ABSTRACT

This paper examines the implementation of the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015, the first and only piece of legislation to codify the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals in law. The paper provides empirical analysis of the implementation of this legislation based on 16 semi-structured interviews with stakeholders across Wales. The analysis explores whether the Act can deliver spatial justice in Wales through its novel and place-based approach to sustainable development. We examine how the Act has been implemented at different spatial scales – the local, the regional and the national – and how the differences in the way it is interpreted by actors at these different levels influences the extent to which spatial justice is realised in its implementation.

Introduction

The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 represents a world first in sustainable development legislation as Wales remains the only country to codify the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals in law (Wallace, Citation2019). This legislation, referred to here as ‘the Act’, places a duty on public bodies in Wales to ‘think more about the long-term, work better with people and communities and each other, look to prevent problems and take a more joined-up approach’ (Welsh Government, Citation2021, p. 2). The Act sets out a place-based approach to sustainable development that is grounded in local definitions and understandings of well-being yet is accompanied by little guidance for its implementation.

Based on analysis of semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders in Wales, this research examines whether the Act, as a novel place-based approach to sustainable development legislation and governance, can deliver development that is aligned with the ideals of spatial justice – i.e. ‘the fair and equitable distribution in space of socially valued resources and opportunities to use them’ (Soja, Citation2009, p. 2). Although the Act embodies an approach to sustainable development that is theoretically compatible with spatial justice, it is not clear from existing evidence that this potential is being realised in its implementation. As the Act is grounded in distinctly Welsh and local understandings of well-being, we examine how the Act has been implemented at different spatial scales – the local, the regional and the national – and whether any differences in the way it is interpreted by actors at these different levels influences the extent to which spatial justice is realised in its implementation.

In doing so, the paper makes three contributions. First, it provides a theoretical contribution through the development of an empirical case study of the Act as a spatial justice approach to sustainable development legislation and practice at different levels of governance. Second, it provides an empirical contribution examining how the Act is being implemented. This has received limited academic attention (Nesom & MacKillop, Citation2021) as most material is grey literature (Davidson, Citation2020; Wales Audit Office, Citation2019a; Welsh Parliament, Citation2021). Third, it provides a critical analysis of the implementation of place-based sustainable development policy at different, often interconnected, geographical scales.

We begin with a short overview of the Act and its institutional context. This is followed by a review of relevant literature on the Act and spatial justice. The third section outlines the research method. The fourth section examines the implementation of the Act, focusing on four aspects: place, resources, ambiguity, and partnerships. The final section reflects on these findings.

The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015: place-based sustainable development

The Government of Wales Act 1998, which provides the legal basis for devolution and the Welsh parliament, includes a duty to promote sustainable development (Stevenson & Richardson, Citation2003). The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act, passed in 2015, is the fourth in a series of sustainable development strategies instituted by the Welsh Government (Nesom & MacKillop, Citation2021).

The Act uses a broad definition of well-being which is, in essence, synonymous with sustainable development but allows for a range of interpretations. It is articulated in the Act’s Sustainable Development Principle which defines sustainable development as working ‘to ensure that the needs of the present are met without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Welsh Assembly Government, Citation2015, pp. Part 2, Section 5). The Act requires all public bodies in Wales to adhere to this principle.

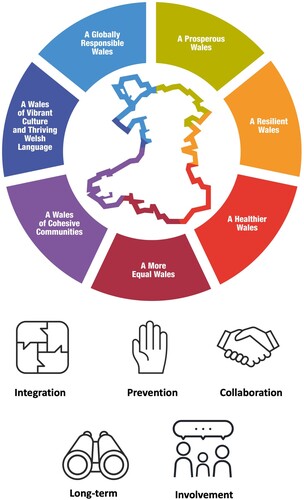

The Act outlines four pillars of sustainable development – social, economic, environmental and cultural. These pillars inform seven well-being goals, with 50 associated national indicators of progress, which public bodies work towards through five ways of working set out in the Act (See ) (Welsh Government, Citation2022).

Figure 1. The seven well-being goals and five ways of working.

Sources: Welsh Government (Citation2021).

The implementation of the Act is, in practice, informed by local understandings of well-being, which makes the Act primarily aspirational and focused on long-term goals at the national level (Davies, Citation2016; Nesom & MacKillop, Citation2021; Welsh Parliament, Citation2021). Beyond this broad framework, the Act itself is vague and Welsh Government has provided little by way of concrete measures or guidance for implementation at the organisational and local levels (Nesom & MacKillop, Citation2021; Wales Audit Office, Citation2019b). While a degree of vagueness around the specifics of implementation is to be expected in sustainable development legislation and can support implementation by allowing flexibility in local approaches (Bednar et al., Citation2019), stakeholders in Wales have struggled to balance the tension created by the lack of implementation guidance for the local level, on one hand, and scrutiny of its implementation from the Future Generations Commissioners Office (FGCO) on the other (Nesom & MacKillop, Citation2021). The language of the Act is sometimes seen as confusing, with key concepts such as ‘well-being’ and ‘prevention’ not having clear definitions nor there being consistency with other statutory legislation in force in Wales. For some stakeholders it is not clear how Public Service Boards are meant to work with other institutional set-ups in the Welsh landscape, such as Regional Partnership Boards, with local actors asking ‘who oversees who?’. Finally, local actors have reported being unsure how to align well-being principles with their own policies and frameworks (Wales Audit Office, Citation2019b).

