core cognitive, affective and emotional characteristics, of people’s lives (Diener et al., Citation2002).

Based on early work by Stebbins (Citation1982; Citation1992), serious leisure has been established as one predictor of SWB. Serious leisure is the “systematic pursuit of an amateur, hobbyist or volunteer activity sufficiently substantial and interesting for participants to find a career during which they acquire and express a combination of special skills and knowledge” (Stebbins, Citation1992, p. 3). These characteristics set serious leisure apart from casual leisure and describe how individuals pursue their leisure with increasing intensity. People with specific degrees of seriousness exhibit higher levels of well-being due to perceived social, psychological, and physical benefits. Serious leisure is closely related and correlated with involvement (Havitz & Dimanche, Citation1997) which has also shown to be of importance for SWB.

Serious leisure is related to training necessary skills and knowledge. Research shows that sport participation can promote SWB among children and adults (Coakley & Pike, Citation2009; Gould & Carson, Citation2008). Wheatley and Bickerton (Citation2019) concur in stating that frequency of training and engagement generate positive effects of sports on well-being. Since the level of activity and frequency vary, SWB varies among individuals and groups. People who are more engaged, and who invest more time and effort in training may eventually perceive higher levels of well-being. Similarly, serious athletes also travel to and attend larger and more significant events to a larger extent, which contributes to a meaningful life and SWB. The event career ladder trajectory describes how leisure motives, event participation, and travelling to events develop with serious leisure (Andersson et al., Citation2019). Induced by its association with frequency and intensity in pursuing leisure activities; serious leisure also affects consumption behaviours.

Serious leisure also indirectly influences SWB through mediated behavioural traits such as consumption, training, and event participation. Several of these behavioural traits have adverse environmental consequences. Event participation often increases e.g. travelling which has adverse climate impacts. Similarly, consumption of goods and services contributes with negative environmental footprints. In the light of the trade-off between the negative impacts on the environment and positive effects for SWB, a better understanding of the behaviour, driven by serious leisure, is needed.

This study aims to test serious leisure and its behavioural consequences as predictors of SWB in a participant sport event context. More specifically the study analyses if sport-related consumption (e.g. training gear), the volume of event participation, and training mediate the effect from serious leisure on SWB. Previous research has predominantly tested direct links between serious leisure and SWB, consumption or participation. This study provides a more comprehensive picture by combining the concepts in one research model. The results of this study therefore lay the ground for organisers of leisure activities, such as participant sports events, to develop valuable event experiences and thus SWB, while considering the effect of increasing consumption as a negative environmental effect. The article also contributes theoretically to a more detailed understanding of the linkages between serious leisure and SWB in the contexts of events and sport tourism.

Literature and hypotheses

People pursue leisure interests because it makes them happy (Newman et al., Citation2014). Subjective well-being (SWB) is a concept describing the state of happiness in terms of each individuals’ subjective assessment of his or her level of well-being (Diener, Citation1984).

The continuous engagement in leisure activities implies the acquisition and expression of special skills and knowledge (Stebbins, Citation1992, p. 3). Serious leisure describes this process, reflecting a career development within leisure activities. It has been noted that people with higher levels of seriousness exhibit higher levels of well-being due to perceived social, psychological, and physical benefits. Serious leisure is related to training necessary skills and knowledge. People who are more engaged, and who invest more time and effort in training may eventually perceive higher levels of well-being. Similarly, serious athletes also travel to and attend larger and more significant events to a larger extent, which contributes to a meaningful life and SWB. Induced by its association with frequency and intensity in pursuing leisure activities; serious leisure also affects consumption behaviours.

In summary, previous research provides evidence that serious leisure has a positive effect on SWB. Furthermore, serious leisure is proposed to indirectly influence SWB through mediated behavioural traits such as consumption, training, and event participation. In the following sections, these conceptual linkages are reviewed, and 14 hypotheses are proposed.

Serious leisure and SWB

SWB has received increasing attention. It is positively associated with aspects such as income (Diener & Biswas-Diener, Citation2002), health (Diener, Citation1984; Koivumaa-Honkanen et al., Citation2004), social relations (Lyubomirsky et al., Citation2005) and productivity at work (Boehm & Lyubomirsky, Citation2008). SWB is a reasonably stable state of mind, mainly determined by genetic predispositions (Filep & Deery, Citation2010). Approximately half of the variation in SWB is accounted for by genetic and early childhood influences which constitute a SWB set-point. Fluctuations from the set-point are normally minor and the level of well-being tends to return to the set-point in the long run (Filep & Deery, Citation2010). Besides the genetic factors, circumstantial factors, such as place of living (Diener et al., Citation1999), religion (Diener et al., Citation1999), social relationships (Diener & Seligman, Citation2002), age (Heo et al., Citation2010) and income or wealth can, to some extent influence SWB (Diener et al., Citation2013; Filep & Deery, Citation2010). Approximately ten percent of the variation in SWB is predicted by circumstantial factors. The remaining 40 percent of the variation can be influenced by intentional activity factors which relate to individual behaviours that satisfy needs.

