ABSTRACT

Tourism is widely recognised as a significant source of economic growth and employment, but its effects on employment in sectors beyond the traditional tourism industry is under-researched. Our study explores this research gap by examining the relationship between second-home tourism and employment in the construction industry. Using a combination of registry data and official tax records, the study explores the labour market effects of second-home owners investing in these homes. We find evidence of a positive and significant correlation between the number of second homes and the size of the construction sector within local economies. In particular, the effect stems from second homes owned by non-locals. In addition, we find striking spatial patterns of money flowing into construction firms from outside the local economy – considerable net flows of investments from urban to rural areas, from centre to periphery. This research contributes to the understanding of how tourism affects labour markets beyond the tourism industry. It emphasises the spatial aspects of second-home tourism, particularly in relation to the construction industry. The findings have implications for policymakers, planners, and tourism stakeholders, providing valuable insights into the economic significance of second-home tourism and its impact on local labour markets.

Introduction

Tourism is a growing global phenomenon, hailed as a significant source of economic growth, regional development, and employment (Gössling & Peeters, Citation2015; Hall, Citation2005; Ioannides & Zampoukos, Citation2017; UNWTO, Citation2019). Numerous studies have argued that the economics of tourism are not solely limited to the tourism industry; rather, it has been shown to “leak” and “link” to other sectors of the economy (Antonakakis et al., Citation2015; Hjalager et al., Citation2016; Lejárraga & Walkenhorst, Citation2010). However, despite the substantial body of literature on labour in tourism, the impact of leakages and linkages of tourism on the labour market remains poorly understood (e.g. Baum et al., Citation2016; Booyens, Citation2022; Cukier, Citation2002; Zampoukos & Ioannides, Citation2011). This is because the literature on tourism labour typically focusses on employment in firms that are directly involved in tourism, such as the discrete tourism and hospitality industry (e.g. Booyens, Citation2022; Lundmark, Citation2005, Citation2006; Tyrrell & Johnston, Citation2016; Veijola, Citation2010; Walmsley et al., Citation2020).

In order to address this research gap, our study aims to explore the impact tourism has on employment in a sector that is not typically defined as part of the tourism industry, namely the construction sector. Given that this sector is a crucial contributor to economic development (Fulford, Citation2018; Giang & Sui Pheng, Citation2011; Hillebrandt, Citation2000), it is vital to understand how tourism can impact construction industry employment by creating demand for the construction and maintenance of buildings and infrastructure. However, to our knowledge there are very few studies investigating how tourism contributes to the construction sector (Hall, Citation2008; Maitland & Smith, Citation2009; Yrigoy, Citation2023).

In this paper, we focus on the effect of second-home tourism on the construction industry. There are two main reasons for this. First, second-home tourism is among the most widespread forms of tourism globally (Hall, Citation2015; Hall & Müller, Citation2018; Müller & Hoogendoorn, Citation2013). In many countries, second-home tourism is an often overlooked “hidden giant” of tourism (Frost, Citation2004), since it falls outside the typical understanding of the sector (Back, Citation2020a; Boto-García & Baños Pino, Citation2024). Second, the premise for second-home tourism is multiple homes, or “multi-house homes” (Overvåg, Citation2009), with repeat visits to set locations (Sievänen et al., Citation2007). This form of tourism depends on the construction industry for building, maintaining and refurbishing houses and apartments used as second homes, and their associated infrastructure.

While previous research has touched upon the economic effects of second-home tourism, the literature is limited to case studies based on self-reported survey data from second-home owners (e.g. Bohlin, Citation1982; Czarnecki, Citation2018a; Hoogendoorn & Visser, Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2011a; Müller, Citation1999). We are instead using comprehensive microdata on employment, combined with data on housing prices, and tax deductions paid out for labour costs incurred for repairs and refurbishment on second homes, we aim to explore the labour market effects of second-home owners’ investments in their leisure properties, and the spatial patterns of these potential effects. Our geographical study area is Sweden.

The paper makes key contributions to the literature on labour, tourism and second homes. More importantly, it contributes to a novel understanding of how the economic linkages of tourism extend beyond the traditionally defined tourism industry and tourism hotspots. Furthermore, our results point to the fact that the mobility of consumers, workers, and firms – both spatial and temporal – are vital in order to understand local economies and labour markets. Given the economic importance of tourism and the construction industry, this research should also be relevant to policymakers, planners, and tourism stakeholders.

Second homes and the construction industry

The economic contribution of second-home tourism

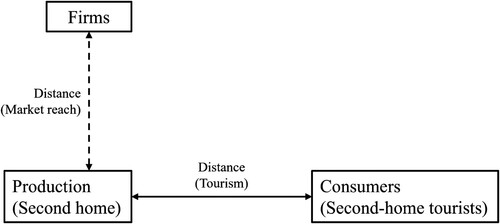

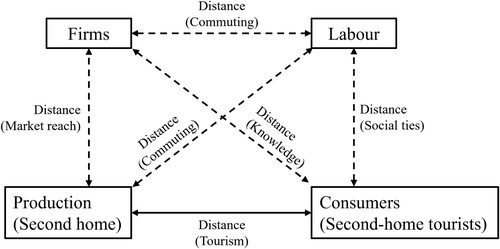

Local communities experience the social, economic, and environmental impacts of second-home tourism. Thus, understanding local perspectives on the economic value of second homes is vital (Czarnecki, Citation2018b). Research on the economic impacts of second-home tourism has focused on issues directly related to housing, such as increasing property prices, gentrification and living costs for residents (Gallent et al., Citation2016; Paris, Citation2009) but also revenue streams from home exchanges or commercial letting of second-home property (Bieger et al., Citation2007; Brunetti & Torricelli, Citation2017; Casado-Diaz et al., Citation2020; Skak & Bloze, Citation2016). In terms of economic effects on the local labour markets, most studies have focused on service-related activities such as local convenience stores, service stations, outdoor and leisure activities, but also expenditure patterns when travelling between first and second homes (e.g. Boto-García & Baños Pino, Citation2024; Larsson & Müller, Citation2019; Oliveira et al., Citation2015). This spatial relationship between the local market as a site of production (e.g. the second home) and potential influx of demand from a consumer (e.g. the second-home tourist) is visualised conceptually in .

Figure 1. Conceptual illustration of spatially projected construction demand through second-home tourism.

