ABSTRACT

Local governments are at the heart of implementing increasingly ambitious national plans for wind energy. While support by local governments for these plans has been studied extensively, only few studies have looked into local governments’ contestation of wind energy development. In this paper we analyze contentious governance processes in which local governments join efforts with citizen action groups to oppose projects proposed by developers or the national government. We focus on the strategic dilemmas that local governments face while engaging in contentious governance. Uncovering strategic dilemmas helps to see contestation by local governments as part of a web of governance relationships, thus moving beyond dichotomous understandings of the players involved in wind farm conflicts. Strategic dilemmas also allow understanding of how stances of local governments and their citizen allies change over time, and how strategic and tactical considerations emerge from interaction patterns.

Introduction

In the wake of the European Green Deal, several national governments are developing more ambitious plans on wind energy. Local governments are at the heart of implementing such plans in concrete projects. They find themselves in hierarchical multi-level governance relationships with national governments in which they have to serve the national interest, while at the same time representing and safeguarding local interests (Pierre & Peters, Citation2020). When these interests do not coincide, local governments need to navigate between supporting or contesting these plans (Breukers & Wolsink, Citation2007; Rand & Hoen, Citation2017; Wüstenhagen et al., Citation2007). While much attention has been paid to support by local governments, only few studies have looked into their contestation of wind energy development (Toke, Citation2005; Wolsink, Citation1996). Recent cases from the Netherlands indicate that local governments sometimes join forces with citizen action groups in their contestation of projects proposed by developers, regional governments or the national government. Current literature refers to these dynamics as processes of ‘contentious governance’, which have also been observed in other policy instances such as bans on fracking, opposition to the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), or sanctuary cities that protect undocumented migrants (Metze, Citation2018; Verhoeven, Citation2020; Verhoeven & Duyvendak, Citation2017).

In this paper we aim to better understand how local governments engage in contestation of wind energy development by exploring two processes of contentious governance in the Netherlands. As part of the ambition of the Dutch national government to achieve a 49% CO2-emission reduction in 2030, it has set the target to produce 49 TWh of offshore wind energy and 35 TWh of renewable electricity production via onshore solar and wind farms (Klimaat, Citation2019, p. 158). Meanwhile, 12.5% of Dutch municipalities oppose onshore wind and 67% has no wind energy ambitions (BMC, Citation2018). The potential for contentious governance against onshore wind farms is thus pretty large, while nearshore projects that interfere with local interests are also likely to stir resistance.

Our analysis of contentious governance related to Dutch wind farm projects will focus on the strategic dilemmas (Jasper, Citation2006) that local governments face when engaging in strategic interactions with citizen action groups to contest wind farms planned by developers or higher tiers of government. With this focus on strategic dilemmas, we aim to analyse local governments’ contestation of wind farms as part of a web of governance relations with allies and opponents. These strategic dilemmas are important to study because they help to understand how local governments struggle with the contestation of wind farms within such complex governance relations. In addition, our strategic perspective on the web of players involved in contentious governance helps to move beyond supporter-objector, government-citizen or developer-public dichotomies. Even though calls to move beyond such dichotomies have been made before (Cuppen & Pesch, Citation2021; Wüstenhagen et al., Citation2007); their use is rather persistent (see Janhunen et al., Citation2018; Rand & Hoen, Citation2017). In developing a more complex and nuanced perspective, our analysis of local governments’ strategic dilemmas will be guided by the following question: which strategic dilemmas do local governments face when interacting with citizen action groups to resist wind farms planned by developers or higher tiers of government?

Our empirical analysis draws on two cases of highly contested wind farms in the Netherlands: (1) a planned 1400 MW nearshore wind farm close to the coastal municipalities of Katwijk, Noordwijk and Zandvoort, and (2) the onshore wind farm N33 in the province of Groningen. Although these cases are situated in a specific Dutch context, we expect that our empirical analysis provides insights for other countries where local governments have to balance national and local interests related to wind farm development under pressure of national climate policies. In the next section we will elaborate on the concepts of contentious governance and strategic interactions. The selection of cases and methods will be explained in section 3. After presenting our findings in sections 4 and 5, we end with a discussion and conclusions in section 6.

Contentious governance and strategic interactions

Contentious governance

Contentious governance is a helpful concept to guide the empirical analysis of local contestation of wind farms beyond local-national government or government-citizen dichotomies. In addition, contentious governance goes beyond multi-level governance interactions, by considering the dynamics between local governments and non-governmental players (e.g. local action groups) acting in joint opposition. This leads to a richer, layered and more complex understanding of the governance processes involved in the contestation of wind farms. To further unpack contentious governance, we first need to explore its constitutive notions of contention and governance, which come from rather disconnected literatures.

