ABSTRACT

Job applicants’ social media postings and presence can impact employers’ perceptions during the hiring process. The current study expands this line of inquiry, exploring the effects of both message characteristics (i.e. post temporality) and individual characteristics (i.e. hiring manager’s view about individuals’ ability to change over time). Results of a 2 (problematic content: present v. absent) × 3 (post temporality: recent v. 2 years ago v. 5 years ago) experiment (N = 220) revealed the negative main effect of the presence of problematic social media content was moderated by the temporality of the post: More recent posts more substantively impacted perceptions of person-job fit. This moderation effect was further moderated by the manager’s incrementalism: the belief people’s personalities can change over time. Similar patterns of effects were not identified for broader perceptions of the applicant’s general employability.

Introduction

Coutu (Citation2007) offers up a hypothetical – but plausible – example of an applicant, Mimi, applying to manage a multinational company’s newest expansion into Shanghai, China. Following review of Mimi’s resume and successful interview, the otherwise-stellar candidate’s prospects for being hired are derailed when a routine Google search reveals Mimi had been involved in anti-globalization protests against the WTO (including in front of the Chinese consulate) years before. The company subsequently debates whether Mimi’s potential value to the organization is offset by the potential trouble should others – particularly Chinese business partners – become aware of her conduct a decade prior.

As our online histories expand, others are increasingly able to use archived online content to form impressions of our contemporary selves. New acquaintances can look back at decades of social media content to look for proverbial “red flags,” consumers can find older reviews prior to purchase, and – as evidenced in the case of Mimi – employers can consider past statements and actions to supplement information revealed via resumes and interviews. Even long-past online behaviors increasingly can be used to guide impressions of targets’ contemporary selves.

The present research therefore explored the effects of online traces of prior behaviors on perceptions of the target’s current self. To do so, we considered both message and internal sources of effects. First, message effects stemming from media artifacts generated by the target are considered, specifically the content of a social media post as well as the time since that post was made (thus reflecting current or prior self). Second, we assessed an internal, psychological factor of the perceiver that may moderate these message effects: the perceiver’s implicit personality theory. Implicit personality theories offer a continuum of how individuals understand human traits and behaviors, ranging from viewing personal characteristics as fixed and immutable (i.e., entity theorists) to characteristic as capable of change over time (i.e., incremental theorists). Findings of an experiment conducted with N = 220 hiring personnel reveal both message and dispositional factors influenced perceptions of person-job fit, but not the more general perception of the applicant’s employability. Decomposition of the three-way interaction reveals unexpected processes for those participants who strongly aligned with incremental theory.

Review of literature

Warranting

Warranting theory addresses how individuals connect online claims to an offline or physical self (Walther & Parks, Citation2002). Within warranting theory, a warrant refers to a, “cue that authenticates an online self-presentation” (DeAndrea, Citation2014, p. 187), and increases perceivers’ confidence the online claim faithfully reflects the target’s offline characteristics. Warrants can take several forms, including both self- and other-generated claims (Parks, Citation2011); but ultimately affect perceivers’ impressions of the individual’s offline self and influence subsequent behaviors.Footnote1 For example, warranting theory has been leveraged to explain how individuals form impressions of a target’s offline extraversion due to both their own claims and the statements of others (Walther et al., Citation2009), whether applicants pursue jobs with employers based on a third party’s online review (Carr, Citation2019), and even an applicant’s perceived employability (Scott et al., Citation2014).

Germane to the present study, warranting theory addresses how warrants guide impressions of the offline self, regardless of the valence of that online information. Though recent work has advanced warranting theory by considering the effects of third-party and system-generated information (e.g., Antheunis & Schouten, Citation2011; DeAndrea, Van Der Heide, et al., Citation2018) and whether an online claim has been manipulated or influenced by the target (e.g., DeAndrea, Tong, et al., Citation2018; Lane et al., Citation2023), less consideration has been given to attributes of self-claims, which are a critical component of warranting, particularly in social media where individuals make numerous self-statements that are accessible to others (Parks, Citation2011). The present work extends warranting theory by considering the yet-unexplored temporal component of warranting theory, taking into account how more recent or distant online self-claims may disparately affect others’ perceptions of an individual’s current offline self.

Warranting job applicant’s identities

One context apropos for exploring the perceived veracity and offline connection to self-statements is that of job seekers. Motivated to strategically self-present information themselves via requested information (e.g., resumes, cover letters) to maximize their chances of advancing in the hiring process, applicants provide self-claims to potential employers they perceive will indicate they possess the employer’s desired characteristics. Increasingly, employers are supplementing this requested information with searches of online information (e.g., social media, blogs, database information) to learn about applicants beyond the highly-curated self-presentation occurring in applications and interviews (Carr, Citation2016; Feintzeig & Fuhrmans, Citation2018). Employers increasingly integrate social media screening into their hiring processes: Over 70% of employers now report doing so for at least some job candidates (Career Builder, Citation2018). However, amid the myriad of information and sources online, online claims may not accurately connect to or reflect the target offline (Carr, Citation2016; DeAndrea, Citation2014).

Both positively- and negatively-valenced social media content by an applicant can affect employers’ perceptions of an applicant, consistent with the valence of the content (Carr & Walther, Citation2014). Though both types of post valences affect employers’ perceptions, much research into the effect of online information on employers’ perceptions has focused on negative information or disclosures (Roth et al., Citation2016). This focus on negatively-valenced online information may be due to the negativity effect (Baumeister et al., Citation2001; Peeters & Czapinski, Citation1990), whereby individuals experience a greater impact on perceptions of others when exposed to negative (rather than positive) stimuli, and thus effects of negative information are easier to detect. Indeed, employers report increasingly looking at online social media content as a screening tool, both to verify claims made offline (Berkelaar, Citation2017) and – focal to the present work – to learn about applicants through their less-selective social media behaviors and disclosures (Roulin & Bangerter, Citation2013).

Problematic social media content and applicant perceptions

Employers may look to private online behaviors as indicators of how applicants will behave as offline once hired and no longer strategically self-presenting favorable attributes to obtain employment (Karl et al., Citation2010). Employers’ impressions of applicants may thus be negatively impacted by problematic social media content: “information posted by potential applicants (e.g., students) on [social network sites] (e.g., Facebook) that may hurt their chances to get a job” (Roulin, Citation2014, p. 80). Important to this conceptualization is that problematic social media content is determined within the context of employment. As social media collapse disparate social contexts and networks (Davis & Jurgenson, Citation2014), individuals may post content that, though appropriate or normative in one social contexts (e.g., among friends), is considered problematic or unprofessional by employers and thus serve as an informative warrant.

Substantive work in the personnel literature has identified the types of social media content employers perceive to be problematic (often dubbed social media faux pas; Karl et al., Citation2010; Roulin & Bangerter, Citation2013; Roulin, Citation2014), and whose presence negatively impacts employers’ perceptions. Surveying recruiters and their perceptions of various social media content and behaviors, Hartwell and Campion (Citation2020) comprehensively identified problematic social media content, noting that (among others) negative comments about race, gender, or religion, disparaging a current/former employer, information contradicting qualifications, posting photos or comments of a sexual nature or related to alcohol consumption, and profanity led to significant negative influences on recruiters’ perceptions of applicants.

