ABSTRACT

The ability to mentalize is an important developmental capacity that facilitates effective social and emotional functioning. Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT), which aims to improve mentalizing capacity, is widely used in adults and in parent-infant therapy, but adaptations of MBT for middle childhood are less well documented. A systematic search of key databases was carried out using a PICO model. Papers were included if they explicitly described a mentalization-based approach to work with children aged between 6 and 12 and/or their caregivers. Where outcomes were reported, quality was assessed. A narrative synthesis of the literature was conducted. Sixty-two publications were included, reporting on 29 unique mentalization-informed interventions for middle childhood. Although the majority were formulated as direct therapeutic work with children and their families, several MBT interventions work with whole systems, such as schools or children’s social care. Only 22 papers reported outcomes and many were of poor quality, lacking in assessment of child mentalizing or child-reported outcomes. A broad range of mentalization-based interventions are available for middle childhood, demonstrating wide-reaching applicability. Better quality research is needed to examine the evidence base for these treatments.

Introduction

Mentalization is “the ability to understand the actions by both other people and oneself in terms of thoughts, feelings, wishes and desires” (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016, p. 3). This capacity is crucial to our ability to regulate emotions and behaviors, as well as the way in which we form and maintain social relationships (Allen et al., Citation2008). It has been shown to be a resilience-promoting factor for those who have experienced early maltreatment and abuse (Ensink et al., Citation2014), and difficulties with mentalizing have been associated with a wide range of psychopathologies (Sharp & Venta, Citation2012).

A parent’s capacity to mentalize (operationalized as “Parental Reflective Functioning”, or PRF) has been shown to be a critical aspect of sensitive parenting (M. A. J. Zeegers et al., Citation2017). Parents with higher PRF have been shown to tolerate distress in their children better (Rutherford et al., Citation2013), have better communication with their children and more positive parenting skills (Rostad & Whitaker, Citation2016), and are better able to manage stressful situations with their child without resorting to over-controlling behavior (Borelli et al., Citation2016). Empirical studies have demonstrated that PRF plays an important part in promoting secure attachments, greater self-esteem, and social competence in children (Berube-Beaulieu et al., Citation2016; Borelli et al., Citation2012).

As a concept rooted in developmental psychology and the study of social cognition, research over the last 25 years has examined how the capacity to mentalize develops over time (Midgley & Vrouva, Citation2012). Whilst a large body of research has examined mentalizing in the early years, and during adolescence, there has been a relative absence of attention to the development of mentalizing capacity in middle childhood. The term “middle childhood” refers to a period of children’s lives between the ages of approximately 6 to 12, where significant developments take place in children’s cognitive, emotional and social lives, as they make the transition from early childhood into early adolescence (Cincotta, Citation2008). Ensink and Mayes (Citation2010) note that “a major obstacle to advancing our knowledge regarding the development of children’s mentalising after the preschool period has been the lack of reliable measures and procedures” (p. 317). Some researchers have attempted to address this gap through the development of a range of measures, including the child reflective functioning scale (Vrouva et al., Citation2012), to assess RF in children aged 8–12. This has led to a greater understanding of the role of mentalizing difficulties in a range of psychopathologies in childhood and adolescence (Sharp & Venta, Citation2012), as well as in internalizing and externalizing difficulties in children more generally (Halfon & Bulut, Citation2017). However, despite this work, the topic of middle childhood remains relatively unexamined in the developmental literature about the capacity to mentalize.

Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT)

Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT) was developed in the 1990s as a treatment for patients with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). Whether delivered in an individual or a group format, the aim of treatment has usually been framed as trying to increase the resilience of individuals’ mentalizing capacities (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016). Having developed out of a psychoanalytic tradition, MBT is also an integrative approach, and shares with CBT a more structured approach and a focus on social cognitions (Goodman et al., Citation2016). Studies have also demonstrated that a range of different psychotherapies may result in improvements in the individual’s reflective functioning (RF), even when the intervention is not explicitly framed as mentalization-based (Montgomery-Graham, Citation2016; Staines et al., Citation2019).

However, what distinguishes MBT as a form of treatment is the emphasis on promoting mentalizing as a primary target of the intervention. The approach includes a particular attention to arousal levels within the session, with a focus on identifying moments of “mentalizing vulnerability”, or where the patient’s capacity for mentalizing breaks down. Interventions in MBT are carefully matched to the moment-by-moment mentalizing capacity of the client, with the therapist drawing on a spectrum of interventions that include empathy and validation; clarification, exploration and challenge; and mentalization of the therapeutic relationship itself. Throughout this process, the therapist is encouraged to maintain a “mentalizing stance”, which includes taking a “not-knowing” position and paying attention to moments when the therapist’s own capacity to mentalize is lost. As MBT has developed and become a treatment not only for patients with BPD, but also those with a range of other presenting problems, these core elements of MBT as an intervention have largely remained constant (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016).

Adaptations of MBT for working with children, young people and families began within a few years of the model emerging (Midgley & Vrouva, Citation2012). Given the understanding that parental reflective functioning is a core mechanism in the transmission of secure attachment, there has been a particular interest in developing mentalization-based early years interventions that promote parental mentalizing, such as Minding the Baby (Ordway et al., Citation2014), Reflective Parenting (Etezady & Davis, Citation2012) or Mothering from Inside Out (Suchman et al., Citation2016). Alongside this, there have been adaptations “downwards” of adult MBT for adolescents with emerging personality disorders, including adolescents who self-harm (Rossouw & Fonagy, Citation2012) or those with conduct disorder (Taubner & Thorsten-Christian Gablonski, Citation2019). But while mentalization-based interventions targeted at parents and infants or adolescents have increased, recent systematic reviews suggest that interventions with children aged 6–12 appear to be rather under-developed. For example, a review of the evidence-base for MBT identified 23 studies published between 1999 and 2018, of which five evaluated MBT with adolescents, and three evaluated interventions with children aged under five (Malda-Castillo et al., Citation2018). Only one study included in the review – a single-case report of MBT with a 7-year-old child – reported on the evaluation of a mentalization-based intervention related to middle childhood (Ramires et al., Citation2012). Likewise, another review of interventions that focused on improving parental reflective functioning identified six studies – all with parents of children under 5 years (Camoirano, Citation2017).

Given this apparent gap in the literature, the aims of the current study were to identify:

What mentalization-based interventions have been developed where the primary target is children aged 6–12, and/or their parents or carer?

Where such interventions have been formally evaluated, using at least one child- or carer-related health outcome, what is the evidence for the effectiveness of these treatments?

What is the study quality (risk of bias) for those interventions where systematic evaluation has been reported?

Given that mentalization-based interventions for children in this age group is a relatively new field, this study did not limit itself to examining the evidence-base for such approaches but aimed to more broadly identify publications that described such interventions, whether or not systematic evaluation of the approach was included.

