ABSTRACT

Second homes are of great sociocultural importance in many countries, and their significance intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic when they acted as refuges in times of crisis. However, the growth and unsustainable impact of second-home tourism questions second-home tourism’s value for host communities and their residents, how it affects destination and place, and collaborative processes. After emphasizing economic and environmental aspects of sustainability in second-home tourism, attention is now directed to the inclusion of the social dimension in tourism and policies due to the implementation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. This study investigated second-home tourism’s effects on a community and how social sustainability elements can drive innovation to fashion a destination and place for everyone involved, using the case of Øyer Municipality in Southeast Norway. By analyzing tourism strategy goals, political policies, and in-depth interviews, results revealed a gap between strategy goals and the informants’ perspectives, indicating that a lack of resident involvement in innovation processes and poor collaboration between stakeholders affect residents’ quality of life, visitor satisfaction, and destination development. However, economic aspirations and growth involved in second-home development continue to prevail.

Introduction

Since the United Nations’ introduced the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), sustainability has gotten a progressively distinguished and recognized role in tourism for improving the utilization of tourism development and policies (Hall, Citation2019; United Nations, Citationn.d.-c). Sustainability also plays a central role in second-home tourism research with its environmental impacts, social aspects and community, planning, rural development, and economic influences (Müller & Hall, Citation2018, pp. 3–6). In the Nordic, more than half of the population has access to a second home (Åkerlund et al., Citation2015). However, the consequent seasonal variability causes challenges for residents and host communities regarding unsustainable impacts (Xue et al., Citation2020), and public service provision, typically overlooked in policy and planning (Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017). Although clearly correlated, second-home tourism’s impacts are often neglected in tourism strategies and political policies, (Adamiak et al., Citation2017). To implement sustainable tourism in second-home destinations, governmental tools, proactive collaboration, and utilization of external resources should be advocated (Slätmo et al., Citation2019, pp. 47–49).

The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to more emphasis on the social dimensions of sustainability in popular tourist and second-home destinations, in terms of residents’ safety, resilience, and quality of life (Gallent, Citation2020; Helgadóttir et al., Citation2019) as it became more apparent how tourism impacts host communities’ sociocultural aspects. In Norway, the pandemic encouraged a more diverse discourse related to second-home tourism, a phenomenon heretofore modestly questioned in terms of its value and sustainability for residents and communities (Haukeland et al., Citation2021). While second-home development has been argued to contribute to regional economic growth, it also causes tension regarding residents’ needs, the right to roam, and tourist development in untouched nature. Thus, controversies have emerged over how second-home destinations should maintain economic growth if it is inconsistent with residents’ social, cultural, and moral values (Ericsson et al., Citation2022). Often, residents are hardly heard in such debates (Kaltenborn et al., Citation2008). As second-home destinations face increasing sustainability challenges, it is important to understand what contributes to community well-being, how to implement these processes and practices, and who needs to be involved. However, limited research exists on how local communities in Norway cope with second-home tourism in terms of social sustainability (Blumenthal, Citation2021). Public service development at such destinations is usually based on permanent population (Paris, Citation2014). Policies and planning may therefore negatively impact the potential for second-home development and its benefits.

A greater focus on sociocultural pillars of sustainability and a more holistic perspective on tourism’s impacts on destinations are needed amongst public administrations and stakeholders (OECD, Citation2021a). When analyzing societal structures, they can be viewed from a social innovation perspective, which entails improving social and economic performance through progressive alternatives (Mosedale & Voll, Citation2017, p. 102). Communities should be made inclusive, resilient, and sustainable (SDG 11 – Sustainable Cities and Communities, UN). This focus is relevant to second-home owners. often characterized as part-time residents rather than tourists. Deeper understanding is needed of sociocultural processes and relationships that characterize actors in destinations (Fan, Citation2023), which in turn could highlight indicators of innovation and sustainability in the tourism context (Streimikiene et al., Citation2021).

This study focuses on Øyer, Southeast Norway, in the Inland region – highest growth area for second-home development (Statistics Norway, Citation2022), which has long been discussed in relation to the benefits and disadvantages of second-home tourism and what value it brings to the host community. We aim to investigate how elements of social sustainability can serve as a driver of innovation, and which stakeholders are involved and not in the innovation processes. Social sustainability is typically linked to human rights, diversity, and equity (United Nations, Citationn.d.-b). In this study, social sustainability is understood as what is required to secure residents’ needs and improve their quality of life in a destination while limiting tourism’s unsustainable impacts. The research questions are as follows:

RQ1: How has second-home tourism affected Øyer as a place?

RQ2: Which elements of social sustainability can serve as drivers of innovation, and who is involved in this process?

Literature review

Second-home tourism and development

Improved socioeconomic processes and a wish to escape the city have made second homes in rural areas attractive for recreation across Europe (Gallent et al., Citation2017, p. 19; Ursić et al., Citation2017). Second-home tourism is usually viewed positively in terms of regional tourism development and economic benefits, such as added value and employment opportunities (Müller et al., Citation2004, p. 17). The accumulated growth in second homes, however, has negative socioeconomic consequences (Gallent, Citation2014), including undesirable influences on real estate (Brida et al., Citation2011), loss of landscape and village appearances (Sonderegger & Bätzing, Citation2014), displacement (Marjavaara, Citation2009), and strain on public services and infrastructure (Oliveira et al., Citation2015). These impacts are often visible in the development of destinations and places due to atomistic approaches in second-home tourism planning (Slätmo et al., Citation2019, pp. 47–48). While destination development focuses on the overall area and how to be attractive to visitors, place development emphasizes on improving the quality of experiences for both tourists and residents. The understanding of place in tourism research contains a variety of concepts, such as place-making, place image, and sense of place (see: Lew, Citation2017), this study focuses on how the development of place, or the lack thereof, affects both visitors and residents.

Emotions and attachment to place become amplified as second-home owners long for authenticity, rurality, and “escape” from society while at the same time wanting to access the urban way of life (Aronsson, Citation2004). Since a place is not constant but has multiple identities within a social construct, it is bound to be a source of conflict (Massey, Citation1995). Emphasizing the concept of place can help to identify challenges and benefits with the collaboration between actors. Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017) stress that second homes should be analyzed heterogeneously, not unitarily, to gain a better understanding of second-home tourism with more sensitivity to place and local context.