To summarise, economic impacts of second-home tourism are both positive and negative (Adamiak, Citation2014). They are connected to, for example, seasonality (Müller, Citation2002), and the local context of second-home destinations (e.g. Hoogendoorn et al., Citation2009; Hoogendoorn & Visser, Citation2010b, Citation2011b). Realistically, second homes are in most cases not the main form of income for rural areas. Rather, they can be beneficial as an additional stream of income to other primary income revenues (Czarnecki, Citation2014; Gallent et al., Citation2016; Larsson & Müller, Citation2019; Paris, Citation2011). However, previous research has given little attention to the impact on local labour markets, and specifically, the effects on the construction industry (Gallent et al., Citation2016; Hoogendoorn & Visser, Citation2011a, Citation2015).

Infusing tourism into construction

Regarding inquiries on tourism and the labour market, the literature has approached the topic from several strands of research, such as anthropology, management, geography, and sociology. It has highlighted, for example, tourism labour from a human resource perspective (Ladkin, Citation2011); skills required for the tourism workforce (Åberg, Citation2017); the precarity of tourism labour (Robinson et al., Citation2019); and its importance for economic development (Booyens, Citation2022; Calero & Turner, Citation2019). However, the focus in the literature is generally based on the view of tourism as an industry, meaning that the research is focused on labour, workers and employment in a discrete tourism industry (Booyens, Citation2022; Ioannides & Zampoukos, Citation2017; Müller & Ulrich, Citation2007; Veijola, Citation2010; Walmsley et al., Citation2020). This contrasts with labour in industries that experience “leakages” from tourism (Lejárraga & Walkenhorst, Citation2010), such as workers employed in the construction industry.

Apart from this direct relationship between tourism and the construction industry, the theoretical understanding of this relationship depends on the definition of “tourism”. If tourism is defined strictly as a “discrete industry”, it depends on construction being an allied or connected industry to tourism (Hall, Citation2005; Maitland & Smith, Citation2009). If tourism is instead defined as a “social phenomenon ‘infused’ throughout society”, as Müller (Citation2019) suggests, it means that tourism has more far-reaching spatial and societal impacts than merely as an “industry”. From this latter perspective, Müller (Citation2019) argues for studying tourism as part of general societal processes. This would include, for example, investigating tourism’s role in retail localisation, rural change and urban gentrification, or its impact on labour markets (Coles et al., Citation2015; Müller, Citation2019). This aligns with a theoretical understanding of tourism as spatial through its invariable connection to mobility (Butler, Citation2012; Hall, Citation2005; Hall & Page, Citation2012) and that it is difficult to define as a neatly delimited industry (Baggio, Citation2008; Smith, Citation1988). Based on this perspective, we believe the question is not whether a specific industry is a so-called “tourism industry”; rather we need to ask about the degree to which different places, parts of the economy, and the labour market are linked to, and affected by tourism. It is from this understanding that we approach second-home tourism’s impact on the construction industry.

Broadly defined, the construction industry develops infrastructure and the built environment for private or public use (Hillebrandt et al., Citation1995). As such, it is a significant economic contributor and facilitator of everyday life (Crosthwaite, Citation2000; Fulford, Citation2018). Tourism relies heavily on the construction industry to produce and maintain the built environment (Hall, Citation2008; Maitland & Smith, Citation2009; Smith, Citation1998), and in turn, tourism creates a demand for construction work through the need for e.g. new buildings as well as expanding, maintaining or changing the use of existing ones, as well as tearing down buildings (Hillebrandt, Citation2000). This interdependence underpins the economic ripple effects in the labour market from construction expenditure (Giang & Sui Pheng, Citation2011; Hillebrandt, Citation2000).

The construction industry uses heavy-weighing input materials, meaning that transport costs limit the market reach of construction firms; restricting them, by and large, to a spatially bound market (Segerstedt & Olofsson, Citation2010). The labour force might however be differently spatially restrained, which is a crucial point to which we will return later in the paper. The geographic size of that market depends on the scale of the projects. Larger firms with a broad market reach and extensive resources typically oversee large, complex projects. The opposite is true for projects that are manageable for small firms with limited geographical market reach (Hillebrandt, Citation2000). In the context of this paper, medium-sized or large construction companies could manage large-scale second-home development. At the same time, small local firms could refurbish single cottages. In short, the patterns for the spatial organisation of the construction industry depend on the size of the market, the size of the projects and the size of the firms. The market size is likely to be closely related to population density, suggesting that construction firms are more likely to be based in or close to population centres. However, in rural markets, there may be scenarios in which only a few contractors are available for a job of any size or type (Hillebrandt, Citation2000). In such areas, second-home tourism can provide business opportunities for construction firms but can also spill over into demand for permanent housing and maintenance (Back, Citation2022; García, Citation2021).

Previous studies have shown that second-home tourists invest considerably in building, maintaining and refurbishing their leisure properties, but the literature is limited to case studies based on self-reported survey data from second-home owners (e.g. Bohlin, Citation1982; Czarnecki, Citation2018a; Hoogendoorn & Visser, Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2011a; Müller, Citation1999). Indeed, Müller (Citation1999) argues that most of the economic benefits of second-home development are derived from construction. Hoogendoorn and Visser (Citation2004) and Gallent et al. (Citation2016) underline the importance of second-home owners using local construction companies for second-home development. More recent studies have found adverse effects on local employment if second-home investments are curtailed (Hilber & Schöni, Citation2020). Therefore, understanding the role of the construction industry within second-home tourism is critical in gaining a deeper and more complete understanding of how tourism is infused in the labour market.

Data and methods

Data

Studies on the economic effects of second-home tourism commonly rely on expenditure or survey data from second-home tourists. In this study, we explore the impact of second-home tourism on construction employment by combining several different datasets. While previous studies investigating the labour market effects of second-home tourism used small-scale data, such as limited surveys of second-home owners’ expenditures (e.g. Bohlin, Citation1982; Czarnecki, Citation2018a; Hoogendoorn & Visser, Citation2004; Müller, Citation1999), the investigation conducted for this paper is based entirely on detailed, national data. As such, it visualises the spatial patterns and uneven labour market effects of investments in second homes nationally. To our knowledge, this is the first study to do so.