Methods

This systematic review protocol was registered with the PROSPERO systematic review database (2020 – CRD42020224918) and carried out in line with PRISMA guidance (see Appendix 1 for PRISMA Checklist). The database search for this review was conducted using the Population Intervention Comparison Outcome Model (PICO: Schardt et al., Citation2007) for systematic reviews of health-related research. The target population for this search was children aged 6–12, but for the initial search no limit was placed on age, to maximize the chance of identifying relevant studies. The interventions searched for were those based on mentalization-based treatment (MBT) or interventions based on other closely related theoretical constructs, such as promoting reflective-functioning or maternal mind-mindedness. No limits were placed on whether outcome data were included in the study. Based on these principles, the search strategy used the following Boolean operators:

((child* OR famil* OR parent* OR mother* OR father* OR carer* OR caregiver*) AND (mentaliz* OR mentalis* OR MBT* OR “reflective function*” OR mind-minded* OR “theory of mind”) AND (therap* OR intervention* OR treatment*))

Five databases were searched: CINAHL, EMBASE, PsychInfo, Scopus and Web of Science. The range of databases was informed by previous reviews of MBT interventions (Malda-Castillo et al., Citation2018) and designed to include gray literature where possible to ensure breadth of findings. The specified terms were searched for in titles, abstracts and keywords of database items published between 1999 and 10th December 2020. In addition, a small number of papers, book chapters, and other items were retrieved through hand-searching.

The inclusion criteria for items were a) English version of text available; b) description of intervention explicitly states that the approach was informed by principles of mentalization-based treatment and/or on promoting mind-mindedness); c) primary target of intervention was children aged between 6 and 12. Where the intervention also targeted younger children or adolescents, the authors considered whether children in middle childhood were the primary target of the intervention, i.e. if the majority of children in the study fell within the 6–12 age group, or if the intervention was described as focused on “pre-adolescents”, those in “middle childhood” or equivalent category. No restrictions were placed on gender or ethnicity or on the child’s presenting condition. As this is a relatively new field, no restriction was placed on types of studies, and the review includes those publications that describe a model of MBT intervention for this population, whether or not any evaluation outcome data was included. Where review of the paper left it unclear if the intervention should be described as a “mentalization-based intervention”, first authors were contacted to seek their views. While inclusion criteria remained relatively broad, the following items were excluded: a) theoretical, measurement or review papers; b) interventions not centrally informed by mentalization theory; and c) items where there was insufficient text to perform data extraction, e.g., conference abstracts.

Once papers were identified, data were extracted from all studies that met inclusion criteria and recorded on an Excel spreadsheet. Data extraction included: Authors; date of publication; country; target group (e.g., presenting problem, or “all children in primary school”, etc.); age-range of children targeted; intervention format; whether evaluation data were reported (yes/no). For studies where evaluation data is reported, additional data extraction included: evaluation design; sample size; outcome measures used; findings. Data extraction was carried out by members of the study team. Where there was uncertainty about how the data should be extracted or reported, review and discussion between the three members of the study team led to a consensus decision. The quality of the studies was assessed using the NIH’s Quality Assessment Tools, available from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Two different tools were applied separately for controlled and uncontrolled studies. Independent ratings were carried out by two of the authors, and differences in ratings of overall quality were resolved through discussion.

Given the very broad range of studies that were identified, it was not possible to conduct any kind of meta-analysis. Data synthesis is therefore reported in a narrative format, organized with regard to target group (to identify which groups/types of children aged 6–12 MBT has been targeted at); intervention format (to identify what formats of intervention have been developed, e.g., individual or group-based); and c) outcomes (which interventions have been systematically evaluated, and a narrative review of that evaluation data, including risk of bias, etc.).

Results

Results of search

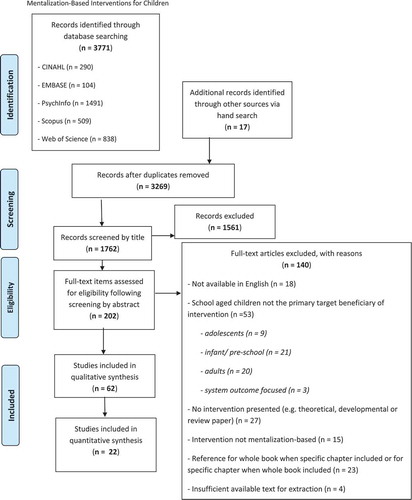

A total of 3771 items were identified through searching the specified databases, and additional 17 items were added through hand searching. A PRISMA flow chart showing the results of the search procedure is presented in .

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart template adapted from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097

All identified items were imported into MendeleyTM where duplicates were removed using Mendeley’s automatic duplicate removal functionality, leaving 3269 unique items. These records were screened manually by title leading to the removal of further duplicate items not identified by Mendeley’s automatic function and items clearly unrelated to the review’s target topic. The remaining 1763 items were then screened by abstract, leading to the removal of 1561 items.

The remaining 202 items were screened by full-text. These items were read in full and assessed against the inclusion criteria. Any uncertainty in the assessment of items for inclusion was resolved through a consensus method between the three authors, leading to the exclusion of further 140 items (see for exclusion reasons). For example, Nurturing Attachments (Golding, Citation2007), which has incorporated aspects of mentalization theory into its approach and has demonstrated an impact on carer reflective functioning (Staines et al., Citation2019), was not included, because the intervention was developed independently from MBT, and the intervention approach does not draw primarily on the principles and techniques of MBT. Once agreement on which studies should be included, this led to final 62 items identified for narrative synthesis with a subset of 22 with outcome data suitable for quantitative synthesis.

Data synthesis

The 62 identified items were first grouped by an intervention model, as shown in (see supplementary material), leading to the identification of 29 unique mentalization-informed interventions with those in middle childhood as their target beneficiaries. The following information for each full-text item was extracted: country, target group, format of the intervention and information regarding any evaluation, where applicable. Given the variation between items, thematic synthesis methods were used to review this range of work, examining items by target group focus, intervention format, and outcomes.

Table 1. Search results grouped by intervention model description

Target group focus

There was considerable variability in how the target group was identified, both in terms of age and in terms of presenting problems. With regard to age-groups, some models were quite specific, e.g., “8–11-year olds”, whereas some described the intervention as targeted at “children and adolescents”, with the subsequent text making clear that children aged 6–12 were a primary target group.

With regard to presenting problems, very few interventions were identified as targeting specific diagnostic groups – the exceptions were interventions that targeted children with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD; Sossin, Citation2015), eating disorders (Kelton-Locke, Citation2016), or ADHD (Conway et al., Citation2019) Some interventions were described as universal, for example, appropriate for all school-age children (e.g., Valle et al., Citation2016), but most were targeted. Of these targeted interventions, most identified their target group based on either current presentation, shared experience or family and/or systemic factors.