Leisure activities are intentional activity factors and Stebbins (Citation1992) reported positive relationships between seriousness in leisure and SWB. Serious leisure describes the level of interest in an activity and suggests that six qualities exist (i.e. dimensions); perseverance, having a leisure career, significant personal effort, durable benefits, unique ethos and strong expression of oneself and identity through an activity (Stebbins, Citation1992). The first quality presumes that participation in serious leisure activities requires perseverance to conquer adverse situations such as lack of time (Stebbins, Citation1992). The second quality suggests that the pursuit of leisure activities implies turning points, and phases of accomplishment or involvement that might lead to the development of a leisure career centred around their chosen activities (Stebbins, Citation1992). The third quality relates to efforts made to acquire knowledge, skills, and experience for this activity. Furthermore, Stebbins (Citation1992) asserts that serious leisure participation is driven by the desire for durable benefits such as self-actualization, self-enrichment, self-expression, and self-gratification. Participants’ unique ethos, which is associated with their so-called social world (Unruh, Citation1980), refers to the meaning of being part of a peer group whose attitudes, practices, values, beliefs, and goals are shared by other (serious) participants (Stebbins, Citation1992). Finally, a strong sense of identification with an activity is a characteristic of serious leisure participants (Stebbins, Citation1992).

Empirical applications within numerous contexts such as kayaking (Bartram, Citation2001), cycling (O’Connor & Brown, Citation2010), taekwondo (Kim et al., Citation2011), surfing (Barbieri & Sotomayor, Citation2013) and running (Ronkainen et al., Citation2017) support the relevance of serious leisure for SWB. Within a volunteer context, Chen (Citation2014) reveals that high serious leisure qualities cause higher levels of SWB due to positive effects on physical, psychological, or social well-being. In the context of surfing Barbieri and Sotomayor (Citation2013) studied the role of serious leisure when mastering waves and climbing the “surfing ladder”. The authors stress the importance of skills and technical knowledge which are related to perseverance, effort and career qualities of serious leisure (Barbieri & Sotomayor, Citation2013). Kane and Zink (Citation2004) found that kayakers’ identity expressions, as well as their shared ethos, affect their feelings of accomplishments and stress. Moreover, the level of seriousness among people engaged in Taekwondo activities has been found to increase life satisfaction and health perception (Kim et al., Citation2011). The results of Kim et al. (Citation2011) confirm the relationship between serious leisure, personal growth, and happiness. They argue that serious participants experienced personal growth when handling difficulties, and putting effort into relationships (Kim et al., Citation2011). Heo et al. (Citation2012) found that serious leisure was negatively related to depression levels. These empirical applications support the relationship between serious leisure and happiness. We therefore argue that the level of serious leisure affects SWB and hypothesize that:

H1: Serious leisure is positively related to SWB.

Serious leisure and training

Serious leisure entails significant efforts in terms of knowledge, skills, or training (Stebbins, Citation1992). Serious leisure qualities of participants in sports positively influence the frequency of training and training intensity (Shipway & Jones, Citation2008; Tian et al., Citation2020). Marathon runners, for example, must overcome more physical and mental challenges and spend considerable time and energy on training to endure long-distance races (Qiu et al., Citation2020). Lamont et al. (Citation2019) found that increasing levels of seriousness among participants in triathlon sports spend more time on training than those with lower levels. Barbieri and Sotomayor (Citation2013) studied serious surfers and report a positive relationship between serious leisure qualities (effort, career, and identity) and frequency of weekly training in surfing. The results suggest that surfers who are serious about their activity and who are willing to improve their surfing career and identified with it, practice more. These findings are in line with Brown (Citation2007) who studied shag dancing, illustrating that serious shag dancers are putting considerably more effort into training compared to less serious dancers. First, based on this research, we hypothesize that:

H2: serious leisure is positively related to training alone.

H3: serious leisure is positively related to training in social contexts.

