Abstract

This study aims to contribute to the literature by examining how two opposite-valanced mechanisms (activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge and perceived transparency of the native advertising) explain positive and negative effects of sponsorship disclosures on brand responses (i.e., brand attitude and purchase intentions) and by examining the role of message source. An experiment (N = 133) showed that disclosures of native advertising decreased persuasion via activated persuasion knowledge: Readers who understood that a blog post was a form of advertising due to a disclosure showed more attitudinal-persuasion knowledge, which in turn led to less positive brand attitudes and lower purchase intention. However, the disclosure also enhanced persuasion via perceptions of transparency of the blog post: due to the disclosure, the blog post was perceived as more transparent, which resulted in less attitudinal-persuasion knowledge and in more positive attitudes toward the brand and higher purchase intentions. Source did not moderate these mediation effects. By incorporating two competing mechanisms, this study offers important new insights into the theoretical mechanisms that explain advertising disclosure effects.

Introduction

Blog posts are still very popular both among marketers and audiences, with 409 million monthly users worldwide (Parsons Citation2021; Sanders Citation2022). Blogs are the third most popular content marketing strategy for businesses (Bump Citation2021). Native advertising in blogs blurs the boundaries between editorial and commercial content and make it more difficult for consumers to recognize the persuasive attempt behind it (Cameron, Ju-Pak, and Kim Citation1996; Windels and Porter Citation2020; Wojdynski Citation2016). An example is an advertisement on a blogging platform that resembles noncommercial blogposts in terms of tone of voice, layout, and style, comparable to how advertorials are advertisements masked as editorial articles (Cameron, Ju-Pak, and Kim Citation1996).

Therefore, in many countries, advertisers are now obliged to disclose the advertising nature of these messages, which should help consumers to recognize the persuasive intent (Boerman et al. Citation2018, Federal Trade Commission Citation2015). The CARE model (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2020) posits two distinct paths by which consumers recognize that a native advertising message is in fact paid advertising. One is content driven, based on detection through elements of the content, such as brand prominence or bias. The second is disclosure driven, in which the message contains an element that explains or labels it as advertising.

When consumers recognize that a message is advertising because of a disclosure, they are likely to activate persuasion knowledge, and use this knowledge to critically evaluate the message (Eisend et al. Citation2020; Jung and Heo Citation2019). The effects of such disclosures on consumers’ responses appear to be inconsistent, in some part due to the fact that many consumers either never see them (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016) or at least cannot recall seeing them (Boerman, Willemsen, and Van Der Aa Citation2017). Studies have shown that those consumers who remember seeing the disclosure are more likely to recognize the content as paid advertising, and are also better able to recall the brand (Boerman, Van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Van Reijmersdal, Tutaj, and Boerman Citation2013; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016). However, consumers being able to detect that a native advertisement is actually a commercial message often comes at a price for advertisers, as such recognition results in heightened skepticism, negative brand attitudes, and lower purchase intentions (Boerman, Van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Evans et al. Citation2017; Guo et al. Citation2018; Kim, Masłowska, and Tamadonni, Citation2019; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016).

However, recent research also indicates that one key aspect of these disclosures may have positive effects, namely consumers’ perception of the sponsorship transparency of the native advertising (Beckert et al. Citation2020; Campbell and Evans Citation2018; Krouwer, Poels, and Paulussen Citation2020). This implies that disclosures can have negative effects on brand responses by virtue of the increased scrutiny that stems from activated persuasion knowledge, but they can also have positive effects via perceptions of transparency.

In the case of sponsored blog posts, which appear on a wide variety of blogging platforms, adherence to disclosure guidelines may be particularly low. One recent study of 200 blog posts on popular platforms found that while 65% of the posts mentioned a product, only 15% included a disclosure (Boerman et al. Citation2018). Given this disparity, consumers have to navigate blog posts with careful scrutiny, and search for both context cues, including the source of the blogpost, and disclosure cues to determine whether the post is an unbiased opinion or paid advertising, which makes them a great test case for examining the extent to which consumers “credit” bloggers for sponsorship transparency.

Furthermore, there is limited research investigating how the source of a sponsored message, that is a content-driven cue, interacts with the disclosure (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2020). A handful of studies focused on the effects of celebrities versus brands as sources of sponsored content (Bergkvist and Zhou Citation2016; Boerman, Willemsen, and Van Der Aa Citation2017). However, not only celebrities and brands engage in sponsored content, also noncommercial senders such as foundations, NGOs, or governments use branded content to communicate their messages (Boerman and Kruikemeier Citation2016). The present study examines the role of source (i.e., brand versus noncommercial source) in disclosure effects.

By incorporating two opposite-valanced mechanisms (activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge and perceived transparency of the native advertising) in one study and testing how these mechanisms affect attitudinal persuasion knowledge and eventually brand responses, this study offers important new insights into the theoretical mechanisms that explain effects of advertising disclosures on consumers. In addition, the study will offer valuable insights for advertisers and regulators concerned with advertising disclosures, as it not only focuses on negative effects of sponsorship disclosures but also on how these may benefit persuasion and enhance the transparency of the practice and whether these effects differ for commercial versus noncommercial sources.

Effects of Advertising Disclosures on Brand Responses in Blogs

So far, only a handful of studies have investigated the impact of disclosures in the context of blogs (see Campbell, Mohr, and Verlegh Citation2013; Hwang and Jeong Citation2016; Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015). Generally, these studies found direct negative effects of the presence of advertising disclosures in blogs on consumer’s brand attitudes (Campbell, Mohr, and Verlegh Citation2013; Hwang and Jeong Citation2016) and purchase intentions (Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund Citation2015). However, studies of advertising disclosures in other media formats have shown that the effectiveness of disclosures is heavily predicated on whether or not consumers notice the disclosure. For example, in the context of sponsored Facebook posts, 59% of participants who saw a sponsored post did not recognize the disclosure when shown a picture of it later (Boerman, Willemsen, and Van Der Aa Citation2017). Eye-tracking studies of sponsored news articles have shown that substantial portions of users never directly look at advertising disclosures and, of those that do, only a portion correctly recognize that the disclosure describes the content they are viewing as a paid message (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016; Wojdynski et al. Citation2017). Overall, the literature shows that effects of disclosures may hinge on their ability to make consumers aware of the sponsored nature of the content.

