ABSTRACT

Major sporting events (MSEs) have been used by governments to improve the image of cities and nations, and to attract tourists. In the wake of criticism of how global MSEs handle human-rights issues, governments are pressured to rethink how these events are organised and branded. Developing and employing an analytical framework based on inclusive place branding and pathways to progressive human-rights outcomes, this study explores how and to whom inclusiveness is communicated in five Olympic Games candidate files. A quantitative content analysis is performed using keywords related to inclusiveness and three characteristics of inclusiveness are analysed qualitatively: democratic representation, inclusive participation, and committed transformation. The findings show that three of the candidate files predominantly belong to the traditional place branding paradigm through their focus on external stakeholders, while two have adopted a more inclusive place branding strategy and put emphasis on internal stakeholders. The analytical framework introduced in this study can be useful for both researchers and practitioners – such as prospective hosts of MSEs and other events – as a conceptual tool to analyse and develop inclusiveness in major events.

Introduction

Governments of all political hues often use major sporting events (MSEs) for place branding and tourism development, to improve a city’s or a nation’s image, credibility and economic competitiveness and to exercise agency on an international stage (Grix & Lee, Citation2013; Kolotouchkina, Citation2018). Place branding has been defined as the creation of a desirable image of a place (or destination) through various methods and activities (Kavaratzis & Ashworth, Citation2006) such as major events. Global events, also referred to as mega-events with global reach, high levels of value creation, create opportunities for international visibility and relevance (Kolotouchkina, Citation2018) and possibilities to draw attention and tourism revenue to a place (Ooi, Citation2011). Historically, gaining attention and visibility has been the main motivation to bid for and host, for example, the Olympic Games and World Cups (Knott et al., Citation2016). However, MSEs have received massive criticism of various aspects, such as overspending and corruption (Knott et al., Citation2017), the exclusion of local stakeholders (Kennelly, Citation2017) and general human-rights issues (Horne, Citation2018).

The current study focuses on inclusion in the context of MSEs, which can be seen as one possible pathway to counteract human-rights violations such as forced evictions (Suzuki et al., Citation2018; Talbot & Carter, Citation2018), labour-rights abuse (Millward, Citation2017), and discrimination. Other negative impacts, such as neglecting socially excluded groups in planning for the legacies of MSEs (Minnaert, Citation2012), could also be addressed using an inclusive process. Inclusiveness or inclusion can be related to the concept and debate of social inclusion in the 1980s, as a response to social exclusion (Laing & Mair, Citation2015). In this study, we adhere to this stream of thought and the core of inclusion being the right for citizens to participate in fundamental social, cultural, economic, and political activities in society (Burchardt et al., Citation2002; Laing & Mair, Citation2015).

There is limited research exploring how inclusiveness, in relation to place branding, plays out in the context of MSEs, despite the critique directed at large events in recent decades. In fact, while some studies have covered the process of citizen involvement and the policies and principles of social inclusion in events (e.g. Hereźniak & Florek, Citation2018), research exploring how inclusion is addressed in relation to MSEs is scarce. The term inclusiveness which, for example, covers the social process of citizen involvement, has been studied in the context of events (e.g. Kolotouchkina, Citation2018) and in relation to policies and principles of social inclusion in preparing for the Olympic Games (e.g. Vanwynsberghe et al., Citation2013). The latter study criticises the narrow view on (social) inclusion by organisers and call for more scrutiny and evaluation of inclusion policies of MSEs.

The objective of this study is to explore the varying practices of how and to whom inclusiveness is communicated in five Olympic Games candidate files. The candidate file is one way (other ways could include e.g. ad campaigns, news coverage, or the execution of the event) – for a city or nation bidding to host the Olympics – to communicate a desirable image and vision of a place to both external stakeholders (e.g. the IOC, presumptive tourists, and international media) and internal stakeholders (e.g. local politicians and local community actors). This study responds to the call for more research on inclusion policies of MSEs (Vanwynsberghe et al., Citation2013) and considers the candidate files as place branding documents and valuable examples of written documents where inclusion policies could be probed and questioned. Hiller and Wanner (Citation2018) in fact show that locals’ participation in event-related activities leads to more positive evaluation of the event, and that proactive potential organisers of MSEs would benefit from including the local public already at the bidding phase.

We bring together the pathways for creating progressive human-rights outcomes as outlined by McGillivray et al. (Citation2019), characteristics of inclusive place branding as conceptualised by Jernsand (Citation2016) as well as critical perspectives on democracy and participation in the context of place branding (Jernsand & Kraff, Citation2017) in an analytical framework to understand how and to whom inclusiveness is communicated in the candidate files. Examining Olympic Games candidate files, we explore the following two research questions:

How is inclusiveness communicated in Olympic candidate files?

To whom is inclusiveness communicated in Olympic candidate files?

This analytical framework is a contribution to practice, as a tool for policy makers and the industry to work with inclusive place branding, and to research, as a definition and method to analyse inclusiveness in the context of large events and place development.

We treat inclusiveness as one of the fundamental aspects in addressing human-rights issues and pay attention to how (if at all) and to whom (if specified) it is communicated in the Olympic candidate files. The candidate file is the outcome of a bidding process and a steppingstone for planning and delivering the positive social outcomes of MSEs. It is, in fact, the most crucial document highlighting good governance, enforcement, and monitoring by right-holders (e.g. FIFA, IOC) and concerned stakeholders (local and national governments, NGOs, etc.) (McGillivray et al., Citation2019). Countries hosting the Olympics could be held accountable for their practices on human-rights and inclusiveness through complying with the candidate file. With this said, there is by no means a perfect positive correlation between what is communicated in the candidate file and what is followed through in practice (McGillivray et al., Citation2019).

We explore, in relation to the research questions, how the candidate files address stakeholders in(side) a place, e.g. current residents, local companies, and decision-makers (from here on internal stakeholders) and stakeholders outside a place – e.g. international companies, tourists, other nations, and potential future residents (from here on external stakeholders) and how this may affect the way in which inclusiveness is expressed. By focusing on similarities and differences in how inclusiveness is addressed in different candidate files (cf. Grix & Lee, Citation2013), we address the importance of making visible the diversity of the context in the Olympics bidding documents, as a step towards achieving progressive human-rights outcomes through MSEs. For consistency we will refer to the Summer and Winter Olympics as major sporting events (MSEs), even if the term mega-event often is used for the Summer Olympic Games, but not always for the Winter Olympic Games which are smaller in size and reach (Schulenkorf et al., Citation2024; Wickey-Byrd et al., Citation2023).

