ABSTRACT

This article explores uses of peat bogs and associated plants and other resources by drawing on the published ethnobotanical and archeological literature pertaining to Indigenous groups that lived and continue to live on the Northwest Coast, the Interior/Plateau Regions, Northwestern Canada, the Central and Western Arctic, and the Far Northeast. We examine bog plants used as food and medicine, the relationships between people and bogs as documented through traditional ecological knowledge, and archeological evidence for bogs having been used as places to live and as sources of peat for use as building material. The aim is to bring attention to the fact that peat bogs were, and still are, very much a part of Indigenous cultural landscapes in North America. We suggest that greater attention should be paid to bogs and that a reassessment of their perceived marginality may be necessary to achieve a fuller understanding of past and present human–environment interactions in northern North America.

Introduction

Peat bogs (or peatlands) are a class of wetlands characterized by the buildup of dead organic material (peat) over time (C. W. Johnson Citation1985). They are commonly divided into fens (which are rheotrophic, or flow-fed), and bogs (ombrotrophic, or rain-fed), both of which are known to form through either terrestrialization (the gradual infilling of waterbodies with organic material and inorganic sediments) or paludification (the transformation of dry land into peatland; Charman Citation2002; P. D. Moore Citation2002; R. L. Anderson, Foster, and Motzkin Citation2003; M. Lavoie et al. Citation2005; Rydin and Jeglum Citation2013). Because peat bogs tend to be acidic and nutrient poor, only particular species can grow in them (C. W. Johnson Citation1985), including Sphagnum moss, the most typical contributor to bogs, as well as various species of berries, sedges, and grasses. Though scientists differentiate peatlands based on the characteristics they have (for example, fens and bogs), “bogs” is used here to refer to all peat-bearing wetlands with similar, albeit varied, vegetation communities.

Canada alone contains approximately 1,132,614 km3 of peatlands, and the United States has 197,841 km3. Together, they account for over 31 percent of the peatlands in the world (Xu et al. Citation2018). Yet, unlike in Northwestern Europe, where there has been a long-running archeological and paleoecological focus on bogs as loci of cultural activity (Godwin Citation1981; Gearey et al. Citation2010; Gearey and Fyfe Citation2016), in North America, peat bogs are often treated as marginal or dangerous spaces mostly devoid of human trespass. The bryophyte researchers Howard Crum and Planisek (Citation1988, 172) even stated that “in North America, at least in the glaciated North, [Indigenous peoples] in their hunting and fishing pursuits […] had little need to frequent peatlands. […]” More recently, archeologist George Nicholas (Citation1998, Citation2006) observed that archeologists often overlook bogs and other types of wetlands, sometimes omitting to record their presence close to sites. Aside from a few archeological studies focusing on bogs, wetlands, and other wet settings (e.g., Gleeson and Grosso Citation1976; Croes Citation1977; A. M. Davis, McAndrews, and Wallace Citation1988; Lyons et al. Citation2018, Citation2021; Bernick Citation2019), peat bogs have largely been overlooked in North American archeological literature. A number of recent studies, however, have revealed instances where peat bogs seem to have been used as some kind of living space or activity area (Renouf, Bell, and Teal Citation2000; Hartery and Rast Citation2001; Teal Citation2001; Hull Citation2002; Hartery Citation2007; Renouf, Bell, and Macpherson Citation2009; Ledger, Girdland-Flink, and Forbes Citation2019), suggesting they may have been actively sought by some Indigenous groups for purposes other than resource harvesting.

Ethnobotanists, in general, have paid greater attention to bogs than archeologists. This may be an incidental outcome of their effort to document broader systems of plant utilization by Indigenous peoples of North America, rather than as the result of a focus on bogs or species growing in them. Whereas in the past broad overviews of how people used plants were favored, analyses of specific plant species endemic to bogs and their use by certain groups have recently emerged (e.g., Gottesfeld and Vitt Citation1996). Karst and Turner’s (Citation2011) investigation of the use of bakeapple berry (Rubus chamaemorus) within a Métis community in Labrador is one of a handful of examples and serves well to illustrate the value of ethnobotanical research investigating the economic importance of specific bog plants.

The aim of this article is to contribute to a better understanding of the place of peat bogs in Indigenous lifeways and cultural landscapes—a conceptualization of landscapes that encompasses tangible (plants, animals, place, ecology, land and plant use) and intangible aspects (heritage, meaning) and how these change through time (Andrews and Buggey Citation2008; O’Rourke Citation2018). Although bogs are part of a wider category of wetlands, which are particularly susceptible to change in response to seasonal weather cycles and fluctuations in climates and hydrology, our focus here is on peat bogs specifically (regularly inundated peat-bearing sites), as we seek to illuminate the manifold ways Indigenous groups used and interacted with these spaces. In order to do so, we draw from ethnobotanical and archeological literature that demonstrates the connection that many Indigenous peoples of North America had (and continue to have) with peat bogs, from which they have acquired plants for use as food and medicine and harvested sods as construction materials.

Indigenous knowledge of bogs and their associated resources is gained through extensive, long-term observation of species or areas on the landscape and transmitted intergenerationally through oral tradition or otherwise passed among individuals who collectively use a resource. This is commonly understood as part of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) or landscape ethnoecology (the culturally situated practices and understandings of landscape amongst a people) in academic literature (Berkes, Colding, and Folke Citation2000; Huntington Citation2000; L. M. Johnson Citation2012). However, it is important to stress that Indigenous ontologies and epistemologies usually incorporate this into broader knowledge systems, which can encompass the totality of past, present, and future worldviews, knowledge and value systems, and ways of acting (a good example is Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit; Wenzel Citation2004; Tester and Irniq Citation2008; Laugrand and Oosten Citation2010; Boulanger-Lapointe et al. Citation2019; Pedersen et al. Citation2020). Accordingly, a number of voices have criticized and cautioned against decontextualized and appropriative uses of TEK (Nadasdy Citation1999; Furgal and Laing Citation2012; Kim, Asghar, and Jordan Citation2017; Wyndham Citation2017).

Both of us authors are white settlers living and working at an institution located on the ancestral homelands of the Beothuk and Mi’kmaq. Despite our efforts to seek and include relevant Indigenous scholarship, it must be clearly stated that our focus on published studies means that our article is inherently biased toward Indigenous knowledges and practices as understood and filtered through a settler-scholar lens. Because we are sympathetic to the ongoing struggle of Indigenous peoples toward self-determination and the decolonization of our institutions (sensu McAlvay et al. Citation2021), future endeavors to understand the richness, complexity, and significance of Indigenous relationships with peat bogs should be led by Indigenous individuals and communities. In fact, we our hope this article will help raise awareness and generate interest toward archeological and ethnobotanical research targeting peat bogs, particularly among Indigenous students.

Methodology and scope

Because our interest in peat bogs as loci of cultural activity was the starting point for this article, the sources upon which it is based were largely found using keyword searches in online library databases. These included terms and concepts such as “bog plants,” “peatlands,” and “cultural landscapes” but also Latin names of specific bog plants (e.g., “Rubus chamaemorus,” “Vaccinium oxycoccos”). As sources were found, relevant references were pulled from their bibliographies in a process known as “backward snowballing” (van Wee and Banister Citation2016, 284), which led to new avenues of enquiry. Our focus on peat bogs and the methodology followed to retrieve sources mean that the Indigenous groups that appear in this article were selected due to the availability of literature pertaining to their uses of bogs and the resources they afford. This means our article is by no means exhaustive, because it was limited to available published literature, and there were, and likely still are, many more bog plants and other resources used by Indigenous peoples that are not documented in this manner.

