ABSTRACT

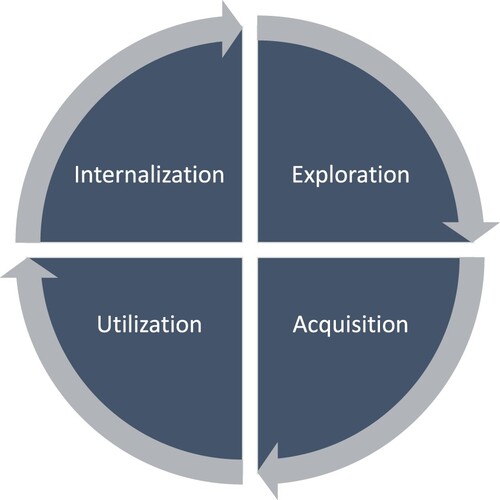

Cities learning from or with each other – or city to city learning (C2C) – is the focus of analysis for this systematic literature review. This research paper sought to understand C2C learning by examining conceptual, methodological, and empirical evidence. Conceptually, this research paper found few definitions of C2C learning. By formulating a definition as well as building a process-and-outcome model, which integrates different phases, mechanisms, conditions, and effects, this research paper contributes to furthering the conceptual debate and clarity on C2C learning. C2C learning is defined here as a dynamic yet sequential mutual process participated in by cities and their representatives which starts with exploration, followed by acquisition, utilization, and internalization. Each phase is activated by specific mechanisms and can be influenced by different conditions that can lead to multiplicity of outcomes. For future research, more diverse methodologies, such as the use of non-qualitative and longitudinal studies, are suggested. Lastly, further empirical analysis, which can make use of the proposed C2C learning process-and-outcome model, is recommended. Overall, it is important to further investigate the link(s) between the (wider patterns of) learning processes, the conditions under which C2C learning works, and (the multiplicity of) outcomes across different contexts.

1. Introduction

CitiesFootnote1 within and across national borders are learning with and from each other on a wide range of topics for different purposes and in varying ways (Haupt, Citation2021; Haupt et al., Citation2020; Ilgen et al., Citation2019; Moodley, Citation2019, Citation2020; Ndebele-Murisa et al., Citation2020). With complex challenges, such as climate change and more recently, the Covid 19 pandemic, cities and their representatives, for example, elected officials, bureaucrats, civil servants, and political parties are motivated by varying drivers. Further, C2C learning opportunities are increasingly provided by transnational networks (Keiner and Kim Citation2007; Lee & Jung, Citation2018). Hence, the growing phenomenon of city-to-city or C2C learning which has been recognized as a process of mutual learning. However, there is still much to learn about learning between and among cities.

Learning, in general, has been referred to as the updating of knowledge and beliefs through social interaction among policy actors, through lived personal-organizational experience, or via analysis based on new or different evidence – or through the combination of the three (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2013, Citation2018).Footnote2 In C2C learning, responding to definitional issues i.e. how is it defined and the need for clear operationalization, that is, how is it measured remain. Further, understanding the contexts in which C2C learning occurs, how these processes unfold and what conditions facilitate or hamper these, and what outcomes do this lead to need further examination. A systematic conceptual, methodological, and empirical analysis of C2C learning is necessary.

1.1. Rationale

Often linked to policy learning as well as policy transfer, policy mobility, and policy diffusionFootnote3 (Haupt et al., Citation2020), previous studies (e.g. Marsden et al., Citation2011; Marsden & Stead, Citation2011; Shefer, Citation2019) have used and/or modified analytical frameworks developed by Bennett and Howlett (Citation1992) and Dolowitz and Marsh (Citation1996, Citation2000) to understand learning between cities. Key questions asked by researchers include who learns, what is learned, from where, and to what effect, among others. While other authors (Benson & Jordan, Citation2011; James & Lodge, Citation2003) do challenge the assumptions from these frameworks, these can serve as starting points for understanding C2C learning. With that, there is also a need to incorporate other elements in the analysis to make it suitable for C2C learning.

First, in policy learning, the specification of the contexts in which two dimensions are key: actor certification (i.e. how legitimate the involved actors are) and problem tractability (i.e. how uncertain the issue being discussed is) can be examined (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2018). Contextual differences may influence the process and subsequent outcome of C2C learning. Second, how learning unfolds from a process perspective and what mechanisms activate each phase, such as, for example, from a knowledge utilization standpoint (Ettelt et al., Citation2012; Rich, Citation1997) can be undertaken. How does C2C learning develop, and what are its building blocks is pertinent. So is the investigation of the ‘when’ and ‘where’ (Gerlak et al., Citation2018; various authors in Dussauge-Laguna, Citation2012) of learning.

Third, what conditions e.g. individual, interpersonal, or structural (Riche et al., Citation2021) or exogenous (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013), can influence C2C learning can be validated. According to Riche et al. (Citation2021), learning is ‘conditioned to a balanced configuration … where too much of a single condition may be harmful’. Fourth, understanding what does C2C learning lead to – whether desirable or not, and the multiplicity of learning outcomes, can be recognized (Moyson & Scholten, Citation2017). Learning has been connected to policy change (Bennett & Howlett, Citation1992; Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2013), including policy failure or dysfunction (Dunlop, Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

1.2. Objectives

For this systematic literature review, cities learning from or with each other – or C2C learning – was the focus of analysis. This research paper sought to understand C2C learning by examining conceptual, methodological, and empirical evidence. By conceptual evidence, this relates to the definition of C2C learning and learning, including the concept, theory, or framework used, in the reviewed studies. Further, the research objectives related to learning, including the research variables, were examined. In terms of methodological evidence, this refers to research strategies, including methods used for data collection and analyses.

By empirical evidence, this research paper systematically analyzed and compared studies based on four main dimensions: context (actor and problem), process, conditions, and effects. First, the contexts in which city actors – both single and/or multi-actor – engage in C2C learning were identified. Second, the process of how C2C learning unfolds, specifically the phases and mechanisms as well as spatial and temporal dimensions were analyzed. Third, the conditions that can facilitate or hinder C2C learning were explored. Lastly, the outcomes of C2C learning were investigated. Finally, this paper summarized existing knowledge, addressed (some of the) gaps discovered, and outlined future research agenda on C2C learning.

2. Methods

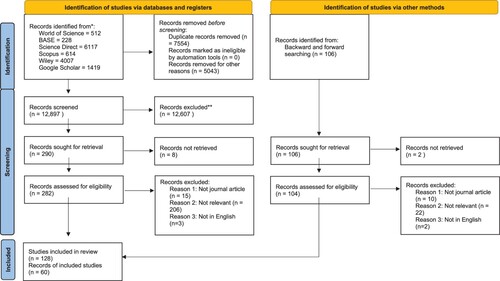

For this review, the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which include searches of databases, registers, and other sources (Page et al., Citation2021) has been applied. This was undertaken to critically evaluate existing academic literature on C2C learning. The review was conducted using PRISMA guidelines (See : PRISMA 2020 Flow diagram). The review utilized five (5) principal resources for systematic reviews, namely Bielefeld Academic Search Engine or BASE, Science Direct, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, and Wiley (Gusenbauer & Haddaway, Citation2020). Additional records were identified through other sources, primarily through Google Scholar, as well as backward and forward reference searching.