Major sports events (MSEs), human rights and inclusion

Sports and sports events have historically been championed as arenas for inclusion due to, for example, their ability to create the wide participation of groups from all layers of society and to convey positively charged values such as non-discrimination and solidarity (Shi & Bairner, Citation2022). This is depicted in the Olympic values (e.g. excellence, friendship, and respect) as well as by sports federations and authorities. Considering the public and academic critique of MSEs as being exclusionary (e.g. by reinforcing existing problems with housing and transport for residents), corrupt, and violating human rights, the existence of large events (in their current form) has been questioned and debated (e.g. Gaffney, Citation2016; McGillivray et al., Citation2019). To respond to the critique towards unsustainable practices, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) launched the Agenda 2020 reform to create more transparent and inclusive Games (IOC, Citation2014). This was followed up by the Agenda 2020+5 in 2021 (IOC, Citation2021). The agendas explicitly include efforts on human rights – e.g. media freedom, freedom of expression, solidarity, and non-discrimination (IOC, 2021; MacAloon, Citation2017). There are other initiatives taken by the IOC to encourage the Olympic movement to work towards solving human-rights-related issues: Since the early 2000s, the IOC began to require host cities to undertake initiatives to ensure local social inclusion of for example women, youth, and indigenous people and the Olympic Agenda 21 sets clear goals to strengthen the inclusion of women, youth and indigenous people in the Games (Holden et al., Citation2008; Vanwynsberghe et al., Citation2013).

In understanding MSEs, human rights and inclusion, it is necessary to address the role of MSE for public diplomacy (e.g. Zhou et al., Citation2013), cultural diplomacy (e.g. Ndlovu, Citation2010), soft power (e.g. Abdi et al., Citation2019; Grix & Houlihan, Citation2014), and international relations (e.g. Grix & Brannagan, Citation2016). MSE’s focus have shifted from primarily communicating with external stakeholders to turning the emphasis on internal stakeholders (e.g. Yang, Citation2020) due to the critique related to human-rights issues. Butler and Aicher (Citation2015), for example, examine how the international media covered the protests leading up to the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil as an example of efforts targeted at external stakeholders being disrupted by activities (e.g. protests) by local stakeholders – if social injustices and human-rights issues are not dealt with through, for example, policy interventions.

MSEs as platforms for place branding

Major sporting events (MSEs) have been used by governments as domestic politics, which aims to foster national identity-building and collective pride. The use of MSEs for these purposes is facilitated by the fact that sports communicate universal values that are often recognised and shared by many (Grix & Lee, Citation2013). MSE are also used to improve or change the image of cities and nations (Abdi et al., Citation2019; Duignan, Citation2021; Schulenkorf et al., Citation2024) and therefore contribute to cities and nations’ place branding. Place branding is the established concept when discussing the branding of nations, cities, regions, destinations, and other places (e.g. Hanna & Rowley, Citation2008; Lucarelli & Olof Berg, Citation2011). Place branding is a process which includes various activities, methods, and stakeholders with the aim of creating a desirable image of a place (Kavaratzis & Ashworth, Citation2006). Place branding primarily largely focused on external stakeholders with the central aim to attract investors, tourists, or residents to a place (e.g. Björner, Citation2017; Lucarelli, Citation2015). However, in the last decades, a more responsible development of place branding has been called for where concepts like inclusive place branding have evolved. Based on Jernsand (Citation2016), inclusive place branding can be defined as “the facilitation of a social process of interaction between place stakeholders, with the aim of building sustainable place brand equity” (p. 14).

Agenda 2020 influences hosting states to communicate shared, universal Olympic values and a collectively recognised identity on the international stage, thus showcasing “sameness” with other nations (Grix & Lee, Citation2013). At the same time, hosting states are interested in communicating their “uniqueness” and engage in place branding (Chan et al., Citation2016). Indeed, this competing idea of sameness and uniqueness is central in place branding, that uniqueness has been put forward as central in standing out in the competition (Richelieu, Citation2018) while the pursuit for uniqueness leads to the sameness of the place (Berg & Björner, Citation2014). Moreover, there are complex interplay of selling a single identity or the multiplicity and diversity of places (Ren & Stilling Blichfeldt, Citation2011). Place branding always entails processes of inclusion and exclusion; therefore scholars also point to the impossibility of “inclusive” place branding (Ulver & Osanami Törngren, Citation2023).

Theoretical framework

Our study builds on Jernsand’s (Citation2016) characteristics of inclusive place branding, Jernsand and Kraff’s (Citation2017) discussion of democracy and participation in place branding, and McGillivray et al. (Citation2019) conceptualisation of progressive human-rights outcomes in major sporting events.

Inclusive place branding stems from the criticism of traditional place branding and the calls for including multiple stakeholders of the place (see Braun et al., Citation2013; Lucarelli, Citation2012) as well as knowledge from a wider range of academic disciplines in the work with place branding (see Zenker & Govers, Citation2016). We focus on four of the five characteristics of inclusive place branding proposed by Jernsand (Citation2016); democracy, participation, transformation, and multiplicity. The italicised words in the definitions below are keywords which captures aspects of inclusive place branding. The keywords are the basis for the proposed analytical framework (see next section and ).

Table 1. Keywords for analytical framework and word count for each candidate file.

Democracy should be understood in the sense that “local communities should be empowered to take part in the process of place development and branding” (p. 20). McGillivray et al. (Citation2019), in line with Jernsand, also propose that progressive human-rights outcomes in MSEs require that organisers and hosts open the governance of the MSE to various key actors, especially those representing vulnerable and excluded populations. Main components of a democratic process include transparency, stakeholder engagement and fair representation, as well as responsiveness and accountability. This connects to the importance of local communities being represented in the development and branding of a place, highlighting participation, interaction, inclusion, involvement, and inviting and informing the local community and citizens. The non-avoidance of controversial issues and active efforts for empowerment are also necessary for democracy (Jernsand, Citation2016; Jernsand & Kraff, Citation2017).

Participation of a variety of stakeholders in decision making related to place branding, in particular residents and communities (Jernsand, Citation2016; Kavaratzis & Kalandides, Citation2015) is a direct practice of democracy which could help to protect and promote human rights (McGillivray et al., Citation2019). Without democracy, participation would not be possible. The participatory process needs to build on inclusiveness and the representation of different groups, i.e. a pluralistic representation (Jernsand & Kraff, Citation2017; McGillivray et al., Citation2019). Participation requires interaction and dialogue with mutual respect and emotional engagement (Jernsand, Citation2016; Jernsand & Kraff, Citation2017). When democracy and participation are reflected in the place branding processes, knowledge integration, empowerment, relationship-building, and co-creation emerge and lead to transformation (Jernsand, Citation2016).

