ABSTRACT

Most children love stories, but studies examining their potential for growth are rare. In this qualitative study, we interviewed 66 children to understand how stories can be meaningful for them. Before the interview, they watched the Disney • Pixar film Inside Out. The story of this film follows the renowned framework of the Hero’s Journey and has been lauded for its premise concerning emotions and human connectedness. Findings from the in-depth semi-structured duo interviews are the first to reveal that children can be moved by moral beauty in stories. Another novel finding was that the film encouraged children to follow the protagonist on her adventure and in doing so acquired the same insights as her. Given that the Hero’s Journey framework is often applied by writers, it is possible that the idea of acquiring the same insights as the protagonist applies to many stories. The story was also found to be meaningful for children because it sparked their social intelligence and inspired them to never give up. Altogether, these findings indicate that stories can be an accelerated way of gaining life experience and wisdom.

More than two thousand years ago, Aristotle already argued that stories can give insights about life and spark personal growth (335 B.C.E., Citation2013). Findings from the now blossoming research field of positive media psychology indicate that stories can indeed be meaningful in that way (Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2010; Raney et al., Citation2020). Positive media psychology is defined as “the field of study devoted to examining processes and relationships associated with media use leading to thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that contribute to individual well-being and flourishing” (Raney et al., Citation2020, p. 2). Within this field, many ways in which stories can be meaningful have been illuminated. However, most studies so far have included only adults, while children are probably even more attracted to story worlds (Dubourg & Baumard, Citation2021).

An important way in which stories can be meaningful is by showing how good and heroic people can be. The emotional response to witnessing such acts of moral beauty has been labeled as “moved by love” (Fiske, Citation2020) or “moral elevation” (for a review, see Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016), which is a positive emotion that opens people’s hearts to others and sparks a desire to do good. Although research on this emotion is rapidly growing, hardly anything is known about this in adolescents, let alone younger children. Both childhood and adolescence are marked by major developmental leaps when it comes to understanding the perspectives and motivations of others (Crone & Dahl, Citation2012; Dahl et al., Citation2018; Weimer et al., Citation2021) – which is essential for feeling moved when witnessing moral beauty (Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). This along with the fact that diving into story worlds is one of children’s favorite activities (Dubourg & Baumard, Citation2021; Rideout et al., Citation2022), makes it important to extend the field of positive media psychology to a younger audience.

Therefore, the question at the heart of this study is how stories can be meaningful for children. The research question was approached with a qualitative research design, for which children were asked to watch the widely acclaimed Disney • Pixar film Inside Out (Docter & del Carmen, Citation2015). This film is lauded for its meaningful premise concerning emotions and human connectedness, and contains portrayals of moral beauty (Anwar, Citation2015; Gross, Citation2015; Keltner & Ekman, Citation2015). Moreover, the story is a textbook example of the Hero’s Journey – which is a classical narrative framework that has been applied in many famous myths and stories from all over the world (Campbell, Citation2008; Vogler, Citation2020). The Hero’s Journey involves a hero who goes on an adventure, overcomes challenges, and returns changed. After watching the film, children were invited to share their experiences with this film and other stories in an in-depth semi-structured duo interview. This qualitative research design enabled us to shed light on the emotion “moved by love” among children and to uncover novel ways in which stories can be meaningful for them.

Stories and Insights About Life

Stories in the media that are characterized by both cognitive- and emotional challenges are most likely to be characterized as meaningful (Bartsch & Hartmann, Citation2017; Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2010). When mastering the challenges that arise while watching, it can prompt experiences of deeper insight, and provide the viewer with opportunities for personal growth. These experiences come along with thinking about the thoughts and feelings that were experienced (Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2010). These introspective thoughts have been conceptualized as “contemplation” (Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2010; Raney et al., Citation2020). When a story is experienced as meaningful, often valuable insights about life are gained, for instance, concerning the value of human virtue and the importance of human connectedness, but also about the inevitability of sadness in our lives (Janicke & Oliver, Citation2017; Oliver & Hartmann, Citation2010). While children love stories (Dubourg & Baumard, Citation2021; Rideout et al., Citation2022), it is yet unknown whether they can have these meaningful media experiences.

Films that are challenging and lead to contemplation are often films with nominations for or winning an Academy Award or Golden Globe Award, and higher audience ratings (Oliver et al., Citation2014). Given that popular family films regularly receive such great acclaim (Rotten Tomatoes, Citation2021), we argue that these films can be a promising way to prompt introspection and spark growth in children. This idea can be further substantiated by previous findings demonstrating that, for families, watching a film together is often considered “quality time” and that parents indicated that they use these stories to talk about important topics, specific values, and what is right and wrong (Coyne et al., Citation2014; Sanders et al., Citation2019).

Just like storybooks for young children (for a review, see Mar, Citation2018), we think that watching a film can be a rich experience to learn about one’s own inner world and that of others. Reading storybooks is found to be related to mentalizing – which refers to the ability to understand others by describing mental states to them (De Mulder et al., Citation2022; Mar, Citation2018). During middle childhood and adolescence, children advance in their understanding of mental states of others, including their intentions and perspectives (Crone & Dahl, Citation2012; Dahl et al., Citation2018; Weimer et al., Citation2021). Teens today even prefer stories about people with lives that differ from their own (Rivas-Lara et al., Citation2022). Despite this, hardly anything is known about how stories can foster the development of mentalizing skills during these phases of life (De Mulder et al., Citation2022; Mar, Citation2018). However, a recent study indicates that stories can enhance mentalizing in children and adolescents, primarily stories that are characterized as sad, moving, and beautiful, and of which one has learned something important about other people or themselves (De Mulder et al., Citation2022). The present study aims to shed light on how a story can exactly challenge current thinking and provide children with novel insights about life.

Stories and Moral Beauty

When stories in the media portray moral beauty, it can evoke the emotion “moved by love” (Fiske, Citation2020) or “moral elevation” (Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). This emotion can be triggered when watching acts of compassion, kindness, forgiveness, gratitude, love, bravery, self-sacrifice, or any other strong display of virtue (Fiske, Citation2020; Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). Psychological characteristics of this emotion are being more optimistic toward humanity and an increased openness toward others (Fiske, Citation2020; Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). Physiological characteristics are a warm and rising feeling in the chest, moist eyes or tears, a lump in the throat, and chills or goosebumps (Fiske, Citation2020; Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). Finally, the motivational tendencies that come along with this emotion are a desire to be a better person, to connect with others, and to help others. This emotion is also related to actual helping (Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). In other words, being “moved by love” metaphorically opens our hearts to others (Fiske, Citation2020; Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016).

