ABSTRACT

Media psychologists commonly study how narrative elements (e.g. characters) influence entertainment and perceptions. Research on the sequencing and structure of these elements (i.e. metanarrative; the shape of the story) is less common. In both areas, morality tends to ground theorizing (e.g. disposition theory). To extend knowledge in these domains, we conceptualize and observe the effects of side-taking (i.e. choosing a side during conflict), a core concept in narratives and moral psychology. Dynamic coordination theory explains that side-taking is fundamental to morality because it signals moral judgment/condemnation. In a preregistered experiment (N = 577), we observed how the direction (i.e. siding with/against the protagonists or taking no side) and timing of side-taking (i.e. early, middle, or late in the story) influenced variables at multiple levels of analysis (i.e. micro-to-macro). Although timing did not produce effects, we found robust evidence that the direction of side-taking affected variables at all levels of analysis.

A robust body of research explains how story events and character behaviors influence narrative appeal (e.g., Eden et al., Citation2017, Hamby et al., Citation2020, Raney, Citation2005). A notable portion of this work grounds theorizing in morality (e.g., Eden et al., Citation2015, Krakowiak & Tsay‐Vogel, Citation2015, Krcmar, Citation2013), demonstrating that people like moral characters and enjoy stories when these characters receive good fortunes (see Zillmann & Bryant, Citation1975). Relevant to the current study, one branch of this research investigates how narrative structural elements such as individual character behaviors (e.g., Matthews & Bonus, Citation2021) and the trajectory of a character’s moral development (e.g., Grizzard, Matthews, et al., Citation2021, Kleemans et al., Citation2017) produce distinct effects. A burgeoning topic on narrative structural elements concerns the qualities of the social relationship network among characters. This work shows that the relational links in character networks can influence perceptions of morality independent of character behavior (Grizzard et al., Citation2020). Additionally, moral conflict among characters creates relational dependencies and establishes expectations in ways that give narratives coherence (Hopp et al., Citation2020).

We contend that existing moral psychological theory can refine predictions related to the qualities of narratives by explicating the processes involved during side-taking (i.e., choosing sides during conflict). Specifically, dynamic coordination theory (DCT) conceptualizes side-taking as fundamental to human morality (DeScioli & Kurzban, Citation2013, Kurzban et al., Citation2012). We argue that DCT is a cogent framework for extending knowledge in this area because side-taking signals moral allegiance/condemnation and structures moral conflict discretely. Given side-taking’s moral grounding and its commonality in narratives (e.g., one character betraying another), we tested the effects of side-taking by manipulating its direction (a character siding with/against protagonists) and timing (early vs. late side-taking) in a short story presented as an animated book. Below, we review relevant work on narrative structural elements and advance two key conceptualizations: side-taking in narratives and how the timing of side-taking influences the overall shape of the story (i.e., the metanarrative structure).

Narrative Structural Elements

A narrative is a message that describes a series of related events that includes characters, temporal progression, and narration (see Grizzard et al., Citation2018). Events (i.e., what happens in the narrative), temporal progression (i.e., the order in which the events are relayed to the audience), characters (i.e., the beings that populate the story), and narration (i.e., the manner in which the story is communicated to the audience) are the elements that constitute narrative. A message must possess these elements to be classified as a narrative. Narrative structural elements refer to the qualities of (e.g., first-person narration) and/or relationships (e.g., character networks) among/between various narrative elements. Variance in narrative structural elements can make specific outcomes more/less likely. Existing theories demonstrate the existence and influence of such elements at the micro, mezzo, and macro levels of analysis. Specifically, at the micro (i.e., event) level, disposition theories such as affective disposition theory (ADT; e.g., Zillmann & Cantor, Citation1976) focus on how behaviors yield dispositions (i.e., inference about one’s character).

At the mezzo level, the relational interdependence among characters (i.e., who is aligned with who) influences how people perceive characters (Grizzard et al., Citation2020). Specifically, audiences can generate/update dispositions toward characters via comparisons to other characters (e.g., disliking an antagonist’s ally due to their kinship). Additionally, the relative difference in morality between characters alters judgments (Grizzard, Matthews, et al., Citation2021). For example, people judge a character’s immoral behaviors with greater leniency when a more immoral character is present rather than absent.

Finally, at the macro (i.e., story) level, two areas of study warrant discussion. The first area relates to story resolutions. Grounded in ADT, the moral sanction theory of delight and repugnance (MSTDR; Zillmann, Citation2000) explains how positive dispositions toward a character foster hopes for their fortune and negative dispositions foster hopes for misfortune. People enjoy stories that resolve these anticipatory emotions in expected ways and dislike stories that subvert these expectations (Weber et al., Citation2008).

Similarly, the integrated model of enjoyment (Raney, Citation2005) considers justice sequences in drama, explaining how the magnitude of injustice, the magnitude of retribution, and audiences’ empathetic feelings toward the victim and the offender coalesce to predict entertainment outcomes. Research demonstrates that the context of moral injustice influences the latitude of acceptable retribution (e.g., a severe crime permits severe punishments; Raney & Bryant, Citation2002). Furthermore, relative to under/overretribution, people like equitable retribution more and process it more quickly (Grizzard et al., Citation2021).

The second macro level area is character development. Research by Kleemans et al. (Citation2017)—extending Shafer and Raney (Citation2012)—found that character development influences character liking and narrative enjoyment. The authors argue that narratives often present characters with opportunities to grow. These moments allow characters to seize these opportunities and better themselves or ignore them and maintain their problematic behaviors. Witnessing a character deliberate over a moral dilemma and either resolve it positively or negatively alters viewers’ evaluations of characters, the characters’ behaviors, and the narrative itself.

Although discrete in terms of analytical level, narrative elements are interdependent due to their nested structure. Micro-level elements are nested within mezzo-level elements. Mezzo-level elements are nested within macro-level elements. For example, individual character behaviors are micro elements that can facilitate disposition formation. Formed dispositions carry over from scene to scene are mezzo-level elements that shape viewer interpretations of future events. The combined plot and the gist of the narrative occurs at the macro-level. Put differently, the micro- and mezzo-level narrative structural elements help establish the magnitude and circumstances that surround a viewer’s ultimate evaluation of a narrative.

