?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper examines the validity of the export-led growth (ELG) hypothesis in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) over the period 1975–2012, using a neoclassical production function augmented with merchandise exports and imports of goods and services. The study applies the Johansen cointegration technique and dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) regression to confirm the existence of a long-run relationship between exports and economic growth, while the multivariate Granger causality test is applied to examine the direction of the short-run causality. In addition, the existence of long-run causality is investigated by applying a modified version of the Wald test in an augmented vector autoregressive model. The Johansen test and DOLS results confirm the existence of a long-run relationship between exports and economic growth. In addition, the study provides evidence to support the validity of the ELG hypothesis in the short-run, while no long-run causality is found to exist.

1. Introduction

The relationship between exports and economic growth is a central theme in the discourse among economists trying to explain differences in the rate of economic growth between countries. The growth of exports increases technological innovation, responds to foreign demand and, also, increases the inflows of foreign exchange, which leads to greater capacity utilization and economic growth. Export-led growth is a strategy favoured by governments to enhance economic growth, but is the export-led growth (ELG) hypothesis valid in the case of the United Arab Emirates (UAE)?

The UAE has achieved strong economic growth and significant export expansion over the last three decades. By 2012, the gross domestic product of the UAE had increased 25 times compared with its 1975 level, an average annual growth rate of 10% (World Development Indicators, World Bank). In the 3 years following the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, the UAE’s GDP increased by 51%, with an average annual growth rate of approximately 15%, when the global average annual GDP growth rate was estimated at about 3% (World Development Indicators, World Bank).

In 2012 the UAE was ranked seventeenth among the leading exporters in world merchandise trade (International Trade Statistics, WTO, Citation2013). The value of UAE merchandise exports in 2012 was US$300 billion, with an average annual growth rate of 12.6% for the period 1975–2012. During the period 1975–2001, the growth of merchandise exports averaged 5.7%, while the average annual growth rate from 2002 to 2012 was about 19%. Whether merchandise exports cause economic growth in the short-run and in the long-run in the UAE is the subject of this paper.

Evidence to date on the causal relationship between exports and economic growth in the UAE has been limited and contradictory. Only two studies, Al-Yousif (Citation1997) and El-Sakka and Al-Mutairi (Citation2000) have investigated the relationship between aggregate exports and economic growth in the UAE. Al-Yousif (Citation1997) provides evidence on the validity of the ELG in the short-run, while El-Sakka and Al-Mutairi (Citation2000) support the GLE (growth-led exports) hypothesis in the short-run. In addition, the methods used in these studies have numerous limitations, which the present study tries to overcome.

This paper attempts to re-examine the validity of the ELG hypothesis, in order to inform the design of future policies for enhancing and sustaining economic growth in the UAE and other small oil-producing countries. This study also addresses several issues that have been overlooked generally in the previous empirical literature. In particular, previous studies have performed unit root tests biased towards the non-rejection of a unit root in the presence of a structural break. Oil-producing economies like that of the UAE are subject to oil price shocks and for this reason, in addition to conventional unit root tests, the Saikkonen and Lutkepohl test with a structural break is applied. Another issue that is overlooked by previous studies is that Johansen’s (Citation1988) cointegration test can be biased towards rejecting the null hypothesis of no cointegration for small samples. To overcome this issue, this study uses the Reinsel-Ahn adjustment for small samples (Reinsel & Ahn, Citation1992). In addition, the dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) procedure is used to confirm the results obtained using the Johansen cointegration test.

Moreover, most empirical studies have used bivariate or trivariate models to test the ELG hypothesis, and this may lead to biased results inasmuch as causality tests are sensitive to omitted variables. To overcome this problem, the present study includes variables omitted previously. In addition, the majority of the more recent studies investigate the existence of long-run causality in an error correction model (ECM) context, but in the case of multivariate ECMs, only the joint causality from the explanatory variables to the dependent variable is indicated. The long-run causal effect of each variable on the dependent variable cannot be identified on its own. Therefore, in a multivariate ECM context, it is not possible to confirm the validity of the ELG hypothesis in the long-run. For this reason, this study uses the Toda Yamamoto modified Granger causality test, which overcomes the limitations of previous studies.

The results of this study provide evidence to support the validity of the ELG hypothesis in the short-run, while indicating that there is no long-run causality between merchandise exports and economic growth in the UAE.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the literature on the relationship between exports and economic growth. Section 3 describes the chosen methodology, data sources and empirical models, while Section 4 reports and interprets the empirical results. Section 5 presents the conclusions and policy implications of this research.

2. Literature review

Numerous studies indicate that exports have a statistically significant positive effect on economic growth, through their impact on economies of scale, the adoption of advanced technologies and a higher level of capacity utilization (Abou-Stait, Citation2005; Al-Yousif, Citation1997; Balassa, Citation1978; Emery, Citation1967; Feder, Citation1982; Lucas, Citation1988; Michaely, Citation1977; Vohra, Citation2001). In particular, export growth increases the inflow of investment into those sectors where the country has a comparative advantage, leading to the adoption of advanced technologies, increased national output and an increased rate of economic growth. Moreover, an increase in exports causes an increase in the inflow of foreign exchange, allowing the expansion of imports of services and capital goods, which are essential to improving productivity and economic growth (Chenery & Strout, Citation1966; Gylfason, Citation1999; McKinnon, Citation1964).

