ABSTRACT

Despite the increasing popularity of the notion of sustainability, there have been global challenges in effectively addressing environmental problems. One of the key strengths of the sustainability concept is its ability to coordinate and unite otherwise contending groups. Because of this bridging function, however, the concept remains necessarily ambiguous, which can obscure existing inconsistencies and tensions and thereby block the successful translation into concrete policy action. In this study, we analyse how environmental sustainability is understood within semi-rural communities in the Canadian province Alberta, which exhibits a heavy economic reliance on fossil fuels and a strong conservative voter base. By carrying out a Q-method study in two characteristic towns, we were able to identify three competing sustainability perspectives: ‘Radical transition towards a post-fossil society’, ‘Maintaining the Albertan way of life’, and ‘Technological innovation and growth’. The study findings emphasize the embeddedness of sustainability framings in the cultural and socioeconomic context. Furthermore, the uncovered perspectives not only reveal conflicting viewpoints, but also areas of consensus as well as points which could be considered as neutral. It is argued that policy action should acknowledge both the place-specific nature as well as the nuance and complexity of environmental discourses to be effective.

1. Introduction

Climate change and environmental degradation are arguably one of the most pressing issues facing the world today and require coordinated global action. Actionable plans and policies need to be implemented to combat rising greenhouse gas emissions and other environmental issues, and indeed many governments and organization have developed such initiatives (Horowitz, Citation2016). These initiatives are underpinned by a growing range of concepts that aim to achieve balance in natural resource use and human development. While the notion of environmental sustainability has become already an established term, other concepts such as green economy, conservation and stewardship, and circular economy have been recently introduced in scholarly, political, and public spheres (Geissdoerfer et al., Citation2017; Heuer, Citation2018; Vries & Petersen, Citation2009). However, despite the increasing prominence of these concepts, progress in environmental protection has been slow, and scientists warn that we have already started to cross critical tipping points in our natural Earth System (Steffen et al., Citation2015).

One of the reasons for this slow progress is increasing political polarization (Mccright & Dunlap, Citation2011). Studies have shown, for instance, that politically conservative groups are less likely to approve climate policies compared to liberal groups due to skepticism towards climate change, and that the conflicts between advocates and opponents of climate policies have been significantly growing in the last twenty years (Ameztegui et al., Citation2018; Capstick et al., Citation2015; Mccright & Dunlap, Citation2011). Canada is an excellent example of how increasing political polarization can block the implementation of effective climate policies. The country has one of the most greenhouse gas intensive economies in the world, and while it has developed strategies for climate mitigation, increasing controversies over policy direction has hindered the government action on these measures (Government of Canada, Citation2021; Mildenberger et al., Citation2016).

While most Canadians believe in climate change and support actions to combat it, climate action policies and initiatives remain controversial in conservative provinces such as Alberta. Alberta has been shown to have a highly polarized population when it comes to climate change belief (Abacus Data, Citation2018; Mildenberger et al., Citation2016). This is reflected in the policy decisions of Alberta’s current conservative provincial government, which is actively rolling back and challenging initiatives set up by the previous provincial current federal government, often citing economic growth as a priority.Footnote1 As Alberta has the highest greenhouse gas emissions in the country, and one of the highest per capita emissions in the world, these policy actions present a serious block to climate mitigation and sustainability goals (Environment and Climate Change Canada, Citation2019).

While attention to polarizing arguments of climate change belief and the priority of economic growth versus climate change mitigation is indeed valuable, public discourses on environmental issues often create a sense of dichotomy, where one is either for the environment, or for the economy. However, this fails to capture the potentially complex and nuanced viewpoints of the population, as it is likely that the rejection of selected environmental policies does not necessarily convey a rejection of environmental values or sustainability initiatives as a whole (Parkins et al., Citation2015). The dichotomous view on environmental issues is also adopted in most of the previous research on environmental sustainability within Alberta and Canada (e.g. Stedman, Citation2004; Sutton, Citation2017). Hence, differentiated analyses of the viewpoints of conservative groups on environmental topics are currently missing.

The need for exploring more nuanced views on environmental issues also arises from the ambiguity that is associated with the notion of environmental sustainability. As shown by several scholars, sustainability as well as other arising ‘green political economy’ concepts (Stevenson, Citation2019) can mean different things to different people (Dryzek, Citation1997/Citation2013; Stirling, Citation2006). This ambiguity is a double-edged sword: On the one hand, it can be seen as the reason for why such concepts become prominent in the first place; for instance, scholars explain the striking resilience of the notion of sustainable development by the fact that it provides room for flexible interpretations and thus acts as a boundary object that allows for coordinating otherwise contending groups (Cairns & Stirling, Citation2014; Fischer & Hajer, Citation1999). On the other hand, the ambiguous nature might also be the reason for the promise-reality gap observed in the environmental domain, as obscuring existing inconsistencies and tensions can block the successful translation of concepts into actions (Stevenson, Citation2019).

While several scholars have shed light on the competing and often implicit frames that gather behind overarching environmental concepts circulating in environmental debates (Connelly, Citation2007; Dryzek, Citation1997/Citation2013; Stevenson, Citation2019), little attention has been paid to the question of how these concepts are understood within local communities. In this study, we contribute to filling this gap by using the Q method to analyse how environmental sustainability is perceived within two semi-rural towns in Alberta. By revealing three distinct narratives, the findings of our study shed a more nuanced light on the sustainability discourses within semi-rural Albertan communities, highlight the place-specific nature of environmental discourses, and offer entry points for policy interventions.

