Abstract

This research incorporates previous surveys on real estate education with an eye on the future of real estate education in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, also referred to as the Industry 4.0, the digital age, or several other technology-related terms. Additionally, this research is an update to an earlier survey of graduate real estate programs administered after the Great Recession. Over the last decade, there has been a large amount of research suggesting that the real estate educational community may not be adequately preparing its professionals to deal with rapid changes in tenant dynamics, customer demographic shifts, and disruptive technology, such as automation and artificial intelligence applied to real estate processes currently occurring in the real estate marketplace. This is especially true in terms of the ever-increasing demand for better data and faster data access to determine optimal service levels and amenities. Building on a modified survey originally administered in 2014, this survey was administered during the first quarter of 2019 and sought to determine how changes in the industry may or may not have impacted graduate real estate programs. These impacts may include any changes in the material taught and the skill sets conveyed in the graduate real estate curricula. This paper reviews literature and provides the results of the recent survey administered to the professionals directing and/or teaching in numerous graduate real estate programs. Where possible, some general comparisons are discussed between the 2014 and 2019 survey responses to highlight trends. The results of this research highlight what courses and skills are presently considered the most important in real estate curricula to educate students to be successful in an ever-changing, fast-paced industry.

Keywords:

Over the past three decades, there has been an ongoing debate between the real estate industry and academia focused on which essential skills are needed by graduate real estate students to be successful in their professional careers (Chambers et al., Citation2009; Galuppo & Worzala, Citation2004; Miller & Weinstein, 2006; Saginor et al., Citation2014; Weinstein & Worzala, Citation2008; Worzala, Citation2003; Worzala & Chambers, Citation2006). The gap between real estate education and the real estate profession has always existed, and the profession tends to change faster than education can incorporate and adapt to these changes.

This research adapts an earlier survey of graduate real estate programs to determine how changes in the industry may or may not have influenced graduate real estate programs over the last five years (Saginor et al., Citation2014). Questions included which changes have been made in the material taught and the skill sets focused on currently in graduate real estate curricula in the United States as they relate to technological disruption in the real estate profession. The previous study surveyed directors of graduate real estate programs, concentrations, and certificates to determine if and how the Great Recession affected their programs. The results indicated that although real estate programs have faced an incredible amount of turmoil over the last decade, the academic field of real estate continues to lack a widely recognized, common body of knowledge that constitutes the core theory and concepts.

This paper reviews the results of the new survey administered specifically to the professionals directing and/or having some sort of administrative role in these graduate real estate programs. The results of this research highlight what core competencies and skill sets are presently considered the most important in real estate curricula to educate students to be successful in the industry now and in the future.

Literature Review

The literature for graduate real estate programs normally follows two underlying themes. In one approach, the research focuses on improving the education process and the fundamental methods for working with graduate students. This approach is largely internally driven in terms of how the program functions. In the other approach, the research emphasizes improving the knowledge base of students and the direct connectivity between academia and the business community. This approach is externally driven and tied to minimizing the knowledge gap between academia and the profession. In practice, all programs have some combination of internally and externally driven factors.

Much of the literature originally discussed in the 2014 survey article is summarized before more recent literature is discussed in depth. What should be taught in real estate programs ranges from the importance of writing skills and teamwork to the inclusion of active learning in solving issues in real estate (Gibler, Citation2001; Wolverton & Butler, Citation1997). Other approaches focus on bridging the gap between the classroom and boardroom with either real-world case studies or better connections to industry (Anderson et al., Citation2000; Butler et al., Citation1998; Chambers et al., Citation2009; Galuppo & Worzala, Citation2004; Hardin, Citation2001; Manning & Roulac, Citation2001; Tu et al., Citation2009; Worzala & Chamber, 2006). Despite these efforts to bridge the gap, several other studies highlight that these approaches may fall short (Bennis & O’Toole, Citation2005; Urban Land Institute, Citation2003). A few studies also find that it is important for programs to better intertwine industry and academia through mentoring and internships (Weinstein, Citation2002; Weinstein et al., Citation2007). It is also clear that these issues are not unique to programs in the United States as much of the international literature on real estate programs finds similar issues with graduate real estate education (Baum & Lizieri, Citation2002; Schulte, Citation2002; Schulte et al., Citation2005).

More recent research focuses on the broader characteristics of programs, such as branding. A survey of 102 real estate professionals in Singapore reveals important characteristics required in a graduate real estate program (Ooi and Yu, Citation2011). The three most important criteria were quality teaching, branding and reputation, and relevant course curriculum. Teaching quality involves instructors who possess relevant field experience and are able to stimulate interest and actively engage in soliciting class participation. Institutional branding and reputation highlight the difficulty experienced by new schools to raise awareness that well-established, branded institutions might not face. With respect to program content, the respondents liked curricula that were more practice-oriented and focused on innovations and developments in the field as well as international best practices. Surprisingly, academic qualifications, research achievements, international reputation of the professors, and academic rigor of the course content were all items that were not particularly important to the respondents. This suggests that the respondents were more interested in how new knowledge could be applied in their day-to-day work situations, rather than just learning about theories and principles in the classroom (Ooi and Yu, Citation2011).

