ABSTRACT

Cities are becoming involved in food governance, with a shift to multi-actor urban food governance taking place. Yet, not all food system actors are equally represented in these governance processes. Facing challenges on participation and social justice, questions arise on how inclusive urban food governance is in practice. This article aims to provide a contribution to this debate by looking at the city of Almere, the Netherlands, in the development of its first urban food strategy (UFS). By assessing the governance network involved in the creation of the UFS this article studies mechanisms of in- and exclusion within this process. Conceptually, the article builds on Manuel Castells’ network theory of power. Methodologically, the article presents a network analysis integrated with qualitative methods. The article finds that the municipality is at the network's centre, trying to balance inclusive versus efficient governance. This highlights the tensions around inclusion in network governance, as a network is only responsible for those included in the network, whereas governments are ultimately responsible for all of their citizens, even if they are not directly included in the governance network. This calls for further reflection on the roles of citizens in urban food governance in a network society.

1. Introduction

Food governance is changing. Due to globalization, nation-states as the primary scale for governing food are increasingly joined by cities (Blay-Palmer et al., Citation2018; Sonnino, Citation2009; Sonnino et al., Citation2019). This turn towards urban food governance includes a more multi-actor process, essentially involving networked governance relations, which holds the potential for a stronger and more diversified civil society engagement (Candel, Citation2014; Manganelli, Citation2020; Renting et al., Citation2012; Sonnino et al., Citation2019).

Yet, this potential might not be lived up to in current urban food governance processes, as not all food system actors seem to be represented in many of these emerging governance networks (Moragues-Faus, Citation2020). Faced with a new governance responsibility on food, many cities appear to struggle to take up this task in an inclusive manner (Halliday et al., Citation2019; Sonnino, Citation2019; Sonnino et al., Citation2019). This becomes even more challenging in light of the growing cultural diversity of the urban population (BCFN & MacroGeo, Citation2018). For instance, less than half of the cities studied by Sonnino et al. (Citation2019) had formal and inclusive food governance mechanisms in place – inclusive here referring to the engagement of a broad variety of food system actors. As cities wrestle with their new governance tasks around food, they are at risk of reproducing inequalities (Moragues-Faus & Battersby, Citation2021). Moragues-Faus and Battersby (Citation2021) therefore call for more research on emerging urban food governance, specifically on engaging with social and cultural aspects to recognize different needs and preferences of diverse citizens.

This paper aims to contribute to this debate by exploring the mechanisms of in- and exclusion at play in urban food governance networks. This requires a conceptual framework that can appreciate changing governance constellations into networked governance and conceptualizes in- and exclusion, which Manuel Castells’ network theory of power provides (Castells, Citation2011, Citation2013, Citation2016) provides this. As Castells’ theory has not been applied yet to the study of in- and exclusion on an urban level, further refinement of this framework is required to make it fit our purpose.

Castells’ theory is applied in a case study on the governance network involved in the creation of the Dutch city of Almere’s urban food strategy (UFS). Almere is an interesting case to study emerging urban food governance and inclusion. While its urban diversity is amongst the highest in the world, this diversity appears not to be reflected in the process of developing Almere’s recent UFS (2020–21), as will be demonstrated in this paper. Using Castells’ approach, within this case study of Almere, in- and exclusion is understood to refer to both process and content, i.e. understanding who is included in the process of formulating the UFS and for what reasons, as well as understanding whose agendas are taken up and whose are left out.

In what follows, a conceptual section outlines the need for a novel perspective to analyse in- and exclusion in urban food governance, and introduces Castells’ network theory of power. Next, the methodology section is provided, followed by the results section presenting the in-depth exploration of the mechanisms of in- and exclusion in the network around UFS, based on Castells’ four types of power. The paper ends with a discussion.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1. Networked governance and in- and exclusion

As the domain of governing shifts from government to governance, the relationship between a government and its citizens also changes. Whereas governments are traditionally understood to be responsible for their citizens, new governance processes through multi-stakeholder arrangements often involve a (governance) network of actors (Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2012; Swyngedouw, Citation2005). Governance network theory (Hajer & Versteeg, Citation2005; Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2012; Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2005) analyses these processes, describing governance networks as a new, polycentric form of governance that consists of ‘relatively stable sets of interdependent, but operationally autonomous and negotiating actors, focused on problem solving’ (Hajer & Versteeg, Citation2005, p. 341).

As power becomes dispersed in networked governance and the roles of government change, the question arises how this shift impacts the legitimacy of decision-making processes (Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2012; Mees & Driessen, Citation2019; Sørensen, Citation2013; Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2005). Participation in a governance network is often shaped by entitlement and status, and takes place within a certain structure of representation (Swyngedouw, Citation2005), which risks favouring ‘coalitions of economic, socio-cultural or political elites’ in imposing the ‘rules of the game’ (Swyngedouw et al., Citation2002). Inclusion is further complicated by tensions between process and content. Stakeholders and citizens may technically be in networks, but fail to have their content represented there (Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2012). Or, the reverse might be true: although not directly represented, specific stakeholder interests might still be included in the network through indirect representation. This raises questions on how in- and exclusion of stakeholders in a networked governance process actually works and how this is shaped by power relations.

