Abstract

Background: Study retention is a major challenge in HIV clinical trials conducted with persons recruited from correctional facilities.

Objective: To examine study retention in a trial of within-prison methadone initiation and a behavioral intervention among incarcerated men with HIV and opioid dependence in Malaysia.

Methods: In this 2x2 factorial trial, 296 incarcerated men with HIV and opioid dependence were allocated to (1) an HIV risk reduction intervention, the Holistic Health Recovery Program for Malaysia (HHRP-M), (2) pre-release methadone initiation, (3) both interventions, or (4) standard care (NCT02396979). Here we estimate effects of these interventions on linkage to the study after prison release and completion of post-release study visits.

Results: Most participants (68.9%) completed at least one post-release study visit but few (18.6%) completed all 12. HHRP-M was associated with a 13.5% (95% confidence interval (CI): 3.8%, 23.2%) increased probability of completing at least one post-release study visit. Although not associated with initial linkage, methadone treatment was associated with an 11% (95% CI: 2.0%, 20.6%) increased probability of completing all twelve post-release study visits. Being subject to forced relocation outside Kuala Lumpur after prison release decreased retention by 43.3% (95% CI: −51.9%, −34.8%).

Conclusion: Retaining study participants in HIV clinical trials following prison release is challenging and potentially related to the broader challenges that participants experience during community reentry. Researchers conducting clinical trials with this population may want to consider methadone and HHRP as means to improve post-release retention, even in clinical trials where these interventions are not being directly evaluated.

1. Introduction

Over 10.7 million people are incarcerated worldwide.Citation1 People who spend time in correctional facilities are disproportionately at risk for numerous communicable and chronic diseases including HIV and opioid use disorder (OUD).Citation2,Citation3 Despite interventions developed to treat HIV and substance use disorders (SUDs) in prisoners,Citation4 treatment effectiveness diminishes quickly after prison release.Citation5 During the transition from prison to the community, people with HIV (PWH) and/or OUD often find it challenging to adhere to prescribed medical treatmentsCitation6,Citation7 or abstain from drugs and alcohol.Citation8,Citation9 Moreover, correctional facilities may intensify health disparities after prison release through persistent institutional effects.Citation10 Evidence from high-income settings suggests that exposure to the prison environment elevates the risk of treatment non-adherenceCitation11 and reduces lifespan in a dose-response fashion.Citation12,Citation13 PWH with frequent and repeated criminal justice system exposure appear especially vulnerable.Citation7

Given the higher prevalence of HIV and OUD in criminal justice populations, correctional facilities are important settings in which to offer interventions to improve treatment of HIV and OUD during community reentry.Citation14,Citation15 Several recent clinical trials have examined the effectiveness of interventions to improve health outcomes in PWH returning to the community, including case management,Citation16 directly-observed antiretroviral therapy (ART),Citation17 methadone,Citation18,Citation19 buprenorphine,Citation20,Citation21 and extended-release naltrexone.Citation22 These studies provide encouraging evidence that starting treatment for OUD in prison may increase treatment uptake and reduce drug-related risk behaviors after prison release.Citation19,Citation23,Citation24

A main challenge for generating high-quality evidence from these studies is the ability to retain research participants after they are released from correctional facilities. Incomplete retention can introduce bias, decrease statistical power, and limit the ability to make causal inferences.Citation25 Studies with persons transitioning from prisons demonstrate lower retention rates (40% to 74%) relative to studies conducted solely within the community (86%).Citation26–Citation28 For example, in two recent studies involving prisoners, one third to one half of the original samples were lost to follow-up within six months after prison release.Citation16,Citation22 Understanding participant characteristics and study-related factors associated with higher retention rates may lead to more effective retention strategies and improve the quality of longitudinal research with persons recruited in correctional facilities.

This study examined predictors of study linkage and retention after prison release in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted with incarcerated persons with HIV and OUD in Malaysia.Citation29 We hypothesized that interventions targeting substance use and HIV transmission risk behaviors might also influence patterns of study retention following prison release. We examined the effects of two experimental interventions (pharmacological and behavioral) delivered within prison on linkage and retention in the study during the year after prison release.