The notion of contention builds on the suggestion in contentious politics literature to see government no longer exclusively as the target of claims by social movements, but also as initiators of claims that aspire to alter or redress a problematic situation (Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2015). Besides common claims to seek legitimacy for policies (Hilgartner & Bosk, Citation1988), governments also make ‘strident demands’ or ‘direct attacks’ to contest the legitimacy of policy claims put forward by others (Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2015, p. 8). In essence, we can see such contestation of policy claims as players focusing on their own interests, needs and values, and on imposing their preferred solutions on others at their expense (Rubin et al., Citation1994; compare Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2015). Governmental players defend their policy position and if this position is threatened by policy claims from other governmental players, they will react with a counterclaim, which can be followed by a reaction, setting off a policy conflict escalation process (Weible & Heikkila, Citation2017).

Governance is implicated in these conflictual processes in two ways. First, governance refers to the multi-level character of governing practices amongst governmental players from different tiers of government within national states. Traditionally, hierarchy and top-down policy making with local governments as implementers at the bottom of the system characterized such governing practices. More recently, local governments have become less submissive and waiting for cues by the national level, as a result of rescaling processes which have increased their autonomy and economic self-reliance in many Western-European countries (Pierre & Peters, Citation2020). Against this background, policy proposals by national governments can be perceived as hierarchical interventions that can trigger contestation by local governments when they threaten local policy positions. Second, governance refers to how governmental and non-governmental players interact with each other. These interactions are mostly studied in terms of collaborative governance processes aiming for consensus and deliberation (Ansell & Gash, Citation2008), while largely overlooking the possibility of governmental and non-governmental players working together in the contestation of unwanted policies (for theoretical exceptions, see Griggs et al., Citation2014; Metze, Citation2010). The joint efforts are most likely based on a shared sense of threat, with governmental players perceiving a wind farm proposal as a threat to their policy position and non-governmental players perceiving it as a threat to local communities.

Combining the notions of contention and governance opens up a conceptual space for the agency of local governments contesting policies by higher tiers of government in joint efforts with citizen action groups, NGOs or social movement organizations. Hence, the notion of contentious governance can be defined as ‘governmental and non-governmental players collaborating in the contestation of policy-making or implementation initiated by other governmental players or their business partners’ (Verhoeven, Citation2020, p. 3). While this definition of contentious governance is open-ended in terms of involved players, who instigates contention, the means of contention, the focus on policy proposals or implementation, and the targets of contention, we concentrate in this paper on local governmental players joining forces with citizen action groups against project developers and national governmental players.

Strategic interactions

To capture the dynamics of contentious governance processes, we use the strategic interaction perspective developed by Jasper (Citation2006, Citation2011, Citation2015). In this perspective, simple players (individuals) or compound players (collective actors) act strategically, in the sense of being goal-oriented (Jasper, Citation2015). During interactions over a longer time period, these players create and recreate their strategies: ‘you face other players who regard you strategically, just as you do them, and engage in a series of actions in response to others, anticipating their reaction in turn’ (Jasper, Citation2006, p. 6). The interactions imply that players do not only reconsider their own strategies and tactics, but also make sense of what the other players may do and how ongoing events and changing circumstances affect current and future interactions (Jasper, Citation2011).

The analysis of strategic interactions shifts our focus to changes in mutual dependencies between players. Especially local governmental players have to constantly balance how their (re)actions have a bearing on the ongoing relationships with national government and their non-governmental allies (Verhoeven & Duyvendak, Citation2017). To empirically study strategic interactions we need to follow them through time, as unfolding sequences of actions and reactions. Over time, players will engage in turn-taking and will wait for the other player(s) to (re)act, which may happen immediately or at later moments when action makes more sense (Jabola-Carolus et al., Citation2018). Unfolding strategic interactions produce strategic dilemmas for the involved players, which can be seen as situations in which a player needs to make a choice between two or more options that each holds its own risks, costs and potential benefits, while there is not a single right answer (Jasper, Citation2006). Such choices may manifest themselves explicitly, or remain implicit under the influence of habits and routines. Strategic dilemmas can be analyzed through stories and framing processes by which players make sense of them (Schön & Rein, Citation1994) and through tactics by which players try to achieve their goals, based on their explicit or implicit choices (Weible & Heikkila, Citation2017).

Case studies and methods

Our empirical analysis is explorative by empirically identifying strategic dilemmas within each case study. We make use of data from two earlier, separate studies conducted by the first author and the second, third and fourth author respectively: the nearshore wind farm project off the coast of Katwijk, Noordwijk and Zandvoort, a flagship project in the national government’s climate ambition, and the N33 case in Groningen which is one of the longest-running and most contested Dutch cases of onshore wind farm planning. Both cases contain a broad variety of players entangled in complex contentious governance processes in which we expected to find a broad variety of strategic dilemmas. To capture the dynamic nature of the strategic interactions, we use a longitudinal perspective in which we map processes, events and changing interactions within their contexts.

