ABSTRACT

Transitions towards low-carbon societies trigger renegotiations of justice concerns in regions that have to abandon unsustainable, fossil-based production patterns. In these transition regions, tensions may appear between inner- and supra-regional justice claims on the one hand, and recognition-based and distributional justice concerns on the other. Intermediary actors such as municipal politicians have to navigate these spatial and moral tensions. Based on qualitative data generated in the German lignite-mining region of Lusatia, ‘moral rifts’ are reconstructed that shape local perceptions of justice. These rifts help elucidate how reconciliation in this region proves to be difficult despite considerable redistributive efforts. Unless patterns of misrecognition are adequately addressed, prospects for a successful transformation of the region remain limited.

1. Introduction

The climate crisis puts pressure on fossil-dependent regions to speed up energy transitions. Yet these urgent transitions are riddled with social tensions and moral complexities. There are differing expectations of how these transitions should proceed, which are frequently expressed as justice claims, emphasizing issues such as regional and individual affectedness or political responsibility.

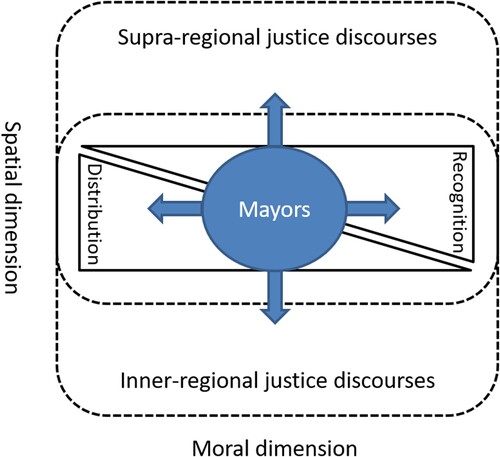

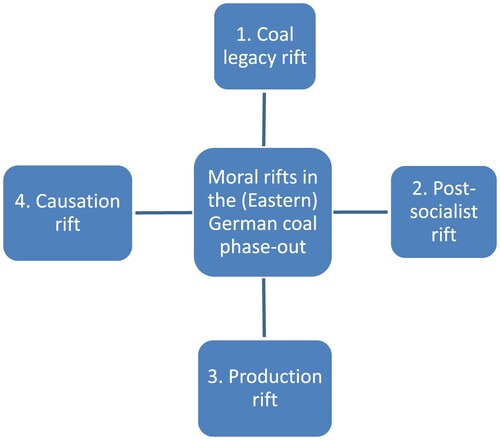

This article elucidates how actors at the intersection between inner- and supra-regional discourses respond to and shape complex, spatially and morally diverging justice claims in the tension field between distribution and recognition. These intermediary actors, such as mayors in affected municipalities, must attempt to make sense of contradictory expectations. We propose the concept of ‘moral rifts’ to capture the (re-)negotiations of conflicting moral expectations and spatial relations. Studying the region of Lusatia, Germany, we identify four moral rifts—the ‘coal legacy rift’, ‘post-socialist rift’, ‘energy production rift’, and the ‘causation rift’—that are strongly shaped by historical and cultural legacies as well as energy-related issues of production and decision-making. We find that the nexus between recognition and distribution is emphasized by intermediary transition actors, thereby stressing moral and spatial tension fields in the German coal exit policy.

This article adds to the debate about just transitions by highlighting the deeply political nature and the spatial implications of energy transitions. The analytical concept provided in this article is transferrable to other transition regions. It therefore contributes to practical ambitions of avoiding political deadlock and is helpful in further studying the morally sensitive aspects in recent phase-out decisions.

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses the relationships between distribution and recognition, based on Nancy Fraser’s theory of justice, developing our concept of ‘moral rifts’. Section 3 introduces the methodological approach, which relies on interviews with municipal actors. Section 4 outlines the context of the Lusatia case study. In our analysis (section 5), several moral rifts and their spatial implications are scrutinized, followed by discussion of the study findings (section 6) and conclusions (section 7).

2. Justice dimensions and their interrelations in moral rifts in coal transitions

Climate policy measures include plans to phase-out fossil-based energy generation and related industries. This imposes pressure on communities and regions to determine how justice should be renegotiated in such transitions: who should be recognized, how can fair processes be organized, and who should be entitled to redistribution measures? Local officials—mayors, councilors, or regional administrators—are confronted with myriad justice claims, while seeking to ensure democratic representation and responsive governance.

The claim for organizing just transitions for workers and communities, on the one hand, clearly leans towards an emphasis on distribution. On the other hand, workers in declining industries must often deal with loss of recognition in parts of the public discourse. Aspects of redistribution and recognition therefore intermingle.

The aim of this section is threefold: first, to recapitulate how environment-related justice and just transition debates conceive of the different dimensions of justice; second, to discuss the relational perspective of distributional and recognition-based justice, introduced by Nancy Fraser (Citation1997, Citation1998; Fraser & Honneth, Citation2003); and third, to set out our concept of ‘moral rifts’.

2.1. Intersecting dimensions of justice

Academic and activist debates in the environmental field have focused on issues such as environmental, energy, and climate justice and the related transitions that may be deeply political and conflictual. It is characteristic of these debates that different dimensions of justice—distributional, recognition-based, and procedural aspects—have been frequently invokedFootnote1, while their complex relationship recently emerges as a point of discussion. Nancy Fraser discusses these dimensions as ‘rival conceptions of the substance of justice’ (Fraser, Citation2009, pp. 3–4, emphasis added), of the ‘what’, and notes a threat not only of partiality, but also of incommensurability.

Theories on distributive justice consider the fair distribution of so-called primary goods, involving rights and liberties, opportunities and powers, but also wealth and income. Redistribution may be sought, for instance, from North to South, rich to poor, or between the regions of a country. Fraser suggests that maldistribution as an economic injustice overlaps with processes of cultural discrimination and status inequalities (Fraser & Honneth, Citation2003, pp. 86–87). The distribution of wealth and income is often negatively correlated with that of environmental burdens in the energy transition (Sovacool et al., Citation2016; Sovacool & Dworkin, Citation2014; Walker, Citation2012).

