ABSTRACT

The study explores the role that change agency and regional preconditions play in a region’s path development. To address empirically this research question, the study uses the cases of two destinations in Norway during the COVID-19 pandemic. This research uses quantitative and qualitative data to investigate the industry’s capacity for path development in the face of significant external shocks. The findings reveal marked differences regarding industry adaptation and resilience between the two regions. While one destination struggled with coordination, the other, anchored by the popularity of a major zoo and theme park, demonstrated a more cohesive response. This contrast highlights the pivotal role of regional preconditions and change agency in shaping a destination’s ability to navigate crises. Key conclusions suggest that crises can serve as catalysts for industry development; however, the extent of such transformation is constrained by the regional preconditions, place leadership, and collaboration that a destination can mobilize.

Introduction

The tourism industry is characterized by its dynamism and susceptibility to external shocks and crises (Alvarez et al., Citation2022; Cró & Martins, Citation2017; Hall, Citation2010; McKercher, Citation2021). These events, such as economic downturns and pandemics, can significantly impact the sector and the regions that rely on tourism. In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic hit the Norwegian tourism industry and has posed substantial challenges to the industry (Tveteraas & Xie, Citation2021; Xie & Tveterås, Citation2020). In the face of such a crisis, questions arise about the industry’s ability to respond, adapt, and evolve in adversity (Rypestøl et al., Citation2022; Trippl et al., Citation2020).

In economic geography, change agency theory offers a novel lens to examine adaptability and resilience. Despite its promising application, change agency currently sees limited use in tourism studies. This gap presents an opportunity to deepen our understanding of the dynamic interplay between trigger events – such as natural disasters, economic shifts, or social changes – and the subsequent evolution of tourist destinations (James et al., Citation2023). Change agency theory delves into the capacity of agents to react to external events by creating and exploiting opportunity spaces (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Kurikka & Grillitsch, Citation2021). Grillitsch, Sotarauta, et al. (Citation2022) propose that the capacity of change agency depends on various factors, including regional preconditions, agency being the primary causal force, and external events, which are often beyond the sphere of influence of local actors. This proposition implies that industry structure, such as firm size, technology, and know-how, serve as indicators of regional preconditions of the tourism industry and can influence the diversification of a tourism destination’s development path during a crisis.

Furthermore, Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) distinguish between three modes of change agency, characterized by the presence of Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship, institutional entrepreneurship, and place leadership. These modes can significantly affect a destination’s ability to bounce forward (Grillitsch, Asheim, et al., Citation2022; Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Kurikka & Grillitsch, Citation2021). For instance, Destination Management Organizations (DMOs) or local key players, such as organizations responsible for important tourist attractions or activities in a region, can act as place leaders, driving innovation and fostering cooperation among stakeholders to enhance the economic resilience of the region (Martin & Sunley, Citation2014).

The tourism industry comprises many micro, small, and medium-sized firms (Singal, Citation2015). The size distribution implies that the typical tourism firms have limited financial, knowledge, and technological capacity to reinvent themselves or diversify their offerings (Booyens et al., Citation2022). On the other hand, being nimble means that small tourist firms may act with agility during crises (Dahles & Susilowati, Citation2015). Nonetheless, smaller firms’ potential for actions will be constrained by a more limited set of dynamic capabilities (Prayag et al., Citation2023). Understanding how these potential advantages and disadvantages of being small influence adaptability in times of crises is therefore necessary.

Industry structure encompasses the network characteristics of a tourism industry in a destination. The degree of interrelations among firms and organizations varies across contexts (Del Chiappa & Presenza, Citation2013; Koens & Thomas, Citation2015; Peters & Kallmuenzer, Citation2018). The network may be loosely knit in a destination, with limited cooperation among firms (Baggio, Citation2010). Conversely, a strong destination management organization or other sources of place leadership may help to create more robust networks and cooperation (Haven-Tang & Jones, Citation2012; Hristov & Zehrer, Citation2015; Shen & Chou, Citation2022). How organizations in a destination are interrelated can influence a destination’s ability to recover from a crisis.

This paper explores the roles change agency plays and regional preconditions’ presence in a regional’s path development. The regional preconditions in this study are covered by focusing on the industry structure of tourism in a region reflected by firm size, technology, and know-how. The primary objective is to unveil how these factors influence a destination’s capacity for path renewal, especially in crises. Failure to evolve and the persistence of maintaining the status quo by doing “business as usual” can lock destinations into a state of path dependence (Brouder, Citation2020), in which historical decisions and past development patterns continue to shape the trajectory of a destination. Breaking free from a trajectory by forging a new path implies a path change, enabled by agents in a destination that exert leadership, adapt, and evolve, thereby altering their current path. Such a process enables these agents to craft innovative solutions to unforeseen challenges, transforming potential obstacles into opportunities for growth and new ventures.

To empirically investigate these factors and their impacts on a destination’s economic resilience, this paper will focus on the cases of the Stavanger and Kristiansand regions in Norway during the COVID-19 pandemic. The selection of these two regions is motivated by two primary considerations. First, both regions encountered significant challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic and had different regional preconditions to deal with the crisis. Second, the two regions’ different tourist offerings and market orientation can influence regional path development. Since tourism is often demand-driven (Hall and Page, Citation2016), it is essential to investigate how different market orientations may affect the destination’s resilience.

In this study, we first document the regional preconditions of the tourism sector using statistical data. These descriptive data highlight how these conditions influence the industry’s capacity for path diversification in response to crises. Subsequently, the research employs interviews to illustrate how the COVID-19 pandemic has shaped change agency and the responses of firms in the two destinations. This methodological approach provides a nuanced and context-sensitive understanding of the sector’s adaptation to crises (Ritchie, Citation2004).

Literature background

Tourism industry in a destination

Tourist destinations are complex amalgamations of offerings by various branches of firms directed towards tourists and travelers. A useful distinction is to classify tourism into primary, secondary, and ancillary tourism services (Page, Citation1995). Primary tourism is the core services directly related to the tourism experience, like accommodations, attractions, and transportation services. Secondary tourism services support the primary tourism activities and enhance the overall tourism experience. They include the likes of restaurants, souvenir shops, tour guides, travel agencies, and recreational facilities. Secondary services contribute to facilitating and enhancing the visitor’s experience. Ancillary tourism services encompass various activities such as banking and financial services, telecommunications, insurance, infrastructure development (e.g. roads, airports), and waste management. They provide the necessary support and infrastructure for both primary and secondary tourism activities to operate smoothly.

