Abstract

Background: People living with HIV (PLWH) frequently experience chronic pain and receive long-term opioid therapy (LTOT). Adherence to opioid prescribing guidelines among their providers is suboptimal.

Objective: This paper describes the protocol of a cluster randomized trial, targeting effective analgesia in clinics for HIV (TEACH), which tested a collaborative care intervention to increase guideline-concordant care for LTOT among PLWH.

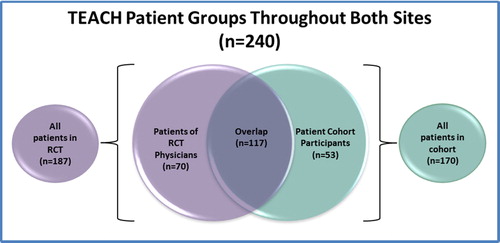

Methods: HIV physicians and advanced practice providers (n = 41) were recruited from September 2015 to December 2016 from two HIV clinics in Boston and Atlanta. Patients receiving LTOT from participating providers were enrolled through a waiver of informed consent (n = 187). After baseline assessment, providers were randomized to the control group or the year-long TEACH intervention involving: (1) a nurse care manager and electronic registry to assist with patient management; (2) opioid education and academic detailing; and (3) facilitated access to addiction specialists. Randomization was stratified by site and LTOT patient volume. Primary outcomes (≥2 urine drug tests, early refills, provider satisfaction) were collected at 12 months. In parallel, PLWH receiving LTOT (n = 170) were recruited into a longitudinal cohort at both clinics and underwent baseline and 12-month assessments. Secondary outcomes were obtained through patient self-report among participants enrolled in both the cohort and the RCT (n = 117).

Conclusions: TEACH will report the effects of an intervention on opioid prescribing for chronic pain on both provider and patient-level outcomes. The results may inform delivery of care for PLWH on LTOT for chronic pain at a time when opioid practices are being questioned in the US.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02564341.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02525731.

Introduction

As overdose deaths in the United States have continued to rise, national attention on the opioid epidemic has led to intense scrutiny of the use of prescription opioids for chronic pain.Citation1–5 Prescription opioids have been identified as one of the chief contributors to the epidemic,Citation6 and thus, the risk-benefit ratio must be carefully considered when treating chronic pain with long-term opioid therapy (LTOT).Citation7,Citation8

People living with HIV (PLWH) sit at this junction, representing a high-need group in terms of their painful comorbid conditions, and a high-risk group in terms of potential adverse outcomes related to opioids due to intersecting risk factors such as substance use.Citation9 PLWH have higher rates of chronic pain than the general population, with estimates ranging from 39% to 85%,Citation10–25 and prescription opioid rates as high as 65%.Citation26–29 Further, these patients receive opioids at higher doses than individuals without HIV, and are more likely to be co-prescribed benzodiazepines or other sedating medications.Citation27–32 Concomitant with the rise of prescription opioid misuse in the general population, the nonmedical use of these medications is increasingly common among PLWH.Citation33–37 Our group recently found that among PLWH on LTOT, 43% had a high current opioid misuse measure (COMM) score, suggestive of potential opioid misuse.Citation38,Citation39 This is presumably related to the known co-morbidity between HIV and opioid use disorder.Citation40,Citation41 At the same time, pain is frequently associated with substance use,Citation42–46 with some studies even suggesting that individuals self-medicate.Citation47,Citation48 Chronic pain not treated with LTOT among PLWH has been associated with increased odds of suboptimal retention in care.Citation49 In contrast, LTOT has been associated with higher rates of virologic suppression, pointing to the potential HIV-related benefits that can occur in the context of prescribing opioids for pain.Citation49

Given the frequent coexistence of chronic pain and substance use risk in PLWH,Citation50,Citation51 appropriate management of pain with LTOT is complicated.

HIV providers are faced with the complex and often daunting task of prescribing opioids for pain. National guidelines for prescribing LTOT exist, including those specifically for PLWH, and these guidelines can help providers make informed decisions to mitigate risks.Citation7,Citation52 However, adopting LTOT guidelines is challenging for HIV providers.Citation53 They report low levels of satisfaction for pain management aspects of clinical care, as well as low confidence in their abilities to treat chronic pain.Citation54,Citation55 Few physicians follow standard protocol regarding assessment and may lack resources to closely monitor patients,Citation55–60 resulting in wide variation in opioid prescribing patterns, similar to primary care.Citation61

Although an urgent need exists for interventions that can improve HIV providers’ quality of care regarding opioid pain prescribing, limited studies of such interventions have been conducted to date. None, to our knowledge, focus on opioid prescribing for PLWH.Citation62–67 In order to address this need, we built upon the transforming opioid prescribing in primary care (TOPCARE) intervention for use in PLWH.Citation68,Citation69 Liebschutz et al.Citation68,Citation69 found that TOPCARE improved adherence to guideline-recommended monitoring among primary care patients at a safety net hospital and affiliated community health centers. However, patient-reported outcomes were not assessed. Using TOPCARE as a model, we developed the “Targeting Effective Analgesia in Clinics for HIV” (TEACH) intervention, geared toward HIV providers, and established an observational cohort of PLWH receiving LTOT to assess provider and patient outcomes related to LTOT. This paper describes the study design and implementation.

Methods

Study objective and design

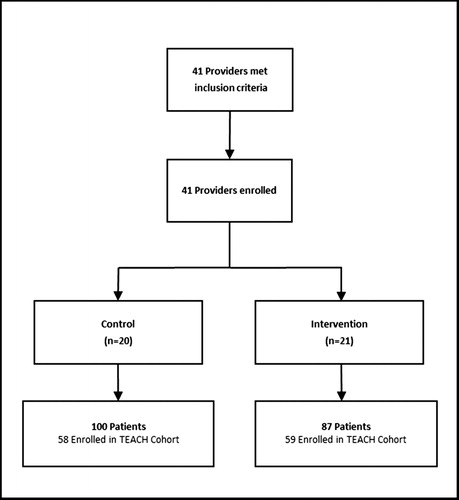

We conducted a cluster-randomized clinical trial of the TEACH collaborative care intervention at two clinics (Boston Medical Center [BMC], Boston, MA and Emory University/Grady Hospital, Atlanta, GA). In parallel, PLWH receiving LTOT (n = 170) were recruited into a longitudinal cohort at both clinics and assessed at baseline and 12 months in order to collect outcomes not available in medical records. Together, the RCT and cohort enabled assessment of the following aims: Aim 1: assess HIV providers’ adherence to LTOT guidelinesCitation8,Citation70, as measured by occurrence of ≥2 urine drug tests (UDTs) at 12 months (primary); Aim 2: assess patient-level outcomes, as measured by percent of patients with any early refills at 12 months (primary); Aim 3: assess HIV providers’ satisfaction with prescribing LTOT (primary), as measured by mean satisfaction at 12 months; and Aim 4: assess HIV disease status among patients, as measured by undetectable viral load at 12 months (exploratory) and CD4 count (exploratory). Secondary RCT outcomes were obtained via provider self-report and patient self-report among patient participants enrolled in both the RCT and the cohort (). The RCT was implemented from September 2015 to December 2017. The patient cohort was recruited and assessed between July 2015 and February 2018. The overlap of the RCT and cohort study groups is depicted in . The TEACH study was approved by the institutional review boards at Boston University Medical Campus, Emory University and the Grady [Health System] Research Oversight Committee.

