ABSTRACT

To combat rural socio-economic decline, second-home development is seen as a strategy for fostering rural development and mitigating decline across several regions in the Nordic. This scoping review aims to identify key themes in the literature to explore the broader impact of second homes on rural development. A systematic search strategy identified 46 English-language peer-reviewed articles and chapters. The analysis identified four overarching themes: ‘Restructuring rural areas,” “Population distribution,” “Perceptions of rural development,” and “Second-home owners as stakeholders.” Additionally, variables affecting impact were identified, confirming the imperative for context-sensitive studies.

The identified gap in understanding how second-home development affects local businesses and their innovative capabilities represents a paradox, given their crucial role in rural development. Addressing this gap requires integrating business-oriented perspectives, exploring themes such as knowledge transfer, linkages, sources for innovation, diversification, and barriers to business development. Recognizing the central role of the municipal level in rural development, this review calls for further research to elaborate on their multifaceted role. However, reliance solely on English-language peer-reviewed sources may overlook significant insights from non-English peer-reviewed literature and other types of literature, potentially limiting the scope of conclusions drawn.

Introduction

In several economically marginal rural areas in the Nordics, developing second homes, together with the tourism industry, is seen as a viable strategy to counteract socio-economic decline characterised by economic restructuring, unemployment, out-migration and an ageing population (Ericsson et al., Citation2022; Kauppila, Citation2009; Overvåg & Berg, Citation2011; Syssner, Citation2020; Velvin et al., Citation2013). Additionally, it is viewed as a driver of economic development and diversification (Koster, Citation2019). However, several challenges related to the impacts of rural tourism have been identified, such as economic leakage and low spillover, low-paid, low-skilled and seasonal or imported labour, limited investments, firm creation and employment due to small scale and small returns on investments (Koster, Citation2019; Rye, Citation2011). This socio-economic decline, which has been going on for decades, is not limited to certain rural areas (Long & Lane, Citation2000) but is more like a common trait in developed countries, which is estimated to continue (Heleniak & Sánchez Gassen, Citation2020).

Research on how second-home development affects local economies has mainly focused on the urban – rural transfer of capital, and there is a substantial body of literature on the direct economic contribution of second-home tourism to local economies, identifying the construction and maintenance services and the retail industry as the primary beneficiary industries (Czarnecki, Citation2018; Marcouiller et al., Citation1996; Schmallegger et al., Citation2011). Moreover, research has explored aspects related to the impact on employment growth and property prices (Hoogendoorn & Visser, Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2011; Sheard, Citation2019; Visser, Citation2004). Nonetheless, studies have indicated uncertain benefits of second-home development at the municipal level (Borge et al., Citation2015; Ellingsen, Citation2017), underscoring the critical role of effective planning (Hajimirrahimi et al., Citation2017; Rye, Citation2011). These contributions will vary due to differences in second-home landscapes, their characteristics (Back, Citation2021; Farstad & Rye, Citation2013; Kauppila, Citation2009; Müller et al., Citation2004), the two development phases, construction and usage (Arnesen & Teigen, Citation2019; Arnesen et al., Citation2022; de Oliveira et al., Citation2015), and the level of maturity (Rye, Citation2011). This highlights the need for more context-sensitive research (Back, Citation2021; Farstad & Rye, Citation2013).

However, how this urban – rural transfer impacts local businesses, especially the influence on their innovative capability, has received limited attention in scholarly discourse and appears to be an underexplored field. Exceptions are Nordbø (Citation2014), who addresses the potential role of second-home owners as competence brokers for rural entrepreneurship and innovation, Rantanen and Czarnecki (Citation2023), who address local-development roles of second-home owners and the potential impact of the different roles identified, and Robertsson and Marjavaara (Citation2015), who address the seasonal buzz second-home users represent. The latter argue that this buzz may boost innovative capability. Following this last argument, Carson et al. (Citation2016), based on the framework of community capital (Emery & Flora, Citation2006; Flora, Citation2004; Flora et al., Citation2004) which Moscardo et al. (Citation2013) linked to the new mobilities paradigm and tourism industry, examine the potential contribution to local innovation capacity and socio-economic development of rural areas by various temporary mobile populations. In line with Nordbø (Citation2014) and Robertsson and Marjavaara (Citation2015), Carson et al. (Citation2016) find limited impact on the local innovation capacity and knowledge transfer and limited exploitation of the possibilities due to temporality, the lack of platforms, arenas and facilitators and the fact that second-home owners may deter socio-economic development to preserve the rural idyll, thus contributing to a lock-in. Noticeably, the four studies apply the perspective of second-home owners (Carson et al., Citation2016; Nordbø, Citation2014; Rantanen & Czarnecki, Citation2023; Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015). Moreover, Nordbø’s (Citation2014) and Robertsson and Marjavaara’s (Citation2015) studies rely on empirics from small, remote peripheral communities.

Intrigued by the fact that second-home development and tourism in some areas are considered a means for promoting prosperous rural development (e.g.Ericsson et al., Citation2022), the claims of Schmallegger et al. (Citation2011) that the impacts of various temporary populations are not well understood and by Müller and Hoogendoorn (Citation2013, p. 366) “that the role of second-home phenomena for regional development is not fully understood”, together with the apparently limited interest by scholars on the impact on local businesses, calls for a rigorous review of empirical studies to establish an evidence base for future research. Despite its utility, and to the best of my knowledge, a comprehensive review explicitly investigating the impact of the second-home phenomenon on rural development remains absent in the scholarly literature. To address this gap and complement previous reviews (Hall, Citation2014; Kauppila et al., Citation2009; Müller & Hall, Citation2018), a scoping review was conducted to scrutinise the current scholarly state of the field and identify key themes within the literature, guided by the following research questions: What is the range and nature of the studies? What are the main themes, and how are they studied? What perspectives are applied? Within the frame of this review, what are the gaps and areas for future investigation?

Method, design, and data analysis

To capture a broad and comprehensive coverage of the relevant literature, a scoping review was conducted (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Munn et al., Citation2018; Paré et al., Citation2015; Rumrill et al., Citation2010; Sutton et al., Citation2019). Inspired by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), Paré et al. (Citation2016), Paré et al. (Citation2023) and Snyder (Citation2019), and to enhance the quality of the review process, a systematic search strategy was developed, to minimise the risks of errors, biases or misinterpretations and transparency to ensure the internal and external reproducibility of the process (Paré et al., Citation2016), contributing to the rigorousness of the review process and, hence, the results (Snyder, Citation2019). The review process consisted of three phases: identifying keywords, identifying and screening the literature and analysing, each documented in a review protocol.