Besides, these studies have shown that when consumers are not aware of the commercial nature of the message, either because the sponsored content is not disclosed or because the disclosure is not remembered, they are inclined to have more positive brand attitudes because they tend to comply with what the message communicates (Campbell, Mohr, and Verlegh Citation2013). Consumers are expected to respond differently when native advertising is disclosed. There are several theoretical rationales that explain this reaction. The first is based on psychological-reactance theory (Brehm Citation1966), which explains that consumers want to retain their freedom and do not want to be manipulated or influenced by others. When their freedom is threatened, consumers respond negatively toward the source of the impediment.

Negative responses due to advertising disclosures, and the mechanisms behind them, can also be explained by the persuasion knowledge model (Friestad and Wright Citation1994). Advertising disclosures, when seen, tell consumers that they are viewing a paid persuasive message, which should activate consumers’ persuasion knowledge. Persuasion knowledge is a set of beliefs about persuasion motives and tactics that are used to cope with persuasion attempts from advertisers (Friestad and Wright Citation1994). For example, persuasion knowledge could be the understanding that a specific sponsored blog is a form of advertising instead of just a blog post. Several authors make a distinction between conceptual and attitudinal persuasion knowledge (Boerman, Van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Ham et al. Citation2022; Rozendaal et al. Citation2011). Conceptual persuasion knowledge refers to the cognitive aspects of persuasion knowledge, including the understanding and recognition of advertising. Advertising disclosures should help consumers recognize the persuasive nature of a message, so that consumers can distinguish between commercial content and noncommercial content which could consequently activate their attitudinal persuasion knowledge (e.g., Boerman, Van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Matthes and Naderer Citation2016; Van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016; Wojdynski Citation2016).

Attitudinal persuasion knowledge relates to the affective side of persuasion knowledge and comprises critical attitudes or feelings (i.e., skepticism and disliking) toward the persuasive message (Boerman, Van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016). Attitudinal persuasion knowledge is used to evaluate the persuasive attempt. Friestad and Wright (Citation1994) explain that when users activate their persuasion knowledge and apply it to their processing of a message, this can result in a “change of meaning” or different perceptions of the message’s intent. When a consumer recognizes the persuasive intent of a message (conceptual persuasion knowledge), it may make them feel deceived, and this awareness could result in critical feelings (attitudinal persuasion knowledge) toward native advertising (Boerman, Van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Wojdynski Citation2016).

We formulated a direct-effect hypothesis and a hypothesis about how we propose that conceptual and attitudinal persuasion knowledge will mediate the direct effects:

H1: An advertising disclosure (versus no disclosure) in a blog post will result in (a) negative brand attitudes and (b) lower purchase intentions.

H2: An advertising disclosure (versus no disclosure) will activate conceptual persuasion knowledge, that in turn results in more attitudinal persuasion knowledge, and in turn leads to (a) more negative brand attitudes and (b) lower purchase intentions.

Effects of Disclosures Through Transparency

Even though there is evidence that disclosures can result in negative brand responses, not informing consumers about the commercial nature of a message may result in even more critical and distrusting feelings toward the message (Boerman, Willemsen, and Van Der Aa Citation2017). Consumers do not appreciate it when the true nature of a message is withheld and they express emotions such as confusion and disappointment in discovering that the true purpose of a message was to persuade them (Wojdynski, Evans, and Hoy Citation2018). This raises the question whether effective disclosures in native advertising could also lead to greater perceptions of advertising transparency, and result in less activation of attitudinal persuasion knowledge and in turn less negative brand responses than a non-disclosed sponsored blog. Sponsorship transparency is defined as: “consumers’ perception of the degree to which a message makes its paid nature and the identity of the sponsor noticeable” (Wojdynski, Evans, and Hoy Citation2018, 118).

There is some evidence that consumers respond less negatively to paid blog posts that are more transparently disclosed. One study conducted by Hwang and Jeong (Citation2016) found that consumers responded less negatively toward a message when bloggers were honest about their blog and placed an “honest opinion” disclosure, than when bloggers placed no disclosure or a simple one. According to the discounting principle of attribution theory (Kelley Citation1973), people choose among different possible causes as explanations for an event or behavior (Baumeister and Vohs Citation2007; Kelley Citation1973). When applying this principle in the context of native advertising, it is likely that an advertisement that resembles a blog post with a disclosure could be attributed as honest, transparent, and being open about the intention of the message. This is because the consumer might not be aware that it was advertising instead of a blogpost and thus appreciate the honesty of the sender. Carr and Hayes (Citation2014) have demonstrated the impact of disclosures on perceptions of bloggers; they found that explicit disclosures of advertising and sponsoring resulted in higher credibility of the blogger and that consumers appreciated the honesty and openness of the blogger. More recent research by Krouwer, Poels, and Paulussen (Citation2020) showed that disclosures that were more explicit and detailed increased consumers perceptions that the advertising was more clearly or transparently conveyed (i.e., was higher in sponsorship transparency). This effect, in turn, positively affected attitudes toward the advertiser, the website, and the practice of native advertising. This suggests that higher levels of sponsorship transparency of a message lead to less activation of attitudinal persuasion knowledge because the consumer does not feel deceived (Abendroth and Heyman Citation2013). To test these effects in the case of an advertising masked as a blog post, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H3: An advertising disclosure (versus no disclosure) will result in higher perceived sponsorship transparency, that in turn results in less attitudinal persuasion knowledge, and in turn leads to (a) less negative brand attitudes, and (b) higher purchase intentions.