In environmental, energy, and climate-related fields, attention to recognition-based injustices rooted in social status inequalities (Fraser, Citation1997, Citation2009; Young, Citation1990) has increased. According to Fraser, the goal of politics of recognition is a difference-friendly world. In a nutshell, misrecognition arises ‘when institutions structure interaction according to cultural norms that impede parity of participation’ (Fraser & Honneth, Citation2003, p. 29) which can also be observed in environmental conflicts (Schlosberg, Citation2007; Walker, Citation2012). Processes of disrespect, stigmatization, and othering (Jenkins et al., Citation2018) related to the existing (mostly fossil-based) energy system as well as to low-carbon transitions need careful consideration (McCauley et al., Citation2019).

In addition to recognition- and distribution-based concerns, the procedural dimension of justice looms large, which includes access to information, meaningful participation in decision-making, lack of bias on the part of decision-makers, and access to legal processes for achieving redress (Walker, Citation2012). These just procedures cannot be upheld if affected communities are not granted the necessary material or symbolic resources.

Our contribution builds on recent research in the just transition field that has argued for a greater sensitivity to tensions between sustainability and different justice dimensions in the context of transitions (Ciplet & Harrison, Citation2020). We agree with Kalt (Citation2021) that justice in transitions has different meanings for different actors, and that there are discursive struggles around them. The notion of striving for a just transition (Heffron & McCauley, Citation2018; McCauley & Heffron, Citation2018; Newell & Mulvaney, Citation2013)—rooted in labor environmentalism (Morena et al., Citation2020; Stevis & Felli, Citation2015)—is particularly relevant for communities and regions experiencing rapid changes due to climate-policy-driven transitions. Coal phase-outs are among the prime examples where just transitions are needed, given the current local dependence of communities and workers on coal extraction and combustion.

Nancy Fraser’s suggestion is to perceive of the relation between redistribution and recognition as perspectival dualist. The aim is to allow for differentiation between economic and status differences, while acknowledging their causal interaction. It would therefore be simplistic to convey ‘an either/or choice’ between ‘[c]lass politics or identity politics, [m]ulticulturalism or social democracy’ (Fraser & Honneth, Citation2003, p. 8). A fair distribution of material resources ensures participants’ independence and ‘voice’. In turn, institutionalized patterns of cultural value express equal respect for all participants and ensure equal opportunity for achieving social esteem (Fraser & Honneth, Citation2003, p. 36). Understanding the nexus between recognition and redistribution is key to determining which procedures are needed for overcoming grievances and targeting injustice claims conjointly. An appropriate response to these overlapping injustice claims needs to combine procedural, restorative and other dimensions. We further agree with Fraser’s more recent suggestion that democratic procedures are not only needed to target both distributive and recognition-based injustices. What is more, the adequate spatial scale at which justice should be accomplished often requires thorough deliberation (Fraser, Citation2009). Studying the conflictive settings of coal transition, we will therefore relate intertwined claims on the substance of justice to their spatial implications.

2.2. Spatial dimensions of regional transformations

Justice claims in transitions vary not only regarding the implied substance of justice, but also regarding the scales (Fraser, Citation2009) and scopes (Stevis & Felli, Citation2020) targeted by these claims. Citizens, decision-makers, and stakeholders discuss questions such as who is responsible and who is affected by a transition in a spatial–moral context. Related to this are normative standpoints about the level at which a just transition should occur and which groups should be entitled transition support. This cuts both ways: spatial claims are based on moral reasoning, while arguments about justice shape one’s view on spatial boundaries. Together, the moral substance of justice—and the scales at which to seek for it—shape a moral–spatial field that reveals the deeply political nature of transitions.

Our proposal for justice research is to look for what we coin ‘moral rifts’, that is, spatial divergences that are based on moral reasoning. The term helps to capture the points at which different dimensions of justice come together in the thinking and actions of local actors to justify processes of inclusion and exclusion. Moral rifts are therefore dynamic: Actors find moral rifts in regional or supra-regional discourses and appropriate or reject them to establish their own interpretations. They also emphasize the consequences for certain groups while downplaying those affecting others.Footnote2 Concretely, we identify the ‘accounts’ (Scott & Lyman, Citation1968) that combine negotiations of conflicting moral expectations and spatial relations.

As transitions towards sustainability are conflictual and power-laden (Avelino & Rotmans, Citation2009; Healy & Barry, Citation2017), not all justice demands are considered equally in political arenas. Meadowcroft observes that ‘groups with the most power, […] incumbent groups, […] may have secured extensive subsidies and political protections (for example […] much of the fossil fuel industry)’ (Meadowcroft, Citation2007, p. 308). The role of local governments should then be to pursue a reflective governance style through transcending particular interests and constructing an understanding of the public good (ibid., Citation2007, p. 309). Overall, calls for just transitions frequently (though not always) concentrate on specific local and regional settings, which grants local governance actors including municipalities a great responsibility in working towards them.

Our concept of moral rifts builds on several fields of study. In political sociology, a host of contributions have emerged around the notion of cleavages. This term captures how socioeconomic inequality is connected to patterns of political mobilization and cultural recognition (Lipset & Rokkan, Citation1967). A recent global survey by Thomas Piketty and others shows how education and cultural status increasingly shape the way that income inequalities influence election results (Gethin et al., Citation2021). While these authors capture the spatial dimension mostly by state borders, interpretative approaches show how differences between and within cities and regions are articulated and potentially re-interpreted in processes of political polarization. This includes Hochschild’s (Citation2018) analysis of ‘empathy walls’ between urban Democrats and rural Republicans in the US, or Mau’s (Citation2019) observation of ‘fractures’ that characterize East Germany as a post-socialist society. These terms illustrate that the mutual constitution of spatial differences and moral injustices is often tacit. Spatial inequities do not necessarily lead to open conflict. Further research, according to Göran Therborn, should therefore look at the ‘fault lines’ that lie dormant until controversial policies turn inequalities into pronounced conflicts (Therborn, Citation2021, p. 25).

Moreover, we argue in line with political geographers that cleavages are often articulated in close connection to contested processes that re-define regional borders. Lagendijk (Citation2007), among other scholars, relates the ‘omnipresence’ of the notion of regions to both structural factors as well as discursive articulations that together present a form of discursive hegemony. The recent notion of coal regions or transition regions reveals, yet again, that internal and external discourses overlap. That is, actors within and outside the affected territory constantly construct, reference, or renegotiate regional boundaries (Agnew, Citation2013). In turn, widely accepted boundaries, for example state borders, become argumentative resources for actors who seek to integrate or reject various justice dimensions. This boundary work either leads to the clarification of reconcilable positions or to a heightened perception of moral conflict.

