ABSTRACT

The Prime Minister of Hungary, Viktor Orbán, is considered to be one example of the rise of populism during the 2010s in Europe. During the decade that he has been in government, Hungary has been a forerunner in terms of democratic decline. In parallel, throughout this period, political communication has increasingly shifted online, and politicians are now actively using social media to gain political capital. Despite the growing literature on online political communication, visual political communication remains underrepresented. Orbán’s case offers a unique opportunity to examine what authoritarian populism and maintenance of illiberalism look like when a regime has been in power for more than 10 years. Using visual discourse analysis, we analyzed 131 visuals of Viktor Orbán’s Instagram from 2019. We argue that by using the symbols of nationalism and masculinity, Orbán attempts to embody the features of an “ordinary man” and also simultaneously conveys statesmanship through outlining “us” in ethno-nationalistic terms, in an effort to strengthen his party’s message, renew its hegemonic position, and to remain in power. This is in stark contrast to the communication of the Hungarian government, which relies heavily on “othering” and the construction of “them” in legacy and social media.

Populist politicians are known for being active in social media where they can set their own agenda without editorial constraints. In fact, social media ecology offers some specific affordances to populism as social media logic favors sensational and striking titles and content, and real-time expression (Hopster, Citation2021). While Twitter has been studied extensively by researchers (e.g., Ekman & Widholm, Citation2014; Ott & Dickinson, Citation2019), other platforms remain under-represented—particularly the more visual platforms—even though they have become central in social media during the past 10 years with the rise of platforms such as TikTok and Instagram.

While the importance of research on visual political communication has been recognized early on, as Bucy and Joo (Citation2021) recall, visuals have only been taken seriously in the last decade. Recent studies have explored, e.g., the strategic use of Instagram by politicians (e.g., X. Farkas & Bene, Citation2021; Liebhart & Bernhardt, Citation2017) and also visual populism. Some examples for the latter include the techniques newspapers used to construct former president of Venezuela Hugo Chávez as someone special compared to other politicians (Salojärvi, Citation2019), while Mendonça and Caetano (Citation2021) focused on how eccentricity and unsophistication are keys to Jair Bolsonaro’s performance as president in Instagram, and X. Farkas et al. (Citation2022) compared visual political communication of populists and non-populists in Facebook. Other authors explored the visual aspects of control and masculinity (Linnämäki, Citation2021) and technocratic populism during the COVID-19 crisis (Hartikainen, Citation2021), as well as the wider perspective of performativity in populism (Casullo, Citation2018; Salojärvi, Citation2020). What connects many of these studies is the underlying theme of authenticity, which helps to connect the populist leader to the authentic people they claim to represent (Caiani & Padoan, Citation2020). This authenticity can look different in every socio-cultural context (Salisbury & Pooley, Citation2017; Salojärvi, Citation2020), but the aim remains the same, to display an image that can be perceived as “real.” Social media is an ideal platform to show authenticity and realness as social media creates an illusion of a more dialogic and direct nature of communication between followers and political leaders. Nevertheless, this type of communication remains an illusion because it is predominantly top-down and unidirectional (J. Farkas & Schwartz, Citation2018).

The focus of this article is on Viktor Orbán, who, as of 2022, is the EU’s longest serving leader. Orbán has been the prime minister of Hungary with a supermajority in parliament for more than a decade. According to populist “life cycle” models (Stewart et al., Citation2003, pp. 227–229), populism can decline. To remain in power, a populist movement must maintain the populist hype (Palonen, Citation2018) to renew hegemony and antagonize the population against those who would subvert the will of “the people” (Yabanci, Citation2016). As political communication occurs increasingly on digital platforms, a politician’s social media can serve a role in such political projects. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has held office in Hungary for more than a decade. As such, his Instagram offers an opportunity to analyze his use of visuals to maintain and renew hegemony, and to ensure that his populist movement remains in power. Thus, we attempt to answer the question of what and how visual elements are used to construct Orbán’s authenticity and to contribute to (re)molding him as an embodiment of a populist movement.

Orbán’s Hungary is not only a prime example of democratic decline, but also of the establishment and maintenance of a non-democratic, authoritarian or hybrid regime. In such regimes, political competition may be real, but the broader institutional structures still favor governmental forces (Bozóki & Hegedűs, Citation2018). Consequently, while democratic change of the government is small, it still relies on the will of the people. Thus, it is important to understand how the appeal to the people is made through the construction of the leader who embodies the movement. Therefore, analyzing the performative aspects of Orbán’s Instagram can give us an insight into how such a regime can be maintained through election cycles. The electoral success of Orbán’s regime has been analyzed from many aspects, such as the concentration of power and media or the redistributive policies of the regime (Ádám, Citation2019), but less has been said about the social media performance of Orbán, or his personal character.

Populism is defined here as a particular logic of articulation that involves a construction of the people against a common political enemy, them (Laclau, Citation2005). The function of a leader in a populist movement is often to embody and symbolize the movement, representing the people. As populist leaders may be embodiments of their movement, they can signify hegemonic unity through their body and personal life (Panizza, Citation2005). Populist narratives include different types of myths, symbols, ideological themes, and rational arguments that convey the people’s past, present and future (Panizza, Citation2005, pp. 19–20). The leader may produce and repeat these narratives, that is, the leader may engage in populist meaning-making in their performance (Salojärvi, Citation2020). Authoritarian populism—which characterizes Orbán’s government—refers to a system in which political transactions largely happen in vertical power hierarchies (e.g., government-sponsored clienteles), while they maintain elections as a means of political legitimation (Ádám, Citation2019).

We first conceptualize in this article our theoretical framework of visual political communication, populism, and performativity, then describe the context of the study with regards to the media and populism in Hungary. We then analyze the data—131 visuals found on Viktor Orbán’s Instagram page from 2019—with visual discourse analysis (Rose, Citation2012). Finally, we summarize the results to determine how Orbán is constructed in these posts as an authentic political leader. Our analyses concludes that Orbán’s authenticity is constructed as a strong, masculine statesman through his outlining “us” in ethno-nationalistic terms. We suggest that this representation contributes to the success of maintaining an authoritarian populist regime.

Visual political communication

Visual symbols have long constituted an essential part of political communication, and previous research notes that visuals play an extensive role in the image-making of a political actor (Schill, Citation2012). In fact, images are more memorable and impactful than other modes of information (such as textual or vocal; e.g., Burton et al., Citation2015). Schill (Citation2012) describes several ways in which visual symbols have important functions in politics: they can appear as persuasive arguments, help with setting a political agenda, convey a dramatic or emotional appeal, create a candidate’s image, establish identification with the audience, or document a certain event. Yet, these functions predominantly apply to the mediums of television, newspapers or staged media performances (such as press conferences), where a gatekeeper is still present (such as an editorial staff; Schill, Citation2012). On social media, however, politicians and their staff have direct and full control over the content presented within the limits of platform settings. Thus, in social media the functions of visual symbols may be utilized even further.