Three interrelated studies by Poon (Citation2012, Citation2014) and Poon et al. (Citation2011) detail findings from a funded study on real estate programs in U.K. universities. These studies focus on the existence of disparities between professional practice firm employers' expectations of real estate graduates, real estate graduates' perceptions of what was learned, and universities' views of the content of Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) accredited real estate courses. The studies find that top employer-rated knowledge and skills were present in most of the programs studied. The faculty and university administrators argued that there was little that real estate educators could do to change a student’s personal attributes. One area where employers clearly felt graduates had more knowledge than needed was in research methods. Both groups indicated that practical experience was largely missing from courses but most of the university-based respondents did not view this as their responsibility. The RICS-accredited course directors mentioned that they provide alternative simulated work experience for students. Human resource managers identified the key employability skills for real estate graduates as soft skills, specifically report writing skills, communication skills, presentation skills, client care, and professional standards. The human resource managers of real estate consultancy firms also voiced their concern regarding graduates’ lack of commercial awareness.

Jayantha and Chiang (2012) focus on determining what constitutes successful real estate education based on student feedback. They surveyed 133 graduate real estate students in Hong Kong. The survey clearly reveals that real estate-specific courses such as real estate development, real estate economics, finance, and investment, and real estate principles/markets were the most important subjects in a successful graduate real estate curriculum. Relevant industry experience and good communication and interactive skills were the most desired faculty attributes, while visiting professors from overseas and from Mainland China were considered the least important attributes on the list. These results are not surprising because local instructors with industry experience are generally better equipped with the latest local knowledge and expertise about the industry. When queried about selecting a school, respondents stated that strong links with the industry network and the reputation of the university were the most important elements, while the program cost was the least important. Similarly, opportunities to attend professional meetings and to have plenty of courses to choose from were clearly important to the respondents. As for classroom teaching, case study-based teaching was at the top of the list, followed by guest lectures by industry practitioners. Similarly, being practical in orientation, integrated with new developments in the field, and including international coverage in the courses were all important elements for a successful graduate real estate program.

A study by Worzala et al. (Citation2013) in the United States explores the dramatically changing landscape of compensation for recent graduates of MS and MBA real estate programs after the Great Recession. Before the crisis, graduates of these programs were in very high demand and they were commanding extremely high compensation packages. A survey of alumni from U.S. graduate real estate programs composed of “recession-era” graduates (2008-2010) and “pre-recession” graduates (2000-2007) provided real estate educators with some background on the changing types of jobs available to recent graduates as well as the changing structure for salaries, bonuses, and other benefits. The survey also identified the types of companies and the real estate sectors that were hiring the respondents. The most significant part of the results confirmed the perception that after the Great Recession, graduates were moving into a more diverse set of jobs, it took them much longer to find a job, and there was a downward adjustment in compensation packages.

Charles (2016) explores the potential for using the Urban Land Institute’s (ULI) Hines Student Competition as a pedagogical tool in teaching real estate development. The ULI Hines Student Competition is a promising tool for conveying experience-based, tacit knowledge of real estate development within a graduate real estate curriculum. The competition provides a complex, well-organized problem that can be used as the focus of a graduate course, requiring students to address the interrelated issues of market analysis, urban design, and finance. The structure of the competition, as designed by ULI, offers many of the benefits of collaborative pedagogical techniques, such as team-based and problem-based learning. It fosters multi-disciplinary teamwork and a competitive spirit among students, which may inspire them to do their best work. In addition, the overarching goals and intent of the competition have remained quite consistent over the years, enabling the instructor to establish and maintain overall learning objectives for the course. The competition course could be improved through the greater facilitation of team formation in the semester preceding the competition. In particular, one recommendation is to make a special effort to recruit students with design skills. Although conducting research concentrated on the specific project site is not possible in the weeks preceding the start of the competition, the time leading up to the competition could be productively used helping students learn teamwork strategies and preparing them for the work ahead. Another recommendation was a mid-competition critique with faculty and advisors to help students refine their projects. Additionally, requiring check-in meetings at strategic moments during the competition to ensure that teams are on schedule to submit complete entries by the competition deadline is also important. Overall, the ULI Hines Competition course at Cornell was successful; students strongly agreed that the competition course was a valuable learning experience.

Poon (Citation2016) and Poon & Brownlow (Citation2016) shift the emphasis to real estate graduates and employment in Australia. One major finding from the first study was the importance of English proficiency for graduates to get a job within the real estate profession. In addition, the authors found that age and attendance had no statistically significant impact on employment outcomes. However, these attributes did have an important impact on employment patterns. In the second study, the authors examined the gender of real estate graduates. In this case, the researchers found that male students were more likely to gain full-time employment. Additionally, the roles were substantially different, with females gaining employment in secretarial or administrative roles while the males typically had a professional or technical role that was also tied to a higher salary. Gender also had an impact on the contract type of the graduates with males much more likely to get a permanent employment contract. The findings reinforce much of the previous literature that found that male graduates have more favorable employment outcomes with better employment terms.

