ABSTRACT

This article communicates a study on dance for people over 65 in Sweden. Earlier studies on dance for elderly people have primarily focused on treatment and wellbeing. The current study centers on the right to make oneself heard in and through contemporary dance as an artistic form of expression, regardless of age, gender, or geographical context. The specific aim of the study is to describe and analyze the experiences of women aged over 65 in a rural area, who participated in contemporary dance workshops as a form of arts learning. The workshops, which were observed and documented, constituted part of an EU-financed project, Age on stage. Participants also shared experiences through informal chats and e-mails. The material was analyzed in a narrative manner. The results show that the workshops created a safe space for dance as a dwelling place, where dance was discovered, and at the same time developed, collaboratively. The results also highlighted the importance of this type of artistic participation for elderly women in terms of developing an understanding of themselves and coping with life.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

I experience happiness, closeness, fun leadership, freedom, contact with myself, ease, love for myself and togetherness. (Participant, Workshop one)

I gained a sense of ease and happiness from the workshop– a sense that age doesn’t matter when it comes to what I feel and need, and that dance is a wonderful way of understanding myself and others. (Participant, Workshop two)

Policy issues in relation to elderly people and cultural activities have recently become a subject of considerable interest to researchers. It is clear that, despite strong recommendations in UNESCO’s lifelong learning agenda calling for social innovations that address the challenges of aging populations effectively, older adults and elderly people are still largely overlooked and marginalized in arts education worldwide (Laes Citation2015). Research focuses on issues such as the institutional and policy goals of lifelong learning within the arts (Schmidt and Colwell Citation2017), and lifelong and life- wide arts education as a creative social practice strives to improve methods of education for the elderly, as well as intergenerational learning, which in turn have the potential to extend the opportunities for adults to learn and participate, and therefore advance the general wellbeing of society (Laes Citation2018). The research also contributes a critical outlook on the changing nature of general aging discourses, as well as political justification and re-interpretation of lifelong learning policies. In addition, the scientific results may be of interest not only to arts educators, but to a variety of policy makers and educational leaders.

To be able to establish functional and sustainable arts practices directed at elderly people, it is relevant to think about and discuss how lifelong learning is understood in arts education, what the implications and consequences of UNESCO’s lifelong learning agenda are for arts education policy and practice, and what challenges and opportunities rapidly aging societies bring to arts education (Laes Citation2018). As learning about oneself and making oneself heard through artistic forms of expression have both essential and existential dimensions, arts learning among elderly involves internalizing dance technique and ways of handling the body, as well as managing and becoming aware of oneself, others, and living throughout life.

Hitherto, research focusing on dance with elderly people has been divided into two focus areas, namely health treatment and wellbeing (Ferm Almqvist and Andersson Citation2019; Lehikoinen Citation2019). In terms of health treatment, the research highlights both the benefits and effects of participating in dance activities (Alpert et al. Citation2009; Hackney and Earhart Citation2009; Ying Citation2010; Soriano and Batson Citation2011; Duncan and Earhart Citation2014; Fernández-Argüelles et al. Citation2015; Merom et al. Citation2016; Toygar Citation2018). Research has emphasized the positive effects on different aspects of the functioning and abilities of the body, such as balance and flexibility (Shigematsu et al. Citation2002; Kattenstroth et al. Citation2013; MacMillan Citation2016; Serra et al. Citation2016).

The second focus area concerns wellbeing in relation to participation in community dance (In-Sil et al. Citation2015; Fortin Citation2018), based on a belief that dance is for everyone, for various types of dancing bodies, and that everybody can dance (Green Citation2000; Nakajima Citation2011; Barr Citation2013). Lerman’s (Citation1976) initiatives and models for physical and creative modern dance activities with older persons constitute valuable pioneer work in this area. Social interactions including both participants and facilitators offer opportunities for everyone to express themselves, to connect to life experiences, and to find identity in relationship (Green Citation2000; Barr Citation2013; Hartogh Citation2016). Such experiences are found to contribute to social well-being among older adults (Camic, Tischler, and Pearman Citation2014; Phinney, Moody, and Small Citation2014; In-Sil et al. Citation2015; Pearce and Lillyman Citation2015; MacMillan Citation2016). That dance and music activities offer health and social benefits, and at the same time contribute to life-long learning, is shown by the results of Söderman and Westvall’s (Citation2017) study of cultural activities in a Finnish society in Sweden. This brings arts education and related learning to the forefront, with well-being and health in the background of the situation.

What is missing here though, according to Thornberg et al. (2012) is research that takes the participants’ own experiences into account. The aim of the EU-financed project Age on stage was to make visible and elaborate on the right for elderly amateur and professional dancers to continue to learn and make themselves heard in and through dance as an artistic form of expression (Ferm Almqvist and Andersson Citation2019, Citation2020). Expressing oneself artistically through dance has so far mostly been studied among older professional dancers (Berson Citation2010; Dickinson Citation2010). Hence, this article strives to complement existing research on dance as a form of artistic expression in elderly amateur dancers. The empirical case in this investigation involves two contemporary dance workshops conducted in the northern part of Sweden, which will be described further.