There is also some evidence in the literature for a link between conceptual persuasion knowledge and perceived sponsorship transparency. Evans, Wojdynski and Hoy (2019) found that when the message conveyed its advertising nature more transparently, sponsorship transparency mitigated the negative impact of advertising recognition (i.e., conceptual persuasion knowledge) on advertising and brand attitudes and resulted in higher purchase intentions. Similarly, and in the context of article-style native advertising, recent research by Campbell and Evans (2018) found that the negative effect of conceptual persuasion knowledge on brand attitudes, attitudes toward publishers, sharing intention, and credibility were mitigated as a result of increased sponsorship transparency. These findings indicate that disclosures trigger conceptual persuasion knowledge and, in doing so, also increase perceptions of sponsorship transparency. Therefore, under circumstances where a disclosure results in ad recognition, consumers may feel less deceived, and thus their evaluations may be less driven by reactance (Evans, Wojdynski, and Hoy Citation2019).

This would mean that the disclosure then not only enhances perceived transparency, but does so specifically, via activated conceptual persuasion knowledge. This leads to the fourth, competing hypothesis:

H4: A disclosure (versus no disclosure) in a blog post is more likely to activate higher levels of conceptual persuasion knowledge, which then leads to higher perceived sponsorship transparency, which in turn leads to less activation of attitudinal persuasion knowledge and, in turn, result in (a) less negative brand attitudes and (b) higher purchase intentions.

The Moderating Role of Source

Another important factor that determines the way consumers respond to (sponsored) messages is the message source. Prior research that examined the effects of sponsored content primarily examined whether persuasive messages communicated by influencers, such as celebrities, resulted in less resistance than persuasive messages communicated by brands themselves (e.g., Bergkvist and Zhou Citation2016; Boerman, Willemsen, and Van Der Aa Citation2017; Wood and Burkhalter Citation2014). According to the CARE model, people not only use disclosures but also content-driven cues such as the presence of a brand or the proximal source of the message (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2020). Both types of cues can result in the activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge and may affect perceived sponsorship transparency.

When the source of a blog post is a commercial brand (versus a government), the blog may evoke higher levels of conceptual persuasion knowledge and transparency, because the source is used as a cue to infer its persuasive nature. However, for a noncommercial source such as government, the disclosure may be needed to activate any persuasion knowledge or perceptions of sponsorship transparency. The main goal of governments is not commercial profit, but rather realizing a prosocial goal, such as improving health or safety. Therefore, a blog sponsored by a commercial party but communicated by the government may lead to less activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge than a message communicated by the brand itself.

As such, we expect the source to moderate the effects of disclosures on activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge and consequently attitudinal persuasion knowledge and persuasion, as well as on perceived transparency of the post and consequently attitudinal persuasion knowledge and persuasion.

More specifically, we expect the positive effects of disclosures on activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge and transparency to be stronger for blogs with a governmental source than for blogs with a commercial source. A blog from a brand without a disclosure is expected to activate more conceptual persuasion knowledge and perceived transparency than a blog from the government without a disclosure, because the commercial source (i.e., the brand) is used as a cue to activate persuasion knowledge. Therefore, the disclosure is expected to have a larger impact for the blog with a governmental source than a brand source.

Thus, we expect the hypothesized mediation effects to be moderated by source. This leads to the following moderated mediation hypotheses:

H5: The positive effects of disclosure via conceptual persuasion knowledge and attitudinal persuasion knowledge on( a) brand attitude and (b) purchase intent are stronger for a blog with a government as source, than for a blog with a brand as source.

H6: The positive effects of disclosure via perceived sponsorship transparency and attitudinal persuasion knowledge on (a) brand attitude and (b) purchase intent are stronger for a blog with a government as source than for a blog with a brand as source.

H7: The positive effects of disclosure via conceptual persuasion knowledge, perceived sponsorship transparency, and attitudinal persuasion knowledge on (a) brand attitude and (b) purchase intent are stronger for a blog with a government as source than for a blog with a brand as source.

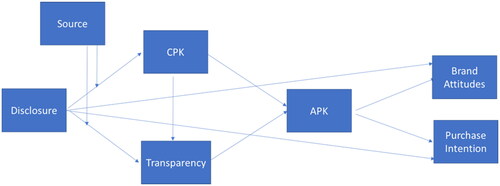

shows the conceptual model of this study.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Participants and Procedure

The research design was a 2 (disclosure: present vs. absent) × 2 (source: government vs. brand) between-subjects design. A total of 206 participants from The Netherlands were recruited through personal communication or from the university research pool. IRB approval was obtained for this study. Participants from the research pool were compensated with research credits. Most participants were female, 73.3% (N = 151). The average age of the participants was 23 years (SD = 5.78) and ranged between 18 and 61 years.

Once the participants agreed to participate in this study, they were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions (disclosure present, brand = 52, disclosure present, government = 52, disclosure absent, brand = 52, disclosure absent, government = 50). They were asked to carefully read a blog post regarding cycling safety. Then, they answered questions regarding the mediators and dependent variables. After the questionnaire, the participants were debriefed and thanked.

Stimulus Materials

The stimulus materials consisted of a fictive blog post about “the importance of bike lights.” In this blog, bicycle lighting was promoted. This topic was chosen because cycling is very popular in the country of study (Sibilski Citation2015). Especially in winter, when the days are short, cycling safety and bike lights are an important issue that is relevant for the target group (Duggan, Citationn.d.). The source consisted of the logo of the brand, or a logo of the government, that was shown above the blog. In all posts the brand AXA was mentioned twice, once at the beginning and once at the end of the blog.

We used an existing brand (AXA) and an existing logo of the government (ministry of justice and security) as sources in order to make the blog post as realistic as possible. The stimulus materials were kept identical across the conditions, only the disclosure and source of the blog were manipulated. The disclosure consisted of the text “this post is sponsored by AXA” and appeared underneath the title of the blog; in the no-disclosure condition, this text was omitted.

Measures

Conceptual persuasion knowledge was measured by asking participants (scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) to what extent they agreed with the statements: “The blog I read was advertising,” “The blog I read contained advertising,” and “The blog I read was sponsored” (Boerman, Van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016; Cronbach’s alpha = .83, M = 5.47, SD = 1.29).

