ABSTRACT

This paper investigates where and how sustainable transport goals are translated into public transport planning and operations. The case where this is explored is the Regional Public Transport Authority (RPTA) in Stockholm, Sweden. By drawing upon recent discussions on policy translation and political–administrative relationships, sustainable transport is found to be translated in two different collaborative spaces in the RTPA. In the market side of the authority, which is mainly preoccupied with procurement of traffic and compliance issues, sustainable transport is translated into quantitative goals (including biofuels, emissions, noise, etc.) and mechanically reproduced from the politicians via the civil servants to the private operators. In the planning side of the authority, sustainability measurements have been hard to quantify and the challenge to integrate land-use and transport planning is resolved in an organic manner, in specific projects, between the strategic transport planners in the RPTA and the land-use planners in the municipalities, at a distance from the politicians’ involvement. Throughout the RPTA, sustainable transport has broadened to also include social sustainability, although this has been difficult to translate into quantitative measurements, which is the desired mode of governance by the politicians.

Introduction

During the last three decades, sustainability has emerged as an overarching societal goal across the globe, crossing different sectors and policy fields. Transport stands out as one of the policy fields that perhaps face the greatest challenges. According to IPCC, transport is responsible for roughly 23% of total energy-related CO2 emissions (Sims et al., Citation2014, p. 603). Despite more efficient vehicles and new mitigation policies being implemented during the past decades, the level of greenhouse gas emissions from transport has continued to grow globally.

Public transport plays an important role in lowering the transport sector’s levels of CO2 emissions and increasing its energy efficiency (Sims et al., Citation2014). To reduce greenhouse gas emissions from passenger and freight transport, IPCC presents four main mitigation strategies that policy-makers could pursue: (1) avoiding journeys where possible, (2) a modal shift to lower carbon transport systems, (3) lowering energy intensity and (4) reducing carbon intensity of fuels (Sims et al., Citation2014, p. 603). Public transport is mainly concerned with realizing the second strategy, i.e. increasing its market share of total motorized transport. But the third and fourth strategies are also of relevance as non-renewable fuels are increasingly being substituted by renewable ones in public transport, and as newer vehicles replace older, their energy efficiency increases.

Public transport is comparatively more sustainable than other modes of motorized transport (Banister, Citation2008; Sims et al., Citation2014). Yet, public transport authorities across Europe are increasingly being expected to respond to the global ambitions of transforming their activities and operations so that they become sustainable in and of themselves. But how do they respond to this challenge and where is sustainability translated into their activities and operations? This paper seeks to probe the question how and where sustainability is translated in the context of public transport by studying the relationships between politicians and civil servants in the Regional Public Transport Authority (RPTA) in Stockholm, Sweden.

Sustainability is perhaps one of the most used and misused concepts in political and corporate discourse (Farley & Smith, Citation2013; Redclift, Citation2005), plagued as it is by a myriad of indicators and incommensurable metrics (e.g. Lyytimäki, Tapio, Varho, & Söderman, Citation2013). Critical research on sustainability has, moreover, suggested that sustainability has undergone so much mainstreaming that it virtually has become depoliticized. Since hardly any group would oppose the idea that the survival of humankind and the planet is vital, this makes sustainability an empty signifier, whose meaning is so ambiguous that it may be used to mean anything (Avelino, Grin, Pel, & Jhagroe, Citation2016; Kenis & Lievens, Citation2014; Kenis, Bono, & Mathijs, Citation2016; Swyngedouw, Citation2010). Moreover, studies have found that, when global sustainability policies are translated and subsequently operationalized into national policies and organizational practices, they tend to collide with local knowledge and institutionalized routines, leading to the emergence of trade-offs and thereby exhibiting its political implications (Temenos & Mccann, Citation2012; Uittenbroek, Citation2016).

Previous studies on collaboration in the governance of sustainability have predominantly focused either on horizontal relationships between different stakeholders or governmental entities (e.g. Hull, Citation2008; Lafferty & Hovden, Citation2003), or on vertical relationships between different levels in multi-governance structures (e.g. Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2005; Newig & Fritsch, Citation2009). But little has been done when it comes to empirically investigating the governance structures and collaborative efforts between politicians and civil servants in the context of translating the concept of sustainability (see e.g. Lange, Driessen, Sauer, Bornemann, & Burger, Citation2013; Meadowcroft, Citation2007). This paper intends to fill this gap by investigating how collaborative spaces shape the interpretation and definition – that is, the translation – of the concept.

Interpretative policy analysis has questioned the idea that policies and planning concepts are ‘transferred’ from one context to another (Dobbin, Simmons, & Garrett, Citation2007; Dwyer & Ellison, Citation2009; Stone, Citation2012). By studying translation both as a social process and as assemblages, interpretative policy analysis has developed and sensitized the understanding of both policy transfer and implementation (Yanow, Citation2007; Clarke, Bainton, Lendvai, & Stubbs, Citation2015). Some of these works draw inspiration from Callon’s (Citation1986) seminal study that sparked the study of the sociology of translation, to which I will return in a moment. Even though the translation of sustainability and transport policies has been studied before (e.g. Boussauw & Vanoutrive, Citation2017; Lagendijk & Boertjes, Citation2013; Montero, Citation2017), the collaborative spaces in which translations occur have, as mentioned earlier, only received little attention. By connecting the literature on political–administrative relationships (Overeem, Citation2005; Svara, Citation2006a, Citation2006b) with the one on policy and planning translation (Clarke et al., Citation2015; Healey, Citation2012; Healey, Citation2013; McCann & Ward, Citation2011), this study will contribute with new knowledge on how sustainability is translated in the political–administrative nexus in the context of public transport.

The outline is as follows. I begin by describing the methodology used to collect the empirical material and continue by reviewing the theoretical debates and by defining the key concepts needed to analyse the material. Then, I proceed to describe the background and context. This is followed by narrative accounts of civil servants, who describe their relationships with the political level in the County Council of Stockholm, as well as their collaborations with the procured traffic operators and the local planners in the municipalities. Finally, the conclusion and results are presented.

