Abstract

Although the production side of advertising has interested scholars for decades, research has focused primarily on isolated agency practices and interactions with clients. Discussion has been limited regarding how an ad agency coordinates and connects multiple activities and relationships, and how the agency setup has evolved over time. This question has become particularly interesting in the age of digitization, in which new forms of advertising require new ways of organizing production. In a case study of Forbes’s BrandVoice unit, this article specifically examines native advertising production via the business model lens, illustrating how BrandVoice consciously borrows production logics from journalism and distribution practices of platform economies. This study contributes to the understanding of the morphing of advertising production and agency work in the digital economy.

The advertising industry is facing enormous transformative pressures due to the forces of digitization. The availability of new technologies impacts and will continue to impact consumers’ behavioral patterns and advertising clients’ demands. Technological pressures will increasingly transform the structures of advertising markets and the business models (including the value propositions, skill sets, and internal organization) of agencies and other organizations active in these markets.

The traditional advertising industry as we know it has already gone through several cycles of change—from its emergence and growth during the 1950s and 1960s to the formation of large agency networks in the 1990s as a strategic response to globalization (Grein and Ducoffe Citation1998; Grabher Citation2001; West Citation1996) and the emergence of full service agencies (Beard Citation1996). Previous studies have described an industry that has changed incrementally and adaptively. In this change process, both new and old agencies have shared certain fundamental organizational logics (Grabher Citation2001).

Digitization, however, appears to be a different story, and for more than two decades, academics, columnists, and practitioners have competed to predict the end of advertising (Hatfield Citation2002; Rogers Citation2013; Rust and Oliver Citation1994). Despite these predictions, in 2018 there remains little evidence that the demand for marketing communications services will decrease. However, the convergence of cultural industries and the blurring of industry boundaries (Deuze Citation2016) have raised questions about whether there still is an “advertising market” in the traditional sense (Schultz Citation2016) and what the appropriate future definition of “advertising” as a product or service offering should be (Dahlen and Rosengren Citation2016).

With an industry in flux, new and old entrants appear on the advertising market with different business models and value propositions (“A Field Guide to Content Models” Citation2013; Shah and Sudhaman Citation2013). The foray into the digital advertising scene by alternative players, such as consulting firms, information technology (IT) firms, and publishers, precipitates the industry morphing, borderline blurring, and cross-pollination of practices. “Native advertising” has been recognized as one of these new format inventions in which “a marketer borrows from the credibility of a content publisher by presenting paid content with a format and location that matches the publisher’s original content” (Wojdynski and Golan Citation2016, p. 1403). It is an illustrative example of how advertising as a field is merging into the online media ecology (Turow Citation2011).

Although a growing number of studies have taken interests in readers’ responses to native advertising messages (Lee, Kim, and Ham Citation2016; Wojdynski Citation2016) and their effectiveness (van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016; Schauster, Ferrucci, and Neill Citation2016), we still know little about how native advertising induces changes to the producer side: ad agencies, new types of players, and their practices. An explication of the producer side is as important as one of the consumer side for understanding the nature of emerging formats of advertising that are transforming the industry.

Historically, the work of ad agencies has been studied mainly in terms of isolated practices, such as the work of agency creatives, strategic planning, media buying (Nyilasy and Reid Citation2009a, Citation2009b; Kover Citation1995a, Citation1995b; Hirschman Citation1989), and dyadic agency–client relationships (West and Paliwoda Citation1996). While these efforts have provided insights about certain internal practices and external interactions, they have not been able to demonstrate how those practices, as a whole, constitute a model to determine how the agency produces value for its customers and owners. Given the digital transformation and the rise of new advertising formats such as native advertising, content marketing, and branded content, there is a need to explore emerging agency types that have new structural arrangements, new value-creating activities, and new internal and external stakeholders and relationships. Through a business model lens, the characteristics of these new agency types can be revealed.

This article asks the following: How is native advertising produced by new types of players other than traditional advertising agencies? If there is a recipe, a pattern, or a model to characterize the operation, what is it? Aiming to depict how the new advertising format is practiced, this study carves a “type” (Baden-Fuller et al. Citation2010) or sketches a “story” (Magretta Citation2002) as a business model for native advertising production. The model functions as a lens to view new forms of advertising production. In doing so, this study contributes to the advertising literature by bringing new knowledge on how digitalization transforms the advertising industry and how new alternative ad production forms replace the legacy advertising model.

Literature Background

Native Advertising

Since 2012, native advertising has been surfing on the wave of mass media digitization and the proliferation of social media platforms (Del Rey Citation2012; Durrani Citation2014). Drawing elements from traditional communications formats such as advertorials, infomercials, sponsored content, and customer media, native advertising is marketers’ answer to banner blindness, advertising fatigue, and ad blocking. As a solution that goes beyond traditional display ads, marketers use native advertising to speak to their target consumers in a new way, in which consumers read and share content “in-stream” in a world of social media, websites, and apps (Albano Citation2015; Wojdynski and Golan Citation2016).

Ferrer Conill (Citation2016) defines native advertising as “a form of paid content marketing, where the commercial content is delivered, adopting the form and function of editorial content with the attempt to recreate the user experience of reading news instead of advertising content” (p. 905). Native advertising provides readers with content that matches the topics of publishers’ original content and at the same time copies the format of the editorial content (Wojdynski and Golan Citation2016). Native advertising remains a hotly debated marketing practice, with some observers declaring it as a temporary fix and others seeing it as work in progress. Related concepts include “content marketing” and “branded content,” which practitioners often use interchangeably with “native advertising.” Native advertising and content marketing are very similar to the difference in distribution: Native ads must be placed at paid media or publisher channels, while content marketing can occur at all possible outlets—owned, earned, and paid (Pulizzi Citation2013). As for “branded content,” both industry and academia have difficulties defining it with a clear circumscription. For the new category “Branded Content and Entertainment” launched in 2012, the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity specified that entries should be works of “the creation of, or natural integration into, original content by a brand” (Diaz Citation2015). Industry expert Joe Pulizzi comments that most entries in this category were campaign-based projects rather than ongoing editorial products, and there was heavy usage of product placement, putting the product as the central character of a story (Pulizzi Citation2015). The Cannes Lions Festival has never awarded a grand prix in this category, and the name of the category changed to the simpler “Entertainment” in 2016.

To date, the academic discussion on native advertising has focused particularly on the disclosure or nondisclosure of sponsoring brand labels, emphasizing that the blurring of boundaries between editorial and commercial content is of high concern for both the established advertising practice (Taylor Citation2017) and journalism (Ferrer Conill Citation2016; Stiernstedt Citation2016; Carlson Citation2015; Macnamara Citation2016). Some studies have shown how consumers evaluate native advertisements (Wojdynski Citation2016; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016; Wojdynski et al. Citation2017; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2015; Wang and Huang Citation2017) and how their intrusiveness affects consumers’ sharing intentions on social media (Lee, Kim, and Ham Citation2016).