The benefits and disadvantages of second-home tourism are usually discussed vis-à-vis sustainability, including economic growth and value (Velvin et al., Citation2013), environmental impacts (Hiltunen et al., Citation2016), and social concerns (Huijbens, Citation2012). In the Nordics, the sustainability discourse in second-home research has focused mainly on economic dimensions, environmental impacts, planning, and institutional issues (Müller, Citation2021). Considerable attention has been paid to the social aspects of second-home tourism in relation to residents, communities, and second-home owners, including place attachment (Aronsson, Citation2004), property inequality and social value (Hjalager et al., Citation2023), residents’ perceptions of second-home tourism (Rye, Citation2011), and densification (Ellingsen & Nilsen, Citation2021). In Finland, Hiltunen et al. (Citation2016) discovered that large socioeconomic differences between residents and second-home owners could cause negative consequences where the gap in capital forms a power imbalance benefiting second-home owners, imposing negative attitudes from the local community. Marjavaara et al. (Citation2019) show examples of research on second-home tourism in Sweden and how it has impacted destinations and residents and compare negative impacts of second homes with overtourism.

In Norway, Kaltenborn et al. (Citation2008) found residents’ attitudes toward second-home development in Øyer and Vestre Slidre in Southeast Norway were mostly positive as long as environmental or economic benefits ensued. This is supported by Farstad and Rye (Citation2013), who found that rural development was not opposed as long as residents were not affected. Both studies show the importance of local context and how the diversity of factors can affect outcomes. Understanding the significance of place and stakeholders’ (residents, second-home owners, and municipalities) perspectives can prove importance in place and destination development, contributing to the host community (Ellingsen & Nilsen, Citation2021; Farstad, Citation2011).

Second-home tourism and social sustainability

While sustainability, opportunities, and challenges vis-à-vis second-home tourism have been researched extensively, scarce attention has been given to how second-home development affects recreational areas in terms of the SDGs (Hjalager et al., Citation2022). The economic aspirations in second-home tourism have overshadowed long-term sustainability, and economic benefits and distribution may be uncertain, questioning long-standing assumptions about social sustainability in such communities (Ericsson et al., Citation2022; Hall, Citation2015). Although social concerns have been addressed, they have not necessarily been emphasized as an aspect of social sustainability. Social sustainability is used to understand the “positive and negative impacts of systems, processes, organizations, and activities on people and social life” (Balaman, Citation2019, p. 86). In tourism research, social sustainability is concerned with understanding the well-being and needs of people, and how different variables, indicators, and impacts affect residents’ quality of life (Helgadóttir et al., Citation2019). Social sustainability is a collective term for the social impacts of tourism and can be found under topics such as overcrowding, place attachment, community impact, residents’ quality of life well-being, perception, and attitudes (Andereck & Nyaupane, Citation2011). Communities, residents, and their needs and well-being are elements of social sustainability and can be used as a measurement of welfare, which includes promoting well-being for all, making communities inclusive, resilient, and sustainable (SDG 3 – Good Health and Well-being; SDG 11, UN).

The social impacts of Norwegian second homes have been examined in relation to nature conservation policy, planning, and nature-based tourism (Skjeggedal & Overvåg, Citation2015), not necessarily in terms of social sustainability and the related SDGs. Ericsson et al. (Citation2022) and Breiby et al. (Citation2021) have linked social sustainability and SDGs to the unsustainable impacts of second-home development in Southeast Norway, showing how power imbalances hinder sustainable second-home development and causing impacts such as loss in sense of place and identity. The massive growth of second-home tourism and its related processes appear to have proved difficult for private and public stakeholders’ adaptability, causing them to be omitted from relevant processes and leading to inadequate approaches and development (Overvåg & Berg, Citation2011).

Several studies note that various social groups own or have access to a second home (Atkinson et al., Citation2009; Hoogendoorn, Citation2011). However, the way second-home development is progressing excludes different social groups from obtaining or partaking in certain second-home areas, affecting elements of social sustainability, challenging the idea of egalitarianism (Rye, Citation2011)

Social innovation

Several studies have noted the importance of second-home owners’ access to resources, e.g. bridging external networks, capital, social connections, and capability (Gallent, Citation2014; Nordbø, Citation2014), which can act as innovation agents (Carson et al., Citation2016, p. 188). Innovation in communities comprises adapting new knowledge, products, and services, allowing communities to take advantage of changing circumstances and stimulate socioeconomic growth (Sullivan et al., Citation2014). In terms of social innovation, the aim is to implement new solutions, challenge existing standards, and provide social outcomes benefiting residents (Totcheva et al., Citation2019, p. 105). Research on social innovation in tourism is commonly found in the context of community-based tourism, governance, social entrepreneurship, sharing economy, and social platforms/networks (Mosedale & Voll, Citation2017). Social innovation is not a new concept, yet it is conceptually imprecise (Aksoy et al., Citation2019; Ayob et al., Citation2016) and a relatively new notion within tourism research. Thus, more attention should therefore be given to social innovation initiatives and what role actors play in these processes (Vercher, Citation2022).

Aiming to understand whether and how social innovation can contribute to enhancing holistic sustainability in tourism Partanen (Citation2021) developed a four-dimensional framework. Using empirical evidence from Kemi, Finland, a destination troubled to keep up with the increased demands of tourism, Partanen found that fostering multi-sectoral dialogue and responding to local needs help create novel solutions, as well as strengthening sustainability in the tourism sector. Partanen proposes the four following dimensions: (1) the need for transformation, (2) new perspectives, (3) a bottom-up approach, and (4) co-creation process outcomes. The first dimension comprises identifying challenges and needs for change, e.g. implementing SDGs or collaboration between stakeholders. The second dimension concerns the potential for change and how it can contribute to transforming destinations in terms of the societal aspects of sustainability and residents’ well-being. Stakeholders can contribute to identifying destinations’ needs, adopting new approaches, shifting perceptions, and emphasizing sociocultural synergies (OECD, Citation2021b). Relevant stakeholders are second-home owners, residents, landowners, and municipalities. As emphasized in the third dimension, a bottom-up approach in which stakeholders’ collaboration aids the development of a holistic, sustainable destination and place. Highlighting place attachment in this approach contributes to positive connections between person and place. The fourth dimension focuses on the outcomes of social innovation and their implications. Collaboration and community involvement should be central to destination development to ensure a strong, sustainable future (Bertella, Citation2022). Viewing tourism as a social force, rather than merely a business opportunity, can contribute to more socially sustainable directions.