We are thus looking at an underlying, bidirectional nexus between spatial and moral justice claims that comes to the fore in contested political processes: regional boundaries are often defined based on moral arguments, while moral arguments imply moments of spatial differentiation. With the empirical study of moral rifts, we want to trace this nexus.

2.3. Towards a relational perspective on ‘moral rifts’

As a methodological approach to capturing the nexus between recognition and redistribution, we have introduced the practice-oriented concept of moral rifts. Depending on moment and place as well as the standpoint in political space, actors communicatively test and constantly adjust their moral reasoning, thus invoking particular moral priorities and spatial boundaries. This leads to complex, locally situated and often very fragile practices of moral coordination (Thévenot, Citation2001). Particularly in value conflicts, individual and collective actors face a justification imperative (Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2000). Actors are pressurized to either organize a productive dissonance (Stark, Citation2009), to compromise, or to risk the escalation of conflicts (Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006). Local policy makers are especially likely to be held accountable for the way they combine spatial and moral frames. They serve as communicators in both directions: from a bottom-up perspective, they are representatives of their municipalities on wider national/European stages, from a top-down perspective, they rather serve as arbiters for the ways in which such higher-level discourses are taken up in local contexts.

It is important to stress that moral rifts have both a structural and a performative dimension: In communicative situations, for instance in interviews, actors invoke moral rifts that they have heard about elsewhere, while re-interpreting the claim and their own position in the field. Actors such as mayors can bridge or mend, emphasize or deepen the rifts they encounter. This response to and reconfiguration of moral tensions has a deeply spatial dimension, as actors also rely on cognitive and communicative frames to foreground or background particular scales, and their own positionality. Framing an issue using a certain scale and/or level involves processes of inclusion or exclusion through discursive claims that issues should be resolved at certain scales of regulation (Kurtz, Citation2003; van Lieshout et al., Citation2011). While this is often subconscious and non-instrumental, in situations of explicit conflict or in formal roles of responsibility, this scale framing can have a strategic dimension. Our study thus builds on recent contributions that consider aspects of scale and scale framing in local transition processes (Everts & Müller, Citation2020; Weller, Citation2019).

The broader perspective we suggest highlights the ambiguous character of socioecological transformations that affect regions unequally. We propose that moral rifts represent an ideal-typical concept for the study of just transitions: They capture the pluralist landscape of actors and trace their emergent positionalities in moments of change. The relational perspective on justice helps understanding which concrete standpoints on just transition can be found empirically. This can inform normative judgements that go beyond the polarized camps that characterize parts of the transition debate (Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2000). In the following we describe the empirical setting and our methodological approach.

3. Case construction and methodology

The present study combines several sources of qualitative empirical research to explore and describe the multi-dimensional justice concerns relevant to the local contexts. At the heart of our research is a set of eight semi-structured expert interviews with mayors in Lusatia (Bogner et al., Citation2009). The decision to focus on municipal actors is based on the assumption that mayors combine two interesting perspectives: a bottom-up perspective in which they interact with higher governance tiers up to the federal and EU levels, and a top-down perspective in which they facilitate local discourses and concerns within their districts. Navigating these intersecting discourses requires moral coordination and sense-making on the part of civic leaders. They have an active role in addressing distributive and recognition-based justice claims. On the recognition side, regional and municipal policy makers often witness cases of misrecognition and concerns about local voices not being heard in national politics. On the distributive side, mayors can work to attract investment, funding, and externally financed institutions. Their responsibilities include projecting commercial areas, building local roads, or improving the livability of their municipalities through cultural opportunities. This research focuses on the case of the Lausitzrunde, a bottom-up alliance of dozens of mayors in the active coal-mining area in Lusatia. The network represents a public arena in which mayors collectively claim recognition and attempt to organize funding for the post-coal transition at the municipal level.

Five of the eight interviews, each of 60–75 min duration, were conducted during March and April 2020Footnote3, initially in-person and subsequently (due to restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic) as phone interviews. In addition to these five conversations, three additional mayors had been interviewed in the preceding year.Footnote4 Thematically, the interview questionnaire focused on the following topics: citizens’ attitudes toward structural change in the municipality; the role of sustainability in the structural transition; municipal networks; interfaces to other governance levels; and finally, the role of citizen participation. The interview data were combined with comprehensive research on the governance processes for the decision and implementation of the coal phase-out, for instance related to the so-called ‘coal commission.’ Moreover, we attended half a dozen meetings and workshops that were organized by, or targeted at, municipal policy makers in Lusatia.

The interviews were transcribed and subsequently analyzed using MaxQDA software. The coding system was developed deductively, based on categories in line with the interview questionnaire. Specifically, we aimed to differentiate various codes of distributive and recognition-based aspects. We then looked for passages in which they intersect. At these intersections, quotations have been selected to conduct hermeneutical interpretations (Lueger et al., Citation2005). The interpretations were directed at the latent patterns of meaning (Titscher et al., Citation2003). In this process, a broad horizon of possible interpretations is contrasted with the actualized options ‘until the structure of a particular case is clear’ (ibid., Citation2003, p. 203). The plausibility of the interpretations, which are presented below as ‘moral rifts’, was discussed and reformulated in close correspondence with several colleagues investigating the same region.

4. Coal is over, what comes next? Political conditions of structural change in Lusatia

Lusatia is a heterogeneous, rural, cross-border region located mainly in the eastern part of Germany. The Sorbian ethnic minority has shaped the German part of the region for centuries, and thus multilingualism and cultural diversity are integral to Lusatia (Jacobs & Nowak, Citation2020). The region has been affected by decades-long lignite coal mining and related industrial activities, and by abrupt economic and social change in the post-socialist era. It has now entered a new phase, marked by federal laws that will phase out coal from the energy mix by 2038 at the latest (and probably earlier).

Historically, coal has shaped the region of Lusatia since the mid-nineteenth century. During the socialist era, the ‘coal and energy district’ of Cottbus was massively developed, accompanied by strong population growth and the appreciation of workers’ identities. In the course of German reunification, the uncompetitive coal sector of the former East Germany collapsed and more than 90% of the workers lost their jobs (Statistik der Kohlenwirtschaft, e.V., Citation2021). Other sectors such as textiles and glass vanished almost entirely. The economic decline led to large-scale unemployment and considerable demographic change. These developments have put municipalities in dire straits by reducing their tax income base and restricting their capacity to improve so-called soft location factors (ZWL, Citation2020). On the individual level, the post-socialist transformation has been experienced by many as a takeover accompanied by socio-cultural devaluation and ‘status-related declassification’ (Mau, Citation2019). This is an important consideration in understanding the misrecognition that still persists in parts of eastern Germany. Past negative experiences affect the readiness to accept and shape a renewed structural change process.