As noted above, the right to express oneself and take part in cultural activities throughout life is expressed in different legal texts and documents on human rights, such as Article 27 of UNESCO and the Declarations of Human Rights (Citation2019), which states that all human beings have the right to be engaged in cultural life and appreciate the arts. This is in line with the Swedish Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression. The law emphasizes that each and every citizen of Sweden has the assured right to express thoughts, opinions, and feelings, and to share information on any subject (The Swedish Parliament Citation2015). Freedom of expression, according to this basic law, aims to guarantee the free sharing of meaning, free and multi-faceted information and free artistic creation. The dance workshops could be viewed as a possibility for elderly people in Norrbotten to express thoughts and ideas through dance as a form of artistic creation. No similar activities had previously been offered to this age group in the area, although contemporary dance performances are rather common in Norrbotten.

Furthermore, cultural policy is defined by the Swedish government as promoting a living and independent cultural heritage. It states that this area covers the conditions for cultural practitioners and people’s access to culture in all its forms, as well as how cultural heritage is to be preserved, used, and developed (The Swedish Parliament Citation2019). The current Swedish cultural policy objectives were established in 2009 (Lindberg Citation2012) and aim to inspire and guide local government policy. According to the government, culture should be a dynamic, challenging, and independent force based on freedom of expression. Everyone is to have the opportunity to participate in cultural life. Creativity, diversity, and artistic quality are to be integral factors in the development of society.

To achieve the objectives, cultural policy involves promoting opportunities for everyone to experience culture, participate in educational programs and develop their creative abilities. This is intended to promote quality and artistic renewal; a dynamic cultural heritage that is preserved, used, and developed; accessibility; international and intercultural exchange; and cooperation in the cultural sphere. It also pays particular attention to the rights of children and young people in terms of culture (The Swedish Arts Council Citation2019).

Of specific interest above, in relation to the current study, are the words “everyone”, “quality”, “renewal”, “developed” and “accessibility.” These concepts underline the idea that even elderly individuals have the right to meet, act, and elaborate through artistic expression. Furthermore, when it comes to rights which are specifically oriented toward elderly people, the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights becomes interesting (The European Parliament Citation2000). The 25th paragraph states that: “The Union recognizes and respects the rights of the elderly to lead a life of dignity and independence and to participate in social and cultural life” (14). Again, cultural activities should be offered to all citizens in Sweden, regardless of where they live in the country.

However, for the Norrbotten region, there is no documentation encouraging artistic activities for the elderly, even in documents which allude to treatment and promote health in institutions. The above-mentioned steering documents therefore constitute the guidelines for anyone living in Norrbotten as a province of Sweden. They clearly support the rights of elderly people throughout Sweden to take part in contemporary dance workshops, for example.

The specific aim of the study is to describe and analyze the experiences of women aged over 65 in a rural area, who participated in contemporary dance workshops as a form of artistic expression. The research question was formulated as follows: How is the phenomenon of participation in contemporary dance workshops experienced among elderly women in Norrbotten?

The workshops that form the basis for the current investigation were designed in a way that offered the participants the opportunity to train, use, and develop technical, personal, and communicative skills. Warm-up activities, choreography, and improvisation were combined in each class. The workshops were taught in two separate dance studios by a professional dancer and choreographer with many years of teaching experience. An assistant also attended both workshops. The assistant only demonstrated the dance material used in the workshops. The choreographer’s aim was that the workshop should be received as a creative place where the participants could dwell together in dance as an artistic form of expression. Even the improvisational parts were practiced and developed in a conscious way.

First, the choreographer suggested that participants use circle movements to develop a warm-up activity. Then the participants were encouraged to walk around with their eyes directed toward the floor. Gradually, they were asked to make eye contact, and thereafter bodily contact. Different forms of input were used to encourage improvisation, such as metaphors, music, and movement prompts written on small pieces of paper. The goal was that the different activities and the mix between them, where the participants’ earlier experiences were used and developed in relation to new movements and forms of communication, should lead to something new.

As a theoretical concept for understanding the phenomenon of participating in contemporary dance workshops, Heidegger’s concept of dwelling is used. In addition, de Beauvoir’s thinking on aging is deployed to shed philosophical light on the weight of creative and intellectual activities in an older age group.

Theoretical Framework

According to Heidegger (Citation1945/1976), dwelling is an essential concept in terms of who human beings are and who they can become, as it accounts for all behavior and informs everything human beings do. Dwelling could be defined as sharing, in the way that genuine sharing helps something to achieve its own essence. Hence, in dwelling, human beings grow toward their full potential. This kind of sharing takes place in the field of tension, or logical space that organizes humans’ lives and projects. It takes place between birth and death, earth and sky, history and imagined futures, being (what human beings are) and becoming (what human beings make out of existing conditions). Heidegger (1945) underlines that dwelling must take place in relation to something, which makes it interesting to see dance as a place for dwelling.

Benson (Citation2003) offers an interesting view of musical being, based on Heidegger’s (Citation1941) view of dwelling, where he sheds light on the social-relational aspect. This view can easily be transferred to dance as a form of common being. A piece of art—dance as well as music—can, according to Benson, be seen as offering a place for dwelling, or a “space in which to dwell” (Benson Citation2003, 31). Hence, this place is not only for the artists but also the audience. Consequently, from a dance perspective, dance as a work of art can be seen as an environment for expressing and communicating dance, where human beings are and become dancing human beings in the field of tension. In other words, the dancers, audience, and choreographers can dwell in the world the dance expression creates. Accordingly, dwelling is preferably characterized as common “improvisation,” where dance as an art form is discovered and developed at the same time. On this note, Benson (Citation2003, 32) concludes that dwelling “transforms the space in which one dwells.”