Serious leisure, event participation and consumption

Recent studies demonstrate that serious athletes differ from casual athletes in their event participation behaviour. Serious triathletes are e.g. more likely to attend long-distance triathlon events (Ma et al., Citation2022). These results support previous research reporting positive relationships between the level of seriousness and sport event participation (Getz & Andersson, Citation2010; Getz & McConnell, Citation2011). Serious leisure participants are more efficient in overcoming obstacles, such as expenses, to achieve the perceived benefits of participating in events (Ma et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, serious leisure positively affects event participation due to participants’ willingness to engage socially with others during events (Armbrecht & Andersson, Citation2020). Similar effects have been observed for leisure involvement (Cheng & Tsaur, Citation2012), which is highly correlated with serious leisure. The concept of the event-tourist career trajectory (Getz & Andersson, Citation2010) illustrates how consumers invest more time and money in their interests and in travelling as a result of increasing levels of involvement. For instance, serious surfers are willing to consume more surfing events now and in the future than casual surfers (Barbieri & Sotomayor, Citation2013). Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H4: serious leisure has a positive effect on event participation.

H5: serious leisure has a positive effect on consumption of products

H6: Training alone has a positive effect on consumption of products

H7: Training in social contexts has a positive effect on consumption of products

H8 training alone is positively related to event participation.

H9 training in social contexts is positively related to event participation.

H10: Event participation has a positive effect on consumption of products.

Training, consumption, event participation and SWB

Kuykendall et al. (Citation2015) report positive relationships between leisure engagement, the amount of time spent on leisure activities and SWB. Wheatley and Bickerton (Citation2019) found that frequency and engagement generate positive effects on well-being. Similar results were found for children where sport participation can promote SWB (Gould & Carson, Citation2008). People derive (hedonic) happiness from the consumption of products by means of “positive affect” (Diener, Citation1984; Lyubomirsky, Citation2001). Research results substantiate the conception that purchases and pleasurable consumption explain happiness (Nicolao et al., Citation2009; Van Boven, Citation2005). While the intensity of positive affect is important, frequent positive affect seems to be more central for hedonic happiness and thus SWB (Diener et al., Citation1999). From the perspective self-actualization and fulfilment, happiness will mainly be derived when engaging in meaningful activities leading to personal growth, and self-realization. Leisure participation, event participation and training have been found to positively affect happiness because they are perceived to contribute to the achievement of goals and a meaningful life (Bailey & Fernando, Citation2012; Brown et al., Citation1991; DeLeire & Kalil, Citation2010).

Thus, the engagement and training in leisure activities and the participation in events increase SWB mainly for reasons of goal achievement, meaningfulness, and self-actualization. Consumption of goods and services related to leisure activities contributes to SWB for hedonic reasons (pleasure) and supports people in achieving goals, and self-actualization. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H11: Training alone is positively associated with SWB.

H12: Training in social contexts is positively associated with SWB.

H13: Event participation is positively associated with SWB.

H14: Consumption of leisure related products is positively associated with SWB.

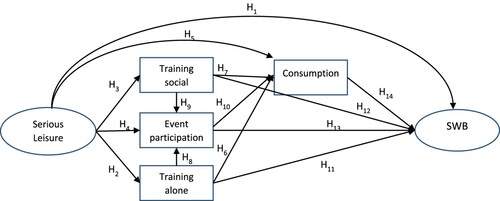

In serious leisure is modelled as the exogenous construct and conceptualised as the main predictor for training, event participation, consumption and SWB. Training, event participation and consumption are modelled to mediate the effect of serious leisure on SWB.

Method

Empirical context

This study surveyed participants at GöteborgsVarvet in 2022, an annually recurring half marathon in the city of Gothenburg, Sweden. The half marathon is one of the largest of its kind. Between 30.000 and 60.000 runners participate in the event every year. In 2022, the number of participants was down to 23.000. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has had negative impacts on event attendance.

Sampling procedure and sample profile

From the sampling frame (e-mail addresses to participants who finalized the race in 2022) a random sample of 3000 participants was drawn. An e-mail was sent out to each respondent three days after the race with an invitation to participate in a web-based survey. Six days after the first invitation a reminder was sent out. Fourteen days after the first invitation was sent out, the survey was closed, and the data was downloaded for analysis in IBM SPSS Statistics 29 and StataSE 17.

A total of 1.000 participants answered the survey, equivalent to a response rate of 33.3%. During the data cleaning procedure, another 77 observations were removed due to high levels of missing data. Thus, 923 respondents were kept.

Sample profile

presents the descriptive statistics of the demographic profile of respondents. Most participants in the running event were male (59.6%). Most respondents have a university degree (62.4%) and the second most frequent educational level was completion of secondary education (31.1%). More than two-thirds of the participants had a partner, either with or without children at home. The demographic statistics show reasonable diversity reducing the negative effects of sample selection biases (Prayag et al., Citation2013).

Table 1. Results of demographic variables.

Survey instrument

Scales to measure serious leisure are based on the dimensions suggested by Stebbins (Citation1992) and applied by Tsaur and Liang (Citation2008). The scale consists of 16 items representing the six dimensions perseverance, having careers in their activity, significant personal effort, durable individual benefits, unique ethos, and identification with the activity. The wording of the items was adapted to the specific context of this study. The items are presented in .

