ABSTRACT

Understanding environmental politics is crucial for sustainability transitions. We study the transition politics of the shift to a circular economy in the German packaging sector, particularly the curious case of the 2019 German Packaging Act. While the policy was born out of the unanimous wish for radical regulatory change, all actors evaluate the outcome as incremental. Following the Discursive Agency Approach and drawing upon actor interviews and documents, we show that actors’ perceived fears of radical changes are critical for transition politics. This fear created a lock-in of two narratives, proposing conflicting organizational designs of packaging waste management. While the narrative lock-in was resolved by trading radical for incremental change, it left many conflicts and challenges unresolved. Our findings suggest that actors’ fears not only prevent radical regulatory change but also create incremental change that may intensify unresolved conflicts and, thus, further weaken the actors’ capacities for future transition politics.

1. Introduction

To achieve sustainability transitions in all parts of our society, it is of crucial importance to understand the political dynamics of transition processes (Köhler et al., Citation2019; Patterson et al., Citation2017). The role of discourse and agency are seen as critical for transition politics and in response to scholarly critiques, such as Kern (Citation2015), Meadowcroft (Citation2011), and Smith and Stirling (Citation2010), transition literature has elaborated on its understanding of these concepts (Loorbach et al., Citation2017). However, as transition research is still a young scholarly field, most scholars focus on conceptual approaches of politics in transition (see Avelino et al., Citation2016; Avelino & Wittmayer, Citation2016; Duygan et al., Citation2019; Fischer & Newig, Citation2016). So far, the empirical understanding of political dynamics and its relation to discourse and agency is limited to a few well-versed transition processes, such as the energy transition (Grin et al., Citation2011), or selected cases, such as wastewater management in the Netherlands (Ampe et al., Citation2019). To enhance the scholarly understanding of transition politics, as well as the role of agency and discourse in this matter, more empirical studies are needed (Köhler et al., Citation2019).

One sustainability transition that has recently received much political and media attention is the circular economy. Based on the intention to radically shift away from unsustainable patterns of production and consumption, this concept is now present in many supra-national and national policy contexts (Kirchherr et al., Citation2017). A core component of the transition to a circular economy is an alternative approach towards waste products, where ‘the value of products, materials, and resources is maintained in the economy for as long as possible, and the generation of waste is minimized’ (European Commission, Citation2015). Although the circular economy concept is widely discussed in the political arena, its implementation on a large scale faces many challenges. Scholars attribute the limited progress to a circular economy to a variety of cultural, regulatory, market and technological barriers (de Jesus & Mendonça, Citation2018; Kirchherr et al., Citation2018; Leipold & Petit-Boix, Citation2018; Ritzén & Sandström, Citation2017). To overcome these barriers various scholars suggest that new circular economy policies, building on the willingness of the actors to make a change, can solve current issues and enhance the circular economy paradigm (among others de Jesus & Mendonça, Citation2018; Hartley et al., Citation2020; Kirchherr et al., Citation2018). To substantiate this suggestion, the political dynamics in policymaking and implementation processes of a new circular economy policy form an interesting area of research.

An important sector discussed under a circular economy perspective is post-consumer waste management. Despite the public attention this receives, the waste management sector’s transition to a circular economy and its political dynamics have received surprisingly little attention in scholarly literature so far (Duygan et al., Citation2019). To enhance the empirical understanding of circular economy transition politics in the waste management sector, we study the policy discussions and outcome of the 2019 German Packaging Act. Germany represents an all-too-familiar case, where all actors involved called for a transition to a circular economy in the packaging sector through an ambitious new regulation with radical changes for sustainability. However, from the perspective of the actors, the policy outcome brings merely incremental change.

To enable solid empirical insights into the role of discourses and agents in this case of transition politics, we build on the Discursive Agency Approach (DAA) (Leipold & Winkel, Citation2017). With this focus, our approach differs from established studies of policy narratives, which have given little systematic attention so far to influential discursive agents and the use of their strategic practices (Lang et al., Citation2019; Leipold et al., Citation2019). By analyzing the agents’ perspectives on the policy discussions and their outcome, we aim to generate an elaborated empirical understanding of political dynamics shaping the transition to a circular economy in the German packaging sector. The study poses three research questions:

How can the policy discussions and outcome of the German Packaging Act be explained?

How is the policy outcome evaluated and what does this suggest regarding the desired transition in the German packaging sector?

What insights can we generate from this case for circular economy transition politics and research?

Overall, the paper contributes to closing empirical gaps regarding the German packaging sector’s transition to a circular economy as well as strengthening the understanding of transition politics. The results contribute to current knowledge on barriers preventing the institutionalization of radical transition policies for sustainability as well as what a focus on incremental change may mean for future transition politics. We hope that the findings will stimulate further theoretical discussions in research on the circular economy and sustainability transitions.

2. Theoretical framework

To understand the political dynamics that have shaped the German Packaging Act, we analyze the case using a discursive lens. Discourse analysis has its origin in the school of social constructivist approaches, taking a critical stance towards claims of single rationality and objective truth while focusing on language, knowledge, and their implied power relations (Feindt & Oels, Citation2005). By focusing on the way society gives meaning to a subject through language, discourse analysis can illuminate the discursive structures, including value concepts, assumptions, and judgments, which shape the discussion (Dryzek, Citation2013). In practice, discussions are often struggles over the dominant discourse on a topic, as this will inform the actions that shape the social and physical world (Hajer & Versteeg, Citation2005; Sharp & Richardson, Citation2001).

Environmental problems and their policy solutions are often complex as they involve many actors and different perspectives (Sharp & Richardson, Citation2001). In this way, environmental policymaking forms a continuous struggle over interpretations and the search for political truth – or, the dominant discourse (Lang et al., Citation2019). A discourse analysis enables us to explain why certain policies are or are not, adopted within a certain time frame (Hajer & Versteeg, Citation2005). Furthermore, the packaging sector entails many actors, with as many perspectives on how sustainable and circular waste management should look. Discourse analysis provides a suitable approach to disentangle the different perspectives and to create an understanding of how the policy discussions, process, and outcome have been shaped.