The presence of problematic social media content affects both broad and specific perceptions employers form of applicants. Though many perceptual outcomes have been studied, two of the most common perceptions considered in the extant research are general employability, or whether or not an applicant would be able to secure a job broadly (even if not with this particular employer; Rynes & Gerhart, Citation1990), and person-job (PJ) fit, the congruence between an applicant’s knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) and the KSAs perceived as needed to do the required job (Edwards, Citation1991). Perceptions of both employability and PJ fit are critical to employers’ ultimate decisions whether to advance the applicant in the hiring process, either by offering an interview or extending a job offer (Adkins et al., Citation1994; Carr et al., Citation2017).

To date, research has examined the impact of several types of problematic social media posts on employer perceptions. Bohnert and Ross (Citation2010) found applicants were perceived less employable (i.e., perceived less qualified for the job, less likely to be hired hire, and offered a lower starting salary) when applicants’ social media profile pictures were focused on drinking and partying rather than either family- or professionally-oriented. This finding was recently bolstered by Tews et al. (Citation2020), who found social media content depicting drug and alcohol use had a negative impact on perceptions recruiters’ overall evaluation of the candidate. Similarly, Carr and Walther (Citation2014) found HR professionals viewed applicants as less employable and possessing less PJ fit when resumes and cover letters were accompanied by social media posts in which applicants made negative self-disclosures about their job performance. Finally, Kwok and Muñiz (Citation2021) interviews with HR managers revealed managers disfavored applicants after finding posts with inappropriate language or content, negative posts, discrimination, or alcohol/drug use. These findings indicate problematic social media content impact employers’ perceptions of applicants: both general employability and specific perceptions, like PJ fit.

Thus, as an initial baseline against which to contrast additional effects, we offer an initial hypothesis extending prior research (e.g., Bohnert & Ross, Citation2010; Tews et al., Citation2020) focusing on the detrimental effect of applicants’ problematic social media content on hiring decisions, particularly perceptions of the applicant’s (a) employment suitability and (b) ability to execute required job tasks. To further contribute to the literature about the effect of social media disclosures on applicant perceptions (beyond focusing on self-presentations of drinking) and to maximize potential attributional effects, we considered two yet-untested problematic social media content identified by Hartwell and Campion (Citation2020) as antecedents to employers’ perceptions of the applicant offline: Use of profanity and disparaging a specific former employer.

H1:

Applicants’ problematic social media content (i.e., obscenity, negative statements about specific prior employer) negatively impact perceptions of (a) employability and (b) person-job fit.

This initial hypothesis merely applies the fundamental tenant of warranting theory: online information guides employers’ perceptions of job applicants offline. And though scholarship has begun to probe various mechanism underlying warranting theory – including the effect of information source on a claim’s impression formation value (Carr & Stefaniak, Citation2012; Walther et al., Citation2009) and the malleability and dissemination control of online claims (DeAndrea, Tong, et al., Citation2018), one underexplored mechanism in warranting theory – and impression formation in general – is the role of temporality (Carter & Sanna, Citation2008; Hollenbaugh, Citation2021; Ramirez & Walther, Citation2009). Online information about an individual can often transcend time, particularly online, making the past available in the present and the present available into the future.

Temporal effects of problematic social media content

Because most social media provide high levels of message persistence, they serve as “archival repositories of past performances and memories,” (p. 3), which can empower users to review and interact with an individual’s historical content (Humphreys, Citation2018). As such, social media enable time collapse: “a blurring of time and a muddling of past and present experiences” (Brandtzaeg & Lüders, Citation2018, p. 2). Just as social media allow identities to bleed outside their intended boundaries into different intermingling networks (Davis & Jurgenson, Citation2014; Hogan, Citation2010), they also desynchronize self-presentation, allowing perceivers to access both current and past expressions of a target’s self. Because of time collapse, users may seek to delete contributions or hide their identities (see DeAndrea, Tong, et al., Citation2018) or “untag” (i.e., disassociate) themselves from regrettable photos or comments (see Dhir et al., Citation2016), reducing traces of past selves or presentations online that may conflict with future self-presentations or presentational goals.

Whereas recent statements are presumed to be diagnostic or informative of the target’s current self (Hollenbaugh, Citation2021), it remains unclear whether a temporally-distant self-presentation online informs perceptions of that target offline as they are now. Two competing potentials are suggested by contemporary literature: that more temporally distant presentations are stronger indicators of a person’s current self, or that more temporally distant presentations are weaker indicators of a person’s current self. We briefly articulate these two disparate positions and derive competing hypotheses.

Older content may better-inform perceptions of the current self

One perspective in the literature would suggest past representations of the self may be highly informative of the individual’s offline self. Self-generated social media content (e.g., profiles) are often genuine reflections of posters’ actual personalities rather than self-idealization (Back et al., Citation2010), and thus can inform strong perceptions on behalf of perceivers. Moreover, Ramirez et al. (Citation2002) proffered that as online statements made in social settings can persist and be viewed beyond their initial context and intended audience, online postings may, “offer particularly valuable insights to information seekers” (p. 220) such as employers. As users increasingly exercise control over the contents of their online presence (DeAndrea, Citation2014), older social media content may be less curated or strategically presented with an employer as a potential audience. From this information seeking perspective, older information may be less likely to be curated toward an employer (e.g., selectively presenting one’s best “work self”) than current information, and thus be more reflective of their typical offline selves. Consequently, knowing about who an individual was may actually be more informative or diagnostic of who they are now, as temporally distant posts are less-likely to be reflections of a goal-oriented self-presentation. This leads to the first of two competing hypotheses about the effects of online information temporality, predicting older posts are stronger warrants:

H2:

Applicants’ temporally distant problematic social media content (i.e., obscenity, negative statements about prior employer) have a stronger effect than more recent problematic social media content on employers’ perceptions of applicants’ (a) employability and (b) person-job fit.

Newer content may better-inform perceptions of the current self

A second perspective in the literature suggests past representations of the self are weak indicators of the current self. Such a perspective is an amalgam of both communicative and psychological literature, converging on the supposition that more recent disclosures, both online and in general, are more diagnostic of an individual’s current self-concept and self.

Individuals are increasingly aware their online self-presentations can be accessed by broad, often unintended audiences (Hogan, Citation2010). As a result, individuals are often mindful of the potential audiences of their self-presentations, utilizing privacy settings and selective disclosures to help manage their identities online (Vitak, Citation2012), particularly when such identity cues may be persistent. Recently, interviews by Birnholtz and Macapagal (Citation2021) revealed users aware of the persistence of social media posts will be cautious about posts as they are made, particularly when disclosures may be stigmatizing or unknown to parts of their audience, a finding echoed by Huang et al. (Citation2020) finding that individuals utilize WeChat’s “Time Limit” permanence settings to increase the permanence of messages users think may better reflect them in the long term while limiting the message permeance of potentially unflattering messages or content that may not be consistent with an intended future self. Ultimately, users appear to be mindful about online disclosures in the present that may not reflect their intended self to future audiences, suggesting individuals’ more-recent self-presentations may be more reflective of their own current self-perceptions than temporally distant self-presentations.

An additional and more direct consideration may be the changes of personality traits over time. Individuals are not innately static, and individuals’ self-concepts and personalities can change over the course of their lives (Demo, Citation1992; Jones & Meredith, Citation1996). Of interest to the present study, though individuals traits tend to stabilize in later life stages (Costa et al., Citation2019), self-concepts and personalities are particularly mutable during adolescence and early adulthood (i.e., while in secondary and tertiary schools) as individuals gain agency and identify and nurture their autonomous selves (Pascarella et al., Citation1987; Shapka & Keating, Citation2005). In other words, who someone is now is not innately who they will be in several years, especially as individuals go through the independence and self-exploration of college. In this way, the developmental psychology literature suggests self-presentational statements may be decreasingly diagnostic as they are more temporally distant from the current self, reflecting a prior (rather than current) self of the target individual.