One of the few concrete measures accompanying the Act was the establishment of a new type of regional body – Public Services Boards (PSBs) – through which public organisations in Wales work collaboratively towards the goals of the Act. It is through PSBs and public bodies in Wales that the Act is delivered. The PSBs are required to ‘improve the economic, social, environmental and cultural well-being of [their] area by contributing to the achievement of the well-being goals’ (Welsh Assembly Government, Citation2015, pp. Part 4, Section 36). They produce well-being plans, informed by local consultations, setting out goals for their area which in turn contribute to progress towards the seven national goals. The Act emphasises the centrality of PSBs which ‘are promoted by the Welsh Government as the key body collectively responsible for improving the wellbeing of communities across Wales’ (Wales Audit Office, Citation2019b, p. 5). It is at the level of the PSB that local definitions of well-being are developed and operationalised within the framework set out by the Act.

Each PSB has four statutory members – the Local Authority, the Local Health Board, the relevant Fire and Rescue Authority and Natural Resources Wales – and several invited partners (e.g. Welsh Government, local third sector organisations) who perform activities relevant to the well-being objectives of the PSB. Public bodies also mobilise understandings of well-being relevant to their individual geographies of operation to drive progress towards the national well-being goals (Wallace, Citation2019). The Act also introduced a Future Generations Commissioner (FGC) who serves as the legal sustainable development representative in Wales and is responsible for monitoring the actions of the PSBs and other public bodies in Wales (Göpel, Citation2012; Linehan & Lawrence, Citation2021; Nesom & MacKillop, Citation2021; Teschner, Citation2013).

The Act is mobilised within the Welsh policy community as a distinctly Welsh and place-based legislation. Here ‘place’ is understood as a ‘meaningful site’ (Cresswell, Citation2009, p. 169) with both a physical location and a clear ‘sense of place’ (p. 169), i.e. a location with a recognisable identity (and generally a recognisable community) which evokes specific meanings and feelings. For the Act, Wales is the overall ‘place’ in which the legislation is grounded while its implementation is informed by the local/sub-national ‘places’ represented by the PSBs and the wider regions of Wales. Since devolution, Welsh sustainable development policy has been increasingly ‘connected to a more loaded language associated with national identities, cultures and values’ (Jones & Ross, Citation2016, p. 57) that seeks to foreground a distinct sense of Welshness in its approach. In this way the Act epitomises the place-based approach to sustainable development that has been emerging in Wales over the last three decades.

Examination of its legislative context demonstrates that the Act embodies a fundamental tension. While the Act is subject to a distinct institutional framework including the FGC, PSBs and well-being goals, the lack of tangible guidance for implementation creates confusion for local actors. Although this hinders the implementation of the Act, the limited guidance provided at the national level is a key part of the Act reflecting its place-based approach. It is this fundamental tension of the Act that leads to the issues of vagueness and problems in implementation (Nesom & MacKillop, Citation2021).

There has been limited empirical academic attention paid to the implementation of the Act. Much of this literature attends to the development of the Act and/or its particularities as novel sustainable development legislation from a legal perspective (Davies, Citation2016; Davies, Citation2017; Messham & Sheard, Citation2020; Wallace, Citation2019). Jones (Citation2019; Jones et al., Citation2020) have considered the Act as a shift from a territorial cohesion approach to sustainable development to one that can be seen to adopt the values of spatial justice and Nesom and MacKillop (Citation2021) have examined the local implementation of the Act as sustainable development legislation. This paper builds on this work by undertaking an explicit examination of implementation at different levels and to examine the interrelationships or lack thereof between these scales that facilitate or impede implementation and progress towards spatial justice in Wales.

A spatial approach to analysing the Act

In this research, we develop a spatial justice approach to understand the implementation of the Act. Spatial justice grounds social justice in spatial contexts and in doing so interrogates the relationship between justice and space (Rocco, Citation2021). Social justice is defined in terms of equitable distribution of resources, opportunities, access and privileges within a society (Harvey, Citation2010). Spatial justice approaches thus require ‘an intentional and focused emphasis on the spatial or geographical aspects of justice and injustice’ (Soja, Citation2010, p. 4). However, spatial justice should not be seen as ‘shorthand for social justice in space’ (Dabinett, Citation2011, p. 1) as some definitions of the concept might misleadingly suggest (Soja, Citation1989). Instead, spatial justice invites an interrogation of the relationship between space and justice as a means of understanding how space can produce and influence social justice as well as how this is experienced across different spaces (Pirie, Citation1983). Existing scholarship on spatial justice is diverse and takes numerous theoretical foci (Weck et al., Citation2022). Much of this scholarship is concerned with decision-making power and process. Papers often focus on how equitably the resources behind decision-making are distributed across space and how fair decision-making processes themselves are (Madanipour et al., Citation2022; Reynolds & Shelley, Citation1985; Weck et al., Citation2022).

In the sustainable development literature spatial justice is often discussed in reference to the territorial cohesion favoured by EU development policy, generally as a complementary pursuit which can support, and should ultimately be, the end goal of redistributive territorial cohesion-based approaches (Weck et al., Citation2022).