To the authors’ knowledge, Partanen’s model of social innovation has yet to be applied empirically, and this study tests the model in a new, Norwegian empirical context.

Case context

Norway has approximately 500,000 s homes, and the number keeps increasing (Statistics Norway, Citation2023b). About 43% of the population is estimated to own a second home, while more than half have access to a second home (Larsen & Sti, Citation2020; Statistics Norway, Citation2023a). Second homes are of great sociocultural importance in Norway, emphasizing family time and attachment to nature (Berker et al., Citation2011, p. 9). However, they also cause encroachment on nature and landscapes, causing community distress. Since outdoor recreation is a valued custom along with second homes, these disputes might stem from a perceived infringement of said custom, creating social tensions.

Øyer

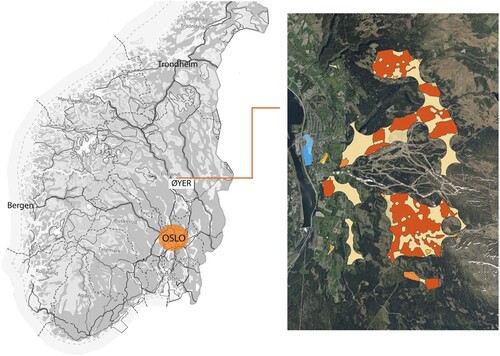

Øyer is one of Norway’s and Scandinavia’s biggest ski and winter destinations, thanks to its co-hosting of the 1994 Winter Olympic Games (Andersen et al., Citation2018). It is a small rural municipality in Southeast Norway’s Inland region, two hours north of the capital, Oslo. The Inland region is the largest second-home county in Norway, with a significant increase of second homes in the last decade, Øyer being amongst the highest increase (Statistics Norway, Citation2023a) (see ). Second homes in Øyer are mainly located around the ski resort, Hafjell, as shown in (Kartverket, Citation2023). Øyer was chosen as a case for its unique composition in terms of geographical location and its visible influences of tourism. As a rural village, Øyer has limited health service capacity, posing challenges in peak season. Øyer is dependent on second homes and nature-based tourism, and although second-home tourism is argued to benefit the local and regional economy, it has caused unsustainable impacts, such as encroachment of nature, local disputes regarding grazing animals, overcrowding, and pressure on infrastructure. Thus, Øyer is often used as an example showcasing the negative impacts of second-home tourism ().

Figure 1 . Map of the case area. The red shows second-home areas, and the blue represents the town center (© Kartverket/Norgeskart Statistics Norway, Citation2021b).

Table 1 . Øyer municipal and second-home statistics.

Materials and methods

This study’s qualitative approach comprised interviews and document analysis, offering a comprehensive, contextual, and nuanced understanding of the case and allowing triangulation.

Design and data collection

Documents

Document analysis was used to comprehend events and strategies for future tourism development vis-à-vis second homes and outdoor recreation. The review provided the historical, sociocultural, and policy contexts, contributed data for related concepts before the interviews, and suggested strategies and objectives for further investigation. Documents were selected based on the criteria of focusing on residents’ quality of life, second-home development, and all sustainability aspects – particularly social. Political policies and tourism strategies were obtained from public administrations and public and private stakeholders, mostly through open access, except for one unpublished document. As documents might be biased and omit vital information, other sources of real-life data (Clark et al., Citation2021, pp. 514–515), interviews were deemed beneficial. outlines the sampled documents and data analyzed.

Table 2 . Documents used in the analysis.

Interviews

Interviews were chosen as an additional approach as they enable a comprehensive exploration of the social phenomenon at hand, provide a platform to share perspectives, engage respondents in the research process, and are rich in detail. Ten in-depth interviews were conducted from January to March 2022. Residents, second-home owners, and government representatives were recruited via local community groups on Facebook. Purposive sampling approach was applied with the following criteria:

Ownership duration of second homes: new (<3 years), established (5–7 years), and long-term owners (≥10 years)

Years of residency in Øyer (>5 years)

Equal gender rate (Six males, four females)

The participants’ ages ranged from the mid-thirties to the mid-sixties, as the age group is likelier to afford primary and second homes (Statistics Norway, Citation2017, Citation2023c) and had prolonged connections to Øyer. The in-depth interviews ranged from 45 to 1 h 40 min; the variations were due to the respondents’ circumstances and backgrounds. The interviews, which were face-to-face, digital, or by phone, were digitally recorded, transcribed, and coded before being erased. The semi-structured interview guide aimed to create a narrative without disturbances or influence (Taylor, Citation2005). The main topics of the questions in the interview guide were concentrated on social sustainability, inclusion/co-creation, and destination/place development, based on research discourse on social sustainability in tourism, second-home development in Norway, current affairs, and policies. A different interview guide was provided for public administration representatives, with questions focusing on their point of view, while still staying within the same topics. The questions focused on the respondent’s feelings towards Øyer as a destination and place and related development, positive and negative impacts of second homes and tourism, services, value-creation, satisfaction, and what is missing in Øyer.

shows the respondents’ characteristics and their association with Øyer. For second-home owners, the national level represents the Oslo area, the regional level is from the Inland region, and the local level is former residents.

Table 3 . Respondent characteristics.

Data analysis

The document analysis contributed toward a non-biased outlook and improved the categories based on the initial literature review and the topics the respondents suggested. Because documents from private sources are not necessarily objective, they should be examined in the context of other data sources to mitigate potential bias (Natow, Citation2020). The documents were analyzed to identify themes related to residents’ quality of life, second-home development, and sustainable tourism in rural areas. To enhance validity, information from documents was cross-verified to uncover how different stakeholders viewed different topics related to place and destination development/strategies. Themes and codes were extracted where documents mentioned place development, innovation processes, benefits and disadvantages of second-home tourism and tourism in general, rural development (e.g. resident involvement), and matters associated with sustainability: residents’ quality of life, and environmental and sociocultural impacts.