2. Environmental discourses

The analysis of discourses in the context of environmental policies has proliferated over the last two decades (Hajer & Versteeg, Citation2005; Leipold et al., Citation2019). While this has led to a successful establishment of the use of discourse analysis in environmental policy analysis, it has also come along with the emergence of different understandings about what constitutes environmental discourse. Along these lines, Feindt and Oels (Citation2005) distinguished between Foucauldian and non-Foucauldian concepts of discourse. Leipold et al. (Citation2019), in turn, identified three major discourse traditions: (i) a Foucauldian perspective that focuses on the genesis of, and the (omnipresent) power relations associated with dominant discourses, (ii) a sociolinguistic perspective concerned with the ‘mutual effects of social structures, power effects and linguistic content’ (see e.g. Fairclough’s (Citation2010) ‘critical’ discourse analysis), and (iii) a deliberative perspective that is influenced by the work of Habermas and based on the concept of political argumentation and practical reasoning (Fischer & Forester, Citation1993). The latter tradition, which is the one we follow in our paper, emphasizes the ability of political deliberation through analysing competing environmental discourses (Dryzek & Pickering, Citation2017) and tensions between expertise- and experienced-based claims (Fischer, Citation2000).

Accordingly, we define discourse as shared ways of understanding the world (Dryzek, Citation1997/Citation2013). Embedded in language, discourses create coherent narratives of our complex realities and thereby construct meanings and relationships, ‘helping define common sense and legitimate knowledge’ (Dryzek, Citation1997/Citation2013, p. 9). Today, the ways of talking and thinking about the environment is influenced by an increasing number of concepts that are entering environmental debates. There are those who talk about conservation and stewardship, which can be loosely defined as an effort to protect the nature by responsibly managing natural resources (Heuer, Citation2018; Mathevet et al., Citation2018). Proponents of the increasingly popular circular economy approach, in turn, promote a cyclical model of material flows and emphasize material reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishment and repair (Geissdoerfer et al., Citation2017; Korhonen et al., Citation2018). Yet another group subscribes to what can be called a ‘Promethean’ approach, which highlights innovation and technology as the key for resolving environmental problems (Bailey & Wilson, Citation2009; Parkins et al., Citation2015). However, while scholars, policy makers and the wider public are quick in adopting these and other concepts, competing logics, inconsistencies, and tensions are often obscured (Stevenson, Citation2019).

Dryzek (Citation1997/Citation2013) classified environmental discourses based on two dimensions. The first dimension refers to the commitment to the growth imperative of industrialism: while all environmental discourses call for a departure of this growth imperative, this departure can either be reformist or radical. The second dimension refers to whether the departure is seen as something that is required to keep the basic structures of our society functioning (prosaic approach) or as an opportunity or necessity to redefine these basic structures (imaginative approach). In total, Dryzek (Citation1997/Citation2013) discerned nine environmental discourses including, for instance, green consciousness, ecological modernization, economic rationalism, and technology optimism. Each of these discourses not only differ in terms of the above-described dimensions, but also with regard to the key assumptions about natural relationships, storylines about agents and their motives, and metaphors and rhetorical devices used.

In a more recent study, Stevenson (Citation2019) examined the discourses surrounding the Rio+20 Summits and identified three competing core perspectives that underlie the various green concepts that dominate contemporary environmental debates: (i) radical transformation, (ii) cooperative reformism, and (iii) statist progressivism. By dismantling the core logics of the sustainability narratives that are shared in contemporary debates, Stevenson (Citation2019) illustrated the temporal dynamics of environmental discourses highlighted by other scholars (e.g. Ehgartner, Citation2020). For instance, while the identified logics shared strong similarities with those identified 20 years ago (Dryzek, Citation1997/Citation2013; Hajer, Citation1996), newly emerging aspects such as monetary valuation were identified.

Based on the understanding that environmental discourses are not only time- but also place-specific (Bickerstaff & Walker, Citation2001; Burningham & O’Brien, Citation1994; Schafft et al., Citation2013), a rising number of studies deal with local perspectives on sustainability issues (Byrne et al., Citation2017; Dempsey, Citation2021; Håvard, Citation2017; Swedeen, Citation2006). Buckwell et al. (Citation2020), for instance, revealed the dominant discourses towards natural resource management within rural communities in Tanna Island, a small Pacific Island state, which is facing increasing environmental pressures from population growth, tourism, and climate change. The authors could show that the identified discourses were strongly shaped by local knowledge, traditional norms, and local challenges such as the lack of jobs and gender inequity. Jepson et al. (Citation2012), in turn, analysed wind power discourses prevalent among stakeholders in Nolan County, Texas, the then epicenter of US wind power. While several competing wind power narratives were presented, it was highlighted that all narratives were underlain by environmental skepticism, which the authors introduced as a ‘deeply rooted ideology prevalent in West Texas’ (p. 862). Hence, previous research suggests that people’s perceptions of environmental issues are influenced by the local context. However, notwithstanding the increasing scholarly attention paid to the local discourses on sustainability issues and initiatives, little is known about how local communities make sense of the general notion of environmental sustainability.

