ABSTRACT

This paper aims to explore the role of institutions, and specifically of the Ombudsman, in creating and practicing policies with relevance to energy poverty as a case of procedural energy (in)justice in a European context, while refining procedural energy justice. It is empirically informed by studies about the Austrian energy utility-based Ombudsman and the independent Ombudsman in North Macedonia, countries with a low and high level of energy poverty, respectively. I highlight the unexplored institutional capacity of the independent Ombudsman to discover hidden institutional energy poverty drivers, and the utility-based Ombudsman to alleviate energy poverty, and contribute to a socially just energy transition. The energy market and social welfare system are important institutions co-shaping energy poverty, and the energy utility plays an especially relevant role in creating or preventing energy injustices. Procedural energy justice applied to energy poverty is about how institutions treat citizens over access to affordable energy, and how citizens are (dis)empowered by that relationship.

Introduction

The EU-led energy transition has received much-needed academic attention, however, it should not be only focused on studying technologies and fuels (Jenkins et al., Citation2017). At the core of the energy system are, however, its people who along with institutions and policies are part of a specific energy culture (LaBelle, Citation2020). From an energy justice point of view, everyone is entitled to use affordable, safe, and clean energy (Heffron & McCauley, Citation2014). However, almost 50 million people across the EU are affected by energy poverty (Thomson & Bouzarovski, Citation2018), defined as the inability to attain a socially and materially necessitated level of domestic energy services (Bouzarovski & Petrova, Citation2015). Being vulnerable to energy poverty impedes their participation in the energy transition process (Bouzarovski & Tirado Herrero, Citation2017; Sovacool et al., Citation2019), and raises the question about the inclusiveness of the energy transition (Stojilovska, Citation2020).

More recent energy poverty discussions try to shift the focus away from energy-poor households and put pressure on the policies and institutional path-dependencies which keep the energy-poor locked in (Petrova, Citation2018). There is an increased interest in the role of institutions and processes that should rectify energy injustices across the energy system (Jenkins et al., Citation2016) and balance different economic, environmental, and political goals (Heffron et al., Citation2015). Institutions are defined as formal institutions being social structuring to regulate political, social, or economic human interaction and to be distinguished from simple regulations and arrangements (Lepsius, Citation2017; North, Citation1990). Adding to the plurality of actors, activists engage in social movements (Yoon & Saurí, Citation2019) and emphasize the ‘right to energy’ concept to demand greater protection for vulnerable consumers from the privatization of the energy sector in Europe (EPSU & EAPN, Citation2017). While the academic literature is trying to keep up with the citizen-led demands for affordable energy (Frankowski & Tirado Herrero, Citation2021; Fuller & McCauley, Citation2016) there is very limited research about the contribution of institutions in conceptualizing energy poverty and exposing hidden energy injustices. Typically, national governments, energy suppliers, regional or local governments, and in fewer cases NGOs and energy regulators are relevant institutions offering various measures to alleviate energy poverty, but there is no mention of an Ombudsman (EU_Energy_Poverty_Observatory, Citation2020b).

The Ombudsman, typically an independent institution tasked to observe human rights, has rarely been examined as an actor in the energy poverty and energy justice literature, although it can be a powerful actor in detecting legal breaches that inflict injustices on energy-poor households (Hesselman & Herrero, Citation2020). The Ombudsman refers to an independent public institution with the task to perform a soft control of public administration, preferably of the executive branch of government (Kucsko-Stadlmayer, Citation2008; Reif, Citation2004). This article is inspired by the work of the independent Macedonian Ombudsman speaking out on energy injustices inflicted by energy monopolies on (vulnerable) citizens and the Austrian utility-based Ombudsman established to address the individual situations of its energy consumers unable to pay their energy bills. Thus, this paper aims to explore the role of institutions, and specifically of the Ombudsman, in creating and practicing policies with relevance to energy poverty as a case of procedural energy (in)justice in a European context, while refining procedural energy justice.

The Ombudsman in North Macedonia is described as a special professional independent body not belonging to any branch; it is tasked to protect citizens’ rights (Ombudsman, Citation2011a), and this is a typical Ombudsman institution. The Austrian one is not a typical Ombudsman, but a separate body set up within the Austrian state-owned energy utility Wien Energie. The Austrian Wien Energie Ombudsman works with private and clients of social institutions which are in a difficult life situation preventing them from paying their energy bills (Wien_Energie, Citation2021). The case studies, North Macedonia and Austria, represent different geographical areas with different levels of energy poverty. Austria belongs to the ‘geographical core’ with relatively lower levels of energy poverty (Bouzarovski & Tirado Herrero, Citation2017; Thomson & Snell, Citation2013), while as a post-socialistic country North Macedonia is faced with a lack of proper infrastructure, cold climates, and systemic deficiencies in the management of housing, energy and social welfare belonging to the Central Eastern Europe region with comparatively higher levels of energy poverty (Bouzarovski, Citation2014; Thomson & Snell, Citation2013). By studying the role of the Ombudsman as a protector of vulnerable citizens from energy injustices, I highlight the institutional capacity of ‘untypical’ stakeholders, such as the Ombudsman and public utilities, to contribute to a socially just energy transition while systematically addressing energy poverty.

