Abstract

This paper brings the transitions literature into conversation with constructivist Science and Technology Studies (STS) perspectives on participation for the first time. In doing so we put forward a conception of public and civil society engagement in sustainability transitions as co-produced, relational, and emergent. Through paying close attention to the ways in which the subjects, objects, and procedural formats of public engagement are constructed through the performance of participatory collectives, our approach offers a framework to open up to and symmetrically compare diverse and interconnected forms of participation that make up wider socio-technical systems. We apply this framework in a comparative analysis of four diverse cases of civil society involvement in UK low carbon energy transitions. This highlights similarities and differences in how these distinct participatory collectives are orchestrated, mediated, and subject to exclusions, as well as their effects in producing particular visions of the issue at stake and implicit models of participation and ‘the public’. In conclusion we reflect on the value of this approach for opening up the politics of societal engagement in transitions, building systemic perspectives of interconnected ‘ecologies of participation’, and better accounting for the emergence, inherent uncertainties, and indeterminacies of all forms of participation in transitions.

1. Introduction

Bringing about transitions to sustainability has emerged as one of the key organizing global challenges over the past four decades (United Nations, Citation2012). This imperative has become particularly crucial in the energy domain faced with the so-called ‘trilemma’ of global climate change, energy security, and socio-economic challenges and inequalities (Hammond & Pearson, Citation2013). Despite conflicting interpretations of the problem and visions of the future, substantial efforts are now underway—from global to national and local levels—to initiate more sustainable and low carbon energy systems. This has been the case in the UK, the empirical focus of this paper, linked to political momentum for tackling climate change and the UK government's legally binding target of an 80% cut in carbon emissions by 2050 (HM Government, Citation2009).

It is in such contexts that the sustainability transitions field has emerged in order to understand, anticipate, and intervene to potentially ‘steer’ system change in energy and other socio-technical domains (Foxon, Citation2013; Geels & Schot, Citation2007; Hoogma, Kemp, Schot, & Truffer, Citation2002; Rotmans and Loorbach, Citation2010). Whilst the field has made considerable strides in developing approaches that provide insights into system dynamics, emerging critiques have centred on the limited attention to the role of power and politics in transition processes (Shove & Walker, Citation2007; Smith & Stirling, Citation2007). One particular critique is the way this generally technologically focused research field has overlooked the role of the public and democratic engagement in transition processes (Lawhon & Murphy, Citation2011). As Hendriks (Citation2009, p. 341) has observed, ‘[r]ecent debates on how to “manage” policy transitions to sustainability have been curiously silent on democratic matters, despite their potential implications for democracy’.

To address this, the principal aim of this paper is to bring sustainability transitions theory into conversation with constructivist and relational STS perspectives on public participation in order to initiate a new way of conceiving of and thinking about participation in transitions. In doing this we move beyond popular ‘residual realist’ (Chilvers & Kearnes, Citation2016) notions of participation—evident in sustainability transitions and other domains—which adopt specific, fixed, and normatively pre-given models of participation itself (e.g. deliberative, individualist, etc.), the public (e.g. as innocent citizens, consumers, etc.), and definitions of the issues at stake. The emphasis tends to be on single one-off events, as well as devising, ‘scaling up’ and evaluating public involvement methods (e.g. Renn, Webler, & Wiedemann, Citation1995), based on pre-given normative principles about what constitutes good deliberation (e.g. Habermas, Citation1984; Dryzek, Citation1990).

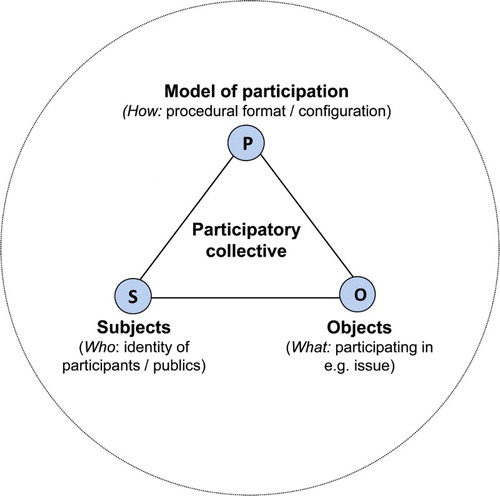

Instead, we put forward a constructivist and relational STS perspective which views participation as an emergent and co-produced phenomenon in itself, and pays particular attention to the circumstances of its construction, performance, productive dimensions, and effects (Callon, Lascoumes, & Barthe, Citation2009; Chilvers, Citation2009; Irwin, Citation2006; Irwin & Michael, Citation2003; Laurent, Citation2011; Marres & Lezaun, Citation2011). The who (publics), what (issues), and how (procedural formats) of participation do not externally exist in a natural state but are actively constructed through the performance of collective participatory practices. Our analytical focus is on collectives of participation ‘in the making’: emergent socio-material collectives of humans, non-human artefacts, and other elements through which publics engage in addressing collective public problems. This more open definition of participation offers a framework to symmetrically compare diverse and interconnected forms of participation that make up wider socio-technical systems.

Our paper has two core analytical themes. Firstly, it draws attention to the processes by which collectives of participation in transitions are orchestrated: the process by which they get made and the exclusions that occur in terms of social actors or competing visions of energy futures. Secondly, our approach draws attention to the way in which these collectives are productive in multiple ways: producing issues and visions as well as particular ‘models’ of participation and identities of the public. Through attention to these two facets of participation we begin to appreciate the partiality of all forms of participation and the degree to which different possibilities for system change are either opened up or closed down by different collectives (Stirling, Citation2008). What is more, these collectives of participation have material dimensions and effects (Marres, Citation2012). They are not just discursive spaces, often being attempts to explicitly intervene in system change.

This approach has at least four important implications for the analysis of sustainability transitions. Firstly, it offers a new perspective on public participation in transitions, one which moves beyond the compartmentalized tendency of existing approaches to attend to specific parts of ‘the system’—for example the relative focus of deliberative processes on sites of institutional decision-making, social practice theory's existing emphasis on domestic settings of everyday practice, social movement theory's focus on sites of situated protest and activism, and so on—to open up to the diversities of participation and the ways in which publics are constantly being made and remade in attempts to change socio-technical systems. Secondly, this highlights the multiplicity of possible forms of participation, the competing normativities that underpin these, and the inherent partialities of them all. Thirdly, it offers a different way of thinking about actor dynamics in system change, bringing them more to the forefront of analyses. We choose to focus on the enrolment of publics in this paper, but the broader approach could be applied to multiple forms of participation across energy systems. Finally, it offers a way of exploring the politics of system change. This is particularly evident when the framing effects or modes of orchestration of different participatory collectives are compared alongside each other.

The conceptual approach and empirical analysis developed within this paper build on the outputs of an international workshop that was convened in order to explore questions of participation in sustainable energy transitions (see Chilvers & Longhurst, Citation2012).Footnote1 The analysis of workshop outputs has been augmented by drawing on relevant studies in the literature and undertaking further documentary analysis of four different examples of energy participation and publics ‘in the making’. The purpose of this novel comparative analysis is to reveal the situated co-productions of diverse collectives of public engagement in transition processes—opening up the notion of participation in transitions beyond formal deliberative or institutionally mediated processes—and the way in which these share critical similarities and differences from a constructivist perspective. Before presenting this analysis, and considering implications for research and practice in the final section of the paper, we begin in the next section by outlining how ideas of participation are conceived in existing strands of the transitions literature and how a constructivist STS perspective on participation can both open up and deepen these understandings.