What unites various branches of the tourist industry, whether in primary or secondary services, is the relatedness of demand for its products from the same group of customers. Even if the tourist services are diverse, serve disparate customer needs, and employ distinct production technologies, the customer segments of the same products can overlap. For example, both hotels and coach transportation serve business and tourist guests, but coach firms also serve other segments like commuters and the local community (e.g. school day excursions). The degree of overlap among the customer segments served by diverse tourist firms creates interrelatedness among a destination’s firms.

A system view reflects interdependencies among firms belonging to different but related tourism industries in a destination. The tourist system consists of local co-producing actors that provide complementary products (Haugland et al., Citation2011). These interdependencies can also be seen in the broader context of place marketing, where urban destinations are “reimagined” and “every urban product is an assemblage of selected resources which are bound together through interpretation” (Hall et al., Citation2008). Such imaging efforts lead tourist firms in a destination to cooperate on marketing, product development, and sales channels to the joint benefit of participants. Elvekrok et al. (Citation2022) argue that the outcomes of the nature of these collaborations can be linked to (1) individual firm success or (2) destination development, but seldom to both simultaneously.

The ability of tourism firms to simultaneously achieve these two goals is often constrained, primarily due to small firm size (Elvekrok et al., Citation2022; Safonov et al., Citation2023). The average size of a firm in the tourism sector differs from most other industries. The tourism industry tends to be characterized by micro, small-, and medium-sized firms, resulting in a highly fragmented industry (Baggio, Citation2010). Although there are large corporations like hotel chains, international cruise companies, theme parks, and tour operators, the multitude of small firms is a defining characteristic of tourism (Singal, Citation2015). Consequently, the degree of fragmentation within a destination’s tourism industry can influence the presence or absence of effective place leadership.

Path development

Traditional economic theory offers limited insights into the dynamics of change and innovation processes caused by crises (Nelson & Winter, Citation2002). Arthur’s (Citation2023) observation that economic theory is about nouns (e.g. quantities of different variables) and not verbs (e.g. change processes) mirrors this sentiment. Therefore, we choose to address this research question in light of evolutionary economic geography (EEG). This research does not concern itself with crisis management but rather how regional preconditions affect tourist firms’ agency for response and adaptation in times of crisis. In this respect, the evolutionary economic geography approach is apt for studying crisis and resilience in tourism due to its emphasis on the dynamic and spatial aspects of economic development and adaptation (Weichselgartner & Kelman, Citation2015). The approach is particularly relevant in the context of tourism, an industry significantly impacted by geographical, environmental, and socio-economic factors. Boschma and Frenken (Citation2006) provide a lens for analyzing the geographic formation of economic activity as an evolutionary process that recognizes the complex system formed in a Darwinist fashion (see, e.g. Brouder and Eriksson (Citation2013) for a review).

Path development or regional path development is generally divided into a variety of categories, including (1) path extension, (2) path diversification or renewal, and (3) path creation (Trippl et al., Citation2020). There is also a fourth dimension, (4) path exhaustion, representing an unsustainable development. In a way, these paths can be linked to the ranges of potential outcomes between decline and rejuvenation in Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model (Brouder & Eriksson, Citation2013). However, in contrast to the TALC model, which has a relatively limited focus on carrying capacity, the pathways outlined in the EEG attempt to account for the complexities involved in developing tourism destinations (Ma & Hassink, Citation2013).

Path extension presents the continuation of the existing structures and can be likened to a fixed trajectory, where a destination tends to rebound and return to its pre-crisis state (Hall, Citation2017). Brouder (Citation2020) raised concerns about the limitation of this path dependency in addressing global environmental challenges. He points to crises as an opportunity to change for improved pathways. Path diversification or renewal means that new industrial capabilities and pathways are created by building on the current knowledge and combining it with new but related knowledge (Neffke et al., Citation2011). Finally, path creation is the most radical change as it points to creating an entirely new industry.

Path development in a tourism region is influenced by various factors, as explained in the theoretical framework by Grillitsch et al. (Citation2022). Changes in economic activities are driven by three factors: (1) regional preconditions, (2) agency as the main causal power, and (3) external events. A fragmented tourism industry can represent the regional preconditions that influences path development. Small firms often function as a generator of sameness due to their limited innovative capacity to do things radically differently or provide significantly different offerings (Booyens et al., Citation2022). In highly competitive sectors such as restaurants, café, guide services, or some other tourist services, emulating existing businesses may also be more feasible than attempting to evolve new path development as firms’ renewal capacity is constrained by their small scales, low returns on capital (Falk et al., Citation2021).

Agency

Change agency refers to deliberate, goal-oriented human actions to bring about change, including both their intended and unintended consequences (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). Although abstract by nature, change agency offers a practical perspective for examining the responses of companies, industries, or regions to crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Unlike the neoclassical economic approach, change agency accommodates the diverse nature of agents’ actions (Grillitsch, Asheim, et al., Citation2022). This means that economic agents may react differently to a crisis, providing a more nuanced understanding of the change process. Consequently, the responses of various actors may either align or conflict with each other.

To clarify the idea of change agency, Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) identify three modes, collectively referred to as the Trinity of Change Agency. The first mode, Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship, involves entrepreneurs disrupting existing equilibriums to pursue new, improved ones (Kirzner, Citation1973). In crises, this translates to entrepreneurs abandoning old approaches and seeking new paths or equilibriums, as traditional methods may no longer be optimal. In tourism, this could be exemplified by businesses migrating to digital platforms for distribution.

The second component is institutional entrepreneurship, which encompasses the efforts of economic actors (individuals, organizations, or groups) to transform existing institutions or create new ones (Battilana et al., Citation2009). Institutions are human-created constraints shaping political, economic, and social interactions and can be either informal (traditions) or formal (laws) (North, Citation1991). This form of entrepreneurship is crucial because firms operate within multiple systems and must adhere to various institutions at industry, regional, and national levels. An example of institutional entrepreneurship could be lowering employers’ taxes on hiring labor, especially for hospitality and restaurant services.

The final element is place-based leadership. Place-based leadership entails individuals or groups coordinating efforts among different actors. Sotarauta and Beer (Citation2017) argue that regions require skilled and influential actors possessing strong leadership abilities to effectively address social, environmental, and economic processes. Place-based leadership aims to prioritize the common good of an industry or region, including aligning diverse interests and coordinating the use of shared resources (Grillitsch, Asheim, et al., Citation2022). For example, a DMO or a prominent tourist firm could act as essential place leaders in a destination (Hristov & Zehrer, Citation2015). Lemmetyinen and Go (Citation2009) have identified leadership as one of the most important capabilities for managing tourist industry networks, and as such, place leadership is a crucial capability.