The interview data underwent the same thematic process as the document analysis. Respondents’ perspectives were compared to strategy and policy goals to see if they aligned or diverged, and how these issues related to social sustainability. The interviews were coded manually, allowing connections between codes and relations among respondents. The transcribed data were divided into three broader parts based on the group: residents, second-home owners, and government officials, resulting in four main categories:

Challenges, such as infrastructure, sustainability, collaboration

Local community, involving well-being/quality of life, attachment

Second-home tourism, concerning inclusion, co-creation, resource contribution

Regional governance, regarding policies, development (of destination and place), resources

Results

The interviews and document analysis uncovered several challenges and needs for change related to residents’ quality of life, second-home development, and private–public stakeholder collaboration. The coding process revealed an inconsistency in the sustainability goals and strategies described in the documents, how informants perceived and understood the same goals and strategies, and how they benefited. The results are based on the core categories from the data analysis and reflect Partanen’s four dimensions.

Identifying challenges and the need for change

Innovation Norway (Citation2021a, p. 7) suggests destinations involve holistic development based on visitors’ and residents’ needs, but this is a complex process with several issues and actors involved. Issues include the lack of resources and collaborative processes, a common occurrence in Norwegian municipalities that challenges planning and destination development (see : N1, N2). As sustainable tourism development is intertwined with place development, planning, accessibility, and thriving local communities, the process needs to identify and systemize the destination through collaboration between the involved actors. Several destinations in Norway are seasonal and present overtourism tendencies in the peak season. Facilitating activities and spreading demand year-round could lessen the load in terms of sustainability, hindering the attrition of natural and cultural values (N2).

For regional governance, challenges related to limited resources, capacity issues, unfinished planning, and finances. With a disproportional infrastructure compared to its permanent population, the municipality allots excessive resources to maintenance, and continuous second-home development has strained its capacity. Second-home tourism was mostly discussed in relation to economic development, hindering dialogue of new practices:

The train might have left the station if they [stakeholders] can’t understand the consequences of not involving residents […] and how this, in turn, creates greater democracy. (G2, )

Both residents and second-home owners voiced concerns about communication, inclusion, involvement, well-being, and private–public stakeholder collaboration. The residents expressed concerns about a lack of place development, meeting places, overcrowding, feeling excluded in the municipality, and overall information (or its absence). They perceived economic aspirations to exceed local needs or that their needs were ruled out in planning activities and services. Second-home owners described encountering impediments to their overall experience on the mountain, such as grazing animals, mobility, and a lack of information from the municipality. Most owners agreed that second-home development was out of control and amplified during the pandemic, while others did not view this as an issue, stating that in the most commercial second-home area in Norway, people should set expectations accordingly. While some stated that residents should be thankful for the benefits second-home tourism brings to the community and the region, others saw how it might affect the social standing of some in the community: Tourism probably contributes to creating big social differences in Øyer. (S2, )

New perspectives and practices for well-being

Few national strategies emphasize the role second-home tourism can play in a destination and how it may impact visitors’ satisfaction, community, and residents. This lack of emphasis transcends to regional and local strategies and policies that highlight tourism growth, infrastructure, climate change, and the economic value of second-home tourism, but social impacts and tourism are not viewed in correlation to each other. As sustainability in tourism is dynamic and complex, it requires methods reflecting meaningful changes and approaches ensuring tourism adds value to local communities (N4, p. 6).

The lack of planning, exclusion of processes, and inconsideration of residents’ needs affected their quality of life. For example, residents felt excluded from the town center and stores due to crowding or general undesirability, recreational areas were “full,” activities too expensive, and they felt excluded from planning and development by the municipality and other stakeholders. The town center is affected by the municipality’s unfinished development plan, contributing to a lack of belonging in a place designed for visitor shopping:

The grocery store used to have a bakery and patisserie, which were closed so they could set up a liquor shop, and then the sports store moved in. There you have it – the three main ingredients that visitors and second-home owners want, gathered in one place, and then they don’t use the rest of the town center […] They [the municipality] could’ve seen the potential of second-home development and planned accordingly. (I2, )

It’s a conflict democracy […] there’s a need for facilitating involvement, having an open process, allowing inputs, actively including residents, and discussing things before they are decided. (I3, )

Bottom-up approach

Alpinco (L2, p. 5), which owns the Hafjell ski resort, claims tourism development is regressing due to outdated policies and a lack of collaboration between stakeholders. Destination management with clearly defined responsibilities is lacking, creating difficulties for several actors. Poor town center planning can appear destructive for the place and the destination (Innovasjon Norge [Innovation Norway], Citation2021a, p. 88). Building a stronger destination identity, increased collaboration between stakeholders, and sustainability as the foundation are the tourism goals for the region and are recommended by national tourism strategies (see , N3; , R2). They could contribute to increased visitor satisfaction and community engagement. Basing tourism development on the foundation of SDGs offers a more systematic approach to achieve increased facility, improved social cohesion, economic diversification, and enhanced social services: It is important to see that one is simply not sustainable per se, as it entails continuous improvement to become more sustainable. (L2, ).

Lack of political will to accommodate requests for improved destination management hinders proper administration and collaboration between actors, obstructing the chances of new, innovative practices (Innovasjon Norge [Innovation Norway], Citation2021a, ). Regional governance suggests the local emphasis should be on becoming a holistic year-round destination to provide permanent jobs, increase stability, and secure income, making the place attractive for newcomers, and thus ensuring sustainability. Regionally, the suggestion was to learn from neighboring destinations, highlighting the difference between a place (for residents) and a destination (for visitors), claiming Øyer is the latter (G2, ).

Residents and second-home owners commonly stated that tourism and second-home development do contribute to the community in terms of services, resources, and job opportunities; dissatisfaction was expressed about how processes were carried out. Having the opportunity to contribute and provide feedback was desired but regarded as difficult.

Second-home tourism has affected the local community in terms of a sense of belonging, the use of public space, and sustainability. A greater emphasis on residents’ needs and participation in the planning and execution of the destination is required, as well as including second-home owners’ perspectives, which can only stem from collaborative processes between stakeholders, stressing the social aspect of sustainability.