A smaller number of studies report a negative impact of exports on economic growth (Berrill, Citation1960; Kim & Lin, Citation2009; Lee & Huang, Citation2002; Meier, Citation1970; Myrdal, Citation1957). Berrill (Citation1960) indicates that export expansion could be an obstacle to the development of small developing countries, while Myrdal (Citation1957) notes that the commercial exchanges between developed and developing countries could widen the gap between them. In particular, Myrdal (Citation1957) argues that the exports of under-developed countries are mainly primary products, which are subject to excessive price fluctuations and an inelastic demand in the export market. Moreover, the revenues from exports are directed towards increasing primary good production and, in doing so, widen the gap between developed and developing countries. Myint (Citation1954) showed that, historically, export growth had a negative impact on economic growth in Asian and African countries.

A number of studies have analysed the export effect on economic growth, specifically for developing countries, and highlight the differences between developed and less developed countries. These studies conclude that export expansion exerts a positive impact on economic growth for more developed countries and that this can be explained by the fact that less developed countries are not characterized by political and economic stability and do not provide incentives for capital investments (Kavoussi, Citation1984; Kohli & Singh, Citation1989; Levine, Loayza, & Beck, Citation2000; Michaely, Citation1977; Vohra, Citation2001).

In addition, other studies such as those of Tuan and Ng (Citation1998), Abu-Qarn and Abu-Bader (Citation2004), Herzer, Nowak-Lehmann, and Siliverstovs (Citation2006), Siliverstovs and Herzer (2006, Siliverstovs & Herzer, Citation2007), Hosseini and Tang (Citation2014) and Kalaitzi and Cleeve (Citation2017) investigate the impact of export composition on economic growth, concluding that not all exports contribute equally to economic growth. In particular, the effect of manufactured exports on economic growth can be positive and significant, while the expansion of primary exports can have a negligible or negative impact on economic growth. As Herzer et al. (Citation2006) and Kalaitzi and Cleeve (Citation2017) point out, primary exports do not offer knowledge spillovers and other externalities as manufactured exports. In general, as Sachs and Warner (Citation1995) show, a higher share of primary exports is associated with lower economic growth.

Several studies focus on the direction of the causality between exports and economic growth. Most of these studies conclude that causality flows from exports to economic growth and, as such, export-led growth exists (Abou-Stait, Citation2005; Ahmad, Draz, & Yang, Citation2018; Awokuse, Citation2003; Ferreira, Citation2009; Gbaiye et al., Citation2013; Shirazi & Manap, Citation2004; Siliverstovs & Herzer, Citation2006; Yanikkaya, Citation2003). The growth of exports increases technological innovation, responds to domestic and foreign demand, and also, increases the inflow of foreign exchange, which can lead to greater capacity utilization and economic growth.

In contrast, other studies argue that causality runs from growth to exports (GLE) or conclude that there is a bi-directional causal relationship (ELG-GLE) between exports and economic growth (Abu Al-Foul, Citation2004; Awokuse, Citation2007; Dinç & Gökmen, Citation2019; Edwards, Citation1998; Elbeydi, Hamuda, & Gazda, Citation2010; Kalaitzi & Cleeve, Citation2017; Love & Chandra, Citation2005; Mishra, Citation2011; Narayan, Narayan, Prasad, & Prasad, Citation2007; Panas & Vamvoukas, Citation2002; Ray, Citation2011). In the case of growth-led exports, economic growth can cause an increase in exports, by increasing national production and the country’s capacity to import goods and services. In particular, growth creates new needs, which cannot initially be satisfied by local production, increasing the country’s imports, especially for capital equipment, and improving the existing technology (Kindleberger, Citation1962). Finally, several studies indicate no causal link between exports and economic growth (El-Sakka & Al-Mutairi, Citation2000; Jung & Marshall, Citation1985; Kwan & Cotsomitis, Citation1991; Tang, Citation2006).

In the UAE context, two studies, Al-Yousif (Citation1997) and El-Sakka and Al-Mutairi (Citation2000), have investigated the effect of aggregate exports on economic growth, but their results are contradictory. In particular, the study by Al-Yousif (Citation1997) examines the relationship between exports and economic growth in four Gulf countries, namely Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, UAE and Oman, over the period 1973–1993. The study uses an augmented production function with exports, government expenditure and terms of trade, and applies the two-step cointegration technique and regression analysis. The results indicate that there is no long-run relationship between exports and economic growth, while exports positively affect growth in the short-run for all of the countries examined.

Similarly, El-Sakka and Al-Mutairi (Citation2000) investigate the relationship between exports and growth in Arab countries for the period 1972–1996, but their study uses the Johansen cointegration test and bivariate Granger causality tests. The study confirms the results of Al-Yousif (Citation1997) regarding the non-existence of a long-run relationship between exports and economic growth for all countries examined, but indicates that short-run causality runs from growth to exports in the case of the UAE. As for short-run causality between exports and economic growth in the other countries studied, the results are mixed. In particular, a uni-directional causality runs from exports to growth in Iraq, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Syria, while a bi-directional causality exists between exports and growth in Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Mauritania and Oman. However, no causal relationship between exports and growth is found for Kuwait, Libya, Tunisia, Qatar or Sudan. There is thus no agreement on whether aggregate exports cause economic growth in the MENA region.

