Abstract

In 2002, the Dutch Euthanasia Act was put in place to regulate the ending of one’s life, permitting a physician to provide assistance in dying to a patient whose suffering the physician assesses as unbearable. Currently, a debate in the Netherlands concerns whether healthy (older) people who value their life as completed should have access to assistance in dying based on their autonomous decision making. Although in European law a right to self-determination ensues from everyone’s right to private life, the Dutch Supreme Court recently adopted a position on whether the Dutch Euthanasia Act lacks adequate attention to a patient’s autonomous decision making. Specifically, in the Albert Heringa case, the Court ruled that the patient–physician relationship as understood in the Dutch Euthanasia Act limits this plea for more self-determination. This ethical analysis of the Heringa case examines how the Supreme Court’s understanding of the Euthanasia Act defines patient autonomy within a reciprocal patient–physician relationship.

STATUTORY DUE CARE CRITERIA OF THE DUTCH EUTHANASIA ACT

In 2002, the Dutch Euthanasia Act () was put in place to regulate the ending of one’s life by a physician, at the patient’s request (van der Heide et al. Citation2007). This Act was developed in the context of searching for the proper balance between unbearable suffering for the patient, and the government’s duty to protect the lives of individual citizens.

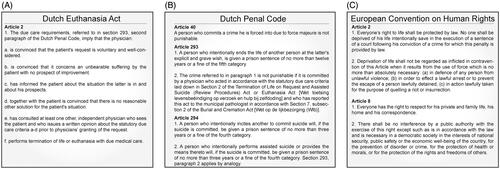

Figure 1. Applicable laws and regulations of the (A) Dutch Euthanasia act; (B) Dutch penal code; (C) European Convention on Human Rights.

Granting a patient’s request follows a physicians’ assessment of the following requirements: (1) the request is well-considered and voluntary, (2) the patient is suffering unbearably without any prospect of improvement, (3) the patient is informed about his situation and prospects, (4) there are no reasonable alternatives to relieve suffering, (5) an independent physician must be consulted by the treating physician to evaluate criteria 1–4 prior to physicians’ granting of the request, and (6) euthanasia is performed with due medical care and attention. Upon performing assisted death, physicians appeal to force majeure, a legal concept based on an emergency situation instigated by a conflict of duties: the physician’s duty to protect life is in conflict with the physician’s duty to relieve suffering. However, although the provision of assisted death is a violation of the criminal code, when it is performed in accord with the statutory due care criteria laid down in art. 2 of the Act (), it is not punishable (based on art. 293, section 2 of the Dutch Penal Code, ). For a physician to provide assistance in death in a way that meets the due care criteria is therefore regarded as legal.

DEBATE: “COMPLETED LIFE” OR “TIRED OF LIFE” EUTHANASIA REQUESTS

Currently, a debate in The Netherlands questions whether healthy (older) people, who value their life as completed, may be granted physician-performed assisted death (often called euthanasia) or may be granted assistance in self-administered death (often called physician-assisted suicide), which is not based on physicians’ assessment of the aforementioned six requirements (Florijn Citation2018). Proponents argue that the current Euthanasia Act should not be founded only on a physician’s conflict of duties, since if so it lacks attention to a patient’s autonomy (Heringa Citation2020). As such, Albert Heringa’s case for a self-directed death performed outside the physician–patient relationship is a profound challenge to requirements for physician-assisted death under the current Euthanasia Act. This challenge finds its origin in 1991, when a former vice-chairman of the Dutch Supreme Court, Huib Drion, published his account, “The self-willed end of old people.” Drion wrote, “Older people would find great peace of mind in the knowledge of having access to a way in which to say goodbye to life” (Drion Citation1991). The question Drion raised was intensified when Dutch national media in 2010 focused on the case of Albert Heringa, involving a non-physician (himself) providing assistance in suicide for his mother, 98-year-old Moek Heringa, because she viewed her life as completed and no longer worth living. In the television documentary “Moek’s Final Wish” [De laatste wens van Moek] (broadcast on Dutch television on February 8th, 2010), Albert Heringa was shown aiding in the suicide of his mother Moek Heringa (Dutch Right to Die Society 2010). Albert Heringa wrote about his experiences in a book of the same title, De laatste wens van Moek, published in 2013 (Heringa Citation2013).

