ABSTRACT

Conceptualizing and analyzing collective policy learning processes is a major ongoing theoretical and empirical challenge. A key gap concerns the role of exogenous factors, which remains under-theorized in the policy learning literature. In this paper, we aim to advance the understanding of the role that exogenous factors play in collective learning processes. We propose a typology of exogenous factors (i.e. material, socioeconomic, institutional, discursive), and subsequently apply this in a comparative study of flood risk policymaking in two municipalities in the Netherlands. We find that exogenous factors are indeed essential for understanding collective learning in these cases, as the combined influence with endogenous factors can steer similar learning processes towards different learning products. We conclude our contribution by identifying two opportunities for further developing the collective learning framework, namely regarding the distinction of varying learning products, and the dynamics of exogenous factors over time.

1. Introduction

The topic of learning in environmental governance is drawing increasing attention and plays a key role in ongoing discussions, for instance on adaptive policymaking (Gerlak, Heikkila, Smolinski, Huitema, & Armitage, Citation2018; Pahl-Wostl, Citation2009). Within complex human-environmental systems, rapidly changing societies, and particularly in the face of climate change, understanding how learning processes can be initiated and supported is considered crucial to successful environmental governance (Ison, Citation2010; Pahl-Wostl, Citation2009; Rodela, Citation2011). Despite substantial research into learning in environmental governance over the last decades, there is still little consensus on learning processes and their drivers (Baird, Plummer, Haug, & Huitema, Citation2014; Gerlak et al., Citation2018; Reed et al., Citation2010). This is partly due to a lack of theoretical clarity, as well as due to the challenges of empirically studying learning processes which can be influenced by a wide range of factors.

There is a broad recognition in the literature that learning processes within a policy system involving a collective of actors engaged with policymaking can be influenced by both endogenous factors (e.g. resources, collaboration, leadership) and exogenous factors (e.g. societal disruptions such as disasters, changes in other linked policy sectors, and the influence of broader political economic forces) (Bennett & Howlett, Citation1992; Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013; Nilsson, Citation2006; Sabatier, Citation1988; Williams, Citation2009). In this contribution, we specifically explore the role of exogenous factors because as of yet they have received only limited attention in the literature focusing on policy learning, at both conceptual and empirical levels. This puzzling situation means that, whilst exogenous factors are often mentioned as a trigger for learning and policy change (e.g. Nohrstedt & Weible, Citation2010; Sabatier, Citation1988), there is little understanding of which factors then matter and how they matter.

In this contribution, the term ‘exogenous factors’ refers to the drivers, actors, processes or institutions that (potentially) have a causal relation with learning in a specific policymaking subsystem or its outcomes, but which originate ‘outside’ of that policymaking subsystem and are not directly determined by the subsystem. Related terms are ‘external factors’ (de Loë & Patterson, Citation2018; Massey, Biesbroek, Huitema, & Jordan, Citation2014), and ‘distal factors’ (Cox, Citation2011), terms which also seek to reflect the idea of certain variables being ‘outside’ of the immediate scope of analysis. Yet, the boundaries between endogenous and exogenous factors are often difficult to delineate, and may even prove somewhat arbitrary (de Loë & Patterson, Citation2018; Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013; Howlett & Cashore, Citation2009). We fully acknowledge that analysts always face the practical challenge of limiting their scope in examining and diagnosing policy problems, thus rendering some factors (at least analytically) exogenous. Our argument, however, is that most authors have essentially used the category of exogenous factors to ‘park’ or isolate issues of lesser interest, which effectively means that they receive little attention, let alone substantial scrutiny.

In this paper, we aim to better understand the influence of exogenous factors on policy learning processes with a focus on municipal environmental governance. We build on the small pool of literature that has discussed exogenous factors in learning in policymaking settings, while also using insights about exogenous factors from other literatures discussing policy, and offer a heuristic approach to categorizing the types and elaborating their potential influence. Specifically, we seek to contribute to the further development and refinement of the collective learning framework developed by Gerlak and Heikkila (Citation2011) and Heikkila and Gerlak (Citation2013). This framework conceptualizes collective learning in policymaking processes (e.g. involving public agencies, interest groups, and networks). Whilst it acknowledges a key role for exogenous factors, the elucidation of this category remains tentative, and in fact, the authors acknowledge ‘further research is necessary to better understand the conditions around which exogenous factors might shape learning processes’ (Gerlak & Heikkila, Citation2011, p. 639).

In order to tackle this gap, we develop and apply a heuristic of key types of exogenous factors (i.e. material, socioeconomic, institutional, and discursive), examining why and how they influence collective learning processes. We compare two in-depth case studies of municipal flood risk governance in the Netherlands in which similar municipalities situated within a similar national policy context responded differently to flood risks. The central research question is: what types of exogenous factors can influence learning in policymaking processes at a municipal level, through what causal pathways, and with what effects on learning processes? We seek to contribute to the further application, development, and enhancement of the collective learning framework by concretizing the often-neglected but ambiguous role of exogenous factors in policy learning processes in ways that are readily applicable to a broad range of environmental governance settings.

2. Theoretical framework

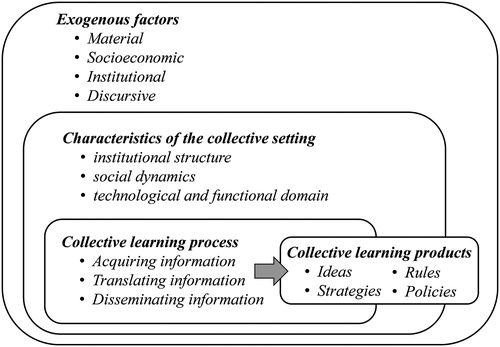

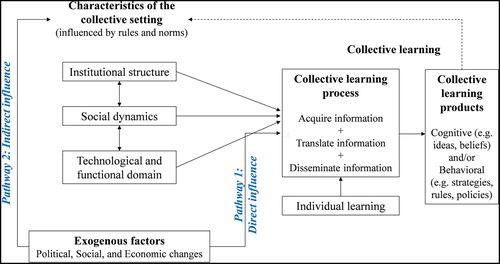

We employ the collective learning framework developed by Heikkila and Gerlak (Citation2013), which focuses on conceptualizing collective learning in policymaking processes (), as a basis for our study. Heikkila and Gerlak distinguish different phases of policy learning. This is based on a definition of learning as a collective process involving individual and group actions, which generates collective cognitive and behavioral learning products (such as new ideas, values, strategies, or policies) (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013, p. 486). According to these scholars, a learning process comprises the acquisition or assimilation, translation or interpretation, and dissemination of information. Other core components of the framework include endogenous characteristics of the collective setting (including: institutional structures which determine internal responsibilities, functions, and tasks; social dynamics which comprise communication, relationships, and trust; and the technological and functional domain that include resources and information flows as well as the activities and output of the collective); and exogenous factors (involving political, social, and economic changes beyond the control of the policymaking collective). This provides a useful conceptual foundation for analyzing collective learning, especially regarding endogenous mechanisms. However, the authors also clearly identify that further conceptualization of exogenous factors is needed.