Figure 1 Venn diagram describing overlap between targeting effective analgesia in clinics for HIV (TEACH) RCT patient participants and observational cohort of patient participants.

Table 1 TEACH study outcomes

Cluster randomized controlled trial

Participants and recruitment

HIV physicians and advanced practice providers were recruited from September 2015 to December 2016 from two safety-net, hospital-based HIV clinics in Boston and Atlanta. Potential provider participants and their patients were identified by queries of the electronic medical record by the clinical data warehouse (CDW) at BMC and the Center For AIDS Research (CFAR) team at Emory University. Provider participant inclusion criteria included: (1) being an HIV physician or advanced practice provider (i.e. nurse practitioner or physician assistant) at the medical centers’ HIV clinics; and (2) being the main provider for ≥1 individual living with HIV who is receiving LTOT (defined as having received ≥3 opioid prescriptions ≥21 days apart within a 6-month period in the prior year). While tramadol is a schedule IV medication, reflecting a perception of less potential for abuse, it was included as a qualifying opioid for LTOT as it is an opioid. Provider participant exclusion criteria included: (1) being an investigator in this study; and (2) planning to leave the clinic <9 months from screening. In total, 41 providers were identified and all enrolled in the study. Patients receiving LTOT from physician participants (n = 187) were enrolled through a waiver of informed consent. The rationale for the waiver of informed consent was twofold. Because the trial was randomized at the level of the provider, it would have been logistically not possible for a provider who was receiving education, counseling, and access to a nurse care manager to selectively apply this knowledge and expertise to only certain patients. In addition, there was little risk to patients. These patient participants met the following eligibility criteria: (1) ≥18 years of age; (2) diagnosis of HIV infection from the EMR by ICD-9 codes or lab tests; (3) having received ≥3 opioid prescriptions ≥21 days apart within a 6-month period in the prior year from the study clinic site; and (4) having attended ≥1 visit to the enrollment sites within the prior 18 months. All patients who met the eligibility criteria for the clinical trial were allocated to the same treatment group (i.e. TEACH vs. control) as their provider. Study staff and clinician investigators reviewed the queried lists to confirm that those included were eligible for the study and correctly matched between patient and provider. The lists from each site were generated a second time near the end of the recruitment period to maximize the inclusion of all eligible providers and patients. Of the 187 participants enrolled into the RCT, 117 were simultaneously enrolled in the cohort (described below and ).

Research staff worked with clinic leadership to identify a regularly scheduled clinic meeting at which to present the study and enroll interested providers. Providers were informed ahead of the meeting that there would be a presentation about a new research study. The research teams then introduced the study at the regularly scheduled clinic meeting and invited eligible providers to enroll. It was reinforced that they could choose not to participate or discontinue participation in the study at any time, for any reason, with no penalty. Study staff followed up individually with providers who were unable to attend the clinic meetings to enroll them into the study. Provider enrollment is outlined in .

Research assessments

Providers completed 15-minute paper baseline and 12-month follow-up assessments, which included: demographics, training and practice characteristics, substance use among PLWH, practices for assessing and treating pain, and practices for managing use of prescribed opioids.Citation68,Citation71,Citation72 At follow-up, providers randomized to the intervention group also completed a brief evaluation assessment of the intervention. To ensure completion and minimize assessment bias, research staff were present to proctor providers as they completed surveys. Providers were compensated with a $100 gift card upon completion of each assessment. The paper assessment forms were double-entered into REDCap by research staff and any data entry discrepancies were resolved.Citation73

Randomization

After completing a baseline assessment, providers were randomized to either the control group or the year-long TEACH intervention. Randomization was stratified by site and patient volume (1–2, 3–6, 7–11, and 12+ patients). To ensure balance with respect to the number of providers in each group, the permuted blocks strategy was used with blocks of 2. Due to the nature of the intervention, neither provider participants nor the study team members were blinded to provider group assignment.

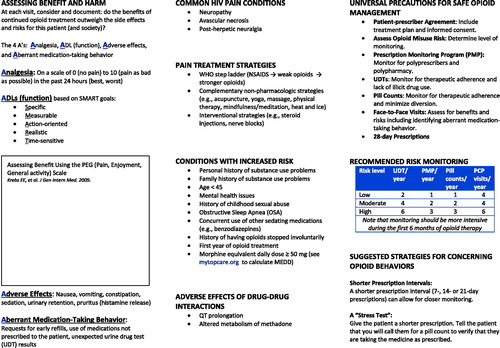

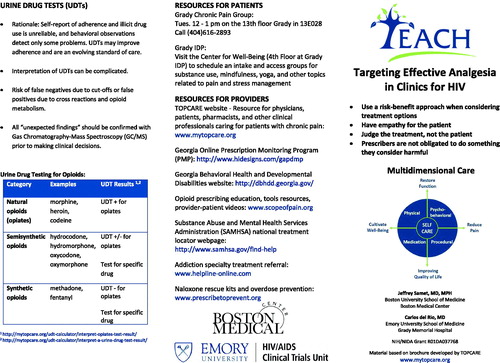

Control condition

At the clinic meeting when the study was introduced, all providers were given an informational brochure summarizing guidelines for LTOT and listing a web resource with electronic tools (Appendix).Citation8,Citation68 Those who were randomized to the control group did not receive an intervention beyond the information about the study and the corresponding brochure. The control group did not have access to the support of the TEACH intervention.

Intervention

The 12-month TEACH intervention consisted of: (1) a nurse care manager and electronic registry to assist with patient management; (2) opioid education and academic detailing; and (3) facilitated access to addiction specialists. TEACH was grounded in the Chronic Care Model (CCM) for chronic disease management,Citation64,Citation65 and based on the TOPCARE intervention and office-based addiction treatment (OBAT) model,Citation68,Citation74 both based in primary care clinics. The CCM model seeks to improve patient outcomes through integrative systems changes, including organizational support, clinical information systems, delivery system redesign, decision support, self-management support and community resources. The CCM has been found effective for the care of a number of chronic diseases (e.g. tobacco use, diabetes, and depression),Citation75–77 and has served as a theoretical basis for a collaborative care intervention for a program to treat opioid-dependent patients with buprenorphine at BMC and community health clinics.Citation74,Citation78 Central to this model is the use of a nurse care manager to provide support to providers. TOPCARE was a cluster-randomized clinical trial of nurse care management, an electronic registry, a single academic detailing session, and electronic decision support tools conducted in four safety-net primary care practices. TEACH was modeled after TOPCARE, with the following adaptations: this was conducted in an HIV clinic compared to a primary care clinic; TOPCARE lacked the ability to obtain patient-level outcomes (i.e. no patient cohort); an educational didactic session was added at the beginning of the intervention period; and providers received ≥2 academic detailing sessions throughout the intervention (vs. a single session in TOPCARE). In addition, reports that served as the basis for academic detailing from the electronic registry were updated to include clinic-wide averages for comparison, and summary tables of patients for each provider. Descriptions follow of the individual components of TEACH in order of implementation throughout the 12-month intervention window.