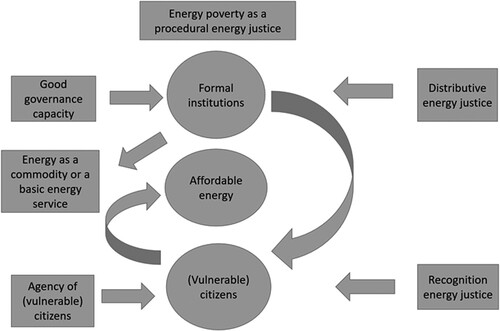

Energy poverty as a procedural energy justice

I primarily apply the procedural energy justice concept to energy poverty, where I focus on the role of formal institutions in detecting, preventing, or creating energy poverty. The conceptual framework is also informed by the right to energy concept, energy citizenship, and more extended energy justice discussions. In Graph 1, I present visually the conceptual framework I propose. Graph 1 shows that procedural energy justice is about the relationship between formal institutions and citizens, and often vulnerable citizens, over access to affordable energy. Procedural energy justice applied to energy poverty is about how institutions treat citizens over access to affordable energy, and how citizens are (dis)empowered by that relationship. To complete the conceptual framework, I inform the discussion with the good governance capacity of formal institutions, and the agency of (vulnerable) citizens. I also present the impacts of distributive and recognition energy justice on procedural energy justice, and how they can amplify the procedural injustices. Lastly, a crucial addition is whether formal institutions treat energy as a commodity or a basic energy service, and how the policies of formal institutions affect vulnerable citizens regarding access to affordable energy. In the sections below I elaborate on the conceiving of this conceptual framework.

Procedural energy justice shows the relationship between institutions and vulnerable citizens over affordable energy. The literature indicates that procedural energy justice is about the fair process (Jenkins et al., Citation2016) and fair decision-making (Bouzarovski & Simcock, Citation2017). Energy poverty is a procedural energy injustice when there is a lack of information on energy poverty, energy prices and solutions, lack of participation in energy, housing, climate, fiscal policies, lack of access to legal rights, and there are barriers to challenging these rights (Walker & Day, Citation2012). The inclusion of local knowledge, different levels of governance, and better institutional representation are also features of procedural justice (Jenkins et al., Citation2016; Walker & Day, Citation2012). This indicates that the processes of information sharing, participation in decisions, legal remedies, and inclusion of various stakeholders are in focus. Procedural justice is considered a universal type of justice (LaBelle, Citation2017). However, while these processes are highlighted, the stakeholders involved are neglected, and other processes resulting from various contacts between institutions and citizens regarding access to affordable energy services are not included. This requires reinterpretation of energy poverty as procedural energy justice to show the dynamics between the relevant institutions involved in policy-making, regulatory or energy supply, and the vulnerable citizens and how these citizens benefit or are disadvantaged by this relationship. Energy poverty is a procedural injustice when institutions are ignoring the needs of the energy-poor and creating policies that affect them negatively.

Procedural energy justice is more than just fairness and participation, but about setting up standards for the formal institutions shaping the decisions about energy poverty. Informed by broader energy justice discussions (Sovacool et al., Citation2017; Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2015), procedural energy justice points out that formal institutions need to have a good governance capacity. Energy justice is about achieving transparent and accountable forms of energy decision-making (Sovacool et al., Citation2017; Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2015). The discussions about energy justice and institutions emphasize that government policies need to address the social inequalities resulting from increasing energy prices by focusing on lower-income groups (Schlör et al., Citation2013). Rawls’ theory of justice states that the market creates inequalities, however, institutions are to rectify the distributive inequalities (Rawls, Citation1971). Institutions have to be just and unjust institutions need to be abolished (Rawls, Citation1971).

On the receiving side of energy services, are citizens which are gaining increased attention about their agency as (vulnerable) citizens. Gillard et al. (Citation2017) understand procedural justice as stakeholder engagement in policy and governance, while McCauley et al. (Citation2016) argue that procedural justice is about inclusive stakeholder engagement in a non-discriminatory way and setting up equitable procedures. NGOs and ordinary people are seen are new forms of governance that can contribute to better detection of vulnerabilities (Fuller & McCauley, Citation2016; Gillard et al., Citation2017; Walker et al., Citation2016). There is criticism against passivizing the citizens to consumers only (Lennon et al., Citation2019; Ryghaug et al., Citation2018). Not only are citizens seen as new actors but as proactive ones pointing out injustices and demanding retribution. Restorative justice, imported from criminal law, aims to repair the harm done to people, rather than solely focus on punishing the offender (Heffron & McCauley, Citation2017). Procedural justice is about showing resilience and protesting (McCauley & Heffron, Citation2018). Climate justice talks about sharing burdens and benefits between countries or individuals (Bulkeley et al., Citation2013).

The procedural energy justice touches upon more general subjects, such as institutions, governance, and policies, while the distributive and recognition justice are more narrowly defined. Inspired by the development of the environmental justice concept (Schlosberg, Citation2004), energy justice has three core elements of distributive, procedural, and recognition justice. According to Walker and Day (Citation2012) the distributive energy justice takes a central place impacting both the procedural and recognition justice. Distribution energy justice is about access to energy, affordability, and quality, security, or safety of energy sources (Heffron & McCauley, Citation2014; Jenkins et al., Citation2016; Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2015; Walker & Day, Citation2012). Recognition justice is about misrecognition of vulnerable groups (Jenkins et al., Citation2016; Walker & Day, Citation2012). I argue that distribution and recognition justice impact procedural justice, the former through the market structure and infrastructural path-dependencies (Bouzarovski et al., Citation2016; Robinson et al., Citation2018), while the latter through the size of the energy poverty problem.