Transformation resonates with the pathways of McGillivray et al. (Citation2019): good governance, democratic participation, formalisation of human rights agendas, and sensitive urban development – as the steps suggested to create change and progressive social outcomes. Transformation requires embedding and implementing plans, and committing to plans and making these visible in written documents (such as the candidate files analysed in this study). This would raise the levels of responsiveness, accountability, and transparency. Documenting transformation makes it possible to properly monitor the outcomes, which leads to not only good governance but also empowerment of formerly excluded groups (McGillivray et al., Citation2019).

Lastly, multiplicity will only emerge if participatory processes are democratic and transformative (Jernsand & Kraff, Citation2017). Multiplicity stresses the inclusion of multiple identities and contexts of a place as well as multiple approaches to place branding (Jernsand, Citation2016).

The risk of stressing multiple identities and diversity is that the place might be perceived as incoherent and chaotic; however, expressions of multiple identities contribute to a more authentic picture of the place and the inclusion of marginalised groups (Jernsand & Kraff, Citation2017). When representation is insufficient, conflicts may arise between groups of people (Jernsand, Citation2016).

Jernsand also discusses a fifth characteristic, an evolutionary process, which we recognise as a crucial aspect of inclusive place branding; however, do not incorporate in our analysis. Inclusive place branding is, according to Jernsand (Citation2016), an evolutionary process characterised by the four aspects that we focus on in this study. A place branding process should not be static or linear, but in constant movement reflecting the place (Jernsand, Citation2016). To conduct an analysis of the evolutionary process, it is necessary to engage in the processes leading up to, and follow, the authoring of the candidate files, which is outside the scope of this study. This is a process that takes several years for MSEs and our analysis is limited to the end products (the candidate files) through which the bidding hosts communicate inclusiveness (or not) to internal and external stakeholders.

Analytical framework for our analysis

The suggested keywords (see ), based on the work by McGillivray et al. (Citation2019), Jernsand (Citation2016), and Jernsand and Kraff (Citation2017), should not be understood as mutually exclusive for each characteristic of inclusive place branding described above, but rather as elements that may reflect the commitment to inclusion which is visibly expressed in documents.

As already highlighted, place branding is a process and it should, in line with conceptualisations of inclusive place branding, be an evolutionary process (see Jernsand, Citation2016) and approached holistically (Richelieu, Citation2018). In studying the candidate files, the only processes that are present are those that are described in the documents. We consider the candidate files as place branding documents and valuable examples of written documents where inclusion policies could be probed and questioned. Lopes dos Santos and Gonçalves (Citation2022) also state that “besides being legally binding, bid files are the flag bearers for mobilising support for the Games … ” (p. 663). This includes both internal and external stakeholders. Thus we argue that the presence or absence of an explicit articulation of inclusiveness (measured through the proposed keywords) in these documents can provide insights into how the candidate cities communicate inclusiveness and to whom.

Data and method

The analysis is based on an exploratory quantitative and qualitative content analysis (Bryman, Citation2016) of the candidate files of Tokyo, Istanbul, and Madrid (candidates for the Summer Olympic Games in 2020), and Stockholm Åre and Milano Cortina (candidates for the Winter Olympic Games in 2026).

The five candidate files were selected based on two criteria: (1) candidate files produced and submitted after the Agenda 2020 came into effect, since the latter placed emphasis on, for example, including a broader set of stakeholders, and (2) candidate files from one Summer and one Winter Olympic Games, to limit the scope of candidate files and provide a more in-depth analysis of a limited number of candidate files, but also to encompass the different challenges in terms of scope and geographical challenges of Summer and Winter Olympic Games. Based on the first criterion, there were more possible candidate files available at the time of analysis. The bids, for example, for the Winter Olympics in 2022 (Almaty and Beijing) or the Summer Olympics in 2024 (Paris and Los Angeles). These were all omitted based on the second criteria.

All candidate files follow the format required by the IOC and contain five areas to be addressed (“Vision and Games concept”, “Games experience”, “Paralympic Games”, “Sustainability and Legacy”, and “Games delivery”). Candidate files from Tokyo, Milano Cortina, and Stockholm Åre were still available through their respective countries’ websites, while those from Istanbul and Madrid were retrieved from the Olympic World Library online depository (library.olympics.com).

We deploy an explorative approach with an aim to systematically extract and understand meaning from the candidate files and to draw credible conclusions from them (Bengtsson, Citation2016). We first identified the keywords based on the theoretical framework (see above), then we analyse how they appear and are used in the bidding documents through quantitative and qualitative content analysis (Longhurst et al., Citation2016; Silverman, Citation2015). In the quantitative analysis, we used a software (Sketch Engine) to analyse the entire candidate files, including the frequency of the keywords and the concordances – i.e. “a collection of the occurrences of a word-form, each in its own textual environment” (Sinclair, Citation1991, p. 32) – in each document to have an overview of the occurrences and visibility of the keywords in the candidate files (Evison, Citation2010). How the words are located, and how the usage of the words are connected to the four aspects of inclusive place branding were scrutinised manually. In the second step, we conducted qualitative content analysis (Bryman, Citation2016; Silverman, Citation2015) of the Visions and Olympic Games concept sections of the candidate files, to explore the meaning and significance of the ways in which inclusiveness was made visible and to highlight the differences and similarities between candidate files. We specifically focused on this section of the candidate files because it is where the general vision and idea of how to host the Olympic and Paralympic Games is presented and where inclusiveness issues such as human rights are the most visible. An in-depth qualitative analysis enhances our understanding of how and to whom inclusiveness is communicated.

We recognise that the five candidates are located in distinct political economic and socio-cultural national contexts, which has an impact on how inclusiveness is understood in each context. When, for example, focusing on ethnic and racial diversity, the five countries represent a common history of colonialism and settler-colonialism which affect the way minority population are treated. There is for example a stark contrast between Sweden and Japan. Despite that both countries lived the myths of racial and cultural homogeneity until recently, and the idea of being Swedish/Japanese historically and even today is based on race, common phenotype and culture (Kashiwazaki, Citation2009; Runfors, Citation2016; Yoshino, Citation1997), the two countries today stand opposite in the recognition of diversity. While Sweden recognises the diversity that has existed historically (national minorities) and the diversity that has emerged through immigration, Japan still declines the rights of foreign citizens living permanently in Japan and struggles also with the recognition of the diversity that has existed historically (Ainu and Ryukyu). While Japan sees an increase in immigration, only 2% of the population of 125 million are foreign nationals, contrary to Sweden where 20% of the total population of 10 million are foreign born. Italy and Spain’s foreign population are around 10% and 15%, and Turkey’s at 4% (OECD, Citation2024). Turkey and Japan similarly posit themselves as having one foot in the West and one foot in the East.

