?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper presents new evidence on wage and price setting based on a survey of more than 300 Uruguayan firms in 2013. Most of the firms set prices considering costs and adding a profit margin; therefore, they have some degree of market power. The evidence indicates that price increases appear quite flexible in Uruguay (prices are downward rigid). Most of the firms adjust their prices on an irregular basis, which suggests that price changes in Uruguay are state-dependent, although wage changes are concentrated in January and July. Interestingly, the cost of credit is seen as an irrelevant factor in explaining price increases. We also find that cost reduction is the principal strategy to a negative demand shock, and finally, that the adjustment of prices to changes in wages is relatively quick.

1. Introduction

In recent years there has been a large increase in the empirical literature on price behavior. Following the work of Calvo (Citation1983), Taylor (Citation1980), Fuherer and Moore (Citation1995), among others, understanding the microstructure of price setting allows to define better strategies to fight price rigidity and conduct a more efficient monetary and macroeconomic policy. The micro analysis of price setting is a key factor to understand price stickiness and how monetary policy influence the economic cycle. In this sense, the macroeconomic implication of the new empirical microeconomic evidence of price rigidities is mainly the non-neutrality of monetary policy in the short term. There exist different theoretical models of price rigidities that are based on menu costs, information failures, consumer anger, rational inattention, etc. (see Nakamura and Steinsson (Citation2013) for a more complete discussion of the importance of price rigidities).

As new and detailed data sets become available, we observe important developments in the studies on the microeconomic fundamentals of price setting by retailers and their impact on inflation (Dotsey, King, & Wolman, Citation1999; Gertler & Leahy, Citation2008; Golosov & Lucas Jr., Citation2007; Klenow and Krystov Citation2008; Nakamura & Steinsson, Citation2008). These analyses allow us to better understand the behavior, dispersion, and volatility of prices.

There are, however, few studies that analyze price setting from surveys that ask companies directly about price formation, and most of the literature is concentrated on developed countries. In the case of Uruguay, despite recent progress for the retail sector (Borraz & Zipitría, Citation2012) and in wage formation (Fernández, Lanzilotta, Mazzuchi, & Perera, Citation2008), there exists little direct evidence of companies’ price formation strategies. In this study, we use a novel data set from a survey of 307 large Uruguayan firms on price setting.

An important advantage of asking firms directly about price setting instead of using micro-price datasets is that it is possible to obtain more information regarding their strategies when setting prices. This allows us to understand, for example, how firms use future, present and past information, their market behavior and their interaction with competitors.

The purpose of this study is to present stylized facts about price setting in Uruguay based on a survey of firms. Following the pioneering work of Blinder (Citation1991), we develop a survey for Uruguayan firms asking about price setting. This new evidence is a complement of the new incipient literature of price formation in developing countries. Our results would be useful for monetary policy design and to set the future agenda on the microeconomics of price setting.

The analysis of the Uruguay case allows for a deeper understanding of price formation in developing countries and is particularly interesting for several reasons. First, because of the new dimensions that the survey data brings. Second, as there are no publicly available time series data on firms´ price setting strategy in floating exchange rate regimes, this extended survey allows us to understand their behavior better, as it gathers valuable information on determinants factors to set prices. Third, the wage issue is central to macro-management when you try to anchor inflation expectations in the absence of credibility.

Our findings are as follows: i) prices in Uruguay seem to be more rigid than in previous studies, ii) the frequency of price change is state dependent, iii) the response of prices to wages is fast, iv) firms do not have a clear view on how to respond to unanticipated demand shocks (more research is needed to understand better the response of firms to unanticipated demand shocks), v) firms seem to pay more attention to wages than their weight in the cost structure would justify, a puzzling behavior that might be related to the way wage negotiations are conducted, vi) there is a high degree of inertia in the manufacturing industry sector, vii) wages may play an important role because they may provide information regarding the state of the economy, viii) there is strong evidence that firms pay the same attention to the past and future behavior of cost in setting prices, a result that is consistent with the existence of mixed Phillips curves.

The importance of our results is based on the literature of price formation and expectations. Our evidence on the temporal neutrality of expectations reinforces the idea of mixed Phillips curves, which is quite unprecedented in literature. In addition, the role of wages highlights the importance of demand signals in the absence of credible monetary policy.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 presents a brief review of related literature, section 3 makes a brief description of the data, section 4 presents the basic results of the survey, and section 5 concludes.