The devastating climatic impact of lignite combustion has led to increasing mobilization against coal in recent years. Since 2018, the nation-wide ‘coal commission’ discussed pathways for the phase-out of coal, structural support for affected regions, and energy policy implications (Gürtler et al., Citation2021). The recommendations of the commission were implemented more than a year later by the German federal government through the Act to Reduce and End Coal-Fired Power Generation and a Structural Development Act. Coal-dependent regions in Germany will receive €40 billion as support for the transition (of which €17 billion is earmarked for the region of Lusatia), while workers and coal utilities will be compensated. The compensation packages are more generous than in other countries that are implementing a coal phase-out (Nacke et al., Citation2021). The governance structureFootnote5 for the accelerated structural change has a focus on the effective distribution of economic support through federal and state ministries.

An indicator that misrecognition restricts the readiness to engage in political debate and transition activities is that the region has seen strong populist mobilization in recent years. The partly authoritarian, partly right-wing-extremist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD; Alternative for Germany) opposes the coal phase-out, and incites anti-immigrant and anti-elite sentiments. AfD became the most successful political party in the region during the state-level elections of 2019.

5. Justice claims in Lusatia

In the following, we present qualitative insights into our interviews. We highlight the role of local policymakers, interrelate moral and spatial aspects, and introduce four moral rifts.

5.1. The moral substance of justice—distribution first, recognition second?

In the interview material, mayors refer strongly to the nexus of distribution and recognition by emphasizing that the latter is recently underestimated. Although they anticipate considerable transition funds for affected municipalities, they expect that administrative constraints, negative historical experiences, and deficient governance concepts will hinder their local efficacy. In this context, mayors claim that overcoming financial deficits would be only a first step in addressing the lack of trust that citizens place in public institutions. One interview partner shows understanding for disenchanted citizens and their ‘sensitivities, because [these citizens] lost in this process after 1990, they see themselves as losers’ (I2), and proceeds to reflect upon a widespread sentiment in the region ‘that money alone will not suffice’. One of her colleagues goes so far as to consider the funding schemes as a bribe:

And it is an impertinence that the one who has made the decision does not mitigate the consequences of the decision, but—and I say this quite deliberately—wants to buy his way out of his responsibility. That is outrageous. Outrageous. […] The EU and the federal government must develop the concepts here and […] must not push this responsibility into the region. That is indecent. (I3)

5.2. The divide between inner and outer justice and the homogenization of a region

The rifts we identify in this paper reflect different spatial claims expressed in inner- and supra-regional discourses. The study of the Lausitzrunde municipal network demonstrates how mayors respond to these discourses. At the same time, they purposefully seek to redefine the target region under transition. By reinterpreting spatial inclusion and exclusion, they implicitly determine which communities can rightfully claim compensation for their losses in the process of phasing out coal.

captures both moral and spatial aspects of justice. The moral dimension refers to distribution-and recognition-based aspects of justice, which are interconnected, yet appear in different proportions. The spatial distinction emerges from the observation that our interview partners often draw an explicit or implicit line between inner- and supra-regional concerns.

Another aspect that intricately combines spatial and moral exclusions is the aim of most local representatives to speak with one voice. This is one of their key strategies in negotiating adequate support vis-à-vis higher political levels.Footnote6 This describes the external dimension. In the inner-regional context, however, distinct issues of economic distribution and social status subordination arise; below the surface, the region is diverse in demographic, spatial, and political aspects. Our interview partners, who represent local communities, are positioned directly at the intersection of internal diversity and external representation.

Both aspects represent the key functions of the bottom-up municipal network called Lausitzrunde. Mayors have the dual task of organizing outside financial support and recognition on the one hand, while ensuring local unanimity and the avoidance of conflict on the other. Regarding external visibility, mayors assert that the network has the ‘function […] to take people along and to be the political voice for these people’ (I3) at the state and federal level. The Lausitzrunde and its representatives have, for example, established regular meetings to coordinate negotiations with state-level or federal policy makers. The appointment of one of the spokespersons of the Lausitzrunde as a commissioner for the German ‘coal commission’ was a remarkable opportunity for the mayors’ network. Furthermore, members of the Lausitzrunde have collectively signed the European ‘Declaration of Mayors on Just Transition’. The necessity for this intense coordination can be seen in the context of past frustration and the perception of being disregarded. Related to the function of providing a political voice for local concerns at higher political levels is the objective of organizing the maximum level of economic support for the region at the national level. The considerable funding for the region as a result of federal policies demonstrates that regional policy makers successfully gained national attention over the last years.

On the inner-regional dimension, mayors in Lusatia worry about the risk that internal quarrels over funds and resources might compromise the authority of the alliance to represent the region as such. One interviewee (I3) fears that ‘as soon as we have a dispute, the political perception instrument will no longer be perceived [sic], because the state governments and the counties say: “look, they already disagree among themselves,”’ (I3) which would mean the end of the municipal alliance.

The goal of having the region speak with one voice carries the risk of obscuring the inner-regional diversity of a heterogeneous region such as Lusatia. This becomes obvious when one mayor describes a discussion with the spokesperson of an environmental activist group after a film screening. He recalls:

And then I talked to the lady, I say, ‘Look at these two.’ One of them I went to school with and the other one, I know him well because [… he works] as a mechatronic engineer […] in the power plant […] They have worked for almost 40 years in the company; I know them. But the ones you are bringing in, I don't know them. And when you ask some of these people, ‘Why are you here, do you know anything about lignite?’ … they yell ‘No,’ ‘it’s dirty here! It's just crap!’ You don't get reasonable answers. People talk about us, but not with us. (I1)

As a municipal network the Lausitzrunde considers itself as uniting the subregions that are affected by the loss of coal industries. They even equate themselves with those ‘core communities’ that will be most affected by the coal phase out. This definition excludes areas that are more distant from the coal sites. The identity of the region as a ‘coal region’, which has been dominant in recent history, is yet again articulated in order to receive transition benefits. This claimed unity can additionally rely on the perceived maldistribution in the context of rural development, and a perceived shaming of local coal workers. However, the homogeneous framing disregards those places that are relatively remote from open pit mines and power plants and overshadows other sources of identity. Furthermore, even within the same geographical reference areas, particular groups are tacitly excluded by the positive reference to the previous benefits of the coal industry. Among the groups overlooked by such a ‘coal narrative’ are those who have lost their homes, and even entire villages, located in the path of devastating surface-mining operations. One particular group that has suffered strong cultural and socioeconomic loss due to coal mining is the Sorb ethnic minority. Our interview partners partially acknowledge that the unevenness of these various impacts has divided village communities and even families (I4, I7). Yet, local political institutions and communities have been largely unable to find a productive way to involve these misrecognition experiences on an equal footing. Other groups with justified claims for greater recognition are also marginalized, for instance through a gender bias (F wie Kraft, Citation2020) or through the underrepresentation of the younger population (Luh et al., Citation2020) in the decision-making procedures for the transition in Lusatia.