Figure 1. The collective learning framework of Heikkila and Gerlak (Citation2013), with two pathways of influence of exogenous factors identified.

We pick up on this line of thinking, also acknowledging continued debate about the nature of learning in the literature. For instance, the issue of how to define policy learning exactly is actively debated. Heikkila and Gerlak argue that policy learning is not equal to (change in) policy products: ‘the products of learning, such as a strategy or policy change, cannot be equated to learning without being preceded by a learning process’ (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013, p. 486). Yet, other scholars in the environmental governance domain have argued that learning can only be assessed by looking at behavioral or policy change as signifiers of learning (e.g. Pahl-Wostl, Citation2009). This second view is rooted in the literature on adaptive management which regards experimentation as key to policy learning, and proposes to treat policies as hypotheses. The realization of policy change, which would imply behavioral change, is then regarded as learning (Folke, Hahn, Olsson, & Norberg, Citation2005; Pahl-Wostl, Citation2009). For social learning theorists, interactions between individuals and groups in which experience and knowledge are shared are paramount to learning processes, involving shifts in individual perceptions as well as in intersubjective understandings (Ison, Citation2010; Keen, Brown, & Dyball, Citation2005; Reed et al., Citation2010).

The collective learning framework opens the door to examining the role of exogenous factors in learning, but does not go into depth (Gerlak & Heikkila, Citation2011). Heikkila and Gerlak (Citation2013) observe some ways in which exogenous factors may influence collective learning processes, but point out several apparent ambiguities in the literature about the helpful or hindering influence of exogenous factors in this regard. Together, this indicates a key need to more comprehensively understand the types of exogenous factors that can influence collective learning processes, their effects on learning processes, and their relative importance vis-à-vis endogenous factors.

Based on the framework in , we identify two key pathways of influence of exogenous factors: (1) Direct influence on collective learning processes, affecting how information is processed, and (2) Indirect influence on collective learning processes via shaping the characteristics of the collective setting. To examine these pathways, we first consider ways in which exogenous factors have been considered previously regarding policy learning and policy change (Section 2.1), then develop an expanded categorization of exogenous factors (Section 2.2), and then re-situate this within the collective learning framework (Section 2.3).

2.1. Exogenous factors in policy learning and policy change

Although exogenous factors are often acknowledged in the literature on policy learning, exactly what they involve, and how and why they influence policy learning processes and products remain relatively unelaborated. Often the term ‘exogenous factors’ is used as a container concept for factors that have not been considered or analyzed profoundly, even though these factors are often diverse in nature (e.g. spatially, temporally, substantively, and in scalar terms). Nonetheless, there are antecedents in the policy and environmental governance literatures for theorizing exogenous factors. Here we pick up on a several prominent examples which broadly illustrate and reflect key lines of thinking in these literatures.

In the advocacy coalition framework, exogenous factors play a key explanatory role in driving policy change: ‘change in the core aspects of a policy are usually the results of perturbations in non-cognitive factors external to the subsystem’ (Sabatier, Citation1988, p. 134). Sabatier thus refers to exogenous factors as originating in the environment or context in which a policy subsystem operates. Regarding the effects of dynamic and stable exogenous factors on learning, Sabatier considers legal norms as influencing learning by the degree to which these norms allow policy experimentation and evaluation. He furthermore argues that dynamic exogenous events, including changes in socio-economic conditions and external policy changes and decisions, ‘present a continuous challenge to subsystem actors to learn how to anticipate and to respond to them’ (Sabatier, Citation1988, p. 136). Therefore, he implicitly suggests that these exogenous events may trigger learning whenever they require a response from subsystem actors. More broadly, discussing the influence of exogenous factors on policy change, Sabatier identifies cultural values, social structures, and resource availability as potential factors. These factors may also influence learning processes because they affect the material and cultural boundaries in which subsystem actors can maneuver, and thus opportunities and limits for learning.

In a landmark article on adaptive governance, Folke et al. (Citation2005) identify a central role for learning in response to complex and nonlinear ‘socio-ecological’ dynamics including crises/shocks, in order to successfully govern human-environmental dynamics. These authors identify several examples of such crises, which also have relevance to policy settings: dynamic events such as economic pressures, natural disasters and new governmental policies and regulations, but also ‘rigid paradigms of resource management’ which may point towards rigid and centralized legislation.

In discussing the role of policy networks in policy outcomes, Marsh and Rhodes (Citation1992) recognize four broad categories of exogenous ‘changes’ that influence policy networks: economic, ideological, knowledge-based, and institutional. Case studies in their book provide arguments that recognize economic recession, unemployment, (higher-level) governmental policy and regulations, technical innovation, dominant party ideologies, and knowledge development as important factors determining policy outcomes and policy network development. Although policy networks are defined broader than collective policy settings, often including multiple policymaking collectives, the aforementioned factors were labeled as exogenous changes in the ‘environment’ of the policy network. This then also offers useful insights when considering the wider environment of policymaking.

To illustrate, in integrating and applying established theories of policymaking to the specific domain of flood risk governance, Penning-Rowsell, Johnson, and Tunstall (Citation2017) argue that changes in policy can be either ‘catalytic’, usually after a national flood event, or incremental, in times of local or no flood events. The authors suggest that incremental policy change is ‘a continuous process of learning and adaptation’ (p. 15). In their conceptual model, flood events can function as an exogenous factor initiating both a short-term process of policy change, and a long-term process of incremental change involving learning, possibly influenced by the short-term policy changes. Wiering et al. (Citation2017) claim that a country’s physical setting, economic situation, governance style and legal systems are important in determining stability and change in national flood risk policy. Furthermore, they identify ‘driving forces’ that could influence flood risk governance in Europe, including concerns over ecological degradation, climate change and economic crises; and regulations implemented by the EU. In a case study of national flood risk policy in Hungary, Albright (Citation2011) found that a combination of exogenous factors, including a flood event and changes to the political landscape, induced changes in flood risk governance. Although Albright (Citation2011) and Wiering et al. (Citation2017) do not discuss these factors as determinants of learning per se, it appears from both studies that the options available to actors, and thus the potential for learning, can be affected by such factors.

2.2. Categorizing exogenous factors

Based on the extant literature and our own reasoning, we argue that four key categories of exogenous factors can plausibly influence collective learning processes: Material, Socioeconomic, Institutional, and Discursive (). The approach is intended as a heuristic for guiding in-depth analysis in specific situations, by directing an analyst towards categories of factors that are important to consider. The factors within each category may occur simultaneously, and influence or reinforce each other (e.g. Albright, Citation2011), and thus individual effects may be difficult to disaggregate. Importantly, the role of specific exogenous factors on a policymaking setting may depend on whether the exogenous factors are seen as related to the policy issues of concern. For example, policymaking concerned with floods will be highly sensitive to flood events experienced. Yet there may also be spillovers across issue domains (e.g. health, infrastructure, climate change) (Howlett & Ramesh, Citation2002), as well as factors with more indirect effects (e.g. higher-level policy or legislation, or even shifts in cultural values over time).

Table 1. Categories of exogenous factors potentially influencing collective learning in policymaking settings.