After having discussed the performance of institutions and the agency of citizens, I describe the tendency for humanizing energy justice which adds more quality to the requirements of procedural energy justice for a fair process. Ideals of the morality of citizens and their well-being are raised by energy justice (Jenkins et al., Citation2018; McCauley et al., Citation2019; Sovacool, Citation2015; Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2015). This opens up the discussion about re-shaping the relationship between institutions and citizens over energy considering that energy services are needed for a normal life. Thus, institutions can treat energy as a commodity (Teschner et al., Citation2020; Walker, Citation2015) or a basic energy service which needs protection from its marketization and rising energy prices (Demski et al., Citation2019). They can go beyond market relations (Walker, Citation2015). The energy justice concept is also questioning the neo-classical economics thinking while putting forward the just and equitable approach rather than only an efficient one (Heffron et al., Citation2015). This ‘system re-thinking’ goes along with the recent demands at the European level about the right to energy by non-governmental organizations which demand the prohibition of disconnections for vulnerable consumers, and propose special tariffs, and public funds for energy efficiency for vulnerable households (EPSU & EAPN, Citation2017). The right to energy concept inspires the discussions of whether energy can be considered a legal (human or consumer right) or a moral right (Hesselman et al., Citation2019).

Methodology

The data are based on two case studies – North Macedonia and Austria following Yin (Citation2003) that case studies are used for how or why questions and contemporary phenomena. The main method for data collection is documents, such are written materials, official publications, and reports (Patton, Citation2002) to complement a case study (Punch, Citation2005). The documents were collected in the period 2017–2020 to study energy poverty in both countries. The collected materials from Austria are given by the Wien Energie Ombudsman, and the materials about North Macedonia are the annual reports of the Ombudsman for the period 2000–2018 which are publically available on the Ombudsman’s website. Additionally, interviews with relevant stakeholders representing the utilities, public and private organizations involved in studying energy poverty or energy provision in both countries are used – 3 in North Macedonia and 4 in Austria, to explain the wider socio-political environment. The sampling of the interviews was purposive, made in a deliberate way (Punch, Citation2005) to explore the energy poverty of households, and understand its underlining drivers.

The selected interviews and documents were analyzed qualitatively. I coded the selected material by following the steps of data condensation, data display, and conclusion drawing (Miles et al., Citation2014), differently for the two cases. The annual reports of the Macedonian Ombudsman were coded by mapping the Ombudsman’s contribution in interpreting the legislation; developing new legislation; implementing the legislation; and developing a new understanding of energy poverty. The interview with the Wien Energie Ombudsman representative and the materials given from this post were coded to understand the reasons for the establishment of the Ombudsman, the definition of its target group, and work with its target group. I acknowledge the empirical limitations informing the cases, using mostly Wien Energie Ombudsman as a source, and the annual reports of the Macedonian Ombudsman. I justify this since the Austrian Ombudsman offered real inquires by vulnerable consumers, and references from collaborators. The Macedonian Ombudsman is an independent institution publishing detailed publically available annual reports. The interviewees have given written consent for their interview, while one gave oral consent.

Case studies

The case studies are about the Macedonian independent Ombudsman and the Austrian energy utility-based Ombudsman which are unexplored actors in the energy system, although play a role in exposing energy injustices and addressing energy poverty. I use two cases of different types of Ombudsman in two countries in different contexts, the case of North Macedonia being a case of deeper energy poverty, and Austria being a case of lower energy poverty. The aim is not to directly compare the cases, but to use them as different examples for studying the different varieties of an Ombudsman body and its institutional role in exposing, or alleviating energy poverty. I present data about the structure and ownership of the energy markets and the effectiveness of the social welfare system since these institutions have been identified by the Ombudsman to increase or alleviate energy poverty. The three EU-SILC indicators used in serve as a guiding threshold for the level of energy poverty (EU_Energy_Poverty_Observatory, Citation2020a; Thomson & Snell, Citation2013) showing that North Macedonia is much more affected by energy poverty than Austria.

Table 1. Indicators of relevance to energy poverty for 2019.

North Macedonia is a post-socialist country with a high share of energy poverty, high levels of income poverty, and housing deprivation (). Energy poverty is driven by widespread material deprivation, inefficient housing stock, and over-dependency on subsidized electricity and fuelwood used in inefficient devices (Stojilovska, Citation2020). It can be compared to a subsistence-like economy which is the minimal level of productivity (Stojilovska, Citation2020); post-communist energy poverty related to the infrastructure legacies from the centrally planned economy (Bouzarovski & Tirado Herrero, Citation2017), and energy deprivation shaped by a lack of gas infrastructure (Bouzarovski, Citation2018). In Austria, a small minority is affected by energy poverty between 2 and 9% based on the EU-SILC criteria () and the study of their Energy Regulatory body argues that it is lower (CitationEnergie_Control_Austria). Income poverty and housing deprivation are comparatively low (). The Austrian social welfare system is much more effective in poverty reduction than the Macedonian ().

Macedonian Ombudsman

The case study about North Macedonia is focused on the work of the independent Ombudsman tasked to protect the constitutional and legal rights of the citizens when violated by the public bodies in the country. I analyze its contribution to exposing energy injustices imposed on citizens by the energy monopolies and social protection institutions. The results indicate that citizens suffer from the injustices inflicted by the district heat and electricity monopolies in private ownership and the weakness of the social welfare system. This section will show through representative examples how the Ombudsman has (1) interpreted the existing legislation; (2) developed new legislation; (3) implemented the existing legislation, and (4) developed new legal and policy understanding. While explaining each of these contributions of the Ombudsman, I explain how the Ombudsman has discovered the hidden institutional energy poverty drivers in North Macedonia – the district heat market, electricity market, and the social welfare system.