2. Methods

2.1.Study design

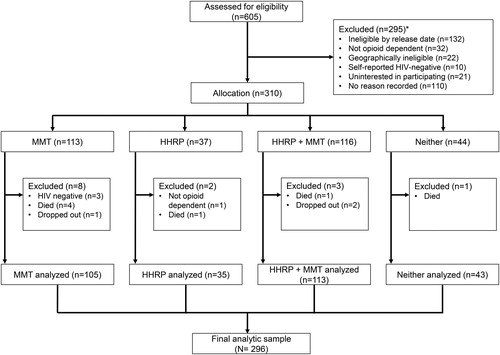

The study design has been described previously.Citation29 Briefly, HIV-positive and opioid-dependent incarcerated men enrolled in a RCT that utilized a 2 x 2 factorial design to evaluate the effects of two interventions on HIV transmission risk behaviors following prison release: (1) methadone treatment initiated prior to prison release with linkage to subsidized methadone in the community and (2) the Holistic Health Recovery Program (HHRP), a behavioral intervention that was adapted for the Malaysian prison setting (HHRP-M).Citation30 All subjects were randomized 1:1 to HHRP-M or no HHRP-M. Subjects were initially also randomized to methadone, however, due to changing standards of care and strong individual preferences, protocols were adjusted during the early stages of recruitment to allow subjects to be allocated to methadone or no methadone based on their individual preferences. Eligible participants were Malaysian citizens ≥18 years of age, HIV-infected and opioid dependent, within six months of prison release, and planning to return to Greater Kuala Lumpur after prison release. presents a study flow diagram. This analysis utilizes data from 296 participants who were successfully allocated to one of the study’s four groups and survived until prison release. Analyzed participants included n = 105 allocated to methadone only, n = 35 allocated to HHRP-M only, n = 113 allocated to both HHRP-M and methadone, and n = 43 allocated to standard care (). Summing across the two interventions, this represents n = 218 allocated to methadone and n = 78 not allocated to methadone, and n = 148 allocated to HHRP-M, and n = 148 allocated to no HHRP-M.

2.2. Study setting

Malaysia is an ethnically and culturally diverse upper-middle-income country where HIV, addiction, and incarceration are syndemic.Citation31 Although the number of new HIV infections has decreased,Citation32 HIV prevalence remains high in key populations including people who inject drugs (PWID).Citation33 Criminalization of drug use has concentrated PWID into prisons where HIV testing is compulsory and PWH are segregated. Despite high HIV prevalence, healthcare resources within these facilities are often inadequate to address the complex health needs of patients.Citation34 This study was set in Greater Kuala Lumpur. Subjects were recruited from Malaysia’s largest prison facility, which is located within the Klang Valley, houses approximately 4000 prisoners, and has an HIV prevalence of 5%.Citation29

2.3. Standard care

At the time of the study, all HIV-diagnosed patients were under the care of a physician, screened for tuberculosis, and were ART eligible according to Ministry of Health guidelines (CD4 < 350 cells/µL); although, ART initiation guidelines evolved over time.Citation29 Faith-based counseling was offered to prisoners seeking help for addiction. Initially, access to methadone for those not enrolled in the study was extremely limited, although the prison gradually expanded its methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) program during the study. Before release, all participants were referred for HIV care and temporary housing assistance, and efforts were made to link all participants to HIV care after release.

2.4. Experimental conditions

2.4.1. Pharmacological treatment with methadone

Protocols for within-prison MMT initiation were based on a pilot study showing that a methadone dose ≥80 mg/day at the time of release was associated with higher retention in substance use treatment.Citation35 All participants screened negative for opiates on urine drug testing at enrollment and were started on a 5 mg daily initial methadone dose that was increased by 5 mg weekly to reach a target daily dose of 80 mg. Subjects allocated to methadone were linked to fully subsidized treatment in the community. Methadone dosing was directly observed in prison and throughout the first month after release. Protocols for methadone dosing and titration were actively monitored by a study clinician within prison and throughout the 12-month post-release follow-up period.

2.4.2. The Holistic Health Recovery Program, Malaysia

The HHRP-M is an evidence-based HIV risk reduction interventionCitation36 that was adapted for the Malaysian prison setting.Citation30 HHRP-M consisted of eight two-hour group sessions conducted within prison with an optional individual “booster session” scheduled one month after release. Topics included accessing health care, reducing HIV transmission risk behaviors, preventing drug relapse, overcoming stigma, moving beyond grief, and achieving personal goals.Citation30

2.5. Study procedures

Participants who gave informed consent completed questionnaires, confirmatory HIV testing, CD4+ T-cell and viral load quantification, and were allocated using block randomization to one of four treatment groups: (1) methadone, (2) HHRP-M, (3) methadone + HHRP-M, or (4) standard care, with deviation from random assignment to methadone as described above. Participants were reenrolled into the study on their release date or the date of their first post-release study visit. Participants were followed for one year after prison release and completed monthly visits in the community. On their release date, participants met with a research assistant who updated their contact information and provided transportation to study-affiliated clinics if needed. Between post-release study visits, researchers maintained contact with participants by phone and SMS text messages or by locating participants at their residential address or “hangouts” in the community where they agreed to be contacted by researchers. Missing one or more post-release study visits did not preclude participation in future visits. For their time, participants received RM130 ($31 USD) on their release date, RM50 ($12 USD) at quarterly follow-up visits, and RM40 ($10 USD) at monthly follow-up visits.