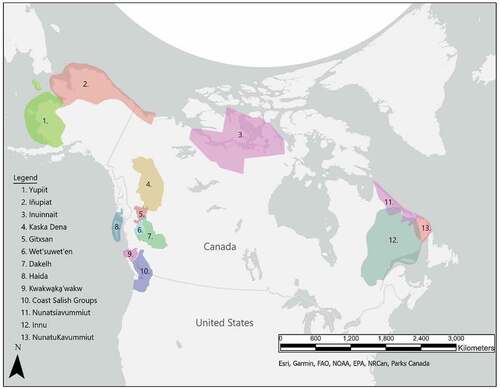

The Indigenous groups discussed in this article inhabited and continue to occupy the coastline and adjacent hinterlands of the northern regions of North America. However, some groups from further inland are also included, such as the Wet’suwet’en and other Dakelh (Carrier) groups within the neighboring Interior/Plateau Regions of British Columbia, Canada. On the Northwest Coast, this article encompasses the Gitxsan and Coast Salish, which include the Katzie and other mainland groups and those on Vancouver Island, in particular the W̱SÁNEĆ (Saanich), as well as the Kwakw̱ḵʼwakw (Kwakiutl). The Haida of the Haida Gwaii archipelago and the Kaigani Haida (whose homeland includes the southern end of Prince of Wales Island and the adjacent archipelago in Alaska, USA) are also included, as are the Yupiit (including the Nunivaarmiut of Nunivak Island), the Iñupiat, and various groups in the western part of the state of Alaska (in the Western Arctic). In the Canadian Arctic, the Kiluhikturmiut Inuinnait of Kugluktuk, Nunavut, and the generalized use of berries among the Inuit are dealt with. Resource use among the Kaska Dena of northwestern Canada is discussed as well. This article includes plant use by the Labrador Inuit (Nunatsiavummiut) and Labrador Métis (NunatuKavummiut) and the specific use of the purple pitcher plant by the Innu (Montagnais) of Lac Saint-Jean, Quebec () on the far Northeast coast.

Figure 1. Overview map of North America showing the traditional territories currently claimed by Indigenous groups mentioned in the text as known to be using, or having used, bog plants and resources. Territory information obtained from https://native-land.ca/ (Native Land Digital Citation2021). Map prepared by James Williamson.

By bringing together ethnobotanical, archeological, and related literature, this article presents a multipronged approach to understanding Indigenous uses of bog plants in northern North America. Information obtained through fieldwork by ethnobotanists in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is thus here integrated with studies of archeological remains that add a greater time depth, allowing us to begin exploring how understandings and uses of peat bogs changed over time and space.

Over the following pages, we present an overview of the use of particular bog species by the Indigenous groups listed above. We then look at the archeological evidence for sod and peat harvesting, as well as peat bogs that were occupied as living spaces and/or activity areas. Then, in an attempt to better demonstrate how these varied types of human–environment interactions are interconnected and encoded as part of rich, culturally specific systems of knowledge, we discuss in more details two specific examples pertaining to the Kaska Dena of northwestern Canada and the Alaskan Yupiit and Iñupiat.

Uses of bog plants

The following paragraphs describe the most important and/or commonly used bog plant species as identified through our literature search, which includes different berries and mosses as well as various other plants ().

Table 1. List of bog plant species mentioned in the text as utilized by Indigenous peoples

Berries

Indigenous groups throughout northern North America harvested berries. The presence of certain species within bogs would have been an important draw to these areas. Bog cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos) is a member of the heath family (Ericaceae) native to open, acidic bog and fen environments, which produces a small red edible fruit (R. B. Davis Citation2016). On the Northwest Coast, the Kaigani Haidi of southeast Alaska collected bog cranberry when the fruit was firm. These were stored in grease and eaten later, sometimes mixed with sugar or with salal (Gaultheria shallon) berries (Norton Citation1981). The Kwakw̱ḵʼwakw in British Columbia made use of bog cranberry, picking them in the fall and either consuming them directly or steaming them (N. C. Turner and Bell Citation1973). Near Nain in Labrador, bog cranberries (locally called marshberries) were also noted as being harvested by the Inuit in small quantities (Boulanger-Lapointe et al. Citation2019). The Napaskiak Yup’ik would also gather bog cranberries opportunistically during their salmonberry picking trips (Oswalt Citation1957). Among the Katzie (Coast Salish), cranberry bogs were owned, and outsiders had to ask permission to harvest cranberries. However, permission was never refused, and there was no tribute required for the cranberries picked from the bogs, which allowed the Katzie to act as gracious hosts (Suttles Citation1955).

As a member of the Ericaceae family, bog cranberry reappears relatively quickly after a fire because it can regenerate from rhizomes below the bog surface (Damman Citation1978). Peatlands often experience regular naturally generated burns at varying intervals (Kuhry Citation1994; Zoltai et al. Citation1998); however, Indigenous peoples also set fire to peat bogs to stimulate berry growth (Crum and Planisek Citation1988; C. Lavoie and Pellerin Citation2007; K. Anderson Citation2009) and manage other resources (N. J. Turner Citation2010). Fire was specifically used on cranberry bogs on the Northwest Coast to increase berry yield and manage tree growth (K. Anderson Citation2009). Biggs (Citation1976) suggested that the Coast Salish set fire to the Burns Bog in the Fraser Delta, British Columbia, to increase the abundance of berries, which likely included bog cranberries, because these were recorded as being present there (Giblett Citation2014). Fire was likely used elsewhere to manage blueberries as well, because they will increase in yield several years after a light to moderate burn (C. Lavoie and Pellerin Citation2007; Nelson, Zavaleta, and Chapin Citation2008).

Bog blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum) occurs predominantly in Sphagnum bogs. The Coast Salish on Vancouver Island would gather bog blueberries and either dry them or eat them raw (N. C. Turner and Bell Citation1971). J. P. Anderson (Citation1939) noted that the Inuit in western Alaska made extensive use of bog blueberry. This was especially true where R. chamaemorus (locally referred to as salmonberries) was not plentiful (Oswalt Citation1957).

R. chamaemorus (variably referred to as bakeapple, salmonberry, mars apple, malt berry, and cloudberry) is a member of the Rosaceae family with a circumpolar and boreal distribution, although it also occurs further south (Thiem Citation2003). It is found predominantly in bogs (Karst, Antos, and Allen Citation2008). The Haida in British Columbia and Alaska were extremely fond of R. chamaemorus and would eat them in large quantities (N. J. Turner Citation2004). According to Oswalt (Citation1957), R. chamaemorus was the most important plant food consumed by the Napaskiak Yup’ik in Alaska. Every fall, families would pick enough of these berries to fill two or three wooden barrels approximately 50 liquid gallons in size. The berries would be consumed over the winter as a principal component of agu’tukFootnote1 (Oswalt Citation1957), which was colloquially referred to as “Eskimo ice cream” (Zutter Citation2009). This dish was made from berries, seal oil, lard or tallow, sugar, boiled fish, and various greens. Bog blueberries would sometimes be mixed into agu’tuk as well. However, Oswalt (Citation1957) observed that they were most often eaten raw with milk and sugar.

Throughout Inuit Nunangat, which comprises the Inuit homeland in Canada, Boulanger-Lapointe et al. (Citation2019) identified bog blueberry and bakeapple (or cloudberries) as commonly picked species, both of which occur predominantly in bogs. For instance, the Kiluhikturmiut Inuinnait picked bakeapples and bog blueberries, which were eaten raw mixed with fat (J. D. Davis and Banack Citation2012). Analysis of a human coprolite sample from the eighteenth century Inuit Uivak 1 Site (HjCl-11), near Okak in Labrador, revealed high concentrations of seeds from blueberries and crowberries (Empetrum nigrum) as well as black globules, which were identified as probable animal fat residues. This was interpreted as evidence of the mixing of fat with berries (Zutter Citation2009). In general, berries were an important secondary food source at the site, as demonstrated by the high densities of both blueberry and crowberry seeds in the house and midden (Kaplan and Woollett Citation2000).

Karst and Turner (Citation2011) investigated the current use of bakeapple in the southern Labrador Métis community of Charlottetown by conducting interviews as well as participant observation. They found that those within the community had a detailed local ecological knowledge concerning where the best berry picking places were, habitats associated with densities and sizes of berries, and an understanding of different stages of berry development. Importantly, bakeapple picking also functioned as a key social activity, albeit one that was in danger of being lost given the diminishing interest of younger generations (Karst and Turner Citation2011). Given the amount of information that could be gathered on bakeapple within a single community, it would certainly be beneficial to look at the use of individual bog plant species in other communities as well.