Furthermore, exogenous factors may operate over different timeframes, with different implications for policymaking settings. For example, some relatively stable exogenous factors (e.g. political constitutions) may often be practically taken as fixed, although even these may be susceptible to new legal interpretations over time, which may have drastic consequences for a policymaking setting (e.g. health policy, land rights). Other factors may be dynamic but slow-moving (e.g. unfolding impacts of climate change, population growth and demographic shifts, urbanization and industrialization patterns, and political economic norms) which may impose gradual pressure on policymaking settings. Other exogenous factors still may be faster moving, at timescales closer to that of the policymaking issues in question (e.g. natural disasters, public infrastructure failure, resource extraction decisions, and the focus of policy debates).

2.3. A nested view of exogenous factors

The collective learning framework in Section 2.1 can be (re)conceptualized whereby core components are viewed as nested (). This does not change the fundamental structure of the framework, but offers an alternative way of visualizing how collective learning processes are embedded within several spheres of influence, firstly within the characteristics determining the collective setting, and secondly within a landscape of broader (exogenous) factors.Footnote1 A question arises about the difference between the endogenous characteristics attributed to the collective setting, versus those labeled as exogenous factors. This essentially relates to the way that the analytical scope of a unit of analysis is delineated. For example, exogenous institutional factors may be differentiated from the institutional structure of the collective setting based on whether they are ‘near’ (i.e. proximate) or ‘far’ (i.e. distal) to the collective learning process. The original collective learning framework implies that the institutional structure of the collective setting primarily involves the rules that structure the collective learning process. This appears to be analogous to the way in which Ostrom (Citation2005, Citation2011) theorizes rules that structure a collective choice arena. For example, following Ostrom’s (Citation2005, p. 59) conceptualization of nested action situations, recognizing the role of factors linked to broader institutional arenas such as national and constitutional levels helps to explicitly distinguish the source of exogenous factors.

3. Methodology

3.1. Collective learning in subnational flood risk policymaking

To explore the utility of distinguishing exogenous factors, we apply the aforementioned approach to learning in a subnational governance setting, specifically municipal flood risk policymaking. Subnational governance is an ideal arena for testing this approach because it is subordinate to higher jurisdictional levels, and also likely to be influenced by other diverse factors at broader levels of organization. For example, municipal actors often deal with a variety of policy challenges which are linked to broader scales of institutional, social, and environmental organization (Termeer et al., Citation2011). Flood risk is an example of these multi-level policy domains (see e.g. Crow and Albright in this issue). Besides, the municipal scale allows for a narrow analysis of both endogenous and exogenous factors, and their interplay.

In the Netherlands, municipalities do not have primary responsibility for flood risk governance (see Section 4.1); however, they have a major role in spatial planning. Recently there has also been a movement in flood risk governance nationally from a traditional technical approach (i.e. public authorities building flood defenses) to ‘a more integrated approach that combines flood protection with improving regional spatial quality’ (Termeer et al., Citation2011, p. 174). This asks more of regional and local authorities in their spatial planning, although regulatory changes are slow (Liefferink, Wiering, Crabbé, & Hegger, Citation2018). In the specific cases studied here, both municipalities experienced major riverine floods (the Meuse River) during the 1990s, raising questions about their policy responses, and the extent of collective learning in policymaking in coming to terms with the evolving national institutional context.

In applying the collective learning framework to municipalities, we consider the municipality as a collective policy setting, consisting of various departments and individuals that influence municipal flood risk policy. Policy, in this case, includes procedures, strategies, and courses of action (written or otherwise documented) that influence the development of municipal (flood risk) governance. While we are interested in characterizing exogenous factors in collective learning, we also analyze endogenous factors and the interplay between both sets of factors in learning processes.

3.2. Methods

Empirical research involved comparative analysis of an embedded case study of two cases (Yin, Citation2009) of municipal flood risk governance in the Netherlands. These cases are Roermond and Venlo, two similar medium-sized cities in the southern province of Limburg that were affected by the same riverine floods in the 1990s, and suffered comparable substantial damages (MVW, Citation1994a). Both municipalities conducted policymaking in response to these floods, but have since developed differing approaches to flood risk governance, despite being located relatively close geographically, operating within similar political conditions, and being subjected to similar flood events. This allows for a most-similar systems comparative case study with diverging outcomes. By comparing two cases set within the same broader provincial and national jurisdictional context, it is possible to analyze both the role of endogenous and exogenous factors, and their similar or differing role in influencing policymaking processes.

The empirical research was conducted in the second half of 2017 and included qualitative document analysis and semi-structured interviews to examine the development of flood risk governance since the last two major floods in 1993 and 1995. Document analysis drew directly on city archivesFootnote2 (e.g. policies, plans, newspaper clippings). The combination of archival research and key informant interviews allowed in-depth analysis of processes of collective learning, for instance by discovering ‘core beliefs of the key agents’ (Bennett & Howlett, Citation1992, p. 290; Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013). Other reports on national level flood risk policy and governance (both publicly available as well as sourced directly from key informants) were also included (for an overview, see References). We used qualitative content analysis to analyze documents, seeking to identify ‘underlying themes in the materials being analyzed’ (Bryman, Citation2012, p. 557) and thematic links between documents (Mason, Citation2002). Documents were scrutinized for statements on objectives, goals and developments regarding flood risk policy (ranging from national to local).

We held eleven in-depth semi-structured interviews (approx. 45 min duration; in Dutch) with key informants involved in flood risk governance within the two cases, often over extended time periods. Key informants were identified through the document analysis and ‘snowballing’ (Patton, Citation2002). Interviewees comprised current and former municipal employees, as well as non-municipal actors to examine the municipalities from an external perspective. The breakdown of the interviewees’ background is: municipal spatial planning (4), municipal executive management (3), municipal construction (1), municipal program management (1), provincial program management (1), and civil society (1). The objective of the interviews was to shed light on collective learning processes behind policy changes identified through the document analysis. Questions refrained from specifically referring to learning as we deemed the academic term potentially confusing for interviewees, and from using the terms endogenous and exogenous for similar reasons. Interviews covered topics including the role of flood risk in municipal governance; changes in the nature and effects of flood risk policies; integration of flood risk in spatial planning and general municipal governance; and coordination and collaboration with authorities and actors beyond the municipal level. We interpreted and triangulated findings from interviews and document analysis to deduce insights on collective learning in policymaking processes and factors causing it.

4. Case studies

4.1. Municipalities and flood risk governance in the Netherlands

Municipalities play a significant but circumscribed role in flood risk governance in the Netherlands, being responsible for local land use and spatial planning with which flood risk measures can potentially be integrated into urban (re)development (Schwartz & Koning, Citation1995; van Herk, Zevenbergen, Ashley, & Rijke, Citation2011). Flood risk is primarily a responsibility of other authorities including Regional Water Authorities and the national government with the Ministry of Infrastructure and EnvironmentFootnote3 as well as Rijkswaterstaat (RWS), the national water executive authority (OECD, Citation2014). Municipalities are nonetheless key actors as well because spatial planning is (becoming) central in flood risk governance, for instance in relation to addressing flood exposure and vulnerability (Fleischhauer, Citation2008; Neuvel & van den Brink, Citation2009; van Herk et al., Citation2011; Wheater & Evans, Citation2009).