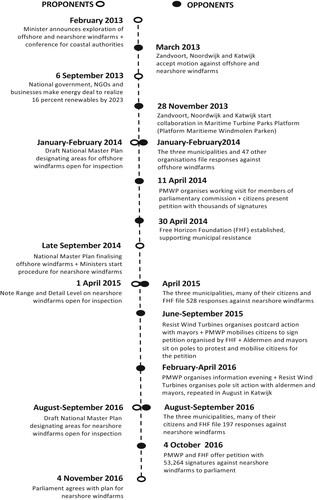

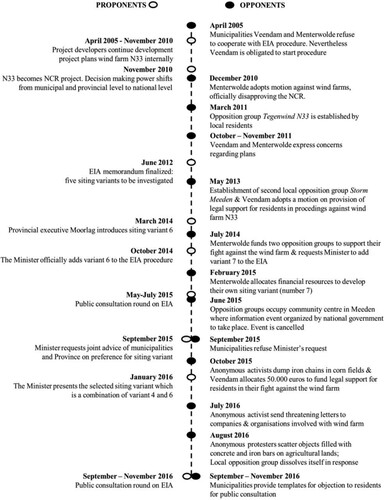

For the near shore case, the first author collected 308 articles (between 2013 and 2015) from Dutch newspapersFootnote1, and 245 policy documents ranging from parliamentary and ministerial documents, municipal motions, and minutes from executive and council meetings. He conducted 8 interviews with 10 deputy mayors, municipal employes, council members, activist citizens and lobbyists in the nearshore case (between June and September 2017). For the N33 case, the second and third author collected 150 articles (between 2005 and 2016) from Dutch national and regional newspapersFootnote2 and 114 policy documents, ranging from parliamentary documents, ministerial documents, municipal motions, minutes from executive and council meetings, and Environmental Impact Assessment documents. They conducted 18 interviews with employes of municipal, provincial and national governments, activist citizens and project developersFootnote3 (between March 2017 and January 2018). In both cases, respondents were selected through snowball sampling and interviews lasted between one and two hours. The interviews were about important events, interactions between municipalities and action groups, interactions with proponents of the contested policy, goals, the use of tactics and framing processes.

Our analysis was directed at the stories of the players about the development of strategic interactions over time. The near shore case was analysed by using open coding in ATLAS.ti to identify interaction patterns of contentious governance by coding specific actions of players and how other players responded to these actions. In this process, we also identified the use of tactics and the framing of problems and solutions by players in these interactions (Schön & Rein, Citation1994). Next, in a round of axial coding, we clustered the obtained codes into families of strategic dilemmas. This analysis allowed us to identify relevant players and construct a timeline and storyline for important events, strategic interactions and tactics. The N33 case was analysed by coding contentious interactions between local and national governments. For each interaction moment, we identified actions and responses by other actors. This was used to construct a thick description of the case, narrated according to three episodes in the governance process. Based on the insights derived from the nearshore case, we distilled strategic dilemmas from the contentious interactions in each of the episodes.

Results

The nearshore wind farm case

The plan to develop a 1400 MW wind farm off the coast of Katwijk, Noordwijk and Zandvoort was a component of the 2012 energy deal between the Dutch national government and forty civil society organizations (Sociaal-Economische Raad, Citation2013). The Ministry of Economic Affairs informed the municipalities about the plans in February 2013.Footnote4 In March the municipal councils of Katwijk, Noordwijk and Zandvoort unanimously adopted motions asking the respective municipal executives (boards of mayor and deputy mayorsFootnote5) to do everything in their power to prevent the wind farm. The main reason for this opposition was that the municipalities feared that the construction of the large wind farm within sight from the coast would severely damage the regional tourism sector. The municipalities argued that the wind farm would lead to a decline in tourism, leading to a loss of about 5,900 jobs and 201 million in spending per year (Trouw, 8-2-2014). Toward the end of November 2013 the three municipalities started to collaborate in the Maritime Wind Turbine Parks Platform (Platform Maritieme Windmolen Parken, PMWP).

Particularly the Platform’s steering group became a vehicle for contentious governance efforts when citizen action groups Free Horizon Foundation (FHF) and Resist Wind Turbines (RWT) regularly joined their meetings. Contention really got underway at the end of September 2014 when the ministry initiated the procedure for the nearshore wind farm inside the 12-mile zone, which would be visible from the coast. From April 2015 until October 2016 the national government presented its plans in several stages. While the three municipalities and the action groups filed responses to these proposals, RWT organized several protest events in which local politicians participated, and FHF organized a petition. Behind the scenes, the municipalities lobbied the ministry and parliament. FHF commissioned several reports on the consequences of the nearshore farm and prepared lawsuits against the plans. During strategic interactions with the ministry, the municipalities and the action groups faced two distinctive strategic dilemmas which developed over time: the ‘naughty or nice’ dilemma and the ‘excluded or captured’ dilemma.

