ABSTRACT

Food waste is a global societal meta-challenge requiring a sustainability transition involving everyone, including publics. However, to date, much transitions research has been silent on the role of public participation and overly narrow in its geographical reach. In response, this paper examines whether the ecologies of participation (EOP) approach provides a conceptual framing for understanding the role of publics within food waste transitions in Singapore. First the specificities of Singapore's socio-political context and its food waste management system is reviewed, before discussing dominant, diverse and emergent forms of public engagement with food waste issues. This is followed by in-depth consideration of how participation is being orchestrated by two surplus food redistribution initiatives. Our analysis finds the EOP beneficial in its elevation of participation within the transitions field. It also provides a useful means to deconstruct elements that comprise participation practices and discuss culture-specific motivations, organisational realities and visceral experiences.

1. Introduction

Food waste remains a significant challenge in the twenty-first century. It is an arena in need of a sustainability transition. However, the reduction of food waste creates a myriad of complex and intertwined challenges with social, political, economic, environmental and technical dimensions. While some of these challenges are experienced in many countries, linked to global food supply chains, others can be highly contingent on local cultures and particular histories of places. This paper widens the territorial and conceptual reach of research on food waste and responses to it by focusing on Singapore, where food waste remains an understudied topic despite becoming an issue of concern for policymakers and publics alike.

Food waste in Singapore grew by 40% between 2009 and 2019 (NEA, Citation2019a). In response, the government introduced a policy goal to become a Zero Waste Nation by 2030 in which diverting food waste from the disposal will need to play a significant role. Ong (Citation2019, p. 2) stated that in 2018 Singapore produced ‘800,000 tonnes of food waste that translates to 486 million meals a year which would allow [Singapore] to provide [food] for everyone who struggles with food security’. However, the city–state has limited infrastructure to redistribute surplus food from waste streams. It does not have a Good Samaritan Law to encourage the donation of food to charities and reduce liability for donors and there is no official definition of, or statistics on, food insecurity provided by the government (Glendinning et al., Citation2018). While government actions have been limited to supporting charitable food provision, there is an embryonic landscape of citizen-led food redistribution initiatives emerging. These initiatives stress the importance of connectivity between people and places with a focus on ICT (Information Communication Technologies) as an important technology enabling participation. This paper examines the attempts to enrol wider publics in these surplus food redistribution initiatives as a means to reduce food waste and to stimulate societal change in relation to food in Singapore.

While sustainability transitions are concerned with radical transformations of sociotechnical systems (e.g. energy, food), research in this field remains relatively quiet about the participatory processes that bring citizens closer to democratic ideals and inclusive transitions (Corsini et al., Citation2019). This is despite a longstanding interest in public participation in policy making and planning (Arnstein, Citation1969) and growing literature focusing on food waste practices and their policy implications (Schanes et al., Citation2018). In response, we draw on ethnographic research to explore the relevance of the ‘ecologies of participation’ (EOP) approach (Chilvers et al., Citation2018) for understanding food waste transitions in Singapore. In terms of defining participation in this context, we follow the argument made by Chilvers et al. (Citation2018) that public engagement in science, policy and behavioural change does not form into discrete cases, rather diverse forms of participation interrelate in wider systems. As a result, we use the term participation to refer to activities from formal participation in policy making to the diverse actions that people take in relation to food waste in their everyday lives.

Following an overview of public participation in policy-making and food waste management in Singapore, the components of, and rationale for, adopting the EOP approach to examine food waste transitions are set out. The empirical material gathered in Singapore is then discussed in relation to two key dimensions of the EOP, (i) the forms of participation in food waste management, and (ii) the orchestration of food surplus redistribution initiatives in Singapore. The paper concludes with a reflection on food waste transitions in Singapore.

2. Participation, policy and food waste in Singapore

In Singapore, participation in policy making has been largely shaped by socio-historical processes of nation-building (Chang, Citation1968). Scholars have argued that early post-independence policies from the 1970s through to the 1980s had the effect of suppressing ‘constitutive components of individual and collective identity’ (Chua, Citation1997, pp. 26–27), for example through the abolition of dialects in mass media and cultural productions in favour of the government-sanctioned languages of English and Mandarin (Chua, Citation1997), and promoting a strong achievement orientation for a competitive capitalist workforce. However, in the wake of expanding social stratification and fears of a hollow national identity in the late 1970s the Singapore government developed a Shared ValuesFootnote1 strategy in the early 1980s. The Shared Values strategy has been described as an ‘uncharacteristic promotion of an explicit national ideology’ (Chua, Citation1997, p. 30) and a ‘conscious effort to … check the insidious penetration of liberal individualism in the social body’ (Chua, Citation1997, pp. 31–32). Wee (Citation2007) summarised this period as an attempt to recreate Singapore as a modern Asian state; to shake free of the colonising legacy of Western modernity and establish ideological sovereignty. Chua (Citation1997, p. 39) has argued that Singapore's approach to creating a modern nation-state was framed as explicitly communitarian, albeit honed by market rationality, with the early decades post-independence (1970s–1990s) focused on achieving economic competitiveness.