However, the rise of this ad format changes previous assumptions about media, content production, marketing, journalism practice, and ethics (Wojdynski and Golan Citation2016; Ferrer Conill Citation2016; Matteo and Dal Zotto Citation2015; Stiernstedt Citation2016; Taylor Citation2017; Lahav and Zimand-Sheiner Citation2016). The burgeoning streams of research scattered in the domains of journalism, advertising, public relations, and marketing explain only part of the phenomenon. Although a few studies have begun to discuss native advertising from the perspectives of multiple stakeholders (e.g., Harms, Bijmolt, and Hoekstra Citation2017), there has been a dearth of attention to the business and operational aspects of native advertising problematizing the producer side, which offers promising empirical and theorizing opportunities, given the drastic transformations unfolding in various producers of native advertising (e.g., Matteo and Dal Zotto Citation2015).

Business Model

Advertising practitioners and academics have often resorted to borrowing various concepts, approaches, and methodologies to explain advertising (Schultz Citation2016). Though seldom applied in advertising scholarship, the business model lens seems apt as a methodological tool, a unit of analysis, or a framework for analyzing novel approaches in digital marketing practices, because it can capture a practice in a coherent way, uncover the business logic inherent in a company, and provide a way to view operation on the back end. A business model is the underlying business or industrial logic of a firm’s go-to-market strategy (Teece Citation2010) or a story which explains how a company works (Magretta Citation2002). This study uses the business model lens to analyze native advertising, a new marketing practice booming in the digital sphere.

Ad agencies’ business models have been stable for decades. Advertising agencies are a type of business organizations that perform activities to handle the production and distribution of commercial messages for clients to facilitate the marketing and promotion process (Gürel, Firlar, and Firlar Citation2015; Belch and Belch Citation2007). Strategic responses to external forces such as globalization have induced some modifications to their operational structures, revenue streams, and external ecosystems (West and Paliwoda Citation1996). Lightning-speed digital technology is triggering changes in the marketing scene, and classic ad agencies have been working hard to reinvent their business models (Dan and Rooney Citation2007; Fajen Citation2008). Their painful effort of transformation ranges from buying digital agencies to outsourcing talent on an ad hoc basis to experimenting with new monetizing models to adopting an Uber-like approach (Teinowitz Citation2008). Meanwhile, alternative players have begun to produce advertising in a variety of ways with viable business models.

Research topics about business models range from “what a business model is,” “what it is for,” “how it comes into being,” and the choice of business model to its relation to business performance (Teece Citation2010; Al-Debei and Avison Citation2010; Lambert and Davidson Citation2013). This study focuses on what the business model is by carving out the type or kind of business of native advertising players. A type usually bears a “nutshell” label, exemplified by such names as the “McDonald’s business model” and “razor-razor blade model.” A business model is similar to a recipe with ingredients. Baden-Fuller and Morgan (Citation2010) call these ingredients “strategic elements,” which could be resources, capabilities, products, customers, technologies, and markets. Osterwalder, Pigneur, and Tucci (Citation2005) use the alternative term “building block” and identify nine building blocks, including target customer, distribution channel, relationship, value configuration, core competency, partner network, and so on. In their review of the business model literature, Morris, Schindehutte, and Allen (Citation2005) identify 24 key components, and the most frequently cited ones include a firm’s value offering, economic model, customer interface/relationship, partner network/roles, internal infrastructure/connected activities, and target markets. Published empirical studies about business models show that there is no consensus over the key components of a business model, and components and the relationships between components are specific to an industry, a firm, and/or a region (Lambert and Davidson Citation2013).

In conducting the “model work,” as phrased by Baden-Fuller and Morgan (Citation2010), this study selects and operationalizes these core elements in a business model—the underlying logic, activity, resource, product, and business relationship (Zott and Amit Citation2013; Picard Citation2000; Osterwalder, Pigneur, and Tucci Citation2005). These elements are salient for this study, which has a conceptual focus on the operational aspect, rather than the economic or the strategic aspect, of business models. Each of them can explain and capture the characteristics of an observed kind of business. First, a business model articulates a logic (Teece Citation2010) that refers to the conceptual reasoning, rationale, or logic of existence behind a business. The logic could concern value creation (Wirtz, Schilke, and Ullrich Citation2010), value proposition to the customer (Zott, Amit, and Massa Citation2011), the way in which a company operates, or how to earn a profit (Teece Citation2010). Second, a resource is an element often included in business models discussed in the literature, with such concepts as resources and capabilities (Zott and Amit Citation2008), resource allocation, configuration of resources (Al-Debei and Avison Citation2010), resource-based theory (Barney Citation2001), and new combinations of resources. These resources could be physical, financial, and intangible. Third, business activities play an important role in the various conceptualizations of business models (Zott, Amit, and Massa Citation2011), and the activities include those associated with making products and those associated with selling products (Casadesus-Masanell and Tarzijan Citation2012). Some researchers treat business models as an activity system that includes interdependent activities that transcend the focal firm and spans its boundaries (Zott and Amit Citation2010). Fourth, a business model indispensably includes products and service offerings as part of the value proposition. A company produces products or provides services to serve needs in addressable market spaces, and new business models would involve new combinations of products, services, and information, or new product development (Zott and Amit Citation2008). Finally, a business model concerns a company’s relationships with various stakeholders—customers, suppliers, or important alliance partners (Teece Citation2010; Wirtz, Schilke, and Ullrich Citation2010)—and the success of an organization’s business model depends on the roles of these actors and their relationships (Al-Debei and Avison Citation2010). Similar to key ingredients in a recipe, these elements can fit together to constitute a business model. The analysis of the characteristics of these elements and the ways in which they are configured will lead to our crystallization of certain conceptual types, which can characterize the operation of native advertising production.

Methodology

Research Design

This study selects the U.S.-headquartered company Forbes and its BrandVoice unit, adopting a single case study approach (Siggelkow Citation2007). The case study approach is particularly appropriate when the focal phenomenon under investigation is new and unexplored (Eisenhardt Citation1989). In some fields of marketing and management, the case study is the most used research approach, and the single case is the most common design (Easton Citation2010). The case method involves rich, empirical descriptions of particular instances of a phenomenon based on a variety of data sources (Yin Citation2003). By prioritizing length and depth over breadth, the case method can provide the sort of detailed account that is almost missing from wider surveys of a field. Cases are therefore selected not because of their statistical representativeness but rather because of their power to provide exploratory, contextualized insights about the studied phenomenon (Siggelkow Citation2007)— in our case, how the advertising industry is reconfiguring its operations. By adopting this approach, this study can depict a rich picture of how native advertising, as a new form of agency, works in practice, grounded in real-life situations.

In academic research, scholars can use one case to create theoretical models and propositions (Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007). This study purposively chooses Forbes’s BrandVoice as a single, exemplar case because (a) it is an early mover in the native advertising segment and (b) it is successful, in that it has managed to grow its operations into a significant share of the company’s overall business. In addition, the company is pioneering in its digital transformation, as evidenced by its business performance (see Forbes and Its BrandVoice Unit, in the Findings section), multiple industry awards, and wide recognition by the trade press. This study therefore selects the case for its induction potential, as what BrandVoice does is not idiosyncratic but potentially representative of an emerging industrywide type of practice (Baden-Fuller and Morgan Citation2010) in native advertising. The experiments of BrandVoice could be symptomatic of increasing numbers of players that are joining the same bandwagon of running agency-like content studios dedicated to producing native advertising, content marketing, or branded content (e.g., NewsCred’s The Newsroom, The New York Times’s T Brand Studio, and BBC’s StoryWorks). As anecdotal evidence, Forbes has indeed become a training camp for native advertising executives, who have been hired by followers such as The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Hearst (Sebastian Citation2013). As argued by Siggelkow (Citation2007), this single case has the merits of being an illustration in a concrete example, unraveling the underlying dynamics of the operation, inspiring new ideas, and motivating future research.