Both self-presentational and psychological explanations articulate different paths to the same outcome: Individuals’ temporally distant self-presentations may be less reflective of their current selves than current self-presentations. From this perspective, knowing about who an individual was may not be as informative or diagnostic of who they are now, as temporally distant posts are less-likely to faithfully warrant the individual’s current self. This leads to the second of two hypotheses about the effects of online information temporality, predicting recent posts are stronger warrants:

H3:

Applicants’ recent problematic social media content (i.e., obscenity, negative statements about a specific prior employer) have a stronger effect than more temporally distant problematic social media content on employers’ perceptions of applicants’ (a) employability and (b) person-job fit.

Moderated moderation effect of entity theory

In addition to the extrinsic message effects of social media contents, employers’ dispositional factors are likely also influenced by intrinsic personality characteristics of the hiring managers themselves. One critical psychological factor that may influence how each employer perceives applicant information – particularly that obtained from across time – is the individual’s perception of whether or not people can fundamentally change. Entity theory provides a lens through which to examine people’s beliefs regarding human attributes, such as moral character (Dweck et al., Citation1995). Entity theory proffers people are static and unlikely to change. Individuals holding an entity theory of personality (i.e., entitists) are likely to view past behaviors as a stronger predictor of future conduct, as behaviors and responses should be generally stable over time. Alternately, individuals believing people are malleable and capable of change over time (i.e., incrementalists) are likely to view past behaviors as weaker predictor of future conduct, as behaviors and responses can change over time. These competing perspectives model disparate implicit mind-sets individuals – including managers – can possess about others’ abilities to change over time (Heslin et al., Citation2006), and may moderate effects of a manager’s dispositional forgiveness.

Implicit assumptions about character and behavior are likely to be present in recruiters considering job applicants, particularly as they consider candidates’ past behaviors and activity on social media platforms. An entitist recruiter would view applicants’ selves as stable over time. Consequently, negative behaviors would provide similar impression-formation value whether those behaviors were temporally recent or distant, making evaluative judgments based on a problematic social media content as representative of a fixed self. Alternately, an incrementalist recruiter would view applicants’ selves as mutable over time. As an incrementalist recruiter would believe individuals are capable of change across the lifespan, past behaviors would not be considered strong predictors of current conduct, particularly as the temporal distance between the past behavior and present increases. Consequently, as recruiters are more aligned with incremental theory’s supposition that individuals’ traits and personas are not fixed, they may perceive more recent information as more diagnostic of the individual’s current self (Dweck et al., Citation1995). A recruiter’s implicit assumptions about character can thereby further moderate the temporal effects of problematic social media content. Therefore:

H4:

The moderating effect of a post’s recency (i.e., temporality) on the direct effect of problematic social media content on an employer’s perceptions of an applicant is further moderated by the employer’s degree of incremental theory, so that incrementalist employers experience stronger perceptions from more recent posts.

Method

Participants

Given the moderate effect sizes expected, an a priori power analysis using G*Power (v. 3.1.9.4; Faul et al., Citation2008) suggested 215 participants would be needed to detect significant medium (fFootnote2 = .10) effects with power = .95. Participants were recruited via an online recruitment tool (Prolific.co), and compensated USD$1.50 for taking part in the ~10-minute study. To be eligible to participate, individuals must have been at least 18 years of age, currently working at least 30 hours/week in a human resources or personnel job in the United States, and have at least six months of human resources or personnel experience.

Human resources employees (N = 220) were recruited via Prolific.co and compensated US$1.50 for their participation. Participants’ average age was 34.61 (SD = 7.14), and self-identified their genders as male (nmale = 155), female, (nfemale = 63), and two did not identify a gender. Participants were drawn from 24 industries, with construction (17.3%), finance and insurance (16.8%), and health care and social assistance (8.2%) and college, university, and adult education (8.2%) the most represented.

Procedure

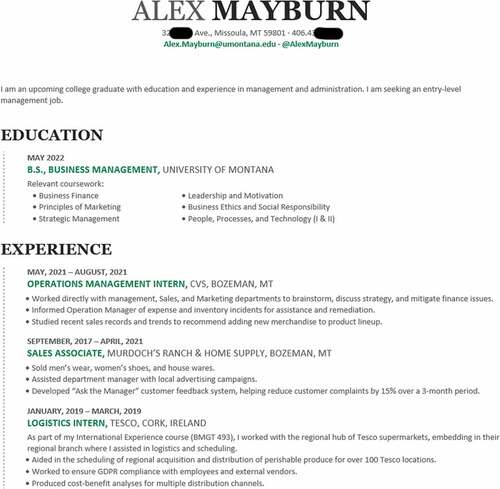

Participants were recruited to take part in an online study assessing the workplace readiness and viability of a candidate based on requested and obtained information. After providing informed consent and completing initial screener questions, participants were asked to assume the role of a hiring manager considering an applicant for an entry-level management job. After being presented a brief job description drawn from an actual online job posting (Appendix A), participants were then shown a resume of the applicant Alex Mayburn (Appendix B). Next, participants were shown a social media post a human resources intern had purportedly found on the applicant’s Twitter account and deemed notable (see “Stimuli” below). Following successful completion of the attention checks, participants then completed a series of standardized measures to assess their perceptions and attributions of the applicant.

Stimuli

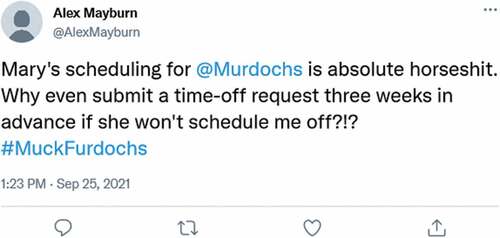

Participants were exposed to identical job posting and resume information. All that varied among conditions was the social media post to which they were exposed. These stimuli took the form of Twitter posts (created using a tweet generator, Tweetgen.com), identifying “Alex Mayburn” as the poster, connected to the resume by both name and identified Twitter user handle. “Alex Mayburn” was selected as an androgynous name, and the default Twitter profile silhouette (see ) was used in place of a profile image, helping reduce potential effects of attributions based on gender or other physical attributes. The nature of the hypotheses required a fully-crossed 2 (problematic social media content: present v. absent) × 3 (post recency: recent, moderately distant, far distant) design, resulting in six total experimental conditions. Participants were randomly assigned to one of these six conditions.

Experimental conditions

Problematic social media content

To manipulate the presence (versus absence) of problematic social media content, the contents of the applicant’s social media post was altered to omit or include problematic content. Much research to-date has operationalized problematic social media content as alcohol/drug content (e.g., Bohnert & Ross, Citation2010; Tews et al., Citation2020). However, content involving alcohol in the present study introduced potentially-confounding effects stemming from post temporality: A current post by a 22-year old about alcohol use may be problematic, but not as much as a similar post from 5 years ago in which the then−17-year old’s depiction of alcohol use would also be an illegal activity. Thus, we drew from Hartwell and Campion (Citation2020) to identify two other types of social media content employers report as negative and result in negative perceptions similar to alcohol/drug use: disparaging current/former employer and profanity. Stimuli posts were constructed to either include or exclude condemnation of a specific current or prior employer2 while concurrently using profane language.