The adoption of a spatial justice focus in this study emerged through our review of the work of Jones (Citation2019; Jones et al., Citation2020) and is defined here according to the criteria set out in , adapted from Soja (Citation2009).

Table 1. Key features of spatial justice (adapted from Soja, Citation2009, pp. 2–3).

In the context of the Act, spatial justice is realised when areas are empowered to define well-being and development in ways that are meaningful locally and reflect local priorities, and are able to ‘assert their own capacity to act’ (Jones et al., Citation2020, p. 894) in operationalising these locally informed conceptualisations of well-being and (sustainable) development.

As such, the Act can be seen to represent a spatial justice approach to sustainable development in theory through its focus on a uniquely Welsh understanding of well-being and its emphasis on place-based understandings and actions in promoting well-being and sustainable development. Notably, the Act aligns with the notion of political (re)organisation to foreground local capacity and processes of self-definition that are central to spatial justice. For instance, through its requirement that PSBs conduct well-being assessments in their area and use these to develop well-being plans setting out actions to be taken to meet the targets set out both in the plan itself and the national goals attached to the Act. Here the vagueness of the Act and its implementation guidance could be seen to support the pursuit of spatial justice in its implementation at the local level.

While the Act sets out an approach to sustainable development that aligns with and promotes spatial justice, it is not clear that this spatial justice potential is being realised in practice (Nesom & MacKillop, Citation2021; Wales Audit Office, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Welsh Parliament, Citation2021). Our paper seeks to examine whether the Act is realising its theoretical spatial justice potential. Using spatial justice as a lens, we seek to examine and untangle the complex interrelationships that influence the Act’s implementation across Wales. We identify where and how realising the spatial justice potential of the Act could help to resolve implementation challenges and likewise how improving implementation leads to greater realisation of spatial justice. We seek to understand how the Act is interpreted and mobilised and interrogate the transformative power and/or potential of the Act at different scales and in different contexts. More broadly, we seek to demonstrate how a spatial justice approach can enrich our understanding of sustainable development policy and its implementation by identifying how sustainable development policy and practice is understood and approached differently at different geographical scales of governance.

Research method

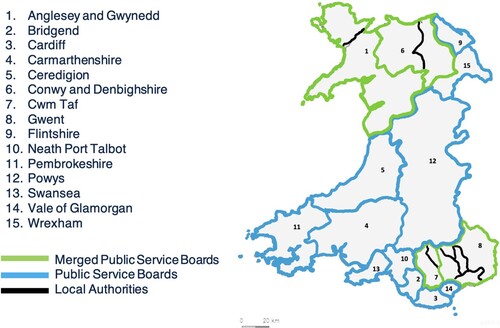

Data was collected via semi-structured interviews lasting around one hour, conducted between December 2020 and August 2021. A total of 16 interviews were conducted to collect stakeholders’ views, interpretations and narratives of the Act and its implementation. All interviews were completed via video call due to the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic. The interviews were recorded, fully transcribed and anonymised with codes randomly allocated to interviewees based on the geographical level of their organisation. In this study, PSBs are viewed as local organisations as they tend to correspond to local authority areas (). Combined PSBs (where PSB areas have chosen to merge across local authority boundaries into one larger organisation in order to better respond to the statutory duty), of which there are four in Wales, are categorised as regional organisations.

This project adopts an iterative approach, which ‘involves moving back and forth between concrete bits of data and abstract concepts, between inductive and deductive reasoning, between description and interpretation’ (Merriam, Citation1998, p. 178). The data collected from the interviews was coded with NVivo12. We utilised a five-stage inductive approach (detailed in below), which was repeated several times to allow themes to develop iteratively (Kekeya, Citation2016).

Table 2. The five-step inductive approach for the research project.

Interviewees

Interviewees were selected from a range of the 44 public bodies subject to the statutory duty of the Act as well as from PSB membership.

Following documentary analysis of the 2017 PSB well-being plans, four case study PSBs were selected, each with different levels of detail in their well-being plans. PSBs were selected from different geographical areas of Wales to reflect the socio-economic diversity of the country. An interview was conducted with a representative of each case study PSB, totalling four interviews. Another 12 interviews were conducted with representatives of public bodies in Wales ranging from local organisations to national bodies named in the statutory duty. Some of these interviewees were also PSB members and so were interviewed in both capacities. Much of the existing (grey) literature focuses on implementation of the Act at the PSB level, with little attention paid to public bodies (Wales Audit Office, Citation2019b). In skewing the interview sample towards public bodies, this project seeks to address this gap whilst also giving voice to the experiences of PSBs.

Results

This section examines the implementation of the Act, focusing on four themes emerging from the data: place, resources, ambiguity, and partnership working.

Place

Many interviewees agreed that the Act caused them to think differently about sustainable development and well-being, and to define these concepts in terms rooted in place.

For most, the point of the Act;

is that you, as an individual body, you as an individual person, thinks about wellbeing and thinks about, “ … What does working towards [all the goals] mean for me?” … it needs to be an individual thought process as a person and as a body. [N1]

join-up between well-being of people and place, … For me, that’s what the Act is all about. It doesn’t prescribe scales or whatever, so that could be right down to very specific geographical areas, or it could be the whole of Wales. [L1]

Specifically, the vagueness of the Act in not providing clear parameters for implementation limits the ability of local and regional actors to fully operationalise local understandings of well-being in their implementation. As a result, many actors felt that their role and remit within the wider governance landscape was not always clear and that they were working to a ‘moving target [R2]’ as related to the expectations of both the FGCO and Welsh Government.

While the place-based nature of the Act is often discussed as one of the strengths of the legislation – it is uniquely Welsh and so is driven by a logic of sustainable development that meets the needs of people in Wales – interviewees highlighted the limits of the Act as a place-based approach to development. The primary limiting factor identified, which applied to organisations at all levels, was that some of the most important issues impacting the well-being of people in a given area of Wales (e.g. PSB area, local authority, health board etc.) are national and/or international issues, such as climate change or migration, that they can neither define clearly nor influence sufficiently at their respective scale of governance which constrains their ability to meet their goals and leads to frustration [R3,L6,L2,L3,N3,R5]. This issue was exacerbated for several participants by the interplay of this issue of cross-boundary problems and the rigid boundaries that actors bring to the table based on institutional legacies and ingrained ways of working. As one interviewee from a regional organisation noted:

The boundaries – administrative boundaries – just don't really make sense to us in lots of ways. I guess we see that every day, whereas if you work in a local authority, of course, you don't see that, because that is what your boundary is … but people don’t often stop to think, “That line on the map in this instance just absolutely doesn't make sense, because there’s exactly the same issue in that valley over there and it's only five miles away”. [R1]

Local actors were particularly frustrated by inconsistency in goals between neighbouring regions/local areas with many feeling that this was a product of the ambiguity of the Act and lack of guidance [L1,L4,L5,L6,R1,R3]. The lack of guidance and co-ordination led to a failure to capitalise on possible synergies due to lack of cooperation between PSBs in different areas of Wales limiting the overall impact that participants felt able to attribute to the Act. Interviewees at all levels identified politics as a key issue that resulted in criticism of the place-based approach as they felt that many of the challenges they faced were due to overlapping power structures muddying the governance landscape and preventing decisive action on ‘thorny’ and ‘big’ (i.e. national and international level) issues which cannot be ‘tackle[d] on a narrow footprint or narrow band, like a local authority’ [R2].

Relatedly, interviewees from organisations at all levels and parts of Wales were critical of the foundation of the Act as a place-based approach to sustainable development as they did not feel that the Act reflects the reality of people’s lives, which ‘are not governed by county boundaries, by any shape’[L6]. Interviewees from areas near the England-Wales border were particularly critical of this aspect of the Act, with two going so far as to say that the main ‘conflict with the Future Generations Act, is that we follow the lifestyle of individuals, we’ve got to accept that not everything will be Wales-centric’ [L6]. These interviewees [L6,L4,L5] described how the cross-border mobility of many people in their area renders well-being planning – which assumes that people live, work and consume key services in Wales – unrealistic. This reinforced the notion that the spirit of the Act and its focus on place requires a widening of the public administration and governance sphere that, for many, is simply not possible within the current infrastructure and governance arrangements in Wales. This limits the impact of the Act in generating the changes in processes and power structures required to achieve meaningful spatial justice in Wales despite its potential. Furthermore, ongoing tension around the appropriate scale at which processes of thinking and working around the Act can or should be taking place speaks to a broader question about the appropriate scale at which spatial justice and sustainable development should be implemented and operationalised. Identification of appropriate sites of intervention is a key feature of spatial justice. Thus, the challenges of implementing the Act at any one set scale seem to suggest that multi-scalar and/or issue-focused networked implementation of spatial justice and sustainable development which spans the local, regional, and national (perhaps even global) scales may help to resolve implementation issues and as such further spatial justice and sustainable development in Wales.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to most of the interviewees participating in projects that were successful in overcoming this issue of muddy governance landscapes as time pressure had forced organisations to work creatively and collaboratively within and between areas to tackle the crises caused by the pandemic [R1,L1,R2,L2,L4,N2,N3,R5]. The success of interventions necessitated by COVID-19 demonstrated that the Act was hampered by its own requirements (e.g. well-being plans and assessments) which take time and resources away from collaborative working on ‘thorny’ issues. Though when questioned most interviewees did feel that the Act and the forum created through the PSBs is an important factor in supporting the response seen during the pandemic. The PSBs were seen as fostering relationships between key actors in each area, and in some cases between areas where national and regional actors are involved and engaged in local activities. Here again, the Act was seen to demonstrate the potential to bring about meaningful change in the Welsh governance landscape that could contribute towards spatial justice – however this only occurred under exceptional circumstances wherein many of the usual complexities of the governance landscape could be bypassed.

Our research tallies with that of those who concluded that the Act embodies a spatial justice approach to sustainable development in theory as the ways in which interviewees described the Act confirms that it foregrounds conceptualisations of well-being that are rooted in place and that these conceptualisations shape local governance (Jones et al., Citation2020). However, our evidence challenges the view that this approach is taking place in practice as the implementation issues outlined above prevent public bodies in Wales from generating the change needed to fully realise the spatial justice potential of the Act. The implementation issues the Act faces regarding its conscious basis in place highlight the inherent tensions in applying spatial justice to real places and can further be seen to confirm that perfect spatial justice is an unachievable ideal due to the unavoidable tensions present when applying such ideals in practice.

Resource issues

Three key themes emerged from discussion around resources – a lack of funding, funding mechanisms, and funding timeframes.

Nine interviewees described the lack of funding as a barrier to implementation of the Act [R1,L1,R2,R3,L6,L3,L4,R4,N2,R5,R6] (similarly to findings in Nesom & MacKillop, Citation2021). Several of these interviewees caveated this by emphasising that having funding would not resolve all issues around the Act’s implementation. As one interviewee noted:

actually trying to change the operating model so that it’s not all about funding and is more about the ethos of the Act is really important, but I think it was interesting it didn’t appear to come with anything upfront to move people towards doing stuff. [R3]

Funding mechanisms were highlighted by most participants as creating or exacerbating resource issues. A number of participants noted that silo-ing of funding in line with Welsh Government portfolios and mechanisms for UK government funding of public bodies does not relate to ‘real world’ operation for interviewees’ organisations. This centring of power relating to funding structures within the control of national actors and the consequent tension of this with local and regional interests can be seen to undermine the possibility of Wales achieving the locational equality, redistributive justice and equitable political organisation that are key features of spatial justice.

Interviewees also highlighted ‘red tape’ in accessing funding and mismatching between actors and funding access as key issues [R3,L6,R6,L5,N2]. Several interviewees from local or regional organisations suggested that ‘giving control of financial and resources to those that can influence and affect the biggest change, and being responsible at the same time’ [L3] would be the way that Welsh Government could best improve implementation of the Act [L6,L5,R6,R1,L1]. All but one of the respondents who expressed this sentiment felt that those who could affect the biggest change were local or regional actors with direct knowledge of a given community. This can be seen to align with the importance given to local/regional capability in relation to well-being in the Act and the emphasis on local/individual autonomy of spatial justice more generally (Jones et al., Citation2020: Soja, Citation2010). These funding issues are a further example where the failure of the Act to truly give areas the capacity to govern their own well-being and development (through provision of appropriate funding mechanisms) hampers its ability to facilitate spatial justice in Wales.

Timeframes associated with financial resource allocation were the third issue highlighted by participants. Mismatches between politically driven funding cycles at the national level and resource planning and allocation needs at the local and regional level left organisations unable to plan beyond short-term funding cycles [L2,R4,N3,L6,R1,L3,R3]. Many felt that this tied them to Welsh Government priorities rather than their own well-being goals, shifting focus towards national decision-making processes thus reinforcing traditional core–periphery dynamics in the political organisation of space in Wales and undermining the corresponding local decision-making process and power upon which spatial justice is dependent.

The issues around resource and the implementation of the Act speak to the broader issue of implementation of sustainable development policies where governments create novel policies which require drastic change in mindsets and ways of working but fail in creating the conditions necessary to support the policy to be implemented (Kemp & Rotemans, Citation2005; Meadowcroft, Citation2009). In the case of the Act this can be seen in the issues outlined above regarding siloed working and sending directives to the local level about priorities via funding allocation and so on, which can be seen to be in direct opposition to the stated ethos of the Act and, by extension, the key features of spatial justice.

Ambiguity of the Act

Interviewees felt that there is lack of national guidance on implementation of the Act (and noted that this has been an issue since the early consultation around the Act). This hinders implementation, as actors described frequently experiencing confusion around what the Act does (or does not) require or allow them to do, which limits their ability to assert their own capacity to act in ways that align with their own definition of well-being and their local goals. A number of participants felt that the ambiguity in the Act meant that there was ‘sometimes a lack of a roadmap, really, that we might need’ [N2,R1,L1,L3,L4,N4,R3]. Participants stressed that what they wanted was a ‘roadmap’ and not a ‘rulebook’ for implementation of the Act.

Participants described how the issue of ambiguity is exacerbated by a lack of support from Welsh Government on the one side and the wrong type of support from the Future Generations Commissioners Office (FGCO) on the other. Interviewees often described simply wanting ‘more support from the Welsh Government’ [R5] as many felt they had been left without sufficient guidance in implementing the Act but were then penalised for not meeting Welsh Government and FGCO expectations [R6,L5,R5,L3,R3,R2,L1]. However, participants generally struggled to specify what type of support would be helpful which could speak both to a degree of blame displacement and a broader uncertainty about how to enact such novel legislation.

This issue was particularly acute in relation to the well-being plans as there was a sense that ‘the [FG] commissioner came back and, sort of, marked the plans’ [L5] without providing sufficient guidance while they were being created. This led to resentment for some actors:

I think people didn’t react very well. They didn’t take it well. They just thought, “This is not your role. You should have helped us earlier on, rather than telling us now that we didn’t do it properly. You told us before there’s no proper way of doing it, and then you say that we haven’t done it properly.” [L5]

Views on the FGCO support were divided with some seeing it as inappropriate and a barrier. However, several noted that they found the Commissioner and her team to be a key asset in the implementation of the Act with a number of interviewees suggesting that one of the things that would help to improve implementation for their organisation would be ‘a bigger capacity in the Future Gens [sic] team’ [R3] to provide support and guidance to organisations across Wales [R6,N4]. Interestingly, several participants who were critical of the FGCO as an organisation had positive experiences with and views of individual members of the team and the Commissioner herself [R3,L1,R2,L4,N2]. This suggests that the impact of individuals may be key when working with a place-based approach to sustainable development.

