ABSTRACT

The achievement of business sustainability is dependent on the interacting components of the entrepreneurship ecosystem (EE) and institutions that support or challenge the business environment. Given the importance of the informal economy in developing economies, we need to rethink how to start an informal entrepreneurial revolution. This article examines the nexus of the informal entrepreneurial ecosystem, from the perspective of ecological resilience. Specifically, the article analyzes the significant differences between the formal sector, the informal sector, frugal innovations, and the supportive ecosystem resilience that produces unparalleled enthusiasm. Conceptually, this article developed propositions and a model of Productive and Unproductive EE explaining the business environment and the interacting predictors from the African regional context. Arguably, as entrepreneurial education and skills increases, there is more likelihood of the creation of formal ventures and growth-oriented micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). These have implications for economic growth and – in the case of African economies – moving the informal to formal economy.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship ecosystem (EE) consist of interacting components and actors, which foster new firm creation and growth-oriented activities (Brown & Mason, Citation2017; Mack & Mayer, Citation2015; Maroufkhani, Wagner, Khairuzzaman, & Ismail, Citation2018). Isenberg (Citation2010, Citation2011) proposes that EE enables or hinders entrepreneurship development, growth, and productivity. In many African countries, the informal sector is a major contributor to the national economy, accounting for a significant portion of employment and between 25% and 65% of GDP (International Monetary Fund [IMF], Citation2017). Informal economy helps to create jobs, spur innovation, and reduce inequality by generating employment opportunities for minorities and disadvantaged groups (like youths and women in developing countries). However, little attention has been paid to the role of entrepreneurship in fostering economic growth in African economies (African Development Bank [ADB], Citation2013; Madichie, Hinson, & Ibrahim, Citation2013; Rwelamila & Ssegawa, Citation2014). A major challenge is how to move the informal sector to a formal economy, achieve efficient resource allocation and high output (Kim & Loayza, Citation2017; World Economic Forum, Citation2015).

EE influences the growth of entrepreneurship across locations, regions, and nations (Block, Fisch, & van Praag, Citation2017; Fishman, Don-Yehiya, & Schreiber, Citation2018). In the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM studies), Africa displays the highest levels of entrepreneurial intention (42%) while Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) report the highest capability perception (63%) and the second-highest rate of entrepreneurial intention (32%) (GEM, Citation2016/2017). The same pattern is observed in terms of societal value for entrepreneurship and capabilities perceptions (Mahoney & Michael, Citation2005). GEM report revealed that from a regional perspective, Africa shows the most positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship, with three-quarters of working-age adults considering entrepreneurship a good career choice while 77% believe that entrepreneurs are admired in their societies (GEM, Citation2016/2017). However, when it comes to nascent entrepreneurial activity (those who go on to commit resources to start a formal business), the African region lack behind LAC (GEM, Citation2016/2017).

A major question of this article is how to start an informal entrepreneurial revolution? Ecological resilience describes an ecosystem that can “absorb” disturbances and undergo the changes necessary to transform its essential behaviors, structures, and identity into a system that is better able to respond to disruptions (Roundy, Brockman, & Bradshaw, Citation2017). It is assumed that each ecosystem should be specific and idiosyncratic (Sheriff & Muffatto, Citation2015). EE has a significant influence on both the formal and informal economy, firms’ productivity, and level of entrepreneurship (Mathias, Solomon, & Madison, Citation2017). In the case of Africa, the majority of the population pursue entrepreneurial intentions but rather in the informal and low productive business activities (International Labor Organization [ILO], Citation2014). With a focus on the African economy, this article proposes strengthening the EE to support informal entrepreneurship, firm productivity, and growth-oriented productive entrepreneurship.

This is one of the foremost studies to draw on ecosystem resilience to analyze the African informal economy. Most entrepreneurship studies focus on the formal economy. Unfortunately, the increasing interest in formal entrepreneurship has left the informal economy under-researched (Freire-Gibb & Nielsen, Citation2014). Therefore, this article contributes to knowledge on the main determinants of productivity linked to the EE from a developing regional context. Lack of specification and conceptual limitations has undoubtedly hindered our understanding of EE from different contexts (Brown & Mason, Citation2017; Mason & Brown, Citation2014; Stam & Van De Ven, Citation2019). Also, this article contributes to defining EE, since it remains loosely defined (Brown & Mason, Citation2017). More so, this paper contributes to describing frugal innovations and the institutional perspectives of a challenging environment (Welter & Smallbone, Citation2011). Understanding institutional elements could form a solid base for the formulation of enabling supports and policies directed toward entrepreneurial revolution (Isenberg, Citation2010). Above all, an improved understanding of the EE has policy implications toward job creation, economic growth, innovation, and – in the case of African economies – poverty reduction, and the potential to formalize the informal sector (Kuckertz, Citation2019).

Although this study’s focus on informal entrepreneurship, most of the discussions also affect the formal entrepreneurship sector. The article is structured as follows: The next section examines the foundational theories of EE and ecological resilience, informal entrepreneurship, frugal innovations, and institutional logics. This is followed by the development of propositions and a model of Productive and Unproductive EE. Finally, the article concludes with an analysis of the critical challenges and implications for growth-oriented entrepreneurship, research, practice, and policy.