Transition research has increasingly used discourse analysis as a method to generate insights into the underlying socio-political dynamics of transition processes (Kern, Citation2015; Roberts & Geels, Citation2018; Rosenbloom, Citation2018). Although this research has contributed to understanding the role of actors and discourses, supporting empirical evidence – especially in the realm of environmental politics – remains underrepresented in the transition literature (Köhler et al., Citation2019). Strengthening conceptual and empirical relations between existing discursive approaches and transition research can enhance understandings on political dynamics in environmental policymaking as well as in transition politics.

To analyze the case of the German Packaging Act, we build on the Discursive Agency Approach (DAA) of Leipold and Winkel (Citation2017), an interpretative heuristic which has already delivered novel insights for several cases of environmental politics (Albrecht, Citation2018; Lang et al., Citation2019; Leipold & Winkel, Citation2016). The DAA combines existing analytical concepts such as Hajer’s (Citation2006) storylines and discourse coalitions with new analytical elements to make discursive agency accessible for empirical analysis. ‘In line with other interpretative discourse approaches, the DAA understands policymaking as a process of agents struggling to establish their particular political truth’ (Leipold et al., Citation2016, p. 295). The approach assumes that it is the goal of every actor to become a relevant speaker in the debate, thereby becoming a discursive agent, and with the help of various strategic practices to generate a dominant narrative, institutionalized in the final policy outcome. ‘The DAA hence analyses policymaking through the eyes of involved stakeholders and attempts to understand how their interpretations develop a collective logic and dynamic – the discourse – that shapes political outcomes and implementation practices’ (Leipold & Winkel, Citation2016, p. 295).

To be sure, diverse positivist policy analysis approaches focus on actors and different strategic practices. These, however, are unsuitable to analyze the role of narratives in transition processes as they miss important information on how the discursive struggle among different narratives is shaped by the use of strategic practices. This understanding is crucial to explain how the actors shape the policy discussions and outcome.

3. Materials and methods

To identify the narratives and discursive agents shaping the German Packaging Act, the study analyzed data of in-depth semi-structured interviews with key actors involved such as political entities, industries, and non-governmental organizations. To identify the influential actors, initial desk research was conducted looking into policy documents of the German Environmental Agency and the Central Agency Packaging Register (CAPR). Based on these documents, we identified interviewees that could provide information on the complete timeframe of interest, from the start of the policymaking process until its implementation. Participant lists of the first participation process in 2011 were compared with representatives of the different organizational committees of the CAPR. In this way, 20 relevant actors were identified. This list was verified on completeness during the interviews, which led to three additional interview requests.

Overall, the willingness to contribute to this study was high and we executed 18 in-person or phone interviews (45–90 min each) in the period from April to May 2019. To assure the interviewees’ anonymity in this study, we aggregated the interviewees in actor groups, aligned with the grouping in the committees of the CAPR. Those interviewees who did not belong to any actor group are called ‘Experts’. Appendix A holds an overview of the number of interviews per actor group and the reference (from I-1 to I-18) as it is used in the results of this study. With this selection method, we assumed that the interviewees reproduce a similar narrative as the organization or actor group they represent. To counteract potential bias, we complemented the interviews with documents mentioned by the interviewees as important to understand their perspectives and actions. This led to the additional analysis of eight documents (see Appendix B).

Both interview and document data were coded and analyzed deductively guided by the four interrelated analytical elements of the DAA: (1) Discourses (including particular narratives), (2) Institutions, (3) Discursive Agents, and (4) Strategic Practices. First, to map and understand the role of institutionalized elements for the development of the political process, we described the historical context (see results 4.1) as well as the policy outcome (see results 4.5), based on existing literature and interviewees’ perspectives. Second, we analyzed the interviews and documents to identify which actors the interviewees perceive as influential discursive agents in the policy discussions, based on the personal and positional characteristics that are attributed to them (see results 4.2). Additionally, we built on the interviews and documents to outline the discursive agents’ discourses and related narratives. To do so, we examined their understanding of the policy problem, suitable solutions, and consequences of the policy process and outcome (see results 4.3, 4.4, and 4.6). Related to the discourses are the strategic practices (indicated by italics in the results) used by the discursive agents to strengthen their narratives and to shape the policy discussions. Also here, we built on the interviewees’ interpretations of the political dynamics that shaped the policy process and outcome (see results 4.3, 4.4, and 4.6). Next to deductive coding, following insights from Boyatzis (Citation1998) and Braun et al. (Citation2012), the data was coded inductively, while focusing on contextual or new insights relevant for the research questions of this study.

To be sure, the design of this study builds on the interpretation of the researchers of the perspectives presented by the interviewees. The use of abstract concepts such as ‘circular economy’, ‘radical shifts’ or ‘incremental policy change’ emerges entirely out of the interviewees’ statements or documents and are not defined or evaluated by the authors. Furthermore, we acknowledge that alternative interpretations of the data are possible. Nevertheless, discussions with interviewees on an earlier draft of the study support the interpretation of the discursive struggles and political dynamics presented here.

4. Results

4.1. The policy problems

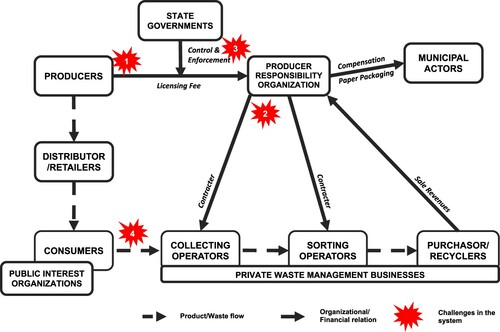

To study and explain the policy process and outcome, we first map the historical developments as well as the organizational and institutional setting of the German packaging waste management system that triggered the need for a new regulation (see , based on Rasek and Smuda [Citation2018]). An understanding of this context is crucial to analyze the other discursive elements – agents, discourses, and strategic practices – that shape the political process. Since the adoption of the German Packaging Ordinance in 1991, packaging waste management has shifted to a system of extended producer responsibility (EPR), where the producers of packaging also finance its end-of-life (Eichstädt et al., Citation1999). With this shift, the collection, sorting, and recycling of packaging waste was now organized separately from non-packaging solid waste streams (i.e. paper, bio, residual and bulky waste), for which municipalities are responsible.