Al-Yousif (Citation1997) claims that the ELG hypothesis is valid, based on a regression model in which economic growth is the dependent variable and exports is the explanatory variable. The study’s conclusion relies on the statistical significance of the coefficients of the export variables, but this is not an appropriate way to draw conclusions about the causal relationship between exports and economic growth, as regression shows only the impact on economic growth and not the cause. In addition, the estimation of a single equation suffers from a misspecification problem, as the impact does not necessarily run from exports to economic growth. As El-Sakka and Al-Mutairi (Citation2000) note, “if a bi-directional causality between these two variables (exports and economic growth) exists, the estimation and tests used in the impact studies are inconsistent” (p.155).

Moreover, most empirical studies, including the study by El-Sakka and Al-Mutairi (Citation2000), have used bivariate or trivariate models to test the ELG hypothesis, and this may lead to misleading and biased results inasmuch as causality tests are sensitive to omitted variables. To overcome this problem, the present study includes variables omitted in previous studies, such as capital accumulation, population and imports of goods and services. In addition, most recent studies investigate the existence of long-run causality in an error correction model (ECM) context, by testing the significance of the error correction term (Awokuse; Citation2007; Herzer et al.; Citation2006; Hosseini & Tang, Citation2014; Mishra, Citation2011). The problem is that in the case of multivariate ECMs, only the joint causality from the explanatory variables to the dependent variable is indicated. The causal effect of each variable on the dependent variable can only be identified in the short-run. Therefore, in an ECM context, it is not possible to confirm the validity of the ELG hypothesis in the long-run. For this reason, this study uses the Toda Yamamoto Granger causality test, which overcomes the limitations of previous studies.

3. Empirical strategy

The causality between merchandise exports and economic growth is examined using a Cobb–Douglas production function augmented with merchandise exports and imports of goods and services. The study follows Balassa (Citation1978) and Fosu (Citation1990) in incorporating exports into the production function and Riezman, Whiteman, and Summers (Citation1996) in including imports in the model. In particular, imported goods can be considered as inputs for export-oriented production and the omission of this variable could lead to biased results. In the UAE, imports of goods and services are used as inputs for merchandise exports, and for this reason, imports are included in the estimations. Furthermore, imports are considered to be a major channel for technology transfer and knowledge diffusion, which are essential to economic growth (Coe & Helpman, Citation1995; Keller, Citation2000).

The present study assumes that the aggregate production of the economy can be expressed as a function of physical capital, human capital, merchandise exports and imports of goods and services:

where denotes the aggregate production of the UAE economy at time t,

is total factor productivity, while

and

represent physical capital and human capital, respectively. The constants

and

measure the impact of physical capital and human capital on national income. As mentioned above, in order to test the relationship between merchandise exports and economic growth, it is assumed that total factor productivity can be expressed as a function of merchandise exports,

, imports of goods and services,

, and other exogenous factors

:

Combining Equationequations (1)(1)

(1) and (Equation2

(2)

(2) ), the following is obtained:

where ,

,

and

represent the elasticities of production with respect to the inputs of production:

,

,

, and

. Taking the natural logs of both sides of Equationequation (3)

(3)

(3) yields the following:

where c is the intercept, the coefficients ,

,

and

are constant elasticities, while

is the error term, which reflects the influence of factors not included in the model.

This study uses annual time series for the UAE over the period 1975–2012, obtained from the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization and the UAE National Bureau of Statistics. Specifically, the gross domestic product () and merchandise exports (

) are from the World Development Indicators-World Bank, while the population (

) is from the UAE National Bureau of Statistics. Imports of goods and services (

) and gross fixed capital formation (

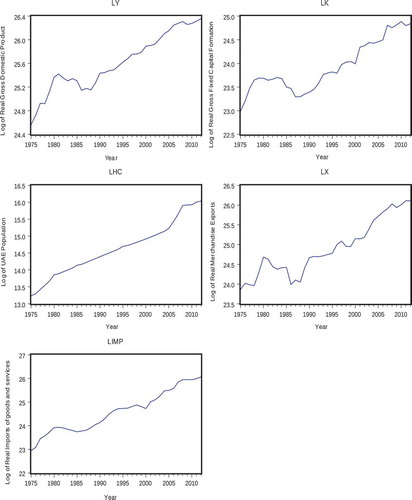

) are taken from the IMF International Financial Statistics, UAE National Bureau of Statistics and World Bank. The macroeconomic variables are expressed in real terms, using the GDP deflator taken from the World Development Indicators database. In addition, the variables are expressed in logarithmic form. The descriptive statistics and plots of the log-transformed data are shown in and respectively.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the series for the period 1975–2012

Figure 1. Patterns of the logarithms of the series over the period 1975–2012

Before investigating the existence of a causal relationship between exports and economic growth, it is important to ensure that the variables presented above are stationary. To do this, the augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test, the Phillips-Perron (PP) test and the Saikkonen and Lutkepohl (SL) test with a structural break are applied.Footnote1 If the variables are found to be non-stationary, which is the most common case for economic variables, the first differences will be used.

Once the stationarity of the data series has been assessed, the existence of a long-run relationship is examined by performing the Johansen cointegration test (Johansen, Citation1988).Footnote2 In addition, the DOLS method developed by Saikkonen (Citation1991) is used to confirm the robustness of the Johansen estimates.