An act of virtue can only be experienced as moral beauty when the observer feels moved and uplifted (Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). Otherwise, an act is only cognitively experienced as moral goodness. A recent neuroimaging study indicated important differences between experiencing moral beauty and moral goodness (Cheng et al., Citation2020). Compared to experiencing moral goodness, experiences of moral beauty induced greater brain activity implicated in more advanced cortical regions – including the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). This indicates that for being moved by moral beauty, it is important to understand the mental states of others, while this was not important for the experience of moral goodness. There is now accumulating evidence that the mPFC is recruited when experiencing moral beauty (Englander et al., Citation2012; Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). Given that exactly this brain region is under development during adolescence (Crone & Dahl, Citation2012; Dahl et al., Citation2018), makes it interesting to examine feelings of moral beauty among adolescents.

A recent study indicates that feeling moved by moral beauty is indeed prevalent among adolescents (de Leeuw et al., Citation2022). However, the question is at what age this emotion starts to emerge. Being moved upon watching moral beauty is often characterized by a mixture of both sadness and joy (Oliver & Hartmann, Citation2010; Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). The ability to experience mixed emotions develops during childhood (Larsen et al., Citation2007; Zajdel et al., Citation2013). More specifically, around the age of 5–7 years, most children appear to be able to understand mixed emotions in others, and around the age of 8–12 years, most children appear to be able to experience mixed emotions themselves. Altogether, these findings indicate that being moved upon witnessing moral beauty is an advanced emotion that probably starts to emerge in childhood and becomes more sophisticated during adolescence.

In a previous qualitative study, several cognitive-developmental stages of understanding experiences of beauty – including moral beauty – have been identified (Diessner et al., Citation2016). In Stage 1: Prettiness, children (around the age 3–6 years) consider something as beautiful purely because they like it. In Stage 2: Beauty is Big and Amazing, children (around the age 6–12 years) admire those who are kind and help others, but do not understand altruism that goes beyond concrete behaviors. In Stage 3: Beauty is Emotionally Moving, people (around the age of 12 and older) can think abstractly and imagine the inner states of others, and often define beauty in terms of their own emotional experiences to beauty. In the present study, we dive deeper into experiences with moral beauty and, instead of asking openly about their experiences with beauty, children were exposed to moral beauty and asked how it made them feel. This helps us to shed light on when children start to experience feelings of beauty and what is developmentally required for these feelings.

The Present Study

In this study the following research question was examined: How can film stories be meaningful for children? By combining Aristotle’s insights with breakthroughs in positive media psychology, we defined an experience with a story as meaningful when it leads to insights about life, feelings of moral beauty, contemplation, feelings of inspiration, and/or a desire to do “good.” This study is unique as it is not only about children but also with them by giving them a voice (Curtin, Citation2001; Kirk, Citation2007; Woodgate et al., Citation2017). To involve children directly, qualitative in-depth interviews were conducted. This methodological approach helps to gain insight into their world of experience and into the personal meanings that they allocate to their experiences (Kirk, Citation2007; Woodgate et al., Citation2017). Moreover, this explorative approach enables us to discover novel ways in which experiences with stories can be meaningful. It lays the empirical groundwork and theoretical base for further verification and potential generalizations of these findings in later work.

Materials & Methods

Participants

In this study, 66 children aged 4–15 years participated (56.06% were female).

Design & Procedure

A qualitative approach was applied as this helps to “enter into the world of participants, to see the world from their perspective, and in doing so make discoveries” (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2014, p. 14). To investigate how film stories can be meaningful for children, in-depth semi-structured duo interviews were conducted. Participants were recruited by sending information letters about the study around in our personal networks. Moreover, letters were also distributed among parents of a primary school with the aim to involve children with different backgrounds. Children were interviewed with a friend or a sibling to help them feel more comfortable (Curtin, Citation2001).

Initially, children between 8–12 years were invited to participate because around this age most children become able to experience mixed emotions (Larsen et al., Citation2007; Zajdel et al., Citation2013). This enabled us to shed light on when feelings of moral beauty start to emerge. After 12 interviews and in line with the principles of theoretical sampling (Silverman, Citation2020), we also included children younger than 8 years and older than 12 years to facilitate more variation in the sample. Children between 5–7 years were invited because most of them can understand mixed emotions in others and start to develop the ability to experience these emotions themselves (Larsen et al., Citation2007; Zajdel et al., Citation2013). The ones older than 12 years were included to cover more years of adolescence (Sawyer et al., Citation2018). Adolescence is a key developmental period for the social brain network – a network of regions important for skills as understanding social situations and perspective-taking (Crone & Dahl, Citation2012; Dahl et al., Citation2018), which is important for experiencing moral beauty (Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). After 26 interviews no new insights were forthcoming, which made us believe that saturation was reached (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2012). We conducted seven more interviews, which also did not lead to new insights. In the end, we interviewed 42 children between 8–12 years, 19 children that were younger (4–7 years), and five that were older (13–15 years). An overview of all participants is presented on the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/5gkvu/?view_only=367b869aed284b36b35be01fe9cc0792).

Participants were asked to watch the film Inside Out before the interview. The interviews took place at school or at home, to make the children feel comfortable and free to talk (Curtin, Citation2001). All interviews were conducted by two interviewers, of which one was leading the interview while the other made sure that all topics would be covered. The main interviewer was always unacquainted with the interviewees. The interviewees were first told about the aim and content of the interview. After that, it was explained why the interview was recorded and transcribed, and how their answers would be anonymized and treated confidentiality. Although the interviewees and their parents already gave consent, the interviewees were asked again whether they agreed to the recording of the interview. It was explained that there were no right or wrong answers and that it was all right if they did not have an answer (Curtin, Citation2001).

The length of the interview depended on the interviewees. This is because children, especially younger ones, can have a shorter attention span (Kirk, Citation2007). The interviewers watched for both verbal and nonverbal cues of decreased attention (Curtin, Citation2001; Woodgate et al., Citation2017). Most interviewees liked to participate, and on average the interviews lasted 1 hour 20 min. Interviewees were given a gift card of € 10 for their participation. All interviews were transcribed verbatim in Word. After the study was finished, the children and their parents received a news letter with the findings. The study is approved by the ethics committee at the Behavioural Science Institute, Radboud University (ECSW-2019-143).