The EPR system builds on the idea that packaging producers pay a licensing fee to a Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO) for organizing the waste management of the packaging product. The amount of this licensing fee depends on the volume, weight, and material type of the packaging and corresponds with the costs of organizing its end-of-life (Bailey, Citation2003). Controlling this contract between producers and PROs is the responsibility of the State Governments (Bundesländer), who – in cases of freeriding practices – enforce fees or other forms of punishment.

Once the packaged product has reached the consumer, via the retailer, private households are encouraged to separate the packaging waste into the appropriate bins for paper, glass or lightweight packaging (i.e. plastic, aluminum, ferrous metals, beverage carton packaging, and other composites). The latter is usually referred to as the ‘yellow bin’ (Gelber Sack/Gelbe Tonne). A local operator collects the packaging waste and brings it to the sorting facility, where the different materials are separated. Both the collecting and sorting operators are hired by the PRO. In the last step of the process, the PRO sells the materials for recycling or recovery. As paper packaging is jointly collected with other paper waste – which is organized by the municipalities – the PROs pay the Municipal Actors a financial compensation for their efforts.

Since its implementation, the content and effectiveness of the German Packaging Ordinance has been discussed in the political realm (Baum, Citation2014). These discussions have resulted in seven amendments, targeted at implementing new European legislation as well as solving financial problems in the system (Flanderka & Stroetmann, Citation2012). Nevertheless, demographic and social changes, such as the increase of smaller households, e-commerce, and to-go consumption, have challenged the system, leading to a negative public perception on the sustainability of the packaging waste management system (Schüler, Citation2018). In particular, the system’s performativity was perceived by the agents to be threatened by four challenges (indicated as red stars in ):

Freeriding by under-licensing (i.e. producers license less packaging than they bring on the market) or non-licensing (i.e. producers license no packaging at all) of the packaging producers;

Freeriding by profit-oriented illegal practices of the PROs (e.g. receiving payments without delivering the waste management service), leading to waste management problems.

A lack of strong enforcement by State Governments to deal with the freeriding practices of either Producers and Distributors or PROs due to limited resources.

Consumer’s inability to separate the waste correctly, resulting in low recycling quotas and low recycling quality.

Overall, all actors involved in the packaging waste management system agreed that these challenges had become increasingly difficult to address with ‘small fixes’ or amendments and that a more radical regulation that supports the systems’ environmental performance was needed.

4.2. The main discursive agents

After mapping out the institutional context and initial situation of the policymaking process (see results 4.1), we analyzed which of the actors were perceived as discursive agents and therefore influenced the policymaking process. Based on interviewees’ references to the role played by themselves and others, we identify six main agents with strong personal and positional characteristics (see for a full overview). In general, the discursive agents were mainly characterized by their knowledge and experience with waste management, as well as their mandate institutionalized in the Packaging Ordinance. Consequently, almost all actors identified in the packaging waste management system (see ) were each perceived to be discursive agents. The collecting, sorting, and recycling operators are represented by their business association, which we call Private Waste Management Businesses, and the consumers are represented by the Public Interest Organizations. All agents attributed the legislator – for this case, the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, and Nuclear Safety – with the task to bring the different interests of the actors together in a new regulation. Hence, the legislator was not perceived as an actor with strong opinions of its own, but rather the one who ‘everyone tries to influence’ (I-14). In this way, the policymaking process was perceived as an exchange between the discursive agents and the legislator, institutionalized in participation processes, discussion rounds, and hearings between 2010 and 2016.

Table 1. The main discursive agents based on their individual and positional characteristics.

4.3. The main narratives and their suggested policy solutions

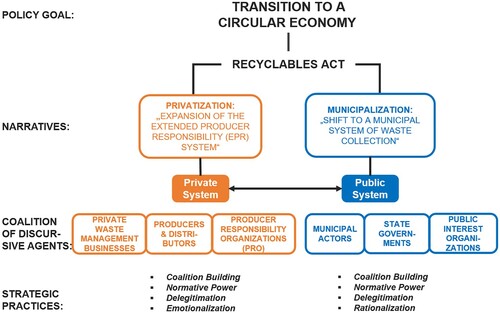

During the different phases of the policymaking process, all agents (see results 4.2) demanded an ambitious new regulation that would address the problems of freeriding and enforcement (see results 4.1) as well as radically enhance the system’s sustainability (Baum, Citation2014; Flanderka & Stroetmann, Citation2012). Specifically, all agents agreed that the new regulation should move the sector a step closer towards a circular economy. One proposal to do so was the institutionalization of the Recyclables Act (Wertstoffgesetz). The basic idea of this regulatory proposal was to add non-packaging waste products, with similar material composition, to the existing EPR system for lightweight packaging. In this way, the respective yellow bin for lightweight packaging (Gelbe Tonne) would become a recyclables bin (Wertstofftonne) (Flanderka & Stroetmann, Citation2012). However, during the policy discussion it became clear that there was a major disagreement on the preferred organizational system design of the new Recyclables Act. Following the interviewees’ perspectives, there were two opposing camps – public versus private – each presenting a different narrative on the nature of the policy problem and the ‘right’ policy solution. The following elaborates on these two opposing narratives, the coalitions of discursive agents promoting them, and the strategic practices (indicated in italics) that were used to shape the policymaking process. provides a summary of the main results.

Figure 2. Composition of narratives, stakeholders, and strategic practices informing the policy discussions.