Entrepreneurship ecosystem and ecological resilience

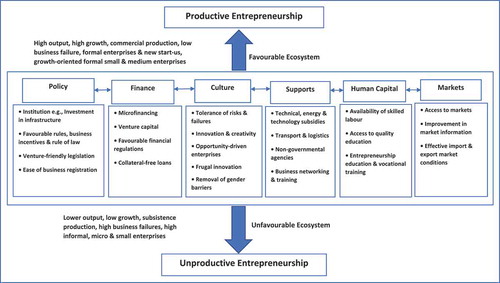

An evolutionary concept of EE explains the factors of the surrounding environment that support or hinder entrepreneurship growth (Roundy, Citation2017; Sheriff & Muffatto, Citation2015). EE model consists of six main elements that are Policy, Finance, Culture, Supports, Human Capital and Markets (Isenberg, Citation2011). Within these six domains, there are several hundreds of elements interacting in highly complex and idiosyncratic ways (Isenberg, Citation2014). The evolving ecosystem consists of actors that govern, integrate, and perform all of the functions required for entrepreneurship to flourish in any territory that becomes an important source of innovation, productivity growth and source of employment (Stam & Van De Ven, Citation2019). EE approach has been adopted in many studies (Brown & Mason, Citation2017; Maroufkhani et al., Citation2018; Stam & Van De Ven, Citation2019). Despite its popularity, the definitions are varied (Brown & Mason, Citation2017). It remains loosely defined and measured; hence, requires definitional clarification ().

Table 1. Definitions of entrepreneurial ecosystem

EE offers both a theoretical and practical perspective (Beliaeva, Ferasso, Kraus, & Damke, Citation2020; Brown & Mason, Citation2017; Stam & Van De Ven, Citation2019). Although the idea of EE and its application somehow has been embraced by researchers and policymakers, some scholars caution that the concept should be treated with care, as the metaphor risks being vague and its boundaries blurry (Bruns, Bosma, Sanders, & Schramm, Citation2017; Kuckertz, Citation2019). EE is known to produce informal, formal, productive, and unproductive entrepreneurship depending on the interreacting factors. Ecological resilience or ecological robustness describes the ability of an ecosystem to maintain its normal patterns of nutrient cycling and biomass production after being subjected to damage caused by an ecological disturbance (Levin, Citation2015).

Ecosystem resilience explains the ability of the EE to respond to disruptions that are changing, adapting, and evolving over time. Resilience can be defined as the ability of a system to maintain its state by absorbing both internal and external changes and disturbances to its variables and parameters (Özkundakci & Lehmann, Citation2019). Over time, the concepts of ecosystem resilience have become prominent in the scientific and management literature (Falk, Watts, & Thode, Citation2019). Ecosystem resilience applies to post-disturbance response, but resilient responses are emergent properties resulting from component processes of persistence, recovery, and reorganization (Falk et al., Citation2019). One of the most important concepts related to resilience is the notion that complex systems can exhibit non-equilibrium conditions and exist in various alternative states that differ in processes, structures, functions, and feedbacks (Chambers, Allen, & Cushman, Citation2019).

Informality and African economy

Different definitions of informality have been used in the literature based on different conceptual understandings related to the size of the firm, size of employees, the legal status of employment, social protection status, tax compliance, etc. For example, Pradhan and van Soest (Citation1997) and Maloney (Citation1999) use definitions classifying firms employing fewer than six employees as informal in their studies of Bolivia and Mexico respectively. The informal sector takes the form of self-employment (often regarded as survival activities for marginalized workers) (Ram, Edwards, Jones, & Villares-Varela, Citation2017). Other attributes of informality include being unregistered, usually unlicensed, and typically do not pay taxes (Igwe et al., Citation2020; Igwe, Madichie, & Newbery, Citation2019). The informal economy does not cover illicit activities but focuses on legal activities (Maloney, Citation2004; OECD, Citation2019). A range of alternative definitions of informal activity implying very different conceptual understandings and views are summarized in .

Table 2. Views and definitions of informal economy

According to the African Development Bank (ADB, Citation2013), 9 out of 10 rural and urban workers have informal jobs in Africa and most employees are women and youths. Examples of informal jobs include artisans, market traders, street traders, subsistence farmers, small-scale manufacturers, service providers (e.g. hairdressers, private taxi drivers, and carpenters), etc. It is estimated that more than 60% of the African population in employment is in the informal economy (ILO, Citation2018; World Bank, Citation2016). Besides the problem of informality, African economies are characterized by several interacting components, features, and disruptions that are changing, adapting, and evolving (as presented in ).

Table 3. African entrepreneurial ecosystem environment

As revealed by several studies (), the majority of African economies lack adequate institutional supports for entrepreneurship leading to the ecosystem that produces a high rate of informal micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) which are low growth-oriented. As a result, many economies are over-dependent on locally sourced materials, mobile technology, and local technology hubs supporting frugal innovations (Ekekwe, Citation2016). Therefore, frugal innovation has emerged as a novel approach toward improving EE (Beliaeva et al., Citation2020; Igwe et al., Citation2020; Meagher, Citation2018). Frugal innovation is the ability to ‘do better with fewer resources for more people or the ability to maximize the ratio of value to resources for customers, shareholders, or society (Prabhu, Citation2017).

Researchers and policymakers are interested in determining whether and to what extent the development and production of so-called frugal innovations contribute to economic development? (see, for example, Meagher, Citation2018). It is believed that EE provides a rich background for risk-taking, innovative and visionary entrepreneurship, thereby enabling the productive use of limited resources to be better targeted and more focused on optimum returns (Brown & Mason, Citation2017; Pereira et al., Citation2019; Saúde, Hermozilha, & Borrero, Citation2020). Igwe et al. (Citation2020) developed a model of a frugal innovation ecosystem that is dependent on formal/informal rules, access to market, access to resources and entrepreneurial culture ().

As shown by the model (), frugal innovations and informal entrepreneurship develop in response to technological, economic, social, and cultural barriers that exist in many African economies. Depending on the support services or policies, informal entrepreneurship produces effective knowledge flows, information sharing, networking, and resource sharing. These outcomes or responses provide an ecosystem of resilience, resistance, recovery, and sustainability. It is believed that frugal innovation is fueled by need, the science and art of using the little available resources to solve problems (Thoughtwork, Citation2014).