It should be noted that dwelling does not take place in a vacuum (Heidegger 1945). It occurs in intersubjective settings such as dance workshops, where sharing experience is crucial. As mentioned above, dance dwelling takes place in specific contexts, communities, or styles which are in one way or another connected to genres—logical spaces that organize life. Different genres imply different forms of expression, communication, and perception, as well as different values. Contemporary dance and the warming up established in classical dance studios imply specific kinds of instruction, communication, and movement, which can be seen as aspects of arts learning. Expectations and possible imagination are influenced by earlier experiences, and dwelling takes place in the tension between history and possible futures. When the world is shared, structures are constituted. These guide the lives of human beings and are constantly being reconstructed. Seeing the world as intersubjective implies that individual beings are closely intertwined with other human beings. This view also forms the basis for de Beauvoir’s (1972) thinking on age and aging.

de Beauvoir’s (Citation1972) thoughts offer a philosophical perspective on the importance of social, political, intellectual, and creative input and activities as people grow older, as in all other phases of life. As Bose (Citation2011) underlines in her reading of de Beauvoir, the body is transformed during the aging process, “not only in the physical sense, but more importantly in the sense of restricted existential possibilities” (104). This underlines the importance of allowing old (female) bodies to express themselves artistically. According to de Beauvoir (Citation1972), elderly people ask, “Can I have become a different being while I still remain myself?” (283). This makes it important to create situations where the elderly are offered the opportunity to experience themselves and others anew. As de Beauvoir puts it, “in order to resolve the ‘identification crisis’ we must unresolvedly accept a new image of ourselves” (de Beauvoir Citation1972, 296).

Furthermore, de Beauvoir (Citation1972) stresses that if the body loses its functions, an aging person becomes less individual and has to find an alternative way of relating to others. Otherwise, there is a risk that she will withdraw from engagement with others or become an object for others. “In this way she shows how bodily changes alter human beings’ experience of time” (106). Hence, how human beings act in the present is influenced by how they view options for the future. As the years go by, the future shortens while the past grows heavier (de Beauvoir Citation1972).

Elderly people, according to Bose’s (Citation2011) reading, tend to identify themselves with projects in which they were involved earlier in their lives. Old age, according to de Beauvoir (Citation1972), is haunted by the memories of childhood and youth. Taking part in creative and intellectual work challenges how everyday structures for life are organized, and instead offers new possibilities. Hence, taking part in artistic activities could be a way of taking life seriously, and could therefore offer options for being and becoming, despite a rapidly shrinking future.

Aging is, according to de Beauvoir’s (Citation1972) way of thinking, a common as well as individual process. The expressions in the policy documents referred to earlier in the text could be interpreted as meaning that the society we live in is obliged to create situations where elderly citizens can be themselves and the condition of being old is actually acceptable. de Beauvoir stresses that “we must live a life so committed, so justified, that we can continue to cherish it even when all our illusions are lost and our ardor for life has cooled” (Citation1972, 567). This demands a conscious approach to awareness of death. de Beauvoir’s philosophy of aging functions as a foundation in terms of what it can mean for the elderly to participate in dance workshops, and as an incentive to investigate the workshop series in terms of situations where elderly people can be and become; realizing their full potential through communication.

Method

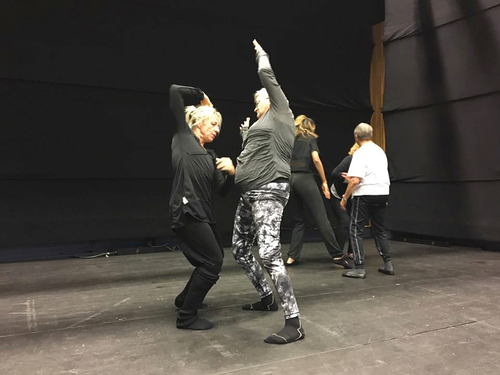

The study involves two dance workshops in the northern part of Sweden, where only women showed an interest in taking part (see ). The workshops, conducted as a part of a larger research project, Age on stage, took place in two cities in the northern part of Sweden during the fall of 2017.

Each workshop lasted for two hours and was led by a professional choreographer, Charlotta Övferholm, and her assistant, Anna Hjärpe, in two different dance studios.

Altogether nine elderly, nonprofessional dancers participated in the workshops. Information about the workshop was communicated through an email sent out through the choreographer’s own connections as well as through organizations connected to elderly people in Norrbotten. All participants were currently living in the north, except one who traveled from Stockholm, where she had participated in an earlier Age on stage workshop in 2016. Participants can therefore be said to have been recruited through convenience sampling (Flick Citation2014), and those who applied to participate in the workshops also became the participants in the study. All the participants were able to communicate via e-mail.

The workshops were observed and documented by two collaborating researchers using field notes, photographs, and video recordings. By e-mail and via informal chats directly after the workshops, participants were also asked questions about their background, their relations to dance, and their experiences of taking part in the workshops. The choreographer and the participants gave full permission to use their words and the photographs in publications.

