ABSTRACT

Collaborative environmental governance is increasingly being used by public administrators to integrate divergent sectoral interests and deliver public goods that individual organizations would fail to deliver on their own. Yet, empirical studies on how exactly collaborative governance leads to integrative outputs remain scarce. This study applies a process-tracing methodology to test the hypothesized causal mechanism of collaboration dynamics leading to integrative output in a case of collaborative flood risk management from the Netherlands, the case of Grebbedijk. By drawing on multiple data sources, the analysis validates the mechanism and confirms that the dynamic interaction of highly functional principled engagement, sufficient shared motivation and a wide range of capacities for the joint action is a causal process linked to the successful output in the studied case. However, it also demonstrates that a set of pre-determined capacities for joint action, particularly initiating leadership, procedural arrangements and resources, were critical for the mechanism to unfold successfully. The findings of this study also suggest that well-organized processes of principled engagement facilitated by adaptive and connective leaders may compensate for lack of shared motivation among collaborating parties and succeed in delivering desired collaborative outputs without investing much in building trust and shared motivation.

Introduction

Collaborative governance flourished in environmental management over the past few decades. Public and private sectors seek to jointly develop solutions to environmental problems that expand beyond the boundaries of individual policy domains. The multifaceted nature of environmental problems (e.g. climate change or flood risk) necessitates collaboration between governmental agencies and integration across policy subsystems (McGuire, Citation2006). Although collaboration is often resource draining (Silvia, Citation2018), arguments in favor of collaborative governance are abundant in the literature (Ansell & Gash, Citation2008; Emerson et al., Citation2012). Studies increasingly advance our understanding of benefits of collaboration, being enhanced coordination of activities, effective management of common resources, creation of public values (Agranoff, Citation2008) and improved environmental outcomes (Biddle, Citation2017). Overall, it is suggested that collaborative governance leads to changes or outcomes that can be attributed to its effectiveness and success (Douglas et al., Citation2020).

Yet, understanding what those influences are and how collaborative governance caused them is challenging as it requires multiple performances to be evaluated at different periods of time (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b; Newig et al., Citation2018; Ulibarri, Citation2015). Subsequently, longitudinal studies on how collaborative arrangements perform over time, produce outputs and result in outcomes are not common in collaborative governance research (Gerlak & Heikkila, Citation2011; Ulibarri et al., Citation2020). Existing empirical studies argue that joint endeavors usually decline in participation and engagement (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2016; Scott et al., Citation2020) or reorganize themselves and restart (Imperial et al., Citation2016), while most of the constituents of collaborations, such as collaborative process, peak at the midpoint of collaboration’s lifespan (Ulibarri et al., Citation2020). Yet, this literature does not specify the consequences of these changes for collaboration’s outputs and outcomes (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2016; Ulibarri et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the myriad conditions attempting to explain the impact of collaboration might signal a lack of knowledge of its causal mechanisms. The mechanisms are understood as logically interlinked parts triggered by causes and linked with outcomes in a productive relationship (Beach & Pedersen, Citation2018). Although without an explicit reflection on temporal dynamics of collaborative governance, a few studies (Biddle, Citation2017; Ulibarri, Citation2015) demonstrate a positive effect of collaboration on output/outcome effectiveness by establishing empirical evidence for causal relationships between inputs, outputs and outcomes. Overall, the mechanism of influence that is triggered by dynamic conditions of collaborative governance and links it with outputs in a productive relationship remains underexamined.

This study explores one possible causal mechanism of producing integrative output for environmental management while considering the changing dynamics within the collaboration. Here, the integrative output is defined broadly as a result of collaborative process that integrates the interests of those engaged in generating the output. The level of integration is determined by the extent to which concerned sectors are constructively exploring and integrating different aspects of a problem by searching for solutions that create synergies. The Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance (Emerson et al., Citation2012) suggests that the dynamic interaction of principled engagement, shared motivation and capacity for joint action (CJA) is a causal mechanism leading to collaborative actions and outputs. A theory-testing process-tracing (PT) study is conducted to determine whether this causal mechanism operates in a real-life case as hypothesized. As a case, the performance of a multi-actor dike reinforcement project of Dutch Flood Protection Program (DFPP) is studied. The project, called Dike reinforcement of Grebbedijk (hereafter: Grebbedijk), entails a four-year collaboration-intensive exploration phase. During this phase, governmental and non-governmental actors worked jointly to explore and identify opportunities for linking flood safety with environmental objectives and spatial solutions on and around the dike. By exploring empirically the effects of collaboration dynamics on the development of the output called preferred alternative (PA), the causal question of whether, why and how integrative output has been produced is addressed in this article.

The analysis offers three contributions to the scholarship on collaborative governance. First, this study operationalizes, strengthens and moves one of the most referred frameworks on collaborative governance, the Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance (Emerson et al., Citation2012) towards causal analysis. By testing earlier propositions on dynamic interaction of principled engagement, shared motivation and CJA, this study validates and theorizes this causal mechanism and suggests specific qualities for these collaboration dynamics that could yield better (e.g. integrative) outputs or results. This sets a stage for further examination of causal mechanisms of collaboration dynamics leading to myriad outputs and outcomes. Second, methodologically, this study offers an approach of linking collaboration dynamics to outputs when, for example, ‘high quality’ outputs of collaborative governance should be measured. Third, this study contributes to the small cohort of longitudinal studies of collaborative processes and shows the usefulness of PT methodology in unpacking collaboration dynamics over time.

Outputs of collaborative environmental governance

Increasingly, researchers study not only collaborative processes but also what collaboration delivers as outputs (e.g. Ulibarri, Citation2015). They make use of logic models for assessing collaboration and distinguishing outputs from outcomes when measuring the performance of collaborative arrangements (Biddle, Citation2017). By definition, outputs are products and services delivered by a collaborative arrangement, while outcomes are conditions that occur as a result of collaborative efforts (Thomas & Koontz, Citation2011). Careful separation of outputs (e.g. plans, products generated by collaboration) from outcomes generated by these outputs (e.g. improved environmental or socio-economic conditions) provides a more detailed account of mechanisms that link collaboration with its outputs and further outcomes.