Didactic session

Within a few weeks of randomization, intervention providers received a 60-minute group didactic session from an expert on opioid prescribing.Citation69 Participants who were unable to join in person were given the opportunity to attend a live session via video conference. A case study tailored for each site was presented to engage providers in finding signs of nonmedical prescription opioid use, and devising treatment plans for complex situations with challenging patients. The opioid prescribing expert explained how to detect the non-medical use of prescription opioids, developed providers’ patient communication skills around this topic, and reviewed the study resource website (www.mytopcare.org) and brochure outlining opioid prescribing guidelines.

Collaboration with nurse care manager (NCM)

Each site hired a NCM with a background in HIV care. Both NCMs collaborated with providers in the intervention group throughout the year-long study period to conduct essential elements of guideline-driven care. They were introduced to the providers during the didactic sessions, and subsequently met with each provider to review their panel of patients receiving LTOT. The NCMs implemented opioid treatment agreements, UDTs, pill counts, and periodic checking of online prescription monitoring programs (PMPs), either directly or by assisting the provider depending on state regulations. The NCMs conducted an initial intake assessment for each patient, which included the following: a detailed medical, substance use, and social history; the current opioid misuse measure (COMM);Citation39 opioid risk tool (ORT);Citation79 and discussing and signing a treatment agreement. The NCM then followed-up regularly with patients regarding refills, pain assessments, UDTs, and pill counts, the frequency of which was determined by the patient’s risk level. Prior to the starting the intervention, the NCMs received extensive training from TOPCARE study nurses and study investigators in best practices to monitor opioids, deliver addiction care, and utilize the registry. During the intervention, the NCMs had the opportunity to discuss case management during weekly calls with co-investigators including opioid prescribing experts, an addiction specialist, and HIV providers.

Registry

The NCM utilized a web-based registry developed by the TOPCARE clinical research study team to record and view individual or aggregate information on opioid treatment agreements, UDTs, pill counts, and checking of online PMPs.Citation68 The registry was used for clinical purposes, and the data were not used in the RCT analysis. The registry also enabled the NCM to anticipate refills, ensure appropriate monitoring measures, and schedule follow-up appointments. The NCM regularly entered data into the registry at or after meetings with LTOT patients, and the registry would generate a note that could be easily copied and pasted into a patient encounter note in the electronic medical record. The registry also generated summary reports that were used in individual academic detailing sessions with intervention providers, to highlight high-risk LTOT patients. The following updates were made to the TOPCARE registry before initiating TEACH: adding an overview of all patients and their pertinent characteristics related to safe opioid prescribing (COMM score, UDTs), as well as a comparison of the provider’s panel to an aggregate of the providers in the rest of clinic.

Academic detailing

Intervention providers participated in two 30-minute individual academic detailing sessions throughout the year-long intervention, and were given the option of a third, booster session if desired. Session 1 was conducted by the opioid prescribing expert, the site’s NCM, and a co-investigator at each site who was designated the TEACH clinic leader, neither of whom specialized in opioid prescribing or addiction. Sessions 2 and 3 were conducted by the NCM and the TEACH clinic leader. At the academic detailing sessions, providers received a personalized folder prepared by the study staff and NCMs with registry-generated data on their LTOT patient panel (e.g. opioid risk assessment scores, completion of UDTs, and checking of online PMP). Electronic registry data provided clinic-level data on all the patients in the intervention as well as a summary of the provider’s panel. The NCM assisted in these sessions by providing specific cases and experiences from working with the patients. Providers were encouraged to utilize academic detailing sessions to discuss difficult cases and develop treatment plans with input from the intervention team.

Facilitated access to addiction specialist

The NCM encouraged and arranged referral of challenging patients with substance use disorders to addiction specialists affiliated with the HIV clinics when available. The study protocol did not dictate how such patients were managed; clinical decision-making remained in the hands of the provider, and treatment resources differed by site. In some cases, patients were transitioned from LTOT to buprenorphine for opioid use disorder, and the NCM continued oversight of treatment. As mentioned previously, a weekly meeting took place with study team investigators focused on the intervention, and provided an opportunity for the NCM to obtain regular assistance on any difficulties that had arisen, and the meetings took place throughout the duration of the intervention at both sites.

Quality assurance

The following measures were implemented in order to ensure the fidelity of the intervention. Prior to enrollment at each site, training occurred with the TEACH clinic leaders and NCMs via site visits, conference calls, and webinars. In addition, the TEACH NCMs shadowed the NCMs from the TOPCARE study. TEACH NCMs served as a resource for one another as well. Checklists were developed for academic detailing sessions to ensure that they were carried out consistently. During the weekly intervention meetings, the NCM filled out checklists documenting their interactions with intervention providers and TEACH clinic leaders documented any challenges the NCM had encountered.

Patient cohort

Cohort participants and recruitment

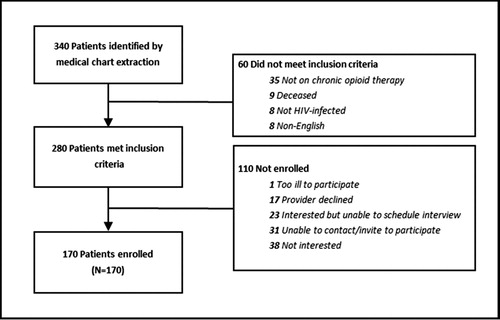

PLWH receiving LTOT (n = 170) were recruited into the TEACH cohort from July 2015 to December 2016 from two safety-net, hospital-based HIV clinics in Boston and Atlanta. Of the 170 participants recruited into the cohort, 117 were simultaneously enrolled in the RCT (). Potential patient cohort participants were identified by queries of the electronic medical record by the clinical data warehouse (CDW) at BMC, and the Center For AIDS Research (CFAR) at Emory University. Initial patient participant inclusion criteria included: (1) ≥18 years of age, (2) diagnosis of HIV infection by ICD-9 codes or lab tests, (3) having received ≥3 opioid prescriptions ≥21 days apart within a 6-month period in the prior year, and (4) having attended ≥1 visit to the medical center’s enrollment sites within the prior 18 months. Study staff and clinician investigators reviewed the queried lists extensively to confirm that those included were eligible for the study. The lists from each site were generated a second time near the end of the recruitment period to ensure the inclusion of all potentially eligible patients.