Data Gathering

In 2010, Forbes began its digital business transformation, and BrandVoice was launched. Data covering the 2010 to 2017 period were gathered from three sources: the trade press, corporate business reports posted on official websites, and personal communications (). Trade press sources included both Advertising Age and online trade news outlets such as Digiday.com, AdExchanger.com, and Contently.com.

Table 1. Overview of gathered data.

Corporate business reports were retrieved from content posted on the official websites of Forbes (Forbes.com) and BrandVoice (Brandvoice.com). The sites offer firsthand artifacts of the company’s business documents, including media kits, value positions, descriptions of products and processes, quotes from executives, descriptions of job positions, lists of clients, case studies, the displayed native ads, and articles from the Inside Forbes column, written by the chief product officer of Forbes.

Finally, findings based on secondary sources were triangulated through a 60-minute semi-structured interview via Skype with the vice president of BrandVoice responsible for services, conducted on October 27, 2017. Follow-up e-mails were exchanged for clarification and extra questions. We did member-checking by sending a draft of the Findings section to Forbes executives to verify the accuracy of information, and revisions were made based on the feedback.

Data Analysis

The authors became familiar with the case company in the broader context of today’s digital advertising, publishing, and marketing landscapes. Materials were read and analyzed by both authors, yielding a synergistic view of the evidence. Texts underwent a process of “recursive” cycling among the case data, extant literature, and emerging theory (Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007).

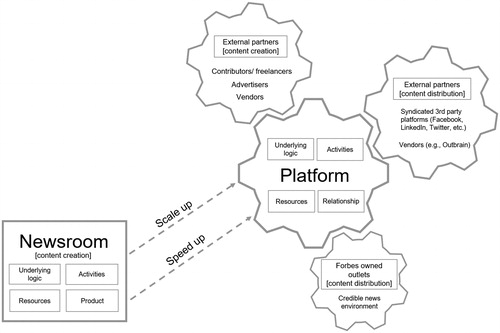

The unit of analysis is a business model that can vividly capture and depict the operation of BrandVoice. In the process of doing “model work” for building an exemplar case (Baden-Fuller and Morgan Citation2010), the key elements in a business model (Baden-Fuller and Morgan Citation2010; Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010; Teece Citation2010; Zott and Amit Citation2013)—underlying logic, resource, activity, product, and relationship—were selected to make sense of the empirical data, with these elements being the key components in the architecture of the would-be model. These elements were selected because it is in these elements and the combination of them that BrandVoice’s business model is novel from an operational perspective. When analyzing these components, the authors reflected on their characteristics, relationships, and implications, and resorted to pictures and metaphors as ways of theorizing (Morgan Citation1980). Then, the two concepts of “newsroom” and “platform” emerged as two higher-level constructs that can summarize the schematic characteristics of the would-be model, serving as its two prongs. Finally, the authors completed a sketching of the model constituted by the two prongs and their constituent components, which are visualized in with boxes and arrows.

Figure 1. Native advertising production at BrandVoice characterized by the “newsroom + platform” business model. (Clarifications: this model was constructed and interpreted by the authors of this article rather than being provided by Forbes. The term "newsroom" is used in a metaphorical manner to characterize the operation of BrandVoice, and it does not refer to the editorial newsroom of Forbes.)

In addition, the findings were compared with extant literature in advertising, media, and journalism for theory building (Eisenhardt Citation1989) by determining what has changed and what has not under the rubrics of “advertising research” (Huh Citation2016). This effort addresses the need for a discussion about the evolvement of advertising (Dahlen and Rosengren Citation2016; Huh Citation2016; Powers et al. Citation2012; Xie, Neill, and Schauster Citation2018).

Findings

Forbes and Its BrandVoice Unit

Founded by B.C. (Bertie Charles) Forbes and Walter Drey in 1917, Forbes is a media empire rooted in business journalism and is widely known for its ranking of the world’s richest people. The company remained in the Forbes family’s control until 2014, when a Hong Kong–based investment group acquired a majority share (Trachtenberg Citation2014). In 2010, the company began transforming its digital advertising strategy to comprise programmatic ad buying and native advertising. Labeling and positioning itself as a “global media and branding company,” Forbes is a hybrid entity that includes the businesses of a magazine, a website, mobile presence, conferences, real estate, education, financial services, and technology licensing (Launder Citation2013; Forbes.com Citation2017). As an extension of the print version, the Forbes website had 65 million visitors in 2017, according to ComScore (VP of BrandVoice responsible for services, Email communication, April 11, 2018). In 2016, digital accounted for 70% of the company’s total ad revenue (Hicks Citation2016). Forbes is no longer merely a magazine or a print media company. On the digital scene, it competes against multiple types of companies in the sectors of media, ad agencies, and digital platforms.

In 2010, Forbes launched AdVoice, later renamed BrandVoice, as the dedicated native advertising unit that runs paid content pieces for advertisers. Under Forbes’s revenue department, BrandVoice has its own profit-and-loss (P&L) statement (Sluis Citation2017). Serving 190-plus advertising clients, BrandVoice posted 40% annual growth rates in the years leading up to 2017 (VP of BrandVoice responsible for services, Email communication, April 11, 2018). With around 25 employees, BrandVoice has dedicated support from three main teams: sales, brand strategy (internal services for programs and presale), and the service team that works directly with advertising clients to execute programs. BrandVoice is positioned and labeled in different ways by Forbes and observers ().

Table 2. Different labels of BrandVoice.

The Two-Pronged Model

The resulting conceptual model has two key prongs, which we label the “newsroom” and the “platform.”Footnote1 The two labels—newsroom and platform—communicate the conceptual types of the business model of BrandVoice, hinting that we can view native advertising production as both a newsroom model and a platform model. The newsroom consists of internal operations focusing primarily on native advertising content creation, while the platform is a system for advertising management that leverages both internal and external partners (). Each prong has supportive processes, activities, and resources, reflecting the institutional and organizational arrangements of the work at BrandVoice. These business model contents are further discussed in the following sections.

The Newsroom

The BrandVoice newsroom is anchored on an “editorial approach,” similar to the work practices in typical news institutions, which imply unwritten rules and conventions in their “house style” of doing things (Bennett Citation2001). These unique work practices and conventions rooted in journalism are spilling over to the realm of marketing.