Evidence of such multi-level dependencies abounds. For example, audiences are more sensitive to the unanticipated actions committed by heroic characters than villainous characters (Bonus et al., Citation2019), especially when the action resolves the story (Matthews & Bonus, Citation2021). Therefore, smaller narrative occurrences and excitation at lower levels compound upon one another throughout a story to lead to emergent narrative responses at higher structural levels. In other words, there is additive residual excitation occurring at each level that contributes to audiences’ responses at higher levels.

These examples highlight ways in which narrative structural elements influence reactions to events, perceptions of characters, and ultimate entertainment outcomes. To add to this body of work, we investigated a novel narrative structural element in two ways. First, similar to existing work, we consider the influence of an individual structural element: narrative side-taking (e.g., side-taking with/against protagonists). Second, we investigated metanarrative structure (see Raney, Citation2013) – a holistic, macro variable grounded in narrative conflict and the chronological ordering of events. By considering not only a new element (i.e., side-taking), but also its chronological placement in the story, we sought to learn how the timing of isolated structural elements shapes media effects. Below, we conceptualize both central concepts and their potential interactions.

Side-Taking Directionality and Its Importance for Dynamic Coordination Theory

Narratives commonly rely upon familiar themes (i.e., metastories) such as good versus evil to give stories structure (Raney, Citation2013). In most stories, protagonists face opportunities and obstacles while pursuing goals. Often, this involves character conflict (Hopp et al., Citation2020). Over time, other characters can decide to aid, impede, or ignore the protagonist’s goals. Therefore, conflict among characters and how other characters organize themselves around such conflict helps determine narrative structure (Hopp et al., Citation2020). We contend that these discrete side-taking decisions are narrative elements that contribute to the shape of stories by organizing the configuration of the character network over time. Such organization can build suspense, generate expectations/anticipatory emotions, and define the relationship structure among characters.

For example, assume a protagonist becomes lost in hostile territory and needs directions to the closest friendly town. The protagonist finds a stranger and asks for help. The stranger requests the protagonist’s weapon in return for help. The protagonist provides the weapon, the stranger provides directions, and then the stranger returns the weapon, saying they had to make sure the protagonist was trustworthy. In this example, the stranger’s demand is unsettling because the stranger’s moral character is unknown. Therefore, suspense persists until the stranger provides directions and returns the weapon, reconciling the anticipatory emotions. Side-taking decisions, as highlighted in this example, suggest implications for processes outlined in theories such as ADT. However, media researchers have yet to conceptualize side-taking formally or observe its effects systematically. To this end, our central goal was to build knowledge theoretically and empirically on side-taking, as it relates to narrative structure.

According to dynamic coordination theory (DCT; DeScioli & Kurzban, Citation2013), side-taking is a key component of human morality, given its connection to moral condemnation. Specifically, the cognitive mechanisms that drive moral condemnation (e.g., assessing the wrongness of actions) help people choose sides during conflict. Generally, conflict is costly to individuals, especially when they are outnumbered. As a result, those in conflict try to recruit bystanders to gain a numerical advantage. Bystanders try to reduce the odds of being on the losing side by coordinating their side-taking decisions (i.e., third-party coordination).

DCT focuses on three primary third-party coordination strategies. The first is bandwagoning, which is when bystanders side with the majority or most powerful (e.g., a small nation siding with a superpower). The second is alliance-building. This is when bystanders side take based on preexisting loyalties (e.g., friends banding together). The third is wrongness, which is when bystanders side against those who are the most morally wrong (i.e., moral condemnation). DeScioli and Kurzban (Citation2013) contend that evolution favored those whose moral intuitions motivated them to side-take based on wrongness because it is impartial. In other words, it does not reinforce existing power structures, unlike bandwagoning, nor does it lead to escalation/discoordination, unlike alliance-building. However, bystanders consider existing loyalties to individuals/groups, the welfare of those involved, possible reactions of others, and more in addition to wrongness. Therefore, the outcomes of side-taking can counter wrongness judgments. Accordingly, our study leverages the structure and combinations of these side-taking prototypes. Specifically, we observe how people react to a somewhat neutral character that possesses alliances with antagonists who ultimately (a) sides with protagonists, (b) sides with antagonists, or (c) remains ambiguously neutral.

Regardless of the coordination strategy, DCT conceptualizes that the act of side-taking serves as a signal that communicates moral judgment/condemnation. Said differently, side-taking indicates who an actor thinks is morally superior and it aligns/organizes the actor in the narrative (i.e., they transition from a bystander to an actor in the conflict). Subsequently, each act of side-taking alters the balance of power. According to DCT, each time a bystander side-takes, it escalates the scale of conflict because the ultimate outcome affects more people. In other words, side-taking can amplify the conflict between two actors to involve groups, societies, nations, or – in the case of fiction – worlds. Therefore, side-taking adds weight to conflict that can make it more impactful/meaningful. All considered, because side-taking signals moral judgment, transforms bystanders into actors, and alters the relational configuration of conflict, we contend that investigating side-taking as a narrative structural element would yield fruitful discoveries.

Importantly, relative to other concepts entangled with side-taking (e.g., identification & loyalty), side-taking always signals relational information discretely (i.e., in concrete isolated instance). By comparison, other concepts common in this research area tend to develop over time (e.g., from scene to scene). Furthermore, unlike adjacent concepts, each act of side-taking alters a narrative’s social network configuration (Hopp et al., Citation2020) and ultimately the shape of the resulting narrative and the location of its conflict in relation to the other characters. As a result, we contend that side-taking offers a cogent avenue for empirical observation, especially for those interested in the effects of narrative structure and social relationships among characters on media reception.

Although existing work in media psychology discusses side-taking (see Raney, Citation2011), a formal conceptualization does not exist. Therefore, we conceptualize side-taking in media as when one character/group signals support or opposition to an existing character/group. In this conceptualization, the audience must witness the signal, but it is not necessary for other characters to witness the signal (e.g., learning about a hidden intention to betray an ally). Side-taking in narrative is relative to a target character or group. Accordingly, side-taking is represented by three actions: a character/group (1) siding with, (2) siding against, or (3) remaining/becoming neutral toward a target character/group. These three versions of side-taking become focal comparisons in our study.