The concept of Shared Values has been reiterated by the government sporadically since its first appearance and has been revisited in recent calls to revive a sense of Kampung Spirit in Singapore. Kampung Spirit refers to the practices of solidarity across differences, communal spirit and neighbourliness that typified pre-industrial kampungs (village/home in Malay) in Singapore. Prior to the 1980s, the focus on collective shared values in nation-building policies were criticised for ‘generating the feeling’ (Noh & Tumin, Citation2008, p. 29) of togetherness but preventing more active forms of citizenship. According to Leong (Citation2000, p. 438), ‘any discussion of citizen participation [was] inevitably linked to state domination and administrative control over the government's fragmented and underdeveloped civil society’. However, since Lee Kuan Yew stepped down as Prime Minister in 1981, a new governing class has become more interested in forms of deliberative democracy (Leong, Citation2000). In fact, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong mentioned in his inaugural speech that ‘[Singaporeans] should feel free to express diverse views, pursue unconventional ideas [… and] have the confidence to engage in a robust debate’ (Lee Hsien Loong, 2004 in Noh & Tumin, Citation2008, p. 24). As a consequence, the government has pursued a more consultative environment with a strong focus on co-creation as a ‘form of a collective enterprise, and less an elite-driven phenomenon’ (Kuah & Lim, Citation2014, p. 1) that has inspired many to use ICT to participate in environmental matters (Sadoway, Citation2013).

Formal participation in food waste policy making, however, has been primarily limited to industry, with an emphasis on maximising energy recovery from waste. Food waste is handled by the National Environmental Agency (NEA) through various channels such as collection centres, recycling bins, industrial composting, and animal feed. To promote food recycling, the NEA and the National Water Agency (PUB) have launched a series of pilot projects (2016–2018) to test the feasibility of using on-site systems to treat food waste at food markets. In 2019, the agency released positive findings that the process of co-digesting food waste and used water sludge can triple biogas yield, showing the feasibility of maximising resource recovery from food waste through co-digestion (NEA, Citation2019b). The government also launched the 2019 Year Towards Zero Waste campaign along with the nationwide recycling movement – the #RecycleRight campaignFootnote2 – to support ground-up initiatives (MEWR, Citation2019).

While there has been a turn towards more inclusive governance approaches, citizen's involvement in policy making remains limited. A few civil society groups, such as Zero Waste SG and LepakInSG, were invited to facilitate a public consultation for the Zero Waste Masterplan Singapore 2019. However, in the resulting Masterplan they are considered as education providers encouraging people to ‘recycle right’ rather than integral to, and influential within, policy-making processes (MEWR, Citation2019, p. 82). Also, participation in environmental policy making in Singapore has been limited to ‘selective groups of environmental organizations as long as they contribute to the existing power structures and regime legitimacy’ (Doyle and Simpson, 2006 in Han, Citation2017, p. 4). This means that in a tightly controlled political regime such as Singapore, civil society actors and initiatives remain marginal; effectively they are seen as targets of state-led environmental policy rather than co-designers or critics of the state's goals (Han, Citation2017).

However, elsewhere, analysts of policy change have suggested that transitions without broad public participation in its many forms will be impoverished at best (Chilvers & Longhurst, Citation2016). In the following section, we first examine how public participation has been addressed in transitions literature to date and identify the key characteristics of the EOP approach developed in the energy transitions context, we then employ this approach to examine participation in food waste management in Singapore.

