ABSTRACT

Individuation is the process by which humans form their perceptions about others based on a variety of unique attributes of the person. Psychological research finds that personal details can individuate a person, especially when they are perceived as atypical for the social category. We apply this logic to affective disposition theory to determine whether character individuation can influence disposition formation. Two pilot studies validated the typicality and moral irrelevance of six pairs of character details. We then deployed these details in an experiment (N = 822) in which participants viewed a biography of a fictional U.S. Marine character. We manipulated the proportion of atypical character details included in the biography in a continuous fashion. Findings indicate a positive linear relationship between the manipulation and several character perception variables. Adding discriminant validity to the findings, we found a negative relationship between the manipulation and perceived realism. Our experimental design and analyses controlled for objective similarity of the character with the participant and the moral relevance of the character details. Thus, our results suggest character individuation is a unique and previously unidentified route of disposition formation.

Acclaimed Hollywood screenwriter Blake Snyder notes the power of appealing to classic “Jungian archetypes” to captivate the imagination of viewers. Yet at the same time, he emphasizes that a writer must present unique and memorable details to help a character “stick” in an audience’s mind (Snyder, Citation2005, pp. 58, 157). This advice rests on the assumption that unique and memorable details make characters more interesting and likable (Reissenweber, Citation2003). As noted by story creators and critics (see Bal, Citation2017; Forster, Citation1956), many of the most beloved or fascinating story characters across diverse contexts – from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, to Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, to Marvel’s Loki – are built with surprising elements that serve to make the character round and engaging. The presumed effects of unique character details on character perception, as described by writers, are akin to the psychological concept of individuation, the process by which a person is perceived to be a unique individual rather than an amorphous member of a social category (see Fiske, Citation2013; Prati et al., Citation2016; Sanders, Citation2010).

Individuation can profoundly affect perceptions of other humans in non-mediated contexts (see Bandura, Citation1986; Fiske, Citation2013). Yet, empirical examinations of its influence on how audiences form perceptions of characters are entirely lacking from the literature, despite theoretical propositions of its influence (see Sanders, Citation2010). To begin to fill this gap in the literature, we examine how character individuation might influence character evaluations by incorporating it into ADT (Zillmann, Citation2000; Zillmann & Cantor, Citation1976), the most comprehensive and well-supported theory of character evaluation. Disposition formation is the subprocess of ADT that explicates how narrative consumers develop positive or negative feelings toward a character. Two mechanisms of disposition formation are posited by ADT: behavioral approbation (Zillmann, Citation2000) and schema activation (Raney, Citation2004). Both of these mechanisms – discussed further below – focus on moral judgment processes (either the moral evaluation of character behavior or the activation of moral/immoral character archetypes) and “how viewers apply them to characters” (Sanders, Citation2010, p. 148). We contend that individuating character details – even those that are not morally-relevant and not related to character archetypes and, as such, are currently unaccounted for in ADT – can systematically influence disposition formation. Observing evidence consistent with this contention would implicate character individuation as a potential third mechanism of disposition formation.

In the current paper, we report the results of an experiment that examines whether character individuation influences disposition formation, while holding behavioral morality and archetypal character schema constant. We methodically advanced to the main experiment through carefully designed, incremental pilot studies that allowed us to address three major threats to the validity of individuation manipulations in narrative contexts: (a) differences in the amount of information provided about a character, (b) the conflation of moral information with individuating information, and (c) covariation of a character’s similarity with the audience. In our main study, we test how including greater proportions of atypical attributes for a character influenced a number of character evaluations, including perceptions of characters as human (which is central to research on individuation within social psychology), disposition formation variables (e.g., liking and morality), and comparisons of characters to the self or others (e.g., perceived homophily and realism). Importantly, we measured and controlled for objective character similarity before examining the influence of our individuation manipulation, although the effect of the manipulation is robust to this control variable. Overall, our studies contribute to ADT’s theory development (DeAndrea & Holbert, Citation2017; Slater & Gleason, Citation2012) by addressing conceptual issues of disposition theorizing and extending the range of existing theory through an investigation of the unique role of character individuation in disposition formation. In addition, our findings have practical importance as they suggest a role of character individuation in narrative-induced stigma reduction (see Chung & Slater, Citation2013) and entertainment education (see Moyer-Gusé, Citation2008; Slater & Rouner, Citation2002), which we expand upon in the discussion.

Disposition Formation according to Affective Disposition Theory

Affective disposition theory (ADT; Zillmann, Citation2000; Zillmann & Cantor, Citation1976) predicts that perceptions of a character’s morality determine an audience’s positive or negative dispositions toward that character, which then combine with narrative outcomes to determine a viewer’s liking/enjoyment of the story. The behavioral approbation mechanism of disposition formation was the first to be explicitly described in ADT, with Zillmann (Citation2000) proposing a specific causal process. First, an audience observes moral or immoral behavior, resulting in approval or disapproval. Approval then results in the formation of positive dispositions, and disapproval results in the formation of negative dispositions. Thus, ADT from its inception has posited that – fundamentally – variation in the morality of characters’ actions drives audiences’ dispositions toward those characters.

In the past two decades, a number of researchers have sought to clarify and/or extend disposition theorizing (see Raney, Citation2004; Eden et al., Citation2017, Citation2011; Francemone et al., Citation2021; Frazer et al., Citation2022; Grizzard, Francemone et al., Citation2020; Grizzard et al., Citation2018; Krakowiak & Tsay-Vogel, Citation2013; Matthews, Citation2019; Oliver et al., Citation2019; Sanders, Citation2010; Shafer & Raney, Citation2012; Tamborini et al., Citation2018). Toward these goals, researchers have sought to integrate character evaluation processes that involve more than the observation of moral/immoral behavior. Raney (Citation2004; see also Sanders, Citation2010) proposed that the activation of archetypal character schema could act as a second mechanism of disposition formation. This schema activation mechanism posits that similarities among the characters found in stories allow audiences to recognize who the moral heroes and immoral villains are and to form dispositions toward them without observing character behavior. In a first empirical test of this theorizing, Grizzard et al. (Citation2018) found that even when behavior was entirely absent, characters that had a heroic appearance were rated as more moral than characters that had a villainous appearance – a finding replicated in several follow-up studies (see Francemone et al., Citation2021; Grizzard, Francemone et al., Citation2020).

We note that both mechanisms of disposition formation focus on morally-relevant variables and how they influence perceptions of a character’s morality and character liking. The behavioral approbation mechanism is based on the inherent morality/immorality of a character’s behaviors. With the schema activation mechanism, it is the presumed morality associated with character archetypes that elicits disposition formation. Thus, potential predictive factors of disposition formation beyond variance in actual or perceived morality have yet to be formally integrated into ADT (although see Francemone et al., Citation2021, for how gender can moderate the behavioral approbation mechanism). More importantly, ADT as a theory limits its discussion of causal factors of disposition formation to behavioral approbation and schema activation mechanisms. In the next section, we describe how individuation might also influence disposition formation, even when moral cues (such as character archetype and character behavior) are held constant. Overall, the goal of this paper is to investigate whether individuation can act as a mechanism of disposition formation that exists separate from the behavioral approbation and character archetype schema activation mechanisms.