Venlo and Roermond are the second and third largest municipalities in the province Limburg (after Maastricht), with populations of about 100,000 and 57,000, respectively.Footnote4 Both cities are located along the Meuse River, an international rain-fed river originating in France (). The Meuse’s flow regime is seasonal and relatively sensitive to flooding as well as drought, due to a fast response by water levels to precipitation (RWS, Citation1995). Geographically, Roermond’s urban district is located on the east bank of the river, with artificial lakes on the other riverside that are understood to potentially increase the local water retention capacity. In Venlo, the Meuse flows through a relatively small channel, leaving the urban riverside districts on both banks vulnerable to flooding.

4.2. National flood risk governance context

The point of departure for the empirical analysis is the occurrence of two major floods of the Meuse River in 1993 and 1995. As Dutch flood policy had focused on coastal floods for decades, the riverine flood of 1993 surprised both the public and government. Damages were large in 1993 (RWS, Citation1994), but the societal disruption was larger in 1995 as 250,000 people were evacuated. In 1993, damages in Roermond amounted to around 17 million Euros and in erstwhile Venlo to about 21 million Euros, with another 12 million Euros of damage in municipalities that are now part of Venlo (Tegelen; Arcen en Velden) (MVW, Citation1994a). Floods in Limburg have never resulted in human fatalities, though.

In response, in 1995 the national government quickly reinforced several levees in Limburg and placed a general ban on construction (or any type of activity) in the Meuse floodplains in all areas where flood risk was higher than 1 in 250 years. This ban was removed after protests from mainly Meuse municipalities, even though they had been lobbying for more national flood risk measures (interviewee 6), but building in the floodplains remained highly restricted (MVW and MVROM, Citation1996). There were exceptions under strict conditions, though, for housing projects that had already been ‘in the pipeline’ (pijplijnprojecten) when the national restrictions were introduced. Both Roermond and Tegelen (now Venlo) made use of this pipeline arrangement. In 2006, continued difficulties in the interpretation and fulfillment of floodplain construction regulations led to the adoption of a new policy directive (Beleidslijn Grote Rivieren). This directive theoretically granted more room for ‘activities’ (e.g. housing, recreation) near the river, provided that initiators would compensate for any increases in flood risk due to these activities (MVW, Citation2006). Compensation could be achieved by, for instance, river widening and removal of objects in floodplains.

The floods also breathed new life into the Maaswerken program. There had been societal resistance against the program that aimed to combine nature restoration and gravel extraction, but the floods provided a window of opportunity to include flood risk mitigation as a third objective to make the program socially and politically acceptable (Warner, Citation2008). The general implementation was delayed several times due to financing issues, though, so the national government temporarily shifted its focus towards raising levees in the largest urban areas in Limburg, such as Venlo and Roermond (Tweede Kamer, Citation2000; Wesselink, Warner, & Kok, Citation2013).

In 2010, the national government introduced the Delta Program, addressing future water issues due to climate change (until 2100), including anticipated increases in flood risk. In 2014, the Delta Program introduced several major changes for flood risk governance in Limburg. For instance, economic assets behind dikes are now integrated in the calculation of flood protection levels. Because of this, the protection levels in Limburg now have to be raised from the Maaswerken standard of 1:250 to 1:1000 for urban areas (with exceptions, such as Roermond) and 1:300 for rural areas (Provincie Limburg, Citation2015; Tweede Kamer, Citation2016).

5. Results

For both municipalities, flood risk was not a major issue before the 1990s. In fact, for municipalities in the Meuse valley, economic interests had outweighed flood risk concerns for a long time, and spatial planning had not been used much by municipalities to address flood risk (MVW, Citation1994b). In both Roermond and Venlo there had been housing developments prior, and more neighborhoods were in the pipeline (interviewees 4; 6; 9; 10; 11; Hinssen, Citation2012). The floods then initiated a policymaking process across all levels in flood risk governance. Briefly put, both municipalities have developed their policies on flood risk much since the 1990s, but in different directions. For Venlo, flood risk has become an issue that has been integrated with issues of urban (riverside) development and nature restoration. Venlo has been and still is trying to avoid that nationally imposed flood risk measures (e.g. requisite dike increases in the Maaswerken and Delta programs) tamper with the rebuilt connection of the city with the river. Roermond, on the other hand, considers flood risk a separate issue from general goals of city development. Roermond has been and is mainly trying to ensure that goals of economic development near the river (mostly housing and recreation) can still be pursued, requiring their commitment to national conditions for flood risk and compensation of any flood risk-increasing activities. To deal with their respective challenges, the municipalities have similarly taken leadership roles in local and regional initiatives involving the river. In these initiatives, they increasingly collaborate with actors from multiple levels.

We find evidence to support the notion that collective learning within policymaking processes has occurred in both cases. summarizes these findings. Although there are quite some similarities in the learning process that Venlo and Roermond have gone through to deal with issues surrounding their flood risk governance, the learning products regarding flood risk policy have diverged largely. To explain these learning processes and products, we start with analyzing the role of endogenous factors and continue with how exogenous factors have complemented these influences, before explicating the interplay between both.

Table 2. Summary of collective learning processes and products in flood risk policymaking in Roermond and Venlo.

5.1. Endogenous factors

Endogenous factors originating in the institutional structure have influenced the learning processes of acquiring, translating and disseminating information. For instance, internal leadership can partially explain why Venlo departed from its path and Roermond continued favoring economic development. In 1998, the new governmental coalition of Venlo developed the Maascorridor program for the Meuse River, integrating flood risk objectives with nature and tourism development to reconnect the city with the river. This initiative was led by a municipal executive of the green left-wing faction, which had formulated the original plan, and introduced a holistic approach to program work in the municipality. This holistic approach has contributed to the diffusion of flood risk as an important policy domain, as various departments collaborated in larger programs with flood risk as an integral pillar, such as Maascorridor, Maasboulevard,Footnote5 and Maas Venlo (Gemeente Venlo, Citation2016; H2O, Citation2004; interviewees 8; 10; 11).

The attitude of Roermond towards economic development might have been triggered or invigorated by the efforts of a municipal executive (active 1998–2012). Several interviewees link him with economic programs in Roermond and attribute to him a rather opportunistic approach (interviewees 4; 6; 11). The municipality of Roermond has maintained a similar opportunism, with projects being regarded individually rather than holistically. This opportunism and a focus on economy have undermined the perceived urgency of flood risk, as substantiated by recent negotiations of Roermond about national protection level standards of the Delta Program, through which Roermond was granted a 1:300 protection level (rather than 1:1000 for other urban areas in Limburg) (interviewee 8).

Differing internal perceptions of flood risk partially explain why Roermond is less reserved about floodplain construction. Whereas the urban part of Venlo is located on both banks of the Meuse River where it flows through a small bottleneck, urban Roermond is only located on the east side of the river along a stretch where the river is wider. Additionally, the Maasplassen lakes are located on the other side of the river to Roermond which provides a retention basin for periods of high water levels.Footnote6 A representative that has worked for both municipalities argues that this situation fails to provide Roermond with many incentives or opportunities to mitigate flood risk, whereas in Venlo those opportunities are more easily seized (interviewee 8). Another interviewee emphasizes the relevance of this experience of the river: ‘Venlo is a bottleneck. […] That small river [here in Venlo], you cannot ignore it. […] In Roermond you can look farther into the distance over the water. That is a really different experience’ (translated, interviewee 10). This furthermore implies a possible indirect exogenous influence of the local geography.

Looking more broadly, several exogenous factors must have played an important role in both cases. For instance, although internal leadership explains how certain policy goals were favored over others, these goals were likely not formulated without preceding developments or consent. Why is economic development so important to Roermond, and why did Venlo consider flood risk as one of four key pillars? How did the issue of flood risk reach the municipalities? How did objectives develop over time?

5.2. Exogenous factors

5.2.1. Material factors

The Meuse floods played initiated a nationwide policy development regarding fluvial flood risk. Roermond initially began to explore options for better protecting the municipality against flooding (interviewee 6) and halted its plans for the neighborhood Oolderveste. Yet, after this initial defensive response, Roermond quickly turned its focus towards urban development again. It began opposing measures from the national government and at the end of the century plans for Oolderveste were reactivated under the national ‘pipeline status’ (interviewee 6; Wolsink, Citation2006). However, the Oolderveste project also provides an example that Roermond was now actively considering flood risk, as the municipality financed several studies into its effects on local flood risk (interviewees 4; 5; 6).

For Venlo, the floods provided an opportunity to turn its focus towards integrated flood risk governance. There had already been propositions for reconnecting the city with the river since early 1990s, but in 1998 they were formally formulated by a new municipal coalition in the Maascorridor program for the Meuse River with four objectives: (1) sustainable flood risk governance; (2) nature development; (3) tourism and recreation; and (4) strengthening the connection of the city with the river. This approach is still visible in recent plans, such as Maas Venlo (Gemeente Venlo, Citation2016).

5.2.2. Socioeconomic factors

There is also a notable divergence of demographic trends between the two cases (Neimed, Citation2017). Roermond has continuously anticipated an increase in its population (Gemeente Roermond, Citation2008; interviewee 8). Early 1990s the municipality annexed adjacent municipalities to accommodate its need for housing development (interviewee 4). Venlo, on the contrary, expects shrinkage. Although pre-flood zoning plans for a new neighborhood near the Meuse could not be revoked, Venlo has since then avoided large-scale construction along the river (interviewee 10).

The precise socioeconomic implications for both cities remain unclear, for instance regarding exact housing needs and impacts of urban growth or shrinkage on the local economies. Regardless, for Venlo, the absence of urban growth has proved to be an enabling factor in addressing flood risk. It allows the city to take a long-term perspective in planning new urban development, such as flood risk, and to take decisions without urgent urbanization pressures (interviewee 10). Indeed, Roermond’s expressed intention to grow (interviewee 8) combined with projected growth at least partially explains why Roermond is pursuing economic developments in riverside locations which Venlo can avoid.

5.2.3. Institutional and discursive factors

The successive floods increased the attention for fluvial flood risk at all levels of society. Municipal officers in Roermond felt strongly about doing everything possible to prevent new flood damages (interviewee 6). Along with other affected municipalities, as well as the provincial government (Wesselink et al., Citation2013), the municipality of Roermond began to lobby for more national flood risk protection (although this attitude quickly turned around when the construction moratorium was imposed). At national level, the increased attention instigated a wide variety of (flood risk) policies and regulations, which eventually restricted municipalities in developing their own (flood) policy. A 2006 national policy directive for floodplain construction was vague about where and how to compensate for flood risk increases, which hindered Roermond in its goals for development along the river. The Maaswerken program interfered with Venlo’s local plans for nature redevelopment and flood risk mitigation. The same applies to the Delta program which again threatens to impose national flood risk measures on Venlo whilst the municipality intends to integrate flood risk with spatial development.

Yet, although these national regulations may seem mere hindrances, they triggered friction with local policymaking, stimulating collective learning processes. For Roermond, this amounted to learning to cope with national regulations to advance municipal interests. Venlo attempts to integrate flood risk issues with spatial planning to prevent too much interference of national flood risk measures. A potential cause for the difference in flood risk integration between the municipalities is that the struggle of Roermond with national legislation was about ‘passive’ legislation that would only affect the city when furthering its economic plans, whilst for Venlo the government has had multiple plans for large dikes that actively affect the (landscape of the) city. This difference in legislative pressure for Roermond and Venlo probably stems from geographical differences between the cities.

5.3. Interplay between endogenous and exogenous factors

As illustrated above, both endogenous and exogenous factors are important in explaining learning processes shaping the diverging products of the two cases. At first, the flood triggered a seemingly similar response in Roermond as in Venlo. Whilst it may seem obvious that the floods initiated a policy process in municipal policy as flood risk could no longer be ignored, this does not explain the accompanied learning processes and the divergence in learning products. After a short period, Roermond focused on housing and tourism development again, probably in anticipation of demographic growth.Footnote7 On the other hand, internal initiative for policy change by a municipal executive in Venlo put the municipality on a new path towards integrated flood risk governance. The absence of demographic pressures also supported the availability of this path. Differing flood risk perceptions due to different landscapes in the municipalities reinforced the apparent logic for pursuing each of these respective policy objectives. National flood risk regulations, partially in response to demands from various levels for more flood risk measures, challenged both municipalities, but ultimately pushed them to learn more about flood risk policymaking (albeit in different directions).

6. Discussion

We now take up three areas of discussion: firstly, assessing the role of exogenous factors in collective policy learning processes in the two cases; secondly, insights for collective learning in policymaking; and finally, broader implications for conceptualizing and analyzing exogenous factors from a temporal perspective.

6.1. The role of exogenous factors in the cases studied

Based on the findings above, the two hypothesized pathways of influence of exogenous factors from appear relevant. The first pathway is where exogenous factors directly influence collective learning processes (e.g. by affecting the acquisition, translation, and/or dissemination of information). The second pathway describes exogenous factors indirectly influencing collective learning processes (e.g. by affecting the institutional structure, social dynamics, and/or technological and functional domain which together comprise the collective setting).

The direct influence of exogenous factors was observable in several ways. The acquisition of information in collective policymaking processes was particularly influenced by expectations about urban growth (Roermond) or urban shrinkage (Venlo), which had a significant influence on the development of local flood risk policies in the two cases. Yet at the same time, underlying policy beliefs about urban growth/shrinkage in each case appeared to be surprisingly robust over many years and even decades. This calls into question the degree to which exogenous events or changing national government policy actually influenced local beliefs, or rather provided sources of information to either actively promote (Venlo) or actively contest (Roermond). Internal learning dynamics were also significantly influenced by the developments in fluvial flood risk policy at national level, which set new parameters for the development of municipal flood risk policy. In both cases, this created friction with local policies, stimulating struggles within local collective policymaking processes to respond to these new requirements. Together, these factors influenced the translation and dissemination of information by local policymakers.