Gender equality also differs greatly between the five countries. The Global Gender Gap Report 2022 (World Economic Forum, Citation2022) shows Japan on 116th place, Turkey 124th, Sweden 5th, Spain 64th, and Italy on the 110th place among 146 countries compared. Acceptance of LGBTQI communities also varies greatly. The World Value Survey in 2019 showed that 54.4% of respondents in Japan answered that homosexuality is justifiable, while only 8% answered the same in Turkey (in 2018). In Sweden 75% (2011), and in Spain 66% (2011), answered that homosexuality is justifiable (World Values Survey, Citation2024).

Results and analysis

Frequencies and concordances of the keywords

To map out the prevalence and visibility of inclusiveness in the written documents, we analysed the frequencies and concordances of different keywords Milano candidate file have the largest corpus (60,000+), Stockholm, Madrid, and Istanbul have almost the same level of corpus (20,000+) and Tokyo file have the smallest corpus (18,000+). How frequent the keywords appear in the candidate files in relation to the whole corpus differ, with Istanbul using the keywords proportionally the most (1.6% of the total corpus) and Stockholm the least (1%). Madrid (1.4%), Milano (1.5%), and Tokyo (1.4%) use the keywords to the same extent.

The keywords include, involve, implement, local and community are the most frequent across the five candidate files, which together covers more than 50% of the total keyword appearances (). In Tokyo’s candidate file, these five keywords are the top keywords used. In Milano Cortina’s (include, involve, implement, and local) and Istanbul’s files four of these keywords (include, involve, local, community) are most frequently used, while Stockholm Åre (include, local, community) and Madrid (include, involve, implement) use three of the most frequent keywords. Keywords such as engage, commit, represent, and participate are also listed among the top 10, which are reflected in the top five keywords in the Istanbul, Madrid, Milano Cortina, and Stockholm Åre candidate files.

Keywords such as learn, accountable, empowerment, and knowledge, which potentially reflect explicit commitment to transformative aspects of inclusive place branding, and the specifics of who and what constitute inclusion (dialogue, residents, diverse) are very seldom used in the candidate files across the five countries.

In the next step. we examined the concordance for the 10 most used keywords (include, local, involve, community, implement, engage, stakeholder, participate, represent, and commit), which gives us an indication of when and how the keywords appeared in the candidate files. Overlapping concordances across candidate files indicate how the keywords are used similarly or differently across the candidate files (Appendix 1 summarises examples of the collocates). In general, the candidate files are ambiguous about who commits and are engaged to what, and which specific community is included. In other words, concordance patterns show little clarity about who is involved compared to what the target is – often the concordance overlaps. Expression of implementation is also ambiguous beyond infrastructural investments and the Olympic games itself. Thus details of potential transformation are lacking. For example, the keywords participate or engage show very diffused pictures about who participates or engages. Often it is about the country, community, and people in general, while specific interest groups, gender, race, or nationalities are left unmentioned. This is especially clear for the keyword “include*”. Milano Cortina and Stockholm Åre do mention diversity and equality in relation to the keyword but without any specific mention of what or who benefits from diversity and equality.

Milano Cortina stands out slightly from the other candidate files since involve and local are in concordance with specific references to “everyone” which include categories such as “community”, “highly-skilled”, “student”, “culture”, and “school”.

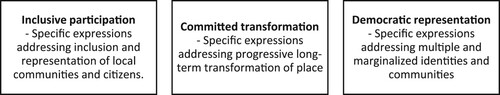

With the above patterns in mind, the conceptualisation proposed by Jernsand (Citation2016) is used to propose three characteristics of inclusiveness in the context of MSEs for the qualitative content analysis: inclusive participation (e.g. inclusion, involvement, participation, communities), committed transformation (e.g. learn, monitor, dialogue, commitment), and democratic representation (e.g. residents, diversity, citizen, responsibility). outlines these characteristics.

Our starting point in the qualitative analysis is that documents and policies can communicate inclusiveness to both internal and external stakeholders and we explore how these three characteristics are articulated in the five candidate files.

How inclusiveness is communicated

Democratic representation

The five candidates differ in the way they see their responsibilities for the people. Istanbul, Tokyo, and Stockholm Åre see their cities and countries in their entirety as bearing forms of social responsibility in their role as representatives of the people, placing the uniqueness of the country at the core. The three cities do not represent specific groups of interest or people, but represent responsibility in a global context, and as such primarily communicate with external stakeholders, also addressed in previous research (Björner, Citation2017; Mommas, Citation2003; Zhou et al., Citation2013). The most inimitable is the Tokyo candidate file, which does not focus much on democratic representation. As seen in the word count (), the Tokyo file stands out since diversity is considered much less than in other candidate files (2 counts). This leaves related human-rights issues nearly unaddressed.

The Milano Cortina and Madrid files, on the contrary, both recognise the representation of the people in their cities through paying specific attention to racial and ethnic diversity and groups with disadvantages and disabilities, and thus pluralistic representation (Jernsand & Kraff, Citation2017; McGillivray et al., Citation2019). These two candidate files clearly speak to internal stakeholders. Both identify and address social integration and discrimination as issues that the cities would continue to work with throughout the Olympic Games. This does not, however, guarantee that it will be realised.

The responsibility of the cities in terms of inclusion is clearly articulated. For example, dialogue and collaboration between stakeholders and the encouragement of participation by all stakeholders in the development, implementation and execution, together with the Organising Committee, are specifically spelled out on several occasions in the Madrid candidate file (p. 25). Dialogue and interaction between stakeholders, along with showing mutual respect, are considered key elements in inclusive place branding (Jernsand, Citation2016). Local support and interests are also spelled out in terms of sponsorship, tourism, and businesses that will contribute to the long-term growth of the city. In the long-term plan, target groups such as youth (pp. 19, 23) and the “new generation” (p. 17) are mentioned on several occasions.

With a lack of articulation of multiple identities, one cannot assume democracy and participation (Jernsand, Citation2016). Madrid’s candidate file depicts its diverse population – Madrid being “home to citizens of 194 different nationalities” (p. 17). Stakeholders at different governmental and societal levels are also described, giving a clear picture of who participates and commits to the Vision for the Olympics. When articulating multiplicity, Madrid communicates primarily to external stakeholders that the diversity of the city is a positive example for the world: “The diversity of the city of Madrid will provide the perfect stage to demonstrate to the world the idea of heterogeneity as a value which simultaneously champions the right to difference and to equal opportunities” (p. 21).