Table 2. CFA with Standardized Factor Loadings (SL) and Cronbach’s Alpha (Alpha).

SWB was measured through three items. The first item was worded as “All things considered, how satisfied are you with life as a whole nowadays?” The respondents answered the question on a scale ranging from 0 (unhappy) to 10 (happy) (cf. European Social Survey, 2019). Literature acknowledges that single-item measures may have satisfactory reliability and validity (Diener, Citation2009), but they are criticized because the variance cannot be averaged out (Diener, Citation2009) prohibiting tests of reliability and internal consistency. Therefore two items from the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) as suggested by Diener et al. (Citation1985) were added to the survey. These were “In most ways my life is close to my ideal” and “I am satisfied with my life”, to which the respondent reacted on a five-pointLikert-type scale.

To measure training respondents were asked to indicate (on a scale from 0 to 20) how many hours per week they train – either individually, i.e. alone, or in a group, i.e. in a social context. Event participation was measured by means of three questions. Respondents were asked how many (1) local events, (2) national events and (3) international events they had participated in, or were planning to participate in, during 2022. Consumption was measured by asking each respondent to indicate how much money they spent on running and what products related to running were consumed during the last twelve months, including for example training shoes, training clothes, training trips, and electronic equipment.

Analytical procedure

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test the model fit and construct validity of the measurement model and structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to test the casual relationships in the conceptual model (Hair et al., Citation2010). The following statistics were used to test model fit of both the measurement and structural model: chi-square statistic (χ2), normed chi-square (χ2/df), Root Mean Square of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). Construct validity was evaluated by means of establishing convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was assessed through the significance, size and direction of factor loadings, the average variance extracted (AVE) and reliability of each factor using Cronbach's alpha. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparison of AVE and the variance extracted by other factors in order to examine whether the constructs measured distinct phenomena (Kline, Citation2005).

Analysis

When asked about their general satisfaction with life on a scale from 0 to 10, the average level of SWB among participants is 7.89 (with standard deviation of 1.59 and a variance of 2.55). In comparison, the average among Swedes during the three-year period 2019–2021 was 7,38 (Helliwell et al., Citation2022). A one-sample t-test reveals that the differences are significant [t(460) = 9.78, p > 0.001]. The results hence suggest that athletes who participated in the event were significantly happier than the average Swede.

CFA

CFA was performed for the six dimensions of serious leisure. The results of the Chi-square test, which is sensitive to sample size (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation2012), indicates no significant differences between the observed and estimated covariance matrix of the measurement model; Chi-square 405 (df = 89; p > 0.001). The ratio of Chi-square to degrees of freedom, more commonly used as an indicator for model fit, is however below the threshold of 5 (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation2012). Acceptable fit of the measurement model is further suggested by a good comparative fit index (CFI = 0.952), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI = 0.935) and an acceptable root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.063).

All items have significant factor loadings and most exceed the threshold of 0.7. The factor loadings display a positive direction (as expected) and AVE values are greater than .50, further supporting convergent validity (Hair et al., Citation2012). Reliability is supported with Cronbach’s alphas above 0,7 for all constructs.

Discriminant validity of the measurement model is tested by comparing the AVE of each construct with the square of its correlation to other constructs. shows the AVE in the diagonal cells (bold) which are compared to the off-diagonal cells. All but two cases display discriminant validity. The two cases of weak discriminant validity are: Have careers and significant personal effort. For both constructs, the variance extracted by other constructs exceeds their AVE. Despite two weaknesses in discriminant validity, the measurement model is suggested to exhibit satisfactory fit and construct validity suitable for further analysis (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation2012).

Table 3. Assessment of convergent and discriminant validity.

SEM

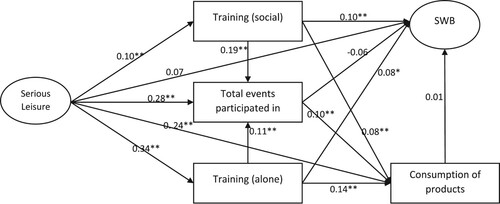

The SEM describes the effect of serious leisure on SWB and transitional mediators (training, event participation and consumption). The results are shown in including beta coefficients. Like the measurement model, the model fit of the structural model is satisfactory. The fit statistics for the structural model are as follows: χ2 = 767; df = 214; CFI = 0.934; RMSEA = 0.054; TLI = 0.922. The relatively high Chi-square statistic is mainly explained by its inflation through sample size (Hair et al., Citation2010).

Figure 2. Structural model. NOTE: * coefficients are statistically significant, p < .05, ** coefficients are statistically significant, p < .01.

It is noteworthy that the effects of the independent and mediating variables only reflect differences among participants of this event. It means that effects can only indicate differences between runners at GöteborgsVarvet, but not between non-participants and participants.

Serious Leisure is modelled as a second-order construct in the structural model with the following standardized regression weights for the respective dimensions: Unique Ethos (0.45), Perseverance (0.65), Durable individual benefits (0.65), Have careers (0.84), Significant personal efforts (0.9), and identification with the activity (0.76).

SWB is modelled as a latent construct measured by three items. The standardized factor loadings of the three items range from 0.84 to 0.88, supporting convergent validity. Cronbach’s Alpha for the items measuring SWB is 0.816 supporting construct validity.

complements and indicates the significant paths. Serious Leisurehas a significant effect on training alone and training in social contexts, event participation and consumption. The effect on SWB is not significant. All effects from training alone and training in social contexts are significant. Furthermore, event participation has a significant effect on consumption. Neither total event participation nor consumption of products has a significant effect on SWB.

Table 4. Path estimates of structural model and summary of hypotheses testing.

Noteworthy is that an inspection of the standardized covariance residuals indicates high values (above │2,5│) between items measuring unique ethos and training in social contexts, and perseverance and training alone. The interpretation is that some of the variance between these variables is not accounted for. This interpretation is supported by modification indices ranging from 18–34 for items measuring unique ethos and training in social contexts, and modification indices ranging from 4 to 12 for items measuring perseverance and training alone.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, an established measure of serious leisure was tested in confirmatory factor analysis and then used, together with the behavioural consequences of serious leisure (training, event participation, and consumption), to predict SWB in a structural model. In the SEM model, serious leisure is conceptualized as a second order construct and constitutes the main predictor for both the mediating variables training, event participation, consumption (H2, H3, H4, and H5) and the latent dependent construct SWB. In the measurement model validation and the structural model, the constructs demonstrate acceptable model fit and construct validity. The study shows that serious leisure has no direct significant effect on SWB. However, athletes’ active engagement and participation in training has positive effects on SWB (H11 and H12). At the same time, serious leisure, training, and event participation increase other types of consumption, such as shoes, electronic equipment, clothes, training camp, etc. (H5, H6, H7, and H10). This type of consumption has no significant effect on SWB (H14).

These conclusions are discussed more in detail below in terms of theoretical and managerial implications. Directions for future research are also proposed.

Theoretical implications

First, event participants are happier than the average Swedish citizen. The initial t-test of difference in SWB suggests that participants at GöteborgsVarvet reported significantly higher levels of SWB (7.89) on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, compared to the average level of happiness in Sweden (7.38). While the differences in the level of SWB cannot be causally linked to participation in this event, the results support previous research demonstrating that event participation is related to increased SWB (Lundberg & Andersson, Citation2022). Previous research has pointed out that substantial parts of SWB in society are explained by set point factors (∼50%) and circumstantial factors (∼10%) which, are difficult to influence (Lyubomirsky et al., Citation2005). Approximately 40% of the well-being can be influenced by individuals through personal choices. In total, the structural model indicates that approximately 2% of the variance in SWB is explained by the direct and mediated effects of the indicators included in the model. In a social science context, this may be regarded low, but applications of SWB in similar contexts report comparable results (Lundberg & Andersson, Citation2022).

A notable contribution of the tested model is that it challenges the notion that the level of serious leisure has a direct effect on SWB. The study highlights the importance of including behavioral consequences of serious leisure in the model. In this study of runners, serious leisure has, as shown in , significant indirect effects on SWB, both through training alone and training in social groups. Thus, serious runners mainly achieve happiness through higher levels of physical activities such as training. This contradicts, to some extent, previous research in the domain of sport and recreational leisure pursuits which highlight a direct effect of serious leisure on SWB. However, Ronkainen et al. (Citation2017), who studied runners, did a qualitative study and they did not account for e.g. the mediating effect of training. It also differs from the results of Kim et al. (Citation2011) studying Taekwondo practitioners and found a direct effect, albeit using a comparison of means statistics (MANOVA) and not including any mediating or moderating variables. Similarly, Chen (Citation2014) also found a direct effect but in the context of older adult volunteers and not including any variables related to behavioral consequences of the serious leisure pursuit. This indicates that the larger context of, in this case, a serious runner is vital to include, notably behavioral consequences of serious leisure, such as for example training (which had a direct effect on SWB).

Regarding training, serious leisure has a direct effect on both training alone and in social contexts. This means that even if serious amateur athletes train more alone, they are also more inclined to train together with others, which emphasize how training is important for social identity (Lamont et al., Citation2014) and being part of a social world (Unruh, Citation1980) dedicated to running, but also effort and the career of people that pursue a serious leisure (Barbieri & Sotomayor, Citation2013)

A noteworthy observation is the relatively low factor loading between items measuring unique ethos and training in social contexts, and perseverance and training alone. To persevere, i.e. the willingness to put in an effort, or to acquire the unique ethos of the leisure pursuit should, normally, be stronger determinants of training according to theory (Stebbins, Citation1992) and previous empirical studies (Barbieri & Sotomayor, Citation2013). Interestingly, however, the analysis of standardized residual covariances and modification indices suggests that considerable direct relationships between unique ethos and training in social contexts and perseverance and training alone exists. This result may have multiple reasons. One explanation may be that the items measuring the dimension unique ethos, at least partly, reflect social dimensions.

The amount of money, participants spend on running products is significantly affected by all predictors: serious leisure, training alone and in social contexts as well as event participation. Thus, higher involvement in sports fuels active sport tourism growth in line with the results of Shipway and Jones (Citation2008) and positive economic impacts for the sport retail sector. Consumption does however not have a significant direct effect on SWB. It means, that higher spendings on e.g. running gear and equipment to perform the event do not increase SWB. But caution should be warranted since the consumption may have occurred long before the event took place. Since hedonic happiness is often a short-lived feeling and related to the pursuit of pleasure or material gain (Desmeules, Citation2002; Nicolao et al., Citation2009), the potential increase in SWB, caused by consumption, is not captured in this study. Happiness has already returned to its set point at the time of the data collection. Meanwhile, the happiness derived from training may prevail longer and is thus easier to capture in the present study because happiness derived from self-actualization and goal achievement gives longer lasting effects, such as a sense of purpose and living a life in line with one’s values (Bailey & Fernando, Citation2012).

Managerial implications

Seeing that serious leisure influences SWB through training, event managers and policy makers could provide the opportunity for training and similar activities where runners can indulge in their leisure interest. This is likely to be an effective tool to influence runners’ and event participants’ levels of SWB. But it should also be noted that previous research has theorized on a potential recursive effect of event participation on serious leisure (Armbrecht et al., Citation2019). For event managers, it is therefore necessary to understand and influence components of serious leisure and facilitate training for amateur athletes. Becoming more serious and training more would lead them to participate in more events, and if this is induced by the event brand, the event could expect more participants. This is in line with the conceptualization of the event-travel career trajectory as a dynamic reinforcing system (Andersson et al., Citation2019).

The increase in active sport tourism induced by serious runners’ participation in events is complemented with higher expenditure in the sport retail sector (running shoes, electronic devices, etc.). Managers in this sector should find social worlds where serious athletes fulfil their serious leisure pursuit to market their brand. This includes both their day-to-day training contexts as well as the events where they participate.

From a destination perspective, the results contribute to a better understanding of how events function as facilitators for SWB while pointing out areas where events and event participation create environmental challenges. Destination managers are advised to carefully consider different types of leisure events as well as their micro and macro location in order to minimize consumption and transportation and their adverse effects for the environment.

Limitations and future research

Even if the model tested in this study adds to our knowledge about the linkages between serious leisure and SWB, there are possibilities to further explore this domain. One recommendation for future studies is to try to improve the level of variance explained by adding relevant variables from the leisure context to the model, such as need fulfilment and work life balance (Gröpel & Kuhl, Citation2009). Another approach would be to include a more detailed measurement scale of SWB, as proposed by Diener et al. (Citation1999), to understand which components of SWB that are influenced by serious leisure pursuits. It is highly probable that some components of SWB are more related to activities outside of the leisure domain, such as the family or work domain (cf. Diener et al., Citation1999).

A dimension which is only implicitly embedded in this study is the importance of participating in the social world of runners, which in this study relates to respondents’ participation in training (in groups) and events. The social world is important for people with leisure interests to cultivate skills, knowledge, experiences, and boost your self-identity as a runner in meetings with other runners (Green & Jones, Citation2005). Further studies should focus more specifically on the role of these interactive contexts as facilitators of both the serious leisure career and perceived well-being. This is evident since the results of this study show that training with others is an important link between serious leisure and SWB. Due to the lack of in-depth knowledge of the role of social worlds in this context, ethnographical methods are recommended as a first step (Andersson et al., Citation2019).