This indicates how local discourses among policy makers pay comparatively little attention to internal diversity, thereby accepting a risk of reifying a homogenizing and exclusive view on the region, as discussed in section 6. Moreover, the presented insights highlight the difficulty of determining appropriate scales for addressing justice concerns (Fraser, Citation2009).

5.3. Moral rifts in Lusatia

The perspectival dualist understanding of redistribution and recognition sheds light on an ethical and social nexus that emerges in locally specific ways. We will now turn to the moral rifts that result from the dual pressure of transition funding on the one hand and the perceived absence of equal recognition on the other. Altogether, four rifts that are specific to the conducted interviews have been identified (). However, these are neither exhaustive for the region nor account for all dimensions of energy transitions. There are likely to be additional rifts that were less prominent in the empirical material.

The following quote neatly unravels those various dimensions and the underlying spatial dynamic:

‘We who work in the coal industry do a lot to ensure energy security, so that the cell phones in Berlin work, that everyone can set up their co-working spaces everywhere: We supply the energy.’ And it is a very negative image that is directed […] at the city of Berlin specifically. […] where thirty percent vote Green, but there is not even a wind turbine in Berlin. (I3)

‘We do something for prosperity, namely energy, but we are the bad guys who destroy the future of children and grandchildren because we do it with natural resources … or CO2, climate change […].’ And everyone here knows that coal has no future. But who is going to say that out loud? (I3)

And here, of course, there are again fears that facts are being created again, money is being invested that our grandchildren may not need for infrastructure. So we need a broad discussion, and civil society must be taken seriously. (I8)

Secondly, there is another historical dimension that we coin the ‘post-socialist rift’. Coal regions in East Germany and other parts of Central and Eastern Europe experienced the shock of rapid and devastating transformation during the 1990s. Although economic injustices were the most prominent, many East Germans also experienced social insecurity and status subordination (Engler, Citation1999; Willisch, Citation2008) that still persist in part and have been passed down through subsequent generations. In post-socialist regions with declining industrial cultures this refers to a specific set of experiences of the past. A mayor of a severely affected town explains why some residents have low expectations towards the transition:

They see again, we are marginalized again. Again, nobody cares about us. Blooming landscapes were promised; but everyone had a different idea of what blooming landscapes are. We have them, sure, everywhere … But nobody meant that. So this is a constant struggle to really take people along and say: Come on, now we take care of this, then we'll tackle the next problem, and so forth. (I2)

Thirdly, the devaluation of industrial labor and related lifestyles in the wake of the energy transition (first ‘legacy rift’) is closely related to what we call the ‘production rift’. Energy consumers in urban centers and rural areas have different spatial and social relationships to energy production. Our interviews suggest that on average close proximity to mining sites and perceived distance from energy-intensive metropolitan areas leads to a more positive valuation of fossil energy. The interviewee (see the first quotation in this sub-section above) contrasts the coal industry with relatively new technologies and concepts—such as the mobile phone or the cultural and professional novelty of co-working spaces—which are partially powered by fossil fuels. The interviewee sees the rise of creative and digital lifestyles, which he clearly associates with an environmentally progressive population in the nearby capital of Berlin, as a process of exploiting yet simultaneously de-valuing the coal industry. However, he claims that the energy-intensive lifestyles among cosmopolitan Berliners are just as unsustainable as the energy production that they condemn yet benefit from.

The fourth rift found in our interviews distinguishes between those groups that have actively called for the energy transition and those that are paying for it. We call this the ‘causation rift’. This was already mentioned in an earlier quotation presented above (‘the one who has made the decision does not mitigate the consequences of the decision’, I3). The same interviewee alludes to this rift when he describes the voting behavior of an urban population that is otherwise unrelated or socially and spatially detached from more rural and industrial communities. Political recognition is—in this view—primarily assigned to the call for environmental transformations, not to the industrial labor that underpins Germany’s economic stability. Another local mayor points out that the producers of affordable energy even feel like second class citizens in the process of shifting the burden away from urban communities:

And I can also stand up in Berlin […] or […] Potsdam and say, ‘well, we really need to get out of coal’. We would have to do it all through renewable energies, wind turbines, no problem. Yes, if the thing is not on our own doorstep, I can make such demands. (I2)

The promise of financial redistribution, which only became possible through the decision to phase out coal, cannot compensate for the perception of misrecognition. Many mayors want to act as both cultural caretakers and political entrepreneurs. They thus emphasize their loyalty with an arguably marginalized population and connect it to their instrumental interest in acquiring large transition funds.

Altogether, the four rifts show that local policy makers—who represent the first point of contact for local justice claims—struggle to embrace a federal policy approach that overwhelmingly follows the principles of distributive justice. In their view, transition funds alone are insufficient to appease the very conflicts they have to manage in daily face-to-face interactions. The rifts also demonstrate how moral struggles in Lusatia are articulations of larger debates such as the political–ideological conflicts between cosmopolitan and communitarian communities, and the rise of populism in disadvantaged regions (Goodhart, Citation2017). Several of the interviewees themselves draw a historical connection between perceptions of neglect and the rise of populism:

This human frustration is also one of the central reasons why a huge number of thirty percent voted AfD here. They don't vote for AfD because they are all on the far right or because they are climate deniers. Instead, they vote for AfD because [the AfD] reflects an attitude to life, namely: ‘Here is someone who will take care of us for a change’. They don't actually do that—the [AfD] proposals in my town are all catastrophic. But that's the feeling that people have. (I3)

6. Discussion

From an outside perspective, Lusatia’s position may seem comfortable to many. Significant redistributive efforts are being undertaken, particularly on a national level. Yet, standalone redistribution policies are insufficient although they constitute a necessary condition to ensure participation parity (Fraser & Honneth, Citation2003). So how to specify the moral-spatial debate that currently occurs in well-funded transition regions such as Lusatia?