Because side-taking signals moral judgment, alters character status, and influences conflict, we contend that it produces effects via two mechanisms: informational and relational. Informationally, side-taking is a discrete behavior that signals a character’s moral judgment and centralizes them in a conflict. The addition of actors (i.e., transitioning from a bystander) also convolutes the conflict and increases its scope. Together, these characteristics add to narrative complexity in two ways. First, additional actors complicate conflict (e.g. differing opinions, existing ties, skills, subterfuge). Second, the larger scope makes conflict more impactful/meaningful by affecting a greater number of actors (i.e., squabbles become battles – battles become wars). Said differently, the added scope complicates an otherwise more simplistic conflict, given that the resulting outcomes affect more characters’ fates in unpredictable ways.

Relationally, side-taking alters how people feel about characters. Audiences emotionally side-take with characters who share their values, beliefs, and morals (Raney, Citation2011). People grant these characters moral amnesty and hope they enjoy fortune. When characters side-take, they organize themselves in terms of their moral configuration relative to other characters. In doing so, they motivate audiences to either root for or against them. We anticipated that side-taking’s effects via informational and relational mechanisms would alter how people respond to narratives. Accordingly, we developed predictions that triangulate the influence of side-taking across analytical levels.

At the macro level, we predicted that the information that side-taking adds to the narrative would cause people to evaluate a story with side-taking as more complex (H1) and appreciable (H2) than one without side-taking. Additionally, because side-taking should influence people’s relationship with a character, it generates hopes for (mis)fortune that can resolve satisfactorily (i.e., protagonists and allies are rewarded, antagonists and allies are punished). As a result, we predicted that the presence of side-taking would be more enjoyable (H3) than its absence.

At the mezzo level, we focused on dispositions toward the side-taking actor from a relational perspective and person perceptions toward the actor from an informational perspective. Informed by DCT, we anticipated that people would perceive the act of side-taking as morally relevant (i.e., not amoral) – ultimately influencing dispositions and perceptions toward the side-taking actor. Additionally, given the higher diagnosticity of immoral behaviors relative to moral behaviors (Critcher & Dunning, Citation2014, Matthews & Bonus, Citation2021), compared to no side-taking, we predicted that there would be larger differences in dispositions toward the side-taking actor when they side against the protagonists than when they side with the antagonist (H4). In other words, when compared to no-side taking behavior, side-taking against the protagonist will have a stronger effect on dispositions compared to side-taking with the protagonist. Additionally, the act of taking a side should make the character more dynamic and central to the story, rather than flat and peripheral. Given this, we predicted that people would perceive the side-taking actor as more complex (H5) and competent (H6) when side-taking was present rather than absent.

Finally, at the micro level, we focused on how people responded to the act of side-taking by focusing on expectancy violations from a relational perspective. In social contexts, people have enduring expectations about the behaviors of others. Unmet expectations trigger expectancy violations that can vary in terms of their valence, expectedness, and importance to the relationship (Burgoon, Citation2015). Because audiences tend to emotionally side-take with protagonists (Raney, Citation2011), we anticipated that audiences would expect other characters to side with the protagonists. Additionally, immoral actions are more diagnostic than moral actions (Critcher & Dunning, Citation2014, Matthews & Bonus, Citation2021). Accordingly, we predicted that expectancy violations would be higher when a side-taking actor sided against the protagonists compared to siding with the protagonists (H7). However, because we anticipated differences between siding-with and siding-against the protagonists, it was unclear how both conditions would compare to the absence of side-taking. Given that any form of side-taking would alter the nature/importance of relationships relative to the protagonists, we asked if expectancy violations would be higher when side-taking was present, compared to when it was absent (RQ1).

Side-Taking Timing & Metanarrative

Beyond the mere presence or absence of narrative elements, existing research observes effects resulting from the timing of elements at both the intra- and inter-narrative level. Intra-narrative investigations examine how time compounds the influence of narrative elements within a single narrative (e.g., how time spent with a character affects liking). This work tends to investigate how the frequency of an element compounds effects. For example, dispositions toward characters tend to polarize over time as people witness good characters behaving morally and bad characters behaving immorally (e.g., Tamborini et al., Citation2010). Work by Sanders and Tsay-Vogel (Citation2016) demonstrated that repeated exposure to a narrative increased identification with its characters and moral disengagement toward the actions of the central protagonist (i.e., the most moral character). Such repeated exposure is theorized to recreate familiar emotional flows (i.e., shifts in affective states) that help reinforce certain beliefs and attitudes (Nabi & Green, Citation2015).

Unlike intra-narrative effects that tend to rely on frequency and accumulation, inter-narrative work focuses on how distinct temporal patterns of narrative elements produce consistent effects across multiple narratives (e.g., how entertaining are rags-to-riches stories relative to court room dramas). In other words, inter-narrative work considers familiar sequences of narrative elements. Although stories vary greatly, many follow similar paths (i.e., they use recognizable sequences; Reagan et al., Citation2016). These paths are limited and identified as the general metanarrative structure.

Similar to existing articulations (Kurt Vonnegut on the Shapes of Stories, Citation2010; Reagan et al., Citation2016), we define metanarratives as recognizable, schematic narrative forms, or the formulaic “shapes” of stories. Our conceptualization aligns with Grizzard and colleagues’ (Citation2021) usage that describes metanarrative as narrative schema, drawing on the description by Raney (Citation2013, p. 166). Research in this domain has produced fruitful insights. For example, research on the expected structure of justice sequences demonstrates that audiences have a broad but bounded level of retribution that they think is appropriate following injustice (Grizzard et al., Citation2021, Raney, Citation2005, Raney & Bryant, Citation2002). Other work by Weber et al. (Citation2008) on disposition vectors focuses on the timely denial/fulfillment of anticipatory emotions (i.e., character fortune). They found that Nielsen ratings for individual shows increased when good behavior was rewarded and bad behavior was punished. Additional work by Grizzard’s et al. (Citation2021) on narrative arc/trajectory and character interdependence focuses on how the relative moral differences between characters affect the perceptions of characters as they descend into immorality (i.e., Vonnegut’s from-bad-to-worse story shape). Specifically, people judge a character’s immoral behaviors with greater leniency when a more immoral character is present rather than absent and this tendency increases over time.

