Abstract

Information systems (IS) are increasingly used in social care agencies. This scoping review examined the research literature to identity practical knowledge relevant to social care agencies introducing IS. Selected studies documented elements of practical knowledge, though this was not the direct focus of any individual article. A synthesis of the 50 selected studies into a themed matrix highlighted the practical knowledge gap for social care agencies, and community service agencies in particular. This review identified two features critical to generating relevant practical knowledge: the participatory role of the researcher-designer, and the active role of IS participants.

Introduction

There is an increasing demand for use of information systems (IS) within social care agencies. Contributing to this demand has been the social care sector’s central role translating government social policies and reforms into practice through its work, domain knowledge and welfare perspectives (De Corte et al., Citation2019; Wilson et al., Citation2011). In Western societies, the social care sector comprises government departments, municipal or local authorities and for-profits; and non-government and not-for-profit agencies, often referred to as community service organizations, non-government organizations (NGOs), or the Third Sector (Stillman & McGrath, Citation2008). This article uses the term NGO for community-based agencies using social work and other roles to deliver a range of child and family, disability, homeless, youth justice homes, and/or care-focused adult social services (Gillingham, Citation2014b; Lyons, Citation2001). In Australia, a growing number of social care services are delivered by NGOs.

Australia’s Federal and State (or Territory) Governments’ ongoing agenda of divesting their social care work to NGOs contributes to this growth. One consequence of the increasing range of activities for NGOs is a greater need for IS to support their responses to the changing socio-political environment (Martikainen et al., Citation2022; Lagsten, Citation2012; Sawyer, Citation2009). Internal changes to the role of social workers as knowledge workers also drive this need (Shaw et al., Citation2009). As Devlieghere and Roose (Citation2018, p. 651) observed, the significance of the “informational context in which social work has been operating” has continued to grow. As new ways are found to harvest social work records for different purposes, organizational management of knowledge and information has also grown (Barfoed, Citation2019). For managers, this includes expanding demands for performance management, the need for greater capability for regular and real-time reporting, and the ability to show improved outcomes for service recipients.

Demands from funders add to these layered and complex arrangements within Australian NGOs. Often contractual agreements need NGOs to interface with funders’ tailored information management systems. The daily routines of social workers now involve many systems to record their work with service recipients (Lagsten, Citation2012). Managers are also often reliant on many systems and manual processes to extract data and information they need from different entry and exit points. This makes IS an attractive solution for enabling core organizational functions of communication, knowledge management, and other delivery commitments (Barfoed, Citation2019; Hill, Citation2014; Stamoulis, Citation2020). Availability of an integrated platform may also be attractive to its many potential users.

Introducing IS to agencies brings change—changes to social work practice, social changes, and organizational changes to systems and processes. These changes are challenging for smaller, regional NGOs with fewer infrastructural supports such as financial, technical, research or change management, or implementation expertise or capacity (Stillman & Linger, Citation2009). While there continues to be an expectation that bringing in IS will support social care practices, there are ongoing international debates about pitfalls and limitations that indicate this is not always the case (Garrett, Citation2005; Gillingham, Citation2021; Munro, Citation2004, Citation2005; Parton, Citation2009). Australia has its own stories of such failures in its social care sector (Burton & van den Broek, Citation2009; Dearman, Citation2005; Gillingham, Citation2013). In light of such IS failures, this scoping review considers if there is practical knowledge available to support agencies in their IS introduction, and whether the academic literature provides such knowledge.

In doing so, this research has arisen from collaboration with an Australian NGO seeking to minimize mistakes; learning what worked for other agencies from a practical point of view, and wanting to identify enabling and constraining factors when introducing IS (French & Stillman, Citation2014). The review has thus focused on knowledge that was “practically relevant in a general sense” (Goldkuhl, Citation2012, p. 59). Applying a systems perspective enabled a whole-of-design approach (Hood et al., Citation2021; Munro, Citation2005; Seddon, Citation2008; Seniutis et al., Citation2021). This approach reflected the ambition of community-informatics and socio-informatics to bridge the socio-technical divide between social work and technical expertise (Stillman & Linger, Citation2009; Wulf et al., Citation2018). Earlier scholars argued the principles for effective design were already well known (Trkman, Citation2010; White et al., Citation2010). The applied purpose of this scoping review was to identify in the literature where, what, how and the extent this practical bridging expertise, as Rolan et al. (Citation2018) stated, had configured the people, the social and the technical.

Methods

The approach taken was a scoping review, examining what practical knowledge was provided in the academic literature that could support social care agencies to avoid pitfalls when introducing IS. A scoping review was considered appropriate given the wide range of methodologies, different disciplinary roots, and contrasting fields and literatures relevant to IS and social care (Peterson et al., Citation2017). Using a scoping review also allowed for the extent, scope and nature of research work and its mapping without having to exclude articles on method, design, or quality of findings (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Munn et al., Citation2018). The framework used here has followed the work of Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) consisting of five stages: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying the relevant studies: (3) selecting the studies: (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results. In addition, Munn et al.’s (Citation2018, Citation2022) guidance complemented Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) framework in achieving a fuller synthesis of the evidence. This involved systematically identifying and mapping “key characteristics or factors related to a concept” relevant to the research questions (Munn et al., Citation2022, p. 950).

Finally, the creation of a concept as advocated by Munn et al. (Citation2022) was achieved through applying Tjora’s (Citation2018) “stepwise-deductive induction” method. Tjora’s method enabled the synthesis of the findings using the following steps: (1) identifying a small number of studies with content of practical value; (2) applying a coding process to each study and testing these against further studies that had been identified; (3) synthesizing this evidence into criteria for analysis of all selected studies; and (4) testing the analysis being developed against relevant socio-technically informed writing. Cronley and Patterson (Citation2010) provided this independent validation of Tjora’s final step, naming three barriers to IS use: the technical, the individual and organizational. In line with the research questions noted below, the analysis provided results consistent with Goldkuhl’s (Citation2012) concept of ‘practical knowledge’, identifying the practical knowledge to respond to the research questions noted below.

Identifying the research question and relevant studies

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify practical knowledge guided by the following exploratory questions:

(1) What practical knowledge is provided for social care agencies that want to introduce an information system?

Application of Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) methodological framework guided the summarizing of the selected studies into themes, as had Ylönen’s (Citation2022) similarly focused scoping review. Munn et al.’s guidance, however, enabled a fuller synthesis of evidence that assisted in addressing the second research question:

(2) What practical knowledge is relevant for NGOs that want to introduce an information system?

Trialing search terms aimed to capture the complexity within the literature. Limiting the relevant studies that addressed these questions, however, proved challenging. Early testing identified many words and phrases with similar meanings across disciplines and countries. Information systems could, for example, be case management systems or its acronym CMS, electronic information systems (EIS or IS), information and communication systems (ICT), or management information systems (CIMS, IMS), or management systems (MS). So too, when considering social care, different countries used different terms such as “child welfare,” “child and family services,” “human services,” “support services,” and even “non-medical services.” Social work might be “social care,” “human services,” “human service agencies,” “HSOs,” “child welfare,” “child welfare services,” “child and family services,” “child welfare” or “welfare services.” Two key search terms were chosen, “information systems” and “social work”.