Similarly, Istanbul and Tokyo look outward and showcase themselves as examples of the multiplicity that the world will see. Stockholm Åre also stresses multiplicity, but what diversity refers to remains ambiguous. In the same candidate file, the word “unity” is used as a catch-all term to embrace “inclusiveness of all types” including diversity and disability. This invitation can be understood as directed at both internal stakeholders (who are marginalised and excluded from “our” Swedish culture) and external stakeholders who are to emulate the inclusiveness of Sweden.

Inclusive participation

Candidate files predominantly stress aspects of participation through sports, and not related to direct participation in decision making as stipulated by e.g. Kavaratzis and Kalandides (Citation2015). Participation is either alluded to in terms of an increased physical participation in sport (especially the participation of people with disabilities and different age groups) facilitated by the building of new sporting facilities or by watching the competitions in the arena.

What becomes very clear is the difference in the focus towards internal and external stakeholders: Istanbul, Tokyo, and Stockholm Åre appeal more to external stakeholders by stressing engagement through the uniqueness of the place and its position in the world. Here, the focus of participation is how people from other countries will be included and be part of this uniqueness. Istanbul and Tokyo stress the idea of “East will meet West”. In both candidate files, participation is portrayed as a willingness to include external (unspecified) stakeholders so that they can learn from and accept the countries in the global community. Moreover, the participation of the local community tends to be expressed from a top-down perspective. The Tokyo candidate file stresses how the local community will benefit from cultural exchanges with international visitors, through existing cultural institutions (e.g. the Tokyo 2020 Festival of Arts and Culture) and programmes directed both at the local community and at Games visitors. The local communities are, in this case, represented only as a resource to enhance the visitors’ experience. In general, the Stockholm Åre file lacks visibility concerning who the cities will involve and encourage participation by and engagement with. People are referred to as “every member of our society” (Stockholm Åre, p. 14) and “all Swedes” (pp. 14, 15) without any specific mention of who “we” are. There are also subtle but confident assertions that Stockholm Åre is, in fact, already an inclusive society, with Olympic values already realised and inviting the external stakeholders to be part of this inclusive society: “As a culturally diverse and open nation, we plan on inviting the world to participate in a celebration of sport through our country’s historically diverse communities, thus promoting the values of Olympism in our region and beyond” (p. 19).

On the other hand, Madrid and Milano Cortina set out to include the population of their own cities and how they will be empowered and benefit from participation in the Games. The Madrid candidate file is the only one which specifically states a strong commitment to encouraging the involvement of and participation by women in sports organisations. On different occasions, disability and the risk of social exclusion based on racial and ethnic background are raised together as issues (p. 19). As in the Madrid candidate file, Milano Cortina primarily addresses internal stakeholders, where local community development (both urban and rural) is a focal point. The engagement of local communities is mentioned in several processes – first, in connection to cultural heritage and the Cultural Olympiad (p. 5) and, second, in the development of the Olympic Village (p. 18). However, it is mentioned most prominently in the development of infrastructure, local culture heritage, and natural heritage management. Even if local communities are addressed as homogenous actors without portraying their diversity in terms of wants and needs, the participation is directed inwards to meet the needs of local communities. This is a prerequisite and an important ingredient in the adopting of a more inclusive place-branding and place development process (Jernsand, Citation2016).

Committed transformation

All five countries express their long-term commitment to change. However, descriptions of this commitment, and of how inclusive they are, differ between the files. For example, Istanbul focuses mainly on transformation through sports, especially the elite sports for “improvements in the performance of Turkish athletes in international competition” (p. 4). Tokyo, Madrid, and Milano Cortina connect their long-term commitment to their city planning. Tokyo integrates their commitments into the existing city-development plans which focus primarily on infrastructure development (the “Tokyo Vision 2020” and “Tokyo’s Big Change – The 10-Year Plan”). While there is less focus on how sport and cultural development are connected to the local community in Tokyo’s case, Madrid, and Milano Cortina focus on how infrastructure can contribute to the integration and inclusion of local communities. For example, Milano Cortina’s file specifies how the city intends to use the Games to generate “long-term transformative beneficial effects” (p. 8) for the host region through “all the public entities and local communities fully engaged in implementing their long-term development plans for the benefit of the entire Alpine macro-region” (p. 8). Milano Cortina and Madrid also communicate commitment to countering racism and discrimination. Milano Cortina highlights the already existing “Sport and Integration Project”, which started in 2014 and which states that sport is a powerful tool with which to promote social inclusion, counter racial discrimination and intolerance and promote multi-cultural understanding, both inside and outside schools (p. 8).

In general, transformation is primarily associated with changes through sports and infrastructure, which relates to McGillivray et al. (Citation2019) pathways and the component of sensitive urban development. Less is however mentioned explicitly with regard to changes of people’s attitudes, outlined as central by Jernsand (Citation2016) when it comes to transformation.

Discussion and conclusion

The qualitative analysis shows that Istanbul, Stockholm Åre, and Tokyo largely target external stakeholders, while Madrid and Milano Cortina focus more on internal stakeholders. The former candidate cities do not represent specific interest groups or local community groups but mostly communicate inclusion in a global sense. Milano Cortina and Madrid, on the contrary, both recognise the representation of residents (i.e. democratic representation) more explicitly through specific attention to racial and ethnic diversity and groups with disadvantages and disabilities. Even if Madrid and Milano Cortina do target internal stakeholders more, they also use the candidate files to target external stakeholders.

Based on this analysis, we argue that Istanbul, Stockholm Åre, and Tokyo are largely still firmly rooted in the more traditional place branding paradigm, focusing on uniqueness and a “unique selling proposition” to the “outside” (Colomb & Kalandides, Citation2010). Madrid and Milano Cortina are more internally oriented, with a focus on residents and stakeholders with whom they already have a relationship (cf. Insch & Florek, Citation2008). This is in line with what is stipulated in the literature on inclusive and participatory place branding (Jernsand, Citation2016; Kavaratzis & Kalandides, Citation2015). Except for the benefits of including the local community in place branding practices, from a human-rights perspective (McGillivray et al., Citation2019), it is also sensible to consider the numerous cases of local protests against Olympic Games. Emphasising local development involving multiple local stakeholders, including local residents, there is a greater likelihood that potential organisers will be able to avoid external and internal protests (Rowe, Citation2012). It might even be pivotal to be able to submit an Olympic bid, at least in democracies where local referenda are becoming increasingly frequent features in the bidding process (Lauermann & Vogelpohl, Citation2017).