Conceptualizing Character Individuation

Social psychology research suggests that individuation can determine feelings toward others. Individuation is the process by which humans form their perceptions about others based on a variety of unique attributes of the person. Individuated processing is not the default for most human perceptions of others. Impression formation research indicates that when humans first encounter information about an individual, we use this information to categorize them into a familiar “type” for which we have a preexisting set of assumptions (Fiske, Citation2013; Fiske & Neuberg, Citation1990; Sanders, Citation2010). For example, if the first detail a person learns about another is that they are a grandfather, this person will draw on their previously formed conceptions of “grandfathers” in order to understand and react to the newly-existing individual. Such processing is thought to be automatic and heuristic-based, with little cognitive effort required. Prati et al. (Citation2015, Citation2016) similarly argue that humans are wired to categorize others into groups, relying on convenient memory-based heuristics to define individuals by their most salient group membership (e.g., an Italian, a construction worker). Overall, perceiving individuals by focusing only on their most salient type or group membership is known as de-individuation (Bandura, Citation1986). As Bandura (Citation2015) notes “once people are typecast, they are treated in terms of the group stereotype rather than their personal attributes” (p. 89). Conversely, individuated processing of others occurs when heuristic-based categorizations are disrupted by encountering information that is inconsistent with categorical assumptions. Providing information that seems contrary to the category activated for an individual can break the individual from the group and force an observer to consider each unique attribute of the individual when forming a perception of them (Sanders, Citation2010). Individuated processing is thus believed to be more effortful and less heuristic-based (Fiske & Neuberg, Citation1990).

Individuation has been observed to result in deeper, more humanized perceptions of individuals (see Bandura, Citation1986). Because individuated processing requires more attention devoted to another individual and recognition of an individual’s unique attributes, it can result in greater perceptions of an individual’s humanness, depth, and even warmth (see Fiske, Citation2013). For example, counterintuitive trait combinations about a hypothetical person (e.g., a male nurse or female mechanic) have resulted in increased attribution of uniquely human traits and emotions to the individual (Prati et al., Citation2015), likely due to the individuated processing triggered by descriptions that defy quick categorization.

In the current study, we extend the individuation processes that have been observed in interpersonal contexts to narrative characters. Sanders (Citation2010) explicitly argues that impression formation logic regarding individuation (e.g. Fiske, Citation2013; Fiske & Neuberg, Citation1990) applies to both human/human interactions and human/character interactions. Providing individuating cues for narrative characters, specifically through trait information that defies a character’s social category, should promote a more humanized perception of that character. Further, person-perception research indicates that attribute-based processing associated with individuation can trigger more positive dispositions toward others, such as perceptions of a person’s warmth, likeability, or morality (see Fiske, Citation2013; Prati et al., Citation2016, Citation2015). As we discuss further below, such processes suggest the possibility of disposition formation effects of individuation in narrative contexts.

If – as has been observed in person-perception – individuation can humanize narrative characters and increase positive dispositions, then individuation is a process with theory-expanding implications for ADT. As noted in the introduction, better understanding the role of character individuation in humans’ perceptions of characters would contribute to theory (DeAndrea & Holbert, Citation2017) by addressing conceptual issues of current disposition formation theorizing and extending the range of existing theory by implicating individuation as a novel mechanism of disposition formation. However, despite a body of research demonstrating that individuating attributes affect our perceptions of other humans, the potential effects of individuating character attributes on disposition formation in narratives have yet to be fully theorized and tested. We next present research questions regarding the relationship between individuation and character perceptions, including disposition formation variables.

Individuation and Perceptions of Narrative Characters

Little is known about how individuating character details influence character evaluation variables, including (1) humanization variables, (2) disposition variables, and (3) comparison variables. Our groupings of these variables are determined by their associations with individuation as defined by social psychology (i.e., the humanization variables), disposition formation as described in ADT (i.e., the disposition variables), and perceptions of characters as compared to oneself and expectations of others (i.e., the comparison variables). Humanization variables are concepts commonly discussed or measured in social psychology literature regarding perceived humanness and anthropomorphism (see Banks, Citation2019; Gray et al., Citation2011; Haslam, Citation2006). Disposition variables are perceptions of characters that are specifically implicated in ADT (i.e., character liking and morality) and those that are commonly measured in ADT research as evidence of convergent/discriminant validity (e.g., competence, warmth, heroism; cf., Eden et al., Citation2015; Grizzard et al., Citation2018). Finally, comparison variables involve comparisons of a character to oneself (homophily; see McCroskey et al., Citation1975) and to real-life others (character realism; see Cho et al., Citation2014; Hall, Citation2003).

Individuation and humanization

According to research in social psychology (see Prati et al., Citation2016, Citation2015), providing atypical details about a character should result in increased humanization. Although there is no single standard for conceptualizing humanization in media characters, several relevant concepts have been identified in past work. Mind perception (Gray et al., Citation2011) relates to the extent that an individual is perceived as having both (a) the capacity to act, plan and exert self-control and (b) the capacity to feel emotion, pain, and pleasure. Mind perception serves as a key indicator of humanization in various psychological research contexts and translates well to mediated entities (see Banks, Citation2019). Second, Haslam’s (Citation2006) classic approach to perceived humanness includes elements of human agency, warmth, and complex emotional and cognitive abilities. Like mind perception, perceived humanness also translates well to mediated entities (see Blomster Lyshol et al., Citation2020). A third concept specifically useful for character humanization is character depth. Story creators seek to write characters that are deep and “complex; not a type but a real person” (Reissenweber, Citation2003, p. 29). Recognizing the potential of character individuation to affect humanization through these concepts, we propose our first set of research questions:

RQ 1–3: How does variation in character individuation affect an audience’s perception of a character’s mind (RQ1), perceived humanness (RQ2) and character depth (RQ3)?

Individuation and disposition formation

Disposition formation’s primary conceptual variables are perceived character morality and character liking (Zillmann, Citation2000). Research suggests that individuation and moral perceptions are often associated (see Bandura, Citation2015, Citation1986; Prati et al., Citation2016, Citation2015). Whereas de-individuated individuals may be harmed with little guilt on the part of an aggressor, people struggle to harm a victim that has been humanized (Bandura, Citation1986; Hartmann et al., Citation2010). These patterns suggest that individuation creates a more positive, morally-relevant perception of a character. Beyond morality, Sanders’ (Citation2010) extension of ADT introduced person perception variables (see Fiske, Citation2013) as potentially relevant to disposition formation. These variables, which are often measured to demonstrate convergent and discriminant validity, include perceived character warmth – the perception of a character as “agreeable and sociable” (Sanders & Ramasubramanian, Citation2012, p. 22) – as well as perceived competence and heroism (see Eden et al., Citation2015; Grizzard et al., Citation2018; Sanders, Citation2010). Thus, to systematically investigate the relationship between character individuation and both classic disposition and person perception variables, we propose the following research questions:

RQ 4–8: How does variation in character individuation affect an audience’s perception of a character’s morality (RQ4), likability (RQ5), warmth (RQ6), competence (RQ7), and heroism (RQ8)?