Institutional logic

Developing strong institutions is an excellent starting point toward starting an entrepreneurial revolution (Isenberg, Citation2010). Institutions are formal rules (i.e. laws and regulations) and informal rules (i.e. norms, values, beliefs, religion, etc.) that guide individual behavior (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1991; North, Citation1990). Institutional logics has been applied to explain why the levels of entrepreneurship vary from one location to another (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1991; Naudé, Citation2010). Institutions are maintained through repeated endorsement by individuals engaging in social interactions that become entrenched when people perform the patterns of behavior encrypted in them until any other behavior becomes unthinkable (Seo & Creed, Citation2002). Culture is directly associated with the informal institution. Informal business practices occur outside of formal regulations and are guided by informal norms, values, and understanding (Sutter, Webb, Kistruck, Ketchen, & Ireland, Citation2017). Entrepreneurship is inextricably linked to institutions and the sociocultural system (Ajekwu, Citation2017; Anggadwita, Ramadani, & Ratten, Citation2017).

Sometimes, the cultural richness of regions is often ignored in economic development initiatives (Mack & Mayer, Citation2015). This perspective describes how institutional and cultural elements are embedded, become manifest in the actions of individuals and organizational change (Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, Citation2012; Williams & Vorley, Citation2015). High-growth entrepreneurship thrives in favorable economic and institutional environments that enhance the expected returns of innovation (Kim & Loayza, Citation2017; World Bank, Citation2014). There have been several studies examining the experiences and lessons from formalization initiatives in developing economies (Abdallah, Citation2017; Amésquita, Morales, & Rees, Citation2018; Igwe et al., Citation2019; Olomi, Charles, & Juma, Citation2018). Feldman and Lowe (Citation2017) maintain that among institutions, government is arguably the best-equipped actor in the economy to make large-scale investments in infrastructure and education. To promote economic growth, governments often introduce policies and new regulations aimed at promoting entrepreneurship. Often unforeseen outcomes from insufficient regulation can undermine policies designed to promote entrepreneurship and lead to the emergence of informal activities and hidden enterprise culture (Al-Mataani, Wainwright, & Demirel, Citation2017).

Productive and unproductive entrepreneurial ecosystem

There is a diversity of EE, institutions, and actors. The diversity of EE determines whether an economy develops into the formal or informal sector and productive or unproductive entrepreneurship. The emergence of either sector depends on the nature of the institutional framework described within the EE including policy framework, finance, culture, supports, human capital, and markets. An entrepreneur is a person who identifies a business opportunity, acquires the necessary physical and human capital to start a new venture, and operationalizes it and is responsible for its success or failure. A mapping of the EE illustrates the actors’ roles, which indicates their importance and the interconnectedness between them. Understanding institutional logics can provide an appropriate interpretative frame to examine how to start an informal entrepreneurial revolution. Therefore, the emerging EE has several evolving dimensions and propositions.

Proposition 1: Depending on the entrepreneurship ecosystem resilience, productive or unproductive entrepreneurship and the formal or informal economy will dominate.

Depending on EE formal or informal entrepreneurship will emerge and the differences of the two types of ecosystems have important implications for EE resilience. Indeed, EE influence the ease with which entrepreneurs decide either to operate in a formal or informal system. The informal sector has a small layer that responds to the simplification of regulations and a larger one that requires a different formalization framework (Olomi et al., Citation2018). The formalization of informal firms within the fold of the formal sector has been suggested as the possible solution to poverty reduction in low-income countries (World Bank, Citation2016).

However, the transition to the formal sector has been notoriously difficult to achieve and slow in most countries. Formal and informal rules are components of institutions that influence the levels of entrepreneurship and variation of entrepreneurship by location, country, regions, etc. Therefore, the institutional setting could be divided into urban and rural. When measured against all indicators, the rural sector is the worst off. As a result, people living in rural areas are almost twice as likely to be in informal employment as those in urban areas and agriculture is the sector with the highest level of informal employment (ILO, Citation2018).

Proposition 2: As entrepreneurship education and awareness increases, there is more likelihood of the creation of formal ventures and growth-oriented entrepreneurship.

Among the critical resources required to develop a productive economy is quality education. One of the debates in the current society is can entrepreneurship be learned or can people be trained and motivated to develop entrepreneurial intentions (Igwe, Okolie, & Nwokoro, Citation2021; Okolie et al., Citation2021). There is consensus that entrepreneurship education and the development of employability skills and knowledge contributes to making an individual adapt to changes in the labor market (Igwe, Lock, & Rugara, Citation2020). As an economy grows it requires skilled entrepreneurs and labor. Sustainable development at all levels in society requires reorienting education and helping people develop knowledge, skills, values, and behaviors.

In developing economies, informal entrepreneurs face a myriad of challenges including poor knowledge of product and market, poor network and resource sharing. The entrepreneurship education approach is often applied to promote entrepreneurial awareness (based on learning-about entrepreneurship, learning-to-do and knowledge about business start-up) that helps to develop the competencies necessary to identify and act on opportunities. Achievement of entrepreneurial culture and competencies require a pedagogical shift in the mind-set of teachers to make their teaching more entrepreneurial (Costa, Santos, Wach, & Caetano, Citation2018; Eijdenberg, Isaga, Paas, & Masurel, Citation2021; Lackéus & Sävetun, Citation2019).

Entrepreneurial resources include tangible and intangibles resources such as human capital (know-how or tacit knowledge, skills, and labor quality), financial, buildings, machinery, etc. These are important factors that determined business sustainability (Sallah & Caesar, Citation2020). The low level of education is a key factor affecting the level of informality and when the level of education increases, the level of informality decreases (ILO, Citation2018). The argument is that because entrepreneurship education focuses on raising entrepreneurial awareness and mind-set, it requires the adoption of educational approaches focusing on cognition (Costa et al., Citation2018). Also, entrepreneurship education can increase the competencies and innovation required for the creation of growth-oriented ventures (Roundy, Citation2017).