The Film Inside Out

The film Inside Out was selected as it has the potential to be meaningful for children. Inside Out tells the story of 11-year-old Riley. Almost the whole story is set in Riley’s mind, where her emotions – Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear, and Disgust – conflict on how to help Riley best in her new life after moving. The story follows the structure of the Hero’s Journey (Campbell, Citation2008; Vogler, Citation2020), with Joy going on an adventure, facing challenges, and coming back changed. To get the emotion animations consistent with scientific research, the filmmakers had extensive consultations with psychologists, including Dr. Dacher Keltner and Dr. Paul Ekman (Anwar, Citation2015; Gross, Citation2015; Keltner & Ekman, Citation2015). Meaningful experiences with a film are often characterized by gaining valuable insights about life (Janicke & Oliver, Citation2017; Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2010) and such insights were already acquired by the filmmakers themselves before the film was finished: In an interview, the director Pete Docter explained that while working on the film and after gaining all the knowledge on emotions, he had a revelation that “the real deeper reason we have emotions is to connect us together” (Gross, Citation2015). Human connectedness is often a key theme in films that are experienced as meaningful (Janicke & Oliver, Citation2017; Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2010), and Inside Out is applauded for its message to embrace sadness as an important way to connect with others (Anwar, Citation2015; Gross, Citation2015; Keltner & Ekman, Citation2015).

In addition to providing meaningful insights, Inside Out is praised for its smart, adventurous, and challenging storyline (Bozdech, Citation2015; Nashawaty, Citation2015). This indicates that the film fulfills the characteristics of being both intellectually and emotionally challenging – both features of a meaningful film (Bartsch & Hartmann, Citation2017; Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2010). Finally, the film is appreciated by the audience as it is one of the highest-rated animated films of all time (Rotten Tomatoes, Citation2021). The film is admired by critics as well and received 97 awards, including the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature Film (IMBd, Citation2016). And as films that receive greater acclaim are more likely to feature contemplative and emotional themes (Oliver et al., Citation2014), it can be concluded that Inside Out is a meaningful film to many.

Interview Style & Guide

An important challenge in doing research with children is to bridge the existing power imbalance between the participating children and the interviewing adults (Curtin, Citation2001; Kirk, Citation2007; Woodgate et al., Citation2017). One way to build trust and a bond is to start with easy questions to break the ice (Curtin, Citation2001; Kirk, Citation2007). Our icebreaker was asking the children what their favorite film is and to explain why they liked it, after we first shared our own favorite film with them. All interviewers were genuinely interested in the children and valued their perspectives, which contributed to building trust and invigorated the children’s experience of being experts (Curtin, Citation2001; Kirk, Citation2007).

The open structure of the interviews enabled children to go off track, which helped them to feel more comfortable when returning to speaking about the interview topic (Woodgate et al., Citation2017). To sustain interest and prevent the children from being bored (Kirk, Citation2007), we discussed moments of hilarity that occur in the film. The interview guide helped to make sure that all topics were covered. This included the key question “Was there a part of the film that you had to think about?” and two important scenes from the film. When the interviewees did not spontaneously start to talk about these scenes, they were given the stills of these scenes and invited to explain in their own words what happened in the sequence. The stills from the film, but also the scenes themselves were shown as an elicitation technique to spark the spontaneous sharing of thoughts from the interviewees (Curtin, Citation2001; Patton, Citation2014). All stills and the most important scenes are available on the OSF (https://osf.io/5gkvu/?view_only=367b869aed284b36b35be01fe9cc0792).

One of the two important scenes is the scene in which the protagonist, Joy, discovers the importance of Sadness – this is when Sadness comforts Bing Bong (Tucker, Citation2017; Weiland, Citation2016b). The other scene portrayed the character Bing Bong sacrificing himself to help Joy, which is an act that can lead to the experience of being “moved by love” (Fiske, Citation2020; Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). In line with the study from Larsen et al. (Citation2007), interviewees were asked how they felt when they saw this. If they only mentioned one emotion, they were asked: “Did you feel anything else?” If they understood that Bing Bong handled it on purpose, they were asked what they thought of it and if they would have done the same. During the data collection, the interview guide was further fine-tuned based on questions that were found to elicit in-depth answers from the children. The final interview guide is also available on the OSF (https://osf.io/5gkvu/?view_only=367b869aed284b36b35be01fe9cc0792).

Strategy of Analysis

The transcripts were analyzed using the qualitative data analysis program MAXQDA 2022 (VERBI Software, Citation2022). Following a grounded theory approach, the analysis consisted of three coding phases (Chun Tie et al., Citation2019; Patton, Citation2014; Rubin & Rubin, Citation2012). In the initial coding phase, the data were open coded while looking for parallels and differences in the answers of the children. In the intermediate coding phase, codes were specified into more abstract concepts and interconnections between the concepts were drawn. In the advanced coding phase, concepts became abstract and were reduced into interrelated concepts relevant for answering the research question. Gathering of the data and the analysis alternated (Chun Tie et al., Citation2019; Patton, Citation2014), which enabled it to constantly compare the answers of the children and inductively gain new insights. After each interview, the interviewers shared their observations and experiences with each other (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2014; Patton, Citation2014). Our research team consisted of experts from communication science, an expert on child development, and a screenwriter, whom all contributed with their unique perspectives in analyzing the data. Memo writing helped in interpreting the data and keeping track of the steps in the analysis. The iterative and recursive character of the study (Chun Tie et al., Citation2019; Corbin & Strauss, Citation2014; Patton, Citation2014) led to novel theoretical insights on how stories can be meaningful for children.

Quality Measures: Validity and Reliability

During the interviews, internal validity was obtained by member checks by which the interviewers check whether they interpreted the answers of the interviewees correctly (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2014; Patton, Citation2014). Working together in a team enabled interviewer and analyst triangulation, which prevents single interviewer or analyst’s blinders (Patton, Citation2014). The constant (and sometimes intense) discussions during the peer debriefings also enhanced the internal validity and the reliability of the analysis. Finally, the cyclic and iterative character of our approach strengthened the validity as well (Patton, Citation2014).