The Ombudsman has voiced its criticism of monopolies by elaborating that the existing legislation was not respected. I explain this through the example of collective electricity disconnections detected in multiple annual reports described as a misuse of the electricity utility’s monopoly position. Over the years in neighborhoods with a high concentration of non-payers of electricity, the electricity utility would disconnect not only the consumers which were not paying but also those paying (annual reports for 2004–2006; 2008–2009; 2013) (Ombudsman, Citation2011b). This is because the utility was afraid of physical injury potentially inflicted by dissatisfied consumers if it were to disconnect consumers on the spot (Ombudsman, Citation2011b). In 2008 alone, there were 9510 affected customers by collective disconnections (Energy_and_Water_Services_Regulatory_Commission, Citation2009). The Ombudsman states collective disconnections threaten basic human rights (Ombudsman, Citation2011b). The issue with the electricity utility is that is a private monopoly. It tends to sue consumers with arrears and employs an enforcement agent to collect debts (Interview with a representative of the private electricity utility EVN, 19. 05. 2017). Many citizens face affordability issues due to high energy bills. As a result of unpaid electricity bills, 73,727 consumers were disconnected from electricity in 2018 (Energy_and_Water_Services_Regulatory_Commission, Citation2019) which is around 3.5% of the population (Stojilovska, Citation2020).

The Ombudsman contributed to developing missing legislation. I explain this through the obligation for disconnected consumers of district heating in a collective building to pay for the basic district heat fee (noted in annual reports for 2012–2018) (Ombudsman, Citation2011b). The district heating network is small and only existing in the capital city. There are two district heating companies, each supplying a different part of the capital, the smaller is in public ownership and the larger is in private. Until recently, when one disconnected from the larger (private) supplier and lived in a collective building, one had to pay the basic fee for using passive energy. The Ombudsman considered this obligation to pay after being disconnected as breaching consumer rights (Ombudsman, Citation2011b). A small victory was achieved in 2018 when this obligation was going to get canceled (Ombudsman, Citation2011b). The issue with the district heating is since its consumers cannot economize their heating nor control the time of heating and indoor temperature. The larger (private) district heat company is against individual apartment bills since they consider not to be economically justified (Interview with a representative of the private district heat company BEG, 25.05.2017) knowing the tendency of citizens to economize the heating.

Having understood the link between material deprivation and energy arrears, the Ombudsman based on existing legislation demanded greater action about the social welfare system. The Ombudsman alerted that the current social protection system does not respond to the needs of the citizens at risk and as a result, a social welfare recipient family living in a bad illegal dwelling was affected by fire killing three children in 2018 (Ombudsman, Citation2011b). The Ombudsman has stated that the social welfare does not help the affected out of poverty and does not enable them a normal life as they can barely pay for food and clothes, let alone for electricity and district heat (annual reports for 2011, 2016–2018) (Ombudsman, Citation2011b). The country is a social state but does not implement this principle in reality (Ombudsman, Citation2011b). This estimation of the Ombudsman is justified since the social welfare is only 40 EUR per month for households without any income (Interview with a representative of the Platform against poverty, 05.06.2017). There is a 16 EUR worth of monthly energy poverty subsidy for social welfare recipients after having paid the last energy bill (Official_Gazette, Citation2018).

The Ombudsman has paved the way for new legal and policy understanding of energy poverty and its human rights implications. In few annual reports, the Ombudsman raised the issue of public schools without heating which affects the educational performance and health of children (annual reports for 2014, 2017) (Ombudsman, Citation2011b). This means that energy poverty is experienced beyond the household as a unit, but in public buildings, and it is a link between the right to energy and the right to education and protection of health.

Austrian Energy Ombudsman

The Austrian Ombudsman located within the utility Wien Energie results from legislation in Austria obliging utilities to develop centers for consumers (Federal_Ministry_Republic_of_Austria, Citation2019), but at the same time results from the observation of the public utility Wien Energie about the need for improved dialogue with vulnerable consumers. I analyze the work of Wien Energie Ombudsman to support vulnerable consumers to pay their energy bills while considering their precarious situation. The results show that the Wien Energie Ombudsman located in the public utility serves as a guardian to protect vulnerable consumers and shows the crucial role of public utilities and related social institutions to support consumers in need. This section explores the role of the Wien Energie Ombudsman by explaining (1) the reasons for its establishment, (2) the definition of its target group, and (3) and the actual work with its target group. I also explain briefly the energy market and the social welfare system.

Wien Energie is a state-owned energy utility supplying district heat, gas, and electricity in Vienna. The Ombudsman reported that it is crucial for them that they are state-owned as they would not be able to take care of their consumers if they were not in public ownership: ‘We work on the open market, but we work for the citizens’ (Interview with Wien Energie Ombudsman representative 16. 03. 2017). From April 2011 till March 2017 (interview) the Ombudsman processed 17,000 requests from social institutions and clients referring to 12,000 households and had 270 networking meetings with private and public social organizations (Wien_Energie_Ombudsman, Citation2017). The collaborators of the Ombudsman have praised their work. Psychological counseling for addicts Dialog explained: ‘The Ombudsperson is an important service for materially underprivileged people which is rare to find in companies.’ (Wien_Energie_Ombudsman, Citation2017).