Individuation and comparison variables

Finally, we seek to investigate how character individuation influences comparisons of the character to oneself and to other characters. Presumably, people would conceptualize themselves as human and are familiar with their own complexities. It is plausible, then, that an individuated character may be perceived by audience members as more similar to themselves, simply because the character is more individuated, even if the character shares few objective traits. Further, character individuation may influence the extent to which a character is perceived as realistic, but the relationship here is unclear. Character realism is conceptualized to include both typicality – the idea that a character is representative of probable experiences with similar characters and individuals – and plausibility – the idea that the character could actually exist (see Cho et al., Citation2014; Hall, Citation2003). The extent to which a character is individuated may make the character seem less typical (i.e., less realistic), or conversely could make the character seem more plausible (i.e., more realistic). We thus ask:

RQ 9 and 10: How does variation in character individuation affect perceived homophily of a character (RQ9) and perceived character realism (RQ10)?

Method

Overview

To test our research questions, we took a multi-step approach that included two pilot studies and a pre-registered main experiment (see https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TUVPS). Our pilot studies sought to address a key methodological challenge: identifying atypical character details that are morally irrelevant. Our experimental study then manipulated varying proportions of the validated atypical details about a fictional character (U.S. Marine Tyler Walton) in a hypothetical television show description and measured the outcome variables raised in the research questions.

Pilot studies: establishing individuation without confounds

To avoid confounds related to quantity of information, we created pairs of corresponding character details for use in our pilot studies in which one detail was presumed typical for the character’s category (U.S. Marine) and the other atypical. Creating paired details allowed us to keep the quantity of information constant while still varying typicality. Without this element, differences in the amount of character information could have increased the time spent considering the character (Hartmann et al., Citation2010; Prati et al., Citation2016), making it difficult to know whether any observed effects were due to individuation or simple attentional processes like mere exposure (Zajonc, Citation2001). We conducted two pilot studies to ensure the pairs differed in typicality (Pilot Study 1) but did not differ in perceived morality (Pilot Study 2).

Pilot study 1: establishing the typicality/atypicality of character details

As noted earlier, providing atypical details about a person can promote individuation. For the purpose of our study, we used a hypothetical fictional TV series about the early days of the Afghanistan War and chose “U.S. Marine” as the initial character categorization (see prior research by Grizzard et al., Citation2021). We generated 18 pairs of personal details with each containing an option we conceptualized as atypical for a Marine and a parallel option we conceptualized as typical for a Marine. Examples included liking to “grill out” (typical) vs. “bake bread” (atypical) and doing “CrossFit to stay in shape” (typical) vs. “Pilates to stay in shape” (atypical). Participants (N = 466) rated the typicality of the 36 details (18 pairs) being true for a Marine. Pilot study data and more details are available in our online supplement (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8RHGJ). Overall, Pilot Study 1 resulted in the identification of 15 pairs of details that provided a clear contrast of typicality and atypicality.

Pilot study 2: establishing the lack of moral difference between character details

Pilot Study 2 sought to identify details from Pilot Study 1 that did not differ in their perceived morality. Without such pretesting, it would be impossible to know, for example, whether an audience might inherently assume that “baking bread” is a more moral activity than “grilling out.” If such a difference in moral evaluation existed, the apparent effects of an individuation manipulation, which varied such details, may actually be attributable to differences in the morality of the details used to create the manipulation. Participants (N = 309) thus evaluated the morality of the proposed details, separate from the character context. Results confirmed that six of the proposed detail pairs received nearly equivalent moral evaluations. For effect sizes associated with both pilot studies see .

Table 1. Results of pilot testing for individuation detail pairs (Typical vs. Atypical).

Main Experiment

Participants

Adults (N = 916) were recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (n = 414) and an undergraduate student participant pool at a large public U.S. university (n = 502).Footnote1 Participant data were removed if they were incomplete, indicated duplication/automation, or indicated insufficient time spent evaluating stimuli (see OSF for details on exclusion criteria), resulting in a final N of 822 (MTurk: n = 380; student pool: n = 442). As no results substantially differed between the two data sources, we combined the data for reporting purposes.

Participants (N = 822) ranged in age from 18 to 73 (M = 29; SD = 12.51), with 54.5% identifying as female, 44.4% as male, and 1.1% as transgender or gender non-conforming. In terms of race, 75.5% identified as White, 10.7% as Asian, 9.7% as Black or African American, and 3.9% as Other or another race. Politically, 46.7% identified as Democrat, 32.6% as Independent, and 20.5% as Republican. Participants’ mean political orientation was 3.27 (SD = 1.66), measured on a 1–7 scale with 1 being Very liberal and 7 being Very conservative.

Stimuli

Stimuli consisted of variations of a brief biography of the fictional character (Tyler Walton). In each condition, the biography began with a brief description of the television show, followed by a picture of Tyler and basic details about his age, height, and weight, held constant across conditions. The biographical description included a section entitled “personal life” that contained three sentences about Tyler’s hobbies and preferences. Our individuation manipulation was included in these three sentences, which revealed six personal details about Tyler (see ). For each detail (e.g., type of car Tyler owns), we used either the typical or atypical option, depending on condition, from our pilot study. (See OSF for an example stimulus.)

We varied the typical/atypical options for each detail (see ) such that all possible combinations, or versions of Tyler, were created (i.e., 7 total versions ranging from 6 atypical details and 0 typical details to 0 atypical details and 6 typical details). The specific typical/atypical details that were inserted into each of the 7 conditions were randomly selected by the survey software. Thus, the stimuli constituted 7 levels of individuation ranging from most individuated (i.e., all details were atypical) to least individuated (i.e., all details were typical).

Procedure

After giving their informed consent, participants were presented with the character biography, which was manipulated in accordance with their condition, and participants were asked to read the biography in its entirety. Following the biography, participants completed a series of character evaluation scales, presented in random order. Participants then answered a series of questions about their own moral views, personal preferences, and demographics. Finally, participants were thanked, debriefed, and provided with their agreed-upon incentive.

Measures

Mind perception

Mind perception was assessed using the 6-item Mind Scale (Gray et al., Citation2011). Sample items include “How capable of feeling pleasure do you think Tyler is?” and “How capable of exercising self-control do you think Tyler is?” All items were measured on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 Not at all to 6 Very much. For analysis, values were recoded from 0–6 to 1–7 in order to allow direct comparison with the values from the 1–7 scales measured in this study. After recoding, the mean was 5.52 (SD = 1.05; α = .87).