Martin (Citation2011) underscores the importance of human agency in resilience against a crisis, noting that individual firms and workers vary in their ability to adapt, switch activities, navigate local constraints, access resources, and pursue economic preferences. Bristow and Healy (Citation2014) further emphasize the significance of human agency in understanding regional economic resilience. Grillitsch, Sotarauta, et al. (Citation2022) contribute to this discussion by proposing a theoretical framework explaining new path development. They argue that a regional economy’s preconditions, shaped by past actions and interactions, influence human agency. Human agency, in turn, impacts the path development in the region after a crisis. A key insight from their work is identifying agency as the primary causal force in path development.

Despite the burgeoning research on path development in tourism, little research has been devoted to the role of change agency in the context of navigating through crises. Page (Citation2006) observed that most changes to path development are linked to adverse external events. From this departure point, it follows that investigating change agency can enhance the depth and richness of these narratives. Specifically, this study contributes to exploring this research gap by focusing on how change agency and related factors can influence path development during crises in the tourism industry. A key question is whether the tourism industry can exploit crises to reach favorable outcomes or whether the lack of change agency puts the industry at the mercy of external forces.

Research setting

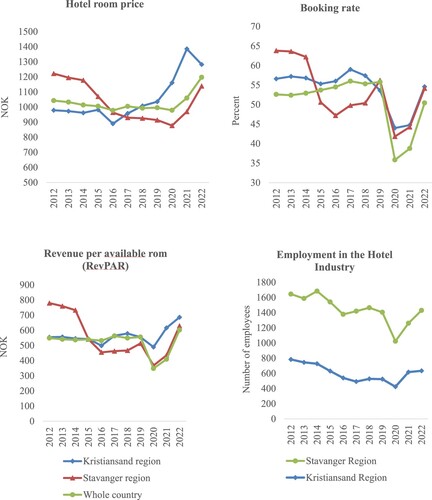

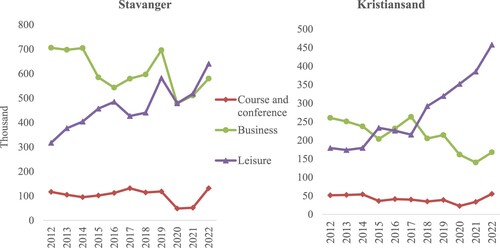

To provide essential context for the study, in this section, we discuss the tourism industry in the two selected regions, Stavanger and Kristiansand, focusing on the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on the local tourism industry. These two regions have populations of roughly 300 and 150 thousand, respectively, and where a majority live in urban areas. and include indicators on overnight stays by segment, hotel room prices, booking rate, RevPar, and employment in the hotel accommodation industry in the two regions, respectively, and at the national level for comparison. These figures are used to highlight differences in regional developments when discussing the two case studies below.

Figure 1. Hotel overnight stays in Stavanger and Kristiansand regions (Data source: Statistics Norway 2023).

Case 1: the Stavanger region

The oil and gas (O&G) industry completely encapsulates the Stavanger region’s economic development. This implies that tourism only plays a relatively minor role in the regional economy. However, the region is home to two of Norway’s most popular tourist attractions, the Pulpit and the Kjerag rock formations, both located in Lysefjorden. In addition, the O&G industry has induced tremendous business-derived demand for tourist-related services. As a result, O&G has prompted investments in primary and secondary tourism services. For example, meetings, conferences, and team-building events linked to the O&G industry have paved the way for developing tourist guides and adventure services. In this way, the Stavanger region has developed tourism infrastructure and services for both business and leisure tourists.

Because the tourism industry in the region is so heavily reliant on business demand stemming from the O&G sector, it can be directly affected by fluctuations in the O&G industry. One such example is the oil price crisis in 2014. The left panel of shows that in the Stavanger region, hotel overnight stays in the course and conference segment and the business segment dropped markedly from 2013 to 2014. The full negative effect took longer and led to structural changes in demand, as suggested in . Specifically, the leisure segment started to become the driving force for tourism growth in the region. This trend strengthened after the COVID-19 crisis.

In response to the reduced demand initially triggered by the oil price crisis and later by the COVID-19, hotel prices in Stavanger experienced a substantial decline between 2013 and 2020 (). Regarding the booking rate, it is almost the same. Low prices and booking rates jointly contributed to the significantly low hotel performance, as suggested by the revenue per available room (RevPAR). RevPAR is a key metric used in the hotel industry to assess a hotel’s ability to fill its available rooms at an average price in a given period. These hotel performance metrics suggest that the economic impact on regional tourism is much more severe from the pandemic than the oil price crisis. This is expected as the pandemic heavily hit all the demand segments, whereas the oil price crisis only affected the business segment.

Case 2: the Kristiansand region

The Kristiansand region boasts the distinction of being Norway’s sunniest locale, and it is home to the country’s largest zoo amusement park, Dyreparken. The region has a daily cruise ferry to Denmark, making it accessible to many Northern Europeans by car. While the tourism industry in Kristiansand is smaller in scale compared to Stavanger, its leisure segment has always held a more prominent position. The right panel in , which presents the hotel overnight stays in Kristiansand, clearly illustrates a substantial upswing in the leisure segment since 2017 and the importance of this segment in the region.

The Kristiansand region was only mildly affected by the oil price crisis in contrast to the Stavanger region, which was severely paralyzed. As depicted in , the adverse effects on the hotel room price and booking rate during 2015 and 2016 in Kristiansand were lower and more transitory than in Stavanger. Likewise, the impact on RevPAR in Kristiansand is smaller.

The increase in hotel room prices in the Kristiansand region between 2016 and 2021 can be attributed to a surge in domestic summer tourism, initially fueled by a weakened Norwegian currency following the oil price crisis and later amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic. With international travel severely restricted, many Norwegians opted for domestic vacations, increasing demand for accommodations. The pleasant weather and the renowned national zoo and amusement park (Dyreparken) in the region made the region the most popular domestic summer destination.

The employment data in reveals a consistent pattern with RevPAR. The challenges faced by the hotel industry during the oil price crisis and the pandemic have reduced employment, indicating a correlation between hotel performance and workforce adjustment.

Research method and data collection

Informed by Ritchie’s (Citation2004) call for a multifaceted research approach to enhance our understanding of crisis and disaster management in the tourism industry, this study utilizes both quantitative and qualitative data. Following his recommendations, our research seeks to elucidate the complex interplay between industry-level trends and micro-level dynamics at individual firms. Quantitative data at the industry level is used to investigate regional preconditions, while qualitative data, i.e. interviews, are used to illustrate how firms have adjusted to the COVID-19 crisis. This approach enables us to systematically explore the interplay between regional preconditions, firm-level adaptations, and change agency in the tourism sector.