The naughty or nice dilemma

Predating the conflict, the three municipalities were confronted with a smaller nearshore wind farm that was already under construction when they found out about it. After the plans for larger wind farms were announced early in 2013, all three municipalities became rather activistic on the basis of motions allowing the municipal executives to do everything in their power to prevent the plans. Over the spring and summer of 2013 the municipalities discovered the difficulty of persuading the Minister of Economic Affairs to scrap or reformulate the plans. Their strategic interactions with the ministry made the municipalities aware of the naughty or nice dilemma: use protest tactics (naughty) or adopt conventional political tactics (nice)? Following a brief phase of activism they opted to be nice, as one of the deputy mayors indicates:

I do not think it is appropriate for politicians to be activistic towards another government. Instead, try to talk to each other, try to do research that allows you to substantiate your claim (interview deputy mayor).

So in this sense we are of the opinion as a municipality that we must remain a decent cooperation partner. No, we do not agree with the choice; we also make our voice heard, but we do so in a politically correct way (interview municipal employee).

FHF was also partly sponsored by the municipalities (…) and we did not want a conflict of interest. So a new foundation was set up, RWT. And that is where the money [of local entrepreneurs] was put for the campaigning that could be done a little naughtier, you know? If you use local government money, you cannot really go up the barricade with slogans and flyers, et cetera (interview activist).

So I have also sat on that pole here as a politician. But if I actually engage in protest with an action group in The Hague [the seat of national government], that is going a step too far in my opinion. (…) At the national level, I am not concerned with activism but with actually providing the members of parliament and the minister with information that I think is better than the information they are working with (interview deputy mayor).

The excluded or captured dilemma

In their attempts to persuade the ministry and parliament to scrap or reformulate the plans for the nearshore park, the municipalities experienced the dilemma of being discursively excluded or discursively captured by the ministry, based on how they framed their opposition to the plan.

During their activist phase early in 2013, the municipal motions against the nearshore wind farm focused on ‘structural horizon pollution and industrialization of nature’, and the ‘fear’ that ‘touristic attractiveness’ and ‘livability’ would be ‘very seriously affected by a wind farm within the 12-mile zone’ (Zandvoort, Citation2013). The municipalities framed their position in terms of injustices related to local circumstances that would deteriorate. This framing did not convince the ministry at all, and was discarded as reflecting a NIMBY attitude:

We were soon dismissed as NIMBY and as being against wind energy (…) You have a hard time because you are put in a corner that is very difficult to get out of (interview two municipal employees).

After the municipalities readjusted their tactics from activism towards lobbying in the autumn of 2013, they also readjusted their oppositional framing. Their new core argument was that they were not against sustainability or wind energy, as one deputy mayor indicates:

The discussion was no longer about whether or not there are going to be wind turbines. The question was where they should be located (interview deputy mayor).

Listen, you can put 6000 megawatts on ‘IJmuiden far’ and in 2023 you can be done with that. If that is the case, then you will not have added two per cent clean energy, but six per cent. Those are really big steps (interview activist).

Then we also took a different path and made choices to focus much more on the cost aspect. This was due to the rigidity of the ministry (…) to focus mainly on the cost aspect (interview municipal employee).

We were totally sucked into yes-no games about 1.3 billion or 0.7 billion (…) But we had no choice, because at the end of the day this was the button that was pushed every time, in particular by the ministry (interview two municipal employees).

The onshore wind farm case

The plan to develop a 120 MW wind farm in the northeast of the Netherlands, Windpark N33, induced a long-lasting conflict.Footnote6 Since early 2000 the Province of Groningen had been planning for a wind farm to be developed by private parties next to the N33 motorway. In 2005 a group of agricultural land owners started a company to develop plans for a 60 MW wind farm along the N33 (Scheuten et al., Citation2015). The municipalities of Veendam and Menterwolde, on whose territory the wind farm was planned, were against the plan from day one (Meijerman & Wassink, Citation2005). They feared the wind farm would impact the health of local communities and the environment, and would make an already socio-economic disadvantaged region less attractive. This was in the context of existing tensions in the province of Groningen related to earthquakes induced by gas production and historic peat extraction (Cuppen et al., Citation2020). The municipalities tried to counteract this planning process by not complying with administrative procedures, which led to a five-year stalemate.