Albert Heringa’s plea for the recognition of more self-determination and broader permissibility for assistance in suicide performed by non-physicians, has found support among increasing numbers of elderly Dutch people who also wish to have the option for assistance in ending life when they value their life as completed (Buiting et al. Citation2012). A survey among the Dutch general public demonstrated that 21% of those questioned (n = 1,960) agreed that the “completed life” or “tired of living” request for physician-assisted death should be allowed (Raijmakers et al. Citation2015). Although being “tired of living” is often a reason to request physician-assisted death (Rurup et al. Citation2005; Rurup et al. Citation2011), physicians in The Netherlands tend to refuse such requests in the absence of unbearable suffering rooted in a medical condition (Rurup et al. Citation2005; Rurup et al. Citation2011).

Recent Euthanasia Act evaluation data reported 280 cases of suicide by overdose in 2015 (Onwuteaka-Philipsen, et al. Citation2017). These cases were associated with psychiatric disorders (75%) and psychosocial or existential problems (24%) (Onwuteaka-Philipsen, et al. Citation2017). At the same time, the World Health Organization (WHO) data has shown a steady rise in cases of suicide in elderly people (O’Connell et al. Citation2004). In this context, the former Dutch government argued in 2014 that it is its duty to act with compassion when it concerns making allowances for the personal choices of people who consider their life as fulfilled and want to end their life in a well-considered way. However, in 2016, a multidisciplinary committee recommended there be no additional legal framework for assistance in death for (elderly) people because it could destabilize the current Dutch practice of physician-assisted death and instigate social pressure on elderly people (Schnabel, et al. Citation2016). Still, the Dutch government in 2016 argued that allowances for the personal choices of people who consider their life as fulfilled and want to end their life in a well-considered way should be made (Schippers and Steur van der Citation2016). The subsequent government (formed by the coalition of the political parties People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), Democrats 66 (D66) and Christian Union (CU) after the general election of 2017) ordered additional quantitative research intended to investigate the prevalence and nature of the death wish of healthy elderly people. Results from these studies demonstrated that the number of elderly people who value life as completed and who have an active death wish constitutes a modest proportion (10,000 ± 0.18%) of people above 55 years of age (van Wijngaarden Citation2020). With regard to their age, 2.2% of 65-year-old Dutch persons may have had a wish to die (Rurup et al. Citation2011), while another study among the European general population demonstrated that passive death wishes increases with age (of those 50–65 years of age, 5% have a passive death wish) (Ayalon and Shiovitz-Ezra Citation2011). Nonetheless, recently, a study among a representative sample of Dutch citizens aged 55 years and older (n = 32,477), demonstrated no significant overall difference in age distribution between those having a persistent death wish without severe illness (n = 267, 1.25%) and those without (Hartog et al. Citation2020). As such, an ongoing debate in The Netherlands remains centered around the question of whether the Dutch government should allow legal support for self-determination, that is increased patient autonomy within the Euthanasia Act and its practice.

ALBERT HERINGA CASE PRESENTATION

In 2008, Moek Heringa, then 98 years old, asked her son Albert Heringa to meet with her general practitioner (GP) because she wanted to request the physician’s assistance in dying. Moek Heringa had been previously diagnosed with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, osteoporosis, and macular degeneration. During this appointment, in February 2008, Moek informed her GP that she had become “tired of living” and considered her life complete. She asked her GP to prescribe additional medication for suicide by overdose, but her GP preferred not to move forward with this request because it was not an eligible request under the terms of the Dutch Euthanasia Act that regulates physician aid in dying. As a consequence, Moek felt abandoned by her GP (Heringa Citation2013). In April 2008, she asked her GP again to perform physician-assisted death. After the appointment, Moek and her GP agreed upon the discontinuation of medical treatment and initiated a palliative care phase. Again, in May 2008, Moek informed her GP explicitly that she felt tired of living and valued her life as completed.