2. Participation in Transitions

2.1. Transitions and Public Participation

Over the last two decades the interdisciplinary field of sustainability transitions has emerged as a vibrant research community oriented around the challenge of explaining and intervening in socio-technical systems (Markard, Raven, & Truffer, Citation2012). Drawing on a range of disciplines—including innovation studies, history, evolutionary economics, sociology, and science and technology studies—a number of different branches of theory have stabilized including the multi-level perspective (Rip & Kemp, Citation1998), strategic niche management (SNM; Kemp, Schot, & Hoogma, Citation1998), transition management (TM; Loorbach, Citation2010) and technological innovation systems (Markard & Truffer, Citation2008). All of these strands share a common interest in explaining how new technological configurations become stabilized with, in some cases such as TM and SNM, specific recommendations as to how such systems can be steered or modulated. Notwithstanding the evident growth and success of the field to date, it has inevitably attracted some criticism. One such critique is that much transitions theory is underpinned by a fundamentally technologically centred and market-driven model of system change (Lawhon & Murphy, Citation2011) and is thus overly biased towards technological innovation as the principle mode of systemic intervention (Shove & Pantzar, Citation2005). One consequence of this is that it obscures the potential influence of a range of other actors. Thus, as Grin, Rotmans, and Schot (Citation2010, p. 331) note, the role of consumers and ‘grassroots’ civil society initiatives in transitions is underrated and under-conceptualized within the literature. In other words, recognizing the distributed nature of power within modern societies opens the door for multiple routes of intervention (Meadowcroft, Citation2007), from various actors including various kinds of ‘public’ and diverse forms of democratic engagement.

One of the few existing studies of participation and deliberation in sustainability transitions is Hendriks’ (Citation2008, Citation2009; Hendriks & Grin, Citation2007) analysis of democratic and inclusionary processes in Dutch TM experiments. The democratic criteria of inclusion (who is involved/participates?), and legitimacy and accountability (how should reforms be legitimized and accountable to the public?), are used to assess TM practice. Transition arenas are shown in this case to be distinctly ‘technocratic’. The emphasis being on facilitating partnerships between frontrunners, entrepreneurs, and representing their elite/specialist knowledges, to the exclusion of many potentially affected actors in civil society and the wider public. While calling for the design of more inclusive sustainability transitions and opening up important questions of democracy in transitions, Hendriks’ analysis to some extent narrows down possible imaginations of participation and the public. For example, the analytical focus on involvement in policy decision-making brackets out forms of participation associated with ‘distributed innovation’ and more active forms of citizenship (Felt & Wynne, Citation2007). Furthermore, the implicit emphasis on how sustainability transition interventions should/could be made more ‘democratic’ forecloses wider appreciation of the diverse sites at which social actors are already and continuously engaged in sustainable energy transitions.

Whilst not explicitly analysing the dynamics of participation per se, some strands of the transitions literature have begun to explore the multiple roles that publics and civil society actors play in system innovation (see also Walker & Cass, Citation2007). Here we draw attention to four different approaches and strands of theory that have engaged with different notions of societal and public engagement in transitions, namely: deliberative democratic theory, practice theory, social movement theory and work on ‘grassroots’ innovation. As illustrated in the above discussion of TM experiments, a common way of framing energy publics is in terms of ‘deliberative citizens’ who are able to deliberate and be involved in energy transitions through voicing their opinions in discursive fora or surveys, which inform decisions made by others (e.g. Butler, Parkhill, & Pidgeon, Citation2013). ‘Grassroots innovations’ are civil society groups that are actively building new forms of institution, organization, and commitment rather than just articulating political claims or objections to the status quo. Often ideologically motivated, they are innovating to meet specific social or environmental goals, thus bringing forward new forms of innovation and action (Seyfang & Smith, Citation2007). The work on grassroots innovations has some overlap with a broader literature on the role that social movements can play in shaping transitions, drawing on various strands of social movement theory (Smith, Citation2012). Here civil society actors are framed as political actors engaged in contentious politics (Saunders, Citation2012). Finally, work on the sociology of consumption adopts social practice theory to explore the role that (energy) consumers play in constructing and reproducing energy systems. In developing an analytical perspective in which practices are the central object of analysis, consumers are recast as ‘practitioners’ who interact with the energy system through the daily performances of everyday life (Shove, Citation2012).

These various literatures on practices, deliberative democracy, social movements, and grassroots innovations all open up different perspectives on the multiple roles that public actors can play in transitions processes, but each also remains somewhat partial, bracketing out the primary foci of the others. Indeed it is notable that specific descriptive terms such as ‘civil society’, ‘publics’, and ‘practitioners’ are predominately associated with particular forms and theories of public participation. In this paper we use the term public engagement to encompass all of these diverse forms of public and civil society participation in sustainability transitions. Drawing on insights from social movement theory, Smith (Citation2012) does attempt to map the breadth and variety of public engagement in energy transition processes. In doing so he suggests that there is a need for more detailed work on these different forms of participation, seeking to understand their interactions and effects on potential transition pathways. In what follows we answer this call to open up to diversities of democratic engagement in transitions, while also moving beyond dominant perspectives that define a priori what it means to participate in transitions, through using STS theoretical insights to explore the co-production of participatory collectives. A significant advantage of this approach is that it allows comparative analysis of diverse forms of public engagement across socio-technical systems.

2.2. Participation as Emergent, Relational and Co-Produced

Constructivist STS perspectives on public engagement can be seen to pose an altogether different theory of participation compared to mainstream approaches in political and democratic theory (e.g. Dryzek, Citation1990; Habermas, Citation1984), which have informed the transitions literature and indeed earlier procedurally oriented work on public engagement in STS (e.g. Rowe & Frewer, Citation2000). Rather than adopt a procedural focus on methods and/or normative principles that define pre-given models of what constitutes good deliberation and participation in advance, a constructivist and co-productionist STS approach views all forms of participation as emergent phenomena and social experiments in themselves, paying close attention to their construction, performance, productive dimensions, and effects (Irwin, Citation2006). While specific approaches vary, key works developing this perspective (e.g. Barry, Citation2001; Callon et al., Citation2009; Irwin & Michael, Citation2003; Marres & Lezaun, Citation2011) are inspired by the relational ontologies of actor network theory (ANT) and assemblage theory in conceiving of forms of public engagement and participation as heterogeneous collectives of human and non-human actors, devices, settings, theories, public participants, procedural techniques, and other artefacts.

Actors are included or excluded from a collective of participation through mechanisms of enrolment and its eventual constitution highlights the productive ways in which approaches to meditation construct the objects (or issues; Marres, Citation2007), subjects (or publics/participants; Felt & Fochler, Citation2010; Irwin & Michael, Citation2003), and the specific procedural formats (or political philosophies; Lezaun, Citation2007; Lezaun & Soneryd, Citation2007) of participation. This forms the basis of the analytical framework put forward in this paper, as illustrated in . While different authors developing this perspective tend to foreground one of these dimensions, emphasizes how all three are always co-produced together through the performance of collective participatory practices (see also Chilvers & Kearnes, Citation2016). All forms of participation are thus both shaped by and actively construct human subjectivities, objects of concern, and models of participation. In introducing this alternative way of viewing participation in transitions, our relative emphasis in this paper is on the construction and co-production of situated participatory collectives. The outer circle in denotes the setting in which the performance of participation occurs, of which our interest in the following analysis is the immediate site and situation of participation. It is important to note, however, that the setting which situated participatory collectives are shaped by (and in turn shape) encompasses extant orders—in the current framework the systemic, institutional, and constitutional stabilities relating to the three dimensions identified in . These wider systemic-constitutional relations should become an important feature in future analyses of the co-production of energy systems and social order (cf. Chilvers & Kearnes, Citation2016; Jasanoff, Citation2004).

Figure 1. A socio-material collective of participation, which emerges through the co-production of subjects (S), objects (O) and procedural formats (P) in relation the setting and extant orders (outer circle).