Sphagnum

Sphagnum moss, otherwise known as peat moss due to its recognized role in forming peat bogs, is a genus of moss composed of around 300 species (Michaelis Citation2019). Indigenous North Americans widely used Sphagnum for various purposes, many of which cut across cultures but some of which are unique. Long recognized for its absorbency, Sphagnum moss has been employed as a diaper material (Thieret Citation1956), as a feminine hygiene product (Kimmerer Citation2003), and for bandages (N. J. Turner Citation1998). J. D. Davis and Banack (Citation2012) recorded that among the Kiluhikturmiut Inuinnait of Nunavut, Canada, Sphagnum was used for menstrual pads, diapers, and bandages. On Nunivak Island, Alaska, the Nunivaarmiut (Yup’ik) made diapers by placing dried Sphagnum in a scraped and softened seal skin (Lantis Citation1946). The Wet’suwest’en and Gitxsan peoples of British Columbia also made use of Sphagnum for diapers, avoiding red variants because they believed they would cause skin irritation. An aversion to red Sphagnum moss was also documented among neighboring groups belonging to the Dakelh (Carrier) in British Columbia (Harris Citation2008).

There were a variety of medicinal uses for Sphagnum moss as well. Indigenous Alaskans made a salve for application on cuts by mixing Sphagnum with animal tallow or grease (Thieret Citation1956). The Kwakw̱ḵʼwakw of southern British Columbia believed that if Sphagnum was gathered from four different locations, wiped on the body of a person with a fever and then each piece returned to its original location, the fevered person would reduce in temperature and become cool like the moss (Boas Citation1966; N. C. Turner and Bell Citation1973).

Sphagnum was utilized in other diverse and imaginative ways. The Kiluhikturmiut Inuinnait used Sphagnum as insulation and as a coating on sled runners (J. D. Davis and Banack Citation2012). The Napaskiak Yup’ik were also known to chink their log houses with Sphagnum (Oswalt Citation1957), and the moss may also have been employed for soapstone lamp wicks (Llano Citation1956). N. C. Turner and Bell (Citation1973) referred to a belief among young Kwakw̱ḵʼwakw that wiping their faces with Sphagnum would lighten their complexion.

Other plants

In addition to Sphagnum, many different plants acquired from bogs were used for myriad purposes. Common sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) is an insectivorous plant native to bogs (R. B. Davis Citation2016), which was utilized by the Kwakw̱ḵʼwakw for removing warts, corns, and bunions. Kwakw̱ḵʼwakw men also used it as a love charm, whereby it was mixed with salamander toes and another plant (either Habenaria saccata or Hypopites monotropa; N. C. Turner and Bell Citation1973). The Coast Salish of British Columbia were also likely familiar with sundew, because they would have encountered it when venturing to bogs to collect other plants, such as Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum), which on Vancouver Island only grows in Sphagnum bogs and was made into a tea by the W̱SÁNEĆ and likely other Coast Salish groups as well (N. C. Turner and Bell Citation1971).

Cotton grass (Eriophorum spp.) is a genus of the sedge family consisting of several species that are tolerant of acidic bog conditions and known to grow there (R. B. Davis Citation2016). It is so named for the cotton-like tufts that grow on the seed head of the plant. The use of cotton grass for making kudlik (soapstone lamp) wicks and bandages has been documented around the circumpolar north (Lazarus and Aullas Citation1992; Small and Cayouette Citation2016), including among the Labrador Inuit (Zutter Citation2009). Pigford and Zutter (Citation2014) recovered cotton grass phytoliths from residues on soapstone fragments at the eighteenth-century Labrador Inuit site of Dog Island–Oakes Bay I (HeCg-08). According to Zutter (Citation2009), Labrador Inuit also used sedges (Carex spp.) and rushes (Juncus spp.), which grow in bog and wetland environments, for making floor coverings and woven mats.

Lysichiton americanus, otherwise known as skunk cabbage due to its pungent smell, is a rhizomatous bog plant (French and Tomlinson Citation1981) known to grow in fens (Lacourse, Adeleye, and Stewart Citation2019) and peatland margins on the west coast of North America (Mackenzie and Moran [Citation2004]; also see Symplocarpus foetidus for an eastern variant of skunk cabbage). The Kaigani Haida were known to make use of this resource, using the leaves to store food items in, as well as in cookery, whereby meat or fish would be wrapped in the leaves and then baked over hot coals. Despite their strong smell, skunk cabbage leaves will not impart a flavor in food during cooking (Norton Citation1981).

The purple pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea) is a carnivorous perennial herb in the pitcher plant family (R. B. Davis Citation2016). It is endemic to bogs, poor fens (a type of fen that is nutrient-poor, acidic, and partly fed with groundwater), and other acidic environments. It can be found along the Atlantic coast as far north as Labrador and as far west in Canada as the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains (C. W. Johnson Citation1985; Ellison et al. Citation2004). The Mohegan folklorist Gladys Tantaquidgeon (Citation1932, 266) noted that it was called alk tsotaco’ or “toad legging” by the Lac Saint–Jean Innu. The leaves of the plant were boiled and the resulting liquid used to treat sores and children’s rashes. The split leaves of the plant would also be placed over the affected area to treat the same ailments. The plant could also be used to relieve smallpox (Tantaquidgeon Citation1932).

Peat and sod as construction materials

Throughout arctic and parts of subarctic North America, the Inuit, Ancestral Inuit, and pre-Inuit built semi-subterranean houses using blocks of earth and surface vegetation (variably referred to as “sod” or “turf”), which were usually harvested from bogs or other types of wetlands. These were placed onto a framework constructed from either whalebone or wood, depending on the availability of either resource (Park Citation1988; Arnold and Hart Citation1992; Renouf Citation2005). This method of construction was used in many areas well after the time of European contact (Auger Citation1993; Molly and Reinhardt Citation2003; Beaudoin, Josephs, and Rankin Citation2010; Knudson and Frink Citation2010). Sometimes, peat would also be utilized in the construction of these dwellings, and there is some evidence for its purposeful selection as building material. For example, in the course of their research on the Qijurittuq Site (IbGk-3) on Drayton Island in Quebec (where Ancestral Inuit built 13 semi-subterranean houses using peat along with other materials in the construction of the walls and roofs), Inuit elders were interviewed about traditional construction techniques and indicated that peat was employed, at least in part, because it provided good protection from the wind and that peat was used when there was no snow (Lemieux, Bhiry, and Desrosiers Citation2011). According to Barbel et al. (Citation2019), peat was commonly used by the Ancestral Inuit to build the peripheral walls of houses because it provided good insulation from the cold, and it was shown to have been used at the Ancestral Inuit sites of Oakes Bay 1 (HeCg‐08) and Koliktalik 6 (HdCg‐23) in Labrador (Roy, Bhiry, and Woollett Citation2012). Fitzhugh (Citation2019) noted that on the Quebec Lower North Shore, the Inuit utilized peat along with sod, skins, and wood for constructing houses. The mixing of peat and other materials would seem to indicate that it was employed purposefully to a particular end. Habitation sites, many of which were previously occupied by pre-Inuit groups, may also have been selected by the Ancestral Inuit, at least in part, for their proximity to peat deposits (Barbel et al. Citation2019). This is evident at Diana Bay, Quebec, where there are over 100 habitation sites situated adjacent to peatlands from which material could be conveniently obtained for house construction (Bhiry, Marguerie, and Lofthouse Citation2016).

Like many Indigenous communities living in subarctic and arctic regions, European peoples who lived in similar settings developed specific traditions and practices to harvest and use peat and sod (or turf, as it is most commonly known in a European context) as building materials and for other purposes (Forbes, Dussault, and Bain Citation2014). In general, Indigenous uses of peat and sods in constructing houses are not as well documented (at least in the published literature) as that of the Norse and later Europeans who lived in the North Atlantic (e.g., Ólafsson and Ágústsson Citation2000; Steinberg Citation2004; Milek Citation2006; van Hoof and van Dijken Citation2008; Stefánsson Citation2019) and therefore there may be some instances where uses of these materials have been overlooked or remain poorly understood. More research into semi-subterranean house construction, turf/sod harvesting, and associated practices by Inuit, Ancestral Inuit, and other Indigenous groups could help to shed light on the use of peatland resources.