Results

Before presenting how film stories can be meaningful, it is essential to highlight the importance of amusement for children. Many children indicated that good films are humorous, fun (including a happy end), and suspenseful.

How Film Stories Can Be Meaningful for Children

Concerning the question of how film stories can be meaningful for children, our findings led to the four following ways:

#1- Stories Can Fuel Social Intelligence

Children liked to make sense of the behavior of characters, for which they use their social intelligence skills. The following part of an interview illustrates that children are aware of the motives and feelings of the characters:

Interviewer: “How does Bing Bong feel here?”

Interviewee 1: “Sad.”

Interviewee 2: “Veeeeeeery sad.”

Interviewer: “Yes, very sad. And why is he sad?”

Interviewee 1: “Because his cart … he is of course very attached to that. Then suddenly it is gone.” (Boys, respectively 10 and 12 years old)

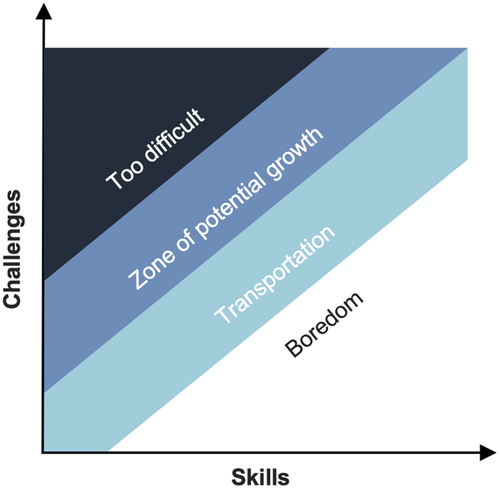

Findings indicated that children not only applied their social intelligence skills while watching the film, but challenges in creating a coherent story – the plot-story-construction – could also be an opportunity for further developing these skills. As illustrated in , children were found to be optimally challenged in their plot-story construction when they are transported into the story and their skills match the challenges in the plot-story construction. However, at times something happens that they do not fully understand and makes them think. At this point, children are challenged within what we labeled as the zone of potential growth. For children in this zone, the process of transportation is interrupted as they wondered what exactly happened. With help from others, from continuing with watching the film or from rewatching, they can come to understand this.

To illustrate this with Bing Bong’s heroic sacrifice: Children within the zone of potential growth, wondered whether Bing Bong jumped out the rocket or not, and why he did this. For them the process of transportation is interrupted as they wondered what exactly happened, but they are close to understanding Bing Bong’s motivation to get out of the rocket – to help Joy. During several interviews, one or both interviewees even discovered that Bing Bong did not fall out of the rocket, but instead jumped out of it and why he did so. The following passage of an interview illustrates how children in the zone of potential growth can come to understand the motivation of a character by rewatching a scene. This passage starts after the interviewees watched the beginning of this scene and it was stopped after Bing Bong saying: “Come on, Joy. One more time. I’ve got a feeling about this one.,” indicating that he is going to sacrifice himself:

Interviewee 1: “That is also … ”

Interviewer 1 [encouraging]: “Yes?”

Interviewee 2:“But then … he flies out.”

Interviewee 1: “He flies out … no, but he falls … he does it on pur … he goes out of it on purpose.”

Interviewee 2: “Yes.”

Interviewer 2: “Why do you think that, [name interviewee 1]?”

Interviewer 1: “So, he already knows here that it will work?”

Interviewee 1: “Yes.”

Interviewer 1: “And why will it work?”

Interviewee 1: “Because it … because the rocket was just too heavy and now it’s getting lighter because Bing Bong is going out of it.” (Boys, both 7 years old)

Children really liked discovering something novel like this. When they discovered something novel during the interviews, they were often very excited. Novel insights included awareness about the motives and feelings of others but could also include awareness of one’s own feelings. Many children recognized the animated emotions – Joy, Sadness, Fear, Anger, and Disgust – in themselves, which helped them to comprehend their own inner life.

#2- Stories as an Opportunity to Experience (Moral) Beauty

Another way in which Inside Out proved to be meaningful is the opportunities for experiencing moral beauty. Interviewees spontaneously indicated appreciating acts of compassion, kindness, love, and bravery. Moreover, children experienced Bing Bong’s self-sacrifice as beautiful. Upon experiencing this, children expressed that they would have done the same, also in a comparable real-life situation. Experiences of moral beauty were sometimes characterized by tears or moist eyes. An interviewee spontaneously said she got goosebumps. When asked why she explained:

“That he sacrifices himself […] that touches me.” (Girl, 11 years old)

The youngest children who indicated experiencing moral beauty were 6 and 7 years old, but they were exceptions. Experiences of moral beauty were more prevalent from 8 years and older. Feelings of beauty were not only experienced upon observing moral acts of beauty but also upon witnessing the protagonist having a revelation.

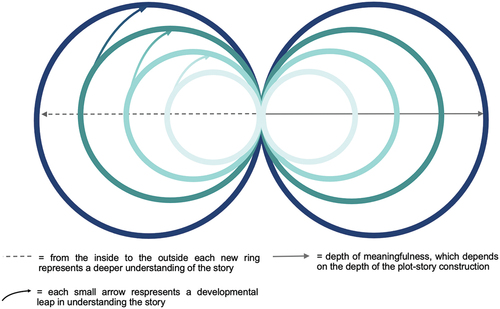

#3- Stories to Watch the Protagonist Grow and Acquiring the Same Insights

When watching the film Inside Out, children felt encouraged to follow the protagonist’s development and acquire the same insights as her. More specifically, children followed Joy and the path she takes in discovering that sadness is important and that collaboration between the emotions is important. When children indicated to have learned from the story it was often related to what Joy learned. The four levels of this development that we were able to distinguish are described in . Compared to younger children, older children were more likely to have acquired insights at the final level. However, there were also younger children who have acquired more in-depth insights than some of the older children.

Table 1. How children followed the protagonist on her adventure and with doing so acquired the same insights as her.

#4- Stories Can Inspire to Never Give Up

Children admired Joy’s perseverance as well. In one of the interviews, a child spontaneously expressed that Joy even inspired her to never give up:

Interviewee: “I also think it is a very beautiful film, because you can learn a lot from it.”

Interviewer: “Can you tell me what you have learned from it?”