Attitudinal persuasion knowledge toward the message was measured by asking participants to indicate (scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) to what extent they agreed that the blog they read was: dishonest, credible (reversed), trustworthy (reversed), unconvincing, and biased (Boerman, Van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Boerman, Willemsen, and Van Der Aa Citation2017; Cronbach’s alpha = .76, M = 3.31, SD = .96).

Based on a scale created by Wojdynski, Evans, and Hoy (Citation2018), sponsorship transparency was measured by asking participants to indicate (scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) to what extent they agreed with eight statements, for example: “It was unclear who paid for the blog” (reversed), “The blog made the name of the sponsor very obvious,” and “The blog was labelled as sponsored.” The items were taken together as one construct to measure the overall transparency of sponsorship disclosures (Wojdynski, Evans, and Hoy Citation2018; Cronbach’s alpha = .76, M = 4.38, SD = 1.05).

Brand attitude was measured using a 7-point semantic differential scale in which participants were asked to indicate to what extent they found the brand: unappealing vs. appealing, bad vs. good, unpleasant vs. pleasant, unfavorable vs. favorable, unlikable vs. likable, negative vs. positive, and low quality vs. high quality (Boerman, Van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Spears and Singh Citation2004; Cronbach’s alpha = .92, M = 4.87, SD = .90).

Purchase intention was measured by asking participants to indicate (scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) to what extent they agreed with the statements: “I will buy AXA bike lights in the near future,” “I will purchase AXA bike lights the next time I need lights for my bicycle,” and “I would definitely buy AXA bike lights” (Erkan and Evans Citation2016; Spears and Singh Citation2004; Cronbach’s alpha = .85, M = 3.27, SD = 1.33).

Several control variables were measured in order to ensure that the effects found were due to the disclosure and/or source, and not caused by other confounding variables. Besides age, gender, and education, brand familiarity and brand use were measured by asking participants if they knew the brand (55.8% no) and whether they used the brand (73.3% no). Moreover, attitude toward the source was measured by using the same semantic differential scale used to measure brand attitude (Cronbach’s alpha = .94, M = 4.67, SD = .99).

Furthermore, participants were asked to indicate (scale: 1 = never, 7 = always) how frequently they cycled (M = 4.40, SD = 1.68). And lastly, they were asked to what extent they agreed (scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) with the statement: “The blog I read was realistic” (M = 5.38, SD = 1.07).

As a measure of whether participants recalled the disclosure on the blog post (which was our manipulation), participants were asked if they saw any of the following texts in the blog (1 = This post is sponsored by AXA, 2 = This post was written in collaboration with gazelle bicycles, 3 = This post is an advertisement by AA Travel Insurance, 4 = None of the above).

Results

Randomization

Analysis of variance and chi-square analysis showed that there were no differences between the experimental groups with respect to gender, χ2 (6) = 11.87, p = .065; education, χ2 (6) = 3.53, p = .740; age, F(3, 202) = 2.697, p = .070; cycling frequency, F(3, 202) = 0.449, p = .718; brand familiarity, χ2 (3) = 1.70, p = .637; brand use, χ2 (3) = 0.61, p = .895; and blog realism, F(3, 202) = 0.663, p = .632. This means that the randomization was successful and none of the control variables were added in the analyses.

Manipulation Check

Of the participants in the disclosure-present condition, 45.2% recognized seeing the disclosure. These results are in line with earlier research, indicating that little attention is paid to advertising disclosures (Boerman, Willemsen, and Van Der Aa Citation2017). Most participants in the disclosure-absent condition correctly recognized that there was no disclosure (84.3%). In line with previous studies (Kruikemeiers, Szegin and Boerman Citation2016; Van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016), we will report the results for all participants but also for a subsample of those participants who correctly recalled the presence of the disclosure or correctly recalled the absence of such a disclosure, resulting in a subsample of 133 participants (disclosure present n = 47, disclosure absent n = 86). Levene’s test showed that the variances in persuasion knowledge are equal; thus, there is no violation of homogeneity due to unequal cell sizes, F (1, 131) = 1.13, p = .29.

Hypotheses

Effects of Disclosures on Brand Responses

All hypotheses were tested one-tailed (90% confidence intervals). To test hypothesis 1, a MANOVA was conducted with disclosure as the independent variable, and brand attitude and purchase intentions as dependent variables. For the total sample, there was no significant multivariate effect of disclosure on brand attitude and purchase intention, Wilks’ lambda = .033, F(2,203) = .055, p = .95. For the subsample of people who remembered seeing the disclosure, the MANOVA also yielded no significant multivariate effect of disclosure on brand attitude or purchase intent, Wilk’s lambda = 1.00, F(2, 130) = .28, p = .76. Thus, hypothesis 1 was rejected for both the total sample and the subsample. The results for the total sample and the subsample are visualized in and .

Effects of Disclosure via Conceptual and Attitudinal Persuasion Knowledge

To test hypotheses 2, 3, and 4, multiple regression analyses using PROCESS version 3.0 (model 6) were conducted, with disclosure as the independent variable, brand attitude or purchase intentions as the dependent variable, and conceptual persuasion knowledge, sponsorship transparency and attitudinal persuasion knowledge toward the message all included in the same analysis as mediators. This analysis provides a simultaneous test of all direct and indirect effects and of the relative strength of the indirect effects.

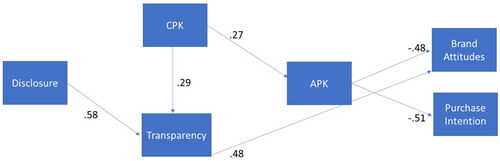

For the total sample, there was no indirect effect of disclosure via conceptual persuasion knowledge and attitudinal persuasion knowledge on brand attitude or on purchase intentions; see for all indirect effects. The disclosure did not activate conceptual persuasion knowledge, b = .13, SE = .18, t (204) = .74, p = .46, but conceptual persuasion knowledge did lead to more activation of attitudinal persuasion knowledge, b = .27, SE = .05, t(202) = 5.10, p < .001, and attitudinal persuasion knowledge led to less positive brand attitudes, b = −.48, SE = .06, t(201) = −7.94, p < .001 and lower purchase intentions, b = −.55, SE = .09, t(201) = −5.84, p < .001.