The conflict escalated again after the National Coordination Regulation (NCR, in Dutch Rijkscoördinatieregeling) was introduced in November 2009. From this moment on, the NCR allowed the Minister of Economic Affairs, in collaboration with the Minister of Infrastructure and Environment, to take over the coordination of planning and permitting procedures from municipal and provincial governments for wind farms over 100 MW (RVO, Citationn.d.).Footnote7 A year later, the land owners proposed a revised plan for a wind farm of 120 MW in the N33 area (Agentschap, Citation2011). However, under the NCR municipalities were now barred from taking legal action against such planning procedures, while citizens were still allowed to do so. Up to this point, opposition was mostly coming from the municipalities. But, these new plans triggered the establishment of local citizen action groups, such as Tegenwind N33 and Storm Meeden. These groups lobbied with politicians, took legal steps against the planning decisions of the two ministries and obstructed a ministerial information event.

The mandatory Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) investigated five siting variants for the 120 MW wind farm between 2011 and 2014, and then in the spring of 2014 a wider EIA investigation into wind energy in the province led the provincial authority to realize that a sixth siting variant ‘scores significantly better on the aspect of quality of life (especially noise and shadow flickering) and energy yield’ (Gerritsen et al., Citation2014). The provincial executive lobbied for this sixth variant, which led the Minister of Economic Affairs to add it to the EIA procedure with the five variants in October 2014.

From 2014 the municipalities and activists employed various tactics to oppose the plan, ranging from developing alternative siting variants and funding legal support for citizen action groups to various forms of protest. As they moved through the various phases of the conflict, the municipalities faced three strategic dilemmas: the ‘abide or avert’ dilemma, the ‘naughty or nice’ dilemma, and the ‘all for one, or one for all’ dilemma.

The abide or avert dilemma

In 2005 the project developers hired a specialist to conduct an EIA for the initial 60 MW wind farm (Scheuten et al., Citation2015), without the consent of Veendam and Menterwolde. This unilateral action created a unique situation:

Normally there is an initiator and then the municipality says ‘an EIA must be conducted and a starting memorandum must be written’. […]. We have done it the other way round: […] we commissioned the writing of the starting memorandum of the EIA study. […] The question is whether you can do that as an initiator. So I used a means of which it was not clear whether it was legal. But I saw it as the only leverage to get it on the political agenda. A starting memorandum has a formal status; municipalities have to make a decision (interview project developer).

In an EIA report, all the aspects of an initiative are assessed. If the outcome of the EIA is positive with respect to placing wind turbines, it will become harder to find reasons to reject placement (Gemeentebestuur Veendam, Citation2005, p. 4).

Based on the fact that the municipal council does not want wind turbines to be constructed along the N33, [..] [do] not cooperate with a zoning plan amendment, [..] [do] not process the EIA Initial Memorandum, and inform the initiators of this [course of action].

Despite the fact that the municipal council does not want wind turbines to be constructed along the N33, cooperate in drawing up an EIA as a means for opinion forming, on the condition that the official hours and external costs of the municipality are compensated by [project developers] (Veendam, Citation2005, p. 1).

To honor their administrative obligation, the mayors and deputy mayors advised their councils to choose the second option. However, the councils feared that cooperation now would create obligations to initiate a formal planning procedure later on, which would undermine their opposition to the wind farm. To solve the abide or avert dilemma, the councils decided to avert by not adjusting the current zoning plans to allow the wind farm (Veendam, Citation2005). For the first time in Dutch history, competent authorities decided not to cooperate with an EIA procedure. As a result, the plan for wind farm N33 was put on hold for several years.

The naughty or nice dilemma

After the NCR came into effect, Veendam and Menterwolde developed an interest in citizen action groups to take legal action against decisions by the ministries. In addition, the municipalities considered obstructing the ministerial decision-making by refusing municipal permits for the construction of maintenance roads for the wind farm. However, refusal of permits came with the risk of placing themselves outside of the decision-making process if the minister chose to intervene. Here, the municipalities faced a strategic dilemma: be nice by cooperating with the permit and thus remain at the negotiating table with all stakeholders, or be naughty by fully supporting the action groups and blocking all permits. In the end, the municipalities opted for a combination of naughty and nice.

The nice element can be found in the municipalities’ participation in the formal wind farm project group throughout the decision-making procedure. Also, the municipalities decided to collaborate with the project developers on permits, in order to gain access to information:

We also sat there [in the project group] more from a position of ‘we can better sit at the table and be informed about what is going on’, but not go along with the creative flow or realization of the wind farm. It was more like ‘yes we are there, but we are against it, be aware of that’ (interview municipal employee).

The naughty element can be found in the municipalities supporting resistance by action groups and residents. First, Menterwolde and Veendam provided templates which residents could use to appeal siting decisions in the formal procedure. Second, both municipalities provided financial resources to legally support individual and organized citizens in their appeals against the plans. As a municipal employe from Menterwolde explains:

That was the council’s [request] to provide legal support to all local residents or everyone in the municipality who appealed. […] But, that will be quite a stretch if you do that, and it will also cost a huge amount. […] As a municipality we have also formulated notices of objection which have been adopted by a number of town councils. They can use those arguments in appeal, […] we want to help them defend those before the Council of State [the highest Dutch administrative court] (interview municipal employee).