Initially, our quantitative analysis focuses on key indicators such as industry structure, technology adoption, and industry know-how to assess the regional preconditions affecting the tourism industry’s capacity to withstand and recover from crises. This data provides a baseline for understanding the industry trends and structural dynamics, setting the stage for a comprehensive examination of the industry’s resilience mechanisms.

Building on this quantitative foundation, we conduct qualitative interviews with stakeholders from selected tourism firms and DMOs. These interviews are designed to delve deeper into the experiences and perspectives of those directly involved in navigating the challenges posed by the crisis. By integrating these personal narratives with the quantitative data, we achieve a richer, more nuanced understanding of the adaptation and recovery processes. The qualitative insights humanize the statistical findings and illuminate the complex, underlying factors that influence a firm’s ability to adapt and thrive in the face of adversity.

Through this methodological sequence, our study underscores the importance of regional preconditions as a backdrop against which individual firms’ strategies and change agency are enacted. The qualitative data, enriched by the context provided by the quantitative analysis, offers vivid empirical illustrations of how tourism firms adapt to crises. This integrative approach enhances the empirical robustness of our findings, demonstrating a coherent linkage between macroeconomic conditions and micro-level adaptations.

The descriptive data

The quantitative data used in the study include the following six indicators to measure the preconditions of the tourism industry: (1) the number of firms, (2) the firm’s operating margin, (3) firm’s fixed assets, (4) the share of temporary employees, (5) the percentage of employees with university educations, and (6) the share of firms reporting any kind of innovation activities in each tourism sector. The number of firms, the firm’s operating margin, and fixed assets indicate the size and resource capacity of firms’ path diversification under crises. As discussed previously, we presume that small and less profitable firms have constrained capacity and low willingness to develop new products and extensive networks. Further, the share of temporary employees and the level of education are used as indicators for the industry’s technology and know-how levels. Finally, the concrete reported numbers of innovation activities directly measure the possible path diversification in the industry.

These indicators were compared between tourism and other industries, and special attention has been paid to the oil, gas, and mining industry (OGM) because the industry dominates the Norwegian economy by contributing 40% of the country’s exports and 14% of its GDP (SSB, Citation2023a), and the Stavanger region is the national center of oil companies. Since regional data is unavailable from Statistics Norway (SSB), we have utilized national data in our analysis. However, Stavanger and Kristiansand are two of the most popular tourist destinations for domestic and international travelers. Therefore, we believe the results drawn from the national data will likely provide a reasonable representation of the tourism industry in these two regions.

All the data are time series except for the innovation indicator, which is survey data collected by the SSB between 2018 and 2022. SSB conducts such a survey every two years where firms report innovation activities in products, services, processes, and organization. Some computation and aggregation were conducted for the purpose of analysis.

Semi-structured interview

Qualitative data collection took place during the first quarter of 2022 using semi-structured interviews. This approach was specifically chosen due to its numerous advantages, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the participants’ perspectives (Brinkmann & Kvale, Citation2018; Yin, Citation2018).

We conducted three interviews in each region with participants from DMOs, hotels, restaurants, and the biggest amusement park in Norway. This regional and sector diversity was essential for capturing various viewpoints and experiences. To align with our research objective of gaining insights into crisis responses, we interviewed top leaders, such as managers or CEOs, in the selected organizations. These leaders typically possess decision-maker authority and a broader understanding of the organization’s resources, strategies, and industry role in a destination.

The interviews were conducted in person at the participants’ workplaces, providing a personal and comfortable setting, and via Zoom for four participants due to the pandemic. Zoom provides a convenient and accessible platform for participants to share their thoughts and experiences. The entire qualitative data collection process, encompassing interviews, recordings, transcriptions, and data storage, was meticulously conducted in compliance with the guidelines set forth by Sikt (the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research), ensuring compliance with ethical and procedural standards.

Findings

Regional preconditions of the tourism industry

Creating an opportunity space for change agency is intrinsically linked to regional preconditions (Grillitsch, Asheim, et al., Citation2022). Therefore, before delving into the details of how firms responded to the COVID-19 crisis, we first explore the regional preconditions. This section gauges the preconditions of the tourism industry in these two destinations using indicators for the industry's performance and resources. When compared between tourism and other industries, these indicators, with a particular focus on the oil, gas, and mining industry (OGM), shed light on the preconditions in the Stavanger region. For the Kristiansand region, the industry structure is closely approximated by the national level, except that there exists a big player, Dyreparken.

The selected indicators include firm number, average firm’s operating margin, firm’s fixed assets, the share of temporary employees, the percentage of employees with university educations, and the share of firms reporting any kind of innovation activities in each tourism sector. These indicators all indicate capacity for leadership, entrepreneurship, and innovation.

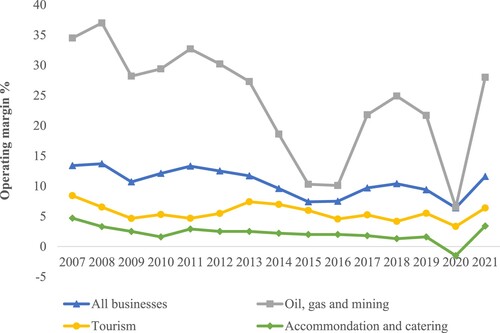

compares the performance of the tourism industry with other industries. The numbers in the table are the average results in the sample periods between 2018 and 2022. Given the absence of data for the tourism industry, we have aggregated data from individual tourism branches, including hotel and similar accommodations, restaurants and other catering, cultural and entertainment experiences, and transportation. Except for the firm number, which can be added across the branches, other performance indicators are calculated as the weighted average of the corresponding indicators in each branch. The weight used is the firm number in each branch. As typical in the global tourism industry, the accommodation and catering (A&C) sector is dominant in the tourism industry. It has, therefore, been separately discussed in the study. The A&C firms accounted for 43% of the total tourism firms in our sample period.

Table 1. Compare tourism with other industries between 2018 and 2022. Data source (SSB, Citation2023a; Citation2023b).

The table shows that the tourism industry had firm numbers about 17 times more than OGM. The single A&C sector has firm numbers that are 5.7 times bigger than those of OGM. Together with the large number of firms, firm scales were much smaller in tourism than in other industries. The average fixed asset per firm was 6.6 million Norwegian kroner (NOK) in A&C compared to 1513 million NOK in OGM. With 41 million NOK per firm, the situation in the entire tourism industry was slightly better thanks to the relatively bigger investment in the transportation branch.