Permanent campaigning, as a style of political communication (Agreda, Citation2013), resonates with the always-on logic of social media (Klinger, Citation2013). This can serve as an effective tool for those referred to as populist leaders and who aim for “direct” communication with their voters, often bypassing party organizations (Roberts, Citation2006, p. 136). Yet, it is important to remember that this usually does not imply that the politician communicates alone but the “direct” communication involves an increased use of media professionals. Thus, it may be assumed that a politician is not in charge of her/his media use alone.

Social media and the personalization of politics are influential changes shaping political communication in the last decade. The personalization of politics means that individual politicians are placed at the center of political communication instead of larger institutions such as parties (Langer & Sagarzazu, Citation2018). Situating sole individuals at the center of politics also increasingly leads to their portrayal as ordinary people, not as distant politicians (Jackson & Lilleker, Citation2011).

Populism and authentic performances

Populism is often viewed as (thin-)ideological content, or political style, movement, or strategy (Herkman, Citation2022). In this article, instead, we understand populism as a rhetoric-performative process which views populism as empty form to be filled with meaning. According to populist logic, it is essential to construct the sense of belonging to us, the people, as opposed to others who are perceived as enemies (Laclau, Citation2005). This involves a constant negotiation and renegotiation of meanings of different concepts that can combine collective memory, cultural aspects, values, and affect during this process (Laclau, Citation2005; Palonen, Citation2018). Visual elements also play a part in this reproduction and formation of meanings (Caiani & Padoan, Citation2020, p. 4; Salojärvi, Citation2019, Citation2020).

While populists often promise to change or transform representative democracy (e.g., Decker & Sonnicksen, Citation2011) and renew democratic institutions, while in power, these institutions often erode in their democratic quality (Ruth, Citation2018). For example, the Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez represented “revolutionary democracy,” while Viktor Orbán claimed that “a democracy does not necessarily have to be liberal. Just because a state is not liberal, it can still be a democracy” (Orbán, Citation2014). This is despite the fact that populism places “the people” on center stage, and consequently is always linked to democratic participation. Nonetheless, “the people” here do not necessarily represent the totality of the population, but “us” signifies a group that feels they represent the legitimate totality of the people (Laclau, Citation2005). Still, even in an eroded democracy, “the people” can still feel that their demands are being met by the populist leader through the leader’s rhetoric and performance.

Populist movements aim at achieving a hegemonic status in a society (Laclau, Citation2005). In the concept of hegemony, subject positions are fully dependent on political articulations, and are not predetermined by their “own nature” (Laclau & Mouffe, Citation1985, p. 23). The theory of hegemony emphasizes the never-ending, never-closing process of creating collective/popular identities as the core element for installing and reinstalling hegemony. These collective identities constitute “we” as opposed to “they” (Gencoglu, Citation2021).

Leadership in populism has been studied particularly as a personal style that entails specific body language and that is constructed by a leader’s behavior, voice, hair style, or clothing (Moffitt, Citation2016; Ostiguy, Citation2017). Nonetheless, leadership may also be interpreted as something more profound than merely style because the leader may perform as an embodiment of the movement and during this process, they construct the populist message performatively (Casullo, Citation2018; Linnämäki, Citation2021; Salojärvi, Citation2020). Thus, the leader’s body often becomes a common denominator for the movement and societal change (Casullo, Citation2018; Laclau, Citation2005), as they enter institutions of power, which have traditionally been occupied by the status-quo and elite (Casullo, Citation2018).

Authenticity is a key concept in political communication, especially when we talk about political leadership. According to Luebke (Citation2021, p. 636), authenticity is a “social construct, which is created in different communication processes among the politicians, the media and the audience.” Politicians seek to construct an authentic image of themselves (e.g., Enli & Rosenberg, Citation2018), and this can be especially important to populist politicians, who claim to represent the authentic people. Authenticity is the product of a performance, something that is done, not a preexisting quality (Alexander, Citation2004). Performing authenticity may be structured in terms of Goffman’s (Citation1974) approach in that the performance includes a frontstage that is intended for the public and a backstage that is not for the audience. In this sense, the image of a populist leader is created so that the person behind the scene is not distinguishable from the person in the scene, which creates a feeling of being real (Salojärvi, Citation2020). Social media is an ideal platform to perform this authenticity, as politicians can appear spontaneous and ordinary (e.g., Enli, Citation2015) without legacy media’s filter, and can show their backstage personality.

Politics is often regarded as a gender-neutral arena guided by rationality, but hegemonic masculinity arises as a factor that not only structures society, but politics as well. Personality cult, which is often present around populist leaders, also enforces the masculinization of politics (Löffler et al., Citation2020). The leaders of populist movements, although theoretically, are described as gender-neutral, and they often appear in a framing which features stereotypically masculine attributes (Meret, Citation2015). In addition, many populist movements and their leaders criticize feminism (e.g., Kovala & Pöysä, Citation2017) and favor traditional gender roles between men and women (Saresma, Citation2018). Masculinity can play a central role in political performances, especially in the case of populist politicians. Navera (Citation2021), for example, describes how toxic masculinity and machismo is ingrained in Rodrigo Duterte’s rhetoric, and is a long-standing presidential narrative in the Philippines. Similarly, Vladimir Putin’s and Recep T. Erdogan’s political performances build on the masculine concepts of being “bad boys” but “good fathers” to preserve a conservative political order (Eksi & Wood, Citation2019, p. 734).

Populism and media in Hungary

After Orbán served in government from 1998 to 2002, he subsequently lost two elections in 2002 and 2006; Orbán’s right-wing party, Fidesz, won the elections in 2010 with an absolute majority, which translated into a two-third supermajority in parliament. The parliamentary election in 2014, 2018, and 2022 also resulted in a landslide victory for Fidesz, preserving the supermajority in parliament. During the 12 years Orbán served as prime minister, he refined the institutional elements that he deemed to be hostile toward him. The members of the Constitutional Court were selected to be loyal to Fidesz, the electoral system was changed, the majority of media outlets were concentrated into one government-friendly conglomerate, and he has made every effort to suppress the “enemies” of the government such as the civil society, or any independent institution (Krekó & Enyedi, Citation2018). As such, Hungary also stood out as one of the worst examples of democratic decline in the 2020 report of Freedom House. This democratic decline has led to the establishment of an authoritarian populist regime, which can be characterized as an illiberal democracy with under-institutionalized minority rights, where the opposition takeover is possible, but its chances are limited (Ádám, Citation2019).