Where the target group were identified by current presentation, this was mostly broad categories such as “children with severe emotional and behavioural difficulties” (Perepletchikova & Goodman, Citation2014). Target populations defined by shared experiences included interventions for children who had experienced maltreatment and/or abuse (e.g., Ramires et al., Citation2012), or children who had experience of trauma (Oestergaad Hagelquist, Citation2018). Where family or systemic factors defined the target group, this included interventions for children living in foster care (e.g., Kelly & Salmon, Citation2014), children living in high poverty areas (e.g., N. Eppler-Wolff et al., Citation2019) or those affected by high levels of parental conflict (Hertzmann et al., Citation2016).

Intervention formats

The systematic review identified a wide range of formats for mentalization-based interventions for those in middle childhood. These intervention formats fell into four broad categories: individual, family, parent or carer-focused and whole system approaches, though there are several models which demonstrate overlap between these.

Interventions that described models of individual therapy with the child were the most common format. Almost all papers describing this approach referred back to the key contribution of Verheugt-Pleiter et al. (Citation2008), who were the first to offer a systematic account of MBT with children in this age group. This book sets out an approach to open-ended, long-term psychotherapy which integrates mentalization-based principles with classical psychoanalytic ideas, especially the Anna Freudian tradition of “developmental therapy” (Hurry, Citation1998).

Building on this work, others have elaborated on the nature of open-ended MBT with children (e.g.V. Domon-Archambault et al., Citation2020), and described adaptations of individual MBT for children aged 6–12 with specific presentations, such as children with developmental delays or behavior problems (Halfon & Bulut, Citation2017; Zevalkink et al., Citation2012). Others have systematically tried to identify key elements of the therapeutic process in MBT with clients or patients in middle childhood, in order to clarify similarities or differences with other therapeutic approaches (Hoffman, Citation2015; Munoz Specht et al., Citation2016). More recently, Midgley, Ensink et al. (Citation2017) have set out a time-limited model of MBT for children aged 5–12, which describes a more structured, focused model of MBT for this age group. This model has also been adapted for online or remote therapy (Bate & Malberg, Citation2020). As with the long-term model of MBT described by Verheught-Pleiter et al., parallel work with parents is a key element of time-limited MBT-C, with a number of authors describing the particular aims and techniques necessary for work with parents (e.g., Konijn et al., Citation2020; Leyton et al., Citation2019; Malberg, Citation2015; Slade, Citation2008).

Alongside these models of individual child therapy, the review also identified a number of papers outlining a family-based model of MBT for children. In the earliest paper (Fearon et al., Citation2006) this approach was described as Short-Term Mentalization and Relational Therapy (SMART); but the approach was later renamed Mentalization-Based Treatment for Families (MBT-F; Keaveny et al., Citation2012). Some authors emphasize that this is not a new “brand” of therapy, but rather a set of ideas and perspectives that can be brought to those working systemically with families (Asen & Fonagy, Citation2012a; Asen & Midgley, Citation2019). Most of the family-based models of MBT are transdiagnostic, but some authors describe how the approach can be used with specific categories of children, such as those with eating disorders (Kelton-Locke, Citation2016) or those referred to post-adoption support services (Downes et al., Citation2019; Midgley et al., Citation2018; Muller et al., Citation2012)

The third format identified in the systematic review was mentalization-based parent trainings. In previous reviews (e.g., Malda-Castillo et al., Citation2018) such interventions have only been described in work with parents of under-fives, but this review identified a number of approaches to mentalization-based parent-training with children. As with interventions for children under five, these approaches largely build on the work of Slade (Citation2005) on the concept of parental reflective functioning (PRF) and set out models of parent training which have an explicit focus on promoting this capacity. Recent developments, such as the Reflective Fostering Programme (Midgley, Cirasola et al., Citation2019; Redfern et al., Citation2018) have drawn on Cooper and Redfern’s model of “reflective parenting” (Cooper & Redfern, Citation2016; see also Etezady & Davis, Citation2012)

The final format identified in the systematic review was whole system interventions. These are mentalization-based interventions which explicitly work at multiple levels, aiming to promote mentalizing capacity across the whole system, not just in children and their parents or carers. These approaches show some similarity to Adolescent Mentalization-Based Integrative Treatment (AMBIT; Fuggle et al., Citation2015) which has been developed primarily in the context of work with adolescents; but for interventions with those in middle childhood the systems are those in which younger children operate, including schools and residential care homes (e.g. N. Eppler-Wolff et al., Citation2019; Lundgaard, Citation2018).

Outcomes

Of the 62 items identified by the review, only 20 (32%) reported original outcome data. These are summarized in (see supplementary material).

Table 2. Summary of reported outcomes

Not only were there relatively few approaches that were evaluated, but most of the studies were limited in terms of size and study design. Of the eight controlled studies, only one was a full-scale randomized controlled trial (Fonagy et al., Citation2009), whilst two were pilot or feasibility studies (Hertzmann et al., Citation2016; Midgley, Besser et al., Citation2017) and five had a quasi-experimental design. Although the two pilot/feasibility trials demonstrated that full-scale trials are feasible and worthwhile, these studies in themselves were not powered to provide evidence for the interventions. Of the non-controlled studies, most (n = 7) were simple pre-post intervention cohort studies, without a comparison group. One paper reported results of a small qualitative evaluation (Ingley-Cook & Dobel-Ober, Citation2013), one was a post-intervention survey of 10 parents (Downes et al., Citation2019), and one was a single-case study (Ramires et al., Citation2012).

Overall, the quality of the design of studies was low. Almost half of the studies were rated as “Poor” quality. Of the eight controlled studies, only two were rated as “good”. One was a cluster RCT of the Peaceful Schools Project and provided high-quality evidence of outcomes (Fonagy et al., Citation2009); the other was a feasibility RCT (Midgley, Cirasola et al., Citation2019) of family based MBT for children in foster care, which was well-designed, but as a feasibility study did not aim to report outcomes at this stage. Four out of the nine pre-post evaluations were rated as “good”, but the lack of control group means that even these studies provide limited evidence for the intervention outcomes. The most common problems identified through the quality assessments were lack of blinding and allocation concealment in the controlled studies, poor reporting of sources of selection and attrition bias, and, most notably, insufficiently powered studies. Only five of the studies had a sample size of more than 50.

Across the 20 evaluation studies, a wide range of outcomes were assessed. The results for each study are presented in detail in (supplementary material). A noteworthy finding from this review was that children’s mentalizing capacity was hardly ever assessed as an outcome. Two studies of the Peaceful Schools project (Fonagy et al., Citation2009; Twemlow et al., Citation2011) included children’s self-reported experiences of and beliefs about aggression and victimization using the Peer Experiences Questionnaire (Vernberg et al., Citation1999). This measure may be taken as a proxy measure of their mentalizing capacity. Only one study explicitly attempted to measure the impact of the intervention on children’s mentalizing capacity (Valle et al., Citation2016). This study assessed this outcome using multiple measures (false belief understanding, Strange Stories, Reading the mind in the Eyes, Mentalizing Task). The results were mixed, showing positive intervention effects on only a few of these measures.