To control for potential message effects (Reeves et al., Citation2016), two distinct messages were constructedFootnote3 and used. In the problematic social media content conditions, posts read: “How is it any time my dumbass company needs to do ‘more with less’ that ends up increasing my job (without more $$$), while my boss sits on her fat ass doing the same amount of work,” and “Mary’s scheduling for #Murdochs is absolute horseshit. Why even submit a time-off request three weeks in advance if she won’t schedule me off?!? #MuckFurdochs”. In the no problematic social media content conditions, two equitable messages were presented, but omitting the disparagement of a specific prior employer or profanity: “How is it any time a company needs to do ‘more with less’ that ends up increasing employees’ job (without more $$$), while their bosses do the same amount of work,” and “Scheduling for a lot of employers can be terrible. Why even submit a time-off request three weeks in advance if you won’t get that time scheduled off?!? #DoBetterBosses”. In this way, the posts in the no problematic social media content condition (i) begrudged employers in general without identifying their specific current or former employer and (ii) were negative without being profane, thereby the negative valence and intent of the post while stripping away the particular problematic content being studied.

Post recency

Additionally, this research was interested in the effects of the recency of applicants’ social posts on employer’s perceptions of the applicant. The recency of the post was manipulated by altering the date the post was made. As attending college – especially the first two years – can be a time of substantive personal growth and change among young adults (Terenzini & Wright, Citation1987), it was important to consider how a post may reflect an applicant about to graduate, an applicant in the middle of their college experience, and then the applicant prior to college. Thus, post recency was manipulated by altering the date stamp of the applicant’s tweet to be either recent (i.e., from the prior week), moderately distant (i.e., from two years prior, about the middle of the applicant’s college experience), and far distant (i.e., from five years ago, likely prior to the applicant’s college experience).

Measures

Following their exposure to study stimuli, participants completed several established measures using 7-point Likert-type scales. At the end of the instrument, participants also self-identified demographic information, including their age, ethnicity, and sex.

Independent variable

Incremental theory

Participants completed six items (α = .79) from Levy et al. (Citation1998) to assess their implicit theories of personality. Participants responded to items including, “Everyone is a certain kind of person, and there is not much that they can do to really change that,” and, “People can substantially change the kind of person they are.” Items were recoded as appropriate so that higher-values indicated greater incrementalism.

Dependent variables

Employability

The participant’s overall employability—or perception the applicant is capable of obtaining employment in general – was assessed using two items (α = .71) from Adkins et al. (Citation1994): “Given your overall impression of this candidate, Alex Mayburn is employable (i.e., likely to receive other job offers),” and “Regardless of the candidate’s qualifications, Alex Mayburn is likeable.”

Person-job fit

Person-job (PJ) fit was measured using Cable and Judge’s (Citation1996) three item scale, α = .83. Participants responded to items including, “The applicant’s abilities and education provide a good match with the demands this job would place on them.”

Results

Hypotheses were tested using Hayes (Citation2013; v. 3.3) regression-based PROCESS macro (model 3), testing for a three-way moderated moderation interaction. Two models entered the presence of problematic social media content (dummy-coded as 1) as the independent variable, the post recency as the moderating variable (coded so that 1 = recent, 2 = moderately distant, and 3 = far distant), and a participant’s incrementalism as the moderating moderation variable. The first model tested hypotheses about person-job fit (a); and the second model tested hypotheses about perceived employability (b). Results appear below and in .

Table 1. Moderated moderation analysis for variables predicting perceived employability and person-job Fit.

For the dependent variable of employability, the moderated moderation model was statistically significant, F(7, 211) = 2.80, p = .008, R = .29, R2 = .09. However, there was not a significant main effect of the presence of problematic social media content on perceived employability, b = −1.29, se = 1.66, p = .44. Thus, H1a was not supported. The interaction between post temporality and the presence of problematic social media content was also nonsignificant, b = .37, se = .81, p = .64. Finally, the three-way interaction between incremental theory, post temporality, and the presence of problematic social media content was nonsignificant, b = −.04, se = .18, p = .83. Ultimately, though the omnibus model was significant, none of the predicted relationships were statistically significant (see ); and hypotheses regarding effects on perceived employability (H2a, H3a, and H4a) were rejected.

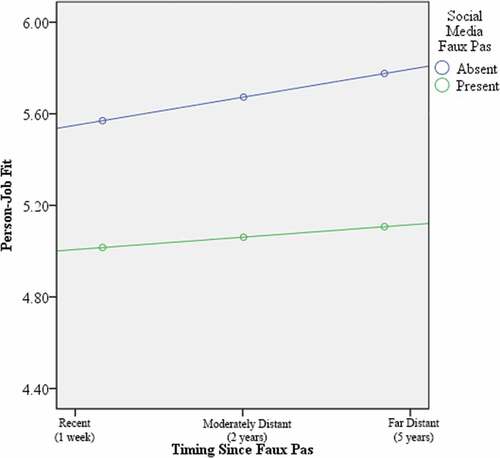

For the dependent variable of person-job fit, the moderated moderation model was statistically significant, F(7, 211) = 4.06, p < .001, R = .34, R2 = .12, indicating the combined effect of both moderators significantly influence the effect of problematic social media content on perceptions of PJ-fit. Only the presence of problematic social media content had a significant main effect on perceived PJ fit (see ), b = −4.10, se = 1.55, p = .009, supporting H1b. The interaction between post temporality and the presence of problematic social media content was also significant, b = 1.86, se = .75, p = .014, supporting H3b (and suggesting rejection of H2b): Post temporality moderated the relationship between the presence of problematic social media content and perceived PJ fit, so that the negative influence of problematic social media content was generally stronger as the post was more recent (see ). Finally, the three-way interaction between incremental theory, post temporality, and the presence of a problematic social media content was significant, b = −.44, se = .17, p = .009, supporting the moderated moderation proposed by H4b. In other words, the magnitude of the moderation by time since the posting of the problematic content on the effect of the presence of that problematic social media content on perceptions of PJ fit depends on the perceiver’s incrementalism, explaining about 3% of the variance in perceived PJ fit.

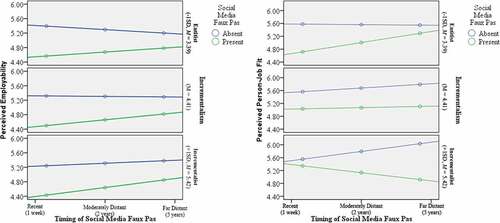

Additional analyses decomposed the moderated moderation effect identified for the outcome of PJ fit. Conditional interaction of time since post and the presence of problematic social media content at different levels of entity theory are presented in . The moderated moderation appears to have been driven by individuals adhering more to incrementalism (i.e., +1SD, M > 5.42; n = 35, m = 6.05, sd = .51), effect = −.54, F(1, 211) = 4.86, p = .03, whose patterns of effects differed from individuals adhering more to entitivism (i.e., −1SD, M < 3.39; n = 29, m = 2.80, sd = .45) and those not strongly falling into either theory (i.e., around the middle of the continuum; n = 90; see ). Incrementalists viewed applicants as demonstrating better PJ fit when exposed to a social media post lacking problematic social media content as the post was made longer ago. However, incrementalists experienced a reverse pattern of effects when exposed to problematic social media content, perceiving the applicant to demonstrate greater PJ fit as the problematic social media content was posted more recently. Uniquely, incrementalists’ perceptions of the applicant’s PJ fit converged as the post was made more recently, regardless of the presence of problematic social media content.

Figure 3. Simple Moderation Effect of Temporality of Social Media Faux Pas on Employers’ Perceptions of Applicant’s Person-Job Fit.