The Austrian state-owned energy supplier in Vienna Wien Energie has built up a team to answer the requests of its vulnerable clients. The representative of the Ombudsman explains:

We have begun in 2011 to build our team because we experienced getting more and more requests from social institutions directed to Wien Energie with special questions, and we could not offer solutions which we give to a typical customer… And we did not have sufficient know-how … Then, it was decided to build a customers’ unit here, the Ombudsperson, and to employ social workers. (Interview with Wien Energie Ombudsman representative 16. 03. 2017)

One of the key aspects of the success of the Ombudsman is its good networking with other relevant institutions. The cooperation with the social institutions reduces the bureaucracy since the consumer does not have to prove that they are facing affordability in front of the Ombudsman (Interview with Wien Energie Ombudsman representative 16. 03. 2017). The Ombudsman offers payment in installments, reduction of certain costs, such as for disconnection and warning, fast reconnection in case of need, such as for dependents on care, and payment through pre-payment meters (Wien_Energie_Ombudsman, Citation2017). In some cases, they might prevent a disconnection (Interview with Wien Energie Ombudsman representative 16. 03. 2017).

The key achievement of the Wien Energie Ombudsman is the development of the criteria for ‘severe social case’. This notion is broader than energy poverty and is a customer who fulfills any at least three different sub-criteria out of six main criteria (income, illness, housing situation, family situation, debts, and life crises) in (Interview with Wien Energie Ombudsman representative 16. 03. 2017). The work of the Ombudsman complements a strong social welfare system and a liberalized energy market. The social welfare system is developed to accommodate different needs, such as attendance allowance, child allowance, guaranteed minimum income, heating allowance (Wien_Energie_Ombudsman, Citation2017). A consumer with arrears can refer to the basic supply for electricity and gas, meaning they will have to get a contract despite having arrears (Interview with a representative of the university JKO Linz, 23.03. 2017; with a representative of the Ministry of Social Affairs, 22.03.2017). The process of disconnection is legally regulated with a warning period that precedes it (Interview with a representative of the energy regulator E-Control, 23.03.2017; with a representative of the Ministry of Social Affairs, 22.03.2017).

Table 2. Main and their sub-criteria defining a severe social case according to Wien Energie Ombudsman.

To concretely illustrate their work with their clients – the severe social cases, Wien Energie Ombudsman provided a few real cases of clients’ requests and the response of the Ombudsman. One edited example is given in . It shows that the Ombudsman does not offer to forgive debts, but works on developing complex and sustainable solutions in cooperation with the consumer and social institutions which would allow the consumer to pay their bills.

Table 3. A real example of a severe social case’s request and the response from Wien Energie Ombudsman.

Discussion

I have proposed a new conceptual framework to apply procedural energy justice to energy poverty. I did this by integrating broader energy justice discussions about the role, responsibility, and features of formal institutions and the agency of citizens along with energy citizenship literature; the right to energy discussions about the relationship of institutions to affordable energy; and the impacts of distributive and recognition justice on procedural justice. I place the Ombudsman, represented in this article with a typical independent Ombudsman observing human rights, and an untypical one, being a special unit within a state-owned energy utility, among formal institutions to study their contribution to detecting, preventing, or creating energy poverty.

The proposed conceptual framework defines procedural energy justice applied to energy poverty to be about how institutions treat citizens over access to affordable energy, and how citizens are (dis)empowered by that relationship. The energy justice scholarship opens up the discussion on the good governance of institutions (Sovacool et al., Citation2017; Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2015), emphasizing their responsibility and capacity (Rawls, Citation1971). This adds to the capacity assessment of relevant formal institutions, such as institutions in energy policy-making, energy regulation, energy supply, and social institutions to be just or unjust by rectifying or creating inequalities. The Ombudsman as an independent body can play a crucial role in detecting injustices and as a body within an energy utility can contribute to alleviating energy poverty.

The proposed conceptual framework highlights the agency of citizens. Energy justice brings out the moral and human aspects of the energy transition (Jenkins et al., Citation2018; McCauley et al., Citation2019; Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2015) and the questions of retribution and resistance (Heffron & McCauley, Citation2017; Sovacool et al., Citation2017). The energy citizenship literature points out that a citizen is left disempowered if it is only reduced to a consumer (Lennon et al., Citation2019; Ryghaug et al., Citation2018). Citizens have multiple roles in society and should not be seen only as able to afford their energy bills. They have the right to participate (Walker & Day, Citation2012) and enjoy a dignified life. The case studies have shown that the independent Ombudsman found the right to a dignified life of (vulnerable) citizens to be more important than their role as consumers, and the utility-based Ombudsman created mechanisms to reach out to vulnerable citizens and consider their precarious life situation before demanding them to pay their energy arrears.

One of the key aspects of the proposed conceptual framework is the assessment of the impacts of distributive and recognition energy justice on procedural energy justice, and how they amplify procedural (in)justices. Recognition justice being about identifying who is vulnerable (Jenkins et al., Citation2016; Walker & Day, Citation2012) impacts procedural justice through the size of the energy-poor population. In the case of North Macedonia where material deprivation and energy poverty affect a large share of the population, they magnify the level of ambition needed to tackle energy poverty through institutional policies. Distributive justice which is about the location of injustices (Jenkins et al., Citation2016) and unequal access to energy services (Walker & Day, Citation2012), affects the fairness of the process and decisions through the institutional setup creating (un)equal access to energy. Certain institutions and institutional-set ups are energy poverty drivers. The energy market structure (monopolized or not), the ownership of utilities (state or private), and the strength of the social welfare system determine to which extent will formal institutions practice policies which affect citizens positively.