Proposition 3: High-growth entrepreneurship and growth-oriented ventures depend on the entrepreneurship environment and the ecosystem resilience.

The political, economic, cultural, social, technological, and legal environment are key determinants of EE and ecosystem resilience. Entrepreneurship development and growth depend so much on external factors such as demand conditions, access to markets, access to information, access to infrastructure, access to finance, import and export conditions. These act as either facilitator or barriers (Amésquita et al., Citation2018). The role of government is critical for the development of EE. Although evidence on the impact of government incentives and policy intervention (e.g. grants or subsidy) is mixed, there is evidence that both forms of policy intervention can be effective if appropriately designed and tailored to context (European Commission, Citation2017).

Internal factors (such as level of capital, size of the firm, managerial competencies, entrepreneurial orientation, experience, skills and knowledge) is another key determinant of growth-oriented EE. Some studies compare the impact of the interactions between organizational capabilities and business strategic orientation on performance for micro and small business (Agyapong & Acquaah, Citation2021). Arguably, the institutional environment, entrepreneurship stakeholders and culture are the three critical exogenous variables that determine the EE within a region. Stakeholder of entrepreneurship refers to groups or actors that either affect or be affected by the business environment. Although there are many EE actors, components, and factors involved in the formation of an EE, most of these factors are locally based (OECD, Citation2014; Sheriff & Muffatto, Citation2015).

Isenberg (Citation2011) maintains that every EE is unique as it develops under idiosyncratic circumstances. Hence, EE determines whether a formal or informal economy will dominate. represents a model of Productive and Unproductive EE developed from Isenberg (Citation2010, Citation2011) six EE interdependent actors that include policy, finance, culture, supports, human capital and markets. Where EE are unfavorable and less resilient, unproductive entrepreneurship (informal economy) will emerge. In a productive environment, output and firm growth will be higher, while in the unproductive environment, the result will be low output and high prevalence of informal micro-enterprises.

The model of Productive and Unproductive EE reveals a set of interconnected forces which formally and informally coalesce to connect, mediate and determine the entrepreneurial performance within the local, national and regional environment. Government is an important EE actor and stakeholder. Government support increases the coherence of EE participants’ intentions, behaviors, and outcomes (Friedman, Citation2011). The government ensures that the prevalent EE within their domain can respond and adapt to disturbances by introducing policies that enable businesses to access resources, experiment, research, innovate and adapt technology. Governments invest in infrastructures and provide subsidies to encourage production and demand. Ease of business registration, the removal of import and export barriers could spur informal entrepreneurs to transit to the formal sector. Also, the promotion of robust entrepreneurship education, university research and schemes such as apprenticeship education, employability education, career and counseling will be critical to the development of EE resilience.

Previous studies reveal that early-stage transition economies are typically characterized by ineffective formal institutions, which combine with weak or absent enforcement mechanisms (Welter & Smallbone, Citation2011). Although the impact of the institutional factor on entrepreneurship is mixed (positive and negative), it is generally agreed that conducive EE policies support necessary resources that promote innovations and productive start-ups (Mukiza & Kansheba, Citation2020; World Economic Forum, Citation2015). To start an entrepreneurial revolution, entrepreneurs and stakeholders must operate within some degree of common agenda to develop an EE environment that can be resilient against the market and non-market forces. A revolution of the informal economy will complement the government efforts in providing employment and making the national economy viable.

Discussion

This article examined the determinants of EE and ecosystem resilience that enable informal entrepreneurial revolution. An unproductive economy or high incidence of informality in all its forms has multiple adverse consequences to the local, national, and regional economies. On the positive assessment, the informal economy offers significant job creation and income generation potential, as well as the capacity to meet the needs of poor consumers by providing cheaper and more accessible goods and services (Bank of Industry [BOI], Citation2018). Also, the informal sector is crucial to the development of the urban economy. However, a high rate of informality has negative consequences such as tax evasion, lower wages, poor working conditions, lower productivity, and low economic growth.

African economies are dominated by the informal agricultural sector which produces 70% of the economy’s total employment (United States Agency for International Development [USAID], Citation2016). There is a significant difference in growth between firms in the formal sector and informal sector (Abdallah, Citation2017; Ghecham, Citation2010). Many African economies have recorded an increase in the growth of agriculture, manufacturing, consumer trade, construction, and other services. However, these sectors have maintained modest increases in productivity which have not supported job growth (USAID, Citation2016). More so, the growth is too low to lift the bottom half of the population out of poverty (World Bank, Citation2020). Besides, there is high level of corruption, high rate of crime, lack of access to capital, and poor state of infrastructure which stifle entrepreneurs who aspire to start a new business or grow their business (United States Agency for International Development [USAID], Citation2016). Although corruption helps to speed up decisions in developing countries, it deters entrepreneurs unwilling to engage in the practices, encourages illegal activities, black markets and loss of government revenues.

Arguably, the high rate of poverty in African is both a cause and a consequence of informality (ILO, Citation2018). However, it does not always translate that an informal entrepreneur would be better off as a formal entrepreneur (Maloney, Citation2004). The conditions of the EE have a greater impact on performance and productivity, regardless of the context (that is informal or formal economy). According to the report by McKinsey Global Institute (Citation2014), African economic growth has been driven primarily by improving productivity. However, historical weaknesses in the agricultural sector and a poorly functioning urbanization process have prevented most citizens from benefiting from this growth (McKinsey Global Institute, Citation2014).