Discussion

Results demonstrated that second-home tourism in Øyer has been affected in terms of place, destination development, residents’ quality of life, second-home owners’ inclusion, and overall co-creation. To understand which elements of social sustainability can be drivers of innovation, this study used Partanen’s (Citation2021) framework of social innovation in relation to resilience to identify challenges, classify the potential for change, emphasize a bottom-up approach, and focus on the outcomes and implications of social innovation.

Impacts of second-home tourism on destination and place

To understand the impacts of second-home tourism on a destination and place, one needs to identify the challenges hindering development and new practices, recognize the residents’ needs and second-home owners’ perspectives, and actively work for change and improvements with sustainability in mind. Our results indicate that second-home tourism has affected Øyer as a place and destination. Inadequate encouragement of resident involvement and lack of holistic place development affects residents’ quality of life in terms of prosperity, access to activities and public space, sense of place, and signs of local inflation. To enhance the attractiveness of place, Øyer lacks collaborative processes that can provide holistic and sustainable second-home development.

The absence of resident involvement or including second-home owners’ perspectives contributes to a feeling of dejectedness. Farstad and Rye (Citation2013) link this to “not in my backyard” logic, where people are content with second-home tourism and related development if they remain unaffected. If contributing to improved service and public facilities and infrastructure, residents are content with second-home tourism, but further growth causes social, economic, and environmental issues to arise (Farstad, Citation2011; Kaltenborn et al., Citation2008). In Øyer, the overall dissatisfaction related to place and destination development is found in the overwhelming boom of second-home tourism. The impact on rural communities with limited administrative resources results in an imbalance in public services, priorities, and resources (see: Overvåg & Berg, Citation2011). Overall, the sentiment was that second-home tourism contributes to the community, but the related unconstructive processes around it impacted its contribution, causing the perception that economic needs exceed social ones, causing negative socioeconomic associations with second-home tourism (Hiltunen et al., Citation2016).

New social practices for sustainability and co-creation

Results indicate that national strategies have a greater emphasis on sociocultural elements and how an imbalance in these elements, e.g. lack of co-creation and inclusion, affects the identity and desirability of the destination and place. This, in turn, impacts visitors, in this context second-home owners. Regional strategies showed somewhat contradictory input, where sustainability is to play a central role, but so are increased tourism flows, stressing the economic influence of second-home tourism rather than discussing its impact on local communities.

It is important to understand sustainability and second-home tourism within a local context and more emphasis on place (Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017; Ericsson et al., Citation2022), as certain effects of second homes are conditioned by social, cultural, geographical, and economic contexts. A lack of clear guidelines and strategies has made destination development in Norway incoherent, along with poor collaboration between stakeholders (Pedersen, Citation2020), which in turn transcends to second-home tourism development. By ignoring several community impacts, challenges arise when a holistic and sustainable destination is to be implemented (Partanen, Citation2021), which also poses difficulties in adopting priorities and guidelines at a regional level. This demonstrates the need for an innovative social approach – e.g. prioritizing a bottom-up approach and recognizing the outcomes of tourism processes and whom they benefit.

To promote collaborative processes and encourage changes in tourism practices and policies in second-home destinations, social sustainability is vital. The results indicate elements of social sustainability such as inclusion, well-being, bottom-up approach, and co-creation can play an important role in ensuring sustainable development for destination and place, and people's well-being. Using residents and second-home owners as existing resources, with their networks and assets, can contribute to new social practices facilitating active involvement and participation of individuals in decision-making processes (Gallent, Citation2014). Thus, contributing to community engagement and opening for new, innovative ways for stakeholders to assess, and adjust for the place and destination to be more socially inclusive, enhancing the quality of life, satisfaction, and place/destination attractiveness. This can prove vital in rural areas with limited resources and capital.

If not taken into consideration, it can impact the outcomes of strategies, policies, and collaborative processes, ultimately hindering elements of social sustainability. Hence, this study suggests a greater focus on SDGs 3 and 11 for guidance and application toward sustainable development of destination and place, as they emphasize well-being, inclusion, collaboration, and sustainable communities and destinations,

As such, there are shortcomings in the social sustainability approach due to the absence of collaborative processes, citizen involvement, resources, and poor information flow, hindering social innovations and new practices. The goal should be to mitigate negative impacts and maximize social outcomes benefitting the communities, residents, and visitors of popular tourist destinations.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to investigate how second-home tourism has affected the place of Øyer, which elements of social sustainability can serve as drivers of innovation, and who should be involved in the process. Second-home tourism has impacted the place of Øyer negatively in terms of place development, strained local infrastructure, public services, and resources, in turn affecting the sense of place, attachment, and quality of life for residents. For second-home owners, second-home tourism impacted the attractiveness and the overall experience of the destination. The lack of collaboration and inclusion hinders both groups from involving themselves in new practices that could improve overall well-being and the place of Øyer. It was a mutual sentiment that second-home tourism contributes to the community; however, the practices and collaboration around it, or the lack thereof, caused discontent.

As shown, elements of social sustainability, such as well-being, community involvement, co-creation, inclusion, and quality of life are important to emphasize in the development of destination and place to ensure that new social practices enhance the sociocultural contributions to a community. There is a contradiction between who is involved in the processes of destination and place development, and who should be involved in order to provide a bottom-up approach, ensuring the level of sustainability that stakeholders strive to achieve. This in turn creates a gap in understanding the contribution, value, and development second-home tourism has toward host communities, how these resources should be distributed, and whom they should benefit. In other words, a “good society” is built from below, emphasizing people’s different roles and relationships, and viable, thriving local communities are a prerequisite for such development.

This study contributes to the theory in three ways. First, using Partanen’s framework in an empirical Norwegian second-home context offers new ways to identify the needs, challenges, and key drivers of social innovation in popular tourist destinations with a bottom-up approach and emphasis on co-creation. Second, the study describes the complexity of the social aspect of sustainability in tourism and its related impacts. Finally, the study contributes to a more holistic theoretical approach to social sustainability in second-home tourism research and practices.

The practical implications are policymaking to promote sustainable tourism practices with a more sociocultural than growth-oriented approach. Tourism and second-home development should integrate responsibility for the planet, allowing stakeholders to understand the importance of engaging with residents, respecting cultural values, and giving back to the community. Furthermore, the results show the complications of implementing SDGs in tourism and policy practices and the consequences of neglecting the social aspect of sustainability.