The low fixed assets associated with the considerable number of firms suggest that many small firms in the tourism sector have low investments. Although small firms and low investments do not necessarily lead to low profitability, this is the case in the tourism industry. The operating margin in the sector has generally been meager in recent years. suggests the margin in A&C was the lowest (−1.5%) in 2021 and highest (4.7%) in 2007 and had gradually worsened before 2021. The decreasing margin was explained by the steady growth in firm numbers and the declining average firm fixed assets. The tourism industry’s average operating margin () was 5.6% compared to 24.1% in OGM. The average margin in A&C was down to only 2.2%.

Tourism creates many jobs globally. However, in contrast to its significant contribution to employment, the industry faces several human resource challenges, including the lack of qualified staff, the unwillingness of university graduates to enter the industry (Qui Zhang & Wu, Citation2004), and many seasonal workers (Zhang et al., Citation2021). In Norway, only 17% of the total employees in the tourism industry had a university education, compared to 27% in all the industries averagely. In A&C, the share of temporary workers was 12.7% compared to an average of 4.1% in all industries. At the same time, 31% of the tourism employees were young people between 15 and 24 years old, and 44% were immigrants (SSB, Citation2023a).

According to the most recent survey done by the SSB between 2018 and 2022 (SSB, Citation2023b), 76% of the Norwegian OGM firms reported that they had at least one type of innovation activity in the three innovation categories of the product, process, and business model innovations. The reported share in tourism was 46%, and the share in A&C was 49%. Both were much lower compared to OGM.

The above data shows that the dynamic capabilities of the tourism industry are constrained by small firm size, low profitability, and lack of educated and experienced employees. These challenges are expected to limit the industry’s change agency since dynamic capabilities are largely determined by knowledge and technology resources. Nevertheless, resource constraints can be circumvented by forming networks among the large number of tourism firms.

Let us now turn to explore regional preconditions that influenced firms’ responses to the COVID-19 crisis in conjunction with change agency.

Change agency case 1: the Stavanger region

As documented by the hotel overnight data, the hospitality industry in Stavanger transitioned from highly lucrative business travelers to leisure visitors in the decade preceding the COVID-19 pandemic. This restructuring was driven by the oil price crash in 2014, which led to a sharp drop in business demand. However, in terms of impact on the tourism industry, the COVID-19 pandemic was more severe than the oil price crisis. Nevertheless, the Stavanger region is familiar with pronounced economic cycles due to its strong reliance on one industry complex, O&G. An interviewee mentioned the benefit of learning from previous crises:

One thing that has helped our region a lot [during the pandemic] is the oil crisis the region went through … We knew we needed to reduce costs, to reduce manning, and get fewer people to do more tasks.

As time passed businesses tried to adapt offerings. This proved challenging due to the unpredictability of governmental lockdowns and restrictions ushered by each new wave of COVID-19 contagion. However, in a Schumpeterian sense, the pandemic inspired positive change. Digital online technology for ordering food and drinks in cafes and restaurants suddenly received broad applicability. Attempts to introduce the technology earlier in the hospitality and restaurant industry had been unsuccessful. The negative attitude towards this technology changed with the lockdown situation, as its value-proposition multiplied. Similarly, digital touch-free hotel check-in made a breakthrough during the pandemic. These are examples of how crises can increase the speed of deployment of new technology. This shows some level of change agency at the individual business level demonstrated through adaptations and innovation.

Change agency case 2: the Kristiansand region

Most tourism businesses in the Kristiansand region fared better than in Stavanger during the pandemic. The hotel overnight stays, and RevPAR data depicted in and show this disparity in impact between the two destinations. In Kristiansand, there was also a sharp reduction in demand. For the hotels, the crisis presented an opportunity to reevaluate and reset their operations. One respondent stated, “suddenly, one got the opportunity just to trim down the whole tree, keep the strong branches and the strongest, best fruits.”

The zoo and amusement park (Dyreparken) in Kristiansand is a significant player in the regional tourism industry. Its scale contrasts with the small scale of most firms in Norway’s tourism industry. It employs nearly 170 permanent staff members and over 1,000 seasonal employees, firmly establishing itself as a pivotal contributor to the local economy. Its economic contribution goes beyond its business and employment, with positive regional spillover effects. Two interviewees stated that for each 1 NOK spent by a tourist in Dyreparken, a substantial economic ripple effect of 4–5 NOK is generated across the wider region.

One interviewee specifically said:

We couldn’t rely on others or wait for things to happen. Many people in the tourism industry approached me [the CEO] during that period, expressing their support and encouragement. We [Dyreparken] are fully aware of the impact it would have if we didn’t achieve a high number of guests during the summer season.

Dyreparken also exercised agency by collaborating with local health authorities. Support from the local health authorities, which recognized the benefits for people to visit the zoo and theme park during a time of distress, provided Dyreparken with flexibility. Dyreparken committed its resources to ensure these strict pandemic restrictions were met, reinforcing the authorities’ positive perspective.

In summary, the tourist industry in the Kristiansand region navigated the rough waters of the pandemic remarkably well, primarily due to the region’s favorable weather conditions and the presence of Dyreparken as the main tourist attraction. The positive outcomes at a regional level are also clearly reflected in , which shows a significant increase in hotel overnight stays, and , which illustrates both high hotel room prices and high RevPAR in the region during the pandemic. Collaboration between Dyreparken, a prominent place leader in the region, with local authorities and other tourism businesses demonstrated abilities to exercise change agency at the system level in Kristiansand.

Discussion

By analyzing and comparing the Stavanger and Kristiansand regions, we aim to obtain a broad understanding of change agency in tourism and its ability to influence path development during a crisis. As discussed in the introduction, failure to evolve and the persistence of doing business as usual can lock destinations into a state of path dependence (Brouder, Citation2020). Path renewal in a destination builds on cooperation between various actors in the destination’s tourism system to leverage resources and diversify their offerings (Booyens et al., Citation2022; Haugland et al., Citation2011). In this way, new industrial capabilities and pathways can be built on the existing structures, knowledge, and competencies (Neffke et al., Citation2011).

Focus on change agency directs us to explore to what extent these adaptations happen at the firm level and the destination level (Grillitsch, Asheim, et al., Citation2022). Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) recognize three forces behind change agency: Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship, institutional entrepreneurship, and place leadership. The varying degrees of presence of these forces are observed in the Stavanger and Kristiansand cases. The comparatively weak preconditions of the tourist industry when comparing key economic indicators with other industries contribute to explaining the lack of change agency in parts of the industry.