Given his mother’s non-eligibility for euthanasia, as determined by her GP, Albert Heringa decided to assist Moek in suicide himself with a lethal dose of medication. Heringa supported his mother in her wish for death partly because he considered it unlikely other physicians would help her, given the Supreme Court ruling in the Brongersma case (Dutch Supreme Court 2012). Some of the medication necessary for assistance in suicide was already in Moek’s possession when she visited her GP in May 2008 but was further supplemented by Heringa because additional medication was needed to achieve a lethal dose. Heringa wrote a protocol with detailed instructions about the course of time at which medication should be taken as well. In June 2008, Heringa assisted Moek in performing suicide by giving her a mixture of Oxazepam, Temazepam, and Chloroquine tablets which she took by herself.

After the broadcast of the television documentary “Moek’s Final Wish” the Dutch public prosecutor accused Albert Heringa in 2010 of violating the prohibition of assisted suicide (art. 293 subsection 1 and art. 294 subsection 2, Penal Code, ). A lengthy series of court cases ensued over the next several years (2010–2019); subsequent legal court rulings (up to and including the Supreme Court) followed. [An account of these court rulings can be found in Supplemental Data 1].

AIMS OF THE ETHICAL ANALYSIS OF THE HERINGA CASE

This ethical analysis of the Albert Heringa case has a twofold aim. First, it highlights how the Supreme Court makes a dialogical proposal in which the physician–patient relationship is crucial in decision making for physician-assisted death in the Netherlands. Second, it demonstrates that the prohibition of assisted suicide, when provided by non-physicians, is not a violation of the right to self-determination (a right stipulated in art. 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR), particularly because the patient–physician relationship limits this right to self-determination. As such this analysis illustrates how the Albert Heringa case (with its plea for more self-determination and patient autonomy) in The Netherlands challenges both the validity and sustainability of the Dutch Euthanasia Act. This is because it aims for a practice of physician-assisted death in which patient autonomy and not only physician’s assessment of unbearable suffering determines whether healthy (older) people, who value their life as completed, should be granted physician-assisted death.

THE RULING OF THE SUPREME COURT, PART I: THE PHYSICIAN–PATIENT RELATIONSHIP IS INDISPENSABLE IN GUARANTEEING A PRACTICE OF DUE CARE IN PHYSICIAN-ASSISTED DEATH

Moek Heringa held that her request for physician-assisted death was not driven by unbearable suffering due to a medical condition alone; instead, for Moek Heringa, aging was accompanied by “a feeling that she would lose control of herself,” and “a fear of losing autonomy” (Heringa Citation2013, 42). Similar experiences for Dutch elderly people are “underlining their state of being unnecessary,” thereby making them feel unneeded and bothersome, “both side-tracked and getting in the way of others” (van Wijngaarden et al. Citation2019). Aging of, and age-related vulnerabilities in, elderly people from the Netherlands is threatening their sense of agency (van Wijngaarden, Leget, and Goossensen Citation2015). As such, aging places autonomy (“a self-perceived sense of a self-disciplined, independent and entrepreneurial agency”), dignity (“one’s capacities, behavior and ability to act competently”) and independence (“maintaining personal autonomy in respectful relationships with mutual recognition”) of elderly people at risk (van Wijngaarden, Goossensen, and Leget Citation2018). Currently, 1.34% (n = 76,000) of Dutch people above 55 years of age (n = 5,600,000), have a persistent death wish without being seriously ill, 0.77% (n = 43,000) have an active death wish and have considered suicide while 0.18% (n = 10,000) wish for assistance in suicide (van Wijngaarden Citation2020). Because “life had become too much for her” (Heringa Citation2013, 119), it could be argued that Moek Heringa’s request for physician-assisted death was largely existentially driven.