Perceived humanness

Perceived humanness was assessed using an 8-item scale adapted from Delbosc et al. (Citation2019). Four items were reverse coded. Sample items include “I feel like Tyler is emotional, like he is responsive and warm” and “I feel like Tyler is rational and logical, like he is intelligent.” All items were measured on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 Not at all to 6 Extremely so. For analysis, values were again recoded from 0–6 to 1–7 in order to allow direct comparison with the values from the 1–7 scales measured in this study. After recoding, the mean was 4.94 (SD = 1.09; α = .88).

Character depth

We created an 8-item scale to measure character depth. Each item was measured on a 1–7 scale, with higher values indicating higher amounts of realism. Four items were reverse-coded. Five items were measured with Likert-type response, and three were measured with semantic differential responses. Sample items includes, “Tyler seems like a one-dimensional character” (reverse-coded) and “Tyler seems like a character with a lot of depth.” A confirmatory factor analysis indicated acceptable model fit of all 8 items on a single construct (full CFA results and scale items can be viewed at OSF). Thus, we created a composite by averaging responses to the 8 items (M = 4.50, SD = 1.11, α = .87).

Character morality

Character morality was assessed using the Extended Character Moral Foundations Questionnaire (CMFQ-X; Grizzard, Fitzgerald et al., Citation2020), which has a 7-point Likert-type scale. The CMFQ-X aligns with moral foundations theory, which posits that humans make moral judgments based on five core, universal moral foundations: care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity (see Haidt & Joseph, Citation2007). The CMFQ-X thus evaluates moral perceptions of characters based on these five foundations, which are each measured in 4-item subscales. Because the character type (U.S. Marine) might be perceived as more moral on some foundations (e.g., loyalty) as compared to others (e.g., care), we analyze each of these subscales as individual outcomes. Each subscale showed acceptable reliability (care: M = 4.65, SD = 1.41, α = .89; fairness: M = 4.67, SD = 1.29, α = .89; loyalty: M = 5.58, SD = 1.01, α = .86; authority: M = 5.21, SD = 1.21, α = .84; purity: M = 5.15, SD = 1.09, α = .75). Each subscale was found to have an acceptable measurement model as evidenced by CFAs (see OSF).

Character liking

Character liking was assessed with six items (see Krakowiak & Tsay-Vogel, Citation2013). Sample items include “I like Tyler” and “I would like to be friends with someone who is like Tyler”. All items used a 7-point Likert-type scale (M = 4.95, SD = 1.10, α = .88).

Warmth

Five items assessed character warmth (see Eden et al., Citation2015; Grizzard et al., Citation2018). The statement “Tyler seems like a character who would be…” was followed by five prompts: “Warm,” “Tolerant,” “Friendly,” “Polite” and “Gentle.” Each prompt was assessed on a 7-point Likert-type scale (M = 4.69, SD = 1.18, α = .90).

Competence

Eight items assessed character competence (see Eden et al., Citation2015; Grizzard et al., Citation2018). The statement “Tyler seems like a character who would be … ” was followed by eight prompts: “Intelligent,” “Stupid” (reverse-coded), “Clever,” “Smart,” “Successful,” “Capable,” “Good at his job,” and “An expert.” Each prompt was assessed on a 7-point Likert-type scale (M = 5.32, SD = .92, α = .91).

Heroism

Heroism was assessed with a single prompt (“Heroic”) measured in the same manner as warmth and competence as described above (M = 5.08, SD = 1.29).

Perceived homophily

Perceived homophily was measured using McCroskey et al.’s (Citation1975) 4-item scale for attitudinal homophily. Items were measured on a 7-point semantic differential scale. Sample items include “Tyler … is like me/is unlike me” and “Tyler … thinks like me/does not think like me” (M = 3.10, SD = 1.47, α = .93).

Character realism

We created an 11-item scale to measure character realism. Each item was measured on a 1–7 scale, with higher values indicating higher amounts of realism. One item was reverse-coded. Five items were measured with Likert-type response, and six were measured with semantic differential responses. Sample items includes, “Tyler seems like a person you or I might actually know” and “Tyler seems like a believable character.” A confirmatory factor analysis indicated acceptable model fit of all 11 items on a single construct (full CFA results and scale items can be viewed at OSF). Thus, we created a composite by averaging responses to the 11 items (M = 5.13, SD = 1.06, α = .92).

Participant preferences

We asked participants to choose their own personal preferences regarding each potential pair of character details. Although each participant saw only one of the two options for each pair in the actual stimulus they viewed, we wanted to assess their personal preferences regarding the details given. Questions were posed as “Would you rather…” with the two options from the stimuli given, for example, “own a Ford pickup truck” or “own a Toyota Prius.” Overall, participants personally preferred the typical (for a Marine) option to the atypical option 53.75% of the time (see OSF for a breakdown for each detail).

Results

Analytical Strategy

We sought to test the causal effect of our individuation manipulation on each of the outcomes proposed in our ten research questions. To accomplish this, we engaged in a hierarchical regression procedure designed to control for differences in objective similarity between the character and the participant and identify the unique variance in outcomes caused by the manipulation.

Defining objective similarity through matched preferences

We recognized that the randomly selected character details might relate differently to participants’ own preferences and lifestyle (e.g., some participants might be presented with a character that matched their own preferences while other might be presented with a character that deviated from their own preferences). We further recognized that participants might evaluate characters differently simply because they shared or did not share certain preferences/hobbies with the character. We thus devised a method to control for variance caused by objective similarity between character and participant.

Using the Participant Preferences variables described above, we created a Matched Preferences variable. This variable was operationally defined as the number of personal preferences of the participant that matched the details of the character bio for each individual participant. Thus, each individual had a score ranging from 0 to 6 on the Matched Preference variable, with 0 indicating that none of the participants’ personal preferences matched those of the character (minimum objective similarity) and 6 (maximum objective similarity) indicating that all of the participant’s personal preferences matched (M = 3.04; SD = 1.34).

Regression model approach

We ran two linear regression models for each outcome and examined changes in explained variance.Footnote2 Model 1 predicted outcome by Matched Preferences. Model 2 predicted outcome by both Matched Preferences and number of Atypical Details (our experimental manipulation, ranging from 0 to 6 as described above). Thus, following the procedure of hierarchical regression, the ΔR2 from Model 1 to Model 2 represents the amount of unique variance in the outcome variable explained by our manipulation (Atypical Details), separate from any variance explained by objective similarity (Matched Preferences), which is accounted for in Model 1.