4.3.1. The privatization narrative: ‘Expansion of the EPR principle’

The discursive agents Producers & Distributors, Private Waste Management Businesses and Producer Responsibility Organizations formed a private coalition (see ) on the belief that strengthening the existing private, competitive waste management system meant safeguarding a sustainable and circular waste management system in Germany. As one interviewee states: ‘this construct of private collection and disposal of packaging, one should […], I don’t want to say believe, but […] consider it the best solution’ (I-1). Based on a shared positive evaluation of the organizational design of the Packaging Ordinance, the coalition called for an expansion of the private EPR system. The agents argued that only this system could ensure a cheap and efficient packaging waste management. Despite these successes, the private coalition acknowledged that freeriding practices unbalanced the system, which is why they supported the call for a new regulation.

Regardless of the challenges, the private coalition emphasizes their 25 years of waste management competence and experience. ‘The industry brings experience as they bring the waste in circulation. That is why they also should be the ones to arrange how its disposal functions’ (I-2). By also circulating non-packaging waste products in this EPR system, private actors would get the opportunity to exercise their expertise over more materials and, in this way, further ensure an increasingly cheap and efficient waste management system. ‘That is why the private sector has said that we want to keep it this way and not convert it back to something public’ (I-18).

To underline their argument, the private coalition used several strategic practices (see ). Foremost, the private coalition employed the normative power of several core values. For instance, they invoked the value of environmental conservation by arguing that a competitive system gives the incentive to invest in better recycling technologies, ensuring the best environmental protection. Furthermore, they invoked the value of fairness, arguing that the private actors had already started to fund and organize an external control body in 2014 to increase transparency and control in the competitive system. Eliminating freeriding practices would guarantee a fair system that would be ‘put on secured financial ground and therefore become a sustainable system for the future’ (I-2).

In line with their narrative, the coalition used a delegitimation strategy towards the opposing narrative and its proponents, which proposed a shift to a public system. The private discursive agents argued that there is this ‘trend of municipalization in Germany’ (I-7). This argument emotionalized the policy discussions as this trend was projected as a dangerous evolution that would stop innovation in the packaging sector and therefore create a less efficient and more expensive waste management system.

4.3.2 The municipalization narrative: ‘Shift to a municipal system of waste collection’

The discursive agents Municipal Actors, Public Interest Organizations, and State Governments found common ground in their disagreement regarding the privatization narrative. Although emphases in their evaluation of the Packaging Ordinance differed, the public agents created a coalition regarding a negative evaluation of the private waste management organization (see ). Their shared counter-narrative was based on the need for changing the institutional system design. To make the Recyclables Act successful, a shift from a private towards a municipal organization of waste collection was seen as inevitable: ‘we […] need a recyclables bin but we also need a strong municipal responsibility’ (I-9).

The Municipal Actors and Public Interest Organizations attributed the problems under the Packaging Ordinance to the variety of actors involved. They perceived the system as overly complex, which ‘leads to splitting up responsibilities, which makes that no one […] feels responsible’ (I-10). This complexity is seen as the main reason for the illegal practices and lack of enforcement in the system. Furthermore, it was argued that an expansion of the private system would not lead to sustainable and circular waste management, but rather, would intensify the existing problems. The public agents presented their municipal solution as a ‘citizen-oriented, understandable, inexpensive and simple [system], one that everyone understands’ (I-12).

In addition, the State Governments framed the Packaging Ordinance as problematic concerning the lack of transparency and enforcement ability. Again, it was argued that a well-functioning waste management system can only be achieved by shifting away from the private organization. A shift to a municipal system would reduce the opportunities for freeriding significantly, and therefore not only increase the transparency in the system but also solve enforcement issues at the same time. Next to that, the coalition stressed that municipalities have the capacity, expertise, and resources to put this change into good practice. Importantly, however, they did not argue that the entire ERP system should be publicly organized. Instead, only ‘the collection should be municipal, the recycling can and should be organized by the private sector’ (I-9). Nevertheless, the public proposal called into question the position and legitimacy of the PROs.

As indicated in , the public coalition also used several strategic practices to support their narrative. The public coalition rationalized the suggested shift from a private to a public system by employing the normative power around different core values. For instance, the public coalition invoked the value of effectiveness, arguing that by bringing the collection of all waste streams – packaging and non-packaging – into one hand, complexity would be reduced. Furthermore, they invoked the value of transparency, arguing that by eliminating private profits during the waste collection, the public system will lead to well-functioning and secured waste management. Overall, the public coalition used the above-described arguments to delegitimize the private proposals and to present their counter-narrative as the better alternative.

4.4. Agency struggles and the shift from the Recyclables Act to the Packaging Act

The private and public coalitions – with their respective privatization and municipalization narratives – shaped the policy discussions of the Recyclables Act, with the use of delegitimation and normative power. In this way, the discussions centered around ‘criticizing each other’s quality’ (I-16) and core values of well-functioning and sustainable waste management. We identify that the use of these strategic practices in their arguments also resulted out of concerns regarding potential radical changes of respective positions and responsibilities in the system. One interviewee summarizes the conflict as follows: ‘in essence it was all about […] the sovereignty over materials and actions’ (I-5).

In other words, both public and private agents perceived the opposed system change and its corresponding fundamental shifts as a threat. An institutionalization of the public municipalization narrative posed a threat to the Producers & Distributors, as they feared that allowing this step towards municipalization in the packaging sector would result in gradual loss of all control over the management of ‘their’ resources. The PROs feared the public narrative even more, as it questions their position and legitimacy. Conversely, public agents feared an institutionalization of the private narrative. By allowing the private sector to bring more materials and resources into the private EPR system, the Municipal Actors would consequently lose financial and organizational responsibility for these materials. The State Governments also felt their position attacked by the privatization narrative, as this would not solve but rather increase the problematic enforcement and inability to act against freeriding practices under the new regulation.