Peat deposits as occupation surfaces

Archeological work on the island of Newfoundland has revealed several instances of the surface of peat bogs being used as living spaces and/or activity areas by Indigenous groups during a time period known as the Recent Period (ca. 0 to 1500 CE, Hartery Citation2007). Archeological evidence for this occurs where occupation layers, formed by the accumulation of materials resulting from human occupation or activities having taken place, are identified in bogs. One such occupation surface was identified at the Gould Site (EeBi-42) at Port au Choix by Renouf, Bell, and Macpherson (Citation2009), where it is apparent that during the site’s Recent Period occupation, people were actually living on top of the peat deposit that covered the site at the time (Renouf, Bell, and Teal Citation2000; Teal Citation2001; Renouf, Bell, and Macpherson Citation2009). Excavations uncovered charcoal, fire-cracked rock, and cultural materials all contained within a thick layer of peat, in addition to several pit features that were identified that appear to have been dug into the peat layer underlying the occupation surface. Similarly, at the Peat Garden Site (EgBf-6) near Bird Cove, excavators uncovered the remains of ten hearth features sunk into a layer of peat, which was the living surface during the Recent Period (Cow Head Complex) occupation of the site (Hartery and Rast Citation2001; Hartery Citation2007). One of the hearths was even lined with clay, which may have been used to create a barrier with the underlying water-saturated peat. A total of 551 artifacts relating to the Cow Head Complex were found at the site, most of them directly associated with the hearth features there (Hartery Citation2007). Recently, a previously undocumented cultural layer was also uncovered in a Sphagnum peat bog at L’Anse aux Meadows (EjAv-01) (Ledger, Girdland-Flink, and Forbes Citation2019). In this case, the layer consists of a probable trampled surface with patches of charcoal, charred plant remains and wood debris inclusions. No artifacts have been recovered in association with this layer, and further investigations are underway to hopefully reveal what the surface had been used for.

The examples mentioned above suggest that Indigenous peoples made use of peat bogs and other peat-bearing wetlands, where they seem to have performed a variety of tasks and, in some instances, camped or lived there. This suggests that for these groups, the bog surface may have been just as viable a living surface as any other, which directly challenges the perception of bogs as uninviting places to dwell.

Peat bogs as part of broader knowledge systems

From the examples above, it is evident that within northern North America, many Indigenous groups had detailed knowledge of bogs from an early time, something that has carried on in many cases until the present day. We have provided a detailed account of bog plants and their uses as documented in ethnobotanical literature and also briefly discussed the use of peat and sod in construction, as well as archeological evidence for peat bogs having been spaces for cultural activity. Here, in an attempt to stress how interactions between Indigenous peoples and peat bogs should be seen as part of rich and expansive worldviews and knowledge systems, we discuss in more detail examples pertaining to the Kaska Dena of northwestern Canada and the Yupiit and Iñupiat of Alaska.

Leslie Johnson (Citation2012) noted that the Kaska Dena refer to moss-dominated bog as tūtsel, a term that also encompasses sedge wetlands and translates to “swamp” in English. For the Kaska, tūtsel is a site of great cultural value on the landscape and has even been described as a “‘grocery store’“ (L. M. Johnson and Hunn Citation2010, 287) because so much food and medicine can be acquired there (L. M. Johnson Citation2012). Within moss-dominated tūtsel (bog), the Kaska access plant resources such as tamarack (Larix laricina), the bark of which is used as a medicine, as well as Labrador tea, which is also used medicinally and as a beverage ingredient. Blueberries and cranberries are obtained from tūtsel, and Sphagnum, the traditional Kaska diaper material, was also gathered there in the past (L. M. Johnson Citation2012). Unlike the wetter sedge-dominated wetlands that require boats to access, moss-dominated bogs can be entered on foot during part of the year (L. M. Johnson Citation2012). Far from being marginal, tūtsel generally and bogs specifically are appreciated by the Kaska Dena as valuable locations on the land due to the wealth of resources there. This appreciation is encoded within Kaska TEK and governed through rules called á’ī, which are part taboo, part prescriptive rule, based on respect, and stipulate how Kaska should act toward plants, animals, and the Earth itself (L. M. Johnson Citation2012).

Among Indigenous Alaskans, understanding of bogs extends beyond the margins of the bog environment itself and includes other organisms. During his fieldwork among the Napaskiak Yupiit in the 1950s, Oswalt (Citation1957) recorded that bakeapple picking excursions onto the tundra would necessitate traveling a fair distance, take three weeks, and involve the entire family—a significant investment in time and effort. It was understood that when the false chamomile (Matricaria suaveolens) bloomed in the village, it was time to head out onto the land to harvest bakeapples (Oswalt Citation1957). Another example comes from the practice of harvesting from the nests of field mice, taking stores of plants, or “mouse food,” which the mice had cached away there for use as winter foodstuffs (J. P. Anderson Citation1939; Ager and Ager Citation1980; L. J. Crawford Citation2012). According to Jernigan (Citation2014), the nests of voles were also gathered from. In some places, the removed material was replaced with fish so that the resident mouse (or vole) would survive through the winter and replenish the same nest with more material the following year (J. P. Anderson Citation1939; Jernigan Citation2014). Many of the plants that constitute “mouse food” are bog plants and often quite challenging to gather manually, which more or less necessitated this method of harvest. J. P. Anderson (Citation1939) noted that in western Alaska, the bases of sedges in the genus Carex, which grow in bogs and wetlands, were gathered from mouse nests in this manner. Among the Iñupiat, it was common practice to gather pitniq—the bottom portion of cotton grass stems—from the nests of voles and mice (Jones Citation2010). The rodents dig up this component of the plant and trim off the small hairs that cover it (a task that is tedious for humans to do) and cache it within their nests. Once harvested from the nests, the Iñupiat would store this material in oil for later use as food. The Yukon–Kuskokwin-region Yupiit still gather utngungssarat, the tear-shaped inner stem bases of certain Carex species, from voles’ nests in the fall. These are cooked and eaten as food (Jernigan Citation2014). Utngungssarat are understood to be a staple food of the vole, like the ringed seal is a staple food of the Yupiit (Jernigan Citation2014), an observation that demonstrates a depth of understanding regarding their abundance in vole nests and their importance to the species. This Indigenous Alaskan understanding of the interrelation between the blooming of false chamomile and the ripeness of bakeapples, just like the practice of gathering “mouse food,” developed through correlation and phenological knowledge of the greater environment and was utilized to save time in scheduling group resource gathering activities and to reduce energy expenditure.

Discussion

This article has sought to demonstrate that far from being marginal spaces, peat bogs should be considered as valuable parts of Indigenous cultural landscapes in northern North America and as actively utilized places. This is true both in the past as well as in the present. Within peatlands, a wealth of plants for use both as food and as medicine, as well as construction material in the form of peat and sod, are on offer—all of which have been utilized accordingly. Berries, in particular, were gathered from bogs and still are by many Indigenous groups (Boulanger-Lapointe et al. Citation2019; Herman-Mercer et al. Citation2020). Knowledge of these environments and the resources available there continue to be held in trust within the cultural systems of groups as components of cultural landscapes, knowledge systems, and worldviews.

The time depth of Indigenous relationships with bogs in northern North America is evidenced by use of bogs as habitation sites in Newfoundland, the construction of semi-subterranean Inuit houses, and the gathering of certain bog plants as food and medicine, as shown by phytolith analysis (Pigford and Zutter Citation2014). Despite this, it is not rare for archeologists to overlook bogs, sometimes dismissing them as potential site locations (Nicholas Citation2001). Part of the issue may lie in the fact that bogs are difficult to traverse on foot, and if one should have the audacity to do so, one is quite liable to lose their shoes (Kimmerer Citation2003). They also have a tendency of obscuring archeological remains under a homogenizing layer of peat, which obfuscates and conceals features (McLean Citation2003). Existing geophysical prospecting technologies, in particular, ground-penetrating radar, are often ill-suited to wet environments (Conyers Citation2004; Schultz Citation2007; Fiedler et al. Citation2009) and, therefore, prospection capabilities are limited. These limitations have been overcome in other parts of the world through approaches combining geophysical survey with scientific (e.g., elements analysis) and traditional (e.g., test-pitting) methods. For instance, such an approach allowed the identification of mid-Holocene fishing structures at a peat-bearing site at Haapajärvi in Finland (Koivisto, Latvakoski, and Perttola Citation2018) and successfully locating the Sweet Track, a Neolithic trackway in a peat bog near Somerset in the United Kingdom (Armstrong, Cheetham, and Darvill Citation2019). In North America, however, the true number of sites in or under bogs may not be appreciated, due to the lack of a peat cutting industry, unlike in mainland Europe and the British Isles, where large-scale peat cutting has inadvertently unearthed many ancient remains in peatlands (Godwin Citation1981; Raftery Citation1995; van der Sanden Citation2013; C. Moore Citation2021). The persistent but transient usage of bogs may have left ephemeral, if any, cultural remains as well in many areas, particularly in the vast bogs of the subarctic boreal forest (McGhee Citation1996; R. M. Crawford Citation2013). However, it is apparent that sites are existent inland, away from the shorelines of rivers and lakes, where archeologists usually limit their searches in the boreal forest (Hamilton Citation2000; Hyslop and Colson Citation2017).