The types of outputs generated by collaboratives vary depending on their goals (Mandarano, Citation2008). Accordingly, the evaluative criteria should be cautiously matched to the collaborative arrangement being studied (Conley & Moote, Citation2003). However, researchers face challenges when it comes to measuring specific qualities of outputs. The literature lacks clear criteria to evaluate quality (Mandarano, Citation2008) and suggests different output measures, such as the number of resolutions adopted due to collaboration (Koontz & Thomas, Citation2006), implementability of outputs (Ulibarri, Citation2015),the extent of support by stakeholders, political leaders and the public (Margerum, Citation2002) or accumulation of social capital such as trust, mutual understanding or social learning (Gerlak & Heikkila, Citation2011). Legitimacy can also be a criterion to assess whether the output is produced by authorized institutions in an inclusive and transparent process and addresses the concerns of citizens (Hartmann and Spit, Citation2020). Finally, Emerson and Nabatchi (Citation2015a) suggest to assess the outputs’ efficiency (reduced costs or gains attributable to the output’s implementation), efficacy (the extent to which outputs align with collective purpose) and equity (the extent to which outputs do justice to multiple interests and needs of beneficiaries). To this end, the diversity of integrated sectoral interests is a common criterion to assess collaborative outputs (Innes & Booher, Citation2010; Ulibarri, Citation2015).

The integrative nature of collaborative output is particularly relevant for spatial planning (Stead & Meijers, Citation2009) and Dutch flood risk management (Avoyan & Meijerink, Citation2021) as signs of moving in the direction of comprehensive integrated approaches are omnipresent (De Jong & Edelenbos, Citation2007). Both policy and legal frameworks for new flood safety standards in the Netherlands point out the necessity of collaboration between flood safety, spatial planning and/or other sectors in achieving the desired level of protection (Dutch National water plan 2016–2021). Where possible, the government facilitates integrated area development comprising a range of environmental and spatial functions. The criteria here align with the goal of studied case: in addition to synchronizing with flood safety goal of collaboration, the output should be integrative to the end it links and integrates flood safety with other socio-economic, spatial and environmental functions. Hence to operationalize the output, the difference between the sums of proposed and included in the PA additional functions is counted: smaller is the difference, higher is the level of integration of output.

The mechanism of producing collaborative outputs

A number of theoretical frameworks are developed to analyze and explain the functioning of collaborative governance (for an overview see: Bryson et al., Citation2015). Although the frameworks engage with different theories and, consequently, components to explore collaboration, they all acknowledge collaborative governance aims at producing joint outputs and outcomes. Most referred ones (e.g. Ansell & Gash, Citation2008; Bryson et al., Citation2006; Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015a; Newig et al., Citation2018; Thomson et al., Citation2007) indicate interdependent processes and mechanisms leading to desired results. Yet, they do not specify what constitutes the quality of collaborative outputs (rather than they are collaborative or consensus based) nor they illustrate how collaborative conditions in combination or alone feed this quality. Consequently, authors also propose different pathways of getting there – to successful outputs. For example, Ansell and Gash (Citation2008) suggest causal relationships between variables of collaborative processes for further empirical testing and theory elaboration. They argue that in effective collaborative processes, face-to-face dialogue is necessary (but not sufficient) for building trust and eventually developing ‘small wins’ (outputs). Alternatively, Provan and Kenis (Citation2008) suggest that effective collaboratives are determined by the number of participants, extent of goal consensus and trust, and presence of networking abilities. Finally, Emerson and Nabatchi (Citation2015b) argue that an iterative interaction of collaboration dynamics consisting of principled engagement, shared motivation and CJA is a causal mechanism heading to outputs and outcomes. The authors posit that the cyclical (clock-like) interaction of collaboration dynamics is a causal process triggered by a specific set of contextual conditions and linked with outputs and outcomes. This study makes a step further in not only testing whether the cyclical interaction of collaboration dynamics is a causal process, but also determining particular qualities of collaboration dynamics within the causal mechanism resulting in a specific output.

Operationalizing collaboration dynamics

To operationalize collaboration dynamics, Emerson, Nabatchi and Balogh’s Integrative framework for collaborative governance (2012) is used. The framework incorporates concepts from public administration, planning, conflict resolution and environmental management. Despite its comprehensiveness, it proved to be productively applicable to a number of empirical studies (e.g. Avoyan et al., Citation2017; Ulibarri, Citation2015). The framework is selected for two reasons. First, it advances previous analogous frameworks in its focus on articulating causal connections and asking for deeper attention to examining which causal relationships matter in which context and when (Bryson et al., Citation2015). Second, it privileges process over structure. Accordingly, it offers a specific range of process conditions to explore causality within collaborative processes in greater details. The focus of this study is at the core of collaborative processes, called collaboration dynamics, which are unpacked across three components: principled engagement, shared motivation and CJA (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b).

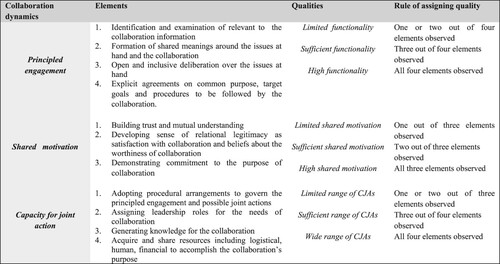

The principled engagement reveals behavioral interactions among collaborating participants. In theory, principled engagement enables participants of collaboration position themselves toward the others, build trust, internal legitimacy and commitment to the idea that brought them together (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015a). To assign quality to principled engagement, functional or procedural aspects of collaboration are favored in this study. The process of principled engagement that offers participants sufficient opportunities to identify, deliberate and make agreements over shared meanings and objectives of an issue at hand is considered to be highly functional. Next, shared motivation reveals the quality of interpersonal relations of collaborating parties (Emerson et al., Citation2012). Here, it is argued for high shared motivation to be formed and maintained participants make use of trust-building activities offered by collaboration, develop a sense of relational legitimacy and are uninterruptedly committed to the collaborative process. Finally, CJA indicates the range of available collaboration assets that are acquired or adopted by collaborating parties. In collaborative governance, effective internal governance arrangements are important in facilitating communication and deliberation among the parties (Thomson & Perry, Citation2006). These arrangements may be pre-determined beforehand. However, if the parties are able to enhance or generate new CJAs, then the collaboration evidently functions (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015a). summarizes the rules of assigning qualities to collaboration dynamics.