Georeferenced microdata on construction employment

The first dataset is georeferenced employer–employee matched register data from Statistics Sweden (SCB). This data contains full annual records of all firms, establishments, and employees in the Swedish economy. This data is gathered once a year (November), and is best suitable for capturing permanent rather than seasonal work. We used the information on location (municipality) and sector of all Swedish plants (workplaces) for the period 2016–2019, as well as the number of people working at each plant during these years. Plants were included based on four-digit sector codesFootnote1 categorised by Statistics Sweden as belonging to the construction sector. However, we only included sector codes from the construction industry that could be linked to the construction and maintenance of homes (permanent or second homes), such as carpenters, plumbers, painters, electrical installations, and roofers. In the same vein, we excluded sector codes that were linked to, for example, construction of public works or infrastructure.Footnote2 For examples of previous research using similar data, see Brouder and Eriksson (Citation2013), Hane-Weijman et al. (Citation2017) and Hane-Weijman (Citation2021).

This study investigates the relative importance (concentration) of construction workers in the local labour market, rather than population dynamics. Since this study focusses on the labour market, our investigation is based on the workers’ workplaces, not their place of residency. The actual spatiality of these employment effects is naturally more complex than reflected in the dataset. We address this topic further in the Results and Discussion sections below. It must also be mentioned that the data only includes people employed in the construction industry, meaning that self-employed construction entrepreneurs are excluded from the material, unless they have registered themselves as being wage earners in their own company. As argued by Hillebrandt (Citation2000), large construction firms have large market reach, and vice versa. A possible effect from not including all self-employed is then that we run the risk of underestimating the number of local construction workers. For more information about the Swedish construction industry, see the Background section below.

Housing market data

Secondly, we used data on the prices of all detached houses sold in the open market between 2016and 2017 registered by Statistics Sweden (2019). Each sale is counted individually in the dataset, meaning that individual properties may have been sold many times during the period. Prices for each sale were aggregated to provide a median average of all properties sold at the municipal level. The regional housing prices are incorporated in order to control for confounding effects arising from regional disparities in housing markets – as affluent locales characterised by high property values may invest considerable resources in real estate development and infrastructure enhancement, potentially influencing the presence of construction workers in the region. Similar data has been used in previous studies on the long-term changes in second-home property values (e.g. Back et al., Citation2022; Hjalager et al., Citation2023).

Data on population and second homes

The third set of data used concerned municipal populations and second-home ownership in all Swedish municipalities (Statistics Sweden, Citation2020, Citation2022). The data on second homes indicate the share of second homes owned by people whose permanent residences are in another municipality. The Swedish average share of such non-local second-home ownership is 62%, but it varies wildly between different municipalities – from 14% in Malmö to 90% in Borgholm (Statistics Sweden, Citation2020). The number of second homes and population figures were used to produce per capita variables.

Tax data on construction investments in second homes

The fourth and last dataset used contains all tax deductions made for investments in permanent residences and second homes for the period 2016–2020, aggregated to the municipal level and provided by the Swedish Tax Agency (Swedish Tax Agency, Citation2021). The type of investments that were eligible are given by the deduction policy’s name, ROT, a Swedish acronym for reparation (repairs), ombyggnad (refurbishment) and tillbyggnad (extension). When eligible, taxpayers can deduct 30 per cent of labour costs incurred for such property investments, up to 50,000 SEK annually per person (Swedish Tax Agency, Citation2023). Tax deductions are explicitly given for labour costs, meaning that the sums in the dataset depicted investments directly affecting the labour market in each municipality. This provided a direct route to investigate the labour market effects sought here, rather than relying on alternative (indirect) data sources such as surveys or revenue data from construction businesses.

While the data offered fascinating opportunities in relation to this study, there were also four distinct limitations. First, ROT only applies for labour costs incurred by people paying taxes. Second, since there is an upper limit for ROT tax deductions of 50,000 SEK per person, non-deductible labour costs are excluded from the data. Third, the data only shows labour costs within the deduction scheme, and it excludes the construction of new buildings. Fourth, the data is not detailed enough for us to locate labour costs for intra-municipal investments in second homes. That is, ROT tax deductions for investments in second homes located in the same municipality as the owners’ primary homes. While it is important to keep these limitations in mind, they do not negate the research findings. The tax data was used as a proxy for the total investments in each municipality into the construction sector, connected to second-home tourism. As such, the actual investment sums were less critical to the paper than the relative sizes and spatial patterns.

Methods

Correlations between construction jobs and second-home tourism

Furthermore, the study aimed to investigate the relationship between the concentration of construction workers in the local labour market (meaning within the municipality) with the local presence of second homes. First, we constructed the variable ConstructionShare, the dependent variable, containing the rate of construction workers in the local labour market. Secondly, the main independent variable should indicate a strong or weak local presence of second homes in the municipality. This variable, SH/capita, was measured as the number of second homes (SH) as rate of the local population (capita). In addition, this variable was split into two new ones, measuring the number of second homes owned by locals and non-locals respectively, in relation to the population size of the municipality – SH/capita locals and SH/capita non-locals. We used a set of controllers that according to the literature (e.g. Hillebrandt, Citation2000) would affect the relative concentration of construction work. First, we included the municipal classification (Municipality classification), created by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (Citation2023) in order to exclude confounding effects stemming from divergent characteristics associated with varying municipality types. The classification is based on the population size, access to other urban areas and commuting patterns (see Appendix 1 for more information and a map); these are sure to exhibit distinctive socio-economic and infrastructural attributes that may significantly influence the prevalence of construction workers.

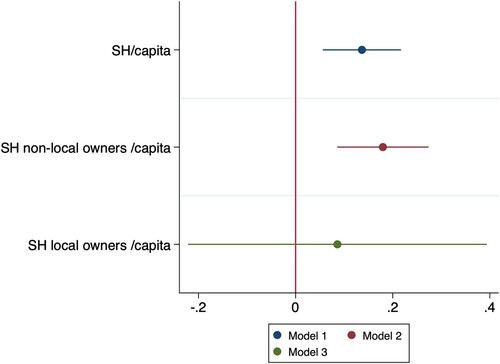

Second, we included the Average housing price in the municipality in order to control for diverse housing markets that could have an effect on the concentration of construction workers (see data section above for more details). We then ran three separate ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions with three different dependent variables, namely SH/capita (Model 1), SH/capita non-locals (Model 2) and SH/capita locals (Model 3), with the same set of control variables included in each model. After the OLS had been run the estimates from the main independent variables were stored and plotted using coefplot (Jann, Citation2014) for a better visualisation of the key result. The full models can be found in Appendix 4.