Background research in “tired of living” requests for physician-assisted death made by elderly people has shown that the inability to control one’s own life, due to the loss of autonomy, dignity, and independence, often leads to a decision about one’s own death. This comes in order to “claim the right to determine one’s own fate in response to the feeling that one loses the ability to do so” (van Tongeren Citation2018). As a consequence of these shifts in public attitudes, it has been argued that the moral basis within the public attitude for granting physician-assisted death in the Netherlands is moving towards more patient autonomy instead of physicians’ conflict of duties (Kouwenhoven et al. Citation2019). This trend is particularly felt in the current practice of physician-assisted death. Instead of their assessment of the criteria for due care in carrying out physician-assisted death, physicians face a trend towards more attention from patients and relatives for negative patient autonomy (i.e., freedom from external interference). This, in turn, it is argued, is making the physician’s role largely instrumental for obtaining physician-assisted death (Kouwenhoven et al. Citation2019)—“instrumental” because it could obviate the contribution of the physician in the patient’s decision about what to do.

This trend is also reported in results from a recent study with a focus on the role of the physician in the Dutch practice of physician-assisted death. In this qualitative study among 28 Dutch physicians with experience of complex cases of physician-assisted death, the physicians themselves often mentioned the “ease with which the position of the physician is overlooked” (Snijdewind et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, in a qualitative interview study into the experiences of Dutch GPs with physician-assisted death requests from persons with dementia, GPs (n = 11) reported difficulties with pressure from relatives and society’s negative view of dementia in combination with the “right to die” view.

In the Albert Heringa case, the Supreme Court quotes, in contrast to a societal trend that favors more negative autonomy in physician-assisted death decision making, the Explanatory Memorandum of the Euthanasia Act. In this Memorandum, it was stated that the decision-making process, upon a request for physician-assisted death, should be a case of the physician and the patient working together. In fact, when there is no other solution for the patient, “the consultation between the physician and the patient is vital.” Nevertheless, the consultation expressed in this requirement does not affect the independent decision of the physician and his exclusive responsibility for physician-assisted death upon request. As such, non-punishability and the associated due care requirements are “exclusively related to the performance of physician-assisted death by physicians” (Dutch Supreme Court 2017). The Supreme Court further ruled that in the Netherlands, physician-assisted death (art. 293 subsection 1 Penal Code) and assisted suicide (art. 294 subsection 2 Penal Code) are not punishable when performed by a physician in accordance with the due care criteria, as laid down in art. 2 of the Euthanasia Act (). However, in euthanasia cases, it is only physicians who can invoke force majeure based on an emergency situation (art. 293 subsection 2 Penal Code, ). Because acting in an emergency situation implies acting contrary to the Penal Code, (non-)physicians can invoke force majeure only in exceptional cases when a justified choice between mutually conflicting duties and interests has been made and meets the proportionality and subsidiarity criteria (Bleichrodt 2018). In Heringa’s case, the Supreme Court held that invoking force majeure by a non-physician can be accepted in exceptional cases only because the legislator has provided for a special and specific statutory due care criterion that is limited to the acts of physicians, and that criterion is closely related to the expertise, as well as the standards and ethics of the medical profession.

Given that the Supreme Court ruled that the decision-making process, following a request for physician-assisted death, relies on a vital consultation within the patient–physician relationship, physicians must conduct this consultation by informing patients about their situation and prospects. Further, the physician and the patient should decide together whether physician-assisted death is proportional (i.e., the interest served by committing the offense must, by objective standards, outweigh the interest affected by the violation of the criminal law) when there is, within reason, no other acceptable solution to alleviate the patient’s suffering other than to end the patients’ life. The due care criteria of the Euthanasia Act () requires that the patient’s request should not only be voluntary but also well-considered. According to the Code of Practice for physician-assisted death in the Netherlands, well-considered constitutes a careful assessment of one’s case on the basis of sufficient information and a clear insight into illness (Regional Euthanasia Review Committees Citation2018).