Johansen’s methodology estimates the cointegrating vectors using a maximum likelihood procedure, taking as its starting point the vector autoregression (VAR) of order p (Hjalmarsson and Österholm, Citation2007, p. 4) given by:

is an (

) vector of variables which is

;

is a (

) vector of constants; while

is an (

) vector of random errors. Subtracting Xt −1 from each side of Equationequation (5)

(5)

(5) and letting I be an (

) identity matrix, this VAR can be re-written as:

where and

is the difference operator,

is an (

) column vector of variables,

is an (

) vector of constants, while

and

are the coefficient matrices. The rank of matrix

provides information about the long-run relationships among the variables. In the case where the coefficient matrix

has rank r < n, but is not equal to zero, the variables are cointegrated and r is the number of cointegrating vectors. The number of cointegrating vectors can be determined by using the likelihood ratio (LR) trace test statistic suggested by Johansen (Citation1988). The LR trace statistic used here is adjusted for small sample size,Footnote3 and is as follows:

where T is the sample size and λ is the eigenvalue. The trace test is a test of the null hypothesis of at most r cointegrating vectors against the alternative hypothesis of n cointegrating vectors.

The DOLS models for economic growth and merchandise exports used to confirm the Johansen estimates are as follows:Footnote4

where ,

,

and

represent the long-run elasticities, while

,

,

and

are the coefficients of the lead and lag differences. The number of leads and lags in each equation is determined by minimizing the Schwarz information criterion (SIC), while Hendry’s general-to-specific modelling approach is used to determine the final models.

In order to investigate whether exports cause economic growth, we use the VAR model developed by Sims (Citation1980), in which the optimal lag length of each variable is selected based on the SIC. Providing the variables are found to be cointegrated, the causality will be tested by estimating the following restricted VAR model (VECM: vector error correction model):

represents the variable of economic growth, while

,

,

and

represent the independent variables of Equationequation (4)

(4)

(4) .

is the difference operator,

,

,

,

,

,

and

are the regression coefficients and

is the error correction term derived from the cointegration equation. In the above VECMFootnote5 framework,

and

are influenced by both short-term difference lagged variables and long-term error correction terms (

).

The parameter constancy of the estimated ECMs is assessed by applying the cumulative sum of recursive residuals (CUSUM) and the CUSUM of squares (CUSUMQ) tests proposed by Brown, Durbin, and Evans (Citation1975). In particular, the CUSUM test detects systematic changes, while the CUSUMQ test provides useful information when the departure from constancy of the parameters is haphazard. In particular, the CUSUM test is based on the statistic:

s is the standard deviation of the recursive residuals (), defined as:

The numerator is the forecast error,

is the estimated coefficient vector up to period

and

is the row vector of observations on the regressors in period t.

denotes the (

) × k matrix of the regressors from period 1 to period

.

If the b vector changes, will tend to diverge from the zero mean value line; if the b vector remains constant,

. The test shows parameter instability if the CUSUM statistic lies outside the area between the two 5% significance lines, the distance between which increases with t.

The CUSUMQ test uses the squared recursive residuals, , and is based on the plot of the statistic:

where . The expected value of

, under the null hypothesis of the

constancy is

, which goes from zero at

to unity at

. In this test the

are plotted together with the 5% significance lines. Movements outside the 5% significance lines indicate instability in the equation during the examined period.

After estimating the VECM model and investigating the constancy of the model parameters, we conduct the Granger causality (Granger, Citation1969, Citation1988) using the chi-square statistic. The short-run causality from exports to economic growth is examined by testing the null hypothesis “exports do not Granger cause economic growth” () against the alternative hypothesis “exports Granger cause economic growth” (

). To investigate the causality from economic growth to exports, the null hypothesis “economic growth does not Granger cause exports” (

) is tested against the alternative hypothesis “economic growth Granger causes exports” (

).

It should be noted that in the case of multivariate ECMs, the causal effect of each variable on the dependent variable cannot be identified. In Equationequations (10)(10)

(10) and (Equation13

(13)

(13) ), negative and significant

or

indicate only a joint long-run causality running from the explanatory variables to either growth or exports. Therefore, in a multivariate ECM context, it is not possible to confirm the validity of the ELG or the GLE hypothesis in the long-run. For this reason, this paper applies the modified version of the Granger causality test (MWALD) proposed by Toda and Yamamoto (Citation1995). In the present study, the test utilizes the following model:

p is the optimal lag length, selected by minimizing the value of the SIC, while dmax is the maximum order of integration of the variables in the model. The selected lag length (p) is augmented by the maximum order of integration (dmax), and the chi-square test is applied to the first p VAR coefficients.

4. Empirical results

and present the results of the ADF, PP and SL tests for the logarithmic levels and first differences of the time series. The results of the ADF and PP test at the log level indicate that the null hypothesis of non-stationarity cannot be rejected for LY, LK, LHC, LX and LIMP at any conventional significance level. In contrast, after taking the first difference of LY, LK, LX and LIMP, the null hypothesis for unit root can be rejected at the 1% level of significance, while the first-differenced series of LHC is found to be stationary at the 5% significance level. Similarly, the SL test results indicate that, when a structural break is considered,Footnote6 the series are stationary at first difference at the 1% significance level.

Table 2. ADF, PP and SL test results at logarithmic level

Table 3. ADF, PP and SL test results at first difference

Since all variables are I(1), the Johansen cointegration test is conducted. The adjusted trace statistics indicate that the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected at the 5% significance level and, thus, there is a single cointegration vector.Footnote7 The results are reported in .