Regression Model Results and Interpretation

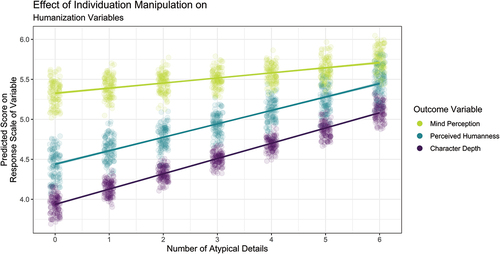

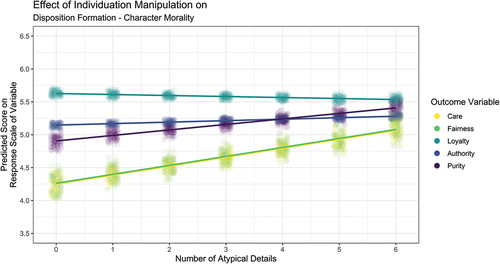

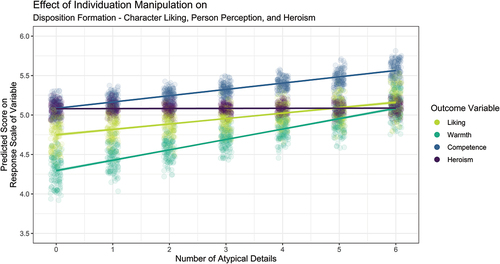

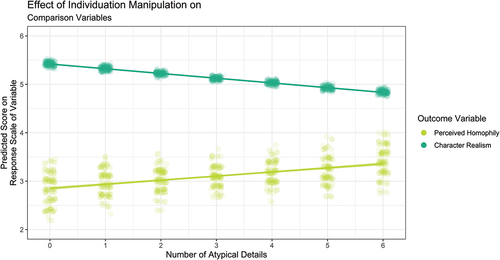

Results from the regression models are presented in . These tables report R2 and significance of Model 1, change in R2 and significance for Model 2, and betas and significance for predictors. Each table is associated with a set of dependent variables and the relevant research questions. Visual depictions of the regressions are displayed in .

Table 2. Regressions testing RQ1 – RQ3.

Table 3. Regressions testing RQ4.

Table 4. Regressions testing RQ5 – RQ8.

Table 5. Regressions testing RQ9 and RQ10.

Figure 1. Visual depiction of regression of humanization variables on individuation manipulation. See for statistical results.

Figure 2. Visual depiction of regression of character morality variables on individuation manipulation. See for statistical results.

Figure 3. Visual depiction of regression of disposition formation variables on individuation manipulation. See for statistical results.

Figure 4. Visual depiction of regression of comparison variables on individuation manipulation. See for statistical results.

Effect of individuation manipulation on humanization (RQ1 – RQ3)

Our first three research questions asked how variation in character individuation – manipulated here as atypical details about a character – affects an audience’s perception of a character’s mind (RQ1), humanness (RQ2), and depth (RQ3) (see ; see ).

Mind perception

Our findings indicate that atypical character details are significantly associated with increased mind perception of a character. This finding is supported by the regression models which show that even after controlling for matched preferences, there is a significant positive relationship between atypical character details and mind perception. Model 1, which only contains matched preferences, explains 1.2% of the variance in mind perception. When atypical character details are entered as a predictor in Model 2, the amount of variance more than doubles to 2.9% (see ; see ). Answering RQ1, the number of atypical character details leads audiences to perceive a character as having a greater capacity to act, plan, and exert self-control, as well as feel emotion, pain, and pleasure.

Humanness

Our findings further show that atypical character details are significantly associated with increased perceived humanness of a character, even after controlling for matched preferences. Model 1, which only contains matched preferences, explains 1.2% of the variance in humanness. When atypical character details are entered as a predictor in Model 2, the amount of variance explained increases to more than 11% (see ; see ). Answering RQ2, the number of atypical character details increases an audience’s perception of a character as possessing human nature and uniquely human attributes.

Depth

Finally, our findings indicate that atypical character details are significantly associated with increased perceptions of character depth, even after controlling for matched preferences. Model 1, which only contains matched preferences, explains less than 1% of the variance in character depth. When atypical character details are entered as a predictor in Model 2, the amount of variance explained increases to more than 12% (see ; see ). Answering RQ3, the number of atypical character details increases an audience’s perception of a character as round and complex, rather than shallow and typical.

Effect of individuation manipulation on disposition formation (RQ4 – RQ8)

Our second set of research questions asked how variation in character individuation affects classic disposition formation variables and person perception variables related to character schema: character morality (RQ4), character liking (RQ5), warmth (RQ6), competence (RQ7), and heroism (RQ8) (see ; see ).

Character morality

Overall, the control variable (matched preferences) did not significantly predict any of the five moral foundations. However, our individuation manipulation positively predicted 3.9% of the variance in the care foundation, 4.7% of the variance in the fairness foundation, and 2.5% of the variance in the purity foundation (each of which was a highly significant effect; p < .001), with atypical details leading to greater perceived morality (see ; see ). The number of atypical details did not significantly predict either the loyalty foundation or the authority foundation, however. Thus, in answer to RQ4, the number of atypical character details increases audiences’ assessment of characters’ morality in the areas of care, fairness, and purity, but not in the areas of loyalty and authority. We note here that loyalty and authority are perhaps the most important moral foundations for a military character to uphold, and so a lack of a significant effect on these two variables may be specific to this type of character.

Character liking

Our findings show that atypical character details are significantly associated with increased character liking, even after controlling for matched preferences. Model 1, which only contains matched preferences, explains 1.6% of the variance in character liking. When atypical character details are entered as a predictor in Model 2, the amount of variance explained increases more than double to 3.5% (see ; see ). Answering RQ5, the number of atypical character details increases audiences’ liking of a character.

Warmth

Our findings further show that atypical character details are significantly associated with increased perceptions of character warmth, even after controlling for matched preferences. Model 1, which only contains matched preferences, explains 1.1% of the variance in warmth. When atypical character details are entered as a predictor in Model 2, the amount of variance explained increases more than five-fold to 6.6% (see ; see ). Answering RQ6, the number of atypical character details increases an audience’s perception of a character as warm, tolerant, friendly, polite, and gentle.

Competence

Our findings show that atypical character details are significantly associated with increased perceptions of character competence, even after controlling for matched preferences. Model 1, which only contains matched preferences, explains less than 1% of the variance in warmth. When atypical character details are entered as a predictor in Model 2, the amount of variance explained increases to 3.9% (see ; see ). Answering RQ7, the number of atypical character details increases an audience’s perception of a character as competent, which includes being intelligent, capable, and good at one’s job.

Heroism

Finally, our findings show no evidence of a significant relationship between atypical character details the perception of a character as heroic. Model 1, which only contains matched preferences, explains an insignificant amount of the variance in heroism. Further when atypical character details are entered as a predictor in Model 2, the amount of variance explained remain non-significant. Answering RQ8, atypical character details do not increase or decrease perceptions of a character as heroic (see ; see ).

Effect of atypicality manipulation on comparison variables (RQ9 and RQ10)

Our final two research questions asked how variation in character individuation – manipulated here as atypical details about a character – affects an audience’s perception of a character’s homophily (meaning, perceived similarity to the audience member; RQ9) and character realism (RQ10) (see ; see ).