2.2. In- and exclusion in urban food governance

These questions also apply within the field of urban food governance, where cities are struggling to redefine their roles in the newly emerging domain of food. Within this context, a governance tool that is gaining prominence is the UFS. UFSs are typically applauded for their ambitions regarding inclusion of a broad spectrum of stakeholders (Hebinck & Page, Citation2017). However, UFS development processes may not always be as inclusive as intended (Cretella, Citation2016; Halliday et al., Citation2019; Hebinck & Page, Citation2017; Sonnino et al., Citation2019). For instance, Cretella (Citation2019) finds that in the case of Pisa, despite ambitions to be participatory, a UFS was still developed from an established network of actors which did not include local grassroots movements. Hebinck and Page (Citation2017) illustrates how in Eindhoven (NL) and Exeter (UK), which both explicitly viewed the UFS as a tool for addressing social inequalities, efforts to include socially vulnerable groups did not succeed.

2.3. Castells’ network theory of power

To better understand how in- or exclusive governance networks are, this paper proposes using Manuel Castells’ network theory of power. While this theoretical perspective is not new to the field of environmental policy and planning (e.g. Bush & Oosterveer, Citation2007), it is usually applied at the global and not the urban level. Castells nevertheless appears as relevant and appropriate for the urban scale, as it has a well-developed theory of power that can serve to deepen our understandings of in- and exclusion in networks, including urban food governance networks.

Castells (Citation1996, Citation1997, Citation1998) conceptualizes the global network society as the new basic social structure of society in the age of globalization, constructed around digital networks of communication that exist on global, national and local levels. Within this new global network society, classical power theories focused on the nation-state no longer suffice to explain power relationships. Castells (Citation2013) therefore proposes a set of power relationships based on in- and exclusion. He defines power as ‘the relational capacity that enables a social actor to influence asymmetrically the decisions of other social actor(s) in ways that favour the empowered actor’s will, interests and values’ (Castells, Citation2013, p. 10).

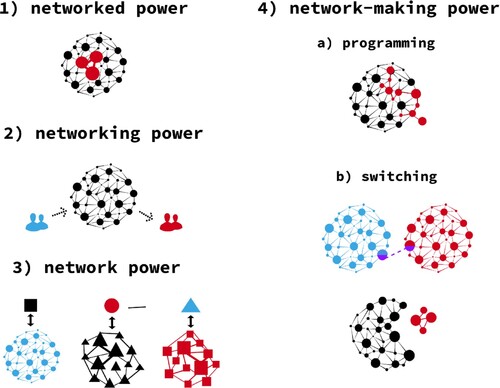

Power in the network society consists of the binary logic of inclusion and exclusion: actors are either in or outside of a network (Castells, Citation2013). Castells defines a network as a set of interconnected nodes, which is a (group of) social actor(s). Nodes can be more or less important, depending on their capacity to influence the network’s programme. Each network is programmed in a certain way, with particular codes and goals. The ability to access, structure, steer and link networks are what constitutes power in the network society. These mechanisms translate into four kinds of power: (1) networked power, (2) networking power, (3) network power and (4) network-making power (Castells, Citation2011, Citation2013, Citation2016) (see ). Whereas the first and second types of power are conventional, the third and fourth are new and characteristic for the global network society.

Figure 1. Power in the network society (based on Castells, Citation2013).

Networked power is the power of certain nodes over other nodes within the network itself. This form of power works differently for each network, depending on its programmed goals. For instance, in food provisioning networks, large food suppliers have been very powerful. This is the most traditional form of power in Castells’ categorization and has gradually lost ground to network-making power.

Networking power is the power of nodes within networks over actors outside networks. Networking power is exercised through gatekeeping, which is the process by which actors within the network can decide who does (not) get access to the network. This type of power can be seen for instance in which social actors or organizations do (not) get invited to stakeholder meetings.

Network power concerns the rules of inclusion, or the power of the standards, ‘protocols of communication’ of the network over its nodes. For example, in order to join the UFS development of Almere, actors need to be professionally or personally associated with the city. These standards can be negotiated by the members of the network, but once set tend to favour the interests of those at the network’s core. Network power increases when the power of the network as a whole grows in relation to other networks as more actors are following the same codes.

Network-making power is the most crucial form of power, new and defining for the global network society. It operates on two basic mechanisms: (a) programming and (b) switching. Programmers can programme and reprogramme the network in terms of its ideas, visions and frames. This is a key function in the network, as control over the programme means being able to pursue one’s own projects and goals. Switchers connect different networks by aligning their goals and combining resources, fostering cooperation and fending off competition. They can do this by combining different networks or by de-coupling parts of the network in response to innovation.

In short, Castells’ four types of power emphasize how in- and exclusion can occur in at least two different ways: through process (being allowed to participate in a network) and content (getting one’s interests and agenda programmed into the network). Network-making power in particular is important for understanding to what extent and how new codes and programmes (such as cultural food diversity or sustainability) are integrated into the governance network when a new process, like developing a UFS, is initiated.

3. Methodology

3.1. Case study

The city of Almere was selected as a case study for this paper because of its urban diversity and recent (2020–21) development of a UFS. Almere is home to 148 nationalities. Currently, 44% of the urban population has a migration background (Gemeente Almere, Citation2021) and this percentage increases, moving toward a majority-minority city where the majority of citizens belongs to a cultural minority group (Crul, Citation2016). Almere is also a city with a higher number of people from lower socio-economic status compared to the Dutch average, which coincides with above-average rates of health issues like overweight and obesity (AlleCijfers, Citation2021; RIVM, Citation2012). Globally, this population group is underrepresented in policy development (Halliday et al., Citation2019), rendering questions about inclusion especially relevant in Almere. Finally, Almere is also relatively active in terms of urban food governance, as it is a member of several city networks around food and one of the first Dutch cities to develop a UFS.