Interviewee: “[…] Joy always tries and tries … so that makes me, it helps me think ‘Oh you should try again,’ because she does, and tries and for her it often leads to success.” (Girl, 8 years old)

Meaningfulness as a Process of Challenges and Growth

Challenges in the Plot-Story Construction

Our findings indicated that every time children gained a novel insight and integrated another plot element into the story construction, the story could become more meaningful for them. The full process of this is illustrated in . In the circle at the left, it is depicted how children are challenged in the plot-story construction (see also and #2- Stories can Fuel Social Intelligence). Co-construction with others, continue with watching the film or watching it one more time can help them to overcome that challenge. When children overcome the challenge by acquiring insight and understanding why characters in the film do what they do, they are “launched” into the circle on the right. Then the story becomes meaningful for them, and they can come to experience feelings of beauty and appreciation. Appreciation was experienced for the characters who displayed moral beauty or for the film itself. Children appreciated it that this film helped them to “understand what’s going on in your head” (Girl, 9 years old) and they found it “cool that they [the makers] animated it like that” (Boy 12, years old). They considered the story also as “well thought out” (Girl, 13 years old).

Appreciation can motivate children to watch the film again, which can lead to an expansion of the whole process, leading again to novel insights. Every time a novel insight was acquired, children had a deeper understanding of the story which could lead to stronger experiences of meaningfulness and appreciation. This interplay between plot-story construction and the depth of meaning is illustrated in . Novel insights could be obtained on character level, on scene level and on story level, which all could give meaningful insights for life. A meaningful insight on a character level indicates that children acquired an insight that is meaningful for them based on witnessing a character in the film. For instance, by recognizing the emotions of the characters in themselves (see #1- Stories can Fuel Social Intelligence). An insight on scene level indicates that children acquired an insight that helps them understand what is happening within a scene. For instance, an insight on this level is acquired when children come to understand that Bing Bong jumps out of the rocket on purpose (see #1- Stories can Fuel Social Intelligence) or when children come to understand that Sadness is important when they witness her comforting Bing Bong (see Level 2 of #3- Stories to Watch the Protagonist Grow and Acquiring the Same Insights). An insight on a story level indicates that children acquired an insight that helps them understand how what is happening on a scene level is important for the full story. An insight on this level can be that children come to understand that Bing Bong jumps out of the rocket for the greater good (see #1- Stories can Fuel Social Intelligence). All children who experienced Bing Bong’s deed as moral beauty understood what he did on a story level, which seem to imply that for the experience of moral beauty (see #2- Stories as an Opportunity to Experience Moral Beauty) insight on a story level is required.

When children integrated (almost) all plot elements into their plot-story construction, their experience of meaningfulness and appreciation of the film appears to be the richest. At this level, children understand that for living a full life it is important that all emotions work together (see Level 4 of #3- Stories to Watch the Protagonist Grow and Acquiring the Same Insights). With these insights on a story level, children could also come to admire Joy’s perseverance (see #4- Stories can Inspire to Never Give Up). More quotes to illustrate the findings are presented on the OSF (https://osf.io/5gkvu/?view_only=367b869aed284b36b35be01fe9cc0792).

From Pure Sadness to Moral Beauty

Not only the extent to which children integrated the plot elements into the plot-story construction was important for the experience of meaningfulness, but also their ability to experience different emotions simultaneously. More specifically, for some Bing Bong’s death led to pure feelings of sadness while for others it was the most beautiful part of the film. Only children who experienced mixed emotions and understood why Bing Bong jumped on a story level were able to experience his deed as moral beauty. The following quote illustrates a child who shed tears of sadness when witnessing Bing Bong’s heroic sacrifice, but did not experience this as moral beauty:

Interviewer: “Did you only feel sadness, or did you feel something else too?”

Interviewee: “Only sadness.” (Girl, 9 years old)

When children were able to experience positive emotions next to feelings of sadness, they could experienced moral beauty. Experiences of moral beauty were the strongest when feelings of beauty overshadowed the feelings of sadness. To illustrate this:

Interviewer: “And what is bigger? That you found it beautiful or that you found it sad?”

Interviewee: “I think it is bigger that I found it beautiful.” (Girl, 15 years old)

Discussion

The present study is the first to shed light on how a story can be meaningful for children. One of the most novel insights is that children can be moved by moral beauty, just like adults (Fiske, Citation2020; Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). Another novel finding is that stories can provide children with meaningful insights about life, which is also in line with previous work among adults (Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2010; Raney et al., Citation2020). The exploratory approach of this study led to the discovery of a new potential underlying mechanism explaining how a story can provide meaningful insights: When following a protagonist on an adventure, the viewer can acquire the same insights. Children’s meaningful experiences could also involve growth in their social intelligence, and admiration of perseverance. The depth of meaningfulness appears to depend on the amount of plot elements children integrated into their plot-story construction. When watching, children actively created a coherent story by trying to link together everything visible and audibly present in the film (Bordwell et al., Citation2019). The more they linked to each other, the more meaningful the story became for them.

Challenges in a Story as an Opportunity for Growth

Insights in the Inner World of Others and Oneself

The findings of this study highlight the importance of challenges in a story as an opportunity for growth. The first way in which children can grow is in their social intelligence. Social intelligence is described as “being aware of the motives and feelings of self and others” (Park & Peterson, Citation2009, p. 2), which is a sophisticated ability that is related to prosocial behavior (for a meta-analytic review, see Imuta et al., Citation2016). Sometimes something happens in a story that children do not fully understand, which is in line with what is described as “being challenged” among adults (Bartsch & Hartmann, Citation2017; Menninghaus et al., Citation2019; Schindler et al., Citation2017). When it is within their grasp to understand, children are in what we called the zone of potential growth. This idea closely links to Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) classical concept of the zone of proximal development, which is defined as “the distance between the [child’s] actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (p. 86). The findings of our study indicate that adults, siblings, and friends could help children obtain novel insights. Not only others could help but watching the film again (and again) helped to gain novel insights as well.