Understanding participation as emergent and co-produced in this way offers a number of analytical possibilities, of which we focus on two in this paper. The first centres on the work that goes into orchestrating a collective of participation through processes of enrolment and mediation. Enrolment refers to the way in which different (human and non-human) actors are drawn into a particular form of participatory collective practice and definition of the issue at stake. Mechanisms for enrolment can be a highly centralized and controlled by a small number of actors in the collective. This tends to be the case in formalized ‘technologies of participation’—such as citizens panels, focus groups, or other established deliberative participatory techniques—which have standardized design blueprints for enrolling ‘representative’ samples of human subjects and configuring participatory collectives. Such instances are often mediated by professional facilitators who invest work in disciplining participants to conform to a particular political epistemology or normativity of participation (Lezaun, Citation2007), moves that can be subject to resistance by participating actors (Felt & Fochler, Citation2010). The enrolment of actors into a collective of participation can otherwise be more distributed, rhizomic, and fluid where multiple actors simultaneously enrol one and other, which has been observed in forms of counter-scientific, informal, and citizen-led forms of engagement (Irwin & Michael, Citation2003).

Mediation refers to the way in which a participatory collective is held together by different devices, processes, skills, or ‘technologies of participation’. For example, a particular collective of participation might be mediated by a set of formal procedures, by an online survey, or by memberships to a specific group. Whilst human agents often make purposive choices about the forms of mediation that are used to cohere a collective, powers of enrolment and mediation are not just human qualities and can be imbued in material objects, devices, or technologies in shaping heterogeneous collectives and maintaining connections between actors and across sites (Barry, Citation2001; Marres, Citation2007, Citation2012). While these forms of orchestration can differ in emphasis between collectives, highlighting the power of different actants to bring participation into being, a constant is that all forms of participation are by definition exclusive, lead to exclusions, are always partial, framed in particular ways, and subject to ‘overflows’ (Callon et al., Citation2009). This marks a departure from the emphasis of inclusion and inclusivity in residual realist and procedural theories of participation. Continual work invested in enrolment and mediation is simultaneously subject to forms of resistance—both ‘internal’ and ‘external’ to the collective—which attempt to actively reject, contest, or modulate moves to stabilize the three dimensions identified in (Laurent, Citation2011).

The second main analytical focus in this paper to be drawn from constructivist STS understandings of participation centres on the productive dimensions and effects of emergent participatory collectives. In particular we focus on the ways in which diverse collectives of participation in low carbon energy transitions construct particular definitions of the issue at stake, models of participation, and the public (i.e. the three dimensions identified in ).

With respect to the issue in question around which publics are brought into being (Marres, Citation2007), collectives of participation can be subject to powerful framing effects, especially in institutionally orchestrated processes where the matters of concern are often pre-defined by incumbent interests (Chilvers & Burgess, Citation2008; Stirling, Citation2008). Participatory procedures and forms of mediation have also been shown to ‘fix’ the issue in technical terms thus constructing and maintaining a boundary via-a-vis the social and ethical concerns of ‘mobile’ public participants (Lezaun & Soneryd, Citation2007). Yet, the issue remains emergent and coproduced amongst actors enrolled into a collective, in defining both how problems are framed and, as part of this, anticipatory visions of desired futures (what should be done and why). Even when this is a discursive process it can indirectly link to material commitments in shaping future socio-technical pathways.

Emergent collectives of participation produce publics as well (Braun & Schultz, Citation2010; Michael, Citation2009; Pallett & Chilvers, Citation2013) through constructing particular identities of the actors involved, such as: ‘innocent citizens’ or ‘pure publics’ that are assumed to have limited prior knowledge of the issue in question or deemed to be ‘representative’ of a wider public; ‘interested’ or ‘affected’ publics who have a personal attachment to the object of participation, including through exposure to risk or illness; or more ‘active’ or ‘innovative citizens’ who are constructed as bringing about various forms of distributed action. From this perspective it is evident that TM produces participants as ‘frontrunners’ and SNM produces ‘niche actors’. The relations between actors in a collective also create a particular model of participation. So while particular models of participatory democracy—ranging from consensual to agonistic—have become the dominant taken-for-granted meanings of participation in many policy fields, including transitions management, normativities of participation are, in fact, highly variable and are constructed through the situated performance and socio-material make up of participatory collectives (Marres & Lezaun, Citation2011).

A relational co-productive perspective on public engagement in transitions therefore draws attention to the fact that all forms of participation and ‘the public’ do not exist in a pre-given natural state, but are actively constructed and orchestrated. It therefore eschews an idealized, pre-defined model of what good participation is, in favour of an empirically oriented exploration of how diverse forms of participation get made and their multiple productive effects in relation to wider systems.

3. Diverse and Emergent Participation in UK Low Carbon Energy Transitions

In order to empirically explore this emergent perspective on participation we draw on four distinct case studies of public engagement in UK low carbon energy transitions. These cases are illustrative in that they have been specifically selected to reflect diverse forms of public engagement in energy transitions and are intended to provide the basis for comparative analysis that has not been attempted before, at least in the transitions literature. Each case is therefore intended to represent a substantively different form of participation within the overall issue space of a low carbon transition. Cases were therefore selected on the principle of maximum variation, where four cases are selected in order to explore variation in outcome and process (Flyvbjerg, Citation2001). These cases therefore are reflective of four different archetypes of public engagement:

a government-led deliberative consultation (DECC 2050);

a technological trial linked to domestic energy practices, called the Visible Energy Trial (VET);

an environmental social movement, the Camp for Climate Action (CCA); and

an example of grassroots innovation, the Dyfi Solar Club (DSC).

Importantly, each of these cases is associated directly with one of the particular approaches to framing and understanding public engagement in (energy) transitions outlined in section 2.1, namely: deliberative public participation; practice theory; social movement theory; and grassroots innovation. Each of these particular approaches has its own conceptual and theoretical vocabulary for exploring particular forms of participation at specific sites in wider energy systems. Our purpose in this paper is to go beyond these pre-given normativities of participation and to instead comparatively explore the emergence and co-production of participatory collectives that are reflective of these archetypes, drawing out both similarities and differences between the cases. Whilst each of these cases are, as individual collectives, fairly well defined and of a modest scale, they are all representative of a wider diversity of different forms of public participation. Furthermore, should the energy system trajectory move towards an even more distributed configuration, such forms of participation would become increasingly significant and widespread.

In exploring these diverse forms of participation we are interested in the two specific analytical themes highlighted in section 2.2 above. The first relates to how the collective of participation emerges and is orchestrated. What forms of enrolment, mediation, and exclusions are involved? Secondly, what are the productive dimensions and effects of the participatory collective—in terms of the definition of the issue at stake, the model of participation and the public? In what follows each of the four cases are analysed in turn in relation to these two main analytical themes. In doing this we draw on material from the international workshop where the four cases were developed through a process of expert elicitation and considered as part of a broader analysis (see Chilvers & Longhurst, Citation2012).Footnote2 This initial evidence and analysis from the workshop has been deepened through additional qualitative analysis of documentary grey and academic literature sources, which have been coded against the two main analytical themes just outlined. We conclude this section with a comparative analysis that draws out key similarities and differences across the four cases.