The following keywords were used to identify records: ‘city to city learning’, ‘city to city exchange’, ‘city to city partnership’, ‘city to city cooperation’, ‘intercity partnerships’, ‘intermunicipal partnerships’, ‘trans city learning’, ‘trans municipal learning’, ‘trans local learning’, ‘cross city learning’, ‘intercity learning’, and ‘intermunicipal learning’. Additionally, the combination of the following keywords was used to perform searches: city ‘AND’ ‘learning transfer’, city ‘AND’ ‘knowledge transfer’, city ‘AND’ ‘policy transfer’, and city ‘AND’ ‘policy learning’. The keywords were searched in articles’ title, abstract, and keywords.

The investigation focused on scholarship in the last two decades (1991–2021). The literature review was conducted for a period of six (6) months between April and September 2021, while the qualitative analysis was carried out for a period of three (3) months from November 2021–January 2022.

A total of 12, 897 records were identified through database and register searching, while additional 106 records were identified via other methods. There were two stages to analyze the records. Stage 1 focused on screening, while Stage 2 focused on eligibility. The author screened and analyzed the eligibility of each record. For Stage 1, records were included if they were (1) published in English; (2) available as open access; (3) relevant to C2C learning; and (4) peer-reviewed journal article. Records were excluded if they were books, book chapters, dissertations, theses, reports, and conference papers.

After screening the records based on the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria, full text of the records was analyzed in Stage 2 for eligibility. To assess eligibility, the records should focus on learning between two or more cities and should be based on empirical evidence. In total, 128 studies were reviewed and 60 were included in the qualitative analysis. See Appendix 1 for List of Included Studies. Following the PRISMA protocol, information was extracted based on the objectives of the review. See Appendix 2 for the Coding Source Book Developed. All the relevant data from each record was tabulated and analyzed using Microsoft Excel. The author synthesized data from the selected studies. See Appendix 3 for the List of Tables as well as Appendix 4 for the Complementary Materials.

3. Results

Based on 60 studies reviewed, 48 (80%) were published between 2011 and 2021, while 12 (20%) were published between 2001 and 2010. A total of 44 journals have published those reviewed studies; 5 (8%) were in Habitat International; 4 (7%) in Urban Studies (7%), 3 (5%) in the Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning (5%), and 3 (5%) in Public Administration and Development. The most common keywords used were learning (13 or 5%), policy learning (12 or 4%), policy transfer (10 or 3%), policy mobilities (9 or 3%), transport (7 or 2%), and climate change (7 or 2%). The articles focused on 27 different urban themes with 10 (17%) on climate change; 9 (15%) on city learning in general; 9 (15%) in transport (15%); and 5 (8%) in local governance.

The empirical cases from the studies reviewed were distributed globally: 17 (28%) were of C2C learning within Europe; 7 (12%) were in North America; 4 (7%) were in Asia; 3 (5%) were in Africa; 2 (3%) were in South America; and 1 (2%) was in Australia. Further, 11 (18%) were studies that focused on a mix of different global cities. Other studies focused on different configurations: 4 (7%) were cities between Europe and North America; 4 (7%) were cities between Europe and Africa; 2 (3%) were cities between Europe and South America; and one each (2%) for the following: Africa and South America; North and South America; North America and Australia; Europe and Asia; and Asia and Africa.

3.1. C2C learning: How is it conceptualized and studied?

C2C learning has been explicitly defined in 3 (5%) of the studies. Moodley (Citation2019) defines it as a

a structured, yet flexible process of acquiring new knowledge, willingly shared by skilled, experienced practitioners and their collaborative partners, in an empowering manner, among two or more cities or towns, in order to improve municipal service delivery and good governance.

Learning, however, is more explicitly conceptualized by 20 (33%) of the studies, while 40 (67%) had no indication. See Table 1 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on definitions of learning. Learning has been considered as a process by 8 (13%), as both a process and an outcome by 6 (10%), or as an outcome alone by 3 (5%). In the remainder of the studies, learning has been equated to emulation; been differentiated with emulation; and considered as a capacity by 1 (2%) each, respectively. Emulation is purely imitation without full consideration of costs and benefits, while learning is considered rational or bounded rational, which allows for adaptation to local conditions (Ma, Citation2017). Ilgen et al. (Citation2019), on the other hand, relate learning to capacities e.g. resourcefulness and innovativeness, as well as to practices and relations e.g. experimentation, collaboration, and knowledge sharing.

As a process, learning, which can be driven intentionally either by the learner himself/herself or via support structures (Devers-Kanoglu, Citation2009), has been defined in different ways. First, it has been defined as either acquiring knowledge (Haupt et al., Citation2020) or transferring information (Wolman & Page, Citation2002). Second, it has been defined as sequential. Learning has been referred to as the acquisition of knowledge which is then tested, converted, and used to make change, and stored for future use (Campbell, Citation2009), while it has also been described as a process of information seeking, adoption, and policy change (Lee & van de Meene, Citation2012). Third, learning has been conceptualized as an exchange and co-production of knowledge or as joint knowledge construction (Valkering et al., Citation2013; Wilson & Johnson, Citation2007).

As both a process and an outcome, learning, according to different authors, leads to improved understanding of an issue as well as to alteration or updating of behavior, strategies, thoughts, and beliefs in light of other actor’s experience or as a response to new information (Ansell et al., Citation2017; Johnson & Wilson, Citation2006; Lee, Citation2019; Lundin et al., Citation2015; Montero, Citation2017; Perkins & Nachmany, Citation2019). Lastly, learning, based on the premise of change, is considered just as an outcome as this implies an improved understanding of cause-and-effect relationships in light of experience (Glaser & te Brömmelstroet, Citation2020) and as reflected by a decision to produce better policy outcomes than the previous ones (Takao, Citation2014).

Learning between and among cities is also connected to many different but related concepts. Out of the 60 studies, learning was connected to a concept, theory, or framework in 38 (63%) of the studies, while 22 (37%) had no indication. See Table 2 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on concept, theory, or framework used. Out of the 38 studies, policy transfer has been used by 6 (10%), followed by municipal partnerships, policy learning, peer-to-peer learning, networking/networks, and a combination of policy transfer and policy mobilities. Municipal partnerships, including decentralized cooperation, are results-oriented collaborations that have been recognized as learning contexts (Sonesson & Nordén, Citation2020). Meanwhile, peer-to-peer learning involves experts from a particular field who share their knowledge and skills with their colleagues from another (Van Ewijk et al., Citation2015) Networking/networks serve as platforms for C2C learning (Baldersheim et al., Citation2002; Valkering et al., Citation2013), while policy mobilities emphasize the mobile character of policies – or models – that mutate through trans local circuits, networks and webs (Cook & Ward, Citation2012).

In terms of research objectives, the studies aimed to better understand learning processes (39 or 65%), followed by effect (15 or 25%), while others explored the connection of learning to other concepts or to understand the difference between concepts (6 or 10%). See Table 3 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on research focus and main research objectives. Specifically, of those studies that focused on processes, these include investigating mechanisms and conditions (e.g. Haupt, Chelleri, van Herk, & Zevenbergen, Citation2020; Moodley, Citation2019); learning relationships, including mutuality of the actors involved (e.g. Sheldrick et al., Citation2017; van Ewijk, Citation2012); or to explore the origins or evolution of ideas through learning and related concepts (Bray et al., Citation2011; Kalliomäki, Citation2018; Peck & Theodore, Citation2010). Of those studies that focused on effect, these aimed to understand what contributes to or facilitate learning or to investigate the outcomes and effect(s) of learning (e.g. Farmer & Perl, Citation2020; Ma, Citation2017; Zhang & Wang, Citation2021).

Learning was considered as either a dependent or an independent variable in 11 (22%) of the studies. Of these, 4 (36%) focused on learning as an independent variable that can contribute to either policy diffusion (Ma, Citation2017; Zhang & Wang, Citation2021), transfer (Farmer & Perl, Citation2020), circulation, and adoption (Wood, Citation2014). Meanwhile, 7 (3%) focused on learning as a dependent variable that may be driven by cooperation (Shefer, Citation2019; Van Ewijk et al., Citation2015), exchanges (Ndebele-Murisa et al., Citation2020), and transnational networks, activities, and initiatives (Betsill & Bulkeley, Citation2004; Bradlow, Citation2015; Perkins & Nachmany, Citation2019; Salskov-Iversen, Citation2006). In terms of research strategies, 41 (68%) of the studies were qualitative; 8 (13%) were quantitative; and 4 (7%) were mixed method. There were 7 (12%) studies that had no indication about the research strategy employed. See Table 4 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on research strategy.

3.2. Contexts: What are the contexts for C2C learning?

As the studies had a wide range of focus – so were the type of actors that were explicitly mentioned in 40 (67%) of the studies reviewed. Specifically, there were 21 (35%) studies that involved learning among multiple groups of actors. For example, a mix of public, private, and civil society actors were involved in learning between Berlin/Freiburg, Germany, and Tel Aviv, Israel (Shefer, Citation2019) as well as between Dutch Moroccan and Dutch-Turkish municipalities (Ewijk, Citation2016). On the other hand, 19 (32%) were participated in by singular group of actors e.g. city or municipal officers or officials, including mayors; civil servants; policy makers; and urban planning practitioners. There were 20 (33%) studies that had no indication as to what type of actors were involved. See Table 5 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on type of actors.

In 14 (23%) of the studies, there were roles that city actors have undertaken that indicate the flow of learning. See Table 6 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on the role of actors. These include mentor/teacher and mentee/learner (6 or 10%); host/visited and visiting/tourist (3 or 5%); source/sender and seeker/receiver/recipient (3 or 5%); pioneers/leaders and followers/laggards (1 or 2%); and lighthouse and fellow/follower (1 or 2%). However, several studies (Carolini et al., Citation2018; Haupt et al., Citation2020) have critiqued this division of roles and called for mutual learning exchanges.

In 17 (28%) of the studies, there was explicit focus on actors’ motivations for learning. These include local problems and pressures e.g. strategic need, policy failure, or project collapse; need for publicity and exposure at different levels to raise city profile and gain recognition; opportunity to learn and share knowledge with other cities, including getting inspiration from best practices and receiving review of work from others; available opportunities and incentives, for example, through membership in associations and available funding; and individual factors, for example, accruing reputational capital and taking on a professional challenge. See Table 7 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on learning motivations.

C2C learning objectives also varied across the studies with climate change (10 or 17%) and transport (9 or 15%) as the most common content. Within the climate change domain, 7 (10%) of the studies focused on various topics as learning content. Other learning content under climate change includes specific actions and innovations, for example, cap and trade systems; policy ideas and technical solutions; and legislative, policy, and administrative developments. In the transport sector, there has been focus on specific topics, such as cycling, bus rapid transit system; transport policy innovations; public bicycle programs, and transport strategies. See Table 8 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on learning content.

Facilitating C2C learning is a mix of transnational networks, for example, C40 Cities Climate Change Leadership Group, Cities for Climate Protection Program (13 or 22%), partnership programs e.g. United Nations’ Global Water Operator’s Partnership Alliance, Municipal Partnership Programme (9 or 15%); funded projects, for example, European Commission Horizon 2020 Programme or Interreg (6 or 10%); and finance institutions, for example, World Bank (2 or 3%). Half of the studies (20 or 50%) had no indication regarding the means for C2C learning. See Table 9 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on learning means.

3.3. Process: How does C2C learning unfold?

Of the 60 studies reviewed, 22 (37%) either explicitly or implicitly mentioned the specific phases of the learning process or described how learning unfolds, while 38 (63%) had no indication. Of these, 7 (12%) focused on just one phase – information seeking (e.g. Lee, Citation2019; Marsden et al., Citation2011; Pojani & Stead, Citation2014) or knowledge acquisition (Glaser & te Brömmelstroet, Citation2020). On the other hand, 15 (25%) of the studies have identified multiple phases (e.g. Baldersheim et al., Citation2002; Einstein et al., Citation2019). Of these, several studies have explicitly described processes or proposed frameworks which go beyond the phase of information seeking or knowledge acquisition (Boulanger & Nagorny, Citation2018; Calzada, Citation2020; Ilgen et al., Citation2019; Lee & van de Meene, Citation2012; Moodley, Citation2020). See Table 10 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on the number of learning phases. For more information of the phases analyzed, see Appendix 4: Complementary Materials.

In addition to phases, mechanisms – or how each phase is activated – has been mentioned in 27 (45%) of the studies. See Table 11 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles according to learning mechanisms. Of the studies that have indications for mechanisms, these included external (17 or 49%) and internal (3 or 8%) search for information; involvement of intermediaries (9 or 24%); internal assessment about own context (4 or 11%); foundation building (3 or 8%); and knowledge management (2 or 6%).

Also, 32 or 55% of the studies had specific venues for learning, which were primarily a combination of different methods (13 or 22%) as well as of site visits or study tours (13 or 22%). Funded projects (2 or 3%) as well as mentorship, workshops, webinars, and peer networks (1 or 2% each, respectively) were also mentioned. In terms of temporal dimension, 10 or 17% indicated a short, mid-or long-term duration, while the rest had no indication.

Based on the synthesis of the different learning phases – in combination with mechanisms, the following summarizes how C2C learning unfolds according to the studies reviewed. For more information, see Appendix 4: Complementary Materials.

3.3.1. Exploration: from internal assessment to foundation building

The first phase is exploration which entails internal assessment (e.g. Campbell, Citation2009; Ilgen et al., Citation2019; Lee & van de Meene, Citation2012; Wolman & Page, Citation2002); information seeking (and sharing) (e.g. Lee, Citation2019; Marsden et al., Citation2011, Citation2012; Pojani & Stead, Citation2014); involvement of intermediaries (e.g. Carolini et al., Citation2018; Haupt et al., Citation2020; Takao, Citation2014); and foundation building (e.g. Baldersheim et al., Citation2002; Shefer, Citation2019). Internal assessment, reflection, or analysis about own context, including existing knowledge, resources, strengths, and weaknesses, has been cited as a starting point to identify information needs. Introspection, however, is done not just by cities before seeking or searching information, but also as a mechanism by cities before sharing information with others (Ilgen et al., Citation2019).