3. Transitions and participation: the emergence of the EOP approach

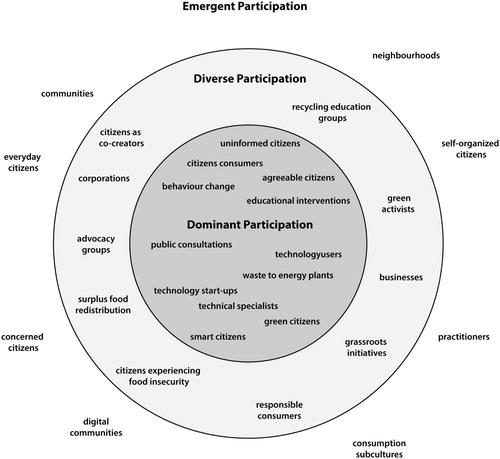

Analyses of public participation have long emphasised the varying degrees of control and power afforded to participants in policy settings, from mere tokenism to citizen control (Arnstein, Citation1969). While attending to power is an emerging feature of transitions research, matters of public participation have tended to be considered rather generically as a pre-requisite for sustainability transitions to be far-reaching, deep-rooted and effective (White & Stirling, Citation2013). Participation in sustainability transitions has variously focused on the involvement of industry, scientists and the government, but ordinary citizens are less frequently seen as key figures (Lawhon & Murphy, Citation2012). Although citizens through their everyday actions may enact practices, such as waste recycling, which are seen as pivotal for moving towards sustainability in other fields of research, the bulk of transitions scholarship has not given serious consideration to their role as agents of change (Vihersalo, Citation2017). Furthermore, where publics are examined through transitions frameworks, they are commonly seen as ‘subjects of study rather than participants in governance or innovation processes’ (Braun & Könninger, Citation2018, p. 677). This often means, as Cardullo and Kitchin (Citation2019, p. 18) have argued, that public participation in formal policy contexts is framed in a post-political way that ‘provides feedback, negotiation, participation and creation, but within an instrumental rather than a normative or a political frame’. In response, scholars have developed the ecologies of participation (EOP) approach to grasp interactions between diverse actors participating in energy transitions (Chilvers & Longhurst, Citation2016). The EOP approach gives visibility to multiple objects, subjects, and models of participation that relationally act on each other in wider socio-technical systems, through collectives defined as ‘human and non-human elements such as material and social technologies, social practices, knowledges, ideas, narratives, and modes of organising’ (Chilvers & Longhurst, Citation2015, p. 3) (). Collectives may co-exist within or beyond particular constitutional stabilities, and they have the potential to challenge dominant imaginaries by co-producing new knowledges, meanings, and forms of organising (Chilvers & Longhurst, Citation2016). As Jasanoff and Kim (Citation2015) suggest, new visions of the future can originate in the actions of individuals whose intentions, motivations and interests can be transformed into widely shared imaginaries. The orchestration of collectives; a process that involves both enrolments of publics and mediation between participants, describes the ways in which publics participate in transitions (). The focus of this paper is on emergent (citizen-driven) and diverse (corporate and charitable sectors) as key action areas in surplus food redistribution. We also acknowledge dominant participation as it is preferred by the State actors for its emphasis on technology as the primary tool of transitions in food waste management.

Table 1. The EOP components (Adapted from: Chilvers et al., Citation2018).

Although public engagement with food waste management is well established in the literature, particularly in the domestic setting (Evans, Citation2012), explicit consideration of sustainability transitions in relation to food waste remains scarce (Weymes & Davies, Citation2019). Attention has instead tended to focus on technologies and infrastructures of food waste management (Eriksson et al., Citation2015; Midgley, Citation2014). However, as the transformation of ‘surplus material’ becomes increasingly complex materially and socially, there is a need to reflect on the macro-social dynamics in which waste circulates (Bulkeley & Gregson, Citation2009; Gille, Citation2010).

Identifying and examining these complexities requires a form of research which allows a rich picture to be created, such as ethnography. While the use of ethnography in the study of food transitions remains relatively scarce (Rut & Davies, Citation2018a; Davies, Citation2019), ethnographic methods such as participant observation can deepen understanding of the macro-social relationships by drawing attention to the material, affective, and spatial performance of practices. The EOP approach explicitly recognises the value of ethnography in making sense of the ‘partiality of all forms of collective and the elements (material and otherwise) which are assembled in order for the collective to function’ (Chilvers & Longhurst, Citation2016, p. 40).

To untangle macro-social dynamics of surplus food redistribution, we first draw on Chilvers et al.'s (Citation2018) mapping of dominant, diverse and emergent participation in the energy transitions in the UK and use these categories to discuss forms of participation that influence and are influenced by the food waste system in Singapore (). Then we analyse orchestration processes within the two surplus redistribution collectives. The novelty of this task goes beyond the application of the EOP to a different transition challenge; it also broadens relational perspectives on sustainability transitions by giving attention to waste as ‘a concrete materiality and in concrete relationships’ (Gille, Citation2010, p. 1053).

Figure 1. EOP in the Singapore's food waste system context (following Chilvers et al., Citation2018).

4. Methods: researching participation in food waste transitions

This paper draws on material gathered by the lead author as part of an ethnographic study of food sharing in Singapore conducted between 2017 and 2018. Two initiatives, here referred to as a Group and a Charity to ensure anonymity, were selected as case studies because of the different forms of participation that they engender, namely diverse and emergent. Access was gained to the initiatives informally, through personal connections. It has been maintained through trust, listening and dedication. In total, fifteen interviews of an hour each were conducted with founders, employees, donors, beneficiaries, volunteers, and private individuals. The interviews covered the history, goals and evolution of the initiatives, including motivations for participating in them and the nature of activities developed. The challenges and conflicts that these initiatives face were also addressed, as well as their impact and sustainability potential. Social media platforms that the initiatives used were explored to identify the role of ICT as a tool of public participation in matters of environmental and social responsibility.

In addition to the interviews, participant observation (which included the collation of field notes, conversations and photographs) was undertaken. During participant observation, interactions were sought with participants reflecting the diversity of those involved in activities by age, gender, ethnicity, and the role they held in the initiatives. The empirical data reflects the experiences of participants aged between 20 and 60 years old, both women and men, of Chinese, Malay, Indian, and other ethnic backgrounds. The participants included those who were employed, unemployed or retired. Informal conversations were conducted with government representatives on the topic of food policies and regulations. The fieldwork data were analysed using inductive coding, where codes were assigned to segments of the participant responses and a grounded theory approach was used as a way to identify themes within the data (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1994).