Our analysis approaches Orbán as a populist because he exhibits specific characteristics that constitute populism in the Laclaudian sense, such as his encouraging an antagonist divide between us/them and his continual need to appeal to his people. According to Laclau (Citation2005), a leader of a populist movement can become the symbol of unity. During the last 30 years of Hungarian politics, Orbán has been a key meaning-making figure. Throughout the years he has served as the prime minister of Hungary, Orbán successfully invented new dichotomies as well as oppressive others through which he could also define “us.” The creative invention of new enemies within the country and outside it, which the government and “the people” fight against, have proved to be successful in his cycles as Prime Minister since 2010 (Palonen, Citation2018). The enemies in Orbán’s and Fidesz’s discourse have been Brussels, George Soros, the EU, the critical media, NGOs, and opposition parties (Krekó & Enyedi, Citation2018). Unlike any other political party, Fidesz has been able to communicate its political messages through the government-friendly private and public media in the online and offline spheres, often through disinformation campaigns and conspiracy narratives (Szebeni et al., Citation2021). In authoritarian populism, the leader can be regarded as the modern version of the charismatic leader described by Weber (Citation1978), where political power and success derives from personal charisma (Ádám, Citation2019). In such a system, the character of the leader is pivotal, as the power they have is personalized and “the people” depend on them personally (Gurov & Zankina, Citation2013).

Data and methodology

In 2020, 79% of the Hungarian population used the Internet on all kinds of devices (Hootsuite and We Are Social, Citation2021), and 64% of these users had a Facebook account, making that platform the most popular social media site in the country (NapoleonCat, Citation2020a). The second most popular site was Instagram, as 24% of the population had an Instagram account, and it was the most popular among the 18–34-year-olds (NapoleonCat, Citation2020b). Instagram is also one of the most popular social media sites globally, as such, it can reach a worldwide audience, especially if captions are also written in English—as is the case with Orbán’s Instagram. Orbán has his own Facebook page that he posts on actively, and he began posting on Instagram in 2014; other Hungarian politicians are also increasingly present on social media platforms.

Our data consists of all Instagram posts including visuals (pictures and videos) and captions that were posted on Orbán´s public Instagram account in 2019. We selected this period for several reasons: (1) in 2019 the account had significantly more posts than previous years, and the posts became more professional in their style; (2) this was the first year after the third landslide victory of Fidesz in 2018, therefore it represents hegemonic populist leadership; (3) the posts from 2019 offer a general overview, as opposed to 2020 or 2021, in which crisis-communication and crisis-leadership became more prominent due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our analysis included pictures, videos, and the captions. Comments and likes were excluded, because we were interested in how Orbán and his party’s message are constructed by the visuals he uses, and, as comments and likes are made by other people, they are beyond the scope of this study. We analyzed a total of 131 posts on Orbán’s Instagram account; two of those posts comprised multiple pictures under the same caption and six were short videos.

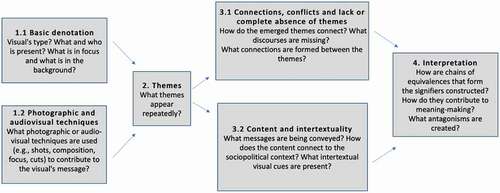

We analyzed the data qualitatively using visual discourse analysis that was completed in two parts by adapting many of the elements of Rose’s (Citation2012) discourse analysis and integrating some elements of populism as a rhetoric-performative process for the purposes of answering the research questions ().

Discourse analysis is designed to study meanings by also taking into account intertextuality, and thus, the focus is not only on the image or sites of images but on a broader discursive framing (Hand, Citation2017, p. 219). This enables us to consider not only the images but also the accompanying texts and the country-specific context of Hungary as well as related cultural and political aspects. This is important because the content of the platform needs to be analyzed by keeping in mind cultural context and technological features (Laestadius, Citation2017).

Findings

After Orbán’s long-time photographer passed away in 2017, we have not found information on who currently serves as his photographer. Needless to say, the pictures posted to Orbán’s Instagram in 2019 are seemingly professional, because the colors and compositions of the photos are uniform, which adds to the perception that it is a carefully curated album. With one exception, all are color photos. These pictures represent a diversity of photographic shots, including mainly medium shots, medium-wide shots, and wide shots. All pictures include a short caption, most of them in two languages, Hungarian and English, and a few hashtags.

Most pictures were taken in a professional setting. Of the 87 photos featuring Orbán, he appears in a more personal setting or is more casual in only 17 (15%). Orbán usually provides the image of him being “always-on,” a busy and hard-working politician who has no time for leisure activities. This is highlighted in a series of posts that Orbán made in one day. These posts allow us to follow his day in pictures with related captions, where we can read the hour and the task he is completing. The sequence consists of nine posts, portraying the image of a prime minister who works from 7.47 until 19.25, when he attends a formal dinner with guests. Orbán’s professionalism is also performed through his manner of dress. In almost all the pictures, he wears a suit and usually a tie, and his most relaxed attire is a loose-fitting white linen shirt. In one of the pictures (Item 45 in of Appendix A), however, he winks at the viewer by wearing a sport’s backpack from the European Maccabi Games 2019, which was organized in Budapest. Orbán is known for his preference for backpacks that are related to certain sport events. He usually wears them over one shoulder and travels with these backpacks to meetings abroad (Német, Citation2018). The specific discourse that arose during the analysis are the traditionally masculine leader, the nationalistic leader of Greater Hungary—referring to the state of the country prior to the Treaty of Trianon—and the internationally leading right-wing statesman.

Traditionally masculine leader

Orbán performs masculinity through the space he occupies, the people featured in the photographs with him, and through references to the military, sports, and food. One means of performing masculinity can be to take up space, meaning literally, that a person dominates the surrounding physical space, for example, by “man spreading” (Kovala & Pöysä, Citation2017, p. 261). When Orbán appears in group photos, he does not stand out (Item 50 of ) because these are usually taken at eye-level, and while Orbán may occupy a central position (Item 78), he is nonetheless merely one of the people being photographed. When photographed alone (Item 37), however, his taking up space is noticeable, enhanced by the use of a close, low angle shot. Furthermore, when he appears one-on-one with someone, he usually occupies more space (Item 39) in the photo than the other person and this is achieved through his dominant position, his placing himself in the center or by using his sheer body size to out-angle the other person.