Table 4. Johansen’s cointegration test results

The DOLS results in and confirm the existence of a long-run relationshipFootnote8 between exports and economic growth in both equations over the period 1975–2012.Footnote9

Table 5. DOLS estimation results (EquationEquation 8)(8)

(8)

Table 6. DOLS estimation results (EquationEquation 9)(9)

(9)

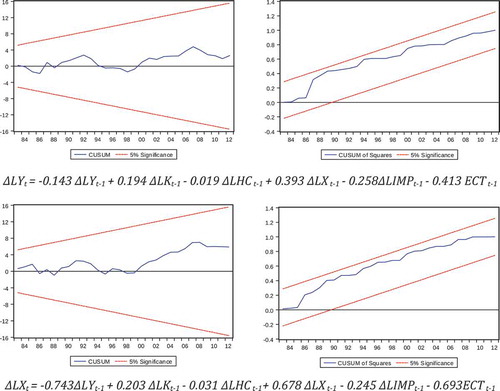

Since the variables are integrated of order one and cointegrated, a VECM is specified. The aim of this study is to find the direction of the causality between exports and economic growth and therefore, emphasis is placed on the estimated error correction models for and ΔLXt. The absolute t-statistics are reported in the parentheses:

The error correction terms are negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, providing evidence that the long-run relationship runs jointly from the explanatory variables to the dependent variable. Therefore, both the DOLS and VECM provide evidence of a long-run relationship between exports and economic growth, confirming the Johansen cointegration results.

The short-run Granger causality results are reported in . They show that the null hypothesis of non-causality from exports to economic growth is rejected at 1% level, indicating that the ELG hypothesis is valid in the short-run. In addition, physical capital and imports Granger cause economic growth in the short-run at 10%. In contrast, the null hypothesis of non-causality from economic growth to exports cannot be rejected at any conventional significance level, indicating that the GLE hypothesis is not valid in the short-run. The results also indicate that the null hypothesis of joint non-causality from ΔLKt-1, ΔLHCt-1, ΔLXt-1 and ΔLIMPt-1 to economic growth is rejected at the 1% level.

Table 7. Short-run Granger causality test

The above results may be partly due to the role of increased exports in fostering technological innovation through increased investment and improved productivity (Balassa, Citation1978; Ramos, Citation2001). Second, productivity will be enhanced by the expansion of capital good imports as a result of the impact of export growth on foreign exchange earnings (Edwards, Citation1998; Yanikkaya, Citation2003). Third, imports provide essential materials for increasing the domestic production of manufactured goods (Chenery & Strout, Citation1966; Gylfason, Citation1999).

Since the goal of this paper is to find the direction of the causality between exports and economic growth, emphasis is placed on the structural stability of the parameters of the estimated ECMs for ΔLYt and ΔLXt. As for the constancy of the parameters in Equationequations (10)(10)

(10) and (Equation13

(13)

(13) ), the estimated CUSUM statistics are plotted in together with the 5% critical lines of parameter stability. There is no movement outside the 5% critical lines of parameter stability; that is, the models for economic growth and exports are stable even during periods of oil price volatility.

Figure 2. Plots of CUSUM and CUSUMQ for the estimated ECMs for economic growth and merchandise exports

With regard to long-run causality, the Toda and Yamamoto test results,Footnote10 presented in , show that the null hypothesis that LXt does not Granger cause LYt cannot be rejected at 5%. In addition, there is no evidence to support the converse, as the null hypothesis of non-causality from LYt to LXt cannot be rejected at any conventional significance level. Therefore, the Toda-Yamamoto procedure does not provide evidence in support of either the ELG or GLE hypothesis in the long-run.

Table 8. Causality based on the Toda-Yamamoto procedure

The lack of a long-run causality between exports and growth may arise because aggregate measures mask the different causal effects on economic growth of the various components of exports. In addition, oil exports may offset the impact of other categories of merchandise exports inasmuch as the former face inelastic demand, may be subject to excessive price fluctuations and do not offer knowledge spillovers (Herzer et al., Citation2006; Kalaitzi & Cleeve, Citation2017; Myrdal, Citation1957). These findings have prompted studies of the impact of specific export categories on economic growth. Tuan and Ng (Citation1998), Herzer et al. (Citation2006) and Kalaitzi and Cleeve (Citation2017), among others, find that not all exports affect economic growth equally.

Our analysis also finds that the null hypothesis that does not cause

in the long run is rejected at the 5% level. In addition, the null hypothesis of the joint non-causality from

,

,

and

to economic growth is rejected at the 1% significance level, while the null hypothesis of the joint non-causality from

,

,

and

to exports is rejected at 5%. These results are consistent with equations (22) and (Equation23

(22)

(22) ), and show that long-run causality runs jointly from all the variables in the model to economic growth and to exports.

5. Conclusion

The present study provides evidence on the relationship between merchandise exports and economic growth for the United Arab Emirates over the period 1975–2012. The cointegration results confirm the existence of long-run relationships among the variables under consideration. The short-run Granger causality results support the existence of causality from merchandise exports to economic growth, indicating that the ELG hypothesis is valid in the short-run. This finding is consistent with those reported for other nations (Abou-Stait, Citation2005; Awokuse, Citation2003; Ferreira, Citation2009; Gbaiye et al., Citation2013; Shirazi & Manap, Citation2004; Siliverstovs & Herzer, Citation2006; Yanikkaya, Citation2003). As for the UAE, the results are consistent with those of Al-Yousif (Citation1997), but contrast with those reported by El-Sakka and Al-Mutairi (Citation2000). Specifically, Al-Yousif (Citation1997) finds that exports have a positive short-run impact on economic growth, while El-Sakka and Al-Mutairi (Citation2000) supports the growth-led exports hypothesis. Differences in results may be affected by the period examined, the choice of variables, the lag length selection and the econometric methods used in the estimation.