3.1. Energy 2050 Pathways Public Dialogue

The DECC 2050 Public Dialogue was a public participation process intended to enable the public to understand the scale of the challenge of an 80% reduction in greenhouse gasses whilst exploring the trade-offs involved in their own preferred solutions (Comber & Sheikh, Citation2011, p. 12). The dialogue consisted of local deliberative workshops, where participants interacted with the DECC 2050 calculator to explore different energy pathways, alongside an advisory youth panel and a web-based process where publics engaged with a ‘My2050’ online ‘serious game’. In this case study we focus in particular on the deliberative workshops which were designed and facilitated by the market research company Ipsos-MORI. Three workshops were held in London, Cumbria, and Nottingham, attended by 40, 27, and 19 participants, respectively. The process of enrolment was centralized and institutional, controlled by key actors within the energy regime who enrolled specific categories of participant deemed to be community leaders: local politicians; elected members of boards and committees; local business forum representatives; local Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) representatives. Initial participants were approached via ‘active search’ and use of a government database and then encouraged to suggest other possible recruits. There were some problems with recruiting participants, particularly elected representatives (Ipsos-MORI, Citation2011, p. 17). As the workshops were invited small-scale forms of participation there were significant exclusions in terms of geography and of actors who were not deemed to be representative of the community.

The collective was mediated primarily through a specified technology of participation, a citizen panel-type deliberative workshop format that was organized according to the Sciencewise-ERC guiding principles.Footnote3 The DECC 2050 pathways calculator was an important technology within this collective, governing the way in which the participants were able to develop future pathways. Further subsidiary forms of orchestration were the tendering processes and legal contracts that enrolled and governed professional organizations such as Ipsos-MORI. Within this process it was therefore DECC and Sciencewise-ERC who set the parameters of the participatory space in terms of the issue definition and how the participatory process would be managed.

The resistance within this collective related primarily to the way in which the DECC 2050 calculator framed the low carbon transition. Some participants challenged the framing of the issue, and refused to reach the 80% reduction targets (Ipsos-MORI, Citation2011,p. 17). The fact that people had strong views about certain technologies was also a problem for the calculator, which assumes ‘rational discussion based on facts’ and meant that that some people found it difficult to use (ibid). Participants also challenged the range of choices available, the lack of cost data, and the lack of accounting for other factors such as fossil fuel depletion or future technological development (Comber & Sheikh, Citation2011, p. 40; Ipsos-MORI, Citation2011, p. 35). Furthermore, it was felt that behaviour change was not fully accounted for and the assumptions on the demand side could have been more radical.

The issue produced by the DECC 2050 deliberative process was therefore heavily framed by the UK Government's commitment to achieving an 80% reduction in carbon emissions by 2050, based on 1990 levels, a legally binding obligation as set out in the Climate Change Act (2008). The process explicitly framed the fact that achieving this target required specific technological choices to be made. The vision was therefore one of a technocratic and managerialist low carbon energy transition, one that ignored the potential political and social implications. For example, the levers on the 2050 Pathways tool predominately relate to the deployment of a pre-defined set of different technological mixes. Secondly, the deployment of technology is portrayed as unproblematic. The fact that certain technologies might be politically controversial (nuclear, wind) or unproven (carbon capture and storage) is not foregrounded. Thirdly, the centrality of ‘choice’ and the way in which this is embodied in the tools suggests a high degree of control over the energy system, that successful governance of the system is straightforward, and not in any way partial or contingent. The model of participation produced through this process was one which was invited, deliberative, and professionally facilitated. The imaginary of the public produced by the DECC 2050 Dialogue was predominantly one of ‘deliberative citizens’ that have to become informed and educated in order to effectively deliberate and make judgements on complex issues.

3.2. Camp for Climate Action

The CCA (otherwise known as ‘Climate Camp’) was an environmental social movement which organized a series of direct action events between 2006 and 2011 across the UK. Taking the form of an annual protest camp, the first event was located at the DRAX power station in West Yorkshire, whilst in 2008 it targeted the Kingsnorth power station in Kent. The various locations of the climate camps were selected for their symbolic connection to carbon emissions. Direct action against perceived causes of climate change was one of the four stated purposes of the Climate Camp movement. The others included to educate; to build a movement against climate change; and to provide a demonstration of sustainable living (Saunders, Citation2012). In relation to the latter objective, the Camp itself took the form of a low impact community whereby specific attention was paid to minimizing the ecological impact of the event, which offered an example of the possibilities of sustainable living.

CCA emerged from the multiple networks of UK radical environmental activism (Plows, Citation2008). Therefore, the camp as a whole was orchestrated by a set of experienced environmental activists, who, to a greater extent, were self-defined anti-authoritarians and anarchists (Saunders, Citation2012). However, it is important to note that the process of orchestration for the camps was decentralized and inspired by an ‘autonomous’ political philosophy that was manifested in leaderless, horizontal organization principles (Woodsworth, Citation2008). The enrolment and organization of the camps occurred through self-organized regional networks which subsequently formed physical ‘neighbourhoods’ at the actual camps. Whilst ‘activists’ formed the core participants of the camps other categories of social actor were also drawn in, including ‘novice’ activists, local protesters (e.g. at Heathrow in 2007), and prominent green spokespeople (e.g. George Monbiot at Kingsnorth). Climate science was also enrolled in the CCAs, particularly at Heathrow where the activists marched under the banner ‘We are armed only with peer-reviewed science’ (Schlembach, Lear, & Bowman, Citation2012). During the camps themselves the mediation of the collective was primarily via daily neighbourhood meetings using consensus decision-making from which a spokesperson was sent to a central meeting. Such carefully managed processes were intended to guarantee the cohesion of the collective and ensure that its decisions were democratic.

Despite the carful mediation of the collective, certain internal tensions did arise. For example, at the 2008 Kingsnorth camp a conflict emerged surrounding the perceived anti-coal stance of the camp. A former National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) official suggested that the antipathy towards coal reflected a form of class politics that excluded the interests of working class people.Footnote4 Another debate that emerged at the Kingsnorth camp related to the extent to which radical activism should engage with the state. One consequence of this was an open letter from a group of ‘Anti-authoritarians’ who felt the camp was losing touch with its anti-capitalist roots, which could be understood as a form of resistance to the consensual-discursive processes (Saunders & Price, Citation2009). In addition to these ‘internal’ tensions the CCAs were subject to other forms of external resistance, including aggressive policing and some objection to the camps from local residents (Saunders & Price, Citation2009).

CCA produced an ‘uninvited’ model of participation (Wynne, Citation2007) that focused on the production of counter-discourses relating to climate change and which was organized according to decentralized and autonomous politics. The camps can be understood as an explicit attempt to create a form of political space, albeit that this space was often contested (Saunders & Price, Citation2009; Schlembach, Citation2011; Schlembach et al., Citation2012). A particular function of this space was to appraise the strategic repertoire for tackling climate change both generally (i.e. ‘what kind of solutions are necessary?’) and specifically (i.e. ‘what actions should we take?’). Thus, in the latter case, the discussions sometimes closed down around a commitment to a specific form of direct action. Whilst the decision-making processes themselves were open, the underlying anti-technological stance of many CCA activists meant that technologies such as nuclear and carbon capture were excluded as viable solutions to the climate issue. The form of public produced was a form of sustainability citizenship where citizens are active in shaping future possible pathways (Plows, Citation2008). However, in defining climate change as a systemic problem, the CCA challenged the discourses of ‘individual lifestyle change’ that were promoted by mainstream environmentalism and government bodies. The issue framing produced by the climate camps was that the causes of climate change are related to the incumbent (capitalist) political economy (Saunders, Citation2012). In doing so it framed the issue of climate change as a political and moral issue not just a technical one.