Another means used to portray his masculinity is through the company he keeps in the images, and through the roles that women and men convey within these photographs. Women are rarely featured in his pictures and when they are, they are either foreign female politicians (such as Angela Merkel), members of a minority appearing in a group photo, or part of his personal domain. Fidesz and the government predominantly consist of men. In other words, when a group picture (Item 113) was taken at the “birthday party” of Fidesz, it depicted 26 men and 1 woman. Orbán’s cabinet meetings, or other small meetings (Item 53) always involve male politicians. In fact, if a woman politician is featured on his Instagram, she is usually foreign. Instead, women usually appear in supporting roles. For instance, Orbán’s wife is shown accompanying him to vote (Item 28) in the elections. Orbán is also depicted in Transylvania in a group picture of women dressed in traditional clothing (Item 46), where they visually represent traditional femininity and masculinity, as is typical of populist movements (Saresma, Citation2018). Men, on the other hand, are portrayed in roles that are powerful, active, and decision-making. Active characters in photographs are often perceived as more powerful than those who are static (Mandell & Shaw, Citation1973).

Orbán’s masculinity is further constructed with pictures that portray aspects of the military, sports, and food. This is in line with the military and militarism having long been associated with masculinity and male power. Indeed, military traditions have also been influential in Western cultures, which have been characterized by toughness, competition, and aggression (Godfrey, Citation2009). One picture features Orbán with Polish soldiers as he eats with them in a military tent (Item 122). Through performing militarism, Orbán evokes the masculine traits that are associated with being a soldier. This again emphasizes his activeness, that he is not only a politician who sits in an office but is also someone who is willing to go out into the field.

Orbán has been known for his obsession with football (Goldblatt & Nolan, Citation2018), which is traditionally regarded as a masculine sport, and is also immensely popular in Hungary. Through his celebrating with old football players (males only; Item 8) or his playing with a football (Item 73) on his office balcony, Orbán portrays and emphasizes a traditionally masculine image.

Food choices can convey either femininity or masculinity, as every culture has gender-stereotyped foods (Cavazza et al., Citation2017). While vegetables, sweets and light food are considered more feminine, red meat, and heavier foods are viewed as more masculine (O’Doherty & Holm, Citation1999). This means that eating masculine foods affects the audience and can invoke masculine associations. Orbán does feature food on his Instagram, and when he does, it is simple, traditional, and stereotypically masculine food—such as sausages (Item 58) or alcohol (Item 64)—which evokes “manly” connotations for his audience.

Orbán also adopts traditional masculine roles in his personal domain. While he has few pictures that include his family, he is portrayed as a father and grandfather when he hugs or poses with his grandchildren (Item 1) at Christmas. While these pictures are more intimate and aim to convey normalcy, they remain carefully staged and official, as Orbán is still wearing a suit on Christmas eve (Item 1). He also includes images of him enacting traditions. These are also based on gender, as when he sprinkles perfume (Item 98) on a little girl, which is traditionally done by men at Easter time in Hungary.

Nationalistic leader of Greater Hungary

Many of Orbán’s posts emphasize the importance of Greater-Hungary. For example, in one picture, the viewer sees a map of Greater-Hungary (Item 9) hanging on Orbán’s office wall. Greater Hungary refers to the state of the country before 1920, when—as a consequence of the Treaty of Trianon—the country lost two-thirds of its territories. A typical feature of Hungarian national identity is that national pride and grievance are compatible and are embodied in the trauma of the Treaty of Trianon (Kovács, Citation2015). Sixty-three percent of Hungarians still agree with the statement that “For those who are Hungarian, Trianon still hurts” (”Trianon” 100 MTA-Lendület Kutatócsoport, Citation2020). Trianon was already a symbol of nationalist and far-right groups and parties before 2010, but Fidesz increasingly began incorporating references to it in its political discourse after 2010. The Hungarian ex-territories now belong to Hungary’s neighboring countries, but they have Hungarian-speaking minorities. Even so, many posts on Orbán’s Instagram have cities with old Hungarian names (Item 81) in the captions rather than the current name in a current country’s language. Despite these territories not having belonged to Hungary for 100 years, Orbán’s pictures depict them as if they still exist, constructing an ethno-nationalist stance of “us.” He also personally visited (Item 101) the one millionth Hungarian who filed for citizenships from the ex-territories.

The Hungarian flag, and the national colors of red, white, and green are often featured on Orbán’s Instagram. These all contribute to his aesthetics when he delivers his speeches (Item 130); they appear as part of the office décor (Item 9) and are placed in a prominent place (Item 100) near Orbán’s balcony where he often entertains foreign guests. One of the most frequent representations of the nation is the national flag, which again signals a sense of belonging and shared national identity. This use of the flag also constructs Orbán as the leader of the Hungarian nation, for whom the nation and the homeland is most important or, as he expresses it: “The homeland above all” (Item 119).

While the communication by Fidesz refrains from promoting hardcore religious ideas, it increasingly uses religion to justify its policies and legitimacy. As the majority of Hungarians do not consider themselves religious (Bozóki & Ádám, Citation2016), a heavy emphasis on Christianity may not resonate well in the society. Instead, the government rhetoric defines the nation in terms of a mixture of Christianity, pagan symbols, and tribal traditions. For example, the newly introduced Fundamental Law is not only based on political approval, but it is also condoned by God. Hence, the law includes a paragraph, which was added in 2018, stating that it is the task of the Hungarian Government to defend Christian culture (Bozóki & Ádám, Citation2016).

Religion and Christianity are not overly emphasized in Orbán’s Instagram, but religious symbols—especially during holidays—are frequent. These include the cross and a church (Item 99) at Easter, and an open Bible (Item 2) or a picture of Bethlehem (Item 4) during the Advent period. In addition, Orbán performs Christianity in his personal life when he poses with his granddaughter at her christening (Item 69) or when he is photographed on Christmas Eve (Item 1) with his grandchildren and the caption expresses his wishes for a blessed Christmas. The strongest statement of faith among these visuals is when Orbán kneels (Item 25) in prayer with Nick Vuijicic, an Australian-American Christian evangelist and motivational speaker, and Orbán prays with his eyes closed. These aspects of religion may be considered to form a part of Hungarian national identity and this is opposed, for example, to Muslim refugees who constitute one of the enemies referred to in Orbán’s rhetoric (Krekó & Enyedi, Citation2018).

By featuring certain places or people, Orbán’s Instagram constructs who, and what belongs with “us.” Orbán is often photographed with his inner circle, including his ministers or his party. When interviewed, he also only endorses government-friendly media, such as when he grants an interview to Radio Kossuth (Item 59)—where he agrees to an interview every week to government-friendly journalists or is reading Mandiner (Item 37), a pro-government weekly newspaper. His Instagram posts also display a slice of the culture that “us” consume, such as a post with an Albert Wass quote (Item 27)—who is a Transylvanian writer favored by the right with a contested memory of him as an anti-Semite. That picture was posted after the mayor of Budapest called Albert Wass a Nazi, which makes this post one of the few that has a direct political message, but it is communicated very subtly. Orbán further associates himself with a pro-government publicist and avid fan of the alt-right, Zsolt Jeszenszky, who wears a T-shirt saying: “Has he failed yet? No he hasn’t for 3389 days” with a picture of Orbán in the Instagram picture (Item 39). This again is one of the few winks to the viewer to portray Orbán’s more relaxed side and that he can appreciate humor.