3.2. Methodological design

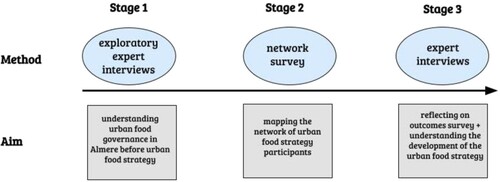

Castells’ theory methodologically fits well with a social network analysis. While social network analyses are generally conducted on a quantitative basis, Luxton and Sbicca (Citation2021) call for studies combining a quantitative and qualitative social network analysis, providing insights into both the ‘structure’ and the ‘story’ of networks The current study builds upon this methodological approach, as illustrated in . Following Sbicca et al. (Citation2019), stage 2 aims to map the ‘structure’ of the network and gives a static understanding of the urban food governance network. Stages 1 and 3 serve to explore the ‘story’ and provide a more dynamic understanding of the network. The first and second stage were conducted in parallel and the third step served as a sequential validation step to check the findings from the survey (step 2). To prepare for the social network analysis and gain a deeper understanding of the local situation, exploratory participant observation at municipal events around food was conducted, including a stakeholder session on the UFS.

In stage 1, three expert interviews were conducted with (ex-)government officials to understand the timeline leading up to the development of the UFS in 2020 (see ). In stage 2, a social network analysis was conducted through a network survey, which was administered to participants who were identified in the preparatory fieldwork as contributors to the UFS (i.e. being invited to participate in the development of the strategy). Participants were asked to list up to five parties that were directly important to their organization in the field of food, which were subsequently assessed in terms of frequency of contact, dependency and type of exchange. The survey was distributed by email. 26 people representing 17 different organizations completed the survey (65% response rate). Rather than including one entry per organization, all separate entries were included into the network analysis. This is because the network analysis aims to map where the centre of power lies in the urban food governance network (networked power), which includes noting whether some parties are more represented than others.

Table 1. Expert interviews.

During stage 3, twelve additional semi-structured interviews were conducted (see ). Participants were recruited from different kinds of organizations based on their role in the UFS development and/or their position in the urban food governance network of Almere. These interviews served to reflect on the survey findings and on the process of the UFS development.

All interviews were transcribed in their native language (Dutch). Quotes used in this paper were translated by the first author, who is a native Dutch speaker. The network survey was analysed using Excel and UCINET, a network software programme.

4. Results

In this section, first a historical perspective is given on how food entered the urban governance agenda in Almere and led to the UFS development. Next, the urban food governance network around the UFS is assessed and dynamics of in- and exclusion are identified.

4.1. Food on the urban agenda

While food production was part of city planning from the city’s inception (Jansma & Wertheim-Heck, Citation2021), it has not always been strongly present in the municipality in subsequent decades. Only recently did it enter the urban agenda, whereby Almere’s winning bid in 2012 to host the Floriade in 2022 played an important role. The Floriade is a travelling horticulture exhibition in the Netherlands which is held every ten years. For this bid, a vision was developed inspired by the location of Almere in the food-producing province of Flevoland. This led to the Floriade’s theme of ‘Growing Green Cities’ with a sub-theme on food called ‘Feeding the City’. In preparation for this Floriade, a ‘youth Floriade’ was developed by the municipality which included the appointment of ‘Urban Greeners’: a group of ten young entrepreneurs working on sustainability and alternative food provisioning.

The success of this project eventually inspired the thematic focus on urban food provisioning of the Flevo Campus, a knowledge hub financed by the municipality and the province. This hub consists of two parties: Aeres University of Applied Sciences Almere and the Amsterdam-based research institute Advanced Metropolitan Solutions (AMS):

We connected with one of the lines of the Floriade, and that was Feeding the City. So early on with the Floriade, we had food as one of the pillars. And this Feeding the City, the Floriade, the youth Floriade, the Urban Greeners, entrepreneurs who joined, and especially entrepreneurs increasingly in Almere itself, that's how the Flevo Campus gradually came into being. (I03)

4.2. The urban food strategy

The decision to draw up a UFS was formally taken in 2020. The process of drawing up this UFS was facilitated by Food Cabinet, an Amsterdam-based company. The process took place in three main phases involving different stakeholders. First, an expert panel and a supervisory committee were established, both of which met around five times. The expert panel started off with three members, all applied researchers with extensive knowledge of Almere and food (including I04). To also promote more local involvement, two additional panellists were invited: one from Rabobank – a bank serving as an important knowledge partner on food – and one from Flevofood (I10), a network organization of food entrepreneurs from Flevoland promoting local food. A supervisory committee was founded with three core members: one from the Economic Board of Almere, one from Aeres University of Applied Sciences, and one from Flevo Campus (and sometimes joined by I06 as municipality representative). This committee was tasked with a more methodological reflection on for instance the right approach for a UFS within the specific political context of Almere. Finally, a ‘practice committee’ was established through interviews with 10 stakeholders, who were selected based on recommendations from the expert panel.

This process resulted in a draft UFS document, which was presented in a live stakeholder meeting in August 2020. The discussions during the meeting were used as further input for finalizing the UFS. The final version was approved by the city council in April 2021 and contained three core ambitions for 2021–2025: (1) healthy food choices for everyone; (2) a sustainable food economy; (3) promoting local and regional products and initiatives (Groen en Gezond Almere, Citation2020).

4.3. Network analysis

A network analysis was conducted based on the network survey. Networks can be analysed through centrality measures, including degree centrality (Zhang & Luo, Citation2017). This is useful to quantify an actor’s r elative power within a network based on their relations to other actors. Degree centrality can be divided into in-degree and out-degree centrality (Zhang & Luo, Citation2017). In-degree centrality refers to how many external ties from other nodes a certain node receives. A relatively high in-degree score indicates that a node is prominent, as other nodes seek connection to it. Out-degree centrality refers to how many ties are directed outwards from a node, towards other nodes. The in-degree score is most relevant when understanding Castells’ first form of power, i.e. networked power, which looks at which actors have the most power within the network itself.