Methodology

The question guiding this paper is explored through a unique case study: The RPTA in Stockholm. Stockholm is often seen as a successful case in both public transport and environmental policies. Its metro system has been heralded as a good example of how to integrate public transport and land-use planning (e.g. Cervero, Citation1998). In 2010, Stockholm was also the first city to be entitled the Green Capital of Europe, an annual award granted by the European Commission’s DG Environment (European Commission, DG Env, Citation2017). While recognizing that success and failure are far from neutral labels, constructed as they are in political-cum-ideological processes (McCann & Ward, Citation2015; Peck, Citation2011), Stockholm was here chosen not because it has been labelled a successful case per se, but because this labelling enables an investigation of how and where sustainability – being understood as an empty signifier – has been translated.

This case study is built upon interviews and public documents. Six in-depth interviews were taped and transcribed during late 2015 and early 2016. Patterns and recurring themes were identified and further analysed. The interviewees worked predominantly in the Department of Strategic Development in the RPTA. Two of the interviewees worked as managers in the department and had comparatively closer contact with the politicians than the rest of the strategic planners. As the staff in the Department of Strategic Development were strategically located within the organization, they also had a broad overview of the entire organization, which ensured reliable interview material.

Besides ‘following the people’ and understanding how they make sense of and translate sustainability, I have also been ‘following the materials’, and so traced how sustainability has been translated in key documents (Wood, Citation2015b). Public documents, including decision-making protocols and sustainability strategies, were also collected and analysed. The documents covered a period of approximately 10 years, stretching from the first sustainability strategy in 2004 to the Global Compact Communication on Progress Rapport in 2014. This allowed me to gain insights into the relationships between the politicians and the civil servants as well as insights into how the translation of sustainability has changed over the years. Following the purpose of the paper, the questions guiding the analysis of the empirical material were twofold: first, how has sustainability been translated from 2004 and onwards and, second, where, in which collaborative spaces, have these translations occurred?

Theorizing the collaborative spaces of policy translation

The theoretical discussion builds on the rich debates about the political–administrative relationship, as it has been discussed over the past 10 years. Policy translation is here understood as taking place in the collaborative spaces where politicians and civil servants meet, exchange documents and work together. The theoretical contribution of this paper lies in the connection between the research on the political–administrative relationship and its potential synergies with policy translation studies.

The political–administrative relationship

The political–administrative relationship is a classical topic of discussion that resurfaces time and time again. It received a renewed interest in the mid-2000s when Svara (Citation2006a) suggested that politicians and civil servants are interdependent and mutually influence each other. By arguing that complementarity captures the nature of political–administrative relationships, Svara (Citation2006a, Citation2006b) supplanted the traditional view, in which the relationships between politicians and administrators are marked by separate and dichotomous roles. Overeem (Citation2005, Citation2006) has argued that most contemporary scholars deem the dichotomy to be outdated, as it appears inappropriate for understanding the current configurations of the politics–administration continuum. While doing so, however, they blur the boundary surrounding politics, he contends. This increases the risk of losing sight of the point where civil servants are drawn into partisan politics. Reflecting on the same topic, Aberbach and Rockman (Citation2006) have argued that the increased influence of experts and civil servants in policy-making has become more common since the 1980s, but also heavily criticized. Rather than overlapping roles, civil servants have continued to bring facts and expertise to the policy-making process, while politicians still tend to absorb values and represent interests in society.

This very much echoes Wildavsky’s (Citation1979) frequently quoted idea that civil servants, who work with policy development and implementation, should ‘speak truth to power’. But the ability for planners to engage in and mobilize fearless speech, or parrhesia, has become more limited. Grange (Citation2017) has recently argued, for example, that Swedish local planners have become under pressure to conform and be loyal to current neoliberal politics. Lack of critical discussions and expressions of resistance have also been reported in other local government contexts (e.g. Paulsson, Citation2014). Although the relationships between politicians and civil servants continue to be marked by the institutionalized expectations on their respective roles, civil servants are increasingly being pressured to align with political ideas and ideals that go counter to their professional ethos (Grange, Citation2017). Opposed to this is the trend where ‘inside activists’, i.e. politically enlightened civil servants advocate and implement policies in the fields of sustainability and human rights (Briscoe & Gupta, Citation2016; Hysing & Olsson, Citation2011; Olsson, Citation2009; Olsson & Hysing, Citation2012).

Moving beyond the relationships between politicians and civil servants, there is a substantial literature on the role and function of the latter group. Civil servants can serve many roles and functions. He or she can either be a tool for the politician, or an ombudsman for the citizen or client. A third role is the role of the civil servant as a power broker, who takes part in shaping policies and decision-making processes. A fourth role is the knowledge-expert who builds society (Lundquist, Citation1998). Drawing upon the rich literature in planning studies (e.g. Healey, Citation2010), I suggest that collaboration is an appropriate concept to describe the multifaceted character of contemporary political–administrative relationships.

Collaboration has been proposed as a solution to the problems associated with the lack of democratic influence on urban developments (Healey, Citation2010) or as a device for public sector organizations to harnessing the private sector’s capital, knowledge and skills (Emerson, Nabatchi, & Balogh, Citation2012). Collaboration, moreover, suggests that the silo-mentality often attributed to public sector bureaucracies comes with a host of problems and challenges related to capacity building. Yet, collaboration is also a time-consuming process and as an official policy, it risks adding a new layer of bureaucracy on to public sector organizations (Pell, Citation2016).

Here, collaboration is primarily understood as a space where relationships between politicians and civil servants evolve over time. A collaborative space is, thus, a space under continuous renegotiation, as well as a space that contributes to reproducing or producing new configurations of prevailing power and governance structures. Understanding the collaborative spaces in which translations occur is vital for understanding both how and where key concepts, in this case sustainability, are interpreted and defined in the translation process (Clarke et al., Citation2015; Healey, Citation2013).

The translation of policy

The debates about political–administrative relationships have many interesting insights to offer, but it is the intricate relationships between politicians and civil servants, or more precisely, the collaborative spaces where they meet and translate the concept of sustainability, that is of interest here.

Translation is here understood as the process in which a concept travels from one context to another (Clarke et al., Citation2015). It is neither an outcome that is inferior to an authentic or original meaning, nor entirely wrong or right, but a process where the outcome is to a varying degree meaningful (Freeman, Citation2009). Should the translation be as literal as possible, or should the task of the translator be to transfer the meaning of a body of text or a concept to a new audience are questions that have been debated for ages and different normative theories give different answers (see Buden, Nowotny, Simon, Bery, & Cronin, Citation2009). Yet, both approaches agree that meanings sometimes get ‘lost in translation’, e.g. when the translation process is too literal, or involves too much editing or deletion (Freeman, Citation2009). Translation should therefore be understood as a process placed both within and beyond language, imbued as it is with the taken-for-granted assumptions that give concepts and phenomenon meaning in a cohesive culture (Temple, Citation1997).