Together, these studies demonstrate that the sequencing of narrative elements produces divergent media effects. In line with existing work, our study focused on how the timing and characteristics of a single element – side-taking – influenced effects by altering the shape of the story. We reasoned that the timing of side-taking mattered because the act of side-taking is a time-influenced signal. According to dynamic coordination theory (DCT; DeScioli & Kurzban, Citation2013), people attend to ongoing third-party coordination because the winning side ultimately condemns the losing side with punishment. Given the potential of costly losses, people gossip and negotiate during coordination to inform the direction and timing of their side-taking.

For example, if people determine that the basis of a conflict is central to their identity, they side-take early – perhaps also condemning the opposition publicly (e.g., attending a protest). Such resolute side-taking can rally support but is risky because the conflict’s outcome is unclear. By contrast, late side-taking is safer because outcomes become predicable (e.g., announcing your vote after learning your candidate will likely win). Given these risks, people tend to remain impartial (or fake impartiality) until they feel a decision is safe. However, those who have already taken a side often perceive (prolonged) indecision as concealed opposition, which harms resulting trust and cooperation (Silver & Shaw, Citation2022).

In sum, the time-dependent nature of side-taking possesses conceptual overlap with metanarrative structure. Given this, we aimed to add knowledge about metanarrative by investigating how side-taking behaves as a mechanism that defines narrative shape and influences downstream entertainment outcomes. We contend that the time-dependent nature of side-taking influences how people perceive the act of side-taking, the side-taking actor, and the broader narrative. This is because timing alters the overall trajectory of the story. In other words, the timing of side-taking (and its interaction with side-taking direction) alters the configuration of the metanarrative.

Similar to the direction of side-taking, we investigated how the timing of side-taking influenced variables at multiple levels of analysis. Our broad prediction was that side-taking that occurred later in the story would increase the magnitude of some effects. This is because narrative expectations have more time to solidify. As a result, side-taking later in the story should cause more of an unexpected disruption to expectations (e.g., when a protagonist’s longtime ally betrays them during a story’s climax). Furthermore, we assumed that the ongoing uncertainty surrounding side-taking builds suspense. This added suspense should augment a story’s ability to elicit complex emotions. Accordingly, we predicted that side-taking that happens later in the story would result in greater expectancy violations (H8) and appreciation (H9). Beyond these predictions, it was unclear how/if timing would affect our other targeted variables, given their minimal connections to suspense and affect. As a result, we asked how the timing of side-taking would affect enjoyment (RQ2), perceived narrative complexity (RQ3), and the side-taking actor’s perceived competence (RQ4) and complexity (RQ5).

Finally, we had one prediction about the interaction between side-taking direction and timing centered on dispositions toward the side-taking actor. Similar to real world side-taking, the characteristics of conflict in narratives are nebulous early in the story and more concrete later in the story. As a result, we anticipated that people’s moral judgments would be more acute later in story, as they would have a better understanding of conflict, expectations for how the conflict should resolve, and how others in the story should interpret the conflict. Given this, we predicted that differences in dispositions would be greater when side-taking occurred later in the story compared to earlier (H10). Beyond this, the novel combination of side-taking direction and timing seemed capable of producing unanticipated outcomes. Accordingly, we proposed a general research question asking how the interaction of side-taking direction and timing would affect our dependent variables (RQ6).

Method

Nature of the Study

This study is part of a series of ongoing preregistered studies investigating drama over time. Broadly, the series observes how (1) the solidification of narrative information, (2) the (un)expectedness of narrative events, (3) the relative differences among a narrative’s main characters, and (4) time influenced key variables related to media entertainment and character reception. Although all the studies in the series focus on time, this study focused on the solidification of narrative information by investigating side-taking. Accordingly, the preregistration (tinyurl.com/DOTbetrayal1) details both this study and the broader series of studies. Notably, we do not discuss results surrounding emotional flow, as we reserved these data for a subsequent multi-study manuscript on emotional flow.

Experimental Design and Stimuli

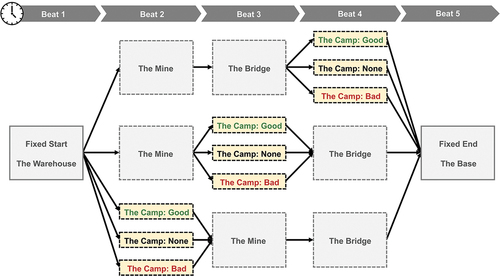

We used a 3 (direction) x 3 (timing) x 2 (order) between-subjects experimental design (). We manipulated the direction of side-taking by having an actor side with the protagonists (i.e., side good), side against the protagonists (i.e., side bad), or remain neutral (i.e., none or no side). We manipulated timing by ordering the presentation of the story beat containing the side-taking manipulation (i.e., the camp story beat) at different times relative to the other story beats (i.e., in beat 2, 3, or 4 out of 5 total beats). Early side-taking occurred in beat 2, middle side-taking occurred in beat 3, and late side-taking occurred in beat 4. We manipulated order by swapping the order of the story beats not containing the side-taking manipulation (e.g., the mine then the bridge vs the bridge then the mine; this is not visualized in ).

Figure 1. Visualization of the experimental design. Fixed story beats have a solid outline. Modular story beats have a dashed outline. The camp story beat contained the side-taking manipulation. We randomly assigned participants to a single arrow path, through which they progressed sequentially (i.e., moving left-to-right).

Our stimuli (see online supplement at tinyurl.com/DOTbetrayal2) was an original short story presented as an animated book featuring images, sounds, and music. The 12-minute story centered on two protagonists escaping enemy territory during a fictional war. In the first story beat (i.e., the warehouse) the protagonists encounter an enemy soldier who they capture as a prisoner. We designed the enemy soldier to be less threatening and morally neutral by making him an adolescent (age 15), forcefully drafted, pitiful (e.g., starving), and therefore dependent upon the protagonists. The enemy soldier was the side-taking actor in our story who either sided with the protagonists, against the protagonists, or remained neutral.

The story always began in the warehouse and ended at the base. The three middle beats were modular, meaning we randomized their order. The camp served as the climax to the story that possessed the side-taking manipulation. During this beat, the protagonists are surprised by an enemy attack. The beat concludes by the actor (1) saving the protagonists’ lives by killing the attacking enemy (i.e., the actor betrays his comrades/the antagonists to save the protagonists), (2) joining the attackers and attempting to kill the protagonists (i.e., the actor sides with his comrades/the antagonists decisively), or (3) remaining neutral by merely acting as a bystander in the conflict.