Seeking information refers to identifying and accessing information from other sources (Lee & van de Meene, Citation2012). While these focus on the perspective of seekers of information, other studies (e.g. Ilgen et al., Citation2019; Moodley, Citation2020; Ndebele-Murisa et al., Citation2020; Wolman & Page, Citation2002) have also explored the perspective of information sources. Evidence for external and to a lesser extent, internal search for information, has been found. In the studies reviewed, search for information can be formal or informal; systematic or ad hoc; domestic or international; passive or active; and done by individuals and/or via organizations (various authors).

The involvement of learning intermediaries, including networks and networking initiatives, has been identified as a mechanism to identify and access external sources of information. These actors have been recognized to facilitate C2C learning, provide opportunities, and serve as matchmakers, among others. Also, before actual engagement in C2C learning with others, foundation building is considered necessary. City actors explore potential for collaboration and then build a foundation by establishing links (Baldersheim et al., Citation2002) or by signing collaboration agreements (Shefer, Citation2019). With heavy reliance on external brokers, Moodley (Citation2020) refers to this as courtship and acclimatization, while Ilgen et al. (Citation2019) label this as building pipelines, which cover the establishment of broader contacts between relevant actors, developing mutual understanding, creating a shared vision, and securing a long-term commitment.

3.3.2. Acquisition: from processing and assessment to knowledge co-production

Acquiring information and eventually knowledge, or learning in the most general sense, has been identified. Further, processing or distillation of information, or interpreting information based on problem framing (Wolman & Page, Citation2002), such as through deliberation and discussions, has been cited. After processing comes the assessment of information through their quality and relevance (Wolman & Page, Citation2002), such as by in depth examination of solutions. On the other hand, Ndebele-Murisa et al. (Citation2020) looked at this phase through the lens of knowledge co-production. A transdisciplinary knowledge co-production through city exchange visits was facilitated to bring together researchers, decision-makers, and practitioners from different cities in co-defining problems, co-identifying projects, and co-producing solutions.

3.3.3. Knowledge utilization: from adoption to co-creation

The utilization of information and eventually knowledge – or its effect on decisions (Wolman & Page, Citation2002) has been specifically mentioned. In general, utilization refers to the use and uptake of knowledge. In the studies reviewed, this has been expressed in many ways – from adoption or adaptation, translation, recontextualization, replication, application, and action selection via co-creation. First, adoption has been described as ‘discarding or modifying information and knowledge gained from others based on past experience or discussions reflecting problems and aims being pursued (Lee & van de Meene, Citation2012). According to Lee and van de Meene (Citation2012), adoption depends on an individual’s characteristics, needs, and belief systems and is primarily an internal process. Adoption has also been described as adaptation or reconfiguration of interventions to local conditions and circumstances (Calzada, Citation2020; Moodley, Citation2020). In this regard, adoption is also synonymous to adaptation.

A process of translation, according to Ilgen et al. (Citation2019) takes place before adoption. Translation also involves adaptation of a policy to a specific local context and conditions, particularly in the political process, which can then result to concrete changes in the fabric of the city (Ilgen et al., Citation2019). Recontextualization, meanwhile, relates to the potential of fitting an idea from the origin to the destination context (Kalliomaki, 2018). For a good planning idea to travel, it has to have some degree of abstraction and partly deprived of contextual biases (Lieto, Citation2015 in Kalliomaki, 2018). Replication has been mentioned in several studies (e.g. Calzada, Citation2020). However, replication does not always work, considering contextual differences. Application, on the other hand, has been examined through embedding or routinizing knowledge in organizations (Wilson & Johnson, Citation2007). This has been looked at two levels, namely at the level of specific practices and secondly, through wider learning and institutionalization of new practices in local authorities. Lastly, Boulanger and Nagorny (Citation2018) proposed action selection via co-creation wherein municipal actors, through the help of ‘mentors’, select actions in relation to potentialities and weaknesses of the application context.

3.3.4. Internalization: from reflection to evaluation

The reviewed studies have also looked at what happens after knowledge utilization, such as internalization and reflection and supported implementation. Ilgen et al. (Citation2019), for example, relate internalization and reflection to anchoring to local practices and into knowledge pipelines, so that the knowledge learned can be transferred as well to other cities. Supported implementation, on the other hand, reflects the need for taking active leadership role in the transition to policy implementation (Boulanger & Nagorny, Citation2018; Calzada, Citation2020; Moodley, Citation2020). This also relates to what Moodley (Citation2020) labels as ‘after care’, which involves taking ownership, self-monitoring of targets, and having an open and continued communication. Sharing and deployment of information has also been stated which reflects the need to disseminate knowledge (Bontenbal, Citation2013; Carolini et al., Citation2018).

3.4. Conditions: What are the conditions for C2C learning?

Of the studies reviewed, 23 or 38% of the studies had indications on factors that facilitate or constrain learning – albeit on different focal areas. There has been attention toward factors that shape the learning process (Ilgen et al., Citation2019; Moodley, Citation2020); and more specifically, in information seeking (Marsden et al., Citation2012) and in adoption (Ma, Citation2017). Other authors looked at specific characteristics of study visits (Glaser et al., Citation2021) or site conditions (Glaser & te Brömmelstroet, Citation2020) and under what conditions can study visits initiate adoption (Haupt et al., Citation2020). Also, there have been studies that looked at learning relationships (Lee & van de Meene, Citation2012) or under what conditions did learning occur in partnerships (Carolini et al., Citation2018). The obstacles and opportunities for learning within transnational municipal networks and other networks (Haupt et al., 2019; Tan et al., Citation2021) have also been studied. So were the weaknesses and strengths of learning (Shefer, Citation2019) and the barriers and obstacles for learning in general (Bray et al., Citation2011; Marsden et al., Citation2011; Pojani & Stead, Citation2014).

The most commonly mentioned condition was similarity (13 or 19%), followed by resources (6 or 9%), diversity (4 or 6%); trust, time, and organizational culture (3 or 4% each, respectively). Other conditions mentioned by 2 (3%) of the studies were proximity, learning facilitators, learning purpose, learning activities, equality, political capacity, leadership, structural positions, institutional barriers, and power relations. These conditions can be associated with the learning phases.

Similarity and proximity, according to the studies, for example, Lundin et al. (Citation2015), Carolini et al. (Citation2018) are considered influential, especially in information seeking. Similarity can be between professionals, for example, professional language, position, or sector and between cities, for example, geography, culture, or organization. Similarity provides a common ground and can provide a foundation for building trust (Wilson & Johnson, Citation2007). Predominantly, cities also tend to first seek their geographical neighbors (Lundin et al., Citation2015). On the other hand, the recognition or appreciation of difference, or diversity, can be a source of conscious reflection and enhanced knowledge construction (Wilson & Johnson, Citation2007). How interactions are stimulated by learning facilitators, whether or not the process was intended for, and the quality of learning activities carried out also have an influence (Johnson & Wilson, Citation2006; Valkering et al., Citation2013; van Ewijk, Citation2012; Wilson & Johnson, Citation2007).

Organizational culture, which varies over time, can influence the extent of knowledge utilization (Marsden et al., Citation2011). So are political capacity, leadership, structural positions, institutional barriers, and power relations. Meanwhile, there are also conditions that can influence the overall process. Resources, for example, financial and political are very crucial for cities to be able to participate in C2C learning. Trust, meanwhile, does not emerge overnight and is built through continuous collaboration, repeated engagement, as well as communication. Trust is related to time as well and Moodley (Citation2020) recommends setting realistic time frames for learning. See Table 12 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on learning conditions.

3.5. Effects: What is the outcome of C2C learning?

As for outcomes, 25 or 42% had indications related to outcomes. The outcomes from these studies have been examined at different levels: from individual, organizational, and network – or a combination of these. The most common outcomes have been at the level of both individual and organizational levels (9 or 15%), followed by individual and network levels (3 or 5% each, respectively). See Table 13 in Appendix 3 for the distribution of articles based on learning outcomes.

Individual learning outcomes, which include personal and professional improvement, can be through new knowledge acquired, skills learned, or change in practice and behavior (see Butler et al., Citation2019; Pojani & Stead, Citation2014). Organizational learning outcomes include increased level of credibility within municipal administrations, strengthened governance, and concrete policy actions or changes, among others (see Haupt et al., Citation2020). Network learning outcomes, on the other hand, include improved government-civil society interfaces (see Bellinson & Chu, Citation2019; Bradlow, Citation2015; Wood, Citation2014). Individual learning – as a starting point – and its connection to organizational learning has been addressed by some studies. However, there have been difficulties identified in building a learning culture and on sharing or embedding individual learning at the organizational level. Further, organizational changes have not been thoroughly examined due to the duration needed to study the effects.

Other studies also indicated depth of learning, including specific learning outcomes. Shefer (2009) examined the depth of learning and found in the empirical case studies that learning is single loop, which concerns the consequences of specific actions and does not alter underlying values, or double loop, which involves reframing of problems and changes in the knowledge of the organization. In terms of specific learning outcomes, Shefer (Citation2019) mentioned the following: implementation of new knowledge, policy change, governance, meta learning, and scaling C2C learning. Valkering et al. (Citation2013) also found evidence for single-loop, double loop, and relational learning and has associated these with learning at the individual and organizational levels. Mocca (Citation2018) mentioned three policy learning outcomes – which are policy upgrade, policy emulation, and policy innovation. Meanwhile, Bray et al. (Citation2011) identified policy adoption, while Kalliomaki (2008) indicated policy failure as the process was partly uninformed, incomplete, and inappropriate. Sheldrick et al. (Citation2017) indicated limited learning, while Wolman and Page (Citation2002) found little to no effect of learning on decisions.

4. Conclusions

Overall, this research has found increasing interest on C2C learning. There has been a significant uptake on studies that relate to C2C learning in the past decade as evidenced by the number of published articles in different journals. Empirical case studies show that climate change, transport, and local governance were the most common themes. As for geographical locations, cities within Europe and within North America – and when combined – represent almost half of the empirical case studies reviewed. Further research is needed on C2C learning in Asia, Africa, South America, and Australia. Special attention can also be given to different geographical configurations e.g. cities between Europe and Asia or Asia and Africa.

The results of the systematic literature review have shown conceptual, methodological, and empirical evidence for C2C learning. C2C learning is explicitly defined by a few studies (Calzada, Citation2020; Haupt et al., Citation2020; Moodley, Citation2020) which offers further opportunities for debate on how C2C learning can be conceptualized. Learning between cities is also linked to other related concepts, such as policy transfer, policy learning, and policy mobilities. The relationship between learning and other constructs can be explained by the need to understand how policies move from one city to another, on how policies mutate through various circuits and networks, and on how the outcomes of learning can be used to make better decisions. Likewise, there has been attention toward the contribution of partnerships and networks in facilitating learning and the link to the movement and mutation of policies.

As in Riche et al. (Citation2021), learning is not always clearly defined, measured, and compared to similar concepts; the focus or level of analysis for learning is sometimes unclear; and learning is not always explicitly depicted. As such, there is an overall need for more conceptual debate and clarity on C2C learning, the uptake of more diverse methodologies for investigating C2C learning, and on gathering of more empirical evidence to understand the contexts, processes, conditions, and effects – in an integrated way.

4.1. Toward a more conceptual clarity

In general, the processes for C2C learning can be complex and studies are starting to investigate how these exactly unfold. C2C learning, however, is more than just a singular activity, for example, information seeking or knowledge acquisition. C2C learning has different phases as well as mechanisms – although less than half of the reviewed studies have indicated these. Information seeking or search for information – as a starting point – has been a focus for understanding C2C learning. However, what happens after information seeking or knowledge acquisition is rarely investigated. From the results, the link between information seeking or knowledge acquisition and utilization can be explained by processing through problem framing and assessing information based on their quality and relevance. Further, studies should focus more on the perspective of information seekers – and not the sources of information. Interestingly, information seekers can also be information sources later on, too.

Defining clearly what the phases and mechanisms are would give clarity on the learning process. Building an integrated process-and-outcome model on C2C learning is then imperative. Herewith, this research paper contributes further to the debate by offering a definition as well as building a model for C2C learning. For this research paper, C2C learning can be defined as a dynamic yet sequential mutual process participated in by cities and their representatives which starts with exploration, followed by acquisition, utilization, and internalization. Each phase is activated by specific mechanisms and can be influenced by different conditions that can lead to multiplicity of outcomes. The perspectives of cities, and their representatives, who are ‘sources’ or ‘seekers’ of information, are also incorporated in this model. See for the C2C learning process.

The first phase is exploration which consists of the following mechanisms: internal assessment, information seeking and sharing, involvement of intermediaries, and foundation building. City actors engaged in C2C learning first conduct internal assessment, before making a decision to seek or to share information. During this phase, intermediaries, such as brokers and agents, can be involved and foundation is built through the establishment of links and agreements. Here, exploration can be influenced by similarity as well as proximity between and among cities.

The second phase is acquisition which includes acquiring, processing, and assessing information – which is eventually turned into knowledge. Here, information from other sources is interpreted based on problem framing and are assessed based on their quality and relevance. In this phase, city actors engaged in C2C learning internally do so – for mutual learning and for knowledge co-production. Also, knowledge can also be documented and stored for future use – which will be explained further in the next phase: utilization. Here, conditions that can influence learning include diversity as well as the nature of the learning process, particularly of the facilitators, purpose, and activities.

The third phase is utilization which refers to the use and uptake of knowledge. Combining the results from investigating the learning processes and outcomes, utilization occurs in a spectrum. Utilization can come in different ways – from adoption or adaptation to translation and co-creation up to policy failure and no effect on decision and can occur at different levels: individual, organizational, network, or a combination of any of these. In this phase, different conditions, such as organizational culture, political capacity, leadership, structural positions, institutional barriers, and power relations may be of influence.

Lastly, the fourth phase is internalization and similar to the last phase, this can come in different ways. These include, among others, anchoring to local practices and knowledge pipelines, supported implementation, after care, knowledge dissemination, and evaluation. The same conditions mentioned under the utilization phase may also be of influence here. Overall, process conditions can include resources, trust, time, inequality, and communication. As C2C learning can be radial and iterative process, the results of internalization also serve as inputs for future exploration. Further, cities may not have to go through all four phases (exploration, acquisition, utilization, and internalization) of C2C learning.

4.2. Toward more diverse methodologies

Majority of the studies were qualitative – as well as analyzing single cases – which can be attributed to the nature of the objectives, for example, aiming to understand the learning processes between cities and the concept, theory, or framework they are based on, for example, policy transfer and policy learning. Of the quantitative studies, these aimed at understanding overall learning patterns (Ansell et al., Citation2017; Baldersheim et al., Citation2002; Lee, Citation2019), investigating the effect of or conditions for learning (Einstein et al., Citation2019; Lundin et al., Citation2015) and/or were based on policy diffusion (Butler et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Pereira, Citation2021), which puts emphasis on identifying causal relationships. Causality has yet to be fully theorized and established in C2C learning.

For the future, quantitative methods can then be undertaken to understand in a broader way the C2C learning contexts, processes, conditions, and effects. Quantitative studies would also be of interest to understand process-and-condition configurations that can lead to desirable C2C learning outcomes. However, these can be difficult to achieve considering the need for large n studies. For more in depth understanding, a mixed method approach which combines quantitative and qualitative methods – as well as small n studies – can be undertaken as well. Longitudinal studies – although costly and time consuming – are also recommended to track C2C learning processes over time and to understand what effect these bring. Further, these studies are also applicable to investigate the link between individual and organizational learning.

4.3. Toward more empirical evidence

Further empirical analysis, which can make use of the C2C learning process-and-outcome model proposed in this paper, is needed to understand in more depth the contexts, processes, conditions, and outcomes of learning – in an integrated way. The actor and problem contexts for C2C learning are quite diverse but with more studies focused on climate change, transport, and local governance. With that, the objectives of C2C learning also varied considerably across the studies. C2C learning in the field of water management, urban regeneration, urban planning, public health, and smart cities, among others, are also growing. It is then of interest to examine further C2C learning in other urban focus. How C2C learning is facilitated by transnational networks, partnerships or cooperation programs, funded projects, and finance institutions is also of interest. A critical discussion on the role of these knowledge brokers, matchmakers, and facilitators is recommended.

Majority of the studies have investigated the actors involved in C2C learning. However, the roles and motivations e.g. from voluntary action to direct imposition (Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000) of actors are less explored. The specified roles, considering the terminologies and constructs used, imply one-directional learning, asymmetrical relationships, and power and equality issues. There is then a call toward a more nuanced approach to C2C learning instead of having a clear division of roles. The studies also focused primarily on understanding learning processes, followed by effect. Haupt et al. (Citation2020), for example, recommend understanding the importance of C2C learning processes on local (climate) governance and the extent to which these lead to local policy change on the ground.

Exploring the changes either cognitive, for example, new or reinforced ideas and/or behavioral, for example, new plans or policies at the individual and collective levels would be critical (Riche et al., Citation2021). Also, venues for learning have been examined, while the temporal dimension of learning is still unexplored. Less than half of the studies addressed the conditions and outcomes for C2C learning. Further research is then needed to understand the combination of conditions which can make learning effective – and its influence on certain outcomes. Overall, it is important to further empirically investigate the link(s) between the (wider patterns of) learning processes, the conditions under which C2C learning works, and (the multiplicity of) outcomes across different contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (79.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (41.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Prof. Dr. Jurian Edelenbos and Dr. Leon Van Den Dool from Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands for their review and feedback on this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A city can be viewed from different standpoints: the city as a space-occupying entity; the city as a dimensionless point located in a bounded space; and the city as one element in a network or system of urban centers (Parr, Citation2008).

2 Over the years, different concepts of learning have been examined: organizational learning (Argyris & Schon, Citation1974), collective learning (Gerlak & Heikkila, Citation2011; Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2013), policy-oriented learning (Sabatier, Citation1988), social learning (Hall, Citation1993), lesson drawing (Rose, Citation1991), political learning (Heclo, Citation1974), and government learning (Etheredge, Citation1979, Citation1981), among others. For comprehensive analysis, see Squevin et al. (Citation2021), Goyal and Howlett (Citation2018), Dunlop and Radaelli (Citation2018), Moyson and Scholten (Citation2017), Dunlop and Radaelli (Citation2013), Grin and Loeber (Citation2007).

3 Policy learning is the ‘use of information and knowledge to make predictions of the future, which are then used to make decisions’ (Bennett & Howlett, Citation1992). Policy transfer is ‘the process by which knowledge about policies, administrative arrangements, institutions and ideas in one political system … is used in the development of policies, administrative arrangements, institutions and ideas in another political system’ (Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000). Policy mobility emphasizes the mobile character of policies that continuously mutate and transform, depending on context-specific conditions (Peck, Citation2011). Policy diffusion is ‘a process in which policymaking and policy outcomes in one polity influence policymaking and policy outcomes in other polities’ (Blatter et al., Citation2022).

References

- Ansell, C., Lundin, M., & Öberg, P. (2017). How learning aggregates: A social network analysis of learning between Swedish municipalities. Local Government Studies, 43(6), 903–926. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1342626

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. Jossey-Bass.

- Baldersheim, H., Bucek, J., & Swianiewicz, P. (2002). Mayors learning across borders: The international networks of municipalities in east-central Europe. Regional & Federal Studies, 12(1), 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/714004723

- Bellinson, R., & Chu, E. (2019). Learning pathways and the governance of innovations in urban climate change resilience and adaptation. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(1), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1493916

- Bennett, C. J., & Howlett, M. (1992). The lessons of learning: Reconciling theories of policy learning and policy change. Policy Sciences, 25(3), 275. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138786

- Benson, D., & Jordan, A. (2011). What have we learned from policy transfer research? Dolowitz and marsh revisited Political Studies Review, 9(3), 366–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-9302.2011.00240.x

- Betsill, M. M., & Bulkeley, H. (2004). Transnational networks and global environmental governance: The cities for climate protection program. International Studies Quarterly, 48(2), 471–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-8833.2004.00310.x

- Blatter, J., Portmann, L., & Rausis, F. (2022). Theorizing policy diffusion: From a patchy set of mechanisms to a paradigmatic typology. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(6), 805–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1892801

- Bontenbal, M. C. (2013). Differences in learning practices and values in north-south city partnerships: Towards a broader understanding of mutuality. Public Administration and Development, 33(2), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1622

- Boulanger, S. O. M., & Nagorny, N. C. (2018). Replication vs mentoring: Accelerating the spread of good practices for the low-carbon transition. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 13(2), 316–328. https://doi.org/10.2495/SDP-V13-N2-316-328