Identification of keywords

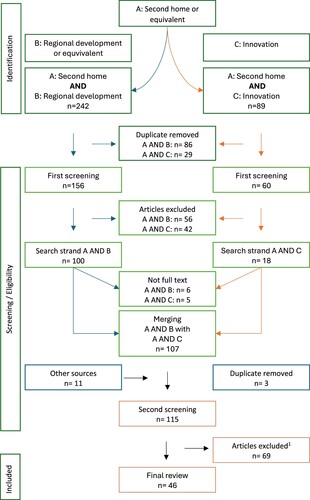

Based on the research questions, a former literature review (Kunnskapsstatus fritidsboliger i Innlandet [Second Homes – State of the field], 2021), and assisted by a qualified librarian, relevant keywords covering the scope of the review were identified, and three broad search strings (A, B, and C) were developed (), reflecting a repetitive issue within second-home research where there is neither a single unified term nor a definition used (Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017; D'Emery et al., Citation2018; Mowl et al., Citation2020; Visser, Citation2004).

Table 1. Search string.

Identification and screening of the literature

To identify the body of literature within the tree search strings (A, B and C), a Boolean online search was conducted in January 2023 in four bibliographic databases: Web of Science, Scopus, Academic Search Complete and Business Source Ultimate, delimited to the period 2000 up and including 2022. Within strings A and B, four sub-searches were conducted (a – d in ) before combining them with the Boolean operator OR. The results from A, B and C were combined with the operator AND before exporting the results to Endnote, respectively A AND B (n = 242 studies) and A AND C (n = 89 studies).

Duplicates within the two strings were identified and excluded. The search strategy, specifying the steps with sub-results, is presented in . To gauge the relevance of the studies, a strict set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was developed (), and guiding the first screening, the title, abstract and keywords were assessed for relevance by the author, excluding 56 and 42 studies within the two search strings.

Table 2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Prior to the full-text screening (second screening), the results from the two search strings were merged (n = 107), and duplicates were removed (n = 3) (). Due to limited time resources, no manual search was conducted. However, being aware of this weakness, particular attention was paid throughout the screening process to identify missed literature, resulting in seven articles entering the process.

The second screening excluded 69 articles, and a final sample of 46 research studies entered the analysis.

Analysis

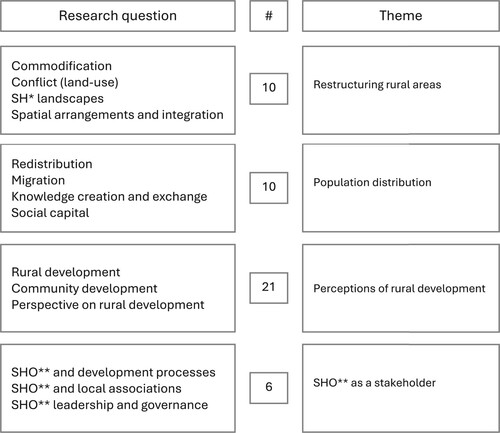

The final sample of research studies underwent coding in Nviov based on an in-depth analysis of the stated the aim and research questions. Alongside 14 distinct codes, an additional seven codes related to the broad impact of second homes were identified. Following a comprehensive analysis, the 14 codes were aggregated into four overarching themes (), in a process facilitated by Excel. As the categorisation is based on each study’s aim(s) and research questions, some studies may be classified into multiple themes.

Limitations

There are two main limitations to this review. The first is the fact that the review, except the identification of the keywords and development of the search string, was conducted by only one reviewer, which must be taken into consideration concerning the findings and analysis. Second, the stringent inclusion-exclusion criteria developed are based on considerations of acceptable trade-offs related to the validity of the study. The criteria developed ensured the identification and inclusion of high-quality English language peer-reviewed literature but excluded non-English peer-reviewed literature and other types of literature for which their contribution is not known, possibly excluding relevant findings and insights.

Results

As it is impossible to present an in-depth analysis of all the included articles, a brief descriptive overview of the findings is presented in .

Table 3. A descriptive overview of findings

It is noteworthy that, despite the review process encompassing 44 journal articles and two book chapters, only three studies result from the merged search string “second home” and “innovation” (García-Andreu et al., Citation2015; Nordbø, Citation2014; Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015). However, “innovation” is mentioned in some of the other studies; according to one respondent, second-home tourism is less innovative compared to the tourism industry (D'Emery et al., Citation2018), while in the studies of Kindel and Raagmaa (Citation2015) and Ellingsen (Citation2017), they mention increased mobility and temporary populations as a source of change agents who may foster local growth and development, creativity and innovation. Nordin and Marjavaara (Citation2012, p. 296) see second-home owners as a source of competence and “if used the right way can lead to business opportunities and improved innovation capabilities for local firms”. The common denominator is that innovation is mentioned only superficially but may serve as a prelude to further elaboration.

The studies were conducted in 19 countries across four continents, predominately in Europe, and published in 33 journals. About half of the studies applied a quantitative methodology, while a case study approach was used in 34 studies. Among these, 19 were comparative studies, and 15 were single case studies. In 25 studies, second-home owners were one type of respondent, accounting for all respondents in seven, making second-home owners the most predominant type of respondent. In contrast, in only eight studies, representatives of local businesses or business associations were one type of respondent.

Substantial results

The seminal question raised by Coppock (Citation1977), whether the second home is a curse or a blessing, serves as a departure point, as this binary question also is reflected in research on the impact of second-home development, which, according to Hoogendoorn and Visser (Citation2010b, p. 2011), Kindel and Raagmaa (Citation2015) and Terzić et al. (Citation2020) tend to take one of two perspectives. One focuses on the “blessings’, like economic advantages within retail and construction industries (Rye, Citation2011), seasonal population increases which may result in the use of dwellings that otherwise would be left vacant (Overvåg & Berg, Citation2011) and represent a seasonal buzz (Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015), and knowledge transfer (Nordbø, Citation2014; Nordin & Marjavaara, Citation2012; Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015) that may improve the innovative capability (Nordin & Marjavaara, Citation2012). Conversely, the second focuses on the “curse”, like the displacement of residents as the housing prices rise, conflicts among residents and second-home dwellers (Hoogendoorn & Visser, Citation2010b, Citation2011; Kindel & Raagmaa, Citation2015; Terzić et al., Citation2020), economic instability due to the seasonal fluctuation in residents (Hiltunen, Citation2007), reduced income potential due to “empty beds’ (Norris & Winston, Citation2009; Palmer & Mathel, Citation2010) and villages turning into seasonal ghost villages (Hajimirrahimi et al., Citation2017). Further enriching this binary perspective is the viewpoint presented by Hoogendoorn and Visser (Citation2015), who argue that posing normative questions about whether second homes should exist or not may not be particularly helpful for understanding the changes occurring in rural geographies. Instead, they advocate for an understanding of second-home geographies as a basis for realising beneficial outcomes and mitigating adverse impacts, aligning with the call for more context-aware second-home research (Back, Citation2020).