Both researchers were present in the dance studio, as nonparticipating observers sitting next to each other in one of the corners of the room. Their presence in the room made it possible for them to gain a full picture of the activity (Wragg Citation2013). The researchers were aware that their presence could affect the context in terms of how relaxed and “natural” the participants might appear and how they might express themselves through dance. To complement the field notes, which were written by hand, photographs were taken, and the workshops were video recorded through an iPad. Hence, the material which formed the basis for analysis included the participants’ verbal and bodily expression, their experiences of the workshops, and their earlier experiences of dance. Although the sample was small, the case generated material consisting of four hours of video recordings, 30 pages of handwritten notes, around 40 photographs and ten pages of e-mail text. This made it possible to say something about the experiences of participating in relation to age and life.

To be able to grasp the phenomenon of participating in contemporary dance workshops within a context of arts learning among elderly, and to offer a presentation that invited the reader to take the perspective of the elderly (de Beauvoir Citation1947), a narrative analysis was conducted (Clandinin, Pushor, and Orr Citation2007; Barrett and Stauffer Citation2009, Citation2012). The produced material involved both verbal and bodily expressions (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2007). Narrative analysis can be defined as a method where participants’ stories are re-told by researchers. Not necessarily in the same form, but always focused on temporality, sociality, and place in the original stories (Clandinin, Pushor, and Orr Citation2007). “Storytelling, to put the argument simply, is what we [researchers] do with our research materials and what informants do to us” (Kohler Riessman Citation2002, 218). To make the final story understandable and trustworthy, nuances in expressed stories have to be taken into account as well as transformed in a process where the researchers’ voices are outedited, and where the participants’ voices are developed toward linear language (Millett Citation1975).

Hence, the process of analysis focused on temporality, sociality, and place (Clandinin, Pushor, and Orr Citation2007), and ensured that all participants’ voices and bodily expressions were heard and “seen.” The participants’ “voices” were used to generate a story, told by a fictitious female participant (Bowman Citation2006; Clandinin, Pushor, and Orr Citation2007; Byrne Citation2015). Such an approach can be defined as narrative as based on a theory for re-telling (Barrett and Stauffer Citation2009; de Fina and Georgakopoulou Citation2015), as exemplified by Källén (Citation2021), for example. No expressions were left out. Instead, the voice expresses the results of the analysis in terms of what constitutes the phenomenon of participating in the chosen situations. We tried to use the language of the interviewees, to guarantee that they recognize their values, intentions, and actions, which are crucial in a result of narrative analysis (Bowman Citation2006). Temporal aspects related to how this had developed life experiences, and how it had influenced the participants’ relation to dance in general and the workshop specifically. Sociality involved situations relating to dance earlier in the participants’ lives, as well as interrelations within the workshop activities. Aspects involving place made contextual factors of learning and communication in, about, and through dance into an artistic form of expression (Clandinin, Pushor, and Orr Citation2007). The narrative was shown to the participants, and all of them recognized their experiences and expressions in the text (Byrne Citation2015).

The narrative was then interpreted through the theoretical lenses of Heidegger and de Beauvoir, which highlighted some specific themes. The theories were used to elaborate on the themes and, at a more general level, to describe and analyze the phenomenon of participation in contemporary dance as a form of artistic expression among elderly dancers in rural areas.

Results

The following section presents a narrative that describes the elderly women’s approach to the workshops, their experiences of them, and how they visualized themselves within them. The narrative uses a fictitious woman’s voice, representing the analysis of all the bodily and verbal experiences expressed by the participants. The narrative is then commented on through the theoretical framework.

I am a woman, born in Norrbotten in the northern part of Sweden, where I also spent all my life, which has now run for 76 years. I was happy when I saw the invitation to the dance workshop for elderly people. I must admit that I was a bit nervous, both for the dance per se, and also regarding meeting the other participants. But the nervousness disappeared as soon as Charlotta (the choreographer) introduced herself to us, and all of us to each other. It was like an exciting adventure, but at the same time safe. All of us were kind of life-experienced, between 68 and 85, and curious about the dance activities. I mean, most of us did go out dancing when we were younger, to meet someone, and some of us had tried dance courses, but generally we had set our own interests aside when we got married and had a family.

Charlotta guided us into the dance through warm-up activities. We got to know that the floor supports us, our heaviness supports us, and that the air is our partner. She used proper dance terms, like “first-position,” and was at the same time very careful about how we used our bodies, to avoid us hurting something or losing our balance. It was a bit unfamiliar to use our bodies in that way, but fun and exciting. Gradually she moved into something more improvisational, where we made circle movements with different parts of the body, individually and later on more and more together.

We were to lead each other, which felt like intimate training in trust—Oh my God … I must say that it felt more comfortable to be led than to lead, I don’t really know why … It also felt like I became aware of how my body could be used. Charlotta accentuated the center. I feel that is something to think about in everyday life as well. She also used different kinds of music, new music for me, and it was interesting how the music influenced how I, and we, moved in relation to that.