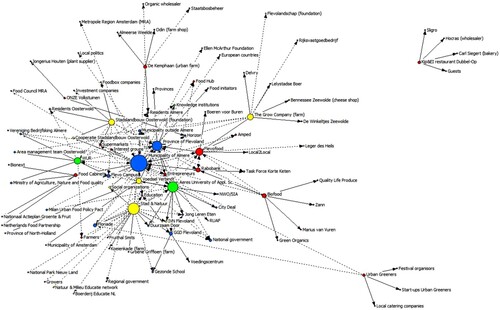

shows the network based on combined in- and out-degree centrality, which means the larger the node, the higher the total degree score. The network is coloured in terms of type of actor, where a blue node is a government actor, red is business, green is research, yellow is civil society and grey is ‘other’. It is relevant to understand what types of actors tend to be most central in the governance network, which will be elaborated later under networked power. Overall, 95 different parties or nodes were included, which were mentioned by the total of 17 different organizations that filled out the survey. Two types of connections between nodes are distinguished: direct collaboration (solid lines) and indirect collaboration (dotted lines).

For this network, the average combined direct and indirect in-degree score of a node is 2,03 (direct 1.21, indirect 0,79), with a range between 0 and 14 (direct 0–9, indirect 0–6, see ). 37% of involved parties have a total in-degree score of >1 (21% direct, 16% indirect), and only 12% of all parties have a total in-degree score of >3. With a total of 95 parties, these scores indicate that the network is not very centralized. This is in line with how many interviewees (I02, I03, I04, I05) described the field of food in Almere, as relatively scattered and small-scale with many small initiatives and businesses. ().

Table 2. Nodes with total in-degree centrality >3 (ranked by total in-degree score).

Table 3. Top 10 out-degree centrality.

The survey also assessed the strength of ties between nodes by asking about frequency of contact and dependency. All ties were attributed scores between 0 and 2 based on frequency of contact (daily + weekly = 2; monthly = 1; half-yearly and yearly = 0) and dependency (completely/largely dependent = 2; partially dependent = 1; largely/completely independent = 0). Together, these scores contributed to an understanding of the strength of ties between the different nodes: the higher the combined score, the stronger the tie. If multiple ties existed between two nodes, their scores were averaged. Tie strength was analysed for ties between different types of actors (e.g. between government and business actors, see ). The average tie strength amounts to 1.9. Business to business ties are the most prominent and score relatively high in terms of tie strength at 2.1 (see ). In general, civil society actors tend to have relatively strong ties to their partners.

Table 4. Tie strength per tie type.

4.4. Networked power

Networked power – the power of certain nodes over other nodes within the network itself – has shifted in the urban food governance network over the past decades:

Until a few years ago, not a single municipality was talking about food. It was national policy or European policy for regulation, international market for production, etc. We were going around in circles, and every time the question came back to: what is our role as a municipality? (I06)

Does the food strategy belong to the municipality or to the city? If the latter, then it should not only be approved by the city council, but also by Flevofood and by Aeres University of Applied Sciences, etc. That’s easier said than done, because then what exactly is the status of the strategy? It all gets a bit complicated. And there's quite a lot of government money involved, so that also legitimizes that the council says: this is government money, so we want to be able to decide for ourselves what we do with it and be accountable for it. Eventually the strategy came to be the municipality’s. (I06)

Internally, the municipality struggled to convince city council members and civil servants of the importance of a healthy and sustainable food agenda (I01, I03 and I06). While in 2018, the city council drew up and approved an ambitious Sustainability Agenda, the daily reality in the council and civil service was much less idealistic (I06). I01 described that whenever a new fast-food chain opened in the city centre, half of the civil servants were cheering. This climate made it difficult to decide whether the municipality’s role should be normative or more facilitating. The most fitting strategy according to I01 was to take a guiding rather than a normative role. This stems from municipal employees’ (I01, I02, I03, I06) impression of Almere’s citizens as not too concerned with food, which calls for a more cautious approach rather than being too regulating:

I think that food is quite an issue among the yuppies in the big cities, who are concerned with healthier, more sustainable and local food and often have the means and knowledge. I noticed that it was really a lot less popular in Almere. There is a certain group of ‘converts’ who are very concerned about it, but on the other hand you also have a very large group of people who just go to the supermarket, who don’t always buy the healthiest food there, are completely unaware of the agricultural hinterland in Flevoland, of the fact that the potatoes they eat could come from there but arrive on their plate with an enormous detour, don’t look at the packaging, really aren’t concerned about any of this. (I02)

While business actors are represented in the top 5 most powerful nodes in the network (see ), individual entrepreneurs or businesses had low in- and out-degree centrality scores. This indicates a low level of networked power. The high position of Flevofood (no. 3) is an exception, which can be explained by the fact that Flevofood rather than being a single business, represents a network of entrepreneurs. I03 recalled missing the voice of local food entrepreneurs in the food debates that were going on during his time at the municipality (2010–2018). The peripheral position of individual entrepreneurs is in line with other survey findings, where half of the participants (n = 13) felt that involvement of businesses in the UFS was limited, despite almost everyone (n = 25) indicating that businesses should be involved. The concept of network power explains this peripheral position and associated mechanisms of exclusion in more detail, which will be elaborated later.