3. Method

To explore how environmental sustainability is perceived within semi-rural communities in Alberta, a discourse analysis technique known as Q method was used (Barry & Proops, Citation1999; Stephenson, Citation1953; Watts & Stenner, Citation2005). Q method is effective in revealing various social perspectives that may exist on a certain issue and allows for complex interactions of opinions (Previte et al., Citation2007; Webler et al., Citation2009). The method provides a structured way to determine stakeholder viewpoints and categorize individual opinions into groups of ‘value positions’, resulting in the development of an overarching social discourse (Webler et al., Citation2009). It has the benefits of providing a nuanced and in-depth approach to uncovering latent value positions within a population while still providing a quantitative analysis of the responses (Zabala et al., Citation2018). By identifying areas of discursive agreement and disagreement and showing how ‘assumptions, values, and ideas fit together into coherent discourses’ (Stevenson, Citation2019, p. 534), the Q method provides a basis for improved dialogue in the context of environmental policies and thereby suits well to earlier work on the theory and practice of deliberative democracy (Leipold et al., Citation2019).

In conducting the Q study, we proceeded as follows: first, a comprehensive series of statements (the so-called concourse) regarding environmental sustainability was obtained from external sources including Canadian and Albertan newspapers, governmental and NGO websites as well as academic journals. The resulting concourse, which consisted of 341 statements, was then organized into general categories, and statements were selected based on the prevalence of certain topics and their relevance to ideas within popular sustainability concepts, resulting in a final ‘Q set’ of 40 statements. While some statements within the concourse were extracted verbatim from the source material, some statements were reworded to be more concise and direct, and some statements were developed based on shared concepts between multiple statements in the concourse, keeping in mind that the original meaning of the concept was not altered.Footnote2 We have consciously chosen to avoid the explicit use of the term climate change due to the political loading of the term and strong division along bi-partisan worldviews and political affiliations.

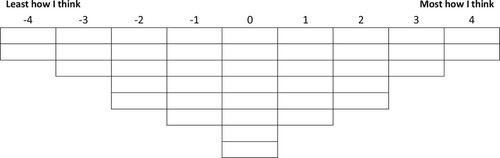

Participants were then recruited from two semi-rural towns in Alberta (Olds and Claresholm) and asked to rank the statements on a bell-shaped distribution, as shown in . The ‘Q-sorts’ were set up on a one-to one basis and were carried out in the months of July and August, 2020.Footnote3 Olds and Claresholm were selected as they were expected to be characteristic for semi-rural viewpoint, based on their size, their economic roots in agriculture and the fossil fuel industry, and their conservative voter base. Individuals were sought for their unique perspective based on their position and experience within their town (i.e. persons who were associated with town council, local organizations, school boards, and so on were prioritized). Individuals whose contact information was available online were primarily contacted, and ‘snowball sampling’ was used after initial contacts responded. Overall, 38 participants were recruited with a wide range of occupations, including town officials, educators, farmers, and volunteers, and diverse demographic profiles.Footnote4

Once the Q sorts were completed, the program PQMethod 2.35 was used to carry out an inverted factor analysis of the Q sorts. The sorts were analyzed using a Principal Components analysis (PCA) and Varimax rotation. The final set of factors (whereby each factor represents one distinct, commonly shared perspective between a sub-set of participants) were selected based on their Eigenvalues (>1) and manual interpretation based on principles of simplicity (having few factors is better), clarity (each participant loads highly on only one factor, limiting confounders), distinctiveness (low correlation between factors), and stability (groups of participants consistently load on same factor) (Webler et al., Citation2009, p. 31). The selected factors for each town were then interpreted based on the normalized factor scores (z-scores) calculated for each statement of the Q set. Transcripts from post-sort interviews were coded by statement number and reviewed to obtain more context for the reasoning and interpretation of the statement placement, based on which participants loaded on each factor.

4. Results

4.1. Identified perspectives

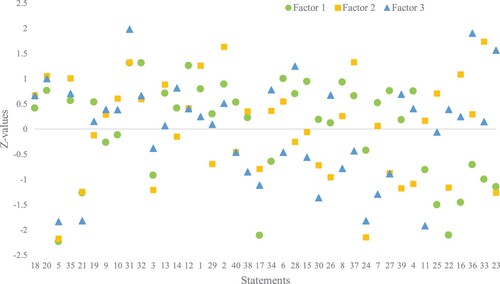

Three factors were extracted from the Q sort analysis. Data related to these factors is shown in . Factors 1 and 2 have a correlation of .40, Factors 1 and 3 have a correlation of .26, and Factors 2 and 3 have a correlation of .39. The factor loadings table, which shows which participants loaded on each factor, can be found in Supplement C. The statement factor scores for all three factors are shown in , and the interpretation of each factor are described below. Note that the numbers in brackets in the factor interpretation indicate the statement number which is being referred to.

Table 1. Factor data extracted from Q results.

Table 2. Factor scores.Table Footnotea

4.1.1. Factor 1: Radical transition towards a post-fossil society

This factor represents the largest explained variance and number of significant loaders. Of the twenty-one people who loaded on this factor, twelve identified as liberal, five identified as conservative, three identified as having mixed views, and one with neutral political views.