As far as long-run causality is concerned, the study’s results do not provide evidence in support of either the ELG or the GLE hypothesis for the UAE. This is consistent with Al-Yousif (Citation1999) and Tang (Citation2006), who found no long-run causality between exports and economic growth for Malaysia and China, respectively. Likewise, the evidence in support of the ELG hypothesis for the UAE only applies in the short-run.

The absence of a long-run causal relationship between exports and economic growth is likely due to the UAE’s continued reliance on oil, in spite of efforts to diversify its economy over the past three decades. UAE merchandise exports consist largely of oil and oil-related goods, production of which does not offer significant knowledge spillovers to the rest of the economy. This suggests that policy makers in the UAE cannot rely on merchandise exports as the primary engine of growth as they plot the nation’s future. The UAE has to adopt a balanced approach to developing its economy, by focusing not only on exports that facilitate short-run economic growth but also on investing in physical and human capital and promoting productivity-enhancing imports. In particular, targeting new export sectors with investments in new technology and imports of the necessary capital goods will move the economy away from its reliance on oil. A challenge for researchers and policy makers alike is to identify those export categories that, for the UAE, are most likely to foster future economic growth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Athanasia S. Kalaitzi

Dr. Athanasia S. Kalaitzi is Visiting Fellow at the Middle East Centre, London School of Economic and Political Science, UK. She also serves as a Quantitative Skills Tutor at Queen Mary University of London, UK. Her research and consultancy work is focused on economic modelling, econometric analysis, trade diversification, energy reform and economic performance in the GCC region.

Trevor W. Chamberlain

Dr. Trevor W. Chamberlain is Professor and Chair of Finance and Business Economics at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada. Dr. Chamberlain received his PhD from the University of Toronto in 1985 and has been a member of the faculty at McMaster for the past thirty-five years. In recent years he has been investigating problems in economics and finance in the GCC region.

Notes

1 The SL test is applied, as the ADF and PP test statistics are biased toward the non-rejection of a unit root in the presence of a structural break.

2 As Gonzalo (Citation1994) notes, Johansen’s cointegration test satisfies the three elements of a cointegration system, “first the existence of unit roots, second the multivariate aspect, and third the dynamics. Not taking these elements into account may create problems in estimation” (p.223).

3 Trace statistics are adjusted by using the correction factor proposed by Reinsel and Ahn (Citation1992), where T is the sample size, and n and p are the number of variables and the optimal lag length, respectively.

4 The DOLS method provides unbiased and asymptotically efficient estimates of long-run relationships, even in the presence of potential endogeneity (Stock & Watson, Citation1993).

5 Diagnostic tests are conducted in order to determine whether the VECM is well specified and stable. In particular, these tests include the Jarque–Bera normality test (Jarque & Bera, Citation1980, Citation1987), the Portmanteau (Lütkepohl, Citation1991) and Breusch–Godfrey LM tests (Johansen, Citation1995) for the existence of autocorrelation, the White heteroskedasticity test (White, Citation1980), the multivariate ARCH test (Engle, Citation1982) and the AR roots stability test (Lütkepohl, 1991).

6 In particular, in 1986, GDP growth rate plunged to −16%, due to a collapse in oil prices of over 50%. In the second half of 2000, due to the production cuts by OPEC countries, the oil price increased by approximately 200%, reaching over US $30 per barrel.

7 Johansen cointegration tests with one structural break and two structural breaks are estimated, and the results reported in the Appendix ( and ). The model is estimated with the inclusion of an impulse dummy variable for the year 1986 and for the years 1986 and 2001, based on the structural breaks identified by the SL unit root test. The results of the Johansen cointegration tests with structural breaks confirm the existence of a long-run relationship among the variables considered.

8 In addition, the existence of cointegration among the variables is examined by conducting a chi-square test and the null hypothesis no cointegration is tested against the alternative hypothesis of cointegration

. The results show that a long-run relationship exists among the variables in both DOLS models.

9 The diagnostic tests suggest that the models are well specified and presented below and . In addition, the model parameters’ stability is confirmed based on CUSUM estimations; the models are stable even during the oil crises of 1986 and 2001. The DOLS models are also estimated with two impulse dummy variables for the years 1986 and 2001, without altering the results to any significant degree. The results are available upon request.

10 In our data, the maximum order of integration is dmax = 1, while the optimal lag length, based on the Schwarz information criterion, is one. Therefore, the selected lag length (p = 1) is augmented by the maximum order of integration (dmax = 1), and the Wald test is applied to the first p VAR coefficients.

References

- Abou-Stait, F. (2005). Are exports the engine of economic growth? An application of cointegration and causality analysis for Egypt 1997–2003. Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. 76, African Development Bank.

- Abu Al-Foul, B. (2004). Testing the export-led growth hypothesis: Evidence from Jordan. Applied Economics Letters, 11(6), 393–396.

- Abu-Qarn, A. S., & Abu-Bader, S. (2004). The validity of the ELG hypothesis in the MENA region: Cointegration and error correction model analysis. Applied Economics, 36(15), 1685–1695.

- Ahmad, F., Draz, M. U., & Yang, S. (2018). Causality nexus of exports, FDI and economic growth of the ASEAN5 economies: Evidence from panel data analysis. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 27(6), 685–700.