It has been argued that this implies that “the person submitting a request must be someone who has thought a lot about how he wants to die and when, and knows what is reasonable for himself and his environment, when the time to die has come and when not” (Kennedy Citation2002, 141). Given that this well-considered nature of the request is included in the due care criteria of the Euthanasia Act, the Dutch practice of physician-assisted death particularly centers around “the socially integrated, responsible person” (Kennedy Citation2002, 141). Such responsibility is expected from the patient who foresees the outcome of the request and “acknowledges that fellow human beings (i.e., the physician) are also responsible” for the request from the patient (Weyers Citation2004, 80). These mutual responsibilities in the decision-making process following a request for physician-assisted death, from both the physician and the patient, point toward a patient–physician relationship model which has been called the “deliberative model.” In this model, the physician and patient “engage together in a dialogue about what course of action would be best” (Emanuel and Emanuel Citation1992). With regard to physician-assisted death, patients are supposed to take into account their responsibility to others (i.e., such as relatives) when making end-of life decisions. This deliberative model between patient and physician has been considered “a form of attentiveness; “namely the ability to sense the demands of an individual person at a particular moment, and to respond to those demands in an appropriate manner” (Gadamer Citation1996, 138).

In sum, given the above, it can be concluded that instead of individual, negative patient autonomy, that is, self-determination in physician-assisted death, the Supreme Court puts emphasis on the fact that the Euthanasia Act uses a type of “relational” autonomy in physician-assisted death decision-making (Gomez-Virseda, de Maeseneer, and Gastmans Citation2019). This type of autonomy consists of a vital physician–patient relationship that is meant to guarantee a practice of due care in carrying out physician-assisted death. Physicians guarantee whether the request for physician-assisted death is well-considered and voluntary by being open to patient narratives and ideas of self and personal identity, because “the lack of a language one can trust to make sense of one’s experiences ultimately leads to a lack of self-understanding” (Sveneaeus Citation2018). Furthermore, physicians inform patients about their situation and prospects and assess whether there are no reasonable alternatives to relieve suffering. This suggests physicians have a role in enhancing patients’ autonomy in their decision making for physician-assisted death, in a practice of “interpretation through dialogue in service of the patient’s health” (Florijn et al. Citation2019; Sveneaeus Citation2018). Only this model, in which the physician and patient engage together in a dialogue, guarantees a safe practice of physician-assisted death and allows physicians to invoke force majeure upon performing physician-assisted death.

THE RULING OF THE SUPREME COURT, PART II: ASSISTED SUICIDE AND THE EUROPEAN CONVENTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS

In 2002, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) decided that the protection of life in article (art.) 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECtHR) cannot “be interpreted as conferring the diametrically opposite right, namely a right to die; nor can it create a right to self-determination in the sense of conferring on an individual the entitlement to choose death rather than life” (European Court of Human Rights Citation2002). Therefore, art. 2 ECtHR only holds positive obligations for European Union (EU) member states to protect life, and not the obligation to decriminalize physician-assisted death. However, the ECtHR stipulates in art. 8 that “everyone has the right to receive respect for his private and family life” (). Based on art. 8, the ECHR has ruled that notions of the quality of life take on significance, particularly nowadays. In an era of “growing medical sophistication, combined with longer life expectancies, many people are concerned that they should not be forced to linger on in old age or in states of advanced physical or mental decrepitude which conflict with strongly held ideas of self and personal identity” (European Court of Human Rights Citation2002). From this, according to the ECHR, personal autonomy and a right to self-determination ensue from everyone’s right to a private life (European Court of Human Rights Citation2002). This implies, according to the ECHR, that an individual has a “right to decide by what means and at what point his or her life will end, provided he or she is capable of freely reaching a decision on this question and acting in consequence” (European Court of Human Rights Citation2011). However, because there is no consensus amongst EU Member States as to what extent an individual is entitled to decide at what point, and by what means, his or her life should be ended, and given the different interests to be considered in this respect (the protection of the right to live against the protection of the right to self-determination), the ECHR argued there is a wide “margin of appreciation” on this issue. (The margin of appreciation is a doctrine developed by the ECHR to judge whether an EU member state should be sanctioned for limiting the enjoyment of rights. It allows the Court to reconcile practical differences in implementing the articles of the Convention and creates the possibility for EU member states “to derogate from the obligations laid down in the Convention”) (European Court of Human Rights Citation1958).

In the Netherlands, physician-assisted death is only allowed under the conditions specified in art. 293 subsection 2 Penal Code. This particular article is a margin of appreciation which is used by the Dutch government “to prevent misuse of assistance with suicide and to protect incapacitated and vulnerable persons” (Dutch Court of Appeal’s-Hertogenbosch Citation2018). According to the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court, the Heringa case failed to recognize that this margin of appreciation of an EU member state will be allowed to determine in which cases to make an exception to a prohibition on assisted suicide. Therefore, it has been argued that the aforementioned ECHR court rulings are not applicable in the Heringa case because they concern situations that fall outside the scope of the Euthanasia Act (Schnabel, et al. Citation2016). The Act formulates due care requirements for physicians but does not delineate patients’ rights, which makes the Act aligned with art. 8 ECHR (Schnabel, et al. Citation2016). Albert Heringa however, favored the opposite view, according to the Court of Appeal, which argued that Heringa was led by his own ideas about self-determination, and life and death, which were “widely accepted but insufficiently presented in current legislation.” Instead, Albert Heringa should have used the possibility of “trying to persuade Moek Heringa to discuss her death wish with other consulting physicians” despite the fact that her GP was reluctant to carry out her request for physician-assisted death. In this approach, the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court confirmed that the current Euthanasia Act has limited the right to self-determination (as laid down in art. 8 ECHR) with the requirement that a physician can only invoke force majeure when it concerns unbearable suffering rooted in a medical condition (Florijn Citation2018). This requirement allows physicians alone to assess unbearable suffering and tries to ensure that their performance of physician-assisted death guarantees a minimum likelihood of complications and adequate medical action in the event of unexpected complications. In contrast, Albert Heringa acted as non-physician which, according to the District Court, could have harbored risks of complications. Albert Heringa accepted these risks, despite his thorough preparations.

Collectively, the aforementioned ruling states that the prohibition of assisted suicide by non-physicians is not a violation of the patient’s right to self-determination (as laid down in art. 8 ECHR). On the contrary, the Dutch margin of appreciation (as laid down in art. 2 Euthanasia Act and art. 293 section 2) makes use of a vital patient–physician relationship that allows a safe and due care assessment of unbearable suffering in response to a well-considered request for physician-assisted dying.

CONCLUSION

The Supreme Court has argued in the Albert Heringa case that instead of autonomous decision making in physician-assisted death, a vital, reciprocal patient–physician relationship alone constitutes a justified limitation of a plea for more self-determination in physician-assisted death. This physician–patient relationship allows for a practice of due care in physician-assisted death based on the due care criteria as laid down in art. 2 of the Euthanasia Act. As such the Supreme Court has emphasized that the Albert Heringa case (with its plea for more self-determination and patient autonomy based on art. 8 of the ECHR) does not put aside the due care requirements of the Dutch Euthanasia Act for physician-assisted death. These statutory due care criteria enable a due care assessment of unbearable suffering by physicians in response to a well-considered request from the patient. Furthermore, with their ruling in the Albert Heringa case, the Supreme Court states that these statutory due care criteria are not a violation of the right to self-determination as stipulated by art. 8 of the ECtHR. As such, the physician–patient relationship is predominantly present in the due care criteria to enable a well-functioning and safe euthanasia practice (Florijn Citation2018). Therefore, physician’s assessment of unbearable suffering cannot be omitted following the “completed life” or “tired of living” request for physician-assisted death.

uajb_a_1863510_sm6445.docx

Download MS Word (20.4 KB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to thank H.A.M. Weyers for her comments on the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The author reports no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ayalon, L., and S. Shiovitz-Ezra. 2011. The relationship between loneliness and passive death wishes in the second half of life. International Psychogeriatrics 23 (10):1677–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610211001384.