To understand why certain translations gain legitimacy while others do not, I want to return to Callon (Citation1986) and his much-discussed study on the sociology of translation. He suggests that experts, professionals and laymen are ‘locked into place’ once the key issue for all involved actors has been established. These actors, then, gather support for their interpretation of the foreign practices and of the imported concepts from such diverse groups as consumers, other experts and scientific communities, as well as from colleagues and people in the industry. Based on this, the actors portray themselves as spokespersons for larger communities of people and thereby seek to gain legitimacy for their translation. Even though Callon does not employ the concept of a collaborative space, his study nonetheless vindicates the usefulness of this concept, as it provides a basic framework for understanding how translation processes are spaces imbued with negotiations, which are ultimately shaped by power relations.

In both policy (Clarke et al., Citation2015) and planning studies (Cook & Ward, Citation2012; Healey, Citation2012; Healey, Citation2013; Roy, Citation2011), investigations of translations as socio-technical processes have propagated recently. Rather than emphasizing the straightforward transfer or diffusion of policies, as they move from one context to another, Murray (Citation2017, p. 152) has suggested, following Healey (Citation2012, Citation2013), that ‘it is more instructive to emphasize the translation (i.e. open to multiple interpretations) of these “travelling ideas” that assume hybrid “lives of their own” as they mutate and evolve under place-specific circumstances’. Although this interpretative approach enables a historical and contextual sensitization of the processes in which policy concepts and ideas are translated, I would add that these processes largely occur in, what I have termed, collaborative spaces.

In view of the purpose of the paper and the theoretical discussion above, I continue with a brief background on the governance of public transport in Stockholm, Sweden, which is followed by an analysis of how sustainability has been translated there from 2004 and onwards, as well as where, in which collaborative spaces, these translations have occurred and how these spaces have shaped the translation processes.

The governance of public transport in Stockholm, Sweden

The RPTA in Stockholm has seven organizational units. These units are clustered into two groups, each representing two spaces of public transport: the market space and the planning space. Whereas the market space is preoccupied with customer satisfaction as well as contract management and compliance, the planning space is preoccupied with long-term planning, strategic development as well as complying with policies, rules and laws. As will be explicated in the following chapters, these two sides not only have diverse and dissimilar informal relationships with the political level of the organization, they also translate sustainability differently. This, I argue, is due to the two different collaborative spaces where the concept is translated.

The market space of public transport: sustainability and the procurement of traffic

As in the rest of Europe, public transport in Stockholm has undergone several reforms that have involved the introduction of market mechanisms. Although no traffic is operated in-house anymore, the influence and the political control over operations have not diminished. By setting targets and deciding on larger investments and procurement contracts, politicians still exert influence and decide the strategic direction of public transport.

Environmental requirements and targets decided by politicians

The first comprehensive environmental policy was adopted by SL’s politically instituted board only four days before Christmas Eve in 2004. It included goals on reducing the use of fossil fuels; reducing emissions of pollutants into the air; increasing the share of renewable resource; lowering the level of noise caused by its traffic; and so on. The environmental policy was originally developed by the staff working with environmental impact, but then re-examined by the politicians every two years and revised if necessary. In 2008, the environmental policy was transferred into a new template, while the content remained untouched compared to the previous version.

For the civil servants working on the so-called market side of the organization, translation was largely about developing environmental requirements to be used when procuring new traffic. When the fourth generation of the environmental policy was presented in April 2009, it included updates both in the policy itself and in the underlying principles, which then were to be translated by the civil servants into the new contracts that were to be developed (SLL, Citation2013a, Citation2013b). Due to SL being by far the largest procurer of public transport in the entire country, SL has been able to dictate the terms of the procurement contracts without meeting much explicit resistance (Bergström & Khan, Citation2007, p. 18). Although the RPTA no longer produced these services in-house, they ensured that the operators fulfilled the environmental requirements as specified in the procurement contracts, including the requirement to comply with ISO 14001: 2004, by closely monitoring and controlling their performance. This led the then CEO to proclaim that SL was Stockholm’s largest ‘environmental movement’ (SL, Citation2009, p. 3).

In 2011, SL met or even surpassed the environmental requirements decided by the politicians in the County Council for the period 2007–2011. For example, the goal of having at least 50% of the buses powered by renewable fuels turned out to be 58%.Footnote1 Another goal was to reduce nitrogen oxide emissions from the buses by 15%, but the outcome was 22%. A third goal was to reduce emissions of pollution particles from the buses by 25%, but in practice, it was reduced by 46% (SL Press release, Citation2012).

The same year, a new environmental policy for the entire Stockholm County Council was presented for the period 2012–2016 (SLL, Citation2011a). Civil servants from SL went through the proposal and devoted special attention to the parts that touched SL’s operations and business model. The interim target of 75% renewable fuel in transport was considered to have the greatest impact on SL’s operations. Raising the target from 50% to 75% would result in additional costs of about 15 million/year, which was considered both feasible and economically reasonable by the politicians in the County Council (SLL, Citation2011b).

Emerging here is the prevalence of quantitative measurements to manage public transport performance and evaluate its environmental impact. This is also reflected in the collaborative spaces where politicians and civil servants meet to exchange ideas and documents, but also where they decide on how sustainability should be translated. The more market mechanisms introduced, the broader the definition of sustainability. One example of this is how sustainability was broadened to include social aspects.

The emergence of social sustainability

SL signed UN’s Global Compact in 2009. Global Compact contains guidelines and requirements for companies wanting to take social and environmental responsibility for achieving sustainable development. Global Compact includes principles regarding human rights, labour, environment and corruption (SLL, Citation2015). In addition to Global Compact, SL had to comply with the County Council’s endorsement and interpretation of UN’s Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and contribute to the County Council’s goal of achieving its public health objectives (SLL, Citation2013b, p. 15).