Regional actors felt that they were often ‘caught in the middle’ [R2] of discussions around guidance as they were simultaneously seeking implementation guidance from Welsh Government and the FGCO and were being asked to provide such guidance by organisations under their remit operating at the local level. In contrast, national actors felt that the ambiguity of the Act was beneficial as it gave local and regional actors the freedom to interpret the Act and set a well-being agenda that met their own specific needs. The disparity in local and national level views demonstrates that while at the national level the Act appears to adhere to a spatial justice approach by allowing subnational approach well-being in and on their own terms, at the subnational level ambiguity surrounding national oversight hinders this potential.

Partnership working

Our interviews demonstrated that power imbalances and institutional politics and legacies were a key issue. For organisations trying to engage in partnership working, the Act was not doing enough to allow public bodies to overcome these issues. A PSB member described that it is:

quite hard then, sometimes, to feel that [the PSB] is a truly collaborative table … just by the numbers and the fact that those colleagues – the local authority colleagues – often work with each other all the time, on all kinds of things, not just the PSBs, whereas others of us are coming to the table for that [only the PSB]. So, our relationships are bound to be not as long-established or strong. [L1]

Some participants from local level organisations suggested that the Act and its impact on governance and funding streams is actually having a negative impact on partnership working and local empowerment in Wales. There was a sense among some that they had seen it ‘decline rather than get better’ [R3]. This was attributed to the increased complexity of the governance landscape and competition between actors for recognition and funding [R3,L6]. For many, the abstract and aspirational nature of the Act was perceived as doing little to combat these issues. Several interviewees described feeling that some of the more aspirational elements of the Act are not ‘actually occurring’ [R3] and that changes to the way partners are working together is not ‘coming through the Act’ [L6]. Instead, many of the interviewees questioned whether the Act has brought about more partnership working as ‘there’s a lot of practical work that was going on anyway’ [L4]. This issue was particularly acute at the local level where interviewees often struggled to attribute positive changes in local ways of working around collaboration and co-operation to the Act. As one interviewee stated, ‘I still struggle to see where you can actually put things locally and hang them on the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act, as being the driver that made it happen [L6].’ This can be seen to provide evidence that the Act is a spatial justice legislation in theory but not in practice. Instead, local actors are working in ways mandated at the national level that do not reflect their needs, reinforcing conventional core–periphery power dynamics of governance which inherently limit the realisation of spatial justice.

Trust was a key theme identified from discussion around partnership working (Owen & Videras, Citation2008; Purdue, Citation2001; Selman & Parker, Citation1997). Participants from organisations already working in partnerships described the Act as a positive force in increasing trust among those engaging in partnership working. They suggested that it has brought partner organisations to ‘a place where there is a level of trust that was not there before’ [L3] through an increase in ‘intangible contacts’ [R2] that have facilitated action. However, organisations that are new partners among groups that have well-established relationships described not feeling as trusted or heard as other organisations with long-term relationships and institutional legacies. This was most acute for public bodies joining partnerships where the local authority is a strong, leading member of a PSB as local officials often have established relationships with local actors and recognised ways of working.

Considering the spatiality of the Act, the introduction of new cross-scale spaces for working collaboratively was mostly seen as positive. Several interviewees described how the infrastructure created by the Act, such as the PSBs and well-being plans, has introduced something new into the governance of sustainable development in Wales [N1,L1,L2]. However, most were either not able to demonstrate or did not agree that this has produced new geographies of governance and implementation. For most interviewees, regardless of the geographical level of their organisation, the Act has given new labels to partnerships and geographies of governance that already existed. One example cited by a number of interviewees was the similarity in the groups of actors previously brought together by the Regional Partnership Boards or Local Service Boards and those who are now members of PSBs [L3,R1,N3,L5,L6].

No examples were given in the interviews of the Act generating new ways of linking across scales (i.e. creating networked ways of working for specific issues) despite a small number of interviewees mentioning such an approach as a novel way to tackle the wicked issues of sustainable development in Wales. As one interviewee noted:

the Wellbeing Act is supposed to be transformative, and yet we still stick with the boundaries of local authorities. If it is truly transformative, should there or could there be alternative, almost geographical imaginations that underpin it? [L6]

While local actors were generally more sceptical about the impact of the Act on partnership working and collaboration, a number of national actors and some larger regional actors described the Act as a facilitator of cross-scale working and collaboration between national and local actors at the regional level. They felt that it increased their efficiency and prevented repetition in their work ‘because we find ourselves saying the same things at multiple tables at the moment, so it makes a lot of sense to us … there’s an awful lot to be gleaned by working at the regional scale’ [R2]. Regional actors highlighted the importance of a ‘shared agenda’ of ‘things that we all, or a large number of the partners within the room are a contributor to’ [R1] as a driver of successful collaboration and cross-scale working. This provided ‘shared aspirations and a shared vision for improving wellbeing in the area’ [R1], both in the context of PSB meetings and more widely.