3.3. Visible Energy Trial

The VET was a collaborative venture between a small company who were developing visual display monitors—devices that produce visual displays of domestic energy consumption—(Green Energy Options (GEO)), British Gas, an academic consultancy specializing in data mining (SYS Consulting Ltd (SYSCo)) and researchers from the University of East Anglia (UEA). Throughout 2008–2009, 275 households from across eastern England were recruited to trial three different types of In Home Display (IHD) of varying complexity, plus a control group. As part of this wider project, social scientists from the UEA also undertook longitudinal qualitative research with a smaller cohort of participants—15 ‘early adopter’ households—exploring their day-to-day interactions with this novel technology (see Hargreaves, Nye, & Burgess, Citation2010, Citation2013). The enrolment of participating households varied according to the type of IHD. For one, participants were recruited through housing associations. For the other two IHDs enrolment was through general advertising (e.g. newspaper advertisements) and via the UEA CRED initiative that encouraged individuals and groups to pledge to reduce their carbon footprint. The public participants were therefore self-selecting, although it could be argued that the device itself also played an important role in processes of enrolment. The overall process of enrolment within this case can be characterized as centralized and institutional. In this particular example it was the Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC) who were responsible for the highest tier of orchestration by setting a strong policy agenda around the rollout of smart meter technology in the UK, with the stated ambition of rolling out smart meters by 2020 to all UK households (DECC, Citation2009). Responding to this GEO (the technology developer) recruited a UEA research team to assist with the trial.

Hargreaves et al. (Citation2010, Citation2013) describe several other forms of resistance to the governmentality of the IHDs in the VET trial (see also Hargreaves, Citation2014). Whilst many participants did use the monitors to develop an understanding of their normal electricity consumption, and indeed some developed a ‘new’ normal, the monitors did not produce significant examples of behaviour change or reconfigurations of the materiality of household energy consumption. Indeed, one aspect of this resistance was that participants felt the monitors put an unfair onus on households to take responsibility for carbon reduction when compared to other social actors, what Marres (Citation2011) calls the ‘distribution’ of the problem. Whilst these forms of resistance did not challenge the stability of the VET collective they certainly challenged visions that the technology might function as a tool for behaviour change. This facet of resistance was also picked up by some elements of the media that reported the findings of the research (Poulter, Citation2011). Some of the technology also ‘resisted’ by refusing to perform as required, which delayed aspects of the trial, causing participants to drop out and hindering the flow of data.

The model of participation produced in this case is of household behaviour change via information visualization. IHDs can be conceptualized as a particular kind of participatory technology which turns everyday material activities into engagements with the environment (Marres, Citation2011). Marres (Citation2011) argues that devices such as smart meters materialize new forms of public participation by codifying participation by material means, and that by doing so participation is granted specific ‘logics’. In the case of smart meters one such dominant logic is that of ‘making things easy’, a logic that is prominent in both the development of domestic technology and in liberal political theory. This particular mode of participation therefore produces a public that requires specific assistance in order to participate; indeed the form that the assistance takes is in the provision of information, indicating how a second logic of smart meters is a tacit endorsement of information-deficit models of behaviour change (Hargreaves et al., Citation2010). The public are therefore framed as a particular form of consumer citizen, whereby a greater degree of ‘consumer engagement’ will shift the consumer from passive user to empowered and active part of the system (DECC, Citation2009, p. 19). Relatedly, the issue produced by this collective is the low carbon energy transition as essentially a technological problem in which individual responses are a necessary element of the response (DECC, Citation2009). This issue framing is not opened up at all. The solution to the development of a low carbon energy system is presented as a technologically optimistic vision of the future, both in terms of technologies of community and new information technologies—with the visions of householders being notable exclusions (Chilvers & Longhurst, Citation2012).

3.4. Dyfi Solar ClubFootnote5

The DSC emerged in Machynlleth in the mid-Welsh County of Powys in 1999. It is indicative of the type of community energy initiative that grew in popularity through the late 1990s and into the 2000s in the UK (Walker, Hunter, Devine-Wright, Evans, & Fay, Citation2007). The DSC was one of the five community-based renewable projects that the Dyfi Eco Valley Partnership was obliged to deliver under the contractual terms of a grant. The purpose of the DSC was to provide access to low cost solar water heating systems through a combination of negotiated discounts, subsidies, and self-installation.

The DSC was instigated by a project officer and its orchestration was a centralized process that involved the bringing together of a number of different elements. The original inspiration came from successful examples of solar clubs in Switzerland and the Centre for Sustainable Energy (CSE) in Bristol which launched the National Solar Clubs network began to train people to install commercial solar panels themselves. The DSC was an early member of this network and adopted the manual, contracts, and publicity material for the DSC. The orchestration of the collective also involved the enrolment of other social actors. A trainer was recruited from the Centre for Alternative Technology (CAT), originally established in Machynlleth in 1973 as a pioneer of Alternative Technology and which has continued to develop renewable technologies. Two local heating engineers were also recruited to undertake assessments and quality checks.

Enrolment of public participants was undertaken using established community development techniques such as structured public meetings and leaflets. The solar panels themselves also played an important mediating role. Their requirements, in terms of aspect, pitch, and area of roofing, determined whether some social actors were excluded or not from the collective. The individuals interested in the solar club tended to be middle class, some retired and often with background in engineering or being keen on DIY. Arguably those who lacked confidence or skills for self-installation were potentially excluded from the collective, although the DSC did develop a number of different installation ‘routes’ which could include installation by a professional engineer. A second dimension of exclusion was economic. Despite being subsidized by European funding, an initial home assessment visit cost £35 followed by a minimum membership fee of £50. The costs of the equipment were between £1,250 and £2,000 depending on the specific technology. Although this was cheaper than a straightforward commercial installation, and grants were also available, those on low incomes may have been unable to participate in the club.

External resistance towards the collective began to arise in 2003 when the Department of Trade and Industry and the International Solar Energy Association raised concerns about the product liability of the systems and who might be responsible for technical faults. Furthermore, there were issues surrounding health and safety concerns that many of the self-installs had not been done with the recommended safety equipment. By 2003 policy changes and cheaper market entrants meant that the cost-savings offered by solar clubs had been considerably undermined. The led to the demise of this particular model of participation, with the closure of many local clubs, as well as the national network.

The model of participation produced by the DSC was one of social or grassroots innovation, whereby the public were imagined as active, and technically competent. It also produced a notion of the public that would embody an ethic of mutual aid. The public were imagined as being susceptible to the influence of their peers and neighbours, a social psychological understanding of behaviour change (Nye, Whitmarsh, & Foxon, Citation2010). The assumption that publics would be predisposed towards solar technology was influenced by the fact that a ‘green milieu’ had built up in the area since the 1970s, rooted in the proximity of CAT. The issue being produced by the DSC related to the economic development potential of renewable energy, both in terms of building on and catalyzing the expertise already existing within the Dyfi valley, and in terms of providing green and cheaper energy in a geographical area where many households were ‘off grid’. Related to this was a vision to promote a distributed energy system. The project therefore sought to address the lack of visibility of solar thermal technology within the locality. DSC saw the development of a critical mass of demonstration households as a crucial step in normalizing the technology and consequently leading to the enrolment of further members.

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Participatory Co-productions

A summary comparison of the four cases in relation to the main analytical themes is presented in . All four cases attempted to be inclusive and open up engagement in UK low carbon energy transitions to actors from civil society. They achieved this to varying degrees. Importantly, however, our analysis highlights a continual tension between inclusion and exclusion in all four cases, which is endemic to any form of public engagement. Whilst claiming to be inclusive, the collectives formed in each case were all partially framed and subject to ‘overflows’ (Callon et al., Citation2009). They thus excluded certain actors, issue definitions, and visions of the future. For example, actor exclusions included: interest groups or protestors in DECC 2050, low-income groups and houses without the appropriate aspect in DSC, fossil fuel business interests in Climate Camp, and household types that did not meet the entry criteria in the VET. In some cases these exclusions were deliberate and purposive, in others they were the unintended consequence of orchestration.