Some robustness tests were carried out.Footnote3 We ran separate regressions with absolute numbers instead of rate (Appendix 3, model1), labour market size instead of municipality classifications (Appendix 3, model 2) and included the number of building permits per capita (Appendix 3, model 3) – but the result did not change significantly (due to multicollinearity the average housing price had to be omitted in all cases).

Mapping tax deductions for second-home construction work

The dataset on ROT tax deductions for labour costs included information on all deductions based on the location of the properties (municipality) and the address of the property owners (municipality). It did not specify whether individual properties were used as permanent residences or second homes. Hence, we created a variable for determining per capita ROT deductions for second homes in each municipality. We did this by calculating the difference between the sum of ROT deductions based on the location of the properties, and the sum of ROT deductions based on the permanent address of the property owner. This was done for each municipality. In other words, if a person had received ROT deductions for a property located in another municipality than where she had her permanent residence listed, those deductions were made on labour costs for work on a second home. If a person had received ROT deductions for a property in that individual’s home municipality, we could not know if that deduction had been made for a second home or permanent residence and it was therefore not included. Thus, what we ended up with was a variable containing information about whether each municipality was a per capita net receiver or net contributor of tax deductions for labour costs made by non-locals’ across municipality borders.

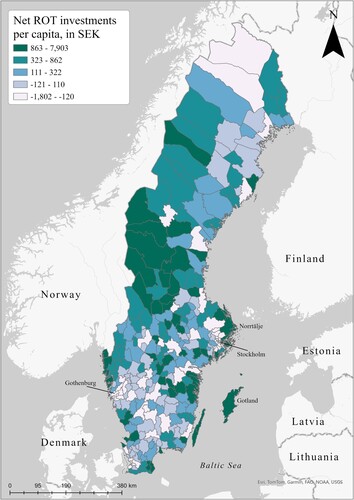

The data on tax deductions was processed using ArcGIS software to show the spatial patterns of net flows of money for second-home construction work (). Since the deductions cover 30 per cent of labour costs, the sums of tax deductions for each municipality were recalculated to show the total labour costs per capita for each municipality to give a more complete picture of the employment effects. Since the sums varied slightly over the years 2016–2020 included in the data, average sums were calculated for each municipality. The map symbology is based on quantiles. While the data range within the quantiles had an unequal distribution, it was the most nuanced way to illustrate the spatial patterns and variations. This is compared with, for example, equal intervals or natural breaks (Jenks) that would give more weight to extreme values.

Background: labour in the Swedish construction industry

The Swedish construction sector is, as in many countries, an important industry and driver of economic development (Fulford, Citation2018). It is also an arena of disparate interests, inequality, and conflict. As such, the following information is not meant to be exhaustive information about the Swedish construction sector, but rather a short and very condensed contextualisation.

As can be seen in below, a considerable share of firms in the Swedish construction sector consists of self-employed entrepreneurs, but to a lesser degree than in the economy taken as a whole. Compared to all sectors, a larger share of the construction sector consists of micro or small-sized firms employing only 1–49 workers. In total, there are more than 300,000 employees in the Swedish construction industry (Statistics Sweden, Citation2017), along with another 70,000 workers posted from other countries (Swedish Work Environment Authority, Citation2022). This latter group can be subject to grim circumstances of labour exploitation (Schoultz & Smiragina-Ingelström, Citation2023).

Table 1. Number of firms in the construction sector (SNI codes used in this study) as well as the whole economy, grouped by number of employees. Based on data from Statistics Sweden (Citation2023).

The average salary for construction workers in Sweden was 36,200 SEK per month in 2019, considerably higher than other occupations requiring high school diploma (Swedish Construction Federation, Citation2020). This is also higher than the median wage in Sweden, which was 34,200 SEK in 2022 (Statistics Sweden, Citation2023). After the introduction of the aforementioned ROT tax deductions in 2007, there are signs of decreased tax evasion connected to construction work, primarily due to changes in households’ attitudes and behaviour (Ceccato & Benson, Citation2016).

Results

Exploring the correlation between second homes and construction labour

This paper explores labour market linkages between a typical tourism activity (second-home tourism) and a traditionally non-touristic economic sector (the construction industry). Conceptually, the study aims to explore how the geographies of both production and consumption are important to understand the economy, but also that economic actors (such as second-home tourists) are mobile and can have an impact in different localities.

To begin with, we ran linear probability models (OLS) on the rate of construction workers in the local labour market (ShareConstruction) in three models (see Appendix 4 for a table of the full regressions) using three different independent variables: SH/capita (Model 1), SH/capita non-locals (Model 2), and SH/capita locals (Model 3). In , the three dots with different colours correspond to each one of these models and the position shows the coefficient for the independent variable. The line through the dot represents standard errors, that is, the accuracy with which a sample distribution represents a population by using standard deviation – a too long line means that it is not significant.

Figure 2. Plotted estimates of the main independent variables from the linear probability models (OLS) on the number of construction workers in the municipalities. Each colour corresponds to a model (Model 1, Model 2 and Model 3), and the line through the dot represents the size of standard errors.

In it is clear from Model 1 (the dot at the top) that there is a significant and positive correlation between the number of second homes per capita in a municipality and the concentration of construction workers in its local labour market. When we move on further down, even if we only consider the number of second homes in the municipality owned by non-locals – SH/capita non-locals (Model 2) there is still a significant, and a slightly bigger positive effect on the concentration of construction workers.

However, at the bottom (Model 3) we find that the significant effects disappears when we only consider second homes owned by locals. Thus, the effect of second homes on employment in construction work seems to stem from second-home owners living in a different municipality from where they have their second home. In relation to the control variables, we found no or little effect except for municipality classification, which we will return to further below. Thus, we can first deduce there seems to be a significant correlation between second-home tourism and the size of the construction labour market. Second, it becomes evident that it is crucial to incorporate mobility of people to understand their consumption behaviour and the effects on the production side. Hence, the impact from the “distance” in the conceptual visualisation back in , seems to be rather important and needs further analyses and empirical investigation. Studies that assume static local economies, not considering that consumers can be mobile, will run the risk of drawing faulty conclusions.

