ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to return to Freud’s original descriptions of the primary and secondary processes in the light of modern neurosciences. In his Project for a Scientific Psychology, Freud draws the axes of the architecture of a mental apparatus: on a horizontal plane, the primary process transfers the excitation by impinging stimuli over a sequence of analogous states towards their discharge; thus, the primary process is essentially characterized by its associative tendency. On a vertical plane, the secondary process opposes the primary bottom-up pressure by a top-down inhibition with its origins in the purposive idea: the secondary process is essentially characterized by its inhibitory interventions. Freud later proposed that the primary and secondary process are seeking for perceptual, respectively thought identity. These different elements are coherent with the dynamics of the ventral and dorsal brain pathways respectively. Moreover, the dorsal pathway has an inhibitory influence upon the ventral pathway, much like the secondary has upon the primary. This influence is exerted thanks to what Freud called the “indications of reality.” We propose to equate these indications with the efference copies in modern neurosciences since they proceed from the same physiology and have the same function, besides originating from the same Helmholtzian source. Finally, even if both primary and secondary processes serve the death drive through the pleasure and the reality principle respectively, only the secondary process, requiring the bearing of an accumulation of excitations, also serves the life drive.

Introduction

The Freudian primary and secondary processes are a crucial couple of concepts in psychoanalytic theory (see e.g. Klein, Citation1967, p. 130; Jones, Citation1953, p. 389). They form the fundamental axes of the mental apparatus and Freud (Citation1895) had concluded that “all the functions of the nervous system can be comprised under the aspect of the primary and the secondary functions” (p. 297). They have been elaborated upon by a wide variety of psychoanalytic scholars including Rapaport (Citation1951), Lacan (Feldstein et al., Citation1994), Holt (Citation2002, Citation2009) and Shevrin (Citation1973) and proved relevant for clinical understanding. For example, Bergeret (Citation1974) described a personality in terms of a “rather invariant reciprocal play of the primary and secondary processes” (p. 46). Moreover, they lend themselves to interdisciplinary dialogue and to measurement in a variety of ways – such as Holt’s (Citation2009) “Primary Process System” and the GeoCat instrument (Bazan & Brakel, Citation2023).

The purpose of the present study is to return to Freud’s original descriptions in the light of modern neurosciences. Indeed, before pressing on to psychological and phenomenological descriptions, Freud, starting in the Project for a scientific psychology (Citation1895), details a minute, mechanical and logical description of these processes, in line both with the neurology of his time and with his clinical experience. Without a clear understanding of the underlying rationale for these mental processes, we may easily start to build upon unprecise, or even faulty, phenomenological descriptions, thereby losing the means to make sense with adjacent scientific disciplines. For example, almost all psychoanalytic dictionaries present the primary/secondary process dichotomy as a parallel of the Unconscious (Ucs)/Conscious (Cs) dichotomy. However, as will be shown, the essence of the primary/secondary process distinction is not its topical location, and both primary and secondary process mentation can be conscious and unconscious. Thereby, this is a confusing parallel and hinders a productive interdisciplinary dialogue. However, the stakes of such a dialogue are high as this couple of processes appear as a generative bridge between metapsychology, cognitive neurosciences and clinical theory.

Freud’s neuronal theory in the project (1895)

Freud (Citation1895) starts by proposing that when an external quantity Q arrives on its irritable surface, “cellular structures (…) receive the exogenous stimulus in their stead. These ‘nerve-ending apparatuses’ (…) damp them down” (p. 306). Only quotients, Qη, of an intercellular order of magnitude will pass in the system. But still, following the “principle of inertia,” neurones tend to divest themselves of all quantities: a primary nervous system will give off the acquired Qη to the muscular mechanism through a reflex movement and “this discharge represents the primary function of the nervous system” and for this function, “among the paths of discharge those are preferred and retained which involve a cessation of this stimulus;” this is called the “flight from the stimulus” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 296; italics added). For example, a beam of light will lead the organism to flee the light source. The primary function, which is the essence of the primary process, is a defensive one: the discharge of excess stimulation. But so is the secondary process: “one of the earliest and most important functions of the mental apparatus is to ‘bind’ the [drive] impulses which impinge on it, to replace the primary process prevailing in them by the secondary process and to convert their mobile cathectic energy into a predominantly quiescent (tonic) cathexis”Footnote1 (Freud, Citation1920, p. 85). In the secondary process, the excitations are bound; that is, taken up in some sort of storage whereby this excitation is not readily discharged – be this binding the build-up of an action potential in singular neurones, the circulation of excitations between connected nodes (see further) or into tonic discharge rhythms (now called oscillations).

Indeed, with increasing complexity of the interior of the organism, the nervous system also receives endogenous stimuli. Shortage threats, such thirst and hunger, give rise to excess stimulation which has equally to be discharged. But “from these the organism cannot withdraw as it does from external stimuli (…). They can only cease subject to particular conditions, which must be realized in the external world. (Cf., for instance, the need for nourishment)” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 297). For example, one cannot flee from hunger, one cannot turn around to stop the thirst alarm, in the same way turning around would stop excess light stimulation. No, “the removal of the stimulus is only made possible here by an intervention which for the time being gets rid of the release of Qη in the interior of the body; and this intervention calls for an alteration in the external world (supply of nourishment, proximity of the sexual object), which, as a specific action, can only be brought about in definite ways” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 316). The organism must elaborate a step-by-step plan and execute it. To accomplish such a specific action, “an effort is required which is independent of endogenous Qη and in general greater, since the individual is being subjected to conditions which may be described as the exigencies of life” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 297; see also further). In consequence, the nervous system “must put up with (maintaining) a store of Qη sufficient to meet the demand for a specific action:” this is the secondary function “which calls for the accumulation of Qη” (Freud, Citation1895, pp. 297–298). “The regularly repeated reception of endogenous Qη in certain neurons (of the nucleus) and the facilitating effect proceeding thence (…) produce a group of neurons which is constantly cathected.” This organization is called the “ego” and “corresponds to the vehicle of the store required by the secondary function” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 323).

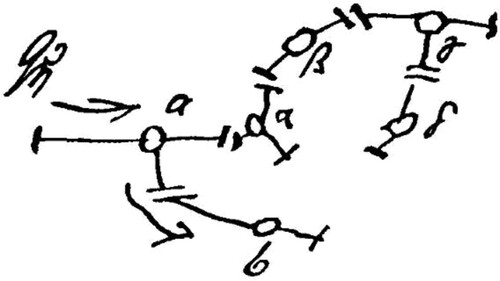

shows the difference between the primary and the secondary functioning of Freud’s neuronal apparatus. Say a Qη – for example, mother’s smell (an exogenous stimulus) – breaks into a neurone of the ego, neurone a. Freud then (Citation1895) proposes: “if it were uninfluenced, it would pass to neurone b” (p. 323). In other words, a current in the direction of the largest facilitation is set up. Freud understands this facilitation as a sensitization of the transmission of the signal from neurone to neurone – the nature of which could very well be incentive sensitization (Bliss & Lomo, Citation1973). The facilitated pathway is a primary process flight for the stimulus and constitutes a neuronal action-reaction mirror type response. For example, in a newborn, the mother’s smell Qη might in a primary process fashion lead to discharge of the sucking movement, commanded by neurone b; the sucking is then the mirror signification of the smell Qη.

Figure 1. The difference between the primary and the secondary functioning of Freud’s neuronal apparatus (explanation see text).

However, if the nipple is not in front of the mouth, sucking will not bring milk, but disappointment. When there is hunger, a specific action needs to be constituted, which can bring the nipple in front of the mouth. Freud (Citation1895) proposes: “While the ego is in a wishful state, it newly cathects the memory of an object and then sets discharge in action” (p. 325). In other words, when the baby is hungry, s.he charges the memory of the mouth on the nipple with cathexis; this is the wishful state. This activation of the memory constitutes the “third powerful factor” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 323) or action goal, which is able to intervene between the first two powers (the triggering stimulus and the facilitated neurone pathway). Indeed, the cathexis of the action goal is now able to oppose facilitation: “If an adjoining neurone is simultaneously cathected,” this side-cathexis adjacent to the facilitated neurone “acts like a temporary facilitation” (p. 323). Even if the a–b route is the most facilitated, a might not lead to b “if a is also influenced by a cathected neurone α,” i.e. precisely by this side-cathexis. In other words, having a goal in mind can counteract associative action-reaction discharge. Now, say neurone complex δ in Freud’s drawing is the representation (or memory) of the nipple in front of the mouth (the action goal). When this representation gets cathected (in the wishful state), then this cathexis will associatively spill over from δ to all proximal connections to this action goal. Indeed, there might be many types of turns of the head leading to having a front view of the nipple. When the cathexis in δ spills over to its different pathways which lead to δ, a backward current initiated in δ is set up; this is the exact same logic as found in the so-called inverse models for motor control (e.g. Wolpert & Kawato, Citation1998). Among these pathways, the pathway δ–γ–β–α happens to have a connection with neurone a ending up in the side-cathexis a–α. This means that when a is cathected, this cathexis could be passed on to either the facilitated neurone complex b, and/or to the cathected neurone complex α. Freud (Citation1895) says that the Qη in a “is so much influenced by the side-cathexis a–α that it gives off only a quotient to b and may even perhaps not reach b at all” (pp. 323–324). In that case, the backward current initiated in the action goal has overruled the facilitated connection. Or concretely, the mother’s smell (a), instead of leading to a direct sucking discharge (a–b), is “being picked up” by a cathected neurone (α), originating in the (desire to have the) mouth in front of the nipple (δ), and results into specific actions (discharging in head turn movements) whereby the mouth is eventually in front of the nipple (a–α–β–γ–δ). This is top-down action organization. Freud (Citation1895) concludes that the cathected neurone α “modifies the course [of the current], which would otherwise have been directed towards the one facilitated contact-barrier. A side-cathexis thus acts as an inhibition of the course of Qη. (…) Therefore, if an ego exists, it must inhibit psychical primary processes” (p. 323–324). In other words, having a goal in mind can counteract the tendency to be driven by outside stimuli.

However, being driven by an eliciting stimulus versus being driven by a goal is not what essentially distinguishes primary from secondary process dynamics. Indeed, one can have a goal in mind so intensely that s.he comes to act upon that wish without a real object in the world. For example, when a newborn, driven by hunger, without the mother being present, hallucinates a breast and sucks in the air, “satisfaction must fail to occur, because the object is not real but is present only as an imaginary idea.” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 325). In this case, despite its origin in a wishful state, the hallucination is a primary process. In the beginning, the mental apparatus cannot make a distinction between a hallucinated breast and a perceived breast: “since it can only work on the basis of the sequence of analogous states between its neurones” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 325; italics added). Indeed, in the beginning the so-called “system Ψ”Footnote2 only works based on a primary process associative transfer of cathexes – a dynamic which we will call “sliding” for the purpose of brevity. But there must be a way to find out if the wishful state δ is indeed reached in outside reality and is not an internal production. Therefore, a second criterion is needed for there to be a secondary process, namely the indications of reality. For the distinction between memory and perception, the newborn “requires a criterion from elsewhere (…) It is probably the ω neurones which furnish this indication: the indication of reality” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 325, italics added).

There is confusion concerning the ω neurones. Indeed, Freud says that they are “excited along with perception, but not along with reproduction” and “behave like organs of perception” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 309); hence they are often erroneously called perception or perceptual neurones. However, these “neurones must have a discharge, however small (…) The discharge will, like all others, go in the direction of motility” (p. 311). For this reason, the ω-neurones are undoubtedly motor neurones. One good way to understand them is to consider them as the motor neurones belonging to the sense organs – e.g. oculomotor neurones. Freud (Citation1895) confirms this interpretation: “It must be assumed that the ω neurones are originally linked anatomically with the paths of conduction from the various sense-organs and that they direct their discharge back to the motor apparatuses belonging to those same sense organs” (p. 326): in the case of oculomotor neurones, for example, they are linked with the eyes and direct their discharge to the muscles around the eyes. When Freud (Citation1895) says: “The filling of ω neurones with Qη can no doubt only proceed from Ψ” (p. 311), this means that we actively look where we want to see (given by Ψ) – this is the top-down dynamic. Indeed, perception, to Freud, is the active grasp of the sensation (see “action-based theories of perception;” Briscoe & Grush, Citation2020), but, if it were limited to this, the danger exists that we see what we want to see. However, the dynamic is reciprocal, as the ω discharge now also activates Ψ: “the information of the latter discharge (the information of reflex attention) will act to Ψ biologically as a signal to send out a quantity of cathexis in the same directions.” The information of the discharge of the oculomotor neurones (“the reflex attention”) gives a central signal to pay attention to what the eyes see at that spot.

Now, Freud (Citation1895) explains: “In the case of every external perception a qualitative excitation occurs in ω. It must be added that the ω excitation leads to ω neurones discharge, and information of this, as of every discharge, reaches Ψ. The information of this discharge from ω is thus the indication of quality or reality for Ψ” (p. 325; italics added). In other words, if at that spot there effectively is an external object, the oculomotor neurones will discharge in order to follow the contours of the object, to “grasp it by the gaze” (“a qualitative excitation”). Moreover, information of the discharge of the ω-neurones will, like every discharge information, return to the brain gray matter, arriving at motor areas of the brain. That is, when the breast is effectively present, the baby not only has visual content information (corresponding to occipital activation) but also simultaneous discharge information “from elsewhere” (the motor centers) which attests that the visual content information is indeed a perception.

Freud calls the “information of (motor) discharge” the indication of (quality or of) reality. I have previously proposed (Bazan, Citation2007a, Citation2007b; Citation2012) that Freud derived the notion of “indications of reality” from Hermann von Helmholtz’ concept of “direct perception of innervation.” Indeed, von Helmholtz was one of Freud’s masters of the popular Berlin school of physiology and proposed that we do not wait for the (slow) peripheral proprioceptive result of the oculomotor commands to understand the position of the pupil in the eye, and thereby the localization of the visual target. Instead, we use the direct feedback of the given motor command: “The impulse to movement that we give through innervation of our motor nerves, is something directly perceivable” (Helmholtz, Citation1878b, p. 349). If an image of a breast is accompanied by such direct information, coming from the discharge of the ω neurones and indicating that the contours of a breast were followed, then the image information is a perception. In case the image is not accompanied by ω neurone discharge information, then it is an imagination or a memory.

However, if “the wished-for object is abundantly cathected, so that it is activated in a hallucinatory manner,” then “the same indication of discharge or of reality follows too as in the case of external perception. In this instance the criterion fails.” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 325): if we imagine so intensely the breast that we make eye-movements as if there indeed was a breast, then the imagination feels real, and we have a hallucination. “But if the wishful cathexis takes place subject to inhibition, as becomes possible when there is a cathected ego, (…) the wishful cathexis, not being intense enough, produces no indication of quality, whereas the external perception would produce one. In this instance, therefore, the criterion would retain its value” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 325): but if, thanks to a “cathected ego,” wishful impulses are systematically dampened, then, merely wishing to see the breast will not result in eye movements, and the ω discharges retain a criterion value. And thus: “if there is inhibition by a cathected ego, the indications of ω discharge become quite generally indications of reality” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 326) and in the case of a nipple effectively in front of the mouth, and there is hunger, sucking can be released. Freud concludes: “Wishful cathexis to the point of hallucination [… is] described by us as psychical primary processes; by contrast, those processes which are only made possible by a good cathexis of the ego, and which represent a moderation of the foregoing, are described as psychical secondary processes” (Freud, Citation1895, pp. 326–327).

In summary, the first defense of Ψ against impinging stimuli is to transfer them from “neurone to neurone” (from representation to representation) or from “state” to (analogous) “state” in order to reach the exit door (muscular action) allowing discharge. But especially for internal alarms (e.g. hunger), this doesn’t affect the source of excitations, and a specific action needing a store of energy is needed. This store is gradually built up by facilitation in the ego: paradoxically, the facilitated system can withhold cathexis (by having it circulating within the system). This store of energy and the memory of the action goal (or the purposive image, see further) counteract the easy transfer over the chain of analogous states, or the “sliding,” by imposing its inhibition-by-cathexis upon them. However, this would remain simply another source of analogous “sliding,” were there not an intervention “from elsewhere.” Indeed, perceived and wishful images are contrasted with the direct return of a motor grasp upon the world, which checks for the exterior presence of the object, and by use of a criterion, the indications of reality, derived from the motor command of that grasp, will either confirm or infirm that presence and accordingly, lift the inhibition upon the discharge into action.

Two modes of acting and thinking

In his later work Freud links primary and secondary processes to perceptual and thought identity and to pleasure and reality principle, respectively. Indeed, he proposes: “the primary process endeavours to bring about (…) a ‘perceptual identity’” (Freud, Citation1900, p. 602). This identity is a direct path from the memory of satisfaction to the cathexis of that memory: “the reappearance of the perception is the fulfilment of the wish; and the shortest path to the fulfilment of the wish is a path leading direct from the excitation produced by the need to a complete cathexis of the perception” (Freud, Citation1900, p. 566), which would be a hallucination. Brakel and I (Bazan & Brakel, Citation2023) stress that the association pathway works on the basis of non-essential, superficial features or attributes. Freud (Citation1900, p. 530) also includes phonological characteristics: “assonance, verbal ambiguity, and temporal coincidence, without inner relationship of meaning; in other words, (…) all those associations which we allow ourselves to exploit in wit and playing upon words.”Footnote3 In 1911, Freud proposes: “The sovereign tendency obeyed by these primary processes is (…) called (…) the pleasure principle (…) This attempt at satisfaction by means of hallucination was abandoned only in consequence of the absence of the expected gratification, because of the disappointment experienced. Instead, the mental apparatus had to decide to form a conception of the real circumstances in the outer world and to exert itself to alter them. (…) what was conceived of was no longer that which was pleasant, but that which was real, even if it should be unpleasant. This institution of the reality-principle proved a momentous step” (p. 14). Freud (Citation1911) does not explicitly link the reality principle to the secondary process, but this is implied by what immediately follows: “Restraint of motor discharge (of action) had now become necessary, and was provided by means of the process of thought (…). It is essentially an experimental way of acting, accompanied by displacement of smaller quantities of cathexis together with less expenditure (discharge) of them. For this purpose conversion of free cathexis into ‘bound’ cathexes was imperative” (p. 16). In other words, the secondary process by restraining motor discharge, invests more readily into thinking in the form of “an experimental way of acting” than does the primary process (see also, Pfeffer, Citation1998). The identity, established through the secondary process, concerns the action goal and by counteracting facilitation this opens the possibility to explore unsuspected thought paths. In other words, this thinking “must concern itself with the connecting paths between ideas, without being led astray by the intensities of those ideas.” (Freud, Citation1900, p. 602). But “it is easy to see, too, that the unpleasure principleFootnote4 (…) puts difficulties in its path towards establishing ‘thought identity.’:” if thinking rushes too quickly towards discharge, the exploration of new paths to search for thought identity is compromised. Laplanche and Pontalis (Citation1967) accordingly propose that the identity of thought “aims at freeing the psychic processes from the excessive regulation by the pleasure principle” (p. 194).

In 1920 Freud proposes: “The pleasure principle seems actually to serve the death [drive]” (p. 87), the (bodily) inclination to return to a state of quiescence (namely, that which preceded our birth), and thus an aim of reducing psychical tension to the lowest possible point. This is logical, as the pleasure principle strives for cathexis discharge, but: “[the reality] principle does not abandon the intention of ultimately obtaining pleasure, but it nevertheless demands and carries into effect (…) the temporary toleration of unpleasure as a step on the long indirect road to pleasure. (…) The reaction to these [drive] demands (…) can then be directed in a correct manner by the pleasure principle or the modified reality principle” (Freud, Citation1920, p. 6, 8). In other words, both pleasure and reality principle, and therefore both primary and secondary processes, serve the death drive, the search for discharge. In this, primary and secondary are concurrent processes: Freud (Citation1900) clarifies that “no psychical apparatus exists which possesses a primary process only and that such an apparatus is to that extent a theoretical fiction” (p. 603). Green (Citation1995) is explicit: “Primary and secondary processes must be able, in the same individual, to remain in close connection and be able to exist separately. Most of the time, they work concurrently and jointly” (p. 152).

Since both processes serve the same final goal, namely discharge through wish-fulfillment and since “all thinking is no more than a circuitous path from the memory of a satisfaction (a memory which has been adopted as a purposive idea) to an identical cathexis of the same memory which it is hoped to attain once more through an intermediate stage of motor experiences” (Freud, Citation1900, p. 602, italics added), both processes are to be considered as modes of thinking. Holt (Citation2002) also speaks about a “theory of thinking” referring to the primary and secondary processes which he sees as “continuous variables” (p. 461). Calling the primary process “emotional” or “instinctual” in opposition to a “rational” secondary process might suggest that primary process is situated at a subcortical level (Panksepp, Citation2004; Panksepp & Biven, Citation2012). However, as seen, both processes are in the first-place action pathways, and thus situated neocortically. Moreover, in Freud’s view, the primary process is explicitly linguistic, confirming a neocortical localization: e.g. “In schizophrenia, words are subject to the same process as that which makes dream images out of dream thoughts, the one we have called the primary process. They undergo condensation, and by means of displacement transfer their cathexes to one another in their entirety” (Freud, Citation1915, p. 186).Footnote5 Moreover, primary and secondary are also – up to a certain extent – variations of each other. Indeed, as seen, secondary processes also involve primary process associativity in their built-up, when the cathexis spills over from the “purposive idea” to its neighboring associations. Therefore, it might be that what is a primary process, is so in reference to what is a secondary process, but that this secondary process might in its turn become the primary process of a “higher” secondary process, with a higher overarching goal. For Rapaport (Citation1951, p. 709) there is a “continuous transition” between both and they emanate from one and the same “undifferentiated matrix.” Freud (Citation1895) indeed opposes the sharp dichotomy primary/unconscious and secondary/conscious processes: “consciousness does not cling to the ego but can become an addition to any Ψ processes. It warns us (…) against possibly identifying primary processes with unconscious ones” (p. 340). For all these reasons, we refute the dichotomy between a “rational” secondary process and an “archaic” (Fenichel, Citation1945, p. 15), “primitive” (Moore & Fine, Citation1990; Holt, Citation2009, p. 3; Russ, Citation2020), “regressive” (ex. Gill & Brenman, Citation1959; Kris, Citation1952), “chaotic” (Gammelgaard, Citation2006) or “autistic, bizarre and illogical” (Pinnell et al., Citation1998) primary process.

Ventral-dorsal dichotomy and efference copies

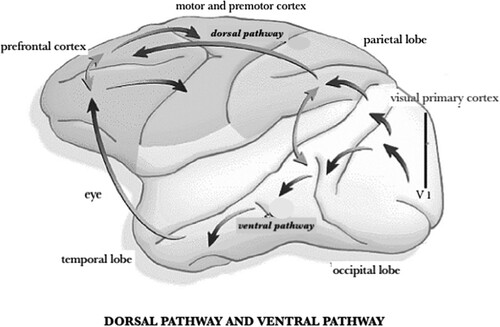

The neocortical thinking model which does justice to the details of Freud’s model is the neuroscientifically well-established ventral-dorsal dichotomy, as I have argued previously (Bazan, Citation2007a, pp. 96–98; Bazan, Citation2007b; see ). The ventral pathway, which leads to the temporal lobe, is the “What?”-pathway or “object-channel” where basic visual attributes – such as contours, shape, texture, color etc. – of an object are assembled and bound together forming elementary visual percepts (Milner & Goodale, Citation1995; Ungerleider & Mishkin, Citation1982). Multiple parallel ways can thereby lead to the identification of objects based on one of their attributes, which corresponds precisely to the “perceptual identity” of the primary process (see also Roussillon (Citation2007, p. 42) quoting Varela on precisely this aspect). Indeed, a major evolutionary value of the primary process resides in the fact that it enables stability of perception, by searching for an identity of the perception, independently of the context (see also Cutler & Brakel, Citation2014). An object can thereby be identified as such, even if it is only perceivable through one of its attributes or aspects. When one only sees the tail of the cat (an attribute), one “sees” the cat. The ventral pathway is also the pathway for the visual imagery of objects in Jeannerod and Jacob’s (Citation2005) model: in the ventral pathway there is segregation of a scene “into separable objects and binding to each object of its appropriate visual attributes” (p. 303). Not only do we find in this approach the central concept of “attribute” to define the primary process (Bazan & Brakel, Citation2023), but also the idea of “separability.” The primary process functions by isolated positive-content elements, without being much hindered by their mutual relationships. This is the case to an extreme extent for dreams: “a dream is a conglomerate which (…) must be broken up once more into fragments” (Freud, Citation1900, p. 449) – for example, a dream speech turns out to be composed of multiple fragments from different conversations in waking life (Freud, Citation1900, p. 428). Therefore, dream analysis requires cutting the dream into separable elements and treating each element as an independent starting point for an associative chain (Freud, Citation1900): “What we must take as the object of our attention is not the dream as a whole but the separate portion of its content” (p. 103).

Figure 2. The ventral pathway, leading to the temporal lobe, is the “What?”-pathway where basic visual attributes – such as contours, shape, texture, color etc. – of an object are assembled. It is then also the pathway where these separable elements or attributes can lead to the perceptual identification of an object, in much the same way as Freud proposed for the primary process. The dorsal pathway, leading to the parietal lobe, is the “Where?”-pathway where action plans are spatiotemporally elaborated, in much the same way as Freud proposed for the secondary process.

The dorsal pathway, which leads to the parietal cortex, is the “Where?”-pathway which enables spatial localization (Ungerleider & Mishkin’s, Citation1982 model) or the “vision for action” pathway responsible for reaching and grasping objects, i.e. for goal-directed action (Milner & Goodale, Citation1995). In Jeannerod’s view, it allows the handling of complex representations of actions such as schemas for the use of cultural tools (Jeannerod, Citation1994; Jeannerod & Jacob, Citation2005). Both these aspects of purposive acting and spatiotemporal localization are defining elements of the secondary process. Moreover, as the ventral pathway proposes candidates (for identities, for reactions), the dorsal pathway selects the appropriate candidates in function of the context and inhibits the non-contextual ones (Friedman-Hill et al., Citation2003; Rousselet et al., Citation2004). This neuroanatomy also fits with inhibitory action of the secondary upon the primary process.

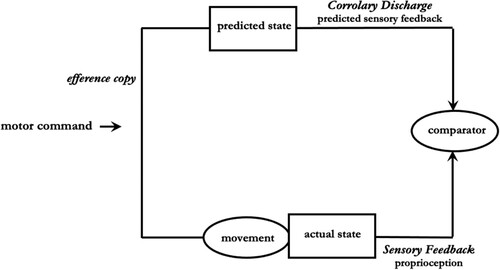

However, all this would remain essentially a juxtaposition of concepts, were it not that both models also strategically rest upon the concept of “efference copies,” which are directly derived from the motor commands, and induce changes in the sensorimotor cortices informing that a motor command was just sent out and precisely what proprioceptive feedback is expected from these motor commands (Blakemore et al., Citation2000; Jeannerod, Citation2003; see ). Efference copies trace back to von Helmholtz’s original concept (see above) leading to a theoretical physiological development, independently of psychoanalysis, namely the concept of “efference copies.” I have proposed (Bazan, Citation2007a, Citation2007b; Citation2012) that these efference copies are the precise equivalent of Freud’s indications of reality, based on an accumulation of criteria.

Figure 3. The efference copy model. This computational model proposes that upon motor intention, copies of the efferent motor command are fed back and used centrally in an emulation algorithm, which calculates the predicted somatosensory changes expected as a consequence of the prescribed motor execution. Upon effective execution, peripheral changes at the muscles, the joints and the skin generate an actual proprioceptive feedback, which will (more or less) balance out the predicted sensory feedback in the parietal somatosensory cortex at the level of a so-called “comparator.”

First, both the Freudian indications of reality and the efference copies have the Helmholtzian model as common origin. Second, their physiological position is the same: both the indications of reality and the efference copies are reafferent messages derived from the motor commands (and there the semantics are very much identical as we have seen that Freud calls the indications of reality the Abfuhr Nachrichte (Freud, Citation1895, p. 325), or “efference information”). Third, their mental function is the same: Freud shows how the indications of reality allow the distinction between an internal and an external origin of a representation, while efference copies allow the distinction between a self-initiated and an imposed movement (which is equivalent, knowing that a representation or thought is in both models an experimental movement). Fourth, a mature ego is required for the indications of reality to be a functional criterion, while for the generation of functional efference copies the organism must already have acquired the movement, or in other terms a functional prefrontal cortex, or even a constituted “default mode network” (DMN; see further) – and, furthermore, ego and prefrontal cortex (Bazan, Citation2007a), or ego and DMN have also been equated (Carhart-Harris & Friston, Citation2010). Fifth, Freud shows the role of the absence of indications of reality in psychosis, while multiple authors (e.g. Frith et al., Citation2000) implicate dysfunction or absence of efference copies in psychotic symptoms such as voices and delusions of control. Finally, in the ventral-dorsal pathway, efference copies of motor commands converge on the posterior parietal cortex to form a representation of space, used for the coding of appropriate movements (e.g. Jeannerod et al., Citation1995). In other words, the dorsal pathway’s dynamics depend on the efference copies, in the same way the secondary process needs the “indications of reality”-criterion. All these elements make a convincing case that efference copies and indications of reality are indeed the same species.

Predictive coding and efference copies

The efference copies have been absorbed in the predictive coding model, where their role does not seem explicit (see also Vallortigara, Citation2021, p. 2). In predictive coding, the brain attenuates sensory returns based on the previous sensory state of the body: the brain forms predictions based on its prior beliefs and continuously updates them to minimize any error between the predicted and the incoming sensory information (e.g. Friston, Citation2010). Kilteni and colleagues (Citation2020) specify how this generalized predictive mechanism does not consider the efference copy as a prerequisite, even if it does not necessarily speak against the efference copy model. Rather, it would favor a universal predictive mechanism underlying all multisensory bodily events, including somatosensory attenuation, that is not necessarily based on motor signals. However, even if it makes intuitive sense that good computation based on the past would be able to make increasingly better guesses about the future, the logical problem remains essentially the same as the one identified by Freud, namely that a distinction between the internal or external origin of a stimulation is impossible “on the basis of the sequence of analogous states” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 325; italics added). When the organism not only needs to predict what stimulation will come next (primary process), but also if the source of this stimulation is internal or external, this “requires a criterion from elsewhere (…) It is probably the ω neurones which furnish this indication: the indication of reality” (Freud, Citation1895, p. 325, italics added). Thereby, the distinctive role of motricity, of the organism’s action in constructing a secondary process-type reality, is diluted or obscured in the predictive coding models.Footnote6

Solms (Citation2020) relies heavily on Friston (Citation2010), who proposed that the brain works as an adaptive inference machine that can minimize “free energy” (prediction error or “surprise”) by employing internal hierarchical models to predict sensory input. For Carhart-Harris and Friston (Citation2010) Freud’s primary/secondary process distinction is in line with the Cs/Pcs system executing top-down inhibition to minimize unconscious primary process “free energy,” which corresponds to Freud’s unbound cathexis. For Solms (Citation2020) the “primary process” (which he puts into quotes) has freely mobile cathexis as a vehicle and he equates that unbound cathexis with “the automatized response modes of the nondeclarative memory systems.” It is beyond the scope of this paper to go into the details of both predictive coding-based models for primary and secondary processes but we point out some differences with the Freudian model in the present paper. First, the hierarchical classification of the secondary process as belonging to the system Cs/Pcs and of the primary process as being non-declarative and/or as belonging to the system Ucs is misleading. Indeed, as shown, the dichotomy is not a defining dichotomy for the primary and secondary processes and the primary process is also linguistic, including linguistic in a declarative wayFootnote7 (see above and Bazan, Citation2007a). Second, and as said, the constitutive role of motor action, tied to the ω neurones, is obscured, while it is, in our view, the only way to escape the sliding of the analogous states of mind – for we should never a priori suppose that an organism/a human can orient itself among its mental images and distinguish internally generate and externally induced representations. Third, and relatedly, the description of the primary process as “automatized response modes” confirms the obscuring, or even erasing, of the acting subject altogether in the primary process as an automatic process is defined as the activation of a sequence of nodes “without the necessity for active control or attention by the subject” (Schneider & Shiffrin, Citation1977, pp. 2–3). Thereby the predictive coding model might be yet another way to think of a subjectless mental level, of a mental level where subjects would not differ from each other. However, in a psychoanalytic perspective, in contrast to cognitive approaches, the subject is also implied in the primary process mentation. Indeed, the primary as well as the secondary processes are from the start and fundamentally oriented by the wishful state. Moreover, an accumulating body of empirical evidence shows that personality indeed plays a major role in the extent of primary process mobilization and in so-called “low level computations” such as phonological treatment (e.g. Klein Villa et al., Citation2006; Bazan et al., Citation2019; Thieffry et al., Citation2023).

The ego, the DMN and repetition compulsion

Not all dynamic aspects of the secondary process are covered by the reality principle nor by the death drive. Indeed, Freud also indicated that the “necessities of life” oblige the organism to bear the tension of maintaining a “store of excitations.” This accumulation of tension in the ego, by definition, corresponds to the life drive – a store of accumulated psychical tension, which will be needed for the specific acts to survive and reproduce – so that the secondary process serves both death and life drives.Footnote8 Now, this store of excitations is brought about by a ramified ego, matured through experience, where the activations turn around in a facilitated system, which is similar to the definition of the DMN. Any specific act, organized in a secondary process way, will draw from this ego, both from its stored excitations and from its useful bits and pieces of existing associations, built up by our history, which presumably are part of the connections constituting this ego. This process of tapping into the ego seems very much in line with the well described anticorrelation between the DMN and the so-called Dorsal Attention Network (DAN, Fox et al., Citation2005): whenever task-specific attention is needed, the DMN dissolves and the DAN lights up. The DMN or ego realm, where the “mind wanders” when a new action strategy needs to be designed (Crittenden et al., Citation2015), is inevitably marked by our early interactions with our first caregivers and by the specificities of our relationships to them – that is, by the influence of repetition compulsion or the propensity to repeat formative early life experiences. Say, for example, a stressed caregiver has taught the child to keep quiet during (care) interactions to avoid problems; the later adult will likely associate situations of (care) interactions with a tendency to withdraw based on the fast nodes in his “ego store”, leading him to disengage more readily from social exchanges. Likewise, as we ultimately might have to rely upon our ego store for all of our constituted actions, there might be a (slight) touch of repetition compulsion in all what we do. In other words, we need our history to create a store of excitations required for the secondary process, the ego, but this then comes with at least a small tribute payment to our history. We now see how the Freudian model matches the complexities of our human condition: on a horizontal plane of “analogous states,” life would (unstoppably) flow out of the organism through (growingly efficient) discharge mechanism, i.e. life would “bleed to death.” However, the secondary process cuts through this horizontal plane, instilling a vertical repetition compulsion (the life drive), which, at a high price in suffering, hinders total discharge. In a counterintuitive way, we propose that repetition compulsion is the price which comes with secondary processes, putting them in a different light than given by the shine of rationality.

Conclusion

The more generalized use of the concepts of primary and secondary processes has come with a tendency of simplification, polarization and reduction. However, at their origin, these processes were very precisely articulated by Freud and we propose that it is still this original view which is the most robust against this reductive tendency, and probably it is for this reason the model that most soundly integrates with other scientific approaches, without clinical simplification. Among the levels of complexities in Freud’s apparently simple theories, we distinguish the dynamical, reciprocal interaction of bottom-up and top-down (“analogous”) states and the need for “a sign coming from elsewhere,” tied to the subject’s active take on the world (the active rub against the world and the effects of this rub), in order to escape the sliding of analogous states. As seen, this sign requires the bearing of a store of excitations within a facilitated network, created by history, and this might have far-fetching consequences – namely, for the specific action of the subject to be caught up by a touch of repetition compulsion. In other words, there might be in the theory of primary and secondary process the whole drama of human condition: the secondary process helps us out of an infinite sliding of analogous states but implies the danger of an infinite rotation into repetition compulsion. Nobody said mental life is simple.

Acknowledgements

The author wants to thank Mr. Bob Berry for his unwavering support over the years. Ariane Bazan is also profoundly indebted to Howard Shevrin for his invaluable mentorship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 or quantity of excitations (or energy or tension), i.e. of libido.

2 Freud’s (Citation1895, p. 303) system Ψ is the system to which “the development of the nervous system and the psychical functions are attached”: it is in essence the mental apparatus. In Freud’s model, Ψ has no peripheral connections (these are provided by Freud’s system of permeable neurones Φ which constitute the perception system) but it receives the endogenous excitations and corresponds with the gray matter.

3 They are frequently based upon phonological ambiguity: ex. “Why did Shakespeare only write using pens? Pencils confused him. 2B or not 2B.” or “What does a grape say after it's stepped on? Nothing. It just lets out a little wine!”.

4 Until 1911, Freud called the “pleasure principle” the “unpleasure principle”.

5 See also for dreams (Freud, Citation1900): “Suppose I have a picture-puzzle, a rebus, in front of me (…) obviously we can only form a proper judgment of the rebus if (…) we try to replace each separate element in some way or other. The words which are put together in this way are no longer nonsensical but may form a poetical phrase of the greatest beauty and significance. A dream is a picture-puzzle of this sort and our predecessors in the field of dream-interpretation have made the mistake of treating the rebus as a pictorial composition” (p. 278): dreams operate a linguistic (phonological) translation of images, and this is a primary process – and see for a modern verification of this linguistic principle Olyff & Bazan, Citation2023.

6 A comparable obscuring of the crucial role of motor dynamics was already the case in the mirror neurone models.

7 One might dispute the difference between linguistic and declarative. Freud stresses the attempt of the unconscious in dreams to convey a message using language, so even the position that primary process is non-declarative might be problematic: e.g. “The dream-work can often succeed in representing very refractory material, such as proper names, by a far-fetched use of out-of-the-way associations” or “In this respect the dream-work is treating numbers as a medium for the expression of its purpose in precisely the same way as it treats any other idea, including proper names and speeches that occur recognizably as verbal presentations.” (Freud, Citation1900, resp. pp. 413 and 418; italics added).

8 Together with Detandt (Bazan & Detandt, Citation2013), we have also put this tension store in parallel with the Lacanian concept of jouissance.

References

- Bazan, A. (2007a). Des fantômes dans la voix. Une hypothèse neuropsychanalytique sur la structure de l’inconscient. (Phantoms in the voice. A neuropsychoanalytic hypothesis on the structure of the unconscious). Liber, Montréal.

- Bazan, A. (2007b). An attempt towards an integrative comparison of psychoanalytical and sensorimotor control theories of action. In P. Haggard, Y. Rossetti, & M. Kawato (Eds.), Attention and performance XXII (pp. 319–338). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199231447.003.0015.

- Bazan, A. (2012). From sensorimotor inhibition to Freudian repression: Insights from psychosis applied to neurosis. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 452. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00452

- Bazan, A., & Brakel, L. A. W. (2023). The GeoCat 1.3, a simple tool for the measurement of Freudian primary and secondary process thinking. Neuropsychoanalysis. 25, 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2023.2169955

- Bazan, A., & Detandt, S. (2013). On the physiology of jouissance: Interpreting the mesolimbic dopaminergic reward functions from a psychoanalytic perspective. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 709. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00709

- Bazan, A., Kushwaha, R., Winer, E. S., Snodgrass, J. M., Brakel, L. A. W., & Shevrin, H. (2019). Phonological ambiguity detection outside of consciousness and its defensive avoidance. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13, 77. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00077

- Bergeret, J. (1974). La personnalité normale et pathologique. Dunod.

- Blakemore, S.-J., Wolpert, D., & Frith, C. (2000). Why can't you tickle yourself? NeuroReport, 11(11), R11–R16. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001756-200008030-00002

- Bliss, T. V. P., & Lomo, T. (1973). Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. Journal of Physiology, 232(2), 331–356. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273

- Briscoe, R., & Grush, R. (2020). Action-based theories of perception. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy.

- Carhart-Harris, R., & Friston, K. (2010). The default mode, ego-functions and free-energy: A neurobiological account of Freudian ideas. Brain, 133(4), 1265–1283. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq010

- Crittenden, B. M., Mitchell, D. J., & Duncan, J. (2015). Recruitment of the default mode network during a demanding act of executive control. Elife, 4, e06481. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.06481

- Cutler, S., & Brakel, L. A. W. (2014). The primary processes: A preliminary exploration of a-rational mentation from an evolutionary viewpoint. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 34(8), 792–809. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690.2014.968022

- Feldstein, R., Jaanus, M., Fink, M. (1994). Reading seminar XI: lacan's four fundamental concepts of psychoanalysis: The Paris seminars in english. State University of New York Press.

- Fenichel, O. (1945). The psychoanalytic theory of neurosis. Norton.

- Fox, M. D., Snyder, A. Z., Vincent, J. L., Corbetta, M., Van Essen, D. C., & Raichle, M. E. (2005). The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(27), 9673–9678. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0504136102

- Freud, S. (1895/1966). Project for a scientific psychology. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. I, pp. 281–392). Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1900/1958). The interpretation of dreams. J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.). (Vols. IV and V). Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1911/1953). Formulations regarding the two principles in mental functioning. In E. Jones (Ed.) & J. Rivier (Trans.), Collected Papers (Vol. IV, 13–21). The International Psycho-analytical library. London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-analysis.

- Freud, S. (1915). The unconscious In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. XIV, 159–215). London: Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1920/1950). Beyond the pleasure principle. In E. Jones (Ed.), The international psycho-analytical library No. 4 (pp. 1–97). The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-analysis.

- Friedman-Hill, S. R., Robertson, L. C., Desimone, R., & Ungerleider, L. G. (2003). Posterior parietal cortex and the filtering of distractors. Proceedings of the National. Academy of Sciences of the USA, 100(7), 4263–4268. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0730772100

- Friston, K. J. (2010). The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2787

- Frith, C., Blakemore, S. J., & Wolpert, D. M. (2000). Explaining the symptoms of schizophrenia: Abnormalities in the awareness of action. Brain Research Reviews, 31(2–3), 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00052-1

- Gammelgaard, J. (2006). Primary process in metapsychology and cognitive psychology. The Scandinavian Psychoanalytic Review, 29(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/01062301.2006.10592788

- Gill, M. M., & Brenman, M. (1959). Hypnosis and related states: Psychoanalytic studies in regression. International Universities Press.

- Green, A. (1995). Propédeutique. La métapsychologie revisitée. Champ Vallon.

- Helmholtz, H. (1995 [1878]). The facts in perception. In Cahan (Ed.), Science and culture (pp. 342–380). University of Chicago Press.

- Holt, R. R. (2002). Quantitative research on the primary process: Method and findings. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 50(2), 457–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/00030651020500021501

- Holt, R. R. (2009). Primary process thinking: Theory, measurement, and research, Volume I. Jason Aronson Press.

- Jeannerod, M. (1994). The representing brain: Neural correlates of motor intention and imagery. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 17(2), 187–245. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00034026

- Jeannerod, M. (2003). Action monitoring and forward control of movements. In M. Arbib (Ed.), The handbook of brain theory and neural networks (2nd ed., pp. 83–85). MIT Press.

- Jeannerod, M., Arbib, M. A., Rizzolatti, G., & Sakata, H. (1995). Grasping objects: The cortical mechanisms of visuomotor transformation. Trends in Neurosciences, 18(7), 314–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(95)93921-J

- Jeannerod, M., & Jacob, P. (2005). Visual cognition: A new look at the two-visual systems model. Neuropsychologia, 43, 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.11.016

- Jones, E. (1953). The life and work of Sigmund Freud: Vol.1– The formative years and the great discoveries. Basic Books.

- Kilteni, K., Engeler, P., & Ehrsson, H. H. (2020). Efference copy is necessary for the attenuation of self-generated touch. iScience, 23(2), 100843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.100843

- Klein, G. (1967). Psychoanalytic theory– An explanation of essentials. International Universities Press.

- Klein Villa, K., Shevrin, H., Snodgrass, M., Bazan, A., & Brakel, L. A. W. (2006). Testing Freud’s hypothesis that word forms and word meaning are functionally distinct: Subliminal primary-process cognition and its link to personality. Neuropsychoanalysis, 8(2), 117–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2006.10773521

- Kris, E. (1952). Psychoanalytic exploration in art. International University Press.

- Laplanche, J., & Pontalis, J.-B. (1967 / 2009). Vocabulaire de la psychanalyse. Presses Universitaires de France. p.194.

- Milner, A. D., & Goodale, M. A. (1995). The visual brain in action. Oxford University Press.

- Moore, B., & Fine, B. (1990). Psychoanalytics terms and concepts. Yale University Press. 148.

- Olyff, G., & Bazan, A. (2023). People solve rebuses unwittingly—both forward and backward: Empirical evidence for the mental effectiveness of the signifier. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 16, 965183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.965183

- Panksepp, J. (2004). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. Oxford.

- Panksepp, J., & Biven, L. (2012). The archaeology of mind: Neuroevolutionary origins of human emotion. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Pfeffer, A. (1998). Thought as trial action. Journal of Clinical Psychoanalysis, 7(1), 115–126.

- Pinnell, C. M., Lynn, S. J., & Pinnell, J. P. (1998). Primary process, hypnotic dreams, and the hidden observer: Hypnosis versus alert imagining. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 46(4), 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207149808410014

- Rapaport, D. (1951). Towards a theory of thinking. In D. Rapaport, Organization and pathology of thought: Selected sources (pp. 689–730). Columbia University Press.

- Rousselet, G. A., Thorpe, S. J., & Fabre-Thorpe, M. (2004). How parallel is visual processing in the ventral pathway? TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences, 8(8), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.06.003

- Roussillon, R. (2007). La réalité psychique de la subjectivité et son histoire. In R. Roussillon, Manuel de psychologie et de psychopathologie clinique générale (pp. 3–232). Elsevier-Masson.

- Russ, S. W. (2020). Mind wandering, fantasy, and pretend play: a natural combination. In: Creativity and the wandering mind. Spontaneous and controlled cognition. In D. D. Preiss, D. Cosmelli, & J. C. Kaufman (pp. 231–249). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2017-0-04080-6

- Schneider, W., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: I. Detection, search, and attention. Psychological Review, 84(1), 1–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.1.1

- Shevrin, H. (1973). Brain wave correlates of subliminal stimulation, unconscious attention, primary and secondary process thinking, and repression. In M. Mayman (Ed.), Psychoanalytic research: Three approaches to the study of subliminal processes (pp. 56–87). Psychological Issues, 30. International Universities Press.

- Solms, M. (2020). New project for a scientific psychology: General scheme. Neuropsychoanalysis, 22(1–2), 5–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2020.1833361

- Thieffry, L., Olyff, G., Pioda, L., Detandt, S., & Bazan, A. (2023). Running away from phonological ambiguity, we stumble upon our words - Laboratory Induced Slips show differences between high and low defensive people. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 1717, 1033671. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2023.1033671

- Ungerleider, L., & Mishkin, M. (1982). Two cortical visual systems. In D. J. Ingle, M. A. Goodale, & R. J. W. Mansfiled (Eds.), Analysis of visual behaviour (pp. 549–586). MIT Press.

- Vallortigara, G. (2021). The efference copy signal as a key mechanism for consciousness. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 15, 765646. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2021.765646

- Wolpert, D. M., & Kawato, M. (1998). Multiple paired forward and inverse models for motor control. Neural Networks, 11(7–8), 1317–1329. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-6080(98)00066-5