Challenges could arise at any time in the plot-story construction, but among the children in our study, one event appeared to stand out: Bing Bong’s death. Bing Bong was a beloved character for most of the children and seeing him dying was poignant. It was also challenging for them to comprehend that he jumped out of the rocket on purpose to help. In other words, his heroic deed was both emotionally and cognitively challenging – which are found to be characteristics of a meaningful film among adults (Bartsch & Hartmann, Citation2017). This challenging scene provided the children with the opportunity to think about Bing Bong’s motivations for doing this, which eventually could lead to understanding his point of view and even to being “moved by love” and considering his act as beautiful. Bing Bong is the first Pixar hero who died onscreen (Heroes Wiki, Citation2015), and by doing this, Pete Docter and his team were able to bring the young audience a novel insight: that some heroes sacrifice themselves for something that is bigger than their own lives.

During the interviews, we noticed how children really liked to comprehend the feelings, motives, and behaviors of the characters. The children genuinely enjoyed being challenged and were thrilled when they discovered something new. This is in line with previous work indicating that appraisals of intrinsic pleasantness and detecting something novel are preeminently important in aesthetically appealing pieces (Menninghaus et al., Citation2019; Schindler et al., Citation2017). Recently, Dubourg and Baumard (Citation2021) hypothesized that preferences for stories in imaginary worlds rely on exploratory preferences, and that this drives the motivation to explore novel worlds. Our findings indicate that the opportunity to explore novel worlds is indeed intrinsically rewarding.

In his much-discussed book The Better Angels of Our Nature, Pinker (Citation2011) argued that stories in the media helped humans to evolve away from violence toward collaboration and altruism. The present study provides evidence for the idea that stories “can prompt people to take the perspectives of people unlike themselves and to expand their circle of sympathy to embrace them” (Pinker, Citation2011; p. XXV, see also Singer, Citation2011). The findings of the present study contribute to the sparse, but accumulating evidence that film stories, just like storybooks (De Mulder et al., Citation2022; Mar, Citation2018), can spark social intelligence in children. Our findings helped to understand how this can work and how this cannot work yet, by revealing how important it is that children are in the zone of potential growth.

Character Arcs and Insights about Life

The findings of this study illuminated that novel insights about life could be acquired with children following the protagonist on her adventure and with that obtained a greater awareness about the value of emotions, just like her. Inside Out is a Hero’s Journey (Campbell, Citation2008; Vogler, Citation2020) in which the protagonist changes in a positive way over the course of the story. This is called a Positive Change Arc (Weiland, Citation2016a). Based upon this knowledge of storytelling and our findings, we would like to formulate a new hypothesis, namely that when watching a film with a Positive Change Arc, the viewer can grow accordingly. An avenue for future research is to do qualitative interviews with another film with a Positive Change Arc to examine whether watching this could lead to meaningful insights about life in line with the development of the protagonist in that story. It would also be interesting to examine this idea among adults and to see to what extent our ideas on how exactly stories can be meaningful () apply to them as well.

Another avenue for future research is to dive deeper into the emotions that come along with obtaining novel insights. Based on our findings, we were not able to draw conclusions on what children were exactly feeling when they acquired a novel insight. We observed excitement and sometimes also surprise – which is known as an aesthetic emotion (Menninghaus et al., Citation2019; Schindler et al., Citation2017), but we wonder whether children also experienced awe when they discovered something new. In recent work from the field of positive psychology, awe is defined as “the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your current understanding of the world” (p. 7). Awe can be evoked when having an epiphany, which is “when we suddenly understand essential truths about life” (Keltner, Citation2023, p. 17). It is possible that the children in our study experienced awe when they gained the same insights as Joy and understood why sadness is important in life. Awe has been considered to play an important role in meaningful media experiences (Vorderer & Klimmt, Citation2021). However, how awe can be evoked by media is not fully understood. Based on our findings, we think that one of the ways in which awe can be triggered, is when we are having a revelation, just as the protagonist (and the filmmaker).

At heart, stories with the framework of a Hero’s Journey portray a protagonist who must overcome many challenges, while the stakes get higher and higher (Campbell, Citation2008; Vogler, Citation2020; Weiland, Citation2016a). In other words, in many stories, the protagonist displays perseverance – which is being hardworking and finishing what one has started, despite the challenges that arise (Peterson & Seligman, Citation2004). In our study, children indicated to admire this, and one girl even said it inspired her to also never give up. That witnessing perseverance can be inspiring builds upon the previously found Batman effect, indicating that pretending to be a hero was related to improved perseverance among young children (White et al., Citation2017). It is also in line with findings from a qualitative study among young adults who indicated to appreciate perseverance and the importance of keeping faith in film stories (Oliver & Hartmann, Citation2010). Given that perseverance is a character strength of many protagonists, makes it important to dive deeper into this inspiring effect and to find out whether this is prevalent among more children. All in all, we hope that in future studies scientific knowledge will be combined with knowledge on storytelling to better understand how exactly stories can be meaningful.

A Developmental Perspective on Being Moved by Moral Beauty

The present findings expand upon previous knowledge (Fiske, Citation2020; Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016) by demonstrating that being “moved by love” upon witnessing moral beauty starts to emerge around the age of 8 years old. The findings of this study indicated that for experiencing this, it is important that children can experience mixed emotions and that they fully comprehend the motivations and the behavior of the character. An important next step is to further illuminate the effects of the emotion “moved by love” among children and shed light on whether they, just as adults, experience all physiological and psychological reactions that can come along with this experience and whether they are also more likely to act with compassion, kindness, and love (Fiske, Citation2020; Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). It would be intriguing to approach this from a social neuroscience perspective and include neuroimaging methods. This can help to distinguish between feelings of moral goodness and moral beauty (Cheng et al., Citation2020), which was difficult in the present study.

The findings of this study also contribute to the current state of knowledge by revealing a potentially novel way in which prosocial behavior in the media can inspire children to act prosocial. Previous work indicated that the effects of stories in the media on children’s prosocial behaviors can be explained by children modeling the desired behaviors (for meta-analyses, see Coyne et al., Citation2018; Mares & Woodard, Citation2005). However, being moved by moral beauty can lead to prosocial behaviors other than the act of beauty that was witnessed (Pohling & Diessner, Citation2016). Now that our findings demonstrated that children could be moved upon witnessing moral beauty, it is plausible that the effects of prosocial behavior in the media on children’s prosocial behavior cannot be reduced to observational learning or modeling alone. In sum, our findings indicate that not only adults (Raney et al., Citation2020; Vorderer & Klimmt, Citation2021), but also children can have profound meaningful media experiences.