Perceived homophily

Our findings indicate that atypical character details are significantly associated with increased perceived homophily, even after controlling for matched preferences. Model 1, which only contains matched preferences, explains 2.9% of the variance in perceived homophily. When atypical character details are entered as a predictor in Model 2, the amount of variance increases to 4.6% (see ; see ). Answering RQ9, the number of atypical character details leads audiences to perceive a character as being more similar to them, even when controlling for objective similarity in preferences (matched preferences).

Character realism

Our findings further show that atypical character details are significantly associated with decreased perceptions of character realism, even after controlling for matched preferences. Model 1, which only contains matched preferences, explains minimal variance in character realism (R2 = .002). When atypical character details are entered as a predictor in Model 2, the amount of variance explained increases to 3.5% (see ; see ). Answering RQ10, the number of atypical character details decreases an audience’s perception of character realism, which is conceptualized as the typicality and plausibility of a character.

Discussion

Our experiment provides initial evidence that character individuation through the inclusion of atypical details affects various character perception variables. The variables include character liking and character morality – the two most central variables of disposition formation in ADT. Importantly, neither the behavioral approbation mechanism nor the character archetype schema activation mechanism of disposition formation can account for the variance in character perceptions explained by our study’s individuation manipulation, as both mechanisms were held constant by our study’s design. The careful pre-registered experimental design of our study, along with the dose-dependent nature of the observed effects, lends credence to causal inference. Although we acknowledge that this study is a single observation of character individuation influencing disposition formation, the strength of our design and findings suggests the need for future research testing this mechanism in a variety of settings and with new stimuli. In the following sections, we first discuss the observed effects of character individuation on humanization variables and comparison variables. We then describe implications of these findings for ADT and present future research directions based on limitations of our study.

Individuation and Humanization Variables

The individuation manipulation increased perceptions of mind, perceived humanness, and character depth for our target character, suggesting that individuated characters seem more lifelike for audiences. The fact that seemingly trivial information about a character’s preferences explained over 10% of variance in perceptions of a character’s depth and humanness raises the question of how individuated versus de-individuated characters are processed differently in the human mind. These findings may provide indirect evidence of more effortful, attribute-based processing associated with individuation, consistent with predictions offered by Sanders (Citation2010) in her character impression formation model. Although our current investigation does not speak to the internal processes driving these results, future research could examine evidence of effortful processing, such as response latencies or psychophysiological measures of attention.

Individuation and Comparison Variables

Further, we found that individuating details also explained variance in comparison variables. Importantly, individuation positively predicted perceived homophily with a character, even though we controlled for objective similarities between the character and participant. This finding points to the power of individuation for determining how individuals think of a character in relation to themselves. Such an effect has important implications for not only ADT, but also narrative persuasion (see Moyer-Gusé, Citation2008; Slater & Rouner, Citation2002). Seeing similarities between oneself and a character should lead to stronger effects in narrative persuasion settings (see Kužmičová & Bálint, Citation2019), especially if seeing similarities results in increased relevance of the message. If the characters within an entertainment-education message are perceived as having higher relevance to the audience, then components of the message targeting attitudinal shifts should also be perceived as having higher relevance. The fact that individuation fosters perceived homophily, even after accounting for objective similarity, suggests that individuation could be an important element for narrative interventions that seek to promote empathy toward and understanding of stigmatized outgroups (see Chung & Slater, Citation2013). We encourage further research to test the boundaries and potentially diverse applications of this observed phenomenon.

The significant negative relationship between individuation and character realism, conceptualized here as the typicality and plausibility of a character, further establishes the discriminant validity of our character evaluation measures. This finding was not unexpected, given that individuation was manipulated precisely by making the character appear atypical compared to a U.S. Marine character archetype. But the fact that an individuated character was perceived as less realistic yet simultaneously more moral, liked, and deep suggests character realism may not be of predominate importance in the disposition formation process.

Implications of Our Findings for ADT

The individuation manipulation predicted increased perceptions of character morality, liking, warmth, and competence. Crucially, this finding was robust even though our design was careful not to vary the morality of a character’s behavior or to confound individuation with objective similarity between character and audience. Thus, our study provides initial evidence that character individuation may play an important causal role in disposition formation that complements but is distinct from previously theorized mechanisms.

Further, variance in individuation’s effect across the five sub-components of character morality is noteworthy. Individuation was a significant and substantial positive predictor of care, fairness, and purity evaluations, but it had no significant effect on loyalty or authority evaluations. These differences in effect indicate that participants were distinguishing between moral foundations and not simply rating individuated characters higher on all measures of morality. We suspect that the elements of loyalty and authority, which were the highest-rated morality sub-components across condition, are the most salient forms of morality for the U.S. Marine archetype. The increased salience of loyalty and authority for U.S. Marines and their resistance to influence through individuating cues suggests that perhaps some moral foundations are so closely tied to a character type that individuation will have little effect on them. For example, individuating a protagonist who is a nurse may not lead to increased moral evaluations of the character as caring, whereas individuating a protagonist who is a judge may not lead to increased moral evaluations of the character as fair.

ADT is inherently a theory of narrative enjoyment. According to recent theoretical syntheses (see Raney, Citation2020; Tamborini et al., Citation2021), the three central processes of ADT are (a) disposition formation (how viewers come to like and dislike characters), (b) anticipatory responses (how potential narrative outcomes influence hopes and fears for character fates), and (c) outcome evaluation (how viewers evaluate the good and bad things that befall characters). Our study focused solely on the disposition formation process of ADT, which is why our stimuli included only a simple narrative context rather than a full narrative plot. We found that character individuation influenced character dispositions. Although these dispositions were formed outside of and prior to a full narrative plot, dispositions formed in this manner still have relevance for ADT. Raney (Citation2004) suggests viewers can form initial character dispositions quickly, biasing future evaluations of a character as the plot unfolds. Empirical tests of these predictions (Grizzard et al., Citation2018; Grizzard, Francemone et al., Citation2020; see also Francemone et al., Citation2021) found that dispositions formed prior to exposure to a narrative plot have influences on perceptions of character behaviors that occur during a narrative plot. Further, the dispositions formed prior to narrative exposure can create a desire to engage with the full narrative. For example, people frequently encounter brief descriptions of story characters in movies reviews, advertisements, social media posts, and even conversations. Raney (Citation2004) notes that humans have a strong desire to enjoy the narratives they consume, and we thus “seek out media products we think will help us reach this ultimate goal of enjoyment” (p. 348). Thus, the impressions of a narrative character formed through even brief exposure to a review, an advertisement, or a social media post about a character are likely to impact a person’s choice of whether or not to engage with a narrative.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

An immediately obvious future research direction for character individuation informed by limitations of our study design relates to how individuation that occurs prior to a full narrative plot interacts with full narrative exposure. It seems plausible that early character individuation could become overwhelmed by unfolding character behaviors and narrative events. Conversely, it is also plausible that early character individuation could bias and alter the evaluations of subsequent character behaviors and events, similar to the effects of character schema activation (Grizzard et al., Citation2018). For example, a morally questionable behavior enacted by an individuated character may lead to more approval than the same behavior enacted by a de-individuated character. These empirical questions should be examined in future research.