Indirect influences of exogenous factors were also discernible. The institutional structure of the collective setting was influenced through shifts in authority and boundary rules as a result of increased national activity on flood risk governance. For example, new fluvial flood risk regulations such as the construction moratorium along the Meuse River were contested in Roermond because they restricted urban development objectives, and were utilized in Venlo as a window of opportunity to strengthen a new integrated program for the Meuse River. This involved the national government seeking to strengthen its role and extend its scope of authority, as well as further developing the jurisdictional scope (i.e. problem boundaries) of flood risk. Social dynamics characterizing the collective setting were particularly shaped by the generation and subsequent decline of public and political attention linked to the shock of the flood events early 1990s, as well as slower-moving socioeconomic factors influencing debates about urban growth objectives and broader economic development priorities. This had a focusing effect on policymaking for fluvial flood risk across all levels of government (local, provincial, national), although this was not necessarily a lasting effect. Attention at the municipal level waned and reconfigured back around underlying tensions between socioeconomic and environmental concerns, although the two cases subsequently weighed these priorities differently in their overall strategic planning agendas. The role of the technological and functional domain was less clear; although, clear goal-setting by Venlo (by emphasizing integrated flood risk governance) and by Roermond (retaining a focus on economic growth) may have facilitated the learning process by avoiding ambiguity in their ‘activities of interest’ (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013, p. 499).

In both cases, we observed the role of natural disaster and national regulations triggering responses at a municipal level. The case studies also show that similar learning processes do not necessarily lead to similar collective learning products. Endogenous factors certainly play a role in this, as leadership led to certain goals being pursued. But what then is the role of exogenous factors? One possible explanation for the divergence is that a sense of urgency mediated the influence of exogenous factors. This endogenous sense of urgency differed between the two cases, but was also linked to exogenous factors (e.g. material, socioeconomic, and institutional). For example, although Roermond suffered major flood damage, the perceived urgency of decreasing flood risk remains relatively low, whilst the urgency to increase housing capacity is high. For Venlo, the need to reduce flood risk is regarded urgent whereas increasing housing capacity is less so. The passive effects of national flood risk regulations on Roermond (building restrictions) versus the active effects on Venlo (imposed dike construction) also caused a dichotomy between the two cases in their response to these exogenous institutional factors. These findings raise intriguing questions about ‘thresholds’ of urgency in mediating collective learning in policymaking, how urgency is translated through discourse (e.g. endogenous and exogenous agenda-setting), and the sources of urgency lying with either endogenous or exogenous factors (or both).

6.2. Insights for collective learning in policymaking

The empirical findings have implications for theorizing collective learning in policymaking, and specifically for the collective learning framework (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013), in three areas: (1) the role of attention and agenda-setting, (2) the production of learning effects, and (3) the relevance of a nested conceptualization of collective learning processes.

Firstly, the role of public and political attention and agenda-setting dynamics linked to flood events (shocks) was central in triggering policymaking processes and accompanying collective learning which have since played out over two decades. This accords with central tenets of several prominent policy change theories, including the advocacy coalition framework, the multiple streams perspective, and the punctuated equilibrium model which give a central role to shifts in attention and agendas in explaining policy change (Weible & Sabatier, Citation2017). It also aligns with the importance given to exogenous shocks by scholars in environmental governance literature, such as Folke et al. (Citation2005) who emphasize the importance of learning from exogenous shocks in realizing successful governance of social-ecological systems. Overall, this reflects potential for a close affinity between the collective learning framework and other policy change theories.

However, reflecting on the products of learning raises questions about the adequacy of how this is treated in the collective learning framework. Particularly, there is an opportunity to more clearly distinguish between different forms of behavioral learning products. For example, in our cases, Roermond adapted its ‘behavior’ to cope with national regulations to advance its own policy, while Venlo integrated flood risk into municipal governance. Following various scholars who argue ‘learning may not result in improved [or new] policy outcomes’ (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013, p. 492), both types of behavioral change can be regarded as learning, but their implications for further policymaking are potentially very different. Hence the collective learning framework may benefit from elaborating on different types of (behavioral) learning products. For example, Hall (Citation1993) distinguishes three types of variables in policymaking about which can be learned: instrument settings, instrument choice, and policy goals most broadly. The idea of triple-loop learning makes a similar distinction (Pahl-Wostl, Citation2009). From another angle, May (Citation1992) identified ‘political learning’ which occurs when policymakers learn about the process behind policymaking and about ‘how to enhance the political feasibility of policy proposals’ (May, Citation1992, p. 332), suggesting a distinction between strategic behavior and a true shift in policy beliefs (Hall, Citation2011) but recognizing both as learning. Based on our empirical findings here, these aspects appear to require further clarification in the current framework.

Lastly, we suggest that a nested conceptualization of collective learning processes can be useful in analyzing exogenous factors. This helps to show (heuristically) that exogenous factors are part of an ‘active context’ within which collective learning processes are embedded. Overall, our explication of a set of exogenous factors provides a basis for ensuring comprehensive but pragmatic analysis, directing attention to potentially important exogenous factors which might otherwise be passed over.

6.3. Temporal insights

More broadly, our findings raise questions about the dynamics of exogenous factors over multiple timeframes, and what implications this may have for understanding collective learning processes. Policy scholars often highlight the role of exogenous factors on policy change and learning through exogenous shocks or crises (Folke et al., Citation2005; Nohrstedt & Weible, Citation2010; Sabatier, Citation1988). Our work demonstrates the importance of also considering the possible gradual and ongoing role of exogenous factors. For instance, demographic trends typically unfold over long timeframes. In our cases, perceived impacts of urban growth (or shrinkage) have likely influenced policymaking priorities over decades. Furthermore, although the initial response to floods was based on the specific shock experienced, it resulted in a conservative attitude of the national government towards floodplain construction which still persists today. These slow-moving variables have had a profound influence on subordinate policymaking over time. Typically, analysts treat such slow-moving exogenous variables as fixed for the purpose of analysis at any certain moment in time (Pierson, Citation2003, p. 182). However, both causes and effects of policy learning may be cumulative over time (following Pierson, Citation2003), which means that seemingly inconsequential factors can build up slowly until a threshold is reached that precipitates a seemingly rapid change. More broadly, Ostrom (Citation2007, p. 245) reminds us that factors treated as exogenous at a snapshot in time may become endogenous (in a broad sense) when analyzing change over time. In sum, this points to future considerations for the collective learning framework to take account of temporal dimensions of collective policy learning, over both short and long timeframes.

7. Conclusion

This paper responds to observations that exogenous factors are often given insufficient attention in the conceptualization, and specifically the analysis, of collective learning processes in policymaking. We argue that it is important and timely to further conceptualize and analyze the role of exogenous factors to reflect complex empirical realities and enable fuller theoretical explanations of collective learning. Working from the existing collective learning framework developed by Heikkila and Gerlak (Citation2013), we introduce a heuristic categorization of exogenous factors which assists in analyzing proximate and distal causality. We illustrate this approach through a comparative case study of municipal flood risk governance, showing how exogenous factors are interconnected with endogenous factors, and the effects this has on collective learning processes and products. The influence of exogenous factors occurs both directly (e.g. on processes of acquisition, translation, and dissemination of information), and indirectly (e.g. on institutional structure, social dynamics, and the technological and functional domain). Further, the study critically reflects on the distinction between various types of learning products, and raises questions about how best to capture the dynamics of exogenous factors over time.