The factor shows strong agreement that climate change is influenced by human activity (statement 16) and that the current way natural resources are extracted is harmful (4). It is clearly acknowledged that Canadians must improve their environmental performance and show leadership in achieving environmental sustainability (5), and it is strongly doubted that the oil and gas industry will be able to contribute to such an effort (25, 33). There is support for developing clean energy, and the idea of legislating emission limits or a carbon tax to foster green innovation is not rejected outrightly (11, 24, 30). Still, it is recognized that there are limits to technological solutions (23). People who load on this factor also see the need for minimizing consumption levels, support zero waste principles and believe that recycling should be the norm for all members of the society (6, 8, 32). The idea of unlimited growth is rejected, and it is doubted that a strong economy is foundational in creating a sustainable society (17, 36). In line with this, this factor suggests paying less attention to GDP and focussing more on social and environmental indicators when measuring an economy’s performance (15). Overall, the factor highlights the need for changing the way nature is valuated and is associated with the belief that sustainability requires a radical change of our societal structures (12, 27).

4.1.2. Factor 2: Maintaining the Albertan way of life

Of the eleven people who loaded on this factor, seven identified as having conservative political views, one liberal, one having mixed views, and two being neutral.

People who load on this factor strongly believe that Alberta’s oil and gas industry is undervalued, emphasizing the high environmental standards associated with the industry (33). It is generally believed that current, local natural resource extraction practices are not necessarily harmful (4). This factor also exhibits skepticism towards climate action, highlighting that the climate may be beyond human control (16). Still, although a fast transition towards renewables and a carbon-neutral world is not supported (28, 39), there is optimism in the ability of the oil and gas industry to create technologies and innovations that significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions (25). Furthermore, there is support for zero waste principles (6) and a strong desire for minimizing waste and consumption levels by developing products that are long-lasting (2) and finding creative ways to recycle, reuse and repair (1). In addition, the development of local businesses, farms, and industries is supported (37, 35, 13). As in the previous factor, innovation and technological solutions are not seen as the silver bullet (23) and there is no strong support for the idea that economic growth plays a key role in enabling sustainability and improving the quality of life (36, 22). Overall, people who load on this factor value the traditional Albertan oil and gas industry, for which they don’t see any alternatives (26), but also believe that products and resources should be used responsibly.

4.1.3. Factor 3: Technological innovation and growth

Three people loaded on this factor: two identifying as conservative and one as liberal.

This factor displays support for technological solutions (7), with the strong belief that innovation will overcome future sustainability challenges (23). While the factor is relatively neutral with regards to the ability of humans to control the climate (16), there is support for renewable energy solutions (11, 39) and the belief that Alberta should apply skilled trades and engineering know-how to create more energy solutions and move towards a carbon neutral world (28). As in Factor 1, it is not believed that the oil and gas industry will be part of the low-carbon transition (25), inter alia, because non-fossil solutions are already seen as better investments (26). People who load on this factor are also believe that establishing sustainability requires a strong economy and do not reject the feasibility and benefits of unlimited growth (22, 36). Conversely, they clearly reject the need for a radical change of societal structures (27) as well as the need for government interventions such as emission limits or a carbon tax (24, 30). Neither the reduction of consumption levels nor the incorporation of zero waste principles is deemed necessary (6, 8) and there are doubts about the usefulness of local shopping or community gardens (37, 38). Unsurprisingly, the notions of recycling, repurposing, or repairing are not given strong attention (1, 2). Overall, this factor involves believes that developing technological solutions, powered by a strong economy, is the best way to achieve sustainability.

4.2. Consensus and contention points

The three perspectives represented by the identified factors show several points of contention (). A clear point of disagreement relates to the role of technology in solving environmental issues, as Factors 1 and 2 clearly object the strong optimism of Factor 3 about technological solutions (23). In turn, the emphasis of Factor 1 on the need for a dramatic societal change and a reduction in consumption is clearly rejected by Factor 3 (8, 27). There is also a strong discrepancy in terms of whether the success of sustainability necessitates a strong economy (36). Another point of contention relates to the perception of the environmental performance of the local oil and gas industry (33). While people that load on Factor 2 strongly agree that this industry is undervalued and that Alberta has the cleanest energy practices in the world, this view is rejected by people that load on Factor 1. Unsurprisingly, there are also conflicting perceptions about the capability of the oil and gas industry to develop low-carbon solutions. Finally, there are strongly diverging views in terms of to what degree humans have control over the changing climate (16).

Figure 2. Z-values of the factors for each statement and factor. Statements are ranked in descending order of the standard deviation of the z-values (hence, statements to the left show highest, and statements to the right the lowest consensus).

While these confrontational points illustrate the conflict potential in the existing discourse, the revealed perspectives also show some areas of consensus. For instance, all three perspectives strongly reject the idea that the government plays a key role in addressing environmental issues (21). There is also a clear rejection of the view that Canadians do not need to worry about recycling and reusing waste products (5). All perspectives strongly acknowledge the importance of conserving energy, air, land and water (31). Another point of consensus relates to the common understanding that local initiatives are key to sustainability and that communities should support clean industrial development while embracing their small-town spirit (18, 20, 35), although all three perspectives are rather indifferent about local food production (10).