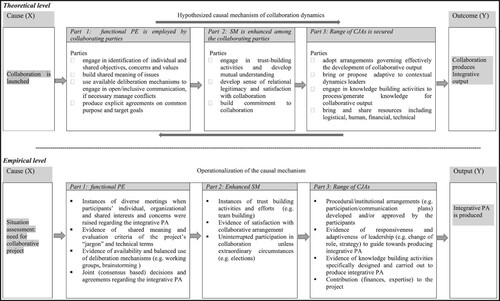

Building on the elements of collaboration dynamics suggested by Emerson et al. (Citation2012), the following causal mechanism is hypothesized accordingly (): by employing functional principled engagement, it is possible to enhance the shared motivation among collaboration parties and secure a range of capacities for development of integrative output. The next section details the methods used to test the hypothesized mechanism of collaboration dynamics.

Method

The theory-testing type of PT was used to test the hypothesized causal mechanism. Although PT in some form has been practiced for a long time, the method has only recently undergone serious scrutiny (Beach & Pedersen, Citation2018). PT is a within-case methodology of uncovering causal mechanisms. It enables a systematic study of the link between an outcome of interest and an explanation based on assessing and weighting evidence for and against causal inference and is therefore well adapted to addressing the sequencing of events and descriptive complexity of single case study (Beach & Pedersen, Citation2018). In PT, the ambition is not to identify values of specific variables and measure their co-variation but rather to understand the processes linking different relevant factors to the outcome (Hall, Citation2013). The theory-testing type of PT entails two major steps: theoretically unpacking a process and tracing it empirically by detailing the expected activities associated with each part of the mechanism (Beach & Pedersen, Citation2018). Respectively, the hypothesized causal mechanism () in this study is treated not as an intervening variable but a theoretical statement on how a set of variables or, more precisely, the processes associated with those variables cause a specific output (Hall, Citation2013). The theory is used prognostically by operationalizing theoretical formulations as empirical observations to be found if hypothesized variable was present/absent in a case study (Beach & Pedersen, Citation2018).

Case study selection

The dike of Grebbedijk has a length of 5.4 km and is located along the north bank of the Rhine River between Wageningen and Rhenen cities in the Netherlands. It protects a densely populated area against high water from the Lower Rhine. It is one of the most strategically important dikes in the country in terms of its impact on the hinterland. A dike breach may affect an extensive area with water levels reaching up to 3 m and causing more than €10 billion of economic damage (Wouter, Citation2004). Moreover, the extraction of clay from floodplains resulted in new riverine nature and wetlands, which are now key nature conservation areas under European Natura 2000 policies. Consequently, any intervention, including improvement of flood protection infrastructure, follows the logic of building within nature, that is integrating the new infrastructure into the environment. Since Grebbedijk does not meet the safety standards adopted in the Netherlands (Jorissen & Kraaij, Citation2016), it needs to be reinforced. For this reason, a project was initiated in 2016. Next to the goal of delivering flood safety, the project aims to establish ecological connections between the project areas falling under Natura2000 and Further Elaboration for the River Area programs. Furthermore, participating authorities together with the residents and interested parties set an intention of exploring synergies of Grebbedijk’s main goals with additional ambitions in the scope of nature, recreation, spatial quality and sustainability.

The case of Grebbedijk is appealing for studying collaboration as it differs substantially from similar large-scale infrastructure projects initiated by the DFPP. First, it entails broader cross-sectoral public policy orientation and involves a group of autonomous actors representing divergent sectoral interests and jurisdictions. Second, the scope of the Grebbedijk is much broader than that of similar projects. It is featured as an integrated approach showcase in Dutch national Delta Programme: an exemplar DFPP project investigating also various possibilities for sustainability (generation of energy on or near the dike, heat–cold storage and use of responsible materials and processes) (MIWM, Citation2020). Hence, the project provides a good chance to critically study supposedly successful collaboration with an ambition to deliver ‘more than just flood safety’, that is an integrative output. Finally from a theoretical stance, this single case study approach enabled a nuanced/in-depth analysis of a life cycle of collaborative arrangement as from the launch until its major output, PA, was adopted.

Data collection and analysis

The analysis is based on multiple data sources: semi-structured interviews, project documentation, participatory observations, as well as supplementary survey data. A real-time data collection was conducted, when the PA was still unknown. Between 2018 and 2019, 14 interviewsFootnote1 were conducted with project participants. To verify observations of change in collaboration dynamics, 3 additional interviews were conducted in 2020 with already interviewed participants. Fifteen responses to open questions concerning Grebbedijk from a survey being conducted in the framework of another study (Avoyan et al., Citationforthcoming) were also analyzed.

The chronology of key events leading to the PA was reconstructed. A timeline of three key stages within the exploratory phase was composed: developing six possible alternatives (start stage: begin. 2016 – begin. 2018), optimizing six possible alternatives into three promising alternatives (assessment stage: begin. 2018 – mid. 2019), and adopting the PA (final decision stage: mid. 2019 – mid. 2020). This timeline sequences events and processes also based on their theoretical relevance. It begins with the emergence of studied variables (collaboration dynamics) and concludes after the outcome of interest (PA) was adopted.

The data were structured and coded in Atlas.ti according to the variables of collaboration dynamics and the PA. For PT, the empirical evidence was collected for each part (structured with sub-elements) of causal mechanism (). The reasoning is elaborated while presenting the results by means of active citation (Moravcsik, Citation2010) of the sources of evidence upon which the confidence in the presence of the part of hypothesized causal mechanism was based. To assess whether the parts of collaborative process took place as hypothesized and to assign qualities to collaboration dynamics at a given stage, the rules outlined in were used.