A study of the local impacts of second-home tourism in a Mediterranean Spanish destination identified several types of stakeholders: national and foreign second-home tourists, local population, foreign labour immigrants, local second-home construction entrepreneurs, local hotel industry and catering entrepreneurs, local agricultural entrepreneurs, local commercial entrepreneurs, local politicians, municipal officers, local media and local experts (García-Andreu et al., Citation2015). In addition to the stakeholders in situ, developing second homes may attract external actors (Overvåg, Citation2010), representing extra-local linkages and an additional source for amenity-led change and rural restructuring (Fialová & Vágner, Citation2014; Wu & Gallent, Citation2021). This new setting with local and external actors, their linkages and their pursuit of profit impacts the local configurations of power and may alter both the distribution of benefits and disadvantages among the actors and the power resources they control (e.g. capital and land use) (Overvåg, Citation2010; Rye, Citation2011). On the other hand, these external actors and their linkages may represent access to new knowledge, knowledge exchange and knowledge creation (Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015; Wu & Gallent, Citation2021), increasing bridging social capital (Kindel & Raagmaa, Citation2015; Rye, Citation2011; Winkler et al., Citation2015).

Economic impacts at the municipal level of second-home development are not clear-cut; on the one hand, such development can increase public revenues through taxes, charges and other fees directly from the second-home owners and indirectly through sustained employment and activities in the municipality. On the other hand, it imposes costs related to the provision of healthcare services (Ellingsen, Citation2017), as well as the development, management and maintenance of infrastructure related to the second homes (e.g. water and sewage and waste disposal) (Adamiak et al., Citation2017). Rye (Citation2011, p. 264) stated that “the costs of adjusting the infrastructure of public services to meet the demands of the second home populations may exceed these income sources”.

The municipal level and its role(s) and the local configuration of power change in line with the different phases of development, from the initial phase via the construction phase to the management phase. In the initial phase, when the risk is high, the municipal level serves a role as a catalyst for development, while later, as the attractiveness of the area increases together with the pursuit of profit, their role is strengthened, and they “can demand investment in community infrastructure in exchange for granting development permission” (Overvåg, Citation2010, p. 14). However, on the other hand, this altered configuration of power, together with a planning practice wherein several decisions are determined early in the process, poses challenges related to the involvement of pertinent stakeholders (Overvåg, Citation2010).

A case study by Hajimirrahimi et al. (Citation2017) that set out to identify the impacts of second-home development on rural development in a village in East Iran found that, due to a lack of planning and poor management, the positive impacts were less than the negative impacts, fostering a need for measures to change this bias. These findings align with the study of non-metropolitan counties in the US by Winkler et al. (Citation2015), which found that second-home development correlates positively with environmental conditions and negatively with social and economic conditions. Looking to Ireland, Norris and Winston (Citation2009) found that the social and economic impacts vary due to the local context, while the environmental impact and the impact on the national economy are negative. Miletić et al. (Citation2018), on the other hand, found a positive correlation between the density of second homes and several indicators of local socio-economic development in municipalities and towns in Croatia with a population of less than 15,000 and correspondingly for the tourism industry, but that a combination of intensive development of the two, in addition, produced a synergy effect.

Other studies take a narrower approach, such as investigating the economic effects of second homes (de Oliveira et al., Citation2015; Guisan & Aguayo, Citation2010; Hoogendoorn & Visser, Citation2010b, Citation2011; Mottiar, Citation2006; Perles-Ribes et al., Citation2018; Sheard, Citation2019; Velvin et al., Citation2013), environmental impacts (Hiltunen, Citation2007), second-home users as a potential new group of customers (Sievänen et al., Citation2007; Tangeland et al., Citation2013) or if second-home ownership triggers later retirement migration (Marjavaara & Lundholm, Citation2016).

In addition to these broad findings related to the impact of second homes, the analysis of the 46 identified articles and book chapters resulted in the emergence of four distinct themes: “Restructuring rural areas’, “Population distribution”, “Perceptions of rural development” and “The second-homes owner as stakeholders’, which reflects the comprehensive approach chosen for this review.

Restructuring rural areas

Due to a change in the relative exchange value of land, some amenity-rich rural areas have transformed (Miletić et al., Citation2018; Overvåg & Berg, Citation2011; Winkler et al., Citation2015; Wu & Gallent, Citation2021) from a site of production of commodities by the primary industries to a commodified product in itself (e.g. Kauppila, Citation2009; Overvåg, Citation2010; Rye, Citation2011; Van Auken, Citation2010), resulting in areas developed for tourism and second homes being “sites of simultaneous tourism space production and consumption” (Visser, Citation2004, p. 259).

Overvåg and Berg (Citation2011) found that conflicts between second-home owners and residents are a result of shared spaces used for different purposes and that, on one hand, a spatial separation between first – and second-home areas contributes to fewer conflicts, but on the other hand, that the number of conflicts is also related to the number of second homes in the area. Thus, spatial separation may reduce the level of conflict (Overvåg & Berg, Citation2011). However, in a study of 17 villages in Poland, Soszyński et al. (Citation2018) found that spatial separation reduced the quality of public spaces and the integration of residents and second-home users. The situation in the UK, where “the second-home owners compete for the same housing stock as the permanent rural population” (Rye, Citation2011, p. 265), is quite the opposite, resulting in a higher level of conflict. In general, the level of conflict may depend on the level of maturity of the second-home destination, that is, the level of commodification, privatisation and marketisation (Rye, Citation2011). A study by Ellingsen and Nilsen (Citation2021) found, based on a case study of three rural municipalities in Norway, that their approaches to place development or “place-making” were quite different. A paradox of second-home development is that it, to some extent, alters the rural idyll and the quality of the place and space that was the original attraction (Rye, Citation2011).

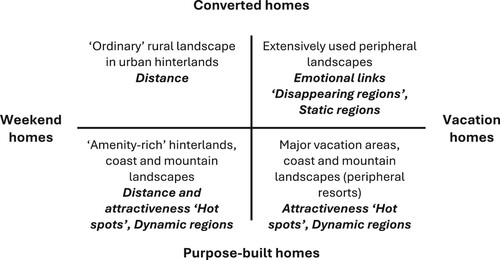

The potential for such transformation of rurality varies and is related to the distance from a large population centre and the attractivity of the in situ amenities. In short, when “the distance from a permanent home to a second home increases, the attractiveness of the second home area should also be at a higher level; otherwise, the destination closer to the primary home will be chosen” (Kauppila, Citation2009, p. 4). Based on this space – time dimension, Kauppila (Citation2009) developed a model based on two continuums: (1) distance from the first home and (2) type of second home, either purpose-built or converted home (see ). The first, as an indicator of use as a weekend home, indicates “used-often”, and vacation home “used-seldom”; the latter indicates the area’s attractivity. The model resulted in four different second-home landscapes, which, according to Müller (Citation2004, p. 247), “can be considered as a marker for various other developments”, identifying “disappearing regions’ as peripheral areas with both population and economic decline resulting in a conversion of first to second homes. Quite the opposite is the “hot spot” region, found either in the amenity-rich hinterland of cities (Müller, Citation2004) or in attractive and well-developed vacation destinations with high touristic elements (Kauppila, Citation2009). The various landscapes have different impacts on the host community (Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017), and the host communities have different capacities to respond to the impacts.

Figure 3. The space – time dimensions of second-home types and the characteristics of the landscapes (Kauppila, Citation2009; based on Müller et al., Citation2004).