- Bradlow, B. H. (2015). City learning from below: Urban poor federations and knowledge generation through transnational, horizontal exchange. International Development Planning Review, 37(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2015.12

- Bray, D. J., Taylor, M. A. P., & Scrafton, D. (2011). Transport policy in Australia – evolution, learning and policy transfer. Transport Policy, 18(3), 522–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.10.005

- Butler, D. M., de Vries, C., & Solaz, H. (2019). Studying policy diffusion at the individual level: Experiments on nationalistic biases in information seeking. Research and Politics, 6(4), 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168019891619

- Butler, D. M., Volden, C., Dynes, A. M., & Shor, B. (2017). Ideology, learning, and policy diffusion: Experimental evidence. American Journal of Political Science, 61(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12213

- Calzada, I. (2020). Replicating smart cities: The city-to-city learning programme in the replicate ec-h2020-scc project. Smart Cities, 3(3), 978–1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3030049

- Campbell, T. (2009). Learning cities: Knowledge, capacity and competitiveness. Habitat International, 33(2), 195–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2008.10.012

- Carolini, G., Gallagher, D., & Cruxen, I. (2018). The promise of proximity: The politics of knowledge and learning in south-south cooperation between water operators. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(7), 1157–1175. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418776972

- Cook, I. R., & Ward, K. (2012). Relational comparisons: The assembling of Cleveland’s waterfront plan. Urban Geography, 33(6), 774–795. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.33.6.774

- Devers-Kanoglu, U. (2009). Municipal partnerships and learning – investigating a largely unexplored relationship. Habitat International, 33(2), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2008.10.019

- Dolowitz, D., & Marsh, D. (1996). Who learns what from whom: A review of the policy transfer literature. Political Studies, 44(2), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00334

- Dolowitz, D. P., & Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contemporary policy-making. Governance, 13(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00121

- Dunlop, C. A. (2017a). Pathologies of policy learning: What are they and how do they contribute to policy failure? Policy and Politics, 45(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557316X14780920269183

- Dunlop, C. A. (2017b). Policy learning and policy failure: Definitions, dimensions and intersections. Policy and Politics, 45(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557316X14824871742750

- Dunlop, C. A., & Radaelli, C. M. (2013). Systematising policy learning: From monolith to dimensions. Political Studies, 61(3), 599–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00982.x

- Dunlop, C. A., & Radaelli, C. M. (2018). Practical lessons from policy theories. In The lessons of policy learning: Types, triggers, hindrances and pathologies. Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781447359821.003.0005

- Dussauge-Laguna, M. I. (2012). On the past and future of policy transfer research: Benson and Jordan revisited. Political Studies Review, 10(3), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-9302.2012.00275.x

- Einstein, K. L., Glick, D. M., & Palmer, M. (2019). City learning: Evidence of policy information diffusion from a survey of U.S. Mayors. Political Research Quarterly, 72(1), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912918785060

- Etheredge, L. S. (1979). Government learning: An overview. Center for International Studies.

- Etheredge, L. S. (1981). Government learning. In S. L. Long (Ed.), The handbook of political behavior (pp. 73–161). Plenum Press.

- Ettelt, S., Mays, N., & Nolte, E. (2012). Policy learning from abroad: Why it is more difficult than it seems. Policy & Politics, 40(4), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X643786

- Ewijk, E. (2016). Engaging migrants in translocal partnerships: The case of Dutch-Moroccan and Dutch-Turkish municipal partnerships. Population, Space and Place, 22(4), 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1872

- Farmer, D., & Perl, A. (2020). The role of policy learning in urban mobility adaptation: Exploring Vancouver’s plan to remove the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts. Urban Research & Practice, 13(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2018.1495758

- Gerlak, A. K., & Heikkila, T. (2011). Building a theory of learning in collaboratives: Evidence from the everglades restoration program. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(4), 619–644.

- Gerlak, A. K., Heikkila, T., Smolinski, S. L., Huitema, D., & Armitage, D. (2018). Learning our way out of environmental policy problems: A review of the scholarship. Policy Sciences: Integrating Knowledge and Practice to Advance Human Dignity, 51(3), 335–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-017-9278-0

- Glaser, M., Blake, O., Bertolini, L., te Brömmelstroet, M., & Rubin, O. (2021). Learning from abroad: An interdisciplinary exploration of knowledge transfer in the transport domain. Research in Transportation Business & Management, 39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2020.100531

- Glaser, M., & te Brömmelstroet, M. (2020). Unpacking policy transfer as a situated practice: Blending social, spatial, and sensory learning at a conference. Applied Mobilities, 7, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2020.1827559

- Goyal, N., & Howlett, M. (2018). Lessons learned and not learned: Bibliometric analysis of policy learning. In C. A. Dunlop, C. M. Radaelli, and P. Trein (Eds.), Learning in public policy: Analysis, modes and outcomes (pp. 27–49). Springer International Publishing.

- Grin, J, & Loeber, A. (2007). Theories of policy learning: Agency, structure and change. In F. Fischer, G. J. Miller, & M. S. Sidney (Eds.), Handbook of public policy analysis: Theory, politics, and methods (pp. 201–219). CRC Press.

- Gusenbauer, M., & Haddaway, N. R. (2020). Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, Pubmed, and 26 other resources. Research Synthesis Methods, 11(2), 181–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1378

- Hall, P. A. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275–296.

- Haupt, W. (2021). How do local policy makers learn about climate change adaptation policies? Examining study visits as an instrument of policy learning in the European Union. Urban Affairs Review, 57(6), 1697–1729. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087420938443

- Haupt, W., Chelleri, L., van Herk, S., & Zevenbergen, C. (2020). City-to-city learning within climate city networks: Definition, significance, and challenges from a global perspective. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 12(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2019.1691007

- Haupt, W., Chelleri, L., van Herk, S., & Zevenbergen, C. (2020). City-to-city learning within climate city networks: Definition, significance, and challenges from a global perspective. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 12(2), 143–159. http://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2019.1691007

- Heclo, H. (1974). Modern social politics in Britain and Sweden: From relief to income maintenance. Yale University Press.

- Heikkila, T., & Gerlak, A. K. (2013). Building a conceptual approach to collective learning: Lessons for public policy scholars. Policy Studies Journal, 41(3), 484–512. http://doi.org/10.1111/psj.2013.41.issue-3

- Ilgen, S., Sengers, F., & Wardekker, J. A. (2019). City-to-city learning for urban resilience: The case of water squares in Rotterdam and Mexico City. Water, 11(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/w11050983

- James, O., & Lodge, M. (2003). The limitations of ‘policy transfer’ and ‘lesson drawing’ for public policy research. Political Studies Review, 1(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/1478-9299.t01-1-00003

- Johnson, H., & Wilson, G. (2006). North-South/South-North partnerships: Closing the ‘mutuality gap. Public Administration and Development, 26(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.396

- Kalliomäki, H. (2018). Re-contextualising Oregon’s urban growth boundary to city-regional planning in Tere, Finland: The need for strategic bridge-building. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(4), 514–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1504980

- Keiner, M., & Kim, A. (2007). Transnational city networks for sustainability. European Planning Studies, 15(10), 1369–1395. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310701550843

- Lee, T. (2019). Network comparison of socialization, learning and collaboration in the c40 cities climate group. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(1), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1433998

- Lee, T., & Jung, H. Y. (2018). Mapping city-to-city networks for climate change action: Geographic bases, link modalities, functions, and activity. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.034

- Lee, T., & van de Meene, S. (2012). Who teaches and who learns? Policy learning through the c40 cities climate network. Policy Sciences, 45(3), 199–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-012-9159-5

- Lieto, L. (2015). Cross-border mythologies: The problem with traveling planning ideas. Planning Theory, 14(2), 115–129.