Results

Collaboration’s output: level of integration as quality of PA

The requirement for Grebbedijk process to yield integrative solutions was clearly articulated by participants from the outset (MIWM, Citation2020). In 2016, the Vallei en Veluwe water authority (VVWA) established a partnership with the provinces of Gelderland and Utrecht, the municipality of Wageningen, Rijkswaterstaat (Directorate-General for Public Works and Water Management: RWS) and Staatsbosbeheer (Dutch government organization for forestry and management of nature reserves: SBB) to examine whether the reinforcement of Grebbedijk, in addition to delivering flood safety, offers also opportunities for incorporating spatial and environmental ambitions into the development of dike and adjacent area. Groups of stakeholders (residents, private companies, farmers, nature organizations and water sports associations) also joined the project under Dijkdenkers (dike thinkers in English) collaborative platform. Authority representatives formed a steering committee and delegated their officials to engage in the project (within the process team: a liaison arrangement to connect authorities with project’s team and stakeholders). These authorities have different interests and ambitions in the floodplains along Grebbedijk in the context of Further Elaboration of the Area Around the River program, Water Framework Directive, Natura2000 and forthcoming national Environment and Planning Act. In addition, a number of stakeholder groups have interests in nature conservation and development coupled with economic, recreational or housing opportunities in the floodplains (VVWA, Citation2019). These interests are centered around the following themes: spatial quality, nature development, sustainability, recreational opportunities and cultural heritage. With adopted PA, Grebbedijk met the project goal of assuring water safety and additionally incorporating 15 of 20 additional ambitions suggested by the parties. Data from interviews, surveys and documents indicate the integrative nature of PA. It represents a successful example of collaborative output with high level of integration considering the following: the content fits with project’s goal, the difference between those proposed and included in the PA additional ambitions is small and collaborating parties perceive it as being integrative. The next section elaborates on when and how collaboration dynamics contributed to this success.

Collaboration dynamics

Start stage: integration of interests and concerns

Part 1: principled engagement

Grebbedijk was approved by DFPP as an area development integral project. A variety of meetings was prearranged to serve this purpose (VVWA, Citation2017). At least 10 types of gatherings for participants to raise their individual/organizational and shared interests were counted (e.g. info-evenings, design workshops, thematic building block sessions, integral working sessions). The project’s first information meeting explicitly clarified the commitment to collectively develop the PA (VVWA, Citation2017) and make an inventory of stakeholders’ interests and concerns via building block sessions on safety, nature, infrastructure and economy, recreation and landscape and sustainability. These sessions enabled identification of shared interests and formation of corresponding groups. Furthermore, the meetings stimulated dialog on clarification of concepts of common interest: integrality, ambition, sustainability, circularity, area development etc. (Lohr & Ebbens, Citation2019). Various deliberation stimulating techniques were employed by the project team, including brainstorming or mood boardsFootnote2 for exploring and discussing participants’ preferences.

Most of the deliberation took place between water sports/recreational and environmental organizations around the possible relocation of a harbor installation with consequences for nature conservation and recreational opportunities. As a result, some stakeholders were disappointed due to domination of one major line of discussion. Alternatively, the engagement between the authorities was more formal and structured resulting in a number of important decisions. The collaboration agreement outlining authorities’ ambitions and their commitment to deliver an integrated PA is one of them. It also specified the leading task of flood risk management and ambitions concerning improvement of spatial quality or environmental conditions to self-organization of authorities with consequent financial contributions.

Overall, the principled engagement at this stage is assessed with high functionality as all four elements were observed. The diversity of meeting types was serving the purpose of engaging parties in developing shared meanings of integrative output. Although provided deliberation mechanisms were not used equally, their availability appears to be essential in the absence of conflict resolution strategies. Finally, the presence of intermediate agreements on joint development of PA highlights the consensus on generating integrative output. Although these agreements do not provide a detailed road-map on implementation (interview), for the measures of functionality, their presence suffices.

Part 2: Shared motivation

Face-to-face interactions were crucial at this stage as most of participants did not know each other in person. The project team organized a number of trust-building activities for all parties involved (information evenings, joint excursions). However, engaging in trust-building activities does not always yield the desired level of trust (Vangen & Huxham, Citation2003). As mentioned by an interviewer – ‘most of parties choose to hold back, keep their cards and wait for others to make the steps’. When asked what factors contributed to this atmosphere, long-standing organizational competitiveness and conflicts between the Gelderland province, the municipality of Wageningen or VVWA (e.g. ongoing tension over road construction in the city) were mentioned. Competitiveness arises also over the ownership of collaborative effort when two public authorities, the province and water authority, struggle to share a leading role in the project. Such tensions affect organizational and personal relationships in collaborative arrangements (interview).

Despite some distrust between authorities, the project team managed to achieve a sufficient level of internal legitimacy by means of involving also the stakeholders. Providing opportunities for feedback was an important mechanism to ensure project’s internal transparency (VVWA, Citation2019). A ‘guide for response’ with clear instructions on how to write a feedback/comment or placing a deadline to show a reaction is expected are among the collected evidences indicating internal legitimacy. However, as the documents were technical, the feedback opportunity was not always used by stakeholders. This arrangement did little to affect the content of PA’s versions but increased the internal legitimacy. Similarly, a number of individual and kitchen table meetings improved interpersonal relationships and attitudes toward the project (Lohr & Ebbens, Citation2019). The parties were informed that every single idea/ambition proposed would be evaluated for efficiency and feasibility. The dilemma, however, was in raising high expectations. If the expectations cannot be realized, it will result in disappointment, loss of confidence, trust and support for the project (interview). Overall, the shared motivation at this stage was rather formed than enhanced. The presence of trust-building activities indicates some effort was spurred for creating trustful environment and fostering interpersonal relationships between the participants. The analysis shows that once the desired, that is sufficient, extent of shared motivation was formed, it was maintained throughout the process as an important asset of the project.