Strengths, Caveats, and More Avenues for Future Research

The strengths of this study are the design in which children were directly involved and the rich data obtained from the interviews with duos. Nonetheless, there are important points to keep in mind when interpreting the findings. The most important caveat of this study is that due to its qualitative design – with plenty of room to give the children a voice – no inferences can be drawn about the prevalence of the observed findings that go beyond the sample. Future research with a quantitative design is warranted to shed light on this. Another caveat of this study is that most participating children were White and that children of affluent and highly educated parents were slightly overrepresented. Further, this study was based on only one film. Although other films were discussed in passing, these were not as extensively discussed as Inside Out. It is important to examine our research question with other films and children with various backgrounds. Probably more ways in which stories can be meaningful will be distinguished. Finally, it would be good to examine to what extent children’s personality characteristics such as empathy, curiosity, and openness to experience, play a role in how children are drawn into a story world and how they experience aesthetic emotions. Based on our observations we feel that these are important characteristics to further investigate (see also Dubourg & Baumard, Citation2021).

Practical Implications

For Filmmakers

We hope that our findings can inspire filmmakers to create more stories that can help children to acquire meaningful insights about life. In doing so, we would like to encourage filmmakers to do extensive research and to dare to be emotionally vulnerable, just like Pete Docter and his team (see Anwar, Citation2015; Gross, Citation2015; Keltner & Ekman, Citation2015; Tucker, Citation2017). Moreover, we hope that many more acts of moral beauty will be portrayed. The latest findings from the Center for Scholars & Storytellers indicated that films with such acts are also found to make more money at the box office (Taylor & Uhls, Citation2023).

For Parents

Given that parents can support children in their plot-story construction, our findings are also important for them. Just as with storybooks for young children (Brownell et al., Citation2013; Mar, Citation2018), we would like to encourage parents to discuss films with their children and to ask open-ended questions that encourage them to understand the emotions and behaviors of the characters. Open-ended questions are also helpful in coming to understand what is challenging for children and what they experienced as beautiful. Appropriate films to consider are obviously Inside Out, but also other films with critical acclaim (Oliver et al., Citation2014).

Key Take-Aways

The findings of the present study indicate that one of children’s favorite activities – immersing themselves in stories – can be very meaningful. With stories, children can expand their circle of empathy, feel the emotion “moved by love” upon witnessing moral beauty, acquire novel truths about life, and become inspired to never give up. Altogether, stories can be an accelerated way of gaining life experience and wisdom.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Open Materials. The materials are openly accessible at https://osf.io/5gkvu/?view_only=367b869aed284b36b35be01fe9cc0792.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants for the beautiful and fun interviews. We are also grateful for Sanne Zwart and Nina van Zanten helping us with interviewing and transcribing. Finally, Rebecca would like to thank her children Mats & Fynn for the meaningful conversations about their favorite films, which sparked the idea for this study.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anwar, Y. (2015). How the GGSC helped turn Pixar “Inside Out“. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_ggsc_turned_pixar_inside_out

- Aristotle. ( Translated in 2013). Poetics (A. Kenny Trans.). Oxford University Press. Original work published 335 B.C.E. https://doi.org/10.1093/oseo/instance.00258601

- Bartsch, A., & Hartmann, T. (2017). The role of cognitive and affective challenge in entertainment experience. Communication Research, 44(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214565921

- Bordwell, D., Thompson, K., & Smith, J. (2019). Film art: An introduction (12th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Bozdech, B. (2015). Inside Out. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/movie-reviews/inside-out

- Brownell, C. A., Svetlova, M., Anderson, R., Nichols, S. R., & Drummond, J. (2013). Socialization of early prosocial behavior: Parents’ talk about emotions is associated with sharing and helping in toddlers. Infancy, 18(1), 91–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7078.2012.00125.x

- Campbell, J. (2008). The hero with a thousand faces. New World Library.

- Cheng, Q., Cui, X., Lin, J., Weng, X., & Mo, L. (2020). Neural correlates of moral goodness and moral beauty judgments. Brain Research, 1726, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2019.146534

- Chun Tie, Y., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Medicine, 7, 2050312118822927. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118822927

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Coyne, S. M., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Fraser, A. M., Fellows, K., & Day, R. D. (2014). “Media time = family time“: Positive media use in families with adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 29(5), 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558414538316

- Coyne, S. M., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Holmgren, H. G., Davis, E. J., Collier, K. M., Memmott-Elison, M. K., & Hawkins, A. J. (2018). A meta-analysis of prosocial media on prosocial behavior, aggression, and empathic concern: A multidimensional approach. Developmental Psychology, 54(2), 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000412

- Crone, E. A., & Dahl, R. E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(9), 636–650. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3313

- Curtin, C. (2001). Eliciting children’s voices in qualitative research. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55(3), 295–302. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.55.3.295

- Dahl, R. E., Allen, N. B., Wilbrecht, L., & Ballonoff Suleiman, A. (2018). Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature, 554(7693), 441–450. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25770

- de Leeuw, R. N. H., van Woudenberg, T. J., Green, K. H., Sweijen, S. W., van de Groep, S., Kleemans, M., Sanne, L., Tamboer, S. L., & Crone, E. A. (2022). Moral beauty during the COVID-19 pandemic: Prosocial behavior among adolescents and the inspiring role of the media. Communication Research, 50(2), 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502221112804

- De Mulder, H. N. M., Hakemulder, F., Klaassen, F., Junge, C. M. M., Hoijtink, H., & van Berkum, J. J. A. (2022). Figuring out what they feel: Exposure to eudaimonic narrative fiction is related to mentalizing ability. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 16(2), 242–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000428

- Diessner, R., Schuerman, L., Smith, A., Marker, K., Wilson, A., & Wilson, K. (2016). Cognitive-developmental education based on stages of understanding experiences of beauty. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 50(3), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.5406/jaesteduc.50.3.0027

- Docter, P., & del Carmen, R. (Directors). (2015). Inside Out [film]. Pixar Animation Studios.