Internationally leading right-wing statesman

As a populist movement usually portrays “the people” and “the other,” we might expect to see many people in Orbán’s Instagram. Yet, ordinary people are rarely present and rarely interact with Orbán. Only two posts on his Instagram contain ordinary people: when Orbán took selfies (Item 36) with young people and when he visited an ordinary family in Vojvodina (an ex-Hungarian territory).

Thus, rather than portraying himself as a leader who is in contact with his people, Orbán is displayed more as an internationally important politician. There are numerous pictures of him traveling abroad, or meeting with foreign politicians in Budapest. Besides the ex-Hungarian territories, he is pictured when he visited Poland (Item 123), Jerusalem (Item 104), Kazakhstan (Item 96), China (Item 93), Brussels (Item 107), Italy (Item 36), and the United Kingdom (Item 19). Orbán primarily attended meetings in Hungary with politicians whom he aligned himself with, based on a similar political (populist) style, such as the former President of the United States, Donald Trump (Item 75), and Deputy Prime Minister of Italy, Matteo Salvini (Item 86). With certain politicians, a familiar relationship is implied, as in the post of Italian MEP and former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi (Item 31) stating “friends forever” or when Orbán and Brazilian politician Bolsonaro bond over a football jersey. He was also visited by Ethiopian ecclesiastical leaders (Item 62), which again indicates that according to Instagram, his important allies are populists, religious leaders or those who are from the East. Orbán does include one picture of himself with the Chancellor of Germany, Angela Merkel (Item 43) and the President of the European Commission, Ursula von Der Leyen (Item 44) as well as a group picture with NATO leaders (Item 21) in London, but these receive far less emphasis than, for example, his visit to China, which is shown in six posts instead of one. Orbán’s international image is strengthened by the English translations of almost all posts, from which we can assume that his Instagram posts are constructed with a wide audience in mind.

Discussion

By analyzing Viktor Orbán’s Instragram posts in 2019, we explored how his authenticity is constructed, and how this image helps to maintain an authoritarian populist regime in Hungary.

Hegedüs (Citation2019) reports that during the period between 2010 and 2018, the antagonistic political logic of Orbán and the Hungarian government emphasized constructing the common, public enemy—often making references throughout this period to groups such as immigrants or the EU. This trend also appears to continue after 2018 when common external enemies continue to dominate the discourse. Nevertheless, we find that Orbán’s Instagram predominantly focusses on outlining the “us” dimension of populism rather than the “them.” The idea of “us” is constructed in Orbán’s Instagram by focussing on such elements as Orbán as a masculine leader, Orbán as a leader of all Hungarians in the territory of Greater Hungary and Orbán as an international, strong statesman, an alternative to the EU leaders and liberal democracy globally. We argue that these discourses contribute to the populist articulation of constructing “us” and how the discourses allow the leader of the populist movement to perform in an authentic way.

“Us” belonging is largely constructed by highlighting national identity. Defining who belongs to the nation is strongly emphasized throughout Orbán’s use of Instagram. This is mainly achieved through banal nationalism (Billig, Citation1995; using visuals of food, sport, national symbols), Christianity, and endorsing certain people and places. By frequently featuring Hungarian ex-territories, Orbán constructs the nation in ethnonationalist terms. This national identity is constructed through the collective memory of the treaty of Trianon, which is both a source of grief and national pride. In that sense, Orbán refers to the discursive attributes of the interwar period—the “Christian-national idea” (Fekete, Citation2016, p. 1)—when Hungary was territorially larger and before the nation was dismantled.

By adding Christian references to this ethno-nationalism, Orbán creates a sacred collective identity. This Christian identity was also the basis for the anti-immigrant campaign that began in 2015, in which Hungary assumed the role of the defender of Christian Europe. Christianity and illiberalism are both performative notions that increase political polarization and provide a means to define authentic democracy as a contrast to liberal democracy, and to point out others (EU, NGOs, Soros, immigrants, etc.) as posing a threat to this idea and the sacred nation. Even though Orbán does not posts numerous religious visuals, he uses a sufficient number to signal the importance of religion and to enable him to perform as a Christian leader. While national identity is a key theme, Orbán is also portrayed as an internationally relevant right-wing leader. By featuring politically aligned leaders the logic of us versus them expands to the international sphere and can assist in the discursive battles against international others. Being on the international stage also portrays Orbán’s Hungary as an alternative to liberal democracy globally.

Along with the personalization of politics—where politicians are put in the center as opposed to institutions like parties—Fidesz colors or symbols hardly appear in Orbán’s Instagram, as all photos are concentrated on him and his performance as a leader. This is especially important as, due to the lack of everyday politics presented, he seems to be positioned above the political arena, as the embodiment of the previously outlined sacred nation.

Similarly, he is also constructed as the father of the nation through the notion of masculinity, where a patriarchal parallel can be drawn between his performance as the head of the household, and him, as head of the nation, which legitimizes his claim to protect and decide for the nation. The notion of masculinity follows Casullo’s (Citation2018) description of the functions of a populist leader’s body, where there is always something to connect to the lower traits of the people, something that differentiates him from his followers and something that displays a symbol of power. Orbán is depicted as being part of the powerful and traditionally masculine elite. This discourse also shows the second notion of Casullo; while fatherhood is a common experience, Orbán performs as the father of the whole nation, which clearly sets him apart from everyday people. At the same time Orbán is also constructed as an everyday macho, who enjoys traditionally masculine food and adores football. The familiar traditional masculine imagery then allows the people to form a connection with the leader.

The core of the populist performance is to construct an authentic image because populist leaders need to represent themselves as something different from the elite or status-quo who are viewed as something suspicious and even immoral (Laclau, Citation2005). Authenticity would imply a performance in which there is an aim to reduce the distance between followers and the politician. This can be accomplished through personal pictures (Schill, Citation2012) or pictures that present an element that is perceived to be out of ordinary in a political context, such as showing strong emotion or exhibiting some traits that are associated with ordinary people (Salojärvi, Citation2020). Out of four dimensions of performative political authenticity (Luebke, Citation2021), Orbán’s Instagram lacks intimacy and immediacy—because of the lack of spontaneity. His authenticity is, thus, created through employing different techniques conveying consistency and ordinariness. His pictures are all carefully curated, with the same style and elements, which projects reliability and consistency, and creates an image where the people know what they can expect from the politician.