Research staff checked the HIV clinic schedule daily using the EMR and approached potentially eligible patients for screening after informing their clinical team. Those who did not frequently come in for appointments were contacted by phone or letters at other hospital appointments to invite them to participate. Patients were invited to participate in the observational cohort regardless of whether their provider enrolled in the RCT. If the patient was interested, the RA scheduled an appointment to meet. At the scheduled meeting, the RA formally screened the patient and assessed secondary eligibility criteria. As the initial identification of potential participants was conducted using EMR data, we conducted an additional screening for the following: (1) provision of contact information of two individuals to assist with follow-up, (2) possession of a home or mobile telephone, and (3) English speaking. Secondary exclusion criteria included: (1) plans to move from the area within 12 months, and (2) inability to consent or understand interviews. The screener collected information on age, gender, race, ethnicity, and language. If eligible and willing, research staff obtained written informed consent, recorded contact information, administered the baseline assessment, and provided participant compensation. TEACH patient cohort enrollment is outlined in .

Patient cohort research assessments

Patient cohort participants underwent 60- to 90-minute assessments administered by a research assistant (RA) at baseline and 12-month follow-up (). The 12-month assessment was similar to the baseline assessment, with minor modifications to demographics, pain treatments, satisfaction with pain treatment, health literacy, and aberrant medication use (ORBIT assessment added at 12 months but not included at baselineCitation80). Participants were compensated with $35 upon completion of the baseline assessment and $50 upon completion of the 12-month follow-up assessment. Patient assessment data was entered directly into REDCap and a study tracking system by the RA when interviewing patients. RAs reviewed all data at the end of each assessment, and all data were double-checked by an additional staff member at each site for quality assurance. RAs contacted study participants at 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months after baseline to verify contact information and remind them of the 12-month follow-up interview. Participants received birthday and holiday letters with giftcards to a coffee shop ($2) throughout the year thanking them for their participation.

Table 2 TEACH patient cohort assessment components

EMR data extraction

At the conclusion of the study intervention period, the CDW and CFAR teams extracted data from the EMR for both the RCT and the cohort at BMC and Emory, respectively. Extracted information included UDTs, medications, HIV viral load, CD4 count, and comorbidities.

To ensure quality data, the data management team and CFAR staff conducted thorough checks comparing data to the EMR from which they were pulled. For each outcome variable, 10% were checked for accuracy. Discrepancies were logged and discussed, and algorithms for data extraction were refined to fix the source of the error. To ensure we did not include duplicate medications, we manually checked all medications that could potentially be duplicates to determine if they should be counted or deleted. We considered medications to be potential duplicates if two prescriptions were for the same medication, had the same description, and if the ordering dates were less than 7 days from one another. The data management team manually reviewed and discussed the list of potential duplicates to identify actual duplicates or abnormal situations that the algorithm may not have identified.

Manual EMR review

In addition to the EMR extraction, research staff conducted manual EMR reviews at the conclusion of the study, as some data elements could not be accurately captured by extraction. This manual review included information on opioid treatment agreements, discontinuation of opioids and reasons, emergency department utilization, pill counts, evidence of and/or treatment for opioid use disorder, and other substance use/mental health disorder diagnoses. A standard operating procedure manual was created to ensure uniform recording of these variables, and staff conducting the medical chart reviews met with the rest of the research team and study investigators to resolve any questions.

Data management

RCT and cohort data were managed by the Biostatistics and Epidemiology Data Analytics Center at Boston University School of Public Health and research staff at BMC. The cohort’s project website and study data were located on a secure server within the Boston University Medical Center (BUMC) domain. Access to the system was protected via secure logins and all data transmissions were encrypted using secure socket layering (SSL). All web-forms were protected using SSL encryption technology and files were protected by electronic firewalls that restricted access to designated users. Identifiers needed to track participants were kept separate from research data.

Measures

The primary outcome for Aim 1, improving HIV providers’ adherence to LTOT guidelines, will be measured by occurrence of ≥2 UDTs between the providers’ randomization date and 12-months. In the event that a confirmatory test is conducted to verify the results of a toxicology test, it will be considered part of the original test rather than a second test.

The primary outcome for Aim 2, improving patient-level outcomes, will be the percent of patients with any early refills between the providers’ randomization date and 12 months. Each opioid prescription will be analyzed using the instructions and total number of doses in order to determine an expected prescription duration in days, assuming maximum number of pills taken per day. Early refills are defined as prescriptions that are filled more than 3 days prior to the expected refill date.

The primary outcome for Aim 3, improving HIV providers' satisfaction with prescribing LTOT, will be the mean satisfaction score in the intervention group compared to the control group at the 12-month assessment. The question used is, “How satisfied are you in managing chronic opioid therapy in your HIV-infected patients who are on chronic opioid therapy for pain?” with responses ranging from 1 – “not at all” to 10 – “extremely”.

The primary outcome for Aim 4, improving virologic control among patients, will be the percent of patients with undetectable HIV viral load (<200 copies/mL) at the test closest to 12-month follow-up.

Analytic methods

Descriptive statistics will be calculated for patient-specific and provider-specific variables at baseline and the 12-month follow-up. At baseline, all variables will be assessed to ascertain important differences across the two randomized arms. Spearman correlation coefficients will be obtained to identify pairs of possible collinear variables (r > 0.4) and would therefore not be included together in regression analyses. In addition, the variance inflation factor (VIF) will be assessed for each covariate and randomization group to detect possible correlation. This study will use an intent-to-treat analysis including all participants according to their randomized assignment.

Randomization and the intervention occur at the provider level while the unit of observation includes both the individual patients receiving LTOT and the providers. Thus, analyses of patients must account for clustering by the provider. The primary analysis, evaluating the effect of the intervention on the binary study outcomes, will use generalized estimating equations (GEE) and logistic regression models with empirical standard errors to account for clustering by providers. The models will include the randomization group as the main independent variable and control for the randomization’s stratification factors, site, and provider volume in order to improve efficiency. In addition, the models will control for any important baseline provider or patient characteristics that differ between groups in order to avoid confounding. Potential patient-specific confounders of interest include demographics, age, gender, and hepatitis C status. Potential provider-specific covariates include those provider characteristics such as age, gender, and provider type (e.g. physician vs. advanced practice provider). For the outcomes of provider satisfaction and confidence at 12 months, we will use multiple linear regression models. If the distribution is skewed, transformations will be considered or a median regression model will be used. The secondary outcome, number of early refills, will be analyzed as count data using Poisson regression; if the variance exceeds the mean, a negative binomial regression model will be used. Analyses will be conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

We will test for differences in baseline characteristics between participants lost to follow-up and those who are not. Missing data patterns will be evaluated, including the percentage of those missing for each variable and the distribution of the number of variables missing for subjects. We will use multiple imputation (with 25 generated complete datasets) to account for missing outcome data. Variables used for imputation of patient-level outcomes will include gender, age, depression, hazardous drinking, drug use, race, Hispanic, BMI, CD4 cell count, HIV viral load, Charlson Comorbidity Index,Citation81 randomization group, stratification variables, and baseline value of the outcome. For patient-level outcomes, data will be imputed separately by provider. Variables used for imputation of provider-level outcomes included gender, years of practice in HIV care, patient volume, site, randomization group, and baseline value of the outcome. All analyses will be conducted using SAS version 9.3.

Power calculations

Power calculations to define the limits of the study were conducted as follows. The calculations assumed a two-sided test, with a significance level of 0.05. It was expected that 35 total physicians would be enrolled in the study, with an average of five eligible patients per physician for a total of 175 patients. We expected the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) will be <0.10 for the outcomes of interest, and conservatively assume a value of 0.10 in the following calculations. Calculations for binary outcomes were based on a chi-square test with continuity correction and continuous outcomes are based on the two sample t-test, with estimates adjusted for clustering based on the inflation factor (also referred to as the design effect). For the outcome ≥2 UDTs, the minimum detectable difference is 28% (i.e. 26% vs. 54% in the control and intervention groups, respectively). For the outcome any early refills, the minimum detectable difference is 27% (i.e. 46% vs. 19% in the control and intervention groups, respectively). For the outcome physician satisfaction, the minimum detectable difference is 2.5 in mean satisfaction scores (e.g. 7.1 vs. 4.6 for the intervention and control groups).

Discussion and impact

The TEACH study tests the effectiveness of a collaborative care intervention on HIV providers’ opioid prescribing for chronic pain. The intervention seeks to increase providers’ adherence to current guidelines for care with the use of LTOT, prevent nonmedical use of prescription opioids among patients, and heighten physician and patient satisfaction in regard to this dimension of care. The TEACH study will provide patient and provider-level effects of an intervention to improve opioid prescribing for chronic pain in HIV-clinics. The results from this cluster randomized trial design should inform delivery of care for PLWH who are on LTOT for chronic pain and provide a “blueprint” for dissemination.

Clinical trial registration details

These studies were registered with ClinicalTrials.gov through the National Institutes of Health – Targeting Effective Analgesia in Clinics for HIV – Intervention, NCT02564341; and Targeting Effective Analgesia in Clinics for HIV – Patient Cohort, NCT02525731.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The TEACH study was approved by the institutional review boards at Boston University Medical Campus and Emory University.

Notes on Contributors

Marlene C. Lira, is a Research and Education Project Manager at Boston Medical Center, and manages clinical and policy research related to substance use, as well as training initiatives about addiction for physicians. She is currently pursuing her MPH in Epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Judith I. Tsui, M.D., M.P.H., is a board certified physician at Harborview and a University of Washington Associate Professor of General Internal Medicine. Her research has elucidated complications of substance abuse and related viral infections, as well as the positive impact of addiction treatment on hepatitis C.

Jane M. Liebschutz, MD, MPH is Chief of General Internal Medicine at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Her previous research, including the TOPCARE study, has focused on safe opioid prescribing.

Jonathan Colasanti, MD, MPH is an Assistant Professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory University.

Christin Root, is the Associate Director of Programs in the Hubert Department of Global Health and the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University.

Debbie M. Cheng, ScD, is Professor of Biostatistics and has been on the faculty at the Boston University School of Public Health since 2002. She collaborates with investigators at the Boston University School of Medicine on numerous projects in the areas of substance abuse and HIV research.

Alexander Y. Walley, M.D., M.Sc., is an Associate Professor of Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine and the Director of the Boston Medical Center Addiction Medicine Fellowship program. He provides primary care and office-based addiction treatment for patients with HIV at Boston Medical Center and methadone maintenance treatment at Health Care Resource Centers.

Meg Sullivan, MD was the Clinical Director of HIV Services at Boston Medical Center (BMC). She has focused on models for successful engagement and retention of HIV positive patients into ongoing medical care.

Christopher Shanahan, MD, MPH, is an Assistant Professor at Boston University School of Medicine. He is the Director of the Community Medicine Unit within the Section of General Internal Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine. He was the former Associate Medical Director for the Massachusetts Screening Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment Program.

Kristen O'Connor, BCN, was a TEACH Nurse Care Manager at Boston Medical Center.

Catherine Abrams, BSN, was a TEACH Nurse Care Manager at Grady.

Leah S. Forman, MPH, is a Statistical Programmer and Data Manager in the Biostatistics and Epidemiology Data Analytics Center at Boston University School of Public Health.

Christine Chaisson, MPH, is the Director of Translational Research at Optum Labs. She previously served as the Director of the Biostatistics and Epidemiology Data Analytics Center at the Boston University School of Public Health.

Carly Bridden, MA, MPH is the Clinical Research Director for the Clinical Addiction Research and Education (CARE) Unit at Boston Medical Center.

Melissa C. Podolsky, was the Project Coordinator on the TEACH study at Boston Medical Center. She is currently pursuing her MPH at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University.

Kishna Outlaw is a Research Interviewer at Emory University.

Catherine E. Harris is a Research Interviewer in the Department of Global Health and post-baccalaureate student at the Grady Nia Project in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Emory.

Wendy S. Armstrong, MD, FIDSA, FACP is the Vice Chair of Education and Integration and Professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory University School of Medicine. She has been active in the Emory Center for AIDS Research and established the Emory CFAR HIV Specimen Repository.

Carlos del Rio, MD is the Hubert Professor and Chair of the Department of Global Health and Professor of Epidemiology at the Rollins School of Public Health and Professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory University School of Medicine. He is also co-Director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research (CFAR).

Jeffrey H. Samet, MD, MA, MPH, is Chief of General Internal Medicine and the John T. Noble Professor of Medicine at Boston University Schools of Medicine and Public Health. His research focuses on the intersection of HIV and substance use.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the HIV providers and their patients who enrolled in this study. We are grateful to Linda Rosen at Boston Medical Center’s Clinical Data Warehouse, and Minh Nguyen and Jeselyn Rhodes of the Emory Center For AIDS Research, for their assistance with data extraction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marlene C. Lira

Marlene Lira, BA, is Research and Education Project Manager at Boston Medical Center, and manages clinical and policy research related to substance use, as well as training initiatives about addiction for physicians. She is currently pursuing her MPH in Epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Judith I. Tsui

Judith Tsui, M.D., M.P.H., is a board certified physician at Harborview and a University of Washington Associate Professor of General Internal Medicine. Her research has elucidated complications of substance abuse and related viral infections, as well as the positive impact of addiction treatment on hepatitis C.

Jane M. Liebschutz

Jane Liebschutz, MD, MPH is Chief of General Internal Medicine at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Her previous research, including the TOPCARE study, has focused on safe opioid prescribing.

Jonathan Colasanti

Jonathan Colasanti, MD, MPH is Assistant Professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory University and Associate Medical Director of the Infectious Diseases Program at the Grady Health System.

Christin Root

Christin Root, is the Associate Director of Programs in the Hubert Department of Global Health and the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University.

Debbie M. Cheng

Debbie M. Cheng, ScD, is Professor of Biostatistics and has been on the faculty at the School of Public Health since 2002. She collaborates with investigators at the Boston University School of Medicine on numerous projects in the areas of substance abuse and HIV research.

Alexander Y. Walley

Alexander Y. Walley, M.D., M.Sc., is an Associate Professor of Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine and director of the Boston Medical Center Addiction Medicine Fellowship program.

Meg Sullivan

Meg Sullivan, MD is the Clinical Director of HIV Services at Boston Medical Center (BMC). She has focused on models for successful engagement and retention of HIV positive patients into ongoing medical care.

Christopher Shanahan

Christopher Shanahan, MD is an Assistant Professor at Boston University School of Medicine. He is the Director of the Community Medicine Unit within the Section of General Internal Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine. He was the former Associate Medical Director for the Massachusetts Screening Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment Program.

Kristen O’Connor

Kristen O’Connor, BCN, is a TEACH Nurse Care Manager at Boston Medical Center.

Catherine Abrams

Catherine Abrams, BSN, is a TEACH Nurse Care Manager at Grady.

Leah S. Forman

Leah Forman, MPH, is a Statistical Programmer and Data Manager in the Biostatistics and Epidemiology Data Analytics Center at Boston University School of Public Health.

Christine Chaisson

Christine Chaisson, MPH, is the Director of Translational Research at Optum Labs. She previously served as the Director of the Data Coordinating Center at the Boston University School of Public Health.

Carly Bridden

Carly Bridden, MA, MPH is the Clinical Research Director for the Clinical Addiction Research and Education (CARE) Unit at Boston Medical Center.

Melissa C. Podolsky

Melissa Podolsky, BA is the Project Coordinator on the TEACH study at Boston Medical Center. She is currently pursuing her MPH at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University.

Kishna Outlaw

Kishna Outlaw is a Research Interviewer at Emory University.

Catherine E. Harris

Catherine Harris is a Research Interviewer in the Department of Global Health and post-baccalaureate student at the Grady Nia Project in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Emory.

Wendy S. Armstrong

Wendy Armstrong, MD, FIDSA, FACP is the Vice Chair of Education and Integration and Professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory University School of Medicine. She is the Medical Director of the Grady Infectious Diseases Program and is an active investigator of the Emory Center for AIDS Research having established the Emory CFAR HIV Specimen Repository.

Carlos del Rio

Carlos del Rio, MD is the Hubert Professor and Chair of the Department of Global Health and Professor of Epidemiology at the Rollins School of Public Health and Professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory University School of Medicine. He is also co-Director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research (CFAR). His research focuses on improving outcomes for Persons Living with HIV with a particular focus on persons who use drugs.

Jeffrey H. Samet

Jeffrey Samet, MD, MA, MPH, is Chief of General Internal Medicine and the John T. Noble Professor of Medicine at Boston University Schools of Medicine and Public Health. His research focuses on the intersection of HIV and substance use.

References

- Volkow N, Benveniste H, McLellan AT. Use and misuse of opioids in chronic pain. Annu Rev Med. 2018;69:451–465.

- Williams AR, Bisaga A. From AIDS to opioids — how to combat an epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):813–815. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1604223.

- Stitzer ML, Schwartz RP, Bigelow GE. Prescription opioids: new perspectives and research on their role in chronic pain management and addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173 Suppl 1:S1–S3. doi:S0376-8716(16)31025-0.

- Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:154–163.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug abuse warning network, 2011: National estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. 2013;(SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39.

- Martins SS, Sarvet A, Santaella-Tenorio J, Saha T, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Changes in us lifetime heroin use and heroin use disorder: prevalence from the 2001-2002 to 2012-2013 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:445–455.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — united states, 2016 . https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm. Updated 2016. Accessed January 2, 2018.

- Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10(2):113–130.e22.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral and clinical characteristics of persons receiving medical care for HIV infection medical monitoring project, United States 2013 cycle. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-hssr-mmp-2013.pdf. Updated January 2016. Accessed December 19, 2018, HIV Surveillance Special Report 16.

- Jiao JM, So E, Jebakumar J, George MC, Simpson DM, Robinson-Papp J. Chronic pain disorders in HIV primary care: clinical characteristics and association with healthcare utilization. J Int Assoc Study Pain. 2016;157(4):931–937.

- Parker R, Stein DJ, Jelsma J. Pain in people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. JIAS. 2014;17:18719.

- Merlin J, Westfall A, Chamot E, et al. The relationship of pain to physical function in patients with HIV: an underappreciated phenomenon. Pain. 2012;45(2):404–405.

- Miaskowski C, Penko JM, Guzman D, Mattson JE, Bangsberg DR, Kushel MB. Occurrence and characteristics of chronic pain in a community-based cohort of indigent adults living with HIV infection. J Pain. 2011;12(9):1004.

- Merlin JS, Cen L, Praestgaard A, et al. Pain and physical and psychological symptoms in ambulatory HIV patients in the current treatment era. J Pain Symp Manage. 2012;43(3):638.

- Breitbart W, McDonald MV, Rosenfeld B, et al. Pain in ambulatory AIDS patients. I: pain characteristics and medical correlates. Pain. 1996;68:315.

- Dobalian A, Tsao JC, Duncan RP. Pain and the use of outpatient services among persons with HIV: results from a nationally representative survey. Med Care. 2004;42(2):129–138.

- Vogl D, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, et al. Symptom prevalence, characteristics, and distress in AIDS outpatients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18(4):253.

- Fantoni M, Ricci F, Del Borgo C, et al. Multicentre study on the prevalence of symptoms and symptomatic treatment in HIV infection. central Italy PRESINT group. J Palliat Care. 1997;13(2):9–13.

- Larue F, Fontaine A, Colleau SM. Underestimation and undertreatment of pain in HIV disease: multicentre study. BMJ. 1997;314:23–28.

- Namisango E, Harding R, Atuhaire L, et al. Pain among ambulatory HIV/AIDS patients: Multicenter study of prevalence, intensity, associated factors, and effect. J Pain. 2012;13(7):704.

- Richardson J, Barkan S, Cohen M, et al. Experience and covariates of depressive symptoms among a cohort of HIV infected women. Soc Work Health Care. 2001;32(4):93–111.