When the newly instituted RPTA presented its first Regional Traffic Supply Program in 2012, sustainability stood in focus. The overall theme of this strategic document was: ‘Attractive and sustainable transport system – goals for public transport’ (SLL, Citation2012). The Vice-Head of the Department of Strategic Development told us that ‘attractive travel’ was supposed to imply a modal shift, where car owners leave their car in the garage at home and instead use public transport.

shows the RPTA’s Target Model, which is the performance management model used to evaluate how well the entire organization lives up to its vision. The Target Model had some shortcomings though, the RPTA acknowledged in the Regional Traffic Supply Program. Social sustainability, including equality and equity, was mentioned in the Regional Traffic Supply Program but not included in the Target Model. The politicians were not too happy about this, so for the second edition, this had to be included, we were told by a senior strategic planner. Similarly, economic sustainability was only briefly mentioned in the first edition, but this was also to be included in the revised, second edition. Even though Global Compact had been part of the organization since 2009, this was not visible in the Target Model either. But work on this was under way in 2012, the RPTA stated in the first Regional Traffic Supply Program (SLL, Citation2012, p. 17).

Figure 1. The Target Model (Source: SLL, Citation2012, p. 10).

Ecological sustainability was still much in focus, but social sustainability emerged as a recurring theme throughout the Regional Traffic Supply Program. For the RPTA, social sustainability meant that ‘different social groups and their socio-economic conditions and needs of public transport’ had to be considered (SLL, Citation2012, s. 10). This was crucial for public transport was supposed to contribute to greater equity and equality in the region, the politicians in the County Council had decided. But social sustainability, the way the RPTA expressed it, echoed the discourse of (corporate) social responsibility, which was not very surprising, given that Global Compact was already adopted in the organization. This resulted in the following general statement in the Regional Traffic Supply Program: ‘all people should have equal rights and opportunities regardless of, e.g. ethnicity, faith, sexual orientation, opinion or disability’ (SLL, Citation2012, s. 10). But the real challenge was to translate this stated ambition into measurable targets and to map the development of them over time under the rubric of social sustainability, I and my college were told by one senior planner.

While the first Regional Traffic Supply Program was a product of the civil servants’ work, it was the politicians in the Traffic Board who set up the instructions, commented on draft versions and ultimately decided on its implementation. The policy process was subject to continuous discussions and balancing of various objectives, several interviewees explained. Some of the conflicting objectives and targets were also explicitly discussed in the Regional Traffic Supply Program, e.g. that the goal of cost efficiency may conflict with attractive public transport (SLL, Citation2012, p. 21). The task of balancing conflicting goals and prioritizing between different targets, though, was part of the political process, the RPTA stated explicitly in the Regional Traffic Supply Program (SLL, Citation2012, p. 21).

Developing a strategy for sustainable development

Unsatisfied with the lack of targets on social sustainability, the politicians instructed the civil servants to develop and come up with specific goals for social sustainability, one strategic planner explained (see also SLL, Citation2013a, Citation2013b). In March 2013, the result of this work was presented by the sustainability manager, along with senior staff in the Department of Strategic Development, in a strategic policy document called The Strategy for Sustainable Development. This document began by stating that it is not enough that public transport is more sustainable compared to other modes of motorized transport, but public transport must also ‘be developed in a way that is viable from the three sustainability perspectives: environmental and social and economic’ (SLL, Citation2013b, p. 2). The collaborative space in which this strategy developed was made up of cooperative and sympathetic relationships between the politicians in the Traffic Board and the group of civil servants in the unit of Sustainable Development. As these relationships were largely mediated through the production and circulation of documents, it was by examining these documents, it became possible to trace the relationships that made up this collaborative space. Eight principles were to guide the work towards sustainable development. Each of the principles was also explained in detail in terms of (i) what it meant, (ii) why it was included and (iii) how it would be realized. In addition to the environmental principles – which included use of renewable fuels, reduced noise, recyclable materials in new construction and so on – a definition and measurements of social sustainability were included for the first time. The RPTA, the document stated, would work systematically for achieving ‘social responsibility in accordance with international conventions’ (SLL, Citation2013b, p. 2) Social responsibility can include, for example, (i) not employing or benefitting from child or forced labour; (ii) non-discrimination; (iii) work against corruption; (iv)) fair wages and working hours; (v) freedom of association and (vi) ensuring health and safety (SLL, Citation2013b). To ensure that ‘the fundamental human rights and working conditions are met’ in the production of goods and services, SLL [the RPTA] should monitor and secure compliance among its pool of procured operators. While working on a new and updated version of the Regional Traffic Supply Program, where the Strategy for Sustainable Development would be an integrated part, the RPTA also updated its website with the following definition: ‘Social sustainability is the goal, ecology sets the framework, while the economy is a means and a prerequisite for sustainable development’ (SLL, Citation2017).

In sum, procurement and contract compliance is an important part of the RPTA’s operations. While procurement has a time frame that usually ranges between 5 plus 5 years, physical planning and infrastructure projects work with a time frame that stretches much further ahead into the future, for they are both capital-intensive and difficult to undo once in place. As will be explained further below, this has meant that the market space and the planning space render different translations.

The planning space of public transport: integrating transport and land-use development

In Sweden, the municipalities are the sole land-use authority and they decide on the design of streets as well as on new areas for housing development. Integrating land-use and public transport constitute one of the main challenges for enabling sustainable transport, according to our interviewees. The civil servants in the Department of Strategic Development carry out a wide array of work tasks, including meeting representatives from the municipalities to discuss long-term planning as well as specific projects. Rather than having tough and challenging meetings, where everyone sits down to discuss the challenges with the long-term planning, and possibly face the risk of conflict, these meetings were often couched to be pleasant and not supposed to lead to, or involve, heated debates, explained one planner. For sustainability to be achieved, however, tough decisions that implicate trade-offs are unavoidable, he added. The challenge with multi-level collaboration, as between the RPTA and the municipalities, continued the same planner, is that ‘we always must trust that our counterpart understands what is best for them, but there are situations where they do not’. When this is not the case, collaboration becomes a challenge, as mutual understanding becomes difficult to achieve, he concluded. Emerging here is a picture where the collaborative space is crucial in and of itself and for maintaining a positive atmosphere, while tough negotiations, which potentially could lead to improved outcomes in terms of sustainability, are avoided.