Later I felt more and more secure in actually expressing myself. Alone, in communication with the others, and in togetherness. She encouraged us to develop our own language, our own personality in relation to the music, and actually I thought that was kind of possible, even if the time was very short. All of us were to perform small solos, a little bit nervous, but fun, and it worked. It’s like this to meet each other in free dance, face to face—releases deeper feelings, not the least which is happiness. This small group of people offered a feeling of closeness.

We were to learn choreography as well. That was a bit hard, but fascinating, to be a part of a whole, a common moving body. We also formed it like a kind of performance with an imagined audience. That was fun. And kind of new. But I appreciated expressing myself more freely in improvisation the most, although within given frames. It was kind of releasing. I really wish that more people of my age had come, but of course, you have to be brave, as you don’t know what it is about beforehand. The information wasn’t easy to find either. And many elderly people in our region don’t have a car, and public transport does not work properly.

I felt so full of energy in the end. “I will be crazy when I get home,” I said. I really felt that our age made us shameless, and the workshop activities were totally prestigeless. Everyone dared to participate and didn’t worry if we didn’t manage everything. It was also a good way to keep the body flexible and limber. I wish this kind of dance was available for us old people, or elderly, instead of gyms with stiff machines, devoid of coordination and feelings. And it was so nice to meet other people in that way, totally different from meeting at a party or any other kind of gathering. This kind of dance gives joy and stimulation. I would say that dancing is a way of being or living. To dance is to live, and also a way to meet, and become, yourself.

From a de Beauvoir (Citation1972) perspective, the narrative indicates that the dancers are closer to death than birth, but that the dance makes them somehow ageless, and that they get to use their lived experiences in learning who they are, and what they can become, in the dance activities. Dance offers them opportunities to understand and organize life in new ways, without losing contact with their history and everyday life, even for elderly women in a rural area. It also becomes clear that the elderly body can be used, if handled carefully, to develop new expression. The social aspect of dwelling in art, which Benson (Citation2003) accentuates, is also manifest in the narrative. The dance activities—in the form of choreography as well as improvisation—were seen as a dwelling place, and the choreographer, dancers, and audience worked together with “the given” (what is available) to create something new.

The narrative is testimony to the fact that the elderly people got to know themselves better, and got to know each other, through different kinds of bodily communication within the field of tension. In the dance situations, the participants were encouraged to move toward each other in specific ways based on their prior experiences, which in turn shaped the way they viewed themselves, others, and what was possible in the situation. The balance between improvisation and choreography in the workshops seemed to offer varied spaces for dwelling. The dancers were recommended to handle their bodies carefully and were offered ways of developing simple tools for improvisation. The choreographer met the women on earth and gave them the opportunity to find their own form of expression through dance, to create something new and come closer to the sky, and to talk with de Beauvoir. It is also possible to say that they used their history to imagine possible new futures. It became clear that the way the parts of the dance offered spaces for dwelling altered the expression itself. The way the choreographer approached and related to contemporary dance seemed to create a safe space for dance as a dwelling space for the elderly dancers.

It was clear that this sense of dwelling did not, as Heidegger (Citation1945) underlines, take place in a vacuum. It happened in the intersubjective setting described in the narrative. The dancers were directed toward each other, to individual and collective movements, and to the music. They arrived with different experiences of dance, ways of expressing dance, dance forms, and expectations of choreography. Therefore, sharing their experience was crucial. Contemporary dance was rather new for all the participants and gave them freedom within the clear framework mediated by Charlotta. Hence, the elderly also developed a new logic for organizing their life in the specific dwelling space provided by the workshops.

It is also clear from the narrative that the participants’ image of themselves changed in the artistic, communicative setting. For example, the female voice in the narrative highlights how the body was used in new ways, how she and the others could communicate through new expression, how feelings were released, and how dance was seen as a new way of living. As de Beauvoir underlines, old age is haunted by the memories of childhood and youth, which is in line with what the fictitious woman in the narrative says. The risk of taking “refuge in habit” (de Beauvoir Citation1972, 466), is challenged in the dance workshop, as there is no agreed way of acting for participants to lean on. The narrative shows how structures for organizing life are challenged and how new possibilities were offered in the dwelling space.

Hence, participating in contemporary dance workshops can be seen as a way of taking life seriously, and possibly as a form of being and becoming for the elderly, even if they saw their future shrinking. Regardless of where and how a human being was raised and socialized, different experiences become stimulating, encouraging, and challenging. This is also clear in the group of participants in the current study. The narrative illustrates how the dancers transcended their bodies and became themselves in different ways. They “danced into the future.” Despite the fact that the workshop was short, the participants seemed to find meaning in the moment, and dared to use their past to create new futures. Even as mortality drew closer, and became something they clearly related to, they experienced dance as a way to live, and also a way to meet, and become, themselves. To relate de Beauvoir’s thoughts to the present study, taking part in dance workshops is about offering oneself the stimulating situations de Beauvoir considers important.

Final Comments

The aim of the study was to describe and analyze the experiences of women over 65 in a rural area, who participated in contemporary dance workshops as a form of arts learning. The above results and interpretation, through a philosophical lens, show how participation in contemporary dance activities can offer spaces where human beings can dwell within a field of tension between birth and death, earth and sky, history and imagined futures, and being (what human beings are) and becoming (what human beings make out of existing conditions). It illustrates how important such activities are for elderly human beings. This existential dimension of participation in dance activities can be seen as adding to earlier research on the positive effects dance can have on participants’ health and wellbeing. The experiences of the dancers indicate that dancing is a way of being or living, and that to dance is to live, and also a way to meet, and become, oneself.