The outcome of the dominant informal ecosystem (Trading Economics, Citation2020) is that employment creation remains weak and insufficient to absorb the fast-growing labor force, resulting in a high rate of unemployment (World Bank, Citation2020). Although entrepreneurship education and awareness have become popular in many societies, the pedagogy of teaching and learning are weak to make significant changes (Igwe et al., Citation2019; Nwajiuba, Igwe, Akinsola-Obatolu, Icha-Ituma, & Binuomote, Citation2020b; Okolie, Igwe, Eneje, Nwosu, & Mlanga, Citation2019). Historically, interventions in the informal sector have been focused on how to regulate businesses, and effectively integrate them into the formal economy (Bank of Industry [BOI], Citation2018). As such, limited emphasis has been given to identifying the drivers of growth, building sustainable EE resilience and overcoming environmental challenges.

Conclusion and implications

The EE and ecosystem resilience determine the responses to the disruptions, changes, adaptions, and evolving of entrepreneurship over time. To start an informal entrepreneurial revolution, policymakers need to rethink policies, informal and formal regulations. The marginalization of the informal sector needs to change, and policies need to focus on how to improve the sector to make it more productive and resourceful. For instance, the provision of readily accessible microfinancing, small business training, educational apprenticeship and small-scale start-up funding will encourage entrepreneurs to develop business activities in the formal sector. Although there is consensus that creating conducive EE could be useful road maps for economic growth and poverty reduction in Africa (Sheriff & Muffatto, Citation2015), creating productive EE poses various challenges for policymakers (Mason & Brown, Citation2014).

EE typically represent the greatest challenge for economic growth. In this article, frugal, ecosystem resilience and EE assessments are based on an understanding of ecosystem landscape, the composition and configuration in response to disturbances, market and non-market forces. Policies aimed at institutional supports and investments are critical for the development of a favorable business environment. Some policies promote friendly EE such as simplifying business registration, export licensing procedures, favorable business taxation, access to finance, improvement in legal processes, access to market information, improvement of human capital competencies, entrepreneurship education and employability skills. However, many governments take a misguided approach toward developing favorable entrepreneurship policies (Friedman, Citation2011).

The model of Productive and Unproductive EE provide insights on how to start an informal entrepreneurial revolution to promote entrepreneurship and economic growth. Entrepreneurship has benefits to workers, firms, government and societies and is crucial for the achievement of sustainable development, inclusive development, reduction in inequality and poverty. It provides a foundation for innovation, effective resource allocation and value creation. In the light of the role of the informal sector in developing countries in meeting the economic dimension of sustainable development, there is a need for studies to focus on informal sector to understand and explore how to support and enable the sector.

It is important to note that a key challenge in many developing countries is the lack of interactions of the key actors of EE. In developing economies, some programmes have a positive effect and incremental results such as investment in agriculture, investment in information and communication technology (ICT), technological, green energy, road, railways, transport, high-quality education and health care. The integration of ecosystem resilience with the EE concept provides the basis for understanding how ecosystem structures interact to influence the types of entrepreneurial activities, disturbances, stressors and the capacity of the EE to support productive entrepreneurship or formal entrepreneurship.

Given the importance of the informal sector to employment and income generation to the poor and vulnerable population, we need to rethink the informal economy. Therefore, the EE concept offers both theoretical, practical and policy perspectives (Brown & Mason, Citation2017). These perspectives present opportunities to examine the state of entrepreneurship, EE actors and the role that governments play in the development of EE and ecosystem resilience. There is a need for more studies to focus on analyzing the EE, the environment, institutions, and prevailing culture. Future research should focus on the exploration of constraints most relevant to African countries and how to integrate frugal innovation with industrial and technological innovations to promote sustainable development and EE resilience.

Acknowledgement

This article has not been published or submitted elsewhere. We would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their recommendations that led to improvement of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdallah, G. K. (2017). Differences between firms from the formal sector and the informal sector in terms of growth: Empirical evidence from Tanzania. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 9(2), 121–143.

- Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Licht, G. (2016). National systems of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 46(4), 527–535.

- African Development Bank. (2013, March 27). Recognizing Africa’s informal sector. Retrieved from https://www.afdb.org/en/blogs/afdb-championing-inclusive-growth-across-africa/post/recognizing-africas-informal-sector-11645/

- Agyapong, A., & Acquaah, M. (2021). Organizational capabilities, business strategic orientation, and performance in family and non-family businesses in a sub-Saharan African Economy. Journal of African Business, 1–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2021.1907158

- Ajekwu, C. C. (2017). Effect of culture on entrepreneurship in Nigeria. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 6(2), 1–6.

- Al-Mataani, R., Wainwright, T., & Demirel, P. (2017). Hidden entrepreneurs: Informal practices within the formal economy. European Management Review, 14(4), 361–376.

- Amésquita, C. F., Morales, O., & Rees, G. H. (2018). Understanding the intentions of informal entrepreneurs in Peru. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 10(3), 489–510.

- Anggadwita, G., Ramadani, V., & Ratten, V. (2017). Sociocultural environments and emerging economy entrepreneurship women entrepreneurs in Indonesia. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 9(1), 85–96.

- Bank of Industry. (2018, May). Economic development through the Nigerian Informal Sector: A BOI perspective (Working Paper Series, 2). Retrieved from https://www.boi.ng/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/BOI-Working-Paper-Series-No2_Economic-Development-through-the-Nigerian-Informal-Sector-A-BOI-perspective.pdf

- Beliaeva, T., Ferasso, M., Kraus, S., & Damke, E. (2020). Dynamics of digital entrepreneurship and the innovation ecosystem: A multilevel perspective. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(2), 266–284.

- Block, J. H., Fisch, C. O., & van Praag, M. (2017). The Schumpeterian entrepreneur: A review of the empirical evidence on the antecedents, behaviour and consequences of innovative entrepreneurship. Industry and Innovation, 24(1), 61–95.

- Brown, R., & Mason, C. (2017). Looking inside the spiky bits: A critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 11–30.