2.6. Study measures

2.6.1. Dependent variable

To estimate the effects of study interventions on retention, we chose three operational definitions. “Linkage” was defined as having completed at least one follow-up study visit in the community after prison release, irrespective of time since release. “Retention” was measured as a continuous variable, using each of the 12 monthly follow-up visits as repeated measures. "Sustained retention" was measured as a dichtomous variable, defined as having completed all 12 monthly follow-up visits.

2.6.2. Independent variables

Baseline variables used in analysis were selected a priori based on previous research and substantive expertise. Demographic variables included a participant’s age, highest level of education, and whether the participant anticipated a permanent living arrangement after release (i.e. stable housing). Incarceration variables included sentence length and relocation status, which assessed whether the participant was subject to legally enforced deportation from Kuala Lumpur to another Malaysian state after prison release under the Prevention of Crimes Act (PCA). HIV treatment variables included years since HIV diagnosis, baseline CD4+ T-cell count and previous ART use.

Social support was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support survey,Citation37 which included 19 Likert-type items assessing participants emotional/informational support, tangible support, affectionate support, and positive social interaction. Composite scores were calculated by averaging item responses and transformed linearly (0–100), with higher scores representing higher levels of perceived social support.

HIV stigma was measured using Berger's HIV Stigma Scale,Citation38 a 40-item scale that measures personalized stigma, disclosure concerns, negative self-image, and perceived public attitudes towards PWH using a four-point Likert-type scale. One item with low reliability, “people don’t want me around their children once they know I have HIV,” was dropped. Total scores were calculated by averaging responses to the remaining 39-items (39–59), with higher scores indicating higher perceived stigma.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using the five-item general health scale on the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) survey.Citation39 The general health composite score was generated from sub-scale average scores.

Depression was measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D),Citation40 which uses 20 items to assess the frequency of depression symptoms in the previous two weeks from (1) “rarely or not at all” to (4) “most or all of the time.” Composite scores are calculated as the sum of responses to all 20 items, with scores ≥ 16 indicating clinically significant depressive symptomology.

Substance use variables included substance use and drug injection during the participant’s lifetime and 30 days before incarceration. Pre-incarceration alcohol use was assessed using the 10-item World Health Organization Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT).Citation41 Scores ranging from 8–40 indicate the presence of an alcohol use disorder.

Pre-incarceration addiction severity was measured using the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) drug subscale,Citation42 which measures social and health consequences of substance use. Composite scores ranged from 0–0.52, with higher scores indicating greater addiction severity.

To improve validity, all survey measures underwent rigorous forward-backward translation by bilingualsCitation43 and were piloted with the first 10 participants to ensure understanding. Mean scores were imputed for measures with missing data.

2.7. Statistical analyses

To estimate the effects of methadone and HHRP-M on retention, we used multiple estimation strategies. For the fully randomized HHRP-M, we present results from unadjusted non- or semi-parametric estimators; for methadone, we present adjusted estimates that attempt to correct for potential selection bias from non-random allocation. Excluded from our analyses were 14 subjects who withdrew from the study (n = 3), were determined to be ineligible (n = 4), or who died (n = 7) after allocation and before prison release.

2.7.1. Estimating intervention effects on study linkage and sustained retention after prison release

For both dichotomous measures of retention—linkage and sustained retention—we first present unadjusted point estimates for HHRP-M and methadone accompanied by a non-parametric estimator of the varianceCitation44 for HHRP-M and a T-statistic-based estimator of the variance for methadone. The unadjusted simple difference-in-means estimator is unbiased for the fully-randomized HHRP-M and subject to selection bias for methadone because most participants were allocated to methadone based on their personal preference. To increase precision and decrease bias, we also present three model-assisted treatment effect estimators that adjust for all the baseline characteristics shown in . These estimators include outcome regression (OLS) regression, inverse propensity score weighting (IPW) with weights estimated using logistic regression and stabilized by the marginal probability of receiving methadone,Citation45,Citation46 and a doubly-robust estimator that incorporates both of these two approaches.Citation47,Citation48 The non-parametric bootstrap was used to estimate uncertainty for the model-assisted estimators.Citation49

Table 1 Participant characteristics at enrollment by treatment group (N = 296)

2.7.2. Estimating intervention effects on retention

To estimate intervention effects on retention across all 12 study visits, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an exchangeable covariance structure and the robust sandwich estimator of the variance.Citation50 We present unadjusted GEE models for HHRP-M and methadone as well as a model adjusting for all the baseline covariates shown in . Additional models examining the effects of time and interactions between the interventions are presented in the Supplementary Appendix. GEE models were fit using the R package geepack.Citation51

2.8. Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by institutional review boards at University of Malaya and Yale University, with additional oversight by the Office of Human Research Protection at the US Department of Health and Human Services. All participants provided informed consent prior to enrollment and again at their first post-release study visit. The trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02396979).