Population redistribution

In line with land use, the basis for peripheral development has transformed from being based on the exploitation of natural resources to being increasingly a result of the economic and socio-cultural impacts of different types of temporary mobile populations and their specific impacts (Pitkänen et al., Citation2017), where second-home users are one type.

Temporary population redistribution is a challenge because it is invisible in census data. This challenge is not new and is a consequence of administrative practices based on static and discrete definitions of residence that do not acknowledge a mobile lifestyle (Adamiak et al., Citation2017).

This invisible population, the total number and how it varies seasonally has significant practical implications for rural policy and planning. First, census data are the basis for national tax redistribution. Second, no official statistics on when and for how long each second home is in use and by how many persons represent a substantial challenge for the municipality, both as a service provider to residents and temporary populations and as being responsible for the infrastructure in general (Adamiak et al., Citation2017), risking a planning mismatch (Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017). In addition, one study found that second-home users are “invisible” at the local administrative and policy level by not reflecting their presence, needs and priorities in municipal plans and strategies nor encouraging their participation (Kietäväinen et al., Citation2016).

To reveal the actual spatial patterns of population development in Finland and by introducing two alternative measures of the population (seasonal and average population), Adamiak et al. (Citation2017) found, in contradiction to the official documented urbanisation, that the population dynamics are more complex, showing an increased dispersion of temporary population due to the growth in the number of second homes. Thus, while politicians aim to counteract urbanisation by focusing on increasing permanent settlement in rural areas, the mobility related to the usage of second homes ensures a temporary but substantial redistribution of the population, for example, in Norway (Ellingsen, Citation2017), Sweden (Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017) and Finland (Adamiak et al., Citation2017; Pitkänen et al., Citation2017).

On the other hand, the temporary influx of people or human capital to rural communities may enrich these communities by bridging and linking social capital (Kindel & Raagmaa, Citation2015; Wu & Gallent, Citation2021), representing a seasonal buzz (Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015) and a possible knowledge transfer (Nordbø, Citation2014; Nordin & Marjavaara, Citation2012; Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015), thus increasing the innovative capabilities of the local entrepreneurs and businesses (Nordin & Marjavaara, Citation2012). Nevertheless, the lack of platforms or facilitators has resulted in limited knowledge transfer and limited exploitation of the linkage and bridging possibilities that second-home owners may represent (Nordbø, Citation2014; Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015).

Perceptions of rural development

Various stakeholders within a limited rural area may have different perceptions of rural development (D'Emery et al., Citation2018; Farstad & Rye, Citation2013; Fialová & Vágner, Citation2014; Fialová et al., Citation2018; García-Andreu et al., Citation2015; Overvåg & Berg, Citation2011; Park et al., Citation2019; Rye, Citation2011), which may be a source of conflict. Overvåg and Berg (Citation2011) found that residents generally welcome rural development that enhances the community’s viability, while second-home owners seek to preserve the rural idyll. In a study of villages in the Czech countryside, increased length of ownership decreased the perception of second-home users being allochthonous elements, which earlier used to bring about social conflicts (Fialová & Vágner, Citation2014; Fialová et al., Citation2018).

Nevertheless, according to Farstad and Rye (Citation2013), this dichotomous perception of either rural development or preservation is too simplified, arguing for a more nuanced approach, claiming that “intra-group differences may be more marked and more analytically relevant than inter-group differences” (p. 43). This finding is in line with Rye (Citation2011, p. 263), when elaborating on the residents’ views on second-home development, finding that “[…] those with direct economic interests in the second-home sector are most positive towards further development”, and that the residents with a positive attitude outnumber the negative. Farstad and Rye (Citation2013, p. 49) found that residents and second-home users are “[…] united in the “Not in my backyard” line of logic” but stress the contextual setting in the analysis, e.g. if “their” perception of backyard differs, likewise with perceptions of rural idyll, and in addition, if the rural area is particularly fragile, “it is conceivable that residents may be easier disposed to accept that new economic opportunities are developed at the expense of the rural idyll in their “backyards”" (p. 50).

In a study of the perceived importance of development and preservation for community quality of life among residents, Park et al. (Citation2019) found that community growth rate was a stronger predictor for attitude towards pro and con rural development compared to the type of resident, divided into long – and short-time residents and second-home owners. This finding is in line with Rye (Citation2011), which found that a high density of second-home users in an area resulted in higher resistance by residents to further development, while prior, in the development phase, with a high growth rate the opposite, while Kindel and Raagmaa (Citation2015), in a comparative case study of two coastal municipalities in Estonia, found that length of time of ownership was an important variable reducing potential conflicts related to development. These findings underpin the call for contextual awareness by Farstad and Rye (Citation2013).

In a study from Ireland, Mottiar and Quinn (Citation2003) found that the second-home owner as a group was empowered and managed to alter a local development plan, the reason being the particular characteristics of the second-home owners, their connection with the area and their relationship with the local elite, which is in line with the findings in a study from Estonia (Kindel & Raagmaa, Citation2015).

Second-home owners as stakeholders

Second-home owners and users are one of several stakeholders at a destination, and engagement and involvement in local life vary.

In a study from Sweden, Nordin and Marjavaara (Citation2012) found that second-home owners engaged in local associational life, common land associations in particular, as property owners are obliged to be members if infrastructure or other resources are shared. Through this membership, second-home owners participate in local public consultation processes in line with local stakeholders. Through this engagement, they may influence public consultation and contribute to the association’s development. They found that second-home owners who were members tended to be more socioeconomically influential and had higher educational and income levels compared to non-member second-home owners. This aligns with the conclusions of Overvåg (Citation2010) in a Norwegian study wherein second-home owners, despite lacking the right to vote, assert their influence through well-organized and engaged participation in matters of interest. Nordin and Marjavaara (Citation2012) point to the fact that second-home destinations are attractive and consequently have other resources and possibilities, though only temporary, compared to other rural destinations without equivalent resources. They state that the aim should be to secure engagement from second-home owners for rural development by turning the second-home owner into a local patriot (Nordin & Marjavaara, Citation2012).

Conversely, second-home owners having resources and powerful relationships may represent a strong alliance that may alter local development plans, possibly due to the “Not in my backyard” syndrome, as in Courtown, Ireland (Mottiar & Quinn, Citation2003). According to Kindel and Raagmaa (Citation2015), the involvement of second-home owners in local leadership and governance is underexplored, and they argue that the integration of second-home owners may stimulate innovativeness and competitiveness due to interpersonal relations and increased social capital. However, the synergies may also work in the opposite direction, concluding that “culturally heterogeneous places need particularly skilled leadership and wider involvement of interest groups in the decision-making processes” (p. 243).

The obligation by second-home owners to pay estate tax to the host community while not being allowed to vote in elections at the municipal level nor to be elected as a representative in the municipal council (Kietäväinen et al., Citation2016; Overvåg, Citation2010) is a recurring issue questioning the representativity of democracy, especially in areas where there is a skewed ratio of second-home owners compared to the number of residents. In this setting, second-home owners are treated as external actors. In a study by Kietäväinen et al. (Citation2016) of municipal administration experiments attempting to include all types of residents in Finland by establishing Communal District Committees authorised to enhance the provision of services and development of the district within a budget given by the municipal council, they found that there is “a major challenge to find inspiring means to encourage second-home owners to be active and participatory” (p. 164) and to identify engaging topics for both the residents and second-home owners, mentioning fishing as a topic in common.