In addition, there are several points that are neither consensual nor confrontational. For instance, while participants that load on the Factors 1 and 3 see the value of developing clean energy solutions, participants associated with the Factor 2 are relatively indifferent about that point (11). Another example relates to the belief in unlimited growth (22), which is rejected in the Factors 1 and 2 and neither rejected nor embraced in Factor 3. The need for recycling, finding creative ways to reduce waste, and keeping products as long in the economy as possible (1, 2, 32) is emphasized in Factor 1 and 2, while it is not rejected in Factor 3. Furthermore, none of the perspectives rejects the need for paying more attention to the proper valuation, appreciation, and restoration of nature (12). At the same time, all perspectives seem have a critical stance towards carbon pricing, even though there are different degrees of rejection (24). There is also no clear support to implement a maximum emission limit on industries (30). Still, none of the perspectives denies the responsibility of Canada to improve its environmental performance (17).

5. Discussion

5.1. Environmental sustainability as a place-specific concept

Our study results emphasize the importance of considering the local context when analysing sustainability framings. The identified perspective ‘Maintaining the Albertan way of life’ is associated with a group of people whose identities and meaning systems are deeply grounded in the historical structures of the Albertan oil and gas industry. The associated beliefs in a clean oil and gas industry and the optimism about the industry’s abilities to develop low-carbon solutions demonstrate the important role that the local context plays in shaping how communities make sense of environmental sustainability. Respective beliefs are consistent with ‘social practices’ (Shove & Walker, Citation2014) prevalent in Alberta. The oil and gas industry is strongly embedded in the living realities of Albertans: being a major employer, it provides infrastructure and contributes to the livelihoods of community members, therefore, shaping local identities and reinforcing fossil fuel based social practices. At the same time, those who identify with the perspective of Factor 1 exhibit clear levels of pushback towards the fossil fuel industry, revealing that there exists a more nuanced discourse that is still based within the local social structure.

The observed skepticism about the ability of humans to control the climate, seen in Factors 2 and 3, raises the fundamental question of how inclusive the notion of sustainability should be. However, while it seems difficult to reconcile doubts about the anthropogenic influence on the climate with any environmental sustainability logic, dismissing the perspective (or not regarding it as a proper environmental discourse) would not change the fact that the perspective exists and needs to be addressed. For this reason, it is important to understand the perspectives and points of consensus within and between these groups to arrive at viable policy solutions.

Place-specificities also manifest themselves in the absence of the ‘state progressivism’ narrative identified by Stevenson (Citation2019), where the state is the key actor for the transformation towards a sustainable society. The idea that the government is responsible for addressing environmental commitments was clearly rejected in all three perspectives, and none of the identified perspectives supported state-led policies such as the carbon tax or legislated emission limits (albeit the ‘degree of rejection’ differed across the perspectives). The predominance of individualism (and the rejection of a strong state) is deeply rooted in the Canadian and Albertan culture and has been already analysed other contexts such as health policy (McGregor, Citation2001; Raphael et al., Citation2008). Hence, the absence of a ‘state progressivism’ narrative is not surprising and highlights the important roles of cultural aspects in mediating how people make sense of sustainability, substantiating previous research on the cultural dimension of sustainability (e.g. Horlings, Citation2015; Brocchi, Citation2010).

5.2. Methodological reflections

5.2.1. Limitations of the method

When interpreting the findings of this study, a few limitations need to be kept in mind. A shortcoming of Q method in general is as it relies on a small, non-random sample size, the results cannot be easily extrapolated to a wider population. It is also likely that the nature of the study resulted in self-selection of participants who may have been more interested in discussing environmental sustainability, which would explain why the share of liberal participants was overrepresented in our sample.Footnote5 The responses may also be more limited compared to a more qualitative discourse analysis (such as an interview), and not representative of the ‘true’ values of the participants, since the Q sort was defined by a limited set of statements determined by the chosen framework of the researcher (Zabala et al., Citation2018, p. 1187). It is also acknowledged that the concourse was developed using mainstream media and literature sources, and so different perspectives, such as the Indigenous perspective, may have been excluded.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the Q sorts are done on a relative scale, meaning statements are ranked not necessarily in accordance with the true values of participants, but in accordance with preference relative to other statements (Webler et al., Citation2009). Therefore, it may not be appropriate to assume participants agree with or feel strongly about the uncovered narrative. Some participants also noted that statements which used language such as ‘most important’ or ‘100% of the population’ were too strong and not reflective of how they felt. While Q statements are meant to be more open to interpretation (Webler et al., Citation2009), it is important to keep in consideration that some views may have been hidden or distorted based on the wording of the statement.

Despite these limitations, we still believe that our research was successful in uncovering valid perspectives. To account for the broad topic, a large concourse was compiled. Participants were asked to comment on whether they felt any part of the discourse was missing, and most, if not all, commented that the statements appeared to cover an appropriately broad range. A post-sort interview was also carried out with each participant, where they were asked to describe their interpretation of statements that were most like and least like how they thought. It is therefore believed that the interpretation of the factors is reflective of the values of the participants. Some participants may feel that they do not agree with all points of the factor they loaded on, however, this is to be expected as the factors are a representation of aggregated Q-sorts (Barry & Proops, Citation1999).