2. Related literature

As mentioned above, price setting literature based on company surveys is scarce and most of it is concentrated on developed countries. Blinder (Citation1991, Citation1994) was the first to use surveys to analyze the price-setting behavior of firms in the US. In his pioneering work, Blinder interviewed 200 firms directly regarding their price setting behavior to analyze the validity of sticky-price theories. He found that prices are sticky, and that the average duration of prices following a shock was of 3 months. The only theory that was supported by firms’ responses was coordination failure.

In the case of Germany, Stahl (Citation2005) finds that most manufacturing firms have market power to set producer prices. Additionally, indexation is minor. Babecký, Dybczak, and Galuščák (Citation2008) find that, in the Czech Republic, firms’ prices are less rigid than wages with a weak pass-through of wages to prices. They also find that, in response to an unanticipated demand shock, firms reduce temporary employment and non-labor costs. For fifteen European countries, Druant et al. (Citation2009) find a close relationship between wages and prices and between wages and the frequency of price changes.

In the case of Canadian firms, Amirault, Kwan, and Wilkinson (Citation2006), show a wide variation in the frequency with which they adjust prices. Almost 33% of Canadian firms declare price adjustments once a year or less while a similar portion adjust prices more than 12 times per year. Canadian firms consider wage cost as a very important factor when increasing prices. Similar studies for Swedish firms (Apel, Firberg & Hallsten, Citation2005) and Portuguese firms (Martins, Citation2005) show that firms adjust their prices only once a year. Another finding for Sweden firms is that state-dependent and time-dependent price setting are equally important.

Greenslade and Parker (Citation2012) analyzed the situation in the United Kingdom, asking companies directly how their prices behave. As with the studies mentioned above, the median number of price changes was one per year. UK firms were asked how prices were determined for their main product and the explanations that the majority of firms considered most important were competitor prices (68% of firms) and mark-up over costs (58% of firms). Another interesting result was that, in particular, labor costs and raw materials were the most important cause of price rises, whilst lower demand and competitors’ prices were the main factors resulting in price reductions. For Portuguese firms (Martins, Citation2005) it was found that more than 30% of total price changes are price decreases. Another important finding is that the degree of price stickiness seems to be higher in the service sector than in manufacturing.

Our study is also related to the extensive empirical analysis – based on microdata in recent years – that supports the rationality of state-dependent price setting as in Hobijin, Ravenna and Tambalotti (Citation2006), Klenow and Krystov (Citation2008) and Nakamura and Seteinsson (Citation2008)

In Latin America, there are two studies based on firms’ responses. Misas, López and Parra (Citation2013) study the case of Colombian firms and find that firms use time-dependent rules to adjust prices when the economy is stable. They also find that when reviewing prices, Colombian companies consider actual and expected inflation equally important. The empirical evidence also suggests that the markets where Colombian companies operate are not very competitive.

Based on a survey of 7,002 Brazilian firms, Da Silva, Petrassi, and Santos (Citation2016) find that prices are sticky, due to the fact that reviewing prices is costly, and the coexistence of state-dependent price setting and markup pricing.

3. Data

Our study is based on a survey conducted by the National Statistical Office of Uruguay (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE) in agreement with the Central Bank of Uruguay (Banco Central del Uruguay, BCU) in February 2013 on the basis of a sample that is representative of all the economy with the exception of the agriculture and the public sectors.Footnote1

Firms were selected using stratified random sampling. The stratification was made according to the number of employees (from 50 to 99; 100 to 199; 200 or more) and the economic sector of the firm, therefore only firms with 50 or more employees are in the sample. The survey was sent to 630 firms by traditional mail. A reminder was sent to those firms that had not responded. At the end, 363 valid questionnaires were received (a response rate of 58%). If a firm did not respond it was not substituted in order to avoid skewing of results. Instead the weights were reestablished. In the Appendix C, we present the survey questionnaire.

In order to have a more disaggregated analysis, we merge this survey with the yearly Economic Activity Survey, EAS (Encuesta de Actividad Económica) conducted by INE. The EAS contains information about employment, sales, investments, international trade exposure and labor force and cost structure for Uruguayan firms. The survey is conducted among all private and state-owned firms that operate in Uruguay with 5 or more employees. shows the distribution of firms in our sample by sector of activity. The most important sectors are manufacturing, with a share of 30%, and wholesale and retail with 20%.