North American archeologists can do more methodologically to understand how, and which, bog species were utilized in the past. In general, paleoethnobotanical/archaeobotanical forms of analysis and the experts who conduct them need to be incorporated into archeological research designs (Lepofsky, Moss, and Lyons Citation2001), ideally from the beginning of projects, with the goal of doing problem-oriented research. To this end, phytolith analysis (Rashid et al. Citation2019; Cabanes Citation2020), analysis of macrobotanical remains from peat-bearing sites (Mauquoy, Hughes, and van Geel Citation2010; Lamentowicz et al. Citation2019), and novel methods such as pollen washes from lithic artifacts (Miras et al. Citation2020) can be employed. Through this, a better appreciation of the types of bog species gathered and their use in Indigenous diet and medicine and for construction purposes could be derived.

Researchers within allied disciplines (such as paleoecology, ethnoecology, anthropology, and geography) should also pay greater attention to peat bogs in order to understand their current value and importance today and as components of broader cultural landscapes. For example, a small but growing body of paleoecological research specifically targeting peat bogs within the immediate vicinity of archeological sites has now been deployed across the North Atlantic Islands (Ledger, Edwards, and Schofield Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Citation2017) and recently at the Yup’ik site Nunalleq in southwestern Alaska (Ledger Citation2018; Ledger and Forbes Citation2019; Forbes et al. Citation2020). This approach has been proven highly successful in generating high-resolution chronologies and paleoecological (plant and insect fossil) data sets, where the ecological impacts of human activity—including that of Indigenous foragers—can readily be observed and interpreted.

Given the long history of research focusing on peatlands in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and mainland Europe, it would be useful to see greater knowledge transfer between researchers situated in these locations and in North America. The transfer of knowledge should ideally cross disciplinary boundaries as well, to allow researchers who study peat bogs within the humanities or social sciences (e.g., Gladwin Citation2016), for example, to share insights and knowledge with those involved in understanding the ecology of peat bogs and peatland restoration (e.g., Chimner et al. Citation2017).

We believe that bogs are a fertile avenue of enquiry that can and should be explored further by researchers interested in the past and present lifeways of Indigenous groups living in coastal, northern, arctic, and subarctic environments. In the future, it would be beneficial to see more ethnobotanical studies on the uses of particular bog plants. The study by Karst and Turner (Citation2011) on the use of bakeapple berry within a Métis (NunatuKavummuit) community in Labrador provides an excellent template for how such research projects can be accomplished. Studying current uses of bog plants within Indigenous communities may provide clues regarding how the same plants were used in the past, while also allowing an exploration of how utilization of these resources changed, or was maintained, through time. Moving forward, more collaborative work should be conducted with, by, and for Indigenous communities and knowledge holders, because it holds the key to both deeper understandings about the environment, plant, and landscape use and the equitable practice of research (Nicholas et al. Citation2011; Lepofsky and Lertzman Citation2018). Furthermore, research that is Indigenous-led and fully collaborative breaks down Western knowledge frameworks and paves the way for decolonization, both within ethnobotany and in archeology (Douglass et al. Citation2019; Joseph Citation2021). Collaborative plant-focused research is already occurring in some parts of northern North America (e.g., Oberndorfer et al. Citation2017, Citation2020), and we hope that more research of this kind, and projects led by Indigenous individuals and communities, will take place in the near future.

Conclusions

Our focus on peat bogs effectively demonstrates how culturally diverse and geographically dispersed Indigenous groups, situated across the northern outer fringes of the continent, similarly used peat bogs for the gathering of resources and viewed them as important components of their lived landscapes. If archeologists and ethnobotanists were to devote more effort to understanding the use and significance of peat bogs by Indigenous groups, it is likely that perception of bogs would eventually shift from marginal places to valuable and important components of cultural landscapes.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Williamson for preparing the map in the text, Meghann Livingston for comments on an early draft of the article, and students who took part in the Advances in Environmental Archaeology (ARCH 6682) graduate seminar (winter 2020), where the initial draft and ideas for this article originated. We are deeply appreciative of detailed, constructive criticisms provided by three anonymous reviewers, which helped us improve the text. We also thank Native Land Digital for making the Indigenous territory information, which was the basis for the map in this article, freely and publicly available on their website Native-Land.ca. All errors and omissions are none but our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Indigenous language terms are in bold italics throughout the text.

References

- Ager, T. A., and L. P. Ager. 1980. Ethnobotany of the Eskimos of Nelson Island, Alaska. Arctic Anthropology 17 (1):26–48.

- Anderson, J. P. 1939. Plants used by the Eskimo of the northern Bering Sea and arctic regions of Alaska. American Journal of Botany 26 (9):714–16. doi:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1939.tb09343.x.

- Anderson, K. 2009. The Ozette prairies of Olympic National Park: Their former Indigenous uses and management. Final Report to Olympic National Park Port Angeles, Washington Winter 2009. National Park Service, Pacific West Region.

- Anderson, R. L., D. R. Foster, and G. Motzkin. 2003. Integrating lateral expansion into models of peatland development in temperate New England. Journal of Ecology 91 (1):68–76. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00740.x.

- Andrews, T. D., and S. Buggey. 2008. Authenticity in Aboriginal cultural landscapes. APT Bulletin 39 (2/3):63–71.

- Armstrong, K., P. Cheetham, and T. Darvill. 2019. Tales from the outer limits: Archaeological geophysical prospection in lowland peat environments in the British Isles. Archaeological Prospection 26 (2):91–101. doi:10.1002/arp.1725.

- Arnold, C. D., and E. J. Hart. 1992. The Mackenzie Inuit winter house. Arctic 45 (2):199–200. doi:10.14430/arctic1393.

- Auger, R. 1993. Late-18th- and early-19th-century Inuit and Europeans in Southern Labrador. Arctic 46 (1):27–34. doi:10.14430/arctic1318.

- Barbel, H., N. Bhiry, D. Todisco, P. Desrosiers, and D. Marguerie. 2019. Paaliup Qarmangit 1 site geoarchaeology: Taphonomy of a Thule-Inuit semi-subterranean dwelling in a periglacial context in northeastern Hudson Bay. Geoarchaeology 34 (6):809–30. doi:10.1002/gea.21753.

- Beaudoin, M. A., R. L. Josephs, and L. K. Rankin. 2010. Attributing cultural affiliation to sod structures in Labrador: A Labrador Métis example from North River. Canadian Journal of Archaeology/Journal Canadien d’Archéologie 34 (2):148–73.

- Berkes, F., J. Colding, and C. Folke. 2000. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological Applications 10 (5):1251–62. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1251:ROTEKA]2.0.CO;2.

- Bernick, K. N., Ed. 2019. Waterlogged: Examples and procedures for northwest coast archaeologists. Pullman: Washington State University Press.

- Bhiry, N., D. Marguerie, and S. Lofthouse. 2016. Paleoenvironmental reconstruction and timeline of a Dorset-Thule settlement at Quaqtaq (Nunavik, Canada). Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 48 (2):293–313. doi:10.1657/AAAR0015-045.

- Biggs, W. G. 1976. An ecological and land use study of Burns bog, Delta, British Columbia. MSc thesis, University of British Columbia.

- Boas, F. 1966. Kwakiutl ethnology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Boulanger-Lapointe, N., J. Gérin-Lajoie, L. S. Collier, S. Desrosiers, C. Spiech, G. H. R. Henry, L. Hermanutz, E. Lévesque, and A. Cuerrier. 2019. Berry plants and berry picking in Inuit Nunangat: Traditions in a changing socio-ecological landscape. Human Ecology 47 (1):81–93. doi:10.1007/s10745-018-0044-5.

- Cabanes, D. 2020. Phytolith analysis in paleoecology and archaeology. In Handbook for the analysis of micro-particles in archaeological samples, ed. A. G. Henry, 255–88. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Charman, D. 2002. Peatlands and environmental change. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Chimner, R. A., D. J. Cooper, F. C. Wurster, and L. Rochefort. 2017. An overview of peatland restoration in North America: Where are we after 25 years?. Restoration Ecology 25 (2):283–92. doi:10.1111/rec.12434.