Table 1. A comparative summary of each participatory collective in relation to the main analytical themes

A further commonality across all four cases is the central role of ‘technologies’ to mediating each collective of participation, organizing it, and configuring connections between actors. As shown in , these ‘technologies of engagement’ range from technologies as procedural formats, either in the form of highly standardized deliberative designs (DECC 2050) or consensual decision-making procedures (Climate Camp), as well as material objects such as digital visualization technologies (in the VET) and low carbon technologies (in DSC). In short, these engagements would not have happened without the work invested by human actors and material technologies in enrolling other actors and mediating the collective in an attempt to stabilize its configuration and definition of the issues at stake. For example, in the DECC 2050 Dialogue professional facilitators attempted to discipline participants to a particular deliberative model of participation and a technocentric definition of the issue at stake through workshop techniques linked to a website interface. Perhaps most striking is the Climate Camp case which, despite enacting a leaderless ‘horizontal-autonomous’ organizational philosophy, relied on consensual decision-making procedures to reach agreement on strategic commitments to the exclusion of other knowledges, framings, and perspectives within the collective.

Through these processes the stability of issue framings and visions of low carbon energy futures were achieved to varying degrees across the cases, but were also subject to challenges and forms of resistance. The two cases that were institutionally orchestrated by incumbent interests in government and industry (DECC 2050 and the VET) pre-imposed a technocentric issue framing or vision which was met with some internal resistance in each collective but not to the extent that it was opened up or transformed. The two cases where processes of enrolment were more citizen-led or ‘bottom-up’ (see ) produced visions of low carbon energy transitions that emphasized wider socio-political, as well as technical, dimensions. In the case of the DSC this framing was more stable throughout the life span of the collective, perhaps owning to the material attachments and mediating role of the solar technologies themselves. Out of all four cases the issue framing of Climate Camp was less stable and subject to transformations (closings and reopenings), due to the more distributed and organic processes of enrolment which enabled resistance by some actors within the collective to reorientate its strategic commitments. A crucial finding from the current analysis is that each of the four collectives represented in was subject to external challenges and also interacted with other competing collectives of participation.

In addition to issues, all four collectives shown in Table 4 produced models of participation, or democratic innovations, as well. In many respects the cases move beyond meanings of participation within the existing transitions literature, into private spaces of the household (in the VET) and the adversarial spaces of activist networks (in Climate Camp). Yet, all four bring into being particular models or normativities of participation which are highly varied, loosely reflecting Habermasian deliberative theory (DECC 2050), liberal political theory (VET), anarchist philosophy (Climate Camp), and communitarian principles (DSC). This is not insignificant as these philosophies, and the particular socio-technical configurations formed in each collective, offer differential potentials or constructions of ‘the public’ (see ). Both institutionally orchestrated processes (DECC 2050 and VET) brought forward constrained and passive models of the public, which closed down other public potentialities. While more exclusive in terms of actors represented, the two citizen-led collectives produced more ‘active’ publics, and a more overt politics of promise and possibility (Arendt, Citation2005), rather than only forms of resistance.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, we have brought literatures on socio-technical transitions into closer conversation with constructivist STS perspectives on participation as one way of addressing calls to better understand actor dynamics and the politics of transitions (Shove & Walker, Citation2007). Adopting this more relational approach has proved valuable in opening up the notion of participation in transitions, extending it beyond sites of deliberative fora (e.g. Einsiedel, Boyd, Medlock, & Ashworth, Citation2013; Hendriks, Citation2009) to multiple forms of public engagement across low carbon energy systems (Smith, Citation2012) including activism, grassroots innovation, and interactions with more mundane technologies in everyday life. An important advance of our approach has been to introduce a framework that allows the sort of symmetrical and comparative analysis across diverse cases of engagement that has not been evident in the sustainability transitions or participation literatures hitherto. More specifically, a key feature of the analysis is that rather than take ideas and normativities of participation and civil society as pre-given categories that can be mapped on or assessed in relation to socio-technical systems (cf. Smith, Citation2012), these forms of participation—as well as models of the public and definitions of the issues at stake—are viewed as being actively co-produced through the construction and mediation of collectives of participation (cf. Chilvers & Kearnes, Citation2016). We argue that understanding participation ‘in the making’ in this way is important for exploring the politics of transitions. As illustrated through our four cases, the contestation that occurs around the framing of issues, subjects and the way in which processes of participation exclude or are resisted are all instances of energy system politics.

As noted earlier, existing analyses of participation in transitions have found transitions management arrangements to be overly technocratic and exclusive (Hendriks, Citation2008; Lawhon & Murphy, Citation2011) whereas so-called ‘bottom-up’ or grassroots processes are more closely associated with the social shaping of innovation in line with the needs of the communities (Seyfang & Smith, Citation2007). While there are no doubt differences along these lines, our analysis is particularly revealing in highlighting commonalities and complexities across all cases, which upset and question a simplistic technocratic/democratic binary. All four of our cases were mediated and orchestrated through work invested by human actors and technologies of engagement, thus being subject to significant exclusions. These dynamics apply just as much to what might be considered organic ‘bottom-up’ processes (Climate Camp, DSC) compared to the two institutionally orchestrated ones (DECC 2050, VET). Furthermore, in all four cases we have seen how models of participation, of publics, and definitions of the issues or visions of low carbon energy futures are actively constructed at particular sites through these processes of mediation. These productive dimensions are not inevitable, however, and are the outcome of struggles and forms of resistance which were again evident in all cases but to varying degrees, highlighting the politics of participation in energy transitions. Rather than only judging collectives of participation in transition(s) against pre-given categories or normative principles our findings suggest that future analyses should focus on the relationship between the way in which collectives of participation are configured and the political openings/closings that occur (with respect to models, publics, and objects of participation; cf. Barry, Citation2001; Chilvers & Kearnes, Citation2016; Stirling, Citation2008).

Our analysis therefore has implications beyond the level of individual cases of participation and interventions in system change which has been the dominant scale of analysis in studies of participation in both STS and the transitions literature to date. Through a multi-case approach, which attends to diversity in forms of enrolment and the objects of participation, we have developed a perspective that emphasizes the shear multiplicity of collectives of participation—in the cases we have analysed and many others that are similar or different to them—which coexist ‘in’ any one socio-technical system or issue space. To this end we can begin to conceive of wider ‘ecologies of participation’ comprising of diverse participatory collectives which are themselves entangled, interrelated and mutually co-productive (Chilvers, Citation2010a, Chilvers & Kearnes, Citation2016). In beginning to build this perspective in the context of UK low carbon energy systems, our analysis illustrates how all of the diverse collectives of participation across socio-technical systems have effects in relation to these systems. This includes negotiated visions and potential material commitments which play a role in shaping future energy pathways, as well as producing varying modes of participation or ‘democratic innovations’ (Smith, Citation2009) in transitions. While some may consider our four case studies to be insignificant in relation to the ‘driving forces’ of the UK energy system, this would be to dismiss the alternative voices, resistances, commitments, and possibilities that they bring into being, and the cumulative effects of multiple forms of engagement that are seeming mundane but numerous and widespread. What we can conclusively say from our findings, however, is that forms of participation and democratic engagement are co-produced in mutual interaction with the evolution of socio-technical (energy) systems, rather than existing as separate procedures or tools that are somehow ‘bolted on’ or integrated in. We therefore contribute to a growing body of work that argues for a ‘post-foundational’ perspective on the democratic potential of TM (Jhagroe & Loorbach, Citation2014).