Table 2. Tests of Presence of Problematic Social Media Content × Time Since Post Interaction at Levels of Incrementalism.

Discussion

This research explored how employers’ perceptions of job applicants are affected by applicants’ media artifacts and employers’ own dispositions. Specifically, it considered applicants’ prior social media posts made either recently or long ago, as well as employers’ own implicit theories about people’s ability to change over time. Hypothesized processes were supported for perceptions of the applicant’s person-job (PJ) fit, but not for more general employability. Problematic social media content (operationalized as the presence of profanity and disparagement of one’s specific employer) had a significant negative impact on perceptions of PJ fit; and those effects were stronger when the problematic content was made more recently. An employer’s belief whether people are able to change their general attributes over time further moderated this effect, but in an unexpected way.

Effect of problematic social media content on employers’ perceptions of applicants

The support for the negative impact of problematic social media content on employers’ perceptions of a job applicant’s PJ fit was clear. The most substantive effect identified in this research was whether participants were exposed to the applicant’s problematic social media content. Even when not tied directly to job-relevant KSAs, problematic social media content exerted a strong main effect that diminished employers’ perceptions of the applicant’s person-job fit, consistent with prior findings on the effects of social media information on perceptions of applicants (Bohnert & Ross, Citation2010; Roulin & Bangerter, Citation2013). As employers at the early stages of hiring are often looking to quickly disqualify candidates before more carefully considering a smaller pool of qualified candidates to interview or hire (Posthuma et al., Citation2002), the strong effect of negative online information on perceptions of PJ fit is likely reflective of employers’ screening procedures.

However, the lack of similar support for perceptions of an applicant’s general employability suggest these effects may not be as foregone as assumed. Two potential possibilities may account for this disparate finding. First, there may be some conceptual conflation between employability and job fit. Though often treated as a unique and distinct concept (e.g., Bohnert & Ross, Citation2010; Carr et al., Citation2017), PJ fit has also been theorized as one of many dimensions of the superordinate construct “employability,” alongside other forms of fit, including person-organization (PO), person-vocation (PV), and person-group (PG) fit (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, Citation2006). The present findings may evidence recruiters view past problematic social media content as diagnostic or informative of some forms of job fit (i.e., subdimensions of employability) but not others. For example, denigrating a prior employer may speak to an applicant’s ability to perform job tasks by suggesting they are frustrated or problematic employees; but not their fit with a broader industry or other employers (i.e., PV fit). Alternately, frustration with a particular employer – when focused on actual business practices rather than ad hominem attacks – may be viewed by recruiters as a competent worker (i.e., high PJ fit) who is not valued by the employer or currently well-suited to that particular organization (i.e., low PO fit). In both instances, were employability considered as a superordinate construct to various dimensions of fit, variation in a single fit dimension may not be reflected in other dimensions of fit or the superordinate perception of employability.

A second potential explanation relates to the measurement of outcomes. The disparate effects of problematic social media content on employability and PJ fit may merely be an artifact of how items were operationalized, particularly given the timing of this research. Employability referred to participants’ general sense the applicant could get any employment, whereas person-job fit referred to the applicant’s fit to the specific job posting to which they were exposed. It could be that participants seeing problematic social media content found this post problematic or disqualifying for the particular managerial job to which the applicant was applying (consistent with Kwok & Muñiz, Citation2021), but not the candidate’s general ability to find any form of employment – an explanation compounded by the timing of the study. During data collection, the United States was experiencing drastic labor shortages amid the “Great Resignation,” wherein employers across industries clamored for employees (The Economist, Citation2021). It is possible this manifested as a history effect, whereby recruiters taking part in the study thought the applicant may be less of a fit for the particular job shown in light of problematic social media content, but were confident that a job seeker could find some job amid nationwide desperation among employers. Future work, including with different measurement of study variables and accounting for broader trends in the job market, may help resolve these potential explanations.

Implications for warranting theory

Another contribution of this research is its response to prior calls to consider the role of temporality in impression formation from online information (Hollenbaugh, Citation2021), providing an initial look at the warranting value of online claims across time. Warranting theory has not yet accounted for the ability of online tools to collapse time, enabling online presentations to persist – and be accessed – across time (Brandtzaeg & Lüders, Citation2018). These findings advance warranting theory by evidencing the role of temporality in warranting value. This research provides initial evidence a warrant’s ability to guide impressions of an offline target may decrease as the time since that claim was made increases. Data clearly evidenced the moderating effect of post temporality, as more-recent posts resulted in reduced perceptions of PJ fit when employers were exposed to applicant’s problematic social media content, relative to identical yet more recent posts (see ). Consistent with H3b, more recent claims more strongly guided impressions of a target’s current self. Especially when considering young adults whose personality traits may only now be stabilizing, employers may implicitly recognize newer online statements are more reflective of the applicant’s current self as they are more recent.

This finding is consistent with psychosocial theorizing that, as people change over time (particularly during adolescence (Demo, Citation1992; Jones & Meredith, Citation1996), users may be increasingly aware that online disclosures are permanent and accessible, and thus more recent posts are likely more valid reflections of individuals’ current selves. Just as with Birnholtz and Macapagal’s (Citation2021) interviewees caution when posting stigmatizing information, in the present context a job seeker recently posting problematic social media content may indicate to employers that either (a) the poster is simply careless or unaware of social media norms, or more likely (b) the characteristics and attributes presented via that more-recent problematic content is a more deliberate – and thus accurate – presentation of their current self. Alternately, and particularly given the particular types of problematic social media content used in this study (i.e., profane statements about a specific employer), employers may attribute long-past transgressions as dissatisfaction with a temporary job (rather than permanent career) or the naiveté of youth. Data broadly reflect this conclusion, with employers integrating more temporally distant posts less into their perceptions of the applicant offline, manifest in more favorable perceptions of the applicant’s PJ fit.

That the moderation effect of information temporality was weaker than the main effect of a post’s content is unsurprising: moderating effects are typically weaker relative to main effects (see Wilson & Sherrell, Citation1993). And yet, even from as discrete a cue as a timestamp, this moderation effect still remained surprisingly substantive driving observable differences in participants’ PJ fit perceptions (see ). Future work should further validate and explore temporality in warranting, both as a moderating effect and in isolation as a main effect.

Interpreting meaning for incremental theory

Finally, these findings provide some provocative insight into how recruiters’ dispositional factors may impact their perceptions of applicants based on mediated problematic content across time. Incrementalism had neither a direct or moderating effect on perceptions of PJ fit, significantly acting only as a moderating moderator (see ), so that the degree to which a recruiter believed people were capable of change significantly influenced the temporal moderation effect. Recruiters closer to the entity theory end of the continuum (i.e., ≥1 SD below the mean) did not have a significant difference in their perceptions of employability or person-job fit when viewing the applicant’ with problematic social media content post across time. Such a finding is expected, as entitists tend to have a high degree of stability in their perceptions of others, believing character remains static across time. This perspective is reflected in our data, as individuals aligned more strongly with entitivism reported no differences in their assessments of an applicant due to the presence of problematic social media content, regardless of the post’s temporality.

However, decomposition of the three-way interaction revealed an unexpected process: Recruiters that more strongly aligning with incremental theory (i.e., >1 SD above the mean), believing people can change over time, substantively deviated from these patterns, becoming more critical of posts with problematic social media content (and less critical of posts without problematic social media content) over time (see ). This was contrary to previous literature that robustly indicates incrementalists should believe people are dynamic and capable of change, and therefore be more forgiving toward past mistakes. So what happened here? One explanation may be that earlier job-related posts about specific workplace concerns evidenced early assimilation into work.