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

shows baseline characteristics of the 296 study participants by treatment group. Participants randomized to HHRP-M and no HHRP-M did not differ on the baseline characteristics shown in , except for pre-incarceration heroin use (p = 0.03). Participants allocated to methadone or no methadone differed only on drug addiction severity score (p = 0.002).

3.2. Effects of interventions on linkage

Overall, two thirds of participants (68.9%) completed at least one post-release study visit. We estimate that HHRP-M increased the probability of completing at least one post-release study visit by 13.5% (95% confidence interval (CI): 3.8%, 23.2%), based on the unadjusted estimate and a non-parametric estimator of the variance. For HHRP-M, model-assisted estimators adjusting for baseline covariates yielded similar estimates (). The unadjusted estimate of the effect of pre-release methadone on completion of at least one post-release study visit was 10.0% (95% CI: −2.5%, 22.6%). Model-assisted estimators adjusting for baseline covariates produced similar estimates with confidence intervals that were also compatible with a null effect ().

Table 2 Estimated effects of HHRP-M and pre-release methadone initiation on reenrollment (completion of ≥ 1 post-release study visit) within 12 months of prison release

3.3. Effects of interventions on retention

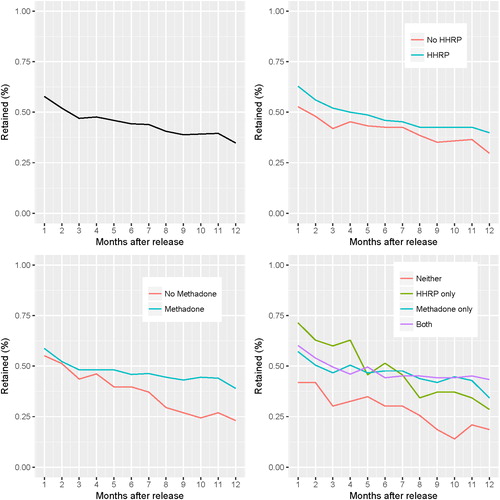

Participation declined sharply in the first month after prison release (57.8%) and continued to decline until the final study visit (34.8%). Across all 12 study visits, we estimate that HHRP-M increased retention by 6.6% (95% CI: −2.6%, 15.8%) using an unadjusted GEE model, though this confidence interval is compatible with a null effect (, Model 1). The adjusted model yielded a similar estimate of HHRP-M’s effect, also with a confidence interval compatible with a null effect (, Model 3). Across all study visits, we estimate that methadone significantly increased retention by 10.8% (95% CI: 0.8%, 20.8%) using the GEE model adjusting for baseline covariates (, Model 3).

Table 3 Estimated effects of HHRP-M and pre-release methadone initiation on post-release retention across all time points using generalized estimating equations

3.4. Effects of interventions on sustained retention

We also estimated the effects of HHRP-M and methadone on the probability of sustained retention, defined as attending all 12 monthly post-release study visits (). The estimated effect of HHRP-M on the probability of sustained retention was 3.4% (95% CI: −5.3%, 12.0%) in unadjusted analysis, with the confidence intervals from unadjusted and adjusted analyses broadly overlapping with zero. Methadone was associated with an increased probability of sustained retention in analyses adjusting for baseline characteristics, with the confidence intervals overlapping with zero for the OLS estimator (9.5%, 95% CI: −0.5%, 19.5%) and not overlapping with zero for the inverse propensity score weighting (11.3%, 95% CI: 2.6%, 19.5%) and doubly robust (11.0%, 95% CI: 2.0%, 20.6%) estimators.

Table 4 Estimated effects of HHRP-M and pre-release methadone initiation on sustained retention, defined as completion of all 12 monthly follow-up visits a

3.5. Temporal trends, interaction effects, and correlates of retention

We plotted retention and fit several additional GEE models to examine temporal trends, interaction effects, and correlates of retention. Participation declined over time, as shown in and demonstrated by the significant effect of time in all GEE models in which it was included (Supplementary Appendix Table S1). Trends in intervention effects over time differed for HHRP-M and methadone. The interaction between HHRP and time was not associated with retention in a basic interaction model (95% CI: −1.2%, 0.9%; Supplemental Appendix Table S1). Similarly, the difference in retention between HHRP-M and no HHRP-M participants was small and remained relatively constant over time (, Panel B). The interaction between methadone and time, however, was positively associated with retention (95% CI: 0.5%, 2.9%; Supplemental Appendix Table S1). As shown in Panel C of , participants allocated to methadone were lost to follow-up at a slower rate compared to participants not allocated to methadone.