While the pictures on his Instagram do not appear casual or unscripted, we do receive glimpses of the backstage of politics (Salojärvi, Citation2020) through the pictures of Orbán traveling or by seeing who he meets in Hungary or abroad as well as through everyday elements that reflect some Hungarian cultural characteristics. The same can be said regarding emotions, as Orbán’s Instagram generally incorporates a few affective-discursive practices. While pictures of traditional food or Orbán’s children may evoke a warmhearted message, the images generally do not display much emotion. This might be because emotional vulnerability is associated with hegemonic femininity (Schippers, Citation2007), thus not displaying emotions can be part of Orbán’s traditional Hungarian masculine presentation. However, just because there are few emotions present, this does not mean that Orbán’s performance does not evoke emotions in the audience. Orbán, being portrayed as a father figure for the whole nation, may arouse emotions of security among his followers.

As regards to ordinariness, small displays of everydayness are typical in the data: while Orbán is being constructed as a hard-working statesman, these small gestures portray him as an everyday guy—even though they still are notably public presentations and not private because the images are highly professional. When he is eating among other soldiers or wears a common sports backpack, his regularity is emphasized, and his lack of need for special treatment conveys that he is “one of us,” not part of the elite. Orbán also displays food populism as described by García Santamaría (Citation2020) when, through his simple food choices (Item 58), his common-person status is highlighted, thus constructing a symbolic closeness to the people.

Despite the people being an important representation in populism, they are rarely present in the visuals of the data. The Instagram itself, nonetheless as a form of media, can serve the purpose of direct interaction with the people. What we also find missing from these visuals is othering. In general, Fidesz and the government rely heavily on discursively invented enemies, against which the government protects the people (Hegedüs, Citation2019; Krekó & Enyedi, Citation2018). While these visuals, campaigns, and speeches are strongly present elsewhere in the media and are rather aggressive, they are missing from Orbán’s Instagram. Instead, what is displayed here are universally strong discourses—nation, father, and masculinity—that Orbán embodies in a culturally fitting way. Through expropriating these positions, Orbán is positioned above everyday politics and evokes one nation, one father.

To stay in power Orbán has to keep responding to the demands voiced by the people and renew hegemony, and at the same time portray security and stability. This duality is in line with the notion of paternalist populism in which the government educates, disciplines, (Enyedi, Citation2020) or defends its people.

Once in power, Orbán’s governance stabilized, institutional mechanisms were changed, and a large part of the media was overtaken, allowing him to amplify the populist logic to ensure popular support. Political change is possible, if people perceive that their demands are not heard, which would mean that the existing hegemony is not renewed. That said, Orbán named his system “illiberal” democracy, which can be understood as a performative notion, through which Orbán is able to invent dichotomies, and showcase his political project as an alternative to liberal democracy. All this contributes to his success to remain a key meaning-maker in Hungarian politics.

Conclusion

Personalization of politics (Langer & Sagarzazu, Citation2018) as well as the leader-centredness of many populist movements offer motives for populist leaders to use social media. According to Gerbaudo (Citation2018), social media can serve as an excellent tool for populist mobilization because it provides a voice for the underdogs who are unrepresented in mainstream media, and it provides a means for crowd-building by unifying divided, politically disaffected individuals around symbols and leaders.

Our study, however, presents a slightly different case, thus advancing the field of visual populist communication in several ways. First, most of the few previous studies on populist leaders and Instagram focus on leaders who are serving their first term. In the case of Viktor Orbán, we analyze a populist leader and movement that have been in power for more than a decade and aim to maintain that position.

Second, we highlight how populists in power renew their hegemonic position by showing leadership and statesmanship, while they must also display some features of an ordinary citizen to respond to people’s demands. It is therefore important to remember that hegemony, which Orbán and Fidesz are also guarding, is not passive by nature but must be “creative in its attempts to renew and defend itself” (Triece & Lacy, Citation2014, p. 10). Third, we show that since authenticity needs to be understood in its specific cultural context (Salojärvi, Citation2020), in Orbán’s performance, consistency and ordinariness are keys to his authenticity.

Fourth, as Orbán has power over most media outlets in Hungary, he does not need social media to embody the people’s voice against counter media perceived as elitist (Gerbaudo, Citation2018). Instead, his social media is utilized to channel a sense of security and to be on the top of the hegemonic transformation by focusing on the construction of “us.” During this process, Orbán adopts elements of conservative masculine representations as well as of Greater Hungarian nationalism. He, thus, represents himself as an international and powerful right-wing statesman, and the father of the nation. These representations, combined with the emphasizing “us” in his visuals creates the image of a leader above everyday politics, whose position is unquestionable.

Finally, our approach—populism as a process of political meaning making (Laclau & Mouffe, Citation1985)—highlights how us or them are not present before being articulated, and as such, they are not preexisting categories that can be applied to categorize political communication. While previous studies explicitly categorized parties as populist or non-populist, here we note that populism exists on a continuum, and all politicians—especially during a campaign—will have to make appeals to the people, and thus employ populist performances to some extent.

It should be acknowledged that the study is based on only one platform, Orbán’s Instagram, where the audience is assumed to be sufficiently diverse to include an international audience (English captions) as well as the younger population (the population that predominantly uses Instagram as compared to Facebook). Thus, his message is crafted in a specific way to appeal to these audiences and can differ from other platforms.

Populist articulation thrives on a stark division between us and them (De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Citation2017), leaving at least one of these two undefined (Palonen, Citation2020). In this case, “us,” the people, are constructed through Orbán’s Instagram, through socio-cultural elements, and by him defining the nation in ethno-nationalistic terms. This type of definition allows the creative construction of various forms of “them” and the vilification of opponents, which can contribute to maintaining an authoritarian populist regime. Yet, this division must be achieved so that it reflects authenticity in its specific cultural context. All this contributes to Orbán remaining a key meaning-maker in Hungarian politics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zea Szebeni

Zea Szebeni is a PhD researcher at the Swedish School of Social Science at the University of Helsinki in the discipline of social psychology. Her doctoral research focuses on disinformation and political polarization, especially in the context of hybrid regimes such as Hungary. She is also interested in the visual and performative strategies of online political communication.

Virpi Salojärvi

Virpi Salojärvi is an Assistant Professor in the School of Marketing and Communication at the University of Vaasa and is affiliated in the Helsinki Hub on Emotions, Populism and Polarisation at the University of Helsinki. She is a work package leader in an Academy of Finland funded project called “Whirl of Knowledge” on cultural populism in social media. Salojärvi has published on populism and polarization, conflict and media, journalists under repression, and (audio-)visual analysis.