- Bruns, K., Bosma, N., Sanders, M., & Schramm, M. (2017). Searching for the existence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A regional cross-section growth regression approach. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 31–35.

- Chambers, J. C., Allen, C. R., & Cushman, S. A. (2019). Operationalizing ecological resilience concepts for managing species and ecosystems at risk. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 241–259.

- Chen, G., & Hamori, S. (2009). Formal employment, informal employment and income differentials in Urban China (MPRA Paper, No. 17585). posted 30 Sep 2009 08:27 UTC. Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/17585/

- Costa, S. F., Santos, S. C., Wach, D., & Caetano, A. (2018). Recognizing opportunities across campus: The effects of cognitive training and entrepreneurial passion on the business opportunity prototype. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(1), 51–75.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). Introduction. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Eijdenberg, E. L., Isaga, N. M., Paas, L. J., & Masurel, E. (2021). Fluid entrepreneurial motivations in Tanzania. Journal of African Business, 22(2), 171–189.

- Ekekwe, N. (2016, July 11). Why African entrepreneurship is booming? Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2016/07/why-african-entrepreneurship-is-booming

- European Commission. (2017). Effectiveness of tax incentives for venture capital and business angels to foster the investment of SMEs and start-ups (Final Report, TAXUD/2015/DE/330, FWC No. TAXUD/2015/CC/131). Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/sites/taxation/files/taxation_paper_69_vc-ba.pdf

- Ezeoha, A. E., & Icha-Ituma, A. (2017). Barriers to business development in Nigeria. In A. Akinyoade, T. Dietz, & C. Uche (Eds.), Entrepreneurship in Africa series: African dynamics (p. 15). Netherlands: BRILL.

- Falk, D. A., Watts, A. C., & Thode, A. E. (2019). Scaling ecological resilience. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 275–292.

- Feldman, M., & Lowe, N. (2017). Evidence-based economic development policy. Innovations, 11(3/4), 1–18.

- Fishman, A., Don-Yehiya, H., & Schreiber, A. (2018). Too big to succeed or too big to fail? Small Business Economics, 51(4), 811–822.

- Freire-Gibb, L. C., & Nielsen, K. (2014). Entrepreneurship within urban and rural areas: Creative people and social networks. Regional Studies, 48(1), 139–153.

- Friedman, B. A. (2011). The relationship between governance effectiveness and entrepreneurship”. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(17), 221–235.

- GEM. (2015). Africa’s young entrepreneurs: Unlocking the Potential for a better future. Retrieved May 06, 2018, from https://www.idrc.ca/sites/default/files/sp/Documents%20EN/Africas-Young-Entrepreneurs-Unlocking-the-Potential-for-a-Brighter-Future.pdf

- GEM. (2016/2017). Global report. Retrieved from https://www.babson.edu/Academics/centers/blank-center/global-research/gem/Documents/GEM%202016-2017%20Global%20Report.pdf

- GEM. (2018). Global report. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/SurfBook/Downloads/rev-gem-2017-2018-global-report-revised-1527266790-1548584425-1549359513.pdf

- Ghecham, M. A. (2010). How the interaction between formal and informal institutional constraints determines the investment growth of firms in Egypt. Journal of African Business, 11(2), 163–181.

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. (2014). Africa’s young entrepreneurs: Unlocking the potential for a better future. UK: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Retrieved November 25, 2017, from file:///H:/Downloads/1425737316GEM_UK_2014_final.pdf

- Guma, P. K. (2015). Business in the urban informal economy: Barriers to women’s entrepreneurship in Uganda. Journal of African Business, 16(3), 305–321.

- Igwe, P. A. (2020). Determinants of household income and employment choices in the rural agripreneurship economy. Studies in Agricultural Economics, 122(2), 96–103.

- Igwe, P. A., Amaugo, A. N., Ogundana, O. M., Egere, O. M., & Anigbo, J. A. (2018). Factors affecting the investment climate, SMEs productivity and entrepreneurship in Nigeria. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 7(1), 182–200.

- Igwe, P. A., Hack-polay, D., Mendy, J., Fuller, T., & Lock, D. (2019). Improving higher education standards through reengineering in West African Universities - A case study of Nigeria. Studies in Higher Education, 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1698534

- Igwe, P. A., Lock, D., & Rugara, D. G. (2020). What factors determine the development of employability skills in Nigerian higher education? Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2020.1850319

- Igwe, P. A., Madichie, N. O., & Newbery, R. (2019). Determinants of livelihood choices and artisanal entrepreneurship in Nigeria. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(4), 674–697.

- Igwe, P. A., Ochinanwata, C., & Madichie, N. O. (2021). The ‘Isms’ of regional integration: What do underlying interstate preferences hold for the ECOWAS Union? Politics & Policy, 49(2), 280–308.

- Igwe, P. A., Odunukan, K., Rahman, M., Rugara, D. G., & Ochinanwata, C. (2020). How entrepreneurship ecosystem influences the development of frugal innovation and informal entrepreneurship? Thunderbird International Business Review, 62(5), 475–488.

- Igwe, P. A., Okolie, U. C., & Nwokoro, C. V. (2021). Towards a responsible entrepreneurship education and the future of the workforce. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100300.

- ILO. (2014). Transitioning from the informal to the formal economy. International Labour Conference 103rd Session 2014, Report, V(1), International Labour Office, Geneva.

- ILO. (2018). Informal economy. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_627189/lang--en/index.htm

- International Labour Organization. (1993, January). Resolutions concerning statistics of employment in the informal sector. Adopted by the 15th International Conference of Labour Statisticians, para. 5, Geneva. Retrieved from https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=1350

- International Monetary Fund. (2017, July 10). The informal economy in Sub-Saharan Africa: Size and determinants (Working Paper No. 17/156). Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2017/07/10/The-Informal-Economy-in-Sub-Saharan-Africa-Size-and-Determinants-45017

- Isenberg, D. (2014). What an entrepreneurship ecosystem actually is? Harvard Business Review, [Online]. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2014/05/what-an-entrepreneurial-ecosystem-actually-is

- Isenberg, D. J. (2010). How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 40–50.