To broaden the view of the phenomenon, dance as a dwelling place can be seen as a phenomenological body where the participants are inter–related and work together as different organs with complementary skills and actions, where all actions involve every participant (Stubley Citation1998, 93–105). “The body” is closely connected to the world through the life–worlds of the participants, their experiences, and their expectations. The boundaries of the body change, depending on how “the body” is directed. When the participating elderly dancers were asked to develop choreography or improvise collectively, the boundaries of “the body” had to include the whole group. New common goals and ways of imagining had to be established.

Later, when an imaginary audience was included in the “body” or the dwelling space, the process evolved, and the imagination and opportunities for dwelling changed. All participants in the “new” living body had to be present, open, and engaged, and they all had to make use of representation and be imaginative to develop common expression. They seemed to be able to connect with their feelings and allow their reflections to connect to their existence in the world. They were learning dance as an essential and existential form of expression. All the guidance documents mentioned above indicate that settings like this for arts learning should be available to all human beings, regardless of age (The European Parliament Citation2000; The Swedish Parliament Citation2015; The Swedish Arts Council Citation2019; UNESCO Citation2019).

The possibilities for dwelling within a style, like contemporary dance, are manifest in questions such as: To what extent is it possible to change, adapt, and develop the movements? What moves can be used and by whom? What patterns are permitted? How do the participants’ expectations of the genre influence the outcome? Dance as a form of arts learning could be used to organize activities which invite participants, both creators and perceivers, to share experiences in ways that both maintain and challenge traditions, and the workshop seemed to achieve this very successfully.

Furthermore, the results of the study highlight the issue of why contemporary dance workshops should be organized for elderly women, or individuals in general, in rural areas. The study illustrated how contemporary dance for elderly women can function as an important place for dwelling, a way of being and a way of coping with life—a space for learning in later life. Another aspect involves a question regarding who has the right to express themselves in and through dance. Policy documents at different levels indicate that everyone should have the right to make themselves heard through a variety of forms of expression. All participants in the groups seemed to take part and develop equally, even though men were not represented, and not all people in the 65–85 age group in the area took part. Although this study focuses on specific conditions in terms of female participation, it is relevant to ask why men showed no interest in taking part, unlike in similar activities in Stockholm (Andersson and Ferm Almqvist Citation2021).

Another theme which could be elaborated on involves the barriers and opportunities which were highlighted in terms of elderly people expressing themselves through dance at individual, institutional, and societal levels. Despite the fact that the workshops lasted only two hours each, barriers to learning were identified and overcome. Some of the barriers were: anxiety, fear of making a fool of oneself, and fear of being left out. These fears were alleviated by the empathetic approach of the choreographer leading each session as well as the friendliness of all the participants toward one another. The limits of the body were overcome through adaptation. The clearest barriers appeared to be expectations about the people the workshops were aimed at as well as transportation and information. People in Norrbotten are not expected to participate in dance workshops, even if contemporary dance is well established in the area. At least the participants in the workshops did not consider their age to be an explicit hindrance in terms of participation, as the title of the paper implies.

The implications of this study, despite its limitations, are that creative and intellectual activities should be offered to elderly people not just as medical treatment or therapy, but as opportunities for existential and essential learning. To be and become is a natural human way of living. If the settings elderly people attend do not offer new ways of thinking, new ways of communicating, and new ways of imagining the future, life during old age will be meaningless. If older people are to see themselves as developing human beings—curious about themselves and others, and about society and life—creative settings will be required, organized according to a different logic to the one underpinning everyday life. Cultural programming in rural areas presents a challenge to politicians as the cultural life is thinner than in bigger cities. Traditions are conservative when it comes to what elderly people (not only men) are expected to do, and transport poses a problem, given the distances to facilities. Hence further research is recommended which includes a variation of artistic expression in elderly people in rural areas.

References

- Alpert, Patricia T., Sally K. Miller, Harvey Wallmann, Richard Havey, Chad Cross, Teresia Chevalia, Carrie B. Gillis, and Keshavan Kodandapari. 2009. “The Effect of Modified Jazz Dance on Balance, Cognition, and Mood in Older Adults.” Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 21 (2): 108–115. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00392.x.

- Andersson, Ninnie, and Cecilia Ferm Almqvist. 2020. “Dance as Democracy among People 65+.” Research in Dance Education 21 (3): 262–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2020

- Andersson, Ninnie, and Cecilia Ferm Almqvist. 2021. “‘To Get the Chance to Dance Myself’ – Dance as Democracy among People 65+.” Research in Dance Education 21 (3): 262–279. doi:10.1080/14647893.2020.1766007.

- Barr, Sherrie. 2013. “Learning to Learn: A Hidden Dimension within Community Dance Practice.” Journal of Dance Education 13 (4): 115–121. doi:10.1080/15290824.2012.754546.

- Barret, Margaret S., and Sarah Stauffer, eds. 2012. Narrative Soundings: An Anthology of Narrative Inquiry in Music Education. London: Sage.