To examine the interaction between the two interventions, we fit a model including HHRP-M, methadone, their interaction, and the set of baseline covariates (Supplemental Appendix Table S2). The coefficient for the interaction of HHRP-M and methadone (−12.5%, 95% CI: −31.5%, 6.4%) had a similar magnitude to and opposite sign of the coefficients for both HHRP-M (14.5%, 95% CI: -1.6%, 30.7%) and methadone (16.5%, 95% CI: 3.3%, 29.7%), suggesting that any increased retention due to either HHRP-M or methadone might not have been further increased by receiving both interventions. This trend can also be seen in Panel D of showing that retention rates among those receiving HHRP-M, methadone, or both interventions were similar and potentially greater than retention rates among those who received neither intervention.

Among baseline measures evaluated, PCA relocation status – police enforced relocation after prison release - was the strongest predictor of retention, associated with a 43.3% decreased (95% CI: −51.9%, −34.8%) probability of retention over all study visits (, Model 3).

4. Discussion

Successful post-release follow-up of participants recruited in correctional facilities is essential for developing effective interventions to improve health outcomes in people with HIV (PWH) and OUD. In this study, we examined the effects of within-prison methadone initiation and a behavioral HIV risk reduction intervention on study retention in men with HIV and OUD recently released from prison in Malaysia. Participation declined rapidly after prison release and continued to decline over time, with only 18.6% completing all 12 post-release study visits. Concerning was the amount of missing post-release data (>50%), which reduces power and makes unbiased estimation of treatment effects challenging.Citation28 Although consistent with retention rates in similar studies,Citation16,Citation19,Citation22,Citation24,Citation26,Citation28,Citation52,Citation53 findings here demonstrate the challenges of retaining study participants recruited from correctional facilities in long-term follow-up and the need for more effective retention strategies in this population.

Two possible explanations for the rapid loss to follow-up in this group of prisoners with OUD and HIV are relapse to opioids and HIV-related mortality. Relapse to opioids may occur in up to 90% of released prisoners within one year, with much of the relapse occurring in the first 1 − 2 weeks after releaseCitation54,Citation55 and contributes greatly to the high mortality rates (8.5 deaths per 1000 person-years) observed in released prisoners globally.Citation56 Another potential explanation for the high rates of attrition observed is mortality attributable to HIV-related opportunistic infections, which may surpass drug overdose as a leading cause of death in released prisoners in low-to-middle income countries where HIV treatment post-release is not adequately supported.Citation57,Citation58 In this study, subjects who were ART-experienced when they enrolled into the study were no more or less likely to be retained after prison release. Unknown, however, is whether subjects who initiated or were adherent to ART after their enrollment date were more likely to be retained.

Findings here suggest that in addition to reducing drug relapse and mortality, interventions to address infectious disease and substance use during reentry may also improve retention rates.Citation59 While receiving HHRP-M was associated with linkage to the study (completion of at least one study visit and linked to payment), only methadone was associated with study retention, both when defined as a repeated measure or as sustained retention to all visits. One explanation for the effect of HHRP-M on linkage is that HHRP-M participants were offered an optional individual “booster” session four weeks after prison release for which they received additional compensation. Moreover, subjects allocated to the HHRP-M intervention received more structured interaction with research staff in the form of eight intervention sessions. As a result, HHRP-M participants may have been more engaged and may have developed a greater interest in participating in the study due to stronger relationships with research staff.Citation60 Such characteristics of the HHRP-M intervention have been shown to improve retention in previous studies.Citation27,Citation59,Citation61

One explanation for the increased retention in the methadone arm is that methadone, which has been repeatedly demonstrated to improve HIV-related health outcomes,Citation62 including among prisoners,Citation64Citation24 and in supervised settings in Malaysia,Citation63 may have improved study retention by preventing drug relapse and improving social functioning.Citation64 Additionally, increased retention in the methadone arm could have been due to the proximity of interview sites to methadone treatment facilities or to increased ability of research staff to locate participants engaged in methadone therapy, both of which could bias treatment effect estimates.Citation65 Regardless of the mechanism, interventions that address infectious disease and substance use in this population are not only the evolving standard of care, but also may be an important aspect of study design that improves retention rates even in studies that are not specifically designed to test the effects of these interventions.

In addition to elevated health risks, persons recruited from correctional facilities may encounter numerous practical barriers to study participation before and after prison release. First, research staff may have difficulty maintaining contact with incarcerated subjects. Cell phones, for example, which could be used to send contact reminders and update contact information, are contraband. Second, prisoners may not know their post-release contact details such as their residential address, phone number, or emergency contact until the day of release or afterwards when they are re-established in the community. Third, incarcerated subjects may have their release date changed or be transferred to another correctional facility and have difficulty communicating these changes to research staff. Fourth, participants recruited in correctional facilities may remain incarcerated for many months/years after enrollment and may misplace study contact information or forget that they are involved with a study. Even when study contact information is included with a person's discharge paperwork, it may become lost or misplaced. Finally, participants released from correctional facilities may be justifiably more concerned with meeting their immediate physiological and safety needs than with contacting researchers. For these reasons, we recommend that researchers actively engage participants throughout the study and collaborate with prison administrators to remain aware of release plans.Citation27,Citation61

Finally, although all participants planned to return to Kuala Lumpur after prison release, some were subject to an antiquated provision under Malaysia’s Prevention of Crime Act (PCA) of 1959, which significantly reduced study retention. Under the PCA of 1959, persons may be forcefully relocated to other cities after prison release at the discretion of law enforcement.Citation66 Although this law was repealed in 2011, some study participants (9% of this sample) were evidently subject to forced relocation and possibly prevented from returning to Kuala Lumpur to be able to continue their participation in the study. Deleterious law enforcement practices not only impede study retention but also destabilize individuals, hampering their ability to reintegrate into the community and denying them the very resources they may need to be healthy.