- Isenberg, D. J. (2011). The entrepreneurship ecosystem strategy as a new paradigm for economic policy: Principles for cultivating entrepreneurship. Paper presented at the Institute of International and European Affairs, Dublin.

- Kellermanns, F., Walter, J., Crook, T. R., Kemmerer, B., & Narayanan, V. (2016). The resource-based view in entrepreneurship: A content-analytical comparison of researchers’ and entrepreneurs’ views. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 26–48.

- Kim, Y., & Loayza, N. V. (2017). Productivity and its determinants: Innovation, education, efficiency, infrastructure, and institutions. The World Bank. Retrieved from http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/378031511165998244/Productivity-and-its-determinants-25-October-2017.pdf

- Kuckertz, A. (2019). Let’s take the entrepreneurial ecosystem metaphor seriously”. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 11, 1–24.

- Lackéus, M., & Sävetun, C. (2019). Assessing the impact of enterprise education in three leading Swedish compulsory schools. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(sup1), 33–59.

- Levin, S. (2015). Ecological resilience. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/science/ecological-resilience

- Mack, E., & Mayer, H. (2015). The evolutionary dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Urban Studies, 53(10), 2118–2133.

- Madichie, N. O. (2009). Breaking the glass ceiling in Nigeria: A review of women’s entrepreneurship. Journal of African Business, 10(1), 51–66.

- Madichie, N. O., Hinson, R. E., & Ibrahim, M. (2013). A reconceptualization of entrepreneurial orientation in an emerging market insurance company. Journal of African Business, 14(3), 202–214.

- Madichie, N. O., Nkamnebe, A. D., & Idemobi, E. I. (2008). Cultural determinants of entrepreneurial emergence in a typical sub-Sahara African context. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 2(4), 285–299.

- Mahoney, J. T., & Michael, S. C. (2005). Resources, capabilities and entrepreneurial perceptions (working paper). The University of Illinois at Urbana−Champaign Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7af1/71ddab9b9fc5e6fa6b920cce6c6d553be441.pdf

- Maloney, W. F. (2004). Informality revisited. World Development, 32(7), 1159–1178.

- Maloney, W.F. (1999). Does informality imply segmentation in urban labor markets? Evidence from sectoral transitions in Mexico. World Bank Economic Review,13(2): 275–302.

- Maroufkhani, P., Wagner, R., Khairuzzaman, W., & Ismail, W. (2018). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: A systematic review. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 12(4), 545–564.

- Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth-oriented entrepreneurship. Background paper prepared for the workshop organised by the OECD LEED Programme and the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, The Hague, Netherlands, 7th November 2013. Final Version: January 2014. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/entrepreneurial-ecosystems.pdf

- Mathias, B. D., Solomon, S. J., & Madison, K. (2017). After the harvest: A stewardship perspective on entrepreneurship and philanthropy. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(4), 385–404.

- McGowan, P., Cooper, S., Durkin, M., & O’Kane, C. (2015). The influence of social and human capital in developing young women as entrepreneurial business leaders. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(3), 645–661.

- McKinsey Global Institute. (2014). Nigeria’s renewal: Delivering inclusive growth in Africa’s largest economy. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/Middle%20East%20and%20Africa/Nigerias%20renewal%20Delivering%20inclusive%20growth/MGI_Nigerias_renewal_Full_report.ashx

- Meagher, K. (2018). Cannibalizing the informal economy: Frugal innovation and economic inclusion in Africa”. The European Journal of Development Research, 30(2), 17–33.

- Mukiza, J., & Kansheba, P. (2020). Small business and entrepreneurship in Africa: The nexus of entrepreneurial ecosystems and productive entrepreneurship. Small Enterprise Research, 27(2), 110–124.

- Mwobobia, F. (2012). The challenges facing small-scale women entrepreneurs: A case of Kenya. International Journal of Business Administration, 3, 112–121.

- Naudé, W. (2010). Entrepreneurship, developing countries, and development economics: New approaches and insights. Small Business Economics, 34(1), 1–12.

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Nwajiuba, C. A., Igwe, P. A., Akinsola-Obatolu, A. D., Icha-Ituma, A., & Binuomote, M. O. (2020b). What can be done to improve higher education quality and graduate employability? A Stakeholder approach. Industry and Higher Education, 34(5), 358–367.

- Nwajiuba, C. A., Igwe, P. A., Binuomote, M. O., Nwajiuba, A. O., & Nwekpa, K. C. (2020a). The barriers to high-growth enterprises: What do businesses in Africa experience? European Journal of Sustainable Development, 9(1), 1–18.

- OECD. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth-oriented entrepreneurship. Paris: Author. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/entrepreneurial-ecosystems.pdf

- OECD. (2017). Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2017. Paris: Author. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/entrepreneur_aag-2017-en

- OECD. (2019). Tackling vulnerability in the informal economy (pp. 155–165). Author. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/tackling-vulnerability-in-the-informal-economy_103bf23e-en

- Okolie, U. C., Ehiobuche, C., Igwe, P. A., Agha-Okoro, M. A., & Onwe, C. C. (2021). Women entrepreneurship and poverty alleviation: Understanding the economic and socio-cultural context of the Igbo Women’s basket weaving enterprise in Nigeria. Journal of African Business, 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2021.1874781

- Okolie, U. C., Igwe, P. A., Ayoola, A. A., Nwosu, H. E., Kanu, C., & Mong, I. K. (2021, March). Entrepreneurial competencies of undergraduate students: The case of universities in Nigeria. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100452.