Organizing the measurements, locating the data sources

Sustainability remains a key issue and a boundary concept, around which actors gather to deliberate and discuss different courses of actions. Despite being a household concept, sustainability is elusive, unless it is broken down into smaller components and measured accordingly (Lyytimäki et al., Citation2013). This view was reflected by many of those being interviewed and by the fact that the responsibility for measuring sustainability was divided among three civil servants; one working on mainly environmental issues, another on social issues and a third on economic issues. The civil servant working on environmental issues had the responsibility to gather data on levels of noise, use of bio and fossil fuels, levels of emissions and so on. Other civil servants, working with measuring social sustainability, gathered data on accessibility, as well as data on public health and elderly transportation services. A third civil servant was responsible for keeping track of the economic impacts of public transport on society at large, e.g. by providing data on crowding on busses and trains, as well as data on traffic congestion. Thus, the task to measure sustainability was organized and entrusted to three persons. The politicians and the civil servants in the top-management team used these data to assess how well the RPTA as a whole managed to fulfil its objectives in The Target Model.

One planner reverberated the claim that sustainability is an ambiguous concept to which everyone has their own definition, but she qualified this claim by adding that this ambiguity also has implications for the funding of public transport. Although a bit long, her quote on this matter is well formulated and therefore worth including in its entirety.

At the overall level, all parties seem to agree and think the same; for example: ‘I am for sustainable public transport’. It’s easy to say. But when you start to break it down, what does that really mean? It means that it may cost this much. So why scrimping? The financing issue always pops up. It is an important issue, but it can also ‘fool’ both parties into believing that they do not want to pay, when it is actually the same tax money they’re quarrelling about. (Strategic planner, RPTA)

Quarrelling about whose resources will be used is meaningless when those resources come from the same source would be a fair summary of her main argument. Yet, within each organization, those resources are understood as scarce as they come from either the County Council’s or the municipalities’ budgets, which both are limited. What this boils down to, the same planner explained, are priorities. Even though all strategic documents and plans contain the same set of keywords, priorities must be made for policy and planning to move forward in a sustainable manner, and politicians are far from being involved in this on a regular basis.

Returning to the first version of the Regional Traffic Supply Program, the Vice-Head of the Department of Strategic Development told us that some of the objectives in the Target Model had been recycled from previous strategic documents. What is new, and substantially so, he told us, was the targets to increase the market share for public transport of all motorized transport and the speeding up of travel time. To achieve this, traffic signals that prioritize busses and trams, as well as right-of-way lanes, are necessary. These initiatives, he suggested, require collaboration with municipalities about land-use and urban development. But as much as these targets are related to the long-term planning of public transport and the collaboration between the RPTA and the municipalities, they are also connected to the procured traffic operators’ way of operating the buses and to traffic congestion, which, once again, are contingent on the integration of transport and land-use planning.

Conflicting goals in planning

When developing public transport, priorities are most difficult to agree upon when it comes to the questions of how land will be used, and at what cost. Several planners mentioned this in various ways. As concepts are translated and edited according to local configurations, sustainability means different things to different groups of people. Sustainable public transport is no exception. For example, in the plan to develop the Southern Tramway, a large-scale project to the South and South-West of Stockholm, sustainable public transport meant at least two different things. On the one hand, it meant that the tramway should run on separate embankments to speed up travel time and to make public transport an attractive option for car drivers. This translation was most clearly expressed in the statements by the RPTA. On the other hand, sustainable public transport also meant that the tramway should mix with other modes of urban traffic, to calm down car traffic and create a more urban streetscape. This translation was vibrantly expressed by the municipalities through which the tramway would run.

Conflicts also emerge because incommensurable objectives are embedded in the different laws and in political objectives (e.g. de Roo, Citation2000). It is in this intricate policy landscape and legislation that the RPTA not only procure traffic, but also develop understandings of sustainability in its planning space. Besides the formal changes coming with the new law in 2012, public transport in Stockholm has undergone other changes, epistemic ones, as well. From being understood and treated ‘as some sort of welfare for people who did not have the sense to buy a car, public transport is now seen as a precondition for survival and growth’, explained one planner. This has meant, he added, that public transport policy and planning has become much more interesting and important for the politicians, ‘and this is also why public transport is understood as a tool by the politicians’, he clarified, before continuing with retelling the history of political–administrative relationships in the public transport authority in Stockholm.

Understanding the connections between how and where sustainability is translated

Emerging from the interviews is a picture where there are plenty of discussions and collaborations between the politicians in the County Council’s Traffic Board and the planners and managers in the RPTA. From what I could understand, these discussions orbited around the question what needs to be done to achieve sustainable transport.

As has been suggested here, procurement and planning are two collaborative spaces in which sustainability is translated. Whereas the former involves setting up requirements when designing contracts and ensuring compliance, the latter is not based on refined contracts, but on mutual understanding between the planners in the RPTA and the planners in the municipalities. Whereas environmental and social requirements on operators can be specified in the designing of contracts, the integration of land-use and transport planning is a much more ambiguous undertaking, as this cannot be broken down into measurable targets. This also has implications for how politicians and civil servants collaborate and how sustainability is translated in the RPTA.

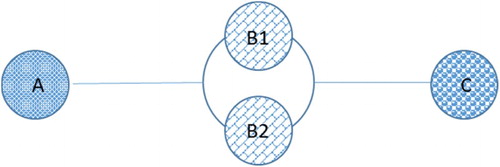

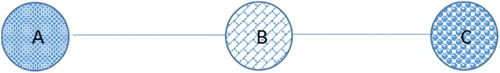

The relationships between (A) the politicians and (B) the civil servants, as well as the relationships between (B) the civil servants, on the one hand, and (C) the traffic operators and the municipalities, on the other hand, can schematically be described as follows.

displays the collaborative space on the market side of the authority, where (A) the politicians in the County Council’s Traffic Board formally set targets and decide on goals for (C) the procured traffic (including fuels, emissions, polluting particles, etc.). And this is done with the aid of (B1) the civil servants and their knowledge about measurements and data sources, while (B2) another group of civil servant’s design contracts and ensure compliance of (C) the procured traffic. The civil servants are here taking a role as knowledge brokers, as they are intermediaries that develop relationships and facilitate translations, while also bringing their own knowledge and expertise to the extended relationships (Lundquist, Citation1998).

shows the collaborative space on the planning side of the authority, where (A) the politicians in the County Council formally set targets and decide on goals for the long-term planning, which is contingent on multi-level collaborations, primarily with (C) the planners and civil servants in municipalities. But it is (B) the civil servants (strategic planners) in the RPTA who manage and maintain the collaborative spaces with (C) the planners in the municipalities. Here, the civil servants take on the roles of an ombudsman (Lundquist, Citation1998), or even an inside activist (Olsson & Hysing, Citation2012), as they contribute to translating the ambiguous concept of sustainability onto the extended relationships with the municipalities.