An early decision to use “social work” as one of the two key search phrases was its ability to limit results, in comparison to the more expansive “social care” term. This phrase is also important given the work of social work is core to knowledge management and delivery of social care (Lagsten, Citation2012). The early testing resulted in the finalized scope outlined in which was applied to the electronic databases EBSCO, ProQuest, WoS, Scopus and Google Scholar. The period selected, from the year 2000 to the present, resulted in many studies. The decision to stay with this length of time, however, arose from identifying that research in the early 2000s was central to addressing the research questions. The application of search criteria to collect the maximum relevant articles prior to the final stages of abstract and article assessment, took place over 18 days from 18 April to 7 May 2022.

Table 1. Database searches to identify relevant studies.

Study selection and charting the data

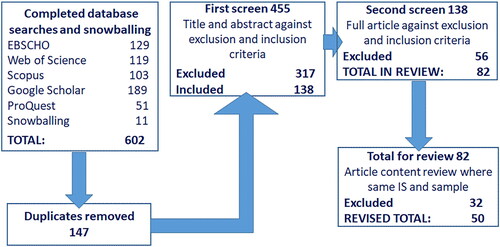

The search of the five databases identified 591 articles for initial screening; a further 11 articles identified via a snowballing process made 602 articles (Greenhalgh & Peacock, Citation2005). outlines the criteria applied through the structured environment of the web-based Covidence™ software platform. With duplicated data removed (147), 138 case study articles were selected for full article review against the criteria. This second screening delivered 82 articles for review.

Table 2. Scoping review inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies.

The empirical content criteria noted in helped limit the search to studies likely to have tested evidence of what works in IS use in social care. This excluded many theoretical or critical social policy studies, though they provided contextual information (Gillingham, Citation2014a, Citation2017; Parrott & Madoc-Jones, Citation2008; Parton, Citation2009; Wang et al., Citation2019; Wastell, McMaster, & Kawalek, Citation2007).

A final exclusion criterion to determine the mapping starting point identified instances of multiple articles based on the same case study. Applying this level of sensitivity resulted in one article chosen to represent a given study. To minimize possible skewing of subsequent data analysis, where multiple articles by the same author/s referred to a single study, or it was unclear whether the same empirical data underpinned the article, the present review treated them as one study. A further review of the 82 articles against the final exclusion criterion resulted in 50 studies. Studies that met the inclusion criteria are summarized in the flow diagram in .

Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

The first, numeric, analysis mapped the ‘who, when, where, how’ and agency type of the selected articles. Patterns in research were examined from variables of author, date, study location, research focus and design, methods, and themes, summarized in Appendix . The analysis of the selected studies used Excel™ software and its pivot table and graph functions. The second, thematic, analysis assessed where researchers looked, what they looked at, the scope of their study, and how they went about their work.

To chart the data, key concepts relevant to the research questions about what did not work, what might work, and what worked, were identified using a thematic approach. Tjora’s (Citation2018) stepwise-deductive induction method informed the development of criteria and themes for grouping the studies and the identification of the selected studies for review. Aligned with a whole-of-design view and building on the development of the concept of practical knowledge outlined earlier, each study was assessed against the criteria seen in (see below) for themes and enabling building blocks. The criteria developed included considerations of generalizability, with the aim of identifying those studies more likely to assist NGOs, in line with the second research question (Appendix ).

Findings

Numeric analysis

The numeric analysis drew on the identified study characteristics of the selected studies, summarized in Appendix . The 50 selected studies were undertaken across 13 countries, the greatest number in UK (n = 12), followed by Australia (n = 10), USA (n = 8), and 10 other countries. While one study did not identify where their research was based for sensitivity reasons, this data indicated a global interest in IS and social care. In seeking to address the present research questions, the initial focus was on whether the studies in this diverse geographical spread had applied a particular method or theory, or came from similar academic disciplines. Most of the studies were qualitative (n = 41), while six studies used solely interviews (n = 6). Other studies applied a mixed-methods qualitative approach to data gathering, including workshops, interviews, participant observation, and document analysis.

The selected studies varied in describing the theoretical framework informing their research. The largest group (n = 14) did not refer to a perspective, a general point noted by Yigitbasioglu et al. (Citation2023). Eleven studies reported use of ethnography, and a socio-technical/informatics standpoint was named in ten studies. Twenty-two studies reported using more than one perspective. The range of theoretical frameworks was similarly reflected in the broad interdisciplinary interest earlier noted. The included studies were published in 27 different journals, ranging from labor studies, informatics, evaluation, social work practice, research and governance, applied ergonomics, social policy, administration and social inclusion, to technology and IS (Appendix ). These findings showed the multiple perspectives and disciplinary fields of interest used in researching this area.

Two internal scope factors of the selected studies were numerically analyzed to provide an understanding about the nature of the data being examined: IS user participation and agency type. With respect to user participation, most of the studies’ participants included social workers (n = 46) as variously defined across countries, with 25 studies focused solely on social work roles. Other participant roles included executive, IT, HR, psychologist and other health professionals, administration support, vendors, and policy makers. Six of the studies (12.0%) included service recipients.

Given the second research question related to NGOs, analysis was then undertaken to identify the type of agency researched. The majority of case studies (n = 30) were based on large government agencies, that is, municipal organizations, local authorities, or centrally-driven entities. Seven studies appeared to be a mix of government agencies and NGOs; however, their focus on larger agencies took the number to 37 (of 50) studies of large, government agencies. One study did not state the agency type examined; the remaining 12 studies (24.0%) explored NGOs (Appendix ).

The agency type in each study was mapped against the three groupings identified through the thematic analysis expanded in the next section. shows the mapping of the 50 studies by agency type to the three groups into which each study was subsequently allocated ( below). The thematic analysis grouping depended on whether they demonstrated limited practical knowledge, provided experimental potential, or showed more practical knowledge for IS introduction. reflects the complexities of the contexts, approaches and interests of researchers examining IS and social care. NGOs appear across all three groups, reflecting both enabling factors and barriers identified in the studies; five of the 12 NGO studies were assigned to the group of limited knowledge. also shows the high proportion of practical knowledge relevant to NGOs arising from studies based on NGOs themselves.

Table 3. Level of practical knowledge assistance by agency type.

Table 4. Practical knowledge matrix for an agency seeking to introduce IS.

Table 5. Criteria for study assignment to groups of increasing practical knowledge.

Thematic analysis

Applying a thematic analysis to the 50 studies identified four themes: IS context, agency context, user input and sector context. Tjora’s (Citation2018) method guided the critical reading of each study to identify and group key components that supported the introduction of IS in social care. The analysis also identified a fourth theme, the sector context, adding to the three earlier identified in Cronley and Patterson’s (Citation2010) study noted in the present methods section. (These writers drew on the earlier socio-technical systems theory work of Pasmore who had also identified the dynamic nature of organizations with their external environments. See, for example, Pasmore, Citation1995.) presents summarized results of enabling factors of what worked, suitable for an agency seeking practical knowledge for introducing IS. Dependent on the project area (theme)—an agency’s IS context, its own agency context, its user input and its sector context—an agency’s next step is to review each main area of project design and development work (the building blocks); and then consider what needs to happen and how (the key strategies).