Participants and Procedure

577 out of 703 total participants recruited from MTurk (paid $2.80) completed the study and answered all attention checks correctly (nfemale = 357, nmale = 214, nnon-binary = 2; Mage = 40.7, SDage = 12.9; nWhite = 434, nBlack = 78, nAsian = 25, nNativeAmerican = 4, nPacificIslander = 2, nother = 31).

Following consent, participants watched the first story beat and responded to over time dependent variables before viewing the following story beat. This process was repeated in sequential order for each of the five story beats. Following the presentation of all five story beats, participants responded to holistic evaluations of the characters and narrative, attention checks, and then demographics.

Measures

All measures used 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) Likert-types scales.

Enjoyment and appreciation

We measured enjoyment (α = .85, M = 4.26, SD= 1.62) and appreciation (α = .85, M = 5.18, SD= 1.43) using Oliver and Bartsch’s (Citation2011) scale. Example items include, “I thought the story was fun” and “I thought the story was meaningful,” respectively.

Narrative complexity

We measured narrative complexity (Spearman-Brown Coefficient = .72, M = 5.07, SD= 1.45) using two items, “I thought the story was complex,” and “I thought the story was unpredictable.”

Expectancy violation

We measured expectancy violations to the actor’s side-taking behaviors in The Camp (Spearman-Brown Coefficient = .65, M = 4.62, SD= 1.54) using two items. The leading text was, “During ‘The Camp’ video, enemy soldiers attacked the main characters. [Summary of scene]. In this scene, I thought that [the actor’s] actions … ” The two following items were “changed my relationship with [the actor],” and “were unexpected.”

Character complexity

We measured character complexity (M = 4.86, SD= 1.63) using a single item, “[The actor] is complex.”

Character competence

We measured character competence (M = 4.58, SD= 1.57) using a single item, “[The actor] is competent.”

Disposition

We measured disposition toward the actor (Spearman-Brown Coefficient = .87, M = 4.50, SD= 1.55) using two items, “I like [the actor],” and “[The actor] is moral.”

Approbation

We measured approbation (Spearman-Brown Coefficient = .89, M = 4.22, SD= 1.73) using two items, “[The actor’s] actions were moral,” and “[The actor’s] actions were the right thing to do.”

Results

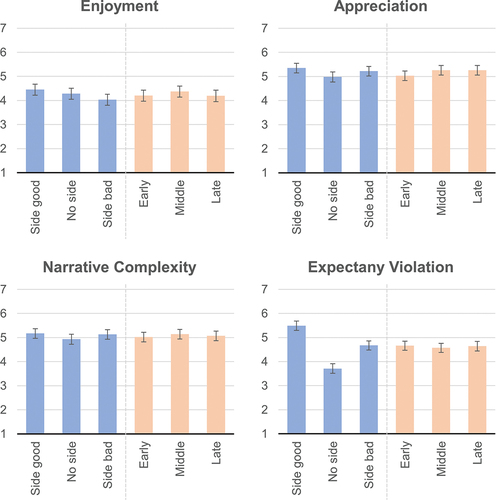

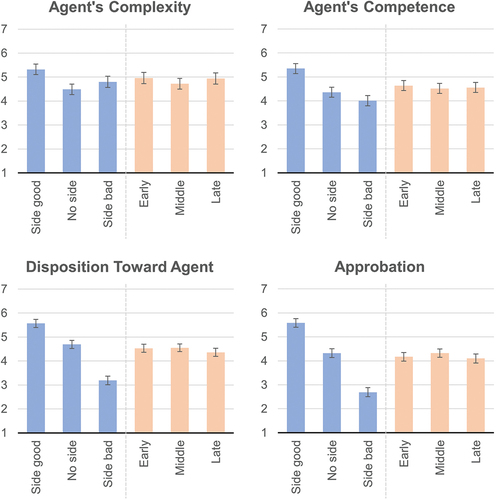

For all analyses, we used a 3 (side-taking direction) x 3 (side-taking timing) x 2 (order) ANOVA. All post-hoc analyses used Bonferroni adjustments. We summarized the analyses in and generated visualizations of the main effects in and . Supplemental tables summarize the means of the interactions (see Tables S1a-S1g at tinyurl.com/DOTbetrayal2). Overall, our data supported many of our predictions about the direction of side-taking. However, the timing of side-taking and the interaction of direction and timing did not generate data in support of our predictions, nor did these analyses detect differences among conditions.

Figure 2a. Main effects of direction and timing.

Figure 2b. Main effects of direction and timing.

Table 1. Main effects summaries. Reported means are estimated marginal means.

Table 2. Main effects summaries. Reported means are estimated marginal means.

Specifically, for side-taking direction, we found full support for our prediction that compared to no side-taking, there would be larger differences in dispositions toward the side-taking actor when they side against the protagonists than when they side with the antagonist (H4; ; ). The mean difference between no side-taking and siding with the protagonist was 0.88, d = 0.74 (95% CI: .53–.94). By comparison, the difference between no side-taking and siding with the antagonist was 1.51, d = 1.26 (95% CI: 1.04–1.48).

We found partial support for our prediction that the presence of side-taking would be more appreciable (H2; ; ) than its absence. Although siding against the protagonists was not different from no side-taking, t(559) = 1.68, p = .28, d = .17, siding with the protagonists increased appreciation relative to no side-taking, t(559) = 2.59, p = .03, d = .26.

This same pattern of partial support emerged for perceptions of the side-taking actor’s complexity (H5; ; ) and competence (H6; ; ). Specifically, complexity and competence were higher relative to no side-taking when the actor sided with the protagonists, tComplex(557) = 5.17, p < .001, d = .53, tCompetent(557) = 6.64, p < .001, d = .68. However, complexity and competence were equivalent to no side-taking when the actor sided against the protagonists, tComplex(557) = 1.90, p = .17, d = .20, tCompetent(557) = 2.29, p = .07, d = .24.

Unexpectedly, we found the data opposed our predictions for our hypothesis that expectancy violations would be higher when a side-taking actor sided against the protagonists compared to siding with the protagonists (H7; see & ). Instead, we found that expectancy violations were highest when the actor sided with the protagonists rather than against them. Despite this, our data answered RQ1 that asked if expectancy violations would be higher when side-taking was present. We found both conditions generated higher expectancy violations than no side-taking, tSideGood(559) = 12.88, p < .001, d = 1.31, tSideBad(559) = 6.90, p < .001, d = .71.

Similarly, we did not find that the presence of side-taking increased enjoyment (H3; ; ) relative to no side-taking. Instead, we found that neither side-taking condition was different from the no side-taking condition. Nevertheless, side-taking with the protagonists was rated as more enjoyable than siding against the protagonists, t(559) = 2.52, p = .04, d = .26. Therefore, the presence of side-taking was not capable of increasing enjoyment by itself. Instead, the direction of side-taking influenced overall enjoyment.

Finally, we did not find evidence supporting our predictions for narrative complexity (H1; ; ). Although we predicted that people would rate conditions featuring side-taking as more complex than conditions without side-taking, the data showed that none of the conditions were different from one another.

As described above, we did not find any evidence that the timing of side-taking influenced our dependent variables (; ). As a result, our predictions that side-taking that happened later in the story would result in greater expectancy violations (H8) and appreciation (H9) were unsupported. The results also answered our corresponding research questions that asked how the timing of side-taking would affect enjoyment (RQ2), perceived narrative complexity (RQ3), and the side-taking actors’ perceived competence (RQ4) and complexity (RQ5). In summary, the timing of side-taking did not alter these variables.

Similar to the timing of side-taking, we did not detect any interactions between side-taking direction and timing (). Given this, we did not find support for our prediction that differences in dispositions would be greater when side-taking occurred later in the story compared to earlier (H10). Moreover, we answered our general research question that asked how the interaction of side-taking direction and timing would affect our dependent variables (RQ6). Overall, the interaction of side-taking direction and timing was unable to alter any of our dependent variables.

Discussion

Existing media effects research provides evidence that narrative structural elements influence people’s perceptions and reactions to stories. Our work builds knowledge in this domain by considering the influence of side-taking, a novel structural element grounded in moral psychology’s dynamic coordination theory (DCT; DeScioli & Kurzban, Citation2013). By considering not only the nature of side-taking (i.e., direction) but also its temporal placement in a narrative, we sought to determine how side-taking functions in isolation and as a determinant of the overall shape of the story (i.e., the metanarrative structure).

Our findings provide evidence that side-taking produces effects across analytical levels. However, the direction of side-taking drove all observed effects. Unexpectedly, the timing of side-taking (and the interaction of direction and timing) did not influence outcomes. This pattern of results suggests that the presence and nature of side-taking influences media effects independent of when side-taking appears in the narrative (i.e., timing). Given this, we posit implications that parallel our levels of analysis.

At the micro level, the presence of side-taking violated expectations more than its absence. Additionally, siding with the protagonists violated expectations more than siding against the protagonists. These findings imply that mere side-taking, regardless of people’s moral evaluation of the act, generates expectancy violations. This is likely because side-taking altered the social network configuration of the story’s characters to produce valenced evaluations, and influenced the character’s relational importance in ways that may have been unexpected.

Finding that siding with the protagonists was more unexpected than siding against them opposed our prediction. This counter-intuitive finding suggests that people anticipate antagonism more than support, perhaps because such betrayal underpins drama. However, it is possible that our specific combination of side-taking strategies generated this result uniquely. Specifically, the side-taking actor was the protagonists’ prisoner of war who fought for the antagonists. Although the prisoner relied on the protagonists, the narrative context could have potentiated greater surprise resulting from the prisoner’s sympathetic change of heart (i.e., siding with the protagonists) compared to his nefarious betrayal (i.e., siding against the protagonists). Alternatively, siding with the protagonists may have generated stronger expectancy violations because the character was categorically an antagonist and participants had little reason to reclassify him prior to his side-taking (see Sanders, Citation2010). Rather than have a somewhat-neutral character “double-down” or switch sides, it may be more theoretically informative to have a pure third-party bystander join the conflict by taking a side. Future work could experiment with this and other coordination strategies to determine the generalizability of the current findings.

Considering both findings, side-taking can violate expectations about how people anticipate narratives to play out. This likely has implications for existing theory in this area such as the integrated model (Raney, Citation2002, Raney & Bryant, Citation2002) that focuses on justice sequences. In detail, the model accounts for both the restoration of justice following injustice and people’s feelings toward the perpetrator and victim. However, side-taking may entail affective shifts/reversals toward characters after they change allegiances. Victims may ultimately become perpetrators or vice versa. Such complexity is common in drama and accounting for this dynamism may improve the predictive strength of models that rely on longer-term story resolutions.

At the mezzo level, we found that siding against the protagonists affected dispositions more than siding with the protagonists. We also found that side-taking increased the side-taker’s competence and complexity. Notably, this occurred when the actor sided with the protagonists but not when they sided against the protagonists. These results have two implications. First, side-taking helps centralize bystanders by making them an agentic actor in the narrative. It is possible that the mere act of organizing a character in the character network instills the character with information that increases their complexity/depth. This suggestion implies that anything that (re)organizes a character in the character network can increase their complexity and side-taking may be one such method.

Second, finding increased complexity and competence only occurred when the actor sided with the protagonists implies that “choosing bad,” although ostensibly agentic, diminishes side-taking’s ability to signal agency. Said differently, people may ignore the agency that side-taking implies when characters function as antagonists. This corroborates the idea that people dehumanize victims/villains to reconcile their desire to see them punished (Bandura et al., Citation1996, Frazer et al., Citation2022). In this instance, an agentic antagonist was no more competent or complex than a non-agentic bystander. Although existing work shows that people tend to perceive villains as competent as heroes (Eden et al., Citation2015, Grizzard et al., Citation2018), our findings suggest that the character may have to reach a certain level of narrative centrality for people to ascribe competence. Alternatively, because the character was categorically an antagonist, participants may have perceived siding against the protagonists as schematic/cliché (see Sanders, Citation2010).

Beyond complexity and competence, finding that siding against the protagonists produced stronger effects on dispositions compared to siding with the protagonists corroborates exiting work. Specifically, Matthews and Bonus (Citation2021) found that bad behaviors cause strong shifts in dispositions toward good characters. By comparison, good behaviors cause weak shifts in dispositions toward bad characters, supporting the idea that bad behaviors are more diagnostic than good behaviors for updating dispositions (Critcher & Dunning, Citation2014). Our findings extend this work by demonstrating the same disposition updating patterns for neutral characters.

At the macro level, effects diminished. Siding with the protagonists increased appreciation relative to no side-taking. However, the presence of side-taking did not increase enjoyment relative to the absence of side-taking. Instead, siding with the protagonists was more enjoyable than siding against them. And regardless of direction, side-taking did not influence perceptions of the narrative’s complexity.

Overall, these findings suggest that side-taking produces more micro- and mezzo-level effects than macro-level effects. In hindsight, this boundary condition of side-taking is understandable, as side-taking is a small moment among many other suspenseful threats and opportunities presented in narratives. Although we anticipated that side-taking would add complexity to the character relationship network and offer more opportunities for the formation and satisfactory resolution of anticipatory emotions, it appears that single instances of side-taking do not generate effects that cascade to the highest levels of story evaluation.

However, we found small effects that suggest side-taking makes stories more appreciable and enjoyable. Considering that people appreciated the story more when the actor sided with the protagonists compared to remaining neutral, it is likely this occurred due to the strong expectancy violations we observed stirring complex emotions. Unlike appreciation, enjoyment was higher when the actor sided with the protagonists likely because the actor joined the side participants rooted for (see Raney, Citation2011), which may have been hedonically pleasing.

Together, these data suggest that siding with the protagonist benefits entertainment outcomes. According to DCT, people protect themselves from moral condemnation by siding with the group most likely to win. Commonly, protagonists win conflicts and audiences tend to side with protagonists (Raney, Citation2011). Therefore, bystanders who side with protagonists side with audiences indirectly. Audience members may enjoy and appreciate when bystanders support who the audience supports because it is vicariously satisfying.

Unlike the direction of side-taking, the timing of side-taking did not produce effects nor interactions. Broadly, we expected effects to increase in magnitude when side-taking was later in the story. We reasoned that, as stories progress, growing suspense and the solidification the narrative information potentiates stronger anticipations and subsequent expectancy violations. Given that we did not detect effects due to timing, this implies that the manipulation of a single event may be too granular to influence metanarrative structure. Instead, structural effects might require manipulating a grander constellation of events – including how other characters react to the cascading influence of such events. To illustrate, in our story, we held everything constant except for the side-taking event and the order of the narrative. Although this helped ensure experimental validity, it diminished ecological validity because the characters did not adjust their behaviors accordingly. Given this, perhaps the influence of metanarrative structure requires greater levels of contingency to produce effects. For instance, the protagonists may need to express continued suspicion toward a traitor and, conversely, warmth toward a supporter.

Alternatively, a single side-taking element may be capable of altering the shape of stories, but such granular elements may require greater centrality. In detail, our story used a somewhat neutral peripheral actor to manipulate side-taking. The timing of side-taking may affect metanarrative structure if a main character switched sides rather than a secondary character choosing a side. This possibility is reasonable, as a central character switching sides would be unexpected and cause large disturbances to the character relationship network.

Limitations

Scope is a limitation of the current study, as we did not test all variants of side-taking. Instead, we observed the effects of a character switching their side-taking motive (i.e., siding with the protagonists), maintaining their side-taking motive (i.e., siding against the protagonists), or remaining ambiguously neutral (i.e., taking no side). Many other variations exist that could help distinguish if our effects are idiosyncratic. For example, it is possible that a more dramatic form of side-taking could produce pronounced macro effects (e.g., a protagonist switching to antagonist). Future work on side-taking could more systematically compare various forms of side-taking using different side-taking strategies (e.g., bandwagoning) and alternating their temporal sequencing.

Similarly, the nature of the story we created poses limitations on generalization. Because we used a war story that construed the side-taking actor as categorically antagonistic but dependent upon the protagonists, our operationalization is a narrow-scoped representation of side-taking. Side-taking can be an impulsive reaction, a thoughtful deliberation, or – as is the case in our study – a supportive change of heart or nefarious betrayal. Therefore, our findings may only generalize to acts of side-taking that mirror those present in our story. Nevertheless, the data present a clear case for this form of side-taking that may aid future theorizing.

Another limitation is our balance of experimental and ecological validity. Given that we composed our own narrative and omitted contingency, our story lacks strong ecological validity. Our lack of contingency (e.g., the story resolutions did not change based on the direction of side-taking) may have attenuated macro-level effects generated by side-taking. Likewise, given that side-taking only accounted for a small moment of our story, other story elements may have contributed to effects or diminished our targeted effects (i.e., it lacks strong experimental validity). Notably, side-taking is somewhat entangled with related concepts such as schema violations, ingroup/outgroup similarity, and empathy. Our work cannot rule out the possibility that such related concepts may explain some portion of our (null) findings. For example, it is possible that people sympathized with the side-taking agent’s pitiful state (e.g., starving). If so, this may have produced unexpected results (e.g., betraying the protagonists may not have been as unenjoyable as it could have been). Despite this, this foray into an empirical application of side-taking should help researchers in this area refine conceptualizations and operationalizations to better distinguish side-taking.

Another limitation is that we did not measure dispositions after each story beat. Therefore, we relied on holistic evaluations of the side-taking agent. A more fine-grained approach may have revealed that more established dispositions could have influenced the effects of side-taking differently than less established dispositions.

Conclusion

Side-taking explains how people understand, react to, and reconcile moral conflict. Its grounding in moral psychology and its commonality in narrative make it relevant to existing work in media psychology. Although research exists investigating how morality explains entertainment and audience perceptions, media effects researchers have yet to conceptualize and investigate side-taking systematically. The present work fills these gaps and presents evidence that side-taking is cogent narrative structural element – explaining reactions to individual events, characters, and overall stories.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/K5RZ3 and https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/U4S6G

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data will be made available upon request by contacting the corresponding author

References

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364

- Bonus, J. A., Matthews, N. L., & Wulf, T. (2019). The impact of moral expectancy violations on audiences’ parasocial relationships with movie heroes and villains. Communication Research, 48(4), 550–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650219886516

- Burgoon, J. K. (2015). Expectancy violations theory. In The international encyclopedia of interpersonal communication (pp. 1–9). American Cancer Society. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118540190.wbeic102

- Critcher, C. R., & Dunning, D. (2014). Thinking about others versus another: Three reasons judgments about collectives and individuals differ. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8(12), 687–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12142

- DeScioli, P., & Kurzban, R. (2013). A solution to the mysteries of morality. Psychological Bulletin, 139(2), 477–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029065

- Eden, A., Daalmans, S., & Johnson, B. K. (2017). Morality predicts enjoyment but not appreciation of morally ambiguous characters. Media Psychology, 20(3), 349–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2016.1182030

- Eden, A., Oliver, M. B., Tamborini, R., Limperos, A., & Woolley, J. (2015). Perceptions of moral violations and personality traits among heroes and villains. Mass Communication and Society, 18(2), 186–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2014.923462

- Frazer, R., Moyer-Gusé, E., & Grizzard, M. (2022). Moral disengagement cues and consequences for victims in entertainment narratives: An experimental investigation. Media Psychology, 25(4), 619–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2022.2034020

- Grizzard, M., Fitzgerald, K., Francemone, C. J., Ahn, C., Huang, J., Walton, J., McAllister, C., & Lewis, R. J. (2021). Narrative retribution and cognitive processing. Communication Research, 48(4), 527–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650219886512

- Grizzard, M., Francemone, C. J., Fitzgerald, K., Huang, J., & Ahn, C. (2020). Interdependence of narrative characters: Implications for media theories. Journal of Communication, 70(2), 274–301. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa005

- Grizzard, M., Huang, J., Fitzgerald, K., Ahn, C., & Chu, H. (2018). Sensing heroes and villains: Character-schema and the disposition formation process. Communication Research, 45(4), 479–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217699934

- Grizzard, M., Matthews, N. L., Francemone, C. J., & Fitzgerald, K. (2021). Do audiences judge the morality of characters relativistically? How interdependence affects perceptions of characters’ temporal moral descent. Human Communication Research, 47(4), 338–363. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqab011

- Hamby, A., Shawver, Z., & Moreau, P. (2020). How character goal pursuit “moves” audiences to share meaningful stories. Media Psychology, 23(3), 317–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1601569

- Hopp, F. R., Fisher, J. T., & Weber, R. (2020). A graph-learning approach for detecting moral conflict in movie scripts. Media and Communication, 8(3), 164–179. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i3.3155

- Kleemans, M., Eden, A., Daalmans, S., van Ommen, M., & Weijers, A. (2017). Explaining the role of character development in the evaluation of morally ambiguous characters in entertainment media. Poetics, 60, 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2016.10.003

- Krakowiak, K. M., & Tsay‐Vogel, M. (2015). The dual role of morally ambiguous characters: Examining the effect of morality salience on narrative responses. Human Communication Research, 41(3), 390–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12050

- Krcmar, M. (2013). The effect of media on children’s moral reasoning. In R. Tamborini (Ed.), Media and the moral mind (pp. 198–217). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kurt Vonnegut on the Shapes of Stories. (2010, October 30). [Video file]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oP3c1h8v2ZQ

- Kurzban, R., DeScioli, P., & Fein, D. (2012). Hamilton vs. Kant: Pitting adaptations for altruism against adaptations for moral judgment. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33(4), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2011.11.002

- Matthews, N. L., & Bonus, J. A. (2021). How moral expectancy violations influence audiences’ affective dispositions toward characters. Communication Research, 50(3), 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502211039959

- Nabi, R. L., & Green, M. C. (2015). The role of a narrative’s emotional flow in promoting persuasive outcomes. Media Psychology, 18(2), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2014.912585

- Oliver, M. B., & Bartsch, A. (2011). Appreciation of entertainment: The importance of meaningfulness via virtue and wisdom. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, & Applications, 23(1), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000029

- Raney, A. A. (2002). Moral judgment as a predictor of enjoyment of crime drama. Media Psychology, 4(4), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0404_01

- Raney, A. A. (2005). Punishing media criminals and moral judgment: The impact on enjoyment. Media Psychology, 7(2), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0702_2

- Raney, A. A. (2011). The role of morality in emotional reactions to and enjoyment of media entertainment. Journal of Media Psychology, 23(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000027

- Raney, A. A. (2013). How we enjoy and why we seek out morally complex characters in media entertainment. In R. Tamborini (Ed.), Media and the moral mind (pp. 176–193). Routledge.

- Raney, A. A., & Bryant, J. (2002). Moral judgement and crime drama: An integrated theory of enjoyment. Journal of Communication, 52(2), 402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02552.x

- Reagan, A. J., Mitchell, L., Kiley, D., Danforth, C. M., & Dodds, P. S. (2016). The emotional arcs of stories are dominated by six basic shapes. EPJ Data Science, 5(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-016-0093-1

- Sanders, M. S. (2010). Making a good (bad) impression: Examining the cognitive processes of disposition theory to form a synthesized model of media character impression formation. Communication Theory, 20(2), 147–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01358.x

- Sanders, M. S., & Tsay-Vogel, M. (2016). Beyond heroes and villains: Examining explanatory mechanisms underlying moral disengagement. Mass Communication and Society, 19(3), 230–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2015.1096944

- Shafer, D. M., & Raney, A. A. (2012). Exploring how we enjoy antihero narratives. Journal of Communication, 62(6), 1028–1046. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01682.x

- Silver, I., & Shaw, A. (2022). When and why “staying out of it” backfires in moral and political disagreements. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 151(10), 2542–2561. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001201

- Tamborini, R., Weber, R., Eden, A., Bowman, N. D., & Grizzard, M. (2010). Repeated exposure to daytime soap opera and shifts in moral judgment toward social convention. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 54(4), 621–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2010.519806

- Weber, R., Tamborini, R., Lee, H., & Stipp, H. (2008). Soap opera exposure and enjoyment: A longitudinal test of disposition theory. Media Psychology, 11(4), 462–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260802509993

- Zillmann, D. (2000). Basal morality in drama appreciation. In I. Bondebjerg (Ed.), Moving images, culture and the mind (pp. 53–63). University of Luton Press.

- Zillmann, D., & Bryant, J. (1975). Viewer’s moral sanction of retribution in the appreciation of dramatic presentations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 11(6), 572–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(75)90008-6

- Zillmann, D., & Cantor, J. (1976). A disposition theory of humor and mirth. In T. Chapman, & H. Foot (Eds.), Humor and laughter: Theory, research, and application (pp. 95–115). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203789469-6