Underlying logic of the newsroom

BrandVoice’s newsroom logic is manifested in the discourses, organization forms, activities, processes, resources, and products that drive the ongoing operations for the delivery of content. Organization-wise, the editorial newsroom of Forbes and the native advertising newsroom at BrandVoice are clearly divided and do not share resources. However, BrandVoice still uses the logic and the intangible know-how of the editorial work in traditional media. To make native content newsy, BrandVoice contents “read more about a topic as opposed to about a brand” (Husni Citation2015), and BrandVoice plays off the news cycle by publishing contents that are timely and correlate with readers’ concerns, so that they have a greater chance of being read and shared (Moses Citation2015):

News means a lot of things. Our philosophy is to just give people good content and good information, things they need, to help them, so that they can learn, can use it in their jobs, or even be moved by the entertainment. It is just like any content. It is funny—as I often say, “There is bad editorial content, and there is good brand content.” Technically, a brand could and does do journalistic type of content. You could have similar content, and the content that is researched, interesting, storytelling, factual—all of that (of regular news media) from a marketer. (VP of BrandVoice responsible for services, interview, October 27, 2017)

The empirical materials from trade publications, company websites, and interview transcripts show the repetitive appearances of journalism jargon: editorial, content, stories, storytelling, journalistic credibility, publishing, audience, contributors, articles, beat, and pitch, among other terms. This discursive construction of a journalistic mentality at BrandVoice is in line with the trend that current practitioners in native advertising, content marketing, and branded content are embracing journalism, reflected by such expressions as “every company is a media company” (Bull Citation2013, p. 1) and “to think like a publisher” (Lieb Citation2011, p. 11).

Activities of the newsroom

Content creation and content distribution take center stage at BrandVoice, which very much resembles a media content production unit. Brand producers, in a role similar to that of account managers in ad agencies, own the process from start to finish, managing the workflow end to end. The in-house writers and outsourced freelancers undertake fundamental procedures of news reporting, including pitching and selecting topics, interviewing sources (some are advertising clients’ executives), and fact-checking. Common practices in a regular newsroom, such as editorial meetings, the editorial calendar, the beat system, and the gatekeeping mechanism, are practiced:

We have line editors, copy editors, and fact-checkers. And we are reviewing it as well to make sure it is sound. Some clients wanted to be more self-promotional in the past. We advised the client to be less promotional on the copy. We made recommendations on the content such as “Let’s take this paragraph out.” (VP of BrandVoice responsible for services, interview, October 27, 2017)

All the content pieces published by BrandVoice include a byline with the name of each author, which is a common practice in journalism rather than the norm in ad agencies. Creators in ad agencies are anonymous, while journalists in media outlets compete for a byline (Deuze Citation2007). The posts themselves are transparently labeled with a disclosure that it is advertiser content to make sure the reader understands the source:

We don’t label it as “This is coming from Forbes.” It is important for us to have the byline when we create the content, because we want to tell the readers who this piece of information is coming from. We put the writer’s bio at the bottom of the post. It is about being in the spirit of actual journalism. (VP of BrandVoice responsible for services, interview, October 27, 2017)

Resources of the newsroom

While many traditional media companies cut editorial resources from their newsrooms, Forbes invests strategically in BrandVoice to build capabilities in editorial writing and storytelling for brands. It has hired ex-journalists, designers, developers, and social media experts, some of whom used to work for legacy media. According to Forbes Chief Revenue Officer Mark Howard:

[M]any of them have traditional newsroom training from the editorial side; most of them worked in another newsroom with another company. The leader of that group for us actually started at Forbes magazine on the editorial product side, and then, she made the move over, completely severing all of her responsibilities and connections to the editorial edit product to really create and really build out the team that is this brand newsroom and team of brand producers. (Keck Citation2014)

Product of the newsroom

The core product produced by BrandVoice is the content. Types of content published by BrandVoice include text stories, motion infographics, videos, case studies, and social components, some of which are new genres of content in the digital environment. The content itself is not a place for marketers to list the features of products and services but rather a forum to provide domain expertise and insights to authentically engage with the audience (Manafy Citation2014). BrandVoice aims to create high-quality content, in line with the argument of native advertising champions that the quality of native ads must be as good as that of editorial content (Leavitt Citation2012; Eliasson Citation2017). Former chief executive officer and current vice chairman Mike Perlis comments, “[W]e’re not letting people use this as an advertising vehicle. There are times when the BrandVoice content is the most popular on the site” (Khanna Citation2016).

Our philosophy is to help a client become a trusted source on topics with thought-leadership-type content. Our partners are amazing experts in whatever they do. They know it, and they provide the information. (VP of BrandVoice responsible for services, interview, October 27, 2017)

Summary about the newsroom

The newsroom label captures the tenet of the model—a philosophy and approach of the firm organizing and integrating elements of various activities (Baden-Fuller et al. Citation2010), typical of a news institution. Advertising has always borrowed the conventions of other cultural production genres, such as drama and movies (Scott Citation1994). For native advertising, content marketing, and branded content, the new genre to be borrowed is an age-old trade struggling for its own survival: journalism. Native advertising marketers still do not escape the old trick: to try to make an ad look like something other than an ad to counter the defensive posture of consumers. However, the model highlights that it is in its organization and logics as much as in its output formats that native advertising production differs from traditional ad agency work.

The Platform

“Platform” is a frequently reoccurring term when Forbes describes BrandVoice: “integrated content distribution platform,” “content marketing platform,” “thought leadership and storytelling platform for marketers,” and “content publishing platform” (Forbes.com Citation2017). The platform is a hub and a publishing system that involves content creation, content distribution outlets, analytics, and governance. On one hand, the platform mediates, governs, and coordinates internal and external content generation resources. On the other hand, it integrates and manages content distribution resources. Our analysis focuses on the platform’s underlying logic, activities, resources, and BrandVoice’s relationships with engaged partners.

Underlying logic of the platform

The business model of BrandVoice is platform based, going beyond the boundaries of a traditional ad agency and externalizing its operations. The platform brings together external content creation partners (advertisers, vendors, and freelance contributors) and external content distribution partners (syndicated third-party platforms and vendors) () in a holistic manner of dealing with content. The platform connects content creation with distribution and amplifies the content with a large-scale reach. Through self-service processes and the leverage of external partners, it results in scalability, speed, and network effects (Shaughnessy Citation2016). Compared with the traditional ad agency model, which is labor intensive and difficult to scale, the platform breaks the scale barrier by distributing content at scale, expediting the publishing process, and casting a broader net for content in the digital sphere (see the arrows connecting “newsroom” and “platform” in ).

Activities of the platform

In the spirit of “making clients better content marketers,” as stated by the vice president of BrandVoice responsible for services, the platform enables advertising clients to publish via three routes: using the BrandVoice newsroom and its freelance network of topic experts, authoring their own content, and repurposing content already created by other publishers or agencies. For the latter two routes, the platform enables advertisers to self-publish in a self-service mode. An advertiser can publish contents created by another publisher or agency as long as it has distribution rights.

Traditional ad agencies usually do not deal with distribution directly but instead delegate the work to media-buying agencies and media outlets. BrandVoice deals with content creation and distribution holistically. For native content distribution, BrandVoice leverages third-party social media platforms such as Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter. In addition, for some programs, BrandVoice may include paid distribution on social or Web distribution platforms such as OutBrain (Shah and Sudhaman Citation2013).

Resources of the platform

As a platform that orchestrates resources, BrandVoice is enabled by an IT infrastructure, including a content management system (CMS), a native ad server, and analytic dashboard tools. The CMS and the ad server can perform geolocation targeting of readers by presenting targeted content to a reader in the natural flow of an infinite scroll (Goodfellow Citation2017). With expertise in graphic design, front-end design, back-end engineering, and data analytics (Sluis Citation2016), the BrandVoice service team analyzes reader data and insights and sends advertising clients reports that include organic and paid traffic, time spent, social engagement, referral sources, audience makeup, and more. Clients and other partners can log in to see program data on their dashboards (Keck Citation2014).

BrandVoice leverages Forbes-owned multiple outlets to distribute content: the official site, RSS feeds, content streams in all of Forbes’s relevant channels, the print magazine, and events; all of these constitute a platform itself, treated as an overall “credible news environment” by Forbes executives (Dvorkin Citation2016) (). Since 2010, Forbes has nurtured a network of 1,200 editorial topic experts as contributors, some of whom are trade journalists (Keck Citation2014). They publish to the Forbes.com platform, covering the beats in which they specialize, providing their expertise, and consequently enhancing the value of the platform.

Relationships of the platform

The symbiotic relationship between BrandVoice and its advertising clients is service-oriented, prioritizing helping over selling space and audience. In cooperative processes, BrandVoice offers advertisers varying degrees of access to its resources. For example, the BrandVoice platform is open to advertisers, who can publish directly to the platform. The creation and delivery of native ads rely on multiple actors: advertisers, freelance contributors, syndicated third-party platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Linkedin, etc.), and content distribution agencies like OutBrain. BrandVoice orchestrates these external partners that can complement or enhance the activities of some internal functions of traditional ad agencies. Analogous to gears driving each other (), the BrandVoice platform and the constellation of partners work synergistically to create the network effect, which means that when the number of participants grow, the value increases for everyone (Van Alstyne, Parker, and Choudary 2016).

Summary about the platform

As a new way of organizing native advertising production, the BrandVoice platform draws on both internal and external skills and resources, and thus, it acts as a hybrid of an ad agency, a newsroom, a distribution channel, and a marketing consulting firm. As a platform owner, BrandVoice traverses different commercial sectors (Shaughnessy Citation2016) and shows new options for native advertising producers as it moves into new terrains that go beyond the boundaries of an old-fashioned ad agency model.

Discussion and Conclusion

Using the business model lens as a new avenue of investigation, this study analyzes how native advertising is produced by conducting a case study of Forbes’s BrandVoice unit. A business model perspective is applied to capture and construct the practices of BrandVoice into a model that comprises two prongs—the newsroom and the platform—and their constituent elements: the underlying logics, activities, resources, products, and business relationships. The two labels—newsroom and platform—communicate the conceptual types of the business model of BrandVoice, hinting that we can view native advertising production as both a newsroom model and a platform model. The newsroom is backed by knowledge in editorial practice, which involves human judgment and internal processes. Backed by technology, the platform is a publishing platform and an integration mechanism that connects a constellation of external partners and deals with content creation and distribution in a holistic manner. The platform enables self-publishing, scalability, speed, and network effects. The labels of the two prongs represent the schematic characteristics of the business model, which characterizes native advertising as a new advertising practice and illustrates how a school of players conducts digital native advertising in new ways.

The findings illustrate the changing nature of advertising production and allow readers to see the native advertising world in a new way. First, native advertising triggered a shift in the advertisingscape from the “creative play” to the “journalism play,” as marketers resort to journalism logic and practices to experiment with new ways of creating and distributing digital commercial messages. The ad agency world has been considered as a part of the creative industries, and ad people have prided themselves on their creative work. Many past advertising production studies focus on the issue of creativity (Nyilasy, Canniford, and Kreshel Citation2013; Nyilasy and Reid Citation2009a; Kover Citation1995b; Turnbull and Wheeler Citation2017), analyzing its nature, process, social context, and relationship to effectiveness. Nyilasy and Reid (Citation2009b) treat “creativity” as a key element in the ontological status of advertising, which is a territory defined by creativity, art, and tacit skill. Creativity has also been identified as the singular most important factor in ad effectiveness (Nyilasy and Reid Citation2009a). The creative process has been characterized as idiosyncratic, personal, unpredictable, and similar to artistic work (Kover Citation1995b), and there is “no rule” to be found to guide this process in advertising work, thus placing it mostly outside the reach of scientific modeling (Nyilasy and Reid Citation2009b). Under digital native advertising, practitioners’ focus is on “editorial” and “publishing,” representing codified ways of doing things (Grabher Citation2004), backed by a set of routines, standardized activities, processes, and tools rooted in journalism. Work is to be delivered in a repetitive and predictable manner. Our analysis and trade press coverage show that the discourses of practitioners of native advertising, content marketing, and branded content are dominated by journalism jargon rather than the notion of “creativity.” News work characterizes native advertising, whose way of working is more a mode of “advertising as media work” (Deuze Citation2016, p. 332).

Second, we ask the question about the ontology of advertising production research, particularly whether the “ad agency” is still a distinctive subsector or unit for analysis. There are several implicit assumptions in studies of advertising from a production perspective (Cronin Citation2004; Hirschman Citation1989; Kover Citation1995a, Citation1995b; Nyilasy, Canniford, and Kreshel Citation2013; Nyilasy and Reid Citation2009a; Turnbull and Wheeler Citation2017). First, regarding the research about advertising production, the classic ad agency is the default institution to examine. Second, the internal structure and operation of an ad agency are fixed as usual, with discrete and well-defined departments or roles (i.e., account planning, account handling, creative, media buying and planning, and consumer insights). Third, ad agencies are situated in a stable advertising ecology in which different participating organizations (ad agencies, media buying agencies, media, and so on) have their respective, well-demarcated roles. The new ad formats of native advertising, content marketing, and branded content disrupt the operation model, structure, norms, and process of the institution of ad agencies, as well as the ecosystem. BrandVoice assumes the roles of different disciplines as an integrator of internal and external actors, assembling and configuring resources and activities through an open platform. Digital native advertising triggered a new ecosystem in which the work of producing native ads is being diffused to a wide array of actors, whose disciplinary boundaries are blurring. This new reality will upend previous assumptions in advertising production research.

Despite all these changes and transformations, the business model of BrandVoice does not involve revolutionary changes for advertising and its production. There remain some continuities from the practice of classic ad agencies, and there is little change in the revenue model of BrandVoice—its revenue source and pricing scheme have remained largely the sameFootnote2; it charges advertising clients service fees on a retainer or campaign-based basis. The role of BrandVoice remains the same—that of a mediator through which advertisers can reach the audience. The BrandVoice way involves incremental adaptations and evolutions in advertising production as a response to the changing milieu.

Advertising is here to stay, but it now operates in different ways. The case of Forbes’s BrandVoice provides fresh empirical evidence and theoretical perspectives to reimagine and recalibrate a new genre of players producing native advertising, content marketing, and branded content. This topic has a rare focus on extant scholarship in advertising and media, and thus, this article opens up a new arena for discussion. For industry practitioners, this study provides a perspective to view the nature of the emerging advertising formats of native advertising, content marketing, and branded content, as well as moments of reflection about their work.

Limitations and Future Research

This case study focuses on capturing the type and model of the operation of native advertising at BrandVoice without tapping into the lived reality of everyday work in the organization. The study does not provide direct insights into the “black box,” in which personnel perform and experience microlevel, day-to-day activities and practices (compare Ots and Nyilasy Citation2015) within an organization that produces native ads. The single case study is limited in its generalizability, and future studies can examine other players that run similar content studios producing native ads, content marketing, and branded content, and can compare multiple case studies. Isomorphism could be expected among different players, and replications among cases can enhance the analytical power and make emergent theories for native advertising production more generalizable, yielding industry-level explanations (Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007). To unravel the black box of native advertising production, future research can use interviews or ethnographic methods to more closely analyze the inner workings of case companies. For a better grasp on how native advertising works under transformative dynamics, researchers can observe how the staffs of companies work and can speak to those who perform daily tasks (Cunningham and Haley Citation2000).

Notes

Notes

1 The model in this study was constructed and interpreted by the authors of this article rather than being provided by Forbes. The term newsroom in this article is used in a metaphorical manner to characterize the operation of BrandVoice, and it does not refer to the editorial newsroom of Forbes.

2 BrandVoice has a charging scheme covering a continuum with three options: “Elite” for long-term publishing, “Stories” for campaign-based light publishing, and “Special Feature” for phased content roll-out (http://www.brandvoice.com/products/). BrandVoice has introduced one innovation in charging clients with a money-back guarantee scheme based on measurement of metrics of performance in awareness, favorability, recall, and purchase intent (Moses Citation2016).

References

- “A Field Guide to Content Models” (2013), Advertising Age, 84 (33), 30.

- Albano, Patrick (2015), “Tech Viewpoint on Native Advertising,” Campaign US, September 3, https://www.campaignlive.com/article/tech-viewpoint-native-advertising/1362279.

- Al-Debei, Mutaz M., and David Avison (2010), “Developing a Unified Framework of the Business Model Concept,” European Journal of Information Systems, 19 (3), 359–76.

- Baden-Fuller, Charles, Benoît Demil, Xavier Lecoq, and Ian MacMillan (2010), “Editorial: Special Issue on Business Models,” Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 143–45.

- ——, and Mary S. Morgan (2010), “Business Models as Models,” Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 156–71.

- Barney, Jay B. (2001), “Resource-Based Theories of Competitive Advantage: A Ten-Year Retrospective on the Resource-Based View,” Journal of Management, 27 (6), 643–50.

- Beard, Fred (1996), “Integrated Marketing Communications: New Role Expectations and Performance Issues in the Client–Ad Agency Relationship,” Journal of Business Research, 37 (3), 207–15.

- Belch, George E., and Michael A. Belch (2007), Advertising and Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective, New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Bennett, Lance (2001), News: The Politics of Illusion, 4th ed., New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

- Brandvoice.com (2017), accessed July 1, www.brandvoice.com/support/.

- Carlson, Matt (2015), “When News Sites Go Native: Redefining the Advertising–Editorial Divide in Response to Native Advertising,” Journalism, 16 (7), 849–65.

- Bull, Andy (2013), Brand Journalism, New York: Routledge.

- Carlson, Matt (2015), “When News Sites Go Native: Redefining the Advertising–Editorial Divide in Response to Native Advertising,” Journalism, 16 (7), 849–65.

- Casadesus-Masanell, Ramon., and Jorge Tarzijan (2012), “When One Business Model Isn’t Enough,” Harvard Business Review, 90 (1/2), 132–37.

- Cronin, Anne M. (2004), “Regimes of Mediation: Advertising Practitioners As Cultural Intermediaries,” Consumption Markets and Culture, 7 (4), 349–69.

- Cunningham, Anne, and Eric Haley (2000), “A Look inside the World of Advertising-Free Publishing: A Case Study of Ms. Magazine,” Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 22 (2), 17–30.

- Dahlen, Micael, and Sara Rosengren (2016), “If Advertising Won’t Die, What Will It Be? Toward a Working Definition of Advertising,” Journal of Advertising, 45 (3), 334–45.

- Dan, Avi, and Jennifer Rooney (2007), “Agencies Must Wake Up to a Different Business Model,” Advertising Age, 78 (38), 18–19.

- Del Rey, Jason (2012), “Native Advertising: Media Savior or Just the New Custom Campaign?,” Advertising Age, 83 (39), 12–13.

- Deuze, Mark (2007), Media Work, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press.

- —— (2016), “Living in Media and the Future of Advertising,” Journal of Advertising, 45 (3), 326–33.

- Diaz, Ann-Christine (2015), “Did the Cannes Lions Unveil a Crisis of Content Creativity?,” Advertising Age, 86 (17), 42.

- Durrani, Arif (2014), “Native Ads Represent an Exciting New Opportunity for Savvy Media Agencies,” Campaign, February 6, https://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/native-ads-represent-exciting-new-opportunity-savvy-media-agencies/1229925.

- Dvorkin, Lewis (2016), “Inside Forbes: How Native Ads in Our Magazine Are Inspiring Digital and Video Ideas,” Forbes, August 30, https://www.forbes.com/sites/lewisdvorkin/2016/08/30/inside-forbes-how-native-ads-in-our-magazine-are-inspiring-digital-and-video-ideas/#2012750f31ef.

- Easton, Geoff (2010), “Critical Realism in Case Study Research,” Industrial Marketing Management, 39 (1), 118–28.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. (1989), “Building Theories from Case Study Research,” Academy of Management Review, 14 (4), 532–50.

- ——, and Melissa E. Graebner (2007), “Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges,” Academy of Management Journal, 50 (1), 25–32.

- Eliasson, Johanne (2017), “Native Advertising Must Be As Good As Your Editorial Content [Web Log Post],” Native Advertising Institute, https://nativeadvertisinginstitute.com/blog/native-advertising-editorial-content/.

- Fajen, Stephen (2008), “The Agency Model Is Bent but Not Broken,” Advertising Age, 79 (26), 17.

- Ferrer Conill, Raul (2016), “Camouflaging Church As State: An Exploratory Study of Journalism’s Native Advertising,” Journalism Studies, 17 (7), 904–14.

- Forbes.com (2017), accessed August 28, www.forbes.com.

- Goodfellow, Jessica (2017), “Forbes Introduces Geolocation Targeting to BrandVoice Content [Web Log Post],” The Drum, February 23, http://www.thedrum.com/news/2017/02/23/forbes-introduces-geolocation-targeting-brandvoice-content; https://www.forbes.com/forbes-media/who-we-are/;https://www.forbes.com/careers-at-forbes/#61f018077820.

- Grabher, Gernot (2001), “Ecologies of Creativity: The Village, the Group, and the Heterarchic Organisation of the British Advertising Industry,” Environment and Planning A, 33 (2), 351–74.

- —— (2004), “Temporary Architectures of Learning: Knowledge Governance in Project Ecologies,” Organization Studies, 25 (9), 1491–1514.