Tjora’s idea of “conceptual generalization” was then used to classify themes and/or building blocks either as enablers or constraints impacting IS in social care. These factors were included in the criteria to assign each study into one of three groups of increasing practical knowledge. outlines the criteria that were developed, assigning each study into one or other group addressing the research questions. This analysis identified six studies for closer review, where enabling conditions of what worked across all four themes () were present.

Taken together, and present the three main results of the present scoping review. provides detailed information to guide project design for an agency looking to introduce IS. Second, summarizes the criteria for assigning the 50 studies into three groups, reflecting the contribution of practical knowledge from IS researchers. The third and subsequent key result of this analysis is the identification of six studies for closer review. Their usefulness extends beyond this scoping review to provide useful practical knowledge for NGOs seeking to introduce IS. Appendix summarizes the key features of these six studies. The analysis below provides the narrative for how criteria developed in and were utilized to allocate the studies into one of three groups.

Group 1 limited practical knowledge

Of the 50 studies, 36 (72.0%) were assigned to this group as they met the inclusion criteria () of limited practical knowledge. Some studies met multiple criteria; Devlieghere, Bradt, and Roose (Citation2017a) was an example of a study with a singular theme around the dominant impact of neoliberalism, and was also about a large agency. Thirty of these 36 studies involved larger agencies, characterized by centrally-mandated IS construction or implementation, and involving little-to-no user input (Appendix ). Researchers cautioned on limitations of transferability of knowledge from large agencies examined (Devlieghere et al., Citation2017b; Shaw et al., Citation2009). This first group also reported predominantly negative findings (n = 26), or a mix of negative and some positive findings (n = 10) about IS use. There were 11 studies in Group 1 that met the criterion of having all four themes; however, their mapping to this group arose from the dominance of sector context impact, and its largely negative findings (Barfoed, Citation2019; Burton & van den Broek, Citation2009; Gillingham, Citation2013, Citation2015a; Hill, Citation2014; Koskinen, Citation2014; Pithouse et al., Citation2012; Sarwar & Harris, Citation2019; Seniutis et al., Citation2021; Shaw & Clayden, Citation2010; Shaw et al., Citation2009). Though broad in their scope, the barriers outlined in these studies resulted in their being assigned to this group.

The criteria of limited theme examination () resulted in assigning 25 studies to this first group. Regardless of particular findings, where a study’s interest was limited in its cover of themes, that meant by definition it was limited in its practical help and placed in Group 1. Six studies largely focused on just the one theme: the impact of neoliberalism (Devlieghere et al., Citation2017a); and variations around IS use: user emotions (Loberg & Egeland, Citation2023; Zorn, Citation2003), worker satisfaction (Moses et al., Citation2003), and user resistance and ‘workarounds’ (Monnickendam et al., Citation2005; Huuskonen & Vakkari, Citation2015). Another 19 studies were assigned to Group 1 as they focused on just two or three of the four themes outlined in (Aasback, Citation2022; Carrilio et al., Citation2004; Cronley & Patterson, Citation2010; De Witte et al., Citation2016; Dearman, Citation2005; Gillingham, Citation2016b, Citation2018, Citation2021; Hoybye-Mortensen & Ejbye-Ernst, Citation2019; Jeyasingham, Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2013; Martikainen et al., Citation2022; Salovaara & Ylönen, Citation2022; Savaya et al., Citation2004; Savaya et al., Citation2006; Smith & Eaton, Citation2014; Spensberger, Citation2019; Zhang & Gutierrez, Citation2007; Zhu & Andersen, Citation2021). The limited scope of all quantitative studies resulted in their mapping to this first group. Collectively, these studies did not provide a blueprint for what might work, or worked.

Group 2 experimental potential

All studies in this group covered the four themes (); that is, an agency’s IS context, its organizational context, its particular user input, and sector context. However, they reported possible, but as yet not fully tested, enabling factors. This group comprised eight (16.0%) of the 50 studies, offering ‘experimental potential.’ Seven of these eight studies described their development and testing of alternative conditions as arising from their prior close involvement with problematic IS (Fitch, Citation2004; Ince & Griffiths, Citation2011; Lagsten & Andersson, Citation2018; Wastell & White, Citation2014a; Wastell et al., Citation2011; Wilson et al., Citation2007; Wilson et al., Citation2011). It was their experimental potential from testing and exploring models of what might better work across a range of IS considerations that offered greater practical knowledge than the first group.

This group explored client-centered models (Fitch, Citation2004; Wilson et al., Citation2011); a stakeholder method (Lagsten & Andersson, Citation2018); and data limitation resolution (Wilson et al., Citation2007). Two user-centered design models were developed and tested (Coursen, Citation2006; Wastell et al., Citation2011), noting Gillingham’s (Citation2015b) criticism of the latter’s approach. Two research teams developed models (Ince & Griffiths, Citation2011; Wastell et al., Citation2011) following their involvements in Munro’s review of the UK’s Information Case Management System (ICS). While these studies included aspects that could be considered enabling factors across all four themes, their experimental nature, as opposed to tested field work in an organizational setting, placed them in the potential group. It is noted that the eight studies of Group 2 showed a similar exploratory, problem-solving approach identified in the third and final group.

Group 3 more practical knowledge

This smallest group included only six studies identified as having enabling building blocks across all four themes as per criteria (Clapham et al., Citation2021; French & Stillman, Citation2014; Goldkuhl, Citation2012; Stillman et al., Citation2009; Tregeagle, Citation2016; Yigitbasioglu et al., Citation2023). They offered the most practical knowledge to a community agency seeking to introduce IS, reporting on aspects of IS introduction that worked, bridging the people, social and technical in IS construction. These researchers came with an exploratory interest and applied problem-solving elements or variations of such practice research approaches (Goldkuhl, Citation2012). The authors’ approaches resulted in their studies being less about describing the ‘as-is’ and more about building and applying practical knowledge during research. This knowledge drew on the expertise of system users in the broadest sense and combined the technological and social care expertise to iteratively design, develop and embed fit-for-purpose IS.

Researchers in the six studies collectively offered practical narratives around IS construction (Clapham et al., Citation2021; French & Stillman, Citation2014; Goldkuhl, Citation2012; Stillman et al., Citation2009) and ongoing use (Tregeagle, Citation2016; Yigitbasioglu et al., Citation2023). Five of the six studies examined NGOs, and showed why local context and localized solutions were integral components to introducing IS (Clapham et al., Citation2021; French & Stillman, Citation2014; Stillman et al., Citation2009; Tregeagle, Citation2016; Yigitbasioglu et al., Citation2023). They demonstrated how working closely with users helped develop deep knowledge of local situations, resulting in technology and its inevitable change management more aligned to their needs. These studies illustrate an interdisciplinary approach to understanding and generating knowledge. Together, the six studies in Group 3 showed development of “work systems” based on local conditions and methods of work, reflecting Munro’s (Citation2011a, Citation2011b) systems approach for successful design in social work services. These studies are the focus of discussion in the next section.