In response to the public and private agents’ perceived threats, the policy discussions were limited to a repetition of the two main narratives. Consequently, conflicts over organizational issues dominated the narratives and their arguments, leaving no space for alternative solutions or environmental concerns. This focus on conflict, driven by the fear of radical change, further forced reciprocal delegitimation and enhanced the emotionalization of the debate. Instead of discussing a common solution for all, agents focused on protecting their position and responsibilities. This created a lock-in situation where the divergence between the public and private coalitions could not be overcome and no narrative gained dominance: ‘I would say that the [power of the actors in the] discussion was balanced, and because of this balance it didn’t work out in the end. […] Because no force could completely assert itself’ (I-4).

In the meantime, the waste management issues under the Packaging Ordinance accumulated and the pressure to find a solution grew among all discursive agents. In addition, the political pressure on the legislator increased as a policy reform had been planned over multiple governance cycles. As such, the legislator decided in 2016 to change the focus from a radical policy reform to an improvement of the Packaging Ordinance, rather focusing on concepts that were less controversial between the public and private agents. The policymaking process shifted away from the idea of a Recyclables Act – which required radical changes in agents’ positions and responsibilities – and instead focused on incremental changes under the German Packaging Act.

This shift made the narratives on the appropriate system no longer applicable and required a reorientation of all discursive agents. As a system change was off the table, the agents now struggled over gaining power and control in the implementation of the new regulation. This situation opened up the opportunity for a new coalition: ‘the municipal actors and the industry associations [i.e. Producers & Distributors and Private Waste Management Businesses] came together and considered on which ground they could talk’ (I-11). The resulting points of agreement formed the cornerstones of the institutionalized content of the Packaging Act. In this way, the new packaging waste management regulation was accepted by the German government – in the Bundestag and Bundesrat – in the summer of 2017 and entered into force on January 1, 2019 (Deutscher Bundestag, Citation2018).

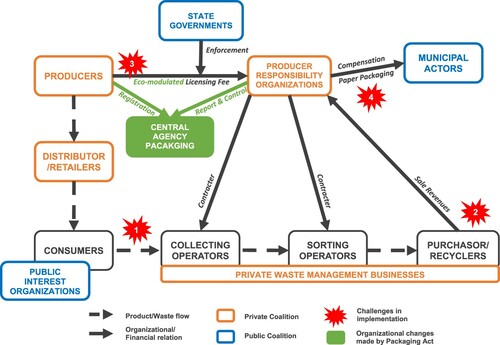

4.5. The policy outcome and its (lacking) changes in the system

The discursive struggles during the policymaking process shaped the institutionalized policy outcome, holding only minor changes in the positions and responsibilities of the actors in the packaging sector (see ). Only one significant change was made: the creation of a Central Agency Packaging Register (CAPR), organized by the Producers & Distributors. Under the Packaging Act, the CAPR will control the contract between producers and PROs. This implies a shift of this task from the State Governments to the new CAPR. With the creation of this new institution, the Packaging Act aims to improve organizational issues.

In particular, the new regulation tackles the four problems that drove the need for a new packaging waste management regulation (introduced in section 4.1) (see ):

Freeriding practices by under-licensing or non-licensing of the producers are addressed through an additional registration of the volume, weight, and material type of packaging with the CAPR. This data is compared with the information presented by the PROs and the market share of the producers. Furthermore, the licensing of each producer is publicly accessible to enhance more control among competitors.

The freeriding practices of the PROs should be eliminated by the introduction of the CAPR. PROs are now obliged to report their contracts with producers to the CAPR, enabling better control of the PROs’ activities.

The lack of enforcement capabilities of the State Governments is addressed through the Packaging Act’s aim to reduce their workload, as the CAPR takes over the control of potential freeriding practices. When detecting freeriding, the CAPR advises the State Governments on the appropriate punishment.

Consumer’s inability to separate the waste correctly is addressed by intensified consumer information of both PROs and municipalities.

Next to these organizational changes, the Packaging Act introduces measures to increase the system’s sustainability. In particular, the Packaging Act institutes increased binding targets for recycling quota in all packaging waste streams by 2022. Furthermore, the Packaging Act aims to incentivize sustainable packaging by introducing an eco-modulated license fee. This means that the price for licensing recyclable or bio-based packaging is reduced compared to other packaging. The concrete details of this measure, however, are not defined in the regulation and are to be developed by the CAPR during the first years of implementation. Appendix C holds a detailed overview of the changes made from Packaging Ordinance to the Packaging Act.

Overall, these measures demand an increase in existing efforts rather than new efforts to enhance the system’s sustainability. These incremental changes following the adoption of the German Packaging Act show that both the private and public coalitions successfully argued against fundamental shifts in their positions and responsibilities. Nevertheless, the interviews show that the actors were disappointed overall with the policy outcome, as it is generally presented as ‘the eighth amendment of the Packaging Ordinance’ (I-12). This indicates that the policy outcome is neither seen as the same as its predecessor, nor as the radical transition to a more sustainable and circular waste management system that was intended. Despite this disappointment, the agents identified the policy outcome as ‘the best political compromise possible’ (I-18) at this moment in time.

4.6. Implementation challenges and the agents’ responses

Regardless of the changes made under the German Packaging Act, the agents agree that the incremental changes in the policy outcome identify existing or bring new challenges during its implementation of the (see red stars in ), namely:

Achieving the increased recycling quota by 2022, as this requires increased consumer efforts as well as better technology. Agents question the feasibility.

Bringing the recycled materials back into the market as secondary raw material for packaging. Next to regulatory boundaries, it is of concern that a large market for valorized materials is missing; primary materials are still cheaper and incentives for applying secondary materials are limited. It is unclear who – government or businesses – is responsible for overcoming this challenge.

Finding effective mechanisms that ensure eco-modulated licensing fees, as it is unclear how this measure can function in a system of competition between the PROs.

Generating constructive communication and cooperation between municipalities and PROs. As both agents conflicted heavily during the policymaking process, it is questioned to what extent these conflicts will influence their relationship during the implementation.