Although this study provides important insights into longitudinal research with released prisoners with HIV, there are nevertheless some important limitations. First, we did not estimate the effects of post-release HIV treatment and substance use outcomes on study retention due to incomplete post-release data. Beyond the scope of the present study and requiring further investigation were other possible reasons for post-release attrition, including disability, hospitalization, death, loss of interest in the study, concerns about stigmatization from study participation, or moving outside the study catchment area. Additionally, we did not account for other study-related factors such as the completeness and quality of participant locator information or frequency of contact with research staff as variables that may influence retention.Citation26 Last, we did not control for methadone dose, which has previously been associated with higher levels of retention.Citation35 These limitations notwithstanding, this study is one of the first to examine study attrition following prison release in a low- to middle-income country and, as such, contributes to research with persons recruited in correctional facilities who represent an especially important population for HIV and SUD clinical trials.

5. Conclusion

Retaining study participants in HIV clinical trials after prison release is challenging and potentially related to the broader health and social challenges that participants experience during community reentry. By improving health outcomes and social functioning, interventions targeting HIV and substance use during reentry may also increase retention rates. Even in studies that do not directly evaluate HIV and substance use outcomes, researchers may need to consider whether study protocols adequately address the overall burden of infectious disease and SUD as factors potentially contributing to study attrition after prison release. Improved coordination with prison administrators also is needed to address restrictions on communication and mobility within prison and after release that may adversely influence study retention and social reintegration during reentry.

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank study participants for generously sharing of their time. We also thank study coordinators, research assistants, and data managers at CERiA and Yale University who helped to retain study participants and assemble the data set. Finally, we wish to thank the Malaysian Prison Department [Jabatan Penjara Malaysia] for their cooperation and assistance to conduct the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest associated with the study itself was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Divya K. Chandra

Divya Chandra, MPH, graduated from the Yale School of Public Health with a degree in epidemiology. She uses epidemiological methods to investigate infectious diseases in vulnerable populations, including persons with substance use disorders, pediatric populations, and pregnant women. Her current work focuses on HIV and tuberculosis in underserved communities.

Alexander R. Bazazi

Alexander R. Bazazi, MD, PhD, is a resident physician at the University of California San Francisco Department of Psychiatry. As an epidemiologist, he uses quantitative methods to study the health of people who use drugs, identify points for intervention, and evaluate new approaches to harm reduction and the treatment of substance use disorder. His work focuses on the intersection of drug use, HIV and the criminal justice system.

Muzammil A. Nahaboo Solim

Muzammil A. Nahaboo Solim, BSc (Hons), MBBS, MPH, is currently working as a physician in the UK. His research interests includes translational medicine and public health.

Adeeba Kamarulzaman

Adeeba Kamarulzaman, MBBS, FRACP, FASc is Dean of the Faculty of Medicine and Professor of Medicine and Infectious Diseases at the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and Associate Professor (Adjunct) of Medicine at Yale School of Medicine. Dr. Kamarulzaman has dedicated her career to the prevention, treatment and research of infectious diseases and HIV/AIDS. In 2007, Dr. Kamarulzaman established the Centre of Excellence for Research in AIDS (CERiA) at the University of Malaya, one of the few dedicated HIV research centres in the region.

Frederick L. Altice

Frederick L. Altice, MD, is Professor of Medicine (Infectious Diseases) at Yale School of Medicine and of Epidemiology (Microbial Diseases) at Yale School of Public Health. He is Academic Icon Professor of Medicine at the University of Malaya, Cente of Excellence for Research in AIDS (CERiA). Dr. Altice's primary research project focuses on the interface between infectious diseases and substance use disorders and he has a special interest in Global Health. He also has a number of projects working in the criminal justice system, including transitional programs addressing infectious diseases, medication-assisted therapies, mental illness and social instability.

Gabriel J. Culbert

Gabriel J. Culbert, PhD, RN, is Assistant Professor of Health Systems Science at the University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Nursing. Dr. Culbert's research focuses on developing interventions to improve uptake and long-term adherence to antiretroviral therapy among persons with HIV and opioid dependence transitioning from prisons in low-to-middle-income countries.