Lastly, a crucial aspect of procedural energy justice is how formal institutions treat access to energy and how the policies they create affect vulnerable citizens regarding access to affordable energy. Some institutions practice neo-liberal energy policies and treat energy as a commodity that citizens need to be able to afford no matter their personal circumstances. The independent Ombudsman detected that the energy monopolies were unjustly treating citizens only as consumers, and even employing enforcement agents to collect the energy debts, even from materially deprived citizens on social welfare assistance. Other institutions go beyond the market relations (Walker, Citation2015), and practice the right to energy concept (EPSU & EAPN, Citation2017; Hesselman et al., Citation2019), thus consider affordable energy to be an essential human need. The utility-based Ombudsman has studied the need of its vulnerable consumers, developed criteria to identify them by considering their entire life situation, proposed measures to secure their energy access and enable mechanisms for them to pay their energy arrears. A crucial output of procedural energy justice is whether citizens are protected from energy disconnections. The utility Ombudsman considers energy access as one of its main goals, while the independent Ombudsman draws attention to energy monopolies that misused their position to disconnect citizens with arrears and even citizens who regularly pay their bills.

Conclusion

Drawing on procedural energy justice applied to energy poverty with insights from more general energy justice, energy citizenship, and the right to energy literature, I have explored the role of two different Ombudsman entities (independent and utility-based) existing in different contexts (North Macedonia with high and Austria with low energy poverty levels) in tackling energy poverty and exposing energy injustices. Through the independent Ombudsman’s lenses, I have found out hidden institutional energy poverty drivers to be energy monopolies and the weak social welfare system. The utility-based Ombudsman has shown to support vulnerable consumers in paying back their energy debts while protecting them against disconnections. Against the background of illustrating cases with different development of the social welfare system and different market structures, the Ombudsman discovers that these two institutions can alleviate or create energy poverty. The energy utility plays an especially relevant role in creating or preventing energy injustice since in the case of North Macedonia the utility has been identified as the key institutional driver of energy poverty as reported by the independent Ombudsman. On the other hand, the Austrian Ombudsman is located within the utility and plays an emerging role in reducing energy poverty. The article shows that the Ombudsman is a new and under-explored actor in detecting energy poverty (Hesselman & Herrero, Citation2020).

The Macedonian case showed that the independent Ombudsman is a protector of consumer rights and vulnerable consumers by pointing out the private district heat and electricity monopolies and the social welfare system because they are creating injustices, however, it has a low impact on rectifying these injustices. The relevance of the Ombudsman’s work in North Macedonia is in the development of new legislation that improves the level of consumer rights. The Ombudsman has also explicitly mentioned that human rights are endangered in cases of disconnections and weak social welfare protection, and it hinted at the case that energy poverty can be experienced outside of the household with health and educational implications. It showed that a broader scope of citizens including regular payers can be affected by energy injustices, such as in the case with collective disconnections. The Austrian utility-based Ombudsman is a result of legislation to protect vulnerable consumers but also due to the awareness of the public utility to deal with consumers unable to pay their energy bills. The Austrian Energy Ombudsman by developing a broad definition of a severe social case has internalized the human rights approach to considering energy services as a necessary (human) need.

The case studies tried to show the complex contextual environment in which the Ombudspersons operate. The article acknowledges that no generalization is possible, however, it clearly shows the asymmetry of the energy markets and the social welfare systems in both countries which either support or entrap consumers in (un)just policies. On one hand, we have a well-developed welfare state with public utility leading the fight against the inhuman treatment of energy consumers, and on the other weak social welfare system where energy monopolies in private ownership inflict injustices on citizens and go unpunished. In North Macedonia, the energy supplier sees citizens mainly as energy consumers who need to pay their energy bills, but the Austrian energy suppliers have shown that energy affordability challenges are to be solved on the liberalized market by enabling everyone to pay their energy bills but offering them a human approach. It shows that one of the key institutions is the energy supplier which can be just or unjust depending on whether it practices the right to energy concept (Hesselman et al., Citation2019; Walker, Citation2015).

Finally, I have extended the understanding of procedural energy justice. It is more than access to information, participation in the decision-making, and access to legal rights (Walker & Day, Citation2012), but it is about the relationship between formal institutions and citizens over affordable energy. Procedural energy justice applied to energy poverty is how institutions treat citizens over access to affordable energy, and how citizens are (dis)empowered by that relationship. Procedural energy justice demands just institutions and policies to lead a socially just energy transformation. This requires structural reforms (Guyet et al., Citation2018), a rethinking of the neo-classical economics system (Heffron et al., Citation2015) which co-produces energy poverty, and re-shift from the personal situation of the energy-poor to the policies and institutions which co-shape energy poverty (Petrova, Citation2018).

This article paves the way for further research about the role and contribution of Ombudspersons in detecting energy injustices and alleviating energy poverty. In Europe, few good examples of Ombudspersons exist in safeguarding energy-poor citizens from energy injustices, such as the Belgian, French, Spanish, and UK Ombudspersons. Although they appear in projects and policy work, their role and contribution have rarely been part of academic studies. Further research would benefit from learning about their practical work and their success stories of alleviating energy poverty.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the interviewees and the editors of the special issue for their cooperation. The author would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and very useful feedback. Part of this work was presented at a conference organized by the ENGAGER network. Because this article was developed from the author's dissertation, the author is very grateful for the support of her supervisor Prof. Michael LaBelle. The author is especially grateful to Central European University for funding the open access.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ana Stojilovska

Ana Stojilovska (Central European University) has been studying the synergies between energy poverty and energy justice in developing and developed European contexts. Her research interests include an anthropological human-centered approach to studying energy poverty in the context of the energy transition, as well as questions of (in)justice and equity concerning infrastructure, heating, and fuel use.