A recent study by Amidu et al. (Citation2018) also attempts to explore gaps between real estate curriculum and industry needs in the United Kingdom. By employing a mapping technique across four universities, they identified some key areas for educational reform in the U.K. Data for the study was collected through a desktop review of real estate curriculum from four randomly selected universities and analyzed using a mind mapping approach. The study revealed that although knowledge from real estate academic curriculum aligns with the industry in six out of nine knowledge base areas, there were gaps in the three areas considered most significant to the needs of industry. The six areas that matched best with industry were valuation, construction/sustainability, planning/property development, real estate/property management, real estate investment/finance, and research. The three areas showing gaps between academia and the profession were professional practice, business operations, and law. Results indicate that the gap between industry and academia is real and that in some cases faculty may be focusing on areas that are not that useful or necessary for success in the real estate profession, requiring the industry to complete on the job training for graduates from real estate programs.

Another study conducted by Azasu et al. (Citation2018) evaluated South African stakeholder views of the content of recently developed postgraduate course in Facilities Management at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa. As with some of the earlier studies, a questionnaire was administered to a cross-section of professionals registered with the South African Facilities Management Association (SAFMA). Questions covered technical, personal, interpersonal, and professional skills as well as the ability to conceive, design, implement and operate business systems. Results also highlighted the degree of importance of each skill. The paper goes beyond previous research in the built environment in specifying the requisite proficiency levels in terms of the relevant skills and competencies.

Finally, a study conducted by Kane et al. (Citation2018) discusses the lack of technological skills taught in business schools based on Deloitte’s 2018 Commercial Real Estate Outlook. The study concludes that although executives across industries and around the world are investing in the digital maturity of their organizations, the real estate industry and real estate education programs may not be preparing students adequately for industry changes. As a result, the real estate industry is on an accelerated disruption curve emphasized by rapid changes in tenant dynamics, customer demographic shifts, and ever-increasing needs for better and faster data access to allow improved service and amenities.

Survey Background, Methodology, and Results

Similar to the 2014 survey, multiple methods were used to find real estate graduate programs, concentrations, and/or certificates. The first step was crosschecking the survey recipients from 2014 to determine which programs still existed in 2019. In addition to this step, the ULI 2019 Urban Land University Education Programs was used to help create the list of programs. It should be noted that this resource used to be more comprehensive. Currently, a program must pay to be part of the ULI guide. Many programs do not have large marketing budgets and/or opt not to pay. Additional sources used to confirm the existence of graduate real estate education offerings included RICS certification, the National Association of Realtors Directory of University & College Research Centers, and phone calls or website visits to university web pages. In 2014, there were 65 possible graduate survey respondents, including 41 real estate programs, 15 real estate concentrations, and nine real estate certificate programs. For the 2019 graduate survey, there were 70 possible respondents covering 41 real estate programs, 22 real estate concentrations, and five real estate certificate programs.

Many programs included in this study offer multiple real estate educational offerings, meaning that a single program can have a full-fledged master’s degree, a master’s concentration tied to an MBA or similar program, and a graduate real estate certificate. To the greatest extent possible, these graduate real estate offerings were examined online to determine the best person or people to contact regarding the survey. The goal was to minimize the likelihood of duplication by having only one response per unique program.

This survey was administered from early February to early March of 2019 using Survey Monkey. This window of time was chosen to ensure that most programs had their winter or spring semesters underway, but had not yet had their spring break. While there is no optimal time to administer an academic survey, our previous experience in 2014 demonstrated that this time might be better than other times of the year. The survey was emailed on February 11, and a majority of the responses were received during the first week. Follow-up reminder emails were sent once a week, with the final reminder sent on March 5, 2019.

The survey included the following language, beyond the required IRB language, to introduce and provide some context regarding the purpose of the survey:

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, also known as Industry 4.0, is largely tied to concepts such as digitization and automation. While these concepts may not be a core competency in graduate real estate programs, these concepts are transforming the real estate workplace. Several reports and surveys exist that discuss changes in the workplace, but there is little to no data in terms of how graduate programs are adapting to these workplace changes. The purpose of this survey is to evaluate where graduate real estate programs are today based on industry changes. Several of these questions focus on current conditions in your program.

To that extent, the tail end of the survey focused largely on how aware real estate programs were of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Compared to the 2014 survey covering the Great Recession, which was largely backward looking, the concluding questions on this survey were largely forward looking in terms of industry and workplace trends related to technological advances.

Of the 61 recipients of the survey, 47 recipients (77%) opened the survey, with 13 recipients (21%) not opening the survey, and one recipient (2%) opting out of the survey. 30 recipients (49%) clicked through the survey. Despite the number of recipients that opened and/or clicked through the survey, only 26 respondents or 43% answered some of the questions. These results are somewhat lower than the 2014 survey, when the response rate was 59% and 33 programs responded. Of the 26 respondents, 77% completed the entire survey and 23% completed most of the survey with the exception of a few questions, mostly toward the end of the survey. These responses are the ones included in the results section. The responses were anonymous with the exception that, on the last question, permission was asked to use the respondent’s name for attributing quotes from open-ended questions in the survey. Additionally, if there was any need for follow-up with the response, this provided an opportunity to do so given the anonymity of the survey.