Conclusion

We have examined how the Act has been implemented at different spatial scales – the local, the regional and the national – and how the differences in the way it is interpreted by actors at these different levels influences the extent to which spatial justice is realised in its implementation. The research set out to analyse whether the Act could deliver the ideals of spatial justice, which highlights the transformative potential of national governments adopting novel approaches to governance that allow for locally defined and plural understandings of well-being and sustainable development that in turn result in a more equitable distribution of resources and opportunities. Based on our analysis, the Act seems to embody the values of spatial justice in theory through its emphasis on local understandings of well-being, focus on participatory approaches and lack of top-down prescription. However, we demonstrate that this potential for a transformative approach to national sustainable development policy that embodies plural understandings of well-being and/or sustainable development is not realised in practice.

Issues of resource, ambiguity and partnership working remain central challenges in the implementation of the Act and there are clear differences in understandings and impressions of the Act (i.e. purpose, aims, structure) at the different geographical levels (with these differences potentially part-and-parcel of the Act’s spirit). Local responses to COVID-19 demonstrated that implementation of the Act is often hampered by its requirements (e.g. well-being plans and assessments) which are relatively time- and resource-intensive.

In terms of the spatiality of implementation, our analysis demonstrates that there is a national-local divide in opinions about the Act. Interviewees from large national organisations were the most positive about the Act while those from local organisations were the least positive. This was linked by some to a lack of equality of opportunity for different organisations. Interviewee opinion on the Act related to their relative level of power within their own sphere of influence as related to the Act. Those with the most power in implementing the Act in their ‘arena’ were the most positive, those with the least power were the most frustrated by issues related to its implementation.

The empirical case of the Act provides an opportunity to reflect on the spatial justice concept as relates to sustainable development policy implementation. Four key reflections emerge from our evidence.

First, the Act raises questions about the appropriate scale(s) at which to implement spatial justice and/or sustainable development. Many of the sustainable development issues faced by those implementing the Act do not have clear sites of intervention and as such (hyper) localist conceptualisations of the spatial dimension of spatial justice and place-based sustainable development policy limit the ability of actors to address such issues by limiting them to localised action.

Second, the Act highlights the inherent tensions of applying such an idealistic concept as spatial justice to real world places which are subject to ‘muddy’ governance landscapes and embedded power structures which often cannot be easily altered to ensure justice in both process and outcome. The Act demonstrates potential limits to the utility of the spatial justice concept in situations where actors must contend with the added complexities and potential for locational discrimination in the political organisation of space present in the context of devolution as well as local governance. This is seen in the issues of funding which surround implementation of the Act as local actors are bound by the funding decisions of Welsh Government who are in turn constrained by the overarching power of UK Government thereby limiting the potential for realising redistributive justice and locational equality – key features of spatial justice (see ) – through the Act.

Third, the implementation of the Act highlights that the type of process change required by spatial justice can only occur if it is a priority and possibility at all levels of governance and is communicated effectively between these levels. Our evidence shows that while there is an appetite for translating the change in thinking produced by the Act into a new way of doing sustainable development in Wales, the ambiguity of the Act and the lack of guidance related to its implementation is a major factor in preventing potential transformation being realised. The Act also highlights the potential pitfalls of (hyper)localist conceptualisations of spatial justice in emphasising the local at the cost of dialogue between scales. Interviewees were often unable to envisage alternative governance arrangements outside either traditional top-down approaches or the type of localism represented by the Act. This, coupled with ongoing frustrations around guidance and evidence of blame displacement between local and national actors, suggest that the localist focus on the Act has led to a stalling in productive dialogue between actors at different spatial scales which, if present, could lead to creative alternative geographies of sustainable development governance in Wales.

Finally, examining the implementation of the Act through the lens of spatial justice demonstrates that perfect (spatial) justice is, indeed likely to be an unachievable ideal (Soja, Citation2009). However, the case of the Act also reinforces that, as perfection is not achievable, identification of the most relevant sites of possible intervention is vital to any effort seeking to achieve spatial justice. The ambiguity of the Act and lack of guidance in its implementation has led to its potential as a catalyst of such targeted intervention thus far being under-realised thereby limiting its contribution to spatial justice in Wales.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this project was obtained from CARBS Research Ethics Committee at Cardiff University.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Richard Cowell and James Downe at Cardiff University for their insightful comments and suggestions on this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Isabelle Carter

Isabelle Carter is a PhD student in the Methodology Department at the London School of Economics, where she is studying demographic transitions. Before this, she was the research apprentice at the Wales Centre for Public Policy, working on a variety of policy areas, including social justice, decarbonisation and the governance of the Well-Being of Future Generations Act.

Eleanor MacKillop

Eleanor MacKillop is a research associate with a background in political science, organisation studies and local government research. Her work at the Wales Centre for Public Policy involves researching the role of evidence in policy-making in Wales and elsewhere, examining policy-making in devolved administrations and small countries, and evaluating the Well-Being of Future Generations Act recently adopted in Wales.

References

- Bednar, D., Henstra, D., & McBean, G. (2019). The governance of climate change adaptation: Are networks to blame for the implementation deficit? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(6), 702–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1670050

- Cresswell, T. (2009). Place. In R. Kitchin & N. Thrift (Eds.), International encyclopaedia of human geography (1st ed., pp. 169–177). Elsevier.