References

- Bouzarovski, S., & Petrova, S. (2015). A global perspective on domestic energy deprivation: Overcoming the energy poverty–fuel poverty binary. Energy Research & Social Science, 10, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.06.007

- Bouzarovski, S. (2014). Energy poverty in the European Union: Landscapes of vulnerability. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Energy and Environment, 3(3), 276–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/wene.89

- Bouzarovski, S. (2018). Energy poverty: (Dis)Assembling Europe’s infrastructural divide. Palgrave Macmillan. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/%2F978-3-319-69299-9.pdf

- Bouzarovski, S., & Simcock, N. (2017). Spatializing energy justice. Energy Policy, 107, 640–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.03.064

- Bouzarovski, S., Tirado Herrero, S., Petrova, S., & Ürge-Vorsatz, D. (2016). Unpacking the spaces and politics of energy poverty: Path-dependencies, deprivation and fuel switching in post-communist Hungary. Local Environment, 21(9), 1151–1170. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2015.1075480

- Bouzarovski, S., & Tirado Herrero, S. (2017). The energy divide: Integrating energy transitions, regional inequalities and poverty trends in the European Union. European Urban and Regional Studies, 24(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776415596449

- Bulkeley, H., Carmin, J., Castán Broto, V., Edwards, G. A. S., & Fuller, S. (2013). Climate justice and global cities: Mapping the emerging discourses. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 914–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.05.010

- Demski, C., Thomas, G., Becker, S., Evensen, D., & Pidgeon, N. (2019). Acceptance of energy transitions and policies: Public conceptualisations of energy as a need and basic right in the United Kingdom. Energy Research & Social Science, 48, 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.09.018

- Energie_Control_Austria. Energy poverty in Austria definitions and indicators. https://www.e-control.at/documents/1785851/1811597/Energiearmut_Definitionen+und+Indikatoren_14082013_en.pdf/e91ed391-719f-469a-b16e-6f74703de96b?t=1438105557837

- Energy_and_Water_Services_Regulatory_Commission. (2009). Annual report for 2008. https://www.erc.org.mk/odluki/2IZVESTAJ%20ZA%20RABOTATA%20NA%20RKE%20VO%202008%20GODINA.pdf.

- Energy_and_Water_Services_Regulatory_Commission. (2019). Annual report for 2018 (http://www.erc.org.mk/odluki/2019.04.25%20GI%20za%20rabotata%20na%20RKE%20za%202018%20godina-final.pdf

- EPSU, & EAPN. (2017). Right to energy for all Europeans! (http://www.epsu.org/sites/default/files/article/files/Right%20to%20energy%20web%20reading%20-%20EN.pdf

- EU_Energy_Poverty_Observatory. (2020a). Indicators and data https://www.energypoverty.eu/indicators-data

- EU_Energy_Poverty_Observatory. (2020b). Member State Reports on Energy Poverty 2019. E. Union. https://www.energypoverty.eu/sites/default/files/downloads/observatory-documents/20-06/mj0420245enn.en_.pdf

- Eurostat. (n.d.). Database. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

- Federal_Ministry_Republic_of_Austria. (2019). Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan for Austria (https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/at_final_necp_main_en.pdf

- Frankowski, J., & Tirado Herrero, S. (2021). What is in it for me? A people-centered account of household energy transition co-benefits in Poland. Energy Research & Social Science, 71, 101787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101787

- Fuller, S., & McCauley, D. (2016). Framing energy justice: Perspectives from activism and advocacy. Energy Research & Social Science, 11, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.08.004

- Gillard, R., Snell, C., & Bevan, M. (2017). Advancing an energy justice perspective of fuel poverty: Household vulnerability and domestic retrofit policy in the United Kingdom. Energy Research & Social Science, 29, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.012

- Guyet, R., Živčič, L., Stojilovska, A., Smith, M., Horta, A., & Grossmann, K. (2018). Innovation – Introducing path-breaking perspectives to the understanding of energy poverty (http://www.engager-energy.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Engager-Brief-1.pdf

- Heffron, R. J., & McCauley, D. (2014). Achieving sustainable supply chains through energy justice. Applied Energy, 123, 435–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.12.034

- Heffron, R. J., & McCauley, D. (2017). The concept of energy justice across the disciplines. Energy Policy, 105, 658–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.03.018

- Heffron, R. J., McCauley, D., & Sovacool, B. K. (2015). Resolving society’s energy trilemma through the Energy Justice Metric. Energy Policy, 87, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2015.08.033

- Hesselman, M., & Herrero, S. T. (2020). New narratives and actors for citizen-led energy poverty dialogues (http://www.engager-energy.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/WG3-Policy-Brief_Sept-2020.pdf

- Hesselman, M., Varo, A., & Laakso, S. (2019). The right to energy in the European Union (http://www.engager-energy.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ENGAGER-Policy-Brief-No.-2-June-2019-The-Right-to-Energy-in-the-EU.pdf

- Jenkins, K., McCauley, D., Heffron, R., Stephan, H., & Rehner, R. (2016). Energy justice: A conceptual review. Energy Research & Social Science, 11, 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.10.004

- Jenkins, K., McCauley, D., & Warren, C. R. (2017). Attributing responsibility for energy justice: A case study of the Hinkley Point Nuclear Complex. Energy Policy, 108, 836–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.05.049

- Jenkins, K., Sovacool, B. K., & McCauley, D. (2018). Humanizing sociotechnical transitions through energy justice: An ethical framework for global transformative change. Energy Policy, 117, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.02.036

- Kucsko-Stadlmayer, G. (2008). In G. Kucsko-Stadlmayer (Ed.), European Ombudsman-Institutions A comparative legal analysis regarding the multifaceted realisation of an idea. SpringerWien.