Mapping investments in second-home construction

The results above beg the question as to the actual scale of the effect of non-local second home ownership on the labour market for the construction industry. To address this, we used the data on ROT tax deductions from the Swedish Tax Agency (Citation2021) to calculate an estimate of the total investments for non-local second-home owners. These owners were found to be of interest in the regression in (model 3). The map in shows the spatial distribution of investments made by non-local second-home owners. The map shows the difference between tax deductions based on the taxpayers’ place of residence, and the location of the property (see the Methods section above for a more detailed description), calculated per capita, per municipality. In short, municipalities with negative values imply net outflows of money from those places. These flows are money that residents have invested in their second homes in other municipalities. Conversely, municipalities with positive values imply an inflow of money to construction work in second homes owned by people living elsewhere. As such, the map can be said to depict national inter-municipal money flows to construction firms for contracts carried out on second homes owned by non-locals. It represents a picture of actual expenditures for construction labour linked to second homes.

Figure 3. Net flow of tax-deductible investments per capita, in SEK, connected to second homes. Based on data from the Swedish Tax Agency (Citation2021).

shows a striking spatial pattern, with considerable net flows of investments from urban to rural areas, from centre to periphery. Considering the geography of Swedish second-home tourism, the municipalities with the largest inflow of money to construction labour are popular second-home destinations with a high share of non-local second home owners (Back, Citation2020b; Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017). These include the islands Öland and Gotland in the Baltic Sea, the west coast, the area around Stockholm (including its archipelago), and the mountain range bordering Norway. Although we argue that the spatial pattern rather than the actual sums is the most crucial result of , some rather fascinating examples may be highlighted. For example, Gotland is a net receiver of an average 1,776 SEK per capita, or a total of 106 million SEK.Footnote4 Norrtälje, Sweden’s second-home hotspot north of Stockholm, with roughly 26,000 second homes (Statistics Sweden, Citation2020), receives a net average of 4,062 SEK per capita, or a total of 259 million SEK (Swedish Tax Agency, Citation2021). Non-local second-home ownership is 76 per cent and 88 per cent respectively in Gotland and Norrtälje (Statistics Sweden, Citation2020). The other side of the coin is the larger cities, which are all net contributors to municipalities elsewhere. For example, Gothenburg nets an average minus 687 SEK per capita, or a total of minus 401 million SEK, whereas Stockholm nets minus 1,346 SEK per capita, or minus 1.3 billion SEK, meaning that people in these municipalities are non-local investors with second homes elsewhere, with real effects on the construction industry labour market (Swedish Tax Agency, Citation2021). The above suggests that local construction industry employment is boosted by second-home tourism, particularly in places with a relatively high degree of non-local second-home owners.

Beyond local labour market effects

To summarise, we have seen how consumers, tourists, are having a significant impact on local sites of production, second homes. In addition, apart from the local effect, we can expect that it is not only the local firms that will be affected, since firms’ market reach may stretch beyond the local economy. The market reach of construction firms of course differ, but the general pattern is that while very large construction firms can offer service to big parts of the country, smaller firms have a much smaller market reach and primarily serves local or nearby economies (Hillebrandt, Citation2000). As mentioned previously, most construction firms in Sweden are small (see ), and hence we could expect spill-over effects primarily to neighbouring municipalities, primarily those close to larger more populated municipalities. We cannot explore the mobilities of firms in detail within the scope of this paper. However, there are some interesting findings connected to the control variable of Municipality classification from our main regression (: Model 2 or full table in Appendix 4), pointing to the importance of the firms’ market reach.

If we calculate the predicted margins from each municipality category and plot them, we find an interesting geographical pattern to our correlations (see Appendix 6). It seems like Commuting municipalities near large cities (group 2) and Commuting municipalities near medium-sized towns are the types (group 4), in general, that give rise to (or are correlated with) the highest concentration of construction workers. Hence, construction firms seem to be prone to agglomerate (in relative terms), not in urban centres but at a reasonable commuting distance from them. Hence, it is not only the consumers but also producers that are spatially mobile. Firms’ market reach is affected by commuting distance or proximity and may be enough to fuel the employment level in the construction industry. This gives rise to questions about, not only the distance between the consumers and the production site, but also the firms carrying out work on, for example, second homes. Hence, we need to add the firms to our conceptual understanding and empirical framework () of local economies to acknowledge mobilities and spatialities of consumers, production sites as well as firms. Therefore, it could be reasonable to assume that in addition to the local labour market effect found in there are potential spill-over effects into nearby labour markets – depending on the characteristics of the local economy. To summarise, labour markets effects are not locally contained, since both consumers and firms are spatially mobile beyond the local economy. This is visualised in .

Discussion and concluding remarks

This paper explores the research gap connected to labour market impact of tourism outside the realms of the discrete tourism industry. We do this by investigating the effects of second-home tourism on the construction industry’s local labour markets. Since tourism is often framed as a source of employment (Åberg, Citation2017) and regional development (Calero & Turner, Citation2019), insights into the labour market effects of tourism, and its spatial patterns, are crucial. This study investigates these effects using unique national register data and provides a novel contribution to the discourse on tourism linkages and leakages to the broader economy (Antonakakis et al., Citation2015; Hjalager et al., Citation2016; Lejárraga & Walkenhorst, Citation2010). Hence, these results on the effects of tourism on labour markets should also be of interest for planners, policymakers, and tourism stakeholders. Not least since the jobs investigated in this paper are predominantly permanent, relatively well-paid, jobs rather than seasonal work. As such, this paper could form, in part, the basis for future research of this nature, in Sweden and elsewhere. We highlight a few of those themes below.

Our results differ from previous studies, which could partly be due to the novel data and perspective of this paper. While our findings suggest that second-home tourism positively impacts employment in the construction industry, such employment is contingent on local factors. In particular, the study points to effects on employment connected to whether the second-home tourists in question are locals or non-locals. While it is outside the scope of this paper to fully explain this difference, it could be because second-home owners that live in the vicinity are more likely to do construction work themselves or that locals have a network to construction workers that will make them more likely to set up an informal exchange (Nordin & Marjavaara, Citation2012). However, it could also be that non-local second-home ownership is a sign for something else. Since non-local second home ownership in Sweden is more prevalent in attractive second-home locations (Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017), these results could also be a sign that it is economically rational to invest in second homes in attractive locations, meaning that such places are more likely to experience second-home tourism related contributions to the local construction labour market.