Discussion

This paper, categorising four main themes (“Restructuring rural areas’, “Population distribution”, “Perception of rural development” and “The second-home owners as stakeholders’), provides an overview of the broad nature, extent, and range of peer-reviewed empirical research on the impact of second homes on rural development from the new millennium up to and including 2022.

The uneven distribution of studies, with only three out of 46 studies resulting from merging the search strings “second home” and “innovation” while the remaining 43 studies, from merging with rural development, may reflect a shift in the conceptualisation of development from a formerly unidimensional emphasis on economic indicators to a more comprehensive concept encompassing not only economic dimensions but also environmental and social aspects (Tomaney, Citation2017). Consequently, this broader conceptualisation extends beyond the narrower scope of the term “innovation” as such. Another possible explanation may be the revealed bias in the applied perspectives used in the studies, where the perspective of the second-home owner predominates in comparison to other perspectives, e.g. of business owners () or a combination of the two.

In contrast, no single study applies the perspective of businesses as a primary approach, which is a surprising finding because second-home development is seen as a strategy for promoting prosperous rural development and counteracting decline (Ericsson et al., Citation2022), encompassing, for example, industrial diversification, job creation, innovation of new products, markets and services, and population growth. In such a setting, this lack of interest is a paradox, since the business’ performances are essential for regional development, which, according to (Pike et al., Citation2017, p. 110) can be seen as the ability of actors (e.g. businesses) to “produce, absorb and utilise innovations and knowledge through processes of learning and creativity”, though acknowledging that the precondition for innovation differs, making firms in rural areas more dependent on external linkages (Eder, Citation2019; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2016, Citation2017) and collaboration (Grillitsch & Nilsson, Citation2015). Related to the second-home phenomenon, this aspect is noteworthy, as second-home users may represent external linkages and a segment of demanding customers, which may enhance businesses’ innovative capabilities (Nordin & Marjavaara, Citation2012) and the community’s overall innovative capacity. In this setting, the study of Robertsson and Marjavaara (Citation2015) is interesting, introducing the concept of seasonal buzz, departing from agglomeration theory, which, in contrast to the terms buzz and global pipelines (Bathelt et al., Citation2004), is related to the knowledge transfer generated by temporary mobility at leisure destinations rather than face-to-face contact in a professional context. However, despite the aforementioned, and despite the second-home owner being highly educated and having managerial and entrepreneurial experiences (e.g. Müller, Citation2004), and their expressed willingness to participate in community development and the development of local businesses (Nordbø, Citation2014), the empirical studies indicate a limited influence on innovation capability and capacity, knowledge transfer, and the exploitation of linking and bridging opportunities (Nordbø, Citation2014; Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015), the reason, from the second-home owners’ perspective, is attributed to the absence of suitable platforms, arenas and facilitators (Carson et al., Citation2016; Nordbø, Citation2014; Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015). Another is the endeavour of second-home users to preserve the rural idyll and, thereby, a lock-in (Carson et al., Citation2016; Farstad & Rye, Citation2013).

Against this backdrop, regarding second-home development as a means for fostering prosperous rural development, two conditions are identified: the context and the perspective of the studies, warranting further elaboration. The empirical data from previous studies, gathered in exceedingly small and remote peripheral areas in the Nordics, characterised by fragile industrial structures (Nordbø, Citation2014; Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015), ought to be supplemented with studies from regions with more advanced economic activities, e.g. second-home landscapes within the weekend zone, while the predominant perspective of second-home owners in prior studies (Nordbø, Citation2014; Robertsson & Marjavaara, Citation2015) ought to be enriched with business-oriented perspectives emphasising the potential impact of second-home development and how to optimise its benefits for local entrepreneurs and businesses, including enablers and barriers. Furthermore, Müller (Citation2019) proposes an intriguing shift in perspective within studies on rural development with the concept of infused tourism. This suggests a departure from researching the impacts of second homes to studying second-home development as a catalyst or agent of change for rural development. This perspective resonates with the context of this paper, which views the development of second homes and tourism as a means for promoting prosperous rural development.

The review identified the multifaceted responsibilities of the municipality. Beyond its developmental role, the municipality is a political actor, planning authority and service provider. This is reflected in the findings, and the analysis identifies seven challenges related to: (1) the uncertain benefits of second-home development (Ellingsen, Citation2017); (2) steering development through effective planning and to realise the positive impacts of second-home development while limiting negative ones (Hajimirrahimi et al., Citation2017; Rye, Citation2011); (3) the missing statistical data for the actual distribution of the population; (4) the change in power distribution (Overvåg, Citation2010; Rye, Citation2011); (5) realizing community benefits from the developers in exchange for granting permission (Overvåg, Citation2010); (6) secure the influence and involvement from stakeholders, despite the forming of what Gill (Citation2000) calls a “growth machine” reducing the influence of the other stakeholders (Overvåg, Citation2010); and (7) the representativity of democracy, especially in areas where there is a substantial amount of second-home owners relative to the number of residents not being allowed to vote in elections at the municipal level nor be elected as a representative in the municipal council (Kietäväinen et al., Citation2016). These challenges are all relevant themes that should be further elaborated upon.

This review reveals a distinct lack of nuance and detail related to the context of the studies. About half of the studies did not provide a definition of a second home, and even though several mention heterogeneity (Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017; Mowl et al., Citation2020), second homes are often seen and analysed as a unitary category (Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017). Accordingly, the same prevails for the second-home owners being broadly summarised as highly educated and coming from relatively affluent groups (Müller, Citation2004; Nordbø, Citation2014; Nordin & Marjavaara, Citation2012; Overvåg & Berg, Citation2011; Sievänen et al., Citation2007), with less focus on the second-home users (Sievänen et al., Citation2007) outnumbering the owners.

Furthermore, related to the development of the second-home destination itself, the findings, when studying the different perceptions of rural development, imply that the maturity of the destination, together with the ratio of second-home users to residents, affects the results (Farstad & Rye, Citation2013; Fialová & Vágner, Citation2014; Fialová et al., Citation2018; Kindel & Raagmaa, Citation2015; Rye, Citation2011). Only Rye (Citation2011) explicitly mentioned the maturity of the destination as a variable, pointing to the findings that the residents are positive to further development of second homes if there is a high growth rate (in the development phase) and negative if there is a high density of second-home users (usage phase), while others (Fialová & Vágner, Citation2014; Fialová et al., Citation2018; Kindel & Raagmaa, Citation2015) by presenting findings that increased time of ownership reduces the potential conflicts, indirectly imply that a mature destination reduces potential conflicts.