- Al-Yousif, K. (1997). Exports and economic growth: Some empirical evidence from the Arab Gulf Countries. Applied Economics, 29(6), 693–697.

- Al-Yousif, K. (1999). On the role of exports in the economic growth of Malaysia: A multivariate analysis. International Economic Journal, 13(3), 67–75.

- Awokuse, T. O. (2003). Is the Export-Led growth hypothesis valid for Canada?. The Canadian Journal of Economics, 36(1), 126–136.

- Awokuse, T. O. (2007). Causality between exports, imports and economic growth: Evidence from transition economies. Economic Letters, 94(3), 389–395.

- Balassa, B. (1978). Exports and economic growth: Further evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 5(2), 181–189.

- Berrill, Κ. Ε. (1960). International trade and the rate of economic growth. Economic History Review, 12(3), 351–359.

- Brown, R. L., Durbin, J., & Evans, J. M. (1975). Techniques for testing the constancy of regression relationships over time. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 37(2), 149–192.

- Chenery, H. B., & Strout, A. M. (1966). Foreign assistance and economic development. American Economic Review, 56(4), 679–733.

- Coe, D. T., & Helpman, E. (1995). International R&D spillovers. European Economic Review, 39(5), 859–887.

- Dinç, D. T., & Gökmen, A. (2019). Export-led economic growth and the case of Brazil: An empirical research. Journal of Transnational Management, 24(2), 122–141.

- Dolado, J., Jenkinson, T., & Sosvilla-Rivero, S. (1990). Cointegration and unit roots. Journal of Economic Surveys, 4(3), 249–273.

- Edwards, S. (1998). Openness and productivity: What do we really know? Economic Journal, 108(447), 383–398.

- Elbeydi, K. R. M., Hamuda, A. M., & Gazda, V. (2010). The relationship between export and economic growth in Libya Arab Jamahiriya. Theoretical and Applied Economics, 17(1), 69–76.

- El-Sakka, M. I., & Al-Mutairi, N. H. (2000). Exports and economic growth: The Arab experience. Pakistan Development Review, 39(2), 153–169.

- Emery, R. F. (1967). The relation of exports and economic growth. Kyklos, 20(4), 470–486.

- Engle, R. F. (1982). Autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity with estimates of the variance of United Kingdom inflation. Econometrica, 50(4), 987–1007.

- Feder, G. (1982). On exports and economic growth. Journal of Development Economics, 12(1), 59–73.

- Ferreira, G. F. (2009). The expansion and diversification of the export sector and economic growth: The Costa Rican experience. Ph.D. dissertation, Louisiana State University.

- Fosu, A. K. (1990). Export composition and impact of exports on economic growth of developing countries. Economics Letters, 34(1), 67–71.

- Gbaiye, O. G., Ogundipe, A., Osabuohien, E., Olugbire, O., Adeniran, O. A., Bolaji-Olutunji, K. A., … Aduradola, O. (2013). Agricultural exports and economic growth in Nigeria (1980–2010). Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 4(16), 1–5.

- Gonzalo, J. (1994). Five alternative methods for estimating long run relationships. Journal of Econometrics, 60(1), 203–233.

- Granger, C. W. J. (1969). Investigating causal relations by economic models and cross-spectral models. Econometrica, 37(3), 424–438.

- Granger, C. W. J. (1988). Some recent development in a concept of causality. Journal of Econometrics, 39(1), 199–211.

- Gylfason, T. (1999). Exports, inflation and growth. World Development, 27(6), 1031–1057.

- Herzer, D., Nowak-Lehmann, F. D., & Siliverstovs, B. (2006). Export-led growth in Chile: Assessing the role of export composition in productivity growth. Developing Economies, 44(3), 306–328.

- Hjalmarsson, E., & Osterholm, P. (2007). Testing for cointegration using the Johansen methodology when variables are near-integrated. IMF Working Paper 07/141, International Monetary Fund.

- Hosseini, S. M. P., & Tang, C. F. (2014). The effects of oil and non-oil exports on economic growth: A case study of the Iranian economy. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 27(1), 427–441.

- Jarque, C. M., & Bera, A. K. (1980). Efficient tests for normality, homoscedasticity and serial independence of regression residuals. Economics Letters, 6(3), 255–259.

- Jarque, C. M., & Bera, A. K. (1987). A test for normality of observation and regression residuals. International Statistical Review, 55(2), 163–172.

- Johansen, S. (1988). Statistical analysis of cointegrating vectors. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 12(2), 231–254.

- Johansen, S. (1995). Likelihood-based inference in cointegrated vector autoregressive models. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Johansen, S., Mosconi, R., & Nielsen, B. (2000). Cointegration analysis in the presence of structural breaks in the deterministic trend. Econometrics Journal, 3, 216–249.

- Jung, W. S., & Marshall, P. J. (1985). Exports, growth and causality in developing countries. Journal of. Development Economics, 18(1), 1–12.

- Kalaitzi, A. S., & Cleeve, E. (2017). Export-led growth in the UAE: Multivariate causality between primary exports, manufactured exports and economic growth. Eurasian Business Review, 8(3), 341–365.

- Kavoussi, R. M. (1984). Export expansion and economic growth: Further empirical evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 14(1), 241–250.

- Keller, W. (2000). Do trade patterns and technology flows affect productivity growth? World Bank Economic Review, 14(1), 17–47.

- Kim, D. H., & Lin, S. C. (2009). Trade and growth at different stages of economic development. Journal of Development Studies, 45(8), 1211–1224.