All studies apart from one assessed outcomes for children in one or more domains. Most often, the children’s overall psychological, social and behavioral wellbeing was assessed with broad measures such as the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; R. Goodman, Citation1997), Child Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Shaffer et al., Citation1983), or the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, Citation1999). Almost all studies that assessed children’s general wellbeing found at least some positive changes over the intervention period.

It should be noted that the outcomes relating to child well-being were almost always carer-, clinician- or teacher-report. Only four of the 20 studies collected any data directly from the children (Åkerman et al., Citation2020; Ingley-Cook & Dobel-Ober, Citation2013; Midgley et al., Citation2018; Midgley, Besser et al., Citation2017). In these studies, child-reported outcomes showed more robust intervention effects than carer-report.

Although the common aim across all studies was to support children’s wellbeing, some targeted this indirectly through supporting parents, carers, teachers or residential care workers. For these approaches, outcomes for the caregivers themselves, alongside carer-reported outcomes for the children, were often assessed. In contrast to the paucity of research directly assessing child mentalizing, eight studies assessed caregivers’ mentalizing capacity. The measures used included the Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (PRFQ; Luyten et al., Citation2017), Mind-Mindedness (Meins et al., Citation2001) and the Reflective Functioning Scale (Fonagy et al., Citation1998) applied to either the Parent Development Interview (PDI-RF; Slade et al., Citation2004) or the Five-Minute Speech Sample-RF (FMSS-RF; Adkins et al., Citation2018). Only two studies showed clear evidence of improved caregiver mentalizing from pre- to post-intervention (Adkins et al., Citation2018; Enav et al., Citation2019) with the other studies finding no strong evidence for intervention effects in this domain.

Two further outcomes relating to caregivers were measured in several studies. Parenting stress, most often measured by the Parenting Stress Index (PSI; Abidin, Citation1990), improved in three of the five studies in which it was measured (Adkins et al., Citation2018; Midgley, Cirasola et al., Citation2019; Zeegers et al., Citation2019). Caregiver self-efficacy improved in two of the three studies in which it was measured (Enav et al., Citation2019; Midgley et al., Citation2018).

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to examine the range of mentalization-based interventions which have been developed for children in middle childhood, by conducting a systematic review of interventions where the primary target was children aged 6–12, and/or their parents or carers. The review aimed to provide a thematic synthesis of the studies identified, including an assessment of those studies where no empirical evaluation was reported.

Despite the absence of references to interventions for middle childhood in previous reviews of MBT (Camoirano, Citation2017; Malda-Castillo et al., Citation2018), the findings of this systematic review indicate that a wide range of mentalization-based interventions have been developed for this age group. Whilst a small number of interventions are targeted at children with specific diagnoses, such as eating disorders, ADHD or ASD, the majority focus on broader populations, often defined by their shared context (e.g., children who have experienced maltreatment), or else were trans-diagnostic in their focus (e.g., children with externalizing problems). This is in contrast to most of the studies reported in systematic reviews of MBT with adults or adolescents, which have primarily focused on diagnostic groups, such as adults with Borderline Personality Disorder, Eating Disorders, Depression or Psychosis (see Malda-Castillo et al., Citation2018). It may be that psychiatric diagnostic categories are less clinically meaningful for those in middle childhood compared to adolescents and adults; this would fit with the recent encouragement to move away from a focus on “protocols for syndromes”, based on a recognition that interventions might do better to focus on examining core biopsychosocial processes, including mentalizing capacity, that cut across diagnostic categories (Hofmann & Hayes, Citation2019).

As with target groups, there was also a significant variation in the format of the interventions identified in this review, ranging from individual therapy formats to system-level interventions. Several interventions aimed to improve the wellbeing of children by working only with their parents, carers or other adults involved with their care, such as teachers or residential social workers. This focus on systemic interventions fits with recent interest in the idea that interventions need to ensure that children have appropriate “learning environments” beyond the therapy setting, which can support shifts in their capacity for social learning (Fonagy & Allison, Citation2014). However, such interventions are also complex to manualize and systematically evaluate.

One of the striking findings from the systematic review was that a number of mentalization-based interventions for children aged 6–12 have been developed in the context of fostering and adoption. This may partly be explained by the fact that the developmental research has demonstrated a clear link between early trauma and mentalizing difficulties (e.g., Allen et al., Citation2008), as well as the fact that the field of fostering and adoption often works with an attachment framework (Taylor, Citation2012). There are high levels of attachment difficulties among children who have experienced early maltreatment, who make up the largest proportion of children who are fostered or adopted (e.g., Oswald et al., Citation2010). Some of the approaches identified in the review for promoting the well-being of fostered and adopted children took a whole system approach. For example, Taylor’s (Citation2012) “Mentalizating, Attachment and Trauma-informed Care” (MAT) aims to work with the social network of relationships around children in care, with a particular focus on those with disorganized attachments. The approach includes direct therapeutic work with children, but also focuses on the caregivers’ experiences of caring for traumatized children and how this may compromise their capacity to mentalize. Similarly, the Security, Trauma-focus, Obtaining-Skills, Resource-focus and Mentalization (STORM) model draws on elements of trauma therapy and MBT, and can be used for direct work with children, as well as families, professionals and the broader network and system (Oestergaad Hagelquist, Citation2018). Both MAT and the STORM approach focus on the importance of supporting the interpersonal bonds and attachment relationships that children in care already have, whether with foster carers, residential care workers or social workers; however, to date, no systematic evaluation of these interventions has been carried out.

Whilst the work of Hagelquist and Taylor both describe whole-system approaches for children in care, others have developed more structured programs to support childcare professionals and foster or adoptive parents. Vincent Domon-Archambault et al. (Citation2019) describe a Training Programme for Residential Care Workers of children aged 6–12; whilst Jacobsen et al. (Jacobsen et al., Citation2015) describe a short educational program and model of ongoing mentalization-based supervision for foster carers and staff. There are also mentalization-based training programs for foster and adoptive parents. “Family Minds” is a brief psychoeducational program developed in the US, which has demonstrated an impact on parental stress and PRF in an initial evaluation study (Adkins et al., Citation2018); whilst the “Reflective Fostering Programme” in the UK has also shown promising results in a preliminary evaluation study (Midgley, Cirasola et al., Citation2019). Encouragingly, both these models are currently being evaluated in randomized controlled trials, with the results likely to establish more clearly the impact of these interventions both on carers and on children in care.

The review also identified several examples of direct therapeutic work with fostered and adopted children, either in an individual or a family-based format. For example, the Herts and Minds study (Midgley, Besser et al., Citation2017, 2019) demonstrates the feasibility of conducting a randomized controlled trial for a family-based model of MBT, when working with children in care and their foster parents; whilst Midgley et al. (Citation2018) describe a preliminary evaluation of a family based MBT for use in post-adoption support services. Alongside these, Ingley-Cook and Dobel-Ober (Citation2013) set out a model of MBT groups for children in care, and both Rowny (Citation2018) and Ramires et al. (Citation2012) describe models of individual MBT with children in care, often including parallel work with foster carers or residential care workers. Although none of these models of intervention have been evaluated in a full-scale clinical trial, it is striking that many of the interventions for children in care have included some form of systematic evaluation, and at least two are currently being tested in randomized clinical trials.