Furthermore, we believe the identified perspectives are reflective of the sustainability discourse not only within the communities studied, but also within other semi-rural communities in Alberta. The overrepresentation of people with liberal viewpoints in our sample might give a distorted impression in terms of the perspectives’ prevalence in the overall population of the towns. However, because the Q method does not permit generalizations of this type anyhow, this does not seem to be problematic. Along these lines, it is also not problematic that ‘only’ three participants loaded on the third perspective.Footnote6 The self-selection bias would only be an issue if it led us to neglect additional perspectives. While this risk can never be fully excluded when conducting a Q study, we believe it was relatively low in the context of our study, since we still had a sufficient number of conservative persons in our sample. In addition, we recruited a wide range of community leaders that well represented the varying viewpoints of the population (e.g. the town mayors, county leaders, councillors, school principals or business managers).

Claims about the generalizability to other semi-rural communities must be made with care. It is still reasonable to assume that the identified perspectives are replicable to other semi-rural communities in Alberta for two reasons: First, after collecting the Q sorts, we carried out a factor analysis for each town separately and found that the resulting perspectives were quite similar, despite a geographical distance of 200 km. The second reason relates to the above-mentioned importance of the historical and institutional context in which discourses are embedded. While accepting the place-specific nature of discourses might lead to the conclusion each town or community has its own idiosyncratic discourse, our identified place-specificities relate to higher levels such as the historical structures of the Albertan oil and gas industry or the meta-discourse of individualism. In other words, it appears plausible that the sustainability discourses of semi-rural Albertan towns don’t vary significantly, because they share a similar historical and institutional context.

5.2.2. Q method and discourse analysis

Using the Q method allowed us to reveal the ‘subjectively expressed, but socially organized semantic patterns’ (Watts & Stenner, Citation2005, p. 88) associated with the notion of sustainability in the semi-rural context of Alberta. It is thus a useful approach when understanding discourse as shared narratives that coordinate action through tying together assumptions, ideas, and values in coherent ways (e.g. Dryzek, Citation1997/Citation2013; Fischer & Forester, Citation1993). However, the method might only be of limited use for other discourse analysis traditions. For instance, it provides no information about power relations, which would be of central interest from Foucauldian or sociolinguistic perspectives on discourse (Leipold et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the method neither allowed us to analyse the genesis of the identified perspectives nor to make claims about their prevalence, rendering it unsuitable for scholars aiming at studying discursive hegemony and the processes by which such a hegemony developed. Finally, while scholars call for a materialist conception of environmental discourses and stress the social practices by which they are produced (Griggs & Howarth, Citation2019; Hajer, Citation1996), our approach did not allow us to gain in-depth knowledge about precisely how the identified perspectives relate to material structures and actual practices.

5.3. Policy implications

The findings of this study suggest that policy maker should consider the localized, distinct perspectives in order to establish effective strategies towards sustainability. First, the different positions citizens hold within the existing discourse will result in different levels of acceptance of specific policies targeting sustainability transitions and climate change. This becomes especially clear in the discrepancy between technology optimists on the one hand, and proponents of major societal change on the other. While technology optimists can be expected to reject any policy that targets lifestyle changes, proponents of societal change can be expected to be skeptical of policies that exclusively target the technology side of sustainability transitions.

Second, and on a more optimistic note, the identified consensus points can be useful door openers for sustainability policies. For the towns included in this study, the major points of agreement concerned the need for conservation measures and the focus on local initiatives. The same is true for points that are not consensual, but also not conflicting, such as developing clean energy solutions and fostering recycling and reuse. Thus, policy makers could use local initiatives that target the conservation of air, land, water and resources as logical starting points for more ambitious sustainability transitions.

The absence of a state progressivism narrative and the latent preference for a ‘weak’ state, also observed in related studies (e.g. Parkins et al., Citation2015), make radical top-down policies unlikely to succeed if implemented without including local perspectives and local stakeholders. This could be crucial particularly in the context of smaller communities. Customized solutions at the community level seem more promising when local citizens mistrust the ability of centralist policy makers to properly understand their living realities. Community members feel a closer connection to challenges when they are addressed at a local level, thus fostering greater awareness, acceptance, and participation (Calder & Beckie, Citation2013; Orenstein & Shach-Pinsley, Citation2017). Even if global sustainability problems and climate change are to be addressed, policies are likely to be rejected when they are detached from local social practices and the prevailing discourse. The challenge for national policy makers, therefore, is to get local initiatives on board already in the design phase of ambitious sustainability policies. Such an approach without doubt will increase the complexity of respective endeavours, but eventually will be key to their success.