According to previous research, attractive second-home amenities in rural areas are associated with a competitive housing market (Back et al., Citation2022; Hjalager et al., Citation2023) and a relatively high degree of non-local second-home owners (Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017). This could mean that second-home owners’ investment decisions are linked to property values (García, Citation2021). Therefore, the results from this study is contrary to previous studies on the expenditures of second-home tourists that have pointed to their low impact (Boto-García & Baños Pino, Citation2024) or to studies that saw no difference in expenditures connected to the distance between permanent residences and second homes (Velvin et al., Citation2013). However, research on the economic contribution of second-home tourism have been prone to focus on expenditures in consumer goods and hospitality services. Since this paper investigates a different service to previous studies, it could suggest that second-home tourists have consumption patterns that differ from those of other tourists.

The initial focus of this paper was the local labour market effects, but our results point to the mobility, not only of second-home tourists, but also of construction firms and workers. The spatial distribution of construction jobs does not correlate fully with population density or second homes, meaning that the paper highlights one of the many parallel processes and the uneven socio-economic geography that impact the spatial distribution of construction firms and labour demand. A probable explanation for this is that the market reach of firms and mobility of workers are not confined within municipal borders. While this follows economic theory on the market reach of construction firms (Hillebrandt, Citation2000), it also indicates the possible mobility of construction firms and workers which, to our knowledge, has not been explored in previous literature. Construction firms and workers can be based in one municipality and get contracts or jobs in another, meaning that, for example, a municipality with a high number of second homes could be a source of employment for workers in a wider regional, national, or even international labour market.

While our paper is the first of its kind to investigate the employment effects of second-home tourism, that extends beyond the tourism industry into other parts of the economy, future research could deepen the knowledge of the effects of firm and labour mobility to grasp the spatial patterns of employment impacts to an even better degree. We argue that this paper shows that it would be fruitful to similar connection between tourism and other sectors of the economy. Another productive way forward would be to proverbially “follow the money”, by investigating where and how money flows within and between places, sectors, and economic activities. In this case, the transfer of economic value is channelled through tourism, labour commuting, and through the market reach of firms. Furthermore, we argue for the significance of considering geography – not only localities, but also distance or proximity – and the mobilities of different actors, in order to understand how knowledge and social ties connect consumers and firms, and to grasp localisation strategies and contracting decisions. This concluding perspective is illustrated conceptually in .

Figure 5. Conceptual illustration of spatial relationships between the actors studied in this paper, inviting to possible further research.

To summarise, this paper addresses the need for interdisciplinary studies on second-home ownership. The paper straddles disciplinary focus areas such as economic theory, economic geography, and tourism research by considering the “infused” nature of tourism beyond a discrete tourism industry (Müller, Citation2019). This exploratory study is a modest attempt at trying to understand the dynamic relationship between consumers, producers, and labour. Moreover, we highlight that these actors and their activities are not spatially static. We encourage more research that aims to connect these actors and the full scope of their mobility. We think that a productive way to do that is to merge insights from different disciplines, such as tourism, economic geography, economics, and political economy. Furthermore, we argue for the need of place-sensitive policymaking, that not only take local variations and specificities into consideration, but also the flows and mobility of resources, investments, and people.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.1 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the journal editors and acknowledge the work of the anonymous referees. We would also like to thank Lyn Brown for language editing. Furthermore, we are particularly grateful to an unusually friendly taxi driver and construction-firm owner in Jokkmokk, northern Sweden, who unintentionally sparked the idea for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Swedish Standard Industrial Classification (SNI) based on the European classification NACE.

2 All included SNI codes are: 4110, 4120, 4321, 4322, 4331, 4332, 4333, 4334, 4391.

3 Correlation table can be found in Appendix 2.

4 At the time of writing, 1 SEK = 0.09 EUR.

References

- Åberg, K. (2017). Anyone could do that. Nordic perspectives on competence in tourism [PhD, Umeå University, Umeå].

- Adamiak, C. (2014). Importance of second homes for local economy of a rural tourism region. Conference Proceedings of International Antalya Hospitality Tourism and Travel Research Conference. Antalya, Turkey.

- Antonakakis, N., Dragouni, M., & Filis, G. (2015). How strong is the linkage between tourism and economic growth in Europe? Economic Modelling, 44, 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2014.10.018

- Back, A. (2020a). Footprints of an invisible population. Second-home tourism and its heterogeneous impacts on municipal planning and housing markets in Sweden [PhD, Umeå University, Umeå].

- Back, A. (2020b). Temporary resident evil? Managing diverse impacts of second-home tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(11), 1328–1342. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1622656

- Back, A. (2022). Endemic and diverse: Planning perspectives on second-home tourism’s heterogeneous impact on Swedish housing markets. Housing, Theory and Society, 39(3), 317–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2021.1944906

- Back, A., & Marjavaara, R. (2017). Mapping an invisible population: The uneven geography of second-home tourism. Tourism Geographies, 19(4), 595–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1331260

- Back, A., Marjavaara, R., & Müller, D. K. (2022). The invisible hand of an invisible population: Dynamics and heterogeneity of second-home housing markets. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(4), 536–549. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2520

- Baggio, R. (2008). Symptoms of complexity in a tourism system. Tourism Analysis, 13(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354208784548797

- Baum, T., Kralj, A., Robinson, R. N. S., & Solnet, D. J. (2016). Tourism workforce research: A review, taxonomy and agenda. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.04.003

- Bieger, T., Beritelli, P., & Weinert, R. (2007). Understanding second home owners who do not rent – Insights on the proprietors of self-catered accommodation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26(2), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2006.10.011

- Bohlin, M. (1982). Spatial economics of second homes. A review of a Canadian and a Swedish case study [PhD, Uppsala University, Uppsala].

- Booyens, I. (2022). Tourism’s development impacts: An appraisal of workplace issues, labour and human development. In A. Stoffelen, & D. Ioannides (Eds.), Handbook of tourism impacts: Social and environmental perspectives (pp. 197–211). Elgar.

- Boto-García, D., & Baños Pino, J. F. (2024). The economics of second-home tourism: Are there expenditure reallocation effects from accommodation savings? Tourism Economics, 30(4), 969–995. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548166231177555

- Brouder, P., & Eriksson, R. H. (2013). Staying power: What influences micro-firm survival in tourism? Tourism Geographies, 15(1), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.647326

- Brunetti, M., & Torricelli, C. (2017). Second homes in Italy: Every household’s dream or (un)profitable investments? Housing Studies, 32(2), 168–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2016.1181720

- Butler, R. W. (2012). Tourism geographies or geographies of tourism. Where the bloody hell are we? In J. Wilson (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of tourism geographies (pp. 26–34). Routledge.