Part 3: Capacity for joint action

A range of CJAs was adopted at this stage by project participants. As it is with governmentally mandated DFPP projects, most of the procedural arrangements were designed for producing a joint output. Although the implementation logic of Grebbedijk was pre-determined, the project team had the flexibility to develop a detailed Action Plan outlining the scope of project membership, objectives and responsibilities of those involved, communication and participation strategies, description of the steps within the exploration phase, including decision-making procedures (VVWA, Citation2017). It was developed in consultation with and approved by authorities. The document is an important evidence indicating the parties succeeded in developing and approving a new CJA. The leadership provided by project manager was instrumental for this intermediate output to come about. The VVWA anticipating complexity of interests, strategically recruited a professional experienced in spatial and environmental planning as opposed to many DFPP projects led by civil engineers. His skillset of connecting parties, mediating conflicts and steering the process towards integrative output was decisive (interview). Furthermore, he was responsive to adapt to contextual dynamics of the project. It was his recommendation to pass on one of his responsibilities and appoint an independent chair for Dijkdenkers in order to avoid conflict of interests.

Knowledge as an element of CJA was central in Grebbedijk: generating knowledge on best solution for the dike was essentially the objective of the phase. If the synthesis of domain-specific knowledge started within thematic sessions, the integration thereof continued in the follow-up integral design sessions. During these sessions, ‘research-based design’ methodology (van den Boomen et al., Citation2017) was used. People with diverse backgrounds and interests come together with ‘studio designer’ to work for example on area planning tasks. The aim is to confront different perspectives and find linking points and solutions supported by majority (van den Boomen et al., Citation2017). These sessions were creative and unique avenues to connect also with authorities. However, some raised also concerns about sessions’ facilitators for their biased preferences of specific solutions for the dike and its surroundings (interview).

Finally, the capacity for producing an integrative PA was supported by resources authorities and stakeholders brought to the project. Along with financial contributions, the time and expertise of people involved in the project are also considered as resource. The contributions varied per party. For example, VVWA as project initiator, supplied necessary staff and finances (e.g. for hiring consultants), while RWS provided the project office and DFPP subsidized the organizational constituencies (e.g. communication campaign) of the exploration phase. Other parties contributed by delegating civil servants to work within the project’s process team. At the same time, stakeholders of Dijkdenkers representing different organizations, contributed with steady membership. At least seven instances were identified demonstrating willingness of the parties to contribute resources for integrative PA. For example, it was decided that the project team (mostly representatives of VVWA) follows a capacity building training with the process team (representatives of all formal collaborating parties) indicating the willingness of parties to invest time and resources in joint capacity building activities.

Assessment stage: narrowing possible solutions

Part 1: Principled (re)engagement: observed changes

The meetings’ frequency and diversity were maintained providing sufficient opportunities for parties to re-define and advance their objectives. Additionally, two important changes were introduced: intensified individual consultations both with stakeholders and authorities and introduction of ‘walk-in moments’. These consultations clarified study results of different ambitions and accelerated feedback exchange between the parties (interview). The ‘walk-in moments’ for residents ensured the project progress is communicated with those not involved in Dijkdenkers platform (VVWA, Citation2019). Although these changes required time and energy, the benefits prevailed: parties were able to move fast and make procedural decisions. The discussions were now informed by the results of in-depth studies (e.g. technical innovations, habitat analysis) conducted by external experts. Although there were opportunities to deliberate the studies and possible alternatives, experts’ presentations on how and why certain choices were made prevailed. Moreover, some of the managers of DFPP were concerned much attention was paid to area ambitions and less to the dike (technical) reinforcement itself (interview). This piece of evidence illustrates the core of the collaborative process was to produce integrative solution for dike reinforcement seen also the decisions made: three promising alternatives (substantial) and common assessment framework (procedural).

Part 2: Continuation of shared motivation

During this period, municipal and provincial elections took place in the Netherlands. With new representatives of authorities entering the process, there was a shift in overall collaboration dynamics. The project team (having staff changes itself) had to build new relationships with new members while they had to get familiar with the project. ‘Even though investments in trust-building activities are made initially, it can be simply lost by new people and personalities entering the process’ (interview). It is crucial to maintain and transfer joint commitments and confidence in collaboration when membership and staff changes happen (Vangen & Huxham, Citation2003). Project team dedicated much time to personal consultations to moderate possible impact of changes in the membership of collaboration. The decreased frequency of trust-building activities (e.g. cycling or sailing) was compensated with intensified personal communication to maintain earlier agreements and to ensure expectations from those agreements are followed by new members of collaboration.

Part 3: Additions to CJA

As the collaboration evolved, so did CJAs. First, the communication and participation plans were revised to better outline participants’ engagement procedures. Second, when it became clear Dijkdenkers do not form a ‘homogeneous group’, it was decided to replace the project manager and propose an independent chairman for mediating interests within Dijkdenkers. Third, a new knowledge was generated for PA. For Environmental Impact Assessment, specific frameworks for feasibility studies were developed (also presented to stakeholders for comments/opinions). The studies of proposed ambitions conducted mostly by externally hired experts ensured all ambitions were thoroughly assessed for their fitness to PA. Although the discussions were tense as the stakes became more clear, having knowledge grounded content for deliberation and the new leadership role of Dijkdenker’s chair, project team managed to avoid serious conflicts. Moreover, parties having the assessment criteria re-defined and agreed, justification of certain choices made was not as difficult as if these would be just announced. For example, the secondary channel for water recreation was not going to be further tested as a result of not passing the agreed environmental criteria, while another channel with shared use for water sports was going to be further explored.

Decision stage: approving PA

Part 1: decline in principled (re)engagement

Longitudinal studies of collaboration indicate a declining trend in participation (stakeholders tend to leave the process over time) along with engagement fatigue (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2016; Scott et al., Citation2020). Nearing the end of exploration phase, both intensity and diversity of group meetings declined. Six of 12 types of meetings were maintained with decreased frequency. Individual consultations intensified during the assessment stage were now conducted with the authorities only. The main purpose of these consultations was to ‘fine tune’ the details (e.g. financial) of PA. Consequently, deliberation mechanisms employed in the previous stages were largely not necessary. Nevertheless, the analysis indicates principled engagement declined but not its functionality. The efforts of previous stages paid off and the draft PA was approved at last. Moreover, the declined intensity of the process suggests that the draft PA was not overly contested while offered mechanisms of engagement and deliberation could be still used.