The agents also agree that overcoming all of these challenges is crucial for a successful implementation of the German Packaging Act, and that determining responsibilities and concrete measures are the first tasks to solve. However, their reaction to the new regulation and the implementation challenges differ. Once again, the discursive agents are divided into two coalitions supporting opposing narratives.

One coalition – consisting of public agents (Municipal Actors, State Governments, and Public Interest Organizations) as well as some Producers & Distributors and Private Waste Management Businesses – created a reformist narrative that presents the Packaging Act and its challenges as a serious setback for the transition to a circular economy. The narrative is constructed around the belief that due to the regulation’s ambiguous language and the complexity of the challenges and responsibilities, the Packaging Act will fail to address the system’s organizational and environmental issues. In the words of one interviewed State Government actor, the Act is ‘unfit and impossible to enforce’ (I-12). Therefore, the dependence on the willingness and interpretation of implementing actors is perceived as a negative component. This could enhance ‘the use of tricks’ (I-12), such as new types of freeriding practices, which could potentially worsen the overall system’s sustainability. Along these lines, it is questioned whether the Packaging Act can have a direct contribution to a transition to a circular economy in the packaging sector. As such, this narrative argues that a reform of the Packaging Act is the only solution for the effective reorganization and transformation of the waste management system. With this argument, the agents attempt to re-issue their preferred idea of the Recyclables Act in line with their initial storyline (as described in section 4.2) and open up the policy discussions once again.

The other coalition – consisting of the Legislator and some Producers & Distributors and Waste Management Businesses – created an incrementalist counter-narrative, which presents the above-described challenges rather as an opportunity. They see the ambiguity in language as a potential chance to enhance the Packaging Act during the implementation phase and ensure its contribution to a circular economy. Among other things, agents expect that the implementation of the Packaging Act will help to determine where packaging is necessary, and where surplus packaging can be minimized or even avoided: ‘We probably won’t be able to unpack everything, but we will be happy to do whatever is possible’ (I-3). Furthermore, the agents are positive that the efforts of the industry will also affect the mind-set of consumers to practice sustainability – for example, by buying packaging made from recycled material. ‘[We are] already making a lot of progress in this direction and working hard to meet the requirement of the new Act’ (I-1). In addition, this narrative is constructed around a positive evaluation of the potential contribution of the CAPR in the packaging sector. Not only does the increased transparency give positive signs regarding a stable and fair system of competition, but also the interaction of all agents in the committees of the CAPR is seen as a positive development that can improve the coordination in the sector. In this way, the agents expressing this narrative stress that the sector should first focus on good implementation of the different elements of the Packaging Act, and that discussions of potentially necessary amendments to the regulation should only start after the planned evaluation in 2022.

In summary, the different approaches towards the policy outcome in a reformist and incrementalist coalition indicate that the ‘best political compromise’ achieved with the 2019 Packaging Act is unlikely to last for very long. In this way, it does not bode well for the collective wish of a final conflict resolution. Instead, the current situation suggests that the German packaging sector is soon to enter debates about the next amendment to the Packaging Act to address the various challenges. Conflicts during the implementation – as a result of the ongoing incremental changes – may trouble future debates in the packaging sector even more because they perpetuate coalitions and harden positions. Furthermore, the yearlong policy process may have created debate fatigue, as the debates so far are perceived to fail with regards to ‘radical’ policy change for a circular economy in Germany.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Our results show that agents’ perceived fears of radical changes created a lock-in situation of opposing narratives on the organizational design of packaging waste management, which was resolved by trading radical for incremental change. Our results suggest that (1) agents’ perceived fears of radical changes prevent successful transition politics, and (2) incremental change does not overcome fears or resolve conflicts but may instead weaken the agents’ capacities to make significant change. We elaborate on these findings and learnings below.

Our analysis explains the policy process and outcome of the German Packaging Act as a result of agents’ perceived fears of radical changes, expressed in opposing narratives on the organizational design of packaging waste management. We identify two narratives, one suggesting further privatization, the other a stronger municipalization, which divided the agents, respectively, into a private and a public coalition. As both narratives suggested fundamental shifts in agents’ positions, all agents feared a loss of control and responsibilities. Hence, both coalitions used strategic practices to protect their positions in the system. These practices contributed to a lock-in situation, which left no room for alternative approaches. To solve this situation, policy discussions shifted away from the desire to achieve the jointly aimed Recyclables Act – which was perceived to include a radical change – and focused on incremental changes instead. Trading radical for incremental changes freed the agents from the threats posed by the alternative narrative and made the institutionalization of a new packaging waste management regulation, the 2019 German Packaging Act, possible.

However, because of this shift from radical to incremental change, the agents evaluate the Packaging Act as disappointing in its contribution to sustainability, criticizing that it leaves many challenges and conflicts unresolved. As the political ‘compromise’ avoids addressing the conflicts that shaped the policymaking process and leaves a lot of room for maneuvering in the implementation, all agents are preparing for further discursive struggles. While some agents fall into an incrementalist coalition, arguing that some conflicts may be resolved during the implementation, an opposing reformist coalition demands new political discussions on a more far-reaching policy reform. This division of agents will shape the imminent conflicts during the implementation of the Packaging Act. These ongoing conflicts may foster mistrust between the agents and result in an unwillingness to engage in further discussions, given that the previous, yearlong debates did not provide a major step forward. Hence, the focus on incremental changes may form another hurdle for the future development of sustainable and circular waste management in Germany.