- Grein, Andreas, and Robert Ducoffe (1998), “Strategic Responses to Market Globalisation among Advertising Agencies,” International Journal of Advertising, 17 (3), 301–19.

- Gürel, Pinar Altiok, Talat Firlar, and Nursen Firlar (2015), “The Organizational Structure of Advertising Agencies and New Directions,” in Handbook of Research on Effective Advertising Strategies in the Social Media Age, Nurdan Öncel Takran and Recep Ylmaz, eds., Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 90–105.

- Harms, Bianca, Tammo H.A. Bijmolt, and Janny C. Hoekstra (2017), “Digital Native Advertising: Practitioner Perspectives and a Research Agenda,” Journal of Interactive Advertising, 17 (2), 1–12.

- Hatfield, Stefano (2002), “Cannes, Creativity, and the Death of Print Advertising,” Advertising Age, 73 (25), 30.

- Hicks, Robin (2016), “Forbes Revenue Chief Mark Howard on Rewriting the Publishing Model with Programmatic and Native Advertising [Web Log Post],” Mumbrella Asia, February 29, http://www.mumbrella.asia/2016/02/forbes-revenue-chief-mark-howard-rewriting-publishing-model-programmatic-native-advertising/.

- Hirschman, Elizabeth C. (1989), “Role-Based Models of Advertising Creation and Production,” Journal of Advertising, 18 (4), 42–53.

- Huh, Jisu (2016), “Comment: Advertising Won’t Die, but Defining It Will Continue to Be Challenging,” Journal of Advertising, 45 (3), 356–58.

- Husni, Samir (2015), “Forbes and the BrandVoice Match-Making: Mark Howard, Forbes’ Chief Revenue Officer and Chief Match-Maker Explains and Elaborates—The Mr. Magazine Interview [Web Log Post],” Mr. Magazine, June 5, https://mrmagazine.wordpress.com/2015/06/05/forbes-and-the-brandvoice-match-making-mark-howard-forbes-chief-revenue-officer-and-chief-match-maker-explains-and-elaborates-the-mr-magazine-interview/.

- Keck, Julie (2014), “3 Questions for Forbes’ Mark Howard about Native Advertising [Web Log Post],” Media Shift, June 3, http://mediashift.org/2014/06/3-questions-for-forbes-mark-howard-about-native-advertising/?utm_source=MediaShift+Daily&utm_campaign=3d41ebc579-RSS_EMAIL_CAMPAIGN&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_70e55682fc-3d41ebc579-299948561.

- Khanna, Vikram (2016), “The Midas of Publishing: CEO of Forbes, Mike Perlis, Talks about How He Remade a 95-Year-Old Publishing Business [Web Log Post],” The Business Times, October 1, https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/the-raffles-conversation/the-midas-of-publishing.

- Kover, Arthur J. (1995a), “Copywriters’ Implicit Theories of Communication: An Exploration,” Journal of Consumer Research, 21 (4), 596–611.

- —— (1995b), “The Games Copywriters Play: Conflict, Quasi-Control, a New Proposal,” Journal of Advertising Research, 35 (4), 52–62.

- Lahav, Tamar, and Dorit Zimand-Sheiner (2016), “Public Relations and the Practice of Paid Content: Practical, Theoretical Propositions and Ethical Implications,” Public Relations Review, 42 (3), 395–401.

- Lambert, Susan C., and Robyn A. Davidson (2013), “Applications of the Business Model in Studies of Enterprise Success, Innovation, and Classification: An Analysis of Empirical Research from 1996 to 2010,” European Management Journal, 31 (6), 668–81.

- Launder, William (2013), “Should Forbes Be Valued as Online Business? Publisher Aims to Convince Bidders It Deserves to Be Priced on Digital Properties,” Wall Street Journal, December 20.

- Leavitt, Lydia (2012), “Why Branded Content Is Beating Editorial [Web Log Post],” Digiday, December 10, https://digiday.com/marketing/why-branded-content-is-beating-editorial/.

- Lee, Joonghwa, Soojung Kim, and Chang-Dae Ham (2016), “A Double-Edged Sword? Predicting Consumers’ Attitudes toward and Sharing Intention of Native Advertising on Social Media,” American Behavioral Scientist, 60 (12), 1425–41.

- Lieb, Rebecca (2011), Content Marketing: Think Like a Publisher—How to Use Content to Market Online and in Social Media, Indianapolis, IN: Que.

- Macnamara, Jim (2016), “The Continuing Convergence of Journalism and PR: New Insights for Ethical Practice from a Three-Country Study of Senior Practitioners,” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 93 (1), 118–41.

- Magretta, Joan (2002), “Why Business Models Matter,” Harvard Business Review, 80 (5), 86–93.

- Manafy, Michelle (2014), “Q&A: Mark Howard, CRO Forbes Media, on Creating Native Advertising Content [Web Log Post],” Digital Content Next, June 25, https://digitalcontentnext.org/blog/2014/06/25/qa-mark-howard-cro-forbes-media-on-creating-native-advertising-content/.

- Matteo, Stephane, and Cinzia Dal Zotto (2015), “Native Advertising, or How to Stretch Editorial to Sponsored Content within a Transmedia Branding Era,” in Handbook of Media Branding, Gabriele Siegert, Kati Förster, Sylvia M. Chan-Olmsted, and Mart Ots, eds., Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 169–85.

- Morgan, Gareth (1980), “Paradigms, Metaphors, and Puzzle Solving in Organization Theory,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 25 (4), 605–22.

- Morris, Michael, Minet Schindehutte, and Jeffrey Allen (2005), “The Entrepreneur’s Business Model: Toward a Unified Perspective,” Journal of Business Research, 58, 726–35.

- Moses, Lucia (2015), “How Publishers Make Native Ads Newsy [Web Log Post],” Digiday, March 3, https://digiday.com/media/publishers-make-native-ads-newsy/.

- —— (2016), “Forbes Guarantees Its Native Ads Will Work [Web Log Post],” Digiday, February 8, https://digiday.com/media/inside-forbess-new-money-back-guarantee-native-ads-will-work/.

- Nyilasy, Gergely, Robin Canniford, and Peggy J. Kreshel (2013), “Ad Agency Professionals’ Mental Models of Advertising Creativity,” European Journal of Marketing, 47 (10), 1691–1710.

- ——, and Leonard N. Reid. (2009a), “Agency Practitioner Theories of How Advertising Works,” Journal of Advertising, 38 (3), 81–96.

- ——, and —— (2009b), “Agency Practitioners’ Meta-Theories of Advertising,” International Journal of Advertising, 28 (4), 639–68.

- Osterwalder, Alexander, and Yves Pigneur (2010), Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- ——, and Christopher L. Tucci (2005), “Clarifying Business Models: Origins, Present, and Future of the Concept,” Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16, 1–25.

- Ots, Mart, and Gergely Nyilasy (2015), “Integrated Marketing Communications (IMC): Why Does It Fail? An Analysis of Practitioner Mental Models Exposes Barriers of IMC Implementation,” Journal of Advertising Research, 55 (2), 132–45.

- Picard, Robert G. (2000), “Changing Business Models of Online Content Services,” International Journal on Media Management, 2 (2), 60–68.