Figure 4. Visualizing Three-Way Interaction among Presence of a Social Media Faux Pas, Time Since the Faux Pas was Posted, and Recruiter’s Incrementalism.

Anticipatory socialization refers to the process of learning about work (Jablin, Citation2001). Initial knowledge about work and working is often provided by part-time jobs (Levine & Hoffner, Citation2006), providing anticipatory socialization that can enable individuals to successfully assimilate to their employment and career duties. Employees who started working earlier are perceived as more prepared to work, aware of the requirements and obligations of organizational roles and tasks (Carr et al., Citation2006). By posting about early work and work-related challenges, Alex Mayburn may have evidenced early socialization to work and working, and thus demonstrated improved PJ fit, even though Alex’s actual work experience (as demonstrated in Alex’s resume) was held constant across all conditions. This may further explain the lack of effects on perceived employability, as though Alex had the same work experience¸ by posting about it the target demonstrated an involvement and engagement in work that went beyond merely showing up for work.

A second, and potentially complementary, explanation of these results may be the fundamental attribution error, whereby individuals attribute freely-chosen behaviors (e.g., a social media post) to personality rather than a situation (Ross, Citation1977). Though entitists tend to attribute behaviors to the individual’s personality and characteristics, incrementalists are more likely to attribute behaviors to situations (Chiu et al., Citation1997). In other words, incrementalists tend to consider situational factors that could have influenced a behavioral outcome (Dweck et al., Citation1995). The problematic social media content in the stimuli included negative statements specifically about the applicant’s employer, rather than work or working in general (see Hartwell & Campion, Citation2020). In doing so, stimuli also involved critique of specific workplace policies, including the business’ handling of time-off requests and the boss’ work ethic. A recruiter further toward the incrementalist end of the continuum may have perceived these posts as Alex Mayburn’s valid critiques about their employer’s work policies, considering the situation that led to Alex posting these comments more than the post itself. Because scheduling and managerial duties may both may speak directly to job tasks, such critiques – particularly from a younger Alex Mayburn – may have been perceived as more indicative of a rigorous worker lamenting poor workplace policies that inhibited effective work, leading to improved perceptions of PJ fit by evidencing the target’s work ethic. As posts were more contemporary, recruiters may have become less able to ascribe critiques to the awareness of a diligent young worker, and instead perceived an older Alex Mayburn struggling to assimilate into organizational processes, thus reducing perceptions of PJ fit.

Ultimately, the three-way moderated moderation interaction suggests a perceiver’s dispositional factors may be just as critical to consider as specific message effects. An individual’s perceptions that others can change impact the degree to which information temporality affects perceptions. However, future work is needed to empirically support these inferences regarding incrementalists’ divergent perceptions. Moreover, dispositional factors do not appear to influence all perceptions stemming from various problematic social media content identically. Within the context of the hiring process, it may not be just a matter of what an applicant posted on social media. Instead, it appears dispositional factors – specifically implicit theories – of recruiters considering applicants may further interact with specific messages to influence some, but not all, perceptions. Future research should continue this line of inquiry and further consider what facets of employers’ dispositions influence applicant perceptions.

Limitations & future directions

An immediate limitation is the study’s inconsistent findings regarding employers’ attributions about applicants and subsequent focus on processes related to person-job fit. Hypothesized processes were partially-supported; but likewise were partially-rejected. Given prior findings of personnel perceptions and concerns over operationalization and history effects, we have focused on processes related to PJ fit as they are most consistent with the current body of scholarship in this area. However, additional work is needed to verify these assumptions. Specifically, future work should continue to replicate extant literature to ensure employers’ impression-formation processes remain stable after a decade of industry, social media, and sociotechnical environmental changes.

Additionally, future work should continue to expand our understanding of the role in social media information in the hiring process at all levels. Following prior research, the present work focused on one of the most common hiring scenarios: hiring a new entry-level manager. However, the presence and effects of social media information may vary by profession, industry, and job level (Carr, Citation2016), all factors for which current research (including this study) have yet to explore. For example, research must consider whether problematic social media content is less problematic for labor jobs than for white collar jobs, or (even more likely) jobs requiring a public presence or façade such as upper-management or public relations. Likewise, research should consider how job level (e.g., entry-level v. mid-management v. corporate suite position) may influence subsequent attributions, particularly as applicants at higher levels are likely already known to the organization and thus require different types and degrees of information seeking. And although the research employed a unisex name, participants were not asked to presume the applicant’s gender. As an applicant’s and recruiter’s gender can both independently and in concert affect applicant perceptions and hiring decisions (see Cole et al., Citation2004), future work may more purposefully explore gender assumptions and effects.

Future work can consider other additional processes and artifacts involved in online information seeking. Emphasizing negative information (even when not demonstrating problematic social media content), these findings may be readily interpreted as an impetus for job seekers to purge their social media history prior to applying for jobs. Yet positively-valenced information can have a positive effect on employers’ perceptions (C. T. Carr & Walther, Citation2014). Consequently, future work may seek to consider the temporal effects of information by valence, to see if positive social media posts have similar (i.e., increasingly beneficial) effects over time. Even more critical, as individuals’ social media posts are typically not monolithically positive or negative, future work should explore how employers identify specific posts and how an amalgam of positive and negative posts may influence employers’ perceptions. Prior work has indicated individuals are more likely to provide social support others who have depicted improvement over time (Vogel et al., Citation2018); and employers may be likewise more influenced to see an applicant’s employability or job fit as malleable if the corpus of their social media presence becomes more prosocial over time. Relatedly, individuals seem to form impressions of potential collaborators based on the history of their online activity rather than a discrete instance (Marlow et al., Citation2013); and employers’ impressions of an applicant may likewise differ when guided by an amalgam of the applicant’s social media history rather than a single post.

Finally, future work may consider the process by which employers may extract online information. The present research focused on the perceptual outcomes stemming from the content of a single isolated social media post, rather than the process of information seeking that ultimately reveals problematic social media content. Whether an employer conducts a focused search for specific exclusion criteria (e.g., key words/phrases in posts, seeking depictions of violence or hard drug use) or is simply browsing a user’s activity history can elicit different types of posts and perceptions. The present study experimentally exposed employers to a pre-identified tweet from as long as five years ago; but employers unlikely passively browse through five years of a user’s timeline. The processes by which employers seek and identify particular historical content and the conditions triggering attention are beyond the scope of the present work, but deserve focused research, particularly with respect to the resultant warranting value of an online artifact.