These findings suggest two noteworthy learnings for scholars, practitioners, and policymakers on circular economy, as well as transition politics more generally. First, we suggest that the agents’ perceived fears of radical changes prevented successful circular economy transition politics. This explanation of the unambitious policy outcome of the Packaging Act builds further on the scholarly understanding of the relevant actors, discussions, and underlying dynamics in the German packaging waste sector (see Neumayer, Citation2000; Rasek & Smuda, Citation2018), while also adding to the scholarship on barriers for a circular economy. The scholarly literature holds large expectations of new policies to overcome current cultural, regulatory, market, and technological barriers that explain the limited progress towards a circular economy (see among others de Jesus & Mendonça, Citation2018; Hartley et al., Citation2020; Kirchherr et al., Citation2018; Ritzén & Sandström, Citation2017). It is expected that new policies (1) are simply depending on the willingness of actors and (2) will automatically resolve (all) current issues. Our results rebut both these expectations. Even when all actors support the desire for a transition to a circular economy, the fear of radical changes to their positions and responsibilities in the current system can form a central barrier to creating ambitious transition policies. Overall, these findings contribute to understanding agency and discourse in transition politics literature.

Second, the findings make a relevant contribution to understanding the problematics of incremental changes in transition politics. Our study highlights that incremental change does not overcome fears or resolve conflicts among agents but may instead weaken the agents’ capacities to make significant change. Our study underlines that incremental changes can trigger the continuation of discursive struggles during the implementation phase. Also, the focus on incremental developments reinforces business-as-usual thinking and therefore limits the potential for radical discursive or social change, as also argued by Leipold et al. (Citation2019) and Mendoza et al. (Citation2017). Finally, it may create mistrust and debate fatigue. We suggest that this continuous lack of ambition by implementing only incremental change is probably the most problematic for transition politics as it creates frustration among agents, which may solidify their positions and, in turn, make future ambitious transition politics even harder to achieve. In this way, incremental changes can be counterproductive to the goal of transitioning to sustainability and our findings support the call of Flynn and Hacking (Citation2019) and Lazarevic and Valve (Citation2017) for alternative approaches to achieve a sustainable circular economy. These findings indicate that more research is required to develop ‘change strategies’ for the agency of incumbents, which address the dependency on current system structures and enables them to engage positively with processes of radical change. A more elaborated understanding of such narratives and strategic practices will not only contribute to the enhancement of a sustainable circular economy but also generate further insights on discursive agency in transition processes and politics.

As our data collection happened at an early stage of the German Packaging Act’s implementation process, the analysis of the implementation dynamics is neither exhaustive nor conclusive. For example, our data gave insufficient insights on the proportion and relation of the various implementation challenges identified. Therefore, we see our insights as a starting point for future research on how the discursive struggles in the first years of the Packaging Act’s implementation will unfold. Furthermore, it was beyond the scope of this research to analyze the understanding of the different actors on the concept of the circular economy. A more elaborated understanding of this matter can build further on the research of, among others, Tencati et al. (Citation2016) and generate further insights on the current lock-in on recycling instead of other waste management approaches in policy. In line with our research, we argue that further use of discursive lenses is desirable for future transition research and politics.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Dimitra Ioannidou for contributing to the data collection and analysis as well as Anran Luo and the journal reviewers for their input on earlier drafts. Furthermore, we thank all interviewees for their willingness to cooperate in this research. We are grateful to the financial support by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, grant number 031B0018, as part of the research group ‘Circulus – Opportunities and challenges of transition to a sustainable circular bio-economy’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Machteld Catharina Simoens

Machteld Catharina Simoens is research associate and PhD candidate at the Chair of Societal Transition and Circular Economy at the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg. Her main research interests are transitions to sustainable patterns of production and consumption. In her PhD project, she focusses on the sustainability transition to a circular economy in the packaging sector, with an analytical focus on the role of agency and discourse.

Sina Leipold

Sina Leipold is an assistant professor of Societal Transition and Circular Economy at the University of Freiburg, Germany. She heads a transdisciplinary research group committed to providing path breaking insights into the governance of inter- and transnational resource flows and their biophysical impacts. Her expertise includes discourse analysis theories and methods (qualitative and quantitative), natural resource policies in the EU and internationally, as well as policies, strategies and indicators for a circular economy.

References

- Albrecht, E. (2018). Discursive struggle and agency - updating the Finnish Peatland conservation network. Social Sciences, 7(10), 177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100177.

- Ampe, K., Paredis, E., Asveld, L., Osseweijer, P., & Block, T. (2019). A transition in the Dutch wastewater system? The struggle between discourses and with lock-ins a transition in the Dutch wastewater system? The struggle between discourses and with lock-ins. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1680275.

- Avelino, F., Grin, J., Pel, B., & Jhagroe, S. (2016). The politics of sustainability transitions. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 557–567. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1216782.

- Avelino, F., & Wittmayer, J. (2016). Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 628–649. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1112259.

- Bailey, I. (2003). New environmental policy instruments in the European Union: Politics, economics, and the implementation of the packaging waste directive. Ashgate Publishing.

- Baum, H.-G. (2014). Neuausrichtung der Verpackungsentsorgung unter Beachtung einer nachhaltigen Kreislaufwirtschaft. Fulda.

- Boyatzis, R. (1998). Transforming qualitative information. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A.T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

- de Jesus, A., & Mendonça, S. (2018). Lost in transition? Drivers and barriers in the eco-innovation road to the circular economy. Ecological Economics, 145, 75–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.08.001.

- Deutscher Bundestag. (2018). Neuregelungen durch das Verpackungsgesetz gegenüber der Verpackungsverordnung – WD 8 – 3000 – 051/17. Berlin.

- Dryzek, J. S. (2013). The politics of the earth: Environmental discourses. Oxford University Press.

- Duygan, M., Stauffacher, M., & Meylan, G. (2019). A heuristic for conceptualizing and uncovering the determinants of agency in socio-technical transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 33, 13–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000334668.

- Eichstädt, T., Carius, A., & Kraemer, R. A. (1999). Producer responsibility within policy networks: The case of German packaging policy. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/714038530.

- European Commission. (2015). Closing the loop - An EU action plan for the circular economy. Brussels: European Commission.

- Feindt, P. H., & Oels, A. (2005). Does discourse matter? Discourse analysis in environmental policy making. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 7(3), 161–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080500339638.