The two collaborative spaces render different relationships, which further lead to various types of translations of sustainability. In the market space, the politicians govern at a distance by way of setting quantitative and measurable targets for the traffic operators, rendering the civil servants as intermediaries or knowledge brokers in the translation process (Lundquist, Citation1998). Sustainability is not only confined to quantitative environmental requirements transferred to operators by contract; it has also broadened over the years. Beginning in 2009, social responsibility formally entered the organization through the adoption of Global Compact, and in 2012, with the first Regional Transport Supply Program, social sustainability was mentioned but not defined in the Target Model. The politicians instructed the civil servants to produce measurable targets also for social sustainability; otherwise, it would be difficult to measure the overall progress towards sustainability both ecologically and socially. While this might suggest that the civil servants were a tool for the politicians, the civil servants were in fact providing the politicians with the knowledge about the measurability of targets and so limiting the scope of interpretation of sustainability.

In the planning space, the planners are rendered as more than intermediates, for they are creating the opportunities and imaginaries that the politicians must consider when deciding on the trajectory of long-term planning. How public transport should be integrated in the urban environment is largely beyond the influence of the politicians, as this is primarily a qualitative undertaking, contingent on the urban landscape and land use. The politicians do have comments on this, obviously, and ultimately also decide on budgetary constraints for specific projects and for planning. As indicated above, however, it is the planners from the RPTA who meet the planners from the municipalities and discuss and subsequently translate sustainable transport into specific projects (e.g. the Southern Tramway). As the civil servants are acting as an ombudsman and occasionally as an inside activist (Hysing & Olsson, Citation2011), sustainability is translated as the remaking of urban spatial development with the target to increase the modal share of public transport. Unlike the market side of the public transport, where the translation of sustainability follows quantitative measurements, the integration of transport and land use is difficult to measure, let alone evaluate for the politicians, in quantitative terms. But the modal share of public transport works as a proxy for measuring sustainable transport.

Conclusions

This paper has contributed to the understanding of sustainability in general and sustainable transport in particular by investigating how and where this overarching policy has been translated in the context of public transport. By drawing upon the literature on policy translation and political–administrative relationships, an innovative framework was developed around the concept of collaborative spaces. This framework was applied to analyse the how and where sustainable transport was translated in the political–administrative nexus in the RPTA in Stockholm.

Two main conclusions were identified, one related to the question how sustainability has been translated, and another related to the question where, in which collaborative spaces, this has occurred.

Firstly, over the years, sustainability has expanded to include not only ecological concerns, but also social and economic ones. Environmental sustainability has been around since the late 1980s in public transport in Stockholm, when biofuels started to replace fossil fuels. Although the first environmental policy was not presented until 2004, policies pertaining to environmental sustainability had been part of other policies and guidelines. Environmental sustainability was surrounded by a high degree of political consensus, for it has historically been translated as a policy that seeks to increase the modal share of travel by public transport. Environmental sustainability has also been standardized and transferred to the private traffic operators via the civil servants’ design of contracts and monitoring of compliance. Environmental sustainable transport was translated into measurements of biofuels, emissions, noise and so on, and so mechanically reproduced from the politicians via the civil servants to the private operators. Following the previously discussed theories of translation, this was a translation process that involved little room for interpretation for the receiving organization. However, in 2009, social sustainability entered Storstockholms lokaltrafik when it decided to adopt UN’s Global Compact. This is how the discourse of (corporate) social responsibility entered the organization, a discourse that has become ever more present during the past few years. Yet, socially sustainable transport remains open to a wide range of interpretations, which is why the politicians demanded the civil servants to develop new measurements.

Secondly, sustainability has been translated in two distinct ways in two different spaces of the RPTA. In the market space, the politicians have primarily governed at a distance by setting measurable goals and targets for the procured traffic, and left the designing of contracts and the task of ensuring compliance to the civil servants. Thus, the collaborative space was shaped by what I term quantized relationships. This is because the quantitative measures used to translate sustainability from policy to operations further shaped the relationships between the politicians and the civil servants insofar as the latter were cast as intermediaries or knowledge brokers between the politically set goals and targets, on the one hand, and the private traffic operators, on the other hand. In the planning space, the politicians have generally been preoccupied with administering the budget and deciding on major investments, while the civil servants have been responsible for making sense of and figuring out ways to measure sustainable transport and lately social sustainable development. Yet, sustainability measurements have been hard to quantify when it comes to integrating transport and land-use planning. This was solved in an organic manner, in specific projects, between the strategic transport planners in the RPTA and planners in the municipalities.

These two main conclusions are of relevance to previous studies as they show that policy translation is far from a straightforward process inside the translating organization. Rather, the policy translation process and its outcomes are contingent on the collaborative spaces between the politicians and the civil servants, and their relationships to their respective group of stakeholders. Unlike previous studies investigating policy translation processes in the context of urban development, like Business Improvement Districts (Cook & Ward, Citation2012; Peyroux, Pütz, & Glasze, Citation2012) or Buss Rapid Transit (Montero, Citation2017; Wood, Citation2014, Citation2015a), this study has contributed with new knowledge of how and where an empty signifier, in this case sustainability, has been translated. How sustainability is supposed to be achieved in a context that is comparatively already sustainable is, thus, contingent on how it is interpreted and defined – i.e. translated – which, again, is a shaped by where, in which collaborative spaces, this occurs.

Acknowledgements

I would like to offer my special thanks to Karolina Isaksson, Claus Hedegaard Sørensen, Tom Rye, Christina Lindkvist Scholten and Robert Hrejla for their valuable comments and constructive criticisms on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Alexander Paulsson obtained his PhD from Lund University and is currently doing research on the governance of sustainability in the transport sector at K2, the Swedish Knowledge Centre for Public Transport. He shares his time between Lund University School of Economics and Management and VTI, the Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute. His research interests include organization studies, critical political economy, STS and ecological economics.

ORCID

Alexander Paulsson http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6114-7397

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Previously, SL bought and owned most of the buses in regular service, while private traffic operators leased them as part of the procurement contract. Nowadays, bus operators increasingly own the buses, but there is still a mixture of owning and leasing, depending on the procurement contract.