- Lee KA, Gay C, Portilla CJ, et al. Symptom experience in HIV-infected adults: a function of demographic and clinical characteristics. J Pain Symp Manage. 2009;38(6):882–892.

- Del Borgo C, Izzi I, Chiarotti F, et al. Multidimensional aspects of pain in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2001;15(2):95.

- Frich LM, Borgbjerg FM. Pain and pain treatment in AIDS patients: a longitudinal study. J Pain Symp Manage. 2000;19(5):339–347.

- Merlin JS, Zinski A, Norton WE, et al. A conceptual framework for understanding chronic pain in patients with HIV. Pain Pract. 2013;14(3):207–216.

- Silverberg MJ, Ray GT, Saunders K, et al. Prescription long-term opioid use in HIV-infected patients. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(1):39–46.

- Edelman EJ, Gordon K, Becker WC, et al. Receipt of opioid analgesics by HIV-infected and uninfected patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(1):82–90.

- Merlin JS, Tamhane A, Starrels JL, Kertesz S, Saag M, Cropsey K. Factors associated with prescription of opioids and co-prescription of sedating medications in individuals with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(3):687–698.

- Becker WC, Gordon K, Jennifer Edelman E, et al. Trends in any and high-dose opioid analgesic receipt among aging patients with and without HIV. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(3):679–686.

- Gaither JR, Goulet JL, Becker WC, et al. Guideline-concordant management of opioid therapy among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and uninfected veterans. J Pain. 2014;15(11):1130–1140.

- Turner AN, Maierhofer CT, Funderburg NT, et al. High levels of self-reported prescription opioid use by HIV-positive individuals. AIDS Care. 2016;28:1559–1565.

- Park TW, Nelson K, Xuan Z, Lasser KE, Liebschutz JM, Saitz R. The association between benzodiazepine prescription and aberrant drug behaviors in primary care patients receiving chronic opioid therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;146:e61–e62.

- Vijayaraghavan M, Penko J, Bangsberg DR, Miaskowski C, Kushel MB. Opioid analgesic misuse in a community-based cohort of HIV-infected indigent adults. JAMA Internal Med. 2013;173(3):235–237.

- Hansen L, Penko J, Guzman D, Bangsberg DR, Miaskowski C, Kushel MB. Aberrant behaviors with prescription opioids and problem drug use history in a community-based cohort of HIV-infected individuals. J Pain Symp Manage. 2011;42(6):893–902.

- Robinson-Papp J, Elliott K, Simpson DM, Morgello S, Manhattan HIV Brain Bank. Problematic prescription opioid use in an HIV-infected cohort: the importance of universal toxicology testing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(2):187–193.

- Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Donaghy KB, Portenoy RK. Pain and aberrant drug-related behaviors in medically ill patients with and without histories of substance abuse. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:173–181.

- Barry DT, Goulet JL, Kerns RK, et al. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids and pain in veterans with and without HIV. Pain. 2011;152(5):1133–1138.

- Colasanti J, Lira MC, Cheng DM, et al. Chronic opioid therapy in HIV-infected patients: patients’ perspectives on risks, monitoring and guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:291–297

- Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, et al. Development and validation of the current opioid misuse measure. Pain. 2007;130(1–2):144–156.

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2001;58(8):721–728.

- Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):367–387.

- Tsui JI, Cheng DM, Coleman SM, et al. Pain is associated with heroin use over time in HIV-infected Russian drinkers. Addiction. 2013;108(10):1779–1787.

- Merlin JS, Westfall AO, Raper JL, et al. Pain, mood, and substance abuse in HIV: implications for clinic visit utilization, ART adherence, and virologic failure. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:154–170.

- Tsao JC, Dobalian A, Stein JA. Illness burden mediates the relationship between pain and illicit drug use in persons living with HIV. Pain. 2005;119(1–3):124–132.

- Tsao JC, Stein JA, Ostrow D, Stal RD, Plankey MW. The mediating role of pain in substance use and depressive symptoms among multicenter AIDS cohort study (MACS) participants. Pain. 2011;08:24.

- Morasco BJ, Gritzner S, Lewis L, Oldham R, Turk DC, Dobscha SK. Systematic review of prevalence, correlates, and treatment outcomes for chronic non-cancer pain in patients with comorbid substance use disorder. Pain. 2011;152(3):488–497.

- Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos RH. Pain and use of alcohol to manage pain: prevalence and 3-year outcomes among older problem and non-problem drinkers. Addiction. 2005;100(6):186–777.

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope, emotional distress and alcohol use and abuse: a ten-year model. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62(2):190–198.

- Merlin JS, Long D, Becker WC, et al. The association of chronic pain and long-term opioid therapy with HIV treatment outcomes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018:79:77–82.

- Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Gallagher RM, Barth KS, Ross JT, Oslin DW. The association between chronic pain and prescription drug abuse in veterans. Pain Med. 2009;10(3):531–536.

- Novak SP, Herman-Stahl M, Flannery B, Zimmerman M. Physical pain, common psychiatric and substance use disorders, and the non-medical use of prescription analgesics in the united states. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100(1–2):63–70.

- Bruce RD, Merlin J, Lum PJ, et al. 2017 HIVMA of IDSA clinical practice guideline for the management of chronic pain in patients living with HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:e1–e37.

- Carroll JJ, Colasanti J, Lira MC, del Rio C, Samet JH. HIV physicians and chronic opioid therapy: it’s time to raise the bar. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:1057–1061.

- Vijayaraghavan M, Penko J, Guzman D, Miaskowski C, Kushel MB. Primary care providers' views on chronic pain management among high-risk patients in safety net settings. Pain Med. 2012;13:1141–1148.

- Lum PJ, Little S, Botsko M, et al. Opioid-prescribing practices and provider confidence recognizing opioid analgesic abuse in HIV primary care settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S91–S97.

- Anderson D, Zlateva I, Khatri K, Ciaburri N. Using health information technology to improve adherence to opioid prescribing guidelines in primary care. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(6):573–579.

- Wang J, Christo PJ. The influence of prescription monitoring programs on chronic pain management. Pain Physician. 2009;12(3):507–515.

- Ceasar R, Chang J, Zamora K, et al. Primary care providers’ experiences with urine toxicology tests to manage prescription opioid misuse and substance use among chronic noncancer pain patients in safety net health care settings. Subst Abuse. 2016;37(1):154–160.

- Jacobs SC, Son EK, Tat C, Chiao P, Dulay M, Ludwig A. Implementing an opioid risk assessment telephone clinic: outcomes from a pharmacist-led initiative in a large veterans health administration primary care clinic, December 15, 2014–March 31, 2015. Subst Abuse. 2016;37(1):15–19.

- Jamison RN, Ross EL, Michna E, Chen LQ, Holcomb C, Wasan AD. Substance misuse treatment for high-risk chronic pain patients on opioid therapy: a randomized trial. Pain. 2010;150(3):390–400.