Figure 1. Distribution by sector (in %).

4. Empirical results

This section presents the main results of the analysis of the survey on price setting practices in Uruguayan firms. We present the data with the population weights because of the very uneven non-response rate among sectors.

4.1. Price setting behavior

4.1.1. Market microstructure and price setting

We asked firms what their strategy was for setting prices. ) shows that the majority of firms, regardless of sector, set their price with a mark-up over costs, which would indicate the prevalence of imperfect competition. This is a result that is usually found in the literature (Da Siva, Petrassi, & Santos, Citation2016; Misas et al., Citation2013; Stahl, Citation2005). Also, this result holds for all economic sectors ()). Price setting based on cost and a mark-up is highest in the transportation and communication sector and in the other business sectors. As expected, manufacturing is the sector with the highest exposure to international competition ()).

Figure 2. (a) Pricing of the firm’s main product (in %). (b)Pricing of firm’s main product by sector (in %). (c) Price setting in the manufacturing industry by subsector (in %).

In ) we analyze price setting within manufacturing. Cost and mark up price setting is predominant in the heavy equipment manufacturing industry. This sub-sector also has the lowest exposure to international competition. This result reflects the high participation of heavily protected industries. Other manufacturing sub-sectors tend to find the international price more important as a reference for price setting, probably as a result of lower redundant protection. If we consider domestic and international competition, the sub-sectors that show a higher exposure are food and wood, both basic export commodities in the case of Uruguay (60% and 67% of firms respond to competition). Since the main export of goods from Uruguay are those from the food sector, the lower response to competition that the sector shows compared with exports of wood, which is puzzling in principle and deserves further research, might be related to market segmentation in some strategically important food components.Footnote2 Overall, the high percentage of firms that follow non-competitive practices might be related to the trade protection structure.

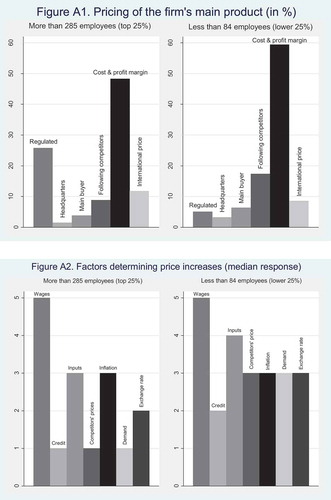

Moreover, we find that the strategy of setting prices as margins over costs is not related to the size of the firm ( in Appendix A). However, the pricing of firms that sell all of their production overseas is set by the international price and margin over costs ().

4.1.2. Frequency of price adjustment

Analyzing the frequency of price changes, indicates that 40% of firms adjust their prices semi-annually and 30% of firms do not have a regular frequency for price adjustment. This result, based on a survey of producer and consumer firms, suggests that prices are more rigid than in the findings of Borraz and Zipitría (Citation2012). They find that the median duration of prices in food, beverages and personal products in the retail sector is approximately two and a half months. The large proportion of firms claiming not to have a regular frequency of price adjustment might indicate that price adjustment opportunities arise in a random way, as in Calvo (Citation1983). This result is in stark contrast to the relatively high importance given to wages in the price formation process, particularly when wages, since Uruguay returned to centralized wage negotiations, are adjusted mostly twice a year in January and July. It would be interesting to compare wage adjustment in the sectors with the claimed frequency of price setting. As mentioned before, median Swedish (Apel, Firberg, & Hallsten, Citation2005), Spanish (Álvarez, Burriel, & Hernando, Citation2010), United Kingdom (Greenslade & Parker, Citation2012) and Portuguese (Martins, Citation2005) firms adjust their prices only once a year, which shows a difference in the frequency with which Uruguayan firms adjust their prices.

Our results suggest more frequent price adjustment than in Blinder’s survey (Citation1994) in the US. However, at the time of the survey, inflation was 8.9% annually in Uruguay, whilst that of Blinder’s paper was 3% annually in the US. Because the pressure to change prices is lower in a low inflation environment, the difference in the inflation levels between US and Uruguay can explain the discrepancy in the results.

Firms stated conduct in terms of seasonality of price adjustment is barely consistent with the marked seasonality of inflation observed in the data. In this sample, most firms do not declare a clear pattern of seasonal price adjustment.