6. Conclusion

The main objective of this study was to analyse the local understandings of environmental sustainability by using the example of semi-rural communities in the Canadian province of Alberta. Environmental sustainability can be seen an important issue in this province, as it has a highly carbon-intensive economy that is reliant on natural resource development, which contributes to both greenhouse gas emissions and environmental degradation. Through conducting a Q-study with a diverse group of citizens of two semi-rural towns, we could reveal three distinct perspectives on environmental sustainability: (i) Radical transition towards a post-fossil society, (ii) Maintaining the Albertan way of life, and (iii) Technological innovation and growth. While public discourses on environmental and climate policies are becoming more polarized, particularly down lines of political ideology, the findings of our study reveal common grounds across seemingly incompatible positions. They indicate that considering the complex viewpoints on environmental sustainability may help policy makers to find strategies that will be accepted by a wider range of worldviews. In addition, our findings emphasize the importance of acknowledging the place-specific nature of environmental discourses. While sustainability transitions require a global perspective and global action, our study suggests that respective efforts also need to be embedded in local contexts to facilitate broader acceptance.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support by the University of Graz.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 As reported in several newspaper reports. Retrieved April 9, 2022. www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/alberta-war-room-launch-calgary-1.5392371; www.cbc.ca/news/technology/canada-warming-at-twice-the-global-rate-leaked-report-finds-1.5079765; https://globalnews.ca/news/5900012/alberta-climate-change-environmental-monitoring-closes/; https://albertastrongandfree.ca/policy/.

2 The whole concourse, the respective sources as well as the final Q set with the associated categories are shown in Supplement A.

3 Participants were encouraged to follow the distribution of the chart; however, they were informed that it was not forced (see Webler et al., Citation2009; Watts & Stenner, Citation2005). Semi-structured post-sort interviews were also conducted following the recording of the Q sorts. These interviews were voice recorded and later transcribed to be used for reference when analyzing the sorts.

4 See Supplement B for details.

5 While the conservative voter base is by far the strongest in these towns, the political ideology within our sample was spread evenly between liberal and conservative viewpoints, see Supplement B.

6 According to Watts and Stenner (Citation2005), a standard requirement is that an ‘interpretable Q methodological factor must ordinarily have at least two Q sorts that load significantly upon it alone’.

References

- Abacus Data. (2018). Perceptions of carbon pricing in Canada: A survey of 2250 Canadians. Retrieved March 23, 2020. https://ecofiscal.ca

- Ameztegui, A., Solarik, K. A., Parkins, J. R., Houle, D., Messier, C., & Gravel, D. (2018). Perceptions of climate change across the Canadian forest sector: The key factors of institutional and geographical environment. PLoS One, 13(6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197689

- Bailey, I., & Wilson, G. A. (2009). Theorising transitional pathways in response to climate change: Technocentrism, ecocentrism, and the carbon economy. Environment and Planning A, 41(10), 2324–2341. https://doi.org/10.1068/a40342

- Barry, J., & Proops, J. (1999). Seeking sustainability discourses with Q methodology. Ecological Economics, 28(3), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(98)00053-6

- Bickerstaff, K., & Walker, G. (2001). Public understandings of air pollution: The localisation of environmental risk. Global Environmental Change, 11(2), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(00)00063-7

- Brocchi, D. (2010). The cultural dimension of sustainability. In Bergmann & Gerten (Eds.), Religion and Dangerous Environmental Change: Transdisciplinary Perspectives on the Ethics of Climate and Sustainability. LIT Verlag.

- Buckwell, A., Fleming, C., Muurmans, M., Smart, J. C., Ware, D., & Mackey, B. (2020). Revealing the dominant discourses of stakeholders towards natural resource management in Port Resolution, Vanuatu, using Q-method. Ecological Economics, 177, 106781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106781

- Burningham, K., & O'Brien, M. (1994). Global environmental values and local contexts of action. Sociology, 28(4), 913–932. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038594028004007

- Byrne, R., Byrne, S., Ryan, R., & O’Regan, B. (2017). Applying the Q-method to identify primary motivation factors and barriers to communities in achieving decarbonisation goals. Energy Policy, 110, 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.08.007

- Cairns, R., & Stirling, A. (2014). Maintaining planetary systems’ or ‘concentrating global power?’ High stakes in contending framings of climate geoengineering. Global Environmental Change, 28, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.005

- Calder, M. J., & Beckie, M. A. (2013). Community engagement and transformation: Case studies in municipal sustainability planning from Alberta, Canada. Community Development, 44(2), 147–160.

- Capstick, S., Whitmarsh, L., Poortinga, W., Pidgeon, N., & Upham, P. (2015). International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 6(1), 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.321

- Connelly, S. (2007). Mapping sustainable development as a contested concept. Local Environment, 12(3), 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830601183289

- Dempsey, B. (2021). Understanding conflicting views in conservation: An analysis of England. Land Use Policy, 104, 105362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105362

- Dryzek, J. S. (2013). The politics of the earth. Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1997).

- Dryzek, J. S., & Pickering, J. (2017). Deliberation as a catalyst for reflexive environmental governance. Ecological Economics, 131, 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.09.011

- Ehgartner, U. (2020). The discursive framework of sustainability in UK food policy: The marginalised environmental dimension. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(4), 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1768832

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. (2019). Achieving a sustainable future: A federal sustainable development strategy for Canada 2019 to 2022 (Cat. No. En4-136/2019E-1-PDF). Government of Canada.

- Fairclough, N. (2010). Critical discourse analysis. The critical study of language. Routledge.

- Feindt, P. H., & Oels, A. (2005). Does discourse matter? Discourse analysis in environmental policy making. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 7(3), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080500339638

- Fischer, F. (2000). Citizens, experts, and the environment: The politics of local knowledge. Duke University Press.