Finally, an increased consumption of training gear, training trips, and event experiences related to leisure activities induce climate impacts. The sport event industry has previously been highlighted for its negative climate impacts related, predominantly, to travelling, sport-related products, and arena constructions (Sotiriadou & Hill, Citation2015). The balance between positive health benefits and increased well-being of physical leisure activities, and on the other hand possible negative climate impacts needs further attention. The results of the present study could act as a segue into such inquiries in event and sport tourism studies since it shows that serious leisure pursuits, training, and event experiences push consumption, which does not contribute to higher levels of SWB in the long run.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersson, T. D., Armbrecht, J., & Lundberg, E. (2019). Participant events and the active event consumer. In J. Armbrecht, T. D. Andersson, & E. Lundberg (Eds.), A research agenda for event management (pp. 107–124). Edward Elgar.

- Armbrecht, J., & Andersson, T. D. (2020). The event experience, hedonic and eudaimonic satisfaction and subjective well-being among sport event participants. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 12(3), 457–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2019.1695346

- Armbrecht, J., Lundberg, E., & Andersson, T. D. (2019). A research agenda for event management. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x

- Bailey, A. W., & Fernando, I. K. (2012). Routine and project-based leisure, happiness, and meaning in life. Journal of Leisure Research, 44(2), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2012.11950259

- Barbieri, C., & Sotomayor, S. (2013). Surf travel behavior and destination preferences: An application of the Serious Leisure Inventory and Measure. Tourism Management, 35, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.06.005

- Bartram, S. A. (2001). Serious leisure careers among whitewater kayakers: A feminist perspective. World Leisure Journal, 43(2), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/04419057.2001.9674225

- Boehm, J. K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Does happiness promote career success? Journal of Career Assessment, 16(1), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707308140

- Bridel, W. F. (2010). Finish … whatever it takes” Exploring pain and pleasure in the ironman Triathlon: A socio-cultural analysis.

- Brown, B., Frankel, B., & Fennell, M. (1991). Happiness through leisure: The impact of type of leisure activity, age, gender and leisure satisfaction on psychological well-being. Journal of applied recreation research, 16(4), 368–392.

- Brown, C. A. (2007). The carolina shaggers: Dance as serious leisure. Journal of Leisure Research, 39(4), 623–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2007.11950125

- Chen, K.-Y. (2014). The relationship between serious leisure characteristics and subjective well-being of older adult volunteers: The moderating effect of spousal support. Social Indicators Research, 119(1), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0496-3

- Cheng, T.-M., & Tsaur, S.-H. J. L. S. (2012). The relationship between serious leisure characteristics and recreation involvement: A case study of Taiwan’s surfing activities. Leisure Studies, 31(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2011.568066

- Coakley, J. J., & Pike, E. (2009). Sports in society: Issues and controversies. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- DeLeire, T., & Kalil, A. (2010). Does consumption buy happiness? Evidence from the United States. International Review of Economics, 57(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-010-0093-6

- Desmeules, R. (2002). The impact of variety on consumer happiness: Marketing and the tyranny of freedom. Academy of marketing science review, 12(1), 1–18.

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

- Diener, E. (2009). Subjective well-being. In E. Diener (Ed.), The science of well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener (pp. 11–58). Springer Netherlands.

- Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 57(2), 119–169. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014411319119

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. J. J. o. p. a. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale, 49(1), 71–75.

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2002). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. Handbook of positive psychology, 2, 63–73.

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00415

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

- Diener, E., Tay, L., & Oishi, S. (2013). Rising income and the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030487

- Filep, S., & Deery, M. (2010). Towards a picture of tourists’ happiness. Tourism Analysis, 15(4), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354210X12864727453061

- Getz, D., & Andersson, T. D. (2010). The event-tourist career trajectory: A study of high-involvement amateur distance runners. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 10(4), 468–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2010.524981

- Getz, D., & McConnell, A. (2011). Serious sport tourism and event travel careers. Journal of Sport Management, 25(4), 326–338. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.25.4.326

- Gould, D., & Carson, S. (2008). Life skills development through sport: Current status and future directions. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(1), 58–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/17509840701834573

- Green, B. C., & Jones, I. (2005). Serious leisure, social identity and sport tourism. Sport in Society, 8(2), 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/174304305001102010

- Gröpel, P., & Kuhl, J. (2009). Work–life balance and subjective well-being: The mediating role of need fulfilment. British Journal of Psychology, 100(2), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712608X337797

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (seventh edition ed.). Pearson Education.