References

- Ádám, Z. (2019). Explaining Orbán: A political transaction cost theory of authoritarian populism. Problems of Post-Communism, 66(6), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2019.1643249

- Agreda, M. J. F. (2013). Governing through permanent campaigning: Media usage and press freedom in Ecuador. University of Nevada.

- Alexander, J. C. (2004). Cultural pragmatics: Social performance between ritual and strategy. Sociological Theory, 22(4), 527–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0735-2751.2004.00233.x

- Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. Sage.

- Bozóki, A., & Ádám, Z. (2016). State and faith: Right-wing populism and nationalized religion in Hungary. Intersections, 2(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.17356/ieejsp.v2i1.143

- Bozóki, A., & Hegedűs, D. (2018). An externally constrained hybrid regime: Hungary in the European Union. Democratization, 25(7), 1173–1189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2018.1455664

- Bucy, E. P., & Joo, J. (2021). Editors’ introduction: Visual politics, grand collaborative programs, and the opportunity to think big. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220970361

- Burton, M. J. Miller, W. J., & Shea, D. M. (2015). Campaign craft: The strategies, tactics, and art of political campaign management. ABC-CLIO.

- Caiani, M., & Padoan, E. (2020). Setting the scene: Filling the gaps in populism studies. University of Salento.

- Casullo, M. E. (2018, July 25). The populist body in the age of social media: A comparative study of populist and non-populist representation. International Political Science Association Conference, Brisbane.

- Cavazza, N., Guidetti, M., & Butera, F. (2017). Portion size tells who I am, food type tells who you are: Specific functions of amount and type of food in same- and opposite-sex dyadic eating contexts. Appetite, 112, 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.019

- De Cleen, B., & Stavrakakis, Y. (2017). Distinctions and articulations: A discourse theoretical framework for the study of populism and nationalism. Javnost - The Public, 24(4), 301–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2017.1330083

- Decker, F., & Sonnicksen, J. (2011). An alternative approach to European Union democratization: Re-examining the direct election of the Commission President. Government and Opposition, 46(2), 168–191.

- Ekman, M., & Widholm, A. (2014). Twitter and the celebritisation of politics. Celebrity Studies, 5(4), 518–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2014.981038

- Eksi, B., & Wood, E. A. (2019). Right-wing populism as gendered performance: Janus-faced masculinity in the leadership of Vladimir Putin and Recep T. Erdogan. Theory and Society, 48(5), 733–751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-019-09363-3

- Enli, G. (2015). Trust me, i am authentic!”: Authenticity illusions in social media politics. In B. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbo, A. O. Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge companion to social media and politics (pp. 121–136). Routledge.

- Enli, G., & Rosenberg, L. T. (2018). Trust in the age of social media: Populist politicians seem more authentic. Social Media+ Society, 4(1), 2056305118764430. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F2056305118764430

- Enyedi, Z. (2020). Right-wing authoritarian innovations in Central and Eastern Europe. East European Politics, 36(3), 363–377.

- Farkas, X., & Bene, M. (2021). Images, politicians, and social media: Patterns and effects of politicians’ image-based political communication strategies on social media. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(1), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220959553

- Farkas, X., Jackson, D., Baranowski, P., Bene, M., Russmann, U., & Veneti, A. (2022). Strikingly similar: Comparing visual political communication of populist and non-populist parties across 28 countries. European Journal of Communication, 026732312210822. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231221082238

- Farkas, J., & Schwartz, S. A. (2018). Please like, comment and share our campaign! How social media managers for Danish political parties perceive user-generated content. NORDICOM Review, 39(2), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.2478/nor-2018-0008

- Fekete, L. (2016). Hungary: Power, punishment and the ‘Christian-national idea.’ Race & Class, 57(4), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396815624607

- Gencoglu, F. (2021). Heroes, villains and celebritisation of politics: Hegemony, populism and anti-intellectualism in Turkey. Celebrity Studies, 12(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2019.1587305

- Gerbaudo, P. (2018). Social media and populism: An elective affinity? Media, Culture & Society, 40(5), 745–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718772192

- Godfrey, R. (2009). Military, masculinity and mediated representations: (con)fusing the real and the reel. Culture and Organization, 15(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759550902925369

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis. An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

- Goldblatt, D., & Nolan, D. (2018). Viktor Orbán’s reckless football obsession. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jan/11/viktor-orban-hungary-prime-minister-reckless-football-obsession

- Gurov, B., & Zankina, E. (2013). Populism and the construction of political charisma: Post-transition politics in Bulgaria. Problems of Post-Communism, 60(1), 3–17

- Hand, M. (2017). Visuality on social media: Researching images, circulations and practices. In L. Sloan & A. Quan-Haase (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social media research methods (pp. 219). Sage.

- Hartikainen, I. (2021). Authentic expertise: Andrej Babiš and the technocratic populist performance during the COVID-19 crisis. Frontiers in Political Science, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.734093

- Hegedüs, D. (2019). Rethinking the incumbency effect. Radicalization of governing populist parties in East-Central-Europe. A case study of Hungary. European Politics and Society, 20(4), 406–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2019.1569338

- Herkman, J. (2022). A cultural approach to populism. Routledge.

- Hootsuite and We Are Social. (2021). Digital 2020: Hungary. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-hungary.

- Hopster, J. (2021). Mutual affordances: The dynamics between social media and populism. Media, Culture & Society, 43(3), 551–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720957889

- Jackson, N., & Lilleker, D. (2011). Microblogging, constituency service and impression management: UK MPs and the use of Twitter. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 17(1), 86–105.

- Klinger, U. (2013). Mastering the art of social media: Swiss parties, the 2011 national election and digital challenges. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 717–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.782329

- Kovács, É. (2015). Trianon, avagy, traumatikus fordulat” a magyar történetírásban. Korall-Társadalomtörténeti folyóirat, 59(59), 82–107. http://real.mtak.hu/31414/1/Korall_59.pdf

- Kovala, U., & Pöysä, J. (2017). Jätkät ja jytkyt populistisena retoriikkana ja performanssina. In E. Palonen & T. Saresma (Eds.), Jätkät ja jytkyt. Perussuomalaiset ja populismin retoriikka (pp. 249–272). Vastapaino.

- Krekó, P., & Enyedi, Z. (2018). Explaining Eastern Europe: Orbán’s laboratory of illiberalism. Journal of Democracy, 29(3), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0043

- Laclau, E. (2005). On populist reason. Verso.

- Laclau, E., & Mouffe, C. (1985). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical democratic politics. Verso.