- Powers, Todd, Dorothy Advincula, Manila S. Austin, Stacy Graiko, and Jasper Snyder (2012), “Digital and Social Media in the Purchase Decision Process: A Special Report from the Advertising Research Foundation,” Journal of Advertising Research, 52 (4), 1–20.

- Pulizzi, Joe (2013), Epic Content Marketing: How to Tell a Different Story, Break through the Clutter, and Win More Customers by Marketing Less, New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education Publication.

- —— (2015), “Can We Please Stop Using Branded Content? [Web Log Post],” Content Marketing Institute, October 6, https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/2015/10/stop-using-branded-content/.

- Rogers, Danny (2013), “The Death of Advertising, but Only as We Know It,” Campaign, March 21, https://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/death-advertising-know/1175483.

- Rust, Roland T., and Richard W. Oliver (1994), “The Death of Advertising,” Journal of Advertising, 23 (4), 71–77.

- Schauster, Erin E, Patrick Ferrucci, and Marlene S. Neill (2016), “Native Advertising Is the New Journalism: How Deception Affects Social Responsibility,” American Behavioral Scientist, 60 (12), 1408–24.

- Schultz, Don (2016), “The Future of Advertising or Whatever We’re Going to Call It,” Journal of Advertising, 45 (3), 276–85.

- Scott, Linda (1994), “The Bridge from Text to Mind: Adapting Reader-Response Theory to Consumer Research,” Journal of Consumer Research, 21 (3), 461–80.

- Sebastian, Michael (2013), “Need a Native-Ad Hotshot? Find a Former Forbes Exec,” Advertising Age, 84 (42), 11.

- Shah, Aarti, and Arun Sudhaman (2013), “The PR World’s Play for Content Marketing Clout [Web Log Post],” Holmes Report, June 15, https://www.holmesreport.com/long-reads/article/the-pr-world-s-play-for-content-marketing-clout.

- Shaughnessy, Haydn (2016), “Harnessing Platform-Based Business Models to Power Disruptive Innovation,” Strategy and Leadership, 44 (5), 6–14.

- Siggelkow, Nicolaj (2007), “Persuasion with Case Studies,” Academy of Management Journal, 50 (1), 20–24.

- Sluis, Sarah (2016), “Forbes CRO Sees Industry ‘On the Cusp of a Content Bubble’ [Web Log Post],” AdExchanger, February 3, https://adexchanger.com/the-sell-sider/forbes-cro-sees-industry-on-the-cusp-of-a-content-bubble/#more-105389.

- —— (2017), “Why Forbes Split Up Its Integrated Sales Team [Web Log Post],” AdExchanger, February 27, https://adexchanger.com/publishers/forbes-split-integrated-sales-team/.

- Stiernstedt, Fredrik (2016), “Blurring the Boundaries in Practice? Economic, Organisational, and Regulatory Barriers against Native Advertising,” in Blurring the Lines: Market-Driven and Democracy-Driven Freedom of Expression, Maria Edström, Andrew T. Kenyon, and Maria Svensson, eds., Göteborg, Sweden: Nordicom, 121–29.

- Taylor, Charles R. (2017), “Native Advertising: The Black Sheep of the Marketing Family,” International Journal of Advertising, 36 (2), 207–9.

- Teece, David J. (2010), “Business Models, Business Strategy, and Innovation,” Long Range Planning, 43 (2), 172–94.

- Teinowitz, Ira (2008), “Two Takes on Fixing ‘Broken’ Agency Model,” Advertising Age, 79 (15), 12.

- Trachtenberg, Jeffrey A. (2014), “Forbes Sold to Asian Investors—A Final End of Control for the Forbes Family, As Hong Kong Entrepreneurs Step In,” Wall Street Journal, July 19, p. 12.

- Turnbull, Sarah, and Colin Wheeler (2017), “The Advertising Creative Process: A Study of UK Agencies,” Journal of Marketing Communications, 23 (2), 176–94.

- Turow, Joseph (2011), Media Today: An Introduction to Mass Communication, New York, NY: Routledge.

- Van Alstyne, Marshall W., Geoffrey G. Parker, and Sangeet Paul Choudary (2016), “Pipelines, Platforms, and the New Rules of Strategy,” Harvard Business Review, 94 (4), 54–62.

- van Reijmersdal, Eva A., Marieke L. Fransen, Guda van Noort, Suzanna J. Opree, Lisa Vandeberg, Sanne Reusch, Floor van Lieshout, and Sophie C. Boerman (2016), “Effects of Disclosing Sponsored Content in Blogs: How the Use of Resistance Strategies Mediates Effects on Persuasion,” American Behavioral Scientist, 60 (12), 1458–74.

- Wang, Ruoxu, and Yan Huang (2017), “Going Native on Social Media: The Effects of Social Media Characteristics on Native Ad Effectiveness,” Journal of Interactive Advertising, 17 (1), 41–50.

- West, Douglas C. (1996), “The Determinants and Consequences of Multinational Advertising Agencies,” International Journal of Advertising, 15 (2), 128–39.

- ——, and Stanley J. Paliwoda (1996), “Advertising Client–Agency Relationships: The Decision‐Making Structure of Clients,” European Journal of Marketing, 30 (8), 22–39.

- Wirtz, Bernd W., Oliver Schilke, and Sebastian Ullrich (2010), “Strategic Development of Business Models: Implications of the Web 2.0 for Creating Value on the Internet,” Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 272–90.

- Wojdynski, Bartosz W. (2016), “The Deceptiveness of Sponsored News Articles: How Readers Recognize and Perceive Native Advertising,” American Behavioral Scientist, 60 (12), 1475–91.

- ——, Hyejin Bang, Kate Keib, Brittany N. Jefferson, Dongwon Choi, and Jennifer L. Malson (2017), “Building a Better Native Advertising Disclosure,” Journal of Interactive Advertising, 17 (2), 1–12.

- ——, and Nathaniel J. Evans (2015), “Going Native: Effects of Disclosure Position and Language on the Recognition and Evaluation of Online Native Advertising,” Journal of Advertising, 45 (2), 157–68.

- ——, and G.J. Golan (2016), “Native Advertising and the Future of Mass Communication,” American Behavioral Scientist, 60 (12), 1403–7.

- Xie, Quan, Marlene S. Neill, and Erin Schauster (2018), “Paid, Earned, Shared, and Owned Media from the Perspective of Advertising and Public Relations Agencies: Comparing China and the United States,” International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12 (2), 1–20.

- Yin, Robert K. (2003), Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Zott, Christoph, and Raphael Amit (2008), “The Fit between Product Market Strategy and Business Model: Implications for Firm Performance,” Strategic Management Journal, 29 (1), 1–26.

- ——, and —— (2010), “Business Model Design: An Activity System Perspective,” Long Range Planning, 43 (2), 216–26.

- ——, and —— (2013), “The Business Model: A Theoretically Anchored Robust Construct for Strategic Analysis,” Strategic Organization, 11 (4), 403–11.

- ——, and Lorenzo Massa (2011), “The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research,” Journal of Management, 37 (4), 1019–42.