Overall, the paper contributes to applying and advancing the collective learning framework, illustrating why and how exogenous factors can be accounted for in studying collective policy learning. However, the interplay between endogenous and exogenous factors, and evaluating the relative importance of each, is an area needing further work. Our heuristic framework provides a starting point for identifying exogenous factors, but may itself be expanded over time, particularly when applied in different problem domains beyond flooding. Furthermore, questions arise about the temporal dimensions of the causes and effects of exogenous factors, particularly as these may operate and change over timescales that are slow-moving or rapid in relation to policymaking. Teasing apart these aspects will require empirical work across different subnational settings and policy issues. Such an agenda could ultimately contribute to advancing policy process models that comprehensively take account of exogenous factors shaping policy learning dynamics.

Supplemental_Appendix

Download MS Word (21.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank all interviewees for their time and efforts in contributing to the research. We also thank Prof. Dave Huitema, Open University of the Netherlands, and several anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Douwe de Voogt MSc is a Guest Researcher at the Open University, Heerlen, the Netherlands. He has previously worked on the CAPFLO project for the Institute of Environmental Studies (Vrije Universiteit), addressing participatory capacity building for flood risk management, and conducted a case study for the Open University about flood risk governance in the Netherlands. This case study is part of an international comparative study by the University of Lausanne on climate change adaptation in fluvial flood risk governance. Douwe has a background in Environment and Resource Management with a focus on governance. His areas of interest include environmental policymaking and water governance.

Dr James Patterson is an Assistant Professor in Environmental Governance at the Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University, the Netherlands. His work focuses on institutional innovation and change: how and why institutions do change, and with what effects on governance systems and society? Empirical domains of application include urban climate change governance and water governance. Previously James has worked as a postdoctoral research fellow at the Vrije Universiteit and Open University, the Netherlands, and the University of Waterloo, Canada, and received his PhD from the University of Queensland, Australia.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Taking insight from the triple-loop model of learning, this visualization also implies that the outcomes of learning should (at least theoretically) have the potential to cut across all spheres (e.g. Armitage, Marschke, & Plummer, Citation2008; Pahl-Wostl, Citation2009).

2 See Appendix A (available online) for an overview of consulted archive records.

3 As of October 2017, this is the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management.

4 The urban area of Venlo consists of three city districts: Venlo with 37,000 inhabitants, Blerick (27,000 inhabitants), and Tegelen (19,000). Before the aggregation of several municipalities, including Tegelen in 2001 and Arcen en Velden in 2010, nearby municipalities with urban districts along the Meuse were previously also collectively known as the ‘City district Venlo’ (Stadsgewest Venlo) and shared a budget for local developments.

5 Early 1990s, Venlo had formulated plans for redeveloping Maasboulevard, an urban riverside stretch. Although at first the plan did not include flood risk, the floods disrupted its implementation. In 2004 the plans were reformulated and included compensatory measures for flood risk increase (H2O, Citation2004; interviewee 10).

6 However, in 1995 this buffer effect of the lakes had already been exhausted due to continuous rainfall before the peak water levels were reached (RWS, Citation1995). There is thus a somewhat false sense of security at play here.

7 Neuvel and van den Brink (Citation2009) found a similar trade-off between low perceptions of flood risk compared to the need for housing when Dutch municipalities contemplated spatial flood risk measures.

References

- Literature

- Albright, E. A. (2011). Policy change and learning in response to extreme flood events in Hungary: An advocacy coalition approach. Policy Studies Journal, 39(3), 485–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00418.x

- Armitage, D., Marschke, M., & Plummer, R. (2008). Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Global Environmental Change, 18, 86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.07.002

- Baird, J., Plummer, R., Haug, C., & Huitema, D. (2014). Learning effects of interactive decision-making processes for climate change adaptation. Global Environmental Change, 27, 51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.019

- Bennett, C. J., & Howlett, M. (1992). The lessons of learning: Reconciling theories of policy learning and policy change. Policy Sciences, 25, 275–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00138786

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cox, M. (2011). Advancing the diagnostic analysis of environmental problems. International Journal of the Commons, 5, 346. doi: 10.18352/ijc.273

- de Loë, R. C., & Patterson, J. J. (2018). Boundary judgments in water governance: Diagnosing internal and external factors that matter in a complex world. Water Resources Management, 32, 565–581. doi: 10.1007/s11269-017-1827-y

- Fleischhauer, M. (2008). The role of spatial planning in strengthening urban resilience. In H. J. Pasman & I. A. Kirillov (Eds.), Resilience of cities to terrorist and other threats. NATO Science for Peace and Security Series, Series C: Environmental Security (pp. 273–298). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P., & Norberg, J. (2005). Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annual Review of Environment & Resources, 30, 441–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511

- Gerlak, A. K., & Heikkila, T. (2011). Building a theory of learning in collaboratives: Evidence from the Everglades restoration program. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(4), 619–644. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muq089

- Gerlak, A. K., Heikkila, T., Smolinski, S. L., Huitema, D., & Armitage, D. (2018). Learning our way out of environmental policy problems: A review of the scholarship. Policy Sciences, 51(3), 335–371. doi: 10.1007/s11077-017-9278-0

- Hall, C. M. (2011). Policy learning and policy failure in sustainable tourism governance: From first- and second-order to third-order change? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 649–671. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.555555

- Hall, P. A. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275–296. doi: 10.2307/422246

- Heikkila, T., & Gerlak, A. K. (2013). Building a conceptual approach to collective learning: Lessons for public policy scholars. The Policy Studies Journal, 41(3), 484–512. doi: 10.1111/psj.12026

- Hinssen, J. (2012). Sustainability attitudes in local area development in the Netherlands. In K. Zoeteman (Ed.), Sustainable development drivers: The role of leadership in government, business and NGO performance (pp. 199–228). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Howlett, M., & Cashore, B. (2009). The dependent variable problem in the study of policy change: Understanding policy change as a methodological problem. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 11, 33–46. doi: 10.1080/13876980802648144

- Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (2002). The policy effects of internationalization: A subsystem adjustment analysis of policy change. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis; Research and Practice, 4, 31–50.

- Ison, R. L. (2010). Systems practice: How to act in a climate-change world. London: Springer.

- Keen, M., Brown, V. A., & Dyball, R. (Eds.). (2005). Social learning in environmental management: Towards a sustainable future (pp. 3–21). London: Earthscan.

- Liefferink, D., Wiering, M., Crabbé, A., & Hegger, D. (2018). Explaining stability and change. Comparing flood risk governance in Belgium, France, the Netherlands and Poland. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 11(3), 281–290. doi: 10.1111/jfr3.12325

- Marsh, D., & Rhodes, R. A. W. (1992). Policy communities and issue networks: Beyond typology. In D. Marsh & R. A. W. Rhodes (Eds.), Policy networks in British government (pp. 229–268). Oxford: Clarendon.

- Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative researching. London: Sage.

- Massey, E., Biesbroek, R., Huitema, D., & Jordan, A. (2014). Climate policy innovation: The adoption and diffusion of adaptation policies across Europe. Global Environmental Change, 29, 434–443. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.09.002

- May, P. J. (1992). Policy learning and failure. Journal of Public Policy, 12, 331–354. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X00005602

- Neuvel, J. M. M., & van den Brink, A. (2009). Flood risk management in Dutch local spatial planning practices. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 52(7), 865–880. doi: 10.1080/09640560903180909

- Nilsson, M. (2006). The role of assessments and institutions for policy learning: A study on Swedish climate and nuclear policy formation. Policy Sciences, 38, 225–249. doi: 10.1007/s11077-006-9006-7

- Nohrstedt, D., & Weible, C. (2010). The logic of policy change after crisis: Proximity and subsystem interaction. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 1(2), 1–32. doi: 10.2202/1944-4079.1035

- OECD. (2014). Water governance in the Netherlands: Fit for the future? OECD Studies on Water. OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/9789264102637-en

- Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2007). Challenges and growth: The development of the interdisciplinary field of institutional analysis. Journal of Institutional Economics, 3, 239–264. doi: 10.1017/S1744137407000719

- Ostrom, E. (2011). Background on the institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Studies Journal, 39, 7–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00394.x

- Pahl-Wostl, C. (2009). A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global Environmental Change, 19, 354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.06.001

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Penning-Rowsell, E. C., Johnson, C., & Tunstall, S. (2017). Understanding policy change in flood risk management. Water Security, 2, 11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.wasec.2017.09.002

- Pierson, P. (2003). Big, slow-moving, and … invisible: Macrosocial processes in the study of comparative politics. In J. Mahoney & D. Rueschemeyer (Eds.), Comparative historical analysis (pp. 177–207). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Reed, M. S., Evely, A. C., Cundill, G., Fazey, I., Glass, J., Laing, A., … Stringer, L. (2010). What is social learning? Ecology and Society, 15(4), r1. doi: 10.5751/ES-03564-1504r01

- Rodela, R. (2011). Social learning and natural resource management: The emergence of three research perspectives. Ecology and Society, 16(4), 30. doi: 10.5751/ES-04554-160430

- Sabatier, P. A. (1988). An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences, 21, 129–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00136406

- Schwartz, M. J. C., & Koning, A. G. H. (1995). Bestemmingsplan en waterbeheer. Het Waterschap, 15, 574–579.

- Stallings, R. A. (1988). Conflict in natural disasters: A codification of consensus and conflict theories. Social Science Quarterly, 69(3), 569–586.

- Termeer, C., Dewulf, A., Rijswick, H. V., Buuren, A. V., Huitema, D., Meijerink, S., … Wiering, M. (2011). The regional governance of climate adaptation: A framework for developing legitimate, effective, and resilient governance arrangements. Climate Law, 2, 159–179. doi: 10.1163/CL-2011-032

- van Herk, S., Zevenbergen, C., Ashley, R., & Rijke, J. (2011). Learning and action alliances for the integration of flood risk management into urban planning: A new framework from empirical evidence from the Netherlands. Environmental Science & Policy, 14, 543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2011.04.006

- Warner, J. F. (2008). The politics of flood insecurity: Framing contested river management projects (PhD dissertation). Wageningen.

- Weible, C. M., & Sabatier, P. A. (Eds.). (2017). Theories of the policy process (4th ed.). New York, NY: Westview Press.

- Wesselink, A., Warner, J., & Kok, M. (2013). You gain some funding, you lose some freedom: The ironies of flood protection in Limburg (the Netherlands). Environmental Science & Policy, 30, 113–125. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.10.018

- Wheater, H., & Evans, E. (2009). Land use, water management and future flood risk. Land Use Policy, 26S, S251–S264. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.08.019

- Wiering, M., Kaufmann, M., Mees, H., Schellenberger, T., Ganzevoort, W., Hegger, D. L. T., … Matczak, P. (2017). Varieties of flood risk governance in Europe: How do countries respond to driving forces and what explains institutional change? Global Environmental Change, 44, 15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.02.006

- Williams, R. A. (2009). Exogenous shocks in subsystem adjustment and policy change: The credit crunch and Canadian banking regulation. Journal of Public Policy, 29(1), 29–53. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X09001007

- Wolsink, M. (2006). River basin approach and integrated water management: Governance pitfalls for the Dutch space-water-adjustment management principle. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 37, 473–487.

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Policy documents

- Gemeente Roermond. (2008). Strategische visie Roermond 2020. Roermond investeert in haar toekomst. Retrieved from https://www.roermond.nl/

- Gemeente Roermond. (2015, 27 January). Proposal to Burgemeester en Wethouders of the municipality of Roermond. Subject: Initiatievenloket Maasplassen.

- Gemeente Venlo. (2014). Ruimtelijke structuurvisie Venlo: Ruimte binnen grenzen.

- Gemeente Venlo. (2015). Bouwen met Maaswater: MIRT onderzoek Maas Venlo.

- Gemeente Venlo. (2016). Koploperproject Maas Venlo. Raadsinformatiebrief. RIB nr. 2016-132. Retrieved from https://ris.ibabs.eu/raad-venlo/

- H2O. (2004). Schultz: Bouwen langs de Maas uitzondering. Retrieved from http://edepot.wur.nl/357019

- MVW (Ministerie van Verkeer en Waterstaat). (1994a). Onderzoek Watersnood Maas. Deelrapport 1, Wateroverlast december 1993. Lelystad, NL: Rijkswaterstaat.

- MVW. (1994b). Onderzoek Watersnood Maas. Deelrapport 3, Bestuurlijke aspecten. Lelystad: Rijkswaterstaat.

- MVW. (2006). Beleidslijn grote rivieren: Beleidsbrief. Letter to the chairman of the House of Representatives (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal). The Hague

- MVW, and MVROM (Ministry of Public Housing, Spatial Planning and Environmental Management). (1996). Beleidslijn ruimte voor de rivier. Staatscourant, 77, 9–12.

- Neimed. (2017). Progneff: Prognoses en effecten 2017. Retrieved from http://prognoses.neimed.nl/wat-is-progneff

- Provincie Limburg. (2015). Provinciaal waterplan Limburg 2016–2021: Samen werken aan water. Maastricht.

- RWS (Rijkswaterstaat). (1994). De Maas slaat toe. Verslag hoogwater Maas December 1993. Maastricht: Rijkwaterstaat directie Limburg.

- RWS. (1995). De Maas slaat weer toe. Verslag hoogwater Maas 1995. Maastricht: Rijkswaterstaat directie Limburg.

- Stadsgewest Venlo c.a. (1999). Maascorridor: Een integrale visie op de Maas van Belfeld tot Broekhuizen. Venlo.

- Tweede Kamer (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal). (2000). Voortgang rivierdijkversterkingen. kst18106-104. The Hague.

- Tweede Kamer (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal). (2016). Wijziging van de Waterwet en enkele andere wetten (nieuwe normering primaire waterkeringen). kst-34436-3. The Hague.