- Laestadius, L. (2017). Instagram. In L. Sloan & A. Quan-Haase (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social media research methods (pp. 574–576). Sage.

- Langer, A. I., & Sagarzazu, I. (2018). Bring back the party: Personalisation, the media and coalition politics. West European Politics, 41(2), 472–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1354528

- Liebhart, K., & Bernhardt, P. (2017). Political storytelling on Instagram: Key aspects of Alexander Van der Bellen’s successful 2016 presidential election campaign. Media and Communication, 5(4), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v5i4.1062

- Linnämäki, K. (2021). Signifying illiberalism: Gender and sport in Viktor Orbán‘s Facebook photos. In O. Hakola, J. Salminen, J. Turpeinen, & O. Winberg (Eds.), Culture and politics of populist masculinities (pp. 29–48). Lexington Books.

- Löffler, M., Luyt, R., & Starck, K. (2020). Political masculinities and populism. Norma, 15(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2020.1721154

- Luebke, S. M. (2021). Political authenticity: Conceptualization of a popular term. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(3), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220948013

- Mandell, L. M., & Shaw, D. L. (1973). Judging people in the news – Unconsciously: Effect of camera angle and bodily activity. Journal of Broadcasting, 17(3), 353–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838157309363698

- Mendonça, R. F., & Caetano, R. D. (2021). Populism as parody: The visual self-presentation of Jair Bolsonaro on Instagram. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(1), 210–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220970118

- Meret, S. (2015). Charismatic female leadership and gender: Pia Kjærsgaard and the Danish People’s Party. Patterns of Prejudice, 49(1–2), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2015.1023657

- Moffitt, B. (2016). Global rise of populism: Performance, political style, and representation. Stanford University Press.

- NapoleonCat. (2020a). Facebook users in Hungary. https://napoleoncat.com/stats/facebook-users-in-hungary/2020/06

- NapoleonCat. (2020b). Instagram users in Hungary. https://napoleoncat.com/stats/instagram-users-in-hungary/2020/06

- Navera, G. S. (2021). The President as Macho: Machismo, misogyny, and the language of toxic masculinity in Philippine presidential discourse. In O. Feldman (Ed.), When politicians talk (pp. 187–202). Springer.

- Német, T. (2018, January 29). Orbán vonatjegyet vett a hátizsákjának. Index. https://index.hu/belfold/2018/01/29/orban_vonatjegyet_vett_a_hatizsakjanak/

- O’Doherty, J. K., & Holm, L. (1999). Preferences, quantities and concerns: Socio-cultural perspectives on the gendered consumption of foods. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 53(5), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600767

- Orbán, V. (2014, July 26) Full text of Viktor Orbán’s speech at Băile Tuşnad (Tusnádfürdő) of. Retrieved September 30, 2021, from https://budapestbeacon.com/full-text-of-viktor-orbans-speech-at-baile-tusnad-tusnadfurdo-of-26-july-2014/

- Ostiguy, P. (2017). Populism: A socio-cultural approach. In C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. A. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of populism (pp. 73–100). Oxford University Press.

- Ott, B. L., & Dickinson, G. (2019). The Twitter Presidency: Donald J. Trump and the politics of white rage. Routledge.

- Palonen, E. (2018). Performing the nation: The Janus-faced populist foundations of illiberalism in Hungary. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 26(3), 308–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2018.1498776

- Palonen, E. (2020). Ten theses on populism and democracy. In E. Eklundh & A. Knott (Eds.), The populist manifesto (pp. 55–69). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Panizza, F. (2005). Introduction: Populism and the mirror of democracy. In F. Panizza (Ed.), Populism and the mirror of democracy (pp. 1–31). Verso.

- Roberts, K. M. (2006). Populism, political conflict and grass-roots organization in Latin America. Comparative Politics, 38(2), 127–148. https://doi.org/10.2307/20433986

- Rose, G. (2012). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Ruth, S. P. (2018). Populism and the erosion of horizontal accountability in Latin America. Political Studies, 66(2), 356–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321717723511

- Salisbury, M., & Pooley, J. D. (2017). The# nofilter self: The contest for authenticity among social networking sites, 2002–2016. Social Sciences, 6(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6010010

- Salojärvi, V. (2019). Populism in journalistic photographs: Political leaders in Venezuelan newspaper images. Iberoamericana; Nordic Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies.

- Salojärvi, V. (2020). Populistiset miesjohtajat ja performatiivisuus: Timo Soinin, Hugo Chávezin ja Donald J. Trumpin hahmot journalistisissa kuvissa. Media & Viestintä, 43(4), 366–384. https://doi.org/10.23983/mv.100621

- Santamaría, S. G. (2020). The Italian ‘Taste’: The far-right and the performance of exclusionary populism during the European elections. Tripodos, 49, 129–149.

- Saresma, T. (2018). Gender populism: Three cases of Finns party actors’ traditionalist anti-feminism. Nykykulttuurin tutkimuskeskuksen julkaisuja, (122), 122. https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/63101/1/2018saresma.pdf

- Schill, D. (2012). The visual image and the political image: A review of visual communication research in the field of political communication. Review of Communication, 12(2), 118–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2011.653504

- Schippers, M. (2007). Recovering the feminine other: Masculinity, femininity, and gender hegemony. Theory and Society, 36(1), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-007-9022-4

- Stewart, J., Mazzoleni, G., & Horsfield, B. (2003). Media managers. The media and neo-populism: A contemporary comparative analysis (p. 217).

- Szebeni, Z., Lönnqvist, J. E., & Jasinskaja-Lahti, I. (2021). Social psychological predictors of belief in fake news in the run-up to the 2019 Hungarian elections: The importance of conspiracy mentality supports the notion of ideological symmetry in fake news belief. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.790848

- Trianon 100 MTA-Lendület Kutatócsoport. (2020). Trianon a hazai közvélemény szemében. http://trianon100.hu/attachment/0003/2255_trianon_lakossagi_survey_elemzes_final_honlapra.pdf

- Triece, M. E., & Lacy, M. G. (2014). Introduction: Gramsci, race, and communication studies. In M. G. Lacy & M. E. Triece (Eds.), Race and hegemonic struggle in the United States: Pop culture, politics, and protest. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

- Weber, M. (1978). Charisma and its transformation. In G. Roth and C. Wittich (Eds.), Economy and society. An outline of interpretive sociology (Vol. 2, pp. 1111–1157). Berkeley: University of California Press. (Original work published 1922)

- Yabanci, B. (2016). Populism as the problem child of democracy: The AKP’s enduring appeal and the use of meso-level actors. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 16(4), 591–617.

Appendix A

Table A1. The URLs of all the visuals on Viktor Orbán’s Instagram from 2019.