ECMO is a short-term measure providing temporary life support until resolution of the primary insult or transplantation. Thanks to technological advances in life support, its use has increased enormously over the past three decades, with less than 2,000 cases in the early 1990s to more than 20,000 in 2021 (www.elso.org; Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) Citation2023). Although ECMO requires a minimum level of sedation and analgesia, there is a growing interest to maintain patients awake with spontaneous breathing. Recent studies support such a strategy pointing to a positive impact on post-ECMO recovery and survival (Crotti Citation2017). Arguments in favor of keeping patients awake on ECMO include a reduced incidence of delirium, early mobilization, improved rehabilitation, and the promotion of interactions with families and clinicians (Langer Citation2016). By contrast, awake patients may experience discomfort, are exposed to increased risks of device displacement, and may develop patient self-induced lung injury (P-SILI) in case of elevated respiratory drive.

Currently, awake ECMO concerns only a minority of patients, as indicated in a recent multicenter analysis of 197 COVID-19 patients supported by veno-venous ECMO, which included 17 (8.6%) awake patients (Makhoul Citation2023). Among awake ECMO patients, a minority will neither recover nor be a candidate for transplantation (Langer Citation2016). We may assume that a proportion of them will have decisional capacity and may request the continuation of life-sustaining treatment. Although these represent only a small minority of all ECMO patients, their number may increase in years to come, challenging the ethical considerations regarding ECMO continuation for capacitated patients as a “bridge to nowhere”.

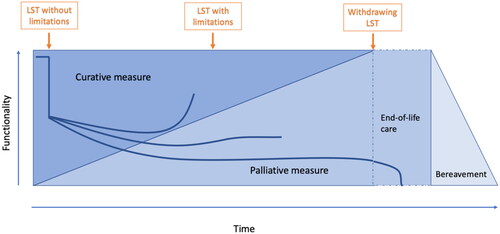

The so-called “bridge to nowhere” has in fact a destination; it is the reorientation of care to palliative measure. Palliative care (PC) in the intensive care unit (ICU) has been shown to be an effective integrative approach (Curtis et al. Citation2022). PC focuses on symptoms management, psycho-socio-spiritual support, goals-of-care conversations and advance care planning. All of these issues are particularly relevant to capacitated patients on ECMO, especially in the absence of any potential for recovery or transplantation. Addressing PC needs in the ICU reduces physical and psycho-socio-spiritual burden for patients and their families and improves end-of-life care (Metaxa Citation2021). In a descriptive study of patients with COVID-19 receiving ECMO, Siddiqui et al. (Citation2023) showed that early integration of PC helps patients and families better understand the complexity of ECMO therapy, its benefits, and its limitations. It also helps clinicians discuss goal-concordant care, which aims to align treatment decisions with the patient’s preferences. Concurrent intensive and palliative care is challenging as is early integration of PC in other medical domains. It should begin early and be responsive to the acute changes in the health state (). However, this model offers unique opportunities for goals-concordant care conversations, as well as advance care planning to prepare the end of life.

Figure 1. Early integration of palliative care in the intensive care unit for patient with life-sustaining treatment (LST), adapted from Murray Citation2005.

For the few capacitated patients who wish to continue ECMO, we argue that ECMO can be used as a palliative measure with significant ethical value. In the context of goals-of-care conversations, the ICU team is dedicated to respecting the patients’ own values and their definition of quality of life, whether it could be surviving until the birth of a child or using the remaining time to accomplish unfinished tasks in life. The qualitative form of medical futility is co-defined by the patients themselves, since it depends on their perception of harms and risks caused by the treatment versus the benefit they personally gain from staying alive (Schneiderman Citation2011). Healthcare professionals may be uncomfortable accepting such a treatment based on their own conception of quality of life, which may be different from that of the patient. They may also invoke quantitative futility, pointing to the fact that ECMO cannot effectively maintain life in the long run. How long should they commit to maintain a patient under artificial measure in the ICU? How far should they engage to correct technical failures and complications related to ECMO therapy?

We invite clinicians to consider a paradigm shift. In such situations as presented above, the goal of care is no longer to extend life until recovery or organ transplantation. Instead, the goal of ECMO in these situations can be to attain a sufficient quality of life, even if this is only for a limited period before death. ECMO is a life-sustaining technology that, more than any other form of assistance, allows clinicians to go beyond the limits of organ viability and survival. Yet, ECMO therapy is also associated with unavoidable severe complications (thrombo-embolic, hemorrhagic, infectious), jeopardizing the patient’s consciousness and survival (Combes Citation2018). As any other life-sustaining treatment, it can increase quantity and quality of life but ultimately does not exempt from death. We face similar challenges regarding artificial nutrition or hydration for terminally ill patients. In such challenging cases, it may be beneficial and respectful to offer a delay, value its temporality, and support patients and families in their highly personal end-of-life process. While maintaining ECMO treatment, withholding treatment of future complications may be seen as more proportionate for awake patients on ECMO that withdrawing ECMO.