This study posits the importance of making inclusiveness visible not only in the process of branding a place (Jernsand, Citation2016) but stating them in documents. Through making visible how and with whom an event is planned and implemented, the bidding host can increase transparency, inform stakeholders and, ultimately, make the bid and the process more inclusive (Hiller & Wanner, Citation2018).

Moreover, if the candidate file is used as a basis for planning and monitoring the actual outcomes, an inclusive process would lower the risk of “sport swashing” (see below) and make the host accountable and committed to transformation (Jernsand, Citation2016), which are the least explicit in the candidate files analysed. Commitment to transformation requires resources and funding (for implementation and monitoring systems) and therefore by explicitly stating how progressive social outcomes are implemented and monitored, the candidate files could be used more effectively as a tool to communicate and realise efforts in this direction (McGillivray et al., Citation2019).

Managerial and policy implications

We argue that stressing democratic representation, inclusive participation and committed transformation in the candidate files provides an indication of the candidates’ level of commitment to inclusiveness and human rights. Out of the five candidate files analysed, Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics is the only event that has taken place. Before, during, and after the Games, critical voices were raised against the organising committee for not making the Olympics a truly inclusive event in terms of diversity (when it comes to race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation) (e.g. Gunia, Citation2021; Yamaguchi, Citation2021). However, the analysis of the Tokyo candidate file shows that the organiser did not promise or promote inclusion in terms of diversity to any great extent and, as mentioned in the data and method section, Japan is not recognising diversity to the same extent as, e.g. Sweden. In fact, it was only after the mountains of criticism and the execution of the Olympics – and right before the Paralympics – that the Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games made their statement on Diversity and Inclusion Action.Footnote1 If sports-event managers and rights-owners (like the IOC or FIFA) would like the hosts to engage in inclusion and human rights, it would be effective to examine whether the candidates specifically mention and articulate how this will be stipulated in the candidate files. In this way, candidates can be held accountable by binding agreements, and expected to take responsibility, for planning and executing inclusive events. The proposed keywords and analytical framework of this study could be one piece of the puzzle in enabling the setting up of a good governance and monitoring system measuring whether events are managed and executed in an inclusive manner. Consequently, the candidate files can be a tool to monitor and assess processes of inclusion tied to MSEs.

It is important that showcasing diversity does not result in so-called sport washing, i.e. that candidates only talk the talk and do not execute stipulated plans. Sport washing is the act of using sporting events to clean up a poor image – for example, concerning human-rights issues. Branding activities are undertaken to portray an admirable image through the hosting of large sports events (Kobierecki & Strożek, Citation2021). Some hosts of the FIFA World Cup have been accused of sport washing previously, for example Qatar in 2022 and Argentina in 1978 (Fruh et al., Citation2023). However, sport washing is not necessarily associated with non-democratic countries and is not always intentional (Kobierecki & Strożek, Citation2021). To minimise the (ab)use of inclusiveness for sport washing activities, it is necessary that the transformative aspects of inclusive place branding are present and in place – i.e. a clear commitment, good governance, transparency, accountability, and monitoring (see ). Istanbul and Milano Cortina have the highest presence of these aspects in their candidate files. However, it is pivotal to monitor the outcome, so that host cities are held accountable for their actions. A recommendation, following recent research by McGillivray et al. (Citation2022), is that event governance and monitoring should be implemented in collaboration with advocacy organisations for human rights (i.e. NGOs, charities, and coalitions such as Amnesty International, UNICEF and the Centre for Sport and Human Rights).

In the pursuit of communicating the uniqueness of a place to attract tourists, previous research has shown how cities and nations imitate each other and, instead, become even more alike (cf. Berg & Björner, Citation2014; Pasquinelli, Citation2014). This does not have to be negative in terms of the scope of this article. Imitating bids, like that of Milano Cortina, which feature inclusive communication targeting internal stakeholders, would, in this case, drive more human-rights issues such as the inclusion of youth and local communities. However, to focus on uniqueness can also be problematic. It can result in a rather one-dimensional communication and place branding, as it enforces stereotypes (Bruner, Citation2005) and disregards the complexity that makes places interesting (Jernsand & Kraff, Citation2017; Kalandides, Citation2006), as exemplified in parts of the Stockholm Åre, Istanbul, and Tokyo candidate files. It is suggested that the diversity of places is acknowledged and even celebrated (Kavaratzis & Kalandides, Citation2015) and argued that such an approach leads to more authentic, credible, and appealing place brands for external stakeholders such as tourists (Ren & Stilling Blichfeldt, Citation2011). From examining the five candidate files, we do indeed see a pattern whereby focusing on uniqueness and external stakeholder’s candidate files tends to lose a specific attention to inclusiveness. In a Nordic context, known for progressive human-rights work and inclusive democratic processes (Cassinger et al., Citation2019), this could be a lesson for future bidding processes and the execution of MSEs: Be explicit about which local stakeholders that are included and how they are included, switching the focus from external to internal stakeholders.

Theoretical contribution

A contribution of this study is the adoption and a tentative development of an analytical framework based on inclusive place branding and pathways to progressive human-rights outcomes (Jernsand, Citation2016; McGillivray et al., Citation2019) to assess how and to whom inclusiveness is communicated in a written document. The framework is also an attempt to conceptualise inclusiveness in the context of MSEs.

This framework is summarised in and serves multiple purposes. The figure outlines three important characteristics (democratic representation, inclusive participation, and committed transformation) of how MSEs can work strategically with more inclusive place development processes considering human-rights issues (achieving event leverage), and delivering more sustainable events (Schulenkorf et al., Citation2024). Furthermore, it could be used as a tool to approach communication and inclusive place branding strategies for prospective hosts of MSEs. It could offer guidance on how to approach inclusive processes involving various stakeholders.

Limitations and future research

The sample of candidate files analysed in this study is small and would need to be complemented with data beyond the candidate files, such as insights on decision-making processes of the IOC (interviews, newspaper clippings, archival material, etc.) and more insights on social, cultural, and political factors related to each geographical context, to provide a more complete picture.

Going forward, the keywords and the analytical framework can be beneficial to use both at earlier stages in bidding processes, to analyse the processes leading up to the candidate file, and at later stages, to better understand MSE organisers who win the bid and go on to execute their strategies. While our study centres on communication of inclusiveness through MSEs, this exploratory attempt to measure inclusiveness and inclusive processes in (static) documents could also be transferred to other contexts and evaluate for example tourism development plans, event strategies for destinations, or single cultural and community events.