Although there is some accruing evidence for mentalization-based interventions to support adopted and fostered children, this was not the case for the majority of other approaches identified in this review. In fact, only a third of the papers reported any kind of outcome evaluation, and more than half of those that did were extremely limited in the quality of evidence they provided. The evidence for mentalization-informed interventions for those in middle childhood and their families cannot, therefore, be deduced with any degree of certainty. The reason for this lack of evaluation studies is probably multi-determined. Most funding for evaluation is still based on testing manualized treatments for specific diagnostic groups, and this may be one reason why there is comparatively little research evaluating the interventions set out in this review, given that many were complex, multi-component interventions that were not targeted at specific diagnostic groups of children.

Based on the small number of evaluation studies that have been conducted, the evidence for mentalization-based intervention effectiveness for children aged 6–12 suggests possible benefits in terms of parent/carer outcomes (PRF, self-efficacy, and stress) as well as children’s psychosocial functioning. However, the main finding from the review is that there is currently little evidence for these interventions and good quality-controlled studies that minimize bias are sorely needed.

The synthesis of outcome data from this review revealed a further research gap: the lack of direct measurement of outcomes for children. All studies that assessed child psychosocial functioning used parent/carer-, teacher-, or clinician-reported instruments. This may be the result of some studies being of interventions targeting carers rather than children directly. However, all interventions aim to ultimately improve outcomes for children and the child’s own subjective sense of well-being should be given precedence. One study (Midgley, Besser et al., 2019) did collect child self-reported SDQ data from the older children (11–16 years old) in the sample and found positive intervention effects. This was in contrast to non-significant intervention effects on the carer-reported SDQ for the whole sample. This finding of greater improvements on child-reported measures was supported by the study by Åkerman and colleagues (Citation2020). They found significant improvements in child-reported wellbeing but not on foster carer-reported or teacher-reported outcomes for the same group of children. The authors emphasize the importance of assessing children’s own subjective reports of their wellbeing as a key outcome for such interventions.

A related issue was the lack of measurement of children’s mentalizing as an outcome. In fact, only one study used a measure explicitly assessing mentalizing in children (Valle et al., Citation2016), but with mixed findings. Perhaps this reflects a lack of longitudinal developmental research into how mentalizing develops across middle childhood. Without well-validated and common assessment tools, it is challenging to evaluate and replicate interventions. Thus, a key priority for research in this field is to develop, refine and validate measures for assessing mentalizing capacity across middle childhood, as only then will evaluations be able to assess intervention effects in this domain of functioning.

Limitations of the review

There are several methodological limitations of this review. As with many other reviews, it is difficult for online searches to capture the full breadth of existing literature as they frequently do not identify much of the gray literature and are subject to issues of publication bias. Our review only included texts available in English, which led to the exclusion of several papers written in other languages. The nature of this study’s research question led to some imprecision in defining search terms and ambiguity regarding certain inclusion and exclusion criteria. This was particularly the case for intervention type, as it was not always possible to distinguish clearly between mentalization-based interventions and other interventions that included some focus on improving reflective functioning but were not explicitly mentalization-based. Similarly, search terms relating the target population of interest, children aged 6–12, were challenging to define as, unlike infancy or adolescence, there are fewer widely used descriptors for children in this age bracket, who are sometimes referred to as “latency age” children, or “pre-adolescents”. Some literature identified in the search described interventions that had been adapted for children of a wide range of ages. While the authors endeavored to select only papers outlining interventions primarily targeting children aged 6–12 in some cases, this was difficult to identify and led to the exclusion of some interventions that were appropriate for the lower or upper ages of this group, but primarily targeted under 5 s or adolescents.

Conclusions

This systematic review identified a wider range of mentalization-based interventions for children aged 6–12 than had been indicated by previous reviews. These interventions targeted a wide range of children, and were very diverse in format, with some focused more on whole systems, and others describing models of direct therapy for individuals, groups or families. It was striking that several interventions targeted children in schools, as well as children in the social care system. Only a third of the papers identified in the review reported outcome data, and in most cases these were small-scale, pre-post evaluations. Although there were a small number of well-designed studies, the evidence base for mentalization-based interventions for those in middle childhood is still undeveloped, especially when compared to the evidence-base for mentalization-based interventions for infants or adults.

Acknowledgments

All authors were involved in the development of a search strategy, identification of research item, screening of items, synthesis and quality evaluation of literature and writing of this paper. [Name 1] led on the conceptual design and writing of this paper, [name 2] led on literature searching, and [name 3] led on the synthesis and quality evaluation of outcome studies.

Disclosure statement

The first author of this paper was an author on some of the studies reviewed in this paper. However, he has no financial interests in relation to these interventions.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nick Midgley

Nick Midgley is Professor of Psychological Therapies with Children and Young People at UCL and co-director of the Child Attachment and Psychological Therapies Research Unit (ChAPTRe) at the Anna Freud Centre, London. Among other works, he co-edited Minding the Child: Mentalization-Based Interventions with Children, Young People and Families (Routledge, 2012), and was one of the authors of Mentalization-Based Treatment for Children: A Time-Limited Approach (APA, 2017).

Eva A. Sprecher

Eva A. Sprecher is a PhD candidate at UCL studying relationships between foster carer and the young people in their care. She is also a Research Officer at the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families on the Reflective Fostering Programme randomised controlled trial.

Michelle Sleed

Michelle Sleed is a Senior Research Fellow in ChAPTRe at the Anna Freud Centre/ UCL. She carries out research into the effectiveness of psychological therapies for families and has a particular interest in mentalization.

References

- Abidin, R. R. (1990). Parenting Stress Index (PSI). Charlottesville, VA: Pediatric Psychology Press.