Many of our interviewees on a local level reject the notion of appeasing conflicts through generous funding. Sincere concern about being overlooked and misjudged once again is mixed with skepticism about whether municipalities can benefit from the extensive funding. Moreover, local energy transitions relate to broader debates about the legitimate funding approach to sustainable transformations, about the differences between cities and countryside, and about cultural discrimination (often referred to as identity politics). This broadly implies questions regarding democracy and just transition, while local policy makers face very concrete challenges with regard to funding and social cohesion. In the following, we discuss how energy transitions can be broadly framed and locally studied.

6.1. Transformative change beyond populist appropriation?

Nancy Fraser has suggested that transformative policies, by contrast to affirmative ones, seek to eliminate inequities at the root causes (Fraser & Honneth, Citation2003, pp. 72–82). Her approach endorses a broad program of inter- and intragenerational justice that goes beyond piecemeal solutions for affected workers. Energy transitions, in this view, can integrate redistributive and recognition-based strategies and provide the ground for later, more radical, change, for instance regarding structural inequities between cities and countryside, or global North and global South. Our study confirms the need for such a broader perspective in three fundamental ways.

First, distributive efforts need to be closely integrated with recognition-based efforts. In Lusatia, such a more forward-looking politics of recognition would need to set in motion processes that value not only workers’ identities but also the diverse experiences of misrecognition that are not necessarily coal-related, for instance regarding gender, ethnic belonging, or experiences of discrimination. Whether a broadened approach can be successful in the sense that it goes beyond reifying tendencies and critically engages with human–nature relationships is a contingent and political question. The inclusion of misrecognition is but one (although often under-represented) aspect that is needed to achieve greater participation parity and fairer transitions.

Second, recognition-based justice claims need to be critically scrutinized in order to avoid tendencies of exclusion by inclusion. Indeed, the interviews in Lusatia explicitly show how the recognition-based claims emerge from an incumbent position: on the one hand, those who previously enjoyed a privileged position now fear economic decline and status subordination. Within municipalities that consider themselves as part of a relatively homogeneous coal region, incumbent groups have become more visible than other voices. On the other hand, rather marginalized voices–among them citizens whose villages have been displaced in the name of extractivist industries as well as parts of the Sorbian minority–are largely unable to successfully challenge incumbent positions at the local level. Historically inherited positionalities and multi-dimensional power relations therefore need to be taken into account when analyzing claims for greater recognition-based justice. At the same time, mayors represent key agents of societal inclusion, innovation, and local climate policies, so that their points of view need to be understood and discussed, even if they entail problematic claims.

Third, the recent rise of right-wing populism comes with the risk that rightful claims to recognize local communities may overlap with problematic claims of homogeneity and exclusion. Fraser has warned of the danger of a ‘communitarianism that […] simplifies and reifies group identities’ (Fraser & Honneth, Citation2003, p. 91). Indeed, some of our interview passages resonate with populist figures of thought (Müller, Citation2017): the ideas of a voiceless people dominated by disconnected elites, a relatively homogeneous territory and population, and the prioritization of natives or locals being more entitled to redistribution benefits than alleged outsiders. This must be noted although the interviewed mayors emphasize their distance from populist parties. These motives are clearly reminiscent of historical and contemporary far-right movements, but they also allude to very concrete and historically based experiences of subordination. Populists in Lusatia instrumentalize hegemonic claims for recognition, especially the expressed distinctions between rural populations and urban elites, and between Eastern and Western Germany. However, it is possible to respond to recognition deficits without falling into populist argumentation patterns. Therefore, claims for recognition, which are plausibly raised given the troubled history of Lusatia, must be openly discussed and critically distinguished from populist narratives.

Just transitions in this view need to combine distribution and recognition, critically scrutinize local identity claims and be specifically cautious of rhetorically homogenizing the affected regions. Against these insights, studying moral rifts is a critical addition to the toolkit of interpretative policy analysis, which is suited to study the localized connections between climate change, the social consequences of climate policy, and populism.

6.2. Moral rifts as a methodological innovation

The discussion and the empirical insights suggest that the concept of moral rifts is a methodological innovation to capture the role of intermediary actors at the intersection between local and global justice discourses. It builds on earlier just transition research, uses sociological methods of interpretative analysis and connects it to Fraser’s theory of justice. The concept is suited to reconstruct and interpret actors’ perspectives in the midst of various justice debates, while maintaining a critical distance to the overall interplay of political and ethical standpoints. This approach can specifically add to the emerging field of research that studies the nexus of right-wing populists and local sustainable energy transformations (Fraune & Knodt, Citation2018).

Moral rifts represent a transferrable concept for jointly analyzing spatial and moral justice claims, thereby adding to the academic debate on the political nature of (more versus less) just transitions. As we have demonstrated in the context of the German coal phase-out in Lusatia, justice discourses can be localized in the energy transition, while highlighting distribution and recognition aspects as equally important and mutually entwined categories. Our specific findings go back to cross-regional trends: the ‘legacy rift’ stresses cultural path dependencies that shape most coal regions, while the post-socialist experience is specific to Central and Eastern Europe. The geographic dispersion and moral ambivalence suggest that the list of moral rifts cannot be exhaustive. What is specific for Lusatia is the combination of said rifts. Future research can compare different justice-related priorities among municipal actors across regions, explore the role of further intermediary actors, trace how these intermediary actors argue and behave in different settings at different levels, or deepen understanding of the link between past harms of extractivist industries and putative compensations.

Certainly, our study has a number of limitations: the interviews were used for hermeneutic analysis, but a larger study is warranted in order to verify or extend the set of moral rifts highlighted above. This also can stimulate the discussion of the proposed framework, which will benefit from application in regions with different preconditions. Our primary focus on the redistribution–recognition nexus furthermore bears the question of which democratic and participatory processes would be useful in seeking to jointly address misrecognition and maldistribution. Together with analyzing restorative justice claims—which are relevant in cases like the one discussed here, where previous experiences overshadow the current transition—this could feature more prominently in future work.

7. Conclusion

While debates on just transitions and related issues have referred to different dimensions of justice, this contribution demonstrates how recognition-based and distributive justice claims are differently weighed in local settings. Based on Fraser’s relational approach to jointly overcome maldistribution and misrecognition, we have unfolded the complex and intertwined moral rifts in a coal-dependent region facing structural change.