The all for one, or one for all dilemma

The sixth siting variant introduced in 2015 created issues of solidarity amongst the three municipalities, in particular for Veendam. In the five earlier variants the 35 wind turbines were to be situated on the territory of Menterwolde and Veendam, while this sixth variant planned to install the turbines in Menterwolde and Oldambt. Veendam came to face an all for one, or one for all dilemma: defend the interests of their own residents and pursue variant six, or defend the interests of all residents affected by the wind farm, including those of Menterwolde and Oldambt, and stay loyal to their municipal neighbors. The deputy mayor chose all for one:

The deputy mayor [..] made a huge effort to keep that park outside the municipal boundaries of Veendam. That is the limitation, I must add: […] the boundaries of the municipality of Veendam. That is not very collegial towards the other municipalities. [The deputy mayor] has not tried, because he says: ‘yes, my job is to do the best for Veendam, and not involve everyone’ (interview municipal employee).

Veendam was really happy that all turbines would be sited above Meeden [a village in Menterwolde]. That is a bit selfish, of course, also towards neighbouring municipalities […]. And then the minister said ‘ [..] lower authorities, just indicate your preferred [siting] variant. Based on that I will make a choice’. Well, Veendam was quick to say ‘we want variant six’. Menterwolde actually thought that was a bit unfortunate because yes ‘then we get all [turbines] on [our territory]’. We have to share the burden (interview municipal employee).

In January 2016, the minister combined variants four and six into a final siting plan. Once Veendam realized they would get wind turbines on their territory, they changed their all for one into a one for all approach again by rejoining Menterwolde and Oldambt in their opposition. In the following years, the three municipalities continued their joint contention of the wind farm. Over time, Veendam even became more outspoken than the others by explicitly questioning the legal validity of the application of the NCR for the N33 wind farm, and therefore the role of the national government in the public consultation procedure (Bureau Energieprojecten, Citation2016).

Discussion

Our empirical findings indicate that local governments may get caught between their local policy positions and national ones being imposed on them, which trigger a sense of threat. In our two cases we see local governments forming a political front to safeguard their policy positions against the national interest. Their weighing of local against national policy positions seems to be shaped by how strong the perceived threat is and how much influence they can exercise on the national governmental players to ward off the threat. Particularly if local governmental players have limited coercive or legal means to contest national plans, they may join forces with other local governments and citizen action groups that share a similar interest, thus weaving a more complex web of governance relations. Limited coercive or legal means can lead to specific strategic dilemmas, as with the excluded or captured dilemma in the nearshore case. Collaborations with other local governments can trigger the all for one, or one for all dilemma, as in the N33 case. And working together with citizen action groups can lead local governments to the naughty or nice dilemma (both cases).

These observations are relevant for other countries where national climate policy plans are implemented locally, especially in situations where the national government is the mandated authority. Our results suggest that hierarchical interventions by national governments create a situation where local governments struggle to balance local and national interests. The resulting processes of contentious governance may subsequently lead to delayed implementation of climate policy and at the same time harm relations between different tiers of government, residents/citizens, and developers. On the positive side, such processes of contentious governance are an inherent part of democracy and bring forward specific local values and interests, that are important to defend and include in policy decisions (Cuppen, Citation2018).

Contentious governance may also appear between local governments. When local governments develop wind farms on their own or support energy cooperatives, this may come as a threat to other local governments, e.g. when wind farms are planned close to municipal borders. When one of the local governments is more powerful, the less powerful municipalities may join forces with action groups. This sets off a local inter governmental variant of contentious governance that lacks the multi-level dynamics with a higher tier of government. Local contentious governance can also be intra governmental as different political parties may hold opposing views on wind farm development and join forces with action groups to block plans by their municipality.

Conclusion

Our two cases indicate that local governments engaging in contentious governance of wind energy planning experienced four strategic dilemmas: ‘naughty or nice’, ‘excluded or captured’, ‘abide or avert’, and ‘all for one, or one for all’. These dilemmas have different characteristics, ranging from discursive (excluded or captured) and tactical (naughty or nice, abide or avert) to relational (all for one, or one for all). Such differences highlight the multi-level nature of the choices local governments need to make when engaging in contentious governance on wind farms: how to frame opposition, which tactical adjustments to make, and which allies to collaborate with (or not)? These considerations need to be made in a constant flow of actions, reactions, interpretations of events, and assessments of one’s own and other players’ moves. Hence strategic dilemmas can be seen as junctions at which local governmental players could have gone another way. Once local governments get entangled in the complex web of contentious governance relations, their strategic dilemmas and choices help us to understand how they navigate these complexities. A focus on strategic dilemmas thus helps to provide more evidence on how local governments’ stances towards allies and opponents change over time. Also, strategic dilemmas help to understand strategic and tactical considerations by local governments as responsive to interactions with other players and not always based on predefined strategic plans.