Whilst we have focused in this paper on public participation in transitions, the approach that we have outlined could be applied to any form of collective that is engaged in system change. As such it offers another perspective to the growing body of literature which is focused on explaining transition actor dynamics (Farla, Markard, Raven, & Coenen, Citation2012), which leads us to make some final statements reflecting on the implications of our analysis for more interventionist ambitions in the sustainability transitions field. Where the interest lies in doing—in designing or catalyzing new forms of participation and spaces of intervention in system change, whether that be transitions management platforms, grassroots innovations, or any other form of societal engagement in transitions—our findings suggest the need for actors involved to be reflexively aware of the partialities and exclusions of these collectives with respect to framing effects and ‘overflows’, constructions of publics, and the models of participation enacted. Interventionist approaches also encompass attempts at knowing the system to inform ‘reflexive governance’ strategies and attempts to steer system change (Voß, Bauknecht, & Kemp, Citation2006). The cases analysed illustrate the inherent uncertainty and indeterminacy of participation and the public, which is not sufficiently acknowledged in existing practice. Attempts at speaking for or representing any one collective of participation should be accompanied by at least some effort to account for the partiality of framings involved and significant exclusions in terms of actors, visions, and so on.

Yet, these complexities of intervening in knowings and doings that shape socio-technical change multiply when considering system-wide ‘ecologies of participation’. Here our analysis suggests that attempts to understand participation and the public in low carbon energy (or other socio-technical) transitions through seemingly ‘comprehensive’ opinion surveys and deliberative techniques, can never be enough on their own. Our findings suggest the need for mapping complex patternings of diverse collectives of participation as they exist in situ across the system as part of any attempt to generate ‘social intelligence’ for reflexive governance of system change. This presents future methodological challenges for devising ways of mapping across diverse collectives of participation in governing system change (see also Chilvers, Citation2010b; Marres, Citation2012). Perhaps more crucial, however, is the need to build the reflexive capacities of actors, institutions, and distributed systems in sustainability transitions to attend to the uncertainties, indeterminacies, and politics of participation and the public outlined in this paper (cf. Chilvers, Citation2013; Smith & Stirling, Citation2007; Stirling, Citation2006). Yet, it is both the analytical and interventionist implications we have considered in conclusion that are important for moving towards more deliberately reflexive governance for sustainability and attending to the politics of socio-technical transitions, at least when it comes to participation and ‘the public’.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the workshop attendees for making it a stimulating and engaging event, with special thanks to those who prepared case studies for discussion. Any errors remain the responsibility of the authors.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The workshop formed part of the Transition Pathways to a Low Carbon Economy project, a 4-year interdisciplinary research consortium involving nine UK universities—co-funded by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and E.ON—which sought to develop and evaluate UK low carbon energy transition pathways to 2050.

2. The four case studies analysed in this paper were presented, discussed, and collectively analysed by participants in discussion groups within the workshop process. Two of the cases (VET and DSC) were presented and represented by workshop participants who had been actively involved in studying them. The two other cases (DECC 2050 and the CCA) were presented by participants who had not studied them directly but either had direct experience of them or drew on source material in the public domain. Following the workshop further documentary evidence was collated for all four cases and subject to qualitative coding analysis based on the two main analytical themes focused on in this paper. Reference to all source material is given in the analysis of each case in the following section.

3. Sciencewise-ERC is funded by the Department for Business Innovation and Skills (BIS) and is intended to facilitate public dialogue processes in order to inform policy decisions around science and technology. See Sciencewise-ERC (undated) for the principles that the DECC2050 process followed.

4. This dialogue did lead to further engagement between trade unions and climate camp activists (Schlembach, Citation2011: 203).

5. This case draws extensively on an ‘innovation history’ of the DSC. See Hargreaves (Citation2012).

References

- Arendt, H. (2005). The promise of politics. New York, NY: Schocken.

- Barry, A. (2001). Political machines: Governing a technological society. London: Althone Press.

- Braun, K., & Schultz, S. (2010). … a certain amount of engineering involved’: Constructing the public in participatory governance arrangements. Public Understanding of Science, 19(4), 403–419. doi: 10.1177/0963662509347814

- Butler, C., Parkhill, K. A., & Pidgeon, N. (2013). Deliberating energy transitions in the UK—Transforming the UK energy system: Public values, attitudes and acceptability. London: UKERC.

- Callon, M., Lascoumes, P., & Barthe, Y. (2009). Acting in an uncertain world: An essay on technical democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Chilvers, J. (2009). Deliberative and participatory approaches in environmental geography. In N. Castree, D. Demeritt, D. Liverman, & B. Rhoads (Eds.), A Companion to environmental geography (pp. 400–417). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Chilvers, J. (Ed.). (2010a). Participation, power and sustainable energy futures. A report of the ESRC critical public engagement seminar, 26 October 2010, University of Sussex (University of East Anglia, Norwich).

- Chilvers, J. (2010b). Sustainable participation? Mapping out and reflecting on the field of public dialogue on science and technology. Harwell: Sciencewise Expert Resource Centre.

- Chilvers, J. (2013). Reflexive engagement? Actors, learning, and reflexivity in public dialogue on science and technology. Science Communication, 35(3), 283–310. doi: 10.1177/1075547012454598

- Chilvers, J., & Burgess, J. (2008). Power relations: The politics of risk and procedure in nuclear waste governance. Environment and Planning A, 40(8), 1881–1900. doi: 10.1068/a40334

- Chilvers, J., & Kearnes, M. (Eds.). (2016). Remaking participation: Science, environment and emergent publics. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Chilvers, J., & Longhurst, N. (2012). Participation, politics and actor dynamics in low carbon energy transitions. Norwich: Science, Society and Sustainability Research Group, University of East Anglia.

- Comber, N., & Sheikh, S. (2011). Evaluation and learning from the 2050 public engagement programme. London: Office for Public Management.

- DECC. (2009). Smarter grids: The opportunity. Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC), HM Government. London.

- Dryzek, J. S. (1990). Discursive democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Einsiedel, E., Boyd, A., Medlock, J., & Ashworth, P. (2013). Assessing socio-technical mindsets: Public deliberations on carbon capture in the context of energy sources and climate change. Energy Policy, 53, 149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2012.10.042

- Farla, J., Markard, J., Raven, R., & Coenen, L. (2012). Sustainability transitions in the making: A closer look at actors, strategies and resources. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79, 991–998. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2012.02.001

- Felt, U., & Fochler, M. (2010). Machineries for making publics: Inscribing and de-scribing publics in public engagement. Minerva, 48(3), 219–238. doi: 10.1007/s11024-010-9155-x

- Felt, U., & Wynne, B. (2007). Taking European knowledge society seriously. Brussels: European Commission.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making social science matter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Foxon, T. (2013). Transition pathways for a low carbon electricity system. Energy Policy, 52, 10–24. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2012.04.001

- Geels, F. W., & Schot, J. (2007). A typology of transition pathways. Research Policy, 36(3), 399–417. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003

- Grin, J., Rotmans, J., & Schot, J. (2010). Conclusion: How to understand transitions? How to influence them? Synthesis and lessons for further research. In J. Grin, J. Rotmans, & J. Schot (Eds.), Transitions to sustainable development (pp. 320–344). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Habermas, J. (1984). Theory of communicative action—volume 1: Reason and the rationalization of society. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Hammond, G. P., & Pearson, P. (2013). Challenges of the transition to a low carbon, more electric future: From here to 2050. Energy Policy, 52, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2012.10.052

- Hargreaves, T. (2012). Dyfi solar club: An innovation history. Norwich: Science, Society and Sustainability Research Group, University of East Anglia.

- Hargreaves, T. (2014). Smart meters and the governance of energy use in the household. In J. Stripple & H. Bulkeley (Eds.), Governing the climate: New approaches to rationality, power and politics. (pp. 127–142) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hargreaves, T., Nye, M., & Burgess, J. (2010). Making energy visible: A qualitative field study of how householders interact with feedback from smart energy monitors. Energy Policy, 38, 6111–6119. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2010.05.068

- Hargreaves, T., Nye, M., & Burgess, J. (2013). Keeping energy visible? Exploring how householders interact with feedback from smart energy monitors in the longer term. Energy Policy, 52, 126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2012.03.027

- Hendriks, C. (2008). On inclusion and network governance: The democratic disconnect of Dutch energy transitions. Public Administration, 86(4), 1009–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.00738.x

- Hendriks, C. (2009). Policy design without democracy? Making democratic sense of transition management. Policy Sciences, 42, 341–368. doi: 10.1007/s11077-009-9095-1

- Hendriks, C., & Grin, J. (2007). Contextualising reflexive governance: The politics of Dutch transitions to sustainability. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 9(3/4), 333–350. doi: 10.1080/15239080701622790

- HM Government. (2009). The UK low carbon transition plan. Norwich: The Stationary Office.