4.5. Networking power

Networking power is the ‘gatekeeping’ power of nodes within the network over those outside of the network (Castells, Citation2013). This power is exercised by the municipality as commissioner of the UFS, the external facilitators and the expert panel. The municipality exercised networking power in making the important decision on who would facilitate the UFS development, i.e. who would be given further networking power to decide whom to include in the UFS development process, illustrating dynamics of inclusion. A company based in Amsterdam was selected, which evidently excluded other Almere-based initiatives like I05, I09 and I10 who had already developed a proposal for a UFS a few years earlier. The choice for this company was therefore criticized by I09:

I think much more use should be made of the knowledge and expertise of the Almere people themselves, instead of saying, there is a very good organization in Amsterdam, we could hire them in Almere … Then you’re not helping the Almere economy at all, because at some point the knowledge will simply go back to Amsterdam (I09)

One group of actors who clearly lacked networking power were citizens. They were not represented in the network and thus did not formally participate in the UFS development. This was inspired by pragmatic considerations among the external facilitators, given time and resource constraints:

Ultimately the strategy is a political document and it's also true that the city council has the last word, so in that sense it's indirect representation: it's actually the people of Almere who have the floor when it comes to this food strategy. Their involvement is much more indirect. I would have liked to have spoken to a hundred more people in Almere and to have conducted a large survey, etc., but well … (I05)

I remember a meeting on the city farm, and I looked out the window and all of a sudden I saw a group of mostly foreign people with long sticks, and they were ramming against the trees to get the food out, because it was just available to everyone. And that’s when I thought: we’re successful! I don’t know these people and they’re just coming here by themselves to get this food. That’s also a form of Feeding the City. (I03)

With food policy, you could say that so many percent of the supermarket must be local. And, if gardeners have leftover vegetables, that they do not throw them away but can distribute them somewhere. You can make policy on it, but currently that party is not involved at all. Those vegetable gardeners who have their little garden, I think it’s just seen as a hobby and not a lifestyle. And I think when you talk about food policy, you also have to talk about lifestyle and about the market.

4.6. Network power

Next, network power (in the form of rules of inclusion) was held again mostly by the municipality. According to Castells (Citation2013), once set, rules of inclusion tend to favour the interests of those at the core of the network, which was also the case in Almere. The UFS was commissioned and paid for by the municipality who therefore wanted to be able to decide how to go about it (I06), clearly demonstrating a mechanism of inclusion. From this position, the civil servants involved (including I01 and I06) were also able to largely decide the rules of inclusion into the governance network. For instance, being a citizen of Almere by itself appeared to not fit the rule of inclusion, which indicates a mechanism of exclusion. Moreover, participation in the governance network largely involved ‘ … a lot of talking and thinking, and very little doing … ’ (I13), which frustrates in particular small business owners:

At a certain point the networks start to revolve around networking and talking to each other. I’m quite happy to talk too, but then, after six months, you have to get results and then you have to move on. There are a lot of people who are paid to talk, and if you find that out at some point you think: I’m just telling the same thing all over again. Stop talking and do something! So I did stop with a lot of networks because there was too much talking. (I13)

You get your umpteenth spinach smoothie and you see the same people sitting there again and then you think: that one is paid, that one is paid, that one from the health services is also paid, that one is from the government and is also paid and then we have here unpaid and unpaid. (I09)

Finally, network power also took shape through ‘codes’ (Castells, Citation2013) on sustainability. Within the governance network, sustainable food was primarily interpreted in terms of local or regional food as sustainable. This formed another rule of inclusion, as in particular parties working on local food were included, functioning as a mechanism of inclusion. Still, although Almere has over 140 urban agriculture initiatives producing local food (Dekking, Citation2018), these organizations were for the most part not formally included, which also applied to those engaged in foraging practices. Many of these groups work with ‘local’ food but remained out of scope and excluded, which could be due to their smaller scale, limited resources to participate in the network and a less developed identity around ‘local’ food.

4.7. Network-making power

4.7.1. Programming

Programming happened most prominently in the expert panel with the external facilitators, where the main themes for the UFS were selected early on (I04, I05). As a new city, Almere had a well-developed city identity focused on being a pioneering city situated in an agricultural hinterland. This ‘DNA of the city’ (I05) was used to sketch out what this means for Almere in terms of food and informed a distinct proposition for its UFS in comparison to other cities (I05). This informed the initial draft of the UFS, focusing on health and economy. Based on these themes, members for the practice committee and stakeholder meeting were selected as further programmers – although the main themes remained roughly the same in the final UFS. This indicated the large programming power of the expert panel in determining the content of the UFS, effectively operating as a mechanism for exclusion of other content. For instance, although the cultural diversity of Almere’s population was mentioned by I05 in the stakeholder meeting as a central aspect of Almere’s identity, it was primarily framed as a topic for future opportunities, rather than something to be programmed into the current UFS document. As hardly anyone from a non-Dutch background was involved in the UFS development, this was not surprising from a programming and network-making power perspective, but did constitute a mechanism of exclusion.

