?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Three studies tested the prevalence of usage and interpretation of messages in which a text and an emoji convey incongruent meaning. Self-reports (Study 1, N = 723) and an experiment that manipulated interlocutor relationships and scenario valence (Study 2, N = 309) revealed that incongruent messages are sent relatively infrequently, in instances in which the text alone may threaten interpersonal relationships. Study 3 (N = 296) confirmed that incongruent messages are less comprehensible and that their perceived valence is shifted from the text valence toward the valence of the emoji. Furthermore, participants correctly inferred the relationships between the communicators, especially when the messages involved close relationships and were congruent with the emoji. We conclude that in incongruent message, the text communicates the intended message, while the emoji serves interpersonal pragmatics.

Introduction

Emojis, as well as their predecessors the emoticons, have been designed primarily to communicate nonverbal information. While in face-to-face conversations we convey such information through facial expression and other physical gestures (Bai et al., Citation2019, Derks et al., Citation2008, Dresner & Herring, Citation2010), this part of communication may be lost in text messages (Walther, Citation1996, Citation2011). Emojis are used to clarify the message intention and reduce ambiguity (Bai et al., Citation2019; Derks et al., Citation2008; Erle et al., Citation2022; Ganster et al., Citation2012; Holtgraves et al., Citation2020; Kaye et al., Citation2016; Kruger et al., Citation2005; Thompson & Filik, Citation2016). The current study explores the usage of emojis in written communication, specifically in occasions in which they contradict the content delivered by the texts. Following theories of pragmatics, we assume that individuals add information for a reason, and therefore we suggest that such incongruence is intentional and that it serves interpersonal purposes.

Pragmatically, emojis clarify and strengthen the message, describe text content, express sentiment, instill certainty, add humor or seriousness, invoke irony, supplement intimacy, emphasize personal tone, adjust or modify tone or mood, and soften the message (Dresner & Herring, Citation2010, Hamdan, Citation2022, Herring & Dainas, Citation2020, Logi & Zappavigna, Citation2023, Riordan, Citation2017, Sampietro, Citation2019, Skovholt et al., Citation2014, Li & Yang, Citation2018). Previous studies have focused mainly on the pragmatic functions of the expression of emotions (Kralj Novak et al., Citation2015, Prada et al., Citation2018, Stark & Crawford, Citation2015), clarification, disambiguation, and strengthening of the text, which are perhaps the most cited reasons for using emojis. The current study addresses emojis whose purpose is to blur, mask, and alter the meaning of messages.

Kralj Novak et al. (Citation2015) used sentiment analysis and found that the majority of emojis convey a positive sentiment, and that positive texts include emojis more frequently than do negative texts. Thus, in many instances, emojis serve to reinforce and strengthen positive messages. However, emojis may also modify the tone of the text (Danesi, Citation2017, Sampietro, Citation2019, Skovholt et al., Citation2014) or change the meaning entirely (Lo, Citation2008). For example, studies of sarcasm in online communication (Garcia et al., Citation2022, Thompson & Filik, Citation2016, Walther & D’Addario, Citation2001) reveal that people add emojis to (mostly negative) texts to enhance the comprehension of written sarcasm. Employees use emoticons to tone down requests from colleagues, corrections of peers and complaints at work (Beißwenger & Pappert, Citation2019, Skovholt et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, Sampietro (Citation2019) employed discourse analysis of a large corpus of WhatsApp communication interactions and found that emojis lighten up negative texts. Rodrigues et al. (Citation2017) experimentally manipulated positive and negative texts to either include emojis or not. Their findings suggested that including an emoji in a negative text signified that the text was “not a serious issue” and increased the perceived positivity of the text, which in turn increased the perceived interest in the relationship between the interlocutors.

Textual communication affords a high level of control (Valkenburg & Peter, Citation2011, Walther, Citation1996, Citation2011). It is easy to review and revise the text before sending it, and in many chat applications even to immediately delete the text before the recipient reads it. Given these conditions, the need to alter the meaning of the message by adding an emoji could be dispensable. We suggest that sending incongruent messages has a pragmatic role. Specifically, the sender aims to communicate the message as written, be it positive or negative, while maintaining the relationship with the recipient. Thus, the sender uses two communicating channels, and each channel serves different function. The text communicates content while the emoji tones this content down – by communicating an emotion that contrasts the text – thus conveying a message that concerns the interpersonal relationship.

Indeed, emojis may serve in interpersonal pragmatics. Locher and Graham (Citation2010) defined interpersonal pragmatics as those aspects of conversations in which individuals invest in the construction, maintenance, reproduction, and transformation of interpersonal relationships. Spencer-Oatey (Citation2005, Citation2011) focused specifically on rapport management, which she defined as the management or dis-management of an individual’s subjective perceptions of (dis)harmony, smoothness-turbulence, and warmth-antagonism in interpersonal relations. Testing rapport management in WhatsApp chats, Sampietro (Citation2019) revealed that emojis helped users adjust the message to be socially appropriate, signal the social relationship between the chatters, and negotiate and orient the social purposes of the conversation. Beißwenger and Pappert (Citation2019) showed that emojis served as efficient means for the social organization of interaction between students whose task was to provide feedback to each other. Similarly, Flores-Salgado and Witten (Citation2023) found that emojis facilitated the management of interpersonal relationships in WhatsApp group conversations. Thus, incongruent emojis may specifically have this pragmatic role.

Although emojis foster social connectedness between users and increase intimacy (Janssen et al., Citation2014; Kelly & Watts, Citation2015; Riordan, Citation2017), they may serve different purposes when sent to a close person (a friend, an intimate partner, or a family member) relative to distant people (teachers, supervisors, bosses) (L. L. Jones et al., Citation2020). In fact, ratings of emojis used in communication with distant (vs. close) persons show that they deemed more inadequate, especially for negative messages (Cavalheiro et al., Citation2022). Using emojis in the first virtual conversation at work does not increase perceptions of warmth, and instead it decreases perceptions of competence (Glikson et al., Citation2018). Thus, sending an emoji that is incongruent with the text may be more prevalent in close relationships than in distant relationships, particularly if the text is negative. In close relationships, incongruent emojis may serve to regulate and maintain the relationship when the text presents a threat to this relationship. In addition, incongruent emojis may be less frequent in communication with distant people.

A message that includes an incongruent emoji may amplify comprehension difficulties, which are inherent to written communication. Studies on the understanding of emojis show inconsistent results (Sampietro, Citation2020). On the one hand, the use of emojis is consistent across countries in terms of the overall semantics of the most frequent emojis (Barbieri et al., Citation2016; Danesi, Citation2017). On the other hand, there are differences in the interpretation of the same emojis across cultures (L. L. Jones et al., Citation2020, Miller et al., Citation2016), even when these emojis are embedded within a congruent text (Miller et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, emojis may carry multiple meanings (Wu et al., Citation2022) and these meanings may complicate the interpretation of the sender’s intention. Therefore, understanding the meaning of an incongruent message, in which the text and the emoji convey different meanings, might be very difficult. Daniel and Camp (Citation2020) found that participants rated messages that appeared with incongruent emojis as less comprehensible than messages that appeared with congruent emojis. In addition, it took more time to process incongruent messages than congruent messages (Barach et al., Citation2021, Beyersmann et al., Citation2022, Boutet et al., Citation2021), attesting to the difficulty in interpreting incongruent messages. Yet, Weissman et al. (Citation2018) found that incongruent messages were interpreted as conveying the nonliteral meaning of a message (i.e., participants gave greater weight to the emojis than to the text). That is, despite the cognitive challenges posed by incongruent messages, participants succeed in understanding that the sender’s intended to tone down or to soften the text.

The current research aims to examine who uses incongruent emojis, when, and why. We employed three complementary study approaches. First, we asked individuals about their overall usage of emojis (Study 1). Second, we experimentally manipulated two variables that may affect the utilization of incongruent emojis, namely – the degree of closeness of the relationship and the message sentiment (Study 2). Third, to gain insight into the comprehensibility of messages that present a text-emoji incongruity, as well as the norms of sending such messages, we asked participants to interpret messages and to infer the relationships between interlocutors (Study 3). Our main goal is to illuminate the pragmatic functions of using incongruent emojis.

Study 1: Self-Reported Use of Emojis

Study 1 is descriptive in nature, and aims to describe the usage of emojis, and to map their pragmatic role as well as the motivations to add them to textual messages. We aimed to estimate how often people use emojis and for which purposes. We also examined gender and age differences in the use of emojis (e.g., Koch et al., Citation2022, Prada et al., Citation2018), as well as instances in which individuals add emojis either to support the text or to alter its meaning.

Method

Participants

Seven-hundred and 23 Hebrew speaking Israeli residents (537 women and 186 men) participated in an online survey. Age ranged from 18 to 70 years old (M = 31.55, SD = 10.38). Participants were recruited through an invitation on personal and public Facebook accounts, personal Twitter accounts, and through WhatsApp groups.

Ethical approvals for the three studies were obtained from the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Survey

Frequency of using emojis

Participants reported their use of emojis by selecting one of four options: in every instance of online communication or almost in every instance; in more than half of the instances; in less than half of the instances; not at all or almost never.

Pragmatic goals of using emojis

Participants marked all possible reasons for using emojis from a list of 18 options. We selected ten reasons that referred to strengthening textual communication and eight reasons that referred to weakening of these communications. Eight items were phrased as two opposing reasons, first as positive (e.g., to strengthen my textual message) and then as negative (e.g., to weaken my textual message). Two additional reasons did not have opposing phrases (to instill my personality into the text, to express mischievousness). The reasons were drawn from previous classifications of the pragmatic use of emojis (Dresner & Herring, Citation2010; Hamdan, Citation2022; Herring & Dainas, Citation2020; Li & Yang, Citation2018; Logi & Zappavigna, Citation2023; Riordan, Citation2017; Skovholt et al., Citation2014). The full list of reasons appears in . Since sometimes people ascribe different purposes to themselves and to others (i.e., the self-other asymmetry bias, E. E. Jones & Nisbett, Citation1972; Pronin, Citation2007), after selecting one’s own reasons for using emojis, participants marked the reasons that another person who sends them an online message would use emojis.

Table 1. Pragmatic goals of using emojis.

Achievement of pragmatic goals

Participants reported how often the addition of emojis to their text messages helped them strengthen or clarify the message, as well as how often adding emojis to their text messages helped them weaken or tone down their text. The scale for these two questions were 1 = never helps to 5 = always helps.

Instances of using emojis

Participants described an instance in which they used an emoji to strengthen or to clarify a message, and then they described another instance in which they used an emoji to weaken or to tone down a message. The content of these instances (n strength = 288; n weaken = 97) was analyzed by two independent raters. First, one rater categorized the message relatively narrowly, and then the categories were clustered into four broad categories: (1) expressing emotions; (2) meaning clarification; (3) relationship maintenance; and (4) managing (controlling or adjusting) the conversation. The two raters classified the messages using the narrow categories, but reliability was tested over the broad categories. Cohen’s κ for instances that were used to strengthen a message was .831. Cohen’s κ for instances that were used to weaken a message was .716. shows examples of the four categories.

Results

Frequency of Using Emojis

The majority of the sample (84.2%) reported adding emojis in half of their online textual communications or more. Women reported using emojis more frequently than did men, χ2(3) = 52.22, p < .001, and older people reported using emojis less often than did younger people, Spearman’s ρ = −.076, p = .042. Online Table A1 presents the distribution of frequency of use.

Pragmatic Goals of Using Emojis

presents the 18 reasons to use emojis, along with the percentage of participants who ascribed each reason to themselves and to others, the correlations between self and other, gender differences, and age effects. As can be seen in , people use emojis to strengthen the text and to support its meaning far more often than to weaken the text or to tone down its meaning. Approximately 62% of participants reported that they used emojis to strengthen their own messages, and 67% reported that others would use emojis for this purpose. In contrast, only 12% (self) and 16% (other) of the participants reported using emojis in order to weaken their messages. The correlations between self and other pragmatic goals ranged between .215 ≤ r ≤ .534, and were significant at p < .001. We further tested differences between the frequencies of self and other goals, and found that all differences were significant at p < .001 (see ), as participants ascribed goals to others more often than they ascribed the same goals to themselves.

Gender differences emerged for four reasons, all involving strengthening goals (strengthening the message, helping the recipient understand the message as intended, expressing emotions, and expressing humor). Women reported these goals more often than did men. The correlations between goals and age were negative, since older participants marked the presented reasons less often than did younger participants. However, these correlations were weak, and most probably reflected older participants’ tendency not to use emojis.

Achievement of Pragmatic Goals

presents participants’ reports as to whether they achieve their pragmatic goals to strengthen or to weaken the text by adding emojis. Clearly, most participants (93.9%) feel that adding emojis helps them strengthen or clarify the message at least half the time. Reports for weakening messages through the addition of emojis show that less than half the participants (42.1%) feel that adding emojis helps them achieve this goal at least half the time, and many participants (31.3%) feel that they have never achieve this goal. This difference between distributions of achievement of strengthening and weakening goals is significant, χ2(16) = 81.69, p < .001. Gender and age differences were tested using t-test (for gender) and Spearman’s ρ (for age). A significant gender difference was found for achievement of strengthening goals, t(721) = 3.96, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.337, as women felt that they achieved these goals more often than did men. The results of all other tests were not significant.1

Table 2. Frequencies (%) of achievement of pragmatic goals.

Instances of Using Emojis

presents the distribution of the purposes that participants stated when asked to describe instances of adding emojis to their text messages. Participants reported using emojis to strengthen the text primarily in order to instill emotions and then to clarify the intention. In contrast, they reported using emojis to weaken the text in order to maintain their relationships with their interlocutors and to manage the conversation (mainly to chill down a heated discussion). The difference between the two distributions is significant, χ2 (4) = 120.13, p < .001.

Table 3. Frequencies of reported purposes of using emojis.

Discussion

Our study corroborates previous research on the use of emojis, showing that participants report adding them to text messages quite often. Similar to previous studies, women (vs. men) and younger people (vs. older) use emojis more frequently. Note, however, that we used a convenient sample rather than a representative one. We also found that emojis serve to strengthen the text and to support its meaning more than to weaken it or to tone it down. Gender and age differences in pragmatic usage of emojis were rather small. The majority of the participants reported that adding (congruent) emojis indeed helped them strengthen or clarify the message. Moreover, participants informed less often that including (incongruent) emojis assisted them to weaken, soften, tone down or alter the meaning of the text. This presumed lack of success may reflect the fact that people use emojis for strengthening the text more often than they use them to weaken the text.

In addition, we found a self-other bias: Participants ascribed specific goals to themselves less often than they ascribed the same goals to others. The classical self-other asymmetry bias (E. E. Jones & Nisbett, Citation1972) and the tendency for self-favoring (Hoorens, Citation1995) suggest that people tend to see themselves in a more positive way then they see others. Self-other bias has been frequently documented in online communication (e.g., Caspi & Etgar, Citation2023; Caspi & Gorsky, Citation2006; Corbu et al., Citation2020; Kim & Hancock, Citation2015). It may suggest that participants consider the usage of emojis to strengthen or to weaken the text as a less advanced communication skill, and therefore they ascribe such acts to themselves less often than to others.

Four functions emerged from the classification of instances in which participants used emojis. The main use of emojis to strengthen the text reflected the wish to express emotions. This is indeed the leading pragmatic role cited and explored in the literature (Kralj Novak et al., Citation2015). The primary reason for using emojis as a means for weakening the text was to clarify the meaning of the text. When the text might be interpreted as too extreme, too serious, or too threatening, people sometimes choose not to change the text but instead to use an emoji to signify that the recipient should not interpret it “as is.” The decision to communicate the message in its “rough” textual version and weaken it with the use of an emoji rather than to edit the text is interesting. As we contended, people do so because they want to communicate the “bold” meaning (either negative or positive) while keeping the relationship with the recipient unharmed. For example, criticizing a close friend for her behavior has the potential to impair the relations with her. Adding an incongruent emoji to the negative criticism may communicate the desired close relationships while still addressing the criticism.

Maintaining relationships and managing conversation are pragmatic roles that emerged almost exclusively when people described using emojis to weaken the text. Together, it seems that using incongruent emojis to modify the text is part of interpersonal pragmatics. Thus, incongruent emojis serve for rapport management when relational harmony is threatened.

Study 2: Manipulating Relationships and Valence to Test Spontaneous Use of Emojis

The goal of Study 2 was to simulate real textual conversations while manipulating two key features of communication. First, we manipulated the level of closeness between interlocutors. Following L. L. Jones et al. (Citation2020), we hypothesized that

H1:

People use emojis more often when texting people with whom they are close.

Second, we tested the effect of the valence of the message. Following Kralj Novak et al. (Citation2015), we hypothesized that

H2:

Replying to a positive message will include more emojis than replying to a negative message.

We also expected to find

H3:

More text-emoji congruency in positive than in negative messages. Furthermore, assuming that negative messages call for weakening pragmatics, we expected to find

H4:

More incongruent emojis in communication about negative content with close relative to distant people.

Method

Participants

In a pilot study that included 188 participants, we found medium effect sizes (Cohen’s fs = 0.30). Based on these effects, given a power of .95 and an alpha of .05, a sample size of at least 280 participants was required, with 70 participants in each of the four experimental conditions. We recruited 309 participants between age 17 and 74 (M = 32.68, SD = 10.91; 186 women). presents demographic characteristics of participants in the four conditions. Gender distribution differed between conditions, χ2(3) = 9.03, p = .03, but age and reported emoji use did not [F (3, 307) = 0.746, p = .526, = .007 for age; F (3, 304) = 1.041, p = .374,

= .010 for use]. Data collection took place at central streets, squares, beaches, and other public areas in Tel Aviv. Pedestrians were invited to participate, and if agreed were asked to give their cell phone number to which the experimenters texted an initial message. The experimenters then moved to a distant place in which they could still see the participants during the rest of the experiment. This was done in order to make the simulation as close to real-life textual conversation while overseeing that no special interference occurs. Participants received instructions and sent their replies through WhatsApp.

Table 4. Demographic characteristics and distributions of emoji-only and text-only messages in study 2.

Stimuli and procedure

Participants first texted their age to the experimenters and were then randomly assigned to one of the four experimental conditions. They were asked to imagine that they communicated either with a close person (a partner, a friend, or a family member) or with a distant person (a fellow student, a colleague at work, a neighbor, or even a shopkeeper whom they know somehow). Then, half the participants were instructed to text a positive message (expressing enthusiasm about a planned meeting), while the other half were instructed to text a negative message (expressing disappointment or anger about the cancellation of a planned meeting). The instructions explicitly stated that in writing the message the participants should compose a message, as similar as possible to a message that they would normally write to the imagined recipient in terms of the number of words, grammar, or any other aspect. There was no mention of emojis (see the Appendix for the full instructions in the four conditions).

After sending the requested message, participants were asked (1) what kind of relationship they had with the recipient of the message (e.g., father, mother, partner, friend); (2) which specific emotion they felt when composing the message; (3) during the last week, how often they used emojis in their textual communication, with 0 = never and 100 = in all communications; (4) which feeling they intended the recipient to experience, with 5 = highly positive, 0 = no specific feeling, and −5 = highly negative.

Last, the experimenters sent the participants a debriefing message and thanked them for their participation.

Analysis

Text and emoji valence

Two independent raters analyzed the content of the text and the valence of the emojis. First, text and emojis were separated into two files, so that the analysis would not be mutually affected. Then, each text and each emoji (or a bunch of emojis, if more than one emoji appeared in the message) were classified as positive, negative, or neutral/cannot be classified. Inter-rater agreement was very high, with only 4.3% of the texts and 4.4% of the emojis classified differently by the two raters, or classified as neutral or could not be classified. To validate the analysis of valence of each emoji, we used Godard and Holtzman’s (Citation2022) multidimensional lexicon of emojis. The correlations between the valence classified by the raters and the positive and the negative dimensions of Godard and Holtzman were medium-high (rs = .666 and −.784, respectively, ps < .001), validating the current analysis.

Feeling while composing the text

We used Jackson et al. (Citation2019) list to classify participants’ reported emotions. This list offers a universal classification of words into 24 emotions. If an emotional description did not appear in the Jackson et al.‘s list, we used Shaver et al. Citation(1987) hierarchical classification of emotions (see ).

Table 5. Distribution of reported feelings.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Thirty participants composed a message without text, and sent only an emoji as a message. There was no significant difference across conditions, χ2(3) = 3.65, p = .302 (see ). One-hundred and 36 participants sent only text with no emoji. There were more messages with no emoji in the negative (vs. positive) valence conditions, χ2(3) = 30.49, p < .001 (see ).

Overall, spontaneous use of emojis was found in 56% of the messages. This percentage is similar to the sample mean self-reported usage (which was 59.98, SD = 28.17), but lower than the 80% rate of self-reports in Study 1.

Online Table A2 presents the distribution of recipients by conditions. Participants in the close conditions sent messages to family members and close friends, whereas participants in the distant conditions sent message to colleagues, neighbors, and distant friends. Thus, participants understood the instructions and generally imagined a person as required.

Next, we tested whether participants responded with the emotion that the scenario stimulated (expectation vs. cancelation). In particular, we assumed that participants in the expectation scenario would express positive emotions, whereas participants in the cancellation scenario would express negative emotions. We also assumed that both emotions would be higher when the message addressed a close person relative to a distant person. presents the results.

First, participants in the distant conditions reported no feelings at all or indifference four times as often as participants in the close conditions. Second, to test the 2 (relation: close vs. distant) X 2 (valence: positive vs negative) X 2 (emotion felt: positive vs. negative) contingency table, we used Wilks (Citation1935, Citation1938) likelihood-ratio statistic (G2). The triple interaction of relation by valence by emotion felt was significant, G2(4) = 203.58, p < .001. Testing the simple interactions, controlling for the third variable, revealed a significant interaction between relation and emotion felt, G2(2) = 5.78, p = .05, a significant interaction between valence and emotion felt, G2(2) = 202.92, p < .001, and a marginally significant interaction between relation and valence, G2(2) = 5.24, p = .07. Participants reported more positive emotions in the positive scenarios and more negative emotions in the negative scenarios. This effect was larger in the close than in the distant condition.

Hypotheses Testing

We predicted that participants would use emojis more often when texting to people who are close to them (H1). In the close conditions, 59.2% of the messages included emojis, whereas in the distant conditions 52.1% of the messages included emojis, and the difference was not significant, χ2(1) = 1.54, p = .21. Thus, the first hypothesis received no support. We also predicted that in a message about a positive scenario participants would include more emojis than in a message about a negative scenario. As H2 predicted, 70.2% of the positive messages included emojis as opposed to only 42.4% of the negative messages, and the difference was significant, χ2(1) = 24.20, p < .001. In addition, as H3 suggested, there was greater text-emoji congruency in positive than in negative messages (75 vs. 33 respectively, see Online Table A3). Last, H4 hypothesized that negative messages that are sent to someone close will include more incongruent emojis than negative messages that are sent to a distant person. Online Table A3 presents the distribution of 147 messages that included both text and emojis in the four experimental conditions, according to the congruency between the text and the emoji. Most of the messages were congruent, and incongruent messages were rare. The vast majority of these rare occasions were in negative messages, but the low number of incongruent message limits any reliable conclusions.

We further examined the emotion that participants intended to convey. A two-way ANOVA with relation and valence as between-subjects variables revealed a significant main effect of valence, F (1, 289) = 181.92, p < .001, = .386. The average intended emotion in the positive conditions received a score of 4.29 (SD = 1.18), and in the negative conditions it received a score of 0.48 (SD = 3.16). There was no significant effect of relation, F (1, 289) = 2.40, p = .122,

= .008, and no significant interaction, F (1, 289) = .086, p = .770,

= .000. Since the number of messages that included an incongruent emoji was so low, we could not test the relation between congruency and intended emotion.

Discussion

Study 2 shows that participants use emojis spontaneously in 50–60% of their messages, more often in positive (vs. negative) messages, and almost entirely when the text and the emoji are congruent with each other. We failed to find differences between close and distant relationships.

Incongruity between text and emojis was rare, but when it occurred, its purpose was to soften or alter negative messages. Indeed, a study by Togans et al. (Citation2021) also found low use of emojis that were incongruent with the scenario valence (e.g., positive emojis in threatening communication or negative emojis in non-threatening communication) relative to emojis that were congruent with the scenario valence. We note that the low number of messages that included an emoji for weakening, altering, or toning down the text in the current experiment does not imply that they are necessarily that rare in real life. First, results of Study 1 that rely on self-reports provided a higher estimate of such use. Second, the simulated communication in the current study was quite short relative to real conversations, thus limiting the potential to use emojis. Third, the average intended emotion in the negative conditions was around 0 (i.e., intended neutral rather than negative emotion), and these emotions required less toning down of the text.

It is plausible to consider whether the low incidence of incongruent messages might be attributable to typing errors. However, we assert that the inclusion of incongruent emojis in text is typically a deliberate action, intends to convey interpersonal pragmatics. The findings of Study 1 revealed that people intentionally used text-emoji incongruent combination at least sometimes, and as discussed above, the infrequent occurrences observed in Study 2 may be attributed to methodological limitations.

Study 3: Understanding and Inferring Interlocutor Relations and the Sender’s Emotional State

So far, we have shown that people use emojis to achieve diverse pragmatic functions. Study 3 aims to examine the interpretation of messages that include emojis. Of particular interest are the infrequent occasions in which the emojis are incongruent with the text. We recruited a new sample of participants and presented them with short excerpts that were taken from the real messages that the participants of Study 2 wrote. We asked the new sample of participants about the meaning of these messages. Based on previous studies (Daniel & Camp, Citation2020; Hand et al., Citation2022; Walther & D’Addario, Citation2001) we predicted that

H5:

Incongruent messages (vs. congruent) would be less comprehensible.

Since incongruity may dilute the emotionality of the text (Rodrigues et al., Citation2017; Sampietro, Citation2019), it is hypothesized that

H6:

Incongruent messages would be interpreted as communicating a lessened emotion.

Assuming that people add an emoji whose meaning contradicts the text primarily to maintain interpersonal relationships or to manage the conversation, we predicted that

H7:

Participants would consider incongruent messages as conversations between close (vs. distant) people.

Method

Participants

To achieve medium effect sizes (Cohen’s fs = 0.30), given a power of .95 and an alpha of .05, a sample of 280 participants was required to detect the main effects of congruency, emotions, and relations, as well as the interactions between them. Two-hundred and 96 psychology students (age 18–65, M = 29.9, SD = 8.55; 230 women and 66 men) participated in an online experiment.

Stimuli and Procedure

Participants received a link to an online experiment, and were instructed to interpret 16 messages that were designed as a WhatsApp communication between X (the sender) and Y (the recipient). The message involved an announcement by X of either expecting or canceling a meeting with Y. The response that Y sent was taken from the messages that Study 2 participants composed in all four conditions. Study 3 included close vs. distant conditions as well as response to a positive vs. a negative message, and each of these conditions appeared as either text-emoji congruent or text-emoji incongruent. There were two conversations per condition, and altogether 16 conversations. The order of presentation was random. Since in Study 2 there was only one incongruent message in the positive condition (a reply to a message about an expected meeting), we added incongruent emojis to the original texts that were drawn from this condition.

Each conversation was presented separately, followed by three questions that appeared in a fixed order: (1) To what extent do you understand Y’s reply? (1 = absolutely unclear to 7 = absolutely clear); (2) In your opinion, what is Y’s emotional state? (1 = totally negative to 7 = totally positive); (3) In your opinion, do X and Y have a close or a distant relationship? (1 = very distant to 7 = very close).

Results

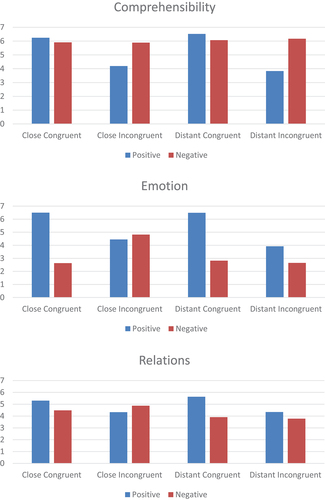

We ran three repeated measures ANOVAs, one for each question, with relation (close vs. distant), valence (positive vs. negative), and text-emoji congruency (congruent vs. incongruent) as the within-subject factors. To make the presentation of results as simple as possible, for each analysis below we first report the main effect of the relevant factor, then the moderation of the most important second factor, and last the moderation of the remaining factor, if it existed. All other simple effects and interactions appear in Online Appendix Tables A3-A4. presents the means and SDs for the three measures in the eight conditions.

Figure 1. Averages of comprehensibility, emotional state, and perceived relationship, by valence, relations, and text-emoji congruency.

Comprehensibility

The main effect of congruency was significant, F (1, 295) = 431.429, p < .001, = .594, as congruent messages received higher comprehensibility scores. This effect was moderated by relations, F (1, 295) = 18.090, p < .001,

= 0.058. An analysis of simple effects revealed that a congruent message sent to a distant person was more comprehensible than a congruent message sent to a close person, F (1, 295) = 23.808, p < .001,

= .075, whereas such a difference was absent for the incongruent messages, F (1, 295) < 1,

= .002, suggesting that incongruent messages are less clear irrespective of the target recipient. The interaction between congruency and relation was moderated by valence, F (1, 295) = 13.319, p < .001,

= .096. To clarify this moderation, we tested positive and negative messages separately. For positive messages, the interaction between congruency and relations was significant, F (1, 295) = 33.608, p < .001,

= .102, whereas for negative messages, the interaction was not significant, F (1, 295) = 2.733, p = .099,

= .009. An analysis of simple effects revealed that the significant interaction found for positive messages reflected the fact that the difference between congruent and incongruent messages that were sent to a close person, F (1, 295) = 315.584, p < .001,

= .517, was smaller than the difference between congruent and incongruent messages that were sent to a distant person, F (1, 295) = 570.915, p < .001,

= .659. To sum up this analysis, messages are more comprehensible when the text and the emoji are congruent and the message is positive. However, the recipient of the message affects this difference, as comprehensibility is higher when the message is sent to a distant rather than to a close recipient. As predicted, incongruent messages are overall less clear.

Emotion

We found a significant main effect of valence, F (1, 295) = 1236.267, p < .001, = .807, as participants rated the emotional state of the recipient as more positive in positive than in negative messages. Text-emoji congruency significantly moderated this main effect, F (1, 295) = 1410.159, p < .001,

= .827. An analysis of simple effects showed that, as predicted, positive texts that included incongruent emojis were perceived as less positive than positive messages with text-emoji congruency, F (1, 295) = 780.446, p < .001,

= .726. However, congruent negative messages were perceived as more positive than incongruent negative messages, contrary to the hypothesis that incongruent emojis tone down the text, F (1, 295) = 111.618, p < .001,

= .275.

The relations between the interlocutors significantly moderated the valence-congruency interaction, F (1, 295) = 202.763, p < .001, =.407. For messages between closely related interlocutors, the valence-congruency interaction was significant, F (1, 295) = 1024.228, p < .001,

=.776. Testing simple effects, we found that congruent positive messages were perceived as more positive than incongruent positive messages, F (1, 295) = 569.799, p < .001,

=.659. A reverse effect was found for negative messages, F (1, 295) = 800.687, p < .001,

=.731, with incongruent messages perceived as more positive (or less negative) than congruent messages, in line with the pragmatic role of weakening or softening emotions. For messages between distant interlocutors, the valence-congruency interaction was also significant, F (1, 295) = 673.404, p < .001,

= .695. An analysis of simple effects showed that congruent positive messages sent to distant recipients were perceived as more positive than incongruent positive messages, F (1, 295) = 849.652, p < .001,

= .742. However, in negative messages the congruency between the text and the emoji led to more positive rating than the lack of congruency, F (1, 295) = 24.824, p < .001,

= .078, a result that contrasts with the pragmatic role of softening the message that we expected to find. In summary, the lack of congruency between text and emoji weakened both positive and negative messages of closely related interlocutors. However, this weakening effect was evident in positive but not in negative messages between distant interlocutors.

Relations

Unlike emotions that participants can detect relatively easily from the text and/or the emoji, the relationship between the sender and the recipient has no overt features. Thus, participants rely on implicit cues when inferring this relationship. Interestingly, we found a significant effect of relations, F (1, 295) = 91.855, p < .001, = .237, as participants differentially detected messages that involved a close recipient and messages that involved a distant recipient. Valence moderated the effect of relations, F (1, 295) = 142.999, p < .001,

= .326, and valence by itself significantly influenced the detection of relations, F (1, 295) = 224.972, p < .001,

= .433, as participants believed that positive messages indicated that the recipient was close more often than they believed that negative messages indicated closeness. However, positive messages that addressed a close recipient were detected as such less often than were positive messages that addressed a distant recipient, F (1, 295) = 12.542, p < .001,

= .041. On the other hand, the detection of relations from negative messages was correct, and messages that addressed close recipients were recognized as such more often than were messages that addressed a distant recipient.

Congruency also moderated the effect of relation, F (1, 295) = 44.457, p < .001, = .131, and had a significant main effect by itself, F (1, 295) = 222.478, p < .001,

= .430. Participants rated congruent messages more often as conversations between close interlocutors than they rated incongruent messages as indications of closeness, in contrast to our hypothesis. In congruent messages, the difference between a message that addressed a close recipient and a message that addressed a distant recipient was significant, F (1, 295) = 6.622, p = .011,

= .022. However this effect was much larger in incongruent messages, F (1, 295) = 134.840, p < .001,

= .314. In both cases, recognition was correct. We failed to find a significant three-way interaction (relation by valence by congruency).

Last, valence moderated the congruency effect, F (1, 295) = 240.464, p < .001, = .449, and this moderation stemmed from a significantly greater attribution of positive than negative congruent messages to close relationships, F (1, 295) = 363.122, p < .001,

= .552, a difference that disappeared when testing incongruent messages, F (1, 295) < 1,

= .000.

In sum, participants partly succeeded in inferring the relationship between interlocutors. The valence of the message and the text-emoji compatibility moderated this inference. Nevertheless, participants believed that congruent messages were more often a sign of a close relationship than were incongruent messages, unlike our hypothesis.

Discussion

Study 3 demonstrated that the lack of congruency between the text and the emoji obscures the meaning of the message and makes it less comprehensible. In incongruent messages, the perceived emotional state of the sender appears to shift toward the sentiment that the emoji conveys, thus toning down or diluting the text. It is important to note that this effect was consistent in messages sent between close interlocutors, which we interpret as indirect evidence for the interpersonal pragmatics of emojis. That is, we believe that the role of the emoji is to orientate the intended relationships between the individuals involved in communication.

The ability of the participants to infer the relationship between the interlocutors might be evidence for the norms that govern the use of emojis. Previous studies have shown that this practice happens more often and is perceived as more appropriate between close friends or family members (Cavalheiro et al., Citation2022; L. L. Jones et al., Citation2020), partly because emojis may signify that the conversation is informal (Beißwenger & Pappert, Citation2019). The current results show that congruency moderates the recognition of relations, and congruent messages associate more intuitively with close relations. We suggest that this attribution of messages resonates the social norm of using emojis for interpersonal pragmatics between close interlocutors. In contrast, we did not find an overall tendency to associate incongruent messages with conversations between close interlocutors, possibly because other cues, especially valence, affected the inference of the relations between communicators.

General Discussion

Our three studies show that people use emojis quite frequently, mostly when they are congruent with the text, and that the main role of emojis is to reinforce and supplement the text. We focused on two major factors that influence the use of emojis – the type of relationship between the interlocutors, and the valence of the conversation. The results corroborated earlier findings, showing that emojis are more common when the interlocutors have close relationships and they mostly appear in positive conversations. The lack of congruency between the text and the emoji, which was the primary focus of the current research, is less frequent, and its main purpose is to tone down negative text. When the text and the emoji do not match, the message becomes less comprehensible, and this ambiguity dilutes the emotion conveyed by the text. We suggest that this lack of congruency is not incidental but rather that it has a pragmatic role. Our discussion focuses on messages that include such incongruence, as congruent messages have received prior attention.

An estimate of the prevalence of sending messages in which the emoji communicates a different meaning than the text underscores the rarity of this phenomenon. Self-reports (Study 1) suggested that approximately 15% of the participants used emojis for changing the text message (weakening purposes). The difference between men and women in using emojis did not characterize the use of incongruent emojis. Younger participants reported that they used incongruent emojis more often than did older participants, possibly because they used more emojis overall. Study 2, in which we simulated text conversations, revealed that the use of incongruent messages was less common. We suggest that the difference between the two studies is due to the short and specific communication presented in Study 2, and perhaps the actual level of sending incongruent messages lies somewhere closer to the frequency reported in Study 1.

While the documented phenomenon is not very common, its existence may open a window to important aspects of communication between people. We asked participants why and when they used incongruent emojis (Study 1), and tested the norms of doing so by asking other participants to rate the comprehensibility, the perceived valence, and the relationship between the interlocutors of such messages (Study 3). Our results as well as previous studies show that emojis that contrast the text serve primarily to manage rapport (Beißwenger & Pappert, Citation2019; Sampietro, Citation2019). Our participants reported that they send emojis that weaken the text to clarify the message, especially when incorrect interpretation might be harmful, and to maintain the relationship, when correct understanding of the text could be detrimental. Thus, sending emojis that contrast the text may serve the three components of rapport management suggested by Spencer-Oatey (Citation2008). These components include maintaining face, for example by keeping the sender’s reputation, managing sociality rights by adjusting the appropriateness of the message, and perhaps most saliently preserving interactional goals by indicating the sender’s intentions.

Given that text communication is more controllable than oral conversation, at least in the sense that we can edit the text before sending it, the decision to send an incongruent message rather than edit the text is most likely a deliberate act. The sender consciously wants to communicate the message as written, be it positive or negative. Adding an emoji that has a contrasting meaning communicates the sender’s pragmatic goal, and we speculate that the dilution of the text is a by-product of this behavior rather than its main purpose. In other words, we suggest that the text communicates the actual message, while the emoji acts through a different channel by transmitting interpersonal cues.

Asking participants to interpret messages revealed two obvious results that replicated previous findings. First, incongruent messages are less comprehensible (e.g., Daniel & Camp, Citation2020), and second their valence is shifted from the text valence toward the valence of the emoji (e.g., Weissman et al., Citation2018). Interestingly, participants inferred that messages sent between close interlocutors were indeed conversations between people having close relationships more than conversations between distant communicators. However, they did not attribute incongruent messages more frequently to conversations between close interlocutors, contrary to our hypothesis that close relationships call for greater management and maintenance. Note that regardless of linguistic cues, participants thought that messages that contained emojis reflected closeness, and therefore they rated all such messages on the “close relations” side of the scale. We suggest that this rating reflects the social norm of sending emojis to close friends or relatives (Cavalheiro et al., Citation2022; L. L. Jones et al., Citation2020). Other cues that appeared in the message assisted participants in their classification of messages according to the type of relationship. Previous studies have shown that characteristics of the author (e.g., age, gender, personality; Schwartz et al., Citation2013), as well as the type of relationship between communicators (Choi et al., Citation2021) could be extracted from textual conversations. It is possible that participants relied on such cues, including the selected emojis, in determining whether the interlocutors were close or distant.

In conclusion, we suggest that incongruent emojis serve a pragmatic purpose. We assume that interlocutors add them for a reason, and that they indicate that the sender wants to maintain closeness despite the expression of negative content.

Limitations and Future Directions

We acknowledge that our research has some limitations. First, the true prevalence of using emojis to alter the meaning of the text is unknown. Estimation based on self-reports was higher than that found in the experiment that aimed to simulate real conversations. Analyses of large databases of actual messages may reveal a more accurate figure. The current findings nevertheless suggest that the use of incongruent emojis to alter the text is less frequent than the use of emojis to strengthen the meaning of the text. Second, our analysis of the motivation to send incongruent messages relied on self-reports, and should be further tested in more systematic experiments. Third, the interpretations of messages in Study 3 relied on single items, and therefore might be less precise than analyses that rely on multiple items. We used single items to overcome possible fatigue, but future studies may adopt a measurement with higher precision.

Summary

We found that people sometimes use emojis to alter the meaning of the text. They do so more often in negative situations, mostly to keep their relationship with the message recipient at a desired level. We suggest that text and emoji may have different pragmatic roles, and that when they appear together in the same message, the emoji carries the interpersonal pragmatic role.

Online Supplemental Material.docx

Download MS Word (36.7 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2024.2374778

References

- Bai, Q., Dan, Q., Mu, Z., & Yang, M. (2019). A systematic review of emoji: Current research and future perspectives. Frontier in Psychology, 10, 2221. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02221

- Barach, E., Feldman, L. B., & Sheridan, H. (2021). Are emojis processed like words? Eye movements reveal the time course of semantic processing for emojified text. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 28(3), 978–991. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-020-01864-y

- Barbieri, F., Kruszewski, G., Ronzano, F., & Saggion, H. (2016). How cosmopolitan are emojis? In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM on Multimedia Conference-MM ’16 (pp. 531–535). ACM, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1145/2964284.2967278

- Beißwenger, M., & Pappert, S. (2019). How to be polite with emojis: A pragmatic analysis of face work strategies in an online learning environment. European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 225–254. https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2019-0003

- Beyersmann, E., Wegener, S., & Kemp, N. (2022). That’s good news ☹ Semantic congruency effects in emoji processing. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, & Applications, 35(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000342

- Boutet, I., LeBlanc, M., Chamberland, J. A., & Collin, C. A. (2021). Emojis influence emotional communication, social attributions, and information processing. Computers in Human Behavior, 119, 106722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106722

- Caspi, A., & Etgar, S. (2023). Exaggeration of emotional responses in online communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 146, 107818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107818

- Caspi, A., & Gorsky, P. (2006). Online deception: Prevalence, motivation, and emotion. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(1), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.54

- Cavalheiro, B. P., Prada, M., Rodrigues, D. L., Lopes, D., & Garrido, M. V. (2022). Evaluating the adequacy of emoji use in positive and negative messages from close and distant senders. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 25(3), 194–199. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2021.0157

- Choi, M., Budak, C., Romero, D. M., & Jurgens, D. (2021, May). More than meets the tie: Examining the role of interpersonal relationships in social networks. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (Vol. 15. pp. 105–116). https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/download/18045/17848

- Corbu, N., Oprea, D. A., Negrea-Busuioc, E., & Radu, L. (2020). ‘They can’t fool me, but they can fool the others!’ Third person effect and fake news detection. European Journal of Communication, 35(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120903686

- Danesi, M. (2017). The semiotics of emoji: The rise of visual language in the age of the Internet. Bloomsbury.

- Daniel, T. A., & Camp, A. L. (2020). Emojis affect processing fluency on social media. Psychology of Popular Media, 9(2), 208–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000219

- Derks, D., Fischer, A. H., & Bos, A. E. (2008). The role of emotion in computer mediated communication: A review. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(3), 766–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2007.04.004

- Dresner, E., & Herring, S. C. (2010). Functions of the nonverbal in CMC: Emoticons and illocutionary force. Communication Theory, 20(3), 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01362.x

- Erle, T. M., Schmid, K., Goslar, S. H., & Martin, J. D. (2022). Emojis as social information in digital communication. Emotion, 22(7), 1529–1543. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000992

- Flores-Salgado, E., & Witten, M. (2023). Illocutionary context and management allocation of emoji and other graphicons in Mexican parent school WhatsApp communities. Journal of Pragmatics, 210, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2023.03.013

- Ganster, T., Eimler, S. C., & Kramer, N. C. (2012). Same same but different!? The differential influence of smilies and emoticons on person perception. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour, and Social Networking, 15(4), 226–230. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0179

- Garcia, C., Țurcan, A., Howman, H., & Filik, R. (2022). Emoji as a tool to aid the comprehension of written sarcasm: Evidence from younger and older adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 126, 106971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106971

- Glikson, E., Cheshin, A., & Kleef, G. A. V. (2018). The dark side of a smiley: Effects of smiling emoticons on virtual first impressions. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(5), 614–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617720269

- Godard, R., & Holtzman, S. (2022). The multidimensional lexicon of emojis: A new tool to assess the emotional content of emojis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 921388. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.921388

- Hamdan, H. J. (2022). The communicative functions of emojis: Evidence from Jordanian Arabic-speaking facebookers. Psycholinguistics, 31(1), 141–172. https://doi.org/10.31470/2309-1797-2022-31-1-141-172

- Hand, C. J., Burd, K., Oliver, A., & Robus, C. M. (2022). Interactions between text content and emoji types determine perceptions of both messages and senders. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 8, 100242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100239

- Herring, S. C., & Dainas, A. R. (2020). Gender and age influences on interpretation of emoji functions. ACM Transactions on Social Computing, 3(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/3375629

- Holtgraves, T., Robinson, C., & Kaschak, M. P. (2020). Emoji can facilitate recognition of conveyed indirect meaning. PLOS One, 15(4), e0232361. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232361

- Hoorens, V. (1995). Self‐favoring biases, self‐presentation, and the self‐other asymmetry in social comparison. Journal of Personality, 63(4), 793–817. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00317.x

- Jackson, J. C., Watts, J., Henry, T. R., List, J. M., Forkel, R., Mucha, P. J., & Lindquist, K. A. (2019). Emotion semantics show both cultural variation and universal structure. Science, 366(6472), 1517–1522. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw8160

- Janssen, J. H., IJsselsteijn, W. A., & Westerink, J. H. D. M. (2014). How affective technologies can influence intimate interactions and improve social connectedness. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 72(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2013.09.007

- Jones, E. E., & Nisbett, R. E. (1972). The actor and the observer: Divergent perceptions of the causes of behavior. In E. E. Jones, D. Kanouse, H. H. Kelly, R. E. Nisbett, S. Valins, & B. Weiner (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 79–94). General Learning Press.

- Jones, L. L., Wurm, L. H., Norville, G. A., & Mullins, K. L. (2020). Sex differences in emoji use, familiarity, and valence. Computers in Human Behavior, 108, 106305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106305

- Kaye, L. K., Wall, H. J., & Malone, S. A. (2016). “Turn that frown upside-down”: A contextual account of emoticon usage on different virtual platforms. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 463–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.088

- Kelly, R., & Watts, L. (2015). Characterising the inventive appropriation of emoji as relationally meaningful in mediated close personal relationships. Paper presented at experiences of technology appropriation: unanticipated users, usage, circumstances, and design. https://purehost.bath.ac.uk/ws/files/130966701/emoji_relational_value.pdf

- Kim, S. J., & Hancock, J. T. (2015). Optimistic bias and Facebook use: Self-other discrepancies about potential risks and benefits of Facebook use. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(4), 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0656

- Koch, T. K., Romero, P., & Stachl, C. (2022). Age and gender in language, emoji, and emoticon usage in instant messages. Computers in Human Behavior, 126, 106990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106990

- Kralj Novak, P., Smailović, J., Sluban, B., Mozetič, I., & Perc, M. (2015). Sentiment of emojis. PLOS One, 10(12), e0144296.. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144296

- Kruger, J., Epley, N., Parker, J., & Ng, Z. (2005). Egocentrism over email: Can we communicate as well as we think? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 925–936. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.925

- Li, L., & Yang, Y. (2018). Pragmatic functions of emoji in internet-based communication: A corpus based study. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 3(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-018-0057-z

- Lo, S. K. (2008). The nonverbal communication functions of emoticons in computer-mediated communication. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 11(5), 595–597. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0132

- Locher, M. A., & Graham, S. L. (2010). Introduction to interpersonal pragmatics. In M. A. Locher, & S. L. Graham (Eds.), Interpersonal pragmatics (pp. 1–13). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Logi, L., & Zappavigna, M. A. (2023). A social semiotic perspective on emoji: How emoji and language interact to make meaning in digital messages. New Media & Society, 25(12), 3222–3246. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211032965

- Miller, H., Kluver, D., Thebault-Spieker, J., Terveen, L., & Hecht, B. (2017). Understanding emoji ambiguity in context: The role of text in emoji-related miscommunication. In Proceedings of the Eleventh Visual Communication Quarterly International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2017) (pp. 152–161). https://aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM17/paper/view/15703/14804

- Miller, H., Thebault-Spieker, J., Chang, S., Johnson, I., Terveen, L., & Hecht, B. (2016). “Blissfully happy” or “ready to fight”: Varying interpretations of emoji. In International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2016) (pp. 259–268). AAAI Press. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0179

- Prada, M., Rodrigues, D. L., Garrido, M. V., Lopes, D., Cavalheiro, B., & Gaspar, R. (2018). Motives, frequency and attitudes toward emoji and emoticon use. Telematics and Informatics, 35(7), 1925–1934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.06.005

- Pronin, E. (2007). Perception and misperception of bias in human judgment. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(1), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.001

- Riordan, M. A. (2017). Emojis as tools for emotion work: Communicating affect in text messages. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 36(5), 549–567. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X17704238

- Rodrigues, D., Lopes, D., Prada, M., Thompson, D., & Garrido, M. V. (2017). A frown emoji can be worth a thousand words: Perceptions of emoji use in text messages exchanged between romantic partners. Telematics and Informatics, 34(8), 1532–1543.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.07.001

- Sampietro, A. (2019). Emoji and rapport management in Spanish WhatsApp chats. Journal of Pragmatics, 143, 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.02.009

- Sampietro, A. (2020). Use and interpretation of emoji in electronic-mediated communication: A survey. Visual Communication Quarterly, 27(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/15551393.2019.1707086

- Schwartz, H. A., Eichstaedt, J. C., Kern, M. L., Dziurzynski, L., Ramones, S. M., Agrawal, M., Shah, A., Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D., Seligman, M. E., & Ungar, L. H. (2013). Personality, gender, and age in the language of social media: The open-vocabulary approach. PLOS One, 8(9), e73791. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073791

- Shaver, P., Schwartz, J., Kirson, D., O’Connor, C. (1987) Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1061–1086. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.52.6.1061

- Skovholt, K., Grønning, A., & Kankaanranta, A. (2014). The communicative functions of emoticons in workplace e-mails. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(4), 780–797. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12063

- Spencer-Oatey, H. (2005). (Im)Politeness, face and perceptions of rapport: Unpackaging their bases and interrelationships. Journal of Politeness Research, 1(1), 95–119. https://doi.org/10.1515/jplr.2005.1.1.95

- Spencer-Oatey, H. (2008). Face, (Im)politeness and rapport. In H. Spencer-Oatey (Ed.), Culturally speaking: Culture, communication and politeness theory (2nd ed., pp. 11–47). Continuum.

- Spencer-Oatey, H. (2011). Conceptualising ‘the relational’ in pragmatics: Insights from metapragmatic emotion and (Im)politeness comments. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(14), 3565–3578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2011.08.009

- Stark, L., & Crawford, K. (2015). The conservatism of emoji: Work, affect, and communication. Social Media & Society, 1(2), 2056305115604853.. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115604853

- Thompson, D., & Filik, R. (2016). Sarcasm in written communication: Emoticons are efficient markers of intention. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 21(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12156

- Togans, L. J., Holtgraves, T., Kwon, G., & Zelaya, T. E. M. (2021). Digitally saving face: An experimental investigation of cross-cultural differences in the use of emoticons and emoji. Journal of Pragmatics, 186, 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.09.016

- Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2011). Online communication among adolescents: An integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020

- Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer-mediated communication: Impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23(1), 3–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365096023001001

- Walther, J. B. (2011). Theories of computer-mediated communication and interpersonal relationships. In J. A. Daly, & M. L. Knapp (Eds.), Handbook of Interpersonal Communication (2nd ed., pp. 443–480). Sage.

- Walther, J. B., & D’Addario, K. P. (2001). The impacts of emoticons on message interpretation in computer-mediated communication. Social Science Computer Review, 19(3), 324–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/089443930101900307

- Weissman, B., Tanner, D., & Corcoran, C. M. (2018). A strong wink between verbal and emoji-based irony: How the brain processes ironic emojis during language comprehension. PLOS One, 13(8), e0201727.. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201727

- Wilks, S. S. (1935). The likelihood test of independence in contingency tables. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 6(4), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177732564

- Wilks, S. S. (1938). The large-sample distribution of the likelihood ratio for testing composite hypotheses. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 9(1), 60–62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2957648

- Wu, R., Chen, J., Wang, C. L., & Zhou, L. (2022). The influence of emoji meaning multipleness on perceived online review helpfulness: The mediating role of processing fluency. Journal of Business Research, 141, 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.12.037

Appendix

Instructions for participants in Study 2

Close Positive

You are asked to think about a person who is very close to you, and with whom you have a very close emotional relationship. This can be, for example, a family member such as one of your parents or your siblings, your partner, or a close friend. Now imagine for a moment that you have scheduled a meeting later this week and you want to send him/her a message expressing your excitement and expectations for your meeting. Please compose a message that is as similar as possible to what you would normally write in terms of the number of words and/or symbols, the punctuation, or any other aspect for expressing the idea that you are excited and looking forward to your meeting.

Close Negative

You are asked to think about a person who is very close to you, and with whom you have a very close emotional relationship. This can be, for example, a family member such as one of your parents or your siblings, your partner, or a close friend. Now imagine for a moment that you scheduled a meeting later this week and you want to send him/her a message expressing your anger at the cancellation of this meeting. Please compose a message that is as similar as possible to what you would normally write in terms of the number of words and/or symbols, the punctuation, or any other aspect for expressing your disappointment and anger following the cancellation of your meeting.

Distant Positive

You are asked to think about a person who is very distant from you and with whom you do not have any close emotional relationship. This can be, for example, a study partner, a work partner, your neighbor, or even a seller at the supermarket. Someone you know, but with whom you have no close emotional ties. Now imagine for a moment that you have scheduled a meeting later this week and you want to send him/her a message expressing your excitement and expectations for your meeting. Please compose a message that is as similar as possible to what you would normally write in terms of the number of words and/or symbols, the punctuation, or any other aspect for expressing the idea that you are excited and looking forward to your meeting.

Distant Negative

You are asked to think about a person who is very distant from you and with whom you do not have a very close emotional relationship. This can be, for example, a study partner, a work partner, your neighbor, or even a seller at the supermarket. Someone you know, but with whom you have no close emotional ties. Now imagine for a moment that you scheduled a meeting later this week and you want to send him/her a message expressing your anger at the cancellation of this meeting. Please compose a message that is as similar as possible to what you would normally write in terms of the number of words and/or symbols, the punctuation, or any other aspect for expressing your disappointment and anger following the cancellation of your meeting.