Even though there is little emphasis on specific characteristics, it is evident that the studies include various rural and peripheral areas, indicating that the terms (rural and peripheral) are ambiguous and imprecise, complicating the comparison of the results due to the different spatial contexts (Eder, Citation2019; Glückler et al., Citation2022). Several scholars point to the need for more context-aware research (Back, Citation2020), and that the “contextual significance also concerns the transferability of our findings, which invites contextual sensitivity” (Farstad & Rye, Citation2013, p. 50). Moreover, as Back (Citation2020, p. 1339) states, “this paper argues against one-size-fits-all solutions in favour of recognising the heterogenous geography of second-home impacts”.

The need for context-aware research also has implications for the choice of methods. Some of the included studies are based on large-scale population data (Ellingsen, Citation2017; Miletić et al., Citation2018; Perles-Ribes et al., Citation2018; Rye, Citation2011; Sievänen et al., Citation2007; Tangeland et al., Citation2013; Winkler et al., Citation2015), presenting results representing national averages without being able to take the local-level political, social and cultural context into account, implying the need for more qualitative designs and case-oriented methodological designs (Rye, Citation2011). Moreover, this contextual sensitivity is essential in case studies to ensure the transferability of the findings and enable comparison, as a lack of nuance and detail related to the context complicates the comparison of findings and may be the reason for somewhat contradicting results (e.g. Norris & Winston, Citation2009; Winkler et al., Citation2015). Future work investigating the second-home phenomenon must address this context sensitivity in the choice of method and analysis to enable transferability and to identify commonalities, particularities and differences.

Concluding remarks and a future research agenda

The broad departure point of this review identifies a range of various impacts of the second-home phenomenon on rural development and several variables affecting the impact, including destination maturity, development phase, second-home user-resident ratio, and spatial distribution, confirming the need for context-sensitive studies. In addition, this review serves as an evidence base for the limited interest by scholars in how second-home development affects local businesses and their innovative capability, encompassing themes like transfer of knowledge and competence, linkages, sources for innovation, diversification and spin-offs and other enablers and barriers for business development. Considering second-home development as a means for fostering prosperous rural development, this limited interest in businesses is a paradox. To address this gap and to enrich and supplement previous studies, future research should integrate business-oriented perspectives and empirics gathered in regions with more advanced economic activities. The municipal level emerges as a central node within the sphere of rural development, having a multifaceted role in balancing beneficial outcomes and mitigating adverse impacts. The findings related to this multifaceted role represent an identified gap warranting further elaboration. Furthermore, aligned with the concept of infusing tourism, this framework advocates for a shift from unilateral studies focused, for instance, solely on the impacts of second homes. In this context, it encourages an exploration of second homes not just as an isolated phenomenon but as integral components of broader rural change processes, presenting an interesting avenue for future research.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Inger Beate Nylund, Senior Academic Librarian at The Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, for her valuable help in constructing the search string. The author also wants to thank Professor Kjell Overvåg and Professor Trond Nilsen, both at The Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, who supervised this PhD research and provided critical insights into the research and writing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adamiak, C., Pitkänen, K., & Lehtonen, O. (2017). Seasonal residence and counterurbanization: the role of second homes in population redistribution in Finland. GeoJournal, 82(5), 1035–1050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-016-9727-x

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Arnesen, T., & Teigen, H. (2019). Fritidsboliger som vekstimpuls i fjellområdet [Second homes as an exogenous development impulse in mountain areas] (Skriftserien [Report no.] 21-2019). Høgskolen i Lillehammer [Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences]. https://www.ostforsk.no/publikasjoner/fritidsboliger-som-vekstimpuls-i-fjellomradet/.

- Arnesen, T., Teigen, H., & Bern, A. (2022). Fritidsboligene i fjellene – Oppspill til kommunal hyttepolitikk for Lillehammer-regionen [Second homes in mountain areas - Possible issues and themes to be adressed in developing a policy at the municipal level] (Skriftserien [Report no.] 17-2012). Høgskolen i Lillehammer [Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences]. https://www.ostforsk.no/publikasjoner/fritidsboligene-i-fjellene-oppspill-til-kommunal-hyttepolitikk-for-lillehammer-regionen/.

- Back, A. (2020). Temporary resident evil? Managing diverse impacts of second-home tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(11), 1328–1342. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1622656

- Back, A. (2021). Endemic and Diverse: Planning Perspectives on Second-home Tourism's Heterogeneous Impact on Swedish Housing Markets. Housing, theory, and society, 39(3), 317–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2021.1944906

- Back, A., & Marjavaara, R. (2017). Mapping an invisible population: the uneven geography of second-home tourism. Tourism geographies, 19(4), 595–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1331260

- Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A., & Maskell, P. (2004). Clusters and knowledge: local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Progress in Human Geography, 28(1), 31–56. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132504ph469oa

- Borge, L.-E., Ellingsen, W., Hjelseth, A., Leikvoll, G. K., Løyland, K., & Nyhus, O. H. (2015). Inntekter og utgifter i hyttekommuner [Second homes - Incomes and expences at the municipal level] (Report no. 349). Telemarksforskning [Telemark Research Institute].

- Carson, D. A., Cleary, J., De la Barre, S., Eimermann, M., & Marjavaara, R. (2016). New mobilities – new economies? Temporary populations and local innovation capacity in sparsely populated areas. In A. J. Taylor, D. B. Carson, P. C. Ensign, & A. Taylor (Eds.), Settlements at the Edge: Remote human settlements in developed nations (pp. 178–206). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784711962.00016

- Coppock, J. T.1977). Second homes: curse or blessing? Pergamon Press.

- Czarnecki, A. (2018). Uncertain Benefits: How second home tourism impacts community economy. In C. M. Hall & D. K. Müller (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Second Home Tourism and Mobilities (pp. 122–133). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315559056-11

- D'Emery, R., Pinto, H., & Almeida, C. R. (2018). Governance networks and second home tourism: Insights from a sun and sea destination. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, 6(4), 375–391. https://www.jsod-cieo.net/journal/index.php/jsod/article/view/158.

- de Oliveira, J. A., Roca, M. N. O., & Roca, Z. (2015). Economic Effects Of Second Homes: A case study in Portugal. Economics and Sociology, 8(3), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2015/8-3/14

- Eder, J. (2019). Innovation in the Periphery: A Critical Survey and Research Agenda. International Regional Science Review, 42(2), 119–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160017618764279

- Ellingsen, W. (2017). Rural Second Homes: A Narrative of De-Centralisation. Sociologia Ruralis, 57(2), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12130

- Ellingsen, W., & Nilsen, B. T. (2021). Emerging geographies in Norwegian mountain areas - Densification, place-making and centrality. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift-Norwegian Journal of Geography, 75(2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2021.1887347

- Emery, M., & Flora, C. B. (2006). Spiraling-up: Mapping Community Transformation with Community Capitals Framework. Community development (Columbus, Ohio), 37(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330609490152

- Ericsson, B., Øian, H., Selvaag, S. K., Lerfald, M., & Breiby, M. A. (2022). Planning of second-home tourism and sustainability in various locations: Same but different? Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography, 76(4), 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2022.2092904

- Farstad, M., & Rye, J. F. (2013). Second home owners, locals and their perspectives on rural development. Journal of rural studies, 30, 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.11.007

- Fialová, D., & Vágner, J. (2014). The owners of second homes as users of rural space in Czechia. Acta Universitatis Carolinae, Geographica, 49(2), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.14712/23361980.2014.11

- Fialová, D., Vágner, J., & Kůsová, T. (2018). Second homes, their users and relations to the rural space and the resident communities in Czechia. In C. M. Hall & D. K. Müller (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Second Home Tourism and Mobilities (pp. 222-232). Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315559056

- Flora, C. B. (2004). Community Dynamics and Social Capital. In D. Rickerl & C. Francis (Eds.), Agroecosystems Analysis (pp. 93-107). American Society of Agronomy, . https://doi.org/10.2134/agronmonogr43

- Flora, C. B., Flora, J. L., & Fey, S. (2004). Rural Communities: Legacy and Change (2 ed.). Westview Press.