Further research could also explore inclusive processes more in-depth. When doing so, it would be useful to also include the fifth characteristic of inclusive place branding, the evolutionary process (Jernsand, Citation2016). This characteristic emphasises that inclusive place branding processes should be evolutionary and follow the changes in a place, in terms of, for example, diversity. Seeing that the lifecycle of MSEs – from planning the bid to hosting the event – is several years, this is crucial.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Abdi, K., Talebpour, M., Fullerton, J., Ranjkesh, M. J., & Nooghabi, H. J. (2019). Identifying sports diplomacy resources as soft power tools. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 15(3), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-019-00115-9

- Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

- Berg, P. O., & Björner, E. (2014). Branding Chinese mega-cities: Policies, practices and positioning. Edward Elgar.

- Björner, E. (2017). Imagineering place: The branding of five Chinese mega-cities [Universitetsservice US-AB, doctoral thesis]. Stockholm University.

- Braun, E., Kavaratzis, M., & Zenker, S. (2013). My city – My brand: The different roles of residents in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development, 6(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538331311306087

- Bruner, E. M. (2005). Culture on tour: Ethnographies of travel. University of Chicago Press.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Burchardt, T., Grande, J. L., & Pichaud, D. (2002). Degrees of exclusion: Developing a dynamic, multidimensional measure. In J. Hills, J. L. Grande, & D. Pichaud (Eds.), Understanding social exclusion (pp. 30–43). Oxford University Press.

- Butler, B. N., & Aicher, T. J. (2015). Demonstrations and displacement: Social impact and the 2014 FIFA World Cup. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2014.997436

- Cassinger, C., Lucarelli, A., & Gyimóthy, S. (2019). The Nordic wave of place branding. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Chan, C. S., Peters, M., & Marafa, L. M. (2016). An assessment of place brand potential: Familiarity, favourability and uniqueness. Journal of Place Management and Development, 9(3), 269–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-01-2016-0003

- Colomb, C., & Kalandides, A. (2010). The ‘Be Berlin’ campaign: Old wine in new bottles or innovative form of participatory place branding? In G. Ashworth & M. Kavaratzis (Eds.), Towards effective place brand management. Branding European cities and regions (pp. 173–190). Edward Elgar.

- Duignan, M. B. (2021). Leveraging Tokyo 2020 to re-image Japan and the Olympic city, post-Fukushima. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100486

- Evison, J. (2010). What are the basics of analysing a corpus? In A. O'Keeffe & M. McCarthy (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of corpus linguistics (pp. 122–135). Routledge.

- Fruh, K., Archer, A., & Wojtowicz, J. (2023). Sportswashing: Complicity and corruption. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy, 17(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2022.2107697

- Gaffney, C. (2016). Gentrifications in pre-Olympic Rio de Janeiro. Urban Geography, 37(8), 1132–1153. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1096115

- Grix, J., & Brannagan, P. M. (2016). Of mechanisms and myths: Conceptualising states’ ‘soft power’ strategies through sports mega-events. Diplomacy & Statecraft, 27(2), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592296.2016.1169791

- Grix, J., & Houlihan, B. (2014). Sports mega-events as part of a nation's soft power strategy: The cases of Germany (2006) and the UK (2012). The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 16(4), 572–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.12017

- Grix, J., & Lee, D. (2013). Soft power, sports mega-events and emerging states: The lure of the politics of attraction. Global Society, 27(4), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2013.827632

- Gunia, A. (2021, July 21). Japan failed to improve LGBTQ rights ahead of the Olympics. Japanese athletes are coming out anyway. Times Magazine, https://time.com/6078307/japan-lgbtq-athletes-olympics/

- Hanna, S., & Rowley, J. (2008). An analysis of terminology use in place branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 4(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.6000084

- Hereźniak, M., & Florek, M. (2018). Citizen involvement, place branding and mega events: Insights from Expo host cities. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 14(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-017-0082-6

- Hiller, H. H., & Wanner, R. A. (2018). Public opinion in Olympic cities: From bidding to retrospection. Urban Affairs Review, 54(5), 962–993. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087416684036

- Holden, M., MacKenzie, J., & VanWynsberghe, R. (2008). Vancouver’s promise of the world’s first sustainable Olympic Games. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 26(5), 882–905. https://doi.org/10.1068/c2309r

- Horne, J. (2018). Understanding the denial of abuses of human rights connected to sports mega-events. Leisure Studies, 37(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2017.1324512

- Insch, A., & Florek, M. (2008). A great place to love, work, and play: Conceptualising place satisfaction in the case of a city’s residents. Journal of Place Management and Development, 1(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538330810889970

- IOC. (2014). Olympic Agenda 2020: 20 + 20 recommendations. International Olympic Committee.

- IOC. (2021). Olympic Agenda 2020+5: 15 recommendations. International Olympic Committee. https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/IOC/What-We-Do/Olympic-agenda/Olympic-Agenda-2020-5-15-recommendations.pdf.

- Jernsand, E. M. (2016). Inclusive place branding: What it is and how to progress towards it [Doctoral dissertation, University of Gothenburg]. GUPEA. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/49535

- Jernsand, E. M., & Kraff, H. (2017). Democracy in participatory place branding: A critical approach. In M. Kavaratzis, M. Giovanardi, & M. Lichrou (Eds.), Inclusive place branding: Critical perspectives on theory and practice (pp. 11–22). Routledge.

- Kalandides, A. (2006, September 21–24). Fragmented branding for a fragmented city: Marketing Berlin [Paper presentation]. 6th European urban and regional studies conference, Roskilde, Denmark.

- Kashiwazaki, C. (2009). The foreigner category of Koreans in Japan: Opportunities and constraints. In J. Lie & S. Ryang (Eds.), Diaspora without homeland: Being Korean in Japan (pp. 121–146). University of California Press.