- Conyers, L. B. 2004. Moisture and soil differences as related to the spatial accuracy of GPR amplitude maps at two archaeological test sites. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Grounds Penetrating Radar, 2004. GPR 2004: 21 - 24 June 2004, ed. E. Slob, 435–38. Delft: Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands. University of Technology.

- Crawford, L. J. 2012. Thule plant and driftwood use at Cape Espenberg, Alaska. MA thesis, University of Alaska.

- Crawford, R. M. 2013. Tundra-taiga biology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Croes, D. R. 1977. Basketry from the Ozette Village archaeological site: a technological, functional, and comparative study. PhD thesis, Washington State University.

- Crum, H., and S. Planisek. 1988. A focus on peatlands and peat mosses. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Damman, A. W. H. 1978. Geographical changes in the vegetation pattern of raised bogs in the Bay of Fundy region of Maine and New Brunswick. Pp 91–105 in E. van der Maarel and M. J. Werger (eds.), Plant Species and Plant Communities: Proceedings of the International Symposium held at Nijmegen, November 11–12, 1976 in honour of Professor Dr. Victor Westhoff on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Davis, R. B. 2016. Bogs & Fens: A guide to the peatland plants of the Northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. Lebanon: University Press of New England.

- Davis, J. D., and S. A. Banack. 2012. Ethnobotany of the Kiluhikturmiut Inuinnait of Kugluktuk, Nunavut, Canada. Ethnobiology Letters 3:78–90. doi:10.14237/ebl.3.2012.31.

- Davis, A. M., J. H. McAndrews, and B. L. Wallace. 1988. Paleoenvironment and the archaeological record at the L’Anse Aux Meadows Site, Newfoundland. Geoarchaeology 3 (1):53–64. doi:10.1002/gea.3340030104.

- Douglass, K., E. Q. Morales, G. Manahira, F. Fenomanana, R. Samba, F. Lahiniriko, Z. M. Chrisostome, V. Vavisoa, P. Soafiavy, and R. Justome. 2019. Toward a just and inclusive environmental archaeology of southwest Madagascar. Journal of Social Archaeology 19 (3):307–32. doi:10.1177/1469605319862072.

- Ellison, A. M., H. L. Buckley, T. E. Miller, and N. J. Gotelli. 2004. Morphological variation in Sarracenia purpurea (Sarraceniaceae): Geographic, environmental, and taxonomic correlates. American Journal of Botany 91 (11):1930–35. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.11.1930.

- Fiedler, S., B. Illich, J. Berger, and M. Graw. 2009. The effectiveness of ground-penetrating radar surveys in the location of unmarked burial sites in modern cemeteries. Journal of Applied Geophysics 68 (3):380–85. doi:10.1016/j.jappgeo.2009.03.003.

- Fitzhugh, W. W. 2019. Paradise gained, lost, and regained: Pulse migration and the Inuit archaeology of the Quebec Lower North Shore. Arctic Anthropology 56 (1):52–76. doi:10.3368/aa.56.1.52.

- Forbes, V., F. Dussault, and A. Bain. 2014. Archaeoentomological research in the North Atlantic: Past, present, and future. Journal of the North Atlantic 26:1–24.

- Forbes, V., P. M. Ledger, D. Cretu, and S. Elias. 2020. A sub-centennial, Little Ice Age climate reconstruction using beetle subfossil data from Nunalleq, southwestern Alaska. Quaternary International 549:118–29. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2019.07.011.

- French, J. C., and P. B. Tomlinson. 1981. Vascular patterns in stems of Araceae: subfamilies Calloideae and Lasioideae. Botanical Gazette 142 (3): 366–381. doi:10.1086/337236.

- Furgal, C. M., and R. Laing. 2012. A synthesis and critical review of the traditional ecological knowledge literature on narwhal (Monodon monoceros) in the eastern Canadian Arctic. Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Research Document 2011/131. Ottawa: Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

- Gearey, B., N. Bermingham, H. Chapman, W. Fletcher, R. Fyfe, J. Quartermaine, and R. van de Noort. 2010. Peatlands and the historic environment. Edinburgh: International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

- Gearey, B., and R. Fyfe. 2016. Peatlands as knowledge archives: Intellectual services. In Investing in peatlands: Delivering multiple benefits, ed. A. Bonn, T. Allott, M. Evans, H. Joosten, and R. Stoneman, 95–114. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Giblett, R. J. 2014. Canadian wetlands: Places and people. Bristol: Intellect Ltd.

- Gladwin, D. 2016. Contentious Terrains: Boglands in the Irish Postcolonial Gothic. Cork: Cork University Press.

- Gleeson, P., and G. Grosso. 1976. Ozette site. In The excavation of water saturated archaeological sites (wet sites) on the northwest coast of North America, ed. D. Croes, 13–44. Ottawa: National Museum of Man.

- Godwin, H. 1981. The archives of the peat bogs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gottesfeld, L. M., and D. H. Vitt. 1996. The selection of Sphagnum for diapers by indigenous North Americans. Evansia 13 (3):103–07.

- Hamilton, S. 2000. Archaeological predictive modelling in the boreal forest: No easy answers. Canadian Journal of Archaeology/Journal Canadien d’Archéologie 24 (1):41–76.

- Harris, E. S. J. 2008. Ethnobryology: Traditional uses and folk classification of bryophytes. The Bryologist 111 (2):169–217. doi:10.1639/0007-2745(2008)111[169:ETUAFC]2.0.CO;2.

- Hartery, L. 2007. The Cow Head complex and the recent Indian period in Newfoundland, Labrador, and the Quebec Lower North Shore. St. John’s: Copetown Press.

- Hartery, L., and T. Rast 2001. Bird cove archaeology project 2000 field season: Final report. Provincial Archaeology Office, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s.

- Herman-Mercer, N. M., R. A. Loehman, R. C. Toohey, and C. Paniyak. 2020. Climate- and disturbance-driven changes in subsistence berries in coastal Alaska: Indigenous knowledge to inform ecological inference. Human Ecology 48 (1):85–99. doi:10.1007/s10745-020-00138-4.

- Hull, S. H. 2002. Tanite uet tshinauetamin? A trail to Labrador: Recent Indians and the North Cove site. MA thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- Huntington, H. P. 2000. Using traditional ecological knowledge in science: Methods and applications. Ecological Applications 10 (5):1270–74. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1270:UTEKIS]2.0.CO;2.

- Hyslop, B. G., and A. J. Colson. 2017. It’s about time: Investigations into the interior of Canada’s boreal forest, Lac Seul. North American Archaeologist 38 (4):299–326. doi:10.1177/0197693117728151.

- Jernigan, K. A., Ed. 2014. A guide to the ethnobotany of the Yukon-Kuskokwim region. Fairbanks: University of Alaska.

- Johnson, C. W. 1985. Bogs of the northeast. Hanover: University Press of New England.

- Johnson, L. M., and E. S. Hunn. 2010. Landscape ethnoecology: Reflections. In Landscape ethnoecology: Concepts of biotic and physical space, ed. L. M. Johnson and E. S. Hunn, 279–97. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Johnson, L. M. 2012. Visions of the land, Kaska ethnoecology, “kinds of place,” and “cultural landscape. In Landscape ethnoecology: Concepts of biotic and physical space, ed. L. M. Johnson and E. S. Hunn, 203–21. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Jones, A. 2010. Plants that we eat. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- Joseph, L. 2021. Walking on our lands again: Turning to culturally important plants and indigenous conceptualizations of health in a time of cultural and political resurgence. International Journal of Indigenous Health 16 (1):165–79.

- Kaplan, S. A., and J. M. Woollett. 2000. Challenges and chokes: Exploring the interplay of climate, history, and culture on Canada’s Labrador coast. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 32 (3):351–59. doi:10.1080/15230430.2000.12003374.

- Karst, A. L., J. A. Antos, and G. A. Allen. 2008. Sex ratio, flowering and fruit set in dioecious Rubus chamaemorus (Rosaceae) in Labrador. Botany 86 (2):204–12. doi:10.1139/B07-127.

- Karst, A. L., and N. J. Turner. 2011. Local ecological knowledge and importance of bakeapple (Rubus chamaemorus L.) in a southeast Labrador Métis Community. Ethnobiology Letters 2:6–18. doi:10.14237/ebl.2.2011.28.