The study has certain limitations, as local municipal strategies and policies are being updated, making it difficult to suggest further action based on previous policies. This also makes it challenging to point out the actual social outcomes regarding Partanen's fourth dimension, as they have yet to happen. Further research on the social impacts of second-home development and related tourism is necessary, as the social sustainability perspective contributes to policymaking that emphasizes destination and place, improves social interactions, participation, and practices, and ensures the well-being of the community and visitors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the respondents for taking the time to participate in interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adamiak, C., Pitkänen, K., & Lehtonen, O. (2017). Seasonal residence and counterurbanization: The role of second homes in population redistribution in Finland. GeoJournal, 82(5), 1035–1050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-016-9727-x

- Åkerlund, U., Lipkina, O., & Hall, C. M. (2015). Second home governance in the EU: In and out of Finland and Malta. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(1), 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2014.933229

- Aksoy, L., Alkire, L., Choi, S., Kim, P. B., & Zhang, L. (2019). Social innovation in service: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Service Management, 30,. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-11-2018-0376

- Alpinco & Mimir. (2020). Hafjell mot 2030 [Hafjell toward 2013]. https://www.oyer.kommune.no/ato/esaoff/document/masterplan-hafjell-mot-2030-oktober-2020.502355.20631ecb3d.pdf

- Andereck, K. L., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2011). Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. Journal of Travel Research, 50(3), 248–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362918

- Andersen, O., Øian, H., Aas, Ø, & Tangeland, T. (2018). Affective and cognitive dimensions of ski destination images. The case of Norway and the lillehammer region. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(2), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2017.1318715

- Aronsson, L. (2004). Place attachment of vacation residents: Between tourists and permanent residents. In D. K. M. C. Michael Hall (Ed.), Tourism, mobility and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground (pp. 75–86). Channel View Publications.

- Atkinson, R., Picken, F., & Tranter, B. (2009). Home and away from home: The urban-regional dynamics of second home ownership in Australia. Urban Research & Practice, 2(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535060902727009

- Ayob, N., Teasdale, S., & Fagan, K. (2016). How social innovation ‘came to be’: Tracing the evolution of a contested concept. Journal of Social Policy, 45(4), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004727941600009X

- Back, A., & Marjavaara, R. (2017). Mapping an invisible population: The uneven geography of second-home tourism. Tourism Geographies, 19(4), 595–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1331260

- Balaman, ŞY. (2019). Chapter 4 – Sustainability issues in biomass-based production chains. In ŞY Balaman (Ed.), Decision-making for biomass-based production chains (pp. 77–112). Academic Press.

- Berker, T., Gansmo, H. J., & Jørgensen, F. A. (2011). Hyttedrømmen mellom hjem, fritid og natur [The second-home dream between home, leasure and nature]. In J. G. Helene, B. Thomas, & J. Finn Arne (Eds.), Norske hytter i endring: Om bærekraft og behag [Changing Norwegian second homes: About sustainability and comfort] (pp. 9–22). Tapir akademiske forlag.

- Bertella, G. (2022). Discussing tourism during a crisis: Resilient reactions and learning paths towards sustainable futures. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 22(2), 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2022.2034527

- Blumenthal, V. (2021). Fritidsboligbefolkningen og lokalsamfunnet – Kan fritidsboligeierne bli en ressurs for lokal utviking? [Second-home owners and the local community - a resource for local development?] (8283803123). https://www.ostforsk.no/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Rapport-22-2021-OF-HINN-Blumenthal.pdf

- Breiby, M. A., Øian, H., & Aas, Ø. (2021). Good, bad or ugly tourism? Sustainability discourses in nature-based tourism. In P. Fredman, & J. V. Haukeland (Eds.), Nordic perspectives on nature-based tourism (pp. 130–142). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Brida, J. G., Osti, L., & Santifaller, E. (2011). Second homes and the need for policy planning. Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism, 6, 141–163. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1468422

- Carson, D. A., Cleary, J., de la Barre, S., Eimermann, M., & Marjavaara, R. (2016). New mobilities–new economies? Temporary populations and local innovation capacity in sparsely populated areas. In A. J. Taylor, D. B. Carson, P. C. Ensign, & A. Taylor (Eds.), Settlements at the edge: Remote human settlements in developed nations (pp. 178–206). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Clark, T., Foster, L., Sloan, L., & Bryman, A. (2021). Bryman's social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Ellingsen, W., & Nilsen, B. T. (2021). Emerging geographies in Norwegian mountain areas – Densification, place-making and centrality. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 75(2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2021.1887347

- Ericsson, B., Øian, H., Selvaag, S. K., Lerfald, M., & Breiby, M. A. (2022). Planning of second-home tourism and sustainability in various locations: Same but different? Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography, 76(4), 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2022.2092904

- Fan, D. X. F. (2023). Understanding the tourist-resident relationship through social contact: Progressing the development of social contact in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 406–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1852409

- Farstad, M. (2011). Rural residents’ opinions about second home owners’ pursuit of own interests in the host community. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 65(3), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2011.598551

- Farstad, M., & Rye, J. F. (2013). Second home owners, locals and their perspectives on rural development. Journal of Rural Studies, 30, 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.11.007

- Gallent, N. (2014). The social value of second homes in rural communities. Housing, Theory and Society, 31(2), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2013.830986

- Gallent, N. (2020). COVID-19 and the flight to second homes. Town & Country Planning, 89, 141–144.

- Gallent, N., Mace, A., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2017). Second homes: European perspectives and UK policies (Second edition ed.). Routledge.

- Hall, C. M. (2015). Second homes planning, policy and governance. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2014.964251

- Hall, C. M. (2019). Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1044–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560456

- Haukeland, J. V., Dybedal, P., Landa-Mata, I., Gundersen, F., & Stokke, K. B. (2021). Covid-19 og reiselivet i Hallingdal – En pilotstudie av effektene av koronapandemien i 2020 [Covid-19 and tourism in Hallingdal–A pilot study of the impacts of the corona virus pandemic in Hallingdal in 2020].