- Achenbach, T. M. (1999). The child behaviour checklist and related instruments. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (pp. 429–466). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Adkins, T., Luyten, P., & Fonagy, P. (2018). Development and preliminary evaluation of family minds: A mentalization-based psychoeducation program for foster parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(8), 2519–2532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1080-x

- Åkerman, A.-K. E., Holmqvist, R., Frostell, A., & Falkenström, F. (2020). Effects of mentalization-based interventions on mental health of youths in foster care. Child Care in Practice, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2020.1812531

- Allen, J. G., Fonagy, P., & Bateman, A. W. (2008). Mentalizing in Clinical Practice. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

- Asen, E. (2013). Migrating between self and others: Mentalisation-based therapy with families. In McGinley, E. & Varchevker, A. (Eds.), Enduring migration through the life cycle (pp. 133–148). Karnac Books. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc10&NEWS=N&AN=2013-10844-007

- Asen, E., & Midgley, N. (2019). Mentalization-based approaches to working with families. In A. W. Bateman & P. Fonagy (Eds.), Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice (2nd ed., pp. 136–149). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

- Asen, E., & Fonagy, P. (2012a). Mentalization-based Therapeutic Interventions for Families. Journal of Family Therapy, 34(4), 347–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2011.00552.x

- Asen, E., & Fonagy, P. (2012b). Mentalization-based family therapy. In Bateman, A. W. & Fonagy, P. (Eds.), Handbook of Mentalizing in Mental Health Practice (pp. 107–128). American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc9&NEWS=N&AN=2011-19854-005

- Asen, E., & Fonagy, P. (2017). Mentalizing Family Violence Part 1: Conceptual Framework. Family Process, 56(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12261

- Bammens, A. S., Adkins, T., & Badger, J. (2015). Psycho-educational intervention increases reflective functioning in foster and adoptive parents. Adoption & Fostering, 39(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308575914565069

- Bate, J., & Malberg, N. (2020). Containing the anxieties of children, parents and families from a distance during the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 50(4), 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-020-09466-4

- Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2016). Mentalization-Based Treatment for Personality Disorders: A Practical Guide. Oxford University Press.

- Berube-Beaulieu, E., Ensink, K., & Normandin, L. (2016). Mothers’ reflective functioning and infant attachment: A prospective study of the links with maternal sensitivity and maternal mind-mindedness. Revue québécoise de psychologie, 37(3), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.7202/1040158ar

- Borelli, J. L., St. John, H. K., Cho, E., & Suchman, N. E. (2016). Reflective functioning in parents of school-aged children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000141

- Borelli, J. L., West, J. L., Decoste, C., & Suchman, N. E. (2012). Emotionally avoidant language in the parenting interviews of substance‐dependent mothers: Associations with reflective functioning, recent substance use, and parenting behavior. Infant Mental Health Journal, 33(5), 506–519. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21340

- Camoirano, A. (2017). Mentalizing makes parenting work: A review about parental reflective functioning and clinical interventions to improve it. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(14), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00014

- Cincotta, N. (2008). The journey of middle childhood: Who are ‘latency’-age children? In A. S. G. (Ed.), Developmental theories through the life cycle (pp. 97–132). Colombia University Press.

- Clark, J. (2014). Integrating ABA with developmental models: MERIT. In K. Siri, T. Lyons, & T. Arranga (Eds.), Cutting edge therapies for autism (4th ed., pp. 361–368). Skyhorse Publishing.

- Conway, F., Lyon, S., Silber, M., & Donath, S. (2019). Cultivating compassion ADHD project: A mentalization informed psychodynamic psychotherapy approach. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 18(3), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2019.1654271

- Cooper, A., & Redfern, S. (2016). Reflective parenting: A guide to understanding what’s going on in your child’s mind. Routledge.

- Domon-Archambault, V., Terradas, M. M., Drieu, D., De Fleurian, A., Achim, J., Poulain, S., & Jerrar-Oulidi, J. (2019). Mentalization-based training program for child care workers in residential settings. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 13, 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-019-00269-x

- Domon-Archambault, V., Terradas, M. M., Drieu, D., & Mikic, N. (2020). Mentalization-based interventions in child psychiatry and youth protection services II: A model founded on the child’s prementalizing mode of psychic functioning. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 19(3), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2020.1799476

- Downes, C., Kieran, S., & Tiernan, B. (2019). “Now I Know I’m Not the Only one”: A group therapy approach for adoptive parents. Child Care in Practice, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2019.1664992

- Enav, Y., Erhard-Weiss, D., Kopelman, M., Samson, A. C., Mehta, S., Gross, J. J., & Hardan, A. Y. (2019). A non randomized mentalization intervention for parents of children with autism. Autism Research, 12(7), 1077–1086. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2108

- Ensink, K., Berthelot, N., Bernazzani, O., Normandin, L., & Fonagy, P. (2014). Another step closer to measuring the ghosts in the nursery: Preliminary validation of the trauma reflective functioning scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1471. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01471

- Ensink, K., & Mayes, L. C. (2010). The development of mentalisation in children from a theory of mind perspective. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 30(4), 301–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690903206504

- Eppler-Wolff, N., Albertson, J., Martin, S., & Infante, L. (2020). In the nest: Case studies from the school-based mental health collaboration. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 19(4), 371–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2020.1845075

- Eppler-Wolff, N., Martin, A., & Homayoonfar, S. (2019). The School-Based Mental Health Collaboration (SBMHC): A multi-level university-school partnership. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 18(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2019.1573095

- Etezady, M., & Davis, M. (2012). Clinical perspectives on reflective parenting. Jason Aronson.

- Fearon, P., Target, M., Sargent, J., Williams, L. L., McGregor, J., Bleiberg, E., & Fonagy, P. (2006). Short-term mentalization and relational therapy (SMART): An integrative family therapy for children and adolescents. In J. G. Allen & P. Fonagy (Eds.), The handbook of mentalization-based treatment (pp. 201–222). John Wiley & Sons Inc. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1002/9780470712986.ch10

- Fonagy, P., & Allison, E. (2014). The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036505

- Fonagy, P., Target, M., Steele, H., & Steele, M. (1998). Reflective functioning manual. Version 5.0 for application to adult attachment interviews. (Unpublished manual).

- Fonagy, P., Twemlow, S. W., Vernberg, E. M., Nelson, J. M., Dill, E. J., Little, T. D., & Sargent, J. A. (2009). A cluster randomized controlled trial of child-focused psychiatric consultation and a school systems-focused intervention to reduce aggression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(5), 607–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02025.x

- Fuggle, P., Bevington, D., Cracknell, L., Hanley, J., Hare, S., Lincoln, J., Richardson, G., Stevens, N., Tovey, H., & Zlotowitz, S. (2015). The Adolescent Mentalization-based Integrative Treatment (AMBIT) approach to outcome evaluation and manualization: Adopting a learning organization approach. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 20(3), 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104514521640

- Golding, K. (2007). Nurturing attachments: Supporting children who are fostered or adopted. Jessica Kingsley.

- Goodman, G., Midgley, N., & Schneider, C. (2016). Expert clinicians’ prototypes of an ideal child treatment in psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral therapy: Is mentalization seen as a common process factor? Psychotherapy Research, 26(5), 590–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1049672

- Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 38(5), 581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

- Halfon, S., & Bulut, P. (2017). Mentalization and the growth of symbolic play and affect regulation in psychodynamic therapy for children with behavioral problems. Psychotherapy Research, 29(5), 666–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1393577

- Hertzmann, L., Abse, S., Target, M., Glausius, K., Nyberg, V., & Lassri, D. (2017). Mentalisation-based therapy for parental conflict – parenting together; an intervention for parents in entrenched post-separation disputes. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 31(2), 195–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2017.1320685

- Hertzmann, L., Target, M., Hewison, D., Casey, P., Fearon, P., & Lassri, D. (2016). Mentalization-based therapy for parents in entrenched conflict: A random allocation feasibility study. Psychotherapy, 53(4, SI), 388–401. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000092

- Hoffman, L. (2015). Mentalization, emotion regulation, countertransference. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 14(3), 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2015.1064258

- Hofmann, S. G., & Hayes, S. (2019). The future of intervention science: Process-based therapy. Clinical Psychology Science, 7(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618772296

- Hurry, A. (1998). Psychoanalysis and developmental therapy. Karnac Books.