In the early stages of the crisis, associated with the emergency phase of crisis and disaster management (Faulkner, Citation2001), the agency takes place mainly at the firm level. The case study findings suggest that the first responses to adverse demand shocks and harsher economic realities are scaling operations down and reducing costs. The cutback of operations and reduction of employment imply limited Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship is happening at this stage. The emergency stage is about finding ways to cut down activities rather than new ways to do things.

In this early stage, there are little coordinated actions across firms. This seems especially true in the Stavanger case. In a way, the lack of coordination reflects that small firms in a fragmented industry have limited resources and must focus on their performance and survival (Elvekrok et al., Citation2022). That tourist firms turn “inwards” and become more self-sufficient can be seen as a natural response to a crisis. Networking and cooperative linkages among tourist firms result from the capabilities that individual firms possess and the need for complementary inputs found in other cooperating firms (Tremblay, Citation1998). However, in times of crisis, the economic rationale (e.g. the market demand) for this cooperation often disappears, and firms refocus attention on their immediate needs for their own survival. Adjusting operations and costs are often the only levers of control available for firms during this stage.

In the crisis's intermediate phase, the cases indicated stronger signs of Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship in the industry. In this stage, many firms tried to adjust or recalibrate their offerings to reach existing or new markets during the difficult situation. Innovations in the technology domain included digital solutions like online ordering, check-in, and digital conferences. These digital innovations made the consumption and experience of tourist products safer and more accessible in a pandemic environment (Gutierriz et al., Citation2023). This account of responses during these different phases mirrors what was detailed in Seeler et al. (Citation2021) study about Norwegian SMEs during COVID-19.

However, in the two case studies, the extent of innovation and renewal was limited. The opportunity space for change was limited by firms’ resource constraints and most firms undertook relatively small-scale adaptations. Dyreparken, the joint zoo, theme, and amusement park, represented an exception to this observation. The management team in Dyreparken rethought more fundamentally how they could provide their products and experiences to visitors in these adverse conditions. The fact that many of the changes they undertook became permanent in their offerings and operations also after the pandemic is a testimony to the adaptability the organization demonstrated during COVID-19. The change agency exerted by Dyreparken must be seen as a result of its solid organizational capabilities that expand its opportunity space for change (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020).

Next, the institutional entrepreneurship observed in the two case studies was limited. In the Stavanger case, the local municipality offered little direct support to the tourist industry. In both regions, the local authorities are involved in destination development, but in terms of crisis management during the pandemic, they had limited support to offer, at least in Stavanger. The exception in Kristiansand was that the only way Dyreparken could stay open and receive visitors during COVID-19 was with the active cooperation of local authorities.

At a national level, support from the state authorities was limited during the pandemic. As one respondent commented, there is no Ministry of Tourism in Norway, which implies that the needs of the tourist industry are not ranked the highest. Major export-oriented industries in Norway receive another level of governmental support. For example, the salmon aquaculture industry has received ample institutional support from national authorities during important crossroads and challenges, reinforcing the change agency in that industry (Sjøtun et al., Citation2022). More robust institutional support from national authorities could have improved the tourism industry’s preconditions for navigating the rough waters of COVID-19. However, it should be noted that additional grants, loans, and guarantees offered by Innovation Norway during 2020 and 2021 likely saved a number of firms in the tourism industry (OECD, Citation2022).

This leads us to a discussion of place leadership, the third part of the trinity of change agency. The fragmentation of the tourist industry meant that both firms’ individual responses and their coordinated responses were challenging to muster. The lack of coordination and leadership was apparent in the Stavanger case. At the same time, Kristiansand showed more destination-level coordination due to its unique network structure of collaboration with Dyreparken as a central node. This does not imply that the tourist industry in Stavanger in any way was “weaker” than in Kristiansand. Instead, the industry in Stavanger lacked a focal point, a “flag,” so to speak, to rally around.

This shows the importance of place-leaders in a tourism destination. As discussed previously, Dyreparken utilized its capabilities to become an integrated provider of a large variety of experiences and services that uses sophisticated digital platforms, revenue management systems, and an overall well-developed marketing apparatus. These capabilities align with the idea that place leaders should “possess a greater range and depth of assets – including commitment to advancing the region – than other actors” (Sotarauta et al., Citation2017, p. 212). Dyreparken partnered with local authorities to create the required external conditions (e.g. health permits) to make these initiatives happen. Even if the zoo and amusement park functioned as a focal point for coordination at the destination level, the place leadership should not be placed squarely at their feet. For example, the local health authorities understanding of the regional importance of the tourist industry also played an important role. This cooperation helps to explain why the Kristiansand tourism industry outperformed most other parts of the country during the pandemic (see and ). As such, the ripple effects from Dyreparken’s performance helped to cushion the impact of the pandemic on the tourist industry in Kristiansand.

The tourism industry structure constrains stakeholders’ degree of change agency. We have observed the fragmentation of the tourist industries as a crucial reason for this. As Tremblay (Citation1998) noted, the tourism industry does not produce well-defined commodities but rather heterogeneous products and services that sometimes act as complements and other times as substitutes. The uncertainty of dynamically shifting markets makes tourist firms avoid strong integration and instead opt for participating in coordination networks. As a result, the degree of change agency available at the system level, i.e. at the level of the tourist industry in a destination, will be affected by the level of integration in the coordination networks. Without any party with strong capabilities or resources to coordinate activities during adverse conditions, one can easily imagine these networks are less consequential during a crisis. For example, we could see that the DMO in Stavanger had little influence on actions during the early stages of the pandemic.

Groups of smaller tourist firms may wish to emulate Dyreparken’s solution when cooperating with common digital platforms. However, it is worth acknowledging that despite such cooperation, the groups of smaller interdependent firms face high coordination costs. This makes it challenging to exploit economies of scale and scope and, consequently, to foster dynamic capabilities (Elvekrok et al., Citation2022; Prayag et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, Dyreparken’s role as a place leader could result from primarily following its own agenda instead of acting out as a destination leader promoting collective goals for the region as a whole. This statement is supported by one interviewee’s worry: “Dyreparken’s scale can present challenges to other tourism actors in the region in a long perspective.”