- Barrett, Margaret, and Sandra Stauffer. 2009. Narrative Inquiry In Music Education. Troubling Certainty. Amsterdam: Springer.

- Benson, Bruce E. 2003. The Improvisation of Musical Dialogue. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berson, Jessica. 2010. “Old Dogs, New Tricks: Intergenerational Dance.” In Staging Age. The Performance of Age in Theatre, Dance, and Film, edited by Valerie Lipscomb and L. Marshall, 165–189. New York: Palgrave.

- Borgström Källén, Carina. 2021. “Woman and Full Professor in Music Education – Work Experiences in the Field of Academia.” In Higher Education as Context for Music Pedagogy Research, edited by E. Angelo, J. Knigge, M. Sæther, and W. Waagen, 245–268. Trondheim: Cappelen Damm Akademisk. doi:10.23865/noasp.119.ch10.

- Bose, Seema. 2011. “Focus on Ageing – A Neglected Aspect of Simone de Beauvoir’s Radicalism.” Annals of the University Press of Bucharest Philosophy Series LX (2): 103–107.

- Bowman, Wayne D. 2006. “Why Narrative? Why Now?” Research Studies in Music Education 27 (1): 5–20. doi:10.1177/1321103X060270010101.

- Byrne, Gillian. 2015. “Narrative Inquiry and the Problem of Representation: ‘Giving Voice’, Making Meaning.” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 40 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2015.1034097.

- Camic, Paul M., Victoria Tischler, and Chantal Helen Pearman. 2014. “Viewing and Making Art Together: A Multi-session Art-gallery-based Intervention for People with Dementia and Their Carers.” Aging and Mental Health 18 (2): 161–168. doi:10.1080/13607863.2013.818101.

- Clandinin, Jean D., Debbie Pushor, and Anne Murray Orr. 2007. “Navigating Sites for Narrative Inquiry.” Journal of Teacher Education 58 (21): 21–35. doi:10.1177/0022487106296218.

- de Beauvoir, Simone. 1947. The Ethics of Ambiguity. Missouri: Webster University Philosophy Department: Citadel Press.

- de Beauvoir, Simone. 1972. The Coming of Age. New York: Norton and Company.

- de Fina, Anna, and Alexandra Georgakopoulou. 2015. The Handbook of Narrative Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Dickinson, Barbara. 2010. “Age and the Dance Artist.” In Staging Age. The Performance of Age in Theatre, Dance, and Film, edited by Lipscomb Valerie, and L. Marshall, 191–206. New York: Pelgrave.

- Duncan, Ryan P., and Gammon M. Earhart. 2014. “Are the Effects of Community-Based Dance on Parkinson Disease Severity, Balance, and Functional Mobility Reduced with Time? A 2-Year Prospective Pilot Study.” The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 20 (10): 757–763. doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0774.

- The European Parliament. 2000. Official Journal of the European Communities.

- Ferm Almqvist, Cecilia, and Ninnie Andersson. 2019. “To Offer Dance as Aesthetic Experience and Communication among People 65+.” International Journal of Education in the Arts 20 (12). http://doi.org/10.26209/ijea20n12

- Fernández-Argüelles, Esther L., Luis E. Rodríguez-Mansilla, Elisa. M. Juan Antunez, and Rafael P. Garrido-Ardila. 2015. “Effects of Dancing on the Risk of Falling-Related Factors of Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review.” Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 60 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2014.10.003.

- Flick, Uwe. 2014. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 5th ed. London: SAGE.

- Fortin, Sylvie. 2018. “Tomorrow’s Dance and Health Partnership: The Need for a Holistic View.” Research in Dance Education 19 (2): 152–166. doi:10.1080/14647893.2018.1463360.

- Green, Jill. 2000. “Power, Service and Reflexivity in a Community Dance Project.” Research in Dance Education 1 (1): 53–67. doi:10.1080/14647890050006587.

- Hackney, Madeleine E., and Gammon M. Earhart. 2009. “Effects of Dance on Movement Control in Parkinson’s Disease: A Comparison of Argentine Tango and American Ballroom.” Journal Rehabilitation Medicine 41: 475–481. doi:10.2340/16501977-0362.

- Hartogh, Theo. 2016. “Music Geragogy, Elemental Music Pedagogy and Community Music – Didactic Approaches for Making Music in Old Age.” International Journal of Community Music 9 (1): 35–48. doi:10.1386/ijcm.9.1.35_1.

- Heidegger, Martin. 1945/1976. What is Called Thinking. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Heidegger, Martin. 1941. Basic Concepts. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- In-Sil, Park, Ji-Young Kim, Soon-Jeong Cho, and Hyun-Jung Park. 2015. “The Relationship between Wellbeing Tendency, Health Consciousness, and Life Satisfaction among Local Community Dance Program Participants.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 205: 211–220. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.061.

- Kattenstroth, Jan-Christoph, Tobias Kalisch, Stephan Holt, Martin Tegenthoff, and Hubert R. Dinse. 2013. “Six Months of Dance Intervention Enhances Postural, Sensorimotor, and Cognitive Performance in Elderly without Affecting Cardio-Respiratory Functions.” Frontiers In Aging Neuroscience 5: 5. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2013.00005.