Part 2: Continuation of shared motivation

Despite the decline in engagement and group interactions, parties maintained a sufficient level of mutual trust, internal legitimacy and commitment to the process. This is mostly explained by the widespread understanding that the likelihood of honoring many of area ambitions was relatively high (interview). Furthermore, shared motivation takes time to build, and once attained, may play a less central role in collaborative process (Ulibarri et al., Citation2020). Nearing the end, there were no specific trust-building activities organized leaving more room for personal consultations between the project team and authorities. Furthermore, the finalization of Grebbedijk’s exploration phase coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic. Many joint activities (presentations, excursions, etc.) were canceled or moved to online platforms. Despite such extraordinary circumstances, parties were generally committed, and only a few stakeholders quit the process. Finally, during the decision stage, no conflicts were observed. Parties were overall satisfied with the collaboration. This is proved by adopted PA with no delays.

Part 3: Capacity for joint action

A well institutionalized and effectively employed procedural arrangement of collecting and processing comments on important joint determination was traced also at the decision stage. Thirty comments/opinions on the draft PA were collected in response note containing also detailed responses to the comments (VVWA, Citation2020). Some minor changes were made to PA based on this. Yet interestingly, PA was largely considered final (rather than draft) with the possibility of minor modifications only. Instead, much energy was placed in the transition of leadership from one project manager to the other, indicating the capacity of collaboration to adapt to contextual dynamics of the project. It is common in the Netherlands, to employ managers with certain qualifications depending on the project’s phase (e.g. planner for exploration phase, and engineer for plan elaboration phase). Eventually, the new project manager assembled collaborative efforts of the exploration phase and brought the project to the planning phase.

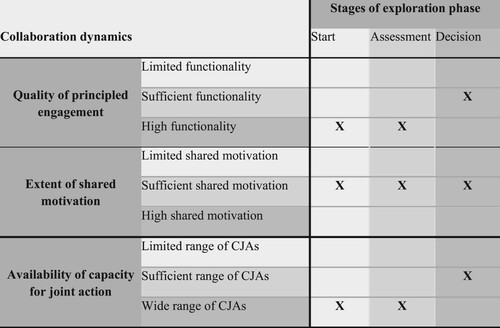

Overall, the functionality of principled engagement declined according to procedural characteristics of the stage as did continues updates of CJAs. Yet the adoption of PA without delays and major obstacles indicates right steering of collaboration dynamics from the outset paid off at last. To this end, visualizes the assessment of collaboration dynamics in Grebbedijk. Finally to summarize, the hypothesized mechanismFootnote3 of collaboration dynamics is adjusted for Grebbedijk: by employing a set of pre-determined capacities for joint action, collaborating parties engaged in cycles of highly functional principled engagement, built and maintained sufficient shared motivation and secured a wide range of capacities for joint action to develop and adopt an integrative output.

Discussion and conclusions

Much is known in the literature about collaborative governance and the benefits it delivers for environmental management. Yet the black box of causal mechanisms linking processes with produced outputs of collaborative governance is underexamined. How and why does collaboration lead to specific outputs? What are the ingredients of the black box of causal mechanisms linking the cause with the output? How do these ingredients change, adapt or transform? This longitudinal study illustrates that the integrative output in Grebbedijk cannot be explained through general insights about conditions for success (e.g. presence of strong incentives to collaborate or strong leadership: Douglas et al. (Citation2020)) discussed in the literature. It shows the importance of exploring linkages between behavioral interactions, interpersonal relationships and functional assets available to collaboration in understanding what is/will be produced by collaboration. The success of this and similar collaborative arrangements should rather be demonstrated through a longitudinal evaluation of causal relationships between particular conditions of collaborative governance residing in one or more causal mechanisms. This study used a theory-testing PT method to explore one of many possible mechanisms, the causal mechanism of collaboration dynamics, to understand whether the mechanism was present as hypothesized and could explain the occurrence of integrative output. Although proving causality in social sciences is challenging (Beach & Pedersen, Citation2018), using a PT method allows us to illustrate to the very least a probable causality. This is what this study attempted to do.

Hypothetically, the cause of mechanism was the situation assessment (dike safety assessment) and the launch of Grebbedijk. Based on this assessment, VVWA concluded a collaborative approach is needed for the project. Usually, self-initiated collaborative arrangements (e.g. community-based collaborations) convene willingly collaborating parties to design the way they want to collaborate (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015a). In Grebbedijk, VVWA launched the process while having a specific set of pre-determined capacities for joint action: procedural arrangements, financial and human resources, general ground rules of organizing collaborative projects. Therefore, the first step in the mechanism was the formation of project team and accumulation of capacities for joint action. The procedural arrangements (e.g. project staging) designed to come to an integrative solution, necessary leadership roles, knowledge and resources were brought to the project by VVWA before the actual start of collaboration. On this ground, this study confirms a proposition from the literature stating initiating leadership is essential for formation of collaboration (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015a), and argues that by carefully selecting necessary CJA ingredients, initiating leadership may strategically outline the contours of collaboration dynamics for desired outputs.

Following the first part of pre-determined CJAs, initially hypothesized causal mechanism of collaboration dynamics is empirically validated as it shows the relationship and interdependence between collaboration dynamics. Yet, within Grebbedijk, collaboration dynamics were not static and showed fluctuation over time. Specifically, principled engagement was highly function during the start and assessment stages having declined at the decision stage. Similarly, a range of CJAs was acquired at the start and assessment stages declining toward decision stage. At the same time, shared motivation was quite stable: once formed it was maintained throughout the process. There was no intention to invest in and further advance shared motivation among participants. This was evident during the assessment stage when the number of trust-building activities declined yet overall level of shared motivation sustained until the decision stage. Hence, it is argued enhancing shared motivation is neither sufficient nor necessary to generate an integrative PA, while highly functional principled engagement and availability of wide range of CJAs appear important.