- Kindleberger, C. P. (1962). Foreign trade and the national economy. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Kohli, I., & Singh, N. (1989). Exports and growth: Critical minimum effort and diminishing returns. Journal of Development Economics, 30(2), 391–400.

- Kwan, A. C. C., & Cotsomitis, J. A. (1991). Economic growth and the expanding export sector: China 1952–1985. International Economic Journal, 5(1), 105–116.

- Lanne, M., Lütkepohl, H., & Saikkonen, P. (2002). Comparison of unit root tests for time series with level shifts. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 23(6), 667–685.

- Lee, C. H., & Huang, B. N. (2002). The relationship between exports and economic growth in East Asian countries: A multivariate threshold autoregressive approach. Journal of Economic Development, 27(2), 45–68.

- Levine, R., Loayza, N., & Beck, T. (2000). Financial intermediation and growth: Causality and causes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 46, 31–77.

- Love, J., & Chandra, R. (2005). Testing the export-led growth in South Asia. Journal of Economic Studies, 32(2), 132–145.

- Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42.

- Lutkepohl, H. (1991). Introduction to multiple time series analysis. Berlin: Springer.

- McKinnon, R. I. (1964). Foreign exchange constraints in economic development and efficient aid allocation. Economic Journal, 74(294), 388–409.

- Meier, G. M. (1970). Leading issues in economic development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Michaely, M. (1977). Exports and growth, An empirical investigation. Journal of Development Economics, 4(1), 49–53.

- Mishra, P. K. (2011). Exports and economic growth: Indian scene. SCMS Journal of Indian Management, 8(2), 17–26.

- Myint, H. (1954). The gains from international trade and backward countries. Review of Economic Studies, 22(2), 129–142.

- Myrdal, G. (1957). Economic theory and under-developed regions. London: Gerald Duckworth and Co.

- Narayan, P. K., Narayan, S., Prasad, B. C., & Prasad, A. (2007). Export-led growth hypothesis: Evidence from Papua New Guinea and Fiji. Journal of Economic Studies, 34(4), 341–351.

- Osterwald-Lenum, M. (1992). A note with quantiles of the asymptotic distribution of the maximum likelihood cointegration rank test statistics. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 54(3), 461–472.

- Panas, E., & Vamvoukas, G. (2002). Further evidence on the export-led growth hypothesis. Applied Economics Letters, 9(11), 731–735.

- Pantula, S. G. (1989). Testing for unit roots in time series data. Econometric Theory, 5(2), 256–271.

- Ramos, F. R. (2001). Exports, imports, and economic growth in Portugal: Evidence from causality and cointegration analysis. Economic Modelling, 18(4), 613–623.

- Ray, S. (2011). A causality analysis on the empirical nexus between exports and economic growth: Evidence from India. International Affairs and Global Strategy, 1, 24–39.

- Reinsel, G. C., & Ahn, S. K. (1992). Vector autoregressive models with unit roots and reduced rank structure: Estimation, likelihood ratio tests and forecasting. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 13(4), 353–375.

- Riezman, R. G., Whiteman, C. H., & Summers, P. M. (1996). The engine of growth or its handmaiden? A time-series assessment of export-led growth. Empirical Economics, 21(1), 77–110.

- Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (1995). Natural resource abundance and economic growth. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, No. 5398. Cambridge, MA.

- Saikkonen, P. (1991). Asymptotically efficient estimation of cointegrating regressions. Econometric Theory, 7(1), 1–21.

- Schwert, G. W. (1989). Test for unit roots: A Monte Carlo investigation. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 7(2), 147–159.

- Shirazi, N. S., & Manap, T. A. A. (2004). Exports and economic growth nexus: The case of Pakistan. Pakistan Development Review, 43(4), 563–581.

- Siliverstovs, B., & Herzer, D. (2006). Export-led growth hypothesis: Evidence for Chile. Applied Economics Letters, 13(5), 319–324.

- Siliverstovs, B., & Herzer, D. (2007). Manufacturing exports, mining exports and growth: Cointegration and causality analysis for Chile (1960–2001). Applied Economics, 39(2), 153–167.

- Sims, C. A. (1980). Macroeconomics and reality. Econometrica, 48(1), 1–48.

- Stock, J. H., & Watson, M. W. (1993). A simple estimator of cointegrating vectors in higher order integrated systems. Econometrica, 61(4), 783–820.

- Tang, T. C. (2006). New evidence on export expansion, economic growth and causality in China. Applied Economics Letters, 13(12), 801–803.

- Toda, H. Y., & Yamamoto, T. (1995). Statistical inferences in vector autoregressions with possibly integrated processes. Journal of Econometrics, 66(1–2), 225–250.

- Tuan, C., & Ng, L. F. Y. (1998). Export trade, trade derivatives, and economic growth of Hong Kong: A new scenario. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 7(1), 111–137.

- Vohra, R. (2001). Export and economic growth: Further time series evidence from less developed countries. International Advances in Economic Research, 7(3), 345–350.

- White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48(4), 817–838.

- World Trade Organization. (2013). International Trade Statistics 2013. Geneva, World Trade Organization. Retrieved from www.wto.org.

- Yanikkaya, H. (2003). Trade openness and economic growth: A cross-country empirical investigation. Journal of Development Economics, 72(1), 57–89.

Appendix

Table A1. Johansen’s cointegration test with one structural break (year: 1986)

Table A2. Johansen’s cointegration test with two structural breaks (years: 1986, 2001)