Table 1. Indirect effects of disclosures on brand attitude and purchase intent for the total sample.

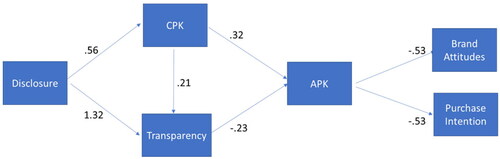

For the subsample, the analysis did yield a significant negative indirect effect of disclosure through conceptual and attitudinal persuasion knowledge on brand attitude, and on purchase intentions; see for all indirect effects. As expected, participants who were exposed to a disclosure activated higher levels of conceptual persuasion knowledge, b = .56, SE= .22, t(131) = 2.56, p = .012, which in turn resulted in more activation of attitudinal persuasion knowledge, b = .32, SE = .07, t(129) = 4.49, p < .001, and in turn resulted in more negative brand attitudes, b = −.53, SE = .08, t(128) = −7.03, p < .001, and lower purchase intentions, b = −.53, SE = .11, t(128) = −4.84, p < .001. This means that when participants remembered seeing the disclosure, it enhanced their recognition of the blog as being advertising, which led to more critical attitudes toward the blog and less positive brand attitudes and lower purchase intentions. Thus, hypotheses 2a and 2 b were not supported for the full sample, but they were supported for those who remembered seeing the disclosure.

Table 2. Indirect effects of disclosures on brand attitude and purchase intent for the subsample of people who correctly recalled the presence or absence of the disclosure.

Effects of Disclosure via Transparency and Attitudinal Persuasion Knowledge

With respect to H3, the analyses on the total sample showed no significant indirect effects of disclosures via transparency and then attitudinal persuasion knowledge on brand attitude or on purchase intentions, see for indirect effects. For the total sample, the disclosure did enhance transparency of the post, b = .58, SE = .13, t(203) = 4.46, p < .001. However, transparency was not related to attitudinal persuasion knowledge, b = −.10, SE = .07, t(202) = −1.46, p = .15. Interestingly, for the total sample there was a significant indirect effect of disclosure via transparency on brand attitude, b = .07, SE = .04, 90% CI [.01, .13], showing that a disclosure enhanced transparency, which resulted in more positive brand attitudes, b = .48, SE = .06, t (201) = −7.94, p < .001. This indirect effect was not significant for purchase intention b = .08, SE = .06, 90% CI [–.01; .17].

For the subsample of people who remembered seeing the disclosure, the analyses yielded a significant positive indirect effect of disclosure through transparency and attitudinal persuasion knowledge on brand attitude and purchase intentions; see . As expected, the blog post with a disclosure enhanced perceived transparency of the post, b = 1.32, SE = .15, t(130) = 8.71, p < .001, which in turn resulted in less activation of attitudinal persuasion knowledge, b = −.23, SE = .10, t(129) = −2.25, p = .026, that in turn resulted in less negative brand attitudes, b = −.53, SE = .08, t(128) = −7.03, p < .001 and higher purchase intentions, b = −.53, SE = .11, t(128) = −4.84, p < .001. This means that, for the total sample, hypothesis 3 was not supported, but for those who remembered seeing the disclosure hypothesis 3 is confirmed.

Effects of Disclosure via Conceptual Persuasion Knowledge, Transparency, and Attitudinal Persuasion Knowledge

With respect to H4, analyses on the total sample showed no significant indirect effect of disclosure via conceptual persuasion knowledge, transparency, and attitudinal persuasion knowledge in consecutive order on brand attitude or on purchase intent (see ). However, conceptual persuasion knowledge did lead to higher perceived transparency, b = .29, SE = .05, t(203) = 5.81, p < .001.

Analyses on the subsample, showed that for those who remembered seeing the disclosure, the disclosure had a significant indirect effect on brand attitude and on purchase intention via conceptual persuasion knowledge, transparency, and attitudinal persuasion knowledge consecutively; see . Conceptual persuasion knowledge enhanced transparency, b = .21, SE = .06, t(130) = 3.57, p < .005. This means that H4 is not confirmed for the total sample, but it is confirmed for the subsample of people who remembered seeing the disclosure.

Further analyses showed that the indirect effects of disclosures via conceptual persuasion knowledge and attitudinal persuasion knowledge versus the effect of disclosure via transparency and attitudinal persuasion knowledge were equally strong in the subsample for brand attitude, b = −.06, SE = .11, 90%CI [−.27; .09], and also for purchase intention, b = −.06, SE = .11, 90%CI [−.33; .12], but both indirect effects are stronger than the path through conceptual persuasion knowledge, transparency, and attitudinal persuasion knowledge (for brand attitude via conceptual persuasion knowledge and attitudinal persuasion knowledge, b = .08, se = .05, 90% CI [.02;.18], via transparency and attitudinal persuasion knowledge, b = .14, se = .10, 90% CI [.02;.35], for purchase intention via conceptual persuasion knowledge and attitudinal persuasion knowledge, b = .08, SE = .05, 90% CI [.01;.20], via transparency and attitudinal persuasion knowledge, b = .15, SE = .10, 90% CI [.01;.39].

Moderated Mediation Effects

To test H5, H6, and H7, a custom model was built for PROCESS, adjusting model 6 to include the moderation effects of source. None of the hypothesized mediated effects were moderated by source, neither for the total sample, nor for the subsample; see and for the moderated mediation indices. Interestingly, the effect of disclosure on transparency was moderated by source for the subsample (b = −0.61, SE = .29, t = −2.09; p = .04). Simple contrast analyses showed that for the subgroup without a disclosure, the post by AXA was perceived as more transparent (M = 4.27; SD = 0.13) than the post by the ministry (M = 3.91; SD = 0.13; F(1,129) = 4.01, p =.047). However, with a disclosure both posts were perceived as more transparent compared to a post without a disclosure (Mministry =5.63, SD = 0.19; F(1,129) = 55.59, p < .001; Mbrand = 5.45; SD = 0.16; F(1,129) = 32.37, p < .001) and the difference between the post of the two sources disappeared, F(1, 129) = 0.51, p < .48. This means that the disclosure leads to the same level of perceived transparency for a commercial or governmental source, whereas without the disclosure the fact that the brand is the source helps in transparency.