- Kavaratzis, M., & Ashworth, G. J. (2006). City branding: An effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick? Place Branding, 2(3), 183–194. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990056

- Kavaratzis, M., & Kalandides, A. (2015). Rethinking the place brand: The interactive formation of place brands and the role of participatory place branding. Environment and Planning A, 47(6), 1368–1382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15594918

- Kennelly, J. (2017). Symbolic violence and the Olympic Games: Low-income youth, social legacy commitments, and urban exclusion in Olympic host cities. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1206868

- Knott, B., Fyall, A., & Jones, I. (2016). Leveraging nation branding opportunities through sport mega-events. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(1), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-06-2015-0051

- Knott, B., Fyall, A., & Jones, I. (2017). Sport mega-events and nation branding: Unique characteristics of the 2010 FIFA World Cup, South Africa. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(3), 900–923. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2015-0523

- Kobierecki, M. M., & Strożek, P. (2021). Sports mega-events and shaping the international image of states: How hosting the Olympic Games and FIFA World Cups affects interest in host nations. International Politics, 58(1), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-020-00216-w

- Kolotouchkina, O. (2018). Engaging citizens in sports mega-events: The participatory strategic approach of Tokyo 2020 Olympics. Communication & Society, 31(4), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.31.4.45-58

- Laing, J., & Mair, J. (2015). Music festivals and social inclusion–The festival organizers’ perspective. Leisure Sciences, 37(3), 252–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2014.991009

- Lauermann, J., & Vogelpohl, A. (2017). Fragile growth coalitions or powerful contestations? Cancelled Olympic bids in Boston and Hamburg. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(8), 1887–1904. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17711447

- Longhurst, B., Smith, G., Bagnall, G., Crawford, G., & Ogborn, M. (2016). Introducing cultural studies. Taylor and Francis.

- Lopes dos Santos, G., & Gonçalves, J. (2022). The Olympic effect in strategic planning: Insights from candidate cities. Planning Perspectives, 37(4), 659–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2021.2004214

- Lucarelli, A. (2012). Unraveling the complexity of ‘city brand equity’: A three-dimensional framework. Journal of Place Management and Development, 5(3), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538331211269648

- Lucarelli, A. (2015). The political dimension of place branding [Doctoral dissertation, Stockholm University]. Holmbergs.

- Lucarelli, A., & Olof Berg, P. (2011). City branding: A state of the art review of the research domain. Journal of Place Management and Development, 4(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538331111117133

- MacAloon, J. J. (2017). Agenda 2020 and the Olympic movement. In E. Bayle & J.-L. Chappelet (Eds.), From Olympic administration to Olympic governance (pp. 31–49). Routledge.

- McGillivray, D., Edwards, M. B., Brittain, I., Bocarro, J., & Koenigstorfer, J. (2019). A conceptual model and research agenda for bidding, planning and delivering major sport events that lever human rights. Leisure Studies, 38(2), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2018.1556724

- McGillivray, D., Koenigstorfer, J., Bocarro, J. N., & Edwards, M. B. (2022). The role of advocacy organisations for ethical mega sport events. Sport Management Review, 25(2), 234–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2021.1955531

- Millward, P. (2017). World Cup 2022 and Qatar’s construction projects: Relational power in networks and relational responsibilities to migrant workers. Current Sociology, 65(5), 756–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116645382

- Minnaert, L. (2012). An Olympic legacy for all? The non-infrastructural outcomes of the Olympic Games for socially excluded groups (Atlanta 1996–Beijing 2008). Tourism Management, 33(2), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.04.005

- Mommas, H. (2003). City branding. NAI Publishers.

- Ndlovu, S. M. (2010). Sports as cultural diplomacy: The 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa’s foreign policy. Soccer & Society, 11(1–2), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970903331466

- OECD. (2024, March 4). International migration outlook. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/international-migration-outlook-2022_30fe16d2-en

- Ooi, C. S. (2011). Paradoxes of city branding and societal changes. In K. Dinnie (Ed.), City branding (pp. 54–61). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pasquinelli, C. (2014). Innovation branding for FDI promotion: Building the distinctive brand. In P. O. Berg & E. Björner (Eds.), Branding Chinese mega-cities: Policies, practices and positioning (pp. 207–219). Edward Elgar.

- Ren, C., & Stilling Blichfeldt, B. (2011). One clear image? Challenging simplicity in place branding. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(4), 416–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.598753

- Richelieu, A. (2018). A sport-oriented place branding strategy for cities, regions and countries. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 8(4), 354–374. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-02-2018-0010

- Rowe, D. (2012). The bid, the lead-up, the event and the legacy: Global cultural politics and hosting the Olympics. The British Journal of Sociology, 63(2), 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2012.01410.x

- Runfors, A. (2016). What an ethnic lens can conceal: The emergence of a shared racialised identity position among young descendants of migrants in Sweden. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(11), 1846–1863. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1153414

- Schulenkorf, N., Welty Peachey, J., Chen, G., & Hergesell, A. (2024). Event leverage: A systematic literature review and new research agenda. European Sport Management Quarterly, 24(3), 785–809. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2022.2160477

- Shi, P., & Bairner, A. (2022). Sustainable development of Olympic sport participation legacy: A scoping review based on the PAGER framework. Sustainability, 14(13), 8056. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138056

- Silverman, D. (2015). Interpreting qualitative data (5th ed.). Sage.

- Sinclair, J. M. (1991). Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford University Press.

- Suzuki, N., Ogawa, T., & Inaba, N. (2018). The right to adequate housing: Evictions of the homeless and the elderly caused by the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. Leisure Studies, 37(1), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2017.1355408

- Talbot, A., & Carter, T. (2018). Human rights abuses at the Rio 2016 Olympics: Activism and the media. Leisure Studies, 37(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2017.1318162

- Ulver, S., & Osanami Törngren, S. (2023). The empty body: Exploring the destabilised brand of a racialised space. Journal of Marketing Management, 39(15-16), 1477–1501. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2023.2249475

- Vanwynsberghe, R., Surborg, B., & Wyly, E. (2013). When the games come to town: Neoliberalism, mega-events and social inclusion in the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympic Games. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(6), 2074–2093. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01105.x

- Wickey-Byrd, J., Fyall, A., Panse, G., & Ronzoni, G. (2023). Mitigating the scale, reach, and impact of human trafficking at major events: a North American perspective. Event Management, 27(6), 931–950. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599522X16419948695152

- World Economic Forum. (2022). Global gender gap report. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2022.pdf

- World Values Survey. (2024, March 4). https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp

- Yamaguchi, M. (2021, August 4). Olympics carry a question: What does it mean to be Japanese? Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/2020-tokyo-olympics-japan-diversity-4c2094c8315cb1a655c367f2f9da9559

- Yang, Y. (2020). Looking inward: How does Chinese public diplomacy work at home? The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22(3), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120917583

- Yoshino, K. (1997). The discourse on blood and racial identity in contemporary Japan. In F. Dikötter (Ed.), The construction of racial identities in China and Japan (pp. 199–211). Hong Kong University Press.

- Zenker, S., & Govers, R. (2016). The current academic debate calls for critical discussion. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 12(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2016.2

- Zhou, S., Shen, B., Zhang, C., & Zhong, X. (2013). Creating a competitive identity: Public diplomacy in the London Olympics and media portrayal. Mass Communication and Society, 16(6), 869–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2013.814795