This research has uncovered only the tip of the iceberg about the role of local governments in the contestation of energy planning. To better understand processes of contentious governance, comparative research is of great importance to gain further insight into which strategic dilemmas occur in different contexts and which are unique to a specific institutional context. Research is also needed on the possibilities of intergovernmental and intragovernmental varieties of contentious governance to more fully understand the involvement of local governmental players in the contestation of wind farms. With the pressure on national governments to do more to achieve climate targets, the likelihood of contentious governance is increasing. Besides wind farms, contentious governance can also occur for other forms of renewable energy infrastructure such as solar farms, transmission lines and geothermal wells, or of fossil energy technologies such as hydraulic fracturing or natural gas production. To meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, governments need to see contentious governance thus as an opportunity to learn and experiment with new institutional and governance arrangements.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in the ECPR 2020 joint session ‘How policy conflicts develop: interpretation and action in policy making’ for their comments and suggestions. The first author would like to acknowledge the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies (NIAS) where he worked on this paper during a research leave. We are very grateful to the reviewers for their comments, which allowed us to substantially improve the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Imrat Verhoeven

Imrat Verhoeven is Assistant Professor of Public Policy at the Political Science Department at the University of Amsterdam. His research interests are in processes of contentious governance related to energy controversies.

Shannon Spruit

Shannon Spruit is co-founder of Populytics B.V. Her work (both academically and commercially) focuses on bringing together citizens and governments, understanding conflicts between citizens and governments and how this relates to differences in values.

Elisabeth van de Grift

Elisabeth van de Grift is a PhD candidate at the Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management at Delft University of Technology. Her research interests are in the areas of renewable energy controversies and governance of sustainability.

Eefje Cuppen

Eefje Cuppen is Professor in Governance of Sustainability at the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University. Her research interests are conflict, participation and collaboration in governance of sustainability and innovation.

Notes

1 For the nearshore case, the newspaper articles were selected from a Lexis Nexis search in five national and four regional newspapers, on the basis of peaks in reporting that coincided with peaks in contention.

2 For the N33 case, articles were identified during a search in Lexis Nexis (April 2017). From this point, media was tracked using Google Alerts (key words: ‘windpark N33’). All articles were stored in a database.

3 The interviews mainly focused on local actors as we are specifically interested in investigating this perspective.

4 See supplementary material, for a time line.

5 Mayors and deputy majors form the executive in Dutch municipalities. They play an important role in agenda-setting, are responsible for policy design and guide the implementation of policies, all under democratic control of municipal councils. In addition, they engage in relations and interactions with other tiers of government.

6 See supplementary material, for a time line.

7 In the Netherlands three levels of government are responsible for planning and implementation of energy policy: the national government, the regional government (consisting of twelve provinces) and the local government (consisting of 352 municipalities in 2021).

References

- Agentschap, N. L. (2011). Kennisgeving Inspraak Voornemen Windpark N33. Staatscourant https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stcrt-2011-18303.html (Accessed: February 12, 2020).

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- BMC. (2018). Gemeenten hebben hoge ambities met de energietransitie. Available at: https://www.bmc.nl/binaries/content/assets/bmcnl/pdfs/bmc-onderzoek-energietransitie-2018.pdf (Accessed: 1 March 2020).

- Breukers, S., & Wolsink, M. (2007). Wind power implementation in changing institutional landscapes: An international comparison. Energy Policy, 35(5), 2737–2750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2006.12.004

- Bureau Energieprojecten. (2016). Reactiebundel: Reacties op ‘Ontwerpbesluiten ‘WINDPARK N33’. Available at: https://www.rvo.nl/onderwerpen/bureau-energieprojecten/lopende-projecten/windparken/windpark-n33/fase-1 (Accessed: 8 November 2017).

- Cuppen, E. (2018). The value of social conflicts. Critiquing invited participation in energy projects. Energy Research & Social Science, 38, 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.01.016

- Cuppen, E., Ejderyan, O., Pesch, U., Spruit, S., van de Grift, E., Correljé, A., & Taebi, B. (2020). When controversies cascade: Analysing the dynamics of public engagement and conflict in the Netherlands and Switzerland through “controversy spillover”. Energy Research & Social Science, 68, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101593

- Cuppen, E., & Pesch, U. (2021). How to assess what society wants? The need for a renewed social conflict research agenda. In S. Batel, & D. Rudolph (Eds.), A critical approach to the social acceptance of renewable energy infrastructures: Going beyond Green growth and sustainability (pp. 161–178). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Gerritsen, M., Mateman, E., Van Gastel, V., Van Wijk, B., & Ritzen, A. (2014). Verdiepend onderzoek naar zesde variant Windpark N33. Tauw and Ecofys.