- Okolie, U. C., Igwe, P. A., Eneje, B. C., Nwosu, H., & Mlanga, S. (2019). Enhancing graduate employability: Why do higher education institutions have problems with teaching generic skills? Policy Futures in Education, 18(2), 294–313.

- Olomi, D., Charles, G., & Juma, N. (2018). An inclusive approach to regulating the second economy: A tale of four Sub-Saharan African economies. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 10(3), 447–471.

- Özkundakci, D., & Lehmann, M. K. (2019). Lake resilience: Concept, observation and management. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 53(4), 481–488.

- Pereira, R., Ribeiro, M. C., Manuel, O., Marques, M., Rua, L., & Martins, D. (2019). Is there entrepreneurship within the public sector? A literature review. Handbook of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Opportunities for Global Economic Growth. Chapter 005, IGI Global. Retrieved from https://www.irma-international.org/chapter/is-there-entrepreneurship-within-the-public-sector/216639/

- Prabhu, J. (2017). Frugal innovation: Doing more with less for more. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 375(2095), 2016037220160372.

- Pradhan, M., & van Soest, A. (1997). Household Labor supply in urban areas of Bolivia. Review of Economics and Statistics, 79(2), 300–310.

- Ram, M., Edwards, P., Jones, T., & Villares-Varela, M. (2017). From the informal economy to the meaning of informality: Developing theory on firms and their workers. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 37(7/8), 361–373.

- Ratten, V., & Jones, P. (2018). Bringing Africa into entrepreneurship research. In L.-P. Dana, B. Q. Honyenuga, & V. Ratten (Eds.), Challenges and opportunities for doing business, Palgrave studies of entrepreneurship in Africa. Cheltenham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Roundy, P. T. (2017). Social entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems: Complementary or disjoint phenomena? International Journal of Social Economics, 44(9), 1252–1267.

- Roundy, P. T., Brockman, B. K., & Bradshaw, M. (2017). The resilience of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8(2017), 99–104.

- Rwelamila, P. D., & Ssegawa, J. K. (2014). The African project failure syndrome: The conundrum of project management knowledge base - The case of SADC. Journal of African Business, 15(3), 211–224.

- Sallah, C. A., & Caesar, L. D. (2020). Intangible resources and the growth of women businesses: Empirical evidence from an emerging market economy. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 12(3), 329–355.

- Saúde, S., Hermozilha, P., & Borrero, J. D. (2020). The influence of the local ecosystem on entrepreneurial intentions: A study with entrepreneurs and potential entrepreneurs of Beja (Portugal) and Huelva (Spain). Handbook of Research on Approaches to Alternative Entrepreneurship Opportunities. Chapter 006. IGI Global. doi:https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-1981-3

- Seo, M., & Creed, W. E. D. (2002). Institutional contradictions, praxis, and institutional change: A dialectical perspective. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 222–247.

- Sheriff, M., & Muffatto, M. (2015). The present state of entrepreneurship ecosystems in selected countries in Africa. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 6(1), 17–54.

- Shwetzer, C., Maritz, A., & Nguyen, Q. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: A holistic and dynamic approach. Journal of Industry-University Collaboration, 1(2), 79–95.

- Stam, E., & Van De Ven, A. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Business Economics, 56(2), 809–832.

- Sutter, C., Webb, J., Kistruck, G., Ketchen, D. J., & Ireland, R. D. (2017). Transitioning entrepreneurs from informal to formal markets. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(4), 420–442.

- Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective. Oxford, UK: Wiley Online Library.

- Thoughtwork. (2014). Frugal innovation in Africa. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtworks.com/insights/blog/frugal-innovation-africa-interview

- Trading Economics. (2020). Nigerian unemployment rate. Retrieved from https://tradingeconomics.com/nigeria/unemployment-rate

- United States Agency for International Development. (2016). Workforce development & youth employment in Nigeria (AID Contract # AID-OAA-I-15-00034/AID-OAA-TO-15-00011). Retrieved from https://www.youthpower.org/sites/default/files/Workforce%20Development%20and%20Youth%20Employment%20in%20Nigeria%20Desk%20Review%20Final%20Draft-Public%20Version%20(4).pdf

- Vershinina, N., Beta, W. K., & Murithi, W. (2018). How does national culture enable or constrain entrepreneurship? Exploring the role of Harambee in Kenya. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 25(4), 687–704.

- Welter, F., & Smallbone, D. (2011). Institutional perspectives on entrepreneurial behavior in challenging environments. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 107–125.

- Williams, N., & Vorley, T. (2015). The impact of institutional change on entrepreneurship in a crisis-hit economy: The case of Greece. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 27(1–2), 28–49.

- World Bank. (2013). Gender and transport. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved December 17, 2017, from http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2013/09/24/societies-dismantle-gender-discrimination-world-bank-group-president-jim-yong-kim

- World Bank. (2014). Latin American entrepreneurs: Many firms but little innovation. Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/LAC/LatinAmericanEntrepreneurs.pdf

- World Bank. (2015, October 27). Fact sheet: Doing business 2016 in Sub-Saharan Africa. Retrieved March 9, 2017, from http://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/brief/fact-sheet-doing-business-2016-in-sub-saharan-africa.

- World Bank. (2016, January). Informal enterprises in Kenya. Washington, DC, USA: Author.

- World Bank. (2020). World development report. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2020

- World Economic Forum. (2015). Why we need to rethink the informal economy. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/06/why-we-need-to-rethink-the-informal-economy/

- World Economic Forum. (2019). World Economic Forum (2019). Three things Nigeria must do to end extreme poverty. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/03/90-million-nigerians-live-in-extreme-poverty-here-are-3-ways-to-bring-them-out/#:~:text=About%2090%20million%20people%20%2D%20roughly,the%20bottom%20of%20the%20table