Distinct starting points and trajectories of collective adaptation explain why the two regions’ tourist industries follow different paths in dealing with crises (Galesic et al., Citation2023). The DMOs can encourage and facilitate cooperation but by no means dictate it. The typically small size of tourist firms limits the capability to cooperate for destination development. Fragmentation complicates forging ambitious strategies at the destination level. The main concern is that firms rival for market shares instead of jointly developing the destination and increasing the market size. Nonetheless, the study shows that moderate change agency adopted by firms individually in response to crises still leads to some systemic changes through some levels of cooperation, the adaptation of new technology, and reorientation, although they can be more sophisticated.

Conclusion

This research explored the potential of crises as catalysts for path development within the tourism industry, studying Southern Norway’s Stavanger and Kristiansand regions. Recent shocks and events, in particular, the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic, have demonstrated how vulnerable tourism is to crises and, therefore, have ignited research on risk management and resilience in tourism destinations (Alvarez et al., Citation2022; Cró & Martins, Citation2017; Gössling et al., Citation2021). The concept of change agency from economic geography, where regional preconditions play a vital role, offers a lens to analyze the capacity for change and is adopted for this research (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). Examining these tourist destinations’ capabilities and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic provides valuable insights into factors that influence a destination's resilience and development during challenging times. The findings demonstrate that crises indeed can act as catalysts for path development in the tourism industry.

However, the findings also indicate systemic challenges for the tourist industry. While tourist firms all made efforts to adapt in times of crisis, the capability of coordinated response at the destination level was limited. Industry fragmentation weakens the capabilities for place leadership and Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship that underpin change agency. The Kristiansand case was a counterpoint by having a node, the key attraction in the region, that embedded such qualities and exerted a great deal of change agency during the crisis.

Our findings emphasize the importance of crises as catalysts for path development in the tourism industry, highlighting the need for practical stakeholder cooperation and acknowledging the impact of technological advancements and digitalization on industry resilience. These insights can inform future policy and decision-making, fostering a more resilient and adaptable tourism industry.

To further understand the tourism industry’s capabilities for change, future research should investigate more on the levers to strengthen networks, increase innovative capacity, and enable effective strategy at the destination level. This necessitates further understanding of how regional preconditions, such as industry structure and leadership, affect stakeholder collaboration during crises, including between government agencies, local businesses, and tourism organizations (Beritelli & Bieger, Citation2014). Additionally, future studies should assess the impact of technological advancements and digitalization on the resilience of the tourism industry during crises, offering insights into how new technologies can foster innovation and overcome challenges.

The insights gained from these illustrative cases will contribute to the academic discourse on change agency, industry resilience, and regional development. They will also inform policymakers and industry stakeholders in their efforts to promote sustainable growth facing unpredictable and challenging circumstances. By examining the factors influencing bounce back and bounce forward, this research paper seeks to provide valuable insights into fostering resilience and promoting sustainable growth in the tourism industry.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for detailed feedback and suggestions of two anonymous reviewers that have significantly enhanced the quality of our manuscript. The time and effort they have dedicated to reviewing our paper is appreciated. We also wish to extend our gratitude to Laura James and Henrik Halkier who put us on the path to change agency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alvarez, S., Bahja, F., & Fyall, A. (2022). A framework to identify destination vulnerability to hazards. Tourism Management, 90, 104469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104469

- Arthur, W. B. (2023). Economics in nouns and verbs. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 205, 638–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2022.10.036

- Baggio, R. (2010). Collaboration and cooperation in a tourism destination: A network science approach. Current Issues in Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2010.531118

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). 2 How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903053598

- Beritelli, P., & Bieger, T. (2014). From destination governance to destination leadership – defining and exploring the significance with the help of a systemic perspective. Tourism Review, 69(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-07-2013-0043

- Booyens, I., Rogerson, C. M., Rogerson, J. M., & Baum, T. (2022). Covid-19 crisis management responses of small tourism firms in South Africa. Tourism Review International, 26(1), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427221X16245632411872

- Boschma, R. A., & Frenken, K. (2006). Why is economic geography not an evolutionary science? Towards an evolutionary economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(3), 273–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbi022

- Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2018). Doing interviews (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Bristow, G., & Healy, A. (2014). Building resilient regions: Complex adaptive systems and the role of policy intervention. Raumforschung Und Raumordnung | Spatial Research and Planning, 72(2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13147-014-0280-0

- Brouder, P. (2020). Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760928

- Brouder, P., & Eriksson, R. H. (2013). Tourism evolution: On the synergies of tourism studies and evolutionary economic geography. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 370–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.07.001

- Cró, S., & Martins, A. M. (2017). Structural breaks in international tourism demand: Are they caused by crises or disasters? Tourism Management, 63, 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.05.009

- Dahles, H., & Susilowati, T. P. (2015). Business resilience in times of growth and crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 51, 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.01.002

- Del Chiappa, G., & Presenza, A. (2013). The use of network analysis to assess relationships among stakeholders within a tourism destination: An empirical investigation on Costa Smeralda-gallura, Italy. Tourism Analysis, 18(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354213X13613720283520

- Elvekrok, I., Veflen, N., Scholderer, J., & Sørensen, B. T. (2022). Effects of network relations on destination development and business results. Tourism Management, 88, 104402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104402

- Falk, M., Tveteraas, S. L., & Xie, J. (2021). 20 years of Nordic tourism economics research: A review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1833363

- Faulkner, B. (2001). Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism Management, 22(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00048-0

- Galesic, M., Barkoczi, D., Berdahl, A. M., Biro, D., Carbone, G., Giannoccaro, I., Goldstone, R. L., Gonzalez, C., Kandler, A., Kao, A. B., Kendal, R., Kline, M., Lee, E., Massari, G. F., Mesoudi, A., Olsson, H., Pescetelli, N., Sloman, S. J., Smaldino, P. E., & Stein, D. L. (2023). Beyond collective intelligence: Collective adaptation. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 20(200), 20220736. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2022.0736

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Grillitsch, M., Asheim, B., Isaksen, A., & Nielsen, H. (2022). Advancing the treatment of human agency in the analysis of regional economic development: Illustrated with three Norwegian cases. Growth and Change, 53(1), 248–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12583

- Grillitsch, M., Asheim, B., Isaksen, A., & Nielsen, H. (2022). Advancing the treatment of human agency in the analysis of regional economic development: Illustrated with three Norwegian cases. Growth and Change, 53(1), 248–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12583

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Grillitsch, M., Sotarauta, M., Asheim, B., Fitjar, R. D., Haus-Reve, S., Kolehmainen, J., Kurikka, H., Lundquist, K.-J., Martynovich, M., Monteilhet, S., Nielsen, H., Nilsson, M., Rekers, J., Sopanen, S., & Stihl, L. (2022). Agency and economic change in regions: Identifying routes to new path development using qualitative comparative analysis. Regional Studies, 57, 1453–1468. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2053095

- Gutierriz, I., Ferreira, J. J., & Fernandes, P. O. (2023). Digital transformation and the new combinations in tourism: A systematic literature review. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14673584231198414. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584231198414

- Hall, C. M. (2010). Crisis events in tourism: Subjects of crisis in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2010.491900

- Hall, C. M. (2017). Resilience in tourism: Development, theory, and application. Tourism, Resilience and Sustainability, 18–33. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315464053-2

- Hall, C. M., Müller, D. K., & Saarinen, J. (2008). Nordic tourism: Issues and cases (Vol. 36). Channel View Publications.