Discussion

This review of 50 studies found that no study fully addressed either research question. While the findings of these studies individually offered elements of practical insight, these were insufficient of themselves for agencies looking to introduce IS. This is understandable, given the nature of academic research and its interest in examining and furthering aspects of particular topics. That said, many researchers in this review described IS that precluded participation, or reported on its subsequent use in large, centrally-driven agencies. While the findings are not in contest, the criteria outlined in used to analyze these studies assigned such studies to the first group of limited practical knowledge.

Addressing the research questions about the availability of practical knowledge to support social care agencies and NGOs in particular, this review identified applied levels of practical knowledge about an agency’s IS context, its organizational and sectoral contexts, and its particular user needs. The six studies in Group 3 identified with more practical knowledge for agencies including NGOs will be the primary focus of this discussion. Specifically, this discussion explores two findings and their possible connection to constructing fit-for-purpose IS in a social care NGO: the role played by the researcher-designer, and the role of IS participants. The importance of these findings centers on how the practical bridging of social work and technical expertise might support impending IS introduction and accompanying change processes. This section then concludes with a brief consideration of the practical and theoretical implications around knowledge for NGOs wanting to introduce IS, and potentially making use of the review findings.

The role of researcher-designer

What distinguished these six studies was how the researchers went about their work to collectively build fit-for-purpose IS. These studies demonstrated what Goldkuhl (Citation2012, p. 59) described as the most useful research, where problem-solving work is “practically relevant in a general sense.” Further, in evidencing the necessary bridging of the people, social, and technical, these studies collectively demonstrated “cooperative knowledge production in social work settings” (Driessens et al., Citation2011, p. 71). Critical to delivering such results were two components: relevant expertise, and the skills of collaboration.

The six studies of Group 3 that showed the most practical knowledge illustrated how changes were best served by expertise that bridged the socio-technical divide. Technology and social care organizations have their own knowledge domains; it stands then, that introducing IS are about fuzing two kinds of change, the technical and organizational (Wastell & White, Citation2014b). In the six studies, the relevant theoretical expertise ranged from community informatics (Clapham et al., Citation2021; French & Stillman, Citation2014), community informatics and grounded theory (Stillman et al., Citation2009); IT and organizational change (Yigitbasioglu et al., Citation2023); and a social constructionist view of technology (Tregeagle, Citation2016). Goldkuhl’s (Citation2012) description of a practice research approach included extant theory, while allowing for new local theories to arise from staying close to local practice. Expertise in one of these approaches or the ability to work within such frameworks would be important considerations for NGOs seeking to introduce fit-for-purpose IS.

The researchers’ expertise was also seen in these studies in that their technical and/or design facilitation expertise was part of the change process (Clapham et al., Citation2021). While Tregeagle (Citation2016) did not bring the technical background of researchers such as Stillman, she understood the importance of internally driven social work/technical partnering, critical change components of knowledge transfer, and ongoing IS ownership. The user-tailored design arising from Stillman et al.’s (Citation2009) whole-of-agency approach and supported by wide participant involvement were seen in their two community IS development projects. A second study by French and Stillman (Citation2014) included in this third group provided an example of the importance of using unique local factors and their theoretical and empirical considerations for fit-for-purpose IS design. Yigitbasioglu et al. (Citation2023) likewise reported on enabling change processes, noting the need for specific welfare expertise in vendors, and for vendor involvement to build the elusive success factor, trust. These aspects of expertise demonstrate a variety of skills and further provide options for what an NGO might look for when considering the type of expertise that might best suit its organization, its local context and its technological maturity.

Integral to drawing on the expertise to bridge the socio-technical divide was the ability of the researcher-designer to collaborate with others. Working collaboratively was deemed to be supportive of “work[ing] towards practice change during the research process” (Gelling & Munn-Giddings, Citation2011, p. 101). The approaches of the researchers in these six studies were more active and contributory by design. Stillman et al. (Citation2009) demonstrated their participatory approach as they stepped through the collaborative design change process they reported. French and Stillman (Citation2014) recognized the importance of people and practices rather than the technical agenda and, based on their collaborative work, described flexible and responsive approaches when developing IS. Their understanding of the complex nature of the work occurring within a collaborative culture translated into an iterative, interactive design approach. Clapham et al. (Citation2021, p. 6) used community-led processes that generated a highly participatory approach across all phases, meeting both agency and end user expectations of the new IS they were jointly developing. By contrast, in Group 1, Gillingham (Citation2015b, p. 656) for example, acknowledged that the self-limited participant observer role did not meet “the agency’s expectation… that [he] would contribute to the process rather than just observe.” Goldkuhl (Citation2012) also contrasted the more traditional research approach of being independent and having no active involvement, with a role of collaborative design between researchers, the IT specialists, and welfare workers, as the way to build new, practical knowledge.

These six studies showed attention in different ways to managing organizational change, and ways to support social workers and others through this change. The subsequent change to the nature of work identified in the two community studies of Yigitbasioglu et al. (Citation2023), for example, described ways these changes were collaboratively managed, including knowledge-sharing transfer between the vendor and the community agency. Building a deep understanding of others’ expertise and their unique situations enabled researchers such as Stillman et al. (Citation2009) to describe the accompanying change management as being on terms set by the agency itself. Further, Clapham et al. (Citation2021, p. 7) confirmed IS design relied on “designers bring[ing] technical and facilitation skills creating opportunities for mutual learning and development.” This evidence indicates the introduction of fit-for-purpose IS relies heavily on the researcher-designer’s capacity to collaboratively engage with all potential users to draw on their expertise to develop deeper insight into the requirements of those who will be the users.

The role of IS participants

Rather than privileging technological or managerial forms of thinking, what helped the research-designers in the six studies in their IS construction was their elicitation and use of others’ expertise. This “partnership with participants in which participants bring essential knowledge of their own context and culture” (Clapham et al., p. 7) was shown in these studies to enhance the capacity of IS to be more fit-for-purpose, again in different ways. In doing so, it was about walking alongside a wide range of people to become well attuned to the cultural and social factors of the workplace and local environment; this included continuing to involve staff and others as experts in revising and embedding change post IS introduction (Tregeagle, Citation2016). This review identified the importance for IS construction of eliciting expertise from two groups of ultimate end users in the broadest sense: social work and other agency participants, and service recipients and their communities.

The six studies in Group 3 stood apart in how internal participants were perceived and involved by these researchers. It was in these six studies that social workers were involved as actual designers with embedded expertise. Their voices enabled the IS design to be more practice-led, and for design to incorporate their unique workplaces and social work roles. Their experiences were integral in the researchers’ mapping and understanding of the work to help design a system that helped to make the work work better (Lagsten, Citation2012). While the second group of experimental potential researchers involved social workers as testers, by contrast, the first and largest group of 36 studies described social work participants largely by their function as users, rather than as partners-in-design as characterized in the third group.