Table 3. Moderation mediation effects on brand attitude and purchase intent for the total sample.

Table 4. Moderated mediation effects on brand attitude and purchase intent for the subsample of people who correctly recalled the presence or absence of the disclosure.

Discussion

Our findings are an important addition to the sponsorship-disclosure literature. Until now, transparency had hardly been examined, leading to the conclusion that disclosures trigger negative and critical thinking about the blog, resulting in negative effects on brand responses (for overviews see Boerman and Van Reijmersdal Citation2016; Eisend et al. Citation2020). Our study shows that when perceived sponsorship transparency is taken into account, disclosures are actually beneficial for persuasion. This sheds a new light on the effects of disclosures on consumers’ processing of blogs. In addition, this study shows that the source of the sponsorship does not play a role in disclosure effects on persuasion through persuasion knowledge.

One important caveat with respect to the above findings relates to whether participants reported seeing a disclosure. Specifically, the significant indirect effects across the three different psychological pathways were present when the analyses included only individuals who were exposed to a disclosure and also recalled seeing it. This supports previous work contending that awareness or attention to the disclosure (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016) remains the key determinant of sponsorship-disclosure effects on conceptual persuasion knowledge. The current paper extends this line of thought and suggests that consumers attention to and memory of a disclosure in an advertisement masked as a blogpost may also affect the degree to which they feel such forms of advertising are clear or transparent in communicating their paid nature.

Limitations and Future Research

Future researchers should replicate this study with different kinds of sponsored blogs, posts, or messages (i.e., a more promotional or commercial message) and explore whether sponsorship transparency exerts similar effects in different contexts. It could be that more transparent disclosures in social media posts are perceived more positively than less transparent sponsorship disclosures. Most of the disclosures on social media are relatively small and sometimes even unnoticed by the consumer. In this vein, and in conjunction with different forms of sponsored or covert advertising, future work could explore how various disclosure characteristics (language, placement, prominence, duration, modality, etc.) affect perceptions of sponsorship transparency and subsequent cognitions, attitudes, and behaviors.

Beyond disclosures, future research could also explore the role of message characteristics (brand presence, bias, selling intent) and context-delivery characteristics (timing, congruity, perceived rationale) on the formation of sponsorship transparency. In this study, only one type and size of the brand has been used; thus, it is unclear what the impact of the perceived level of brand prominence in blog post is. It could be that consumer perceptions of brand prominence differentially impact perceptions of sponsorship transparency and conceptual persuasion knowledge.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study sheds light on existing and alternative psychological processes responsible for consumers’ evaluations and perceptions of obfuscated advertising messages. Perhaps most illuminating is the finding that supports more recent work on alternative pathways underlying psychological processes for evaluation or attitude formation (Campbell and Evans Citation2018; Wojdynski, Evans, and Hoy Citation2018). More specifically, sponsorship disclosures can trigger perceptions of transparency or honesty, which have benefits for consumers and advertisers alike. The findings indicate that, under circumstances where consumers remember seeing a disclosure, they are more likely to feel as though an advertisement masked as a blog was better in communicating to the viewer its nature and intention but without trying to hide it. Theoretically, this triggers less reactance and skepticism, and allows consumers to process and evaluate the communication without potentially feeling as though they have been deceived about its intention. When accounting for these specific psychological processes, the findings suggest that consumers feel more positively toward and are also more inclined to purchase brands featured in masked advertising in blogs. These implications are in line with and extend the propositions offered by Wojdynski and Evans’ (Citation2020) CARE model. Specifically, while disclosures and advertising recognition (i.e., conceptual persuasion knowledge) are paramount in the formation of attitudes and intentions toward a covert advertising message, the findings in the current study support the contention that resultant outcomes are positively impacted by sponsorship transparency.

In addition, our findings give more depth to the CARE model by showing that content-driven cues complement disclosures effects. Content cues seem to work in tandem and have cumulative effects on perceived transparency of a sponsored blog post.

Our findings also have practical implications. Practitioners, managers, and publishers of sponsored content, including but not limited to blogs, may help their bottom line if they successfully increase perceptions of sponsorship transparency in their advertising executions. This can be done by adding a disclosure as used in our study stating that the post is sponsored by brand X. Importantly, this study implicates that practitioners seeking to increase perceptions of transparency need to start with making sure that they are incorporating this information in ways that consumers are likely to see it. This study provides evidence that a recognized disclosure in a blog accomplishes multiple aims that include increased feelings of transparency, less skepticism, and more positive brand attitudes and purchase intention.

In addition, our findings imply that recognized disclosures add to other transparency cues, such as a commercial source. One may think that if the source of a post is a branded product, it is transparent, but for these posts disclosures are still helpful in increasing transparency about the nature of the post.

Conclusion

This study shows how disclosures in online blogs affect attitudinal and behavioral outcomes through three unique yet complimentary psychological pathways. Our findings indicate that for those who notice a sponsorship disclosure, the disclosure triggers conceptual persuasion knowledge, which in turn increases attitudinal persuasion knowledge regarding the messages, resulting in less positive brand attitudes and purchase intentions. This finding is consistent with findings from prior research on sponsored articles (e.g., Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016) and sponsored social media posts (Boerman, Willemsen, and Van Der Aa Citation2017), suggesting that overall perception or detection of a message’s commercial intent leads to negative outcomes for the promoted product in sponsored blogs as well.