- Dabinett, G. (2011). Promoting territorial cohesion and understandings of spatial justice. Paper presented at the DG Regio, Regional Studies and Slovenia Government Office for local self-government and regional policy conference.

- Davidson, J. (2020). #futuregen: Lessons from a small country (1st ed.). Chelsea Green.

- Davies, H. (2016). The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) act 2015: Duties or aspirations? Environmental Law Review, 18(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461452916631889

- Davies, H. (2017). The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015—A step change in the legal protection of the interests of future generations? Journal of Environmental Law, 29(1), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqx003

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Future Generations Comissioner for Wales. (2017a). Advice from the future generations commissioner to Pembrokeshire PSB. Office of the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales.

- Future Generations Commissioner for Wales. (2017b). Advice from the future generations commissioner for Wales to Flintshire PSB. Office of the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales.

- Göpel, M. (2012). Ombudspersons for future generations as sustainability implementation units. Stakeholder Forum for a Sustainable Future.

- Harvey, D. (2010). Social justice and the city (1st ed.). University of Georgia Press.

- Jones, R. (2019). Governing the future and the search for spatial justice: Wales’ Well-being of Future Generations Act. Fennia - International Journal of Geography, 197(1), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.11143/fennia.77781

- Jones, R., Goodwin-Hawkins, B., & Woods, M. (2020). From territorial cohesion to regional spatial justice: The well-being of future generations act in Wales. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(5), 894–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12909

- Jones, R., & Ross, A. (2016). National sustainabilities. Political Geography, 51, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.12.002

- Kekeya, J. (2016). Analysing qualitative data using an iterative process. Divine Word University.

- Kemp, R., & Rotemans, J. (2005). The management of the co-evolution of technical, environmental and social systems. In K. M. Weber & J. Hemmelskamp (Eds.), Towards environmental innovation systems (pp. 33–55). Springer.

- Linehan, J., & Lawrence, P. (2021). Giving future generations a voice: Normative frameworks, institutions and practice (1st ed.). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Madanipour, A., Shucksmith, M., & Brooks, E. (2022). The concept of spatial justice and the European Union’s territorial cohesion. European Planning Studies, 30(5), 807–824. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1928040

- Meadowcroft, J. (2009). What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long term energy transitions. Policy Sciences, 42(4), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-009-9097-z

- Merriam, S. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education (1st ed.). Jossy-Bass.

- Messham, E., & Sheard, S. (2020). Taking the long view: The development of the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) act. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18(1), Article 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-0534-y

- Nesom, S., & MacKillop, E. (2021). What matters in the implementation of sustainable development policies? Findings from the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act, 2015. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 23(4), 432–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1858768

- Owen, A., & Videras, J. (2008). Trust, cooperation, and implementation of sustainability programs: The case of Local Agenda 21. Ecological Economics, 68(1-2), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.03.006

- Pirie, G. (1983). On spatial justice. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 15(4), 465–473. https://doi.org/10.1068/a150465

- Purdue, D. (2001). Neighbourhood governance: Leadership, trust and social capital. Urban Studies, 38(12), 2211–2224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980120087135

- Reynolds, D., & Shelley, F. (1985). Procedural justice and local democracy. Political Geography Quarterly, 4(4), 267–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-9827(85)90035-7

- Rocco, R. (2021). What’s spatial justice? Retrieved April 12, 2023, from https://spatialjustice.blog/

- Sarantakos, S. (2005). Social research (3rd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Selman, P., & Parker, J. (1997). Citizenship, civicness and social capital in local agenda 21. The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 2(2), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839708725522

- Soja, E. (1989). Postmodern geographies: The reassertion of space in social life (1st ed.). Verso.

- Soja, E. (2009, September). The city and spatial justice. Justice Spatiale | Spatial Justice, 1–5.

- Soja, E. (2010). Seeking spatial justice (1st ed.). University of Minnesota Press.

- Stevenson, R., & Richardson, T. (2003). Policy integration for sustainable development: Exploring barriers to renewable energy development in post-devolution Wales. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 5(1), 95–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080305608

- Teschner, N. (2013). Official bodies that deal with the needs of future generations and sustainable development-comparative review. The Knesset Research and Information Center.

- Thomas, D. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

- Wales Audit Office. (2019a). Implementing the Well-being of Future Generations Act - Welsh Government.

- Wales Audit Office. (2019b). Review of public services boards.

- Wallace, J. (2019). Wales: Wellbeing as sustainable development. In I. Bache & K. A. P. Scott (Eds.), Wellbeing and devolution. Wellbeing in politics and policy (pp. 73–101). Palgrave Pivot.

- Weck, S., Madanipour, A., & Schmitt, P. (2022). Place-based development and spatial justice. European Planning Studies, 30(5), 791–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1928038

- Welsh Assembly Government (2015). Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015.

- Welsh Government. (2021). Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015: The essentials. https://gov.wales/well-being-future-generations-act-essentials-html#section-60672

- Welsh Government. (2022). Wellbeing of Wales: National indicators. https://www.gov.wales/wellbeing-wales-national-indicators

- Welsh Parliament Public Accounts Committee. (2021). Delivering for future generations: The story so far.