A whole-of-agency approach ensured that the range of knowledge workers and other roles also contributed to IS construction and organizational change. A similar level of involvement of participants such as other professional support roles, administrative and other support staff, and vendors was noted in most of the six studies (Clapham et al., Citation2021; French & Stillman, Citation2014; Goldkuhl, Citation2012; Stillman et al., Citation2009; Yigitbasioglu et al., Citation2023). Clapham et al. (Citation2021) talked about participants more broadly and was one of the few studies that reported on how such participation contributed to successful IS construction. This wider staff involvement reflects an agency’s reality of the increasingly diverse roles involved in managing information; where each role contributes to the agency’s purpose. The importance of wide staff participation in developing fit-for-purpose IS was also reflected in the frequent advocacy by several researchers in Group 1 for their involvement, and specifically that of social workers (Burton & van den Broek, Citation2009; Gillingham, Citation2013, Citation2014b, Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2018, Citation2021; Johnson, Citation2013; Martikainen et al., Citation2022; Seniutis et al., Citation2021; Shaw & Clayden, Citation2010).

Another broad group of participants to play a critical part in developing fit-for-purpose IS comprised an agency’s service recipients and their communities. The alignment of IS as a tool that supports the delivery of client-centered social care would suggest their views and experiences should be central. However, little such research was found in this review. While this review confirmed Ylönen’s (Citationin press) finding that service recipient participation is a gap, two studies in the third group did actively involve them as research-designers. First, Tregeagle (Citation2016) advocated for the involvement of children and families, and her research actively involved them in IS refinement post the IS introduction in a community setting. Second, Clapham et al. (Citation2021) actively involved service recipients in IS development. A further two researchers in the second group of experimental potential offered possibilities in their testing client-focused models (Fitch, Citation2004; Wilson et al., Citation2011), and two studies in Group 1 included service recipients as users (Barfoed, Citation2019; Shaw & Clayden, Citation2010).

In regional settings community culture more visibly plays an important role alongside organizational culture (French & Stillman, Citation2014). The study that stood out as showing community as important to developing fit-for-purpose IS was Clapham et al. (Citation2021). They described the centering of service recipients, Indigenous voices and community in successful system design and implementation. The authors described privileging local voices, real participation and inclusive decision-making. Their framework offered practical knowledge that actually worked by leveraging knowledge across researchers, local Indigenous agencies, and their communities.

Finally, in summarizing the point of difference of these six studies in demonstrating fit-for-purpose IS construction: what characterized these studies was the conceptualization of IS participants as part of creating the solution, rather than their being examined as part of the problem. The researchers took the time to understand participants’ unique technological, structural and organizational challenges in the workplaces they studied, and worked together on IS to best meet their identified needs.

Practical implications

This review has highlighted available practical knowledge for agencies, and NGOs in particular, in the literature. The synthesis of evidence from the 50 studies into a matrix of practical knowledge of what works offers a framing for agencies wanting to introduce IS. Having included the sectoral context with the IS, agency and user contexts, the matrix also brings focus for agencies to their local and socio-political environments. Such contexts, while often latent rather than functionally explicit in smaller agencies, can be significant in their impacts. Nineteen of the 36 studies in Group 1, for example, examined the negative impact of neoliberalism and its managerialist agendas on IS in social care (Barfoed, Citation2019; Devlieghere et al., Citation2017a; Gillingham, Citation2011, Citation2015a; Hill, Citation2014; and Seniutis et al., Citation2021 are examples). It is equally important to understand that unique contexts for locally-based community services have their own challenges. In reflecting the diversity and breadth of the findings and foci in these studies, the development of the matrix () goes some way to addressing both research questions about identifying practical knowledge relevant to introducing IS in social care.

The extent to which the matrix, however, is relevant specifically to NGOs is a fair challenge. What became apparent in the thematic analysis was that the generalizability of findings to NGOs could not be assumed. The six studies of greatest relevance (Group 3), where five of these studies are NGOs, positively illustrated all four themes in the matrix. The collated content of still means researchers and NGOs need to identify and test enablers and constraints relevant to their unique situation as part of mapping the where, what, how and scope of their impending organization and technical change management.

Theoretical implications

The findings from the six studies in Group 3 indicate support for Müller-Bloch and Kranz’s (Citation2015, p. 19) contention that “theory should be applied to certain research issues to generate new insights.” In the last point on their 6-point framework developed to help reviewers identify research gaps, Müller-Bloch and Kranz argued for combining contemporary research with a stronger theoretical base to fill such a gap. In 2009, Stillman and Linger (p. 255) described this gap for IS and social care, and proposed a theoretical framework using community informatics to “fully address its information systems problem-solving agenda as well as its community problem-solving activities.” They also saw the opportunity to contribute to an IS—social care discourse where social action is integral to research. The six studies in Group 3 reflected in practical ways such an approach, albeit without being able to rely on such a theoretical framework.

In their building practical knowledge during research, the six studies in Group 3 confirm that the principles of effective design enunciated decades ago remain relevant (Trkman, Citation2010; White et al., Citation2010). This is seen in results from their methodologically distinctive positioning of researcher-designer and participants in their practice-research-theory approaches. It remains to be seen what more might be achieved if future research of IS and social care occurred within a strong theoretical framework as advocated by Stillman and Linger. The direction and cohesion from such a theoretical framework might also provide a foundation for integrating technological advances with the needs of social care agencies today.

Conclusion

In addressing the research questions about whether the academic literature provides practical knowledge to support social care agencies in their introduction of IS, this scoping review revealed the paucity of such literature. The review has also identified practical and theoretical implications of this knowledge gap. Further, the literature makes evident that the complexities of this organizational space mean there can even be enabling factors present, yet IS projects still fail. Whether all the building blocks are present and how they combine is contingent on many factors, often outside an agency’s control. Yet, with governments continuing to divest their care work, the need for fit-for-purpose IS to support small to medium-sized NGOs continues to grow. This need is especially pressing for agencies with fewer resources to manage their increasingly complex work worlds. Building on this scoping review by including gray literature and unpublished knowledge within the sector could enhance the capacity for NGOs to increase their success in constructing IS.

The analysis of this scoping review provided a level of consolidated practical knowledge, drawn from the selected review studies. In particular, the six studies identified as providing more practical knowledge illustrated the critical importance of the researcher-designer working collaboratively, and in expertise-partnership with a broad range of others. Generating new theory and insights for introducing IS in social care calls for researchers to actively engage in research to deliver more practical IS knowledge that supports NGOs deliver on the why of their social care work.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aasback, A. (2022). Platform social work—A case study of a digital activity plan in the Norwegian Welfare and Labor Administration. Nordic Social Work Research, 12(3), 350–363. doi:10.1080/2156857X.2022.2045212

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Barfoed, E. (2019). Digital clients: An example of people production in social work. Social Inclusion, 7(1), 196–206. doi:10.17645/si.v7i1.1814

- Broadhurst, K., Hall, C., Wastell, D., White, S., & Pithouse, A. (2010). Risk, instrumentalism and the humane project in social work: Identifying the informal logics of risk management in children’s statutory services. British Journal of Social Work, 40(4), 1046–1064. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcq011

- Burton, J., & van den Broek, D. (2009). Accountable and countable: Information management systems and the bureaucratization of social work. British Journal of Social Work, 39(7), 1326–1342. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcn027