- Helgadóttir, G., Einarsdóttir, A. V., Burns, G. L., Gunnarsdóttir, GÞ, & Matthíasdóttir, J. M. E. (2019). Social sustainability of tourism in Iceland: A qualitative inquiry. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 19(4-5), 404–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2019.1696699

- Hiltunen, M. J., Pitkänen, K., & Halseth, G. (2016a). Environmental perceptions of second home tourism impacts in Finland. Local Environment, 21(10), 1198–1214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2015.1079701

- Hiltunen, M. J., Pitkänen, K., Vepsäläinen, M., & Hall, C. M. (2016b). Second home tourism in Finland: Current trends and eco-social impacts. In Z. Roca (Ed.), Second home tourism in Europe (pp. 165–198). Routledge.

- Hjalager, A.-M., Sørensen, M. T., Steffansen, R. N., & Staunstrup, J. K. (2023). Sales prices, social rigidity and the second home property market. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-023-10047-9

- Hjalager, A.-M., Staunstrup, J. K., Sørensen, M. T., & Steffansen, R. N. (2022). The densification of second home areas – Sustainable practice or speculative land use? Land Use Policy, 118, 106143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106143

- Hoogendoorn, G. (2011). Low-income earners as second home tourists in South Africa? Tourism Review International, 15(1-2), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427211X13139345020219

- Huijbens, E. H. (2012). Sustaining a village's social fabric? Sociologia Ruralis, 52(3), 332–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2012.00565.x

- Innovasjon Norge [Innovation Norway]. (2021a). Håndbok for reisemålsutvikling rev.ed. [Handbook for destiantion development, revised edition]. https://assets.simpleviewcms.com/simpleview/image/upload/v1/clients/norway/in_handbok_final_online_191115_df8f6ecc-f7ff-4309-848d-884196b6f208.pdf

- Innovasjon Norge [Innovation Norway]. (2021b). Nasjonal reiselivsstrategi: Sterke inntrykk med små avtrykk [National tourism strategy: Big impacts, small footprint]. https://assets.simpleviewcms.com/simpleview/image/upload/v1/clients/norway/Nasjonal_Reiselivsstrategi_original_ny_en_cbbfb4a4-b34a-41d4-86cc-f66af936979d.pdf

- Kaltenborn, B. r. P., Andersen, O., Nellemann, C., Bjerke, T., & Thrane, C. (2008). Resident attitudes towards mountain second-home tourism development in Norway: The effects of environmental attitudes. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(6), 664–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802159685

- Kartverket [The Norwegian Mapping Authority] (2023). Norgeskart [Map of Norway]. https://www.norgeskart.no/#!?project=norgeskart

- Kommunal- og distriktsdepartmentet [Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development]. (2019). Levende lokalsamfunn for fremtiden – Distriktsmeldingen [Thriving communities for the future. Regional message. Parliament message 5]. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-5-20192020/id2674349/

- Larsen, M. M., & Sti, T. K. (2020, September 1). Nordmenn har brukt 200 milliarder på hytte [Norwegians have used 2000 million dollar on second homes]. Finansavisen [The Norwegian Financial Daily]. https://www.finansavisen.no/premium/livsstil/2020/04/03/7511465/nordmenn-har-brukt-200-millarder-pa-hytte

- Lew, A. A. (2017). Tourism planning and place making: Place-making or placemaking? Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 448–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1282007

- Lillehammer Gudbrandsdal Byregionprogam [City Region Program]. (2016). By og fjell – moderne bosetting som grunnlag for utvikling og verdiskaping [City and mountain – modern settlement as a basis for development and value creation]. https://distriktssenteret.no/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Lillehammer-Prosjektbeskrivelse-ByR2-160215.pdf-L304446.pdf

- Marjavaara, R. (2009). An inquiry into second-home-induced displacement. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 6(3), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530903363373

- Marjavaara, R., Müller, D. K., & Back, A. (2019). Från sommarnöjan till Airbnb: En översikt av svensk fritidshusforskning [From a summer home to Airbnb: An overview of Swedish second-home research]. In S. Wall-Reinius, & S. Cassel Heldt (Eds.), Turismen och resandets utmaningar [Tourism and the challenges of travel] (Vol. 2019, pp. 53–77). YMER. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andreas-Back/publication/332571562_Fran_sommarnojen_till_Airbnb_En_oversikt_av_svensk_fritidshusforskning/links/5cbec639299bf1209778db16/Fran-sommarnoejen-till-Airbnb-En-oeversikt-av-svensk-fritidshusforskning.pdf

- Massey, D. (1995). Places and their pasts. History Workshop Journal, 39), 182–192. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4289361

- Mosedale, J., & Voll, F. (2017). Social innovations in tourism: Social practices contributing to social development. In P. J. Sheldon, & R. Daniele (Eds.), Social entrepreneurship and tourism: Philosophy and practice (pp. 101–115). Springer International Publishing.

- Müller, D. K. (2021). 20 years of Nordic second-home tourism research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1823244

- Müller, D. K., & Hall, C. M. (2018). Second home tourism: An introduction. In M. Dieter K, & H. Michael C (Eds.), The routledge handbook of second home tourism and mobilities (pp. 1–14). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Müller, D. K., Hall, C. M., & Keen, D. (2004). Second home tourism impact, planning and management. In H. C. Michael, & M. Dieter K (Eds.), Tourism, mobility and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground (pp. 15–32). Channel View Publications.