- Hoogma, R., Kemp, R., Schot, J., & Truffer, B. (2002). Experimenting for sustainable transport. London: Spon Press.

- Ipsos-MORI. (2011). Findings from the DECC 2050 deliberative dialogues. http://www.sciencewise-erc.org.uk/cms/assets/Uploads/Project-files/Findings-from-DECC-2050-Deliberative-Dialogues.pdf

- Irwin, A. (2006). The politics of talk: Coming to terms with the ‘new’ scientific governance. Social Studies of Science, 36(2), 299–320. doi: 10.1177/0306312706053350

- Irwin, A., & Michael, M. (2003). Science, social theory and public knowledge. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Jasanoff, S. (Ed.). (2004). States of Knowledge: The co-production of science and social order. London: Routledge.

- Jhagroe, S., & Loorbach, D. (2014). See no evil, hear no evil: The democratic potential of transition management. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 15, 65–83. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2014.07.001

- Kemp, R., Schot, J., & Hoogma, R. (1998). Regime shifts to sustainability through processes of Niche formation: The approach of strategic Niche management. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 10(2), 175–198. doi: 10.1080/09537329808524310

- Laurent, B. (2011). Technologies of democracy: Experiments and demonstrations. Science and Engineering Ethics, 17(4), 649–666. doi: 10.1007/s11948-011-9303-1

- Lawhon, M., & Murphy, J. T. (2011). Socio-technical regimes and sustainability transitions: Insights from political ecology. Progress in Human Geography, 36(3), 354–378. doi: 10.1177/0309132511427960

- Lezaun, J. (2007). A market of opinions: The political epistemology of focus groups. In M. Callon, Y. Millo, & F. Munesia (Eds.), Market devices (pp. 130–151). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lezaun, J., & Soneryd, L. (2007). Consulting citizens: Technologies of elicitation and the mobility of publics. Public Understanding of Science, 16(3), 279–297. doi: 10.1177/0963662507079371

- Loorbach, D. (2010). Transition management for sustainable development: A prescriptive, complexity-based governance framework. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions, 23(1), 161–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01471.x

- Markard, J., Raven, R., & Truffer, B. (2012). Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Research Policy, 41, 955–967. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.013

- Markard, J., & Truffer, B. (2008). Technological innovation systems and the multi-level perspective: Towards and integrated framework. Research Policy, 37, 596–615. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2008.01.004

- Marres, N. (2007). The issues deserve more credit: Pragmatist contributions to the study of public involvement in controversy. Social Studies of Science, 37(5), 759–780. doi: 10.1177/0306312706077367

- Marres, N. (2011). The cost of public involvement: Everyday devices of carbon accounting and the materialization of participation. Economy and Society, 40(5), 510–533. doi: 10.1080/03085147.2011.602294

- Marres, N. (2012). Material participation: Technology, the environment and everyday publics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Marres, N., & Lezaun, J. (2011). Materials and devices of the public: An introduction. Economy and Society, 40(4), 489–509. doi: 10.1080/03085147.2011.602293

- Meadowcroft, J. (2007). Who is in charge here? Governance for sustainable developing in a complex world. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 9(3–4), 299–314. doi: 10.1080/15239080701631544

- Michael, M. (2009). Publics performing publics: of PiGs, PiPs and politics. Public Understanding of Science, 18(5), 617–631. doi: 10.1177/0963662508098581

- Nye, M., Whitmarsh, L., & Foxon, T. (2010). Socio-psychological perspectives on the active roles of domestic actors in transition to a lower carbon electricity economy. Environment and Planning A, 42(3), 697–714. doi: 10.1068/a4245

- Pallett, H., & Chilvers, J. (2013). A decade of learning about publics, participation, and climate change: Institutionalising reflexivity. Environment and Planning A, 45(5), 1162–1183. doi: 10.1068/a45252

- Plows, A. (2008). Towards an analysis of the ‘success’ of UK green protests. British Politics, 3(1), 92–109. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.bp.4200081

- Poulter, S. (2011, September 2). How smart meters costing £11.3bn are an expensive flop that trigger family rows. Daily Mail.

- Renn, O., Webler, T., & Wiedemann, P. (Eds.). (1995). Fairness and competence in citizen participation: Evaluating models for environmental discourse. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Rip, A., & Kemp, R. (1998). Technological change. In S. Rayner & E. L. Malone (Eds.), Human choices and climate change (pp. 327–399). Columbus, OH: Battelle Press.

- Rotmans, J., & Loorbach, D. (2010). Towards a better understanding of Transitions and their governance: A systemic and reflexive approach. In J. Grin, J Rotman, & J Schot (Eds.), Transitions to sustainable development (pp. 105–220). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Rowe, G., & Frewer, L. (2000). Public participation methods: A framework for evaluation. Science Technology, & Human Values, 25(1), 3–29. doi: 10.1177/016224390002500101

- Saunders, C. (2012). Reformism and radicalism in the climate camp in Britain: Benign coexistence, tensions and prospects for bridging. Environmental Politics, 21(5), 829–846. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2012.692937

- Saunders, C., & Price, S. (2009). One person's eu-topia, another's hell: Climate camp as a heterotopia. Environmental Politics, 18(1), 117–122. doi: 10.1080/09644010802624850

- Schlembach, R. (2011). How do radical climate movements negotiate their environmental and their social agendas? A study of debates within the camp for climate action (UK). Critical Social Policy, 31, 194–215. doi: 10.1177/0261018310395922

- Schlembach, R., Lear, B., & Bowman, A. (2012). Science and ethics in the post-political era: Strategies within the camp for climate action. Environmental Politics, 21(5), 811–828. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2012.692938

- Sciencewise-ERC, n.d. The government's approach to public dialogue on science and technology. Retrieved May 24, 2013, from http://www.sciencewise-erc.org.uk/cms/assets/Uploads/Project-files/Sciencewise-ERC-Guiding-Principles.pdf

- Seyfang, G., & Smith, A. (2007). Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environmental Politics, 16(4), 584–603. doi: 10.1080/09644010701419121

- Shove, E. (2012). Energy transitions in practice: The case of global indoor climate change. In G. Verbong & D. Loorbach (Eds.), Governing the energy transition: Reality, illusion or necessity? (pp. 51–74). London: Routledge.

- Shove, E., & Pantzar, M. (2005). Consumers, producers and practices: Understanding the invention and reinvention of Nordic walking. Journal of Consumer Culture 5(1), 43–64. doi: 10.1177/1469540505049846

- Shove, E., & Walker, G. (2007). CAUTION! Transitions ahead: Politics, practice and sustainable transition management. Environment and Planning A, 39(4), 763–770. doi: 10.1068/a39310

- Smith, G. (2009). Democratic innovations: Designing institutions for citizen participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, A. (2012). Civil society in sustainable energy transitions. In G. Verbong & D. Loorbach (Eds.), Governing the energy transition: Reality, illusion or necessity? (pp. 180–202). London: Routledge.

- Smith, A., & Stirling, A. (2007). Moving outside or inside? Objectification and reflexivity in the governance of socio-technical systems. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 9(3–4), 351–373. doi: 10.1080/15239080701622873