Other questions regarding character individuation and full narrative exposure are also generated by our findings. As suggested by the dose-dependent relationships observed here, character individuation seems to be a continuous and cumulative process. However, the current methodology, which used brief character biographies, cannot assess the effects of individuating information that is revealed throughout an ongoing narrative plot. As described in Sanders’ (Citation2010) character impression formation model, exposure to character behaviors and events as they unfold during a narrative can have two effects. First, new character information encountered during the narrative plot can reinforce type-casting categorizations and affirm a de-individuated perception of the character (e.g., when the behaviors and events are perceived to be typical for the character). Alternatively, information encountered during the narrative plot can challenge type-casting categorizations, force attribute-by-attribute processing of the character, and lead to a more individuated perception of the character (e.g., when the behaviors and events are perceived to be atypical). Future research can help understand these processes in greater depth by measuring variables relevant to character individuation or by manipulating character behaviors and events in a narrative plot to induce character individuation/de-individuation. Research in this vein would also be informative for questions regarding more serialized forms of narrative (e.g., the Marvel Cinematic Universe) where characters are encountered repeatedly and often demonstrate great change throughout. Audiovisual narratives, such as serialized television dramas, may also have unique features that require further consideration with regard to character individuation.

In addition to the points just discussed regarding individuation in relation to a full narrative plot, we posit three additional future research directions. First, we encourage future research that tests and models the potential multi-step processes by which an individuated character description affects dispositional outcomes. Our current study was largely exploratory, seeking only to test the direct relationships between character individuation and character perception variables. However, future research should consider the temporal process that may be occurring within these outcome variables. For example, it is plausible that an individuated character description causes increased perceptions of humanness of the character, which in turn leads to more positive dispositions (i.e., morality and liking). Conversely, morality and liking may precede perceptions of humanness in causal order. Initial post-hoc path analyses that we have conducted on these data indicate the former may be more likely than the latter (see OSF). In addition, other variables (such as perceived novelty) may also be impacted by character individuation. Future research should compare competing serial causal models and utilize multiple measurement points to assess potential causal processes.

Additionally, comparing the effect sizes of disposition formation through individuation, schema activation, and behavioral approbation can help contextualize the importance of each route. The effect sizes for individuation in our study ranged from R2 = .03 to R2 = .12. Comparing our individuation manipulation’s effect sizes to other effect sizes within media psychology research indicates that they range from small to large (see Weber & Popova, Citation2012). Yet, it is unclear how the effect sizes for the three potential routes of disposition formation would compare to each other. Extant research does not allow for a clean comparison of these effect sizes. For example, Francemone et al. (Citation2021) found that schema activation using heroic-looking versus villainous-looking characters was associated with a partial eta-squared of .38 and behavioral approbation of more versus less moral behaviors was associated with a partial eta-squared of .25, both much larger than what we found for individuation. However, a direct comparison of these effect sizes to the effect sizes of individuation is not warranted due to differences in stimuli. In Francemone et al. (Citation2021), participants were evaluating the stimuli based only on changes in the visual depiction of the character and the behavior of the character. Here, our stimuli includes additional information (e.g., that the character was a U.S. Marine, fighting in the Afghanistan War) which would be expected to influence participants’ disposition formation process in addition to the individuation manipulation. Thus, the only clear way to establish the relative strength of the various routes of disposition formation is to test them in a combined study that manipulates each independently. These studies could also aid in addressing a final limitation.

Finally, we urge future researchers to test interactions between individuation and the two other mechanisms of disposition formation: behavioral approbation and schema activation. Our current study is limited in that it presented a protagonist who was associated with a positive character archetype and who garnered overall positive evaluations across conditions. However, individuation could plausibly result in different effects for a villainous/immoral character. Particularly because mind perception and humanness are associated with moral agency (see Gray et al. Citation2011), it is plausible that an audience could cast more moral blame on an individuated villain than a de-individuated villain. In the case of a villainous character, we might expect individuation to increase mind perception, humanness, and competence, while simultaneously decreasing perceived character morality and warmth. These empirical questions require additional research.

Conclusion

The current paper presents the results of a carefully conducted series of studies examining a new theoretical route of disposition formation: character individuation. Results suggest character individuation has effects on character disposition variables that cannot be accounted for by either behavioral approbation or schema activation. These findings provide novel routes of theorizing for ADT, as well as exciting new research directions.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8RHGJ and https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TUVPS.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The data described in this article are openly available in the Open Science Framework at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8RHGJ.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This research study was determined exempt from Institutional Review Board review at The Ohio State University, protocol number #2021E0196.

2. We examined both a linear effect and a quadratic effect of the manipulation, as specified in our pre-registration. We reasoned that there may be a “sweet spot” for character atypicality on outcomes where an entirely atypical character is perceived to be less realistic, liked, and the rest as compared to a moderately atypical character. Our analyses did not bear out such speculation, and instead we found that the linear effect always explained more variance than the quadratic effect. We further note that the p-p plots suggest that the residuals from our linear regression were normally distributed, further justifying our use of a linear model. See OSF for histograms of the residuals and p-p plots. We also conducted robustness checks on our regressions using additional demographic/psychographic measures. See Appendix A OSF.

References

- Bal, M. (2017). Narratology: Introduction to the theory of narrative (4th ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall.

- Bandura, A. (2015). Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. Worth Publishers.

- Banks, J. (2019). A perceived moral agency scale: Development and validation of a metric for humans and social machines. Computers in Human Behavior, 90, 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.028

- Blomster Lyshol, J. K., Thomsen, L., & Seibt, B. (2020). Moved by observing the love of others: Kama muta evoked through media fosters humanization of out-groups. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(1240). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01240

- Cho, H., Shen, L., & Wilson, K. (2014). Perceived realism: Dimensions and roles in narrative persuasion. Communication Research, 41(6), 828–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212450585

- Chung, A. H., & Slater, M. D. (2013). Reducing stigma and out-group distinctions through perspective-taking in narratives. Journal of Communication, 63(5), 894–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12050

- DeAndrea, D. C., & Holbert, R. L. (2017). Increasing clarity where it is needed most: Articulating and evaluating theoretical contributions. Annals of the International Communication Association, 41(2), 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2017.1304163

- Delbosc, A., Naznin, F., Haslam, N., & Haworth, N. (2019). Dehumanization of cyclists predicts self-reported aggressive behaviour toward them: A pilot study. Transportation Research. Part F, Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 62, 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2019.03.005

- Eden, A., Daalmans, S., & Johnson, B. K. (2017). Morality predicts enjoyment but not appreciation of morally ambiguous characters. Media Psychology, 20(3), 349–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2016.1182030

- Eden, A., Grizzard, M., & Lewis, R. J. (2011). Disposition development in drama: The role of moral, immoral and ambiguously moral characters. International Journal of Arts and Technology, 4(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJART.2011.037768

- Eden, A., Oliver, M. B., Tamborini, R., Limperos, A., & Woolley, J. (2015). Perceptions of moral violations and personality traits among heroes and villains. Mass Communication and Society, 18(2), 186–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2014.923462

- Fiske, S. T. (2013). Varieties of (de) humanization: Divided by competition and status. In S. Gervais (Ed.), Objectification and (De)Humanization, Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 60 (pp. 53–71). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6959-9_3

- Fiske, S. T., & Neuberg, S. L. (1990). A continuum of impression formation, from category based to individuating processes: Influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 23, 1–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60317-2

- Forster, E. M. (1956). Aspects of the Novel. Mariner Books.