The survey had 29 questions and took an average of 12 minutes to complete. The front end of the survey included four questions detailing the role, background, and experience of the respondent. These questions were followed by four questions regarding the program’s typology, delivery, and duration. The central survey questions revolved around the knowledge areas of the program, the skills taught within the program, the types of students, and the real estate areas where those students eventually get jobs. The last four questions of the survey tied current real estate education to the Fourth Industrial Revolution and innovative industry trends that are likely to become the rules of the future workplace. Respondents were allowed to skip any questions they preferred not to answer, likely accounting for the partial responses.

Respondent Characteristics

One of the most obvious differentiators regarding graduate real estate education offerings was the background of the person in charge of the program, concentration, and/or certificate. The first question regarding the other titles held by the respondent demonstrated that there was no single combination of roles prevalent regarding program leadership (). 75% of respondents were either full professors (46%) or associate professors (29%). In addition to these roles, respondents were also likely to be a department chair/director/head and/or hold an endowed chair. Other possible roles the respondent held included lecturer, clinical or executive lecturer/professor, and related roles. In a few cases, the respondent had an administrative role within the program.

Table 1. Profile of survey respondents (n = 24).

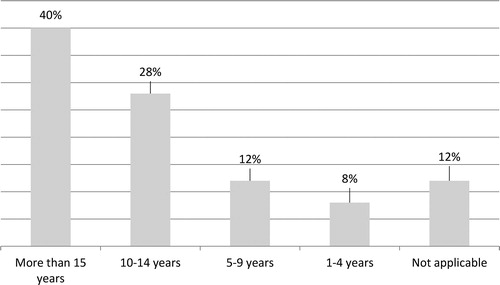

The respondent was more likely to be male (76%) than female (24%). Despite the fact that 18 respondents listed that their rank was tenured based on being a Full Professor or Associate Professor, only 15 respondents stated that they were tenured. Nine respondents stated that they did not have tenure, indicating that some directors were employed on annual or multi-year contracts. Despite the various backgrounds, a majority (80%) of the respondents had been involved with real estate programs for at least five years, with the largest segment (40%) having spent more than 15 years in their real estate program (). This percentage is similar to the results of the previous survey, where 42.4% of respondents reported having more than 15 years of experience. In the case of three respondents, this question was not applicable, indicating that their role was solely administrative and there was no teaching associated with their duties.

Real Estate Program History, Typology, and Duration

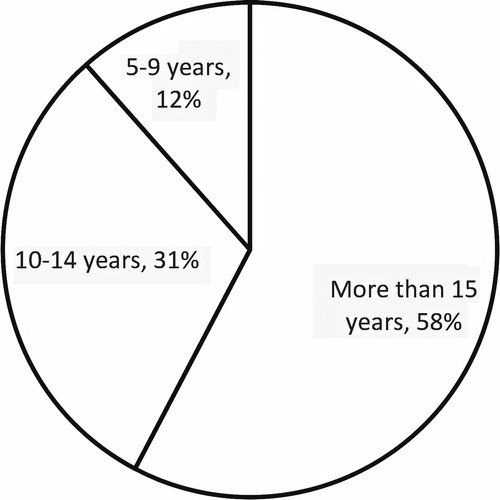

When the authors administered a similar survey in 2014, nearly a quarter of all program respondents were in a program that was less than five years old. Five years later, no respondents listed that their program was less than five years old (). Similar to the tenured status of the person running the real estate offering, a majority of respondents stated that their program was more than 15 years old. These responses indicate that tenured professors, usually full professors, run many of the long-standing real estate programs. In some cases, the person running the program may have also been the founder of the program. For future surveys, researchers may want to consider a category of “founder.”

Fifteen of the programs have a history of more than 15 years, with another eight programs having a history dating back 10 to 14 years. Only three of the responding programs have been in existence for less than 10 years.

The type of real estate program, despite some variation, was largely a program that was part of a business school (62%, as detailed in ). In terms of stand-alone real estate programs, which constituted the largest segment of survey respondents, a majority (74% of 2019 respondents compared to 46% of 2014 respondents) were located in business schools, while 26% (compared to 30% of 2014 respondents) were not in a business school. Only three programs with concentrations responded to the 2019 survey compared to five programs with concentrations from the 2014 survey.

Table 2. Respondent by type of real estate program (n = 26).

For the “Other” category, almost all of the respondents indicated a program, concentration, or certificate that was jointly offered with another degree, such as law. Again, future research might want to consider including an option for stand-alone real estate programs, concentrations, and/or certificates offered in more than one school to reflect the multidisciplinary nature of these programs.

The seventh question on the length of the various real estate programs proved problematic to analyze, especially for real estate programs that have multiple offerings, such as a degree, concentration, and certificate. Despite these issues, two lessons learned from the 2014 survey provided new insight to the duration question in adding “rolling admissions” and “varies—pace depends on the student” categories to this question ().

Table 3. Duration of real estate program (n = 26).

The largest number of respondents have real estate offerings that can be completed on a full-time basis in at least 12 months (42%) followed closely by programs with a 13- to 18-month duration (29%) and a 19- to 24-month duration (25%). Compared to results from the 2014 survey, real estate programs are trending toward a shorter completion time for full-time students, with many programs that were formally two-year programs being shortened to 18-month programs or shorter. Offering these shorter programs means having the faculty and resources to offer the classes needed regularly and/or more often to shorten program durations. Additionally, most full-time programs that can be completed in 10-12 months are also cohort programs (90%). For part-time students, either the pace varies (44%) or the program is designed to be completed in 19-24 months (31%). For programs with rolling admissions, there were no respondents that stated that the program could be completed in a year, with the largest segment (60%) responding that the time to completion varies largely based on the pace of the student.

In terms of course delivery, despite the proliferation of internet-based everything, real estate programs are still largely offered in-person. Only 23% of respondents indicated that their programs were available either fully or partially online. 77% of respondents stated that their program had no online courses. Despite several non-academic real estate offerings being available online, traditional academic real estate offerings are still largely held in a traditional classroom setting.

Student Services and Skill Sets

Based on open-ended comments received from the 2014 survey, the 2019 survey questions related to student services and skill sets were expanded from seven to twelve options. Even with these expanded options, some of the open-ended responses revolved around having a strong, long-standing connection with the local and regional real estate community. The three highest rankings—networking with alumni and/or real estate professionals, mentoring by industry professionals, and internships—are all interconnected to some extent (). Networking with alumni and real estate professionals can lead to internships, and possible mentoring by industry professionals while on the job. Additionally, for students working full time, the internship may not be necessary, so mentoring and networking could lead to a better job or a better network. Mentoring by industry professionals ranked highest in the 2014 survey, while networking and internships were not options.

Table 4. Student services and their importance in relation to future employment (n = 26).

Following the top three answers was familiarity with industry-specific software. This response is discussed in more detail in the next two tables ( and ). Familiarity in this response likely means the ability to verbalize knowledge of industry-specific software to demonstrate competence. Participation in professional conferences, such as ICSC, NAIOP, NAR, and ULI ranked just behind familiarity with software, and was followed by having a career advisor specializing in real estate. Despite Charles’ (2016) discussion of the ULI Hines Competition serving as a pedagogical tool, respondents did not rank it highly in terms of importance tied to future employment. The bottom five responses are related to workshops, job fairs, and online or printed resumes. These bottom five responses demonstrate that finding a job in real estate, much like success in real estate, is based on building relationships and networks rather than workshops and online/print resumes. Moreover, the 2019 results largely reinforce the 2014 results, with online resume and printed resume book ranking at the bottom, below workshops.

Table 5. Most important skills and competencies for employment (n = 25).

Table 6. The right tools for the job (n = 23).

While there may be no single most important factor between student services and securing future employment, real estate educators may need to pursue multiple strategies to maximize employment opportunities for their students. Ultimately, it is up to the student to obtain employment, and many students can get jobs based on their own personal networks. For students that do not have these networks, there are a variety of ways to foster the creation of these personal networks including networking, mentoring, internships, and attending conferences.

In terms of getting a real estate job, the next question sought to isolate the most important skills required. The 2014 survey did not include networking as an option, and the top five answers in the 2019 survey were similar. Not surprisingly, analytical problem solving related to a wide range of real estate problems ranked the highest at 1.13 just as it ranked highest in the 2014 survey (). This response was not completely surprising, and the responses gauged whether it was more important to have a wide range of problem-solving skills as opposed to a narrowly tailored set of skills related solely to financial analysis. Quantitative and financial analysis skills were ranked fourth, behind oral communication skills and networking. In comparison to the 2014 survey, the one difference is that oral communication skills were ranked slightly higher.

In an ironic twist, the ability to work in teams and the ability to work individually had the exact same ranking, whereas the 2014 results were 0.03 apart based on the respondent rankings. This response was important because it reinforces the need to be team-based while also being able to provide something as an individual embedded in a team. While this response might not be groundbreaking, the fact that the scores were the same in 2019 and extremely close in 2014 in a survey of real estate programs emphasizes this point. Lower-ranked responses relate largely to courses that might be taught in a real estate program, but are secondary skills and competencies compared to the highest ranked skills. However, it should be noted that respondents found all of the skills listed to be either “very important” or “important” for the students to have.

Based on skills and competencies, there are certain technical tools required for real estate success on the job. Not surprisingly, financial modeling using Excel ranked highest, followed by ARGUS (). Despite ARGUS becoming increasingly common, it is essentially a black box that requires putting in the right input to get the right output. If a student can create financial models in Excel, the student has a much better grasp of the theory and practice related to real estate, while ARGUS may add a little bit of mystery to the process. The issue, as with any pre-packaged program, is whether the students understand real estate finance or whether they understand how to use the software. Ideally, the key is for students to be able to model in Excel so that they have enough knowledge to successfully use and understand ARGUS and overcome any limitations that may exist with the software.

Of the remaining ranked tools, only GIS can be considered comparable to financial modeling using Excel. In other words, CoStar and similar programs essentially use GIS as a way to spatially show data. Given CoStar’s growth and acquisition of similar data warehousing companies such as LoopNet, it is not surprising to see it ranked highly among respondents. In the open-ended responses, many respondents stated that the list of tools are becoming more interchangeable, so it is difficult to rate one tool higher than another because both may be needed to analyze real estate. Other databases, such as Real Capital Analytics (RCA), CoreLogic, and government databases were also suggested in the comments.

A follow-up, open-ended question asked respondents to list the top three skills their graduates needed to get a job or obtain a better job. While only 15 respondents answered this question, 60% listed financial modeling/Excel/Argus as their top answer. The other 40% of responses ranged from networking to presentation skills. Overall, almost all of the top three skills listed fell into one of two categories: internal knowledge or external communication. To summarize, getting a job in real estate is a combination of “what you know” and “whom you know.” Beyond that aspect, the more important skill is ensuring that whom you know is confident in what you know.

Student Employment During and After Graduation

Given that real estate education should provide students with enough skills to gain employment, follow-up questions asked how long it took students to get full-time jobs. Additionally, given that many students might work full-time to pay for school, either on their own or through a reimbursement program from their employer, a question was asked to determine whether students in the program were already working full-time while they were taking their classes. In terms of full-time students that work, the responses highlighted that real estate programs tend to have a diverse student body in terms of employment (). The largest response suggested that somewhere between 1% and 25% of students work full-time throughout school. Despite this relatively low number, the second and third highest responses showed that large segments of students are likely to work either full- or part-time while attending school.

Table 7. Percentage of full-time students working while in school (n = 23).

These results are quite different from the 2014 survey results. In 2014, 30% of respondents stated that 51%-75% of their students were working full-time, compared to 13% of 2019 respondents. Additionally, although not as starkly different, 27% of respondents said more than 75% of their students worked full-time versus 21% of respondents in the 2019 survey.

For students not already working full-time, three follow-up questions were used to determine whether students obtained full-time employment upon graduating, within three months of graduating, or within six months of graduating (). In addition to these responses, there were at least five respondents for each question that responded, “We do not track this information.”

Table 8. Percentage of students obtaining full-time employment within a program (n = 22).

Most students obtained jobs within six months of graduating. Despite a vastly improved economy since 2014, the percentage of students obtaining full-time employment within six months of graduation did not differ greatly. One interesting thing to note is that due to resource constraints and other possible issues, many of the respondents indicated that they do not track how quickly their graduates obtain employment. Keeping track of this data can be difficult as graduates scatter after graduating and obtaining employment information becomes more complex once a student graduates unless there is a strong, established line of communication and connection between the student and the program.

Once these students graduate, for programs that track the data, a question was asked regarding the employment area where the largest percentage of students eventually started working or continued to work if they worked full-time throughout school. The 2014 survey only included eight options, and based on open-ended responses to the previous survey, nine additional options were included for the 2019 survey (). Despite the inclusion of previous suggestions, many of these job categories for largest percentage of students resulted in no responses.

Table 9. Real estate employment (n = 20).

The largest category of jobs where students eventually worked was in real estate development, followed by commercial real estate and real estate finance. These answers, while not necessarily noteworthy, demonstrated that real estate students are largely getting the jobs they should be based on their education.

While they are getting jobs, what are the underlying reasons as to why students ultimately take a job, irrespective of the job type? This question, as well as the remaining discussion of the survey here, is based on questions not previously asked in the 2014 survey. Traditionally speaking, the ultimate reason for taking a job tends to be salary, based on informal discussions with students. In posing this question to respondents, though, reputation ranked highest, with salary ranking closely behind ().

Table 10. Student choice of jobs by criteria (n = 19).

Other reasons for why a student ultimately chose a job included corporate culture and opportunities for formal or informal learning. Less important reasons for choosing a job (although the mean ratings are still in the significant range) included diversity and inclusion as well as community engagement and volunteering opportunity. Despite recent trends toward flexibility in hours and the ability to work remotely, these reasons were viewed as being some of the least important reasons for students to choose a job.

Job Trends and Program Economics: Wants vs. Needs

The last round of questions aimed to probe the minds of respondents relating to current trends in technology. They were also designed to highlight how their educational programs might be altered to better prepare students for their professional careers. Part of preparing for changes, however, requires an understanding of whether any trend exists. An open-ended question was asked regarding whether the respondent was aware of any recent trends regarding education of real estate graduate students. Less than half of respondents answered this question. Despite the low response rate, several responses reinforce the recovery in the real estate job market since the Great Recession. Evidence of this recovery, beyond market data, include anecdotal data ranging from the availability of many jobs in general to many jobs in specific areas such as real estate development. Another sign of recovery is the growth of jobs in the residential real estate sector, including the private sector, public sector, and non-profit sector.

A follow-up question asked whether the respondent planned to make any changes to their real estate education offerings in response to any perceived trends. Many respondents mentioned the cyclical nature of real estate and the importance of continuing to offer a strong, basic foundation of knowledge to ensure students can land jobs in any type of economy. These responses indicate that, to some extent, respondents view current trends as fads. Rather than chasing fads, continuing to focus on the basics appears to be more important. Multiple responses mentioned the need for fine-tuning in terms of whether course delivery should be online or traditional, as well as how to better incorporate certain areas of real estate into existing coursework. While several responses mentioned data analytics and technical skills, most of these responses were broad in terms of discussing what they plan to do without mentioning how they plan to do it.

Another follow-up question was included, providing the respondent with the hypothetical control to make changes to improve the overall quality of education offered to real estate students. To a great extent, program management could be compared to poker, with respondents adapting to situations based on the cards they are dealt, but without an option to fold. Answers to this question focused on measuring what type of “more” respondents may want, such as more funding, more scholarships, more faculty, or more course offerings. The “more” answers were extremely diverse, ranging from more full-time faculty lines and more industry interaction to more online course offerings, more offsite opportunities, more Excel in the classroom, and the ability to offer more electives. In terms of responses asking for more funding, most of the responses tied more funding to the recruitment of top-tier students.

Aside from the “more” responses, many respondents also had “better” responses. A few responses called for better students, either through higher standards or by gauging their ability to succeed in the program as soon as possible to minimize the need to adjust the curriculum. From the perspective of better courses, the responses ranged from offering better core or electives that address financial analytics, technology, modeling, data analytics, and demographic and/or geographic software programs.

Based on the previous question, a follow-up question asked respondents to state their greatest program need. There were only 11 responses, and of these responses, scholarship funding had the largest number of responses (4), followed by the need for tenured or tenure-track faculty (3). The remainder of responses ranged from space issues to better support from the university.

Preparing Students for the Fourth Industrial Revolution

After a brief definition of the Fourth Industrial Revolution was provided to respondents in the introduction to the survey, they were asked how prepared their students were for the new technologies that are flourishing in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Only three respondents felt their students were very prepared while the majority (56%) felt that their students were prepared ().

Table 11. Student preparedness for the fourth industrial revolution (n = 18).

Three respondents were uncertain, and of the two other responses, one response said that the students were prepared, but that they need to be more prepared for the future. The number of respondents who skipped this question, as well as the number of respondents stating that their students were neither prepared nor unprepared may demonstrate that, despite a definition, respondents may be unclear about what the Fourth Industrial Revolution entails for their students or their programs. Irrespective of the definitional issues, not a single respondent felt that their students were either unprepared or very unprepared for the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

After the question on preparedness, another question asked how the Fourth Industrial Revolution has changed the needs of students to meet the changing workplace. Interestingly, the answers to this open-ended question highlighted two things: uncertainty and figuring out how to better incorporate technology into current or future courses. The uncertain responses applied to two types of uncertainty: uncertainty regarding the concept of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and uncertainty related to whether the needs of students have changed. To some extent, answers to these questions may be more apparent in the future, as industry requires real estate education to change to meet employment requirements.

In terms of technology, the responses could be assigned to one of two categories: understanding data availability and having the technical skills needed to analyze and process the data. Across these two categories, though, there is a common issue: offering additional courses may affect the number of courses a student has to take based on university requirements. More flexibility related to substituting classes may be one way to address this issue without affecting the time it takes a student to complete a program. Overall, respondents felt it was important to stress technological impacts and skills within the current curriculum, essentially incorporating the changing nature of technology into the existing fundamentals regarding real estate education.

The Most Surprising Finding: Ethical Implications for the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Respondents were also asked the following question: Despite the Fourth Industrial Revolution appearing to be a work in progress regarding impacts on real estate education, what is the most important thing we can teach future members of the real estate community? Despite not appearing elsewhere in the survey as a specific question, the largest number of responses focused on ethics. This response was surprising and only found in this question; ethics did not appear as a response in any other area of the survey. Of the 11 respondents who provided an answer, seven responses had some connection to ethics and integrity. Despite all the changes that might arise in the future of real estate education, technology appears to not be nearly as important as ethics and integrity. This unexpected response demonstrates that real estate programs may still be reacting to the perceptions generated about the profession in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Rather than looking forward to trends related to the Fourth Industrial Revolution and its impact on education, looking backward provides insight on how to better address the past. Emphasizing ethics and integrity, while an important aspect of real estate certifications and, perhaps indirectly, viewed as important in the industry, the Great Recession may have resulted in emphasizing the need to walk the walk more rather than just talking the talk. The importance of ethics and integrity, therefore, is likely to be an ongoing topic in both education and the industry.

Conclusions and Areas of Future Research

The role of rapid advances in technology regarding automation and digitization in the evolving workplace appears to be a concept with little understanding and even less incorporation into graduate real estate programs. While there was some hesitance or uncertainty about the future trends and role of technology, including some questions as to whether the Fourth Industrial Revolution was a marketing buzzword, it is clear that the real estate industry has changed greatly over the past few years. This change and rapid evolution will continue in the future, and the professional workplace will adapt to these changes to maximize opportunities. While the current state of graduate real estate education may not adapt as readily, industry will likely force real estate education to change, enabling students to maximize these opportunities. The more flexible graduate real estate education can be to adapt to these rapid changes and maximizing opportunities, the better off the students and programs will be in addressing the Fourth Industrial Revolution. However, at the current pace, and reflecting decades of real estate research, the gap between the real estate profession and graduate real estate education will likely continue, and the goal of graduate real estate education will continue to be finding innovative ways to minimize this gap in the future.

As with all research, there are limitations to this study. Perhaps the most significant limitation is that it is an anonymous survey that does not allow us to tie programs to responses so that direct conclusions regarding the focus of the program and whether that focus is tied to the future careers of the graduates can be made. Additionally, this survey only focused on graduate real estate programs in the United States as opposed to international graduate real estate educational officers. This research was limited to U.S.-based graduate programs and only surveyed the program leadership, not the students or their employers. These limitations would all be important extensions for future research to better understand the current state of graduate real estate education, as well as its future.