Conclusion

Coutu’s (Citation2007) case study, an interesting thought experiment fifteen years ago, likely now resonates with hiring personnel thanks to the persistence of most social media content. Rather than finding a news article nine pages deep in a Google result, employers can now readily seek and access years’ worth of an applicant’s own direct posts and behaviors, seeing them not only as they are now, but also as they have been across time. This work substantively contributes to our understanding of how employers evaluate applicants based on message and dispositional factors. Findings reveal employers account for the temporality of problematic social media content, as negative effects on perceived person-job fit from the same post lessened as the post was older. Optimistically, individuals may still be held to account for older self-presentations; but not to the same degree they are held accountable to more recent self-presentations online. More complex is the effect of dispositional factors, as the employers who most-believed individuals were capable of change over time were actually the ones more critical of applicants who had problematic postings from years prior. Ultimately, this work suggests applicants’ prior social media content – when accessed by employers—does influence employers’ perceptions of them, but that a single post from one’s distant past does not foreordain failure in future job searches.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data and Open Materials through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/H8UT4 and https://osf.io/h8ut4/?view_only=383ee28495a8440c88df95d71a61175e

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available online via the repository listed at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/H8UT4 and https://osf.io/h8ut4/?view_only=383ee28495a8440c88df95d71a61175e.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Warranting research has typically not assessed the match between resultant perceptions and the target’s actual offline characteristics. This may be because many subsequent perceptions and behaviors (e.g., whether to someone is extroverted, datable, or employable, respectively) rely only on initial online perceptions: We would not accept an initial date with a suitor perceived to be undatable just to confirm that perception in-person, nor hire the applicant perceived to be unable to possess job-required knowledge, skills, and abilities. Additionally, because online profiles and statements typically reflect offline personality faithfully (Back et al., Citation2010), the online-offline warrant may be presumed to be relatively strong, and thus impressions formed from online information generally assumed to faithfully reflect the target’s offline self (Van Der Heide et al., Citation2022). Subsequently, warranting research (including the present study) has typically focused on the factors leading to impression formation online; but – as one reviewer astutely noted – more work is needed to empirically demonstrate whether resultant perceptions of the offline self are indeed faithful and valid to the target’s actual offline self.

2. Notably, Harwell and Campion (2020) identified employers consider disparaging a specific employer as problematic, but not disparagement of employers or work in general. Simply making negative remarks about general employment does not have the same effect as denigrating a specific employer. This may be because all workers may perceive general frustrations with work or employers broadly; but remarks targeted toward a specific employer may be perceived as negatively impacting the employer’s image to external stakeholders (see Gossett & Kilker, Citation2006). This explanation would be consistent with prior interpersonal research, which found social media content denigrating a specific individual results in more negative impressions of the poster than when the same denigrating claim is made without disclosing the specific target (Edwards & Harris, Citation2016). Though these processes appear to run parallel, the differing perceptions of speaking ill of a specific employer rather than work in general deserves isolation and additional empirical support into the underlying mechanisms.

3. Stimuli messages for this study were selected from among ten messages pretested using a sample of college undergraduates (N = 30). The two messages used in this research were selected because the perceived employability and task attractiveness of the target of these two messages differed significantly between the problematic social media content and no problematic social media content conditions, while no significant differences were detected between message types in each condition.

References

- Adkins, C. L., Russell, C. J., & Werbel, J. D. (1994). Judgments of fit in the selection process: The role of work value congruence. Personnel Psychology, 47(3), 605–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1994.tb01740.x

- Antheunis, M. L., & Schouten, A. P. (2011). The effects of other-generated and system-generated cues on adolescents' perceived attractiveness on social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 16(3), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2011.01545.x

- Back, M. D., Stopfer, J. M., Vazire, S., Gaddis, S., Schmukle, S. C., Egloff, B., & Gosling, S. D. (2010). Facebook profiles reflect actual personality, not self-idealization. Psychological Science, 21(3), 372–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797609360756

- Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

- Berkelaar, B. L. (2017). Different ways new information technologies influence conventional organizational practices and employment relationships: The case of cybervetting for personnel selection. Human Relations, 70(9), 1115–1140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716686400

- Birnholtz, J., & Macapagal, K. (2021). “I don’t want to be known for that:”The role of temporality in online self-presentation of young gay and bisexual males. Computers in Human Behavior, 118, 106706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106706

- Bohnert, D., & Ross, W. H. (2010). The influence of social networking web sites on the evaluation of job candidates. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(3), 341–347. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0193

- Brandtzaeg, P. B., & Lüders, M. (2018). Time collapse in social media: Extending the context collapse. Social Media + Society, 4(1), 205630511876334. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118763349

- Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1996). Person–organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67(3), 294–311. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1996.0081

- Career Builder. (2018, August 9). More than half of employers have found content on social media that caused them NOT to hire a candidate, according to recent CareerBuilder survey [Press Release]. http://press.careerbuilder.com/2018-08-09-More-Than-Half-of-Employers-Have-Found-Content-on-Social-Media-That-Caused-Them-NOT-to-Hire-a-Candidate-According-to-Recent-CareerBuilder-Survey

- Carr, C. T. (2016). An uncertainty reduction approach to applicant information-seeking in social media: Effects on attributions and hiring. In R. N. Landers, & G. B. Schmidt (Eds.), Social media in employee selection and recruitment (pp. 59–78). Springer International.

- Carr, C. T. (2019). Have you heard? Testing the warranting value of third-party employer reviews. Communication Research Reports, 36(5), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2019.1683529

- Carr, C. T., Hall, R. D., Mason, A. J., & Varney, E. J. (2017). Cueing employability in the gig economy: Effects of task-relevant and task-irrelevant information on Fiverr. Management Communication Quarterly, 31(3), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318916687397

- Carr, C. T., Pearson, A. W., Vest, M. J., & Boyar, S. L. (2006). Prior occupational experience, anticipatory socialization, and employee retention. Journal of Management, 32(3), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305280749

- Carr, C. T., & Stefaniak, C. (2012). Sent from my iPhone: The medium and message as cues of sender professionalism in mobile telephony. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 40(4), 403–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2012.712707

- Carr, C. T., & Walther, J. B. (2014). Increasing attributional certainty via social media: Learning about others one bit at a time. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(4), 922–937. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12072

- Carter, S. E., & Sanna, L. J. (2008). It’s not just what you say but when you say it: Self-presentation and temporal construal. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(5), 1339–1345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.03.017

- Chiu, C.-Y., Hong, Y.-Y., & Dweck, C. S. (1997). Lay dispositionism and implicit theories of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.19

- Cole, M. S., Feild, H. S., & Giles, W. F. (2004). Interaction of recruiter and applicant gender in resume evaluation: A field study. Sex Roles, 51(9–10), 597–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-004-5469-1

- Costa, P. T., Jr., McCrae, R. R., & Löckenhoff, C. E. (2019). Personality across the life span. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 423–448. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103244

- Coutu, D. (2007). We Googled you. Harvard Business Review, 85(6), 37–47. https://hbr.org/2007/06/we-googled-you-2

- Davis, J. L., & Jurgenson, N. (2014). Context collapse: Theorizing context collusions and collisions. Information, Communication & Society, 17(4), 476–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.888458

- DeAndrea, D. C. (2014). Advancing warranting theory. Communication Theory, 24(2), 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12033

- DeAndrea, D. C., Tong, S. T., & Lim, Y.-S. (2018). What causes more mistrust: Profile owners deleting user-generated content or website contributors masking their identities? Information, Communication & Society, 21(8), 1068–1080. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1301523

- DeAndrea, D. C., Van Der Heide, B., Vendemia, M. A., & Vang, M. H. (2018). How people evaluate online reviews. Communication Research, 45(5), 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215573862

- Demo, D. H. (1992). The self-concept over time: Research issues and directions. Annual Review of Sociology, 18(1), 303–326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.001511

- Dhir, A., Kaur, P., Lonka, K., & Nieminen, M. (2016). Why do adolescents untag photos on Facebook? Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 1106–1115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.017

- Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C.-Y., & Hong, Y.-Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A word from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0604_1

- Edwards, J. R. (1991). Person-job fit: A conceptual integration, literature review, and methodological critique. In C. L. Cooper, & I. T. Robinson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 283–357). Wiley.