- Lundin, M., Oberg, P., & Josefsson, C. (2015). Learning from success: Are successful governments role models? Public Administration, 93(3), 733–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12162

- Ma, L. (2017). Site visits, policy learning, and the diffusion of policy innovation: Evidence from public bicycle programs in China. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 22(4), 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-017-9498-3

- Marsden, G., Frick, K. T., May, A. D., & Deakin, E. (2011). How do cities approach policy innovation and policy learning? A study of 30 policies in Northern Europe and North America. Transport Policy, 18(3), 501–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.10.006

- Marsden, G., May, A. D., Frick, K. T., & Deakin, E. (2012). Bounded rationality in policy learning amongst cities: Lessons from the transport sector. Environment and Planning A, 44(4), 905–920. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44210

- Marsden, G., & Stead, D. (2011). Policy transfer and learning in the field of transport: A review of concepts and evidence. Transport Policy, 18(3), 492–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.10.007

- Mocca, E. (2018). ‘All cities are equal, but some are more equal than others’. Policy mobility and asymmetric relations in inter-urban networks for sustainability. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 10(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2018.1487444

- Montero, S. (2017). Study tours and inter-city policy learning: Mobilizing Bogotá’s transportation policies in Guadalajara. Environment and Planning a: Economy and Space, 49(2), 332–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16669353

- Moodley, S. (2019). Defining city-to-city learning in Southern Africa: Exploring practitioner sensitivities in the knowledge transfer process. Habitat International, 85, 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.02.004

- Moodley, S. (2020). Exploring the mechanics of city-to-city learning in urban strategic planning: insights from Southern Africa. Social Sciences and Humanities Open, 2(1), 100027–100027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100027

- Moyson, S., & Scholten, P. (2017). Policy learning and policy change: Theorizing their relations from different perspectives. Policy and Society, 36(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1331879

- Ndebele-Murisa, M. R., Mubaya, C. P., Pretorius, L., Mamombe, R., Iipinge, K., Nchito, W., Mfune, J. K., Siame, G., & Mwalukanga, B. (2020). City to city learning and knowledge exchange for climate resilience in Southern Africa. PLoS One, 15(1), 0227915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227915

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The Prisma 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001

- Parr, J. B. (2008). Cities and regions: Problems and potentials. Environment and Planning a: Economy and Space, 40(12), 3009–3026. https://doi.org/10.1068/a40217

- Peck, J. (2011). Geographies of policy: From transfer-diffusion to mobility-mutation. Progress in Human Geography, 35(6), 773–797.

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2010). Recombinant workfare, across the Americas: Transnationalizing “fast” social policy. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 41(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.01.001

- Pereira, M. M. (2021). How do public officials learn about policy? A field experiment on policy diffusion. British Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 1428–1435. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000770

- Perkins, R., & Nachmany, M. (2019). ‘A very human business’ – transnational networking initiatives and domestic climate action. Global Environmental Change, 54, 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.11.008

- Pojani, D., & Stead, D. (2014). Dutch planning policy: The resurgence of tod. Land Use Policy, 41, 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.06.011

- Rich, R. F. (1997). Measuring knowledge utilization process and outcomes. Knowledge and Policy: The International Journal of Knowledge Transfer and Utilization, 10(3), 3–10.

- Riche, C., Aubin, D., & Moyson, S. (2021). Too much of a good thing? A systematic review about the conditions of learning in governance networks. European Policy Analysis, 7(1), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1080

- Rose, R. (1991). What is lesson-drawing? Journal of Public Policy, 11(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00004918

- Sabatier, P. A. (1988). An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences, 21(2/3), 129–168.

- Salskov-Iversen, D. (2006). Learning across borders: The case of Danish local government. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 19(7), 673–686. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550610704699

- Shefer, I. (2019). Policy transfer in city-to-city cooperation: Implications for urban climate governance learning. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1562668

- Sheldrick, A., Evans, J., & Schliwa, G. (2017). Policy learning and sustainable urban transitions: Mobilising Berlin’s cycling renaissance. Urban Studies, 54(12), 2739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016653889

- Sonesson, K., & Nordén, B. (2020). We learnt a lot: Challenges and learning experiences in a Southern African – North European municipal partnership on education for sustainable development. Sustainability, 12(20), 8607–8607. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208607

- Squevin, P., Aubin, D., Montpetit, É., & Moyson, S. (2021). Closer than they look at first glance: A systematic review and a research agenda regarding measurement practices for policy learning. International Review of Public Policy, 3(2), 146–171. http://doi.org/10.4000/irpp

- Takao, Y. (2014). Policy learning and diffusion of Tokyo’s metropolitan cap-and-trade: Making a mandatory reduction of total co2 emissions work at local scales. Policy Studies, 35(4), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2013.875151

- Tan, S.-Y., Taeihagh, A., & Sha, K. (2021). How transboundary learning occurs: Case study of the Asean Smart Cities Network (ascn). Sustainability, 13(11), 6502–6502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116502

- Valkering, P. J., Beumer, C., de Kraker, J., & Ruelle, C. (2013). An analysis of learning interactions in a cross-border network for sustainable urban neighbourhood development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 49, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.09.010

- van Ewijk, E. (2012). Mutual learning in Dutch-Moroccan and Dutch-Turkish municipal partnerships: Window on The Netherlands. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 103(1), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2011.00698.x

- Van Ewijk, E. v., Baud, I., Bontenbaul, M., Hordijk, M., Lindert, P. v., Nijenhuis, G., & Western, G. v. (2015). Capacity development or new learning spaces through municipal international cooperation: Policy mobility at work?. Urban Studies, 52(4), 756. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014528057

- Wilson, G., & Johnson, H. (2007). Knowledge, learning and practice in north-south practitioner-to-practitioner municipal partnerships. Local Government Studies, 33(2), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930701200544

- Wolman, H., & Page, E. (2002). Policy transfer among local governments: An information-theory approach. Governance, 15(4), 477–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0491.00198

- Wood, A. (2014). Learning through policy tourism: Circulating bus rapid transit from South America to South Africa. Environment and Planning A, 46(11), 2654–2669. https://doi.org/10.1068/a140016p

- Zhang, Y., & Wang, S. (2021). How does policy innovation diffuse among Chinese local governments? A qualitative comparative analysis of river chief innovation. Public Administration and Development, 41(1), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1901