- Bleichrodt, F. W. 2018. ECLI:NL:HR:2019:598.

- Buiting, H. M., D. J. H. Deeg, D. L. Knol, J. P. Ziegelmann, H. R. W. Pasman, G. A. M. Widdershoven, and B. D. Onwuteaka-Philipsen. 2012. Older peoples’ attitudes towards euthanasia and an end-of-life pill in The Netherlands: 2001-2009. Journal of Medical Ethics 38 (5):267–73.

- Drion, H. 1991. The self-willed end of older people. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: NRC Handelsblad.

- Dutch Court of Appeal’s-Hertogenbosch. 2018. ECLI:NL:GHSHE:2018:345.

- Dutch Right to Die Society. 2010. Moek’s final wish. Accessed July 15, 2019. http://www.thisistheend.nl/watch-online/moeks-final-wish-2010/

- Dutch Supreme Court. 2012. Brongersma NJ 2003, 167.

- Dutch Supreme Court. 2017. ECLI:NL:HR:2017:418.

- Emanuel, E. J., and L. L. Emanuel. 1992. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA 267 (16):2221–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03480160079038.

- European Court of Human Rights. 1958. Case of Greece versus United Kingdom. Application no. 176/56.

- European Court of Human Rights. 2002. Case of Pretty versus United Kingdom. Application no. 2346/02.

- European Court of Human Rights. 2011. Case of Haas versus Zwitserland. Application no. 31322/07.

- Florijn, B. W. 2018. Extending euthanasia to those ‘tired of living’ in the Netherlands could jeopardize a well-functioning practice of physicians’ assessment of a patient’s request for death. Health Policy 122 (3):315–9.

- Florijn, B. W., H. V. der Graaf, J. W. Schoones, and A. A. Kaptein. 2019. Narrative medicine: A comparison of terminal cancer patients’ stories from a Dutch hospice with those of Anatole Broyard and Christopher Hitchens. Death Studies 43 (9):570–81.

- Gadamer, H. G. 1996. The enigma of health. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gomez-Virseda, C., Y. de Maeseneer, and C. Gastmans. 2019. Relational autonomy: What does it mean and how is it used in end-of-life care? A systematic review of argument-based ethics literature. BMC Medical Ethics 20:76.

- Hartog, I. D., M. L. Zomers, G. J. M. W. van Thiel, C. Leget, A. P. E. Sachs, C. S. P. M. Uiterwaal, V. van den Berg, and E. van Wijngaarden. 2020. Prevalence and characteristics of older adults with a persistent death wish without severe illness: A large cross-sectional survey. BMC Geriatrics 20 (1):342.

- Heringa, A. 2013. De laatste wens van moek. Maassluis, The Netherlands: Uitgeverij De Brouwerij.

- Heringa, A. 2020. Bij voltooid leven wil je niet afhankelijk zijn van artsen. Accessed February 02, 2020. https://www.trouw.nl/opinie/bij-voltooid-leven-wil-je-niet-afhankelijk-zijn-van-artsen∼b98c48d8/

- Kennedy, J. 2002. Een weloverwogen dood. Euthanasie in Nederland. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Uitgeverij Bert Bakker.

- Kouwenhoven, P. S. C., G. J. M. W. van Thiel, A. van der Heide, J. A. C. Rietjens, and J. J. M. van Delden. 2019. Developments in euthanasia practice in the Netherlands: Balancing professional responsibility and the patient’s autonomy. European Journal of General Practice 25 (1):44–8.

- O’Connell, H., A.-V. Chin, C. Cunningham, and B. A. Lawlor. 2004. Recent developments: Suicide in older people. BMJ 329 (7471):895–9.

- Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D., Legemaate, J., van der Heide, A., Evenblij, K., El Hammoud, I., Pasman, H. R. W., Ploem, C., Pronk, R., van de Vathorst, S. et al. 2017. Derde evaluatie Wet toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding. Den Haag, The Netherlands: ZonMw.

- Raijmakers, N. J. H., A. van der Heide, P. S. C. Kouwenhoven, G. J. M. W. van Thiel, J. J. M. van Delden, and J. A. C. Rietjens. 2015. Assistance in dying for older people without a serious medical condition who have a wish to die: A national cross-sectional survey. Journal of Medical Ethics 41 (2):145–50.

- Regional Euthanasia Review Committees. 2018. Euthanasia code. The Hague, The Netherlands: RERC.

- Rurup, M. L., D. J. H. Deeg, J. L. Poppelaars, A. J. F. M. Kerkhof, and B. D. Onwuteaka-Philipsen. 2011. Wishes to die in older people: A quantitative study of prevalence and associated factors. Crisis 32 (4):194–203.

- Rurup, M. L., B. D. Onwuteaka-Philipsen, M. C. Jansen-van der Weide, and G. van der Wal. 2005. When being ‘tired of living’ plays an important role in a request for euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide: Patient characteristics and the physician’s decision. Health Policy 74 (2):157–66.

- Schippers, E. I., and G. A. Van der Steur. 2016. Kabinetsreactie en visie Voltooid Leven. Tweede Kamer, vergaderjaar 2016–2017, 32 647, nr. 55. Den Haag, The Netherlands.

- Schnabel, P., Schabel P, Meyboom-de Jong B, Schudel WJ, Cleiren CPM, Mevis PAM, Verkerk MJ, van der Heide A, Hesselman G, Stultiëns. 2016. Voltooid leven: Over hulp bij zelfdoding aan mensen die hun leven voltooid achten. [Completed Life: On Assisted Suicide to People WhoConsider Their Lives Complete]. Den Haag, The Netherlands: Adviescommissie Voltooid Leven.

- Snijdewind, M. C., D. G. van Tol, B. D. Onwuteaka-Philipsen, and D. L. Willems. 2018. Developments in the practice of physician-assisted dying: Perceptions of physicians who had experience with complex cases. Journal of Medical Ethics 44 (5):292–6.

- Sveneaeus, F. 2018. Phenomenological bioethics: Medical technologies, human suffering, and the meaning of being alive. New York, NY: Routlegde.

- van der Heide, A., B. D. Onwuteaka-Philipsen, M. L. Rurup, H. M. Buiting, J. J. M. van Delden, J. E. Hanssen-de Wolf, A. G. J. M. Janssen, H. R. W. Pasman, J. A. C. Rietjens, C. J. M. Prins, et al. 2007. End-of-life practices in the Netherlands under the Euthanasia Act. The New England Journal of Medicine 356 (19):1957–65.

- van Tongeren, P. 2018. Willen sterven: Over de autonomie van het voltooide leven. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Uitgeverij Kok.

- van Wijngaarden, E. 2020. Perspectieven op ouderen met een doodswens zonder dat zij ernstig ziek zijn: De mensen en de cijfers. Den Haag, The Netherlands: ZonMw.

- van Wijngaarden, E., A. Goossensen, and C. Leget. 2018. The social-political challenges behind the wish to die in older people who consider their lives to be completed and no longer worth living. Journal of European Social Policy 28 (4):419–29.

- van Wijngaarden, E., C. Leget, and A. Goossensen. 2015. Ready to give up on life: The lived experience of elderly people who feel life is completed and no longer worth living. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 138:257–64.

- van Wijngaarden, E., C. Leget, A. Goossensen, R. Pool, and A.-M. The. 2019. A captive, a wreck, a piece of dirt: Aging anxieties embodied in older people with a death wish. Omega 80 (2):245–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222817732465.

- Weyers, H. 2004. Euthanasie. Het proces van rechtsverandering. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.