- Fischer, F., & Forester, J. (Eds.). (1993). The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning. Duke University Press.

- Fischer, F., & Hajer, M. A. (1999). Living with nature: Environmental politics as cultural discourse (pp. 1–20). Oxford University Press.

- Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M. P., & Hultink, E. J. (2017). The circular economy – A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production, 143, 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.048

- Government of Canada. (2021). Greenhouse gas sources and sinks: Executive summary 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2022. www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange.html

- Griggs, S., & Howarth, D. (2019). Discourse, policy and the environment: Hegemony, statements and the analysis of U.K. airport expansion. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(5), 464–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1266930

- Hajer, M. (1996). The politics of environmental discourse. Ecological modernization and the policy proccess. Oxford University Press.

- Hajer, M., & Versteeg, W. (2005). A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: Achievements, challenges, perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 7(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080500339646

- Håvard, H. (2017). Constructing the sustainable city: Examining the role of sustainability in the ‘smart city’ discourse. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 19(4), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1245610

- Heuer, M. (2018). Defining stewardship: Towards an organisational culture of sustainability. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 40(40), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2010.wi.00005

- Horlings, L. G. (2015). The inner dimension of sustainability: Personal and cultural values. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 14, 163–169.

- Horowitz, C. (2016). Paris agreement. International Legal Materials, 55(4), 740–755. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020782900004253

- Jepson, W., Brannstrom, C., & Persons, N. (2012). We don’t take the pledge: Environmentality and environmental skepticism at the epicenter of US wind energy development. Geoforum, 43(4), 851–863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.02.002

- Korhonen, J., Honkasalo, A., & Seppälä, J. (2018). Circular economy: The concept and its limitations. Ecological Economics, 143, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.06.041

- Leipold, S., Feindt, P. H., Winkel, G., & Keller, R. (2019). Discourse analysis of environmental policy revisited: Traditions, trends, perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(5), 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1660462

- Mathevet, R., Bousquet, F., & Raymond, C. M. (2018). The concept of stewardship in sustainability science and conservation biology. Biological Conservation, 217, 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.10.015

- Mccright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2011). The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010. Sociological Quarterly, 52(2), 155–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01198.x

- McGregor, S. (2001). Neoliberalism and health care. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 25(2), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2001.00183.x

- Mildenberger, M., Howe, P., Lachapelle, E., & Stokes, L. (2016). The distribution of climate change public opinion in Canada. PLoS One, 11(8), e0159774. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159774

- Orenstein, D. E., & Shach-Pinsley, D. (2017). A Comparative Framework for Assessing Sustainability Initiatives at the Regional Scale. World Development, 98, 245–256.

- Parkins, J. R., Hempel, C., Beckley, T. M., Stedman, R. C., & Sherren, K. (2015). Identifying energy discourses in Canada with Q methodology: Moving beyond the environment versus economy debates. Environmental Sociology, 1(4), 304–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2015.1054016

- Previte, J., Pini, B., & Haslam-Mckenzie, F. (2007). Q methodology and rural research. Sociologia Ruralis, 47(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2007.00433.x

- Raphael, D., Curry-Stevens, A., & Bryant, T. (2008). Barriers to addressing the social determinants of health: Insights from the Canadian experience. Health Policy, 88(2-3), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.03.015

- Schafft, K. A., Borlu, Y., & Glenna, L. (2013). The relationship between Marcellus shale gas development in Pennsylvania and local perceptions of risk and opportunity. Rural Sociology, 78(2), 143–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12004

- Shove, E., & Walker, G. (2014). What is energy for? Social practice and energy demand. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(5), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414536746

- Stedman, R. C. (2004). Risk and climate change: Perceptions of key policy actors in Canada. Risk Analysis, 24(5), 1395–1406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00534.x

- Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., & Bennett, E. M. (2015). Sustainability. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347(6223), 1259855. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855

- Stephenson, W. (1953). The study of behaviour: Q technique and its methodology. University of Chicago Press.

- Stevenson, H. (2019). Contemporary discourses of green political economy: A Q method analysis. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(5), 533–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1118681

- Stirling, A. (2006). Precaution, foresight and sustainability: Reflection and reflexivity in the governance of technology. In Voß et al (Ed.), Reflexive governance for sustainable development (pp. 225–272). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Sutton, M. (2017). Discourses of the Alberta oil sands: What key stakeholders really think about sustainability. Consilience, 18(2), 175–192.

- Swedeen, P. (2006). Post-normal science in practice: A Q study of the potential for sustainable forestry in Washington state, USA. Ecological Economics, 57(2), 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.04.003

- Vries, B. J., & Petersen, A. C. (2009). Conceptualizing sustainable development. Ecological Economics, 68(4), 1006–1019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.11.015

- Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2005). Doing Q methodology: Theory, method and interpretation. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2(1), 67–91. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088705qp022oa

- Webler, T., Danielson, S., & Tuler, S. (2009). Using Q method to reveal social perspectives in environmental research. Social and Environmental Research Institute.

- Zabala, A., Sandbrook, C., & Mukherjee, N. (2018). When and how to use Q methodology to understand perspectives in conservation research. Conservation Biology, 32(5), 1185–1194. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13123