- Hall, C. M., & Page, S. J. (2016). Introduction: tourism in Asia: region and context. In The Routledge handbook of tourism in Asia (pp. 23–44). Routledge.

- Haugland, S. A., Ness, H., Grønseth, B.-O., & Aarstad, J. (2011). Development of tourism destinations: An integrated multilevel perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(1), 268–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.08.008

- Haven-Tang, C., & Jones, E. (2012). Local leadership for rural tourism development: A case study of Adventa, Monmouthshire, UK. Tourism Management Perspectives, 4, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2012.04.006

- Hristov, D., & Zehrer, A. (2015). The destination paradigm continuum revisited: DMOs serving as leadership networks. Tourism Review, 70(2), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-08-2014-0050

- James, L., Halkier, H., Sanz-Ibáñez, C., & Wilson, J. (2023). Advancing evolutionary economic geographies of tourism: Trigger events, transformative moments and destination path shaping. Tourism Geographies, 25(8), 1819–1832. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2023.2285324

- Kirzner, I. M. (1973). Competition and entrepreneurship. University of Chicago press.

- Koens, K., & Thomas, R. (2015). Is small beautiful? Understanding the contribution of small businesses in township tourism to economic development. Development Southern Africa, 32(3), 320–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2015.1010715

- Kurikka, H., & Grillitsch, M. (2021). Resilience in the periphery: What an agency perspective can bring to the table. In Economic resilience in regions and organisations (pp. 147–171). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-33079-8_6

- Lemmetyinen, A., & Go, F. M. (2009). The key capabilities required for managing tourism business networks. Tourism Management, 30(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.04.005

- Ma, M., & Hassink, R. (2013). An evolutionary perspective on tourism area development. Annals Of Tourism Research, 41, 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.004

- Martin, R. (2011). Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. Journal of Economic Geography, 12(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbr019

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2014). On the notion of regional economic resilience: Conceptualization and explanation. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(1), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu015

- McKercher, B. (2021). Can pent-up demand save international tourism? Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 2(2), 100020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annale.2021.100020

- Neffke, F., Henning, M., & Boschma, R. (2011). How do regions diversify over time? Industry relatedness and the development of new growth paths in regions. Economic Geography, 87(3), 237–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01121.x

- Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Evolutionary theorizing in economics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(2), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1257/0895330027247

- North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.97

- OECD. (2022). Norway. In OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2022, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/c41cef4a-en

- Page, S. J. (1995). Urban tourism. Routledge.

- Page, S. E. (2006). Path dependence. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 1(1), 87–115. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00000006

- Peters, M., & Kallmuenzer, A. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: The case of the hospitality industry. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1053849

- Prayag, G., Jiang, Y., & Chowdhury, M. (2023). Building Dynamic Capabilities and Organizational Resilience in Tourism Firms During COVID-19: A Staged Approach. Journal of Travel Research, 63(3), 713–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875231164976

- Qui Zhang, H., & Wu, E. (2004). Human resources issues facing the hotel and travel industry in China. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 16(7), 424–428. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110410559122

- Ritchie, B. W. (2004). Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 25(6), 669–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.004

- Rypestøl, J. O., Martin, R., & Kyllingstad, N. (2022). New regional industrial path development and innovation networks in times of economic crisis. Industry and Innovation, 29(7), 879–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2022.2082271

- Safonov, A., Hall, C. M., & Prayag, G. (2023). Non-collaborative behaviour of accommodation businesses in the associational tourism economy. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 54, 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.12.007

- Seeler, S., Høegh-Guldberg, O., & Eide, D. (2021). Impacts on and responses of tourism SMEs and MEs on the COVID-19 pandemic–the case of Norway. In Virus outbreaks and tourism mobility: Strategies to counter global health hazards (pp. 177–193). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80071-334-520211016

- Shen, J., & Chou, R.-J. (2022). Rural revitalization of Xiamei: The development experiences of integrating tea tourism with ancient village preservation. Journal of Rural Studies, 90, 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.01.006

- Singal, M. (2015). How is the hospitality and tourism industry different? An empirical test of some structural characteristics. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 47, 116–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.03.006

- Sjøtun, S. G., Fløysand, A., Wiig, H., & Zenteno Hopp, J. (2022). Multi-level agency and transformative capacity for environmental risk reduction in the Norwegian salmon farming industry. Frontiers in Human Dynamics, 4, 1062058.

- Sotarauta, M., & Beer, A. (2017). Governance, agency and place leadership: Lessons from a cross-national analysis. Regional Studies, 51(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1119265

- Sotarauta, M., Beer, A., & Gibney, J. (2017). Making sense of leadership in urban and regional development. Regional Studies, 51(2), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1267340

- Statistics Norway (SSB). (2023a). Statistics Norway database. Accessed September 2023.

- Statistics Norway (SSB). (2023b). Innovation in the business enterprise sector. Accessed September 2023.

- Tremblay, P. (1998). The economic organization of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(4), 837–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00028-0

- Trippl, M., Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., Frangenheim, A., Isaksen, A., & Rypestøl, J. O. (2020). Unravelling green regional industrial path development: Regional preconditions, asset modification and agency. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 111, 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.016

- Tveteraas, S. L., & Xie, J. (2021). The effects of Covid-19 on tourism in Nordic countries. In Globalization, political economy, business and society in pandemic times (pp. 109–126). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1876-066X20220000036011

- Weichselgartner, J., & Kelman, I. (2015). Geographies of resilience: Challenges and opportunities of a descriptive concept. Progress in Human Geography, 39(3), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513518834

- Xie, J., & Tveterås, S. (2020). Economic decline and the birth of a tourist nation. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(1), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1719882

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). SAGE.

- Zhang, D., Xie, J., & Sikveland, M. (2021). Tourism seasonality and hotel firms’ financial performance: Evidence from Norway. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(21), 3021–3039. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1857714