- García-Andreu, H., Ortiz, G., & Aledo, A. (2015). Causal Maps and Indirect Influences Analysis in the Diagnosis of Second-Home Tourism Impacts. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(5), 501–510. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2017

- Gill, A. (2000). From growth machine to growth management: The dynamics of resort development in Whistler, British Columbia. Environment and planning, 32(6), 1083–1103. https://doi.org/10.1068/a32160

- Glückler, J., Shearmur, R., & Martinus, K. (2022). Liability or opportunity? Reconceptualizing the periphery and its role in innovation. Journal of Economic Geography, 23(1), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbac028

- Grillitsch, M., & Nilsson, M. (2015). Innovation in peripheral regions: Do collaborations compensate for a lack of local knowledge spillovers? The Annals of Regional Science, 54(1), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-014-0655-8

- Guisan, M.-C., & Aguayo, E. (2010). Second homes in the Spanish regions: Evolution in 2001-2007 and impact on tourism, GDP and employment. Regional and sectoral economic studies, 10(2), 83–104. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-79951701782&partnerID=40&md5=cd0e39960b1d66fa3e3af1ef327920bb.

- Hajimirrahimi, S. D., Esfahani, E., Van Acker, V., & Witlox, F. (2017). Rural Second Homes and Their Impacts on Rural Development: A Case Study in East Iran. Sustainability, 9(4), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040531

- Hall, C. M. (2014). Second Home Tourism. An International Review [Article]. Tourism Review International, 18(3), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427214X14101901317039

- Heleniak, T., & Sánchez Gassen, N. (2020). The demise of the rural Nordic region? Analysis of regional population trends in the Nordic countries, 1990 to 2040. Nordisk välfärdsforskning [Nordic Welfare Research], 5(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2464-4161-2020-01-05

- Hiltunen, M. J. (2007). Environmental impacts of rural second home tourism - Case lake district in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(3), 243–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701312335

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2010a). The Economic Impact of Second Home Development in Small-Town South Africa. Tourism Recreation Research, 35(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2010.11081619

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2010b). The role of second homes in local economic development in five small South African towns. Development Southern Africa, 27(4), 547–562. Article Pii 926478144. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835x.2010.508585

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2011). Economic development through second home development: Evidence from South Africa. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 102(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2011.00663.x

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2015). Focusing on the ‘blessing’ and not the ‘curse’ of second homes: notes from South Africa. Area, 47(2), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12156

- Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2016). Path Development in Different Regional Innovation Systems A Conceptual Analysis. In M. D. Parrilli, R. Dahl Fitjar, & A. Rodriguez-Pose (Eds.), Innovation Drivers and Regional Innovation Strategies. Taylor & Francis Group. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/hilhmr-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4391713

- Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2017). Exogenously Led and Policy-Supported New Path Development in Peripheral Regions: Analytical and Synthetic Routes. Economic geography, 93(5), 436–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2016.1154443

- Kauppila, P. (2009). Resorts’ second home tourism and regional development: A viewpoint of a Northern periphery. Nordia geographical publications, 38(5), 3–12. https://nordia.journal.fi/article/view/75969.

- Kauppila, P., Saarinen, J., & Leinonen, R. (2009). Sustainable Tourism Planning and Regional Development in Peripheries: A Nordic View. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(4), 424–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903175274

- Kietäväinen, A., Rinne, J., Paloniemi, R., & Tuulentie, S. (2016). Participation of second home owners and permanent residents in local decision making: the case of a rural village in Finland. Fennia, 194(2), 152–167. https://doi.org/10.11143/55485

- Kindel, G., & Raagmaa, G. (2015). Recreational home owners in the leadership and governance of peripheral recreational communities. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin, 64(3), 233–245. https://doi.org/10.15201/hungeobull.64.3.6

- Koster, R. L. (2019). Why Differentiate Rural Tourism Geographies? In R. L. Koster & D. A. Carson (Eds.), Perspectives on Rural Tourism Geographies: Case Studies from Developed Nations on the Exotic, the Fringe and the Boring Bits in Between (pp. 1-13). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11950-8

- Kunnskapsstatus fritidsboliger i Innlandet [Second Homes - State of the field]. (2021). Østlandsforskning [Eastern Norway Research Institue].

- Long, P., & Lane, B. (2000). Rural tourism development. In W. C. Gartner & D. W. Lime (Eds.), Trends in outdoor recreation, leisure and tourism (pp. 299-308). Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851994031.0000

- Marcouiller, D. W., Green, G. P., Deller, S. C., & Sumathi, N. R. (1996). Recreational Homes and Regional Development: A Case Study from the Upper Great Lakes States In Cooperative Extension Publications. University of Wisconsin.

- Marjavaara, R., & Lundholm, E. (2016). Does Second-Home Ownership Trigger Migration in Later Life? Population, Space and Place, 22(3), 228–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1880

- Miletić, G.-M., Žmuk, B., & Mišetić, R. (2018). Second homes and local socio-economic development: the case of Croatia. Journal of housing and the built environment, 33(2), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-017-9562-5

- Moscardo, G., Konovalov, E., Murphy, L., & McGehee, N. (2013). Mobilities, community well-being and sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(4), 532–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.785556

- Mottiar, Z. (2006). Holiday Home Owners, a Route to Sustainable Tourism Development? An Economic Analysis of Tourist Expenditure Data. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 14(6), 582–599. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost585.0

- Mottiar, Z., & Quinn, B. (2003). Shaping leisure/tourism places - The role of holiday home owners: A case study of Courtown, Co. Wexford, Ireland. Leisure Studies, 22(2), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/0261436032000061169

- Mowl, G., Barke, M., & King, H. (2020). Exploring the heterogeneity of second homes and the ‘residual’ category. Journal of rural studies, 79, 74–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.08.016

- Müller, D. K. (2004). Second Homes in Sweeden: Patterns and Issues. In C. M. Hall, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Tourism, Mobility and Second Homes: Between Elite Landscape and Common Ground (pp. 244–260). Channel View Publications Limited. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84949210745&partnerID=40&md5=7e179a2b5d0935073489839530fad5db.