5. Participation in food waste management in Singapore

5.1. Dominant forms of participation

Dominant forms of participation – defined as participation shaped by the system of which they are part – have matured in line with the internationally-recognised waste management hierarchy, often referred to in the governmental reports as ‘3Rs’ (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle) (NEA, Citation2019b). These are primarily enacted by government efforts to ‘promote responsible consumption behaviours’ (Grandhi & Appaiah Singh, Citation2016, p. 483) and advance circular industry processes mainly targeting co-digestion facilities for biogas and electricity production. Using the EOP terminology, dominant participating subjects in food waste management include citizens-consumers, the food and hospitality sector, industry, knowledge institutions, and the government. Objects of engagement are formed around technological know-how that includes material devices such as food waste digesters that facilitate high volume waste management systems, providing market-based efficiencies. The systems of food waste removal that they facilitate do not require citizens to modify their actions to reduce their food waste production, whereas the educational materials, that include visual reminders not to waste food in eating establishments aim to ‘change … [consumers] mind-sets and behaviours’ (MEWR, Citation2019, p. 3), do.

Furthermore, the emergence of large-scale technical infrastructures (e.g. waste-to-energy plants) reinforces an industrial approach to food waste management which does not discriminate regarding the different fractions of food waste as edible or not. The existence of these technical infrastructures also undermines the feasibility of alternative arrangements, particularly those involving messy, distributed and deliberative practices with diverse publics. Indeed, the government-sanctioned ecological credo of a ‘clean and green Singapore’, emphasises the role of the government as the overarching driver of transitions, with citizens’ responsibility contained by calls to act as good green subjects in accordance with that government lead. As a result, the dominant models of participation, such as educational programmes, tendering processes and industry contracts, are shaped by the image of a clean city and technologically advanced government that attracts foreign investments and business innovations.

5.2. Diverse forms of participation

Diverse participation in Singapore – defined as more marginal participatory practices than those which comprise the dominant approaches – includes practices that operate within the food waste management system but contest the focus on the techno-politics of waste management (e.g. incineration) that dominate. Diverse participation includes wider spaces of, and more active options for, public participation. It takes into consideration the whole food life cycle and incentivises dialogue between local food producers and retailers, charities, recycling groups and consumers about systemic inefficiencies that create risks, barriers and opportunities for those involved in surplus food redistribution. This has led to the development of new business models and the repurposing of food waste by-products exemplified by the social enterprises Unpackt and Ugly Food.

Diverse participating subjects include food donors, recipients, and volunteers whose involvement shifts the focus from technological fixes to active public engagement aiming at socially and environmentally responsible actions. These subjects have concerns about the impacts of food waste, the lack of city-wide food redistribution infrastructures (e.g. cold storage, transportation) and consumer obsession with food aesthetics (e.g. how food looks). Objects of diverse participation are also evident in initiatives seeking to address matters of poverty and exclusion, for example, the presence of material infrastructures such as food donation containers, communal kitchens, and community fridges are challenging to the rationale behind Singapore's incumbent social policies such as the concept of self-reliance.Footnote3 Finally, diverse models of engagement such as programmes, partnerships and community actions exist that involve corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, grassroots and voluntary welfare organisations. In some cases, these initiatives are able to inform the government about social inequalities particularly around access to food, housing and care of the most vulnerable communities.

5.3. Emergent participation

Emergent participation in Singaporean food waste matters – which incorporates forms of participation which challenge the established system – has grown with the increasing accessibility of ICT. Networking sites and applications have given citizens (at least those who can access it) a new means to connect with others (Rut & Davies, Citation2018b). Appearing on the fringes of the formal food waste management system, emergent subjects include those involved in consumption subcultures such as food scavengers, trash hunters, foragers, freegans, dumpster divers, bio-hackers and artists whose practices seek to disrupt conventional thinking about food in Singapore. Through interactions and relationships among communities, neighbours and practitioners, participants bring to the fore and connect matters of food waste to soil regeneration, sustainable diets, and the climate emergency. Objects of engagement are multiple, from community gardens and waste disposal facilities to homes and hackerspaces and from smartphones and Google Maps, to micro-blogs. Emergent participation includes self-organisation models, with human and non-human actors interacting, taking actions and making emotional connections through networks, platforms, performances, missions, and innovations. Citizens self-organising around environmental and social issues in Singapore are however far removed from the forms of protests and civil disobedience that are emerging elsewhere. Even taking ownership of projects and actions can be seen as radical in Singapore (Leong, Citation2000), as discussed in the following section on orchestrating surplus food redistribution.

6. Orchestrating surplus food redistribution: enrolment and mediation

6.1. Group

The Group emerged in 2017 as a result of dumpster diving activitiesFootnote4 with a mission to rescue and redistribute ‘unwanted food to whoever is willing to consume it, not just to the needy’ (Co-founder, Group). Initially, the enrolment of participants, took place during ad-hoc ‘veggie hunts’ actions of salvaging unsellable food from the Little India wet market.Footnote5 Participants include individuals between the ages of 18–60, with a particular preponderance of students, mothers working in the home and retired female citizens, alongside charities (who receive surplus food) and vendors and wholesale distributors (who donate unsold food). Participants can select 10% of rescued food in recompense for their free labour.

In 2018 the Group claimed to save between 2 and 3 tonnes of fresh produce every week, despite operating without transportation and cold storage. Also, the Group does not own its own equipment. Trolleys and boxes which are used to move surplus from bins and food stalls to the collection points are shared with the vendors. As such, the Group makes use of shared resources to build an adaptable infrastructure. In doing so the Group relies on personal networks and the kindness of strangers to maintain its operational capacity.

Participants enrolled in the Group can take up the roles of organisers, drivers, stackers, communication leaders, trolley and basket managers. While some participants are assigned to roles because of their physical strength, others can also self-enrol in activities by joining events as ‘observers’ and ‘newbies’. Food vendors are enrolled informally during food rescue actions and charities are approached by the Group via email, phone or in person. Beyond the formal roles required to function, the Group provides space for participants to design activities themselves:

[Participants] don't have to ask the leader - tell us what to do! … some are good at initiating things and some have certain type of resources … there is an avenue for them to contribute in some way … (Participant, Group)

Furthermore, during the participatory moments that the Group provides such as rummaging through bins, feeling dirtiness on the skin from dumpster diving, and encountering others such as street cleaners and garbage collectors, migrant workers and vendors, participation nurtures intrinsic experiences that cross-cultural, legal, moral and material boundaries. For example, in the act of asking vendors for unwanted items, participants confront disapproving looks, questions, and narratives (of waste as bad, and the recipient who does not pay as destitute) inspiring a re-evaluation of social taboos around food. Through such experiences, participants also become aware of food system controversies such as the scale of illegal food imports that permeate Singapore food markets, as mentioned by the co-founder in a public post:

We have learned from wholesalers that importing vegetables without a permit is a common practice … that we are consuming illegally imported food without realising it … . [and] smuggled food [comes with a] higher level of pesticides. (Co-founder, Group)

I put food at the block, and then aunties and uncles on wheelchairs they come. They don't have the luxury of buying vegetables … I better give food to those who are old and cannot dumpster-dive so they can cook and eat with their families. (Participant, Group)

Collection points attract transient publics hopping on and off the metro into vegetable stalls, hawker centres and coffee shops. People come by randomly, glimpse at the boxes full of rescued papayas, bananas, curry leaves, and snake beans. Some try to start a conversation, looking confused at this unusual public gathering. (Fieldwork notes, Group)

Furthermore, the way in which food and bodies intersect spatially in the performance of food rescue also arouses an embodied awareness that provides a stimulus for participants to be reflexive about one's own capacity to participate in local sustainability actions. As one participant mentioned:

it is a new culture … [a] learning journey for me … Singapore … cannot function alone by the government … you have to have self-groups to come in and help. (Participant, Group)

We are not leaning towards … [a] sustainability movement … food is something that we all relate to but sustainability, and the jargon around it, not so many people will be attracted to it, lots of people will be turned off. (Participant, Group)

ICT is also crucial when it comes to mobilisation of resources across diverse food rescue spaces. This is illustrated in the statement below which recounts how ICT was used to rapidly mobilise collection of a surplus that suddenly came to light:

Someone tipped us off … within the WhatsApp chat group, Food Rescuers stepped forward, offering their transport service and fridge space. Within an hour, we cleared both [food] pallets. (Co-founder, Group)

There are some people … maybe distressed or depressed … food rescue helps because you have a higher purpose … to be able to help other people … and then you might [connect to] like-minded people … all these helps and some people will leave the WhatsApp chat groups, but for people who are able to reach through it is therapeutic and healing. (Participant, Group)

6.2. The Charity

The Charity was established in 2012 as a philanthropic arm of a food distribution company. It has the status of an Institution of Public CharacterFootnote8 and offers tax breaks to corporate donors. The Charity is located in the company headquarters, in a commercial property that is not easily accessible to the public. It shares storage and office space with the founding company, providing a level of physical infrastructure and human resources. As mentioned in an interview with the co-founder:

… donors [prefer] to work with us because, [we] can accept bigger amount of donations, [we] have trucks, and a warehouse. (Co-founder, the Charity)

The Charity is comprised of other collectives such as family service centres, care homes, religious associations, and universities, schools, and corporations. Participants from these collectives are enrolled as recipients and donors by the signing of a liability agreement. In the absence of the Good Samaritan Law, the liability agreement releases the donors from the moral responsibility of having to consider health-related risks before donating surplus. This also shifts the power structure around enrolment in favour of the corporate donors. As one employee of the Charity puts it, ‘we don't reject anything because we don't want to push donors away … We want to take as many donations as possible’ (Employee, Charity).

However, such a focus on optimising donations can lead to challenges in terms of downstream redistribution, particularly in relation to religious dietary requirements, cultural norms and social values, as explained by a food recipient:

We serve Muslim families … sometimes when the [Charity] has food that is near expiry … we would love to take it but because it is not halal we can't just force [it upon beneficiaries]. (Recipient, Charity)

A few programmes run by the Charity, such as door-to-door donations, allow the volunteers to access households experiencing food insecurity and collect information on their composition and dietary preferences. Collected information is then eventually used by the Charity to design wholesome donations programmes that are meant to support healthy eating habits amongst the most vulnerable:

[Healthy food packages includes] vegetables, lactose-free milk, olive oil, oats. It is to teach them that to eat healthier does not need to be expensive but it's just about maybe putting a bit of corn into noodles or a bit of tuna or sardines into meal. Just a bit more thoughtful of how they consume. (Co-founder, the Charity)

Every day [a donor] has four to five pallets of organic vegetables, yoghurts, milks … [We] have a WhatsApp chat group and we match [donors with] beneficiaries … [beneficiaries] will go directly to [the donor] and pick up the items. (Cofounder, Charity)

market [the Charity] like a company … [as] we have to keep fresh in the donors’ mind and into the corporates’ minds so that they keep coming back. So that's why we always need to have new [social media] projects going. (Co-founder, Charity)

7. Discussion

Over the past decade, the food waste sector in Singapore has been in a phase of early transition. The policy goal of the 2019 Year of Zero Waste and the Zero Waste Masterplan is to efficiently close resource loops, and this, combined with a strong commitment to technological solutions and the cleanliness culture of the ‘City in a Garden’, is shaping Singapore's formal vision for moving towards low food waste futures. In applying the EOP approach, we were interested in digging beneath these narratives and understanding who participates in food waste management in Singapore, how, why, and in which way.

The EOP analysis shows that the collectives examined in the paper are orchestrated in different food waste contexts; corporate philanthropy (Charity) and grassroots food rescue (Group). The Charity is shaped by prescribed set of rules that are tailored to align with, rather than disrupt, the dominant system. Enrolment is managed in a linear manner in which models of participations are pre-given, as participants perform their duties as donors, recipients or volunteers (mostly middle-aged, employed and young students). Participation is defined by a spatial locus, with specific tasks to be completed at assigned private locations. The Group, in contrast, adopts organic forms of engagement in which participation is sustained through the interaction with strangers, material resources and spaces and places of food waste production. People in all walks of life and occupational status (e.g. students and retired citizens, freelancers, entrepreneurs and unemployed) are drawn into food rescue actions. The Group also creates a multitude of social ties built around shared intentions, concerns and emotions which supports a feeling of communal identification. While the political establishment has rhetorically made place-based emotional and social affiliation a goal through its push for a revitalisation of Kampung spirit, the mode of orchestration practiced by the Group demonstrates how such affiliation might be effectively constructed. Also, while the Charity has used ICT to administer food donations, the Group harnessed the ubiquity of mobile phones and high connectivity between the users to increase spontaneous participation (especially among young adults) across food rescue spaces and time scales.

The access to the food waste spaces in which collectives operate also influences who is included in surplus redistribution practices, and how. The ad-hoc rescue actions of the Group are directed at saving large amounts of a few types of fruit and vegetables that are made available at wholesale markets. As a result, the self-organised model works well for household collectives whose participants see waste as a resource while collecting fresh produce that meets their taste preferences. However, this form of participation might become problematic for charities and food insecure households if there is insufficient food to meet healthy and culturally-specific dietary needs. Thus, structured participatory models such as the Charity that offer stable donations are preferred by collectives with reduced mobility and limited or no access to cooking facilities to process raw vegetables.

Our EOP analysis also suggests that self-organised models of participation may enable moves towards emancipatory practices such as civic engagement in food waste reduction. For example, the participants of the Group drew largely on the ideas and forms of experiential knowledge that are co-produced as spaces of food waste and bodies (and their affective dimensions) intersect. Experiential knowledge, such as the perception of food edibility, and the feeling of shared actions and emotions that the ordinary citizens co-produce through new learning journeys and soft skills, help to maintain collective responsibility and inspire new socio-technical imaginaries. While observing the practice of rescuing food from waste as a process of negotiation between diverse motivations and socio-material elements (e.g. waste, community fridges, food sharing points, mobile phones) it was possible to trace new social imaginaries that are mobilised to increase public participation in food waste transitions. We demonstrated that the models of participation that are closer to the local cultures and informal practices are more likely to manifest gentle expressions of disagreement with hierarchies of waste management and technological credo. They can also inspire new imaginaries which envisage different consumption paradigms with empowered citizenry, adaptive infrastructures, and sustainable lifestyles.

However, being a flow of shared goals and desires, new socio-technical imaginaries emerge and stabilise differently across diverse political cultures and waste regimes (Gille, Citation2007). Although governmental agencies have recently involved civil groups in a dialog about reducing waste, the collectives have not yet proliferated enough to demonstrate the tangible benefits of their actions to the government (besides the aspect of community-building). Thus, their presence remains on the periphery of the dominant political processes. While the top-down technocratic pragmatism has resulted in remarkable policy outputs, such as the reduction of pollution and waste (Han, Citation2017), it also distracts from the critical role of citizen-led political action, leading some to suggest that sustainability transitions require strong democratic societies that are capable of radical transformations (Corsini et al., Citation2019). In Singapore, the longstanding (albeit still evolving) state-citizen relations mean that radical action currently remains on the fringes of society and is relatively invisible for many in the public sphere. The Group's emergent qualities are therefore manifest in its support for unfamiliar citizen-led behaviours in public spaces, ‘caring equally for autonomous agency and the social collectivity’ (Stirling, Citation2015, p. 30). As one participant suggested, food waste transitions in Singapore might involve realising the democratic potential of citizens:

We have a lot of [political] fencing around, finding some crack in the fencing to come up and hopefully nobody discovers, so we are testing. People are quite afraid, is this against the law what we are doing? [We] don't have confidence yet. I think we need to boost our confidence level higher. (Participant, Group)

8. Conclusions

This paper provides a novel view on the nature, structuring and practice of participation in surplus food redistribution as a means to reduce food waste in Singapore. The EOP approach has made possible the identification of diverse food waste reduction practices, from policy programmes and infrastructures of waste management, to informal food rescue activities that are gathering pace in Singapore. Furthermore, the use of an ethnographic lens has shed light on the heterogeneity of food waste management in Singapore and allowed greater exploration of the EOP components through the integration of culture-specific motivations, material and organisational realities and visceral experiences.

Our analysis suggests that positive experiences of participating in surplus food redistribution can gently challenge the meanings, practices and hierarchies of dominant food waste imaginaries by increasing citizens’ engagement in co-creating alternative visions and practices to technocratic solutions. There is, however, a clear need to explore the impact of participation in surplus food redistribution initiatives on citizens’ sense of agency and empowerment over longer timescales. Longitudinal research following the fortunes of the case studies and the forms of participation they foster would provide a richer picture of participation in the making. There are also outstanding questions about whether there are significant differences between participation dynamics in different sectors undergoing sustainability transitions. Finally, more attention to cultural dynamics – which result from local histories, community relations, shared imaginaries and care practices that influence the way actor's collectives shape future visions and actions – is needed to enrich our understanding of sustainability transitions globally.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank participants to food sharing initiatives in Singapore for sharing their experiences and time with me. We are very thankful to the Co-Editor of this journal, for providing constructive suggestions during the preparation of the manuscript and three anonymous reviewers whose insightful comments have guided the development of this paper. Title: SHARECITY: The practice and sustainability of urban food sharing. Award No: 646883. We are extremely grateful for this support without which the research could not have taken place.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Monika Rut is a researcher and practitioner interested in sustainable food systems, transitions and cultural and social change. Her research explores grassroots innovations and sustainable food transitions in Singapore. She is a PhD student at Trinity College Dublin and co-founder of Virtuale Switzerland, an augmented reality art festival.

Anna Davies is Professor of Geography, Environment and Society at Trinity College Dublin and the Principal Investigator of SHARECITY. A specialist in environmental governance and sustainable consumption, Anna advises the Irish Government as a member of the National Climate Change Council and is also a member on the board of The Rediscovery Centre, a social enterprise that is the national centre of excellence for the circular economy and the International Science Council, which seeks to advance science as a global public good.

Huiying Ng is a researcher-practitioner exploring links between urban agriculture, open/welcoming spaces for new imaginations of urban life, and community resilience. Her research focuses on sustainable modes of agricultural production and agroecological learning networks, particularly in Southeast Asia. She has a Master in Social Sciences (Research) from the Department of Geography, National University of Singapore, and is a founding member of the Foodscape Collective, and TANAH, a nature-food duo, and a member of soft/WALL/studs.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Shared Values refers to five statements with the goal of forging national identity: nation before community and society before self; family as the basic unit of society; regard and community support for the individual; consensus instead of contention; racial and religious harmony (Tan, Citation2012).

3 The concept of self-reliance focuses on the individual as primarily responsible for its own social and economic welfare and family as the first line of support before requesting the Government for social or economic assistance.

4 Spontaneous acts of saving food that was thrown by vendors in to the bins.

5 Little India is an ethnic district in Singapore.

6 Selfish, self- centred behaviour.

7 Food redistribution points usually arranged spontaneously in the common public areas such as streets, void-desks etc.

8 Institutions of a Public Character (IPCs) are exempt or registered charities which are able to issue tax deductible receipts for qualifying donations to donors.

References

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Bosco, F. J. (2006). The Madres de Plaza de Mayo and three decades of human rights’ activism: Embeddedness, emotions, and social movements. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 96(2), 342–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2006.00481.x

- Braun, K., & Könninger, S. (2018). From experiments to ecosystems? Reviewing public participation, scientific governance and the systemic turn. Public Understanding of Science, 27(6), 674–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662517717375

- Bulkeley, H., & Gregson, N. (2009). Crossing the threshold: Municipal waste policy and household waste generation. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 41(4), 929–945. https://doi.org/10.1068/a40261

- Cardullo, P., & Kitchin, R. (2019). Being a ‘citizen’in the smart city: Up and down the scaffold of smart citizen participation in Dublin, Ireland. GeoJournal, 84(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-018-9845-8

- Chang, D. W. (1968). Nation-building in Singapore. Asian Survey, 8(9), 761–773. https://doi.org/10.2307/2642643

- Chilvers, J., & Longhurst, N. (2015). A relational co-productionist approach to sociotechnical transitions. Science, Society and Sustainability (3S) Research Group Working Paper, University of East Anglia.

- Chilvers, J., & Longhurst, N. (2016). Participation in transition (s): Reconceiving public engagements in energy transitions as co-produced, emergent and diverse. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 585–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1110483

- Chilvers, J., Pallett, H., & Hargreaves, T. (2018). Ecologies of participation in socio-technical change: The case of energy system transitions. Energy Research & Social Science, 42, 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.03.020

- Chua, B. H. (1997). Communitarian ideology and democracy in Singapore (Vol. 9). Psychology Press.