- Kohler Riessman, Catherine. 2002. “Narrative Analysis.” In The Qualitative Re-searcher’s Companion, edited by A. M. Huberman, and M. B. Miles, 217–270. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Kvale, Steinar, and Svend Brinkmann. 2007. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. London: Sage Publications.

- Laes, Tuulikki. 2015. “Empowering Later Adulthood Music Education: A Case Study of A Rock Band for Third-Age Learners.” International Journal of Music Education 33 (1): 51–65. doi:10.1177/0255761413515815.

- Laes, Tuulikki. 2018. “Policy and Practice of Lifelong Music Education in Aging Societies.” Symposium presentation at the 33RD ISME WORLD CONFERENCE 2018, Baku, Azerbaijan.

- Lehikoinen, Kai. 2019. “Dance in Elderly Care: Professional Knowledge.” Journal of Dance Education 19 (3): 108–116. doi:10.1080/15290824.2018.1453612.

- Lerman, Liz. 1976. Teaching Dance to Senior Adults. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas Publisher

- Lindberg, Boel. 2012. “Cultural Policy in the Swedish Welfare State.” http://www.boellindberg.se/Textarkiv/BLAsantext.pdf.

- MacMillan, Thalia. 2016. “An Exploration of Older Adults’ Perceptions and Motivating Factors behind Participation in Dance.” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Review 2 (1): 23–35.

- Merom, Dafna, Anne Grunseit, Ranmalee Eramudugolla, Barbara Jefferis, Jade Mcneil, and Kaarin J. Anstey. 2016. “Cognitive Benefits of Social Dancing and Walking in Old Age: The Dancing Mind Randomized Controlled Trial.” Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 8. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2016.00026.

- Millett, Kate. 1975. The Prostitution Papers: A Candid Dialogue. London: Paladin Books.

- Nakajima, Nanako. 2011. “De-aging Dancerism? The Aging Body in Contemporary and Community Dance.” Performance Research 16 (3): 100–104. doi:10.1080/13528165.2011.606033.

- Pearce, Ruth, and Sue Lillyman. 2015. “Reducing Social Isolation in a Rural Community through Participation in Creative Arts Projects.” Nursing Older People 27 (10): 33–38. doi:10.7748/nop.27.10.33.s22.

- Phinney, Allison, Ellaine M. Moody, and Jeff A. Small. 2014. “The Effect of a Community-Engaged Arts Program on Older Adults’ Well-Being.” Canadian Journal on Aging 33 (3): 336–345. doi:10.1017/S071498081400018X.

- Schmidt, Patrick, and Richard Colwell. 2017. Policy and the Political Life of Music Education. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Serra, Marcos M., Angelica C. Alonso, Mark Peterson, Luis Mochizuki, Júlia M. D. A. Greve, and Luiz E. Garcez-Leme. 2016. “Balance and Muscle Strength in Elderly Women Who Dance Samba.” PLoS One 11 (12): e0166105. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0166105.

- Shigematsu, Ryosuke, Milan Chang, Noriko Yabushita, Tomoaki Sakai, Masaki Nakagaichi, Hosung Nho, and Kiyoji Tanaka. 2002. “Dance‐based Aerobic Exercise May Improve Indices of Falling Risk in Older Women.” Age and Ageing 31 (4): 261–266. doi:10.1093/ageing/31.4.261.

- Söderman, Johan, and Maria Westvall. 2017. “Community Music as Folkbildning: A Study of A Finnish Cultural Association in Sweden.” International Journal of Community Music 10 (1): 45–58. doi:10.1386/ijcm.10.1.45_1.

- Soriano, Christina, and Glenna Batson. 2011. “Dance-Making for Adults with Parkinson Disease: One Teacher’s Process of Constructing a Modern Dance Class.” Research In Dance Education 12 (3): 323–337. doi:10.1080/14647893.2011.614334.

- Stubley, Eleanor V. 1998. “Being in the Body, Being in the Sound: A Tale of Modulating Identities and Lost Potential.” Journal of Aesthetic Education 32 (4): 93–105. doi:10.2307/3333388.

- The Swedish Arts Council. 2019. “Cultural Policy Objectives.” http://www.kulturradet.se/en/In-‐English/Cultural-‐policy-‐objectives.

- The Swedish Parliament. 2015. “The Basic Law on Freedom of Expression.” https://www.riksdagen.se/globalassets/07.-dokument–lagar/the-fundamental-law-on-freedom-of-expression-2015.pdf

- The Swedish Parliament. 2019. “Cultural Policy.” https://www.government.se/government-policy/culture/

- Toygar, Ismail. 2018. “Dance Therapy in the Rehabilitation of the Parkinson’s Disease.” International Journal of Caring Sciences 11 (3): 2005–2008.

- UNESCO. 2019. “UNESCO and the Declarations of Human Rights.” https://en.unesco.org/udhr.

- Wragg, Ted. 2013. An Introduction to Classroom Observation (Classic Edition). New York: Routledge.

- Ying, Sun. 2010. “Preliminary Data. Research Summary. Dance and Exercise Benefits in Parkinson’s Disease.” Neura. Report for the 14th International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, Buenos Aires, Argentina, June 13–17. Accessed 2 July 2010. http://www.neura.net/images/pdf/MDS2010_NSR.pdf