- Lange A, Lasser KE, Xuan Z, et al. Variability in opioid prescription monitoring and evidence of aberrant medication taking behaviors in urban safety-net clinics. Pain. 2015;156(2):335–340.

- Wakeland W, Nielsen A, Schmidt TD, et al. Modeling the impact of simulated educational interventions on the use and abuse of pharmaceutical opioids in the united states: a report on initial efforts. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(1 Suppl):74S–86S.

- Wiedmer NL, Harden PS, Isabelle PD, Arndt IO, Gallagher RM. The opioid renewal clinic: a primary care, managed approach to opioid therapy in chronic pain patients at risk for substance abuse. Pain Med. 2007;8(7):573–584.

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Improving outcomes in chronic illness. Manage Care Q. 1996;4(2):12–25.

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–1779.

- Ducharme LJ, Chandler RK, Harris AHS. Implementing effective substance abuse treatments in general medical settings: mapping the research terrain. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:110–118.

- Merlin JS, Bulls HW, Vucovich LA, Edelman EJ, Starrels JL. Pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments for chronic pain in individuals with HIV: a systematic review. AIDS Care. 2016;28:1506–1515.

- Lasser KE, Shanahan C, Parker V, et al. A multicomponent intervention to improve primary care provider adherence to chronic opioid therapy guidelines and reduce opioid misuse: a cluster randomized controlled trial protocol. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:101–106.

- Liebschutz JM, Xuan Z, Shanahan CW, et al. Improving adherence to long-term opioid therapy guidelines to reduce opioid misuse in primary care: a cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Int Med. 2017;177(9):1265–1272.

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1–49.

- Fox AD, Kunis HV, Starrels JL. Which skills are associated with residents' sense of preparedness to manage chronic pain? J Opioid Manage. 2012;8(5):328–336.

- Weiss L, Egan JE, Botsko M, Netherland J, Fiellin DA, Finkelstein R. The BHIVES collaborative: organization and evaluation of a multisite demonstration of integrated buprenorphine/naloxone and HIV treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S7—S13.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381.

- LaBelle CT, Choongheon Han S, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): Statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. JSAT. 2016;60:6–13.

- Joseph AM, Fu SS, Lindgren B, et al. Chronic disease management for tobacco dependence: a randomized, controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(21):1894–1900.

- Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–2620.

- Piatt GA, Orchard TJ, Emerson S, et al. Translating the chronic care model into the community: results from a randomized controlled trial of a multifaceted diabetes care intervention. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(4):811–817.

- Alford DP, Labelle CT, Kretsch N, et al. Collaborative care of opioid-addicted patients in primary care using buprenorphine: five-year experience. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):425–431.

- Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the opioid risk tool. Pain Med. 2005;6(6):432–442.

- Larance B, Bruno R, Lintzeris N, et al. Development of a brief tool for monitoring aberrant behaviours among patients receiving long-term opioid therapy: the opioid-related behaviours in treatment (ORBIT) scale. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;159:42–52.

- Sundararajan V, Henderson T, Perry C, Muggivan A, Quan H, Ghali WA. New ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(12):1288–1294.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse: Seek, Test, Treat and Retain Initiative. HIV/HCV/STI testing status and organizational testing practices questionnaire. http://www.drugabuse.gov/researchers/research-resources/data-harmonization-projects/seek-test-treat-retain/addressing-hiv-among-vulnerable-populations. Updated 2013.

- Cleeland CS. Brief pain inventory: short form. 1991.

- Rosenblum A, Joseph H, Fong C, Kipnis S, Cleland C, Portenoy RK. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain among chemically dependent patients in methadone maintenance and residential treatment facilities. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2370–2378.

- Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(5):309–318.

- Gunnarsdottir S, Donovan HS, Serlin RC, Voge C, Ward S. Patient-related barriers to pain management: the barriers questionnaire II (BQ-II). Pain. 2002;99(3):385–396.

- Zallman L, Rubens SL, Saitz R, Samet JS, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Liebschutz J. Attitudinal barriers to analgesic use among patients with substance use disorders. Pain Res Treat. 2012;2012:1–7.

- Anderson LA, Dedrick RF. Development of the trust in physician scale: a measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychol Rep. 1990;67(3 Pt 2):1091–1100.

- Thom DH, Ribisl KM, Stewart AL, Luke DA. Further validation and reliability testing of the trust in physician scale. The Stanford trust study physicians. Med Care. 1999;37(5):510–517.

- Hall MA, Zheng B, Dugan E, et al. Measuring patients' trust in their primary care providers. Med Care Res Rev. 2002;59(3):293–318.

- Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Saitz R, et al. Identifying prescription opioid use disorder in primary care: diagnostic characteristics of the current opioid misuse measure (COMM). Pain. 2011;152(2):397–402.

- Ashrafioun L, Bohnert AS, Jannausch M, Ilgen MA. Evaluation of the current opioid misuse measure among substance use disorder treatment patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;55:15–20.

- Larance B, Campbell G, Peacock A, et al. Pain, alcohol use disorders and risky patterns of drinking among people with chronic non-cancer pain receiving long-term opioid therapy. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2016;162:79–87.

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, O'Brien C, Woody GE. An improved diagnostic instrument for substance abuse patients, the addition severity index. J Nervous Mental Dis. 1980;168:26–33.

- Institute of Behavioral Research. TCU drug screen V. 2014.

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT the Alcohol use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. 2nd ed. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland, 2001:41.

- Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):596–607.

- HIV/AIDS Treatment Adherence, Health Outcomes and Cost Study Group. THe HIV/AIDS treatment adherence, health outcomes and cost study: conceptual foundations and overview. AIDS Care. 2004;S1:S6–S21.

- Tilton SR. Review of the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI). News Notes. 2008;48(2):1–3.

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg P, Jacobs G. Manual for the state-trait anxiety scale. Consulting Psychologists. 1983.

- Herge WM, Landoll RR, La Greca RE, Allen NB. Cneter for epidemiological studies depression scales (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging. 2013:12;366–367.

- Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB. Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging. 1997;12(2):277.

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). National Center for PTSD. 2010.

- Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588–594.

- Selim AJ, Rogers W, Fleishman JA, et al. Updated U.S. population standard for the veterans RAND 12-item health survey (VR-12). Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):43–52.

- Berry SH. HCSUS baseline questionnaire. http://www.rand.org/health/projects/hcsus/Base.html. Updated 2002.

- Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, Crystal S, et al. Coping, conflictual social interactions, social support, and mood among HIV-infected person. Am J Commun Psychol. 2000;28(4):421–453.

- Hays RD, Cunningham WE, Ettl MK, Beck CK, Shapiro MF. Health related quality of life in HIV disease. Assessments. 1995;2(4):363–380.