- Ingley-Cook, G., & Dobel-Ober, D. (2013). Innovations in practice: Group work with children who are in care or who are adopted: Lessons learnt. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 18(4), 251–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00683.x

- Jacobsen, M. N., Ha, C., & Sharp, C. (2015). A mentalization-based treatment approach to caring for youth in foster care. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 14(4), 440–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2015.1093921

- Jaffrani, A. A., Sunley, T., & Midgley, N. (2020). The building of epistemic trust: An adoptive family’s experience of mentalization-based therapy. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 19(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2020.1768356

- Keaveny, E., Midgley, N., Asen, E., Bevington, D., Fearon, P., Fonagy, P., … Wood, S. (2012). Minding the family mind The development and initial evaluation of mentalization-based treatment for families. In N. Midgley & I. Vrouva (Eds.), Minding the child: Mentalization-based interventions with children, young people and their families (pp. 98–112). TAYLOR & FRANCIS LTD.

- Kelly, W., & Salmon, K. (2014). Helping foster parents understand the foster child’s perspective: A relational learning framework for foster care. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19(4), 535–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104514524067

- Kelton-Locke, S. (2016). Eating disorders, impaired mentalization, and attachment: implications for child and adolescent family treatment. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 15(4), 337–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2016.1257239

- Konijn, C., Colonnesi, C., Kroneman, L., Liefferink, N., Lindauer, R. J. L., & Stams, G.-J.-J. M. (2020). `Caring for children who have experienced trauma’ - an evaluation of a training for foster parents. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1756563

- Leyton, F., Olhaberry, M., Alvarado, R., Rojas, G., Dueñas, L. A., Downing, G., & Steele, H. (2019). Video feedback intervention to enhance parental reflective functioning in primary caregivers of inpatient psychiatric children: protocol for a randomized feasibility trial. Trials, 20(1), 268. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3310-y

- Lundgaard, P. B. (2018). Developing resilience in children and young people. Routledge.

- Lundgard Bak, P. (2012). Thoughts in Mind: Promoting mentalizing communities for children. In Midgley, N. & Vrouva, I. (eds.). Minding the Child: Mentalization-Based Interventions with Children, Young People and Families. Routledge.

- Luyten, P., Mayes, L. C., Nijssens, L., & Fonagy, P. (2017). The parental reflective functioning questionnaire: Development and preliminary validation. PLoS One, 12(5), 5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176218

- Malberg, N. T. (2012). Thinking and feeling in the context of chronic illness A mentalization-based group intervention with adolescents. In N. Midgley, & I. Vrouva, (Eds.), Minding the child: mentalization-based interventions with children, young people and their families (pp. 147–162). Taylor & Francis Ltd.

- Malberg, N. T. (2015). Activating mentalization in parents: An integrative framework. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 14(3), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2015.1068002

- Malda-Castillo, J., Browne, C., & Perez-Algorta, G. (2018). Mentalization-based treatment and its evidence-base status: A systematic literature review. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 92(4), 465–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12195

- Meins, E., Fernyhough, C., Fradley, E., & Tuckey, M. (2001). Rethinking maternal sensitivity: Mothers’ comments on infants’ mental processes predict security of attachment at 12 months. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(5), 637–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00759

- Mensah, E., & Andreadi, H.-G. (2016). Multi-family group therapy. In Clinical Practice at the Edge of Care: Developments in Working with At-Risk Children and Their Families (pp. 175–196). Springer International Publishing.

- Midgley, N., Muller, N., Malberg, N., Lindqvist, K., & Ensink, K. (2019). Specific applications: Children. In A. Bateman & P. Fonagy (Eds.), Handbook of mentalization in mental health practice (2nd ed., pp. 247–264). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

- Midgley, N., Alayza, A., Lawrence, H., & Bellew, R. (2018). Adopting minds a mentalization-based therapy for families in a post-adoption support service: Preliminary evaluation and service user experience. ADOPTION AND FOSTERING, 42(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308575917747816

- Midgley, N., Besser, S. J., Dye, H., Fearon, P., Gale, T., Jefferies-Sewell, K., Irvine, K., Robinson, J., Wyatt, S., Wellsted, D., & Wood, S. (2017). The herts and minds study: Evaluating the effectiveness of Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT) as an intervention for children in foster care with emotional and/or behavioural problems: A phase II, feasibility, randomised controlled trial. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 3(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-017-0127-x

- Midgley, N., Cirasola, A., Austerberry, C., Ranzato, E., West, G., Martin, P., Redfern, S., Cotmore, R., & Park, T. (2019). Supporting foster carers to meet the needs of looked after children: A feasibility and pilot evaluation of the Reflective Fostering Programme. Developmental Child Welfare, 1(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/2516103218817550

- Midgley, N., Ensink, K., Lindqvist, K., Malberg, N., & Muller, N. (2017). Mentalization-based treatment for children: A time-limited approach. American Psychological Association.

- Midgley, N., & Vrouva, I. (Eds.). (2012). Minding the child: Mentalization-based interventions with children, young people and their families. Routledge.

- Montgomery-Graham, S. (2016). DBT and schema therapy for borderline personality disorder: Mentalization as a common factor. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 46(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-015-9309-0

- Muller, N., Gerits, L., & Siecker, I. (2012). Mentalization-based therapies with adopted children and their families. In N. Midgley & I. Vrouva (Eds.), Minding the child: Mentalization-based interventions with children, young people and their families (pp. 113–130). Taylor & Francis.

- Munoz Specht, P., Ensink, K., Normandin, L., Midgley, N., Specht, P. M., Ensink, K., … Midgley, N. (2016). Mentalizing techniques used by psychodynamic therapists working with children and early adolescents. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 80(4), 281–315. https://doi.org/10.1521/bumc.2016.80.4.281

- Oestergaard Hagelquist, J. (2018). The mentalization guidebook. Routledge.

- Ordway, M. R., Sadler, L. S., Dixon, J., Close, N., Mayes, L., & Slade, A. (2014). Lasting effects of an interdisciplinary home visiting program on child behavior: Preliminary follow-up results of a randomized trial. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 29(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2013.04.006

- Oswald, S. H., Heil, K., & Goldbeck, L. (2010). History of maltreatment and mental health problems in foster children: A review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35(5), 462–472. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsp114

- Pally, R., & Robeck, P. (2012). CRP direct services and training programmes. In M. H. Etezady & M. Davis (Eds.), The vulnerable child book series. Clinical perspectives on reflective parenting: Keeping the child’s mind in mind (pp. 31–58). Jason Aronson.