- Carrilio, T. (2005). Management information systems: Why are they underutilized in the social services? Administration in Social Work, 29(2), 43–61. doi:10.1300/J147v29n02_04

- Carrilio, T. (2008). Accountability, evidence, and the use of information systems in social service programs. Journal of Social Work, 8(2), 135–148. doi:10.1177/1468017307088495

- Carrilio, T., Packard, T., & Clapp, J. D. (2004). Nothing in—Nothing out. Administration in Social Work, 27(4), 61–75. doi:10.1300/J147v27n04_05

- Clapham, K., Hasan, H., Fredericks, B., Bessarab, D., Kelly, P., Harwood, V., Dale, E. (2021). Digital support for indigenous research methodologies. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 25, 1–21. doi:10.3127/ajis.v25i0.2885

- Coursen, D. (2006). An ecosystems approach to human service database design. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 24(1), 1–18. doi:10.1300/J017v24n01_01

- Cronley, C., & Patterson, D. (2010). How well does it fit? An organizational culture approach to assessing technology use among homeless service providers. Administration in Social Work, 34(3), 286–303. doi:10.1080/03643107.2010.481194

- De Corte, J., Devlieghere, J., Roets, G., & Roose, R. (2019). Top-down policy implementation and social workers as institutional entrepreneurs: The case of an electronic information system in Belgium. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(5), 1317–1332. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcy094

- De Witte, J., Declercq, A., & Hermans, K. (2016). Street-level strategies of child welfare social workers in Flanders: The use of electronic client records in practice. British journal of Social Work, 46(5), 1249–1265. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcv076

- Dearman, P. (2005). Computerised social casework recording: Autonomy and control in Australia’s income support agency. Labor Studies Journal, 30(1), 47–65. doi:10.1177/0160449X0503000104

- Devlieghere, J., Bradt, L., & Roose, R. (2017a). Governmental rationales for installing electronic information systems: A quest for responsive social work. Social Policy & Administration, 51(7), 1488–1504. doi:10.1111/spol.12269

- Devlieghere, J., Bradt, L., & Roose, R. (2017b). Policy rationales for electronic information systems: An area of ambiguity. The British Journal of Social Work, 47(5), 1500–1516. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcw097

- Devlieghere, J., Bradt, L., & Roose, R. (2018). Creating transparency through electronic information systems: Opportunities and pitfalls. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(3), 734–750. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcx052

- Devlieghere, J., Bradt, L., & Roose, R. (2021). Electronic information systems as means for accountability: Why there is no such thing as objectivity. European Journal of Social Work, 24(2), 212–223. doi:10.1080/13691457.2019.1585335

- Devlieghere, J., & Roose, R. (2018). Electronic information systems: In search of responsive social work. Journal of Social Work, 18(6), 650–665. doi:10.1177/1468017318757296

- Devlieghere, J., & Roose, R. (2019). Documenting practices in human service organisations through information systems: When the quest for visibility ends in darkness. Social Inclusion, 7(1), 207–217. doi:10.17645/si.v7i1.1833

- Devlieghere, J., & Roose, R. (2020). A policy, management and practitioners’ perspective on social work’s rational turn: There are cracks at every level. European Journal of Social Work, 23(1), 144–155. doi:10.1080/13691457.2018.1460324

- Driessens, K., Saurama, E., & Fargion, S. (2011). Research with social workers to improve their social interventions. European Journal of Social Work, 14(1), 71–88. doi:10.1080/13691457.2010.516629

- Fitch, D. (2004). Client-controlled case information: A general system theory perspective. Social work, 49(3), 497–505. doi:10.1093/sw/49.3.497

- French, R., & Stillman, L. (2014). The informationalisation of the Australian community sector. Social Policy and Society, 13(4), 623–634. doi:10.1017/S1474746414000098

- Garrett, P. (2005). Social work’s ‘electronic turn’: Notes on the deployment of information and communication technologies in social work with children and families. Critical Social Policy, 25(4), 529–553. doi:10.1177/0261018305057044

- Gelling, L., & Munn-Giddings, C. (2011). Ethical review of action research: The challenges for researchers and research ethics committees. Research Ethics, 7(3), 100–106. doi:10.1177/174701611100700305

- Gillingham, P. (2011). Computer-based information systems and Human Service Organisations: Emerging problems and future possibilities. Australian Social Work, 64(3), 299–312. doi:10.1080/0312407X.2010.524705

- Gillingham, P. (2013). The development of electronic information systems for the future: Practitioners, ‘embodied structures’ and ‘technologies-in-practice’. British Journal of Social Work, 43(3), 430–445. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcr202

- Gillingham, P. (2014a). Driving child protection reform: Evidence or ideology? Australian Social Work, 67(3), 377–389. doi:10.1080/0312407X.2013.877948

- Gillingham, P. (2014b). Electronic information systems and social work: Who are we designing for? Practice, 26(5), 313–326. doi:10.1080/09503153.2014.958454

- Gillingham, P. (2014c). Information systems and human service organizations: Managing and designing for the “occasional user”. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 38(2), 169–177. doi:10.1080/03643107.2013.859198

- Gillingham, P. (2014d). Repositioning electronic information systems in human service organizations. Human Services Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 38(2), 125–134. doi:10.1080/03643107.2013.853011

- Gillingham, P. (2015a). Electronic information systems and human service organizations: The unanticipated consequences of organizational change. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 39(2), 89–100. doi:10.1080/23303131.2014.987412

- Gillingham, P. (2015b). Electronic information systems and human services organisations: Avoiding the pitfalls of participatory design. British Journal of Social Work, 45(2), 651–666. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct126

- Gillingham, P. (2015c). Electronic information systems and social work: Principles of participatory design for social workers. Advances in Social Work, 16(1), 31–42. doi:10.18060/18244

- Gillingham, P. (2015d). Electronic information systems in human service organisations: The what, who, why and how of information. British Journal of Social Work, 45(5), 1598–1613. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcu030

- Gillingham, P. (2015e). Implementing electronic information systems in human service organisations: The challenge of categorisation. Practice, 27(3), 163–175. doi:10.1080/09503153.2015.1014334

- Gillingham, P. (2016a). Electronic information systems and human service organizations: The needs of managers. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 40(1), 51–61. doi:10.1080/23303131.2015.1069232

- Gillingham, P. (2016b). Electronic information systems to guide social work practice: The perspectives of practitioners as end users. Practice, 28(5), 357–372. doi:10.1080/09503153.2015.1135895

- Gillingham, P. (2016c). Technology configuring the user: Implications for the redesign of electronic information systems in social work. British Journal of Social Work, 46(2), 323–338. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcu141

- Gillingham, P. (2017). Electronic information systems in human service organizations: Using theory to inform future design. International Social Work, 60(1), 100–110. doi:10.1177/0020872814554856

- Gillingham, P. (2018). Decision-making about the adoption of information technology in social welfare agencies: Some key considerations. European Journal of Social Work, 21(4), 521–529. doi:10.1080/13691457.2017.1297773

- Gillingham, P. (2019a). Developments in electronic information systems in social welfare agencies: From simple to complex. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(1), 135–146. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcy014