A little more than four in ten firms (see ), mostly in the transport and real estate sectors, declare that they change their price in a particular month. The other firms do not concentrate their price changes at a specific time of the year. The percentage of firms that do not change prices in a particular month ranges from 22% for others business to 97% in the trade sector. For manufacturing industry, the percentage response is 83%. Not surprisingly, the most important months for price adjustment are January and July, which coincide with the dates of adjustments of most of the sectors in the Wages Councils ().

4.2. Factors affecting pricing

indicates that wages are the most relevant factor for firms increasing their prices. In all the different economic sectors salary was ranked as a very important factor in determining a change in the main product price. The study of Canadian firms (Amirault et al., Citation2006) also ranks wage costs as a very important factor in determining a change in price, whereas the study of Swedish firms rank it as less important. For the manufacturing industry and the trade sector, the raw materials prices are the most relevant factors determining prices.

Since raw materials include a large proportion of commodities it is also puzzling that the exchange rate plays a lesser role than wages. Ex-ante, in a small open economy like Uruguay in which most raw materials are tradables, it would be reasonable to think that firms would find changes in the value of raw materials and the dollar equally important. Another factor that would support a large role for the dollar lies in a past history of high inflation in which indexation, particularly to the dollar, was a regular practice. The lack of importance of the dollar in price formation could then be the result of lower indexation due to inflation stabilization and a floating exchange rate. This stylized fact is consistent with the fall in persistence in inflation documented by Ganon (Citation2012) among others.

Another interesting finding obtained from the survey is that finance costs do not affect prices in any economic sector. This might reflect the fact that Uruguayan firms exhibit relatively low levels of banking credit (see Banco Central del Uruguay, Citation2013b). Other factors that have little influence on the price of any economic sector are competitors’ prices, the price of the dollar and the demand. Considering that firms set their price with a mark-up, it seems reasonable to believe they do not consider the price of their competitors as a determining factor when setting prices.

Moreover, inflation is a factor that is considered very important for transport and real estate firms when changing prices, which makes sense as there are non-tradable sectors. On the other hand, as expected, manufacturing industry and the trade sector do not consider it significant.

A striking fact is the high importance given by employers to wages when determining price increases. The high importance of wages in price formation contrasts with the relatively low participation of wages in the cost structure. As can be seen in , the weight of wages on total cost averages less than 20%, while raw materials are close to 60%. One can think that this is a strategic behavior by firms because of the existence of Wage Councils that mandate wage negotiations between the employers, employees and the government. Therefore, it is possible that firms overweight the importance of wages when increasing prices. In order to check this, we compare the firms’ response with the true structure of costs from INE for the manufacturing sector. If that is the case, the high importance of wages would be an indication of the role of aggregate demand in price formation. As wages are adjusted at the same time, firms know that the dates of wage increases (January and July) are points in which aggregate demand should jump in response to the increase in household income. The contingency analysis indicates that the correlation between the perceived importance of wages and the share of wages in total cost is positive and significant but it is far from perfect.Footnote3

Table 1. Cost structure by CIIU classification (in %).

We find that the importance of wages is similar across firm size ( in Appendix A). However, firms that operate in the domestic and foreign market report that wages are as important as inflation and the exchange rate ( in Appendix B).

Additionally, because price setting is costly and prices are changed frequently when inflation is 8.9% (inflation in Uruguay when the survey was taken), it probably makes sense to adjust prices based on less than full information. In this context, wages may play an important role because they may provide information about costs, demand inflation and the state of the economy. Therefore, in countries with higher inflation, wage adjustments might tend to be dominated by indexation to inflation, a common factor for all firms in the economy.

4.3. Forward and backward looking behavior

One very important question regarding price formation is the relative role of backward and forward looking factors. Most short-term macro models are based on the existence of a Phillips curve that takes into account both past and expected fundamentals. To shed some light onto how the usual logic of monetary models fits the behavior of Uruguayan firms we compare the importance they give to the same fundamentals in past and expected terms. Surprisingly enough, six in ten (62%) firms assign the same importance to past and future values of fundamentals as can be seen in . This result is of paramount importance for the prospects of inflation targeting, since they suggest that if the Central Bank generates credibility in the conduct of monetary policy, the cost of stabilizing inflation expectation would go down significantly.