Our approach raises the issue of distributive justice. A patient on palliative ECMO will use important scarce resources in terms of technology, personnel, and cost. It can be argued that a patient on ECMO as bridge to organ transplantation also uses major resources, especially considering organ scarcity. Although their clinical trajectory will differ drastically, they share some similarities. Both were initially placed on ECMO as candidates for recovery or transplant. Both wish to prolong their lives. For sure, organ transplantation, while bearing its own risks, has the potential to prolong life significantly longer and lead to a certain recovery of health and functional status. Yet, it is ethically problematic to allocate scarce resources by comparing the values of different lives. A life sustained for a shorter time may not necessarily be less valuable than a life sustained for a longer time. Moreover, the value of a short life extension near the end of life may be experienced as extremely precious by the patient and his or her family. Besides, given the very low number of capacitated patients who want the ECMO therapy to continue for a usually limited time does not constitute the major reasons for resource scarcity in this context. Dilemmas in distributive justice would be more effectively prevented if the problems of organ shortage and adequate ICU resources would be addressed. We do not exclude that in concrete cases of local scarcity, such as in triage cases, it may be ethically appropriate to withhold ECMO and allocate it to another patient who will derive a significantly higher benefit from it. But in general, we consider continuing wanted ECMO in capacitated patients to be a valid strategy respecting the principle of justice as well as the principles of respect for autonomy, beneficence and non-maleficence.

In conclusion, we consider that it would be more beneficial, proportionate, and respectful to withhold care of the unavoidable complications of ECMO than to withdraw ECMO in awake patients requesting continuation of therapy. ECMO as a bridge to death may paradoxically qualify as a palliative care measure, even though it sustains life. The limited time it offers can provide the patient a precious opportunity for life completion, social and spiritual relationships, and preparation for death and bereavement. There are strategies for balancing the principles of respect for autonomy and beneficence with the issue of just resource allocation and using ECMO as a “palliative bridge to death” may thus be ethically well justified.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This open peer commentary is inspired by the work of Prof. Randy Curtis (2/14/1960-2/6/2023), pioneer of the palliative care in the ICU, whose legacy continues to live in our thoughts and actions.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Combes, A., D. Hajage, G. Capellier, A. Demoule, S. Lavoué, C. Guervilly, D. Da Silva, L. Zafrani, P. Tirot, B. Veber, et al. 2018. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine 378 (21):1965–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385.

- Crotti, S., N. Bottino, G. M. Ruggeri, E. Spinelli, D. Tubiolo, A. Lissoni, A. Protti, and L. Gattinoni. 2017. Spontaneous breathing during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in acute respiratory failure. Anesthesiology 126 (4):678–87. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000001546.

- Curtis, J. R., I. J. Higginson, and D. B. White. 2022. Integrating palliative care into the ICU: A lasting and developing legacy. Intensive Care Medicine 48 (7):939–42. doi:10.1007/s00134-022-06729-7.

- Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO). 2023. Accessed February 28. https://www.elso.org/registry/internationalsummaryandreports/internationalsummary.aspx.

- Langer, T., A. Santini, N. Bottino, S. Crotti, A. I. Batchinsky, A. Pesenti, and L. Gattinoni. 2016. Awake" extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): Pathophysiology, technical considerations, and clinical pioneering. Critical Care 20 (1):150. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1329-y.

- Makhoul, M., E. Keizman, U. Carmi, O. Galante, E. Ilgiyaev, M. Matan, A. Słomka, S. Sviri, A. Eden, A. Soroksky, et al. 2023. Outcomes of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for COVID-19 patients: A multi-institutional analysis. Vaccines 11 (1):108. doi:10.3390/vaccines11010108.

- Metaxa, V., D. Anagnostou, S. Vlachos, N. Arulkumaran, S. Bensemmane, I. van Dusseldorp, R. A. Aslakson, J. E. Davidson, R. T. Gerritsen, C. Hartog, et al. 2021. Palliative care interventions in intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Medicine 47 (12):1415–25. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06544-6.

- Murray, S. A., M. Kendall, K. Boyd, and A. Sheikh. 2005. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 330 (7498):1007–11. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007.

- Siddiqui, S., G. Lutz, A. Tabatabai, R. Nathan, M. Anders, M. Gibbons, M. Russo, S. Whitehead, P. Rock, T. Scalea, et al. 2023. Early guided palliative care communication for patients with COVID-19 receiving ECMO. American Journal of Critical Care 13:e1–e11. doi:10.4037/ajcc2023184.

- Schneiderman, L. J. 2011. Defining medical futility and improving medical care. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 8 (2):123–31.