The identity of Almere also played a role in determining the content of the UFS. This happened through carefully balancing ideals around healthy and sustainable food with how municipal employees perceived Almere as a city reluctant to government interference. I05 described how with each topic in the strategy the expert panel always reflected on whether this point would be just relevant for ‘the converts’ or for all citizens. By starting small in this way in terms of ambition, the aim was to slowly let the programme of the network fan out across the different nodes to include as many different nodes as possible (I05). This can be seen as a mechanism of inclusion:

This is not a city where there is great enthusiasm for influencing behaviour. That just doesn't fit with Almere where people have the space to be allowed to live the way they want to live. That's what we are. And then suddenly taking very far-reaching measures to influence behaviour, that's not going to work. So we dialled it down a notch in the strategy (I06)

4.7.2. Switching

Switching, the second form of network-making power, refers to making and breaking links between different networks or actors. The expert panel contained two important switchers in particular: I10 and I04. Flevofood (I10) successfully connected with the UFS in sharing a common goal on promoting regional food. I10’s powerful position in the expert panel did not come about in isolation, which he explained when describing how he was invited because of his connections with for the municipality:

I am one of the people in Almere who happens to be in this network, who happened to make the choice to find this important for myself, so then roads naturally meet. I talk a lot with [I14] for example from the municipality, and as a result you are in the pot of people who are also asked and you also do more projects with them (I10)

Secondly, I04 was a powerful switcher as he had been involved in food in Almere for over 20 years. He created many different initiatives, associations and networks around food in Almere, which he connected to the practice committee and stakeholder meeting. Although his personal network included many citizen initiatives, these were largely not actively switched onto the governance network. In this respect it is important to mention that, contrary to Flevofood, most citizen initiatives were small-scale and lacked the resources and time to invest in engaging in networking. This functioned as a mechanism of exclusion.

Aside from the expert panel, Flevo Campus was another important switcher. Flevo Campus combined institutional, research and entrepreneurial networks and regularly organized meet-ups where different food actors from Almere met. I14 mentioned the Flevo Campus as an important platform where food is often discussed informally. Informal discussions and networking thus also appeared to play a role in urban food governance, but these are not captured in our conceptual and methodological approach focused on explicit in- and exclusion in the network.

Finally, within the municipality, switching also happened through choosing which policy domains to connect to the UFS, which was decided within the municipality. The domains of economy and health were switched on as the two central pillars of the UFS:

If you limit sustainability to one councillor, the topic will remain small. So it's a fundamental choice to make the subject as broad as possible so that it’s not always on the plate of the councillor on sustainability. It’s a logic to strengthen the support capacity in the council. So when the question was, who is going to pull the cart, it was fairly obvious that the councillor of health would do it because food is often associated with health (I06)

5. Discussion

In this discussion, we first reflect on our empirical findings followed by a theoretical reflection on the value of using Castells for our case.

5.1. Empirical reflections

Our findings illustrate how challenging multi-actor governance is when the power still resides largely with one node (the municipality) that controls most mechanisms of in- and exclusion. We identified various mechanisms. Firstly, the municipality setting the rules of inclusion on how to participate in the network withheld individual entrepreneurs from entering the network and contributing to its programme. This was because of the way participatory practices were designed – with a lot of talking and a lack of financial compensation. Secondly, the municipality demonstrates the tension between inclusive versus efficient governance: how to balance getting things done with including diverse stakeholders in the process. Van de Griend et al. (Citation2019) similarly highlighted the constant trade-off between the proactive and reactive role of the municipality of Ede, the Netherlands, in engaging with citizen initiatives around food. Thirdly, the municipality struggled with balancing ‘raising awareness about food system issues’ with ‘guaranteeing meaningful participation’, similar to the findings of Van de Griend et al. (Citation2019). The eventual role of the municipality of Almere as facilitating rather than as normative illustrates the result of this struggle. This was considered to be the best fit with its citizen population, which was perceived as passive and reluctant about government interference. This perception did however result in the exclusion of citizens from the governance network.

The above analysis shows how in particular municipal employees and their frames about citizens exercised power in the network. By primarily understanding citizens as ‘not much engaged with food’, citizens remained out of view and out of power in creating the UFS. However, our findings uncovered that citizens were actually active in the domain of food – albeit largely in practices outside the scope of the network, such as foraging or allotment gardening. These everyday practices were mostly not switched onto the formal network, indicating a discrepancy between local, practical knowledge and expert knowledge (Cheyns, Citation2011; Hebinck & Page, Citation2017). This threatens the legitimacy of the UFS as a strategy for the whole of the city, rather than for only those included in the network. Moving forward in implementing the UFS, inclusive urban food governance could mean looking more closely at how to engage a range of citizens from across the socio-economic and cultural spectrum. This could mean taking into account how governance is exercised through these practices outside of the formal governance network, which involves looking critically at the way in which current in- and exclusion mechanisms prohibit citizen engagement in the urban food governance (Cornea et al., Citation2017; Moragues-Faus, Citation2020).

These observations particularly matter as the role of cities in food system transformations continues to grow (Sonnino et al., Citation2019). As urban food governance responsibility is increasingly shared with multiple actors who are not democratically elected, the locus of governance may become further removed from citizens, highlighting the democratic tension of governance through networks (Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2005; Swyngedouw, Citation2005). A network is only responsible for those included in the network, whereas governments are ultimately responsible for all of their citizens, even if not directly included in the governance network. This calls for further reflection on the roles of citizens in urban food governance in a network society, exploring more direct forms of inclusion through for instance food policy councils or citizen juries (Smith & Wales, Citation2000).

5.2. Reflecting on castells

Using Castells to explore an urban food governance network has proven insightful for understanding the minute workings of power working in- and exclusion. His four types of power each highlight different mechanisms of in- and exclusion, through ‘old-boys network’ strategies (networked power), by declining participation with an appeal to the non-fit with existing codes (network power) or by the perceived (ir)relevance of the new actors for the network (networking power). For instance, while from a traditional networked power perspective the municipality holds most power over other nodes in the network, the concept of network-making power nuances this by also identifying some other influential actors such as Flevo Campus and Flevofood. This approach has thus proven useful to understand some specific dynamics of in- and exclusion.