In Lusatia, recent years have been shaped by attempts to position the region as speaking with one voice. From the perspective of the interviewed mayors and regional policy makers, this has proven relatively successful for maximizing federal subsidies offered for the transition. Greater recognition is claimed for the difficulties of the post-socialist transformation; for workers’ identities and the legacy of coal; for specific lifestyles that are allegedly devalued by urban communities; and for ongoing experiences of neglect and domination of the regions of the former East Germany. As these issues intersect, the specific reference points for recognition claims often remain somewhat diffuse. A number of ill-defined justice concerns emerge in regional transition settings, while many municipal actors seek to narrowly define the boundaries of the region based on its coal heritage. These homogenization efforts prevent adequate appreciation of inner-regional diversity. Another threat is the populist instrumentalization of such a homogeneous construction of the region.

We suggest that careful and context-specific analysis of moral rifts can also be conducted in a similar way for other transition regions. One way to incorporate recognition-based aspects is to foster deliberative processes as an approach to overcome both misrecognition and maldistribution. Nevertheless, the experience in Lusatia and further prospects for well-designed participation measures cannot disguise the fact that fundamental transitions bring about substantial societal struggles that often require protracted and sensitive negotiation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their research group at IASS Potsdam, in particular Dr. Tobias Haas who has contributed to conducting interviews for this article. We furthermore would like to thank all interview partners as well as the anonymous reviewers and the journal editors for their insightful suggestions and careful reading of the manuscript. We would also like to thank the participants and discussants of several conference sessions in which we presented this research. In addition, we thank Dave Morris for supporting the language editing of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Konrad Gürtler

Konrad Gürtler is a political scientist and sustainability scholar working on the societal dimension of energy transitions. He is particularly interested in the relation between justice and scale in these transitions. He is a research associate at the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) Potsdam and pursues a PhD at Radboud University Nijmegen.

Jeremias Herberg

Jeremias Herberg is a political sociologist working at the nexus between science and technology studies and sustainability studies. He is an assistant professor at the Institute for Science in Society at Radboud University Nijmegen. He studied Sociology in Vienna, Science and Technology Studies in Maastricht and received his PhD in sustainability studies from Leuphana University, Lüneburg, after a research visit at UC California, Berkeley.

Notes

1 Further dimensions of justice, such as equal capabilities (based on the work of Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum) or restorative justice—repairing the harm that has been done to an individual—are discussed within the field but will not be elaborated upon here.

2 With this conceptualization of moral rifts, we differ from Chakrabarty’s (Citation2014) understanding, who has previously used the term to capture how anthropogenic climate change challenges our ability to think on several scales and temporalities. While Chakrabarty proposes a scalar shift from global to planetary as part of the concept of the Anthropocene, we trace the local implications of post-fossil transformations.

3 In one case, the interview was carried out with a departmental head as the mayor was not available.

4 Two of these interviews were conducted by our colleague Tobias Haas to whom we owe sincere gratitude.

5 For a more detailed overview of the governance arrangements, see Haas and Gürtler (Citation2019); Herberg et al. (Citation2020, p. 22 ff).

6 Justice discourses external to the region are aggregated in this contribution, while being aware that they are certainly highly heterogeneous. They are shaped by justice claims for instance at global, supra-national, and national scales. Regional and intermediary actors perceive these claims as external to local discourses.

References

- Agnew, J. A. (2013). Arguing with regions. Regional Studies, 47(1), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.676738

- Avelino, F., & Rotmans, J. (2009). Power in transition: An interdisciplinary framework to study power in relation to structural change. European Journal of Social Theory, 12(4), 543–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431009349830

- Bogner, A., Littig, B., & Menz, W. (eds.) (2009). Interviewing experts. Springer.

- Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (2000). The reality of moral expectations: A sociology of situated judgement. Philosophical Explorations, 3(3), 208–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13869790008523332

- Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (2006). On justification: Economies of worth (Vol. 27). Princeton University Press.

- Carley, S., & Konisky, D. M. (2020). The justice and equity implications of the clean energy transition. Nature Energy, 5(8), 569–577. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-0641-6

- Chakrabarty, D. (2014). Climate and capital: On conjoined histories. Critical Inquiry, 41(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1086/678154

- Ciplet, D., & Harrison, J. L. (2020). Transition tensions: Mapping conflicts in movements for a just and sustainable transition. Environmental Politics, 29(3), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1595883

- Engler, W. (1999). Die Ostdeutschen. Kunde von einem verlorenen Land. Aufbau Verlag.

- Everts, J., & Müller, K. (2020). Riskscapes, politics of scaling and climate change: Towards the post-carbon society? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 13(2), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsaa007

- Fraser, N. (1997). Justice interruptus: Critical reflections on the “postsocialist” condition. Routledge.

- Fraser, N. (1998). Social justice in the age of identity politics. Discussion Papers, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, 98–108. https://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/wzboem/fsi98108.html

- Fraser, N. (2009). Scales of justice. Columbia University Press.

- Fraser, N., & Honneth, A. (2003). Redistribution or recognition? A political-philosophical exchange. Verso.

- Fraune, C., & Knodt, M. (2018). Sustainable energy transformations in an age of populism, post-truth politics, and local resistance. Energy Research & Social Science, 43, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.05.029

- F wie Kraft. (2020). Frauen gestalten im Strukturwandel, Männer aber mehr. Retrieved 15 December, 2020 from https://www.fwiekraft.de/index.php/blogs/frauen-gestalten-im-strukturwandel-maenner-aber-mehr

- Gethin, A., Martínez-Toledano, C., & Piketty, T. (2021). Brahmin Left versus Merchant Right: Changing Political Cleavages in 21 Western Democracies, 1948-2020. World Inequality Lab WP 2021/15.

- Goodhart, D. (2017). The road to somewhere: The populist revolt and the future of politics. Oxford University Press.