To analyze the time orientation of firms regarding different fundamental values in the margin, we construct a very simple statistic of time orientation (to):

where z indicates the fundamental factor to be considered (wages, credit, etc.), the superscript indicates time orientation (f-future, p-past), i is firm and j is sector.

For example, towages,i,j > 0 indicates that for firm i in sector j expected wage increases are more relevant to explain price increases than current and past wages.

Looking at we can see that while firms are largely neutral in the aggregate, they do not always give the same importance in every fundamental, showing in the margin a slight backward looking orientation ().

Figure 8. (a) Aggregated temporal orientation by variable. (b) Temporal orientation of firms in the price setting process by sector.

When we open the time orientation statistic by fundamental, we observe that the most important fundamentals in price setting, namely raw materials and wages, are the ones that most favor marginally past behavior ()). When we look at which sectors are forward or backward looking in the margin ()), we observe than in all sector more than half of the firms are neutral. ,b) reports the following version of the time orientation indicator

Figure 9. (a) Relative temporal orientation of firms in the price setting process by sector. (b) Temporal orientation of firms in the manufacturing sector by variable.

We compute this statistic for every firm, and the figure shows the composition of firms in terms of the sign of their time orientation. Notice that in order to classify a firm as forward or backward looking we only need that the firm give a different valuation of importance in the case of one fundamental. Since we have already documented the neutrality of firms in the aggregate, this is only a marginal indication of time orientation. With this in mind, we see that most firms are neutral in the margin as well, with the lowest and highest levels of neutrality reported in wholesale, retail and other business sectors, respectively. In all sectors, there are more backward looking firms than forward looking ones, with the highest incidence of backward looking orientation in the transport and communication sectors with 33%, and the lowest in the other business sector with 18%. The highest presence of forward looking firms occurs in trade and repairs, and the lowest in the other business sectors.

Since manufacturing is the sector in which most data are available, it is possible to observe the time orientation of the sector in terms of each fundamental. ) shows that the marginal time orientation of manufacturing firms is backward looking as well.

4.4. Prices and wages

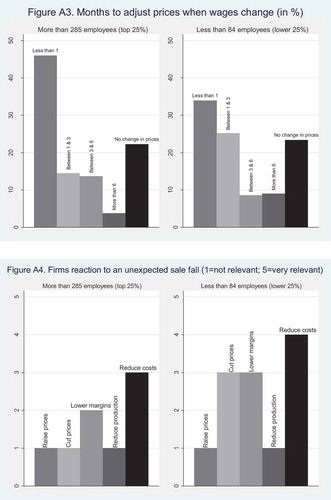

We study the speed of price adjustment after an increase in salaries in . Firms were asked to report the average time between the increase of salaries and the corresponding price reaction. Almost 60% of firms declared adjustment to their prices very quickly (less than 3 months). This result holds all firm size and it is independent of their international trade exposure ( in Appendix A and B3 in Appendix B).

Approximately 20% of firms declared no increase in prices and absorbed the costs of the salaries. This result casts doubt regarding some of the responses. These types of answer turn on an alert signal for the analysis of the surveys of firms. The design of the surveys should capture these contradictions in the answers.

The fact that we previously found that firms do not have a regular schedule for setting their prices is not contradictory with this fast pass-through of wages to prices. It may be a matter of how the firms’ managers interpreted the survey. Firms do not have a calendar date for changing prices, but they can anticipate that prices will need to be changed after wage negotiations. Therefore, prices are not really reset that often, but firms do respond quickly because they can anticipate wage changes.

4.5. Firms reaction to an unexpected demand shock

The majority of firms, when faced with a decrease in demand, tend to reduce their costs (). This strategy of cost reduction is independent of firm size and of their international trade exposure ( in Appendix A and B4 in Appendix B).

Another reaction is to disseminate the mark-up they generate, although when they have a decrease in demand they do not decrease their prices or their production. Like Blinder (Citation1994), we find that firms’ response is not symmetric to demand or supply shocks or to negative or positive shocks.

presents the contingency analysis of the correlation between the different strategies of firms to a demand shock. Suspiciously there is a highly significant positive correlation between two opposite strategies like price increases and prices reductions. This can be explained by the fact that both strategies are irrelevant for firms under a negative demand shock. This result suggests a certain amount of price rigidity.

Table 2. Firms reaction to unexpected shocks.

We find that the optimal response of the firm to a negative demand shock is not just one but a mix of strategies such as reduction of costs and margins and to some extent production.