On the other hand, although proposed as an addition to governance network theory for its elaborate analytical toolbox to understand in- and exclusion, the application of Castells’ theory in this paper proved to be less appropriate for grasping the actual nuances of in- and exclusion in governance processes. Several challenges can be identified. In Castells’ approach, in- and exclusion is binary: a node is either in or outside of the network. The role of indirect representation (‘indirect inclusion’) of citizens through elections is therefore hard to capture in Castells’ framework, as the political reality of urban food governance proves to be more complex than his binary understanding. Moreover, next to formal participation or inclusion in the network, there are also informal processes taking place outside of the official channels that might also influence the programming of the governance network, e.g. through Flevo Campus or through citizen initiatives lobbying with specific civil servants or councillors.

Furthermore, even though some parties were officially included in the governance network, the extent to which their participation was meaningful – in the sense that their ideas and values were taken up – was also difficult to grasp using Castells. As some frustrated individuals indicated that participation is often ‘a thin layer of veneer’, it is evident that inclusion in a network does not necessarily equal inclusive urban food governance. Inclusion through formal participation is one aspect, but what this inclusion actually means in terms of interests being taken up into the programming of the governance network is something completely different (see also Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2012). For instance, the UFS’s thematic focus was already decided early on and was not substantially changed after additional stakeholders participated in the next phases of the UFS development. This could simply mean that they were recognized by all. However, it could also indicate that participation in the later phases technically meant inclusion in the process but not in terms of influence on content. It is hard to distinguish these alternatives using Castells.

Finally, for Castells, network-making power is the most important form of power. Our findings support this by showing how other forms of power are linked to network-making power. For instance, the expert panel held network-making power by programming health and economy as the main topics for the UFS early on in the process. By doing this, they were able to exclude other domains and the associated (groups of) actor(s), i.e. exercising networked power. While Castells’ concept of network-making power is useful in bringing out how codes come about, a more detailed analysis on exactly how these codes exercise discursive power can be challenging using Castells. Additional analytical toolboxes such as critical discourse analysis could prove useful here, which specifically zooms in on how power relations are formed and reinforced through language (Fairclough, Citation2013). An example here is De Krom and Muilwijk (Citation2019)’s analysis of Dutch food policy (for other examples see also Ehgartner, Citation2020; Tessaro, Citation2022).

Still, it remains difficult to conclude whether the perceived lack of nuance around discourse, the meaning of inclusion and the role of informal networks is due to the use of Castells or rather due to the choice of a network analysis as primary method. This is because a network analysis approach reinforces the binary distinction between in- and exclusion that is present in Castells, by primarily recognizing and mapping links between organizations, without leaving much room for the quality and content of these links. Further research could therefore explore using Castells on a similar topic but using for instance discourse analysis as a method, to evaluate what this theory-method combination might bring that a network analysis could not and to further assess the value of Castells’ network theory of power for urban food governance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anke Brons

Anke Brons is a post-doctoral researcher at the Environmental Policy Group at Wageningen UR, the Netherlands. Her PhD focused on questions of inclusiveness around healthy and sustainable food practices in a Western urban context, from a sociological perspective. Her research interests include sustainable consumption, food systems, social equity and social practice theories.

Peter Oosterveer

Peter Oosterveer is a professor at the Environmental Policy Group at Wageningen UR, the Netherlands. His research interests are in global public and private food governance arrangements and innovative institutional developments in sustainable food production and consumption. He is studying food consumption practices from a sociological perspective and is particularly interested in how consumers access sufficient, sustainable and healthy food.

Sigrid Wertheim-Heck

Sigrid Wertheim-Heck is an associate professor at the Environmental Policy Group at Wageningen UR, and a professor at Food and Healthy Living at Aeres University of Applied Sciences, both in the Netherlands. Her interest in global urban food security informs her research on the relationship between metropolitan development, food provisioning and food consumption, focusing on equitable access to sustainable, safe and healthy foods.

References

- AlleCijfers. (2021). Informatie Gemeente Almere. https://allecijfers.nl/gemeente/almere/

- BCFN & MacroGeo. (2018). Food & migration: Understanding the geopolitical nexus in the Euro-Mediterranean. https://paper.foodandmigration.com

- Blay-Palmer, A., Santini, G., Dubbeling, M., Renting, H., Taguchi, M., & Giordano, T. (2018). Validating the City Region Food System approach: Enacting inclusive, transformational City Region Food Systems. Sustainability, 10(5), 1680. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051680

- Bush, S. R., & Oosterveer, P. (2007). The missing link: Intersecting governance and trade in the space of place and the space of flows. Sociologia Ruralis, 47(4), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2007.00441.x

- Candel, J. J. (2014). Food security governance: A systematic literature review. Food Security, 6(4), 585–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-014-0364-2

- Castells, M. (1996). The rise of the network society (Vol. 1). Blackwell.

- Castells, M. (1997). The power of identity (Vol. 2). Blackwell.

- Castells, M. (1998). End of millennium (Vol. 3). Blackwell.

- Castells, M. (2011). A network theory of power. International Journal of Communication, 5, 773–787.

- Castells, M. (2013). Communication power. OUP Oxford.

- Castells, M. (2016). A sociology of power: My intellectual journey. Annual Review of Sociology, 42(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081715-074158

- Cheyns, E. (2011). Multi-stakeholder initiatives for sustainable agriculture: Limits of the ‘inclusiveness’ paradigm. In S. Ponte, J. Vestergaard, & P. & Gibbon (Eds.), Governing through standards: Origins, drivers and limits (pp. 318–354). Palgrave.

- Cornea, N. L., Véron, R., & Zimmer, A. (2017). Everyday governance and urban environments: Towards a more interdisciplinary urban political ecology. Geography Compass, 11(4), e12310. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12310

- Cretella, A. (2016). “Urban food strategies. Exploring definitions and diffusion of european cities’ latest policy trend”. Metropolitan Ruralities (Research in Rural Sociology and Development), 23, 303–323. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1057-192220160000023013

- Cretella, A. (2019). Alternative food and the urban institutional agenda: Challenges and insights from Pisa. Journal of Rural Studies, 69, 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.04.005

- Crul, M. (2016). Super-diversity vs. assimilation: how complex diversity in majority-minority cities challenges the assumptions of assimilation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(1), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1061425

- Dekking, A. J. (2018). Stadslandbouw in Almere: De stand van zaken op 1 november 2017. https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/stadslandbouw-in-almere-de-stand-van-zaken-op-1-november-2017

- De Krom, M. P. M. M., & Muilwijk, H. (2019). Multiplicity of perspectives on sustainable food: Moving beyond discursive path dependency in food policy. Sustainability, 11(10), 2773. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102773

- Ehgartner, U. (2020). The discursive framework of sustainability in UK food policy: The marginalised environmental dimension. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(4), 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1768832

- Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis. Routledge.

- Gemeente Almere. (2021). Almere in Cijfers. https://almere.incijfers.nl/dashboard

- Groen en, Gezond Almere. (2021). Voedselstrategie. https://groenengezond.almere.nl/themas/voedsel-bewegen/voedselstrategie

- Hajer, M., & Versteeg, W. (2005). Performing governance through networks. European Political Science, 4(3), 340–347. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.eps.2210034

- Halliday, J., Torres, C., & Van Veenhuizen, R. (2019). Food Policy Councils: Lessons on inclusiveness. https://wle.cgiar.org/food-policy-councils-lessons-inclusiveness

- Hebinck, A., & Page, D. (2017). Processes of participation in the development of urban food strategies: A comparative assessment of Exeter and Eindhoven. Sustainability, 9(6), 931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060931

- Jansma, J. E., & Wertheim-Heck, S. C. (2021). Thoughts for urban food: A social practice perspective on urban planning for agriculture in Almere, the Netherlands. Landscape and Urban Planning, 206, 103976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103976

- Klijn, E.-H., & Koppenjan, J. (2012). Governance network theory: Past, present and future. Policy & Politics, 40(4), 587–606. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655431

- Luxton, I., & Sbicca, J. (2021). Mapping movements: A call for qualitative social network analysis. Qualitative Research, 21(2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120927678

- Manganelli, A. (2020). Realising local food policies: A comparison between Toronto and the Brussels-capital region’s stories through the lenses of reflexivity and co-learning. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(3), 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1740657

- Mees, H., & Driessen, P. (2019). A framework for assessing the accountability of local governance arrangements for adaptation to climate change. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(4), 671–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1428184

- Moragues-Faus, A. (2020). Towards a critical governance framework: Unveiling the political and justice dimensions of urban food partnerships. The Geographical Journal, 186(1), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12325

- Moragues-Faus, A., & Battersby, J. (2021). Urban food policies for a sustainable and just future: Concepts and tools for a renewed agenda. Food Policy, 102124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102124

- Renting, H., Schermer, M., & Rossi, A. (2012). Building food democracy: Exploring civic food networks and newly emerging forms of food citizenship. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 19(3), 289–307. https://doi.org/10.48416/ijsaf.v19i3.206

- RIVM. (2012). Gemeentelijk gezondheidsprofiel Almere. http://www.rivm.nl/media/profielen/profile_34_Almere_gezonddet.html

- Sbicca, J., Hale, J., & Roeser, K. (2019). Collaborative concession in food movement networks: The uneven relations of resource mobilization. Sustainability, 11(10), 2881. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102881

- Smith, G., & Wales, C. (2000). Citizens’ juries and deliberative democracy. Political Studies, 48(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00250

- Sonnino, R. (2009). Feeding the city: Towards a new research and planning agenda. International Planning Studies, 14(4), 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563471003642795

- Sonnino, R. (2019). The cultural dynamics of urban food governance. City, Culture and Society, 16, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2017.11.001

- Sonnino, R., Tegoni, C. L. S., & De Cunto, A. (2019). The challenge of systemic food change: Insights from cities. Cities, 85, 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.08.008

- Sørensen, E. (2013). Institutionalizing interactive governance for democracy. Critical Policy Studies, 7(1), 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2013.766024

- Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2005). The democratic anchorage of governance networks. Scandinavian Political Studies, 28(3), 195–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2005.00129.x

- Swyngedouw, E. (2005). Governance innovation and the citizen: The Janus face of governance-beyond-the-state. Urban Studies, 42(11), 1991–2006. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500279869

- Swyngedouw, E., Moulaert, F., & Rodriguez, A. (2002). Neoliberal urbanization in Europe: Large–scale urban development projects and the new urban policy. Antipode, 34(3), 542–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00254

- Tessaro, D. (2022). Transitions in environmental policy discourse, from ecologically and socially guided to profit-driven: What is the effect of the institutional policy-making process? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 24(1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2021.1956307

- Van de Griend, J., Duncan, J., & Wiskerke, J. S. (2019). How civil servants frame participation: Balancing municipal responsibility with citizen initiative in Ede’s food policy. Politics and Governance, 7(4), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i4.2078

- Zhang, J., & Luo, Y. (2017). Degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality in social network. Paper presented at the 2017 2nd International Conference on Modelling, Simulation and Applied Mathematics (MSAM2017).