- LaBelle, M. C. (2017). In pursuit of energy justice. Energy Policy, 107, 615–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.03.054

- LaBelle, M. C. (2020). Energy cultures: Technology, justice, and geopolitics in Eastern Europe. Edward Elgar.

- Lennon, B., Dunphy, N., Gaffney, C., Revez, A., Mullally, G., & O’Connor, P. (2019). Citizen or consumer? Reconsidering energy citizenship. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1680277

- Lepsius, M. R. (2017). In C. Wendt (Ed.), Max weber and institutional theory. Springer.

- McCauley, D., & Heffron, R. (2018). Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice. Energy Policy, 119, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014

- McCauley, D., Heffron, R., Pavlenko, M., Rehner, R., & Holmes, R. (2016). Energy justice in the Arctic: Implications for energy infrastructural development in the Arctic. Energy Research & Social Science, 16, 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2016.03.019

- McCauley, D., Ramasar, V., Heffron, R. J., Sovacool, B. K., Mebratu, D., & Mundaca, L. (2019). Energy justice in the transition to low carbon energy systems: Exploring key themes in interdisciplinary research. Applied Energy, 233-234, 916–921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.10.005

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambidge University Press.

- Official_Gazette(2018). Program for Subsidizing Energy Consumption for 2019. http://www.slvesnik.com.mk/Issues/14235fb4c7b544beab9a115ee8ebc81b.pdf.

- Ombudsman. (2011a). About the Institution http://ombudsman.mk/EN/about_the_ombudsman/about_the_institution.aspx

- Ombudsman. (2011b). Annual reports http://ombudsman.mk/MK/godishni_izveshtai.aspx

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Petrova, S. (2018). Encountering energy precarity: Geographies of fuel poverty among young adults in the UK. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 43(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12196

- Punch, K. F. (2005). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Oxford University Press.

- Reif, L. C. (2004). The Ombudsman, good governance and the international human rights system. Springer Science+Business Media B.V, Vol. 79.

- Robinson, C., Yan, D., Bouzarovski, S., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Energy poverty and thermal comfort in northern urban China: A household-scale typology of infrastructural inequalities. Energy and Buildings, 177, 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.07.047

- Ryghaug, M., Skjølsvold, T. M., & Heidenreich, S. (2018). Creating energy citizenship through material participation. Social Studies of Science, 48(2), 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312718770286

- Schlör, H., Fischer, W., & Hake, J.-F. (2013). Sustainable development, justice and the Atkinson index: Measuring the distributional effects of the German energy transition. Applied Energy, 112, 1493–1499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.04.020

- Schlosberg, D. (2004). Reconceiving environmental justice: Global movements and political theories. Environmental Politics, 13(3), 517–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000229025

- Sovacool, B. K. (2015). Fuel poverty, affordability, and energy justice in England: Policy insights from the Warm Front Program. Energy, 93(Part 1), 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2015.09.016

- Sovacool, B. K., Burke, M., Baker, L., Kotikalapudi, C. K., & Wlokas, H. (2017). New frontiers and conceptual frameworks for energy justice. Energy Policy, 105, 677–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.03.005

- Sovacool, B. K., & Dworkin, M. H. (2015). Energy justice: Conceptual insights and practical applications. Applied Energy, 142, 435–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.01.002

- Sovacool, B. K., Lipson, M. M., & Chard, R. (2019). Temporality, vulnerability, and energy justice in household low carbon innovations. Energy Policy, 128, 495–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.01.010

- Stojilovska, A. (2020). Energy poverty in a subsistence-like economy: The case of North Macedonia. In G. Jiglau, A. Sinea, U. Dubois, & P. Biermann (Eds.), Perspectives on energy poverty in post-communist Europe. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Perspectives-on-Energy-Poverty-in-Post-Communist-Europe/Jiglau-Sinea-Dubois-Biermann/p/book/9780367430528?fbclid=IwAR1ISJv7llNLsqI2AS_UMFyCFGwdQUcSB0uO-MnNj5iudSvtAXYyTgT5uV8

- Teschner, N., Sinea, A., Vornicu, A., Abu-Hamed, T., & Negev, M. (2020). Extreme energy poverty in the urban peripheries of Romania and Israel: Policy, planning and infrastructure. Energy Research & Social Science, 66, 101502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101502

- Thomson, H., & Bouzarovski, S. (2018). Addressing energy poverty in the European Union: state of play and action. https://www.energypoverty.eu/sites/default/files/downloads/publications/18-08/paneureport2018_final_v3.pdf

- Thomson, H., & Snell, C. (2013). Quantifying the prevalence of fuel poverty across the European Union. Energy Policy, 52, 563–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.10.009

- Walker, G., & Day, R. (2012). Fuel poverty as injustice: Integrating distribution, recognition and procedure in the struggle for affordable warmth. Energy Policy, 49, 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.01.044

- Walker, G. (2015). The right to energy: Meaning, specification and the politics of definition. L’Europe en Formation, 378(4), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.3917/eufor.378.0026

- Walker, G., Simcock, N., & Day, R. (2016). Necessary energy uses and a minimum standard of living in the United Kingdom: Energy justice or escalating expectations? Energy Research & Social Science, 18, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2016.02.007

- Wien_Energie. (2021). Ombudsstelle. https://www.wienenergie.at/privat/hilfe-und-kontakt/ombudsstelle/

- Wien_Energie_Ombudsman (2017). Wien Energie materials.

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Yoon, H., & Saurí, D. (2019). ‘No more thirst, cold, or darkness!’ – Social movements, households, and the coproduction of knowledge on water and energy vulnerability in Barcelona, Spain. Energy Research & Social Science, 58, 101276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101276