The first conclusion of this study is that the dynamic interaction of principled engagement, shared motivation and CJA is a causal process linked to outputs. This study validates the hypothesized mechanism, while offering the following implications. First, in the working of the mechanism pre-determined CJAs were crucial for the mechanism to unfold successfully. Second, the causal processes of collaboration dynamics and the extent they contribute to desired output are subject to adaptation and change depending on the purpose of specific process phase. Also, effects of different parts of the mechanism become weaker towards the decision stage as seen in . Hence, this study validates previous scholarly assumptions that collaborations usually decline in participation and engagement over time (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2016; Ulibarri et al., Citation2020). Third, for the causal mechanism to work, all parts must be maintained over some period of time to remain valuable for enhancing the qualities of outputs. Finally, this study suggests that in order to move on towards desired output, enhancing shared motivation might not be necessary and that sufficient level of shared motivation compensated by highly functional principled engagement and wide range of CJAs may by sufficient. Collaborating parties may spend considerable time and resources on improving relationships and enhancing trust, but this does not necessarily prompt better performance.

The second conclusion is that for externally directed collaborations (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015a), a carefully assigned set of CJAs, particularly leadership, are decisive for the functioning of collaboration dynamics. Key is how these pre-set arrangements are further improved and changed to adapt to contextual developments. In Greddbijk, the role project manager was critical in steering the dynamics of collaboration. Managing collaborative projects as such challenges project managers to find necessary management strategies that fit to collaboration’s context and unexpected developments. After all, with multitude of actors involved, not all ideas and goals can be realized. However, leaders holding connective capacities, such as ability to embrace complexity and adapt to developments in the project context (Edelenbos et al., Citation2013) are able to connect and mobilize actors, manage conflicts and sustain sufficient shared motivation throughout the process. Moreover, well-organized processes of functional principled engagement facilitated by leaders may compensate for the lack of or reduced state of shared motivation. The critical task then is to sense the tipping point when accumulated shared motivation and trust is sufficient to generate common goods.

Studying a single case of collaborative governance comes with a number of limitations. First, a single case cannot provide definitive answers as to why collaborations succeed or fail: whether the mechanism of collaboration dynamics will evidently yield desired results. There may be many pathways to success (e.g. funding mechanism for realizing additional to flood safety ambitions) and many situations when the causal mechanism may cease (conflicts, newly acquired knowledge, unimplementability of joint actions). Therefore, this type of research cannot offer generalizable knowledge about successful local collaborative. What it does do is provide a detailed and contextualized understanding of how local stakeholders and public authorities attempt and succeed to integrate their interests in Dutch flood risk management projects and how this integration can be explained. Hence, results of similar projects in other countries may vary depending on socio-economic and cultural characteristics of the regions, and comparative studies could be useful here. Second, this study explores only actual collaborative processes in the quest of finding a key to success. However, these processes do not take place in isolation as they are embedded within external conditions (e.g. power relations and political dynamics, socio-economic and cultural characteristics) framing possibilities and constraints for collaboration. Understanding the role of external conditions in shaping practices and consequently outputs of collaborative arrangements would provide a more comprehensive view of causes and effects of collaboration over time.

Despite these limitations, this study generates useful insights contributing to the discussion on causal conditions of collaboration dynamics leading to integrative outputs in the context of environmental governance. It also illustrates the usefulness of PT method for investigating collaborative governance over time. The measurements developed for this study could be of use for researchers. They could take on from here further research on understanding causation in collaborative governance, for example, not only through PT but also qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) or combination of thereof to learn more about different pathways to success. This study sought to explore only one quality of collaborative output: level of integration. Researchers might be interested to study other qualities of collaborative outputs, specifically whether they support innovation or advance legitimacy. Finally, the measurements developed for this study could be used by practitioners for intermediate evaluations of different public collaborative arrangements. When the changes in configuration of collaborative processes are still possible, gaining knowledge on why and how collaboration dynamics function allows practitioners to make necessary interventions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.7 KB)Acknowledgements

I thank the team of Grebbedijk and all my interviewees for their participation in this research. I also thank professors Kirk Emerson and Sander Meijerink for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest is reported by the author(s)

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emma Avoyan

Emma Avoyan was a PhD researcher at Nijmegen School of Management at Radboud University when writing this article. Her research interests broadly concern collaborative forms of environmental policy-making and innovative methods of impact assessment.

Notes

1 See supplementary materials for the interview guide.

2 Type of visual presentation of images, texts and objects in a composition.

3 For detailed deconstruction, see supplementary materials.

References

- Agranoff, R. (2008). Collaboration for knowledge: Learning from public management networks. In R. O’Leary & L. B. Bingham (Eds.), Big ideas in collaborative public management. NYM.E. Sharpe (pp. 162–194).

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Avoyan, E., Lagendijk, A., Meijerink, S., & Kaufman, M. (forthcoming). Output performance of collaborative governance: Examining necessary and sufficient conditions for achieving output performance of the Dutch flood protection program.

- Avoyan, E., & Meijerink, S. (2021). Cross-sector collaboration within Dutch flood risk governance: Historical analysis of external triggers. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 37(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2019.1707070

- Avoyan, E., Tatenhove, J. V., & Toonen, H. (2017). The Performance of the black sea commission as a collaborative governance regime. Marine Policy, 81, 285–292. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.04.006

- Beach, D., & Pedersen, R. (2018). Process-Tracing methods. University of Michigan Press.

- Biddle, J. C. (2017). Improving the effectiveness of collaborative governance regimes: Lessons from watershed partnerships. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management, 143(9). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0000802

- Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Stone, M. M. (2006). The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public Administration Review, 66(Suppl. 1), 44–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00665.x

- Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Stone, M. M. (2015). Designing and implementing cross-sector collaborations: Needed and challenging. Public Administration Review, 75(5), 647–663. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12432

- Conley, A., & Moote, M. A. (2003). Evaluating collaborative natural resource management. Society and Natural Resources, 16(5), 371–386. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920309181

- De Jong, M., & Edelenbos, J. (2007). An insider’s look into policy transfer in transnational expert networks. European Planning Studies, 15(5), 687–706. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310701213996

- Douglas, S., Berthod, O., Groenleer, M., & Nederhand, J. (2020). Pathways to collaborative performance: Examining the different combinations of conditions under which collaborations are successful. Policy and Society, 39(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1769275

- Edelenbos, J., van Buuren, A., & Klijn, E. H. (2013). Connective capacities of network managers: A comparative study of management styles in eight regional governance networks. Public Management Review, 15(1), 131–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.691009

- Emerson, K., Gerlak, A. K., Barreteau, O., & ten Brink, M. B. (2009). A framework to assess collaborative governance: A New Look at four water resource management cases. Human dimensions of global environmental change conference Amsterdam.