- Gillingham, P. (2019b). From bureaucracy to technocracy in a social welfare agency: A cautionary tale. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 29(2), 108–119. doi:10.1080/02185385.2018.1523023

- Gillingham, P. (2021). Practitioner perspectives on the implementation of an electronic information system to enforce practice standards in England. European Journal of Social Work, 24(5), 761–771. doi:10.1080/13691457.2020.1870213

- Gillingham, P., & Graham, T. (2016). Designing electronic information systems for the future: Social workers and the challenge of New Public Management. Critical Social Policy, 36(2), 187–204. doi:10.1177/0261018315620867

- Goldkuhl, G. (2012). From action research to practice research. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 17(2), 57–77. doi:10.3127/ajis.v17i2.688

- Greenhalgh, T., & Peacock, R. (2005). Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: Audit of primary sources. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 331(7524), 1064–1065. doi:10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68

- Hill, P. (2014). Supporting personalisation: The challenges in translating the expectations of national policy into developments in local services and their underpinning information systems. Social Policy and Society, 13(4), 593–607. doi:10.1017/S147474641400013X

- Hood, R., O’Donovan, B., Gibson, J., & Brady, D. (2021). New development: Using the Vanguard Method to explore demand and performance in people-centred services. Public Money & Management, 41(5), 422–425. doi:10.1080/09540962.2020.1815367

- Hoybye-Mortensen, M., & Ejbye-Ernst, P. (2019). What is the purpose? Caseworkers’ perception of performance information. European Journal of Social Work, 22(3), 458–471. doi:10.1080/13691457.2017.1366427

- Huuskonen, S., & Vakkari, P. (2015). Selective clients’ trajectories in case files: Filtering out information in the recording process in child protection. British Journal of Social Work, 45(3), 792–808. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct160

- Huuskonen, S., & Vakkari, P. (2013). “I did it my way”: Social workers as secondary designers of a client information system. Information Processing & Management, 49(1), 380–391. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2012.05.003

- Ince, D., & Griffiths, A. (2011). A chronicling system for children’s social work: Learning from the ICS failure. British Journal of Social Work, 41(8), 1497–1513. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcr016

- Jeyasingham, D. (2020). Entanglements with offices, information systems, laptops and phones: How agile working is influencing social workers’ interactions with each other and with families. Qualitative Social Work, 19(3), 337–358. doi:10.1177/1473325020911697

- Johnson, L. B. (2013). A qualitative study of communication among child advocacy multidisciplinary team members using a web-based case tracking system. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 31(4), 355–367. doi:10.1080/15228835.2013.861783

- Koskinen, R. (2014). One step further from detected contradictions in a child welfare unit—A constructive approach to communicate the needs of social work when implementing ICT in social services. European Journal of Social Work, 17(2), 266–280. doi:10.1080/13691457.2013.802663

- Lagsten, J. (2011). Evaluating information systems according to stakeholders: A pragmatic perspective and method. Electronic Journal of Information Systems Evaluation, 14(1), 73–88. www.ejise.com.

- Lagsten, J. (2012). Thinking about evaluation of information systems that makes work work. Workshop on IT Artefact Design and Workplace Intervention, 10 June, Barcelona. Digitala Vetenskapliga Arkivet.

- Lagsten, J., & Andersson, A. (2018). Use of information systems in social work—Challenges and an agenda for future research. European Journal of Social Work, 21(6), 850–862. doi:10.1080/13691457.2018.1423554

- Loberg, I. B., & Egeland, C. (2023). ‘You get a completely different feeling’—An empirical exploration of emotions and their functions in digital frontline work. European Journal of Social Work, 26(1), 108–120. doi:10.1080/13691457.2021.2016650

- Lyons, M. (2001). Third sector: The contribution of non-profit and co-operative enterprises in Australia. Allen & Unwin.

- Martikainen, S., Salovaara, S., Ylönen, K., Tynkkynen, E., Viitanen, J., Tyllinen, M., & Lääveri, T. (2022). Social welfare professionals willing to participate in client information system development—Results from a large cross-sectional survey. Informatics for Health and Social Care, 47(4), 389–402. doi:10.1080/17538157.2021.2010736

- Monnickendam, M., Savaya, R., & Waysman, M. (2005). Thinking processes in social workers’ use of a clinical decision support system: A qualitative study. Social Work Research, 29(1), 21–30. doi:10.1093/swr/29.1.21

- Moses, T., Weaver, D., Furman, W., & Duncan, L. (2003). Computerization and job attitudes in child welfare. Administration in Social Work, 27(1), 47–67. doi:10.1300/J147v27n01_04

- Müller-Bloch, C., & Kranz, J. (2015). A framework for rigorously identifying research gaps in qualitative literature reviews (pp. 1–19). Thirty-sixth International Conference on Information Systems, 13–16 December, Fort Worth, TX.

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Munn, Z., Pollock, D., Khalil, H., Alexander, L., Mclnerney, P., Godfrey, C., … Tricco, A. (2022). What are scoping reviews? Providing a formal definition of scoping reviews as a type of evidence synthesis. JBI evidence Synthesis, 20(4), 950–952. doi:10.11124/JBIES-21-00483

- Munro, E. (2004). The impact of audit on social work practice. British Journal of Social Work, 34(8), 1075–1095. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bch130

- Munro, E. (2005). What tools do we need to improve identification of child abuse? Child Abuse Review, 14(6), 374–388. doi:10.1002/car.921

- Munro, E. (2011a). The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report: A Child Centred System. www.education.gov.uk/munroreview/.

- Munro, E. (2011b). The Munro review of child protection: Interim report: The child’s journey. www.education.gov.uk/munroreview/.

- Parrott, L., & Madoc-Jones, I. (2008). Reclaiming information and communication technologies for empowering social work practice. Journal of Social Work, 8(2), 181–197. doi:10.1177/1468017307084739

- Parton, N. (2009). Challenges to practice and knowledge in child welfare social work: From the ‘social’ to the ‘informational’? Children and Youth Services Review, 31(7), 715–721. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.01.008

- Pasmore, W. A. (1995). Social science transformed: The socio-technical perspective. Human Relations, 48(1), 1–21. doi:10.1177/001872679504800101

- Peterson, J., Pearce, P. F., Ferguson, L. A., & Langford, C. A. (2017). Understanding scoping reviews. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 29(1), 12–16. doi:10.1002/2327-6924.12380

- Pithouse, A., Broadhurst, K., Hall, C., Peckover, S., Wastell, D., & White, S. (2012). Trust, risk and the (mis)management of contingency and discretion through new information technologies in children’s services. Journal of Social Work, 12(2), 158–178. doi:10.1177/1468017310382151

- Rolan, G., Evans, J., Bone, J., Lewis, A., Golding, F., Wilson, J., … Reeves, K. (2018). Weapons of affect: The imperative for transdisciplinary information systems design. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 55(1), 420–429. doi:10.1002/pra2.2018.14505501046

- Salovaara, S., & Ylönen, K. (2022). Client information systems’ support for case-based social work: Experiences of Finnish social workers. Nordic Social Work Research, 12(3), 364–378. doi:10.1080/2156857X.2021.1999847

- Sarwar, A., & Harris, M. (2019). Children’s services in the age of information technology: What matters most to frontline professionals. Journal of Social Work, 19(6), 699–718. doi:10.1177/1468017318788194

- Savaya, R., Monnickendam, M., & Waysman, M. (2006). Extent and type of worker utilization of an integrated information system in a human services agency. Evaluation and Program Planning, 29(3), 209–216. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2006.03.001

- Savaya, R., Spiro, S. E., Waysman, M., & Golan, M. (2004). Issues in the development of a computerized clinical information system for a network of juvenile homes. Administration in Social Work, 28(2), 63–79. doi:10.1300/J147v28n02_05

- Sawyer, A.-M. (2009). Mental health workers negotiating risk on the frontline. Australian Social Work, 62(4), 441–459. doi:10.1080/03124070903265724

- Seddon, J. (2008). Systems thinking in the public sector: The failure of the reform regime and a manifesto for a better way. Triarchy Press.