- Kim, E.-J. A., A. Asghar, and S. Jordan. 2017. A critical review of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in science education. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education 17 (4):258–70. doi:10.1080/14926156.2017.1380866.

- Kimmerer, R. W. 2003. Gathering moss: A natural and cultural history of mosses. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press.

- Knudson, K. J., and L. Frink. 2010. Soil chemical signatures of a historic sod house: Activity area analysis of an Arctic semisubterranean structure on Nelson Island, Alaska. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 2 (4):265–82. doi:10.1007/s12520-010-0044-x.

- Koivisto, S., N. Latvakoski, and W. Perttola. 2018. Out of the peat: Preliminary geophysical prospection and evaluation of the mid-Holocene stationary wooden fishing structures in Haapajärvi, Finland. Journal of Field Archaeology 43 (3):166–80. doi:10.1080/00934690.2018.1437315.

- Kuhry, P. 1994. The role of fire in the development of Sphagnum-dominated peatlands in western boreal Canada. Journal of Ecology 82 (4):899–910. doi:10.2307/2261453.

- Lacourse, T., M. A. Adeleye, and J. R. Stewart. 2019. Peatland formation, succession and carbon accumulation at a mid-elevation poor fen in Pacific Canada. The Holocene 29 (11):1694–707. doi:10.1177/0959683619862041.

- Lamentowicz, M., P. Kołaczek, D. Mauquoy, P. Kittel, E. Łokas, M. Słowiński, V. E. J. Jassey, K. Niedziółka, K. Kajukało-Drygalska, and K. Marcisz. 2019. Always on the tipping point – A search for signals of past societies and related peatland ecosystem critical transitions during the last 6500 years in N Poland. Quaternary Science Reviews 225 (105954):1–21. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.105954.

- Lantis, M. 1946. The social culture of the Nunivak Eskimo. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 35 (3):153–323. doi:10.2307/1005595.

- Laugrand, F., and J. Oosten. 2010. Transfer of Inuit qaujimajatuqangit in modern Inuit society. Études/Inuit/Studies 33 (1–2):115–52. doi:10.7202/044963ar.

- Lavoie, M., D. Paré, N. Fenton, A. Groot, and K. Taylor. 2005. Paludification and management of forested peatlands in Canada: A literature review. Environmental Reviews 13 (2):21–50. doi:10.1139/a05-006.

- Lavoie, C., and S. Pellerin. 2007. Fires in temperate peatlands (southern Quebec): Past and recent trends. Botany 85 (3):263–72.

- Lazarus, B., and A. Aullas. 1992. The flora of Nunavik: Edible plants. Tumivut Winter (3):45–49.

- Ledger, P. M. 2018. Are circumpolar hunter-gatherers visible in the palaeoenvironmental record? Pollen-analytical evidence from Nunalleq, southwestern Alaska. The Holocene 28 (3):415–426. doi:10.1177/2F0959683617729447.

- Ledger, P. M., K. J. Edwards, and J. E. Schofield. 2014a. A multiple profile approach to the palynological reconstruction of Norse landscapes in Greenland’s Eastern Settlement. Quaternary Research 82 (1):22–37. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2014.04.003.

- Ledger, P. M., K. J. Edwards, and J. E. Schofield. 2014b. Vatnahverfi: A green and pleasant land? Palaeoecological reconstructions of environmental and land-use change. Journal of the North Atlantic 601 (sp6):29–46. doi:10.3721/037.002.sp605.

- Ledger, P. M., K. J. Edwards, and J. E. Schofield. 2017. Competing hypotheses, ordination and pollen preservation: landscape impacts of Norse landnám in southern Greenland. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 236:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2016.10.007.

- Ledger, P. M., and V. Forbes. 2019. Paleoenvironmental analyses from Nunalleq, Alaska illustrate a novel means to date pre-Inuit and Inuit archaeology. Arctic Anthropology 56 (2):39–51. doi:10.3368/aa.56.2.39.

- Ledger, P. M., L. Girdland-Flink, and V. Forbes. 2019. New horizons at L’Anse aux Meadows. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (31):15341–43. doi:10.1073/pnas.1907986116.

- Lee, M., and G. A. Reinhardt. 2003. Eskimo architecture: Dwelling and structure in the early historic period. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- Lemieux, A.-M., N. Bhiry, and P. M. Desrosiers. 2011. The geoarchaeology and traditional knowledge of winter sod houses in eastern Hudson Bay, Canadian Low Arctic. Geoarchaeology 26 (4):479–500. doi:10.1002/gea.20365.

- Lepofsky, D., and K. Lertzman. 2018. Through the lens of the land: Reflections from archaeology, ethnoecology, and environmental science on collaborations with First Nations, 1970s to the present. BC Studies: The British Columbian Quarterly 200:141–60.

- Lepofsky, D., M. L. Moss, and N. Lyons. 2001. The unrealized potential of paleoethnobotany in the archaeology of northwestern North America: Perspectives from Cape Addington, Alaska. Arctic Anthropology 38 (1):48–59.

- Llano, G. A. 1956. Utilization of lichens in the Arctic and subarctic. Economic Botany 10 (4):367–92. doi:10.1007/BF02859767.

- Lyons, N., T. Hoffmann, D. Miller, S. Huddlestan, R. Leon, and K. Squires. 2018. Katzie & the Wapato: An archaeological love story. Archaeologies 14 (1):7–29. doi:10.1007/s11759-018-9333-2.

- Lyons, N., T. Hoffmann, D. Miller, A. Martindale, K. M. Ames, and M. Blake. 2021. Were the ancient Coast Salish farmers? A story of origins. American Antiquity 86 (3):504–25. doi:10.1017/aaq.2020.115.

- Mackenzie, W. H., and J. R. Moran. 2004. Wetlands of British Columbia: Land management handbook 52. Victoria: BC Ministry of Forests.

- Mauquoy, D., P. D. M. Hughes, and B. van Geel. 2010. A protocol for plant macrofossil analysis of peat deposits. Mires and Peat 7 (6):1–5.

- McAlvay, A. C., C. G. Armstrong, J. Baker, L. B. Elk, S. Bosco, N. Hanazaki, L. Joseph, T. E. Martínez-Cruz, M. Nesbitt, and M. A. Palmer. 2021. Ethnobiology phase VI: Decolonizing institutions, projects, and scholarship. Journal of Ethnobiology 41 (2):170–91. doi:10.2993/0278-0771-41.2.170.

- McGhee, R. 1996. Ancient people of the Arctic. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- McLean, S. 2003. Céide fields: Natural histories of a buried landscape. In Landscape, memory and history anthropological perspectives, ed. J. Stewart and A. Strathern, 47–70. London: Pluto Press.

- Michaelis, D. 2019. The Sphagnum species of the world. Stuttgart: Schweizerbart Science Publishers.

- Milek, K. B. 2006. Houses and Households in Early Icelandic Society: Geoarchaeology and the Interpretation of Social Space. PhD thesis, University of Cambridge.

- Miras, Y., D. Barbier-Pain, A. Ejarque, E. Allain, E. Allue, D. Marín Vettese, B. Hardy, S. Puaud, J. Mangado Llach, and M.-H. Moncel. 2020. Neanderthal plant use and stone tool function investigated through nonpollen palynomorphs analyses and pollen washes in the Abri du Maras, South-East France. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 33:102569.

- Moore, P. D. 2002. The future of cool temperate bogs. Environmental Conservation 29 (1):3–20. doi:10.1017/S0376892902000024.

- Moore, C. 2021. Between the Meadows: The archaeology of Edercloon on the N4 Dromod–Roosky Bypass. Dublin: Transportation Infrastructure Ireland.

- Nadasdy, P. 1999. The politics of TEK: Power and the “integration” of knowledge. Arctic Anthropology 36 (1–2):1–18.

- Native Land Digital. 2021. Native Land Digital. https://native-land.ca/

- Nelson, J. L., E. S. Zavaleta, and F. S. Chapin. 2008. Boreal fire effects on subsistence resources in Alaska and adjacent Canada. Ecosystems 11 (1):156–71. doi:10.1007/s10021-007-9114-z.

- Nicholas, G. P. 1998. Wetlands and hunter-gatherers: A global perspective. Current Anthropology 39 (5):720–31. doi:10.1086/204795.

- Nicholas, G. P. 2006. Decolonizing the archaeological landscape: The practice and politics of archaeology in British Columbia. The American Indian Quarterly 30 (3):350–80. doi:10.1353/aiq.2006.0031.