5. Conclusions

This study provides new insights into price setting in a small economy like Uruguay, based on a survey of firms. The results indicate that prices are more rigid than previously thought and indicate a relative low degree of competition in the markets.

Firms stated conduct in terms of seasonality of price adjustment is barely consistent with the marked seasonality of inflation observed in the data. In this sample, most firms do not declare a clear pattern of seasonal price adjustment.

Another puzzle in the data is the high importance given to wages in price adjustment, which stands in stark contrast with the relatively low participation of wages in costs. This could be an indication that firms anticipate aggregate demand pressures through the behavior of wages. Also, wages may play a larger role because they may provide information about the state of the economy.

There is also a contrast between the high importance given to raw materials and the dollar in price formation. This could be the result of lower indexation due to inflation stabilization and a floating exchange rate. This stylized fact is consistent with the fall in persistence of inflation documented in Ganón (Citation2012) among others.

Another encouraging finding for monetary policy management is that firms seem to give the same importance to past and expected behavior of fundamentals in price formation. The higher the role of expected factors, the more active the expectations channel of monetary policy is.

Finally, the firms’ main response to a negative demand shock seems to be to lower costs (raise productivity).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fernando Borraz

Fernando Borraz is a Senior Economist from the economic Research Department of the Central Bank of Uruguay. He teaches econometrics at the department of economics of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University de la República and at the Universidad de Montevideo. He has a PhD in economics from Georgetown University, Washington DC, United States and had his Degree in Economics in the Universidad de la República in Uruguay.

Gerardo Licandro

Gerardo Licandro is the Manager of Economic Advisory of the Banco Central del Uruguay. He is Professor of Monetary Economics in the Universidad Católica del Uruguay and in the Universidad de la República. He has a PhD. from the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), and had his Degree in Economics in the Universidad de la República in Uruguay.

Daniela Sola

Daniela Solá is a PhD candidate in Economics at CEMFI (Centro de Estudios Monetarios y Financieros), Madrid, Spain. She started her PhD in September 2019 after finishing the Master in Economics and Finance from CEMFI. She obtained her degree in Economics from the Universidad de Montevideo in Uruguay.

Notes

1 See Banco Central del Uruguay (Citation2013a) for detailed description of the Uruguayan economy at the time of the survey.

2 The Uruguayan government has special regimes for some food commodities that have an important share of the consumption basket of the population.

3 Results available upon request.

References

- Álvarez, L., Burriel, P., & Hernando, I. (2010). Price-setting behaviour in Spain: Evidence from micro PPI data. Managerial and Decision Economics, 31(2–3), 105–121.

- Amirault, D., Kwan, C., & Wilkinson, G. (2006). Survey of price-setting behaviour of Canadian companies (Bank of Canada Working Paper) 035.

- Apel, M., Friberg, R., & Hallsten, K. (2005). Microfoundations of macroeconomic price adjustment: Survey evidence from Swedish firms. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 37(2), 313–338.

- Babecký, J., Dybczak, K., & Galuščák, K. (2008, December). Survey on wage and price formation of Czech firms (Working Paper Series 12). Czech National Bank.

- Banco Central del Uruguay. (2013a). Informe de política monetaria. Primer Trimestre 2013.

- Banco Central del Uruguay. (2013b). Reporte Anual del sistema financiero, Uruguay.

- Blinder, A. (1991). Why are prices sticky? Preliminary results from an interview study. American Economic Review, 81(2), 89–100.

- Blinder, A. (1994). On sticky prices: Academic theories meet the real world. In G. Mankiw (Ed.), Monetary policy (pp. 117–154). USA: The University of Chicago Press.

- Borraz, F., & Zipitría, L. (2012). Retail price setting in Uruguay. Economia, 12(2), 77–109.

- Calvo, G. A. (1983). Staggered prices in a utility-maximizing framework. Journal of Monetary Economics, 12(3), 383–398.

- Da Silva, A., Petrassi, B., & Santos, R. (2016). Price-setting behavior in Brazil: Survey evidence. ( Working Paper 422). Banco Central de Brasil.

- Dotsey, M., King, R. G., & Wolman, A. (1999). State-dependent pricing and the general equilibrium dynamics of money and output. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(2), 655–690.

- Druant, M., Fabiani, S., Kezdi, G., Lamo, A., Martins, F., & Sabbatini, R., (2009). How are firms’ wages and prices linked: Survey evidence in Europe (Working Paper 174). National Bank of Belgium.