Our second major finding indicates that a disclosure can increase consumers’ perceptions of sponsorship transparency, which in turn reduces attitudinal persuasion knowledge regarding the message and enhances brand attitudes and purchase intention. In other words, a disclosure can indirectly and positively influence purchase intention and brand-related attitudes when consumers feel as though the paid nature of the communication was clearly or transparently communicated.

Our third major finding indicates that, while conceptual persuasion knowledge is closely tied to and can positively affect transparency, attitudes and intentions are not solely impacted by the activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge; sponsorship transparency exerts force as well. The significant yet weak indirect effect of a disclosure via conceptual persuasion knowledge and sponsorship transparency on brand attitudes and purchase intent indicates that disclosures, when noticed, have a slightly greater effect on perceptions of sponsorship transparency than on the activation of conceptual persuasion knowledge.

Our fourth important finding is that source does not moderate the effects of disclosures on attitudes and intentions via persuasion knowledge or perceived transparency. This means that our findings hold regardless whether the source is a brand for a commercial product or whether the post comes from a government that does not have commercial motives. However, the disclosure enhanced perceptions of transparency for both sources to the same level, whereas without the disclosure the post from the brand was perceived as more transparent than the governmental post. Interestingly, even though a post from a commercial source maybe assumed to be transparent, we found that for participants who recognized the disclosure it did make the post more transparent.

References

- Abendroth, L. J., and J. E. Heyman. 2013. “Honesty Is the Best Policy: The Effects of Disclosure in Word-of-Mouth Marketing.” Journal of Marketing Communications 19 (4): 245–257.

- Baumeister, R. F., and K. D. Vohs. 2007. Encyclopedia of Social Psychology (Vol. 1). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Beckert, J., T. Koch, B. Viererbl, and C. Schulz-Knappe. 2020. “The Disclosure Paradox: How Persuasion Knowledge Mediates Disclosure Effects in Sponsored Media Content.” International Journal of Advertising 40 (7): 1160–1186.

- Bergkvist, L., and K. Q. Zhou. 2016. “Celebrity Endorsements: A Literature Review and Research Agenda.” International Journal of Advertising 35 (4): 642–663.

- Boerman, S. C., and S. Kruikemeier. 2016. “Consumer responses to promoted tweets sent by brands and political parties.” Computers in Human Behavior 65: 285–294.

- Boerman, S. C., and E. A. Van Reijmersdal. 2016. “Informing Consumers About “Hidden” Advertising: A Literature Review of the Effects of Disclosing Sponsored Content.” In Advertising in New Formats and Media: Current Research and Implications for Marketers, edited by P. De Pelsmacker, 115–146. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Boerman, S. C., N. Helberger, G. van Noort, and C. J. Hoofnagle. 2018. “Sponsored Blog Content: What Do the Regulations Say: And What Do Bloggers Say.” Journal of Intellectual Property, Information Technology, and Electronic Commerce Law 9 (2): 146–159.

- Boerman, S. C., E. A. Van Reijmersdal, and P. C. Neijens. 2012. “Sponsorship Disclosure: Effects of Duration on Persuasion Knowledge and Brand Responses.” Journal of Communication 62 (6): 1047–1064. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01677.x.

- Boerman, S. C., L. M. Willemsen, and E. P. Van Der Aa. 2017. “This Post is Sponsored’: Effects of Sponsorship Disclosure on Persuasion Knowledge and Electronic Word of Mouth in the Context of Facebook.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 38: 82–92. doi:10.1016/j.intmar.2016.12.002.

- Brehm, J. W. 1966. A Theory of Psychological Reactance. New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Bump, P. 2021. “31 Business Blogging Stats You Need to Know in 2021.” https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/business-blogging-in-2015

- Cameron, G. T., K. H. Ju-Pak, and B. H. Kim. 1996. “Advertorials in Magazines: Current Use and Compliance with Industry Guidelines.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 73 (3): 722–733. doi:10.1177/107769909607300316.

- Campbell, C., and N. J. Evans. 2018. “The Role of a Companion Banner and Sponsorship Transparency in Recognizing and Evaluating Article-Style Native Advertising.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 43: 17–32. doi:10.1016/j.intmar.2018.02.002.

- Campbell, M. C., G. S. Mohr, and P. W. Verlegh. 2013. “Can Disclosures Lead Consumers to Resist Covert Persuasion? The Important Roles of Disclosure Timing and Type of Response.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 23 (4): 483–495. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2012.10.012.

- Carr, C. T., and R. A. Hayes. 2014. “The Effect of Disclosure of Third-Party Influence on an Opinion Leader’s Credibility and Electronic Word of Mouth in Two-Step Flow.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 14 (1): 38–50. doi:10.1080/15252019.2014.909296.

- Duggan, J. n.d. “Why Bike Lights are Important…Even in Daylight.” https://www.active.com/cycling/articles/why-bike-lights-are-important-even-in-daylight?page=1

- Eisend, M., E. A. van Reijmersdal, S. C. Boerman, and F. Tarrahi. 2020. “A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Disclosing Sponsored Content.” Journal of Advertising 49 (3): 344–366. doi:10.1080/00913367.2020.1765909.

- Erkan, I., and C. Evans. 2016. “The Influence of eWOM in Social Media on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions: An Extended Approach to Information Adoption.” Computers in Human Behavior 61:47–55. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.003.

- Evans, N. J., J. Phua, J. Lim, and H. Jun. 2017. “Disclosing Instagram Influencer Advertising: The Effects of Disclosure Language on Advertising Recognition, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intent.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 17 (2): 138–149. doi:10.1080/15252019.2017.1366885.

- Evans, N. J., B. W. Wojdynski, and M. G. Hoy. 2019. “Sponsorship Transparency as a Mediator of Negative Effects of Covert Ad Recognition.” International Journal of Advertising 38 (3): 364–382. doi:10.1080/02650487.2018.1474998.

- Federal Trade Commission 2015. “Native Advertising: A Guide for Businesses.” https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/native-advertisingguide-businesses

- Friestad, M., and P. Wright. 1994. “The Persuasion Knowledge Model: How People Cope With Persuasion Attempts.” Journal of Consumer Research 21 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1086/209380.

- Guo, F., G. Ye, V. G. Duffy, M. Li, and Y. Ding. 2018. “Applying Eye Tracking and Electroencephalography to Evaluate the Effects of Placement Disclosures on Brand Responses.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 17 (6): 519–531. doi:10.1002/cb.1736.

- Ham, C. D., S. Ryu, J. Lee, U. C. Chaung, E. Buteau, and S. Sar. 2022. “Intrusive or Relevant? Exploring How Consumers Avoid Native Facebook Ads Through Decomposed Persuasion Knowledge.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 43 (1): 68–89. doi:10.1080/10641734.2021.1944934.

- Hwang, Y., and S. H. Jeong. 2016. “This is a Sponsored Blog Post, But All Opinions Are My Own’: The Effects of Sponsorship Disclosure on Responses to Sponsored Blog Posts.” Computers in Human Behavior 62: 528–535. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.026.

- Jung, A. R., and J. Heo. 2019. “Ad Disclosure vs. Ad Recognition: How Persuasion Knowledge Influences Native Advertising Evaluation.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 19 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/15252019.2018.1520661.

- Kelley, H. H. 1973. “The Processes of Causal Attribution.” American Psychologist 28 (2): 107–128. doi:10.1037/h0034225.

- Kim, S. J., E. Maslowska, and A. Tamaddoni. 2019. “The Paradox of (Dis) Trust in Sponsorship Disclosure: The Characteristics and Effects of Sponsored Online Consumer Reviews.” Decision Support Systems 116:114–124. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2018.10.014.

- Krouwer, S., K. Poels, and S. Paulussen. 2020. “Moving towards Transparency for Native Advertisements on News Websites: A Test of More Detailed Disclosures.” International Journal of Advertising 39 (1): 51–73. doi:10.1080/02650487.2019.1575107.

- Kruikemeier, S., M. Sezgin, and S. C. Boerman. 2016. “Political Microtargeting: Relationship Between Personalized Advertising on Facebook and Voters’ Responses.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking 19 (6): 367–372. doi:10.1089/cyber.2015.0652.

- Liljander, V., J. Gummerus, and M. Söderlund. 2015. “Young Consumers’ Responses to Suspected Covert and Overt Blog Marketing.” Internet Research 25 (4): 610–632. doi:10.1108/IntR-02-2014-0041.

- Matthes, J., and B. Naderer. 2016. “Product Placement Disclosures: Exploring the Moderating Effect of Placement Frequency on Brand Responses Via Persuasion Knowledge.” International Journal of Advertising 35 (2): 185–199. doi:10.1080/02650487.2015.1071947.

- Parsons, J. 2021. “Eight Reasons Why Blogging Is a Worthwhile Investment For Businesses.” https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2021/04/28/eight-reasons-blogging-is-a-worthwhile-investment-for-businesses

- Rozendaal, E., M. A. Lapierre, E. A. Van Reijmersdal, and M. Buijzen. 2011. “Reconsidering Advertising Literacy as a Defense against Advertising Effects.” Media Psychology 14 (4): 333–354. doi:10.1080/15213269.2011.620540.

- Sanders, K. 2022. “Are Blogs Still Relevant in 2022?” https://nealschaffer.com/are-blogs-still-relevant-in-2019/#:∼:text=Blogging%20is%20absolutely%20still%20relevant,in%20the%20last%205%20years

- Sibilski, L. 2015. “Why We Need to Encourage Cycling Everywhere.” https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/02/why-we-need-to-encourage-cycling-everywhere/

- Spears, N., and S. N. Singh. 2004. “Measuring Attitude Toward the Brand and Purchase Intentions.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 26 (2): 53–66. doi:10.1080/10641734.2004.10505164.

- Van Reijmersdal, E. A., M. L. Fransen, G. van Noort, S. J. Opree, L. Vandeberg, S. Reusch, F. Van Lieshout, and S. C. Boerman. 2016. “Effects of Disclosing Sponsored Content in Blogs: How the Use of Resistance Strategies Mediates Effects on Persuasion.” The American Behavioral Scientist 60 (12): 1458–1474. doi:10.1177/0002764216660141.

- Van Reijmersdal, E. A., K. Tutaj, and S. C. Boerman. 2013. “The Effects of Brand Placement Disclosures on Skepticism and Brand Memory.” Communications 38 (2): 127–146.

- Windels, K., and L. Porter. 2020. “Examining Consumers’ Recognition of Native and Banner Advertising on News Website Home Pages.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 20 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/15252019.2019.1688737.

- Wojdynski, B. W. 2016. “The Deceptiveness of Sponsored News Articles: How Readers Recognize and Perceive Native Advertising.” American Behavioral Scientist 60 (12): 1475–1491. doi:10.1177/0002764216660140.

- Wojdynski, B. W., and N. J. Evans. 2016. “Going Native: Effects of Disclosure Position and Language on the Recognition and Evaluation of Online Native Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 45 (2): 157–168. doi:10.1080/00913367.2015.1115380.

- Wojdynski, B. W., and N. J. Evans. 2020. “The Covert Advertising Recognition and Effects (CARE) Model: Processes of Persuasion in Native Advertising and Other Masked Formats.” International Journal of Advertising 39 (1): 4–31. doi:10.1080/02650487.2019.1658438.

- Wojdynski, B. W., H. Bang, K. Keib, B. N. Jefferson, D. Choi, and J. L. Malson. 2017. “Building a Better Native Advertising Disclosure.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 17 (2): 150–161. doi:10.1080/15252019.2017.1370401.

- Wojdynski, B. W., N. J. Evans, and M. G. Hoy. 2018. “Measuring Sponsorship Transparency in the Age of Native Advertising.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 52 (1): 115–137. doi:10.1111/joca.12144.

- Wood, N. T., and J. N. Burkhalter. 2014. “Tweet This, Not That: A Comparison between Brand Promotions in Microblogging Environments Using Celebrity and Company-Generated Tweets.” Journal of Marketing Communications 20 (1-2): 129–146.