- Calero, C., & Turner, L. W. (2019). Regional economic development and tourism: A literature review to highlight future directions for regional tourism research. Tourism Economics, 26(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816619881244

- Casado-Diaz, M. A., Casado-Díaz, A. B., & Hoogendoorn, G. (2020). The home exchange phenomenon in the sharing economy: A research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(3), 268–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2019.1708455

- Ceccato, V., & Benson, M. L. (2016). Tax evasion in Sweden 2002–2013: Interpreting changes in the rot/rut deduction system and predicting future trends. Crime, Law and Social Change, 66(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-016-9621-y

- Coles, T., Hall, C. M., & Duval, D. T. (2015). Mobilizing tourism: A post-disciplinary critique. Tourism Recreation Research, 30(2), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2005.11081471

- Crosthwaite, D. (2000). The global construction market: A cross-sectional analysis. Construction Management and Economics, 18(5), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/014461900407428

- Cukier, J. (2002). Tourism employment issues in developing countries: Examples from Indonesia. In R. Sharpley, & D. J. Telfer (Eds.), Tourism and development. Concepts and issues (pp. 165–201). Channel View.

- Czarnecki, A. (2014). Economically detached? Second home owners and the local community in Poland. Tourism Review International, 18(3), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427214X14101901317110

- Czarnecki, A. (2018a). Going local? Linking and integrating second-home owners with the community’s economy. Peter Lang.

- Czarnecki, A. (2018b). Uncertain benefits. How second home tourism impacts community economy. In C. M. Hall, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second home tourism and mobilities (pp. 122–133). Routledge.

- Frost, W. (2004). A hidden giant: Second homes and coastal tourism in South-Eastern Australia. In C. M. Hall, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Tourism, mobility and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground (pp. 162–173). Channel View.

- Fulford, R. G. (2018). The implications of the construction industry to national wealth. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 26(5), 779–793. https://doi.org/10.1108/ecam-03-2018-0091

- Gallent, N., Mace, A., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2016). Second homes: European perspectives and UK policies. Routledge.

- García, D. I. (2021). Second-home buying and the housing boom and bust. Real Estate Economics, 50(1), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6229.12343

- Giang, D. T. H., & Sui Pheng, L. (2011). Role of construction in economic development: Review of key concepts in the past 40 years. Habitat International, 35(1), 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.06.003

- Gössling, S., & Peeters, P. (2015). Assessing tourism’s global environmental impact 1900–2050. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(5), 639–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1008500

- Hall, C. M. (2005). Tourism: Rethinking the social science of mobility. Pearson Education.

- Hall, C. M. (2008). Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationships (2nd ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hall, C. M. (2015). Second homes planning, policy and governance. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2014.964251

- Hall, C. M., & Müller, D. K. (Eds.). (2018). The Routledge handbook of second home tourism and mobilities. Routledge.

- Hall, C. M., & Page, S. J. (2012). From the geography of tourism to geographies of tourism. In J. Wilson (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of tourism geographies (pp. 9–25). Routledge.

- Hane-Weijman, E. (2021). Skill matching and mismatching: Labour market trajectories of redundant manufacturing workers. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 103(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2021.1884497

- Hane-Weijman, E., Eriksson, R. H., & Henning, M. (2017). Returning to work: Regional determinants of re-employment after major redundancies. Regional Studies, 52(6), 768–780. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1395006

- Hilber, C. A. L., & Schöni, O. (2020). On the economic impacts of constraining second home investments. Journal of Urban Economics, 118, 103266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2020.103266

- Hillebrandt, P. M. (2000). Economic theory and the construction industry (3rd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hillebrandt, P. M., Cannon, J., & Lansley, P. (1995). The construction company in and out of recession. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hjalager, A.-M., Tervo-Kankare, K., & Tuohino, A. (2016). Tourism value chains revisited and applied to rural well-being tourism. Tourism Planning & Development, 13(4), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2015.1133449

- Hjalager, A.-M., Tophøj Sørensen, M., Nedergård Steffansen, R., & Kloster Staunstrup, J. (2023). Sales prices, social rigidity and the second home property market. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 38, 2325–2344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-023-10047-9

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2004). Second homes and small-town (re)development: The case of Clarens. Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences, 32(1), 105–115.

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2010a). The economic impact of second home development in small-town South Africa. Tourism Recreation Research, 35(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2010.11081619

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2010b). The role of second homes in local economic development in five small South African towns. Development Southern Africa, 27(4), 547–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835x.2010.508585

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2011a). Economic development through second home development: Evidence from South Africa. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 102(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2011.00663.x

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2011b). Tourism, second homes, and an emerging South African postproductivist countryside. Tourism Review International, 15(1), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427211(13139345020651

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2015). Focusing on the ‘blessing’ and not the ‘curse’ of second homes: Notes from South Africa. Area, 47(2), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12156

- Hoogendoorn, G., Visser, G., & Marais, L. (2009). Changing countrysides, changing villages: Second homes in Rhodes, South Africa. South African Geographical Journal, 91(2), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2009.9725334

- Ioannides, D., & Zampoukos, K. (2017). Tourism’s labour geographies: Bringing tourism into work and work into tourism. Tourism Geographies, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1409261

- Jann, B. (2014). Plotting regression coefficients and other estimates. The Stata Journal, 14(4), 708–737. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1401400402

- Ladkin, A. (2011). Exploring tourism labor. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 1135–1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.010

- Larsson, L., & Müller, D. K. (2019). Coping with second home tourism: Responses and strategies of private and public service providers in Western Sweden. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(16), 1958–1974. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1411339

- Lejárraga, I., & Walkenhorst, P. (2010). On linkages and leakages: Measuring the secondary effects of tourism. Applied Economics Letters, 17(5), 417–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504850701765127

- Lundmark, L. (2005). Economic restructuring into tourism in the Swedish mountain range. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 5(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250510014273

- Lundmark, L. (2006). Mobility, migration and seasonal tourism employment: Evidence from Swedish mountain municipalities. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 6(3), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250600866282

- Maitland, R., & Smith, A. (2009). Tourism and the aesthetics of the built environment. In J. Tribe (Ed.), Philosophical issues in tourism (pp. 171–190). Channel View.

- Müller, D. K. (1999). German second home owners in the Swedish countryside [PhD, Umeå. University].