- Fernández, A., Lanzilotta, B., Mazzuchi, G., & Perera, J. M. (2008). La Negociación Colectiva en Uruguay” Análisis y Alternativas. Centro de Investigaciones Económicas and Programa de Modernización de las Relaciones Laborales, Universidad Católica del Uruguay, Uruguay.

- Fuhrer, J., & Moore, G. (1995). Inflation persistence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(1), 127–159.

- Ganon, E. (2012). Persistencia de la inflación en Uruguay (Working Paper 13). Banco Central del Uruguay.

- Gertler, M., & Leahy, L. (2008). A Phillips curve with an SS foundation. Journal of Political Economy, 116(3), 533–572.

- Golosov, M., & Lucas Jr, R. E. (2007). Menu costs and Phillips Curves. Journal of Political Economy, 115(2), 171–199.

- Greenslade, J., & Parker, M. (2012). New insights into price-setting behaviour in the UK: Introduction and survey results. The Economic Journal, 122(558), F1–F15.

- Hobijn, B., Ravenna, F., & Tambalotti, A. (2006). Menu costs at work: Restaurant prices and the introduction of the Euro. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(3), 1103–1131.

- Klenow, P. J., & Kryvtsov, O. (2008). State-dependent or time-dependent pricing: does it matter for recent U.S. inflation? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3), 863–904.

- Martins, F. (2005). The price setting behaviour of Portuguese firms evidence from survey data (Working Paper Series 562). European Central Bank.

- Misas, M., Enrique López, E., & Parra, J. P. (2013). Price formation in Colombian firms: Evidence gathered from a direct survey,” Investigación Conjunta-Joint Research. Chapter 11 in L. I. D’Amato, E. L. Enciso, & M. T. Ramírez Giraldo (Eds..), Inflationary dynamics, persistence, and prices and wages formation (1st ed., pp. 251–321). Centro de Estudios Monetarios Latinoamericanos, Mexico: CEMLA.

- Nakamura, E., & Steinsson, J. (2008). Five facts about prices: A reevaluation of menu cost models. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(4), 1415–1464.

- Nakamura, E., & Steinsson, J. (2013). Price rigidity: microeconomic evidence and macroeconomic implications. Annual Review of Economics, 5(1), 133–163.

- Stahl, H. (2005). Price setting in German manufacturing: New evidence from new survey data (Discussion Paper Series 1: Economic Studies No 43). Deutsche Bundesbank.

- Taylor, J. B. (1980). Aggregated dynamics and staggered contracts. Journal of Political Economy, 88(1), 1–23.

Appendix A:

Price setting by firm’s size

Appendix B:

Price setting by firm’s international trade exposure

Appendix C:

Survey questionnaire

1) How do you set the price of the main product?

a. The price is regulated

b. The price is set in the central office abroad

c. The price is set by the main buyer

d. The price is set following competitors

e. The price is set according to costs and a profit margin

f. The price is set following the international price

2) Under normal conditions: How often does your company change the price of the main product?

a. Daily

b. Weekly

c. Monthly

d. Quarterly

e. Every six months

f. Yearly

g. There is no regular frequency

3) Under normal conditions: Are price changes concentrated in a particular month?

a. No

b. Yes. Write month/s

4) What is the relevance of the following factors to explain price increases? Grade from 1 (not relevant) to 5 (very relevant)

a. Wage increases

b. Cost of credit increases

c. Input price increases

d. Competitors’ price increases

e. Inflation increases

f. Demand increases

h. US dollar exchange rate increases

5) What is the relevance of the following factors to explain price increases? Grade from 1 (not relevant) to 5 (very relevant)

a. Expected wage increases

b. Expected cost of credit increases

c. Expected input price increases

d. Expected competitors’ price increases

e. Expected inflation increases

f. Expected demand increases

h. Expected US dollar exchange rate increases

6) How long does it take to adjust prices after a wage change?

a. Less than a month

b. Between one and three months

c. Between three and six months

d. More than six months

e. The firm does not raise prices and absorbs the increase in wages

7) What is your firm’s response to an unexpected drop in sales? Grade from 1 (not relevant) to 5 (very relevant)

1. Increase prices

2. Reduce prices

2. Reduce margin

3. Reduce production

4. Reduce costs