- Edwards, A., & Harris, C. J. (2016). To tweet or ‘subtweet’?: Impacts of social networking post directness and valence on interpersonal impressions. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.050

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, G., & Buchner, A. (2008). G*Power 3 (Version 3.0.10) [Statistical Analysis Software]. Institut fur Experimentelle Psychologie. http://www.psycho.uni-duesseldorf.de/aap/projects/gpower/

- Feintzeig, R., & Fuhrmans, V. (2018, August 8). Past social-media posts upend hiring. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/social-media-histories-upend-hiring-1533503800

- Gossett, L. M., & Kilker, J. (2006). My job sucks: Examining counterinstitutional web sites as locations for organizational member voice, dissent, and resistance. Management Communication Quarterly, 20(1), 63–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318906291729

- Hartwell, C. J., & Campion, M. A. (2020). Getting social in selection: How social networking website content is perceived and used in hiring. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 28(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12273

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Heslin, P. A., Vandewalle, D., & Latham, G. P. (2006). Keen to help? Managers’ implicit person theories and their subsequent employee coaching. Personnel Psychology, 59(4), 871–902. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00057.x

- Hogan, B. (2010). The presentation of self in the age of social media: Distinguishing performances and exhibitions online. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 30(6), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467610385893

- Hollenbaugh, E. E. (2021). Self-presentation in social media: Review and research opportunities. Review of Communication Research, 9, 80–98. https://doi.org/10.12840/ISSN.2255-4165.027

- Huang, X., Vitak, J., & Tausczik, Y. (2020, April). “You don’t have to know my past”: How We Chat moments users manage their evolving self-presentation [ Paper presentation]. CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’20), Honolulu, HI.

- Humphreys, L. (2018). The qualified self: Social media & the accounting of everyday life. MIT Press.

- Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin, & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication (pp. 732–818). Sage.

- Jansen, K. J., & Kristof-Brown, A. (2006). Toward a multidimensional theory of person-environment fit. Journal of Managerial Issues, 18(2), 193–212. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-08230-003

- Jones, C. J., & Meredith, W. (1996). Patterns of personality change across the life span. Psychology and Aging, 11(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.11.1.57

- Karl, K., Peluchette, J., & Schlaegel, C. (2010). Who’s posting Facebook faux pas? A cross-cultural examination of personality differences. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 18(2), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2010.00499.x

- Kwok, L., & Muñiz, A. (2021). Do job seekers’ social media profiles affect hospitality managers’ hiring decisions? A qualitative inquiry. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 46, 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.12.005

- Lane, B. L., Cionea, I. A., Dunbar, N. E., & Carr, C. T. (2023). Antecedents and effects of online third-party information on offline impressions: A test of warranting theory. Journal of Media Psychology, 35, 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000360

- Levine, K. J., & Hoffner, C. A. (2006). Adolescents’ conceptions of work: What is learned from different sources during anticipatory socialization? Journal of Adolescent Research, 21(6), 647–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558406293963

- Levy, S. R., Stroessner, S. J., & Dweck, C. S. (1998). Stereotype formation and endorsement: The role of implicit theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1421–1436. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1421

- Marlow, J., Dabbish, L., & Herbsleb, J. (2013, February 23-27). Impression formation in online peer production: Activity traces and personal profiles in github [ Paper presentation]. 2013 Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW’13), San Antonio, TX.

- Parks, M. R. (2011). Boundary conditions for the application of three theories of computer-mediated communication to MySpace. Journal of Communication, 61(4), 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01569.x

- Pascarella, E. T., Smart, J. C., Ethington, C. A., & Nettles, M. T. (1987). The influence of college on self-concept: A consideration of race and gender differences. American Educational Research Journal, 24(1), 49–77. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312024001049

- Peeters, G., & Czapinski, J. (1990). Positive-negative asymmetry in evaluations: The distinction between affective and informational negativity effects. European Review of Social Psychology, 1(1), 33–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779108401856

- Posthuma, R. A., Morgenson, F. P., & Campion, M. A. (2002). Beyond employment interview validity: A comprehensive narrative review of recent research and trends over time. Personnel Psychology, 55(1), 1–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2002.tb00103.x

- Ramirez, A., Jr., & Walther, J. B. (2009). Information seeking and interpersonal outcomes using the Internet. In T. Afifi, & W. Afifi (Eds.), Uncertainty, information management, and disclosure decisions (pp. 67–84). Routledge.

- Ramirez, A., Jr., Walther, J. B., Burgoon, J. K., & Sunnafrank, M. (2002). Information-seeking strategies, uncertainty, and computer-mediated communication: Toward a conceptual model. Human Communication Research, 28(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00804.x

- Reeves, B., Yeykelis, L., & Cummings, J. J. (2016). The use of media in media psychology. Media Psychology, 19(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2015.1030083

- Ross, L. (1977). The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Volume 10 (Vol. 10, pp. 173–220). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60357-3

- Roth, P. L., Bobko, P., Van Iddekinge, C. H., & Thatcher, J. B. (2016). Social media in employee-selection-related decisions a research agenda for uncharted territory. Journal of Management, 42(1), 269–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313503018

- Roulin, N. (2014). The influence of employers’ use of social networking websites in selection, online self-promotion, and personality on the likelihood of faux pas postings. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 22(1), 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12058

- Roulin, N., & Bangerter, A. (2013). Social networking websites in personnel selection: A signaling perspective on recruiters’ and applicants’ perceptions. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 12(3), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000094

- Rynes, S. L., & Gerhart, B. (1990). Interviewer assessments of applicant ”fit”. An Exploratory Investigation. Personnel Psychology, 43, 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1990.tb02004.x

- Scott, G. G., Sinclair, J., Short, E., & Bruce, G. (2014). It's not what you say, it's how you say it: Language use on Facebook impacts employability but not attractiveness. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17(8), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0584

- Shapka, J. D., & Keating, D. P. (2005). Structure and change in self-concept during adolescence. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 37(2), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087247

- Terenzini, P. T., & Wright, T. M. (1987). Students’ personal growth during the first two years of college. The Review of Higher Education, 10(3), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.1987.0022

- Tews, M. J., Stafford, K., & Kudler, E. P. (2020). The effects of negative content in social networking profiles on perceptions of employment suitability. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 28(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12277

- The Economist. (2021, April 29). Why are American workers becoming harder to find?. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/04/29/why-are-american-workers-becoming-harder-to-find

- Van Der Heide, B., Mason, A. J., Earle, K., Ulusoy, E., Pham, D., Rathjens, B., Zhang, Y., & Bredland, A. (2022, November 17). Does warranting theory function best outside of a truth-default state: Initial experimental evidence [ Paper presentation]. 108th annual meeting of the National Communication Association, New Orleans, LA.

- Vitak, J. (2012). The impact of context collapse and privacy on social network site disclosures. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(4), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2012.732140

- Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., & Crane, C. (2018). “Transformation Tuesday”: Temporal context and post valence influence the provision of social support on social media. The Journal of Social Psychology, 158(4), 446–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2017.1385444

- Walther, J. B., & Parks, M. R. (2002). Cues filtered out, cues filtered in: Computer-mediated communication and relationships. In M. L. Knapp, & J. A. Daly (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal communication 3rd ed., pp. 529–563). Sage.

- Walther, J. B., Van Der Heide, B., Hamel, L. M., & Shulman, H. C. (2009). Self-generated versus other-generated statements and impressions in computer-mediated communication: A test of warranting theory using Facebook. Communication Research, 36(2), 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650208330251

- Wilson, E. J., & Sherrell, D. L. (1993). Source effects in communication and persuasion research: A meta-analysis of effect size. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 21(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02894421