- Müller, D. K. (2002). Second home ownership and sustainable development in Northern Sweden. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(4), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/146735840200300406

- Müller, D. K. (2019). Infusing tourism geographies. In D. K. Müller (Ed.), A research agenda for tourism geographies (pp. 60–70). Elgar.

- Müller, D. K., & Hoogendoorn, G. (2013). Second homes: Curse or blessing? A review 36 years later. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 13(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2013.860306

- Müller, D. K., & Ulrich, P. (2007). Tourism development and rural labour market in Sweden, 1960–1999. In D. K. Müller, & B. Jansson (Eds.), Tourism in peripheries: Perspectives from the far north and south (pp. 85–105). CABI.

- Nordin, U., & Marjavaara, R. (2012). The local non-locals: Second home owners associational engagement in Sweden. Tourism, 60(3), 293–305.

- Oliveira, J. A. D., Roca, M. d. N. O., & Roca, Z. (2015). Economic effects of second homes: A case study in Portugal. Economics & Sociology, 8(3), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789x.2015/8-3/14

- Overvåg, K. (2009). Second homes in Eastern Norway: From marginal land to commodity [PhD, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim].

- Paris, C. (2009). Re-positioning second homes within housing studies: Household investment, gentrification, multiple residence, mobility and hyper-consumption. Housing, Theory and Society, 26(4), 292–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090802300392

- Paris, C. (2011). Affluence, mobility and second home ownership. Routledge.

- Robinson, R. N. S., Martins, A., Solnet, D., & Baum, T. (2019). Sustaining precarity: Critically examining tourism and employment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1008–1025. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1538230

- Schoultz, I., & Smiragina-Ingelström, P. (2023). Access to justice and social rights for victims of trafficking and labour exploitation in Sweden. In S. Piilgaard Porner Nielsen, & O. Hammerslev (Eds.), Transformations of European welfare states and social rights. Regulation, professionals, and citizens (pp. 147–167). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Segerstedt, A., & Olofsson, T. (2010). Supply chains in the construction industry. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 15(5), 347–353. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598541011068260

- Sievänen, T., Pouta, E., & Neuvonen, M. (2007). recreational home users – Potential clients for countryside tourism? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(3), 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701300207

- Skak, M., & Bloze, G. (2016). Owning and letting of second homes: What are the drivers? Insights from Denmark. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32(4), 693–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-016-9531-4

- Smith, S. L. J. (1988). Defining tourism. A supply-side view. Annals of Tourism Research, 15(2), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90081-3

- Smith, S. L. J. (1998). Tourism as an industry. In D. Ioannides, & K. G. Debbage (Eds.), The economic geography of the tourist industry (pp. 31–52). Routledge.

- Statistics Sweden. (2017). Över 300 000 anställda i byggindustrin [Over 300,000 employed in the construction industry]. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/arbetsmarknad/sysselsattning-forvarvsarbete-och-arbetstider/kortperiodisk-sysselsattningsstatistik-ks/pong/statistiknyhet/sysselsattning-lediga-jobb-och-lonesummor-4e-kvartalet-2016/

- Statistics Sweden. (2020). Statistik om fritidshus i svenska kommuner [data on second homes in Swedish municipalities]. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/redaktionellt/hundratusentals-svenskar-ager-fritidshus-i-andra-kommuner/

- Statistics Sweden. (2022). Kommuner i siffror. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/kommuner-i-siffror/

- Statistics Sweden. (2023). Medianlöner i Sverige [Median salaries in Sweden].

- Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. (2023). Kommungruppsindelning 2023 [Classification of Swedish muncipalities 2023]. https://skr.se/skr/tjanster/kommunerochregioner/faktakommunerochregioner/kommungruppsindelning.2051.html

- Swedish Construction Federation. (2020). Lönestatistik för byggnadsarbetare 2020 [Salary statistics for construction workers 2020].

- Swedish Tax Agency. (2021). Statistical data on all ROT tax deductions for investments in primary residences and second homes in Sweden, 2009–2020.

- Swedish Tax Agency. (2023). Så fungerar rotavdraget [This is how the rot deduction works]. https://www.skatteverket.se/privat/fastigheterochbostad/rotarbeteochrutarbete/safungerarrotavdraget.4.5947400c11f47f7f9dd80004014.html

- Swedish Work Environment Authority. (2022). Helårsrapport 2022. Register för företag som utstationerar arbetstagare i Sverige [Annual report 2022. Registry for firms posting workers in Sweden]. Arbetsmiljöverket.

- Tyrrell, T. J., & Johnston, R. J. (2016). The economic impacts of tourism: A special issue. Journal of Travel Research, 45(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287506288876

- UNWTO. (2019). International tourism highlights, 2019 edition (report no. 9789284421152).

- Veijola, S. (2010). Introduction: Tourism as work. Tourist Studies, 9(2), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797609360748

- Velvin, J., Kvikstad, T. M., Drag, E., & Krogh, E. (2013). The impact of second home tourism on local economic development in rural areas in Norway. Tourism Economics, 19(3), 689–705. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2013.0216

- Walmsley, A., Åberg, K., Blinnika, P., & Jóhannesson, G. T. (Eds.). (2020). Tourism employment in Nordic countries. Trends, practices, and opportunities. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Yrigoy, I. (2023). Strengthening the political economy of tourism: Profits, rents and finance. Tourism Geographies, 25(2-3), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2021.1894227

- Zampoukos, K., & Ioannides, D. (2011). The tourism labour conundrum: Agenda for new research in the geography of hospitality workers. Hospitality & Society, 1(1), 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1386/hosp.1.1.25_1

Appendices

Appendix 1. Map of municipality classification done by Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (Citation2023), legend altered by authors.

Appendix 2. Correlation matrix

Appendix 3. Linear probability models (OLS) on the number of construction workers in the local labour market (NrConstruction) in Model 1, and share of construction workers (ShareConstruction) in Model 2 and Model 3.

Appendix 4. Linear probability models (OLS), all on the rate of construction workers in the local labour market (dependent variable = ShareConstruction) in three models using three different main independent variables: SH/capita (Model 1), SH non-local owners/capita (Model 2), and SH local owners/capita (Model 3).

Appendix 5: Linear probability models (OLS) on the rate of construction workers in the local labour market (ShareConstruction) from number of second homes owned by non-locals (SH non-local owners/capita), done step-wise from Model 1 to Model 3.

Appendix 6. Calculated and plotted predicted margins from variable Municipality category from regression in Appendix 4, Model 2.