- Nicholas, G. P. 2001. Wet sites, wetland sites, and cultural resource management strategies. In Enduring records: The environmental and cultural heritage of wetlands, ed. B. A. Purdy, 262–70, Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Nicholas, G. P., A. Roberts, D. M. Schaepe, J. Watkins, L. Leader-Elliot, and S. Rowley. 2011. A consideration of theory, principles and practice in collaborative archaeology. Archaeological Review from Cambridge 26 (2):11–30.

- Norton, H. H. 1981. Plant use in Kaigani Haida culture: Correction of an ethnohistorical oversight. Economic Botany 35 (4):434–49. doi:10.1007/BF02858592.

- O’Rourke, M. J. E. 2018. Risk and value: Grounded visualization methods and the assessment of cultural landscape vulnerability in the Canadian Arctic. World Archaeology 50 (4):620–38. doi:10.1080/00438243.2018.1459205.

- Oberndorfer, E., T. Broomfield, J. Lundholm, and G. Ljubicic. 2020. Inuit cultural practices increase local-scale biodiversity and create novel vegetation communities in Nunatsiavut (Labrador, Canada). Biodiversity and Conservation 29 (4):1205–40. doi:10.1007/s10531-020-01931-9.

- Oberndorfer, E., N. Winters, C. Gear, G. Ljubicic, and J. Lundholm. 2017. Plants in a “sea of relationships”: Networks of plants and fishing in Makkovik, Nunatsiavut (Labrador, Canada). Journal of Ethnobiology 37 (3):458–77. doi:10.2993/0278-0771-37.3.458.

- Ólafsson, G., and H. Ágústsson. 2000. The reconstructed medieval farm in Þjórsárdalur and the development of the icelandic turf house. Reykjavík: National Museum of Iceland.

- Oswalt, W. H. 1957. A western Eskimo ethnobotany. Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska 6 (1):16–36.

- Park, R. W. 1988. “Winter houses” and qarmat in Thule and historic Inuit settlement patterns: Some implications for Thule studies. Canadian Journal of Archaeology/Journal Canadien d’Archéologie 12:163–75.

- Pedersen, C., M. Otokiak, I. Koonoo, J. Milton, E. Maktar, A. Anaviapik, M. Milton, G. Porter, A. Scott, and C. Newman. 2020. ScIQ: An invitation and recommendations to combine science and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit for meaningful engagement of Inuit communities in research. Arctic Science 6 (3):326–39. doi:10.1139/as-2020-0015.

- Pigford, A.-A. E., and C. Zutter. 2014. Reconstructing historic Labrador Inuit plant use: An exploratory phytolith analysis of soapstone-vessel residues. Arctic Anthropology 51 (2):81–96. doi:10.3368/aa.51.2.81.

- Raftery, B. 1995. Trackway excavations in the Mountdillon bogs, Co. Longford, 1985-1991. Dublin: Crannóg Publications.

- Rashid, I., S. H. Mir, D. Zurro, R. A. Dar, and Z. A. Reshi. 2019. Phytoliths as proxies of the past. Earth-Science Reviews 194:234–50.

- Renouf, M. A. P. 2005. A review of Palaeoeskimo dwelling structures in Newfoundland and Labrador. Études/Inuit/Studies 27 (1–2):375–416. doi:10.7202/010809ar.

- Renouf, M. A. P., T. Bell, and J. Macpherson. 2009. Hunter-gatherer impact on Subarctic vegetation: Amerindian and Palaeoeskimo occupations of Port au Choix, northwestern Newfoundland. Arctic Anthropology 46 (1–2):176–90. doi:10.1353/arc.0.0031.

- Renouf, M. A. P., T. Bell, and M. Teal. 2000. Making contact: Recent Indians and Palaeoeskimos on the island of Newfoundland. In Identities and cultural contacts in the Arctic, ed. M. Appelt, J. Berglund, and H. C. Gulløv, 106–19. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark and Danish Polar Center, Danish Polar Center Publication.

- Roy, N., N. Bhiry, and J. Woollett. 2012. Environmental change and terrestrial resource use by the Thule and Inuit of Labrador, Canada. Geoarchaeology 27 (1):18–33. doi:10.1002/gea.21391.

- Rydin, H., and J. K. Jeglum. 2013. The biology of peatlands. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schultz, J. J. 2007. Using ground-penetrating radar to locate clandestine graves of homicide victims: Forming forensic archaeology partnerships with law enforcement. Homicide Studies 11 (1):15–29. doi:10.1177/1088767906296234.

- Small, E., and J. Cayouette. 2016. 50. Sedges – The key sustainable resource for Arctic biodiversity. Biodiversity 17 (1–2):60–69. doi:10.1080/14888386.2016.1164624.

- Stefánsson, H. 2019. From earth: Earth architecture in Iceland. Reykjavík: Gullinsnið.

- Steinberg, J. M. 2004. Note on organic content of turf walls in Skagafjörður, Iceland. Archaeologia Islandica 3:61–70.

- Suttles, W. 1955. Katzie ethnographic notes. Anthropology in British Columbia, memoir no. 2. Victoria: British Columbia Provincial Museum.

- Tantaquidgeon, G. 1932. Notes on the origin and uses of plants of the Lake St. John Montagnais. The Journal of American Folklore 45 (176):265–67. doi:10.2307/535384.

- Teal, M. A. 2001. An archaeological investigation of the Gould site (EeBi-42) in Port au Choix, northwestern Newfoundland: New insight into the recent Indian Cow Head complex. MA thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- Tester, F. J., and P. Irniq. 2008. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: Social history, politics and the practice of resistance. Arctic 61 (1):48–61.

- Thiem, B. 2003. Rubus chamaemorus L.- a boreal plant rich in biologically active metabolites: A review. Biological Letters 40 (1):3–13.

- Thieret, J. W. 1956. Bryophytes as economic plants. Economic Botany 10 (1):75–91. doi:10.1007/BF02985319.

- Turner, N. J. 1998. Plant technology of First Peoples in British Columbia. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Turner, N. J. 2004. Plants of Haida Gwaii. Xaadaa Gwaay guud gina k’aws (Skidegate), Xaadaa Gwaayee guu giin k’aws (Massett). Winlaw: Sono Nis Press.

- Turner, N. J. 2014. Ancient pathways, ancestral knowledge: Ethnobotany and ecological wisdom of Indigenous peoples of northwestern North America, Vol. 2. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press.

- Turner, N. C., and M. A. M. Bell. 1971. The ethnobotany of the coast Salish Indians of Vancouver Island. Economic Botany 25 (1):63–99. doi:10.1007/BF02894564.

- Turner, N. C., and M. A. M. Bell. 1973. The ethnobotany of the southern Kwakiutl Indians of British Columbia. Economic Botany 27 (3):257–310. doi:10.1007/BF02907532.

- van der Sanden, W. A. 2013. Bog bodies: Underwater burials, sacrifices, and executions. In The Oxford handbook of wetland archaeology, ed. F. Menotti and A. O’Sullivan, 401–16. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- van Hoof, J., and F. van Dijken. 2008. The historical turf farms of Iceland: Architecture, building technology and the indoor environment. Building and Environment 43 (6):1023–30. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2007.03.004.

- van Wee, B., and D. Banister. 2016. How to write a literature review paper?. Transport Reviews 36 (2):278–88. doi:10.1080/01441647.2015.1065456.

- Wenzel, G. W. 2004. From TEK to IQ: Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and Inuit cultural ecology. Arctic Anthropology 41 (2):238–50. doi:10.1353/arc.2011.0067.

- Wyndham, F. S. 2017. The trouble with TEK. Ethnobiology Letters 8 (1):78–80. doi:10.14237/ebl.8.1.2017.1006.

- Xu, J., P. J. Morris, J. Liu, and J. Holden. 2018. PEATMAP: Refining estimates of global peatland distribution based on a meta-analysis. Catena 160:134–40. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2017.09.010.

- Zoltai, S. C., L. A. Morrissey, G. P. Livingston, and W. J. Groot. 1998. Effects of fires on carbon cycling in North American boreal peatlands. Environmental Reviews 6 (1):13–24. doi:10.1139/a98-002.

- Zutter, C. 2009. Paleoethnobotanical contributions to 18th-century Inuit economy: An example from Uivak, Labrador. Journal of the North Atlantic 2:23–32.