- Müller, D. K. (2019). Infusing tourism geographies. In D. K. Müller (Ed.), A Research Agenda for Tourism Geographies (pp. 60–70). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/hilhmr-ebooks/detail.action?docID=5741327.

- Müller, D. K., & Hall, C. M. (2018). Second home tourism An introduction. In C. M. Hall, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second home tourism and mobilities ((1 ed, pp. 3–14). Routledge.

- Müller, D. K., Hall, C. M., & Keen, D. (2004). Second Home Tourism Impact, Planning and Management. In C. M. Hall, & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Tourism, Mobility and Second Homes: Between Elite Landscape and Common Ground ((1 ed, pp. 15–31). Channel View Publications Limited. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/hilhmr-ebooks/detail.action?docID=214065.

- Müller, D. K., & Hoogendoorn, G. (2013). Second Homes: Curse or Blessing? A Review 36 Years Later. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 13(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2013.860306

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143–143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Nordbø, I. (2014). Beyond the Transfer of Capital? Second-Home Owners as Competence Brokers for Rural Entrepreneurship and Innovation. European planning studies, 22(8), 1641–1658. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.784608

- Nordin, U., & Marjavaara, R. (2012). The local non-locals: Second home owners associational engagement in Sweden. Tourism, 60(3), 293–305. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84870004919&partnerID=40&md5=dfc78b3d3d227841478d9cca600105f3.

- Norris, M., & Winston, N. (2009). Rising Second Home Numbers in Rural Ireland: Distribution, Drivers and Implications. European planning studies, 17(9), 1303–1322. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310903053448

- Overvåg, K. (2010). Second homes and maximum yield in marginal land: The re-resourcing of rural land in Norway. European Urban & Regional Studies, 17(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776409350690

- Overvåg, K., & Berg, N. G. (2011). Second Homes, Rurality and Contested Space in Eastern Norway. Tourism geographies, 13(3), 417–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.570778

- Palmer, A., & Mathel, V. (2010). Causes and consequences of underutilised capacity in a tourist resort development. Tourism Management, 31(6), 925–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.12.001

- Paré, G., Tate, M., Johnstone, D., & Kitsiou, S. (2016). Contextualizing the twin concepts of systematicity and transparency in information systems literature reviews. European journal of information systems, 25(6), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41303-016-0020-3

- Paré, G., Trudel, M.-C., Jaana, M., & Kitsiou, S. (2015). Synthesizing information systems knowledge: A typology of literature reviews. Information & management, 52(2), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.08.008

- Paré, G., Wagner, G., & Prester, J. (2023). How to develop and frame impactful review articles: key recommendations. Journal of decision systems, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2023.2197701

- Park, M., Derrien, M., Geczi, E., & Stokowski, P. A. (2019). Grappling with Growth: Perceptions of Development and Preservation in Faster- and Slower-Growing Amenity Communities. Society and Natural Resources, 32(1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2018.1501527

- Perles-Ribes, J. F., Ramon-Rodriguez, A. B., Sevilla-Jimenez, M., & Moreno-Izquierdo, L. (2018). Differences in the economic performance of hotel-based and residential tourist destinations measured by their retail activity. Evidence from Spain. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(18), 2084–2115. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1240155

- Pike, A., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2017). Local and regional development. Routledge.

- Pitkänen, K., Sireni, M., Rannikko, P., Tuulentie, S., & Hiltunen, M. J. (2017). Temporary Mobilities Regenerating Rural Places. Case Studies from Northern and Eastern Finland. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 12(2/3), 93–113. https://login.ezproxy.inn.no/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=127839457&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- Rantanen, M., & Czarnecki, A. (2023). Second-home owners as local developers: Roles and influencing factors. Journal of rural studies, 97, 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2023.01.002

- Robertsson, L., & Marjavaara, R. (2015). The Seasonal Buzz: Knowledge Transfer in a Temporary Setting. Tourism Planning and Development, 12(3), 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2014.947437

- Rumrill, P. D., Fitzgerald, S. M., & Merchant, W. R. (2010). Using scoping literature reviews as a means of understanding and interpreting existing literature. Work-a Journal of Prevention Assessment & Rehabilitation, 35(3), 399–404. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2010-0998

- Rye, J. F. (2011). Conflicts and contestations. Rural populations’ perspectives on the second homes phenomenon. Journal of rural studies, 27(3), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.03.005

- Schmallegger, D., Harwood, S., Cerveny, L., & Müller, D. K. (2011). Tourist Populations and Local Capital. In R. O. Rasmussen, P. Ensign, & L. Huskey (Eds.), Demography at the Edge: Remote Human Populations in Developed Nations (1 ed., pp. 271-288). Florence: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315576480

- Sheard, N. (2019). Vacation homes and regional economic development. Regional Studies, 53(12), 1696–1709. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1605440

- Sievänen, T., Neuvonen, M., & Pouta, E. (2007). Recreational Home Users – Potential Clients for Countryside Tourism? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(3), 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701300207

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of business research, 104, 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

- Soszyński, D., Sowińska-Świerkosz, B., Stokowski, P. A., & Tucki, A. (2018). Spatial arrangements of tourist villages: implications for the integration of residents and tourists. Tourism geographies, 20(5), 770–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1387808

- Sutton, A., Clowes, M., Preston, L., & Booth, A. (2019). Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 36(3), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12276

- Syssner, J. (2020). Pathways to Demographic Adaptation: Perspectives on Policy and Planning in Depopulating Areas in Northern Europe. Springer International Publishing AG. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/hilhmr-ebooks/detail.action?pq-origsite=primo&docID=6012277#.

- Tangeland, T., Vennesland, B., & Nybakk, E. (2013). Second-home owners’ intention to purchase nature-based tourism activity products - A Norwegian case study. Tourism Management, 36, 364–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.10.006

- Terzić, A., Drobnjaković, M., & Petrevska, B. (2020). Traditional Serbian Countryside and Second-Home Tourism Perspectives. European Countryside, 12(3), 312–332. https://doi.org/10.2478/euco-2020-0018

- Tomaney, J. (2017). Region and place III: Well-being. Progress in Human Geography, 41(1), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515601775

- Van Auken, P. M. (2010). Seeing, not Participating: Viewscape Fetishism in American and Norwegian Rural Amenity Areas. Human Ecology, 38(4), 521–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-010-9323-5

- Velvin, J., Kvikstad, T. M., Drag, E., & Krogh, E. (2013). The impact of second home tourism on local economic development in rural areas in Norway. Tourism Economics, 19(3), 689–705. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2013.0216

- Visser, G. (2004). Second homes and local development: Issues arising from Cape Town's De Waterkant. GeoJournal, 60(3), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:GEJO.0000034733.80648.88

- Winkler, R., Deller, S., & Marcouiller, D. (2015). Recreational Housing and Community Development: A Triple Bottom Line Approach. Growth and change, 46(3), 481–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12100

- Wu, M., & Gallent, N. (2021). Second homes, amenity-led change and consumption-driven rural restructuring: The case of Xingfu village, China. Journal of rural studies, 82, 391–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.01.036