- Emerson, K., & Nabatchi, T. (2015a). Collaborative governance regimes. Georgetown University Press.

- Emerson, K., & Nabatchi, T. (2015b). Evaluating the productivity of collaborative governance regimes: A Performance matrix. Public Performance and Management Review, 38(4), 717–747. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1031016

- Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., & Balogh, S. (2012). An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur011

- Gerlak, A. K., & Heikkila, T. (2011). Building a theory of learning in collaboratives: Evidence from the everglades restoration program. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(4), 619–644. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq089

- Hall, P. A. (2013). Tracing the progress of process tracing. European Political Science, 12, 20–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2012.6

- Hartmann, T., & Spit, T. (2016). Legitimizing differentiated flood protection levels - Consequences of the European flood risk management plan. Environmental Science and Policy, 55, 361–367.

- Heikkila, T., & Gerlak, A. K. (2016). Investigating collaborative processes over time: A 10-year study of the south Florida ecosystem restoration task force. The American Review of Public Administration, 46(2), 180–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074014544196

- Imperial, M. T., Johnston, E., Pruett-Jones, M., Leong, K., & Thomsen, J. (2016). Sustaining the useful life of network governance: Life cycles and developmental challenges. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(3), 135–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1249

- Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (2010). Planning with complexity: An introduction to collaborative rationality for public policy. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jorissen, R., & Kraaij, E. (2016). Dutch flood protection policy and measures based on risk assessment. E3S Web of Conferences, EDP Sciences, Vol. 7, p. 20016.

- Koontz, T. M., & Thomas, C. W. (2006). What do we know and need to know about the environmental outcomes of collaborative management? Public Administration Review, 66(Suppl. 1), 111–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00671.x

- Leach, W. D., & Sabatier, P. A. (2005). To trust an adversary: Integrating rational and psychological models of collaborative policymaking. The American Political Science Review, 99(4), 491–503. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305540505183X

- Lohr, R., & Ebbens, E. (2019). Omgevingsparticipatie verkenningsfase Gebiedsontwikkeling Grebbedijk: Van start Tot besluitvorming. LievenseCSO Milieu B.V. (in Dutch).

- Mandarano, L. A. (2008). Evaluating collaborative environmental planning outputs and outcomes. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 27(4), 456–468. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X08315888

- Mandell, M., & Keast, R. (2007). Evaluating network arrangements: Toward revised performance measures. Public Performance & Management Review, 30(4), 574–597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576300406

- Margerum, R. D. (2002). Evaluating collaborative planning: Implications from an empirical analysis of growth management. Journal of the American Planning Association, 68(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360208976264

- McGuire, M. (2006). Collaborative public management: Assessing what we know and how we know it. Public Administration Review, 66(Suppl. 1), 33–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00664.x

- MIWM. (2020). Meerjarenprogramma Infrastructuur, Ruimte En Transport. (in Dutch).

- Moravcsik, A. (2010). Active citation: A precondition for replicable qualitative research. In PS - Political Science and politics. (Vol. 43, pp. 29–35). Cambridge University Press.

- Newig, J., Challies, E. D., Jager, N. W., Kochskaemper, E., & Adzersen, A. (2018). The environmental performance of participatory and collaborative governance: A framework of causal mechanisms. Policy Studies Journal, 46(2), 269–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12209

- Nooteboom, B. (2001). Learning and innovation in organizations and economies. Oxford University Press.

- Provan, K. G., & Kenis, P. (2008). Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(2), 229–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum015

- Scott, T. A., Ulibarri, N., & Scott, R. P. (2020). Stakeholder involvement in collaborative regulatory processes: Using automated coding to track attendance and actions. Regulation and Governance, 14(2), 219–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12199

- Silvia, C. (2018). Evaluating collaboration: The solution to one problem often causes another. Public Administration Review, 78(3), 472–478. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12888

- Stead, D., & Meijers, E. (2009). Spatial planning and policy integration: Concepts, facilitators and inhibitors. Planning Theory and Practice, 10(3), 317–332. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350903229752

- Thomas, C. W., & Koontz, T. M. (2011). Research designs for evaluating the impact of community-based management on natural resource conservation. Journal of Natural Resources Policy Research, 3(2), 97–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19390459.2011.557877

- Thomson, A. M., & Perry, J. L. (2006). Collaboration processes: Inside the black box. Public Administration Review, 66(SUPPL. 1), 20–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00663.x

- Thomson, A. M., Perry, J. L., & Miller, T. K. (2007). Conceptualizing and measuring collaboration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 19(1), 23–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum036

- Ulibarri, N. (2015). Collaboration in federal hydropower licensing: Impacts on process, outputs, and outcomes. Public Performance and Management Review, 38(4), 578–606. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1031004

- Ulibarri, N., Emerson, K., Imperial, M. T., Jager, N. W., Newig, J., & Weber, E. (2020). How does collaborative governance evolve? Insights from a medium-n case comparison. Policy and Society, 39(4), 617–637. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1769288

- van den Boomen, T., Frijters, E., van Assen, S., & Broekman, M. (2017). Stedelijke Vraagstukken, Veerkrachtige Oplossingen - Ontwerpend Onderzoek Voor de Toekomst van Stedelijke Regios.TRANCITY*VALIZ.

- Vangen, S., & Huxham, C. (2003). Nurturing collaborative relations: Building trust in interorganizational collaboration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886303039001001

- VVWA. (2017). Plan of Approach: Dike Reinforcement of Grebbedijk Exploration Phase.

- VVWA. (2019). Grebbedijk Communicatieplan (in Dutch).

- VVWA. (2020). Nota Voorkeursalternatief Gebiedsontwikkeling Grebbedijk (in Dutch).

- Wouter, K. (2004). Nut En Noodzaak van de Slaperdijk Als Regionale Waterkerin.