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

- Havitz, M. E., & Dimanche, F. (1997). Leisure involvement revisited: Conceptual conundrums and measurement advances. Journal of Leisure Research, 29(3), 245–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1997.11949796

- Helliwell, J., Layard, R., Sachs, J. D., Neve, J.-E. D., Aknin, L. B., & Wang, S. (2022). World happiness report 2022. Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

- Heo, J., Lee, I. H., Kim, J., & Stebbins, R. A. (2012). Understanding the relationships among central characteristics of serious leisure: An empirical study of older adults in competitive sports. Journal of Leisure Research, 44(4), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2012.11950273

- Heo, J., Lee, Y., McCormick, B. P., & Pedersen, P. M. (2010). Daily experience of serious leisure, flow and subjective well-being of older adults. Leisure Studies, 29(2), 207–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360903434092

- Kane, M. J., & Zink, R. (2004). Package adventure tours: Markers in serious leisure careers. Leisure Studies, 23(4), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/0261436042000231655

- Kim, J., Dattilo, J., & Heo, J. (2011). Taekwondo participation as serious leisure for life satisfaction and health. Journal of Leisure Research, 43(4), 545–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2011.11950249

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

- Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., Kaprio, J., Honkanen, R., Viinamäki, H., & Koskenvuo, M. (2004). Life satisfaction and depression in a 15-year follow-up of healthy adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(12), 994–999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0833-6

- Kuykendall, L., Tay, L., & Ng, V. (2015). Leisure engagement and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141(2), 364–403. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038508

- Lamont, M., Kennelly, M., & Moyle, B. (2014). Costs and perseverance in serious leisure careers. Leisure Sciences, 36(2), 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2013.857623

- Lamont, M., Kennelly, M., & Moyle, B. (2019). Perspectives of endurance athletes’ spouses: A paradox of serious leisure. Leisure Sciences, 41(6), 477–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2017.1384943

- Lundberg, E., & Andersson, T. (2022). Subjective well-being (SWB) of sport event participants: Causes and effects. Event Management, 26(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599521X16192004803601

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2001). Why are some people happier than others? The role of cognitive and motivational processes in well-being. American Psychologist, 56(3), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.239

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

- Ma, S.-M., Ma, S.-C., & Chen, S.-F. (2022). The influence of triathletes’ serious leisure traits on sport constraints, involvement, and participation. Leisure Studies, 41(1), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2021.1948592

- Newman, D. B., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 555–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9435-x

- Nicolao, L., Irwin, J. R., & Goodman, J. K. (2009). Happiness for sale: Do experiential purchases make consumers happier than material purchases? Journal of Consumer Research, 36(2), 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1086/597049

- O’Connor, J. P., & Brown, T. D. (2010). Riding with the sharks: Serious leisure cyclist's perceptions of sharing the road with motorists. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 13(1), 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2008.11.003

- Prayag, G., Hosany, S., Nunkoo, R., & Alders, T. (2013). London residents’ support for the 2012 Olympic Games: The mediating effect of overall attitude. Tourism Management, 36, 629–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.08.003

- Qiu, Y., Tian, H., Zhou, W., Lin, Y., & Gao, J. (2020). ‘Why do people commit to long distance running’: Serious leisure qualities and leisure motivation of marathon runners. Sport in Society, 23(7), 1256–1272. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1720655

- Rauter, S. (2014). Mass sports events as a way of life (differences between the participants in a cycling and a running event). Kinesiologia Slovenica, 20, 1.

- Robinson, R., Patterson, I., & Axelsen, M. (2014). The “loneliness of the long-distance runner” No more. Journal of Leisure Research, 46(4), 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2014.11950333

- Ronkainen, N. J., Harrison, M., Shuman, A., & Ryba, T. V. (2017). “China, why not?”: Serious leisure and transmigrant runners’. stories from Beijing. Leisure Studies, 36(3), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2016.1141977

- Shipway, R., & Jones, I. (2008). The great suburban everest: An ‘insiders’ perspective on experiences at the 2007 Flora London marathon. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 13(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775080801972213

- Sotiriadou, P., & Hill, B. (2015). Raising environmental responsibility and sustainability for sport events: A systematic review. International Journal of Event Management Research, 10(1), 1–11.

- Stebbins, R. A. (1982). Serious leisure: A conceptual statement. Pacific Sociological Review, 25(2), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388726

- Stebbins, R. A. (1992). Amateurs, professionals, and serious leisure. McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP.

- Tian, H. B., Qiu, Y. J., Lin, Y. Q., Zhou, W. T., & Fan, C. Y. (2020). The role of leisure satisfaction in serious leisure and subjective well-being: Evidence from Chinese marathon runners. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.581908

- Tsaur, S.-H., & Liang, Y.-W. (2008). Serious leisure and recreation specialization. Leisure Sciences, 30(4), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400802165115

- Unruh, D. R. (1980). The nature of social worlds. Pacific Sociological Review, 23(3), 271–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388823

- Van Boven, L. (2005). Experientialism, materialism, and the pursuit of happiness. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.132

- Wheatley, D., & Bickerton, C. (2019). Measuring changes in subjective well-being from engagement in the arts, culture and sport. Journal of Cultural Economics, 43(3), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-019-09342-7