- Francemone, C. J., Grizzard, M., Fitzgerald, K., Huang, J., & Ahn, C. (2021). Character gender and disposition formation in narratives: The role of competing schema. Media Psychology, 24(3), 413–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2021.2006718

- Frazer, R., Moyer-Gusé, E., & Grizzard, M. (2022). Moral disengagement cues and consequences for victims in entertainment narratives: An experimental investigation. Media Psychology, 25(4), 619–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2022.2034020

- Gray, K., Jenkins, A. C., Heberlein, A. S., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Distortions of mind perception in psychopathology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(2), 477–479. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1015493108

- Grizzard, M., Fitzgerald, K., Francemone, C. J., Ahn, C., Huang, J., Walton, J., McAllister, C., & Eden, A. (2020). Validating the extended character morality questionnaire. Media Psychology, 23(1), 107–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1572523

- Grizzard, M., Francemone, C. J., Fitzgerald, K., Huang, J., & Ahn, C. (2020). Interdependence of narrative characters: Implications for media theories. Journal of Communication, 70(2), 274–301. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa005

- Grizzard, M., Huang, J., Fitzgerald, K., Ahn, C., & Chu, H. (2018). Sensing heroes and villains: Character-schema and the disposition formation process. Communication Research, 45(4), 479–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217699934

- Grizzard, M., Matthews, N. L., Francemone, C. J., & Fitzgerald, K. (2021). Do audiences judge the morality of characters relativistically? How interdependence affects perceptions of characters’ temporal moral descent. Human Communication Research, 47(4), 338–363. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqab011

- Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2007). The moral mind: How 5 sets of innate intuitions guide the development of many culture-specific virtues, and perhaps even modules. In P. Carruthers, S. Laurence, & S. Stich (Eds.), The Innate Mind (Vol. 3, pp. 367–391). Oxford.

- Hall, A. (2003). Reading realism: Audiences’ evaluations of the reality of media texts. Journal of Communication, 53(4), 624–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2003.tb02914.x

- Hartmann, T., Toz, E., & Brandon, M. (2010). Just a game? Unjustified virtual violence produces guilt in empathetic players. Media Psychology, 13(4), 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2010.524912

- Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

- Krakowiak, K. M., & Tsay-Vogel, M. (2013). What makes characters’ bad behaviors acceptable? The effects of character motivation and outcome on perceptions, character liking, and moral disengagement. Mass Communication and Society, 16(2), 179–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2012.690926

- Kužmičová, A., & Bálint, K. (2019). Personal relevance in story reading: A research review. Poetics Today, 40(3), 429–451. https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-7558066

- Matthews, N. L. (2019). Detecting the boundaries of disposition bias on moral judgments of media characters’ behaviors using social judgment theory. Journal of Communication, 69(4), 418–441. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz021

- McCroskey, J. C., Richmond, V. P., & Daly, J. A. (1975). The development of a measure of perceived homophily in interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research, 1(4), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1975.tb00281.x

- Moyer-Gusé, E. (2008). Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory, 18(3), 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x

- Oliver, M. B., Bilandzic, H., Cohen, J., Ferchaud, A., Shade, D. D., Bailey, E. J., & Yang, C. (2019). A penchant for the immoral: Implications of parasocial interaction, perceived complicity, and identification on liking of anti-heroes. Human Communication Research, 45(2), 169–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqy019

- Prati, F., Crisp, R. J., Meleady, R., & Rubini, M. (2016). Humanizing outgroups through multiple categorization: The roles of individuation and threat. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(4), 526–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216636624

- Prati, F., Crisp, R. J., & Rubini, M. (2015). Counter-stereotypes reduce emotional intergroup bias by eliciting Surprise in the face of unexpected category combinations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 61, 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.06.004

- Raney, A. A. (2004). Expanding disposition theory: Reconsidering character liking, moral evaluations, and enjoyment. Communication Theory, 14(4), 348–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00319.x

- Raney, A. (2020). Affective disposition theory and disposition theory. In J. Van den Bulck (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of media psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119011071.iemp0207

- Reissenweber, B. (2003). Character: Casting shadows. In A. Steele (Ed.), Writing Fiction (pp. 25–51). Bloomsbury.

- Sanders, M. S. (2010). Making a good (bad) impression: Examining the cognitive processes of disposition theory to form a synthesized model of media character impression formation. Communication Theory, 20(2), 147–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01358.x

- Sanders, M. S., & Ramasubramanian, S. (2012). An examination of African Americans’ stereotyped perceptions of fictional media characters. Howard Journal of Communications, 23(1), 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2012.641869

- Shafer, D. M., & Raney, A. A. (2012). Exploring how we enjoy antihero narratives. Journal of Communication, 62(6), 1028–1046. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01682.x

- Slater, M. D., & Gleason, L. S. (2012). Contributing to theory and knowledge in quantitative communication science. Communication Methods and Measures, 6(4), 215–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2012.732626

- Slater, M. D., & Rouner, D. (2002). Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Communication Theory, 12(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.0000/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00265.x

- Snyder, B. (2005). Save the Cat. Michael Wiese Productions.

- Tamborini, R., Grall, C., Prabhu, S., Hofer, M., Novotny, E., Hahn, L., Klebig, B., Kryston, K., Baldwin, J., Aley, M., & Sethi, N. (2018). Using attribution theory to explain the affective dispositions of tireless moral monitors toward narrative characters. Journal of Communication, 68(5), 842–871. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy049

- Tamborini, R., Grizzard, M., Hahn, L., Kryston, K., & Ulusoy, E. (2021). The role of narrative cues in shaping ADT: What makes audiences think that good things happened to good people? In P. Vorderer, & C. Klimmt (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of entertainment theory (pp. 321–342). Oxford University Press.

- Weber, R., & Popova, L. (2012). Testing equivalence in communication research: Theory and application. Communication Methods and Measures, 6(3), 190–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2012.703834

- Zajonc, R. B. (2001). Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(6), 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00154

- Zillmann, D. (2000). Basal morality in drama appreciation. In I. Bondebjerg (Ed.), Moving images, culture and the mind (pp. 53–63). University of Luton Press.

- Zillmann, D., & Cantor, J. (1976). A disposition theory of humor and mirth. In T. Chapman, & H. Foot (Eds.), Humor and laughter: Theory, research, and application (pp. 93–115). John Wiley.