- Seniutis, M., Petružytė, D., Baltrūnaitė, M., Vainauskaitė, S., & Petkevičius, L. (2021). The impact of information system on interactions of child welfare professionals with managers and clients. Sustainability, 13(12), 6765. doi:10.3390/su13126765

- Shaw, I., Bell, M., Sinclair, I., Sloper, P., Mitchell, W., Dyson, P., … Rafferty, J. (2009). An exemplary scheme? An evaluation of the integrated children’s system. British Journal of Social Work, 39(4), 613–626. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcp040

- Shaw, I., & Clayden, J. (2010). Technology, evidence and professional practice: Reflections on the integrated children’s system. Journal of Children’s Services, 4(4), 15–27. doi:10.5042/jcs.2010.0018

- Smith, R. S., & Eaton, T. (2014). Information and communication technology in child welfare. The need for culture-centred computing. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 41(1), 137–160. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol41/iss1/8.

- Spensberger, F. (2019). The digitalization of a social work theory: Experiences of a German child welfare social worker. International Social Work, 62(6), 1575–1579. doi:10.1177/0020872819865018

- Stamoulis, D. S. (2020). Information systems for the social administration using the soft systems methodology. International Journal of Applied Systemic Studies, 9(1), 1–10. doi:10.1504/IJASS.2020.108655

- Stillman, L., Kethers, S., French, R., & Lombard, D. (2009). Adapting corporate modelling for community informatics. VINE, 39(3), 259–274. doi:10.1108/03055720911004003

- Stillman, L., & Linger, H. (2009). Community informatics and information systems: Can they be better connected? The Information Society, 25(4), 255–264. doi:10.1080/01972240903028706

- Stillman, L., & McGrath, J. (2008). Is it Web 2.0 or is it better information and knowledge that we need? Australian Social Work, 61(4), 421–428. doi:10.1080/03124070802441889

- Tjora, A. (2018). Qualitative research as stepwise-deductive induction. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203730072

- Tregeagle, S. (2016). Heads in the cloud: An example of practice-based information and communication technology in child welfare. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 34(2), 224–239. doi:10.1080/15228835.2016.1177479

- Trkman, P. (2010). The critical success factors of business process management. International Journal of Information Management, 30(2), 125–134. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2009.07.003

- Wang, B., Schlagwein, D., Cecez-Kecmanovic, D., & Cahalane, M. (2019). Beyond Bourdieu, Foucault and Habermas: Review and assessment of critical information systems research. ACIS 2019 Proceedings. https://aisel.aigsnet.org/acis2019/4.

- Wastell, D., Peckover, S., White, S., Broadhurst, K., Hall, C., & Pithouse, A. (2011). Social work in the laboratory: Using microworlds for practice research. British Journal of Social Work, 41(4), 744–760. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcr014

- Wastell, D., & White, S. (2014a). Beyond bureaucracy: Emerging trends in social care informatics. Health informatics Journal, 20(3), 213–219. doi:10.1177/1460458213487535

- Wastell, D., & White, S. (2014b). Making sense of complex electronic records: Socio-technical design in social care. Applied ergonomics, 45(2), 143–149. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2013.02.002

- Wastell, D., White, S., & Broadhurst, K. (2009). The chiasmus of design: Paradoxical outcomes in the e-government reform of UK children’s services. Springer, 257–272. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02388-0_18

- Wastell, D., White, S., Broadhurst, K., Peckover, S., & Pithouse, A. (2010). Children’s services in the iron cage of performance management: Street-level bureaucracy and the spectre of Švejkism. International Journal of Social Welfare, 19(3), 310–320. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2397.2009.00716.x

- Wastell, D. G., McMaster, T., & Kawalek, P. (2007). The rise of the phoenix: Methodological innovation as a discourse of renewal. Journal of Information Technology, 22(1), 59–68. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jit.2000086

- White, S., Broadhurst, K., Wastell, D., Peckover, S., Hall, C., & Pithouse, A. (2009). Whither practice-near research in the modernization programme? Policy blunders in children’s services. Journal of Social Work Practice, 23(4), 401–411. doi:10.1080/02650530903374945

- White, S., Wastell, D., Broadhurst, K., & Hall, C. (2010). When policy o’erleaps itself: The ‘tragic tale’ of the integrated children’s system. Critical Social Policy, 30(3), 405–429. doi:10.1177/0261018310367675

- Wilson, R., Martin, M., Walsh, S., & Richter, P. (2011). Re-mixing digital economies in the voluntary community sector? Governing identity information and information sharing in the mixed economy of care for children and young people. Social Policy and Society, 10(3), 379–391. doi:10.1017/S1474746411000108

- Wilson, R., Walsh, S., & Vaughan, R. (2007). Developing an electronic social care record: A tale from the Tyne. Informatics in Primary Care, 15(4), 239–244. doi:10.14236/jhi.v15i4.664

- Wulf, V., Pipek, V., Randall, D., Rohde, M., Schmidt, K., & Stevens, G. (2018). Socio-informatics: A practice-based perspective on the design and use of IT artifacts. Oxford University Press.

- Yigitbasioglu, O., Furneaux, C., & Rossi, S. (2023). Case management systems and new routines in community organisations. Financial Accountability & Management, 39(1), 216–236. doi:10.1111/faam.12297

- Ylönen, K. (in press). The use of electronic information systems in social work. A scoping review of the empirical articles published between 2000 and 2019. European Journal of Social Work, 1–14. doi:10.1080/13691457.2022.2064433

- Zhang, W., & Gutierrez, O. (2007). Information technology acceptance in the social services sector context: An exploration. Social work, 52(3), 221–231. doi:10.1093/sw/52.3.221

- Zhu, H., & Andersen, S. T. (2021). ICT-mediated social work practice and innovation: Professionals’ experiences in the Norwegian labour and welfare administration. Nordic Social Work Research, 11(4), 346–360. doi:10.1080/2156857X.2020.1740774

- Zorn, T. E. (2003). The emotionality of information and communication technology implementation. Journal of Communication Management, 7(2), 160–171. doi:10.1108/13632540310807296

Appendix

Appendix Table A1. Key information of selected studies, by group.