- Dubourg, E., & Baumard, N. (2021). Why imaginary worlds? The psychological foundations and cultural evolution of fictions with imaginary worlds. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 45, 1–52. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X21000923

- Englander, Z. A., Haidt, J., & Morris, J. P. (2012). Neural basis of moral elevation demonstrated through inter-subject synchronization of cortical activity during free-viewing. PloS one, 7, e39384. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039384

- Fiske, A. P. (2020). Kama muta: Discovering the connecting emotion. Routlegde. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367220952

- Gross, T. (2015). It’s all in your head: Director Pete Docter gets emotional in “Inside Out“. https://www.npr.org/2015/06/10/413273007/its-all-in-your-head-director-pete-docter-gets-emotional-in-inside-out?t=1566379288944

- Heroes Wiki. (2015). Bing Bong. https://hero.fandom.com/wiki/Bing_Bong

- IMBd. (2016). Inside Out. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2096673/awards?ref_=tt_awd

- Imuta, K., Henry, J. D., Slaughter, V., Selcuk, B., & Ruffman, T. (2016). Theory of mind and prosocial behavior in childhood: A meta-analytic review. Developmental Psychology, 52(8), 1192–1205. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000140

- Janicke, S. H., & Oliver, M. B. (2017). The relationship between elevation, connectedness, and compassionate love in meaningful films. Journal of Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 6(3), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000105

- Keltner, D. (2023). Awe: The new science of everyday wonder and how it can transform your live. Penguin Press.

- Keltner, D., & Ekman, P. (2015). The science of “Inside out”. New York Times, 3.

- Kirk, S. (2007). Methodological and ethical issues in conducting qualitative research with children and young people: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(7), 1250–1260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.08.015

- Larsen, J. T., To, Y. M., & Fireman, G. (2007). Children’s understanding and experience of mixed emotions. Psychological Science, 18(2), 186–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01870.x

- Mar, R. A. (2018). Stories and the promotion of social cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(4), 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417749654

- Mares, M., & Woodard, E. (2005). Positive effects of television on children’s social interactions: A meta-analysis. Media Psychology, 7(3), 301–322. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0703_4

- Menninghaus, W., Wagner, V., Wassiliwizky, E., Schindler, I., Hanich, J., Jacobsen, T., & Koelsch, S. (2019). What are aesthetic emotions? Psychological Review, 126(2), 171–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000135

- Nashawaty, C. (2015). “Inside Out“: EW review. https://ew.com/article/2015/06/16/inside-out-ew-review/

- Oliver, M. B., Ash, E., Woolley, J. K., Shade, D. D., & Kim, K. (2014). Entertainment we watch and entertainment we appreciate: Patterns of motion picture consumption and acclaim over three decades. Mass Communication and Society, 17(6), 853–873. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2013.872277

- Oliver, M. B., & Bartsch, A. (2010). Appreciation as audience response: Exploring entertainment gratifications beyond hedonism. Human Communication Research, 36(1), 53–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01368.x

- Oliver, M. B., & Hartmann, T. (2010). Exploring the role of meaningful experiences in users’ appreciation of “good movies“. Projections, 4(2), 128–150. https://doi.org/10.3167/proj.2010.040208

- Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2009). Character strengths: Research and practice. Journal of College and Character, 10(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2202/1940-1639.1042

- Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. SAGE Publications.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

- Pinker, S. (2011). The better angels of our nature. Penguin Books.

- Pohling, R., & Diessner, R. (2016). Moral elevation and moral beauty: A review of the empirical literature. Review of General Psychology, 20(4), 412–425. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000089

- Raney, A. A., Janicke-Bowles, S. H., Oliver, M. B., & Dale, K. R. (2020). Introduction to positive media psychology. Routledge.

- Rideout, V., Peebles, A., Mann, S., & Robb, M. B. (2022). Common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens. Common Sense.

- Rivas-Lara, S., Pham, B., Baten, J., Meyers, A., & Uhls, Y. T. (2022). CSS teens & screens 2022 #authenticity. Center for Scholars & Storytellers.

- Rotten Tomatoes.(2021). Top 100 Animation Movies. https://www.rottentomatoes.com/top/bestofrt/top_100_animation_movies/

- Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2012). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Sanders, A. J., Felt, L., Wing, K., & Uhls, Y. T. (2019). The power of storytelling: Media and positive character development. Center for Scholars & Storytellers.

- Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(3), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

- Schindler, I., Hosoya, G., Menninghaus, W., Beermann, U., Wagner, V., Eid, M., Scherer, K., & Kret, M. E. (2017). Measuring aesthetic emotions: A review of the literature and a new assessment tool. PLoS ONE, 12(6), 0178899. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178899

- Silverman, D. (2020). Interpreting qualitative data (6th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Singer, P. (2011). The expanding circle: Ethics, evolution, and moral progress. Princeton University Press.

- Taylor, L. B., & Uhls, Y. T. (2023). The good guys: How character strengths drive kids’ entertainment wins. Center for Scholars & Storytellers.

- Tucker, M. (2017). Telling a story from the Inside out [video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ulm7bcB2xvY

- VERBI Software. (2022). MAXQDA 2022 [computer software].

- Vogler, C. (2020). The writer’s journey: Mythic structure for writers. Michael Wiese Productions.

- Vorderer, P., & Klimmt, C. (Eds.). (2021). The oxford handbook of entertainment theory. Oxford University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. In M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.), Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (pp. 86). Harvard University Press.

- Weiland, K. M. (2016a). Creating character arcs: The masterful author’s guide to uniting story structure, plot, and character development. PenForASword Publishing.

- Weiland, K. M. (2016b). Inside Out. https://www.helpingwritersbecomeauthors.com/movie-storystructure/inside-out/

- Weimer, A. A., Rice Warnell, K., Ettekal, I., Cartwright, K. B., Guajardo, N. R., & Liew, J. (2021). Correlates and antecedents of theory of mind development during middle childhood and adolescence: An integrated model. Developmental Review, 59, 100945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2020.100945

- White, R. E., Prager, E. O., Schaefer, C., Kross, E., Duckworth, A. L., & Carlson, S. M. (2017). The “Batman effect“: Improving perseverance in young children. Child Development, 88(5), 1563–1571. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12695

- Woodgate, R. L., Tennent, P., & Zurba, M. (2017). Navigating ethical challenges in qualitative research with children and youth through sustaining mindful presence. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917696743

- Zajdel, R. T., Myerow Bloom, J., Fireman, G., & Larsen, J. T. (2013). Children’s understanding and experience of mixed emotions: The roles of age, gender, and empathy. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 174(5), 582–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2012.732125