References

- Aberbach, J. D., & Rockman, B. A. (2006). The past and future of political-administrative relations: Research from bureaucrats and politicians to in the web of politics – and beyond. International Journal of Public Administration, 29(12), 977–995. doi: 10.1080/01900690600854589

- Avelino, F., Grin, J., Pel, B., & Jhagroe, S. (2016). The politics of sustainability transitions. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 557–567. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2016.1216782

- Banister, D. (2008). The sustainable mobility paradigm. Transport Policy, 15(2), 73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2007.10.005

- Bergström, T., & Khan, J. (2007). SL och hållbara transporter. TransportMistra. Retrieved from https://lucris.lub.lu.se/ws/files/5701062/5148357.pdf

- Boussauw, K., & Vanoutrive, T. (2017). Transport policy in Belgium: Translating sustainability discourses into unsustainable outcomes. Transport Policy, 53, 11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.08.009

- Briscoe, F., & Gupta, A. (2016). Social activism in and around organizations. The Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 671–727. doi: 10.1080/19416520.2016.1153261

- Buden, B., Nowotny, S., Simon, S., Bery, A., & Cronin, M. (2009). Cultural translation: An introduction to the problem, and responses. Translation Studies, 2(2), 196–219. doi: 10.1080/14781700902937730

- Bulkeley, H., & Betsill, M. (2005). Rethinking sustainable cities: Multilevel governance and the ‘urban’ politics of climate change. Environmental Politics, 14(1), 42–63. doi: 10.1080/0964401042000310178

- Callon, M. (1986). Some elements of a sociology of translation: Domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. In J. Law (Ed.), Power, action and belief: A new sociology of knowledge? (pp. 196–233). London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Cervero, R. (1998). The transit metropolis: A global inquiry. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Clarke, J., Bainton, D., Lendvai, N., & Stubbs, P. (2015). Making policy move: Towards a politics of translation and assemblage. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Cook, I. R., & Ward, K. (2012). Conferences, informational infrastructures and mobile policies: The process of getting Sweden ‘BID ready’. European Urban and Regional Studies, 19(2), 137–152. doi: 10.1177/0969776411420029

- de Roo, G. (2000). Environmental conflicts in compact cities: Complexity, decision making, and policy approaches. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 27, 151–162. doi: 10.1068/b2614

- Dobbin, F., Simmons, B., & Garrett, G. (2007). The global diffusion of public policies: Social construction, coercion, competition, or learning. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 449–472. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.090106.142507

- Dwyer, P., & Ellison, N. (2009). ‘We nicked stuff from all over the place’: Policy transfer or muddling through? Policy & Politics, 37(3), 389–407. doi: 10.1332/030557309X435862

- Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., & Balogh, S. (2012). An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(1), 1–29. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur011

- European Commission, DG Env. (2017). European green capital. Website. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/environment/europeangreencapital/winning-cities/2010-stockholm

- Farley, H. M., & Smith, Z. A. (2013). Sustainability: If it’s everything, is it nothing? Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

- Freeman, R. (2009). What is translation? Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 5 (4), 429-447. doi: 10.1332/174426409X478770

- Grange, K. (2017). Planners – A silenced profession? The politicisation of planning and the need for fearless speech. Planning Theory, 16(3), 275–295. doi: 10.1177/1473095215626465

- Healey, P. (2010). Making better places: The planning project in the twenty-first century. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Healey, P. (2012). The universal and the contingent: Some reflections on the transnational flow of planning ideas and practices. Planning Theory, 11(2), 188–207. doi: 10.1177/1473095211419333

- Healey, P. (2013). Circuits of knowledge and techniques: The transnational flow of planning ideas and practices. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(5), 1510–1526. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12044

- Hull, A. (2008). Policy integration: What will it take to achieve more sustainable transport solutions in cities? Transport Policy, 15(2), 94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2007.10.004

- Hysing, E., & Olsson, J. (2011). Who greens the northern light? Green inside activists in local environmental governing in Sweden. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 29, 693–708. doi: 10.1068/c10114

- Kenis, A., Bono, F., & Mathijs, E. (2016). Unravelling the (post-)political in transition management: Interrogating pathways towards sustainable change. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 568–584. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2016.1141672

- Kenis, A., & Lievens, M. (2014). Searching for ‘the political’ in environmental politics. Environmental Politics, 23(4), 531–548. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2013.870067

- Lafferty, W., & Hovden, E. (2003). Environmental policy integration: Towards an analytical framework. Environmental Politics, 12(3), 1–22. doi: 10.1080/09644010412331308254

- Lagendijk, A., & Boertjes, S. (2013). Light rail: All change please! A post-structural perspective on the global mushrooming of a transport concept. Planning Theory, 12(3), 290–310. doi: 10.1177/1473095212467626

- Lange, P., Driessen, P. P. J., Sauer, A., Bornemann, B., & Burger, P. (2013). Governing towards sustainability – Conceptualizing modes of governance. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 15(3), 403–425. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2013.769414

- Lundquist, L. (1998). Demokratins väktare: ämbetsmännen och vårt offentliga etos. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Lyytimäki, J., Tapio, P., Varho, V., & Söderman, T. (2013). The use, non-use and misuse of indicators in sustainability assessment and communication. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 20(5), 385–393. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2013.834524

- McCann, E., & Ward, K. (Eds.). (2011). Mobile urbanism: Cities and policymaking in the global age. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McCann, E., & Ward, K. (2015). Thinking through dualisms in urban policy mobilities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(4), 828–830. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12254

- Meadowcroft, J. (2007). Who is in charge here? Governance for sustainable development in a complex world. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 9(3–4), 299–314. doi: 10.1080/15239080701631544

- Montero, S. (2017). Study tours and inter-city policy learning: Mobilizing Bogotá’s transportation policies in Guadalajara. Environment and Planning A, 49(2), 332–350. doi: 10.1177/0308518X16669353

- Murray, M. J. (2017). The urbanism of exception: The dynamics of global city building in the twenty-first century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Newig, J., & Fritsch, O. (2009). Environmental governance: Participatory, multi-level and effective. Environmental Policy and Governance, 19, 197–214. doi: 10.1002/eet.509

- Olsson, J. (2009). The power of the inside activist: Understanding policy change by empowering the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF). Planning Theory & Practice, 10(2), 167–187. doi: 10.1080/14649350902884425

- Olsson, J., & Hysing, E. (2012). Theorizing inside activism: Understanding policymaking and policy change from below. Planning Theory & Practice, 13(2), 257–273. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2012.677123

- Overeem, P. (2005). The value of the dichotomy: Politics, administration, and the political neutrality of administrators. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 27(2), 311–329.