References

- Walmsley R. World Prison Population List. 12th ed. London: Institute for Criminal Policy research; 2018.

- Dolan K, Wirtz AL, Moazen B, et al. Global burden of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in prisoners and detainees. Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1089–1102.

- Herbert K, Plugge E, Foster C, Doll H. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet. 2012;379(9830):1975–1982.

- Kouyoumdjian FG, McIsaac KE, Liauw J, et al. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of interventions to improve the health of persons during imprisonment and in the year after release. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):e13–e33.

- Iroh PA, Mayo H, Nijhawan AE. The HIV care cascade before, during, and after incarceration: a systematic review and data synthesis. Am J Public Health. 2015;301(8):e1–e12.

- Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, et al. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA. 2009;301(8):848–857.

- Loeliger KB, Altice FL, Desai MM, Ciarleglio MM, Gallagher C, Meyer JP. Predictors of linkage to HIV care and viral suppression after release from jails and prisons: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2018;5(2):e96–e106.

- Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, et al. Return to drug use and overdose after release from prison: a qualitative study of risk and protective factors. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7(1):3.

- Winter RJ, Young JT, Stoové M, Agius PA, Hellard ME, Kinner SA. Resumption of injecting drug use following release from prison in Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;168:104–111.

- Wildeman C, Wang EA. Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1464–1474.

- Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Buxton J, et al. Dose-response effect of incarceration events on nonadherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(9):1215–1221.

- Patterson EJ. The dose-response of time served in prison on mortality: New York State, 1989-2003. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):523–528.

- Loeliger KB, Altice FL, Ciarleglio MM, et al. All-cause mortality among people with HIV released from prison in Connecticut, 2007-2014. Lancet HIV. 2018;5(11):e617–e628.

- Springer SA, Spaulding AC, Meyer JP, Altice FL. Public health implications for adequate transitional care for HIV-infected prisoners: five essential components. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(5):469–479.

- Meyer JP, Althoff AL, Altice FL. Optimizing care for HIV-infected people who use drugs: evidence-based approaches to overcoming healthcare disparities. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(9):1309–1317.

- Wohl DA, Golin CE, Knight K, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an intervention to maintain suppression of HIV viremia after prison release: the impact trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(1):81–90.

- Saber-Tehrani AS, Springer SA, Qiu J, Herme M, Wickersham J, Altice FL. Rationale, study design and sample characteristics of a randomized controlled trial of directly administered antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected prisoners transitioning to the community - a potential conduit to improved HIV treatment outcomes. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(2):436–444.

- Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Schwartz RP, O’Grady KE. A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: findings at 6 months post-release. Addiction. 2008;103(8):1333–1342.

- Rich JD, McKenzie M, Larney S, et al. Methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal on incarceration in a combined US prison and jail: a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350–359.

- Springer SA, Qiu J, Saber-Tehrani AS, Altice FL. Retention on buprenorphine is associated with high levels of maximal viral suppression among HIV-infected opioid dependent released prisoners. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e38335.

- Springer SA, Chen S, Altice FL. Improved HIV and substance abuse treatment outcomes for released HIV-infected prisoners: the impact of buprenorphine treatment. J Urban Health. 2010;87(4):592–602.

- Springer SA, Di Paola A, Azar M, Altice FL .Extended-release naltrexone improves viral suppression among incarcerated persons living with HIV with opioid use disorders transitioning to the community: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;78(1):43–53.

- Larney S. Does opioid substitution treatment in prisons reduce injecting-related HIV risk behaviours? A systematic review. Addiction. 2010;105(2):216–223.

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O'Grady KE. A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: results at 12 months postrelease. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37(3):277–285.

- Zweben A, Fucito LM, O'Malley SS. Effective strategies for maintaining research participation in clinical trials. Drug Inf J. 2009;43(4):459–467.

- Goshin LS, Byrne MW. Predictors of post-release research retention and subsequent reenrollment for women recruited while incarcerated. Res Nurs Health. 2012;35(1):94–104.

- Robinson KA, Dennison CR, Wayman DM, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Systematic review identifies number of strategies important for retaining study participants. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(8):757–765.

- Western B, Braga A, Hureau D, Sirois C. Study retention as bias reduction in a hard-to-reach population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113(20):5477–5485.

- Bazazi AR, Wickersham JA, Wegman MP, et al. Design and implementation of a factorial randomized controlled trial of methadone maintenance therapy and an evidence-based behavioral intervention for incarcerated people living with HIV and opioid dependence in Malaysia. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;59:1–12.

- Copenhaver MM, Tunku N, Ezeabogu I, et al. Adapting an evidence-based intervention targeting HIV-infected prisoners in Malaysia. AIDS research and treatment. 2011;2011:131045.