- Gürtler, K., Löw Beer, D., & Herberg, J. (2021). Scaling just transitions. Legitimation strategies in coal phase-out commissions in Canada and Germany. Political Geography, 88, 102406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102406

- Haas, T., & Gürtler, K. (2019). Der Kohleausstieg als Gemeinschaftsaufgabe für Bund und Länder. Der Fall Lausitz. In Europäisches Zentrum für Föderalismus-Forschung Tübingen (EZFF) (Ed.), Jahrbuch des Föderalismus 2019. Föderalismus, Subsidiarität und Regionen in Europa (pp. 203–216). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783748901174-203

- Healy, N., & Barry, J. (2017). Politicizing energy justice and energy system transitions: Fossil fuel divestment and a “just transition”. Energy Policy, 108, 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.06.014

- Heffron, R. J., & McCauley, D. (2018). What is the ‘just transition’? Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 88, 74–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.016

- Herberg, J., Kamlage, J. H., Gabler, J., Goerke, U., Gürtler, K., Haas, T., Löw Beer, D., Luh, V., Knobbe, S., Reinermann, J., & Staemmler, J. (2020). Partizipative Governance und nachhaltiger Strukturwandel. Zwischenstand und Handlungsmöglichkeiten in der Lausitz und im Rheinischen Revier. IASS Brochure. https://doi.org/10.2312/iass.2020.037

- Hochschild, A. R. (2018). Strangers in their own land: Anger and mourning on the American right. The New Press.

- Jacobs, F., & Nowak, M. (2020). Mehrwerte schaffen. Wie der Strukturwandel in der Lausitz von der sorbisch-deutschen Mehrsprachigkeit profitieren kann. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 6-7, 40–47.

- Jenkins, K., Sovacool, B. K., & McCauley, D. (2018). Humanizing sociotechnical transitions through energy justice: An ethical framework for global transformative change. Energy Policy, 117, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.02.036

- Kalt, T. (2021). Jobs vs. Climate justice? Contentious narratives of labor and climate movements in the coal transition in Germany. Environmental Politics, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1892979

- Kurtz, H. E. (2003). Scale frames and counter-scale frames: Constructing the problem of environmental injustice. Political Geography, 22(8), 887–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2003.09.001

- Lagendijk, A. (2007). The accident of the region: A strategic relational perspective on the construction of the region’s significance. Regional Studies, 41(9), 1193–1208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701675579

- Lipset, S. M., & Rokkan, S. (1967). Party systems and voter alignments. Cross-national perspectives. Free Press.

- Lueger, M., Sandner, K., Meyer, R., & Hammerschmid, G. (2005). Contextualizing influence activities: An objective hermeneutical approach. Organization Studies, 26(8), 1145–1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605055265

- Luh, V., Gabler, J., & Herberg, J. (2020). Sie wollen bleiben. IASS Workshops mit Auszubildenden in der Lausitzer Braunkohleindustrie. Retrieved 15 December, 2020 from https://www.iass-potsdam.de/sites/default/files/2020-10/IASS_Studie_Lausitz_SieWollenBleiben_Final_201029_2.pdf

- Mau, S. (2019). Lütten Klein: Leben in der ostdeutschen Transformationsgesellschaft. Suhrkamp Verlag.

- McCauley, D., & Heffron, R. (2018). Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice. Energy Policy, 119, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014

- McCauley, D., Ramasar, V., Heffron, R. J., Sovacool, B. K., Mebratu, D., & Mundaca, L. (2019). Energy justice in the transition to low carbon energy systems: Exploring key themes in interdisciplinary research. Elsevier.

- Meadowcroft, J. (2007). Who is in charge here? Governance for sustainable development in a complex world. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 9(3–4), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080701631544

- Morena, E., Krause, D., & Stevis, D. (eds.). (2020). Just transitions: Social justice in the shift towards a Low-carbon world. Pluto Press.

- Müller, J.-W. (2017). What is populism? Penguin UK.

- Nacke, L., Jewell, J., & Cherp, A. (2021, August 30–September 3). The cost of phasing out coal. Quantifying and comparing compensation costs of coal phase out policies to governments. Paper presented at the ECPR general conference, innsbruck (virtual conference).

- Newell, P., & Mulvaney, D. (2013). The political economy of the ‘just transition’. The Geographical Journal, 179(2), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12008

- Schlosberg, D. (2007). Defining environmental justice: Theories, movements, and nature. Oxford University Press.

- Scott, M. B., & Lyman, S. M. (1968). Accounts. American Sociological Review, 46–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092239

- Sovacool, B. K., & Dworkin, M. H. (2014). Global energy justice. Problems, principles, and practices. Cambridge University Press.

- Sovacool, B. K., Heffron, R. J., McCauley, D., & Goldthau, A. (2016). Energy decisions reframed as justice and ethical concerns. Nature Energy, 1, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.24

- Stark, D. (2009). The sense of dissonance: Accounts of worth in economic life. Princeton University Press.

- Statistik der Kohlenwirtschaft, e.V. (2021). Braunkohle im Überblick 1989-2020. https://kohlenstatistik.de/daten-fakten/ (last accessed on 13 Oct, 2021)

- Stevis, D., & Felli, R. (2015). Global labour unions and just transition to a Green economy. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 15(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9266-1

- Stevis, D., & Felli, R. (2020). Planetary just transition? How inclusive and how just? Earth System Governance, 6, 100065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2020.100065

- Therborn, G. (2021). Inequality and world-political landscapes. New Left Review, 129, 5–26.

- Thévenot, L. (2001). Pragmatic regimes governing the engagement with the world. In Knorr-Cetina K., Schatzki T., & v. Savigny E. (Eds.), The practice turn in contemporary theory (pp. 56–73).

- Titscher, S., Meyer, M., Wodak, R., & Vetter, E. (2003). Objective hermeneutics. In S. Titscher, M. Meyer, R. Wodak, & F. Vetter (Eds.), Methods of text and discourse analysis (pp. 198–212). Sage.

- van Lieshout, M., Dewulf, A., Aarts, N., & Termeer, C. (2011). Do scale frames matter? Scale frame mismatches in the decision making process of a “mega farm” in a small Dutch village. Ecology and Society, 16(1), https://doi.org/10.5751/es-04012-160138

- Walker, G. (2012). Environmental justice: Concepts, evidence and politics. Routledge.

- Weller, S. A. (2019). Just transition? Strategic framing and the challenges facing coal dependent communities. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 37(2), 298–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418784304

- Willisch, A. (2008). Verwundbarkeit und marginalisierungsprozesse. In H. Bude, & A. Willisch (Eds.), Exklusion. Die debatte über die Überflüssigen (pp. 64–68). Suhrkamp.

- Young, I. M. (1990). Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton University Press.

- ZWL-Zukunftswerkstatt Lausitz. (2020). Untersuchung der Rolle und Potenzialekommunaler Haushalte im Strukturwandel. Abschlussbericht. Kompetenzzentrum Öffentliche Wirtschaft, Infrastruktur und Daseinsvorsorge e. V.