- Griggs, S., Norval, A. J., & Wagenaar, H. (2014). Practices of freedom. Decentred governance, conflict and democratic participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Hilgartner, S., & Bosk, C. L. (1988). The rise and fall of Social problems: A public arenas model. American Journal of Sociology, 94(1), 53–78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2781022 https://doi.org/10.1086/228951

- Jabola-Carolus, I., Elliott-Negri, L., Jasper, J. M., Mahlbacher, J., Weisskircher, M., & Zhelnina, A. (2018). Strategic interaction sequences: The institutionalization of participatory budgetting in New York city. Social Movement Studies, 19(5-6), 640–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1505488.

- Janhunen, S., Hujala, M., & Pätäri, S. (2018). The acceptability of wind farms: The impact of public participation. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(2), 214–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2017.1398638

- Jasper, J. M. (2006). Getting your way. Strategic dilemmas in the real world. The University of Chicago Press.

- Jasper, J. M. (2011). Introduction. From political opportunity structures to strategic interaction. In J. Goodwin, & J. M. Jasper (Eds.), Contention in context. Political opportunities and the emergence of protest (pp. 1–33). Stanford University Press.

- Jasper, J. M. (2015). Introduction. Playing the game. In J. M. Jasper, & J. W. Duyvendak (Eds.), Players and arenas. The interactive dynamics of protest (pp. 9–32). Amsterdam University Press.

- Klimaat, M. v. E. Z. (2019). Klimaatakkoord. Ministerie van Economische Zaken en Klimaat.

- Meijerman, A., & Wassink, J. B. (2005). Windpark N 33 - Startnotitie MER. Veendam. Available at: http://www.blaaswind.nl/pdf/raad_veendam.pdf (accessed: 15 November 2017).

- Menterwolde.info. (2014). Menterwolde stelt 10.000 euro beschikbaar voor actiegroepen. Available at: https://www.menterwolde.info/nieuws/meeden/menterwolde-steunt-storm-meeden-en-tegenwind-n33-met-10.000-euro/ (accessed: 15 November 2017).

- Metze, T. (2010). Innovation Ltd. Boundary work in deliberative governance in land use planning [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Amsterdam. https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=fcb7e1a8-b977-4c3e-8f7a-5a7d7ad6dbd2

- Metze, T. (2018). Fuel to the fire: Risk governance and framing of shale gas in the Netherlands. The Extractive Industries and Society, 5(4), 663–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2018.09.016

- Pierre, J., & Peters, B. G. (2020). Governance, politics and the state (2nd edition). Red Globe Press.

- Rand, J., & Hoen, B. (2017). Thirty years of north American wind energy acceptance research: What have we learned? Energy Research & Social Science, 29, 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.019

- Rubin, J. Z., Pruitt, D. G., & Kim, S. H. (1994). Social conflict. Escalation, stalemate and settlement, 2nd edition. McGraw Hill.

- RVO. (n.d.). Rijkscoördinatieregeling. Bureau Energieprojecten – Rijksvoorlichtingsdienst.

- Scheuten, W. M., Groen, M. W., Van Rijn, R., & Bosche, G. (2015). Windpark N33 Veendam/Menterwolde: Startnotitie m.e.r. Grontmij.

- Schön, D. A., & Rein, M. (1994). Frame reflection. Toward the resolution of intractable policy controversies. Basic Books.

- Sociaal-Economische Raad. (2013). Energieakkoord voor duurzame groei.

- Tilly, C., & Tarrow, S. (2015). Contentious politics, second edition. Paradigm.

- Toke, D. (2005). Explaining wind power planning outcomes. Some findings from a study in england and wales. Energy Policy, 33(12), 1527–1539. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2004.01.009

- Veendam, G. (2005). Windpark N33 – Startnotitie MER. Number: 519, Gemeente Veendam, directorate: SO.

- Verhoeven, I. (2020). Contentious governance around climate change measures in the Netherlands. Environmental Politics, 30(3), 376–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1787056.

- Verhoeven, I., & Duyvendak, J. W. (2017). Understanding governmental activism. Social Movement Studies, 16(5), 564–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2017.1338942

- Weible, C. M., & Heikkila, T. (2017). Policy conflict framework. Policy Sciences, 50(1), 23–40. doi:10.1007/s11077-017-9280-6

- Wolsink, M. (1996). Dutch wind power policy: Stagnating implementation of renewables. Energy Policy, 24(12), 1079–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(97)80002-5

- Wüstenhagen, R., Wolsink, M., & Bürer, M. J. (2007). Social acceptance of renewable energy innovation: An introduction to the concept. Energy Policy, 35(5), 2683–2691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2006.12.001

- Zandvoort, G. (2013). Motie windmolenparken near shore, Gemeente Zandvoort.