- Natow, R. S. (2020). The use of triangulation in qualitative studies employing elite interviews. Qualitative Research, 20(2), 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794119830077

- Nordbø, I. (2014). Beyond the transfer of capital? Second-home owners as competence brokers for rural entrepreneurship and innovation. European Planning Studies, 22(8), 1641–1658. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.784608

- Nordic Council of Ministers. (2021). Monitoring the sustainability of tourism in the Nordics. https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1557946/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet [Ministry of Trade Industry and Fisheries]. (2020). Næringslivets betydning for levende og bærekraftige lokalsamfunn NOU 2020:12 [The importance of business for sustainable local communities]. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-2020-12/id2776843/

- OECD. (2021a). Managing tourism development for sustainable and inclusive recovery, OECD Tourism Papers, No. 2021/01, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/b062f603-en

- OECD. (2021b). OECD Economic Outlook (Vol. 2021). Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/edfbca02-en

- Oliveira, J. A., Roca, M. d. N., & Roca, Z. (2015). Economic effects of second homes: A case study in Portugal. Economics & Sociology, 8, 183–196. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Zoran-Roca/publication/293231139_Second_homes_and_residential_tourism_New_forms_of_housing_new_real_estate_market/links/588ef6d392851cef1363bc25/Second-homes-and-residential-tourism-New-forms-of-housing-new-real-estate-market.pdf

- Østlandsforskning [Eastern Norway Research Institute]. (2021). Kunnskapsstatus fritidsboliger i Innlandet, antall og utvikling [Knowledge bank of second homes in the Inland region, quantity and development]. Retrieved August 16, 1993, from https://www.ostforsk.no/forskningsomrader/regional-utvikling-fjellomrader/kunnskapsstatus-fritidsboliger-i-innlandet-2021/fritidsboliger-antall-og-utvikling/

- Overvåg, K., & Berg, N. G. (2011). Second homes, rurality and contested space in Eastern Norway. Tourism Geographies, 13(3), 417–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.570778

- Paris, C. (2014). Critical commentary: Second homes. Annals of Leisure Research, 17(1), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2014.890511

- Partanen, M. (2021). Social innovations for resilience – Local tourism actor perspectives in Kemi, Finland. Tourism Planning & Development, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2021.2001037

- Pedersen, A. J. (2020). Opplevelsesturismens bærekraftutfordring – Voksesmerter eller systemsvikt? [The challenges of experience tourism: Growing pains or system failure?]. Praktisk økonomi & finans [Practical Economy & Finance], 36(2), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-2871-2020-02-03

- Rye, J. F. (2011). Conflicts and contestations. Rural populations’ perspectives on the second homes phenomenon. Journal of Rural Studies, 27(3), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.03.005

- Skjeggedal, T., & Overvåg, K. (2015). Fjellbygd eller feriefjell? [Inhabited or recreational mountains?]. Fagbokforlaget, 254.

- Slätmo, E., Vestergård, L. O., Lidmo, J., & Turunen, E. (2019). Urban-rural flows from seasonal tourism and second homes – Planning challenges and strategies in the Nordics. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1372234/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Sonderegger, R., & Bätzing, W. (2014). Second homes in the alpine region. Journal of Alpine Research/Revue de géographie alpine, https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.2511

- Statistics Norway. (2017). The vast majority own their primary home. https://www.ssb.no/bygg-bolig-og-eiendom/artikler-og-publikasjoner/stort-flertall-eier-boligen

- Statistics Norway. (2021a). Median prices for new and used single-family homes. Retrieved August 17, 2023, from https://www.ssb.no/priser-og-prisindekser/boligpriser-og-boligprisindekser/artikler/dyrest-a-kjope-enebolig-i-oslo-og-baerum/tabell-1.medianpriser-for-nye-og-brukte-frittliggende-selveide-eneboliger-omsatt-i-fritt-salg-i-perioden-4.kvartal-2019-3.kvartal-2021.kommunetall

- Statistics Norway. (2021b). Norway Statistics Map Portal. Retrieved August 17, 2023, from https://kart.ssb.no/share/2013f15aa2b4

- Statistics Norway. (2022). Facts about cabins and second homes. Retrieved November 28, 2022, from https://www.ssb.no/bygg-bolig-og-eiendom/faktaside/hytter-og-ferieboliger

- Statistics Norway. (2023a). Cabins and second homes. Retrieved July 27, 2023, from https://www.ssb.no/bygg-bolig-og-eiendom/faktaside/hytter-og-ferieboliger

- Statistics Norway. (2023b). Record-breaking amount of new second homes in 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2023, from https://www.ssb.no/bygg-bolig-og-eiendom/bygg-og-anlegg/statistikk/byggeareal/artikler/rekordmange-nye-hytter-i-2022

- Statistics Norway. (2023c). Who buys second homes? https://www.ssb.no/bygg-bolig-og-eiendom/eiendom/artikler/hvem-kjoper-hytte

- Statistics Norway. (2023d). Øyer Municipality. Retrieved August 17, 2023, from https://www.ssb.no/kommunefakta/oyer

- Streimikiene, D., Svagzdiene, B., Jasinskas, E., & Simanavicius, A. (2021). Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustainable Development, 29(1), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2133

- Sullivan, L., Ryser, L., & Halseth, G. (2014). Recognizing change, recognizing rural: The new rural economy and towards a new model of rural service. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 9, 219–245. https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/1188/276

- Taylor, M. C. (2005). Interviewing. In I. Holloway (Ed.), Qualitative research in health care (pp. 39–55). Open University Press.

- Totcheva, ØC, Wegener, C., & Wilumsen, E. (2019). Social innovation as a situated practice in nursing homes. In A. K. T. Holmen, & T. Ringholm (Eds.), Innovation meets municipality (pp. 103–117). Cappelen Damm akademisk.

- United Nations. (n.d.-b). Sustainable cities and communities. Retrieved July 09, 2017, from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/?gclid=Cj0KCQjw0bunBhD9ARIsAAZl0E11OTDmPmOYb70Bxxsi4jEHZSuWB_Z89Fa39UnwSb2BPdwdy9hoJL8aAmzeEALw_wcB

- United Nations. (n.d.-c). Sustainable development goals. Retrieved March 25, 2022 from https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Ursić, S., Mišetić, R., & Mišetić, A. (2017). How to preserve landscape quality – Second home paradox. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 37, 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2017.03.025

- Velvin, J., Kvikstad, T. M., Drag, E., & Krogh, E. (2013). The impact of second home tourism on local economic development in rural areas in Norway. Tourism Economics, 19(3), 689–705. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2013.0216

- Vercher, N. (2022). The role of actors in social innovation in rural areas. Land, 11(5), 710. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11050710

- Visit Lillehammer. (2020). Markedsstrategi 2021–2025 Visit Lillehammer AS https://bransje.lillehammer.com/markedsstrategi/

- Xue, J., Næss, P., Stefansdottir, H., Steffansen, R., & Richardson, T. (2020). The hidden side of Norwegian cabin fairytale: Climate implications of multi-dwelling lifestyle. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(5), 459–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1787862