- Corsini, F., Certomà, C., Dyer, M., & Frey, M. (2019). Participatory energy: Research, imaginaries and practices on people’contribute to energy systems in the smart city. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 142, 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.07.028

- Davies, A. R. (2019). Urban food sharing: Rules, tools and networks. Policy Press.

- Eriksson, M., Strid, I., & Hansson, P. A. (2015). Carbon footprint of food waste management options in the waste hierarchy–a Swedish case study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 93, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.01.026

- Evans, D. (2012). Beyond the throwaway society: Ordinary domestic practice and a sociological approach to household food waste. Sociology, 46(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511416150

- Gille, Z. (2007). From the cult of waste to the trash heap of history: The politics of waste in socialist and postsocialist Hungary. Indiana University Press.

- Gille, Z. (2010). Reassembling the macrosocial: Modes of production, actor networks and waste regimes. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(4), 1049–1064. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42122

- Glendinning, E., Shee, S. Y., Nagpaul, T., & Chen, J. (2018). Hunger in a food lover’s paradise: Understanding food insecurity in Singapore. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=lien_reports

- Grandhi, B., & Appaiah Singh, J. (2016). What a waste! A study of food wastage behaviour in Singapore. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 22(4), 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2014.885863

- Han, H. (2017). Singapore, a garden city: Authoritarian environmentalism in a developmental state. The Journal of Environment & Development, 26(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496516677365

- Jasanoff, S., & Kim, S. H. (2015). Dreamscapes of modernity: Sociotechnical imaginaries and the fabrication of power. University of Chicago Press.

- Juris, J. S. (2008). Performing politics: Image, embodiment, and affective solidarity during anti-corporate globalization protests. Ethnography, 9(1), 61–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138108088949

- Kuah, A., & Lim, S. H. (2014). After our Singapore conversation: The futures of governance. Ethos (berkeley, Calif ), 13, 18–23.

- Lawhon, M., & Murphy, J. T. (2012). Socio-technical regimes and sustainability transitions: Insights from political ecology. Progress in Human Geography, 36(3), 354–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511427960

- Leong, H. K. (2000). Citizen participation and policy making in Singapore: Conditions and predicaments. Asian Survey, 40(3), 436–455. https://doi.org/10.2307/3021155

- MEWR. (2019). Zero Waste Masterplan Singapore. https://www.towardszerowaste.sg/images/zero-waste-masterplan.pdf

- Midgley, J. L. (2014). The logics of surplus food redistribution. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 57(12), 1872–1892. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2013.848192

- NEA. (2019a). Food waste management. https://www.nea.gov.sg/our-services/waste-management/3r-programmes-and-resources/food-waste-management

- NEA. (2019b). Co-digestion of food waste. https://www.nea.gov.sg/media/news/news/index/co-digestion-of-food-waste-and-used-water-sludge-enhances-biogas-production-for-greater-energy-generation

- Noh, A., & Tumin, M. (2008). Remaking public participation: The case of Singapore. Asian Social Science, 4(7), 19.

- Ong, A. I. (2019, February, 12). Legislating food waste. We can do more. https://medium.com/@antheaindiraong/legislating-food-waste-we-can-do-more-2b711ec9be6c

- Rut, M., & Davies, A. R. (2018a). Transitioning without confrontation? Shared food growing niches and sustainable food transitions in Singapore. Geoforum, 96, 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.07.016

- Rut, M., & Davies, A. R. (2018b). Sharing foodscapes: Shaping urban foodscapes through messy processes of food sharing. In Messy ethnographies in action (pp. 167–175). Wilmington, DE: Vernon Press.

- Sadoway, D. (2013). How are ICTs transforming civic space in Singapore? Changing civic–cyber environmentalism in the island city-state. Journal of Creative Communications, 8(2-3), 107–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973258613512576

- Schanes, K., Dobernig, K., & Gözet, B. (2018). Food waste matters-A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 978–991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.030

- Stirling, A. (2015). From controlling ‘the transition’ to culturing plural radical progress. The Politics of Green Transformations, 54–67.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1994). Grounded theory methodology. Handbook of Qualitative Research, 17(1), 273–285.

- Tan, C. (2012). “Our shared values” in Singapore: A Confucian perspective. Educational Theory, 62(4), 449–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2012.00456.x

- Vihersalo, M. (2017). Climate citizenship in the European Union: Environmental citizenship as an analytical concept. Environmental Politics, 26(2), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2014.1000640

- Wee, C. L. (2007). The Asian modern: Culture, capitalist development, Singapore (Vol. 1). Hong Kong University Press.

- Weymes, M., & Davies, A. R. (2019). [Re] Valuing surplus: Transitions, technologies and tensions in redistributing prepared food in San Francisco. Geoforum, 99, 160–169.

- White, R., & Stirling, A. (2013). Sustaining trajectories towards sustainability: Dynamics and diversity in UK communal growing activities. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 838–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.06.004