- Perepletchikova, F., & Goodman, G. (2014). Two approaches to treating preadolescent children with severe emotional and behavioral problems: Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for children and mentalization-based child therapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 24(4), 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038134

- Ramires, V. R. R., Schwan, S., & Midgley, N. (2012). Mentalization-based therapy with maltreated children living in shelters in southern Brazil: A single case study. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 26(4), 308–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2012.730546

- Redfern, S., Wood, S., Lassri, D., Cirasola, A., West, G., Austerberry, C., Luyten, P., Fonagy, P., & Midgley, N. (2018). The Reflective Fostering Programme: background and development of a new approach. Adoption and Fostering, 42(3), 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308575918790434

- Rossouw, T. I., & Fonagy, P. (2012). Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(12), 1304–1313.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.018

- Rostad, W. L., & Whitaker, D. J. (2016). The association between reflective functioning and parent–child relationship quality. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(7), 2164–2177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0388-7

- Rowny, K. L. (2018). Developmentally-Anchored Considerations for Youth with a History of Foster Care: A Clinical Resource Guide Clarifying Key Elements of Mentalization and Mentalization-Based Treatment. (Doctoral dissertation, The Wright Institute). https://search.proquest.com/openview/b342ec2884e4f94ac90bdf292e3f1532/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Rutherford, H. J. V., Goldberg, B., Luyten, P., Bridgett, D. J., & Mayes, L. C. (2013). Parental reflective functioning is associated with tolerance of infant distress but not general distress: Evidence for a specific relationship using a simulated baby paradigm. Infant Behavior and Development, 36(4), 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.06.008

- Schardt, C., Adams, M. B., Owens, T., Keitz, S., & Fontelo, P. (2007). Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 7(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-7-16

- Shaffer, D., Gould, M. S., Brasic, J., Ambrosini, P., Bird, H., & Aluwahlia, S. (1983). A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Archives of General Psychiatry, 40(11), 1228–1231. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010

- Sharp, C., & Venta, A. (2012). Mentalizing problems in children and adolescents. In N. Midgley & I. Vrouva (Eds.), Minding the child: Mentalization-based interventions with children, young people and their families (pp. 35–53). Taylor & Francis.

- Slade, A. (2005). Parental Reflective Functioning: An Introduction. Attachment and Human Development, 7(3), 269–281

- Slade, A. (2008). Mentalization as a frame for working with parents in child psychotherapy. In E. L. Jurist, A. Slade, & S. Bergner (Eds.), Mind to Mind: Infant Research, Neuroscience, and Psychoanalysis (pp. 307–334). Other Press.

- Slade, A., Aber, L., Bresgi, I., Berge, B., & Kaplan, N. (2004). The Parent Development Interview, revised.

- Sossin, K. M. (2015). A movement-informed mentalization lens applied to psychodynamic psychotherapy of children and adolescents with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 14(3), 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2015.1066630

- Staines, J., Golding, K., & Selwyn, J. (2019). Nurturing attachments parenting program: The relationship between adopters’ parental reflective functioning and perception of their children’s difficulties. Developmental Child Welfare, 1(2), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/2516103219829861

- Stob, V., Slade, A., Brotnow, L., Adnopoz, J., & Woolston, J. (2019). The Family Cycle: An Activity to Enhance Parents’ Mentalization in Children’s Mental Health Treatment. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 18(2), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2019.1591887

- Suchman, N. E., Ordway, M. R., de las Heras, L., & McMahon, T. J. (2016). Mothering from the inside out: Results of a pilot study testing a mentalization-based therapy for mothers enrolled in mental health services. Attachment & Human Development, 18(6), 596–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2016.1226371

- Taubner, S., & Thorsten-Christian Gablonski, P. (2019). Conduct disorder. In A. W. Bateman & P. Fonagy (Eds.), Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice (2nd ed., pp. 301–322). American Psychoanalytic Association.

- Taylor, C. (2012). Empathic care for children with disorganised attachments:. A model for mentalizing, attachment and trauma-informed care (Jessica Ki). London.

- Terradas, M. M., Domon-Archambault, V., Senécal, I., Drieu, D., & Mikic, N. (2020). Mentalization-based interventions in child psychiatry and youth protection services I: Objectives, setting, general principles and strategies. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 19(3), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2020.1799311

- Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., & Sacco, F. C. (2005). A developmental approach to mentalizing communities: I. A model for social change. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 69(4), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1521/bumc.2005.69.4.265

- Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., & Sacco, F. C. (2009). A developmental approach to mentalizing communities: The Peaceful Schools experiment. A Mentalizalo Kozossegek Fejlodeslelektani Megkozelitese. A “Bekes Iskolak” Kiserlet., 18(4), 261–268. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc6&NEWS=N&AN=2009-13338-003

- Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., Sacco, F. C., Vernberg, E., & Malcom, J. M. (2011). Reducing violence and prejudice in a Jamaican all age school using attachment and mentalization theory. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 28(4), 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023610

- Valle, A., Massaro, D., Castelli, I., Sangiuliano Intra, F., Lombardi, E., Bracaglia, E., & Marchetti, A. (2016). Promoting mentalizing in pupils by acting on teachers: Preliminary Italian evidence of the “Thought in Mind” project. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01213

- Verheugt-Pleiter, A. J. E., Zevalkink, J., & Schmeets, M. G. (2008). Mentalizing in child therapy: Guidelines for clinical practitioners. London: Karnac Books. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc6&NEWS=N&AN=2008-01636-007

- Vernberg, E. M., Jacobs, A. K., & Hershberger, S. L. (1999). Peer victimization and attitudes about violence during early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 28(3), 386–395. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424jccp280311

- Vrouva, I., Target, M., & Ensink, K. (2012). Measuring mentalization in children and young people. In N. Midgley & J. Vrouva (Eds.), Minding the child: Mentalization-based interventions with children, young people and their families (pp. 54–76). Routledge.

- Zayde, A., Prout, T. A., Kilbride, A., & Kufferath-Lin, T. (2020). The Connecting and Reflecting Experience (CARE): Theoretical foundation and development of mentalizing-focused parenting groups. Attachment and Human Development, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2020.1729213

- Zeegers, M. A., Colonnesi, C., Noom, M. J., Polderman, N., & Stams, G. J. J. (2019). Remediating child attachment insecurity: Evaluating the basic trust intervention in adoptive families. Research on Social Work Practice, 30(7), 736–749. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1049731519863106

- Zeegers, M. A. J., Colonnesi, C., Stams, G.-J.-J. M., & Meins, E. (2017). Mind matters: A meta-analysis on parental mentalization and sensitivity as predictors of infant–parent attachment. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1245–1272. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000114

- Zevalkink, J., Verheugt-Pleiter, A., & Fonagy, P. (2012). Mentalization-informed child psychoanalytic psychotherapy. In A. W. Bateman & P. Fonagy (Eds.), Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice (p. 129–158). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc..