ABSTRACT

This article proposes a decolonial choreographic process rupturing the historical locus of enunciation in a dance program at a tertiary institution in South Africa. This locus in choreographic composition curricula in such universities reflects Western modernity, resulting in epistemological hegemony that creates epistemic othering that, we argue, affects students’ ontological positioning. We view decoloniality as centered on rupturing the historical locus of enunciation through epistemic disobedience and delinking from coloniality/modernity. We argue that one pedagogical approach in a choreographic composition curriculum is through using embodied, autobiographical memories toward decolonial storying. We discuss the ways this decolonial option shaped the choreographic process toward the performance of Memoryscapes (2022). We conclude by demonstrating how this option surfaced the participants as the loci of enunciation(s), by drawing from their identities, subjective lived experiences, and autobiographical memories in the process of embodied decolonial storying.

Introduction

I remember that I do not remember the things I said I would always remember

I have forgotten to forget the things that I always wanted to forget

So I remember

I remember seeing my mother slip and fall in the mud while it was pouring with rain

I remember tears pouring out of my eyes with pain

I remember that moment, but I had said I do not want to remember

I remember that I have forgotten

But I have forgotten to remember (Participant 1ʹs memoryscape)

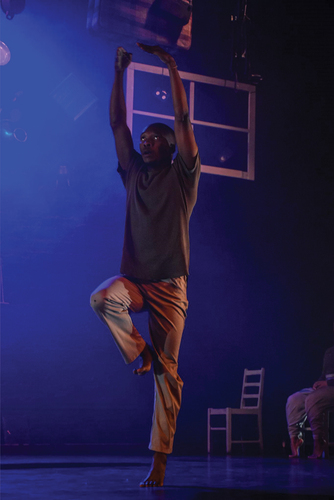

Participant 1 moves his memoryscape with a nuanced, personal movement language citing elements of his Zulu cultural background through his expressive embodied engagement in space and time. Lights focus on his face, revealing the topography of his skin that illuminates the contours of his being. He spirals, he carves the space as he breathes life into his memories. His shaking and vibrating reveal his continued becoming as he conjures the past into the present. His movement motifs are repeated and reiterated, as threads of memories intertwine. His gestural language weaves a delicate portrait of feelings as he stamps his feet on the earth, rooting himself in spiritual interconnection. His meshwork of memories leads into a soundscape of all the memories spoken into being. His embodied storying of his autobiographical memories, we argue, forms part of the process toward creating a decolonial praxis in a dance program in South Africa. shows participant 1 dancing his memoryscape.

This description of a solo performance from the production Memoryscapes (2022) is a process that reveals the connection between autobiographical memories, storying, culture, feelings, and identity that are brought into being through embodiment in the world. The choreographic process of memoryscapes aim to set up a mode of engaging with choreographic composition that resists the dominant pedagogical approach at a dance institution in South Africa. The dominant pedagogical approach was, and arguably is, rooted in a dualist ontology reflective of Western modernity. Dualism, with its mind/body hierarchy, creates “divided beings” (Leach Citation2018, 113) that have/had a hegemonic hold on Western thinking for centuries, impacting amongst others, education (Anderson Citation2021). In dance and performer training, the hegemonic hierarchy became the “dominant hegemonic ontology” (Leach Citation2018, 114). Modernity is a cultural model and a historical and epistemic frame within which to position the historical development and identity of Europe that spread over the world using colonialism, amongst other processes (Mignolo Citation2011). Modernity, with its dualist tendencies and Eurocentric worldview, presupposes a speaking, thinking, and doing from this specific locus of enunciation that became “universalized” through a myriad of processes that included colonization.

For Grosfoguel (Citation2011, 6), the locus of enunciation is “the geo-political and body-political location of the subject that speaks” that is embodied in individuals’ engagement with the world. A locus of enunciation is shaped by ideology and historical context, as well as how knowledge is created (epistemology), which affects being-in-the-world (ontology) (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2013b). The locus of enunciation is important in understanding the perspectives, contexts, and value systems that drive knowledge production and related discourses, how knowledge is created, and how notions of what constitutes valid knowledge are generated (Mignolo Citation1999). These conflicts are often rooted in colonial histories and their associated locus of enunciation: Western modernity. This locus of enunciation, with its universalizing impetus, marginalizes African/indigenous epistemes and prioritizes Western rationality, logocentrism, values, approaches, and knowledge systems, producing epistemological hegemony. This calls for a decolonial practice.

This article argues for a decolonial choreographic process that aims to rupture the historical locus of enunciation toward a decolonial praxis in a dance program in South Africa. In order to rupture the locus of enunciation, a process is needed to facilitate epistemic disobedience and delinking from coloniality/modernity (Mignolo Citation2007). This disobedience and delinking might be achieved through exploring pedagogical approaches that foreground multiple monist ontologies and acknowledge the epistemology-ontology interweave. We argue that such a pedagogical approach in a choreographic curriculum is through using autobiographical, embodied memories toward decolonial storying.

Decolonization and the South African Higher Education Context

South Africa’s external colonizers brought Dutch and British knowledge systems, values, and artistic practices, among others, and centered these as part of a “civilizing” project (Jean and Comaroff Citation2012). The accompanying epistemicide, linguicide, and culturecide have far-reaching consequences for South Africa’s social organization, including education (Wa Thiong’o Citation1986). This Eurocentrism was later localized and became part of the sociocultural and political drive of Afrikaner Nationalism that gave birth to apartheid. The violent, brutal, and dehumanizing policy of apartheid created devastating systems that enforced continued colonialism in South Africa (Oliver and Oliver Citation2017), which still reverberates in the present. Apartheid instituted many inequalities and discriminatory practices and policies, amongst others, unequal education (Dreyer Citation2017). As we will discuss below, this refers to education that marginalized indigenous populations and knowledge systems in favor of Eurocentric education, a remnant of external colonialism, constituting the historical locus of enunciation.

South Africa has a fraught history where practices of universities serve as hegemonic structures upholding coloniality (Motsaathebe Citation2019). Universities in South Africa served/serve an epistemic project similar to that of colonialism and uphold/upheld its historical locus of enunciation that continues to marginalize “African knowledge systems, students’ linguistic and cultural identities” (Angu Citation2018, 9) as aspects of coloniality. Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Citation2013a, 63) posits that “the worst form of colonization … on the continent is the epistemological one that is hidden in institutions and discourses that govern the modern globe.” This insidious epistemological hegemony continues ongoing coloniality that needs to be addressed.

The transition in South Africa to democracy in 1994 arguably brought marginal education changes, as there are still vast inequalities in education standards, resources, and curricula that reflect South Africa’s racially divided history. The residue of colonial and apartheid epistemologies in many South African curricula continues to reinforce white and Western domination and privilege (Motsaathebe Citation2019, 38). The Eurocentric, Western domination was the impetus of the South African #FeesMustFall student protests of 2015 and 2016, where students called for a free, quality, decolonized tertiary education. Although universities have actively shifted curricula in response to the decolonial turn, many curricula arguably remain rooted in the historical, colonial locus of enunciation.

In the context of dance programs in higher education in South Africa, Samuel (Citation2016, vii) states that there was (and for us, arguably still is) an “epistemology of prejudice” based in Western dance forms, specifically ballet, which promotes a Western aesthetic. African dance forms were/are positioned as “primitive” or quasi-theatrical (Molobye Citation2022). This condescension reveals what kind of dance, knowledge about dance, and dancing body was appropriate (Rani Citation2018). This epistemological prejudice created a high (Western) and a low (African) art binary, reflecting the hegemony and associated privileging of certain bodies. The dominance of Western epistemologies is also seen in the use of Western theorists and theorems in dance curricula.

In light of South Africa’s history of marginalization and exclusion pertaining to the epistemological project and in relation to the broader social world and human interaction, the importance becomes clear regarding engaging with the enduring coloniality that students face in their daily interactions and in their dance curricula. Coloniality, embedded in the epistemological project pertaining to the curriculum we critique, impacts “epistemological understandings,” as well as how individuals perceive themselves and others (Yoon-Ramirez and Ramirez Citation2021, 114). Within the South African context, many universities are engaging with the process of decolonizing curricula and pedagogy, including the institution this article focuses on.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Citation2013c) defines decoloniality as “the agenda of shifting the geography and biography of knowledge–who generates knowledge and from where?”—and positioning it “to the ex-colonized epistemic sites as legitimate points of departure in describing the construction of the modern world order,” thus shifting the historical locus of enunciation. Decoloniality offers a critical perspective and a process of “undoing and redoing” (Mignolo and Walsh Citation2018, 120) that challenges the structures of power, knowledge, and culture that have been created and maintained through colonization and enduring coloniality. Coloniality becomes internalized epistemologically and ontologically (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2013b). Modernity/coloniality creates (continued) patterns of power (Maldonado-Torres Citation2007), including epistemological hegemony that, for Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Citation2013a), reverberates in the present and which need to be delinked. Delinking implies changing the terms of, and not just the content of, the conversation (Mignolo Citation2007).

In relation to higher education, decolonization is an ongoing struggle to make education relevant to the “material, historical, and social realities of the communities in which the university operates” (Letsekha Citation2013, 4). Pedagogical options carve possible paths toward decoloniality by delinking and rupturing the historical locus of enunciation, thereby fostering humanizing pedagogies (Dube and Mudehwe-Gonhovi Citation2022) that are responsive to students’ ontological positioning. If the historical locus of enunciation is not shifted, it will continue to create “epistemic othering” (Keet Citation2014, 23) that devalues many students’ indigenous knowledge systems and cultural backgrounds, thereby causing a sense of alienation and isolation in epistemic contexts. This epistemic othering causes “cultural dissonance” (Fomunyam and Teferra Citation2017, 199) in teaching and learning spaces. Thus, many curricula do not align with the students’ needs (Fomunyam Citation2016), frames of reference, sociocultural backgrounds, and knowledge systems, or as Lebeloane (Citation2018, 2) suggests, their “reasoning, sensing and views of life” in a South African context. As such, curricula and the concomitant pedagogical approaches often do not speak to students’ cultural life worlds, their being-in-the-world, their ontological positioning—their identities.

In our view, epistemic othering and cultural dissonance reach beyond the teaching and learning space in that the othering affects students’ ontological positioning, impacting their learning. The decolonial project should, therefore, foreground the relational interweave between epistemology and ontology that supports students’ diverse processes of becoming(s) in its drive to make, unmake, and re-imagine. A possible path, or a decolonial option in re-imagining ways of being, doing, and making interweaves epistemology and ontology through accessing embodied, autobiographical memories.

Embodied, Autobiographical Memories

The embodied, multimodal, bodyminded being is embedded in the environment and perceives, interacts, and is formed through the physical and social environment (Brown Citation2017), where embodiment views the bodyminded being as embodied in a socially and culturally situated process in a dynamic environment with a network of connections (Bluck and Habermas Citation2001). Through embodiment in the world, and more specifically through sensing, perceiving, moving, and experiencing, embodied and autobiographical memories are created.

Embodied memory includes the totality of the embodied subjects’ dispositions, senses, experiences, and perceptions that enable individuals to react to present situations based on past experiences (Koch, Fuchs, and Summa et al. Citation2012). Autobiographical memory refers to the personal memories of experiences relevant to individuals that form their life history, and which is the reconstruction of fragments of experience combined with knowledge of the experience and knowledge of “selves” (Ball Citation2010). These memories are not exact illustrations of reality but rather are constructed “stories.” Embodied, autobiographical memories are constructed from the various ways memories, body memory, procedural memory, habitual body memory, stories, and identities converge and interlink to create a sense of self—a bodyminded identity that offers a sense of “you-ness” (Shaw Citation2016, xi). Thus, autobiographical memory in the context of embodied practices of remembering is intertwined with procedural body memory that results in habitual body patterns, and this contributes to identity formation (Froese and Izquierdo Citation2018).

Identity is embodied, enacted, and felt by the bodymind through “explicit and implicit relationships to sensation, movement, and physiological processes”—it is changeable, multimodal, and situational (Caldwell Citation2016, 228). It is through autobiographical memories that individuals’ sense of (multiple) identities is formed in the bodyminded being, through combining past and present selves (Addis and Tippett Citation2004) in a continuous embodied process (Gallien Citation2020). Identity emerges as embodied and multiple, which facilitates individuals’ modes of being-in-the-world—thus becoming a mode of embodied epistemology and embodied ontological positioning.

However, identity and its embodiment are key sites/sights of hegemonic regulation and a locus of social control. Bodies are co-opted into this net of hegemonic social relations where some bodies are privileged over others. Marginalized bodies become limited in their engagement in the world and the ways in which they move in and through the world (Caldwell and Leighton Citation2018), impacting ontological positioning, identity, and embodiment. Tied to bodies are modes of knowledge, knowing, and knowledge creation (epistemology). In the privileging of bodies, certain epistemologies and modes of knowing and being in the world are also privileged. The privileged body with related epistemologies reflects a dominant locus of enunciation.

Thus, a locus of enunciation can also be embodied within an identity. Engaging with embodied, autobiographical memories can allow for navigating identity, epistemology, and ontology through the bodyminded being. Engaging with embodied autobiographical memories foregrounds the sensual, imaginative, and intuitive knowledge of personal experiences (Fujino, Gomez, and Lezra et al. Citation2018) and embodied knowledge, which could provide possibilities for alternative ways of knowing, being, and doing, through decolonial storying.

Embodied Decolonial Storying

Embodied decolonial storying positions participants at the center of the choreographic process, challenging the colonial order, articulating their worlds, understanding their knowledge systems, naming their experiences, and identifying themselves in relation to being in the world (Archibald, Xiiem, and Lee-Morgan et al. Citation2019). Decolonial storying facilitates individuals’ processes of becoming because it is “subjective and emotional and embodied” (Donelson Citation2018, 73). The characteristics of subjectivity, emotion, and embodiment are linked to storying. Arguably, what makes storying decolonial is the decolonial practice of how everyone’s “right to be” is acknowledged and invited into the process of storying. Storying is embodied as the story emerges and communicates through, in, and with the bodyminded being, and space is available for these storyings to be heard and acknowledged. Embodied decolonial storying as a method is a form of activism against coloniality, the coloniality of being, and the colonial matrix of power (Donelson Citation2018).

The choreographic process toward Memoryscapes (2022) aimed to facilitate an embodied decolonial storying that validates and acknowledges a plurality of perspectives and aesthetics, encouraging pluriversality, creating a reflective and reflexive space for becoming through interweaving epistemology and ontology. Positioning storying as a means of giving value to individuals’ lived experiences, autobiographical memories, and individuals’ multiple cultural identities creates a space for a decolonial praxis. The multiple cultural identities performed draw from cultural movement patterns, legitimizing previously marginalized dance aesthetics. To frame this decolonial praxis in the creation of Memoryscapes (2022), we briefly explain the approach to the research.

Approach to the Research

We are white middle-class South African women scholar-practitioners working in the South African higher education context and the performing arts profession. Teaching as previously privileged individuals in a multicultural context requires ongoing self-reflection in relation to the privileges that our history and the epistemological hegemony in South African education have afforded us. Thus, our identities are shaped by historical and cultural power and privilege, as well as being the locus of enunciation we critique.

As we are working in a multicultural and racially diverse educational context, we aim to support our student bodies as decolonial allies: acknowledging and taking responsibility for our overt and covert complicity in oppression and joining in solidarity with historically disadvantaged groups (Ohberg Citation2016). Being an ally is “an endless unfolding struggle for equity … one cannot be an ally but are always becoming one” (Bishop Citation2015, 103). The ethics of voluntarily positioning ourselves as decolonial allies is driven by our commitment to reduce prejudice and discrimination (LeMaire, Miller, and Skerven et al. Citation2020), by inviting cultural differences into the creative space and drawing from the textured memories of dancers as co-creators. This commitment requires continuous critical self-reflection, accountability, and delegitimizing power positions. This research is one attempt at decolonial allyship.

This qualitative research employed an interpretivist paradigm to capture the subjective experiences, responses, and embodied musings of the participants in the choreographic process toward the creation of Memoryscapes (2022). We took a phenomenographical approach to the research in which we engaged with the participants’ accounts of their experiences and the data collected on how they perceive and conceptualize their worlds (Cibangu and Hepworth Citation2016). We observed and we engaged collaboratively with each other and/or the participants in encouraging storying embodied, autobiographical memories and reflexive engagement with the choreographic process. The data production and collection strategies included creative movement tasks, moving, journaling, painting, writing, reflections, and focus group discussions.

Author 1 facilitated the practical process related to the research as part of the choreographic process as a collaborator with the other participants in an intersubjective engagement (Leigh and Brown Citation2021). There was a continual emphasis on researcher reflexivity as an ongoing, multimodal process, where critical attention was paid to subjectivity and an acknowledgment of the social construction of being-in-the-world. Authors 2 and 3 acted as critical friends who offer critique on research by questioning and offering various entry points into research or another perspective from which to examine the research (MacPhail, Tannehill, and Ataman Citation2021).

Memoryscapes

Memoryscapes (2022) was a choreographic product resulting from a process that explored decolonial strategies (Haskins Citation2023). provides an image from the production Memoryscapes (2022). The choreographic process toward Memoryscapes (2022) used a net of decolonial strategies through decolonial storying of autobiographical, embodied memories as a methodological praxis toward epistemological disobedience and delinking. Decolonial scholars often use specific strategies to foreground collaborative, communicative, embodied, participatory, and reflective pedagogical practices. These decolonial pedagogies centralize the notions of relationality, multiplicity, holism, and mutuality as “catalysts for counter-hegemonic thought” (Teasley and Butler Citation2020, 2). The net of strategies, processes, specific choreographic tasks and devices, decided before by us as researchers, provided the basic outline for the choreographic process as starting points or invitations into the explorations. The participants’ input in the process allowed for the flexibility to shift in accordance with what they offered. provides the biographical information of participants involved in the choreographic process.

Table 1. Biographical information of participants involved in the process.

The choreographic processes involved 13 participants as the source of creative choreographic knowledge making in unraveling, reconstructing, counter/storying, and reclaiming their autobiographical, embodied memories, personal histories, and identities as they recalled, remembered, and (re)moved. The participants are all currently studying at the same higher educational institute in a dance program, where they focus on various dance techniques and genres. Through engaging with the decolonial strategies, participants excavated their embodied, autobiographical memories tied to their lived experiences and multiple cultural encounters to create movement material that reflects the meshwork of their being in the world. In doing so, both a journey toward a decolonial educational path and an ontology that foregrounds a monist sense of self were a possibility for navigation. A monist sense of self strengthens the idea of a pluriverse, where various life worlds/mental models are honored within a communicable activity.

Choreographic Process

Below, we detail aspects of the 12 collaborative choreographic processes over eight days, where participants’ embodied memories were invited into the creative space and shaped toward performance. We do not discuss each of the 12 processes in detail but focus on key aspects. The choreographic process in this research was not part of the curricula per se due to ethical concerns; however, the choreographic process did reveal the potential for inclusion in future curricula. Ethical clearance was obtained from the relevant higher educational institution. Each of the 12 processes took about five hours. Participation was voluntary, and participants could withdraw at any time. Additionally, all participants consented to the inclusion of their voices and images in publications. The choreographic processes and compositional devices were not fixed, and the process was open to unfold in multiple and fluid ways, allowing for shifts, ruminations, re-ordering, re-forming, re-storying, and re-moving. Participants generated fragments and traces of movements, phrases, or motifs. Specific motifs or traces of movement reflected fragments of memory of the participants’ subjective, lived reality. Each compositional method was an invitation, a longing, and a sketchpad for unraveling memories and re-storying memories into being through movement.

At the start of the first session, participants were invited to reflect on what constitutes a safe space for the process and how it can be generated. provides the contract that was created for the choreographic process where a safe space was agreed on.

Each choreographic process was broken down into four parts: Part 1: to move, Part 2: to draw, to paint, to write, to consider motifs, Part 3: to create, and Part 4: to consider … to possibly emerge. Each exploration within the choreographic process had a specific theme associated with the exploration that allows for the process of accessing embodied, autobiographical memories as a stimulus for movement creation. Participants could reflect in their journals or through their paintings on their experiences and the process at any time during each session. The discussion below demonstrates how these processes unfolded and what emerged for participants to surface the decolonial potential within this proposed pedagogical approach. Each process functioned as a possible pathway toward delinking and epistemological disobedience in the context of higher education.

Process

Process 1: Naming Me

Naming me draws on Smith’s (Citation1999) work on decoloniality as a strategy of deconstruction and reconstruction, and that Chilisa (Citation2012) positions in an African context as “unraveling” and “reconstruction.” Participants question, reembody, re-look, and examine their ontological positions, sociocultural contexts, and identity constructs to re-discover, re-imagine, re-do, re-know, and re-sense their being in the world from their frames of reference. Names and naming form a part of individuals’ ontological positions and identities that assist in developing a sense of self (Hendrick Citation2015). Within the South African context, individual names are part of family histories and often reflect cultural imaginings. The naming of children is culturally significant within an African context, as names carry with them a predetermined sense of being-in-the-world. For example, Makhubedu (Citation2009) states that personality traits and prospects are often embedded in a name.

Participants were asked to navigate their names’ stories, meanings, significance of, and feelings about. Participants engaged with questions such as: How did you get your name, and does it have a specific cultural context? Who named you and what is the significance? Reflect on your name and how does it affect who you are today? If you had a different name, would that impact who you are or the many selves you are today? What felt sensations do you experience in this telling?

Based on the above as source material for movement creation, participants danced their name-stories. Further, each participant danced their story of their name for the group, while their partner narrated what they remembered of what the dancing partner had said regarding their name. Following this, participants shared their own name-stories, and witnessed and responded to others’ name-stories in an improvisational ensemble exploration where they danced their name-stories, entering and exiting the group at will. The processes allowed for a collaborative sharing—an honoring of, and appreciation for, the participants—their own sense of “selves” as their stories were brought into the creative space.

Participant 3 stated: My name is engraved and mapped into my body. My name is in/on and under my skin … it is me.

Participant 2 stated: I always go to my name, anytime I want to remind myself who I am or where I come from. I am my name. I have many parts that make me who I am and that is in my name.

Remembering and naming is a process toward reclaiming “languages, spaces, and identities” and serves as a decolonial strategy to position individuals within their worlds (Zavala Citation2016, 4). The process of naming, through remembering, involves naming or defining social and cultural worlds through dialogue. A “with-ness” (Hogg, Stockbridge, and Achieng-Everson et al. Citation2021, 15) or sense of conviviality emerged where different histories and multiple cultures existed in the space. This conviviality was evidenced in participants witnessing and attentively listening to the ideas, stories, memories, and feelings of others, as well as their responses through movement in the group improvisation.

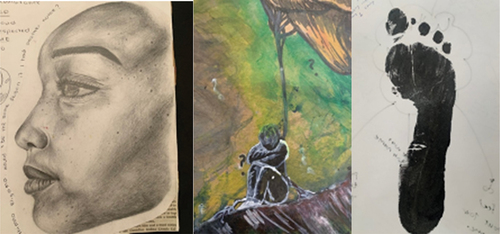

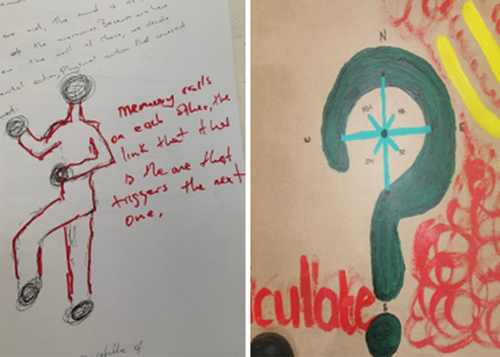

Naming me arguably was a discovery of what memory theorist Shaw (Citation2016) refers to as individual “you-ness;” a rediscovery and recovery process (Laenui Citation2000) of unraveling individual perceptions, sociocultural contexts, and subjective lived experiences (Chilisa Citation2012). Embodied data emerged as “unconscious information brought to consciousness by attending to oneself in the present moment” (Tantia Citation2020, 40) through exploring felt senses of their names. Naming me invited participants to explore multiple aspects of, if not multiple, identities, and what part their name plays in their conception of self and their personal histories as related to their sociocultural contexts. This brings to the fore notions of hybridity as multiple identities intertwine and collude—within each participant and as a collective. provides participants’ reflective paintings and drawings on Naming me.

Processes 2 and 3: Inviting Personal Histories and Bodystories into the Room

Inviting personal histories and bodystories into the room draw on Chilisa’s (Citation2012) strategy of communicating from one’s own frame of reference—to foreground personal, subjective lived experiences and indigenous, embodied knowledges; Zavala’s (Citation2016) notion of counter/storytelling to re-remember how meaning is given to experiences, and to restorying and reclaiming such meanings. Lastly, Gallien (Citation2020) suggests redefining knowledge from an embodied perspective. Embodied perspectives are a form of “embodied data … living sources of knowledge” that allow personal information and memories (Tantia Citation2020, 40) through and within bodyminds.

Participants explored their own habitual movement choices and patterns toward revealing their “moving identity” (Roche Citation2011, 105). A moving identity is a signature way of moving or a movement heritage that manifests as an intertwining of past movement experiences, codified techniques learned, and cultural practices as the bodyminded beings’ experiences in movement reveal their sense of “selves.” Participants were asked to improvise for an extended period to notice their movement and spatial dynamics. Participants engaged with questions such as: What does your movement reveal about yourself? What stories does your body tell? What types of feelings, sensations, and thoughts emerge? What is the rhythm of your blood and bones? What memories, if any, emerge?

Participants then moved their responses to reveal their embodiment of self/ves. They were asked to capture what they perceive as their personal embodied selves in a movement phrase, noting cultural entanglements. They performed these movement motifs for each other, inviting reflections on what they perceived as each other’s movement habits, preferences, divergences from habitual ways of moving and their dance training, as well as possible cultural entanglements. As participants moved in time and space, the idea of a layered, historically formed body emerged that is intertwined with procedural memory and body memory, where gestures are revealed as idiosyncratic images of thought, with subjective, relational construction in motion.

When individuals move or dance in time and space, they reveal their lived experiences, identities, mental models, procedural body memory, habitual patterning, and habitual body memory. Their movements, gestures, and choices reveal their embodied experiences, memories, and their sense of their selves. The bodyminded being moving in time and space is interwoven with past experiences and tacit body knowledge, and in a sense, individuals’ personal “histories” are revealed. The multimodal bodyminded being becomes a meshwork of a “sensori-emotional-aesthetic amalgam of experience” (Tantia Citation2020, xxx).

As a reflective exploration, participants could paint or journal their responses to the movement explorations. provides participants’ reflective paintings and drawings on inviting personal histories and bodystories into the room.

Participant 2 stated: Traces of my body, traces of my past … constantly moving.

Participant 11 stated: My body remembers scars, pain, and bruises.

Participant 1 stated: What is forgotten triggers one memory into another.

Participant 8 stated: My skin shows my past; what I have experienced.

Participant 7 stated: Scars are memories, they might define what you have passed through. My past in the now.

Figure 5. Participants’ reflective paintings and drawings on inviting personal histories and bodystories into the room.

The processes positioned the choreographic method as movement, identity, culture, indigenous knowing, and heritage. In engaging with the explorations, bodyminded beings began remembering what they had forgotten to remember, moving from subconscious to conscious exploration. Through consciously moving and navigating familiar movement patterns and shifting them, the mover brings to awareness these patterns, as well as the reflective engagement on these patterns.

Recognition and relationality surfaced through intertwinings of various moving identities. Participants uncovered, rediscovered, and recovered their moving identity, habitual body memory, and the habitual “home base” of their bodyminded beings. The participants’ preferences in movement facilitated a “rethinking of thinking” (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2017) about what movements were imposed on their body as codified techniques and the effect of formal training, as well as what movements resided in their bodyminded being from their specific cultural practices, encounters, and sociocultural contexts.

Movement became a continuing site of self-recognition (Martin Citation2005) and a way into the embodied self “as a site of meaning-making and, indeed, storytelling” (Loots Citation2016, 377). This brought to the fore the ways identities are constructed, how individuals are shaped and storied by multiple factors. Further, the notion of the self and identity as “construct” implies possibilities for unmaking and re-making—for change with the notion of agency in identity construction.

Process 4: Myself as Dream

Myself as Dream is based on Laenui’s (Citation2000) idea of dreaming as a decolonial strategy. Dreaming allows the possibility of a re-shaping, re-making, and re-configuration of the construct of reality as impacted by coloniality. This possible alternative way of seeing, being, knowing, and doing allows for a critical reflection on internalized beliefs about how you belong to the social world. The body emerges as “the existential ground of culture” (Csordas Citation1990, 5) and the embodiment of culture and social beliefs (Cancienne and Snowber Citation2003).

Participants were asked to consider and describe, in their own language, their gender, culture, sexuality, and race. They allowed a succession of images, sensations, and emotions to emerge. They then “moved” these identity markers and explored how their bodies responded. Participants engaged with questions such as: Who are you within your body? How does your gender and sexuality affect who you are? Participants were also asked to revisit a specific autobiographical memory based on a cultural practice to explore how their culture might assist in shaping their being-in-the-world. Then, participants engaged with questions such as: What does your culture mean to who you are? How does culture relate to the experiences of your body?

Participants engaged in a phase of dreaming (dreaming as a series of thoughts, images, sensations, and emotions) where they considered rites of passage, rituals, and ceremonies. The participants’ cultural practices revealed a communal aspect with a spiritual connection that spoke to an Afrocentric epistemology. Through these explorations, participants started to reveal their “selves as dream” through a movement phrase.

Participant 2 stated: I have been paid for … I am the dream of slaves. I am a free, Black, Xhosa woman.

Participant 7 stated: I remember people would call me imoffie, I am committing a sin, God does not want me … He then described how he felt when he started dancing: I remember finding myself in the flow of movement, at times I would act straight … figures gliding along the flow of the stage … moved by the energies that penetrated my muscles … I was free to be me, my gender did not define me …

Participant 1 stated: You can’t pass by when we are building a home, help us build a home.

Participant 2 further stated: All these ceremonies, they are more than that, its spiritual; people express how they really feel. It’s a way of interlinking all of us.

Participants’ reflections reference an Afrocentric worldview where three core values surfaced: a worldview that includes communality, collectivity, and spirituality (Ntseane Citation2011). These values position humans as part of the totality of life and an interconnection of humanity, foregrounding holism. This experience of holism differs significantly from the education system. Participants are embedded in a system that centers on individual achievement and competition within an epistemological hierarchy. The explorations positioned participants’ indigenous knowledges as valid modes of knowledge creation. The explorations also positioned the embodied responses to such knowledges as valid modes of knowledge-creation in a broader context of creating epistemological diversity.

The dreaming process then went deeper into memories of home. Recalling and remembering home “is instrumental in negotiating one’s sense of belonging, identity and self-construal as it entails an exploration of the self, the personal past and one’s relationship to home” (Marschall Citation2017, 3). Participants were asked to revisit a specific autobiographical memory about the place where they grew up. Participants engaged with questions such as: How did the home you grew up in influence who you are today? What are the feelings and sensations when recalling your home?

Participant 7 stated: My body remembers the feeling of this place. My home is where I belong.

Participant 10 stated: I remember that home wasn’t a place but a person.

Participants rediscovered their lived experiences, thinking, and feelings around home and place in relation to the epistemic validation of the prior explorations. Dreaming intertwined with remembering allows a space for re-imagining and re-manifesting autobiographic memories in a mediated manner that allows the constructedness of social realities to come to the fore. This, in turn, indicates personal and collective agency, rooted in embodied knowledges, in affecting change.

Process 5: Sensing You, Shaping Me

Sensing you, shaping me is based on moving from sense memory and Gallien’s (Citation2020) notion of redefining knowledge from an embodied perspective. Individuals perceive the world subjectively through their senses and sensorimotor systems, and that information is interpreted as their perception of the world. The “memory of knowledge lies in your senses,” and these nuances of knowing are embodied (Snowber Citation2016, 8). How participants perceive, feel, and think, relates to their identities (Fuchs Citation2020). Using sense memory as a compositional device for movement is a way to tap into the “knowing body” that interprets, senses, and understands (Marlin-Bennett Citation2013).

Participants were asked to find a partner and to start by touching each other’s faces. With that tactile memory in “mind,” they traced the person’s face in the space around them. Further, participants created duets with interpretations of each other’s faces. Then, participants generated a movement phrase that embodied their interpretation and sensations of their own face. Participants engaged with questions such as: What was the sensory experience of your partner’s face? What were the textures and feelings of your own skin? What connections can you find between these skins? How did you create movement from this experience?

Participant 12 stated: I started to dance like him after touching his face; I embodied him … imagine moving on his face, a landscape.

Participant 8 stated: My face is a part of me, my contours define me.

Participants considered another person’s face, as well as their own face, interpreting, sensing, and perceiving through a phase of rediscovery and recovery. They used a tactile source for movement creation through sensing and perceiving, connecting inner and outer, and with a body-absorbed perception. A sense of kinesthetic empathy emerged as they sensed the facial cartography of the other participant with respect and empathy.

Process 6-12: Selving

Selving involves various explorations of “selving,” shaping, sensing, moving memories, manifesting me, witnessing you, reflecting me, shaping time and space toward finally choosing self. Participants selected the specific autobiographical memory or the memoryscape (a combination or scape of memories and traces) that forms the tapestry and embodied narrative of their autobiographical solo. Participants wrote and recorded the text that would accompany their danced solo. They took agency in making decisions about their solo, considered the overall form and shape of their choreography, as well as making choices about what would be a part of their solo: movement vocabulary, choreographic exploration, sound, scenic devices, and any other elements.

Process 9: Witnessing You, Reflecting Me

Witnessing you, reflecting me is based on Laenui’s (Citation2000) decolonial strategy of rediscovery and recovery. The aim of the process was to witness a partner’s solo and reflect it back to them through their bodyminded being. This witnessing allows for possible re-organizations, re-reflections, and re-creations of the movement material for their solos. The witness pays attention by being “deeply observant” (Musicant Citation2001, 25). In being deeply observant, the witness enters into multiple relationships at once—“a relationship with the other person; a relationship with their own body in the present moment; and a relationship with their own assumptions, expectations, and experiences” (Hess Citation2018, 17). Thus, the witness brings their total bodyminded being and attention to the mover. Thereafter, the witness then dances their perception and interpretation of the autobiographical memory and movement language back to the mover. A space could emerge for new perspectives or possibilities.

Participant 4 stated: I am overwhelmed by their interpretation; it’s almost as if we had a connection to one another.

The process of shifting, shaping, and making occurred where all the autobiographical solos were interwoven to create Memoryscapes (2022). The participants improvised how one solo would flow into another to create the structure of the work. Engaging with others in relationship to individual embodied memories allows for collaboration and a sense of being a collective. Participants engaged with the choreographic process eliciting their own histories, memories, and lived experiences that were “written on the embodied self” and embedded in the bodyminded being (Loots Citation2016, 380). The embodied experience is navigated as participants articulate memories in the body and understand the moment of remembering through the body: an embodied re-membering. reveals a participant dancing his memoryscape.

As participants moved their memories, they “performed their selves” in the choreographic context, which includes identity and cognizance of the sociocultural context of their ontologies. This complex, embodied, bodyminded being, with a unique history, memory, perception, sociocultural lens, and identities, in the process of becoming, was the space for embodied decolonial storying (Budgeon Citation2003), providing a sense of epistemic disobedience and delinking toward decoloniality.

This choreographic process surfaces a net of possible methodological praxes toward decoloniality in the teaching and learning space. Against the backdrop of these decolonial options, and with a particular focus on the dimensions of “story” and “embodiment,” we argue that using autobiographical memories for movement creation allows for participants to engage deeply with identity constructs through embodied decolonial storying.

Reflections

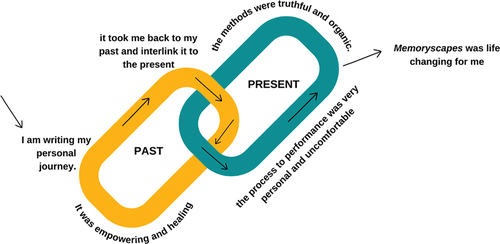

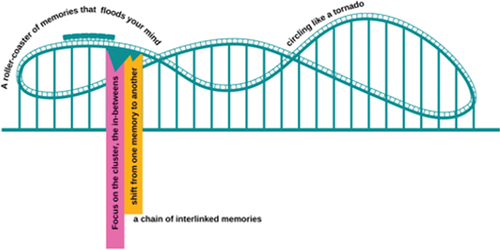

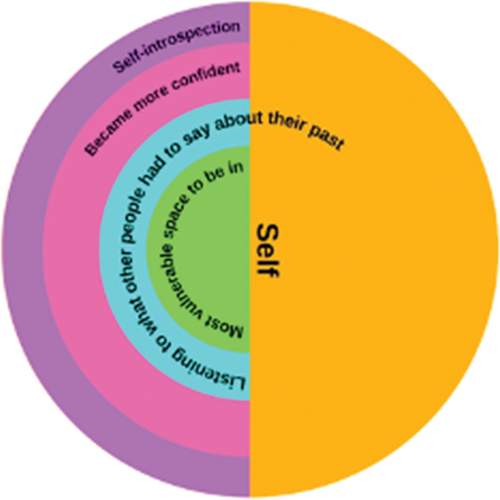

Through the choreographic process of memoryscapes, participants “tuned into” their embodied, autobiographical memories and navigated ways to explore them through movement: a recalling to moving. In moving these embodied memories, they navigated their multimodal bodyminded being in time and space and engaged in a re-reflection process of the past in the present. Participant 2ʹs reflective cartographic statement is provided in .

The memoryscapes choreographic process emerges as an uncovering and rediscovery process where sensations, feelings, and remembering are intertwined. Through accessing participants’ embodied memories, stories emerge and become source material for the choreographic compositional works expressed through movement. Participant 1ʹs reflective cartographic statement is shared in .

In recalling these embodied memories, participants became “explorers” reconfiguring their memories through a reflection and discussion of experiences that held meaning for them. The process of re-reflecting offered them a different entry point to viewing and engaging in embodied memories. The process provided another perspective, a re-looking toward understanding their embodied memories and how the memories relate to their being-in-the-world as a shape-shifting of identities-in-becoming.

The participants’ embodied memories were moved into being. Simultaneously, participants were “moved” by their feelings, sensations, and embodied memories in a continuous motion in time and space, existing in a fleeting moment. In that transitory moment of moving memories, a locus of enunciation was created for them to experience a congruence of their social cartography of selves with others (Goodson Citation1995) as their life worlds aligned. Participant 8ʹs reflective cartographic statement can be witnessed in .

The authors use a collective decolonial viewpoint to argue that this new locus of enunciation (expressions of pluriversal knowledges, ways of being and doing) allows an ecology of knowledges and ontologies. The new ecology can be referred to as the loci (the plural) of enunciations as it moves toward plurality, multiplicity, and pluriversalities. The enunciations shift and localize the claims from the West and re-conceptualize what the center is (Figueiredo and Martinez Citation2021). Shifting the locus of enunciation in curricula could contribute to fracturing epistemic systems and decolonizing scholarly knowledge (Figueiredo and Martinez Citation2021).

The potential to shift, if not rupture, the locus of enunciation allows ways of being in the world to emerge that are multiple, fluid, and pluriversal. This pluriversality within an educational context can allow a “mosaic epistemology” where various knowledges interweave (Connell Citation2018, 404), which is vital in a multicultural, multilingual and multiracial South African context. Decolonial higher education offers this possibility, which is an alternative to Western modes of thinking, being, and knowing.

Conclusion

Through embodied, decolonial storying, students are positioned within the educational context as “subjects of their own destiny and are able to re-invent the past and envision their own future” (Mudimbe Citation1985, 216). Students become the knowledge “producers” in the choreographic context as they draw from their embodied memories for their own choreographies.

By incorporating embodied, autobiographical memories through decolonial storying as methodological praxis in relation to the above decolonial strategies, possibilities are created for finding alternative ways of engaging in/with the world—ontologically, epistemologically, culturally, and philosophically. Accessing embodied, autobiographical memories through decolonial storying moves toward shifting the locus of enunciation in choreographic composition to loci of enunciation. The students become the loci of enunciation by drawing from their subjective lived experiences, memories, and personal stories, revealing how they have constructed their identity and their relationality to the ontological worlding and epistemological diversity of fellow students. The students do this through embodiment via embodied, autobiographical memories, as the students story their embodied worlds as knowledge, revealing their multiple identities: a decolonial storying of moving memories.

By facilitating choreographic pedagogy where students “are,” the curricula worked to shift Eurocentric, Western ways of knowing and being-doing. Centering embodied and indigenous knowledge in the higher education context allows students to reflect on the teaching and learning process. The students can find their sense of agency in the production of knowledge by opening their lenses in their processes of becoming. The students’ processes of becoming are facilitated through holistic, inclusive, communicative, critical thinking, and embodied learning, within the choreographic context. The choreographic process created a space where “times past meet the immediacy of time present within and on the surface of the body” (Bannerman Citation2010, 479). In this space, there was a co-existence of time and space through/in/on the bodyminded being, and a temporality of becoming(s). Embodied decolonial storying functions as a form of epistemological disobedience and delinking toward encouraging educators in a higher educational context to integrate students embodied memories into the curriculum and create a space that recognizes students’ multiple and diverse identities.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Addis, Donna Rose, and Lynette J. Tippett. 2004. “Memory of Myself: Autobiographical Memory and Identity in Alzheimer’s Disease.” Memory 12 (1): 56–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210244000423.

- Anderson, Maria Cynthia. 2021. “Rethinking Dance in Higher Education.” PhD diss., University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/123221.

- Angu, Pineteh E. 2018. “Disrupting Western Epistemic Hegemony in South African Universities: Curriculum Decolonization, Social Justice, and Agency in Post-Apartheid South Africa.” International Journal of Learner Diversity and Identities 25 (1–2): 9–22. https://doi.org/10.18848/2327-0128/CGP/v25i01/9-22.

- Archibald, Jo-ann, Q’um Q’um Xiiem, Jenny Bol Jun Lee-Morgan, and Jason De Santolo, eds. 2019. Decolonizing Research: Indigenous Storywork as Methodology. London: Zed Books.

- Ball, Christopher. 2010. “From Diaries to Brain Scans: Methodological Developments in the Investigation of Autobiographical Memory.” In The Act of Remembering: Toward an Understanding of How We Recall the Past, edited by John H. Mace, 11–40. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Bannerman, Henrietta. 2010. “Choreographers’ Reflexive Writing–A Very Special Practice.” Forum for Modern Language Studies 46 (4): 474–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/fmls/cqq017.

- Bishop, Anne. 2015. Becoming an Ally: Breaking the Cycle of Oppression in People. 3rd ed. Winnipeg, Canada: Fernwood Publishing.

- Bluck, Susan, and Tilmann Habermas. 2001. “Extending the Study of Autobiographical Memory: Thinking Back about Life across the Life Span.” Review of General Psychology 5 (2): 135–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.135.

- Brown, Warren S. 2017. “Knowing Ourselves as Embodied, Embedded, and Relationally Extended.” Zygon 52 (3): 864–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/zygo.12347.

- Budgeon, Shelley. 2003. “Identity as an Embodied Event.” Body & Society 9 (1): 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X030091003.

- Caldwell, Christine M. 2016. “Body Identity Development: Definitions and Discussions.” Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy 11 (4): 220–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2016.1145141.

- Caldwell, Christine, and Lucia Bennett Leighton, eds. 2018. Oppression and the Body: Roots, Resistance, and Resolutions. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

- Cancienne, Mary, and Celeste Snowber. 2003. “Writing Rhythm: Movement as Method.” Qualitative Inquiry 9 (2): 237–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800402250956.

- Chilisa, Bagele. 2012. Indigenous Research Methodologies. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Cibangu, Sylvain K., and Mark Hepworth. 2016. “The Uses of Phenomenology and Phenomenography: A Critical Review.” Library and Information Science Research 38 (2): 148–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2016.05.001.

- Comaroff, Jean, and John L. Comaroff. 2012. Theory from the South: Or, How Euro-America Is Evolving toward Africa. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

- Connell, Raewyn. 2018. “Decolonizing Sociology.” Contemporary Sociology 47 (4): 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094306118779811.

- Csordas, Thomas J. 1990. “Embodiment as a Paradigm for Anthropology.” Ethos 18 (1): 5–47. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.1990.18.1.02a00010.

- Donelson, Danielle E. 2018. “Theorizing a Settlers’ Approach to Decolonial Pedagogy: Storying as Methodologies, Humbled, Rhetorical Listening and Awareness of Embodiment.” PhD diss., Bowling Green State University. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/eng_diss/23/.

- Dreyer, Jaco S. 2017. “Practical Theology and the Call for the Decolonization of Higher Education in South Africa: Reflections and Proposals.” HTS Theological Studies 73 (4): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i4.4805.

- Dube, Nomzamo, and Florence R. Mudehwe-Gonhovi. 2022. “Humanising Pedagogy and International Students’ Adjustment at an Institution of Higher Learning in South Africa.” Journal of Educational Studies 21 (1): 147–66.

- Figueiredo, Eduardo H., and Juliana Martinez. 2021. “The Locus of Enunciation as a Way to Confront Epistemological Racism and Decolonize Scholarly Knowledge.” Applied Linguistics 42 (2): 355–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz061.

- Fomunyam, Kehdinga George. 2016. “Theorising Student Constructions of Quality Education in a South African University.” South African Review of Education 22 (1): 46–63.

- Fomunyam, Kehdinga George, and Damtew Teferra. 2017. “Curriculum Responsiveness within the Context of Decolonisation in South African Higher Education.” Perspectives in Education 35 (2): 196–207. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v35i2.15.

- Froese, Tom, and Eduardo J. Izquierdo. 2018. “A Dynamical Approach to the Phenomenology of Body Memory: Past Interactions Can Shape Present Capacities without Neuroplasticity.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 25 (7–8): 20–46.

- Fuchs, Thomas. 2020. “The Circularity of the Embodied Mind.” Frontiers in Psychology 11 (8): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01707.

- Fujino, Diane C., Jonathan D. Gomez, Esther Lezra, George Lipsitz, Jordan Mitchell, and James Fonesca. 2018. “A Transformative Pedagogy for A Decolonial World.” Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies 40 (2): 69–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2018.1442080.

- Gallien, Claire. 2020. “A Decolonial Turn in the Humanities.” Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, no. 40: 28–58.

- Goodson, Ivor. 1995. “Storying the Self: Life Politics and the Study of the Teacher’s Life and Work.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting at the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA, April 18-22.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2011. “Decolonizing Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political-Economy: Transmodernity, Decolonial Thinking, and Global Coloniality.” Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1 (1): 1–34. https://doi.org/10.5070/t411000004.

- Haskins, Nicola. 2023. “Decolonial Storying: Embodied Memory in Facilitating Choreographic Composition.” PhD diss., University of Pretoria, South Africa. https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/90579.

- Hendrick, Michael. 2015. “How Our Names Shape Our Identity.” The Week, January 8. https://theweek.com/articles/460056/how-names-shape-identity#.

- Hess, Kyra. 2018. “Witnessing Another, Witnessing Oneself.” Master’s thesis, Sarah Lawrence College. https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/dmt_etd/46/.

- Hogg, Linda, Kevin Stockbridge, Charlotte Achieng-Everson, and Suzanne Soohoo, eds. 2021. Pedagogies of With-Ness: Students, Teachers, Voice and Agency. Gorham, ME: Myers Education Press.

- Keet, André. 2014. “Epistemic ‘Othering’ and the Decolonisation of Knowledge.” Africa Insight 44 (1): 23–37.

- Koch, Sabine C., Thomas Fuchs, Michela Summa, and Cornelia Müller, eds. 2012. Body Memory, Metaphor and Movement. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins.

- Laenui, Poka. 2000. “Process of Decolonization.” In Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision, edited by Marie Battiste, 150–60. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Leach, Martin. 2018. “Psychophysical What? What Would It Mean to Say ‘There Is No “Body” … There Is No “Mind”’ in Dance Practice?” Research in Dance Education 19 (2): 113–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2018.1463361.

- Lebeloane, Lazarus Donald Mokula Oupa. 2018. “Decolonizing the School Curriculum for Equity and Social Justice in South Africa.” Koers 82 (3): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.19108/KOERS.82.3.2333.

- Leigh, Jennifer, and Nicole Brown. 2021. Embodied Inquiry: Research Methods. London: Bloomsbury.

- LeMaire, Kelly L., Melissa Miller, Kim Skerven, and Gabriela A. Nagy. 2020. “Allyship in the Academy.” Susan Bulkeley Butler Center for Leadership Excellence and ADVANCE Working Paper Series 3 (1): 6–26.

- Letsekha, Tebello. 2013. “Revisiting the Debate on the Africanisation of Higher Education: An Appeal for a Conceptual Shift.” The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning 8 (1): 5–18.

- Loots, Lliane. 2016. “The Autoethnographic Act of Choreography: Considering the Creative Process of Storytelling with and on the Performative Dancing Body and the Use of Verbatim Theatre Methods.” Critical Arts 30 (3): 376–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2016.1205323.

- MacPhail, Ann, Deborah Tannehill, and Rebecca Ataman. 2021. “The Role of the Critical Friend in Supporting and Enhancing Professional Learning and Development.” Professional Development in Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1879235.

- Makhubedu, Matsatsi Grace. 2009. “The Significance of Traditional Names among the Northern Sotho Speaking People Residing within the Greater Baphalaborwa Municipality in the Limpopo Province.” Master’s thesis, University of Limpopo.

- Maldonado-Torres, Nelson. 2007. “On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of a Concept.” Cultural Studies 21 (2–3): 240–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162548.

- Marlin-Bennett, Renée. 2013. “Embodied Information, Knowing Bodies, and Power.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 41 (3): 601–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829813486413.

- Marschall, Sabine, ed. 2017. Tourism and Memories of Home. Migrants, Displaced People, Exiles and Diasporic Communities. Bristol, UK: Channel View Publications.

- Martin, Randy. 2005. “Dance and Its Others.” In Of the Presence of the Body, edited by André Lepecki, 47–63. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- Mignolo, Walter D. 1999. “I Am Where I Think: Epistemology and the Colonial Difference.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 8 (2): 235–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569329909361962.

- Mignolo, Walter D. 2007. “Introduction: Coloniality of Power and de-Colonial Thinking.” Cultural Studies 21 (2–3): 155–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162498.

- Mignolo, Walter D. 2011. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Latin America Otherwise Languages, Empires, Nations Series Editors Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mignolo, Walter D., and Catherine E. Walsh. 2018. “On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis.” Perspectives on Politics 17 (3): 866–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1537592719001518.

- Molobye, Kamogelo. 2022. “Looking Back to Move Forward: Celebrating 20 Years of an Innovative Contemporary African Dance Company.” South African Theatre Journal 34 (2): 123–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10137548.2022.2050519.

- Motsaathebe, Gilbert. 2019. “The Rhetoric of Decolonisation in Higher Education in Africa: The Rhetoric of Decolonization in Higher Education in Africa: Muse, Prescriptions and Prognosis.” African Journal of Rhetoric 11 (1): 37–63.

- Mudimbe, Valentin Y. 1985. “African Gnosis Philosophy and the Order of Knowledge: An Introduction.” African Studies Review 28 (2–3): 149–233. https://doi.org/10.2307/524605.

- Musicant, Shira. 2001. “Authentic Movement: Clinical Considerations.” American Journal of Dance Therapy 23 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010728322515.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. 2013a. Empire, Global Coloniality and African Subjectivity. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. 2013b. Coloniality of Power in Postcolonial Africa: Myths of Decolonization. Dakar: Codesria.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. 2013c. “Why Decoloniality in the 21st Century?” The Thinker 48: 10–15.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. 2017. “The Emergence and Trajectories of Struggles for an ‘African University’: The Case of Unfinished Business of African Epistemic Decolonization.” Kronos 43 (1): 51–77. https://doi.org/10.17159/2309-9585/2017/v43a4.

- Ntseane, Peggy Gabo. 2011. “Culturally Sensitive Transformational Learning: Incorporating the Afrocentric Paradigm and African Feminism.” Adult Education Quarterly 61 (4): 307–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713610389781.

- Ohberg, Emilia. 2016. “Becoming an Ally: Beginning to Decolonize My Mind.” Master’s thesis, University of London. https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1049901/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Oliver, Erna, and Willem H. Oliver. 2017. “The Colonisation of South Africa: A Unique Case.” HTS Theological Studies 73: 3):1–8.

- Rani, Maxwell Xolani. 2018. “The Impact of Colonization on the Ability to Make a Meaning of ‘Black’ South African Contemporary Dance in the 21st Century.” Journal of Pan African Studies 12 (4): 31–326.

- Roche, Jenny. 2011. “Embodying Multiplicity: The Independent Contemporary Dancer’s Moving Identity.” Research in Dance Education 12 (2): 105–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2011.575222.

- Samuel, Gerard. M. 2016. “Dancing the Other in South Africa.” PhD diss., University of Cape Town. https://open.uct.ac.za/items/36ecdfb9-d420-42bb-9fb0-6c76900131ac.

- Shaw, Julia. 2016. The Memory Illusion: Remembering, Forgetting, and the Science of False Memory. London: Random House Books.

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. New York: Zed Books.

- Snowber, Celeste. 2016. Embodied Inquiry: Writing, Living and Being Through the Body. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-755-9.

- Tantia, Jennifer Frank. 2020. The Art and Science of Embodied Research Design: Concepts, Methods and Cases. London: Routledge.

- Teasley, Cathryn, and Alana Butler. 2020. “Intersecting Critical Pedagogies to Counter Coloniality.” In The SAGE Handbook of Critical Pedagogies, edited by R. Steinberg Shirley and Barry Down, 186–204. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526486455.n26.

- Wa Thiong’o, Ngūgĩ. 1986. Decolonizing the Mind. Nairobi: East African Education Publisher.

- Yoon-Ramirez, Injeong, and Benjamin Ramirez. 2021. “Unsettling Settler Colonial Feelings Through Contemporary Indigenous Art Practice.” Studies in Art Education 62 (2): 114–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2021.1896416.

- Zavala, Miguel. 2016. “Decolonial Methodologies in Education.” In Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, edited by A. Peters Michael, 1–6. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_498-1.