References

- Amidu, A., Ogbesoyen, O., & Agboola, A. O. (2018). Exploring gaps between real estate curriculum and industry needs: A mapping exercise. Pacific Rim Property Research Journal, 24(3), 265–283.

- Anderson, R. I., Loviscek, A. L., & Webb, J. R. (2000). Problem-based learning in real estate education. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 3(1), 36–41.

- Azasu, S., Adewunmi, Y., & Babatunde, O. (2018). South African stakeholder views of the competency requirements of facilities management graduates. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 22(6), 471–478.

- Baum, A. & Lizieri, C. M. (2002). Real estate education in Europe. Urban Land Institute, Washington, D.C.

- Bennis, W.G & O’Toole, J. (2005). How business schools lost their way. Harvard Business Review, 83(5), 96.

- Butler, J., Guntermann, K. L., & Wolverton, M. (1998). Integrating the real estate curriculum. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 1(1), 51–66.

- Chambers, L., Holm, J., & Worzala, E. (2009). Graduate real estate education: Integrating the industry. International Journal of Property Science, 2(1).

- Charles, S. L. (2015) Graduate real estate education: The ULI Hines student competition. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 19(2), 149–173.

- Galuppo, L. A. & Worzala, E. M. (2004). A study into the important elements of a master’s degree in real estate. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 7(1), 25–42.

- Gibler, K. M. (2001). Applying writing across the curriculum to a real estate investment course. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 4(1), 42–53.

- Hardin III, W. G. (2001). Practical experience, expectations, hiring, promotion and tenure: A real estate perspective. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 30(2), 17–34.

- Jain S., Jain, P., & Sunderman, M. (2018). Designing and delivering effective online instruction. International Journal of Research in Management & Social Science, 6(1), 133–140.

- Kane, G. C., Palmer, D., Phillips, A. N., Kiron, D., & Buckley, N. (2018, June 5). Coming of age digitally. MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte Insights. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/projects/coming-of-age-digitally/

- Manning, C., & Roulac, S. (2001). Where can real estate faculty add the most value at universities in the future? Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 4(1), 18–39.

- McFarland, M. & Nguyen, D. (2010). Graduate real estate education in the U.S.: The diverse options for prospective students. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 13(1), 33–53.

- Ooi, J. & Yu, S. M. (2011). Graduate real estate education in Singapore: What prospective students look for. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 14(1), 35–52.

- Poon, J. (2012). Real estate graduates’ employability skills: The perspective of human resource managers of surveying firms. Property Management, 30(5), 416–434.

- Poon J. (2014). Do real estate courses sufficiently develop graduates’ employability skills? Perspectives from multiple stakeholders. Education and Training, 56(6), 562–581.

- Poon, J. (2016). An investigation of characteristics affecting employment outcomes and patterns of real estate graduates. Property Management, 34(3), 180–198.

- Poon, J. & Brownlow, M. (2016). Employment outcomes and patterns of real estate graduates: Is gender a matter? Property Management, 34(1), 44–66.

- Poon, J., Hoxley, M., & Fuchs, W. (2011). Real estate education: An investigation of multiple stakeholders. Property Management, 29(5), 468–487.

- Saginor, J., Weinstein, M. B., & Worzala, E. (2014). Graduate real estate education: A survey of programs after the great recession. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 17(2), 87–109.

- Schulte, K. W (Ed.). (2002). Real estate education throughout the world: Past, present and future (Vol. 7). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Schulte, K. W., Schulte-Daxbok, G., Breidenback, M., & Wiffler, M. (2005). Internationalization of real estate education [Conference presentation]. In ERES Conference: Dublin, Ireland.

- Tu, C., Weinstein, M. B., Worzala, E. & Lukens, L. (2009). Elements of successful graduate real estate programs: Perceptions of the stakeholders. The Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 12(2), 105–122.

- Urban Land Institute. (2003). Human capital survey. The 2003 Equinox Report.

- Wadu W. M., Chiang, J. & Chiang, Y. H. (2012). Key elements of successful graduate real estate education in Hong Kong: Students’ perspective. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 15(2), 101–128.

- Weinstein, M. (2002, April 10-13). Examination of top real estate programs: Implications for improving education for practitioners: An analysis of real estate [Paper presentation]. Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the American Real Estate Society, Naples, Florida.

- Weinstein, M., Manning, C., & Seal, K. (2007). How CEOs of real estate companies like to learn. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 10(2), 123–147.

- Weinstein, M. & Worzala E. (2008). Graduate real estate programs: An analysis of the past and present and trends for the future. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 16(3), 387–413.

- Wolverton, M. & Butler, J. Q. (1997). Denying traditional senses: Lessons about program change. Teaching in Higher Education, 2(3), 295–313.

- Worzala, E. (2003). Bridging the practical/academic divide in real estate. Pacific Rim Property Research Journal, 8(1), 3–14.

- Worzala, E. & Chambers, L. C. (2006). Bringing the outside in: The coalescence of industry and academia in real estate education. In Stand and Entwicklungs-tendenzen derImmobilienokeonomie. Immobiliend Informationsverlag (pp. 423–436). Rudolf Miller GMbH & Co.

- Worzala, E., Tu, C., Benedict, R., & Matthews, A. (2013). A graduate real estate program survey: Careers and compensation. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 16(1), 29–39.