- Fischer, L.-B., & Newig, J. (2016). Importance of actors and agency in sustainability transitions: A systematic exploration of the literature. Sustainability, 8(5), 476–497. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su8050476.

- Flanderka, F., & Stroetmann, C. (2012). Von der Verpackungsverordnung zum Wertstoffgesetz. AbfallR, 1, 2–11.

- Flynn, A., & Hacking, N. (2019). Setting standards for a circular economy: A challenge too far for neoliberal environmental governance? Journal of Cleaner Production, 212, 1256–1267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.257.

- Grin, J., Rotmans, J., & Schot, J. (2011). On patterns and agency in transition dynamics: Some key insights from the KSI programme. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), 76–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2011.04.008.

- Hajer, M. (2006). Doing discourse analysis: Coalitions, practises, meaning. In M. Van den Brink, & T. Metze (Eds.), Discourse theory and method in the social sciences (pp. 65–76). Netherlands Graduate School of Urban and Regional Research.

- Hajer, M., & Versteeg, W. (2005). A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: Achievements, challenges, perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 7(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080500339646

- Hartley, K., van Santen, R., & Kirchherr, J. (2020). Policies for transitioning towards a circular economy: Expectations from the European Union (EU). Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 155, 104634. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104634.

- Kern, F. (2015). Engaging with the politics, agency and structures in the technological innovation systems approach. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 16, 67–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2015.07.001.

- Kirchherr, J., Piscicelli, L., Bour, R., Kostense-Smit, E., Muller, J., Huibrechtse-Truijens, A., & Hekkert, M. (2018). Barriers to the circular economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics, 150, 264–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.04.028.

- Kirchherr, J., Reike, D., & Hekkert, M. (2017). Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 127, 221–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005.

- Köhler, J., Geels, F. W., Kern, F., Markard, J., Onsongo, E., Wieczorek, A., Alkemade, F., Avelino, F., Bergek, A., Boons, F., Fünfschilling, L., Hess, D., Holtz, G., Hyysalo, S., Jenkins, K., Kivimaa, P., Martiskainen, M., Mcmeekin, A., Mühlemeier, M. S., … Wells, P. (2019). An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31, 1–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004.

- Lang, S., Blum, M., & Leipold, S. (2019). What future for the voluntary carbon offset market after Paris? An explorative study based on the discursive agency approach. Climate Policy, 19(4), 414–426. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1556152.

- Lazarevic, D., & Valve, H. (2017). Narrating expectations for the circular economy: Towards a common and contested European transition. Energy Research & Social Science, 31, 60–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.006.

- Leipold, S., Feindt, P. H., Winkel, G., & Keller, R. (2019). Discourse analysis of environmental policy revisited: Traditions, trends, perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(5), 445–463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1660462.

- Leipold, S., & Petit-Boix, A. (2018). The circular economy and the bio-based sector - perspectives of European and German stakeholders. Journal of Cleaner Production, 201, 1125–1137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.019.

- Leipold, S., Sotirov, M., Frei, T., & Winkel, G. (2016). Protecting “First world” markets and “Third world” nature: The politics of illegal logging in Australia, the European Union and the United States. Global Environmental Change, 39, 294–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.06.005.

- Leipold, S., & Winkel, G. (2016). Divide and conquer-discursive agency in the politics of illegal logging in the United States. Global Environmental Change, 36, 35–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.11.006.

- Leipold, S., & Winkel, G. (2017). Discursive Agency: (Re-)conceptualizing actors and practices in the analysis of discursive policymaking. Policy Studies Journal, 45(3), 510–534. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12172.

- Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., & Avelino, F. (2017). Sustainability transitions research: Transforming science and practise for societal change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 42(1), 599–626. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ.

- Meadowcroft, J. (2011). Engaging with the politics of sustainability transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), 70–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2011.02.003.

- Mendoza, J. M. F., Sharmina, M., Gallego-Schmid, A., Heyes, G., & Azapagic, A. (2017). Integrating backcasting and eco-design for the circular economy: The BECE framework. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 21(3), 526–544. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12590.

- Neumayer, E. (2000). German packaging waste management: A successful voluntary agreement with less successful environmental effects. European Environment, 10(3), 152–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0976(200005/06)10:33.0.CO;2-N

- Patterson, J., Schulz, K., Vervoort, J., van der Hel, S., Widerberg, O., Adler, C., Hurlbert, M., Anderton, K., Sethi, M., & Barau, A. (2017). Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 24, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.001.

- Rasek, A., & Smuda, F. (2018). Ex-post evaluation of competition law enforcement effects in the German packaging waste compliance scheme market. De Economist, 166, 89–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-017-9306-7.

- Ritzén, S., & Sandström, GÖ. (2017). Barriers to the circular economy - integration of perspectives and domains. Procedia CIRP, 64, 7–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2017.03.005.

- Roberts, C., & Geels, F. W. (2018). Public storylines in the British transition from rail to road transport (1896–2000): Discursive struggles in the multi-level perspective. Science as Culture, 27(4), 513–542. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2018.1519532.

- Rosenbloom, D. (2018). Framing low-carbon pathways: A discursive analysis of contending storylines surrounding the phase-out of coal-fired power in Ontario. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 27, 129–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.11.003.

- Schüler, K. (2018). Aufkommen und Verwertung von Verpackungsabfällen in Deutschland im Jahr 2016. Dessau-Rosslau: Umweltbundesamt.

- Sharp, L., & Richardson, T. (2001). Reflections on Foucauldian discourse analysis in planning and environmental policy research. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jepp.88

- Smith, A., & Stirling, A. (2010). The politics of social-ecological resilience and sustainable socio-technical transitions. Ecology and Society, 15(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03218-150111.

- Tencati, A., Pogutz, S., Moda, B., Brambilla, M., & Cacia, C. (2016). Prevention policies addressing packaging and packaging waste: Some emerging trends. Waste Management, 56, 35–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2016.06.025.