- Culbert GJ, Pillai V, Bick J, et al. Confronting the HIV, tuberculosis, addiction, and incarceration syndemic in Southeast Asia: lessons learned from Malaysia. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2016;11(3):446–455.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Ending AIDS: Progress towards the 90-90-90 targets. Geneva: UNAIDS;2017.

- Bazazi AR, Crawford F, Zelenev A, Heimer R, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs in greater Kuala Lumpur recruited using respondent-driven sampling. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(12):2347–2357.

- Bick J, Culbert G, Al-Darraji HA, et al. Healthcare resources are inadequate to address the burden of illness among HIV-infected male prisoners in Malaysia. Int J Prison Health. 2016;12(4):253–269.

- Wickersham JA, Zahari MM, Azar MM, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Methadone dose at the time of release from prison significantly influences retention in treatment: implications from a pilot study of HIV-infected prisoners transitioning to the community in Malaysia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(1-2):378–382.

- Margolin A, Avants SK, Warburton LA, Hawkins KA, Shi J. A randomized clinical trial of a manual-guided risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive injection drug users. Health Psychol.2003;22(2):223–228.

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714.

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–529.

- Ware J, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483.

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas.1977;1(3):385–401.

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804.

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. J Subst Abus.1992;9(3):199–213.

- Degroot AM, Dannenburg L, Vanhell JG. Forward and backward word translation by bilinguals. J Mem Lang.. 1994;33(5):600–629.

- Aronow PM, Green DP, Lee DKK. Sharp bounds on the variance in randomized experiments. Ann Stat. 2014;42(3):850–871.

- Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):550–560.

- Cole SR, Hernan MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(6):656–664.

- Kang JDY, Schafer JL. Demystifying double robustness: a comparison of alternative strategies for estimating a population mean from incomplete data. Stat Sci. 2007;22(4):523–539.

- Bang H, Robins JM. Doubly robust estimation in missing data and causal inference models. Biometrics. 2005;61(4):962–973.

- Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Vol. 57. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1993.

- Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data - a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(4):1049–1060.

- Halekoh U, Hojsgaard S, Yan J. The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. J Stat Softw. 2006;15(2):1–11.

- Menendez E, White MC, Tulsky JP. Locating study subjects: predictors and successful search strategies with inmates released from a US county jail. Control Clin Trials. 2001;22(3):238–247.

- White MC, Tulsky JP, Goldenson J, Portillo CJ, Kawamura M, Menendez E. Randomized controlled trial of interventions to improve follow-up for latent tuberculosis infection after release from jail. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(9):1044–1050.

- Merrall EL, Kariminia A, Binswanger IA, et al. Meta-analysis of drug-related deaths soon after release from prison. Addiction. 2010;105(9):1545–1554.

- Ranapurwala SI, Shanahan ME, Alexandridis AA, et al. Opioid overdose mortality among former North Carolina inmates: 2000–2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(9):1207–1213.

- Zlodre J, Fazel S. All-cause and external mortality in released prisoners: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):e67–e75.

- Culbert GJ, Crawford FW, Murni A, et al. Predictors of mortality within prison and after release among persons living with HIV in Indonesia. Res Rep Trop Med. 2017;8:25–35.

- Huber F, Merceron A, Madec Y, et al. High mortality among male HIV-infected patients after prison release: ART is not enough after incarceration with HIV. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175740.

- Quinn C, Byng R, Shenton D, et al. The feasibility of following up prisoners, with mental health problems, after release: a pilot trial employing an innovative system, for engagement and retention in research, with a harder-to-engage population. Trials. 2018;19(1):530.

- Iguchi MY, London JA, Forge NG, Hickman L, Fain T, Riehman K. Elements of well-being affected by criminalizing the drug user. Public Health Rep.2002;117 (Suppl 1):S146–S150.

- Robinson KA, Dinglas VD, Sukrithan V, et al. Updated systematic review identifies substantial number of retention strategies: using more strategies retains more study participants. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2015;68(12):1481–1487.

- Low AJ, Mburu G, Welton NJ, et al. Impact of opioid substitution therapy on antiretroviral therapy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(11):1094–1104.

- Wegman MP, Altice FL, Kaur S, et al. Relapse to opioid use in opioid-dependent individuals released from compulsory drug detention centres compared with those from voluntary methadone treatment centres in Malaysia: a two-arm, prospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(2):e198–e207.

- Dolan K, Salimi S, Nassirimanesh B, Mohsenifar S, Allsop D, Mokri A. Six-month follow-up of Iranian women in methadone treatment: drug use, social functioning, crime, and HIV and HCV seroincidence. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2012;3(Suppl 1):37–43.

- Bell ML, Kenward MG, Fairclough DL, Horton NJ. Differential dropout and bias in randomised controlled trials: when it matters and when it may not. BMJ. 2013;346:e8668.

- Restricted residence act of 1933 (Revised 1989). Malaysia Legislation. http://www.commonlii.org/my/legis/consol_act/rra19331989280/