- Overeem, P. (2006). Forum: In defense of the dichotomy: A response to James H. Svara. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 28(1), 140–147.

- Paulsson, A. (2014). Arenan och den entreprenöriella staden: Byråkrati, viljan att samverka och gåvans moraliska ekonomi (PhD. Diss). Lund University.

- Peck, J. (2011). Geographies of policy: From transfer-diffusion to mobility-mutation. Progress in Human Geography, 35(6), 773–797. doi: 10.1177/0309132510394010

- Pell, C. (2016). Debate: Against collaboration. Public Money & Management, 36(1), 4–5. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2016.1103410

- Peyroux, E., Pütz, R., & Glasze, G. (2012). Business improvement districts (BIDs): The internationalization and contextualization of a ‘travelling concept’. European Urban and Regional Studies, 19(2), 111–120. doi: 10.1177/0969776411420788

- Redclift, M. (2005). Sustainable development (1987–2005): An oxymoron comes of age. Sustainable Development, 13(4), 212–227. doi: 10.1002/sd.281

- Roy, A. (2011). Urbanisms, worlding practices and the theory of planning. Planning Theory, 10(1), 6–15. doi: 10.1177/1473095210386065

- Sims, R., Schaeffer, R., Creutzig, F., Cruz-Núñez, X., D’Agosto, M., Dimitriu, D. … Tiwari, G. (2014). Transport. In O. Edenhofer, R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, & J. C. Minx (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of working group iii to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 599–670). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- SL. (2009). Årsredovisning 2009. Retrieved from http://www.sll.se/Global/Verksamhet/Kollektivtrafik/%C3%85rsber%C3%A4ttelser%20f%C3%B6r%20SL/arsredovisning-2009.pdf

- SLL. (2011a). Miljöutmaning 2016. Miljöpolitiskt program för Stockholms läns landsting Beslutad av Landstingsfullmäktige i december 2011. Retrieved from http://kultur.sll.se/sites/kultur/files/miljoutmaning_2016.pdf

- SLL. (2011b). Förslag till miljöpolitiskt program för Stockholms läns landsting 2012–2016. Sammanträdeshandlingar. Retrieved from http://sammantradeshandlingar.sll.se/sites/sammantradeshandlingar.sll.se/Handlingar/Trafiknamnden/2011/juni/Arende%2015%20TN%201105-130%20Forslag%20miljopolitiskt%20program%20SLL%202012-2016.pdf

- SLL. (2012). Regionalt trafikförsörjningsprogram för Stockholms län. Trafiknämnden Stockholms läns landsting. Retrieved from http://www.sll.se/Global/Verksamhet/Kollektivtrafik/Regional%20Trafikf%C3%B6rs%C3%B6rjningsprogram/trafikforsorjningsprogram-juni-2012.pdf

- SLL. (2013a). Miljöpolicy och principer. Dnr. SL-2008-10018. Retrieved from http://www.sll.se/Global/Verksamhet/Kollektivtrafik/H%C3%A5llbar%20utveckling/Milj%C3%B6policy-och-principer-2013-07-25.pdf

- SLL. (2013b). Trafikförvaltningens strategi för hållbar utveckling - för den regionala kollektivtrafiken i Stockholms län. Dnr. SL-2013-00546. Retrieved from http://www.sll.se/Global/Om%20landstinget/Styrdokument/Kollektivtrafik/Strategi-for-hallbar-utveckling-2013-03-04.pdf

- SLL. (2015). Global compact communication on progress rapport 2014. Retrieved from http://www.sll.se/Global/Verksamhet/Kollektivtrafik/Hållbar%20utveckling/SL-Global-Compact-redovisning-2014-.pdf)

- SLL. (2017). Regionala trafikförsörjningsprogrammet. Retrieved from http://www.sll.se/verksamhet/kollektivtrafik/kollektivtrafiken-vaxer-med-stockholm/regionala-trafikforsorjningsprogrammet/

- SL Press release. (2012). SL nådde miljömålen – vidare mot nya utmaningar. Retrieved from http://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/sl/pressreleases/sl-naadde-miljoemaalen-vidare-mot-nya-utmaningar-743994

- Stone, D. (2012). Transfer and translation of policy. Policy Studies, 33(6), 483–499. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2012.695933

- Svara, J. H. (2006a). The search for meaning in political-administrative relations in local government. International Journal of Public Administration, 29(12), 1065–1090. doi: 10.1080/01900690600854704

- Svara, J. H. (2006b). Forum: Complexity in political-administrative relations and the limits of the dichotomy concept. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 28(1), 121–139.

- Swyngedouw, E. (2010). Apocalypse forever? Theory, Culture and Society, 27(2–3), 213–232. doi: 10.1177/0263276409358728

- Temenos, C., & Mccann, E. (2012). The local politics of policy mobility: Learning, persuasion, and the production of a municipal sustainability fix. Environment and Planning A, 44, 1389–1406. doi: 10.1068/a44314

- Temple, B. (1997). Watch your tongue: Issues in translation and cross-cultural research. Sociology, 31(3), 607–618. doi: 10.1177/0038038597031003016

- Uittenbroek, C. J. (2016). From policy document to implementation: Organizational routines as possible barriers to mainstreaming climate adaptation. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(2), 161–176. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2015.1065717

- Wildavsky, A. B. (1979). Speaking truth to power. New Brunswick: Transaction.

- Wood, A. (2014). Learning through policy tourism: Circulating bus rapid transit from South America to South Africa. Environment and Planning A, 46(11), 2654–2669. doi: 10.1068/a140016p

- Wood, A. (2015a). The politics of policy circulation: Unpacking the relationship between South African and South American cities in the adoption of bus rapid transit. Antipode, 47(4), 1062–1079. doi: 10.1111/anti.12135

- Wood, A. (2015b). Tracing policy movements: Methods for studying learning and policy circulation. Environment and Planning A, 48(2), 391–406. doi: 10.1177/0308518X15605329

- Yanow, D. (2007). Interpretation in policy analysis: On methods and practice. Critical Policy Studies, 1(1), 110–122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2007.9518511